ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

The impact of perspective taking on obesity stereotypes: the dual mediating effects of self-other overlap and empathy.

- School of Psychology, Inner Mongolia Normal University, Hohhot, China

Previous studies have indicated that obese people face many forms of severe prejudice and discrimination in various settings, such as education, employment, and interpersonal relationships. However, research aimed at reducing obesity stereotyping is relatively rare, and prior studies have focused primarily on negative stereotypes. Based on the empathy-altruism hypothesis and self-other overlap hypothesis, this study investigates the impact of perspective taking (PT) on both positive and negative obesity stereotypes and examines the mediating effects of empathy and self-other overlap. A sample of 687 students (191 males and 496 females) at Chinese universities participated by completing self-report questionnaires on trait tendency and evaluation toward obese people. Structural equation modeling and the bootstrap method revealed that self-other overlap (but not empathy) mediated the relationship between PT and negative obesity stereotypes. While self-other overlap and empathy both mediated the relationship between PT and positive obesity stereotypes. These findings address the importance of PT for improving positive and negative obesity stereotypes: specifically, PT promotes psychological merging, and produces empathic concern (EC).

Introduction

Obese people are severely stigmatized because of their weight. An intensive review by Puhl and Heuer (2009) shows that they confront prejudice and discrimination in many forms. In educational settings, obese students are less likely than normal-weight students to obtain a college degree ( Fowler-Brown et al., 2010 ) or be accepted as graduate students after an interview ( Burmeister et al., 2013 ). As regards interpersonal relationships, obese individuals tend to have poor relationships with their peers in school ( Puhl and Latner, 2007 ) and have fewer close friends relative to thinner individuals ( Sarlio-Lähteenkorva, 2001 ). Further, in employment settings, obese applicants are sometimes not hired because of discrimination based on their weight ( Puhl et al., 2008 ). Individuals experiencing the stigma of obesity are vulnerable to psychological disorders such as depression, low self-esteem, and anxiety ( Puhl and King, 2013 ). This stigma derives partly from negative stereotypes ( Tiggemann and Anesbury, 2000 ) that obese people are lazy, unintelligent, and lacking in self-discipline and willpower ( Puhl and Heuer, 2009 ). Although there is a lot of evidence about the adverse consequences of the stigma of obesity, relatively few studies have explored strategies to reduce obesity stereotypes and prejudices ( Gloor and Puhl, 2016 ). It is, therefore, necessary to take measures to improve attitudes toward this group.

Perspective Taking (PT) and Stereotypes

Corrigan and O'Shaughnessy (2007) propose three main avenues to change stereotypes and stigma, namely protest, education, and contact. However, the protest may provoke rebound effects, arouse resistance, and ultimately fail to induce more positive attitudes ( Corrigan et al., 2001 ). Furthermore, the magnitude and duration of education to improve attitudes may be restricted ( Corrigan et al., 2002 ). For contact to be effective, some optimal conditions are required, such as shared goals and cooperation ( Pettigrew and Tropp, 2006 ). Different from these aforementioned approaches (e.g., PT will not cause the rebound effects), PT has become an effective stereotype-improvement strategy ( Galinsky, 2002 ; Todd and Galinsky, 2014 ; Sun et al., 2016 ; Wang et al., 2018 ; Huang et al., 2020 ) because of its unique advantages. Specifically, its positive effect can be generalized from specific individuals to the groups they belong to Shih et al. (2009) for a relatively long time ( Batson et al., 1997 ) at both the explicit and implicit levels ( Todd and Burgmer, 2013 ). The limited existing work applied this strategy to anti-fat bias found that taking the perspective of obese persons who experienced discrimination did produce reduced implicit bias among overweight participants ( Teachman et al., 2003 ). There are two main theoretical hypotheses to explain the mechanisms underlying PT.

PT, Empathy, and Stereotypes

The first is the empathy-altruism hypothesis ( Batson et al., 1997 ), focused on the emotional level, which holds that taking the perspective of a member of a stigmatized group will increase the empathic feelings of an individual, such as sympathy and compassion for that individual. These feelings will evoke altruistic motivation and generalize to the whole stigmatized group, thus increasing the positive evaluation and attitude of an individual toward the group. The theory that PT indirectly reduces stereotyping through the mediating effect of empathy has been tested in many groups, such as people with AIDS ( Li, 2017 ), drug addicts ( Batson et al., 2002 ), African Americans ( Vescio et al., 2003 ), homosexuals ( Wang, 2018 ), and the elderly ( Bian, 2015 ). However, few studies have applied this method to attempt to tackle obesity stereotyping. As far as the author knows, only Cheng and Zhang (2017) have examined the direct impact of PT on implicit obesity stereotypes in China; they found significant attenuation of stereotyping but did not explore the underlying mechanism. To address this deficiency, the present study draws on the empathy-altruism hypothesis to test the mediating role of empathy between PT and obesity stereotypes. Another limitation in the literature is that many studies have shown the role of PT in reducing negative stereotypes ( Galinsky and Moskowitz, 2000 ; Ku et al., 2010 ; Todd et al., 2011 ) but few have considered positive stereotypes ( Wang et al., 2014 ). Obesity stereotypes include not only negative qualities but also positive characteristics, such as warmth and friendliness ( Tiggemann and Rothblum, 1988 ). Does PT weaken or enhance positive obesity stereotypes? The current study will answer this question.

PT, Self-Other Overlap, and Stereotypes

The second explanation mechanism is the self-other overlap hypothesis ( Davis et al., 1996 ; Galinsky and Moskowitz, 2000 ), focused on the cognitive level, which holds that PT can activate self-concept and lead perspective takers to attribute a greater proportion of their self-traits to the other. With perspective takers perceiving that they share more common characteristics with the target, they merge their mental representations of self and others, which changes their evaluation of the target group. Galinsky and Ku (2004) indirectly tested the self-other overlap hypothesis by examining the moderating role of self-esteem on the effect of PT on prejudice toward the elderly. They reasoned that because perspective takers change their attitude by applying the self to the target, the positive self will be activated and applied to the target group when the perspective takers have high self-esteem, thereby improving their attitude toward target group members; conversely, when perspective takers feel negative about themselves, there is no reduction in prejudice against the target group. As expected, Galinsky and Ku (2004) found that perspective takers with high self-esteem evaluated the elderly more positively than did those with low self-esteem. However, the studies of Bian (2015) , Li (2017) , and Wang (2018) , did not produce this result. The three researchers suggested that the inconsistent findings may be caused by a cultural difference in self-esteem between East and West. Todd et al. (2012) found that automatic self–Black associations, measured by IAT, mediated the effect of PT on perceptions of racial discrimination. Additionally, there are multiple measures to assess self–other overlap, such as Adjective Checklist Overlap, Absolute Difference in Attribute Ratings, and the Inclusion of Others in Self Scale (IOS; Aron et al., 1992 ). Myers and Hodges (2012) comprehensively analyzed these measures and identified perceived closeness (e.g., IOS) as the most effective way to measure the quality of the relationship between two people. For the above reasons, the present study does not take the indirect approaches but, instead, uses the IOS to directly measure self-other overlap. The aim is to test whether the influence of PT on obesity stereotypes is realized through the mediating effect of self-other overlap.

In summary, based on the empathy-altruism hypothesis and self-other overlap hypothesis, this study investigates the impact of PT on positive and negative obesity stereotypes and examines the underlying mechanism of this relationship, namely the mediating effects of empathy, and self-other overlap.

Participants

The participants were 687 undergraduates recruited from three universities in Hebei, Shandong, and Jiangxi Province, China, comprising 191 males and 496 females. The average age of participants was 19.91 years (SD = 1.14, age-range = 17~24). Among the participants, 151 students majored in Chinese language and literature, 378 students majored in pharmacy, and 158 students majored in education. Six hundred forty eight students were Han and the rest were ethnic minorities. In terms of self-reported body weight, 141 participants were underweight, 389 participants were moderate, and 157 participants were overweight.

A teacher from each University conducted the questionnaire survey in class. The teachers first explained to the students their rights as participants, including the option to withdraw and assured them that their anonymity and the confidentiality of their responses were guaranteed. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants; for underage participants, consent was obtained from parents. Teachers then distributed the questionnaire to participants, who were seated separately and not permitted to interact with one another while completing the questionnaire. Each participant received a small reward for their contribution to the study.

PT and Empathy

Following Wang et al. (2014) , this study used the PT and empathic concern (EC) subscales of the Chinese version of Zhan (1986) of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index ( Davis, 1980 ) to respectively measure the PT and empathy tendency of students. The PT subscale contains five items, such as “I sometimes try to understand my friends better by imagining how things look from their perspective”; the EC subscale includes six items, such as “I often have tender, concerned feelings for people less fortunate than me.” All items are measured using a 5-point Likert scale of agreement, with response options ranging from 0 (“does not describe me well”) to 4 (“describes me very well”). Cronbach's alphas for each subscale were α PT = 0.84, α EC = 0.52, consistent with the previous study (e.g., Zhang et al., 2010 ).

Self-Other Overlap

Self-other overlap was measured by the IOS. The scale comprises seven pairs of circles with an increasing degree of overlap. One circle represents the self and the other represents obese group members. Participants were asked to select which pair of circles best described their relationship with the obesity group. The scale is scored from 1 (no overlap) to 7 (nearly complete overlap). The higher the overlapping degree of circles, the greater the self-other overlap.

Obesity Stereotypes

Obesity stereotypes were selected from the studies of Vartanian et al. (2015) and Cheng (2017) . Specifically, this study included five negative stereotypes (lazy, sloppy, self-indulgent, lacking in self-discipline, and clumsy) and five positive stereotypes (kind, warm, optimistic, simple and honest, and generous). Participants were asked to rate the extent to which each stereotype fitted the characteristics of obese people. The response options ranged from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. Cronbach's alphas for the overall scale and each subscale were α overall = 0.77, α positivestereotypes = 0.84, and α negativestereotypes = 0.90.

Analytic Strategy

Descriptive statistics were performed using SPSS 22. The hypothesized relationships were tested through a series of structural equation models and the bootstrap method in AMOS. Studies using structural equation modeling usually set several thresholds for goodness-of-fit indexes, such as root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) ≤ 0.08 ( Williams et al., 2009 ), CFI ≥ 0.90, and 2 ≤ χ 2 /df ≤ 5 ( Hair et al., 2010 ). Before the data analysis, all variables were standardized. The items of PT, empathy, self-other overlap, and obesity stereotypes were used as analysis indicators. Self-other overlap was considered as a manifest variable, while PT, empathy, and obesity stereotypes were considered as latent variables.

Control for Common Method Bias

Through precautions such as protecting anonymity and using various response formats (5- and 7-point scales), the data collection process was designed to minimize the common method bias of data obtained from the self-report questionnaire. Following data collection, Harman's single-factor test ( Podsakoff et al., 2003 ) was conducted to control for common method bias. The results revealed five factors with eigenvalues >1, of which the first factor accounted for 20.16% of the total variance (below the critical standard of 40%). Therefore, common method bias was not a significant problem in this study.

Descriptive Statistics

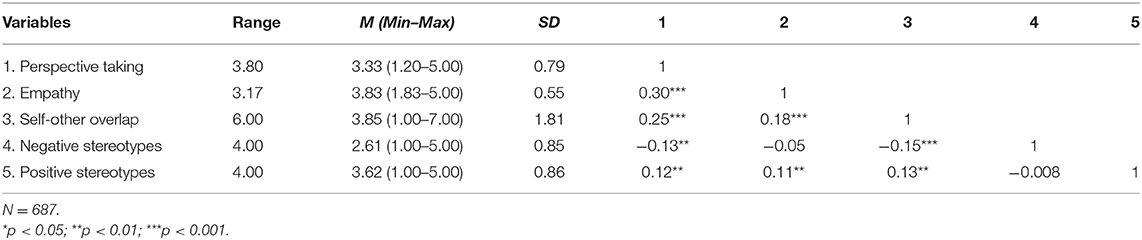

The ranges, means, SDs, and correlations of the research variables are reported in Table 1 . All the variables were significantly correlated, except empathy–negative stereotypes and negative–positive stereotypes. In addition, the age and gender of participants were not significantly correlated with either dependent variable [negative ( r age < −0.01, p = 0.95; r gender = 0.05, p = 0.20] and positive ( r age = 0.04, p = 0.25; r gender <0.01, p = 0.99) obesity stereotypes; for simplicity, these results are not presented in the Table. The body weight of participants was significantly correlated with the positive obesity stereotypes ( r = 0.10, p < 0.05), so body weight was controlled for in the subsequent analysis.

Table 1 . Descriptive statistics of the sample.

Analysis of Mediating Effect

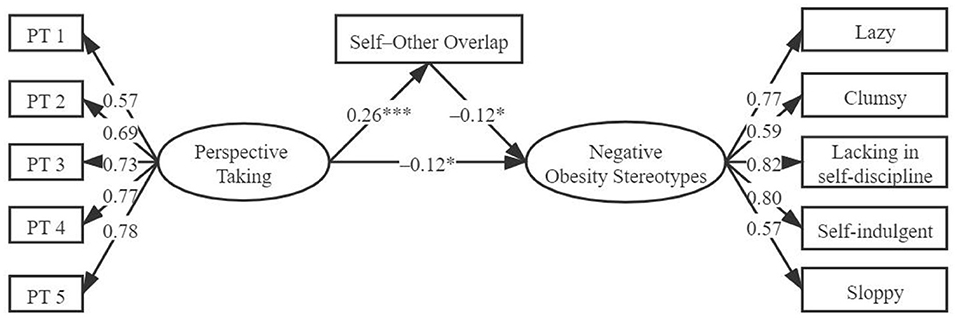

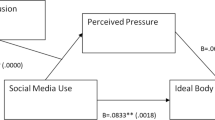

First, the influence of PT on the negative obesity stereotypes and the mediating mechanism of this relationship were examined. Step 1 tested the direct effect of PT on negative obesity stereotypes. The results showed that the direct path was significant (β = −0.15, p < 0.001) but the model fit was poor (RMSEA = 0.10, χ 2 / df = 7.95). Step 2 then assessed the mediating role of empathy between PT and negative obesity stereotypes. As reported above, the correlation between empathy and negative obesity stereotypes was not significant, meaning that PT could not affect the negative obesity stereotypes through the mediating role of empathy. The mediation model analysis also supported this result: Although the indirect path from PT to empathy was significant (β = 0.59, p < 0.001), the indirect path from empathy to negative obesity stereotypes did not reach statistical significance (β = 0.001, p > 0.05). Next, step 3 examined the mediating role of self-other overlap in the effect of PT on negative obesity stereotypes. Model analysis showed that each path reached a significant level (as shown in Figure 1 ) and the model fitted well (RMSEA = 0.07, goodness of fit index (GFI) = 0.96, incremental fit index (IFI) = 0.95, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.95, tucker-lewis index (TLI) = 0.94, chi-square/degree of freedom (the minimum discrepancy divided by degrees of freedom) χ 2 / df = 4.23). The mediating effect was tested by the bootstrap method. The results showed that the mediating effect of self-other overlap was significant with an indirect effect of 0.03 and a 95% confidence interval (CI) of [−0.06, −0.01]. Then pwrSEM was used to conduct a power analysis ( Wang and Rhemtulla, 2021 ). Results suggested that the study had 0.81 power to detect an indirect effect of 0.03 in the model. The above results indicate that PT has a negative effect on negative obesity stereotypes through the mediating effect of self-other overlap. However, empathy appears not to play a mediating role.

Figure 1 . The mediating role of self-other overlap between perspective taking and negative obesity stereotypes. * p < 0.05; *** p < 0.001.

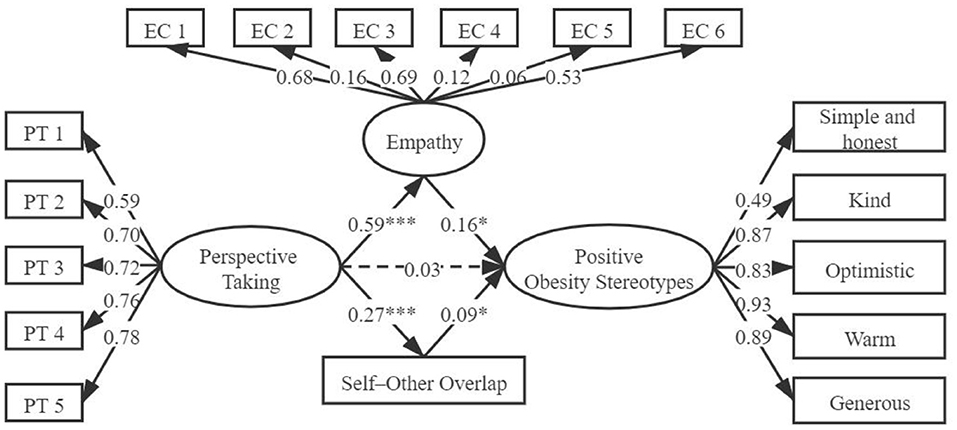

Second, the influence of PT on positive obesity stereotypes and the mediating mechanism of this relationship were examined. The body weight of participants was treated as a control variable because it was identified earlier as being significantly correlated with positive obesity stereotypes. Step 1 tested the direct effect of PT on positive obesity stereotypes. The results indicated that the direct path was significant (β = 0.15, p < 0.001) and the model fitted well (RMSEA = 0.07, GFI = 0.95, IFI = 0.96, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.95, χ 2 / df = 4.22). Step 2 then assessed the mediating role of empathy between PT and positive obesity stereotypes. The model analysis showed that after adding the mediating variable empathy, the direct path from PT to positive obesity stereotypes became insignificant, while the indirect path from PT to empathy (β = 0.59, p < 0.001) and from empathy to positive obesity stereotypes (β = 0.17, p = 0.01) reached a significant level. The model fit indexes were RMSEA = 0.07, GFI = 0.92, IFI = 0.91, CFI = 0.91, χ 2 / df = 4.49, suggesting that the mediating model acceptably fitted the data. The mediating effect was (0.59 × 0.17)/0.15 = 0.67.

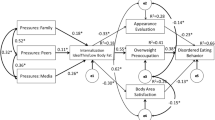

Next, step 3 assessed the mediating role of self-other overlap between PT and positive obesity stereotypes. The results showed that after adding the mediating variable self-other overlap, the direct path from PT to positive obesity stereotypes (β = 0.13, p < 0.01) and the indirect path from PT to self-other overlap (β = 0.26, p < 0.001) and from self-other overlap to positive obesity stereotypes (β = 0.10, p < 0.05) were all significant. The measurement model showed acceptable fit: RMSEA = 0.06, GFI = 0.95, IFI = 0.96, CFI = 0.96, χ 2 / df = 3.80. The mediating effect was (0.26 × 0.10)/0.15 = 0.17. In step 4, the mediating variables empathy and self-other overlap were combined to construct and test an integrated mediating model. The bootstrap method was used to test multiple mediating effects ( Lau and Cheung, 2012 ). Model analysis indicated that the direct path from PT to positive obesity stereotypes became insignificant when the two mediating variables were added simultaneously. The direct effect was 0.03 and the 95% CI (−0.10, 0.16) contained zero. All the other paths were significant: from PT to empathy [CI: (0.51, 0.67)], from empathy to positive obesity stereotypes [CI: (0.02, 0.31)], from PT to self-other overlap [CI: (0.19, 0.35)], from self-other overlap to positive obesity stereotypes [CI: (0.01, 0.310)]. Finally, a dual mediating model was obtained, with an indirect effect of 0.12, a 95% CI of (0.04, 0.22), and good model fit to the data (as shown in Figure 2 , which excludes the control variable for simplicity; RMSEA = 0.07, GFI = 0.92, IFI = 0.91, CFI = 0.91, TLI = 0.90, χ 2 / df = 4.16). Then pwrSEM was used to run a power analysis ( Wang and Rhemtulla, 2021 ). Results suggested that the study had 0.85 power to detect an indirect effect of 0.12 in the model. These results suggest that self–other overlap and empathy both play a mediating role between PT and positive obesity stereotypes.

Figure 2 . The mediating role of empathy and self-other overlap between perspective taking and positive obesity stereotypes (The dotted line means that the path is not significant). * p < 0.05; *** p < 0.001.

This research aimed to discover the influence of PT on positive and negative obesity stereotypes among University students. Based on the self-other overlap hypothesis (cognitive level) and empathy-altruism hypothesis (emotional level), this study tested the mediating role of self-other overlap and empathy in the relationship between PT and obesity stereotypes. The results will be discussed in detail below.

First, analysis of the mechanism through which PT influences negative obesity stereotypes revealed that self-other overlap, but not empathy, played a mediating role. Although PT can predict empathy, empathy did not significantly affect negative obesity stereotypes. This is consistent with the findings of previous studies that empathy cannot effectively reduce obesity prejudice ( Teachman et al., 2003 ; Gapinski et al., 2006 ). In this regard, studies suggest that empathy inadvertently emphasizes or evokes the negative aspects of obesity ( Daníelsdóttir et al., 2010 ), which may offset the sympathy and compassion that empathy generates for stigmatized groups in negative evaluations. The mean score of the negative obesity stereotypes in this study was 2.61 (median = 3), indicating that the University students did not consider the negative traits to be characteristic of obese people. If this truly reflects the perception of participants about obese people, then they would feel no need to sympathize. However, the responses of participants may have been affected by social desirability bias, such that even in an anonymous context they did not report their true attitudes with respect to negative obesity stereotypes. Future research will benefit from directly measuring social desirability, to quantify and separate its impact. Another consideration is that this study used a trait tendency measurement, rather than taking a specific perspective for the obese group. This may have prevented participants from putting themselves in the position of obese people to feel the challenges they encounter. Future studies could address this limitation by using experimental methods to manipulate participants into taking the perspective of and empathizing with obese people. It would be valuable to discover whether this approach further verifies the hypotheses and results of this research. Additionally, from the perspective of the common ingroup identity model ( Gaertner et al., 1993 ), recategorizing two separate groups as one group could improve negative evaluations toward outgroup members. By promoting self-other overlapping, the attitudes of perspective takers toward former outgroup members (i.e., obese group) become more positive through processes involving pro-ingroup bias.

Second, this study found that self-other overlap and empathy both mediated the relationship between PT and positive obesity stereotypes. Individuals usually view themselves positively ( Taylor and Brown, 1988 ). Through PT that enhances the psychological merging between self and target, individuals apply the positive description of themselves to obese people, thereby enhancing positive evaluation. This is consistent with the findings of Laurent and Myers (2011) but contrary to the result of Wang et al. (2014) , who found that PT reduces the positive stereotypes of doctors through self-other overlap. These different findings may be attributed to the different contents of the stereotype: whereas the traits examined by Laurent and Myers (e.g., attractive, wholesome) and in this study (e.g., kind, warm) mainly focus on the “warmth” dimension, Wang et al. (2014) examined positive characteristics of the “competence” dimension (e.g., analytical, smart).

Although empathy did not mediate the relationship between PT and negative obesity stereotypes, this study supported the empathy-altruism hypothesis by showing that empathy played a mediating role between PT and positive obesity stereotypes. This seems to indicate the positive trait bias of the hypothesis in the obese group. In other words, empathy generates altruistic motivation to help obese people escape unfavorable situations by enlarging their positive traits. However, Gloor and Puhl (2016) found that although PT increases empathy, it also increases fat phobia. This may be related to the attitudes of participants toward obese people. The mean score of the positive obesity stereotypes in this study was 3.62 (median = 3), meaning that participants consider the positive traits to be fairly characteristic of obese people. Skorinko and Sinclair (2013) pointed out that when the characteristics of the target group are consistent with the stereotypes, PT will cause stereotyping to increase.

Finally, the shortcomings of this study must be acknowledged. Obesity stereotypes were measured through a self-report questionnaire. In some prior studies, participants who did not show explicit obesity prejudice were found to have strong implicit negative obesity stereotypes ( Teachman et al., 2003 ). Therefore, future research should use implicit measurement to test whether University students truly hold a neutral attitude toward negative obesity stereotypes. Considering the group specificity of PT, measuring individual tendency through a questionnaire may have weakened the empathy of participants toward the obese group and, consequently, their attitudes toward obesity stereotypes. Future research should, therefore, seek to verify the results of this study by using experimental methods to manipulate PT. Furthermore, the correlational method makes reverse causality an underlying issue. The application of experimental design will help to establish causal links between variables. Despite these limitations, this study makes valuable contributions to the literature by finding that self-other overlap and empathy both mediated the relationship between PT and positive obesity stereotypes among University students. Yet, for negative obesity stereotypes, self-other overlap emerged as the only mediator.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Inner Mongolia Normal University. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants and underage participants' parents.

Author Contributions

YW conceived the original idea, organized the data collection, performed the statistical analyses, and drafted the manuscript. YZ critically revised the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.643708/full#supplementary-material

Aron, A., Aron, E. N., and Smollan, D. (1992). Inclusion of other in the self scale and the structure of interpersonal closeness. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 63, 596–612. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.63.4.596

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Batson, C. D., Chang, J., Orr, R., and Rowland, J. (2002). Empathy, attitudes, and action: can feeling for a member of a stigmatized group motivate one to help the group. Pers. Soc. Psychol Bull. 28, 1656–1666. doi: 10.1177/014616702237647

Batson, C. D., Polycarpou, M. P., Harmon-Jones, E., Imhoff, H. J., Mitchener, E. C., Bednar, L. L., et al. (1997). Empathy and attitudes: can feeling for a member of a stigmatized group improve feelings toward the group? J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 72, 105–118. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.72.1.105

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bian, N. (2015). The effect of perspective taking on the college students' elderly stereotype . [master's thesis]. Wuhan, Hubei: Central China Normal University.

Burmeister, J. M., Kiefner, A. E., Carels, R. A., and Musher-Eizenman, D. R. (2013). Weight bias in graduate school admissions. Obesity 21, 918–920. doi: 10.1002/oby.20171

Cheng, L. (2017). A study on the influence of obese body shape stereotype to employment intention . [master's thesis]. Hohhot, Inner Mongolia: Inner Mongolia Normal University.

Cheng, L., and Zhang, Y. Z. (2017). Research on the influence of perspective taking on implicit obesity stereotype. J. Inner Mongo. Norm. Univ. 30, 73–77. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1671-0916.2017.02.012

Corrigan, P. W., David, R., Amy, G., Robert, L., Philip, R., Kyle, U. W., et al. (2002). Challenging two mental illness stigmas: personal responsibility and dangerousness. Schizophr. Bull. 28, 293–309. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006939

Corrigan, P. W., and O'Shaughnessy, J. R. (2007). Changing mental illness stigma as it exists in the real world. Aust. Psychol. 42, 90–97. doi: 10.1080/00050060701280573

Corrigan, P. W., River, L., Lundin, R. K., Penn, D. L., Uphoff-Wasowski, K., Campion, J., et al. (2001). Three strategies for changing attributions about severe mental illness. Schizophr. Bull. 27, 187–195. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006865

Daníelsdóttir, S., O'Brien, K. S., and Ciao, A. (2010). Anti-fat prejudice reduction: a review of published studies. Obes. Facts 3, 47–58. doi: 10.1159/000277067

Davis, M. H. (1980). A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. JSAS Cat. Sel. Doc. Psychol. 10:85.

Davis, M. H., Conklin, L., Smith, A., and Luce, C. (1996). Effect of perspective taking on the cognitive representation of persons: a merging of self and other. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 70, 713–726. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.70.4.713

Fowler-Brown, A. G., Ngo, L. H., Phillips, R. S., and Wee, C. C. (2010). Adolescent obesity and future college degree attainment. Obesity 18, 1235–1241. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.463

Gaertner, S. L., Dovidio, J. F., Anastasio, P. A., and Bachman, B. A. (1993). The common ingroup identity model: Recategorization and the reduction of intergroup bias. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 4, 1–26. doi: 10.1080/14792779343000004

Galinsky, A. D. (2002). “Creating and reducing intergroup conflict: the role of perspective-taking in affecting out-group evaluations,” in Toward Phenomenology of Groups and Group Membership , ed. H. Sondak (New York, NY: Elsevier), 85–113. doi: 10.1016/S1534-0856(02)04005-7

Galinsky, A. D., and Ku, G. (2004). The effects of perspective-taking on prejudice: The moderating role of self-evaluation. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 30, 594–604. doi: 10.1177/0146167203262802

Galinsky, A. D., and Moskowitz, G. B. (2000). Perspective-taking: decreasing stereotype expression, stereotype accessibility, and in-group favoritism. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 78, 708–724. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.78.4.708

Gapinski, K. D., Schwartz, M. B., and Brownell, K. D. (2006). Can television change anti-fat attitudes and behavior? J. Appl. Biobehav. Res. 11, 1–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9861.2006.tb00017.x

Gloor, J. L., and Puhl, R. M. (2016). Empathy and perspective-taking: examination and comparison of strategies to reduce weight stigma. Stigma Health 1, 269–279. doi: 10.1037/sah0000030

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., and Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th Edn. New York, NY: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Google Scholar

Huang, Q., Peng, W., and Simmons, J. V. (2020). Assessing the evidence of perspective taking on stereotyping and negative evaluations: a p-curve analysis. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. doi: 10.1177/1368430220957081. [Epub ahead of print].

Ku, G., Wang, C. S., and Galinsky, A. D. (2010). Perception through a perspective-taking lens: differential effects on judgment and behavior. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 46, 792–798. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2010.04.001

Lau, R. S., and Cheung, G. W. (2012). Estimating and comparing specific mediation effects in complex latent variable models. Organ. Res. Methods 15, 3–16. doi: 10.1177/1094428110391673

Laurent, S. M., and Myers, M. W. (2011). I know you're me, but who am I? Perspective taking and seeing the other in the self. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 47, 1316–1319. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2011.05.018

Li, P. F. (2017). A study of the impact ofPT on the college students' HIV/AIDS Prejudice . [master's thesis]. (Chengdu, Sichuan): Sichuan Normal University.

Myers, M. W., and Hodges, S. D. (2012). The structure of self-other overlap and its relationship to perspective taking. Pers. Relat. 19, 663–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2011.01382.x

Pettigrew, T. F., and Tropp, L. R. (2006). A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 90, 751–783. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.751

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Puhl, R. M., Andreyeva, T., and Brownell, K. D. (2008). Perceptions of weight discrimination: prevalence and comparison to race and gender discrimination in America. Int. J. Obes. 32, 992–1000. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.22

Puhl, R. M., and Heuer, C. A. (2009). The stigma of obesity: a review and update. Obesity 17, 941–964. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.636

Puhl, R. M., and King, K. M. (2013). Weight discrimination and bullying. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 27, 117–127. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2012.12.002

Puhl, R. M., and Latner, J. D. (2007). Stigma, obesity, and the health of the nation's children. Psychol. Bull. 133, 557–580. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.557

Sarlio-Lähteenkorva, S. (2001). Weight loss and quality of life among obese people. Soc. Indic. Res. 54, 329–354. doi: 10.1023/A:1010939602686

Shih, M., Wang, E., Trahan Bucher, A., and Stotzer, R. (2009). Perspective taking: reducing prejudice towards general outgroups and specific individuals. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 12, 565–577. doi: 10.1177/1368430209337463

Skorinko, J. L., and Sinclair, S. A. (2013). Perspective taking can increase stereotyping: the role of apparent stereotype confirmation. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 49, 10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2012.07.009

Sun, S., Zuo, B., Wu, Y., and Wen, F. (2016). Does perspective taking increase or decrease stereotyping? The role of need for cognitive closure. Pers. Individ. Differ. 94, 21–25. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.01.001

Taylor, S. E., and Brown, J. (1988). Illusion and well-being: a social psychological perspective on mental health. Psychol. Bull. 103, 193–210. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.103.2.193

Teachman, B. A., Gapinski, K. D., Brownell, K. D., Rawlins, M., and Jeyaram, S. (2003). Demonstrations of implicit anti-fat bias: the impact of providing causal information and evoking empathy. Health Psychol. 22, 68–78. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.1.68

Tiggemann, M., and Anesbury, T. (2000). Negative stereotyping of obesity in children: the role of controllability beliefs. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 30, 1977–1993. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2000.tb02477.x

Tiggemann, M., and Rothblum, E. D. (1988). Gender difference in social consequences of perceived overweight in the United States and Australia. Sex Roles 18, 75–86. doi: 10.1007/BF00288018

Todd, A. R., Bodenhausen, G. V., and Galinsky, A. D. (2012). Perspective taking combats the denial of intergroup discrimination. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 48, 738–745. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2011.12.011

Todd, A. R., Bodenhausen, G. V., Richeson, J. A., and Galinsky, A. D. (2011). Perspective taking combats automatic expressions of racial bias. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 100, 1027–1042. doi: 10.1037/a0022308

Todd, A. R., and Burgmer, P. (2013). Perspective taking and automatic intergroup evaluation change: testing an associative self-anchoring account. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 104, 786–802. doi: 10.1037/a0031999

Todd, A. R., and Galinsky, A. D. (2014). Perspective-taking as a strategy for improving intergroup relations: evidence, mechanisms, and qualifications. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass 8, 374–387. doi: 10.1111/spc3.12116

Vartanian, L. R., Trewartha, T., and Vanman, E. J. (2015). Disgust predicts prejudice and discrimination toward individuals with obesity. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 46, 369–375. doi: 10.1111/jasp.12370

Vescio, T. K., Sechrist, G. B., and Paolucci, M. P. (2003). Perspective taking and prejudice reduction: the mediational role of empathy arousal and situational attributions. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 33, 455–472. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.163

Wang, C. S., Ku, G., Tai, K., and Galinsky, A. D. (2014). Stupid doctors and smart construction workers:PT reduces stereotyping of both negative and positive targets. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 5, 430–436. doi: 10.1177/1948550613504968

Wang, C. S., Lee, M., Ku, G., and Leung, A. K. (2018). The cultural boundaries of Perspective-taking: when and why Perspective-taking reduces stereotyping. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 44, 928–943. doi: 10.1177/0146167218757453

Wang, L. L. (2018). A study on the influence of perspective taking on homosexual stigma among the college students . [master's thesis]. [Chengdu, Sichuan]: Sichuan Normal University.

Wang, Y. A., and Rhemtulla, M. (2021). Power analysis for parameter estimation in structural equation modeling: a discussion and tutorial. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 4, 1–17. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/pj67b

Williams, L. J., Vandenberg, R. J., and Edwards, J. R. (2009). 12 structural equation modeling in management research: a guide for improved analysis. Acad. Manag. Ann. 3, 543–604. doi: 10.5465/19416520903065683

Zhan, Z. Y. (1986). The relationship between grade, sex-role, human relationship orientation and empathy . [master's thesis]. [Taipei, Taiwan]: National Chengchi University.

Zhang, F. F., Dong, Y., Wang, K., Zhan, Z. Y., and Xie, L. F. (2010). Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the interpersonal reactivity index-C. Chi. J. Clin. Psychol. 18, 25–27. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2010.02.019

Keywords: obesity stereotypes, perspective taking, empathy, self-other overlap, dual mediating effects

Citation: Wu Y and Zhang Y (2021) The Impact of Perspective Taking on Obesity Stereotypes: The Dual Mediating Effects of Self-Other Overlap and Empathy. Front. Psychol. 12:643708. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.643708

Received: 18 December 2020; Accepted: 12 July 2021; Published: 12 August 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Wu and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yuzhu Zhang, nsdzyz@163.com

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Impact of Perspective Taking on Obesity Stereotypes: The Dual Mediating Effects of Self-Other Overlap and Empathy

Affiliation.

- 1 School of Psychology, Inner Mongolia Normal University, Hohhot, China.

- PMID: 34456781

- PMCID: PMC8387714

- DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.643708

Previous studies have indicated that obese people face many forms of severe prejudice and discrimination in various settings, such as education, employment, and interpersonal relationships. However, research aimed at reducing obesity stereotyping is relatively rare, and prior studies have focused primarily on negative stereotypes. Based on the empathy-altruism hypothesis and self-other overlap hypothesis, this study investigates the impact of perspective taking (PT) on both positive and negative obesity stereotypes and examines the mediating effects of empathy and self-other overlap. A sample of 687 students (191 males and 496 females) at Chinese universities participated by completing self-report questionnaires on trait tendency and evaluation toward obese people. Structural equation modeling and the bootstrap method revealed that self-other overlap (but not empathy) mediated the relationship between PT and negative obesity stereotypes. While self-other overlap and empathy both mediated the relationship between PT and positive obesity stereotypes. These findings address the importance of PT for improving positive and negative obesity stereotypes: specifically, PT promotes psychological merging, and produces empathic concern (EC).

Keywords: dual mediating effects; empathy; obesity stereotypes; perspective taking; self-other overlap.

Copyright © 2021 Wu and Zhang.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 20 December 2021

Behavior, Psychology and Sociology

Weight-based stereotype threat in the workplace: consequences for employees with overweight or obesity

- Hannes Zacher ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6336-2947 1 &

- Courtney von Hippel 2

International Journal of Obesity volume 46 , pages 767–773 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

9170 Accesses

4 Citations

6 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Patient education

Background/Objectives

Employees with overweight or obesity are often stereotyped as lazy, unmotivated, and less competent than employees with normal weight. As a consequence, employees with overweight or obesity are susceptible to stereotype threat, or the concern about confirming, or being reduced to, a stereotype about their group. This survey study examined whether employees with overweight or obesity experience stereotype threat in the workplace, whether it is associated with their perceived ability to meet their work demands (i.e., work ability), and whether high levels of knowledge about one’s self (i.e., authentic self-awareness) can offset a potential negative association.

Subjects/Methods

Using a correlational study design, survey data were collected from N = 758 full-time employees at three measurement points across 3 months. Employees’ average body mass index (BMI) was 26.36 kg/m² (SD = 5.45); 34% of participants were employees with overweight (BMI between 25 and <30), and 18% of participants were employees with obesity (BMI > 30).

Employees with higher weight and higher BMI reported more weight-based stereotype threat ( r s between 0.17 and 0.19, p < 0.001). Employees who experienced higher levels of weight-based stereotype threat reported lower work ability, while controlling for weight, height, and subjective weight ( β = −0.27, p < 0.001). Authentic self-awareness moderated the relationship between weight-based stereotype threat and work ability ( β = 0.14, p < 0.001), such that the relationship between stereotype threat and work ability was negative among employees with low authentic self-awareness ( β = −0.25, p < 0.001), and non-significant among employees with high authentic self-awareness ( β = 0.08, p = 0.315).

Conclusions

The findings of this study contribute to the literature by showing that weight-based stereotype threat is negatively associated with employees’ perceived ability to meet their work demands, particularly among those employees with low authentic self-awareness.

Similar content being viewed by others

A qualitative exploration of individual differences in wellbeing for highly sensitive individuals

Becky A. Black & Margaret L. Kern

Weight biases, body image and obesity risk knowledge in the groups of nursing students from Poland and Nigeria

Wojciech Styk, Marzena Samardakiewicz & Szymon Zmorzynski

Sport–gender stereotypes and their impact on impression evaluations

Zhiyuan Liu, Menglu Shentu, … Weiqi Zheng

People with overweight or obesity face prejudice and discrimination in various aspects of their lives, such as healthcare, education, and interpersonal relationships [ 1 ]. Unfortunately, the employment context is no exception. Employees with overweight or obesity are stereotyped to lack self-discipline, self-control, and willpower [ 2 , 3 ], and are seen as less competent and conscientious [ 4 ]. In light of these stereotypes, it is not surprising that cross-sectional surveys, population-based research, and experimental studies demonstrate that people with overweight or obesity experience bias with regard to a variety of workplace outcomes [ 1 ]. For example, compared to people with normal weight, people with overweight or obesity are less likely to be hired [ 5 , 6 ], receive lower pay [ 7 ], and are less likely to receive promotions [ 8 ]. Employees with overweight or obesity also report being the subject of derogatory comments and other uncivil behaviors from their supervisors and co-workers [ 9 ]. In short, employees with overweight or obesity are stigmatized and discriminated against in the workplace [ 1 ], raising the clear possibility that these employees will be susceptible to stereotype threat.

According to stereotype threat theory [ 10 ], concerns about being stereotyped based on one’s group membership can lead people to psychologically distance themselves from domain-relevant activities and performance. That is, stereotype threat can lead to disidentification—or disengagement—from the task domain. Although the majority of stereotype threat research has taken place in a laboratory setting [ 11 ], a growing body of research demonstrates that stereotype threat is also important in the workplace [ 12 , 13 ]. Research in organizational contexts demonstrates that stigmatized groups (e.g., older employees; women in male-dominated fields) disengage from work when they experience stereotype threat [ 12 , 14 ]. Given the growing percentage of people with overweight or obesity worldwide [ 15 ], it is important to examine whether employees with overweight or obesity experience stereotype threat in the workplace, whether it is associated with their perceived ability to meet their work demands, and whether other psychological factors can offset a potential negative association.

Although the stereotypes about employees with overweight or obesity are varied, many focus on the notion that they are less capable [ 4 ]. Over time, people from stereotyped groups can internalize the stigma about their group [ 16 ]. If employees with overweight or obesity internalize the stigma that they are less capable at work than their colleagues with normal weight, then feelings of stereotype threat should lead to lowered perceptions of work ability, or the perceived capacity to continue working in their current job given their perceptions of their physical, cognitive, and interpersonal job demands and their ability to meet these demands [ 17 , 18 ]. In short, employees’ experience of weight-based stereotype threat should lead them to believe they are less capable of meeting the demands of their job.

The moderating role of authentic self-awareness

Scholarly interest in employee authenticity, or “being your true self at work,” has rapidly increased over the past few years [ 19 ]. Authentic self-awareness is the extent of knowledge (and trust in that knowledge) about various aspects of one’s self and the motivation to expand that knowledge [ 20 ]. Employees with high levels of authentic self-awareness consider their self as a whole (e.g., physical appearance, internal states including cognitions and emotions, motives and intentions, social commitments) and are invested in understanding and learning more about their “true self” [ 21 ]. Research has shown that employees’ authentic self-awareness is empirically distinct from, but moderately and positively associated with self-insight (i.e., clarity of understanding various aspects of one’s self), self-acceptance (i.e., positive attitude to one’s self), and self-esteem (i.e., confidence in one’s own worth), and negatively associated with anxiety, cognitive and emotional strain, and ill-health [ 21 ].

We predict that weight-based stereotype threat generally is negatively related to work ability, but that high (vs. low) levels of authentic self-awareness may buffer this negative association. This prediction is based on theorizing that employees who better understand themselves are less likely to comply with unwanted social and situational pressures in their work environment and react less strongly to others’ demands and workplace stressors [ 21 ]. Thus, authentic self-awareness may constitute a coping mechanism that helps employees deal with the stressor of weight-based stereotype threat [ 22 , 23 ]. Consistent with this possibility, experimental work has shown that people who have a more stable sense of self—a trait that is associated with greater self-concept clarity [ 24 ] and greater integration of positive and negative information [ 25 ]—are more likely to treat negative feedback as a challenge rather than a hindrance [ 26 ]. Clarity and stability of the self-concept, as well as integration of positive and negative information into the self-concept, are all important components of authentic self-awareness [ 20 , 27 ].

Additionally, employees who possess a holistic and differentiated understanding of their self and who are motivated to continuously improve their self-understanding should have a broader and more effective set of psychological coping strategies (e.g., positive reframing, reappraisal) at their disposal when they feel stereotyped [ 28 , 29 ]. That is, when faced with weight-based stereotype threat, they should be more capable of restoring a sense of themselves as capable employees through consideration of numerous other aspects of their self-concept. In contrast, employees with low authentic self-awareness do not adopt a broad perspective on their self and are less interested in learning more about its elements. With less self-knowledge at their disposal, these employees should be more susceptible to the negative effects of weight-based stereotype threat. Consistent with this possibility, inauthenticity has been hypothesized to result in employees who are more likely to comply with stereotypes [ 30 ]. Thus, employees’ authentic self-awareness should moderate the negative relationship between weight-based stereotype threat and work ability, such that weight-based stereotype threat is associated with greater deficits in work ability when authentic self-awareness is low than when authentic self-awareness is high.

Participants and procedure

We conducted a correlational survey study with three measurement points over a period of 3 months, incorporating an initial survey with demographic and control variables (Time [T] 1) as well as two subsequent surveys (T2 and T3) that included measures of weight-based stereotype threat, work ability, and authentic self-awareness. We used a time lag of four weeks between measurement points in an effort to ensure that participants could recall their concerns and experiences at work. Data for this study were collected as part of a larger data collection effort, and so far two other studies based on the same dataset, but with completely different research questions and completely different substantive variables, have been published [ 31 , 32 ]. In Germany, correlational studies are exempt from institutional review board approval. The research was conducted in line with the ethical guidelines and requirements of the German Psychological Society. Participation in the study was voluntary and anonymous, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

We commissioned a professional and ISO 26362 certified panel provider to recruit participants from a nationally representative online panel in Germany. To be eligible for inclusion, participants had to be at least 18 years old and working full-time. Approximately 3500 participants were initially contacted with a request to participate in the first measurement wave (T1). This number of initial participants was determined based on the panel provider’s recommendations to obtain a final sample size of 750 participants or more at T3, which is sufficient to detect small correlational effect sizes (i.e., r ≥ 0.10) with high (i.e., ≥0.80) statistical power [ 33 ]. Of those 3500 contacted, 1522 responded and were eligible to participate according to our selected inclusion criteria. Of these 1522 who qualified, 758 consented to participate and provided complete data on all three measurement occasions.

The sample was comprised of 438 (57.8%) men and 320 women (42.2%). Participants’ age ranged from 21 to 74 years with a mean age of 43.83 years (SD = 10.70). Most participants held either a lower-secondary school degree (228; 30.1%), a higher-secondary school degree (137; 18.1%), or a college/university degree (241; 31.8%). Participants worked across 21 different industries, with the public administrative sector (12.7%), manufacturing (12.8%), and healthcare (10.3%) most represented.

Overall, body mass index (BMI) values of participants at T1 ranged from 16.71 to 60.22, with an average BMI of 26.36 kg/m² (SD = 5.45). More specifically, only 17 participants (2%) were employees with underweight (BMI < 18.5), whereas 346 participants (46%) were employees with normal weight (BMI between 18.5 to <25), 260 participants (34%) were employees with overweight (BMI between 25 and <30), and 135 participants (18%) were employees with obesity (BMI > 30).

Weight-based stereotype threat

We assessed weight-based stereotype threat by self-report at T2 and T3 using an adapted version of a 5-item stereotype threat scale [ 34 , 35 ], which was itself adapted from a scale to measure stereotype threat in a laboratory context [ 36 ]. We adapted the items by referring to participants’ weight instead of their gender or age as in previous studies. Participants were asked to report on their feelings of weight-based stereotype threat within the last 4 weeks. The items followed the introductory statement “Last month (in the last 4 weeks) I worried that…,” and were: “…some people at my workplace felt I have less ability because of my weight,” “…people at my workplace drew conclusions about my ability based on my weight,” “…some people at my workplace felt that I’m not committed to my work because of my weight,” “…some people at my workplace felt that I have less to contribute at work because of my weight,” “…my behavior caused people in my workplace to think that stereotypes about people of my weight are true.” Responses were provided on a five-point scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Reliability for the scale was high at both T2 (Cronbach’s α = 0.97) and T3 ( α = 0.98).

Authentic self-awareness

We measured employees’ authentic self-awareness at T2 using a four-item scale [ 21 ]. Specifically, we asked participants to think about the last 4 weeks when responding to the following items on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (not true at all) to 5 (completely true): “I understood why I thought about myself as I did,” “For better or worse, I knew who I really was,” “I understood well why I behaved like I did,” and “I felt like I didn’t know myself particularly well” (reverse coded). Alpha for the scale was 0.71.

Work ability

We measured employees’ perceived work ability at T2 and T3 using a four-item measure [ 17 ], which was based on three items from the work ability index [ 37 ] and one additional item on interpersonal demands adapted from the work ability index [ 38 ]. Participants were asked, “Please evaluate your ability in the last month (the last 4 weeks) to meet the following demands of your work.” The first three items were, “Thinking about the [physical, mental, interpersonal] demands of your work, how do your rate your ability to meet those demands?” and the fourth item was, “How many points would you give your overall ability to work?” Responses were provided on a scale from 0 (was unable to work at all) to 10 (my work ability was at its lifetime best). Reliability for the scale was α = 0.92 at T2 and α = 0.92 at T3.

Control variables

At T1, we assessed employees’ age (in years), gender (1 = male, 2 = female), highest level of education (1 = some high school to 7 = college/university degree), weight (in kilograms), height (in cms), and subjective weight. We measured subjective weight with a single item: “How would you describe your weight?” Responses were provided on a scale ranging from 1 (severely underweight) to 5 (severely overweight). We did not control for BMI, as it was highly correlated with objective and subjective weight (see Table 1 ).

Table 1 shows the means, standard deviations (SD), and correlations of all study variables. Weight, subjective weight, and BMI were positively related to weight-based stereotype threat, whereas age, authentic self-awareness, and work ability were negatively associated with weight-based stereotype threat. An exploratory analysis revealed that weight and BMI did not have curvilinear relationships with weight-based stereotype threat, suggesting that stereotype threat was generally lower among employees with lower weight and lower BMI and higher among employees with higher weight and higher BMI.

Table 2 reports the results of the regression analyses. A Kolmogorov–Smirnov test indicated that our main outcome variable, T3 work ability, was not normally distributed, D (758) = 0.108, p < 0.001. However, given our large sample size, the fact that there were more than 75 observations per predictor variable, and the sizeable SD (SD = 1.82; see Table 1 ), this violation of the normality assumption of regression analysis is not a primary concern for this study [ 39 ]. Consistent with expectations, weight-based stereotype threat was negatively related to work ability. As shown in Table 2 (Model 1), T2 weight-based stereotype threat was negatively associated with T3 work ability above and beyond the T1 control variables ( β = −0.27, p < 0.001), suggesting that employees who felt higher levels of stereotype threat subsequently perceived lower work ability. Together, weight-based stereotype threat and the control variables explained 11 percent of the variance in work ability. An additional analysis showed that the interaction between gender and weight-based stereotype threat was not significantly associated with work ability ( β = −0.03, p = 0.346), suggesting that the relationship between stereotype threat and work ability is consistent for men and women. The relationship between weight-based stereotype threat and work ability was similar when considering only employees with overweight (i.e., BMI between 25 and <30; β = −0.20, p = 0.003), only employees with obesity (i.e., BMI > 30; β = −0.31, p < 0.001), or both of these groups combined in the analysis ( β = −0.25, p < 0.001).

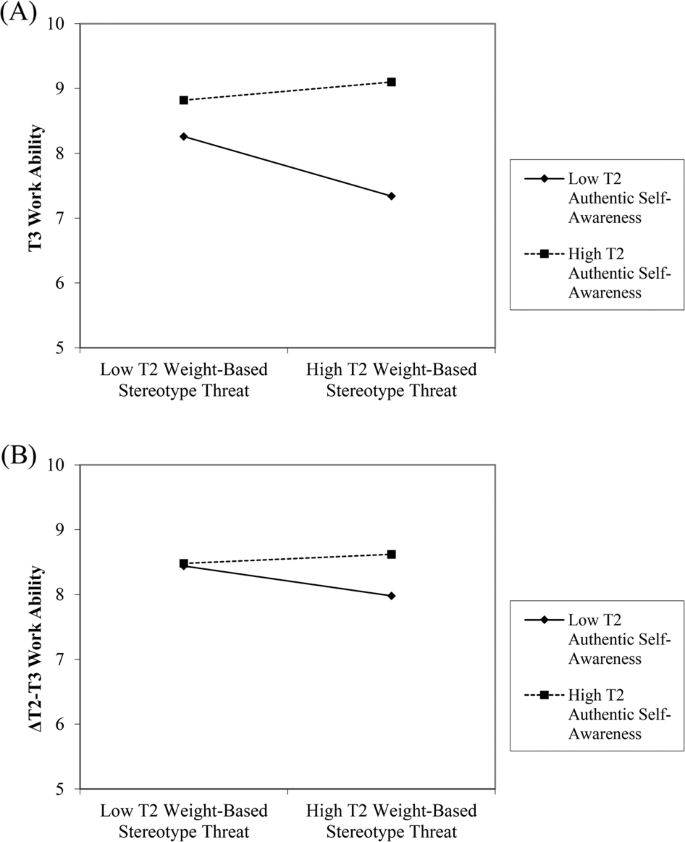

Next, we tested the prediction that authentic self-awareness moderates the relationship between weight-based stereotype threat and work ability. As shown in Table 2 (Model 2), a significant interaction emerged between weight-based stereotype threat and authentic awareness ( β = 0.14, p < 0.001) which, together with the main effect of authentic self-awareness, explained an additional eight percent of the variance in work ability. This interaction is graphically shown in Fig. 1A . Simple slope analyses showed that the relationship between weight-based stereotype threat and work ability was negative and significant at low (−1 SD) levels of authentic self-awareness ( B = −0.46, SE = 0.08, β = −0.25, t = −5.80, p < 0.001) and weak and non-significant at high (+1 SD) levels of authentic self-awareness ( B = 0.14, SE = 0.14, β = 0.08, t = 1.01, p = 0.315). An additional analysis showed that a three-way interaction between gender, weight-based stereotype threat, and authentic self-awareness (while controlling for the respective main effects and two-way interaction terms) was not associated with work ability ( β = −0.03, p = 0.413). The interaction between weight-based stereotype threat and authentic self-awareness was also significant when only considering employees with overweight in the analysis (i.e., BMI between 25 and <30; β = 0.15, p = 0.034), whereas it was not significant when considering only employees with obesity (i.e., BMI > 30; β = −0.02, p = 0.843) or both of these groups combined in the analysis ( β = 0.07, p = 0.163). Overall, these findings suggest that weight-based stereotype threat was negatively associated with work ability among employees with obesity, as well as among those employees with normal weight or overweight who had low levels of authentic self-awareness. In contrast, weight-based stereotype threat was not significantly associated with work ability among employees with normal weight or overweight who had high levels of authentic self-awareness.

Effects of T2 weight-based stereotype threat on ( A ) T3 work ability (without controlling for T2 work ability) and ( B ) T3 work ability (controlling for T2 work ability) moderated by T2 authentic self-awareness.

Supplemental analyses

We conducted a supplemental analysis in which we additionally controlled for baseline (T2) work ability (Model 3, Table 2 ). The patterns of results of this lagged endogenous change model [ 40 , 41 ] did not differ substantially from the results reported above. In particular, results suggest that the interaction between weight-based stereotype threat and authentic self-awareness was associated with change in work ability from T2 to T3 ( β = 0.07, p = 0.039). The significant interaction effect is shown in Fig. 1B . Simple slope analyses showed that the relationship between weight-based stereotype threat and change in work ability was negative and significant at low (−1 SD) levels of authentic self-awareness ( B = −0.23, SE = 0.07, β = −0.13, t = −3.22, p = 0.001) and weak and non-significant at high (+1 SD) levels of authentic self-awareness ( B = 0.07, SE = 0.12, β = 0.04, t = 0.55, p = 0.585). Again, a three-way interaction between gender, weight-based stereotype threat, and authentic self-awareness was not significantly associated with work ability ( β = 0.02, p = 0.659). Additional analyses with only employees with overweight ( β = 0.05, p = 0.378), only employees with obesity ( β = −0.03, p = 0.729), or both of these groups combined ( β = 0.01, p = 0.852) did not yield significant interaction effects. However, T2 weight-based stereotype threat still had a negative main effect when only considering employees with obesity in this analysis ( β = −0.20, p = 0.026).

To test whether the temporal order of variables we proposed represents the best fit to the data, we also estimated a reverse temporal order model in which we regressed T3 weight-based stereotype threat on the control variables, baseline (T2) weight-based stereotype threat, work ability, authentic self-awareness, and the interaction of work ability and authentic self-awareness (Model 4, Table 2 ). As shown in Model 4 (Table 2 ), age ( β = −0.07, p = 0.004) and authentic self-awareness ( β = −0.06, p = 0.044) were weakly and negatively associated with change in weight-based stereotype threat. In contrast, T2 work ability and the interaction between work ability and authentic self-awareness were not significantly associated with change in weight-based stereotype threat. An additional analysis showed that a three-way interaction between gender, work ability, and authentic self-awareness was not significantly associated with change in weight-based stereotype threat ( β = −0.04, p = 0.154). The interaction between work ability and authentic self-awareness was also non-significant when considering only employees with overweight ( β = 0.06, p = 0.092), only employees with obesity ( β = −0.08, p = 0.293), or both of these groups combined ( β = 0.01, p = 0.659).

Consistent with expectations, our correlational survey study showed that the experience of weight-based stereotype threat was associated with lower levels of work ability, and this relationship was qualified by authentic self-awareness. Specifically, the relationship between weight-based stereotype threat and work ability was non-significant among employees with higher authentic self-awareness, whereas employees with lower authentic self-awareness reported lower work ability when they experienced weight-based stereotype threat. This interaction effect was weaker, but still significant, when baseline levels of work ability were controlled, suggesting that the interaction between weight-based stereotype threat and authentic self-awareness is associated with mean-level changes in work ability across 1 month.

These findings, albeit correlational and not causal, advance research on stereotype threat, work ability, and authenticity. Most research on stereotype threat has been conducted in the laboratory, and stereotype threat research in a work context has neglected weight-based stereotype threat [ 12 ]. The current results demonstrate that employees with overweight or obesity experience weight-based stereotype threat and this concern, in turn, can diminish their sense of work ability. Work ability is associated with increased absenteeism, disability leave, and early retirement [ 17 ], suggesting that weight-based stereotype threat might be indirectly related to these outcomes. Indeed, this has been shown for other forms of stereotype threat in the workplace [ 42 ]. Additionally, if stereotype threat is negatively associated with work ability it might create a vicious cycle whereby diminished work ability fuels the stereotypes about people with overweight or obesity, thereby making these employees even more susceptible to stereotype threat.

Our findings are consistent with prior research suggesting that high authentic self-awareness constitutes a psychological resource and coping mechanism [ 19 , 20 , 21 ], as it seems to make employees less susceptible to the detrimental consequences of weight-based stereotype threat. It is important to note, however, that authentic self-awareness did not moderate the association between weight-based stereotype threat and work ability when only employees with obesity were considered in the analysis. Due to the fact that these employees are the most overweight and hence the most easily identified as such, it is not surprising that they were also found to be more susceptible to weight-based stereotype threat than employees with overweight or normal weight (i.e., we found positive linear relationships of weight and BMI with weight-based stereotype threat). Thus, it seems likely that authentic self-awareness may only serve a protective function among employees who experience relatively lower levels of stereotype threat (in the current case, employees with overweight, but not those with obesity).

Finally, the bivariate correlations showed that older employees weighed more and had higher BMIs, but nonetheless experienced less weight-based stereotype threat than younger employees. While the former finding is consistent with the literature on work and health [ 43 ], a potential explanation for the latter finding is that older employees have accumulated more work and life experience and may, therefore, be less concerned that other people at work reduce them to weight-based stereotypes. Moreover, the positive relationship between age and authentic self-awareness suggests that older employees possess greater knowledge about various aspects of their selves and, thus, may be less susceptible to experiencing weight-based stereotype threat.

Limitations and future research

This study integrates psychological theorizing on stereotype threat with the literature on obesity and weight stigma to examine the consequences of weight-based stereotype threat in the workplace. Most weight-stigma research focuses on women with overweight [ 44 , 45 ], whereas our sample includes men and women. Additional analyses showed that two- and three-way interactions of gender with weight-based stereotype threat and authentic self-awareness were not significantly associated with work ability. Nevertheless, examining both genders continues to be important in light of the inconsistent associations of weight stigma with potential outcome variables in a workplace context, with some research showing men to be more susceptible and other research showing women to be more susceptible to weight-based prejudice and discrimination (see [ 1 ]). Thus, further research is needed that addresses the issue of intersectionality, or how the combination of gender, weight, and other relevant characteristics may be associated with potential detrimental consequences in the workplace [ 46 , 47 ].

Nonetheless, this study has a number of limitations that should be addressed in future research. First, all of the constructs in our study were assessed using self-report, which may raise concerns about artificially inflated associations due to common method bias. However, following methodological recommendations [ 48 ], we temporally separated measurements of our predictor and outcome variables. Additionally, our predictor, moderator and outcome variables used different response scales, helping to further combat common method variance [ 49 ]. Perhaps most importantly, methodologists have demonstrated that interaction effects are not inflated by common method bias [ 50 ]. Nonetheless, research demonstrates that self- and other-reports of authentic self-awareness are weak and non-significant [ 21 ], suggesting there may be limitations in the accessibility of self-knowledge or that self-presentation biases people’s judgements [ 51 ]. To address this possibility, future research could supplement self-report measures of authentic self-awareness with reports obtained from other people (e.g., co-workers, family members).

Second, although work ability is an important outcome, future studies should examine the associations of weight-based stereotype threat with additional engagement- and disengagement-related work outcomes. Research with employees from other stigmatized groups demonstrates that stereotype threat is associated with more negative job attitudes and increased intentions to quit [ 12 ]. Lower work ability also relates to more negative attitudes and intentions to quit [ 17 ], raising the possibility that work ability may play a mediating role between the experience of stereotype threat and these outcomes.

Previous research has neglected the potential consequences of weight-based stereotype threat in the work context. Consistent with stereotype threat theory, we found a negative relationship between employees’ experiences of weight-based stereotype threat and work ability, which was weaker among those with higher levels of authentic self-awareness. Thus, organizations should identify ways to enhance authentic self-awareness, particularly among employees who may be susceptible to the negative effects of weight-based stereotype threat.

Puhl RM, Heuer CA. The stigma of obesity: a review and update. Obesity. 2009;17:941–64.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bellizzi JA, Norvell DW. Personal characteristics and salesperson’s justifications as moderators of supervisory discipline in cases involving unethical salesforce behavior. J Acad Mark Sci. 1991;19:11–6.

Article Google Scholar

Brochu PM, Esses VM. What’s in a name? The effects of the labels “fat” versus “overweight” on weight bias. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2011;41:1981–2008.

Rudolph CW, Wells CL, Weller MD, Baltes BB. A meta-analysis of empirical studies of weight-based bias in the workplace. J Vocat Behav. 2009;74:1–10.

Campos-Vazquez RM, Gonzalez E. Obesity and hiring discrimination. Econ Hum Biol. 2020;37:100850.

Klarenbach S, Padwal R, Chuck A, Jacobs P. Population‐based analysis of obesity and workforce participation. Obesity. 2006;14:920–7.

Judge TA, Cable DM. When it comes to pay, do the thin win? The effect of weight on pay for men and women. J Appl Psychol. 2011;96:95–112.

Lindeman MI, Crandall AK, Finkelstein LM. The effects of messages about the causes of obesity on disciplinary action decisions for overweight employees. J Psychol. 2017;151:345–58.

Sliter KA, Sliter MT, Withrow SA, Jex SM. Employee adiposity and incivility: establishing a link and identifying demographic moderators and negative consequences. J Occup Health Psychol. 2012;17:409–24.

Steele CM. A threat in the air: How stereotypes shape intellectual identity and performance. Am Psychol. 1997;52:613–29.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Spencer SJ, Logel C, Davies PG. Stereotype threat. Annu Rev Psychol. 2016;67:415–37.

Kalokerinos EK, Von Hippel C, Zacher H. Is stereotype threat a useful construct for organizational psychology research and practice? Ind Organ Psychol. 2014;7:381–402.

von Hippel C. Stereotype threat in the workplace. In: Paludi M, editor. Managing diversity in today’s workplaces. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO; 2012.

Roberson L, Kulik CT. Stereotype threat at work. Acad Manag Perspect. 2007;21:24–40.

World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight. 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight .

Guardabassi V, Tomasetto C. Does weight stigma reduce working memory? Evidence of stereotype threat susceptibility in adults with obesity. Int J Obes. 2018;42:1500–7.

McGonagle A, Fisher GG, Barnes‐Farrell JL, Grosch J. Individual and work factors related to perceived work ability and labor force outcomes. J Appl Psychol. 2015;100:376–98.

Ilmarinen J. Work ability: a comprehensive concept for occupational health research and prevention. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2009;35:1–5.

Cha SE, Hewlin PF, Roberts LM, Buckman BR, Leroy H, Steckler EL, et al. Being your true self at work: Integrating the fragmented research on authenticity in organizations. Acad Manag Ann. 2019;13:633–71.

Kernis MH, Goldman BM. A multicomponent conceptualization of authenticity: theory and research. Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 2006;38:283–357.

Knoll M, Meyer B, Kroemer NB, Schröder-Abé M. It takes two to be yourself: an integrated model of authenticity, its measurement, and its relationship to work-related variables. J Individ Differ. 2015;36:38–53.

Puhl RM, Brownell KD. Confronting and coping with weight stigma: an investigation of overweight and obese adults. Obesity. 2006;14:1802–15.

Himmelstein MS, Puhl RM, Quinn DM. Weight stigma and health: the mediating role of coping responses. Health Psycho. 2018;37:139–47.

Campbell JD, Trapnell PD, Heine SJ, Katz IM, Lavallee LF, Lehman DR. Self-concept clarity: measurement, personality correlates, and cultural boundaries. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;70:141–56.

Zeigler-Hill V, Showers CJ. Self-structure and self-esteem stability: the hidden vulnerability of compartmentalization. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2007;33:143–59.

Seery MD, Blascovich J, Weisbuch M, Vick SB. The relationship between self-esteem level, self-esteem stability, and cardiovascular reactions to performance feedback. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2004;87:133–45.

Sheldon KM, Ryan RM, Rawsthorne LJ, Ilardi B. Trait self and true self: cross-role variation in the Big-Five personality traits and its relations with psychological authenticity and subjective well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;73:1380–93.

Hayward LE, Vartanian LR, Pinkus RT. Coping with weight stigma: development and validation of a brief coping responses inventory. Obes Sci Pract. 2017;3:373–83.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Himmelstein MS, Puhl RM, Pearl RL, Pinto AM, Foster GD. Coping with weight stigma among adults in a commercial weight management sample. Int J Behav Med. 2020;27:576–90.

Avolio BJ, Gardner WL. Authentic leadership development: getting to the root of positive forms of leadership. Leadersh Q. 2005;16:315–38.

Weiss M, Zacher H. Why and when does voice lead to increased job engagement? The role of perceived voice appreciation and emotional stability. J Vocat Behav. 2022;132:103662.

Zacher H, Rudolph CW. Strength and vulnerability: indirect effects of age on changes in occupational well-being through emotion regulation and physiological disease. Psychol Aging. 2021; https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000671 .

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988.

Google Scholar

von Hippel C, Issa M, Ma R, Stokes A. Stereotype threat: antecedents and consequences for working women. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2011;41:151–61.

von Hippel C, Kalokerinos EK, Henry JD. Stereotype threat among older employees: relationships with job attitudes and turnover intentions. Psychol Aging. 2013;28:17–27.

Steele CM, Aronson J. Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69:797–811.

Tuomi K, Ilmarinen JA, Jahkola A, Katajarinne L, Tulkki A. Work ability index. 2nd ed. Helsinki, Finland: Finnish Institute of Occupational Health; 1998.

Barnes-Farrell JL, Bobko N, Fischer F, Iskra-Golec I, Kaliterna L, Tepas D. Comparisons of work ability for health care workers in five nations. In: Ilmarinen J, Lehtinen S, editors. Past, present and future of work ability: Proceedings of the 1st International Symposium on Work Ability. Helsinki, Finland: Finnish Institute of Occupational Health; 2004. p. 76–82.

Schmidt AF, Finan C. Linear regression and the normality assumption. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;98:146–51.

Finkel SE. Linear panel analysis. In: Menard S, editor. Handbook of longitudinal research: design, measurement, and analysis. New York: Academic Press; 2008. p. 475–504.

Aickin M. Dealing with change: using the conditional change model for clinical research. Perm J. 2009;13:80–4.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Von Hippel C, Kalokerinos EK, Haanterä K, Zacher H. Age-based stereotype threat and work outcomes: stress appraisals and rumination as mediators. Psychold Aging. 2019;34:68–84.

Ng TWH, Feldman DC. Employee age and health. J Vocat Behav. 2013;83:336–45.

Major B, Eliezer D, Rieck H. The psychological weight of weight stigma. Soc Psychol Personal Sci. 2012;3:651–8.