Hedy Lamarr

Hedy Lamarr was an Austrian American actress during MGM's "Golden Age" who also left her mark on technology. She helped develop an early technique for spread spectrum communications.

(1914-2000)

Who Was Hedy Lamarr?

Hedy Lamarr was an actress during MGM's "Golden Age." She starred in such films as Tortilla Flat, Lady of the Tropics, Boom Town and Samson and Delilah , with the likes of Clark Gable and Spencer Tracey. Lamarr was also a scientist, co-inventing an early technique for spread spectrum communications — the key to many wireless communications of our present day. A recluse later in life, Lamarr died in her Florida home in 2000.

Lamarr was born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler on November 9, 1914, in Vienna, Austria. Discovered by an Austrian film director as a teenager, she gained international notice in 1933, with her role in the sexually charged Czech film Ecstasy . After her unhappy marriage ended with Fritz Mandl, a wealthy Austrian munitions manufacturer who sold arms to the Nazis, she fled to the United States and signed a contract with the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studio in Hollywood under the name Hedy Lamarr. Upon the release of her first American film, Algiers , co-starring Charles Boyer, Lamarr became an immediate box-office sensation.

Often referred to as one of the most gorgeous and exotic of Hollywood's leading ladies, Lamarr made a number of well-received films during the 1930s and 1940s. Notable among them were Lady of the Tropics (1939), co-starring Robert Taylor; Boom Town (1940), with Clark Gable and Spencer Tracy; Tortilla Flat (1942), co-starring Tracy; and Samson and Delilah (1949), opposite Victor Mature. She was reportedly producer Hal Wallis's first choice for the heroine in his classic 1943 film, Casablanca , a part that eventually went to Ingrid Bergman .

'Secret Communications System'

In 1942, during the heyday of her career, Lamarr earned recognition in a field quite different from entertainment. She and her friend, the composer George Antheil, received a patent for an idea of a radio signaling device, or "Secret Communications System," which was a means of changing radio frequencies to keep enemies from decoding messages. Originally designed to defeat the German Nazis, the system became an important step in the development of technology to maintain the security of both military communications and cellular phones.

Lamarr wasn't instantly recognized for her communications invention since its wide-ranging impact wasn't understood until decades later. However, in 1997, Lamarr and Antheil were honored with the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) Pioneer Award, and that same year Lamarr became the first female to receive the BULBIE™ Gnass Spirit of Achievement Award, considered the "Oscars" of inventing.

Later Career

Lamarr's film career began to decline in the 1950s; her last film was 1958's The Female Animal , with Jane Powell. In 1966, she published a steamy best-selling autobiography, Ecstasy and Me , but later sued the publisher for what she saw as errors and distortions perpetrated by the book's ghostwriter. She was arrested twice for shoplifting, once in 1966 and once in 1991, but neither arrest resulted in a conviction.

Personal Life, Death and Legacy

Lamarr was married six times. She adopted a son, James, in 1939, during her second marriage to Gene Markey. She went on to have two biological children, Denise (b. 1945) and Anthony (b. 1947), with her third husband, actor John Loder, who also adopted James.

In 1953, Lamarr completed the naturalization process and became a U.S. citizen.

In her later years, Lamarr lived a reclusive life in Casselberry, a community just north of Orlando, Florida, where she died on January 19, 2000, at the age of 85.

Documentary and Pop Culture

In 2017, director Alexandra Dean shined a light on the Hollywood starlet/unlikely inventor with a new documentary, Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story . Along with delving into her pioneering technological work, the documentary explores other examples in which Lamarr proved to be far more than just a pretty face, as well as her struggles with crippling drug addiction.

A dramatized version of Lamarr featured in a March 2018 episode of the TV series Timeless , which centered on her efforts to help the time-traveling team recover a stolen workprint of the 1941 classic Citizen Kane .

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Hedy Lamarr

- Birth Year: 1914

- Birth date: November 9, 1914

- Birth City: Vienna

- Birth Country: Austria

- Best Known For: Hedy Lamarr was an Austrian American actress during MGM's "Golden Age" who also left her mark on technology. She helped develop an early technique for spread spectrum communications.

- Astrological Sign: Scorpio

- Nacionalities

- Interesting Facts

- Hedy Lamarr was arrested twice for shoplifting, in 1966 and 1991, though neither arrest resulted in a conviction.

- Death Year: 2000

- Death date: January 19, 2000

- Death State: Florida

- Death City: Casselberry

- Death Country: United States

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Hedy Lamarr Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/actors/hedy-lamarr

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: April 19, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

Famous Actors

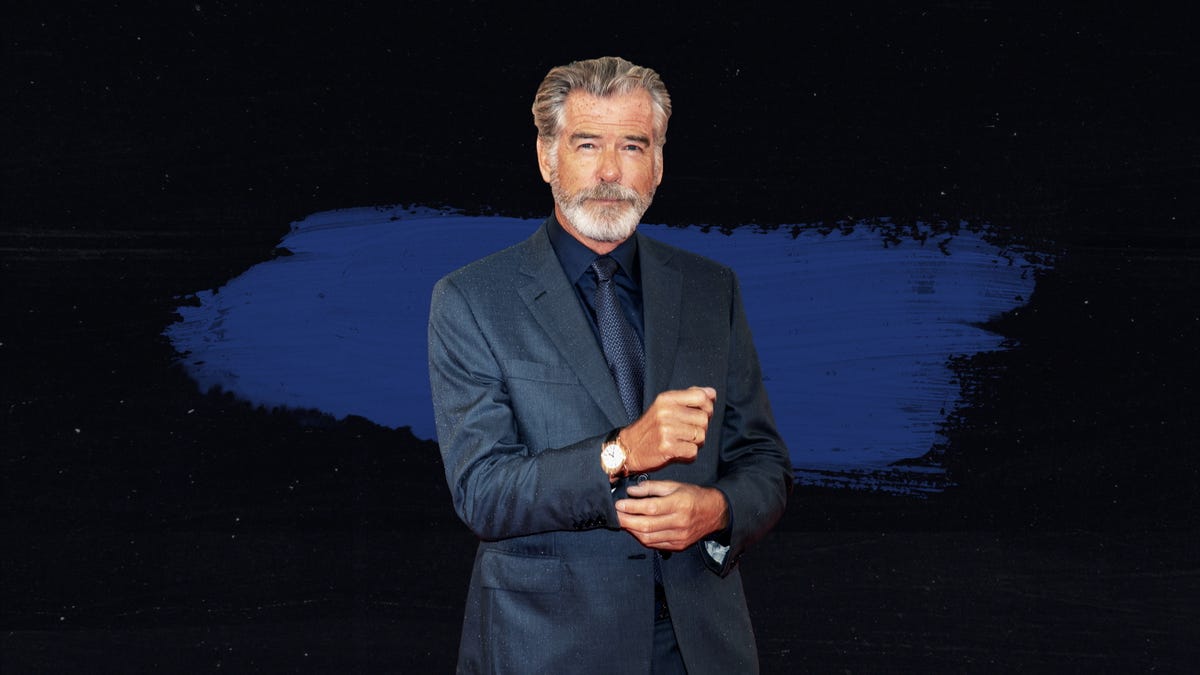

Kevin Costner

Willem Dafoe

Peggy Lipton

Ralph Fiennes

Angelina Jolie

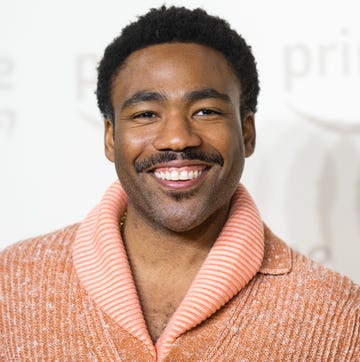

Donald Glover

Get to Know ‘Terrifier 3’ Actor Lauren LaVera

You Definitely Forgot These Actors Were on ‘SNL’

Cynthia Erivo

Paul Mescal

Hedy Lamarr

Hedy Lamarr was an Austrian-American actress and inventor who pioneered the technology that would one day form the basis for today’s WiFi, GPS, and Bluetooth communication systems. As a natural beauty seen widely on the big screen in films like Samson and Delilah and White Cargo , society has long ignored her inventive genius.

Lamarr was originally Hedwig Eva Kiesler, born in Vienna, Austria on November 9 th , 1914 into a well-to-do Jewish family. An only child, Lamarr received a great deal of attention from her father, a bank director and curious man, who inspired her to look at the world with open eyes. He would often take her for long walks where he would discuss the inner-workings of different machines, like the printing press or street cars. These conversations guided Lamarr’s thinking and at only 5 years of age, she could be found taking apart and reassembling her music box to understand how the machine operated. Meanwhile, Lamarr’s mother was a concert pianist and introduced her to the arts, placing her in both ballet and piano lessons from a young age.

Lamarr’s brilliant mind was ignored, and her beauty took center stage when she was discovered by director Max Reinhardt at age 16. She studied acting with Reinhardt in Berlin and was in her first small film role by 1930, in a German film called Geld auf der Stra βe (“Money on the Street”). However, it wasn’t until 1932 that Lamarr gained name recognition as an actress for her role in the controversial film, Ecstasy .

Austrian munitions dealer, Fritz Mandl, became one of Lamarr’s adoring fans when he saw her in the play Sissy . Lamarr and Mandl married in 1933 but it was short-lived. She once said, “I knew very soon that I could never be an actress while I was his wife … He was the absolute monarch in his marriage … I was like a doll. I was like a thing, some object of art which had to be guarded—and imprisoned—having no mind, no life of its own.” She was incredibly unhappy, as she was forced to play host and smile on demand amongst Mandl’s friends and scandalous business partners, some of whom were associated with the Nazi party. She escaped from Mandl’s grasp in 1937 by fleeing to London but took with her the knowledge gained from dinner-table conversation over wartime weaponry.

While in London, Lamarr’s luck took a turn when she was introduced to Louis B. Mayer, of the famed MGM Studios. With this meeting, she secured her ticket to Hollywood where she mystified American audiences with her grace, beauty, and accent. In Hollywood, Lamarr was introduced to a variety of quirky real-life characters, such as businessman and pilot Howard Hughes.

Lamarr dated Hughes but was most notably interested with his desire for innovation. Her scientific mind had been bottled-up by Hollywood but Hughes helped to fuel the innovator in Lamarr, giving her a small set of equipment to use in her trailer on set. While she had an inventing table set up in her house, the small set allowed Lamarr to work on inventions between takes. Hughes took her to his airplane factories, showed her how the planes were built, and introduced her to the scientists behind process. Lamarr was inspired to innovate as Hughes wanted to create faster planes that could be sold to the US military. She bought a book of fish and a book of birds and looked at the fastest of each kind. She combined the fins of the fastest fish and the wings of the fastest bird to sketch a new wing design for Hughes’ planes. Upon showing the design to Hughes, he said to Lamarr, “You’re a genius.”

Lamarr was indeed a genius as the gears in her inventive mind continued to turn. She once said, “Improving things comes naturally to me.” She went on to create an upgraded stoplight and a tablet that dissolved in water to make a soda similar to Coca-Cola. However, her most significant invention was engineered as the United States geared up to enter World War II.

In 1940 Lamarr met George Antheil at a dinner party. Antheil was another quirky yet clever force to be reckoned with. Known for his writing, film scores, and experimental music compositions, he shared the same inventive spirit as Lamarr. She and Antheil talked about a variety of topics but of their greatest concerns was the looming war. Antheil recalled, “Hedy said that she did not feel very comfortable, sitting there in Hollywood and making lots of money when things were in such a state.” After her marriage to Mandl, she had knowledge on munitions and various weaponry that would prove beneficial. And so, Lamarr and Antheil began to tinker with ideas to combat the axis powers.

The two came up with an extraordinary new communication system used with the intention of guiding torpedoes to their targets in war. The system involved the use of “frequency hopping” amongst radio waves, with both transmitter and receiver hopping to new frequencies together. Doing so prevented the interception of the radio waves, thereby allowing the torpedo to find its intended target. After its creation, Lamarr and Antheil sought a patent and military support for the invention. While awarded U.S. Patent No. 2,292,387 in August of 1942, the Navy decided against the implementation of the new system. The rejection led Lamarr to instead support the war efforts with her celebrity by selling war bonds. Happy in her adopted country, she became an American citizen in April 1953.

Meanwhile, Lamarr’s patent expired before she ever saw a penny from it. While she continued to accumulate credits in films until 1958, her inventive genius was yet to be recognized by the public. It wasn’t until Lamarr’s later years that she received any awards for her invention. The Electronic Frontier Foundation jointly awarded Lamarr and Antheil with their Pioneer Award in 1997. Lamarr also became the first woman to receive the Invention Convention’s Bulbie Gnass Spirit of Achievement Award. Although she died in 2000, Lamarr was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame for the development of her frequency hopping technology in 2014. Such achievement has led Lamarr to be dubbed “the mother of Wi-Fi” and other wireless communications like GPS and Bluetooth.

Bedi, Joyce. “A Movie Star, Some Player Pianos, and Torpedoes.” Smithsonian National Museum of American History: Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation, November 12, 2015.

Camhi, Leslie. “Hedy Lamarr’s Forgotten, Frustrated Career as a Wartime Inventor.” The New Yorker , December 3, 2017.

DeFore, John. “'Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story': Film Review | Tribeca 2017.” The Hollywood Reporter , April 25, 2017.

“Hedy Lamarr: Biography.” IMDb.com.

“Hedy Lamarr Biography.” Biography.com. April 2, 2014.

“'Most Beautiful Woman' By Day, Inventor By Night.” All Things Considered , NPR, November 22, 2011.

“Women in Science: How Hedy Lamarr Pioneered Modern Wi-Fi Technology.” TEDxUCLWomen. July 30, 2017.

Y.F.. “The incredible inventiveness of Hedy Lamarr.” The Economist, November 23, 2017.

APA: Cheslak, C. (2018, August 30). Hedy Lamarr. Retrieved from https://www.womenshistory.org/students-and-educators/biographies/hedy-lamarr

MLA: Cheslak, Colleen. “Hedy Lamarr.” Hedy Lamarr , National Women's History Museum, 30 Aug. 2018, www.womenshistory.org/students-and-educators/biographies/hedy-lamarr.

Chicago:Cheslak, Colleen. "Hedy Lamarr." Hedy Lamarr. August 30, 2018. https://www.womenshistory.org/students-and-educators/biographies/hedy-lamarr.

Rhodes, Richard. Hedy's Folly: The Life and Breakthrough Inventions of Hedy Lamarr, the Most Beautiful Woman in the World . New York: Doubleday, 2011.

Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story. Directed by Alexandra Dean. New York: Zeitgeist Films, November 24, 2017.

Related Biographies

Stacey Abrams

Abigail Smith Adams

Jane Addams

Toshiko Akiyoshi

Related background, exploring maria tallchief: a dance journey through history, agnes demille’s rodeo and images of women on the frontier, voices of change: analyzing speeches by lgbtq+ women, mary church terrell .

- World Biography

- Supplement (Ka-Mé)

Hedy Lamarr Biography

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); Austrian-born American actress Hedy Lamarr (1913–2000) was among the leading screen sirens of Hollywood in the 1940s. Her life was an eventful one that involved six marriages, a groundbreaking electronic invention, and several cinematic milestones.

Born to Bank Director and Pianist

Lamarr was born Hedwig Kiesler in Vienna, Austria, on November 9, 1913. Her family was Jewish and well off; her father was a Bank of Vienna director and her mother a concert pianist. Lamarr attended schools in Vienna and was sent to a finishing school in Switzerland as a teenager. By that time she was already unusually beautiful, attracting the attention of both prospective lovers and film producers. After an unsuccessful audition with famed stage director, Max Reinhardt, from whom she had taken acting lessons, Lamarr moved into films. Her screen career began in 1930 with a pair of Austrian films, Money on the Street and Storm in a Waterglass .

She had several other small roles in German-language films, but it took controversy to put Lamarr on the cinematic map. In 1932 she made a film called Extase (or Ecstasy) in Czechoslovakia; it was released the following year. The film told the simple story of a young woman whose husband is impotent, causing her to seek out the companionship of a younger man. Two scenes were responsible for the film's notoriety and quick banning by Austrian censors: one in which Lamarr runs nude through a sunlit forest, the other a sex scene in which she seems to experience orgasm (her intense facial expressions actually resulted from the application of a safety pin to her buttock by director Gustav Machaty). Lamarr later said that she had been a naive young woman pressured into doing these scenes, but cameraman Jan Stallich told Jan Christopher Horak of CineAction that "as the star of the picture, she knew she would have to appear naked in some scenes. She never made any fuss about it during the production."

Controversy and condemnation from Pope Pius XI temporarily halted Lamarr's film career, but Extase did attract the attention of millionaire Austrian arms dealer Fritz Mandl, whom Lamarr met in December of 1933 and then married. Mandl had converted from Judaism to Catholicism in order to be able to do business with Germany's fascist regime (he was nevertheless exiled to Argentina after Austria came under German control in 1938), and Lamarr also made her religious conversion in 1933. An often-repeated story holds that Mandl tried to buy and destroy every outstanding copy of Extase , but this is thought to be legend rather than fact. Whether out of revulsion toward her husband's politics or from sheer restlessness, Lamarr packed a single suitcase with jewelry, drugged her maid, and fled to Paris and then London in 1937. That September she sailed for New York.

On board, she began negotiating with producer Louis B. Mayer of the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (M-G-M) studio, who had signed Swedish actress Greta Garbo several years earlier and was on the lookout for exotic European talent. Lamarr had refused Mayer's contract offer in London, but by the time the ship docked in New York she had a $500-a-week contract and the new name of Hedy Lamarr—up to that point she had used Hedi Kiesler. Mayer devised the name, inspired by that of silent film actress Barbara La Marr.

Starred Opposite Charles Boyer

Lamarr's first film in the United States was Algiers (1938), in which she played opposite French actor Charles Boyer as a woman who, though engaged to another man, has an affair with an escaped thief (Boyer). The film was a successful launch for Lamarr's American career, but it was followed by two flops, Lady of the Tropics (1939) and I Take This Woman (1940), the latter co-starring Spencer Tracy and dubbed I Re-Take This Woman after Mayer demanded numerous changes in the script. The actress's fortunes turned around later in 1940 with Boom Town , with Clark Gable in the lead role, and Comrade X , a sort of anti-Communist romance in which Lamarr played a Soviet streetcar driver who falls in love with an American reporter (Clark Gable).

Throughout World War II, Lamarr was a fixture on American movie screens with such films as Come Live with Me (1941), Ziegfeld Girl (1941), and the steamy White Cargo (1943), in which Lamarr played a mixed-race prostitute on an African rubber plantation (although censors demanded that references to her character's ethnicity be removed from the script). With such films as 1943's The Heavenly Body (the title ostensibly referred to astronomy), Lamarr emerged in the first rank of screen sex symbols. A poll of Columbia University male undergraduates ranked Lamarr as the actress they would most like to be marooned with on an island, and in 1942 Lamarr participated in the World War II mobilization effort by offering to kiss any man who would purchase $25,000 in War Bonds. She raised $17 million with 680 kisses. In 1943, Lamarr was rumored to have been in the running for (or to have turned down) the role that eventually went to Swedish actress Ingrid Bergman in Casablanca .

Lamarr had plenty of space in celebrity gossip columns to go with her screen stardom. She dated silent comedian Charlie Chaplin in 1941, and had flings with Burgess Meredith and several other actors. Lamarr married producer Gene Markey in 1939, divorcing him the following year. For four years she was married to English actor John Loder and had two children by him. Later in life Lamarr was married three more times, to bandleader Teddy Stauffer, Texas oil magnate Howard Lee, and lawyer Lewis Boles. All her marriages ended in divorce. Another man with whom Lamarr may have been romantically involved was composer George Antheil.

Antheil played an important role in Lamarr's life in another way as well—as a collaborator on an important electronics innovation. Lamarr was slightly dismissive of her glamorous image, saying (according to her U.S. News & World Report obituary), "Any girl can be glamorous. All you have to do is stand still and look stupid." Lamar, by contrast, had been astute enough to pick up a good deal of practical knowledge pertaining to munitions engineering during her marriage to Mandl. In 1940 she had the idea for a solution to the problem of controlling a radio-guided torpedo. At that time, electronic data broadcast on a specific frequency could easily be jammed by enemy transmitters. Lamarr suggested rapid changes in the broadcast frequency, and Antheil, who had experimented with electronic musical instruments, devised a punch-card-like device, similar to a player-piano roll, that could synchronize a transmitter and receiver. The system Lamarr and Antheil invented relied on using 88 frequencies, equivalent to the number of keys on a piano.

Realized No Money from Invention

The pair were jointly awarded a patent for their discovery, but Antheil later credited the original idea entirely to Lamarr. Credit did not matter, however, for the idea, later given the name of frequency hopping, was never applied by the military during World War II. It was later rediscovered independently and used in ships sent to Cuba during the missile crisis of 1962. The real payoff of frequency hopping came only decades later, when it became integral to the operation of cellular telephones and Bluetooth systems that enabled computers to communicate with peripheral devices. By that time, Lamarr and Antheil's patent had long since expired.

Experiment Perilous (1944), directed by Jacques Tourneur, was considered one of Lamarr's best films, but her career gradually declined after World War II. The most visible outing from this phase of her career was the Cecil B. DeMille-produced Samson and Delilah (1949), with Victor Mature and Lamarr in the title roles. The film, in Horak's words, "marries an Old Testament-style, evangelical Christian moralism with the theatrical exploitation of unadulterated sex." For David Thomson of London's Independent on Sunday , the film had "many moments where [Lamarr's] foreign voice, her basilisk gaze, and her sinful body combine to magnificent effect."

Lamarr made several films in the 1950s, mostly operating outside of the Hollywood system. In the 1954 Italian-made feature The Loves of Three Queens she played Helen of Troy, and she took on another historical role as Joan of Arc in The Story of Mankind (1958). Her heyday was past, however, and she stayed away from Hollywood for much of the time. In 1950 she sold off all of her possessions in an auction and announced that she was moving to Mexico. A marriage brought her back to the United States and to Texas in 1955, and in retirement she moved to Florida. Occasionally she appeared on television. In 1967 she published an autobiography, Ecstasy and Me: My Life as a Woman , but sued the ghostwriters she had employed, claiming (according to Thomson), that the book was "fictional, false, vulgar, scandalous, libelous, and obscene."

That was one of several episodes that saw Lamarr entering courtrooms in her later years. Lamarr was arrested in 1966 for shoplifting at Macy's department store, but was acquitted. She complained to a columnist that she had once had a $7 million income but by the late 1960s was subsisting on a $48-a-week pension. Another round of litigation came after the release of director Mel Brooks's Western film parody Blazing Saddles in 1974; the actress objected to the fanciful "Hedley Lamarr" name of one of the movie's characters.

Lamarr lived mostly in isolation in a small house in Orlando in the last years of her life, reportedly staying out of the spotlight partly because of unsuccessful plastic surgery. She antagonized the organizers of a film festival with unreasonable demands for a makeup retinue. In 1990, however, she had a cameo role in the satire Instant Karma , and she lived long enough to see a modest renewal of interest in the sexually independent persona she had often projected on film. The story of her radio transmission invention also became widely publicized in the 1990s, and she received an Electronic Frontier Foundation Pioneer Award in 1997, although she never received any monetary award for her ingenuity. On January 19, 2000, Hedy Lamarr died at her home in Orlando.

Lamarr, Hedy, Ecstasy and Me: My Life as a Woman , Fawcett, 1967.

World of Invention , 2nd ed., Gale, 1999.

Young, Christopher, The Films of Hedy Lamarr , Citadel, 1978.

Periodicals

CineAction , Spring 2001.

Economist , June 21, 2003.

Entertainment Weekly , February 4, 2000.

Forbes , May 14, 1990.

Independent on Sunday (London, England), January 30, 2005.

People , February 7, 2000.

U.S. News & World Report , January 31, 2000.

"Hedy Lamarr," All Movie Guide , http://www.allmovie.com (January 20, 2007).

User Contributions:

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic:.

Registration

Biography of Hedy Lamarr

Early life and acting career, marriage and invention, escape and hollywood career, invention of frequency hopping spread spectrum, later life and legacy.

Hedy Lamarr was an Austrian-American actress, scientist, and inventor. She gained fame for her relatively provocative roles and her involvement in the development of several technologies that are still widely used in wireless data transmission today.

Hedy Lamarr was born as Hedwig in Vienna, Austria-Hungary. She was the only child of banker Emil Kiesler and his wife Gertrud. At the age of 10, Hedy began learning to play the piano. She had the opportunity to work with Max Reinhardt, who called Lamarr the "most beautiful woman in Europe". As a teenager, she started playing lead roles in German films alongside stars like Heinz Rühmann and Hans Moser. In 1933, Lamarr played the lead role in the controversial film "Ecstasy" by Gustav Machatý, which featured a scene of her swimming naked in a lake and an explicit close-up of her face during an orgasm.

In August 1933, Lamarr married Viennese weapons manufacturer Friedrich Mandl, who was 13 years older than her. Mandl, a controlling and possessive man, did not approve of Lamarr's acting career, especially after the release of "Ecstasy". However, it was through her husband that Lamarr discovered her passion for technology. Mandl often took her to meetings with technicians and business partners, where Lamarr's mathematical skills came in handy. Despite the lack of freedom in her marriage, Lamarr found a new calling thanks to her husband.

In 1937, Lamarr disguised herself as one of her maids and fled from Mandl's castle. She managed to obtain a divorce and moved to Paris, where she met Louis B. Mayer. With Mayer's help, Lamarr returned to the film industry. During this time, she adopted the stage name Hedy Lamarr, inspired by silent film star Barbara La Marr. In Hollywood, Lamarr was often cast as a seductive femme fatale. She made her American film debut in "Algiers" in 1938 and went on to star in films like "Boom Town" (1940) with Clark Gable and Spencer Tracy, and "White Cargo" (1942).

While in Hollywood, Lamarr met composer and inventor George Antheil. Together, they developed a system for transmitting information using a technique called "Frequency Hopping Spread Spectrum". They initially applied this technology to mechanical pianos. The U.S. Navy later used the system during the Cuban blockade in 1962. Today, frequency hopping spread spectrum is widely used in technologies such as Bluetooth, CDMA, and COFDM. Lamarr's invention was not recognized until years later, and she was posthumously inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

After leaving MGM in 1945, Lamarr's acting career gradually declined. She turned down numerous script offers and became tired of the excessive fame. Lamarr's desire for privacy, along with vision problems, led her to move to Miami Beach, Florida. Hedy Lamarr passed away on January 19, 2000, at the age of 86. Her contributions as both an actress and inventor continue to be celebrated, and her birthday, November 9, is recognized as "Inventors' Day" in Germany.

© BIOGRAPHS

Hedy Lamarr

The Official Website of Hedy Lamarr

The Most Beautiful Woman in Film

Often called “The Most Beautiful Woman in Film,” Hedy Lamarr’s beauty and screen presence made her one of the most popular actresses of her day.

She was born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler on November 9, 1914 in Vienna, Austria. At 17 years old, Hedy starred in her first film, a German project called Geld auf der Strase . Hedy continued her film career by working on both German and Czechoslavakian productions. The 1932 German film Exstase brought her to the attention of Hollywood producers, and she soon signed a contract with MGM.

Once in Hollywood, she officially changed her name to Hedy Lamarr and starred in her first Hollywood film, Algiers (1938), opposite Charles Boyer. She continued to land parts opposite the most popular and talented actors of the day, including Spencer Tracy, Clark Gable, and Jimmy Stewart. Some of her films include an adaptation of John Steinbeck’s Tortilla Flat (1942), White Cargo (1942), Cecil B. DeMille’s Samson and Delilah (1949), and The Female Animal (1957).

Beyond the Glitz & Glamour of Hollywood

As if being a beautiful, talented actress was not enough, Hedy was also a gifted mathematician, scientist, and innovator. Alongside the famed composer George Antheil, Lamarr patented the "Secret Communication System" during World War II. Her idea - now referred to as "frequency hopping" - pertained to a way for radio guidance transmitters and torpedo's receivers to jump simultaneously from frequency to frequency. The Hollywood star's invention sought to put an end to enemies' interception of classified military strategies, signals, and messages. While the technology of the time prevented the feasibility of "frequency hopping" at first, the advent of the transistor and its later downsizing propelled Lamarr's idea far in both the military and the cell phone industry.

Overall, the Hollywood actress introduced the technology that would serve as the foundation of modern-day WiFi, GPS, and Bluetooth communication systems. Her creation of "frequency hopping," which holds an estimated worth of $30 billion, led her to receive the Pioneer Award of the Electronic Frontier Foundation as well as the Invention Convention's Bulbie Gnass Spirit of Achievement Award.

Lamarr's impressive technological achievement combined with her acting talent and star quality makes "The Most Beautiful Woman in Film" one of the most accomplished and intelligent women in not only Hollywood but also STEM.

Hedy Lamarr

Celebrated as “the most beautiful woman in the world” during her Hollywood heyday in the 1940s, film star Hedy Lamarr (1914–2000) ultimately proved that her brain was even more extraordinary than her beauty. Eager to aid Allied forces during World War II, she explored potential military applications for radio technology. She theorized that varying radio frequencies at irregular intervals would prevent interception or jamming of transmissions, thereby creating an innovative communication system. Lamarr shared her concept for utilizing “frequency hopping” with the U.S. Navy and codeveloped a patent in 1941. Today, Lamarr’s innovation makes possible a wide range of wireless communications technologies, including Wi-Fi, GPS, and Bluetooth.

James Stewart, Hedy Lamarr, Judy Garland, Lana Turner, and Tony Martin in a Paint Book from Ziegfeld Girl

Object Details

COMMENTS

Hedy Lamarr was an Austrian American actress during MGM's "Golden Age" who also left her mark on technology. She helped develop an early technique for spread spectrum communications.

Hedy Lamarr (born November 9, 1913/14, Vienna, Austria—died January 19, 2000, near Orlando, Florida, U.S.) was an Austrian-born American film star who was often typecast as a provocative femme fatale. Years after her screen career ended, she achieved recognition as a noted inventor of a radio communications device.

Hedy Lamarr (/ ˈ h ɛ d i /; born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler; November 9, 1914 [a] - January 19, 2000) was an Austrian-born American actress and inventor. After a brief early film career in Czechoslovakia, including the controversial erotic romantic drama Ecstasy (1933), she fled from her first husband, Friedrich Mandl, and secretly moved to Paris.. Traveling to London, she met Louis B. Mayer ...

Hedy Lamarr was an Austrian-American actress and inventor who pioneered the technology that would one day form the basis for today's WiFi, GPS, and Bluetooth communication systems. As a natural beauty seen widely on the big screen in films like Samson and Delilah and White Cargo , society has long ignored her inventive genius.

Hedy Lamarr Biography. Austrian-born American actress Hedy Lamarr (1913-2000) was among the leading screen sirens of Hollywood in the 1940s. Her life was an eventful one that involved six marriages, a groundbreaking electronic invention, and several cinematic milestones. ...

Biography of Hedy Lamarr Hedy Lamarr was an Austrian-American actress, scientist, and inventor. She gained fame for her relatively provocative roles and her involvement in the development of several technologies that are still widely used in wireless data transmission today. Early Life and Acting Career Hedy Lamarr was born as Hedwig in Vienna, Austria-Hungary.

Often called "The Most Beautiful Woman in Film," Hedy Lamarr's beauty and screen presence made her one of the most popular actresses of her day. She was born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler on November 9, 1914 in Vienna, Austria. At 17 years old, Hedy starred in her first film, a German project called Geld auf der Strase. Hedy continued her film ...

Hedy Lamarr was an Austrian-American actress and inventor who co-invented the technology for spread spectrum. A very famous actress of her time, she is credited to be one of the most beautiful women to have ever graced the silver screen. Fascinated by cinema from childhood, she decided early on to become an actress and began her acting career as a teenager after being discovered by a film ...

Celebrated as "the most beautiful woman in the world" during her Hollywood heyday in the 1940s, film star Hedy Lamarr (1914-2000) ultimately proved that her brain was even more extraordinary than her beauty. Eager to aid Allied forces during World War II, she explored potential military applications for radio technology. She theorized that varying radio frequencies at irregular intervals ...

Lamarr was born Hedwig Eva Maria (Hedy) Kiesler on November 9, 1913/14, in Vienna, Austria. The daughter of a prosperous banker, she was privately tutored from age 4. By the time she was 10, Lamarr was a proficient pianist and dancer and could speak four languages. At age 16 Lamarr enrolled in Max Reinhardt's drama