Child Protection Forum | Community

Community Child Protection Exchange

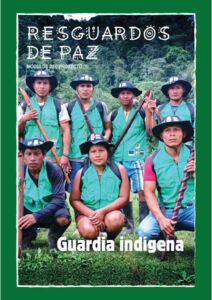

Resguardos de Paz – Módulos del proyecto. Guardia Indígena

Published: no date author: war child colombia.

Una historia de resistencia y protección Guardia Indígena. Acciones para la protección comunitaria, defensa de los derechos humanos y construcción de memoria histórica en comunidades indigenas en los departamentos de Choco y Antioquia, Colombia.

A SCHOOL FOR EVERY CHILD! Story of a community-led Initiative against school absenteeism in Jharkhand

Published: 2021 author: the inter-agency core group cini, chetna vikas, child resilience alliance, plan india, & praxis.

A short, illustrated story of a community-led initiative against school absenteeism in Khunti, Jharkhand, India.

Artbooks as witness of everyday resistance: Using art with displaced children living in Johannesburg, South Africa

Published: 2021 author: glynis clacherty.

Artbooks, which are a combined form of picture and story book created using mixed media, can be a simple yet powerful way of supporting children affected by war and displacement to tell their stories. They allow children to work through the creative arts, which protects them from being overwhelmed by difficult memories.

Ficha de situación – Chocó: Quibdó

Published: 2020 author: mire–mecanismo intersectorial de respuesta a emergencias.

Ficha de situación – Chocó: Quibdó. Comunidades de Villa nueva, Wounaan Phoboor y Wounaan la Paz.

Protecting children through village-based Family Support Groups in a post-conflict and refugee setting, Northern Uganda: A Case Study

Published: 2018 author: written by glynis clacherty, edited by lucy hillier, with contributions from mike wessells for the interagency learning initiative (ili).

This case study tells the story of a child protection programme developed by a community-based organisation called Children of the World that works in villages in northern Uganda. The Children of the World programme was chosen for this set of case studies because of its focus on the importance of a personal psychological process for real sustainable child protection.

Truck drivers stand for child protection – The story of the Regional Association of Truck Drivers Against Exploitation of Children, Uganda, Kampala/Mombasa trucking route: A Case Study

This case study tells the story of a regional association set up by truckers to protect children, in particular to stop truck drivers from picking up girls under 18 in the towns along the Uganda section of the Kampala-Mombasa trucking route. It tells the story of some of the truckers who took a stand against sexual exploitation of under-age girls as individuals and how they approached the Uganda Reproductive Health Bureau (URHB) to help them with technical information.

The Tatu Tano child-led organisation – Building child capacity and protective relationships through a child-led organisation, North-western Tanzania

Published: 2018 author: written by glynis clacherty, edited by lucy hillier, with contributions from mike wessells. photographs by james clacherty..

A case study collaboration between the Interagency Learning Initiative (ILI) on community-based child protection mechanisms, the Community Child Protection Exchange, and Kwa Wazee, Tanzania.

The story of the Vutamdogo Clubs, Mwanza, Tanzania. Youth clubs run livelihood projects and a literacy programme that provides protection for young children

A case study collaboration between the Interagency Learning Initiative (ILI) on community-based child protection mechanisms, the Community Child Protection Exchange, and Tanzanian Home Economics Association (TAHEA).

Weaving the web: documenting community-based development and child protection in Kolwezi, DRC

Published: 2018 author: mark canavera et al. with good shepherd international foundation.

The goal of this document – and the research process that underpins it – is to articulate the model that the Good Shepherd Sisters (GSS) have been implementing in Kolwezi in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). By consulting with stakeholders from multiple levels – the Good Shepherd Sisters and their staff, participants in their programmes, community members who are not involved in the programme, government and non-government partners, and mining company representatives – we aimed to document what the Good Shepherd Sisters have been doing in Kolwezi over the past five years with an eye to provide constructive recommendations about the future of the programme, which is currently under review for possible replication in areas around Kolwezi.

Tisser la Toile: documenter l’approche au développement communautaire et protection de l’enfance à Kolwezi, RDC

Published: 2018 author: mark canavera et al. avec good shepherd international foundation.

Le but de ce document et le processus de recherche qui le sous-tend est d’articuler le modèle que les Soeurs du Bon Pasteur (GSS) ont mis en place à Kolwezi en République Démocratique du Congo (RDC). En consultant des intervenants de multiples niveaux les Soeurs du Bon Pasteur et leur personnel, les participants de leurs programmes, les membres de la communauté qui ne participent pas au programme, les partenaires gouvernementaux et non gouvernementaux et les représentants des sociétés minières, nous avons cherché à documenter ce que les Soeurs du Bon Pasteur ont réalisées à Kolwezi au cours des cinq dernières années dans le but de fournir des recommandations constructives sur l’avenir du programme, qui est actuellement en cours de révision pour une réplication possible dans les zones situées autour de Kolwezi.

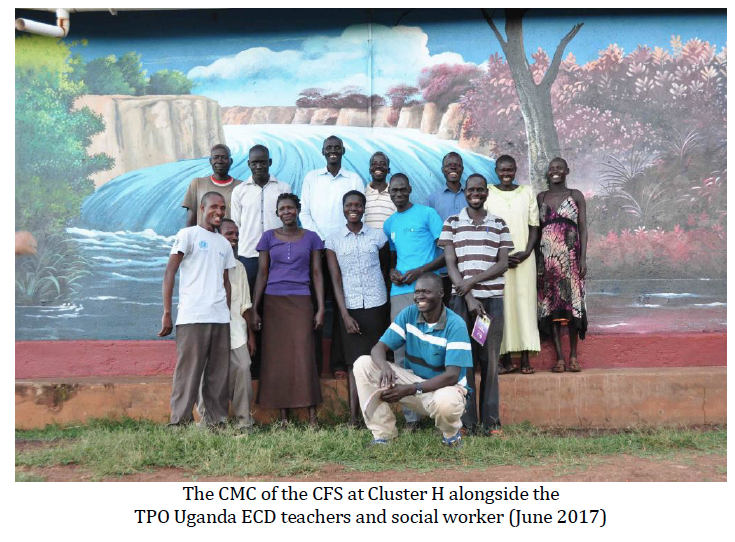

Community Management of Child Friendly Spaces Kiryandongo Refugee Settlement, Uganda. A case study.

Published: 2018 author: clacherty, g. published by the interagency learning intitative on community based child protection, the community child protection exchange and tpo uganda.

A case study collaboration between the Interagency Learning Initiative (ILI) on community-based child protection mechanisms, the Community Child Protection Exchange, and TPO Uganda.

Supporting Communities’ Disaster Resilience

Published: 2018 author: global communities.

A cross-sector example from the humanitarian response to disaster affected populations. Global Communities partners with communities to recover after natural disasters by addressing long-term needs and rebuilding climate-resilient infrastructure. It works with communities to strengthen their environmental resilience through climate change adaptation planning and disaster risk mitigation. The approach seeks to empower communities to identify, prioritise and find solutions to their most pressing needs. Haiti, Colombia, Nicaragua, Puerto Rico.

Building cross-sector collaboration using participatory action research to improve community health in an urban slum in Accra, Ghana

Published: 2018 author: jessica kritz.

A cross sector case study. Every urban slum creates challenges too complex for governments to resolve when working alone. Old Fadama, the largest slum in in Accra, Ghana, is home to over 100 000 people. Old Fadama has virtually no water or sanitation infrastructure, contributing to diminished quality of health and frequent cholera outbreaks when the nearby river floods. Our research introduces a model for cross-sector collaboration, supporting stakeholders who wanted to improve community health by installing latrines.

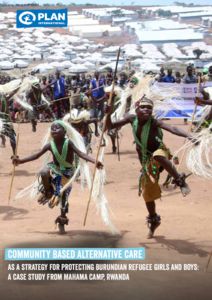

Community-based alternative care as a strategy for protecting Burundian refugee girls and boys: a case study from Mahama camp, Rwanda

Published: 2017 author: plan international.

A case study which describes the community-based child protection programme implemented between 2015 and 2016 with Burundian girls, boys and adults in Mahama refugee camp in Rwanda.

Barefoot Guide 5 – Mission Inclusion

Published: 2017 author: the fifth barefoot guide writer’s collective.

Many organisations, large and small, are tackling the deep challenges of exclusion and coming up with creative, innovative and workable solutions that are putting into practice the policies and strategies that everyone is talking about. This Barefoot Guide, written by 34 practitioners from 16 different countries on all continents makes many of these successful approaches and solutions more visible.

From the ground up: developing a national case management system for highly vulnerable children – An experience in Zimbabwe

Published: 2017 author: n. beth bradford.

A case study from Zimbabwe on how a national case management system for orphans and vulnerable children was built based on a community based care model.

How collaboration, early engagement and collective ownership increase research impact: Strengthening community-based child protection mechanisms in Sierra Leone

Published: 2017 author: michael wessells, david lamin, marie manyeh, dora king, lindsay stark, sarah lilley and kathleen kostelny.

Chapter 5 of the publication “The Social Realities of Knowledge for Development: Sharing Lessons of Improving Development Processes with Evidence” published by the International Development Institute, 2017. Using Interagency Learning Initiative (ILI) action research in Sierra Leone, this chapter from a DfiD provides a case study on how a highly collaborative approach can enable child protection research to achieve a significant national impact. The chapter describes how the inter-agency research facilitated a community-driven approach to addressing teenage pregnancy.

Presentation by Eddy Walakira – Kampala workshop, 17-18 August, 2016

Published: 2016 author: eddy walakira.

This presentation looks at the results of a War Child Holland initiative in Northern Uganda around prevention of violence against children in a post war setting.

Presentation by Patrick Onyango – Kampala workshop, 17-18 August, 2016

Published: 2016 author: patrick onyango.

A presentation on girl mothers in armed forces and groups and their children in Northern Uganda, Liberia and Sierra Leone – Participatory Action Research to assess and improve their situations.

Community engagement to strengthen social cohesion and child protection in Chad and Burundi – “Bottom Up” participatory monitoring, planning and action

Published: 2016 author: international institute for child rights and development (iicrd), dr. philip cook, michele cook, natasha blanchet cohen, armel oguniyi & jean sewanou.

A final report on action research which looked at how communities can help drive monitoring, planning and action around social cohesion strengthening and child protection in Chad and Burundi.

Tatu Tano – a portrait

Published: 2015 author: kurt madoerin. kwa wazee.

A background document on the Tatu Tano programme in Nshamba, Tanzania, Developed and implemented by Kwa Wazee.

Tatu Tano – a portrait

Published: 2015 author: kurt madoerin/kwa wazee.

An outline of the Tatu Tano programme and learning from 2015.

An Overview of the Community Driven Intervention To Reduce Teenage Pregnancy in Sierra Leone

Published: 2014 author: mike wessells, david lamin, & marie manyeh.

An overview of the Interagency Learning Initiative process of supporting community-driven action that addresses needs of vulnerable children in Bombali and Moyamba Districts of Sierra Leone.

National Child Protection Systems in the east Asia and Pacific region – a review and analysis of mappings and assessments

Published: 2014 author: ecpat international, plan international, save the children, unicef and world vision - ecpat international, bangkok.

A review of mappings and assessments of the child protection system in 14 countries was commissioned by the Inter-Agency Steering Committee (IASC), a subcommittee of the East Asia and Pacific Child Protection Working Group.

Etude sur les problématiques et les risques de protection de l’enfance – Etude de cas dans la région de Segou, Mali

Published: 2014 author: frédérique boursin-balkouma - sociologue - spécialiste en protection de l’enfant, ouagadougou, burkina faso. nouhoun sidibé - enseignant – chercheur - spécialiste en education, isfra, bamako, mali.

A travers un diagnostic participatif, l’étude commanditée par l’ONG Terre des hommes dans les districts sanitaires de Markala et Macina avait pour objectif d’identifier les problématiques et les risques de protection de l’enfance les plus répandus ; ainsi que de découvrir les pratiques endogènes de protection (PEP) existantes.

Study on the issues and risks for child protection in the Segou region in Mali

A participatory study sponsored by the Terre des Hommes NGO in the health districts of Markala and Macina which aimed to identify the most common risks for child protection as well as existing endogenous protection practices.

Research Brief: An Ethnographic Study of Community-Based Child Protection Mechanisms and their Linkages with the National Child Protection System of Sierra Leone

Published: 2012 author: inter-agency learning initiative on community-based child protection mechanisms and child protection systems.

This document serves as a seven-page summary of the longer report included among these research documents, “An Ethnographic Study of Community-Based Child Protection Mechanisms and their Linkages with the National Child Protection System of Sierra Leone.”

Kwa Wazee’s Impact assessment of Self Defense – the views of the participants

Published: 2011 author: kwa wazee.

A 2011 evaluation of the Kwa Wazee girl’s self-defence training initiative in Nshamba, Tanzania.

Tanzania: Linking community systems to a national model of child protection

Published: 2011 author: sian long, maestral international.

This report describes a child protection system strengthening initiative that was piloted in four districts in Tanzania. The aim of the initiative was to improve the delivery of social and protective services to all children, especially the most vulnerable, with a view towards building an evidence base for an effective child protection model that can be scaled up nationally.

Strengthening National Child Protection Systems in Emergencies through Community-Based Mechanisms: A Discussion Paper

Published: 2010 author: alyson eynon and sarah lilley for save the children uk on behalf of the child protection working group of the un protection cluster.

This discussion paper uses three case studies – Myanmar, the occupied Palestinian territories, and Timor Leste – to examine the state of evidence about strengthening national child protection systems through community-based mechanisms during emergencies.

Executive Summary: What are we learning about protecting children in the community?

Published: 2009 author: mike wessells, lead consultant, on behalf of an inter-agency working group.

This 20-page executive summary presents an overview of the key findings from a 2009 inter-agency review of the evidence on community-based child protection mechanisms. The full report is also available in this research section.

Sudan: An in-depth analysis of the social dynamics of abandonment of FGM/C

Published: 2009 author: samira ahmed, s. al hebshi and b. v. nylund for unicef innocenti research centre.

An Innocenti Working Paper Special Series on Social Norms and Harmful Practices.This paper examines the experience of Sudan by analysing the factors that promote and support the abandonment of female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) and other harmful social practices. Despite the fact that FGM/C is still widely practiced in all regions of northern Sudan, women’s intention to circumcise their daughters has decreased significantly during the last 16 years. Attitudes are changing and today, actors are mobilizing across the country to end the practice. This paper examines these changes. It analyses programmes that support ending FGM/C in Sudan and highlights the key factors that promote collective abandonment of the practice, including the roles of community dialogue, human rights deliberation, community-led activities, and the powerful force of local rewards and punishment.

A Common Responsibility: The role of community-based groups in protection children from sexual abuse and exploitation – a discussion paper

Published: 2008 author: sarah lilley for save the children uk.

This 2008 discussion paper shares Save the Children’s experience in working with community-based groups; the paper is an effort to stimulate dialogue by highlighting the successes and challenges of such work.

Mobilising Children & Youth into their Own Child- & Youth-led Organisations

Published: 2008 author: kurt madoerin. published by repssi.

Several decades of experience in working with vulnerable children across the planet had resulted in Kurt coming to believe that in the face of family, community and societal disintegration, the single most important supportive “intervention” that could be offered “to”, and more importantly “with” children and youth, might be the mobilisation of children and youth into their own child-led and youth-led organisations.

Community Action and the Test of Time: Learning from Community Experiences and Perceptions

Published: 2006 author: jill donahue and louis mwewa.

Case studies of mobilisation and capacity building to benefit vulnerable children in Malawi and Zambia.

Impact Evaluation of the VSI (Vijana Simama Imara) organisation and the Rafiki Mdogo group of the HUMULIZA orphan project Nshamba, Tanzania

Published: 2005 author: glynis clacherty and professor david donald.

The aims of the Humuliza Project are to develop a practical instrument to enable

teachers and caregivers to support orphans psychologically and to develop the

orphans’ own capacity to cope with the loss of their caretakers.

Latest Addition

A community keeping its children safe, what i’ve learned podcast.

IMAGES

VIDEO