Was Frederick Jackson Turner’s Frontier Thesis Myth or Reality?

Two scholars debate this question.

Written by: (Claim A) Andrew Fisher, William & Mary; (Claim B) Bradley J. Birzer, Hillsdale College

Suggested sequencing.

- Use this Point-Counterpoint with the Frederick Jackson Turner, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” 1893 Primary Source to give students more background on individualism and western expansion.

Issue on the Table

Was Turner’s thesis a myth about the individualism of the American character and the influence of the West or was it essentially correct in explaining how the West and the advancing frontier contributed to the shaping of individualism in the American character?

Instructions

Read the two arguments in response to the question, paying close attention to the supporting evidence and reasoning used for each. Then, complete the comparison questions that follow. Note that the arguments in this essay are not the personal views of the scholars but are illustrative of larger historical debates.

Every nation has a creation myth, a simple yet satisfying story that inspires pride in its people. The United States is no exception, but our creation myth is all about exceptionalism. In his famous essay, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” Frederick Jackson Turner claimed that the process of westward expansion had transformed our European ancestors into a new breed of people endowed with distinctively American values and virtues. In particular, the frontier experience had supposedly fostered democracy and individualism, underpinned by the abundance of “free land” out West. “So long as free land exists,” Turner wrote, “the opportunity for a competency exists, and economic power secures political power.” It was a compelling articulation of the old Jeffersonian Dream. Like Jefferson’s vision, however, Turner’s thesis excluded much of the nation’s population and ignored certain historical realities concerning American society.

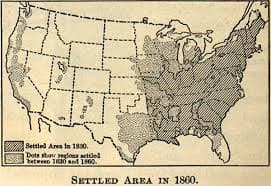

Very much a man of his times, Turner filtered his interpretation of history through the lens of racial nationalism. The people who counted in his thesis, literally and figuratively, were those with European ancestry—and especially those of Anglo-Saxon origins. His definition of the frontier, following that of the U.S. Census, was wherever population density fell below two people per square mile. That effectively meant “where white people were scarce,” in the words of historian Richard White; or, as Patricia Limerick puts it, “where white people got scared because they were scarce.” American Indians only mattered to Turner as symbols of the “savagery” that white pioneers had to beat back along the advancing frontier line. Most of the “free land” they acquired in the process came from the continent’s vast indigenous estate, which, by 1890, had been reduced to scattered reservations rapidly being eroded by the Dawes Act. Likewise, Mexican Americans in the Southwest saw their land base and economic status whittled away after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo that nominally made them citizens of the United States. Chinese immigrants, defined as perpetual aliens under federal law, could not obtain free land through the Homestead Act. For all these groups, Euro-American expansion and opportunity meant the contraction or denial of their own ability to achieve individual advancement and communal stability.

Turner also exaggerated the degree of social mobility open to white contemporaries, not to mention their level of commitment to an ideology of rugged individualism. Although plenty of Euro-Americans used the homestead laws to get their piece of free land, they often struggled to make that land pay and to keep it in the family. During the late nineteenth century, the commoditization and industrialization of American agriculture caught southern and western farmers in a crushing cost-price squeeze that left many wrecked by debt. To combat this situation, they turned to cooperative associations such as the Grange and the National Farmers’ Alliance, which blossomed into the Populist Party at the very moment Turner was writing about the frontier as the engine of American democracy. Perhaps it was, but not in the sense he understood. Populists railed against the excess of individualism that bred corruption and inequality in Gilded Age America. Even cowboys, a pillar of the frontier myth, occasionally tried to organize unions to improve their wages and working conditions. Those seeking a small stake of their own—what Turner called a “competency”— in the form of their own land or herds sometimes ran afoul of concentrated capital, as during the Johnson County War of 1892. The big cattlemen of the Wyoming Stockgrowers Association had no intention of sharing the range with pesky sodbusters and former cowboys they accused of rustling. Their brand of individualism had no place for small producers who might become competitors.

Turner took such troubles as a sign that his prediction had come true. With the closing of the frontier, he said, the United States would begin to see greater class conflict in the form of strikes and radical politics. There was lots of free land left in 1890, though; in fact, approximately 1 million people filed homestead claims between 1901 and 1913, compared with 1.4 million between 1862 and 1900. That did not prevent the country from experiencing serious clashes between organized labor and the corporations that had come to dominate many industries. Out west, socialistic unions such as the Western Federation of Miners and the Industrial Workers of the World challenged not only the control that companies had over their employees but also their influence in the press and politics. For them, Turner’s dictum that “economic power secures political power” would have held a more sinister meaning. It was the rise of the modern corporation, not the supposed fading of the frontier, that narrowed the meanings of individualism and opportunity as Americans had previously understood them.

Young historian Frederick Jackson Turner presented his academic paper, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago on July 12, 1893. He was the final presenter of that hot and humid day, but his essay ranks among the most influential arguments ever made regarding American history.

Turner was trained at the University of Wisconsin (his home state) and Johns Hopkins University, then the center of Germanic-type graduate studies—that is, it was scientific and objectivist rather than idealist or liberal. Turner rebelled against that purely scientific approach, but not by much. In 1890, the U.S. Census revealed that the frontier (defined as fewer than two people per square mile) was closed. There was no longer an unbroken frontier line in the United States, although frontier conditions lasted in certain parts of the American West until 1920. Turner lamented this, believing the most important phase of American history was over.

No one publicly commented on the essay at the time, but the American Historical Association reprinted it in its annual report the following year, and within a decade, it became known as the “Turner Thesis.”

What is most prominent in the Turner Thesis is the proposition that the United States is unique in its heritage; it is not a European clone, but a vital mixture of European and American Indian. Or, as he put it, the American character emerged through an intermixing of “savagery and civilization.” Turner attributed the American character to the expansion to the West, where, he said, American settlers set up farms to tame the frontier. “The existence of an area of free land, its continuous recession, and the advance of American settlement westward, explain American development.” As people moved west in a “perennial rebirth,” they extended the American frontier, the boundary “between savagery and civilization.”

The frontier shaped the American character because the settlers who went there had to conquer a land difficult for farming and devoid of any of the comforts of life in urban parts of the East: “The frontier is the line of most rapid and effective Americanization. The wilderness masters the colonist. It finds him a European in dress, industries, tools, modes of travel, and thought. It takes him from the railroad car and puts him in the birch canoe. It strips off the garments of civilization and arrays him in the hunting shirt and the moccasin. It puts him in the log cabin of the Cherokee and Iroquois and runs an Indian palisade around him. Before long he has gone to planting Indian corn and plowing with a sharp stick; he shouts the war cry and takes the scalp in orthodox Indian fashion. In short, at the frontier the environment is at first too strong for the man. He must accept the conditions which it furnishes, or perish, and so he fits himself into the Indian clearings and follows the Indian trails.”

Politically and socially, according to Turner, the American character—including traits that prioritized equality, individualism, and democracy—was shaped by moving west and settling the frontier. “The tendency,” Turner wrote, “is anti-social. [The frontier] produces antipathy to control, and particularly to any direct control.” Those hardy pioneers on the frontier spread the ideas and practice of democracy as well as modern civilization. By conquering the wilderness, Turner stressed, they learned that resources and opportunity were seemingly boundless, meant to bring the ruggedness out of each individual. The farther west the process took them, the less European the Americans as a whole became. Turner saw the frontier as the progenitor of the American practical and innovative character: “That coarseness and strength combined with acuteness and acquisitiveness; that practical, inventive turn of mind, quick to find expedients; that masterful grasp of material things, lacking the artistic but powerful to effect great ends; that restless, nervous energy; that dominant individualism, working for good and for evil, and withal that buoyancy and exuberance which comes with freedom – these are trains of the frontier.”

Turner’s thesis, to be sure, viewed American Indians as uncivilized. In his vision, they cannot compete with European technology, and they fall by the wayside, serving as little more than a catalyst for the expansion of white Americans. This near-absence of Indians from Turner’s argument gave rise to a number of critiques of his thesis, most prominently from the New Western Historians beginning in the 1980s. These more recent historians sought to correct Turner’s “triumphal” myth of the American West by examining it as a region rather than as a process. For Turner, the American West is a progressive process, not a static place. There were many Wests, as the process of conquering the land, changing the European into the American, happened over and over again. What would happen to the American character, Turner wondered, now that its ability to expand and conquer was over?

Historical Reasoning Questions

Use Handout A: Point-Counterpoint Graphic Organizer to answer historical reasoning questions about this point-counterpoint.

Primary Sources (Claim A)

Cooper, James Fenimore. Last of the Mohicans (A Leatherstocking Tale) . New York: Penguin, 1986.

Turner, Frederick Jackson. “The Significance of the Frontier in American History.” http://sunnycv.com/steve/text/civ/turner.html

Primary Sources (Claim B)

Suggested resources (claim a).

Cronon, William, George Miles, and Jay Gitlin, eds. Under an Open Sky: Rethinking America’s Western Past . New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1992.

Faragher, John Mack. Women and Men on the Overland Trail . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2001.

Grossman, Richard R, ed. The Frontier in American Culture: Essays by Richard White and Patricia Nelson Limerick . Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1994.

Limerick, Patricia Nelson. The Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past of the American West . New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1987.

Limerick, Patricia Nelson, Clyde A. Milner II, and Charles E. Rankin, eds. Trails: Toward a New Western History . Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1991.

Milner II, Clyde A. A New Significance: Re-envisioning the History of the American West . New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Nugent, Walter. Into the West: The Story of Its People . New York: Knopf, 1991.

Slotkin, Richard. The Fatal Environment: The Myth of the Frontier in the Age of Industrialization, 1800-1890 . Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1998.

Suggested Resources (Claim B)

Billington, Ray Allen, and Martin Ridge. Westward Expansion: A History of the American Frontier . Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2001.

Etulain, Richard, ed. Does the Frontier Experience Make America Exceptional? New York: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 1999.

Mondi. Megan. “’Connected and Unified?’: A More Critical Look at Frederick Jackson Turner’s America.” Constructing the Past , 7 no. 1:Article 7. http://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/constructing/vol7/iss1/7

Nelson, Robert. “Public Lands and the Frontier Thesis.” Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States , Digital Scholarship Lab, University of Richmond, 2014. http://dsl.richmond.edu/fartherafield/public-lands-and-the-frontier-thesis/

More from this Category

Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness

In our resource history is presented through a series of narratives, primary sources, and point-counterpoint debates that invites students to participate in the ongoing conversation about the American experiment.

How the Myth of the American Frontier Got Its Start

Frederick Jackson Turner’s thesis informed decades of scholarship and culture. Then he realized he was wrong

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Colin_Woodard_PPH_Photo_crop_thumbnail_1.png)

Colin Woodard

:focal(400x301:401x302)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/12/11/1211e4cd-7311-4c83-9370-d86aa5ebc2d5/illustration_of_people_on_horseback_looking_at_an_open_landscape.jpg)

On the evening of July 12, 1893, in the hall of a massive new Beaux-Arts building that would soon house the Art Institute of Chicago, a young professor named Frederick Jackson Turner rose to present what would become the most influential essay in the study of U.S. history.

It was getting late. The lecture hall was stifling from a day of blazing sun, which had tormented the throngs visiting the nearby Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition, a carnival of never-before-seen wonders, like a fully illuminated electric city and George Ferris’ 264-foot-tall rotating observation wheel. Many of the hundred or so historians attending the conference, a meeting of the American Historical Association (AHA), were dazed and dusty from an afternoon spent watching Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show at a stadium near the fairground’s gates. They had already sat through three other speeches. Some may have been dozing off as the thin, 31-year-old associate professor from the University of Wisconsin in nearby Madison began his remarks.

Subscribe to Smithsonian magazine now for just $19.99

This article is a selection from the January/February 2023 issue of Smithsonian magazine

Turner told them the force that had forged Americans into one people was the frontier of the Midwest and Far West. In this virgin world, settlers had finally been relieved of the European baggage of feudalism that their ancestors had brought across the Atlantic, freeing them to find their true selves: self-sufficient, pragmatic, egalitarian and civic-minded. “The frontier promoted the formation of a composite nationality for the American people,” he told the audience. “In the crucible of the frontier, the immigrants were Americanized, liberated and fused into a mixed race, English in neither nationality nor characteristics.”

The audience was unmoved.

In their dispatches the following morning, most of the newspaper reporters covering the conference didn’t even mention Turner’s talk. Nor did the official account of the proceedings prepared by the librarian William F. Poole for The Dial , an influential literary journal. Turner’s own father, writing to relatives a few days later, praised Turner’s skills as the family’s guide at the fair, but he said nothing at all about the speech that had brought them there.

Yet in less than a decade, Turner would be the most influential living historian in the United States, and his Frontier Thesis would become the dominant lens through which Americans understood their character, origins and destiny. Soon, Jackson’s theme was prevalent in political speech, in the way high schools taught history, in patriotic paintings—in short, everywhere. Perfectly timed to meet the needs of a country experiencing dramatic and destabilizing change, Turner’s thesis was swiftly embraced by academic and political institutions, just as railroads, manufacturing machines and telegraph systems were rapidly reshaping American life.

By that time, Turner himself had realized that his theory was almost entirely wrong.

American historians had long believed that Providence had chosen their people to spread Anglo-Saxon freedom across the continent. As an undergraduate at the University of Wisconsin, Turner was introduced to a different argument by his mentor, the classical scholar William Francis Allen. Extrapolating from Darwinism, Allen believed societies evolved like organisms, adapting themselves to the environments they encountered. Scientific laws, not divine will, he advised his mentee, guided the course of nations. After graduating, Turner pursued a doctorate at Johns Hopkins University, where he impressed the history program’s leader, Herbert Baxter Adams, and formed a lifelong friendship with one of his teachers, an ambitious young professor named Woodrow Wilson. The connections were useful: When Allen died in 1889, Adams and Wilson aided Turner in his quest to take Allen’s place as head of Wisconsin’s history department. And on the strength of Turner’s early work, Adams invited him to present a paper at the 1893 meeting of the AHA, to be held in conjunction with the World’s Congress Auxiliary of the World’s Columbian Exposition.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/61/bc/61bc38a7-853f-4c6b-823e-71c95d62687d/manifest_destiny.jpg)

The resulting essay, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” offered a vivid evocation of life in the American West. Stripped of “the garments of civilization,” settlers between the 1780s and the 1830s found themselves “in the birch canoe” wearing “the hunting shirt and the moccasin.” Soon, they were “planting Indian corn and plowing with a sharp stick” and even shouting war cries. Faced with Native American resistance—Turner largely overlooked what the ethnic cleansing campaign that created all that “free land” might say about the American character—the settlers looked to the federal government for protection from Native enemies and foreign empires, including during the War of 1812, thus fostering a loyalty to the nation rather than to their half-forgotten nations of origin.

He warned that with the disappearance of the force that had shaped them—in 1890, the head of the Census Bureau concluded there was no longer a frontier line between areas that had been settled by European Americans and those that had not—Americans would no longer be able to flee west for an easy escape from responsibility, failure or oppression. “Each frontier did indeed furnish a new field of opportunity, a gate of escape from the bondage of the past,” Turner concluded. “Now … the frontier has gone, and with its going has closed the first period of American history.”

When he left the podium on that sweltering night, he could not have known how fervently the nation would embrace his thesis.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/3a/1d/3a1d78c2-4533-4dbf-9fc9-66306936b710/white_guy.jpg)

Like so many young scholars, Turner worked hard to bring attention to his thesis. He incorporated it into the graduate seminars he taught, lectured about it across the Midwest and wrote the entry for “Frontier” in the widely read Johnson’s Universal Cyclopædia. He arranged to have the thesis reprinted in the journal of the Wisconsin Historical Society and in the AHA’s 1893 annual report. Wilson championed it in his own writings, and the essay was read by hundreds of schoolteachers who found it reprinted in the popular pedagogical journal of the Herbart Society, a group devoted to the scientific study of teaching. Turner’s big break came when the Atlantic Monthly ’s editors asked him to use his novel viewpoint to explain the sudden rise of populists in the rural Midwest, and how they had managed to seize control of the Democratic Party to make their candidate, William Jennings Bryan, its nominee for president. Turner’s 1896 Atlantic Monthly essay , which tied the populists’ agitation to the social pressures allegedly caused by the closing of the frontier—soil depletion, debt, rising land prices—was promptly picked up by newspapers and popular journals across the country.

Meanwhile, Turner’s graduate students became tenured professors and disseminated his ideas to the up-and-coming generation of academics. The thrust of the thesis appeared in political speeches, dime-store western novels and even the new popular medium of film, where it fueled the work of a young director named John Ford who would become the master of the Hollywood western. In 1911, Columbia University’s David Muzzey incorporated it into a textbook—initially titled History of the American People —that would be used by most of the nation’s secondary schools for half a century.

Americans embraced Turner’s argument because it provided a fresh and credible explanation for the nation’s exceptionalism—the notion that the U.S. follows a path soaring above those of other countries—one that relied not on earlier Calvinist notions of being “the elect,” but rather on the scientific (and fashionable) observations of Charles Darwin. In a rapidly diversifying country, the Frontier Thesis denied a special role to the Eastern colonies’ British heritage; we were instead a “composite nation,” birthed in the Mississippi watershed. Turner’s emphasis on mobility, progress and individualism echoed the values of the Gilded Age—when readers devoured Horatio Alger’s rags-to-riches stories—and lent them credibility for the generations to follow.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ea/69/ea696129-c32c-4947-9ce7-64648e2f2cea/janfeb2023_e01_prologue.jpg)

But as a researcher, Turner himself turned away from the Frontier Thesis in the years after the 1890s. He never wrote it down in book form or even in academic articles. He declined invitations to defend it, and before long he himself lost faith in it.

For one thing, he had been relying too narrowly on the experiences in his own region of the Upper Midwest, which had been colonized by a settlement stream originating in New England. In fact, he found, the values he had ascribed to the frontier’s environmental conditioning were actually those of this Greater New England settlement culture, one his family and most of his fellow citizens in Portage, Wisconsin, remained part of, with their commitment to strong village and town governments, taxpayer-financed public schools and the direct democracy of the town meeting. He saw that other parts of the frontier had been colonized by other settlement streams anchored in Scots-Irish Appalachia or in the slave plantations of the Southern lowlands, and he noted that their populations continued to behave completely differently from one another, both politically and culturally, even when they lived in similar physical environments. Somehow settlers moving west from these distinct regional cultures were resisting the Darwinian environmental and cultural forces that had supposedly forged, as Turner’s biographer, Ray Allen Billington, put it, “a new political species” of human, the American. Instead, they were stubbornly remaining themselves. “Men are not absolutely dictated to by climate, geography, soils or economic interests,” Turner wrote in 1922. “The influence of the stock from which they sprang, the inherited ideals, the spiritual factors, often triumph over the material interests.”

Turner spent the last decades of his life working on what he intended to be his magnum opus, a book not about American unity but rather about the abiding differences between its regions, or “sections,” as he called them. “In respect to problems of common action, we are like what a United States of Europe would be,” he wrote in 1922, at the age of 60. For example, the Scots-Irish and German small farmers and herders who settled the uplands of the southeastern states had long clashed with nearby English enslavers over education spending, tax policy and political representation. Turner saw the whole history of the country as a wrestling match between these smaller quasi-nations, albeit a largely peaceful one guided by rules, laws and shared American ideals: “When we think of the Missouri Compromise, the Compromise of 1850, the Kansas-Nebraska Act, as steps in the marking off of spheres of influence and the assignment of mandates [between nations] … we see a resemblance to what has gone on in the Old World,” Turner explained. He hoped shared ideals—and federal institutions—would prove cohesive for a nation suddenly coming of age, its frontier closed, its people having to steward their lands rather than striking out for someplace new.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ea/79/ea79b5eb-7dd4-4ca0-9d75-f4ad5333a116/janfeb2023_e12_prologue.jpg)

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Colin_Woodard_PPH_Photo_crop_thumbnail_1.png)

Colin Woodard | | READ MORE

Colin Woodard is a journalist and historian, and the author of six books including Union: The Struggle to Forge the Story of United States Nationhood . He lives in Maine.

We’re fighting to restore access to 500,000+ books in court this week. Join us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

The frontier in American history

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

4 Favorites

Better World Books

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

In collections.

Uploaded by associate-joseph-ondreicka on April 10, 2023

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

The Significance of the Frontier in American History

by Frederick Jackson Turner

Teacher (K-12)

Ph.D. from University of North Carolina at Greensboro

Educator since 2011

36 contributions

Ph.D in early American history and M.A. I taught literature as well as European, world, and US history in public high schools for ten years.

Last Updated September 5, 2023.

"The Significance of the Frontier in American History" was written by Frederick Jackson Turner, delivered as a conference paper at the annual meeting of the American Historical Association in 1893, and published in that organization's Annual Report . There is much to this essay, which in many ways marks the rise of professional historiography. At its heart is the so-called "frontier thesis," Jackson Turner's explanation for what has made the United States unique, or "exceptional," as most people of his time believed it to be.

The "frontier thesis" essentially is that the United States is unique because it has always had a frontier with "free land" available. For this reason, people have always been able to move westward. On the frontier, Turner thought, white men brought European ways that they had to adapt to the rugged conditions in these hinterlands. The mix of frontier-ready culture and European "civilization" was, for Turner, uniquely American, forged on the frontier, the "outer edge of the wave—the meeting point between savagery and civilization." Turner also thought that American democracy depended on the existence of free land. He thought that without its existence, large working classes would arise and become revolutionaries, creating a toxic environment for democracy as he understood it.

Turner, in short, saw the American frontier as the key to American democracy, and, in a scholarly vein, the key to a valid historical understanding of the nation. In this sense, his essay was a call to other historians to look to the frontier in their work. His essay has been roundly criticized for its reductionism and especially for his treatment of Native Americans, who he essentially characterized as part of the frontier landscape to be swept away. The phrase "free land" is especially arresting to modern readers who reflect that there were Native Americans on this territory that was supposedly there for the taking. Also, written just three years after the "closing" of the American frontier, the essay reads like a call for imperialism—a new frontier that will revitalize American democracy.

On the other hand, Turner's thesis moved away from the essentialist racial theories that dominated thinking about nationalism at the time. He sought to explain American history and culture by looking at a material fact (free land), however ethnocentric that "fact" may have been. Overlooked, too, is the fact that Turner was afraid of the effects of the domination of the west by railroads, mining companies, and other corporate behemoths that kept it from becoming a place ordinary Americans could settle in the late nineteenth century. For these reasons, "The Significance of the Frontier in American History," while generally rejected by modern scholars, remains a milestone in American historiography.

Cite this page as follows:

Cranford, Alec. "The Significance of the Frontier in American History - Summary." eNotes Publishing, edited by eNotes Editorial, eNotes.com, Inc., 29 June 2024 <https://www.enotes.com/topics/significance-frontier-american-history-frederick#summary-summary-845343>

Professional Writer, Professional Tutor

Educator since 2018

39 contributions

Professional tutor and Economics major.

This book is divided into two parts. The first section talks about the American frontier. Over the years, migration and political decisions have defined the US's borders. This process began with the movement of Europeans to the New World. They discovered vast lands with agricultural potential and began farming. With time, the settlers established ports to transport their farm produce to the rest of the world. As more settlers moved to America, land became a precious commodity, and the settlers fought with native peoples for more territory.

The second section talks about the effects of the frontier on the rest of the world. The prosperity of the US has attracted immigrants from different nationalities. The success of the American frontier is also determined by its administrative system—the federal government handles all important national matters, including budgetary allocation to different departments, while the state governments deal with state affairs. All in all, this essay gives a neat account of the US's history and how its size has contributed to its economic prosperity.

Wamaitha, Stephen. "The Significance of the Frontier in American History - Summary." eNotes Publishing, edited by eNotes Editorial, eNotes.com, Inc., 29 June 2024 <https://www.enotes.com/topics/significance-frontier-american-history-frederick#summary-summary-832648>

See eNotes Ad-Free

Start your 48-hour free trial to get access to more than 30,000 additional guides and more than 350,000 Homework Help questions answered by our experts.

Already a member? Log in here.

Why was the Turner Thesis abandoned by historians

Fredrick Jackson Turner’s thesis of the American frontier defined the study of the American West during the 20th century. In 1893, Turner argued that “American history has been in a large degree the history of the colonization of the Great West. The existence of an area of free land, its continuous recession, and the advance of American settlement westward explain American development.” ( The Frontier in American History , Turner, p. 1.) Jackson believed that westward expansion allowed America to move away from the influence of Europe and gain “independence on American lines.” (Turner, p. 4.) The conquest of the frontier forced Americans to become smart, resourceful, and democratic. By focusing his analysis on people in the periphery, Turner de-emphasized the importance of everyone else. Additionally, many people who lived on the “frontier” were not part of his thesis because they did not fit his model of the democratizing American. The closing of the frontier in 1890 by the Superintendent of the census prompted Turner’s thesis.

While appealing, the Turner thesis stultified scholarship on the West. In 1984, colonial historian James Henretta even stated, “[f]or, in our role as scholars, we must recognize that the subject of westward expansion in itself longer engages the attention of many perhaps most, historians of the United States.” ( Legacy of Conquest , Patricia Limerick, p. 21.) Turner’s thesis had effectively shaped popular opinion and historical scholarship of the American West, but the thesis slowed continued academic interest in the field.

Reassessment of Western History

In the last half of the twentieth century, a new wave of western historians rebelled against the Turner thesis and defined themselves by their opposition to it. Historians began to approach the field from different perspectives and investigated the lives of Women, miners, Chicanos, Indians, Asians, and African Americans. Additionally, historians studied regions that would not have been relevant to Turner. In 1987, Patricia Limerick tried to redefine the study of the American West for a new generation of western scholars. In Legacy of Conquest, she attempted to synthesize the scholarship on the West to that point and provide a new approach for re-examining the West. First, she asked historians to think of the America West as a place and not as a movement. Second, she emphasized that the history of the American West was defined by conquest; “[c]onquest forms the historical bedrock of the whole nation, and the American West is a preeminent case study in conquest and its consequences.” (Limerick, p. 22.)

Finally, she asked historians to eliminate the stereotypes from Western history and try to understand the complex relations between the people of the West. Even before Limerick’s manifesto, scholars were re-evaluating the west and its people, and its pace has only quickened. Whether or not scholars agree with Limerick, they have explored new depths of Western American history. While these new works are not easy to categorize, they do fit into some loose categories: gender ( Relations of Rescue by Peggy Pascoe), ethnicity ( The Roots of Dependency by Richard White, and Lewis and Clark Among the Indians by James P. Rhonda), immigration (Impossible Subjects by Ming Ngai), and environmental (Nature’s Metropolis by William Cronon, Rivers of Empire by Donald Worster) history. These are just a few of the topics that have been examined by American West scholars. This paper will examine how these new histories of the American West resemble or diverge from Limerick’s outline.

Defining America or a Threat to America's Moral Standing

Unlike Limerick, Pascoe did not find it necessary to define the west or the frontier. She did not have to because the Protestant missionaries in her story defined it for her. While Turner may have believed that the West was no longer the frontier in 1890, the missionaries certainly would have disagreed. In fact, the rescue missions were placed in the communities that the Victorian Protestant missionary judged to be the least “civilized” parts of America (Lakota Territory, San Francisco’s Chinatown, rough and tumble Denver and Salt Lake City.) Instead of being a story of conquest by Victorian or western morality, it was a story of how that morality was often challenged and its terms were negotiated by culturally different communities. Pascoe’s primary goal in this work was not only to eliminate stereotypes but to challenge the notion that white women civilized the west. While conquest may be a component of other histories, no one group in Pascoe’s story successfully dominated any other.

Changing the Narrative of Native Americans in the West

Two books were written before Legacy was published, Lewis and Clark Among the Indians (James Rhonda) and The Roots of Dependency (Richard White) both provide a window into the world of Native Americans. Both books took new approaches to Native American histories. Rhonda’s book looked at the familiar Lewis and Clark expedition but from an entirely different angle. Rhonda described the interactions between the expedition and the various Native American tribes they encountered. White’s book also sought to describe the interactions between the United States and the Choctaws, Pawnees, and Navajos, but he sought to explain why the economies of these tribes broke down after contact. Each of these books covers new ground by addressing the impact of these interactions between the United States and the Native Americans.

Instead of describing the initial interactions of the United States government with the Choctaws, Pawnees, and Navajos, White explained how the self-sufficient economies of these people were destroyed. White described how the United States government turned these successful native people into wards of the American state. His story explained how the United States conquered these tribes without firing a shot. The consequence of this conquest was the creation of weak, dependent nations that could not survive without handouts from the federal government. Like Rhonda, White also sought to shatter long-standing stereotypes and myths regarding Native Americans. White verified that each of these tribes had self-sufficient economies which permitted prosperous lifestyles for their people before the devastating interactions with the United States government occurred. The United States in each case fundamentally altered the tribes’ economies and environments. These alterations threatened the survival of the tribes. In some cases, the United States sought to trade with these tribes in an effort put the tribes in debt. After the tribes were in debt, the United States then forced the tribes to sell their land. In other situations, the government damaged the tribes’ economies even when they sought to help them.

The Impact of Immigrants to the West

While illegal immigration is not an issue isolated to the history of the American West, the immigrants moved predominantly into California, Texas and the American Southwest. Like Anglo settlers who were attracted to the West for the potential for new life in the nineteenth century, illegal immigrants continued to move in during the twentieth. The illegal immigrants were welcomed, despite their status, because California’s large commercial farms needed inexpensive labor to harvest their crops. Impossible Subjects describes four groups of illegal immigrants (Filipinos, Japanese, Chinese and Mexican braceros) who were created by the United States immigration policy. Ngai specifically examines the role that the government played in defining, controlling and disciplining these groups for their allegedly illegal misconduct.

The Rise of Western Environmental History

In Nature’s Metropolis , Cronon, used the central place theory to analyze the economic and ecological development of Chicago. Johann Heinrich von Thunen developed the central place theory to explain the development of cities. Essentially, geographically different economic zones form in concentric circles the farther you went from the city. These different zones form because of the time it takes to get the different types of goods to market. Closest to the city and then moving away you would have the following zones: first, intensive agriculture, second, extensive agriculture, third, livestock raising, fourth, trading, hunting and Indian trade and finally, you would have the wilderness. While the landscape of the Mid-West was more complicated than this, Cronon posits that the “city and country are inextricably connected and that market relations profoundly mediate between them.” (Cronon, p. 52.) By emphasizing the connection between the city of Chicago and the rural lands that surrounded it, Cronon was able to explain how the land, including the West, developed. Cronon argued that the development of Chicago had a profound influence on the development and appearance of the Great West. Essentially Cronon used the creation of the Chicago commodities and trading markets to explain how different parts of the Mid-West and West produced different types of resources and fundamentally altered their ecology.

According to Donald Worster’s Rivers of Empire, economics played an equally important role in the economic and environmental development of the Rocky Mountain and Pacific Slope states. Worster argued that the United States wanted to continue creating family farms for Americans in the West. Unfortunately, the aridity of the west made that impossible. The land in the West simply could not be farmed without water. Instead of adapting to the natural environment, the United States government embarked on the largest dam building project in human history. The government built thousands of dams to irrigate millions of acres of land. Unfortunately, the cost of these numerous irrigation projects was enormous. The federal government passed the cost on to the buyers of the land which prevented family farmers from buying it. Therefore, instead of family farms, massive commercial farms were created. The only people who could afford to buy the land were wealthy citizens. The massive irrigation also permitted the creation of cities which never would have been possible without it. Worster argues that the ensuing ecological damage to the West has been extraordinary. The natural environment throughout the region was dramatically altered. The west is now the home of oversized commercial farms, artificial reservoirs which stretch for hundreds of miles, rivers that run only on command and sprawling cities which depend on irrigation.

Each of these books demonstrates that the Turner thesis no longer holds a predominant position in the scholarship of the American West. The history of the American West has been revitalized by its demise. While westward expansion plays an important role in the history of the United States, it did not define the west. Turner’s thesis was fundamentally undermined because it did not provide an accurate description of how the West was peopled. The nineteenth century of the west is not composed primarily of family farmers. Instead, it is a story of a region peopled by a diverse group of people: Native Americans, Asians, Chicanos, Anglos, African Americans, women, merchants, immigrants, prostitutes, swindlers, doctors, lawyers, farmers are just a few of the characters who inhabit western history.

Suggested Readings

| One basic theme of America's collective attitude about itself is what is referred to as “exceptionalism”—the notion that America as a nation has occupied a special niche in the history of world cultures by offering freedom of opportunity to all comers. Critics of the notion point to Amercan slavery, our troubled civil rights history, etc., and argue that the idea of American exceptionalism is self-serving and jingoistic. Frederick Jackson Turner remains one of the most influential historians of America's past, and his famous frontier thesis is related to the above idea, in that his basic idea is that constant contact with an open frontier for almost 300 years of American history contributed to America's uniqueness—or exceptionalism. He presented his thesis, "The Significance of the Frontier in American History," to a gathering of American historians in Chicago in 1893. Over time, Turner's ideas came to be so well known that one historians has called it “the single most influential piece of writing in the history of American history.” Turner's conclusion, that the most important effect of the frontier was to promote individualistic democracy, has been both criticized and incorporated into various texts on America. From colonial times to the late 19th century, Turner argues, the value of individual labor and the ubiquity of opportunity contributed to American democratic ideals and discouraged monopolies on political power from developing.

Excerpt: In a recent bulletin of the Superintendent of the Census for 1890 appear these significant words: “Up to and including 1880 the country had a frontier of settlement, but at present the unsettled area has been so broken into by isolated bodies of settlement that there can hardly be said to be a frontier line. In the discussion of its extent, its westward movement, etc., it cannot, therefore, any longer have a place in the census reports.” This brief official statement marks the closing of a great historic movement. Up to our own day American history has been in a large degree the history of the colonization of the Great West. The existence of an area of free land, its continuous recession, and the advance of American settlement westward, explain American development. Behind institutions, behind constitutional forms and modifications, lie the vital forces that call these organs into life and shape them to meet changing conditions. The peculiarity of American institutions is, the fact that they have been compelled to adapt themselves to the changes of an expanding people—to the changes involved in crossing a continent, in winning a wilderness, and in developing at each area of this progress out of the primitive economic and political conditions of the frontier into the complexity of city life. Said Calhoun in 1817, "We are great, and rapidly—I was about to say fearfully—growing!" So saying, he touched the distinguishing feature of American life.... American development has exhibited not merely advance along a single line, but a return to primitive conditions on a continually advancing frontier line, and a new development for that area. American social development has been continually beginning over again on the frontier. This perennial rebirth, this fluidity of American life, this expansion westward with its new opportunities, its continuous touch with the simplicity of primitive society, furnish the forces dominating American character. The true point of view in the history of this nation is not the Atlantic coast, it is the great West.... The frontier is the line of most rapid and effective Americanization. The wilderness masters the colonist. It finds him a European in dress, industries, tools, modes of travel, and thought. It takes him from the railroad car and puts him in the birch canoe. It strips off the garments of civilization and arrays him in the hunting shirt and the moccasin. It puts him in the log cabin of the Cherokee and Iroquois and runs an Indian palisade around him. Before long he has gone to planting Indian corn and plowing with a sharp stick; he shouts the war cry and takes the scalp in orthodox Indian fashion. In short, at the frontier the environment is at first too strong for the man. He must accept the conditions which it furnishes, or perish, and so he fits himself into the Indian clearings and follows the Indian trails. Little by little he transforms the wilderness, but the outcome is not the old Europe, not simply the development of Germanic germs, any more than the first phenomenon was a case of reversion to the Germanic mark. The fact is, that here is a new product that is American.... The Middle region, entered by New York harbor, was an open door to all Europe.... It had a wide mixture of nationalities, a varied society, the mixed town and county system of local government, a varied economic life, many religious sects. In short, it was a region mediating between New England and the South, and the East and the West. It represented that composite nationality which the contemporary United States exhibits, that juxtaposition of non-English groups occupying a valley or a little settlement, and presenting reflections of the map of Europe in their variety. It was democratic and nonsectional, if not national; "easy, tolerant, and contented;" rooted strongly in material prosperity. It was typical of the modern United States.... But the most important effect of the frontier has been in the, promotion of democracy here and in Europe. As has been indicated, the frontier is productive of individualism. Complex society is precipitated by the wilderness into a kind of primitive organization based on the family. The tendency is anti-social. It produces antipathy to control, and particularly to any direct control. The tax-gatherer is viewed as a representative of oppression. So long as free land exists, the opportunity for a competency exists, and economic power secures political power. But the democracy born of free land, strong in selfishness and individualism, intolerant of administrative experience and education, and pressing individual liberty beyond its proper bounds, has its dangers as well as its benefits. Individualism in America has allowed a laxity, in regard to governmental affairs which has rendered possible the spoils system and all the manifest evils that follow from the lack of a highly developed civic spirit. In this connection may be noted also the influence of frontier conditions in permitting lax business honor inflated paper currency and wild-cat banking. The colonial and revolutionary frontier was the region whence emanated many of the worst forms of an evil currency. The West in the war of 1812 repeated the phenomenon on the frontier of that day, while the speculation and wild-cat banking of the period of the crisis of 1837 occurred on the new frontier belt of the next tier of States. Thus each one of the periods of lax financial integrity coincides with periods when a new set of frontier communities had arisen, and coincides in area with these successive frontiers, for the most part. The recent Populist agitation is a case in point. Many a State that now declines any connection with the tenets of the Populists, itself adhered to such ideas in an earlier Stage of the development of the State. A primitive society can hardly be expected to show the intelligent appreciation of the complexity of business interests in a developed society. | Updated |

Last updated 27/06/24: Online ordering is currently unavailable due to technical issues. We apologise for any delays responding to customers while we resolve this. For further updates please visit our website: https://www.cambridge.org/news-and-insights/technical-incident

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Journals

- > Journal of American Studies

- > Volume 27 Issue 2

- > Frederick Jackson Turner's Frontier Thesis and the...

Article contents

Frederick jackson turner's frontier thesis and the self-consciousness of america.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 16 January 2009

In their work on Turner's formative period, Ray A. Billington and Fulmer Mood have shown that the Frontier Thesis, formulated in 1893 in “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” is not so much a brilliant early effort by a young scholar as a mature study in which Turner gave his ideas an organization that proved to be final. During the rest of his life he developed but never disclaimed or modified them. Billington and Mood also add that the Frontier Thesis is meant to test a new approach to history that Turner had been developing since the beginning of his academic career. We can fully understand it, then, only by setting it within the framework of the assumptions and goals of his 1891 essay, “The Significance of History,” Turner's only attempt to sketch a philosophy of history.

Access options

1 Billington , Ray A. , The Genesis of the Frontier Thesis: A Study in Historical Creativity ( San Marino, Ca. : The Huntington Library , 1971 ) Google Scholar ; Mood , Fulmer , “ The Development of Frederick J.Turner as a Historical Thinker ,” Transactions of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts , 1937–42, 34 ( 1943 ), 283 – 352 . Google Scholar

2 Turner , Frederick J. , “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” Proceedings of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin , 14 12 1893 . Google Scholar

3 Turner , Frederick J. , “ The Significance of History ,” Wisconsin Journal of Education , 21 ( 10 1891 ), 230 –4, ( 11 1891 ), 253–6. Google Scholar

4 Turner , , “The Significance of History,” in Frontier and Section: Selected Essays of F. J. Turner , Billington , Ray A. ed. ( Englewood Cliffs, N.J. : Prentice-Hall , 1961 ), 20 . Google Scholar

5 Turner , , “The Significance of History,” 17 . Google Scholar

7 Ibid. , 18.

8 Ibid. , 27.

9 Ibid. , 18.

10 Turner , Frederick J. , “Problems in American History,” in Frontier and Section , Billington, ed., 29 . Google Scholar

11 Billington , Ray A. , Frederick J. Turner: Historian, Scholar, Teacher ( New York : Oxford University Press , 1973 ), chapter 5 Google Scholar ; Coleman , William , “ Science and Symbol in Turner Frontier Hypothesis ,” American Historical Review , 72 , 3 ( 1966 ), 22 – 49 . CrossRef Google Scholar

12 Turner , , “The Significance of the Frontier,” 1 – 2 Google Scholar ; see also “Problems in American History,” 29 . Google Scholar

13 Turner , , “The Significance of the Frontier,” 2 . Google Scholar

14 The link between the “instinct for moving” and the development of human history and culture was forcefully made by Turner in an 1891 address to the Madison Literary Club: “The colonizing spirit is one form of the nomadic instinct. The immigrant train on its way to the far west or the steamer laden with passengers for Australia is but the last embodiment of the impulse that took Abraham out of Ur of the Chaldees and sent our Aryan forefathers from their primitive pasture lands to Greece and Italy and India and Scandinavia”: Turner , Frederick J. , “American Colonization,” published in Carpenter , Ronald H. , The Eloquence of Frederick J. Turner ( San Marino, Ca. : The Huntington Library , 1893 ), 176 . Google Scholar

15 Turner , , “The Significance of the Frontier,” 11 . Google Scholar

16 See, for instance, his treatment of populism, “The Significance of the Frontier,” 32 . Google Scholar

17 Ibid. , 37.

18 Ibid. , 4.

19 Turner , , “The Problem of the West,” in Frontier and Section , Billington ed, 206 Google Scholar ; also: “At first the frontier was the Atlantic coast. It was the frontier of Europe in a very real sense. Moving westward, the frontier became more and more American,” Turner , , “The Significance of the Frontier,” 4 . Google Scholar

20 Foucault , Michel , L'ordre du discours ( Paris : 1970 ). Google Scholar

21 See, Trails: Toward a New Western History , Limerick , Patricia Nelson , Milner , Clyde A. II , Rankin , Charles E. eds. ( University Press of Kansas ). CrossRef Google Scholar

22 Turner , , “The Significance of the Frontier,” 3 – 4 . Google Scholar

23 Turner , , “The Problem of the West,” 205 . Google Scholar

24 Ibid. , 207.

25 Turner , , “The Significance of the Frontier,” 2 . Google Scholar

26 See Morgan , Lewis Henry , Ancient Society ( 1877 ). Google Scholar

27 Billington , , Frederick Jackson Turner , 76 –9, 122–3. Google Scholar

28 Turner , , “The Significance of the Frontier,” 21 , 38. Google Scholar

29 Ibid. , 12.

30 Ibid. , 4.

31 Turner , , “The Problem of the West,” 205 . Google Scholar

32 See Morgan , Lewis H. , Ancient Society ( 1877 ) Google Scholar , and Bagehot , Walter , Physics and Politics: An Application of the Principles of Natural Selection and Heredity to Political Society ( 1872 ) Google Scholar , on the first and second points respectively. The pervasive influence in late 19th century culture of Sumner Maine's theory of the transition from status to contract should also be kept in mind.

33 Turner , , “The Significance of the Frontier,” 30 . Google Scholar

34 Ibid. , 37; “The problem of the West,” 211 . Google Scholar

35 Ibid. , quoted.

36 Turner , , “The Significance of the Frontier,” 31 . Google Scholar

37 Turner , , “The Problem of the West,” 213 . Google Scholar

38 Billington , , Frederick Jackson Turner , 425 . Google Scholar

39 Bonazzi , Tiziano , “Un'analisi della American Promise: ordine e senso nel discorso storico-politico,” in Bonazzi , Tiziano , Struttura e metamorfosi della civilta' progressista ( Venezia : Marsilio , 1974 ), 41 – 140 . Google Scholar

40 Baritz , Loren , “ The Idea of the West ,” American Historical Review , 66 , 3 ( 1961 ), 618 –40. CrossRef Google Scholar An important parallel can also be made with Walzer , Michael , Exodus and Revolution ( New York : Basic Books , 1985 ). Google Scholar

41 Smith , Henry Nash , Virgin Land: The American West As Symbol and Myth ( Cambridge, Mass. : Harvard University Press , 1950 ). Google Scholar On the importance of foundation myths, see Voegelin , Eric , The New Science of Politics ( Chicago : University of Chicago Press , 1952 ). Google Scholar

42 Noble , David W. , Historians against History. The Frontier Thesis and the National Covenant in American Historical Writing since 1830 ( Minneapolis : University of Minnesota Press , 1965 ) Google Scholar , and The End of American History ( Minneapolis : University of Minnesota Press , 1985 ). Google Scholar

43 Turner , to Becker , Carl , 21 01 1911 Google Scholar , in Jacobs , Wilbur R. , The Historical World of Frederick J. Turner ( New Haven-London : Yale University Press , 1968 ), 135 Google Scholar ; also, Turner , to Skinner , Constance Lindsay , 15 03 1922 Google Scholar , in Jacobs , , The Historical World , 56 . Google Scholar

44 Turner , , “Problems in American History,” 29 . Google Scholar

45 Ibid. , 32.

46 Turner , , “The Problem of the West,” 68 –9. Google Scholar

47 Ibid. , 69. This expression follows immediately upon the sentence previously quoted.

48 Turner , , “The Significance of the Frontier,” 38 . Google Scholar

49 Turner , to Becker , Carl , in Jacobs , , The Historical World , 135 . Google Scholar

50 Turner , , “Contributions of the West to American Democracy,” Google Scholar in Turner , , The Frontier in American History , 264 –6. Google Scholar

51 Ibid. , 258.

52 Turner , , “The Problem of the West,” 216 . Google Scholar

53 Turner , , “The West and American Ideals,” Google Scholar in Turner , , The Frontier in American History , 305 . Google Scholar

54 Turner , , “Social Forces in American History,” Google Scholar in Turner , , The Frontier in American History , 331 . Google Scholar

55 Turner , , “Pioneer Ideals and the State University,” Google Scholar in Turner , , The Frontier in American History , 284 . Google Scholar

56 Turner , , “The State University,” in America's Great Frontier and Sections: Frederick Jackson Turner's Unpublished Essays , Jacobs , Wilbur R. ed. ( Lincoln : University of Nebraska Press , 1969 ), 196 . Google Scholar

57 Turner , , “The West and American Ideals,” 300 . Google Scholar

58 See his “Pioneer Ideals and the State University,” 269 –89. Google Scholar

59 Turner , , “The Significance of History,” in Frontier and Section , Billington ed., 21 . Google Scholar

60 Ibid. , 18.

61 Lyotard , Jean-Francois , La condition postmoderne ( Paris : Les Editions de Minuit , 1979 ). Google Scholar

62 Reference is made here to Wallerstein , Immanuel , The Modern World-System ( New York : Academic Press , 1976 ). Google Scholar

63 Bercovitch , Sacvan , The American Jeremiad ( Madison : Wisconsin University Press , 1978 ) Google Scholar ; also Bercovitch , Sacvan , “The Rites of Assent: Rhetoric, Ritual, and the Ideology of American Consensus,” in The American Self: Myth, Ideology and Popular Culture , Girgus , Sam B. ed. ( Albuquerque : New Mexico University Press , 1980 ), 5 – 45 . Google Scholar On the “rhetorical impact” of the Frontier Thesis upon the American public mind see Carpenter , Ronald H. , The Eloquence of F. J. Turner , 47 – 95 . Google Scholar

64 Wiebe , Robert H. , The Search for Order , 1877–1920 ( New York : Hill and Wang , 1967 ), ch. 5. Google Scholar

65 The idea of a transition from an age of scarcity to an age of abundance was articulated by Patten , Simon N. , professor of economics at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, in The New Basis of Civilization ( New York : Macmillan , 1907 ). Google Scholar

66 Tudor , Henry , Political Myth ( London : 1972 ) CrossRef Google Scholar ; also, Bonazzi , Tiziano , “Mito politico,” in Dizionario di politico , Bobbio , Norberto and Matteucci , Nicola eds. ( Torino : UTET , 1976 ), 587 –94. Google Scholar The most important interpretation of politics based on the dialectics amicus-hostis is that of Carl Schmitt, see, among his many publications, Der Bergriff des Politischen. Text von 1932 mit einem Vorwort und drei Corollarien (Berlin: Duncker und Humblot, 1963 ). Google Scholar

67 Barthes , Ronald , Mythologies ( Paris : Editions du Seuil , 1957 ). Google Scholar

68 See Turner's articles on immigration in Chicago Record-Herald , 28 08 , 4, 11, 18, 25 09 , 16 10 1901 . Google Scholar Let us not forget, however, that Marcus Hansen was one of Turner's students.

69 Derrida , Jacques , L'autre cap ( Paris : Les Editions de Minuit , 1991 ). Google Scholar

70 Turner , , “The Significance of the Frontier,” 3 . Google Scholar

This article has been cited by the following publications. This list is generated based on data provided by Crossref .

- Google Scholar

View all Google Scholar citations for this article.

Save article to Kindle

To save this article to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service.

- Volume 27, Issue 2

- Tiziano Bonazzi (a1)

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021875800031509

Save article to Dropbox

To save this article to your Dropbox account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Dropbox account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save article to Google Drive

To save this article to your Google Drive account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Google Drive account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

Reply to: Submit a response

- No HTML tags allowed - Web page URLs will display as text only - Lines and paragraphs break automatically - Attachments, images or tables are not permitted

Your details

Your email address will be used in order to notify you when your comment has been reviewed by the moderator and in case the author(s) of the article or the moderator need to contact you directly.

You have entered the maximum number of contributors

Conflicting interests.

Please list any fees and grants from, employment by, consultancy for, shared ownership in or any close relationship with, at any time over the preceding 36 months, any organisation whose interests may be affected by the publication of the response. Please also list any non-financial associations or interests (personal, professional, political, institutional, religious or other) that a reasonable reader would want to know about in relation to the submitted work. This pertains to all the authors of the piece, their spouses or partners.

The American Yawp Reader

Frederick jackson turner, “significance of the frontier in american history” (1893).

Perhaps the most influential essay by an American historian, Frederick Jackson Turner’s address to the American Historical Association on “The Significance of the Frontier in American History” defined for many Americans the relationship between the frontier and American culture and contemplated what might follow “the closing of the frontier.”

In a recent bulletin of the Superintendent of the Census for 1890 appear these significant words: “Up to and including 1880 the country had a frontier of settlement, but at present the unsettled area has been so broken into by isolated bodies of settlement that there can hardly be said to be a frontier line. In the discussion of its extent, its westward movement, etc., it can not, therefore, any longer have a place in the census reports.” This brief official statement marks the closing of a great historic movement. Up to our own day American history has been in a large degree the history of the colonization of the Great West. The existence of an area of free land, its continuous recession, and the advance of American settlement westward, explain American development.

Behind institutions, behind constitutional forms and modifications, lie the vital forces that call these organs into life and shape them to meet changing conditions. The peculiarity of American institutions is, the fact that they have been compelled to adapt themselves to the changes of an expanding people—to the changes involved in crossing a continent, in winning a wilderness, and in developing at each area of this progress out of the primitive economic and political conditions of the frontier into the complexity of city life. Said Calhoun in 1817, “We are great, and rapidly—I was about to say fearfully—growing!” So saying, he touched the distinguishing feature of American life. All peoples show development; the germ theory of politics has been sufficiently emphasized. In the case of most nations, however, the development has occurred in a limited area; and if the nation has expanded, it has met other growing peoples whom it has conquered. But in the case of the United States we have a different phenomenon. Limiting our attention to the Atlantic coast, we have the familiar phenomenon of the evolution of institutions in a limited area, such as the rise of representative government; the differentiation of simple colonial governments into complex organs; the progress from primitive industrial society, without division of labor, up to manufacturing civilization. But we have in addition to this a recurrence of the process of evolution in each western area reached in the process of expansion. Thus American development has exhibited not merely advance along a single line, but a return to primitive conditions on a continually advancing frontier line, and a new development for that area. American social development has been continually beginning over again on the frontier. This perennial rebirth, this fluidity of American life, this expansion westward with its new opportunities, its continuous touch with the simplicity of primitive society, furnish the forces dominating American character. The true point of view in the history of this nation is not the Atlantic coast, it is the Great West. …

In this advance, the frontier is the outer edge of the wave—the meeting point between savagery and civilization. Much has been written about the frontier from the point of view of border warfare and the chase, but as a field for the serious study of the economist and the historian it has been neglected.

From the conditions of frontier life came intellectual traits of profound importance. The works of travelers along each frontier from colonial days onward describe certain common traits, and these traits have, while softening down, still persisted as survivals in the place of their origin, even when a higher social organization succeeded. The result is that to the frontier the American intellect owes its striking characteristics. That coarseness and strength combined with acuteness and inquisitiveness; that practical, inventive turn of mind, quick to find expedients; that masterful grasp of material things, lacking in the artistic but powerful to effect great ends; that restless, nervous energy; that dominant individualism, working for good and for evil, and withal that buoyancy and exuberance which comes with freedom—these are traits of the frontier, or traits called out elsewhere because of the existence of the frontier. Since the days when the fleet of Columbus sailed into the waters of the New World, America has been another name for opportunity, and the people of the United States have taken their tone from the incessant expansion which has not only been open but has even been forced upon them. He would be a rash prophet who should assert that the expansive character of American life has now entirely ceased. Movement has been its dominant fact, and, unless this training has no effect upon a people, the American energy will continually demand a wider field for its exercise. But never again will such gifts of free land offer themselves. For a moment, at the frontier, the bonds of custom are broken and unrestraint is triumphant. There is not tabula rasa . The stubborn American environment is there with its imperious summons to accept its conditions; the inherited ways of doing things are also there; and yet, in spite of environment, and in spite of custom, each frontier did indeed furnish a new field of opportunity, a gate of escape from the bondage of the past; and freshness, and confidence, and scorn of older society, impatience of its restraints and its ideas, and indifference to its lessons, have accompanied the frontier. What the Mediterranean Sea was to the Greeks, breaking the bond of custom, offering new experiences, calling out new institutions and activities, that, and more, the ever retreating frontier has been to the United States directly, and to the nations of Europe more remotely. And now, four centuries from the discovery of America, at the end of a hundred years of life under the Constitution, the frontier has gone, and with its going has closed the first period of American history.

Source: Frederick Jackson Turner, The Frontier in American History, 1919.

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Eastern Europe

- Moscow Oblast

Elektrostal

Elektrostal Localisation : Country Russia , Oblast Moscow Oblast . Available Information : Geographical coordinates , Population, Area, Altitude, Weather and Hotel . Nearby cities and villages : Noginsk , Pavlovsky Posad and Staraya Kupavna .

Information

Find all the information of Elektrostal or click on the section of your choice in the left menu.

- Update data

| Country | |

|---|---|

| Oblast |

Elektrostal Demography

Information on the people and the population of Elektrostal.

| Elektrostal Population | 157,409 inhabitants |

|---|---|

| Elektrostal Population Density | 3,179.3 /km² (8,234.4 /sq mi) |

Elektrostal Geography

Geographic Information regarding City of Elektrostal .

| Elektrostal Geographical coordinates | Latitude: , Longitude: 55° 48′ 0″ North, 38° 27′ 0″ East |

|---|---|

| Elektrostal Area | 4,951 hectares 49.51 km² (19.12 sq mi) |

| Elektrostal Altitude | 164 m (538 ft) |

| Elektrostal Climate | Humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification: Dfb) |

Elektrostal Distance

Distance (in kilometers) between Elektrostal and the biggest cities of Russia.

Elektrostal Map

Locate simply the city of Elektrostal through the card, map and satellite image of the city.

Elektrostal Nearby cities and villages

Elektrostal Weather

Weather forecast for the next coming days and current time of Elektrostal.

Elektrostal Sunrise and sunset

Find below the times of sunrise and sunset calculated 7 days to Elektrostal.

| Day | Sunrise and sunset | Twilight | Nautical twilight | Astronomical twilight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23 June | 02:41 - 11:28 - 20:15 | 01:40 - 21:17 | 01:00 - 01:00 | 01:00 - 01:00 |

| 24 June | 02:41 - 11:28 - 20:15 | 01:40 - 21:16 | 01:00 - 01:00 | 01:00 - 01:00 |

| 25 June | 02:42 - 11:28 - 20:15 | 01:41 - 21:16 | 01:00 - 01:00 | 01:00 - 01:00 |

| 26 June | 02:42 - 11:29 - 20:15 | 01:41 - 21:16 | 01:00 - 01:00 | 01:00 - 01:00 |

| 27 June | 02:43 - 11:29 - 20:15 | 01:42 - 21:16 | 01:00 - 01:00 | 01:00 - 01:00 |

| 28 June | 02:44 - 11:29 - 20:14 | 01:43 - 21:15 | 01:00 - 01:00 | 01:00 - 01:00 |

| 29 June | 02:44 - 11:29 - 20:14 | 01:44 - 21:15 | 01:00 - 01:00 | 01:00 - 01:00 |

Elektrostal Hotel

Our team has selected for you a list of hotel in Elektrostal classified by value for money. Book your hotel room at the best price.

| Located next to Noginskoye Highway in Electrostal, Apelsin Hotel offers comfortable rooms with free Wi-Fi. Free parking is available. The elegant rooms are air conditioned and feature a flat-screen satellite TV and fridge... | from | |

| Located in the green area Yamskiye Woods, 5 km from Elektrostal city centre, this hotel features a sauna and a restaurant. It offers rooms with a kitchen... | from | |

| Ekotel Bogorodsk Hotel is located in a picturesque park near Chernogolovsky Pond. It features an indoor swimming pool and a wellness centre. Free Wi-Fi and private parking are provided... | from | |

| Surrounded by 420,000 m² of parkland and overlooking Kovershi Lake, this hotel outside Moscow offers spa and fitness facilities, and a private beach area with volleyball court and loungers... | from | |

| Surrounded by green parklands, this hotel in the Moscow region features 2 restaurants, a bowling alley with bar, and several spa and fitness facilities. Moscow Ring Road is 17 km away... | from | |

Elektrostal Nearby

Below is a list of activities and point of interest in Elektrostal and its surroundings.

Elektrostal Page

| Direct link | |

|---|---|

| DB-City.com | Elektrostal /5 (2021-10-07 13:22:50) |

- Information /Russian-Federation--Moscow-Oblast--Elektrostal#info

- Demography /Russian-Federation--Moscow-Oblast--Elektrostal#demo

- Geography /Russian-Federation--Moscow-Oblast--Elektrostal#geo

- Distance /Russian-Federation--Moscow-Oblast--Elektrostal#dist1

- Map /Russian-Federation--Moscow-Oblast--Elektrostal#map

- Nearby cities and villages /Russian-Federation--Moscow-Oblast--Elektrostal#dist2

- Weather /Russian-Federation--Moscow-Oblast--Elektrostal#weather

- Sunrise and sunset /Russian-Federation--Moscow-Oblast--Elektrostal#sun

- Hotel /Russian-Federation--Moscow-Oblast--Elektrostal#hotel

- Nearby /Russian-Federation--Moscow-Oblast--Elektrostal#around

- Page /Russian-Federation--Moscow-Oblast--Elektrostal#page

- Terms of Use

- Copyright © 2024 DB-City - All rights reserved

- Change Ad Consent Do not sell my data

- Yekaterinburg

- Novosibirsk

- Vladivostok

- Tours to Russia

- Practicalities

- Russia in Lists

Rusmania • Deep into Russia

Out of the Centre

Savvino-storozhevsky monastery and museum.