How to write a case study — examples, templates, and tools

It’s a marketer’s job to communicate the effectiveness of a product or service to potential and current customers to convince them to buy and keep business moving. One of the best methods for doing this is to share success stories that are relatable to prospects and customers based on their pain points, experiences, and overall needs.

That’s where case studies come in. Case studies are an essential part of a content marketing plan. These in-depth stories of customer experiences are some of the most effective at demonstrating the value of a product or service. Yet many marketers don’t use them, whether because of their regimented formats or the process of customer involvement and approval.

A case study is a powerful tool for showcasing your hard work and the success your customer achieved. But writing a great case study can be difficult if you’ve never done it before or if it’s been a while. This guide will show you how to write an effective case study and provide real-world examples and templates that will keep readers engaged and support your business.

In this article, you’ll learn:

What is a case study?

How to write a case study, case study templates, case study examples, case study tools.

A case study is the detailed story of a customer’s experience with a product or service that demonstrates their success and often includes measurable outcomes. Case studies are used in a range of fields and for various reasons, from business to academic research. They’re especially impactful in marketing as brands work to convince and convert consumers with relatable, real-world stories of actual customer experiences.

The best case studies tell the story of a customer’s success, including the steps they took, the results they achieved, and the support they received from a brand along the way. To write a great case study, you need to:

- Celebrate the customer and make them — not a product or service — the star of the story.

- Craft the story with specific audiences or target segments in mind so that the story of one customer will be viewed as relatable and actionable for another customer.

- Write copy that is easy to read and engaging so that readers will gain the insights and messages intended.

- Follow a standardized format that includes all of the essentials a potential customer would find interesting and useful.

- Support all of the claims for success made in the story with data in the forms of hard numbers and customer statements.

Case studies are a type of review but more in depth, aiming to show — rather than just tell — the positive experiences that customers have with a brand. Notably, 89% of consumers read reviews before deciding to buy, and 79% view case study content as part of their purchasing process. When it comes to B2B sales, 52% of buyers rank case studies as an important part of their evaluation process.

Telling a brand story through the experience of a tried-and-true customer matters. The story is relatable to potential new customers as they imagine themselves in the shoes of the company or individual featured in the case study. Showcasing previous customers can help new ones see themselves engaging with your brand in the ways that are most meaningful to them.

Besides sharing the perspective of another customer, case studies stand out from other content marketing forms because they are based on evidence. Whether pulling from client testimonials or data-driven results, case studies tend to have more impact on new business because the story contains information that is both objective (data) and subjective (customer experience) — and the brand doesn’t sound too self-promotional.

Case studies are unique in that there’s a fairly standardized format for telling a customer’s story. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t room for creativity. It’s all about making sure that teams are clear on the goals for the case study — along with strategies for supporting content and channels — and understanding how the story fits within the framework of the company’s overall marketing goals.

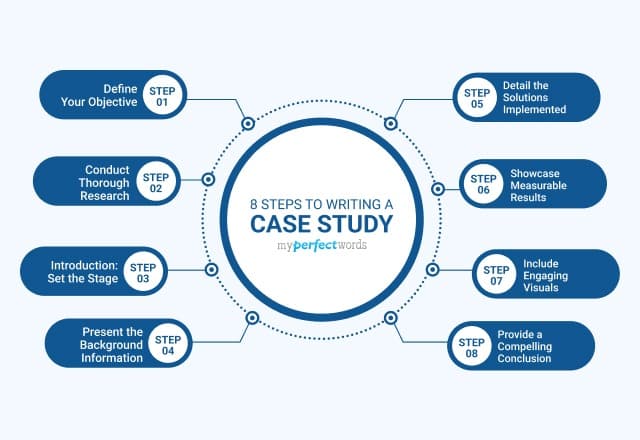

Here are the basic steps to writing a good case study.

1. Identify your goal

Start by defining exactly who your case study will be designed to help. Case studies are about specific instances where a company works with a customer to achieve a goal. Identify which customers are likely to have these goals, as well as other needs the story should cover to appeal to them.

The answer is often found in one of the buyer personas that have been constructed as part of your larger marketing strategy. This can include anything from new leads generated by the marketing team to long-term customers that are being pressed for cross-sell opportunities. In all of these cases, demonstrating value through a relatable customer success story can be part of the solution to conversion.

2. Choose your client or subject

Who you highlight matters. Case studies tie brands together that might otherwise not cross paths. A writer will want to ensure that the highlighted customer aligns with their own company’s brand identity and offerings. Look for a customer with positive name recognition who has had great success with a product or service and is willing to be an advocate.

The client should also match up with the identified target audience. Whichever company or individual is selected should be a reflection of other potential customers who can see themselves in similar circumstances, having the same problems and possible solutions.

Some of the most compelling case studies feature customers who:

- Switch from one product or service to another while naming competitors that missed the mark.

- Experience measurable results that are relatable to others in a specific industry.

- Represent well-known brands and recognizable names that are likely to compel action.

- Advocate for a product or service as a champion and are well-versed in its advantages.

Whoever or whatever customer is selected, marketers must ensure they have the permission of the company involved before getting started. Some brands have strict review and approval procedures for any official marketing or promotional materials that include their name. Acquiring those approvals in advance will prevent any miscommunication or wasted effort if there is an issue with their legal or compliance teams.

3. Conduct research and compile data

Substantiating the claims made in a case study — either by the marketing team or customers themselves — adds validity to the story. To do this, include data and feedback from the client that defines what success looks like. This can be anything from demonstrating return on investment (ROI) to a specific metric the customer was striving to improve. Case studies should prove how an outcome was achieved and show tangible results that indicate to the customer that your solution is the right one.

This step could also include customer interviews. Make sure that the people being interviewed are key stakeholders in the purchase decision or deployment and use of the product or service that is being highlighted. Content writers should work off a set list of questions prepared in advance. It can be helpful to share these with the interviewees beforehand so they have time to consider and craft their responses. One of the best interview tactics to keep in mind is to ask questions where yes and no are not natural answers. This way, your subject will provide more open-ended responses that produce more meaningful content.

4. Choose the right format

There are a number of different ways to format a case study. Depending on what you hope to achieve, one style will be better than another. However, there are some common elements to include, such as:

- An engaging headline

- A subject and customer introduction

- The unique challenge or challenges the customer faced

- The solution the customer used to solve the problem

- The results achieved

- Data and statistics to back up claims of success

- A strong call to action (CTA) to engage with the vendor

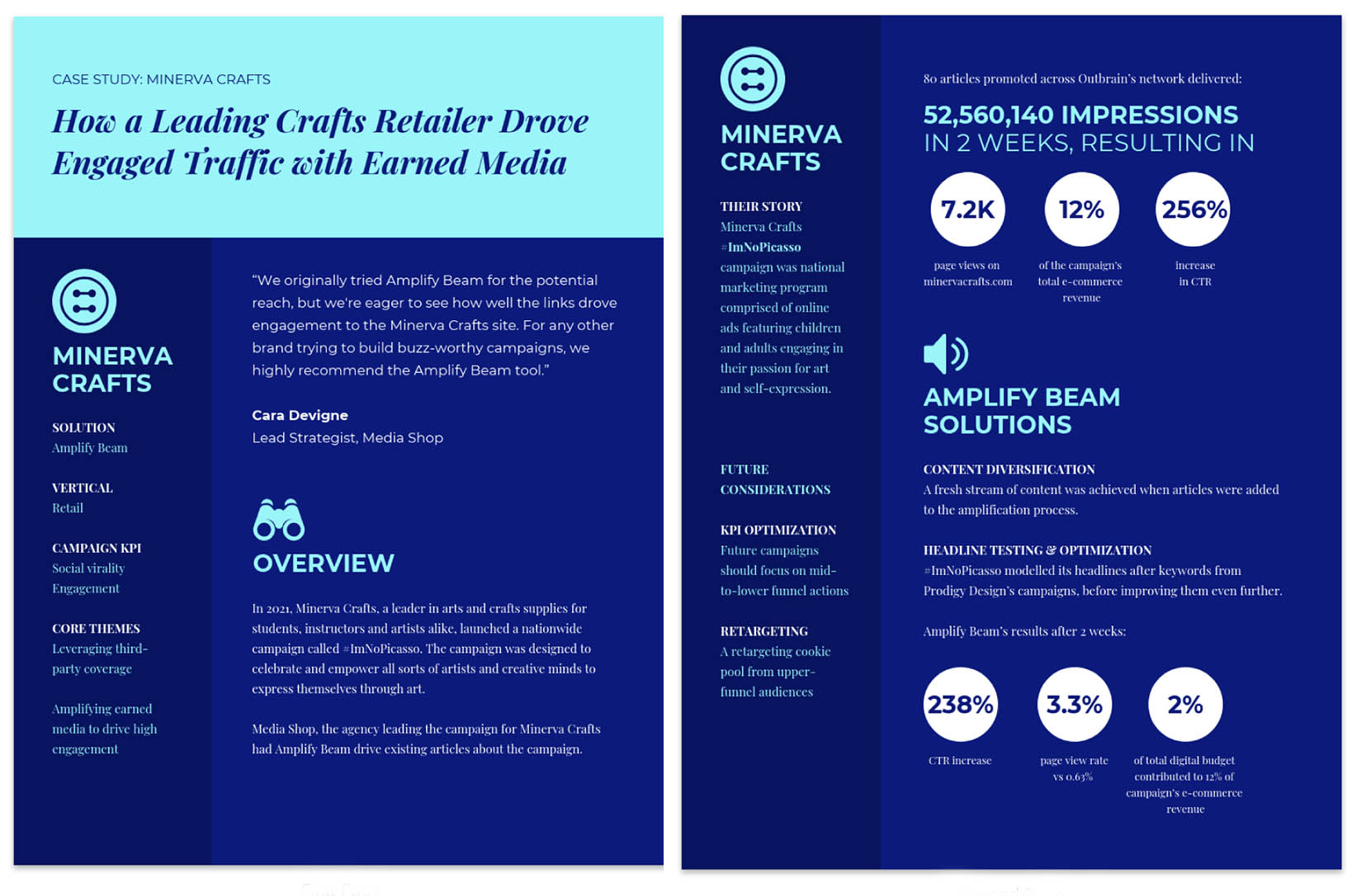

It’s also important to note that while case studies are traditionally written as stories, they don’t have to be in a written format. Some companies choose to get more creative with their case studies and produce multimedia content, depending on their audience and objectives. Case study formats can include traditional print stories, interactive web or social content, data-heavy infographics, professionally shot videos, podcasts, and more.

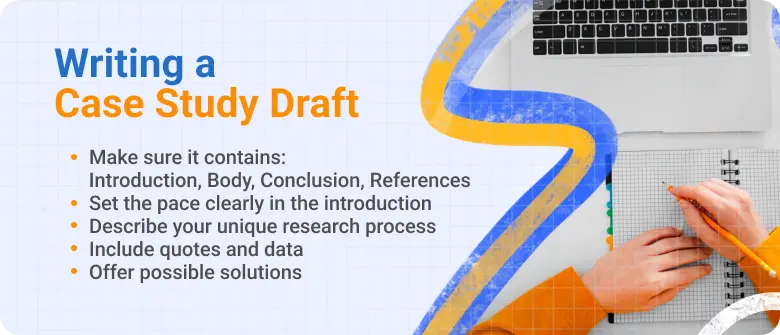

5. Write your case study

We’ll go into more detail later about how exactly to write a case study, including templates and examples. Generally speaking, though, there are a few things to keep in mind when writing your case study.

- Be clear and concise. Readers want to get to the point of the story quickly and easily, and they’ll be looking to see themselves reflected in the story right from the start.

- Provide a big picture. Always make sure to explain who the client is, their goals, and how they achieved success in a short introduction to engage the reader.

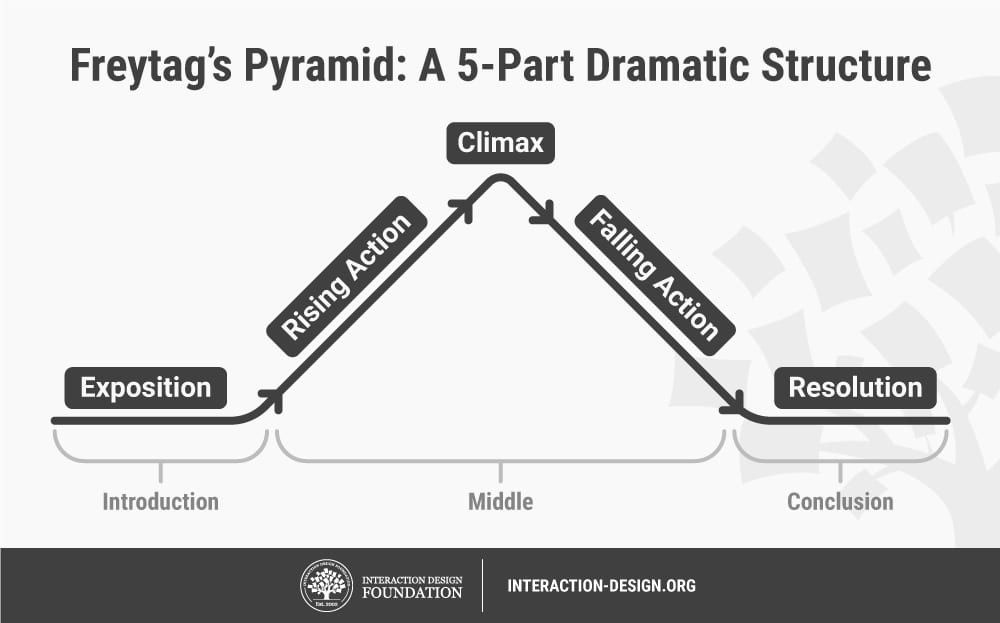

- Construct a clear narrative. Stick to the story from the perspective of the customer and what they needed to solve instead of just listing product features or benefits.

- Leverage graphics. Incorporating infographics, charts, and sidebars can be a more engaging and eye-catching way to share key statistics and data in readable ways.

- Offer the right amount of detail. Most case studies are one or two pages with clear sections that a reader can skim to find the information most important to them.

- Include data to support claims. Show real results — both facts and figures and customer quotes — to demonstrate credibility and prove the solution works.

6. Promote your story

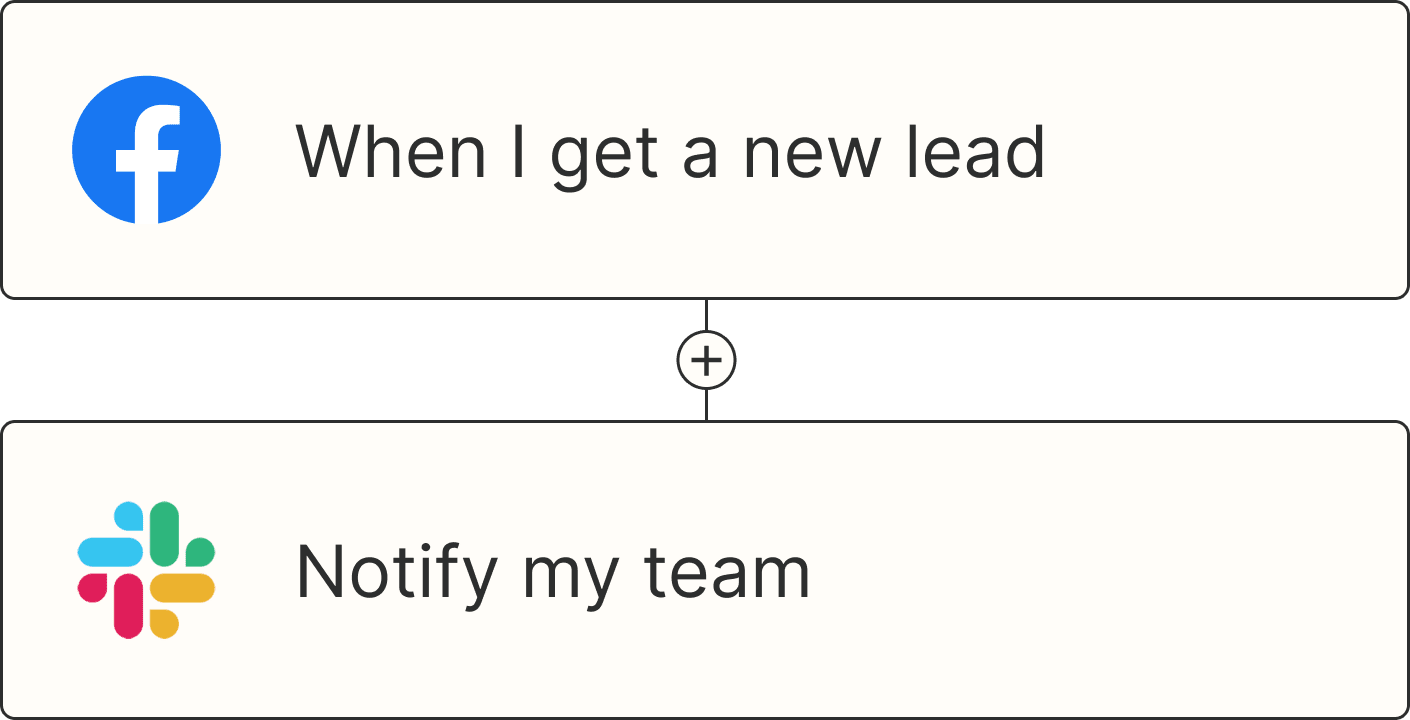

Marketers have a number of options for distribution of a freshly minted case study. Many brands choose to publish case studies on their website and post them on social media. This can help support SEO and organic content strategies while also boosting company credibility and trust as visitors see that other businesses have used the product or service.

Marketers are always looking for quality content they can use for lead generation. Consider offering a case study as gated content behind a form on a landing page or as an offer in an email message. One great way to do this is to summarize the content and tease the full story available for download after the user takes an action.

Sales teams can also leverage case studies, so be sure they are aware that the assets exist once they’re published. Especially when it comes to larger B2B sales, companies often ask for examples of similar customer challenges that have been solved.

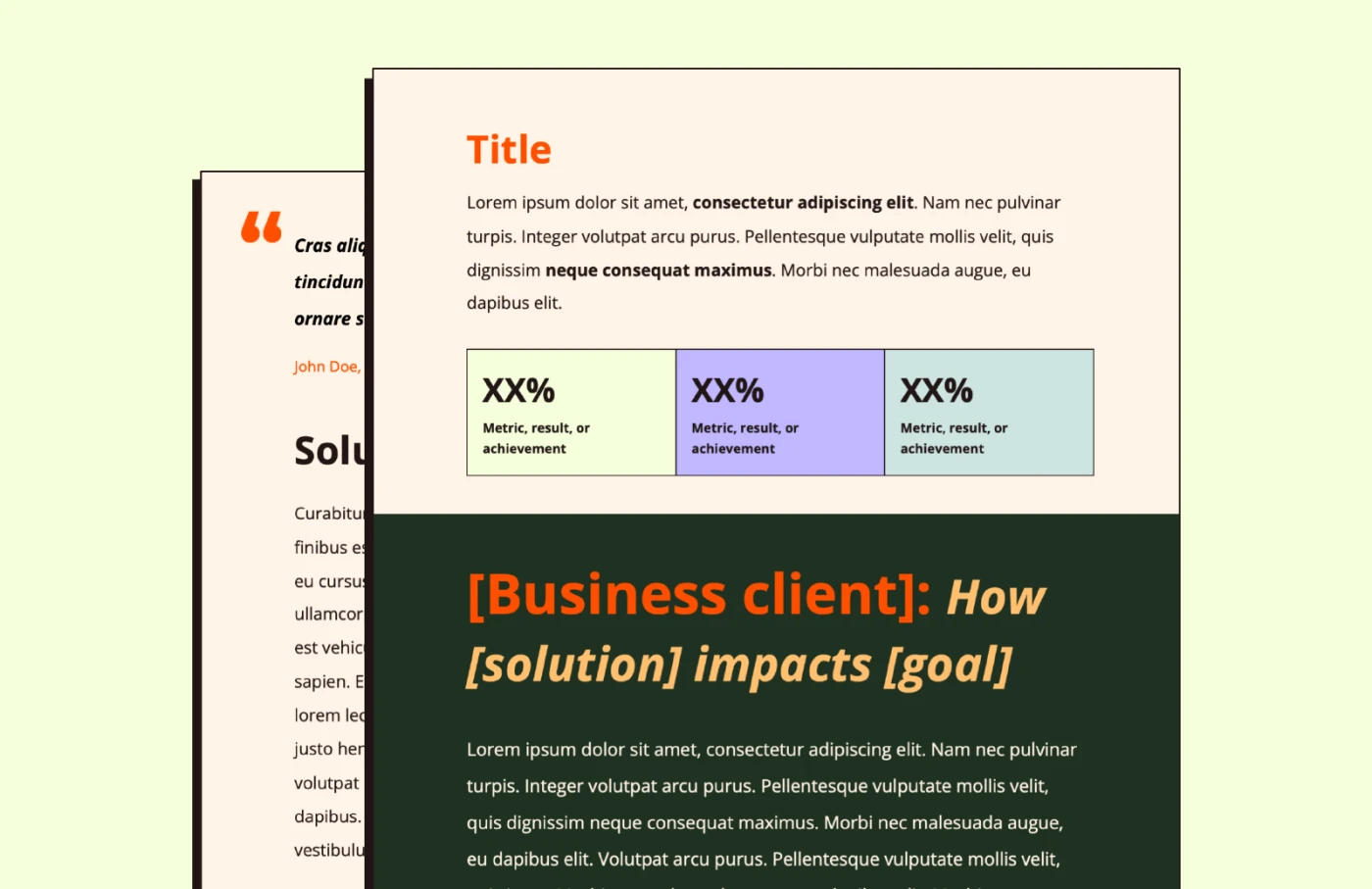

Now that you’ve learned a bit about case studies and what they should include, you may be wondering how to start creating great customer story content. Here are a couple of templates you can use to structure your case study.

Template 1 — Challenge-solution-result format

- Start with an engaging title. This should be fewer than 70 characters long for SEO best practices. One of the best ways to approach the title is to include the customer’s name and a hint at the challenge they overcame in the end.

- Create an introduction. Lead with an explanation as to who the customer is, the need they had, and the opportunity they found with a specific product or solution. Writers can also suggest the success the customer experienced with the solution they chose.

- Present the challenge. This should be several paragraphs long and explain the problem the customer faced and the issues they were trying to solve. Details should tie into the company’s products and services naturally. This section needs to be the most relatable to the reader so they can picture themselves in a similar situation.

- Share the solution. Explain which product or service offered was the ideal fit for the customer and why. Feel free to delve into their experience setting up, purchasing, and onboarding the solution.

- Explain the results. Demonstrate the impact of the solution they chose by backing up their positive experience with data. Fill in with customer quotes and tangible, measurable results that show the effect of their choice.

- Ask for action. Include a CTA at the end of the case study that invites readers to reach out for more information, try a demo, or learn more — to nurture them further in the marketing pipeline. What you ask of the reader should tie directly into the goals that were established for the case study in the first place.

Template 2 — Data-driven format

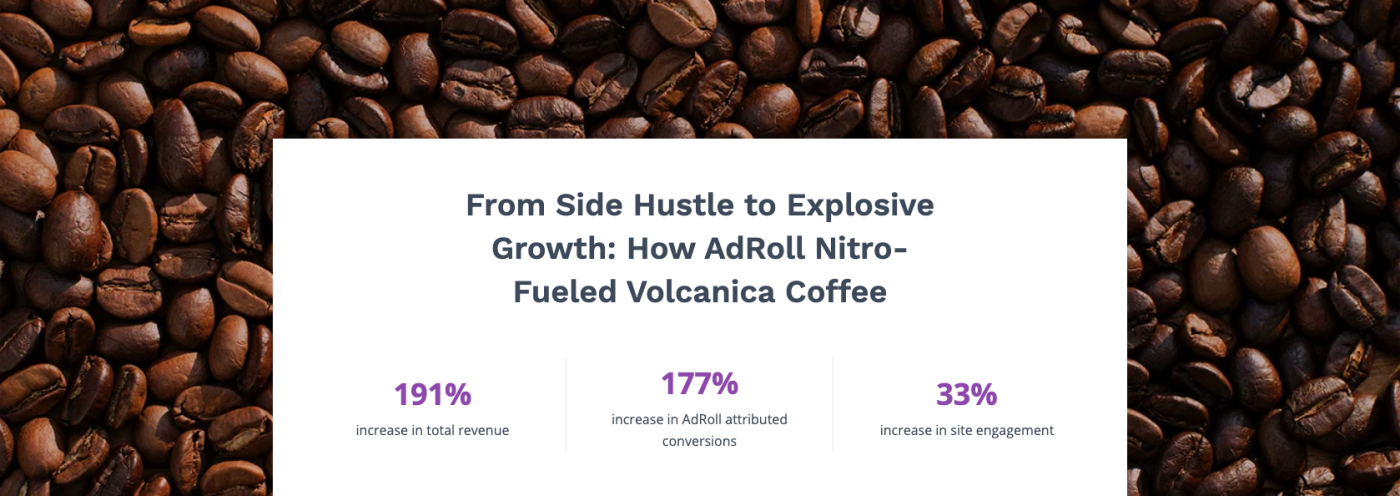

- Start with an engaging title. Be sure to include a statistic or data point in the first 70 characters. Again, it’s best to include the customer’s name as part of the title.

- Create an overview. Share the customer’s background and a short version of the challenge they faced. Present the reason a particular product or service was chosen, and feel free to include quotes from the customer about their selection process.

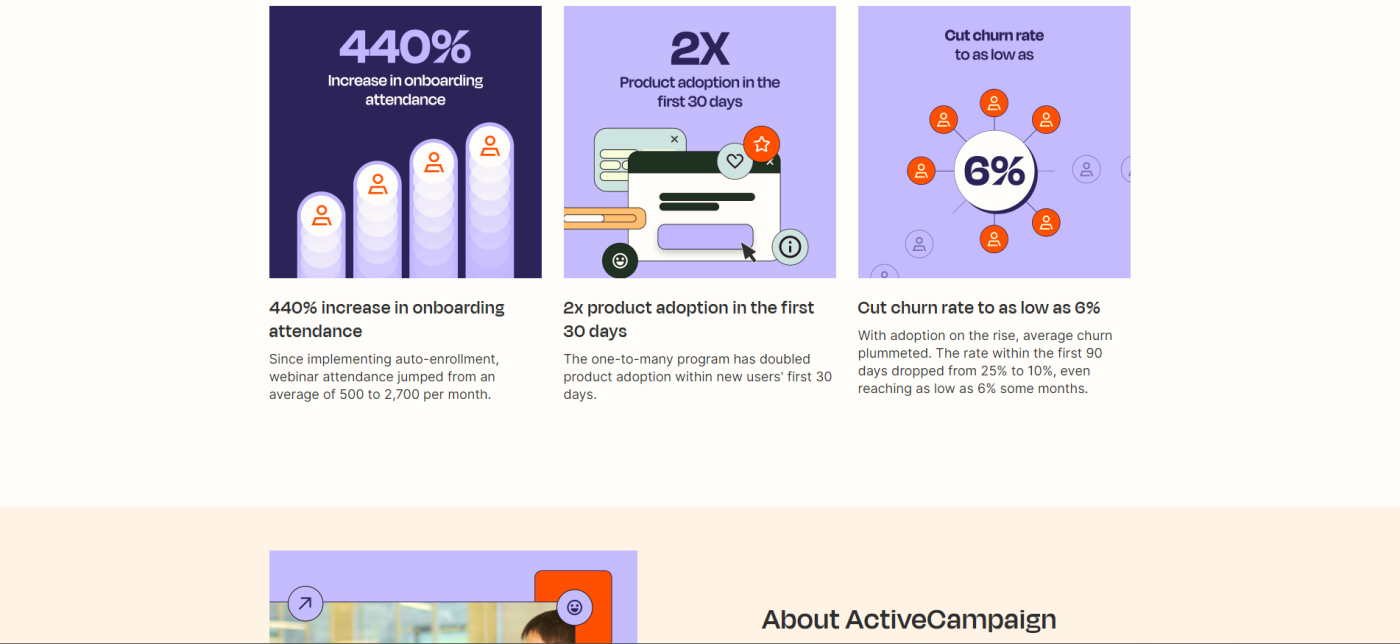

- Present data point 1. Isolate the first metric that the customer used to define success and explain how the product or solution helped to achieve this goal. Provide data points and quotes to substantiate the claim that success was achieved.

- Present data point 2. Isolate the second metric that the customer used to define success and explain what the product or solution did to achieve this goal. Provide data points and quotes to substantiate the claim that success was achieved.

- Present data point 3. Isolate the final metric that the customer used to define success and explain what the product or solution did to achieve this goal. Provide data points and quotes to substantiate the claim that success was achieved.

- Summarize the results. Reiterate the fact that the customer was able to achieve success thanks to a specific product or service. Include quotes and statements that reflect customer satisfaction and suggest they plan to continue using the solution.

- Ask for action. Include a CTA at the end of the case study that asks readers to reach out for more information, try a demo, or learn more — to further nurture them in the marketing pipeline. Again, remember that this is where marketers can look to convert their content into action with the customer.

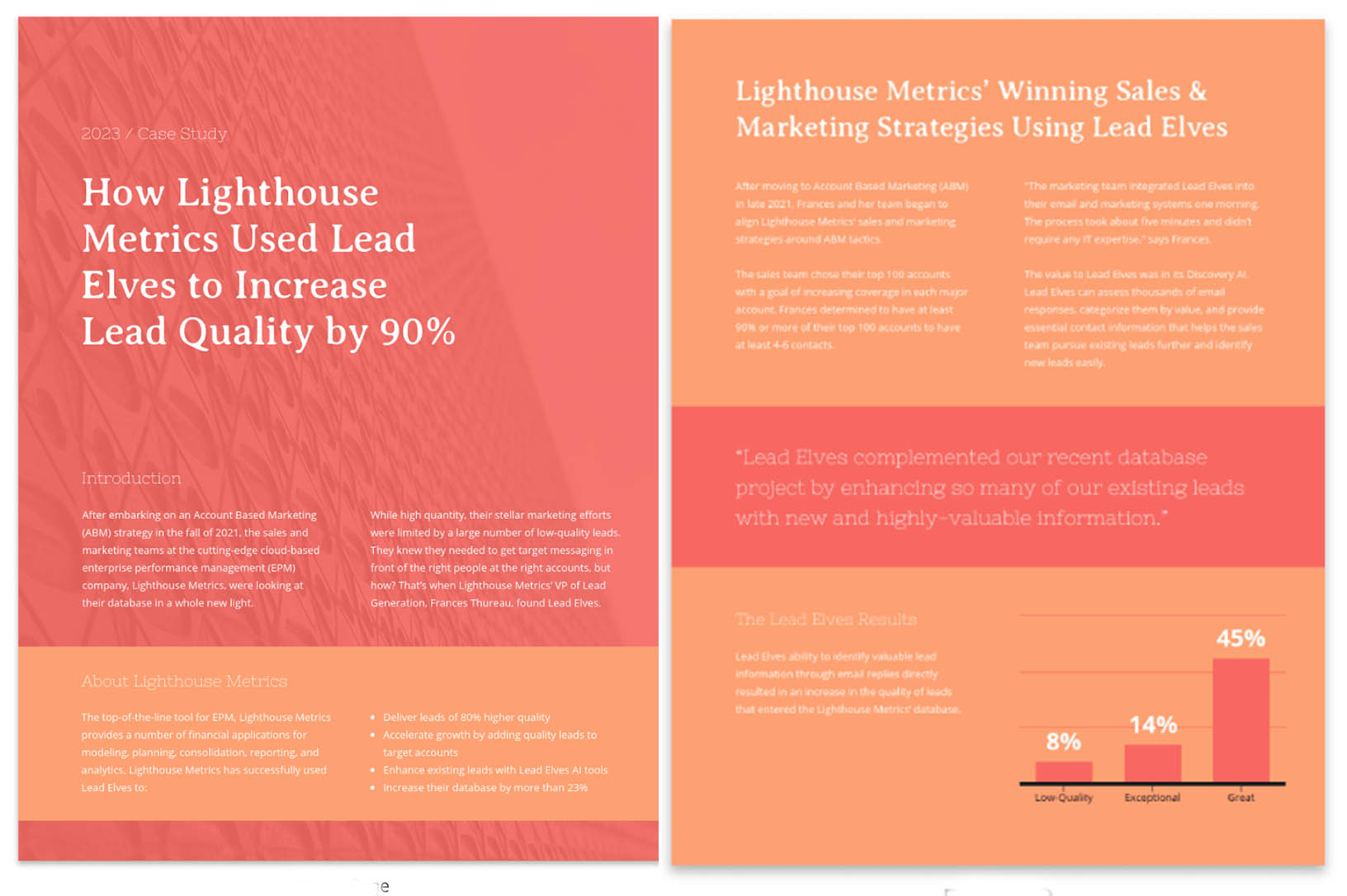

While templates are helpful, seeing a case study in action can also be a great way to learn. Here are some examples of how Adobe customers have experienced success.

Juniper Networks

One example is the Adobe and Juniper Networks case study , which puts the reader in the customer’s shoes. The beginning of the story quickly orients the reader so that they know exactly who the article is about and what they were trying to achieve. Solutions are outlined in a way that shows Adobe Experience Manager is the best choice and a natural fit for the customer. Along the way, quotes from the client are incorporated to help add validity to the statements. The results in the case study are conveyed with clear evidence of scale and volume using tangible data.

The story of Lenovo’s journey with Adobe is one that spans years of planning, implementation, and rollout. The Lenovo case study does a great job of consolidating all of this into a relatable journey that other enterprise organizations can see themselves taking, despite the project size. This case study also features descriptive headers and compelling visual elements that engage the reader and strengthen the content.

Tata Consulting

When it comes to using data to show customer results, this case study does an excellent job of conveying details and numbers in an easy-to-digest manner. Bullet points at the start break up the content while also helping the reader understand exactly what the case study will be about. Tata Consulting used Adobe to deliver elevated, engaging content experiences for a large telecommunications client of its own — an objective that’s relatable for a lot of companies.

Case studies are a vital tool for any marketing team as they enable you to demonstrate the value of your company’s products and services to others. They help marketers do their job and add credibility to a brand trying to promote its solutions by using the experiences and stories of real customers.

When you’re ready to get started with a case study:

- Think about a few goals you’d like to accomplish with your content.

- Make a list of successful clients that would be strong candidates for a case study.

- Reach out to the client to get their approval and conduct an interview.

- Gather the data to present an engaging and effective customer story.

Adobe can help

There are several Adobe products that can help you craft compelling case studies. Adobe Experience Platform helps you collect data and deliver great customer experiences across every channel. Once you’ve created your case studies, Experience Platform will help you deliver the right information to the right customer at the right time for maximum impact.

To learn more, watch the Adobe Experience Platform story .

Keep in mind that the best case studies are backed by data. That’s where Adobe Real-Time Customer Data Platform and Adobe Analytics come into play. With Real-Time CDP, you can gather the data you need to build a great case study and target specific customers to deliver the content to the right audience at the perfect moment.

Watch the Real-Time CDP overview video to learn more.

Finally, Adobe Analytics turns real-time data into real-time insights. It helps your business collect and synthesize data from multiple platforms to make more informed decisions and create the best case study possible.

Request a demo to learn more about Adobe Analytics.

https://business.adobe.com/blog/perspectives/b2b-ecommerce-10-case-studies-inspire-you

https://business.adobe.com/blog/basics/business-case

https://business.adobe.com/blog/basics/what-is-real-time-analytics

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is a Case Study?

Weighing the pros and cons of this method of research

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Cara Lustik is a fact-checker and copywriter.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Cara-Lustik-1000-77abe13cf6c14a34a58c2a0ffb7297da.jpg)

Verywell / Colleen Tighe

- Pros and Cons

What Types of Case Studies Are Out There?

Where do you find data for a case study, how do i write a psychology case study.

A case study is an in-depth study of one person, group, or event. In a case study, nearly every aspect of the subject's life and history is analyzed to seek patterns and causes of behavior. Case studies can be used in many different fields, including psychology, medicine, education, anthropology, political science, and social work.

The point of a case study is to learn as much as possible about an individual or group so that the information can be generalized to many others. Unfortunately, case studies tend to be highly subjective, and it is sometimes difficult to generalize results to a larger population.

While case studies focus on a single individual or group, they follow a format similar to other types of psychology writing. If you are writing a case study, we got you—here are some rules of APA format to reference.

At a Glance

A case study, or an in-depth study of a person, group, or event, can be a useful research tool when used wisely. In many cases, case studies are best used in situations where it would be difficult or impossible for you to conduct an experiment. They are helpful for looking at unique situations and allow researchers to gather a lot of˜ information about a specific individual or group of people. However, it's important to be cautious of any bias we draw from them as they are highly subjective.

What Are the Benefits and Limitations of Case Studies?

A case study can have its strengths and weaknesses. Researchers must consider these pros and cons before deciding if this type of study is appropriate for their needs.

One of the greatest advantages of a case study is that it allows researchers to investigate things that are often difficult or impossible to replicate in a lab. Some other benefits of a case study:

- Allows researchers to capture information on the 'how,' 'what,' and 'why,' of something that's implemented

- Gives researchers the chance to collect information on why one strategy might be chosen over another

- Permits researchers to develop hypotheses that can be explored in experimental research

On the other hand, a case study can have some drawbacks:

- It cannot necessarily be generalized to the larger population

- Cannot demonstrate cause and effect

- It may not be scientifically rigorous

- It can lead to bias

Researchers may choose to perform a case study if they want to explore a unique or recently discovered phenomenon. Through their insights, researchers develop additional ideas and study questions that might be explored in future studies.

It's important to remember that the insights from case studies cannot be used to determine cause-and-effect relationships between variables. However, case studies may be used to develop hypotheses that can then be addressed in experimental research.

Case Study Examples

There have been a number of notable case studies in the history of psychology. Much of Freud's work and theories were developed through individual case studies. Some great examples of case studies in psychology include:

- Anna O : Anna O. was a pseudonym of a woman named Bertha Pappenheim, a patient of a physician named Josef Breuer. While she was never a patient of Freud's, Freud and Breuer discussed her case extensively. The woman was experiencing symptoms of a condition that was then known as hysteria and found that talking about her problems helped relieve her symptoms. Her case played an important part in the development of talk therapy as an approach to mental health treatment.

- Phineas Gage : Phineas Gage was a railroad employee who experienced a terrible accident in which an explosion sent a metal rod through his skull, damaging important portions of his brain. Gage recovered from his accident but was left with serious changes in both personality and behavior.

- Genie : Genie was a young girl subjected to horrific abuse and isolation. The case study of Genie allowed researchers to study whether language learning was possible, even after missing critical periods for language development. Her case also served as an example of how scientific research may interfere with treatment and lead to further abuse of vulnerable individuals.

Such cases demonstrate how case research can be used to study things that researchers could not replicate in experimental settings. In Genie's case, her horrific abuse denied her the opportunity to learn a language at critical points in her development.

This is clearly not something researchers could ethically replicate, but conducting a case study on Genie allowed researchers to study phenomena that are otherwise impossible to reproduce.

There are a few different types of case studies that psychologists and other researchers might use:

- Collective case studies : These involve studying a group of individuals. Researchers might study a group of people in a certain setting or look at an entire community. For example, psychologists might explore how access to resources in a community has affected the collective mental well-being of those who live there.

- Descriptive case studies : These involve starting with a descriptive theory. The subjects are then observed, and the information gathered is compared to the pre-existing theory.

- Explanatory case studies : These are often used to do causal investigations. In other words, researchers are interested in looking at factors that may have caused certain things to occur.

- Exploratory case studies : These are sometimes used as a prelude to further, more in-depth research. This allows researchers to gather more information before developing their research questions and hypotheses .

- Instrumental case studies : These occur when the individual or group allows researchers to understand more than what is initially obvious to observers.

- Intrinsic case studies : This type of case study is when the researcher has a personal interest in the case. Jean Piaget's observations of his own children are good examples of how an intrinsic case study can contribute to the development of a psychological theory.

The three main case study types often used are intrinsic, instrumental, and collective. Intrinsic case studies are useful for learning about unique cases. Instrumental case studies help look at an individual to learn more about a broader issue. A collective case study can be useful for looking at several cases simultaneously.

The type of case study that psychology researchers use depends on the unique characteristics of the situation and the case itself.

There are a number of different sources and methods that researchers can use to gather information about an individual or group. Six major sources that have been identified by researchers are:

- Archival records : Census records, survey records, and name lists are examples of archival records.

- Direct observation : This strategy involves observing the subject, often in a natural setting . While an individual observer is sometimes used, it is more common to utilize a group of observers.

- Documents : Letters, newspaper articles, administrative records, etc., are the types of documents often used as sources.

- Interviews : Interviews are one of the most important methods for gathering information in case studies. An interview can involve structured survey questions or more open-ended questions.

- Participant observation : When the researcher serves as a participant in events and observes the actions and outcomes, it is called participant observation.

- Physical artifacts : Tools, objects, instruments, and other artifacts are often observed during a direct observation of the subject.

If you have been directed to write a case study for a psychology course, be sure to check with your instructor for any specific guidelines you need to follow. If you are writing your case study for a professional publication, check with the publisher for their specific guidelines for submitting a case study.

Here is a general outline of what should be included in a case study.

Section 1: A Case History

This section will have the following structure and content:

Background information : The first section of your paper will present your client's background. Include factors such as age, gender, work, health status, family mental health history, family and social relationships, drug and alcohol history, life difficulties, goals, and coping skills and weaknesses.

Description of the presenting problem : In the next section of your case study, you will describe the problem or symptoms that the client presented with.

Describe any physical, emotional, or sensory symptoms reported by the client. Thoughts, feelings, and perceptions related to the symptoms should also be noted. Any screening or diagnostic assessments that are used should also be described in detail and all scores reported.

Your diagnosis : Provide your diagnosis and give the appropriate Diagnostic and Statistical Manual code. Explain how you reached your diagnosis, how the client's symptoms fit the diagnostic criteria for the disorder(s), or any possible difficulties in reaching a diagnosis.

Section 2: Treatment Plan

This portion of the paper will address the chosen treatment for the condition. This might also include the theoretical basis for the chosen treatment or any other evidence that might exist to support why this approach was chosen.

- Cognitive behavioral approach : Explain how a cognitive behavioral therapist would approach treatment. Offer background information on cognitive behavioral therapy and describe the treatment sessions, client response, and outcome of this type of treatment. Make note of any difficulties or successes encountered by your client during treatment.

- Humanistic approach : Describe a humanistic approach that could be used to treat your client, such as client-centered therapy . Provide information on the type of treatment you chose, the client's reaction to the treatment, and the end result of this approach. Explain why the treatment was successful or unsuccessful.

- Psychoanalytic approach : Describe how a psychoanalytic therapist would view the client's problem. Provide some background on the psychoanalytic approach and cite relevant references. Explain how psychoanalytic therapy would be used to treat the client, how the client would respond to therapy, and the effectiveness of this treatment approach.

- Pharmacological approach : If treatment primarily involves the use of medications, explain which medications were used and why. Provide background on the effectiveness of these medications and how monotherapy may compare with an approach that combines medications with therapy or other treatments.

This section of a case study should also include information about the treatment goals, process, and outcomes.

When you are writing a case study, you should also include a section where you discuss the case study itself, including the strengths and limitiations of the study. You should note how the findings of your case study might support previous research.

In your discussion section, you should also describe some of the implications of your case study. What ideas or findings might require further exploration? How might researchers go about exploring some of these questions in additional studies?

Need More Tips?

Here are a few additional pointers to keep in mind when formatting your case study:

- Never refer to the subject of your case study as "the client." Instead, use their name or a pseudonym.

- Read examples of case studies to gain an idea about the style and format.

- Remember to use APA format when citing references .

Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2011;11:100.

Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2011 Jun 27;11:100. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-11-100

Gagnon, Yves-Chantal. The Case Study as Research Method: A Practical Handbook . Canada, Chicago Review Press Incorporated DBA Independent Pub Group, 2010.

Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods . United States, SAGE Publications, 2017.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Spring Promo 30% OFF Surfer plans & AI bundles until April 24th. Celebrate the release of Auto-Optimize and Internal Linking! 🎉 Grab the discount and take your Content Score from meh to ah-ma-zing in a single click. ✨

30% OFF Surfer plans & AI bundles until April 24th.

Celebrate the release of Auto-Optimize and Internal Linking! Grab the discount and take your Content Score from meh to ah-ma-zing in a single click.

How To Write A Case Study [Template plus 20+ Examples]

In an era where every niche seems completely saturated, learning how to write a case study is one of the most important time investments you can make in your business.

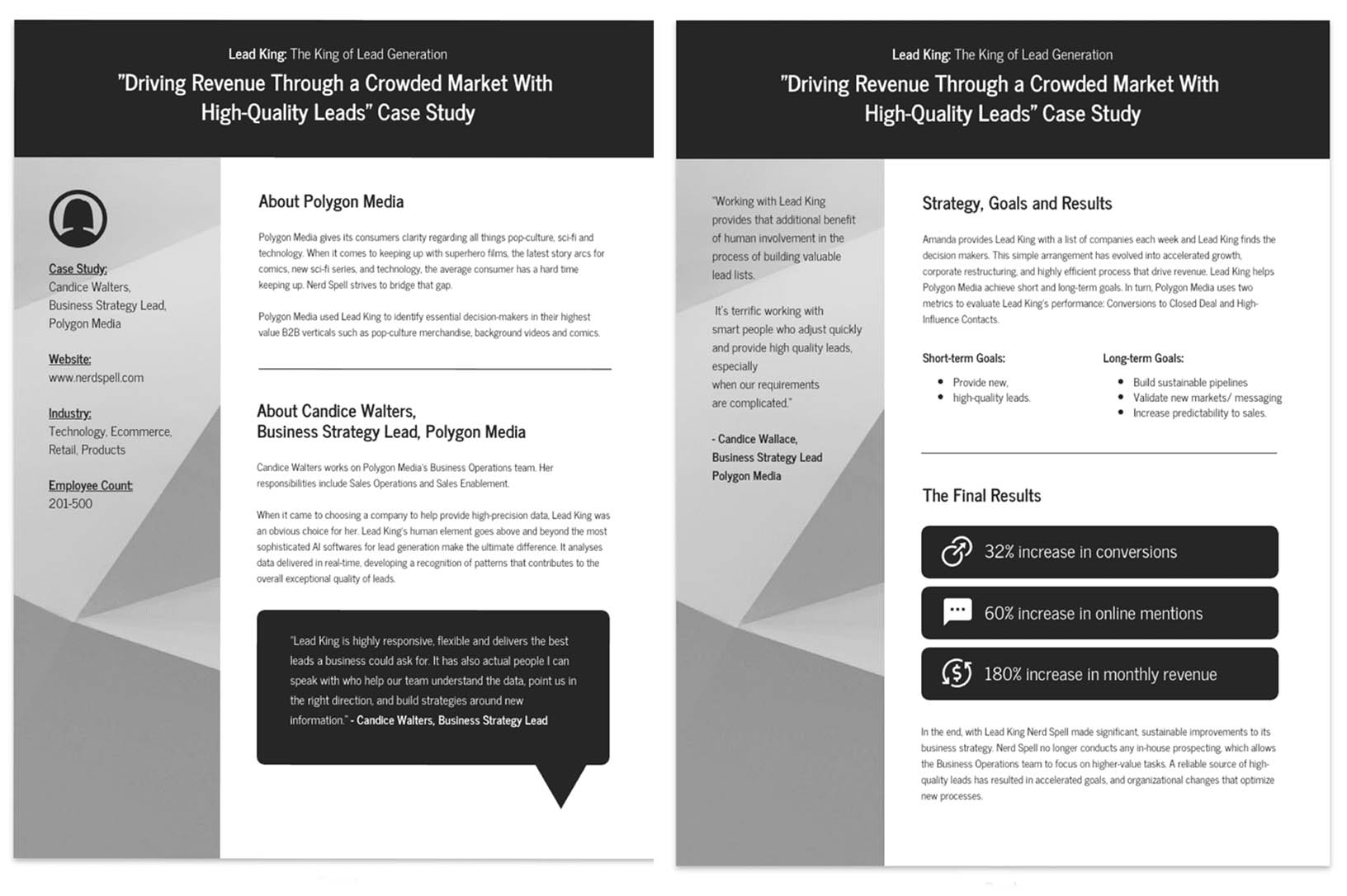

That’s because case studies help you present a compelling story of success to bottom-of–funnel decision makers. Do it right, and a solid case study can greatly increase your chances of closing new deals.

A 2023 study from the Content Marketing Institute found that 36% of B2B marketers consider case studies to be effective tools for converting prospects into customers.

In this article, I’ll show you step-by-step exactly how to write a case study that makes an impact. Along the way, I’ll highlight several stellar case studies that illustrate how to do it right.

What you will learn

- What a case study is and what it's not.

- How an effective case study can help establish you as an expert and land more clients.

- How to choose the right topic for your case study, taking into account client successes and broad appeal in your customer's industry.

- The essential parts of a good case study and how to write each one.

- Style and formatting points that will make your case study stand out for readers to understand.

- 4 tips for conducting an effective client interview.

- 6 real-life case studies that you can use as examples for creating your own customer stories.

What is a case study?

A case study is a detailed story about how your products or services helped a client overcome a challenge or meet a goal. Its main purpose is to prove to potential customers that you understand their problems and have the experience and expertise to help solve them.

But, even though a case study can help you attract and win customers, it's not just an advertisement for your offerings.

In truth, your company shouldn’t even be the main focus of a good case study.

Instead, a winning case study follows a successful business transformation from beginning to end and shows how you made it all possible for your client.

An example of a case study that conveys a strong customer story is the deep dive we did into how ClickUp used SurferSEO to boost their blog traffic by 85% in a year.

Why you should write a case study

The most obvious reason why you should write a case study is that it's a great way to show potential customers how others in their position have benefited from your product or service.

Here are a few of the key benefits of writing a case study, all of which can help you turn readers into customers.

Demonstrates expertise

A well-written case study shows clearly how your company solved a complex problem or helped a particular customer make improvements using your solution.

This is the sort of expertise other potential clients will look for when they run into the same sort of issues.

For instance, one of CrowdStrike's case studies shows how they helped Vijilan scale its logging capacity so they could stop turning away business.

This positions CrowdStrike as experts in helping deal with log management issues.

Other companies dealing with their own logging problems will definitely find this to be a compelling story. And you can bet CrowdStrike will be on their short list of potential solution providers after reading this case study.

Educates potential customers

You might have the best product on the market, but it won't do you any good if potential clients don't understand how it might help them.

A case study breaks down those barriers by showing real-life examples of your product in action, helping other customers solve their problems.

A good example is the Trello case study library .

Each story gives detailed examples showing how the customer uses Trello and includes actual screenshots from their workflows.

Here is an interesting snapshot from the BurgerFi example.

Here, you get a glimpse of a live Trello board that BurgerFi uses to manage their marketing assets.

By showing how existing clients use your product, you make it a lot easier for future customers to imagine how it might work for their needs, too.

Generates leads

A strong case study is a valuable piece of content that provides insights and can help companies make decisions.

Many of them would be happy to give you their contact information in exchange for the chance to read about potential solutions to their problems.

That combination of valuable content and a hungry market makes case studies great tools for lead generation.

You can either gate part of your case study and leave the rest of it public, or require an email address and other contact information in order to download the full study.

That's the approach Pulsara took in detailing how their telehealth communication platform helped EvergreenHealth improve efficiency:

The names and addresses you collect with this approach will be about as warm as you could ever hope for since they probably have the same sort of problems you solved in your case study.

Along the same lines, case studies can be extremely effective in upselling or cross-selling other products to the decision-makers who read them.

And they are great tools for persuading a client to make a purchase with you.

Indeed, a great case study can often be the "final straw" that lands you a client considering your services.

A 2023 survey by Uplift Content , for example, found that 39% of SaaS marketers ranked case studies as being very effective for increasing sales.

That made it their #1 tactic for the second year in a row.

Builds trust

Potential clients want to know that they can trust you to handle their business with care and to deliver on your promises.

A case study is the perfect vehicle to show that you can do just that.

Take advantage of that opportunity to present statistics, client testimonials, graphics, and any other proof that you can get results.

For example, in their case study about helping a law firm uncover critical data for a tricky case, Kroll shows us just how much they were able to cut through the noise:

Any law firm staring at its own pile of documents to search through would love to have that haystack reduced by a factor of 32.5x, too.

And Sodexo makes good use of customer testimonials in their case studies, like this quote from the procurement lead for a Montana mining company.

Having existing customers tell the world that they count on you is powerful free advertising and builds trust with your readers. That can help transform them into customers down the road.

Provides social proof

You can also use your case study to show that your product or service works in a specific industry.

Real-world examples of customer success stories position you as someone their peers and competitors can turn to, too.

For instance, Stericycle details how they helped seven children's hospitals get a handle on their "sharps" management:

They also include glowing quotes from hospital leaders in the same study.

Other hospitals looking for help in disposing of their hazardous waste will know right away after reading this study that Stericycle understands their needs.

This is the type of social proof that can really help establish you as a go-to solution for the industries you serve.

How to choose a subject for your case study

In order to get the most bang for your buck from your case study, you need to make sure you pick a topic that resonates with your target audience. And one that can make your solution look its best.

Below are 4 ways to select the best subject for your case study.

1. Choose a popular topic

Make sure the topic you tackle in your case study is one that most of your potential clients are searching for.

You may be tempted to highlight an unusual project that you find especially interesting. But that usually won't have the same sort of selling power as a topic with more broad appeal.

For instance, Aruba Networks has helped colleges and universities with all sorts of networking projects. Some of those involve really fascinating edge cases like research labs, esports arenas, and other innovative solutions.

But what most schools are looking for in a network upgrade is improving connectivity across campus while enhancing security and saving money.

Those are exactly the outcomes Aruba focuses on in its Doane University case study .

Remember that your case study is likely to be read by decision-makers at the bottom of the sales funnel who are ready to buy.

Your content needs to resonate with them and address the questions they want answered in order to make their decision.

Aruba tackles their customers' concerns head-on throughout the Doane study, as you can see from their section headings:

- "Realizing a hyper-connected vision"

- "10X throughput eliminates academic barriers"

- "More secure with less effort"

- "Greener and more resilient at better insurance rates"

College administrators can see at a glance that Aruba understands their needs and has helped other institutions with similar problems.

2. Consider relevance and attractiveness

Although you want to choose a popular subject for your case study (as discussed above), it's also important to make sure it's relevant to your target audience.

For instance, if you provide design services, a one-off project you did to help a local company set up its website might have taught you a lot. But most of your potential readers will be much more interested in reading about how your designs helped that client improve brand perception.

It’s also best to choose a situation where your product or service is used in a way that you expect most potential users to adopt.

For example, Allegion's Mount Holyoke case study (PDF) details how one campus used their products to move to contactless and mobile entry systems.

Students today demand more control over their physical security than ever before. And the administrative overhead of managing thousands of doors and physical keys on a college campus is enormous.

As a result, most schools are interested in using technology to enable their students and reduce staffing costs.

Allegion hits those points dead-on with this case study.

An added benefit of choosing a topic with broad appeal among your target client base is that you can use the content in your normal distribution channels.

For example, you can publish all or part of it as a blog post, include it in your newsletter, or use it as the basis for a YouTube video. Wherever your audience is, that's probably a good place to promote your case study.

3. Identify a 5 star use case

A case study is like a sales executive for your company.

It needs to show your product or service in the best possible light and highlight its features and benefits while distinguishing it from other products.

Choose a client example that really makes your solution look like a superstar and showcases its most outstanding attributes.

You should also avoid showing your product or service being used in a novel or completely innovative way. While that can provide some solid insight, you risk alienating your typical client who needs to know that you can solve their specific problem.

Instead, your case study should demonstrate how your solution took on a common industry problem and delivered stellar results.

A great example is Beckman Coulter's case study that details their work with Alverno Labs.

The objective was to reduce the time it took Alverno to deliver lab test results while reducing operating costs, which are common goals for many testing labs.

The case study presents a detailed description of how Beckman Coulter implemented a continuous improvement process for Alverno. They enhance the discussion with several meaty visuals like this project roadmap:

They also include plenty of tangible data to prove their success.

And of course, include direct client testimonials:

From top to bottom, this case study proves that Beckman Coulter understands their customers business needs and can offer top-notch solutions.

4. Find a satisfied customer

You're going to need input from your client in order to build the most complete and accurate case study that you can.

So when you're trying to choose a customer story to use, look for a client who is happy to share their positive experience working with you.

Try to find one who seems genuinely eager to talk so that they will be timely with their responses to your questions.

If you have a customer who is willing to sit down for an actual interview with you, they're a great candidate. You'll get answers quickly, and the client is obviously comfortable enough with your relationship to talk with you directly.

A good example that focuses on a satisfied client comes from Aerofloat, an Australian wastewater treatment company.

In their Norco Food Case Study , Aerofloat reports that Norco hired them for additional projects as a result of their successful prior engagement:

It's always good to show prospective clients that your existing customers stick with you.

So try to pick a case study done in collaboration with a current client, not one from the past.

Aerofloat also highlights their ongoing relationship with Norco by also including them in the customer list on their About page:

How to write a case study

Now that we’ve covered the benefits of writing a case study and figured out how to pick the best topic for your situation, it’s time to get down to the business of writing.

Below is a rundown of the sections that make up the structure of a typical case study. For each piece, I’ll show you what types of content you should include and give you an example of a study that does it right.

Here are 8 tips to writing a case study.

1. Attention grabbing title

The title of your case study needs to grab potential readers attention and convince them that this is a valuable piece of content.

Make your title catchy, concise, and descriptive, just like you would for a good blog post. But you also need to make sure you give your readers a clear idea of what the case study is about.

Offer them at least a hint of the type of results you were able to deliver, too.

It’s a good idea to use numbers here – the higher, the better. It's especially effective if you can show how quickly you got results and how much money your client saved or made as a result of working with you.

Our ClickUp case study that I mentioned earlier is a good example. The full title is

SurferSEO Helps ClickUp Publish 150+ Articles And Achieve Blog Traffic Growth of 85% in 12 Months.

Here are some other case studies that make effective use of numbers in their titles:

- Healthcare Administrative Partners Increases Online Patient Payments by 20% in Two Months

- Case Study: Taylor Kotwa, Sprinter, Increases FTP 7% in 4 months

- Case Study: Lakeview Farms Reduced Downtime by 36% in 6 Months

- CASELY case study: Improved first response time by 10x while experiencing 16,954% growth

This type of headline gives potential clients a sense that you will work with urgency to improve their bottom-line results.

2. Hook readers in your introduction

The introduction of your case study should set the stage for the comprehensive narrative that follows.

Give a brief description of the problem for context and quickly introduce the customer's story. Touch on the results you helped them achieve, but don't go overboard on details.

Overall, the introduction should give your reader just enough information to keep them engaged and ready to move into the heart of the case study.

It should also establish that they're in the right place and that you are the right person to be telling this story.

This case study about the cybersecurity program at Investors Bank includes a solid example of an effective introduction:

3. Highlight the challenge

This section should clearly outline the problem or challenge that your customer is facing.

Help your readers understand why a solution was necessary, and why that specific pain point was bothering the client.

And, since this is the entire motivation for the project in the first place, don't skimp on details.

For instance, one of Verkada's case studies explains why maintaining security cameras is a huge challenge for Crystal Mountain Resort in Washington state. They start off with a direct quote from the resort's IT director:

The elevation tops out at a little over 7,000 feet, so the weather conditions can get extreme. We needed durable cameras capable of handling everything from snowstorms to 100 MPH winds.

That makes it crystal clear what sort of problem Crystal Mountain was facing.

The case study then adds more detail with separate subsections about hardware durability, image quality, and cumbersome footage retrieval.

By the time they finish reading this section, your readers should have no doubt about what the problem is and why a solution is needed.

4. Solve their problem

The solution section is one of the most important parts of a case study.

This is your chance to describe how your product or service provided a solution to the problem or challenge your client was having.

It's where you can really start to make a connection with potential new clients by showing them that you understand the issue at hand.

First, provide some details about how you analyzed the situation. The Kroll case study on handling critical legal data mentioned earlier does a great job of this with bullet points describing their research process.

This type of analysis helps build confidence that you take a thorough approach to your engagements and are looking out for your clients best interests.

Now you can move on to describe the solution you and your client chose based on your investigation.

In their legal case study, Kroll determined that the best solution involved digitizing thousands of paper documents and using AI to analyze more than a million documents.

Kroll describes in detail how they used their RelativityOne system to achieve those goals:

This level of detail helps prospective customers better understand the root cause of their problems and positions you as the right company to solve them.

5. Showcase your results

The results section is all about proving that you can actually deliver on the promise of your proposed solution. Go heavy on the details here, too, and make sure your readers understand the results you achieved.

Wherever possible, use specific numbers and data points to show exactly how effective your solution was for your client.

A good example is this BetterBricks case study showing how they helped an aerospace company slash energy costs.

They distilled their bottom line results into a simple table:

The text of the study then goes into more detail about what these numbers mean, but this quick graphic lets readers know right away the scope of the results achieved.

Here is a sampling of BetterBrick’s more detailed explanation of their results in this case:

This is your place to really crow about the success you achieved with your client, so make it as obvious as possible just how impactful you were.

6. Use multimedia well

One way to make a lasting impression on potential clients is to include relevant visuals throughout your case study.

Graphs, screenshots, and product photos help break up the text and make your study more engaging overall.

But they can also add details to your story and make a memorable visual impact beyond what mere words can accomplish.

We got a taste of that with the table of results in the BetterBricks example above, but that's just the start.

Inrix is a good example of a company that loads up its case studies with insightful and engaging media to tell a better story.

For instance, in their breakdown of a collaboration with the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (DOT), Inrix uses charts, tables, and graphs throughout.

One innovative example is this diagram about crash distances:

This really brings the idea to life in a way that words alone can't, and it's likely to stick with readers long after they've clicked off the case study.

Other types of media that companies use to good effect in their case studies include pictures of key client stakeholders, interactive charts, tables, and simple graphs.

You can see in this high-level overview that Inrix includes most of these in their Pennsylvania DOT case study:

You can even use video to demonstrate your solution or to share a client testimonial.

If possible, include direct quotes from your client to add authenticity to the case study.

This will show potential customers that you and your existing client have a good relationship and that they value your work.

It’s pretty compelling stuff to have a ringing endorsement like this one from an EnergyCAP case study , to show your readers:

You can place customer quotes throughout the case study to highlight important points, and you should definitely try to include at least one that shows overall customer satisfaction.

Chances are you have some of these quotes already in the form of testimonials or as part of the customer interview you conducted in preparing for your case study (more on that later).

You can use those quotes here if they fit the context of your case study.

That will save time and red tape for both you and your client since they'll be reviewing your final case study before it goes live anyway.

8. Conclusion

The conclusion should summarize the key points of the case study and reinforce the success of the solution. It could also include a call to action, encouraging readers to try your product or service or to get in touch for more information.

You might also include information about future plans with the client to reinforce the idea that your relationship is strong and ongoing.

That's the approach that Gravitate Design used in their case study about helping GoBeyond with their bounce rates and time on page:

Like the introduction, the conclusion section of a case study should be short and sweet, giving just enough detail to make the reader want to hear more from you.

Checklist for case studies

Beyond the story that you want to tell in your case study, you also need to pay attention to several other factors. Indeed, the layout and format of your study can have a big impact on how effective it is at keeping your readers engaged and delivering your message.

Here is a quick checklist for creating case studies.

Break up the text with headings and subheadings

Big blocks of text can be intimidating and make it tough for your audience to stay on track.

In contrast, a case study with clear headings and subheadings throughout breaks up the story and gives readers visual clues about what's coming.

This also makes the case study easier for readers to scan and helps you keep each section focused on a single idea.

Use bullet points for lists or key points

Along the same lines, bullet points let you present important information in small bits that are easy for readers to digest.

Some of the best uses of bullet points include:

- A series of facts or tips

- A list of product features or benefits

- A quick summary of results

- Steps in a how-to procedure

- A rundown of multiple statistics

For these bite-sized hunks of detail, bullets often make for a much cleaner and readable list than jamming all the information into a single paragraph.

Bullet point lists also make great quick references for readers to come back to later.

Highlight key points with bold or italic text

Bold and italic text draws the reader’s eyes to the words you highlight, which lets you really drive home key ideas in your case study.

You can use this technique to introduce new terms, place emphasis on a sentence, and showcase important parts of your approach or results.

Like bullet points, bold and italic text also give readers a visual anchor for reference as they’re working through your document.

Make paragraphs short and to-the-point

Aim for 3-4 sentences per paragraph to keep the text readable and engaging. Each paragraph should focus on one main idea to support the subject of the section it’s in.

Using short paragraphs tells readers at a glance that there are break points throughout your case study and helps keep them engaged.

Keep consistent length across the case study

Throughout all parts of your case study, try to cover your main points in detail without overwhelming the reader.

Your potential clients are there to find a possible solution to their problems, not to read a novel.

Give them an inviting document structure and then lead them through each section with clear explanations and no fluff.

Adjust the length based on the complexity of the subject

The flip side of the tip above about keeping your case study tight and focused is that you need to make sure you cover your topic in detail.

Very complex topics will require more explanation and longer overall case studies than simpler subjects.

For example, a case study about paving a church parking lot might be pretty short.

But a story about implementing a comprehensive information security program for a state government will likely be much longer and more detailed.

Include a summary with some takeaways

At the end of your case study, summarize the key takeaways and results to reinforce the message you’re trying to get across.

Briefly recap the problem your client was facing, the solution you came up with, and the results you achieved. Think of this as an executive summary that gives business leaders the TL;DR version of your customer’s success story.

Content Snare includes an eye-catching summary in the case study detailing their efforts to grow their email list:

The overall goal is to leave potential clients with a good last impression and invite them to contact you with questions.

Use visuals to break up text and illustrate points

As we saw in the "How to write a case study" section above, graphs, charts, or images can make your case study more engaging and help illustrate key ideas or results. They also add visual variety and help break up the monotony of text-heavy studies.

Use these types of visuals to help keep your readers interested and make your story more complete.

Below is a high-level view of a portion of Advanced HPC’s Philips case study , which does a great job of incorporating the points in this section. It pulls together all the visual elements to create a very appealing reader experience.

4 tips to create an effective case study

You’re going to need your customer’s input in order to craft the most effective case study possible. It’s their story, after all, and they’re the ones who know what it was like to work with you throughout the process.

They also hold key details that you probably don’t know.

So, once you have their permission to write about the project, you’ll need to talk to them about the specifics. But you also want to respect their time.

Here are 4 tips on how to conduct an interview for your case study.

Prepare questions in advance

Know what information you need and prepare questions to pull that information from your client.

Doing this in advance will help you formulate the questions and sequence them properly to avoid bias and wasting time.

Have a few follow-up or emergency questions ready, too, in case you run into a dead end.

Record the interview

With your client’s permission, record the interview to ensure accuracy and so you can come back to listen to important points again.

This helps you avoid bothering your clients with follow-up questions and also gives you more freedom to let the interview evolve in a natural conversational manner.

Make the interviewee comfortable

Explain the interview process to your client, why you're asking them to talk, and how the information will be used. Remember that you are the one who “needs” the case study, not them.

So you go the extra mile to ensure that your guest is as comfortable as possible.

That also means being flexible with the format of your interview.

If your client doesn’t have time for calls, offer to trade voice notes. Or give them a shared Google document for trading questions and answers.

And if you do end up conducting a live interview, agree to meet at a time that’s best for them.

No matter how you end up conducting your interview, make it clear that your client will be able to review the final version before you make it live.

Give them veto power over any of the information you put together.

Ask open-ended questions

Even though you’ll start out with a series of questions you need answered, don’t limit yourself to those. Instead, encourage your interviewee to share their story in their own words.

Leave some room to ask open-ended questions and let the conversation evolve naturally.

Here are a few examples of the types of questions for discussion:

- What would you do differently if you were starting this project again?

- What do you think about XYZ emerging technology in relation to your industry's challenges?

- What sorts of other projects do you think Acme's solution might help with?

- How do your company's day-to-day operations and needs from how the relevant theories describe the industry?

Especially if you’re recording the interview, as suggested above, you can go back later and put things in a logical order.

Once you have all of the raw material, then you can curate the information and edit it to come up with your final product.

6 case study examples to follow

Now that you know what makes a great case study and how to write one, let's finish up with a few more top-notch business case study examples.

Each of the case studies below hits many of the points in this article, but they all take a different approach. Use them for inspiration or when you need a little refresher on how to write a case study.

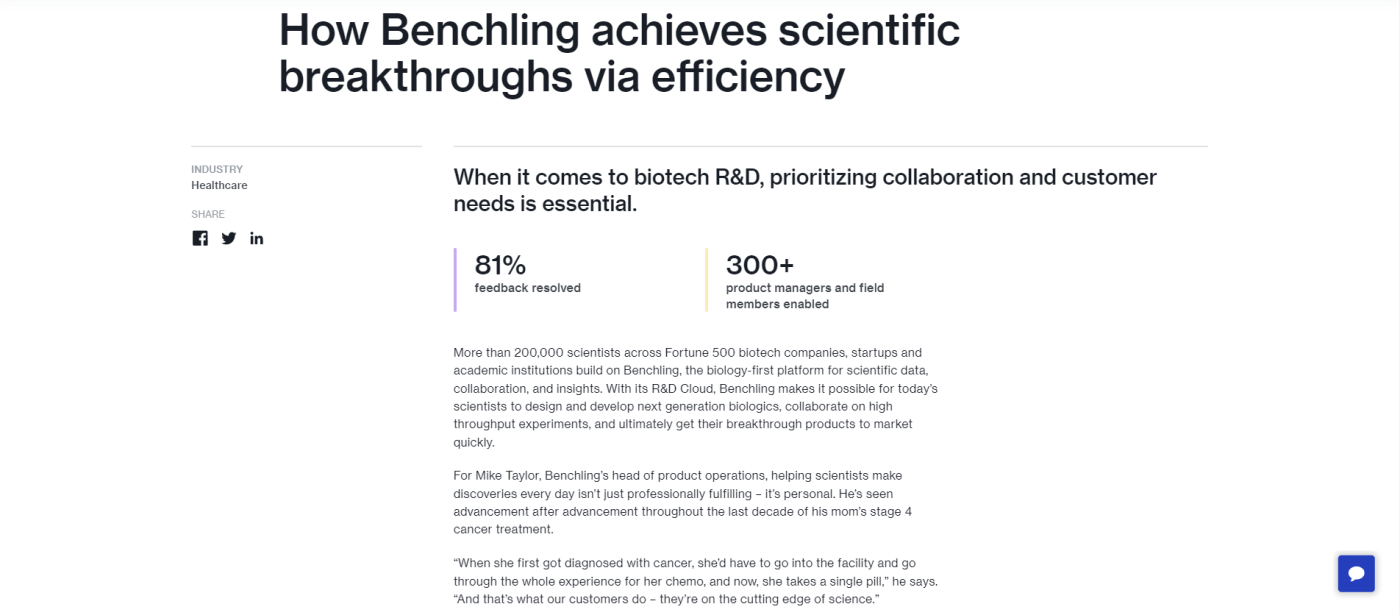

This case study provides a detailed account of how Monograph, a B2B SaaS company, improved its marketing projects and reporting using Databox.

It's a pretty straightforward example of the best practices we've discussed in this article, with an introduction followed by background information on the company (Monograph) and the challenges they faced with manual tracking of each data point.

It describes the solution that Databox helped put in place and then shows clear evidence of the results their customer achieved:

Case studies don't come much more textbook than this one, which makes it a great example to follow.

Growth Design on Airbnb

Growth Design takes a totally unique approach to case studies, each one is an online comic book!

Read through their case study about Airbnb , though, and you'll see that it meets all the criteria for a complete case study even if the setup is a little different than most.

Here is a look at the landing page for this beauty of a study.

The author starts out with a problem: the need to book a place to stay in a foreign country in a hurry. So he heads to Airbnb but ends up overwhelmed by choices and bounces to Google Maps to make his reservation.

He concludes that Airbnb was not the full solution for him in this case and suggests several places they could make improvements.

It's a pretty neat dive into a well-known user experience, and it's also a great lesson in how to use visuals to keep your readers engaged in your case study.

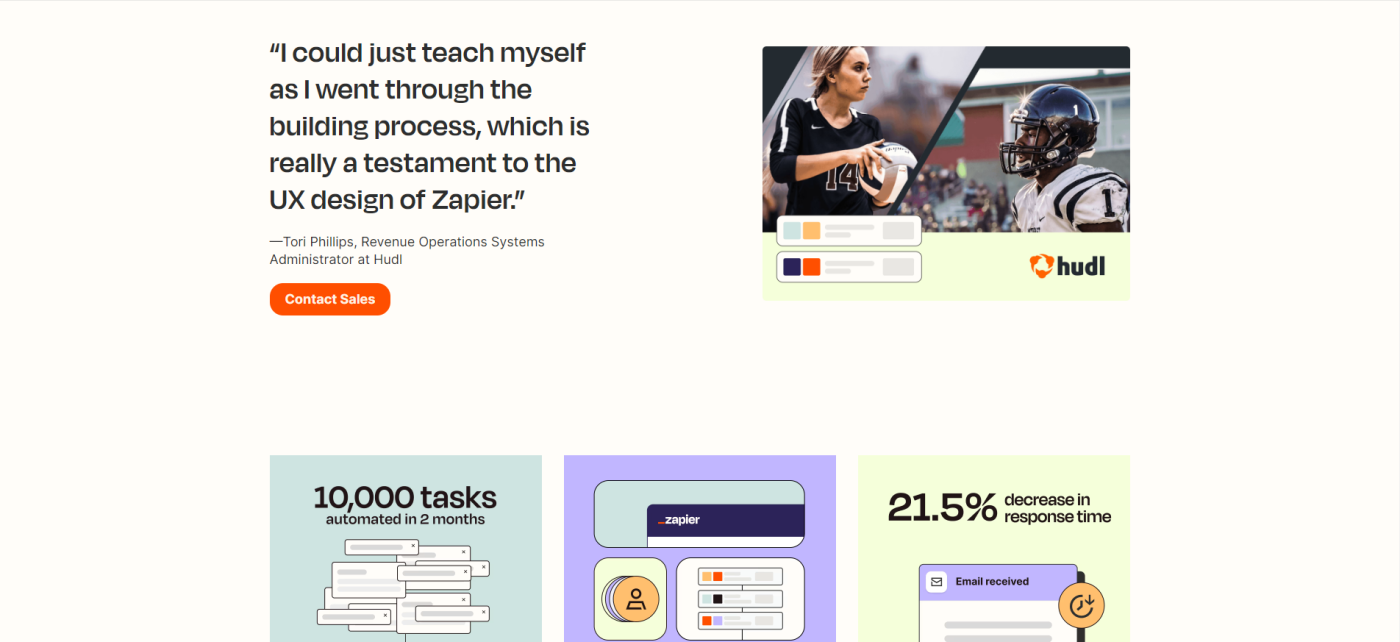

This case study about how Grubhub used Webflow to build a viral marketing campaign hits you with stunning results right off the bat.

From there, the study tells the full story of how they achieved these results. Even though the author doesn't explicitly break out the problem, solution, and results sections, she still takes the reader through that journey.

It's a concise but complete story broken up by a few choice graphics.

This case study dives into how Employment Hero uses Slack to keep their remote employees engaged and productive as the company grows.

It details how Employee Hero continuously reevaluates its app usage to identify possible solutions to issues that arise and how Slack consistently helps meet the challenges.

This case study is a great example of picking a use case that is relevant to most of Slack's user base -- improving communication and productivity among remote employees.

Slack also makes effective use of quotes from the decision makers at Employment Hero.

We already talked about our ClickUp case study a little earlier in this article, but it's worth a deeper look as an example to help guide your writing.

As you would expect, this case study hits main points we've covered here: problem statement, solution, and results.

But there are a couple of "extras" that make this one stand out.

For starters, it doesn't just present a single solution. It presents three , each one addressing a different aspect of ClickUp's objectives and each one showcasing a different Surfer feature set.

For example, solution #1 describes how ClickUp improved their on-page SEO with the help of Surfer’s Content Editor .

This case study also provides a high-level view of ClickUp’s project management processes and describes how they incorporated Surfer into their content workflows.

It’s a really instructive example of how you can use a case study to help prospective clients envision how your product might fit their situation.

Zoom’s library

This one isn't a single case study at all but a library full of case studies designed to help potential clients understand how Zoom can benefit them.

Here you'll find stories about how very recognizable organizations like Capital One, Vox Media, and the University of Miami are using Zoom to boost connectivity and productivity among remote workers.

There are plenty of good examples here that you can consult when you get stuck writing your own case study.

And the entire library is a great example of using case studies to demonstrate expertise with the help of social proof:

The Zoom case study library also makes liberal use of video, which might give you some good ideas about how you can, too.

Key takeaways

- Case studies are one of the best ways to generate leads and convert readers into customers.

- By showcasing the success you've had helping previous customers, case studies position you as an expert in your field.

- Good case studies can be the final push businesses need in their decision making process to buy your products or services.

- Pick a use case for your study that has broad appeal in your industry and that showcases your products and services in the best light possible.

- Effective case studies follow a predictable format: introduction, problem statement, solution, results, and conclusion.

- Make your case studies as readable as possible by including visual elements like graphs and images, and by breaking up the text into smaller sections, subsections, and concise paragraphs.

- Be as thorough and accurate as possible by conducting client interviews to gather background information for your case studies.

- Follow top-notch case studies for inspiration and ideas about how to make your own case studies as good as possible.

A well-written case study shines a light on your products and services like nothing else and helps position you as an expert in your field.

By showing that you understand their problems and have helped others overcome similar issues, you can prove to prospective clients that you are well-suited to help them, too.

Use the step-by-step instructions in this article to craft a case study that helps you and your company stand out from the competition.

https://surferseo.com/blog/write-case-study/

Get started now, 7 days for free

Choose a plan that fits your needs and try Surfer out for yourself. Click below to sign up!

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

A case study research paper examines a person, place, event, condition, phenomenon, or other type of subject of analysis in order to extrapolate key themes and results that help predict future trends, illuminate previously hidden issues that can be applied to practice, and/or provide a means for understanding an important research problem with greater clarity. A case study research paper usually examines a single subject of analysis, but case study papers can also be designed as a comparative investigation that shows relationships between two or more subjects. The methods used to study a case can rest within a quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-method investigative paradigm.

Case Studies. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010 ; “What is a Case Study?” In Swanborn, Peter G. Case Study Research: What, Why and How? London: SAGE, 2010.

How to Approach Writing a Case Study Research Paper

General information about how to choose a topic to investigate can be found under the " Choosing a Research Problem " tab in the Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper writing guide. Review this page because it may help you identify a subject of analysis that can be investigated using a case study design.

However, identifying a case to investigate involves more than choosing the research problem . A case study encompasses a problem contextualized around the application of in-depth analysis, interpretation, and discussion, often resulting in specific recommendations for action or for improving existing conditions. As Seawright and Gerring note, practical considerations such as time and access to information can influence case selection, but these issues should not be the sole factors used in describing the methodological justification for identifying a particular case to study. Given this, selecting a case includes considering the following:

- The case represents an unusual or atypical example of a research problem that requires more in-depth analysis? Cases often represent a topic that rests on the fringes of prior investigations because the case may provide new ways of understanding the research problem. For example, if the research problem is to identify strategies to improve policies that support girl's access to secondary education in predominantly Muslim nations, you could consider using Azerbaijan as a case study rather than selecting a more obvious nation in the Middle East. Doing so may reveal important new insights into recommending how governments in other predominantly Muslim nations can formulate policies that support improved access to education for girls.

- The case provides important insight or illuminate a previously hidden problem? In-depth analysis of a case can be based on the hypothesis that the case study will reveal trends or issues that have not been exposed in prior research or will reveal new and important implications for practice. For example, anecdotal evidence may suggest drug use among homeless veterans is related to their patterns of travel throughout the day. Assuming prior studies have not looked at individual travel choices as a way to study access to illicit drug use, a case study that observes a homeless veteran could reveal how issues of personal mobility choices facilitate regular access to illicit drugs. Note that it is important to conduct a thorough literature review to ensure that your assumption about the need to reveal new insights or previously hidden problems is valid and evidence-based.

- The case challenges and offers a counter-point to prevailing assumptions? Over time, research on any given topic can fall into a trap of developing assumptions based on outdated studies that are still applied to new or changing conditions or the idea that something should simply be accepted as "common sense," even though the issue has not been thoroughly tested in current practice. A case study analysis may offer an opportunity to gather evidence that challenges prevailing assumptions about a research problem and provide a new set of recommendations applied to practice that have not been tested previously. For example, perhaps there has been a long practice among scholars to apply a particular theory in explaining the relationship between two subjects of analysis. Your case could challenge this assumption by applying an innovative theoretical framework [perhaps borrowed from another discipline] to explore whether this approach offers new ways of understanding the research problem. Taking a contrarian stance is one of the most important ways that new knowledge and understanding develops from existing literature.

- The case provides an opportunity to pursue action leading to the resolution of a problem? Another way to think about choosing a case to study is to consider how the results from investigating a particular case may result in findings that reveal ways in which to resolve an existing or emerging problem. For example, studying the case of an unforeseen incident, such as a fatal accident at a railroad crossing, can reveal hidden issues that could be applied to preventative measures that contribute to reducing the chance of accidents in the future. In this example, a case study investigating the accident could lead to a better understanding of where to strategically locate additional signals at other railroad crossings so as to better warn drivers of an approaching train, particularly when visibility is hindered by heavy rain, fog, or at night.

- The case offers a new direction in future research? A case study can be used as a tool for an exploratory investigation that highlights the need for further research about the problem. A case can be used when there are few studies that help predict an outcome or that establish a clear understanding about how best to proceed in addressing a problem. For example, after conducting a thorough literature review [very important!], you discover that little research exists showing the ways in which women contribute to promoting water conservation in rural communities of east central Africa. A case study of how women contribute to saving water in a rural village of Uganda can lay the foundation for understanding the need for more thorough research that documents how women in their roles as cooks and family caregivers think about water as a valuable resource within their community. This example of a case study could also point to the need for scholars to build new theoretical frameworks around the topic [e.g., applying feminist theories of work and family to the issue of water conservation].

Eisenhardt, Kathleen M. “Building Theories from Case Study Research.” Academy of Management Review 14 (October 1989): 532-550; Emmel, Nick. Sampling and Choosing Cases in Qualitative Research: A Realist Approach . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2013; Gerring, John. “What Is a Case Study and What Is It Good for?” American Political Science Review 98 (May 2004): 341-354; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010; Seawright, Jason and John Gerring. "Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research." Political Research Quarterly 61 (June 2008): 294-308.

Structure and Writing Style

The purpose of a paper in the social sciences designed around a case study is to thoroughly investigate a subject of analysis in order to reveal a new understanding about the research problem and, in so doing, contributing new knowledge to what is already known from previous studies. In applied social sciences disciplines [e.g., education, social work, public administration, etc.], case studies may also be used to reveal best practices, highlight key programs, or investigate interesting aspects of professional work.

In general, the structure of a case study research paper is not all that different from a standard college-level research paper. However, there are subtle differences you should be aware of. Here are the key elements to organizing and writing a case study research paper.

I. Introduction

As with any research paper, your introduction should serve as a roadmap for your readers to ascertain the scope and purpose of your study . The introduction to a case study research paper, however, should not only describe the research problem and its significance, but you should also succinctly describe why the case is being used and how it relates to addressing the problem. The two elements should be linked. With this in mind, a good introduction answers these four questions:

- What is being studied? Describe the research problem and describe the subject of analysis [the case] you have chosen to address the problem. Explain how they are linked and what elements of the case will help to expand knowledge and understanding about the problem.

- Why is this topic important to investigate? Describe the significance of the research problem and state why a case study design and the subject of analysis that the paper is designed around is appropriate in addressing the problem.