Research Interviews: An effective and insightful way of data collection

Research interviews play a pivotal role in collecting data for various academic, scientific, and professional endeavors. They provide researchers with an opportunity to delve deep into the thoughts, experiences, and perspectives of an individual, thus enabling a comprehensive understanding of complex phenomena. It is important for researchers to design an effective and insightful method of data collection on a particular topic. A research interview is typically a two-person meeting conducted to collect information on a certain topic. It is a qualitative data collection method to gain primary information.

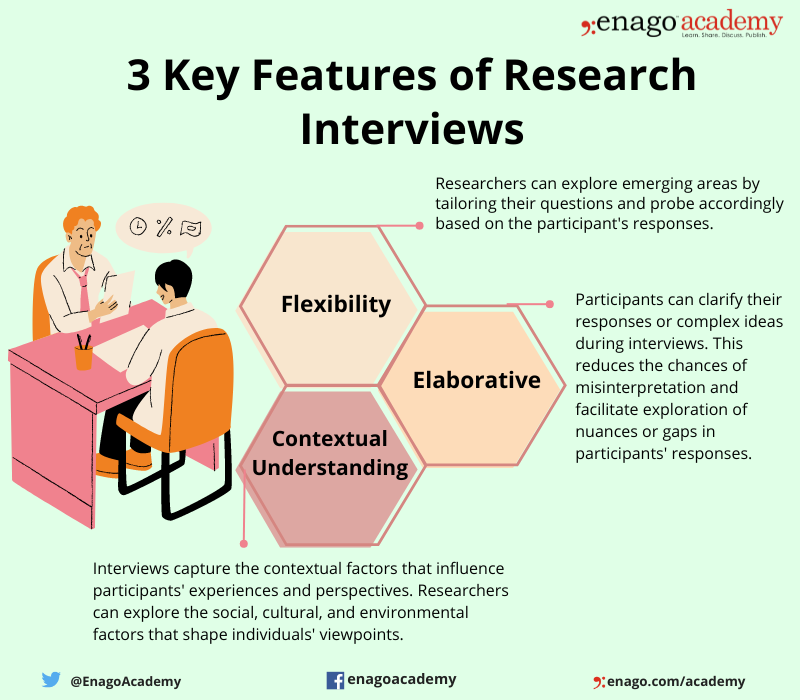

The three key features of a research interview are as follows:

Table of Contents

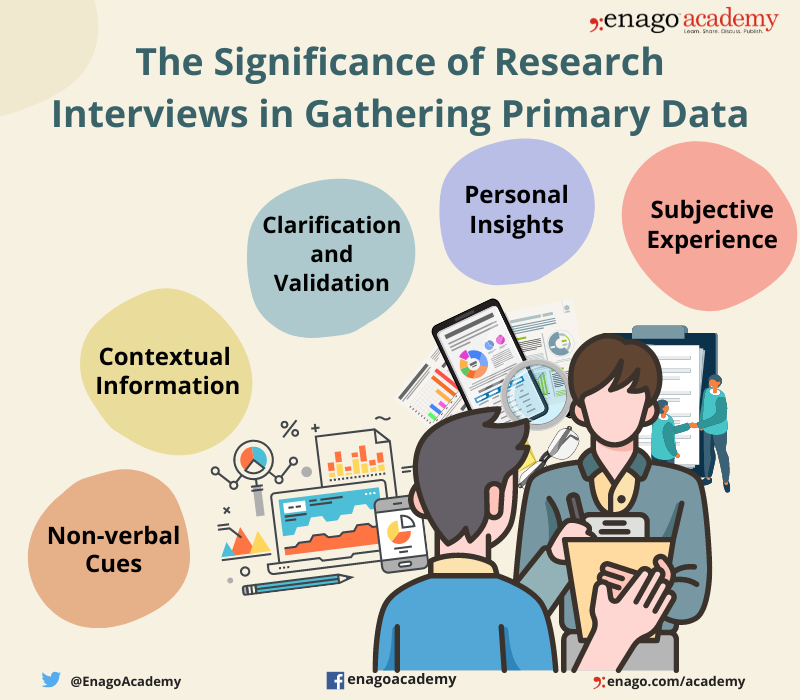

The Significance of Research Interviews in Gathering Primary Data

The role of research interviews in gathering first-hand information is invaluable. Additionally, they allow researchers to interact directly with participants, enabling them to collect unfiltered primary data.

1. Subjective Experience

Research interviews facilitate in-depth exploration of a research topic. Thus, by engaging in one-to-one conversation with participants, researchers can delve into the nuances and complexities of their experiences, perspectives, and opinions. This allows comprehensive understanding of the research subject that may not be possible through other methods. Also, research interviews offer the unique advantage of capturing subjective experiences through personal narratives. Moreover, participants can express their thoughts, feelings, and beliefs, which add depth to the findings.

2. Personal Insights

Research interviews offer an opportunity for participants to share their views and opinions on the objective they are being interviewed for. Furthermore, participants can express their thoughts and experiences, providing rich qualitative data . Consequently, these personal narratives add a human element to the research, thus enhancing the understanding of the topic from the participants’ perspectives. Research interviews offer the opportunity to uncover unanticipated insights or emerging themes. Additionally, open-ended questions and active listening can help the researchers to identify new perspectives, ideas, or patterns that may not have been initially considered. As a result, these factors can lead to new avenues for exploration.

3. Clarification and Validation

Researchers can clarify participants’ responses and validate their understanding during an interview. This ensures accurate data collection and interpretation. Additionally, researchers can probe deeper into participants’ statements and seek clarification on any ambiguity in the information.

4. Contextual Information

Research interviews allow researchers to gather contextual information that offers a comprehensive understanding of the research topic. Additionally, participants can provide insights into the social, cultural, or environmental factors that shape their experiences, behaviors, and beliefs. This contextual information helps researchers place the data in a broader context and facilitates a more nuanced analysis.

5. Non-verbal Cues

In addition to verbal responses, research interviews allow researchers to observe non-verbal cues such as body language, facial expressions, and tone of voice. Additionally, non-verbal cues can convey information, such as emotions, attitudes, or levels of comfort. Furthermore, integrating non-verbal cues with verbal responses provides a more holistic understanding of participants’ experiences and enriches the data collection process.

Research interviews offer several advantages, making them a reliable tool for collecting information. However, choosing the right type of research interview is essential for collecting useful data.

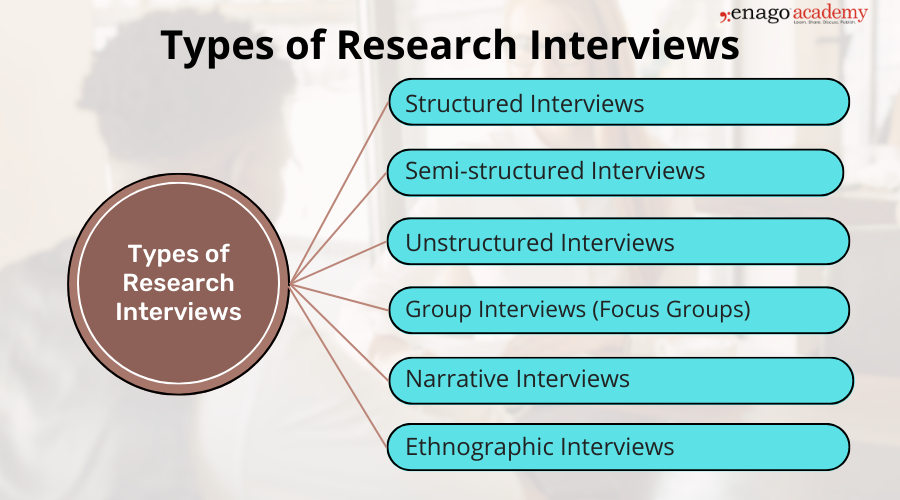

Types of Research Interviews

There are several types of research interviews that researchers can use based on their research goals , the nature of their study, and the data they aim to collect. Here are some common types of research interviews:

1. Structured Interviews

- Structured interviews are standardized and follow a fixed format.

- Therefore, these interviews have a pre-determined set of questions.

- All the participants are asked the same set of questions in the same order.

- Therefore, this type of interview facilitates standardization and allows easy comparison and quantitative analysis of responses.

- As a result, structured interviews are used in surveys or studies which aims for a high level of standardization and comparability.

2. Semi-structured Interviews

- Semi-structured interviews offer a flexible framework by combining pre-determined questions.

- So, this gives an opportunity for follow-up questions and open-ended discussions.

- Researchers have a list of core questions but can adapt the interview depending on the participant’s responses.

- Consequently, this allows for in-depth exploration while maintaining some level of consistency across interviews.

- As a result, semi-structured interviews are widely used in qualitative research, where content-rich data is desired.

3. Unstructured Interviews

- Unstructured interviews provide the greatest flexibility and freedom in the interview process.

- This type do not have a pre-determined set of questions.

- Thus, the conversation flows naturally based on the participant’s responses and the researcher’s interests.

- Moreover, this type of interview allows for open-ended exploration and encourages participants to share their experiences, thoughts, and perspectives freely.

- Unstructured interviews useful to explore new or complex research topics, with limited preconceived questions.

4. Group Interviews (Focus Groups)

- Group interviews involve multiple participants who engage in a facilitated discussion on a specific topic.

- This format allows the interaction and exchange of ideas among participants, generating a group dynamic.

- Therefore, group interviews are beneficial for capturing diverse perspectives, and generating collective insights.

- They are often used in market research, social sciences, or studies demanding shared experiences.

5. Narrative Interviews

- Narrative interviews focus on eliciting participants’ personal stories, views, experiences, and narratives. Researchers aim to look into the individual’s life journey.

- As a result, this type of interview allows participants to construct and share their own narratives, providing rich qualitative data.

- Qualitative research, oral history, or studies focusing on individual experiences and identities uses narrative interviews.

6. Ethnographic Interviews

- Ethnographic interviews are conducted within the context of ethnographic research, where researchers immerse themselves in a specific social or cultural setting.

- These interviews aim to understand participants’ experiences, beliefs, and practices within their cultural context, thereby understanding diversity in different ethnic groups.

- Furthermore, ethnographic interviews involve building rapport, observing the participants’ daily lives, and engaging in conversations that capture the nuances of the culture under study.

It must be noted that these interview types are not mutually exclusive. Therefore, researchers often employ a combination of approaches to gather the most comprehensive data for their research. The choice of interview type depends on the research objectives and the nature of the research topic.

Steps of Conducting a Research Interview

Research interviews offer several benefits, and thus careful planning and execution of the entire process are important to gather in-depth information from the participants. While conducting an interview, it is essential to know the necessary steps to follow for ensuring success. The steps to conduct a research interview are as follows:

- Identify the objectives and understand the goals

- Select an appropriate interview format

- Organize the necessary materials for the interview

- Understand the questions to be addressed

- Analyze the demographics of interviewees

- Select the interviewees

- Design the interview questions to gather sufficient information

- Schedule the interview

- Explain the purpose of the interview

- Analyze the interviewee based on his/her responses

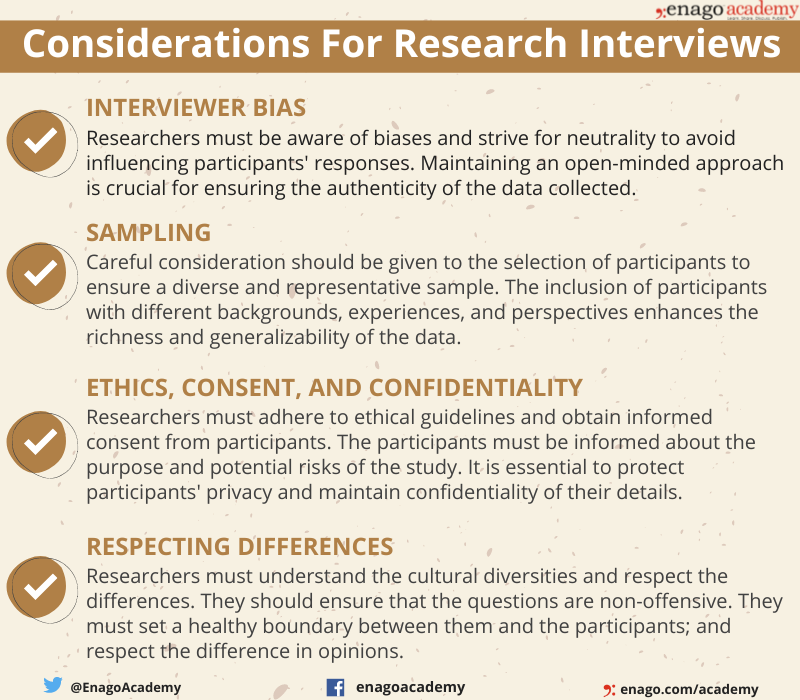

Considerations for Research Interviews

Since the flexible nature of research interviews makes them an invaluable tool for data collection, researchers must consider certain factors to make the process effective. They should avoid bias and preconceived notion against the participants. Furthermore, researchers must comply with ethical considerations and respect the cultural differences between them and the participants. Also, they should ensure careful tailoring of the questions to avoid making them offensive or derogatory. The interviewers must respect the privacy of the participants and ensure the confidentiality of their details.

By ensuring due diligence of these considerations associated with research interviews, researchers can maximize the validity and reliability of the collected data, leading to robust and meaningful research outcomes.

Have you ever conducted a research interview? What was your experience? What factors did you consider when conducting a research interview? Share it with researchers worldwide by submitting your thought piece on Enago Academy’s Open Blogging Platform .

Frequently Asked Questions

• Identify the objectives of the interview • State and explain the purpose of the interview • Select an appropriate interview format • Organize the necessary materials for the Interview • Check the demographics of the participants • Select the Interviewees or the participants • Prepare the list of questions to gather maximum useful data from the participants • Schedule the Interview • Analyze the participant based on his/ her Responses

Interviews are important in research as it helps to gather elaborative first-hand information. It helps to draw conclusions from the non-verbal views and personal experiences. It reduces the ambiguity of data through detailed discussions.

The advantages of research interviews are: • It offers first-hand information • Offers detailed assessment which can result in elaborate conclusions • It is easy to conduct • Provides non-verbal cues The disadvantages of research interviews are: • There is a risk of personal bias • It can be time consuming • The outcomes might be unpredictable

The difference between structured and unstructured interview are: • Structured interviews have well-structured questions in a pre-determined order; while unstructured interviews are flexible and do not have a pre-planned set of questions. • Structured interview is more detailed; while unstructured interviews are exploratory in nature. • Structured interview is easier to replicate as compared to unstructured interview.

Focus groups is a group of multiple participants engaging in a facilitated discussion on a specific topic. This format allows for interaction and exchange of ideas among participants.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Publishing Research

- Reporting Research

How to Optimize Your Research Process: A step-by-step guide

For researchers across disciplines, the path to uncovering novel findings and insights is often filled…

- Industry News

- Trending Now

Breaking Barriers: Sony and Nature unveil “Women in Technology Award”

Sony Group Corporation and the prestigious scientific journal Nature have collaborated to launch the inaugural…

Achieving Research Excellence: Checklist for good research practices

Academia is built on the foundation of trustworthy and high-quality research, supported by the pillars…

- Promoting Research

Plain Language Summary — Communicating your research to bridge the academic-lay gap

Science can be complex, but does that mean it should not be accessible to the…

Science under Surveillance: Journals adopt advanced AI to uncover image manipulation

Journals are increasingly turning to cutting-edge AI tools to uncover deceitful images published in manuscripts.…

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for…

Research Recommendations – Guiding policy-makers for evidence-based decision making

Demystifying the Role of Confounding Variables in Research

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What should universities' stance be on AI tools in research and academic writing?

Chapter 11. Interviewing

Introduction.

Interviewing people is at the heart of qualitative research. It is not merely a way to collect data but an intrinsically rewarding activity—an interaction between two people that holds the potential for greater understanding and interpersonal development. Unlike many of our daily interactions with others that are fairly shallow and mundane, sitting down with a person for an hour or two and really listening to what they have to say is a profound and deep enterprise, one that can provide not only “data” for you, the interviewer, but also self-understanding and a feeling of being heard for the interviewee. I always approach interviewing with a deep appreciation for the opportunity it gives me to understand how other people experience the world. That said, there is not one kind of interview but many, and some of these are shallower than others. This chapter will provide you with an overview of interview techniques but with a special focus on the in-depth semistructured interview guide approach, which is the approach most widely used in social science research.

An interview can be variously defined as “a conversation with a purpose” ( Lune and Berg 2018 ) and an attempt to understand the world from the point of view of the person being interviewed: “to unfold the meaning of peoples’ experiences, to uncover their lived world prior to scientific explanations” ( Kvale 2007 ). It is a form of active listening in which the interviewer steers the conversation to subjects and topics of interest to their research but also manages to leave enough space for those interviewed to say surprising things. Achieving that balance is a tricky thing, which is why most practitioners believe interviewing is both an art and a science. In my experience as a teacher, there are some students who are “natural” interviewers (often they are introverts), but anyone can learn to conduct interviews, and everyone, even those of us who have been doing this for years, can improve their interviewing skills. This might be a good time to highlight the fact that the interview is a product between interviewer and interviewee and that this product is only as good as the rapport established between the two participants. Active listening is the key to establishing this necessary rapport.

Patton ( 2002 ) makes the argument that we use interviews because there are certain things that are not observable. In particular, “we cannot observe feelings, thoughts, and intentions. We cannot observe behaviors that took place at some previous point in time. We cannot observe situations that preclude the presence of an observer. We cannot observe how people have organized the world and the meanings they attach to what goes on in the world. We have to ask people questions about those things” ( 341 ).

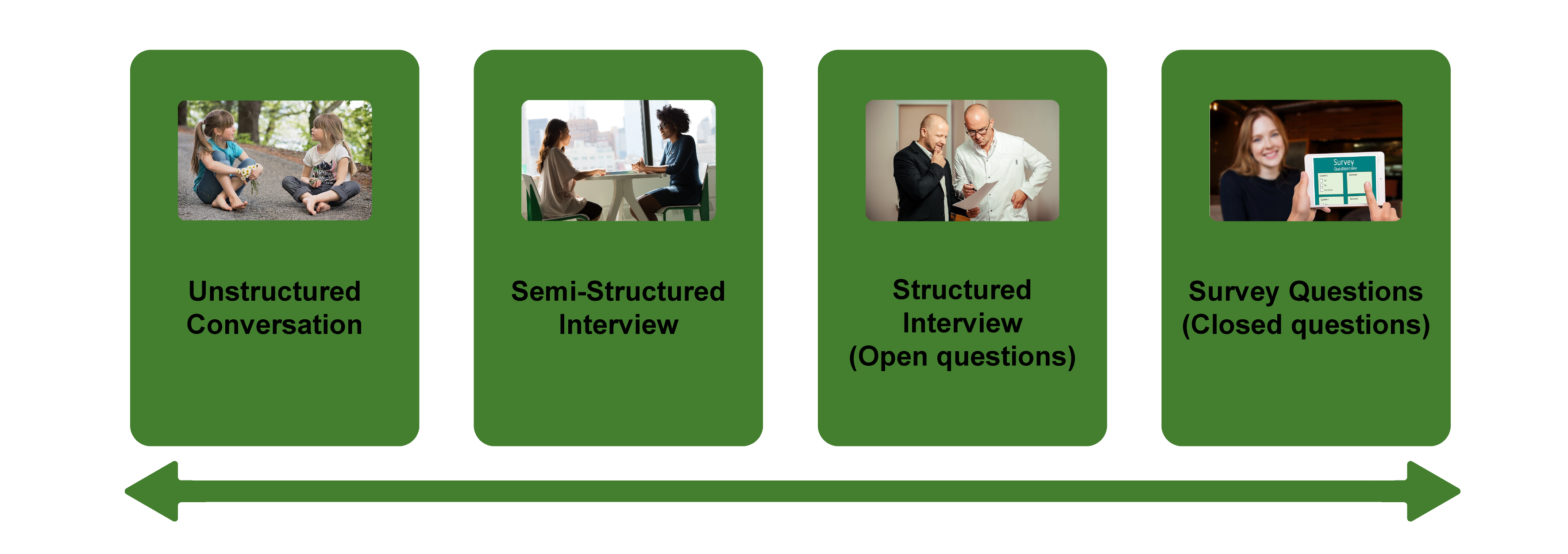

Types of Interviews

There are several distinct types of interviews. Imagine a continuum (figure 11.1). On one side are unstructured conversations—the kind you have with your friends. No one is in control of those conversations, and what you talk about is often random—whatever pops into your head. There is no secret, underlying purpose to your talking—if anything, the purpose is to talk to and engage with each other, and the words you use and the things you talk about are a little beside the point. An unstructured interview is a little like this informal conversation, except that one of the parties to the conversation (you, the researcher) does have an underlying purpose, and that is to understand the other person. You are not friends speaking for no purpose, but it might feel just as unstructured to the “interviewee” in this scenario. That is one side of the continuum. On the other side are fully structured and standardized survey-type questions asked face-to-face. Here it is very clear who is asking the questions and who is answering them. This doesn’t feel like a conversation at all! A lot of people new to interviewing have this ( erroneously !) in mind when they think about interviews as data collection. Somewhere in the middle of these two extreme cases is the “ semistructured” interview , in which the researcher uses an “interview guide” to gently move the conversation to certain topics and issues. This is the primary form of interviewing for qualitative social scientists and will be what I refer to as interviewing for the rest of this chapter, unless otherwise specified.

Informal (unstructured conversations). This is the most “open-ended” approach to interviewing. It is particularly useful in conjunction with observational methods (see chapters 13 and 14). There are no predetermined questions. Each interview will be different. Imagine you are researching the Oregon Country Fair, an annual event in Veneta, Oregon, that includes live music, artisan craft booths, face painting, and a lot of people walking through forest paths. It’s unlikely that you will be able to get a person to sit down with you and talk intensely about a set of questions for an hour and a half. But you might be able to sidle up to several people and engage with them about their experiences at the fair. You might have a general interest in what attracts people to these events, so you could start a conversation by asking strangers why they are here or why they come back every year. That’s it. Then you have a conversation that may lead you anywhere. Maybe one person tells a long story about how their parents brought them here when they were a kid. A second person talks about how this is better than Burning Man. A third person shares their favorite traveling band. And yet another enthuses about the public library in the woods. During your conversations, you also talk about a lot of other things—the weather, the utilikilts for sale, the fact that a favorite food booth has disappeared. It’s all good. You may not be able to record these conversations. Instead, you might jot down notes on the spot and then, when you have the time, write down as much as you can remember about the conversations in long fieldnotes. Later, you will have to sit down with these fieldnotes and try to make sense of all the information (see chapters 18 and 19).

Interview guide ( semistructured interview ). This is the primary type employed by social science qualitative researchers. The researcher creates an “interview guide” in advance, which she uses in every interview. In theory, every person interviewed is asked the same questions. In practice, every person interviewed is asked mostly the same topics but not always the same questions, as the whole point of a “guide” is that it guides the direction of the conversation but does not command it. The guide is typically between five and ten questions or question areas, sometimes with suggested follow-ups or prompts . For example, one question might be “What was it like growing up in Eastern Oregon?” with prompts such as “Did you live in a rural area? What kind of high school did you attend?” to help the conversation develop. These interviews generally take place in a quiet place (not a busy walkway during a festival) and are recorded. The recordings are transcribed, and those transcriptions then become the “data” that is analyzed (see chapters 18 and 19). The conventional length of one of these types of interviews is between one hour and two hours, optimally ninety minutes. Less than one hour doesn’t allow for much development of questions and thoughts, and two hours (or more) is a lot of time to ask someone to sit still and answer questions. If you have a lot of ground to cover, and the person is willing, I highly recommend two separate interview sessions, with the second session being slightly shorter than the first (e.g., ninety minutes the first day, sixty minutes the second). There are lots of good reasons for this, but the most compelling one is that this allows you to listen to the first day’s recording and catch anything interesting you might have missed in the moment and so develop follow-up questions that can probe further. This also allows the person being interviewed to have some time to think about the issues raised in the interview and go a little deeper with their answers.

Standardized questionnaire with open responses ( structured interview ). This is the type of interview a lot of people have in mind when they hear “interview”: a researcher comes to your door with a clipboard and proceeds to ask you a series of questions. These questions are all the same whoever answers the door; they are “standardized.” Both the wording and the exact order are important, as people’s responses may vary depending on how and when a question is asked. These are qualitative only in that the questions allow for “open-ended responses”: people can say whatever they want rather than select from a predetermined menu of responses. For example, a survey I collaborated on included this open-ended response question: “How does class affect one’s career success in sociology?” Some of the answers were simply one word long (e.g., “debt”), and others were long statements with stories and personal anecdotes. It is possible to be surprised by the responses. Although it’s a stretch to call this kind of questioning a conversation, it does allow the person answering the question some degree of freedom in how they answer.

Survey questionnaire with closed responses (not an interview!). Standardized survey questions with specific answer options (e.g., closed responses) are not really interviews at all, and they do not generate qualitative data. For example, if we included five options for the question “How does class affect one’s career success in sociology?”—(1) debt, (2) social networks, (3) alienation, (4) family doesn’t understand, (5) type of grad program—we leave no room for surprises at all. Instead, we would most likely look at patterns around these responses, thinking quantitatively rather than qualitatively (e.g., using regression analysis techniques, we might find that working-class sociologists were twice as likely to bring up alienation). It can sometimes be confusing for new students because the very same survey can include both closed-ended and open-ended questions. The key is to think about how these will be analyzed and to what level surprises are possible. If your plan is to turn all responses into a number and make predictions about correlations and relationships, you are no longer conducting qualitative research. This is true even if you are conducting this survey face-to-face with a real live human. Closed-response questions are not conversations of any kind, purposeful or not.

In summary, the semistructured interview guide approach is the predominant form of interviewing for social science qualitative researchers because it allows a high degree of freedom of responses from those interviewed (thus allowing for novel discoveries) while still maintaining some connection to a research question area or topic of interest. The rest of the chapter assumes the employment of this form.

Creating an Interview Guide

Your interview guide is the instrument used to bridge your research question(s) and what the people you are interviewing want to tell you. Unlike a standardized questionnaire, the questions actually asked do not need to be exactly what you have written down in your guide. The guide is meant to create space for those you are interviewing to talk about the phenomenon of interest, but sometimes you are not even sure what that phenomenon is until you start asking questions. A priority in creating an interview guide is to ensure it offers space. One of the worst mistakes is to create questions that are so specific that the person answering them will not stray. Relatedly, questions that sound “academic” will shut down a lot of respondents. A good interview guide invites respondents to talk about what is important to them, not feel like they are performing or being evaluated by you.

Good interview questions should not sound like your “research question” at all. For example, let’s say your research question is “How do patriarchal assumptions influence men’s understanding of climate change and responses to climate change?” It would be worse than unhelpful to ask a respondent, “How do your assumptions about the role of men affect your understanding of climate change?” You need to unpack this into manageable nuggets that pull your respondent into the area of interest without leading him anywhere. You could start by asking him what he thinks about climate change in general. Or, even better, whether he has any concerns about heatwaves or increased tornadoes or polar icecaps melting. Once he starts talking about that, you can ask follow-up questions that bring in issues around gendered roles, perhaps asking if he is married (to a woman) and whether his wife shares his thoughts and, if not, how they negotiate that difference. The fact is, you won’t really know the right questions to ask until he starts talking.

There are several distinct types of questions that can be used in your interview guide, either as main questions or as follow-up probes. If you remember that the point is to leave space for the respondent, you will craft a much more effective interview guide! You will also want to think about the place of time in both the questions themselves (past, present, future orientations) and the sequencing of the questions.

Researcher Note

Suggestion : As you read the next three sections (types of questions, temporality, question sequence), have in mind a particular research question, and try to draft questions and sequence them in a way that opens space for a discussion that helps you answer your research question.

Type of Questions

Experience and behavior questions ask about what a respondent does regularly (their behavior) or has done (their experience). These are relatively easy questions for people to answer because they appear more “factual” and less subjective. This makes them good opening questions. For the study on climate change above, you might ask, “Have you ever experienced an unusual weather event? What happened?” Or “You said you work outside? What is a typical summer workday like for you? How do you protect yourself from the heat?”

Opinion and values questions , in contrast, ask questions that get inside the minds of those you are interviewing. “Do you think climate change is real? Who or what is responsible for it?” are two such questions. Note that you don’t have to literally ask, “What is your opinion of X?” but you can find a way to ask the specific question relevant to the conversation you are having. These questions are a bit trickier to ask because the answers you get may depend in part on how your respondent perceives you and whether they want to please you or not. We’ve talked a fair amount about being reflective. Here is another place where this comes into play. You need to be aware of the effect your presence might have on the answers you are receiving and adjust accordingly. If you are a woman who is perceived as liberal asking a man who identifies as conservative about climate change, there is a lot of subtext that can be going on in the interview. There is no one right way to resolve this, but you must at least be aware of it.

Feeling questions are questions that ask respondents to draw on their emotional responses. It’s pretty common for academic researchers to forget that we have bodies and emotions, but people’s understandings of the world often operate at this affective level, sometimes unconsciously or barely consciously. It is a good idea to include questions that leave space for respondents to remember, imagine, or relive emotional responses to particular phenomena. “What was it like when you heard your cousin’s house burned down in that wildfire?” doesn’t explicitly use any emotion words, but it allows your respondent to remember what was probably a pretty emotional day. And if they respond emotionally neutral, that is pretty interesting data too. Note that asking someone “How do you feel about X” is not always going to evoke an emotional response, as they might simply turn around and respond with “I think that…” It is better to craft a question that actually pushes the respondent into the affective category. This might be a specific follow-up to an experience and behavior question —for example, “You just told me about your daily routine during the summer heat. Do you worry it is going to get worse?” or “Have you ever been afraid it will be too hot to get your work accomplished?”

Knowledge questions ask respondents what they actually know about something factual. We have to be careful when we ask these types of questions so that respondents do not feel like we are evaluating them (which would shut them down), but, for example, it is helpful to know when you are having a conversation about climate change that your respondent does in fact know that unusual weather events have increased and that these have been attributed to climate change! Asking these questions can set the stage for deeper questions and can ensure that the conversation makes the same kind of sense to both participants. For example, a conversation about political polarization can be put back on track once you realize that the respondent doesn’t really have a clear understanding that there are two parties in the US. Instead of asking a series of questions about Republicans and Democrats, you might shift your questions to talk more generally about political disagreements (e.g., “people against abortion”). And sometimes what you do want to know is the level of knowledge about a particular program or event (e.g., “Are you aware you can discharge your student loans through the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program?”).

Sensory questions call on all senses of the respondent to capture deeper responses. These are particularly helpful in sparking memory. “Think back to your childhood in Eastern Oregon. Describe the smells, the sounds…” Or you could use these questions to help a person access the full experience of a setting they customarily inhabit: “When you walk through the doors to your office building, what do you see? Hear? Smell?” As with feeling questions , these questions often supplement experience and behavior questions . They are another way of allowing your respondent to report fully and deeply rather than remain on the surface.

Creative questions employ illustrative examples, suggested scenarios, or simulations to get respondents to think more deeply about an issue, topic, or experience. There are many options here. In The Trouble with Passion , Erin Cech ( 2021 ) provides a scenario in which “Joe” is trying to decide whether to stay at his decent but boring computer job or follow his passion by opening a restaurant. She asks respondents, “What should Joe do?” Their answers illuminate the attraction of “passion” in job selection. In my own work, I have used a news story about an upwardly mobile young man who no longer has time to see his mother and sisters to probe respondents’ feelings about the costs of social mobility. Jessi Streib and Betsy Leondar-Wright have used single-page cartoon “scenes” to elicit evaluations of potential racial discrimination, sexual harassment, and classism. Barbara Sutton ( 2010 ) has employed lists of words (“strong,” “mother,” “victim”) on notecards she fans out and asks her female respondents to select and discuss.

Background/Demographic Questions

You most definitely will want to know more about the person you are interviewing in terms of conventional demographic information, such as age, race, gender identity, occupation, and educational attainment. These are not questions that normally open up inquiry. [1] For this reason, my practice has been to include a separate “demographic questionnaire” sheet that I ask each respondent to fill out at the conclusion of the interview. Only include those aspects that are relevant to your study. For example, if you are not exploring religion or religious affiliation, do not include questions about a person’s religion on the demographic sheet. See the example provided at the end of this chapter.

Temporality

Any type of question can have a past, present, or future orientation. For example, if you are asking a behavior question about workplace routine, you might ask the respondent to talk about past work, present work, and ideal (future) work. Similarly, if you want to understand how people cope with natural disasters, you might ask your respondent how they felt then during the wildfire and now in retrospect and whether and to what extent they have concerns for future wildfire disasters. It’s a relatively simple suggestion—don’t forget to ask about past, present, and future—but it can have a big impact on the quality of the responses you receive.

Question Sequence

Having a list of good questions or good question areas is not enough to make a good interview guide. You will want to pay attention to the order in which you ask your questions. Even though any one respondent can derail this order (perhaps by jumping to answer a question you haven’t yet asked), a good advance plan is always helpful. When thinking about sequence, remember that your goal is to get your respondent to open up to you and to say things that might surprise you. To establish rapport, it is best to start with nonthreatening questions. Asking about the present is often the safest place to begin, followed by the past (they have to know you a little bit to get there), and lastly, the future (talking about hopes and fears requires the most rapport). To allow for surprises, it is best to move from very general questions to more particular questions only later in the interview. This ensures that respondents have the freedom to bring up the topics that are relevant to them rather than feel like they are constrained to answer you narrowly. For example, refrain from asking about particular emotions until these have come up previously—don’t lead with them. Often, your more particular questions will emerge only during the course of the interview, tailored to what is emerging in conversation.

Once you have a set of questions, read through them aloud and imagine you are being asked the same questions. Does the set of questions have a natural flow? Would you be willing to answer the very first question to a total stranger? Does your sequence establish facts and experiences before moving on to opinions and values? Did you include prefatory statements, where necessary; transitions; and other announcements? These can be as simple as “Hey, we talked a lot about your experiences as a barista while in college.… Now I am turning to something completely different: how you managed friendships in college.” That is an abrupt transition, but it has been softened by your acknowledgment of that.

Probes and Flexibility

Once you have the interview guide, you will also want to leave room for probes and follow-up questions. As in the sample probe included here, you can write out the obvious probes and follow-up questions in advance. You might not need them, as your respondent might anticipate them and include full responses to the original question. Or you might need to tailor them to how your respondent answered the question. Some common probes and follow-up questions include asking for more details (When did that happen? Who else was there?), asking for elaboration (Could you say more about that?), asking for clarification (Does that mean what I think it means or something else? I understand what you mean, but someone else reading the transcript might not), and asking for contrast or comparison (How did this experience compare with last year’s event?). “Probing is a skill that comes from knowing what to look for in the interview, listening carefully to what is being said and what is not said, and being sensitive to the feedback needs of the person being interviewed” ( Patton 2002:374 ). It takes work! And energy. I and many other interviewers I know report feeling emotionally and even physically drained after conducting an interview. You are tasked with active listening and rearranging your interview guide as needed on the fly. If you only ask the questions written down in your interview guide with no deviations, you are doing it wrong. [2]

The Final Question

Every interview guide should include a very open-ended final question that allows for the respondent to say whatever it is they have been dying to tell you but you’ve forgotten to ask. About half the time they are tired too and will tell you they have nothing else to say. But incredibly, some of the most honest and complete responses take place here, at the end of a long interview. You have to realize that the person being interviewed is often discovering things about themselves as they talk to you and that this process of discovery can lead to new insights for them. Making space at the end is therefore crucial. Be sure you convey that you actually do want them to tell you more, that the offer of “anything else?” is not read as an empty convention where the polite response is no. Here is where you can pull from that active listening and tailor the final question to the particular person. For example, “I’ve asked you a lot of questions about what it was like to live through that wildfire. I’m wondering if there is anything I’ve forgotten to ask, especially because I haven’t had that experience myself” is a much more inviting final question than “Great. Anything you want to add?” It’s also helpful to convey to the person that you have the time to listen to their full answer, even if the allotted time is at the end. After all, there are no more questions to ask, so the respondent knows exactly how much time is left. Do them the courtesy of listening to them!

Conducting the Interview

Once you have your interview guide, you are on your way to conducting your first interview. I always practice my interview guide with a friend or family member. I do this even when the questions don’t make perfect sense for them, as it still helps me realize which questions make no sense, are poorly worded (too academic), or don’t follow sequentially. I also practice the routine I will use for interviewing, which goes something like this:

- Introduce myself and reintroduce the study

- Provide consent form and ask them to sign and retain/return copy

- Ask if they have any questions about the study before we begin

- Ask if I can begin recording

- Ask questions (from interview guide)

- Turn off the recording device

- Ask if they are willing to fill out my demographic questionnaire

- Collect questionnaire and, without looking at the answers, place in same folder as signed consent form

- Thank them and depart

A note on remote interviewing: Interviews have traditionally been conducted face-to-face in a private or quiet public setting. You don’t want a lot of background noise, as this will make transcriptions difficult. During the recent global pandemic, many interviewers, myself included, learned the benefits of interviewing remotely. Although face-to-face is still preferable for many reasons, Zoom interviewing is not a bad alternative, and it does allow more interviews across great distances. Zoom also includes automatic transcription, which significantly cuts down on the time it normally takes to convert our conversations into “data” to be analyzed. These automatic transcriptions are not perfect, however, and you will still need to listen to the recording and clarify and clean up the transcription. Nor do automatic transcriptions include notations of body language or change of tone, which you may want to include. When interviewing remotely, you will want to collect the consent form before you meet: ask them to read, sign, and return it as an email attachment. I think it is better to ask for the demographic questionnaire after the interview, but because some respondents may never return it then, it is probably best to ask for this at the same time as the consent form, in advance of the interview.

What should you bring to the interview? I would recommend bringing two copies of the consent form (one for you and one for the respondent), a demographic questionnaire, a manila folder in which to place the signed consent form and filled-out demographic questionnaire, a printed copy of your interview guide (I print with three-inch right margins so I can jot down notes on the page next to relevant questions), a pen, a recording device, and water.

After the interview, you will want to secure the signed consent form in a locked filing cabinet (if in print) or a password-protected folder on your computer. Using Excel or a similar program that allows tables/spreadsheets, create an identifying number for your interview that links to the consent form without using the name of your respondent. For example, let’s say that I conduct interviews with US politicians, and the first person I meet with is George W. Bush. I will assign the transcription the number “INT#001” and add it to the signed consent form. [3] The signed consent form goes into a locked filing cabinet, and I never use the name “George W. Bush” again. I take the information from the demographic sheet, open my Excel spreadsheet, and add the relevant information in separate columns for the row INT#001: White, male, Republican. When I interview Bill Clinton as my second interview, I include a second row: INT#002: White, male, Democrat. And so on. The only link to the actual name of the respondent and this information is the fact that the consent form (unavailable to anyone but me) has stamped on it the interview number.

Many students get very nervous before their first interview. Actually, many of us are always nervous before the interview! But do not worry—this is normal, and it does pass. Chances are, you will be pleasantly surprised at how comfortable it begins to feel. These “purposeful conversations” are often a delight for both participants. This is not to say that sometimes things go wrong. I often have my students practice several “bad scenarios” (e.g., a respondent that you cannot get to open up; a respondent who is too talkative and dominates the conversation, steering it away from the topics you are interested in; emotions that completely take over; or shocking disclosures you are ill-prepared to handle), but most of the time, things go quite well. Be prepared for the unexpected, but know that the reason interviews are so popular as a technique of data collection is that they are usually richly rewarding for both participants.

One thing that I stress to my methods students and remind myself about is that interviews are still conversations between people. If there’s something you might feel uncomfortable asking someone about in a “normal” conversation, you will likely also feel a bit of discomfort asking it in an interview. Maybe more importantly, your respondent may feel uncomfortable. Social research—especially about inequality—can be uncomfortable. And it’s easy to slip into an abstract, intellectualized, or removed perspective as an interviewer. This is one reason trying out interview questions is important. Another is that sometimes the question sounds good in your head but doesn’t work as well out loud in practice. I learned this the hard way when a respondent asked me how I would answer the question I had just posed, and I realized that not only did I not really know how I would answer it, but I also wasn’t quite as sure I knew what I was asking as I had thought.

—Elizabeth M. Lee, Associate Professor of Sociology at Saint Joseph’s University, author of Class and Campus Life , and co-author of Geographies of Campus Inequality

How Many Interviews?

Your research design has included a targeted number of interviews and a recruitment plan (see chapter 5). Follow your plan, but remember that “ saturation ” is your goal. You interview as many people as you can until you reach a point at which you are no longer surprised by what they tell you. This means not that no one after your first twenty interviews will have surprising, interesting stories to tell you but rather that the picture you are forming about the phenomenon of interest to you from a research perspective has come into focus, and none of the interviews are substantially refocusing that picture. That is when you should stop collecting interviews. Note that to know when you have reached this, you will need to read your transcripts as you go. More about this in chapters 18 and 19.

Your Final Product: The Ideal Interview Transcript

A good interview transcript will demonstrate a subtly controlled conversation by the skillful interviewer. In general, you want to see replies that are about one paragraph long, not short sentences and not running on for several pages. Although it is sometimes necessary to follow respondents down tangents, it is also often necessary to pull them back to the questions that form the basis of your research study. This is not really a free conversation, although it may feel like that to the person you are interviewing.

Final Tips from an Interview Master

Annette Lareau is arguably one of the masters of the trade. In Listening to People , she provides several guidelines for good interviews and then offers a detailed example of an interview gone wrong and how it could be addressed (please see the “Further Readings” at the end of this chapter). Here is an abbreviated version of her set of guidelines: (1) interview respondents who are experts on the subjects of most interest to you (as a corollary, don’t ask people about things they don’t know); (2) listen carefully and talk as little as possible; (3) keep in mind what you want to know and why you want to know it; (4) be a proactive interviewer (subtly guide the conversation); (5) assure respondents that there aren’t any right or wrong answers; (6) use the respondent’s own words to probe further (this both allows you to accurately identify what you heard and pushes the respondent to explain further); (7) reuse effective probes (don’t reinvent the wheel as you go—if repeating the words back works, do it again and again); (8) focus on learning the subjective meanings that events or experiences have for a respondent; (9) don’t be afraid to ask a question that draws on your own knowledge (unlike trial lawyers who are trained never to ask a question for which they don’t already know the answer, sometimes it’s worth it to ask risky questions based on your hypotheses or just plain hunches); (10) keep thinking while you are listening (so difficult…and important); (11) return to a theme raised by a respondent if you want further information; (12) be mindful of power inequalities (and never ever coerce a respondent to continue the interview if they want out); (13) take control with overly talkative respondents; (14) expect overly succinct responses, and develop strategies for probing further; (15) balance digging deep and moving on; (16) develop a plan to deflect questions (e.g., let them know you are happy to answer any questions at the end of the interview, but you don’t want to take time away from them now); and at the end, (17) check to see whether you have asked all your questions. You don’t always have to ask everyone the same set of questions, but if there is a big area you have forgotten to cover, now is the time to recover ( Lareau 2021:93–103 ).

Sample: Demographic Questionnaire

ASA Taskforce on First-Generation and Working-Class Persons in Sociology – Class Effects on Career Success

Supplementary Demographic Questionnaire

Thank you for your participation in this interview project. We would like to collect a few pieces of key demographic information from you to supplement our analyses. Your answers to these questions will be kept confidential and stored by ID number. All of your responses here are entirely voluntary!

What best captures your race/ethnicity? (please check any/all that apply)

- White (Non Hispanic/Latina/o/x)

- Black or African American

- Hispanic, Latino/a/x of Spanish

- Asian or Asian American

- American Indian or Alaska Native

- Middle Eastern or North African

- Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

- Other : (Please write in: ________________)

What is your current position?

- Grad Student

- Full Professor

Please check any and all of the following that apply to you:

- I identify as a working-class academic

- I was the first in my family to graduate from college

- I grew up poor

What best reflects your gender?

- Transgender female/Transgender woman

- Transgender male/Transgender man

- Gender queer/ Gender nonconforming

Anything else you would like us to know about you?

Example: Interview Guide

In this example, follow-up prompts are italicized. Note the sequence of questions. That second question often elicits an entire life history , answering several later questions in advance.

Introduction Script/Question

Thank you for participating in our survey of ASA members who identify as first-generation or working-class. As you may have heard, ASA has sponsored a taskforce on first-generation and working-class persons in sociology and we are interested in hearing from those who so identify. Your participation in this interview will help advance our knowledge in this area.

- The first thing we would like to as you is why you have volunteered to be part of this study? What does it mean to you be first-gen or working class? Why were you willing to be interviewed?

- How did you decide to become a sociologist?

- Can you tell me a little bit about where you grew up? ( prompts: what did your parent(s) do for a living? What kind of high school did you attend?)

- Has this identity been salient to your experience? (how? How much?)

- How welcoming was your grad program? Your first academic employer?

- Why did you decide to pursue sociology at the graduate level?

- Did you experience culture shock in college? In graduate school?

- Has your FGWC status shaped how you’ve thought about where you went to school? debt? etc?

- Were you mentored? How did this work (not work)? How might it?

- What did you consider when deciding where to go to grad school? Where to apply for your first position?

- What, to you, is a mark of career success? Have you achieved that success? What has helped or hindered your pursuit of success?

- Do you think sociology, as a field, cares about prestige?

- Let’s talk a little bit about intersectionality. How does being first-gen/working class work alongside other identities that are important to you?

- What do your friends and family think about your career? Have you had any difficulty relating to family members or past friends since becoming highly educated?

- Do you have any debt from college/grad school? Are you concerned about this? Could you explain more about how you paid for college/grad school? (here, include assistance from family, fellowships, scholarships, etc.)

- (You’ve mentioned issues or obstacles you had because of your background.) What could have helped? Or, who or what did? Can you think of fortuitous moments in your career?

- Do you have any regrets about the path you took?

- Is there anything else you would like to add? Anything that the Taskforce should take note of, that we did not ask you about here?

Further Readings

Britten, Nicky. 1995. “Qualitative Interviews in Medical Research.” BMJ: British Medical Journal 31(6999):251–253. A good basic overview of interviewing particularly useful for students of public health and medical research generally.

Corbin, Juliet, and Janice M. Morse. 2003. “The Unstructured Interactive Interview: Issues of Reciprocity and Risks When Dealing with Sensitive Topics.” Qualitative Inquiry 9(3):335–354. Weighs the potential benefits and harms of conducting interviews on topics that may cause emotional distress. Argues that the researcher’s skills and code of ethics should ensure that the interviewing process provides more of a benefit to both participant and researcher than a harm to the former.

Gerson, Kathleen, and Sarah Damaske. 2020. The Science and Art of Interviewing . New York: Oxford University Press. A useful guidebook/textbook for both undergraduates and graduate students, written by sociologists.

Kvale, Steiner. 2007. Doing Interviews . London: SAGE. An easy-to-follow guide to conducting and analyzing interviews by psychologists.

Lamont, Michèle, and Ann Swidler. 2014. “Methodological Pluralism and the Possibilities and Limits of Interviewing.” Qualitative Sociology 37(2):153–171. Written as a response to various debates surrounding the relative value of interview-based studies and ethnographic studies defending the particular strengths of interviewing. This is a must-read article for anyone seriously engaging in qualitative research!

Pugh, Allison J. 2013. “What Good Are Interviews for Thinking about Culture? Demystifying Interpretive Analysis.” American Journal of Cultural Sociology 1(1):42–68. Another defense of interviewing written against those who champion ethnographic methods as superior, particularly in the area of studying culture. A classic.

Rapley, Timothy John. 2001. “The ‘Artfulness’ of Open-Ended Interviewing: Some considerations in analyzing interviews.” Qualitative Research 1(3):303–323. Argues for the importance of “local context” of data production (the relationship built between interviewer and interviewee, for example) in properly analyzing interview data.

Weiss, Robert S. 1995. Learning from Strangers: The Art and Method of Qualitative Interview Studies . New York: Simon and Schuster. A classic and well-regarded textbook on interviewing. Because Weiss has extensive experience conducting surveys, he contrasts the qualitative interview with the survey questionnaire well; particularly useful for those trained in the latter.

- I say “normally” because how people understand their various identities can itself be an expansive topic of inquiry. Here, I am merely talking about collecting otherwise unexamined demographic data, similar to how we ask people to check boxes on surveys. ↵

- Again, this applies to “semistructured in-depth interviewing.” When conducting standardized questionnaires, you will want to ask each question exactly as written, without deviations! ↵

- I always include “INT” in the number because I sometimes have other kinds of data with their own numbering: FG#001 would mean the first focus group, for example. I also always include three-digit spaces, as this allows for up to 999 interviews (or, more realistically, allows for me to interview up to one hundred persons without having to reset my numbering system). ↵

A method of data collection in which the researcher asks the participant questions; the answers to these questions are often recorded and transcribed verbatim. There are many different kinds of interviews - see also semistructured interview , structured interview , and unstructured interview .

A document listing key questions and question areas for use during an interview. It is used most often for semi-structured interviews. A good interview guide may have no more than ten primary questions for two hours of interviewing, but these ten questions will be supplemented by probes and relevant follow-ups throughout the interview. Most IRBs require the inclusion of the interview guide in applications for review. See also interview and semi-structured interview .

A data-collection method that relies on casual, conversational, and informal interviewing. Despite its apparent conversational nature, the researcher usually has a set of particular questions or question areas in mind but allows the interview to unfold spontaneously. This is a common data-collection technique among ethnographers. Compare to the semi-structured or in-depth interview .

A form of interview that follows a standard guide of questions asked, although the order of the questions may change to match the particular needs of each individual interview subject, and probing “follow-up” questions are often added during the course of the interview. The semi-structured interview is the primary form of interviewing used by qualitative researchers in the social sciences. It is sometimes referred to as an “in-depth” interview. See also interview and interview guide .

The cluster of data-collection tools and techniques that involve observing interactions between people, the behaviors, and practices of individuals (sometimes in contrast to what they say about how they act and behave), and cultures in context. Observational methods are the key tools employed by ethnographers and Grounded Theory .

Follow-up questions used in a semi-structured interview to elicit further elaboration. Suggested prompts can be included in the interview guide to be used/deployed depending on how the initial question was answered or if the topic of the prompt does not emerge spontaneously.

A form of interview that follows a strict set of questions, asked in a particular order, for all interview subjects. The questions are also the kind that elicits short answers, and the data is more “informative” than probing. This is often used in mixed-methods studies, accompanying a survey instrument. Because there is no room for nuance or the exploration of meaning in structured interviews, qualitative researchers tend to employ semi-structured interviews instead. See also interview.

The point at which you can conclude data collection because every person you are interviewing, the interaction you are observing, or content you are analyzing merely confirms what you have already noted. Achieving saturation is often used as the justification for the final sample size.

An interview variant in which a person’s life story is elicited in a narrative form. Turning points and key themes are established by the researcher and used as data points for further analysis.

Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods Copyright © 2023 by Allison Hurst is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

20 Most Common Research Scientist Interview Questions and Answers

Common Research Scientist interview questions, how to answer them, and sample answers from a certified career coach.

You’re ready to take the next step in your career and apply for a research scientist position. But first, you have to make it through the interview process.

Knowing what questions to expect ahead of time can help ease some of the anxiety that comes with interviewing. To get you started, here are some common research scientist interview questions—and tips on how to answer them.

- What experience do you have in designing and conducting experiments?

- Describe a research project that you are particularly proud of and explain why.

- How do you ensure the accuracy and reliability of your data?

- Explain how you use statistical analysis to interpret results from experiments.

- Are you familiar with any software programs used for data analysis?

- What strategies do you use to stay up-to-date on new developments in your field?

- How do you handle conflicting opinions or interpretations of data within a team?

- Describe a time when you had to troubleshoot an experiment that wasn’t producing expected results.

- What is your experience with writing scientific papers and presenting findings at conferences?

- How do you approach developing hypotheses and testing them through experimentation?

- What techniques do you use to identify potential sources of bias in experimental design?

- Do you have any experience working with interdisciplinary teams?

- How do you manage competing deadlines and prioritize tasks?

- What methods do you use to communicate complex scientific concepts to non-experts?

- How do you evaluate the ethical implications of your research?

- What strategies do you use to develop innovative solutions to challenging problems?

- Have you ever encountered unexpected results during an experiment? How did you respond?

- Describe a time when you had to collaborate with other researchers to achieve a common goal.

- What would you do if you encountered a problem that was outside of your area of expertise?

- How do you keep track of all the different elements involved in a research project?

1. What experience do you have in designing and conducting experiments?

Research scientists are the people who design and conduct experiments, analyze data, and draw conclusions from the results. It’s important to have experience in this area to make sure that the research is conducted properly and that the results are accurate. This question is also a way for the interviewer to assess your knowledge of the scientific method and how it’s used in research.

How to Answer:

In your answer, you should discuss any experience that you have in designing and conducting experiments. You can talk about the types of experiments you’ve conducted, such as laboratory experiments, field experiments, or surveys. Be sure to mention how you used the scientific method in each experiment, from developing a hypothesis to analyzing data. If you don’t have much direct experience, you can still talk about what you’ve learned about designing and conducting experiments through coursework or research projects.

Example: “I have experience in designing and conducting experiments from my work as a research assistant at XYZ University. I’ve conducted laboratory experiments, field experiments, and surveys to test hypotheses about different topics. In each experiment, I followed the scientific method by formulating a hypothesis, developing an experimental design, collecting data, analyzing it, and drawing conclusions. Additionally, I’ve studied the principles of experimental design in courses such as statistics and psychology. This has given me a strong foundation for understanding how to properly design and conduct experiments.”

2. Describe a research project that you are particularly proud of and explain why.

Research scientists need to be able to think critically and creatively when it comes to problem solving. This question gives the interviewer an opportunity to get a sense of your problem-solving skills and how you approach research. It also gives them insight into the results of your work and the value you can bring to the position.

To answer this question, you should discuss your experience with designing and conducting experiments. Explain the types of experiments you have conducted in the past and how you went about creating a hypothesis and testing it. Talk about the tools and methods you used to analyze data and draw conclusions. Be sure to mention any successes or challenges you faced during the process and how you overcame them. Finally, explain what you learned from these experiences and how they will help you succeed in the role you are applying for.

Example: “I’m particularly proud of a research project I completed last year on the effects of climate change on coral reefs. To conduct this research, I designed experiments to measure the changes in temperature and pH levels in different reef environments. I used sophisticated data analysis tools to analyze the results and draw conclusions about how these changes were impacting the health of the coral. Through this project, I learned a lot about the importance of collecting accurate data and using it to make informed decisions. This experience has helped me develop my problem-solving skills and will be invaluable as I continue to pursue research projects in the future.”

3. How do you ensure the accuracy and reliability of your data?

Research scientists must be able to trust the data they’re working with. Your interviewer will be looking for an understanding of the various methods and processes used to verify the accuracy and reliability of your data, and how you go about ensuring that you’re working with the best possible data to create meaningful results.

You should be prepared to discuss the methods you use to verify data accuracy and reliability. This could include double-checking your sources, running experiments multiple times to ensure consistent results, or using statistical tests to measure the validity of your findings. You should also emphasize any processes you have in place to monitor the quality of the data over time, such as regular reviews or audits. Finally, show that you understand the importance of data integrity by mentioning the potential consequences of inaccurate data.

Example: “I take data accuracy and reliability very seriously. I always double-check my sources to make sure they’re reputable and up-to-date, and I use statistical tests to measure the validity of my findings. I also have a process in place for regular audits and reviews of the data to make sure it remains accurate over time. Most importantly, I understand that inaccurate data can lead to faulty conclusions, which could negatively affect both our research results and reputation. That’s why I’m committed to ensuring that all data is as reliable and accurate as possible.”

4. Explain how you use statistical analysis to interpret results from experiments.

Research scientists are expected to be able to draw meaningful conclusions from the data they collect. This question is designed to determine if you know how to use statistical analysis to make sense of the results you collect. The interviewer wants to know that you can interpret the data and use it to make decisions and draw conclusions.

To answer this question, you should explain how you use statistical analysis to interpret the results from experiments. Talk about what type of statistical tests you use and when you use them. Also discuss any special techniques or software that you use for data analysis. Finally, talk about how you use the results of your analysis to make decisions and draw meaningful conclusions.

Example: “I use a variety of statistical tests and software to interpret the results from experiments. My most commonly used test is ANOVA, which I use to compare differences between two or more groups of data. I also use regression analysis to identify relationships between variables, as well as chi-square tests to determine if there are any significant associations between different factors. In addition, I am proficient in using SPSS for both descriptive and inferential statistics. With all this data, I’m able to draw meaningful conclusions about my findings and make informed decisions based on the results.”

5. Are you familiar with any software programs used for data analysis?

Research scientists rely heavily on data analysis to inform their research and draw conclusions. This means they must be familiar with a variety of software programs that can help them analyze the data they’ve collected. If the position requires a specific software program, the interviewer may ask this question to ensure that you’re familiar with it and can use it effectively.

Before the interview, research which software programs are commonly used for data analysis in your field. Make sure you’re familiar with these programs and can explain how to use them. During the interview, provide specific examples of when you have used a particular program or software suite. If possible, mention any experience you have using the specific software that the company uses. Finally, be sure to emphasize your ability to quickly learn new software if necessary.

Example: “I’m very familiar with software programs used for data analysis. I have extensive experience using SPSS and SAS, which are both common statistical software packages. In my current role as a research scientist at XYZ Research Institute, I often use R to analyze large datasets. I also have some experience with MATLAB, and am confident that I could quickly learn any new software programs necessary for the position.”

6. What strategies do you use to stay up-to-date on new developments in your field?

Research scientists need to stay on top of the latest developments in their field. You need to demonstrate that you can use a variety of methods to stay informed, such as reading scientific journals, attending conferences, and networking with other researchers. This shows that you have the initiative to stay current and can think critically about how to apply new developments to your work.

Talk about the strategies you use to stay informed. For example, do you read scientific journals? Do you attend conferences and seminars? Do you network with other researchers in your field? You can also talk about how you apply this knowledge to your work. Talk about how you use new developments to inform your research or develop new methods for conducting experiments.

Example: “I stay up-to-date on new developments in my field by reading scientific journals and attending conferences, seminars, and networking events. I also use online resources to keep abreast of the latest research and findings. For example, I’m a member of several professional organizations that share information about new discoveries and advancements in our field. With this knowledge, I’m able to apply current research to my own work and develop innovative methods for conducting experiments.”

7. How do you handle conflicting opinions or interpretations of data within a team?

Research scientists often work in teams, and it’s important to know how you’d handle differences in opinion or interpretation of data. The interviewer wants to know if you can be flexible and open to new ideas, or if you’re more likely to stick to your own views and interpretations. They’ll also want to know if you can work collaboratively with other researchers, and if you’re able to come up with creative solutions to complex problems.

To answer this question, you should explain how you’d approach a situation in which opinions or interpretations of data conflict. You could talk about the importance of open dialogue and collaboration between team members, and how you would facilitate such conversations. You can also discuss your ability to be flexible and consider different perspectives, as well as your willingness to work together with other researchers to come up with creative solutions that everyone is happy with.

Example: “I believe that when it comes to conflicting opinions or interpretations of data, the most important thing is to be open to dialogue and discussion. I understand that everyone has their own perspective and experiences with a particular problem, so I always try to create an environment where team members can express those views without fear of judgment. This helps us gain different insights into the issue at hand and encourages creative solutions. I’m also comfortable taking a step back and looking at the bigger picture to ensure we’re all on the same page—and if not, I’m confident in my ability to work collaboratively with other researchers to come up with a solution that works for everyone.”

8. Describe a time when you had to troubleshoot an experiment that wasn’t producing expected results.

Research scientists need to have the skills to troubleshoot experiments that don’t turn out as expected. This could mean analyzing data to identify possible sources of error, coming up with alternative hypotheses and testing strategies, or reaching out to colleagues for advice. This question will help the interviewer understand how you approach problem-solving, your resourcefulness in difficult situations, and your ability to think critically and come up with creative solutions.

To answer this question, you should provide a specific example of when you had to troubleshoot an experiment. Describe the steps you took to identify and address the problem, what resources you used (e.g., colleagues, literature, etc.), and how you ultimately solved the issue. If possible, describe the results of your efforts and any lessons learned that you can apply to future experiments.

Example: “I recently had to troubleshoot a project that wasn’t producing the expected results. I first identified the possible sources of error by analyzing the data and examining the experimental procedure. Then, I reached out to a colleague who had experience with similar experiments and asked for her advice. Based on her feedback, I adjusted the experimental parameters and re-ran the experiment. The results were much closer to the expected outcome, and I was able to identify several key factors that had been overlooked in the initial setup. This experience taught me the importance of asking for help when needed and being willing to adjust the parameters of an experiment if necessary.”

9. What is your experience with writing scientific papers and presenting findings at conferences?

Scientific research is an ongoing process of experimentation, data collection, and analysis. It is also a field that is highly collaborative and results-driven, which means that research scientists need to be able to communicate their findings in order to be successful. This question is designed to assess your ability to communicate your findings in both written and verbal formats.

Be sure to provide concrete examples of your experience in writing scientific papers and presenting findings at conferences. If you have published any papers, be sure to mention this as it shows that your work is highly regarded by the scientific community. Additionally, if you have ever presented your research at a conference or symposium, talk about what you learned from the experience and how it helped you grow as a researcher. Finally, highlight any awards or recognitions you may have received for your work.

Example: “I have extensive experience in writing scientific papers and presenting findings at conferences. I have published several papers in peer-reviewed journals, and I have presented findings at numerous conferences, symposiums, and other events. I have also received awards for my research, including a prize for best paper presented at a major international conference. Presenting my research to an audience is something I really enjoy, as it allows me to share my findings with a larger audience and receive feedback from other researchers and professionals in the field.”

10. How do you approach developing hypotheses and testing them through experimentation?

The scientific method is the basis of any scientific research and understanding how you approach it is key to know whether you’ll be successful in this role. The interviewer will want to know that you’re able to develop hypotheses, use the right tools to test them, and draw meaningful conclusions from the results. They’ll also want to make sure you have the critical thinking skills to work through complex problems and the creativity to come up with innovative solutions.

This question is designed to assess your ability to think critically, develop hypotheses and test them through experimentation. To answer this question, you should explain the steps you take when approaching a problem. For example, you could discuss how you brainstorm potential solutions, evaluate each solution’s feasibility, create an experiment plan, execute experiments, analyze data, draw conclusions from the results, and present those findings. You should also emphasize any experience you have with designing experiments, collecting data, and analyzing the results of your experiments.

Example: “When I approach developing hypotheses and testing them through experimentation, I start by brainstorming potential solutions and evaluating each solution’s feasibility. Then, I create an experiment plan and execute the experiments. After that, I analyze the data, draw conclusions from the results, and present those findings. I have extensive experience designing experiments, collecting data, and analyzing the results of my experiments. I am confident in my ability to use the scientific method to evaluate hypotheses and draw meaningful conclusions from the results.”

11. What techniques do you use to identify potential sources of bias in experimental design?

Researchers must have an understanding of the potential sources of bias that could affect their experiment, and the ability to identify them quickly. By asking this question, the interviewer wants to know that the candidate can identify potential sources of bias and has the experience to design experiments that will minimize the risk of bias.

To answer this question, you should discuss the techniques that you use to identify potential sources of bias in experimental design. Common techniques include conducting a literature review and using statistical tests such as ANOVA or chi-squared tests. You can also mention methods such as blinding, randomization, and replication. Additionally, you should explain how these techniques help minimize the risk of bias in your experiments.