Classroom Q&A

With larry ferlazzo.

In this EdWeek blog, an experiment in knowledge-gathering, Ferlazzo will address readers’ questions on classroom management, ELL instruction, lesson planning, and other issues facing teachers. Send your questions to [email protected]. Read more from this blog.

Integrating Critical Thinking Into the Classroom

- Share article

(This is the second post in a three-part series. You can see Part One here .)

The new question-of-the-week is:

What is critical thinking and how can we integrate it into the classroom?

Part One ‘s guests were Dara Laws Savage, Patrick Brown, Meg Riordan, Ph.D., and Dr. PJ Caposey. Dara, Patrick, and Meg were also guests on my 10-minute BAM! Radio Show . You can also find a list of, and links to, previous shows here.

Today, Dr. Kulvarn Atwal, Elena Quagliarello, Dr. Donna Wilson, and Diane Dahl share their recommendations.

‘Learning Conversations’

Dr. Kulvarn Atwal is currently the executive head teacher of two large primary schools in the London borough of Redbridge. Dr. Atwal is the author of The Thinking School: Developing a Dynamic Learning Community , published by John Catt Educational. Follow him on Twitter @Thinkingschool2 :

In many classrooms I visit, students’ primary focus is on what they are expected to do and how it will be measured. It seems that we are becoming successful at producing students who are able to jump through hoops and pass tests. But are we producing children that are positive about teaching and learning and can think critically and creatively? Consider your classroom environment and the extent to which you employ strategies that develop students’ critical-thinking skills and their self-esteem as learners.

Development of self-esteem

One of the most significant factors that impacts students’ engagement and achievement in learning in your classroom is their self-esteem. In this context, self-esteem can be viewed to be the difference between how they perceive themselves as a learner (perceived self) and what they consider to be the ideal learner (ideal self). This ideal self may reflect the child that is associated or seen to be the smartest in the class. Your aim must be to raise students’ self-esteem. To do this, you have to demonstrate that effort, not ability, leads to success. Your language and interactions in the classroom, therefore, have to be aspirational—that if children persist with something, they will achieve.

Use of evaluative praise

Ensure that when you are praising students, you are making explicit links to a child’s critical thinking and/or development. This will enable them to build their understanding of what factors are supporting them in their learning. For example, often when we give feedback to students, we may simply say, “Well done” or “Good answer.” However, are the students actually aware of what they did well or what was good about their answer? Make sure you make explicit what the student has done well and where that links to prior learning. How do you value students’ critical thinking—do you praise their thinking and demonstrate how it helps them improve their learning?

Learning conversations to encourage deeper thinking

We often feel as teachers that we have to provide feedback to every students’ response, but this can limit children’s thinking. Encourage students in your class to engage in learning conversations with each other. Give as many opportunities as possible to students to build on the responses of others. Facilitate chains of dialogue by inviting students to give feedback to each other. The teacher’s role is, therefore, to facilitate this dialogue and select each individual student to give feedback to others. It may also mean that you do not always need to respond at all to a student’s answer.

Teacher modelling own thinking

We cannot expect students to develop critical-thinking skills if we aren’t modeling those thinking skills for them. Share your creativity, imagination, and thinking skills with the students and you will nurture creative, imaginative critical thinkers. Model the language you want students to learn and think about. Share what you feel about the learning activities your students are participating in as well as the thinking you are engaging in. Your own thinking and learning will add to the discussions in the classroom and encourage students to share their own thinking.

Metacognitive questioning

Consider the extent to which your questioning encourages students to think about their thinking, and therefore, learn about learning! Through asking metacognitive questions, you will enable your students to have a better understanding of the learning process, as well as their own self-reflections as learners. Example questions may include:

- Why did you choose to do it that way?

- When you find something tricky, what helps you?

- How do you know when you have really learned something?

‘Adventures of Discovery’

Elena Quagliarello is the senior editor of education for Scholastic News , a current events magazine for students in grades 3–6. She graduated from Rutgers University, where she studied English and earned her master’s degree in elementary education. She is a certified K–12 teacher and previously taught middle school English/language arts for five years:

Critical thinking blasts through the surface level of a topic. It reaches beyond the who and the what and launches students on a learning journey that ultimately unlocks a deeper level of understanding. Teaching students how to think critically helps them turn information into knowledge and knowledge into wisdom. In the classroom, critical thinking teaches students how to ask and answer the questions needed to read the world. Whether it’s a story, news article, photo, video, advertisement, or another form of media, students can use the following critical-thinking strategies to dig beyond the surface and uncover a wealth of knowledge.

A Layered Learning Approach

Begin by having students read a story, article, or analyze a piece of media. Then have them excavate and explore its various layers of meaning. First, ask students to think about the literal meaning of what they just read. For example, if students read an article about the desegregation of public schools during the 1950s, they should be able to answer questions such as: Who was involved? What happened? Where did it happen? Which details are important? This is the first layer of critical thinking: reading comprehension. Do students understand the passage at its most basic level?

Ask the Tough Questions

The next layer delves deeper and starts to uncover the author’s purpose and craft. Teach students to ask the tough questions: What information is included? What or who is left out? How does word choice influence the reader? What perspective is represented? What values or people are marginalized? These questions force students to critically analyze the choices behind the final product. In today’s age of fast-paced, easily accessible information, it is essential to teach students how to critically examine the information they consume. The goal is to equip students with the mindset to ask these questions on their own.

Strike Gold

The deepest layer of critical thinking comes from having students take a step back to think about the big picture. This level of thinking is no longer focused on the text itself but rather its real-world implications. Students explore questions such as: Why does this matter? What lesson have I learned? How can this lesson be applied to other situations? Students truly engage in critical thinking when they are able to reflect on their thinking and apply their knowledge to a new situation. This step has the power to transform knowledge into wisdom.

Adventures of Discovery

There are vast ways to spark critical thinking in the classroom. Here are a few other ideas:

- Critical Expressionism: In this expanded response to reading from a critical stance, students are encouraged to respond through forms of artistic interpretations, dramatizations, singing, sketching, designing projects, or other multimodal responses. For example, students might read an article and then create a podcast about it or read a story and then act it out.

- Transmediations: This activity requires students to take an article or story and transform it into something new. For example, they might turn a news article into a cartoon or turn a story into a poem. Alternatively, students may rewrite a story by changing some of its elements, such as the setting or time period.

- Words Into Action: In this type of activity, students are encouraged to take action and bring about change. Students might read an article about endangered orangutans and the effects of habitat loss caused by deforestation and be inspired to check the labels on products for palm oil. They might then write a letter asking companies how they make sure the palm oil they use doesn’t hurt rain forests.

- Socratic Seminars: In this student-led discussion strategy, students pose thought-provoking questions to each other about a topic. They listen closely to each other’s comments and think critically about different perspectives.

- Classroom Debates: Aside from sparking a lively conversation, classroom debates naturally embed critical-thinking skills by asking students to formulate and support their own opinions and consider and respond to opposing viewpoints.

Critical thinking has the power to launch students on unforgettable learning experiences while helping them develop new habits of thought, reflection, and inquiry. Developing these skills prepares students to examine issues of power and promote transformative change in the world around them.

‘Quote Analysis’

Dr. Donna Wilson is a psychologist and the author of 20 books, including Developing Growth Mindsets , Teaching Students to Drive Their Brains , and Five Big Ideas for Effective Teaching (2 nd Edition). She is an international speaker who has worked in Asia, the Middle East, Australia, Europe, Jamaica, and throughout the U.S. and Canada. Dr. Wilson can be reached at [email protected] ; visit her website at www.brainsmart.org .

Diane Dahl has been a teacher for 13 years, having taught grades 2-4 throughout her career. Mrs. Dahl currently teaches 3rd and 4th grade GT-ELAR/SS in Lovejoy ISD in Fairview, Texas. Follow her on Twitter at @DahlD, and visit her website at www.fortheloveofteaching.net :

A growing body of research over the past several decades indicates that teaching students how to be better thinkers is a great way to support them to be more successful at school and beyond. In the book, Teaching Students to Drive Their Brains , Dr. Wilson shares research and many motivational strategies, activities, and lesson ideas that assist students to think at higher levels. Five key strategies from the book are as follows:

- Facilitate conversation about why it is important to think critically at school and in other contexts of life. Ideally, every student will have a contribution to make to the discussion over time.

- Begin teaching thinking skills early in the school year and as a daily part of class.

- As this instruction begins, introduce students to the concept of brain plasticity and how their brilliant brains change during thinking and learning. This can be highly motivational for students who do not yet believe they are good thinkers!

- Explicitly teach students how to use the thinking skills.

- Facilitate student understanding of how the thinking skills they are learning relate to their lives at school and in other contexts.

Below are two lessons that support critical thinking, which can be defined as the objective analysis and evaluation of an issue in order to form a judgment.

Mrs. Dahl prepares her 3rd and 4th grade classes for a year of critical thinking using quote analysis .

During Native American studies, her 4 th grade analyzes a Tuscarora quote: “Man has responsibility, not power.” Since students already know how the Native Americans’ land had been stolen, it doesn’t take much for them to make the logical leaps. Critical-thought prompts take their thinking even deeper, especially at the beginning of the year when many need scaffolding. Some prompts include:

- … from the point of view of the Native Americans?

- … from the point of view of the settlers?

- How do you think your life might change over time as a result?

- Can you relate this quote to anything else in history?

Analyzing a topic from occupational points of view is an incredibly powerful critical-thinking tool. After learning about the Mexican-American War, Mrs. Dahl’s students worked in groups to choose an occupation with which to analyze the war. The chosen occupations were: anthropologist, mathematician, historian, archaeologist, cartographer, and economist. Then each individual within each group chose a different critical-thinking skill to focus on. Finally, they worked together to decide how their occupation would view the war using each skill.

For example, here is what each student in the economist group wrote:

- When U.S.A. invaded Mexico for land and won, Mexico ended up losing income from the settlements of Jose de Escandon. The U.S.A. thought that they were gaining possible tradable land, while Mexico thought that they were losing precious land and resources.

- Whenever Texas joined the states, their GDP skyrocketed. Then they went to war and spent money on supplies. When the war was resolving, Texas sold some of their land to New Mexico for $10 million. This allowed Texas to pay off their debt to the U.S., improving their relationship.

- A detail that converged into the Mexican-American War was that Mexico and the U.S. disagreed on the Texas border. With the resulting treaty, Texas ended up gaining more land and economic resources.

- Texas gained land from Mexico since both countries disagreed on borders. Texas sold land to New Mexico, which made Texas more economically structured and allowed them to pay off their debt.

This was the first time that students had ever used the occupations technique. Mrs. Dahl was astonished at how many times the kids used these critical skills in other areas moving forward.

Thanks to Dr. Auwal, Elena, Dr. Wilson, and Diane for their contributions!

Please feel free to leave a comment with your reactions to the topic or directly to anything that has been said in this post.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at [email protected] . When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at @Larryferlazzo .

Education Week has published a collection of posts from this blog, along with new material, in an e-book form. It’s titled Classroom Management Q&As: Expert Strategies for Teaching .

Just a reminder; you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via email (The RSS feed for this blog, and for all Ed Week articles, has been changed by the new redesign—new ones won’t be available until February). And if you missed any of the highlights from the first nine years of this blog, you can see a categorized list below.

- This Year’s Most Popular Q&A Posts

- Race & Racism in Schools

- School Closures & the Coronavirus Crisis

- Classroom-Management Advice

- Best Ways to Begin the School Year

- Best Ways to End the School Year

- Student Motivation & Social-Emotional Learning

- Implementing the Common Core

- Facing Gender Challenges in Education

- Teaching Social Studies

- Cooperative & Collaborative Learning

- Using Tech in the Classroom

- Student Voices

- Parent Engagement in Schools

- Teaching English-Language Learners

- Reading Instruction

- Writing Instruction

- Education Policy Issues

- Differentiating Instruction

- Math Instruction

- Science Instruction

- Advice for New Teachers

- Author Interviews

- Entering the Teaching Profession

- The Inclusive Classroom

- Learning & the Brain

- Administrator Leadership

- Teacher Leadership

- Relationships in Schools

- Professional Development

- Instructional Strategies

- Best of Classroom Q&A

- Professional Collaboration

- Classroom Organization

- Mistakes in Education

- Project-Based Learning

I am also creating a Twitter list including all contributors to this column .

The opinions expressed in Classroom Q&A With Larry Ferlazzo are strictly those of the author(s) and do not reflect the opinions or endorsement of Editorial Projects in Education, or any of its publications.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

- Our Mission

Helping Students Hone Their Critical Thinking Skills

Used consistently, these strategies can help middle and high school teachers guide students to improve much-needed skills.

Critical thinking skills are important in every discipline, at and beyond school. From managing money to choosing which candidates to vote for in elections to making difficult career choices, students need to be prepared to take in, synthesize, and act on new information in a world that is constantly changing.

While critical thinking might seem like an abstract idea that is tough to directly instruct, there are many engaging ways to help students strengthen these skills through active learning.

Make Time for Metacognitive Reflection

Create space for students to both reflect on their ideas and discuss the power of doing so. Show students how they can push back on their own thinking to analyze and question their assumptions. Students might ask themselves, “Why is this the best answer? What information supports my answer? What might someone with a counterargument say?”

Through this reflection, students and teachers (who can model reflecting on their own thinking) gain deeper understandings of their ideas and do a better job articulating their beliefs. In a world that is go-go-go, it is important to help students understand that it is OK to take a breath and think about their ideas before putting them out into the world. And taking time for reflection helps us more thoughtfully consider others’ ideas, too.

Teach Reasoning Skills

Reasoning skills are another key component of critical thinking, involving the abilities to think logically, evaluate evidence, identify assumptions, and analyze arguments. Students who learn how to use reasoning skills will be better equipped to make informed decisions, form and defend opinions, and solve problems.

One way to teach reasoning is to use problem-solving activities that require students to apply their skills to practical contexts. For example, give students a real problem to solve, and ask them to use reasoning skills to develop a solution. They can then present their solution and defend their reasoning to the class and engage in discussion about whether and how their thinking changed when listening to peers’ perspectives.

A great example I have seen involved students identifying an underutilized part of their school and creating a presentation about one way to redesign it. This project allowed students to feel a sense of connection to the problem and come up with creative solutions that could help others at school. For more examples, you might visit PBS’s Design Squad , a resource that brings to life real-world problem-solving.

Ask Open-Ended Questions

Moving beyond the repetition of facts, critical thinking requires students to take positions and explain their beliefs through research, evidence, and explanations of credibility.

When we pose open-ended questions, we create space for classroom discourse inclusive of diverse, perhaps opposing, ideas—grounds for rich exchanges that support deep thinking and analysis.

For example, “How would you approach the problem?” and “Where might you look to find resources to address this issue?” are two open-ended questions that position students to think less about the “right” answer and more about the variety of solutions that might already exist.

Journaling, whether digitally or physically in a notebook, is another great way to have students answer these open-ended prompts—giving them time to think and organize their thoughts before contributing to a conversation, which can ensure that more voices are heard.

Once students process in their journal, small group or whole class conversations help bring their ideas to life. Discovering similarities between answers helps reveal to students that they are not alone, which can encourage future participation in constructive civil discourse.

Teach Information Literacy

Education has moved far past the idea of “Be careful of what is on Wikipedia, because it might not be true.” With AI innovations making their way into classrooms, teachers know that informed readers must question everything.

Understanding what is and is not a reliable source and knowing how to vet information are important skills for students to build and utilize when making informed decisions. You might start by introducing the idea of bias: Articles, ads, memes, videos, and every other form of media can push an agenda that students may not see on the surface. Discuss credibility, subjectivity, and objectivity, and look at examples and nonexamples of trusted information to prepare students to be well-informed members of a democracy.

One of my favorite lessons is about the Pacific Northwest tree octopus . This project asks students to explore what appears to be a very real website that provides information on this supposedly endangered animal. It is a wonderful, albeit over-the-top, example of how something might look official even when untrue, revealing that we need critical thinking to break down “facts” and determine the validity of the information we consume.

A fun extension is to have students come up with their own website or newsletter about something going on in school that is untrue. Perhaps a change in dress code that requires everyone to wear their clothes inside out or a change to the lunch menu that will require students to eat brussels sprouts every day.

Giving students the ability to create their own falsified information can help them better identify it in other contexts. Understanding that information can be “too good to be true” can help them identify future falsehoods.

Provide Diverse Perspectives

Consider how to keep the classroom from becoming an echo chamber. If students come from the same community, they may have similar perspectives. And those who have differing perspectives may not feel comfortable sharing them in the face of an opposing majority.

To support varying viewpoints, bring diverse voices into the classroom as much as possible, especially when discussing current events. Use primary sources: videos from YouTube, essays and articles written by people who experienced current events firsthand, documentaries that dive deeply into topics that require some nuance, and any other resources that provide a varied look at topics.

I like to use the Smithsonian “OurStory” page , which shares a wide variety of stories from people in the United States. The page on Japanese American internment camps is very powerful because of its first-person perspectives.

Practice Makes Perfect

To make the above strategies and thinking routines a consistent part of your classroom, spread them out—and build upon them—over the course of the school year. You might challenge students with information and/or examples that require them to use their critical thinking skills; work these skills explicitly into lessons, projects, rubrics, and self-assessments; or have students practice identifying misinformation or unsupported arguments.

Critical thinking is not learned in isolation. It needs to be explored in English language arts, social studies, science, physical education, math. Every discipline requires students to take a careful look at something and find the best solution. Often, these skills are taken for granted, viewed as a by-product of a good education, but true critical thinking doesn’t just happen. It requires consistency and commitment.

In a moment when information and misinformation abound, and students must parse reams of information, it is imperative that we support and model critical thinking in the classroom to support the development of well-informed citizens.

25 Of The Best Resources For Teaching Critical Thinking

From rubrics and presentations to apps, definitions, and frameworks, here are 25 of the best resources for critical thinking.

25 Of The Best Resources For Teaching Critical Thinking

by TeachThought Staff

As an organization, critical thinking is at the core of what we do, from essays and lists to models and teacher training.

For this post, we’ve gathered various critical thinking resources. As you’ll notice, conversation is a fundamental part of critical thinking. Why? The ability to identify a line of reasoning, analyze, evaluate, and respond to it accurately and thoughtfully is among the most common opportunities for critical thinking for students in everyday life. Who is saying what? What’s valid and what’s not? How should I respond?

This varied and purposely broad collection includes resources for teaching critical thinking, from books and videos to graphics and models, rubrics, and taxonomies to presentations and debate communities.

See also 10 Team-Building Games That Promote Critical Thinking

1. The TeachThought Taxonomy for Understanding , a taxonomy of thinking tasks broken up into 6 categories, with 6 tasks per category

2. 60 Critical Thinking Strategies For Learning by Terry Heick

3. It’s difficult to create a collection of critical thinking resources without talking about failures in thinking, so here’s A Logical Fallacies Primer via Wikipedia .

4. The Watson-Glaser Critical Thinking Test (this link keeps moving around so I’ve removed it for now; if you can’t find it, let me know ).

5. 6 Hats Thinking is a model for divergent thinking.

6. 6 Strategies for Teac h ing With Bloom’s Taxonomy

7. An Intro To Critical Thinking , a 10-minute video from wireless philosophy that takes given premises, and walks the viewer through valid and erroneous conclusions

8. Why Questions Are More Important Than Answers by Terry Heick

9. 20 Types Of Questions For Teaching Critical Thinking

10. A Collection Of Bloom’s Taxonomy Posters

11. 6 Facets of Understanding by Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe

12. A Comprehensive Visual Codex Of Cognitive Biases

13. Helping Students Ask Better Questions

14. Examples Of Socratic Seminar-Style Questions (including stems) from changingminds.org

15. 20 Questions To Guide Inquiry-Based Learning , a 4-step process to guide learning through inquiry and thought

16. Socratic Seminar Guidelines by Grant Wiggins

17. How To Bring Socratic Seminars Into Your Classroom , a 7-minute video by the Teaching Channel

18. How To Teach With The Socratic Seminar Paideia Style, a PDF document by the Paideia that overviews

19. Using The QFT Model To Guide Inquiry & Thought

20. Create Debate , a website that hosts debates

20. Intelligence Squared is a Oxford-style debate ‘show’ hosted by NPR

21. Ways To Help Students Think For Themselves by Terry Heick

22. A Rubric To Assess Critical Thinking (they have several free rubrics, but you have to register for a free account to gain access)

23. 25 Critical Thinking Apps For Extended Student Thought

24. Debate.org is a ‘debate’ community that promotes topic-driven discussion and critical thought

25. A Collection Of Research On Critical Thinking by criticalthinking.org

TeachThought is an organization dedicated to innovation in education through the growth of outstanding teachers.

Why Schools Need to Change Yes, We Can Define, Teach, and Assess Critical Thinking Skills

Jeff Heyck-Williams (He, His, Him) Director of the Two Rivers Learning Institute in Washington, DC

Today’s learners face an uncertain present and a rapidly changing future that demand far different skills and knowledge than were needed in the 20th century. We also know so much more about enabling deep, powerful learning than we ever did before. Our collective future depends on how well young people prepare for the challenges and opportunities of 21st-century life.

Critical thinking is a thing. We can define it; we can teach it; and we can assess it.

While the idea of teaching critical thinking has been bandied around in education circles since at least the time of John Dewey, it has taken greater prominence in the education debates with the advent of the term “21st century skills” and discussions of deeper learning. There is increasing agreement among education reformers that critical thinking is an essential ingredient for long-term success for all of our students.

However, there are still those in the education establishment and in the media who argue that critical thinking isn’t really a thing, or that these skills aren’t well defined and, even if they could be defined, they can’t be taught or assessed.

To those naysayers, I have to disagree. Critical thinking is a thing. We can define it; we can teach it; and we can assess it. In fact, as part of a multi-year Assessment for Learning Project , Two Rivers Public Charter School in Washington, D.C., has done just that.

Before I dive into what we have done, I want to acknowledge that some of the criticism has merit.

First, there are those that argue that critical thinking can only exist when students have a vast fund of knowledge. Meaning that a student cannot think critically if they don’t have something substantive about which to think. I agree. Students do need a robust foundation of core content knowledge to effectively think critically. Schools still have a responsibility for building students’ content knowledge.

However, I would argue that students don’t need to wait to think critically until after they have mastered some arbitrary amount of knowledge. They can start building critical thinking skills when they walk in the door. All students come to school with experience and knowledge which they can immediately think critically about. In fact, some of the thinking that they learn to do helps augment and solidify the discipline-specific academic knowledge that they are learning.

The second criticism is that critical thinking skills are always highly contextual. In this argument, the critics make the point that the types of thinking that students do in history is categorically different from the types of thinking students do in science or math. Thus, the idea of teaching broadly defined, content-neutral critical thinking skills is impossible. I agree that there are domain-specific thinking skills that students should learn in each discipline. However, I also believe that there are several generalizable skills that elementary school students can learn that have broad applicability to their academic and social lives. That is what we have done at Two Rivers.

Defining Critical Thinking Skills

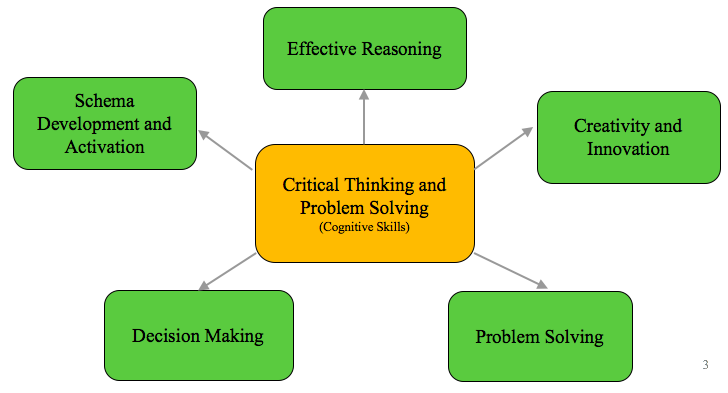

We began this work by first defining what we mean by critical thinking. After a review of the literature and looking at the practice at other schools, we identified five constructs that encompass a set of broadly applicable skills: schema development and activation; effective reasoning; creativity and innovation; problem solving; and decision making.

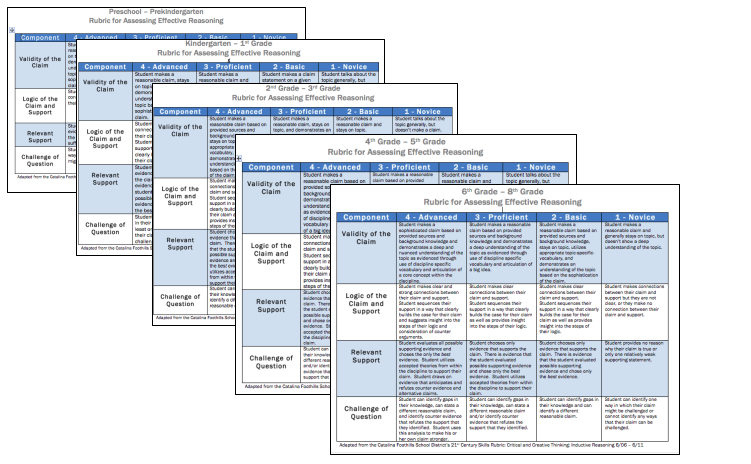

We then created rubrics to provide a concrete vision of what each of these constructs look like in practice. Working with the Stanford Center for Assessment, Learning and Equity (SCALE) , we refined these rubrics to capture clear and discrete skills.

For example, we defined effective reasoning as the skill of creating an evidence-based claim: students need to construct a claim, identify relevant support, link their support to their claim, and identify possible questions or counter claims. Rubrics provide an explicit vision of the skill of effective reasoning for students and teachers. By breaking the rubrics down for different grade bands, we have been able not only to describe what reasoning is but also to delineate how the skills develop in students from preschool through 8th grade.

Before moving on, I want to freely acknowledge that in narrowly defining reasoning as the construction of evidence-based claims we have disregarded some elements of reasoning that students can and should learn. For example, the difference between constructing claims through deductive versus inductive means is not highlighted in our definition. However, by privileging a definition that has broad applicability across disciplines, we are able to gain traction in developing the roots of critical thinking. In this case, to formulate well-supported claims or arguments.

Teaching Critical Thinking Skills

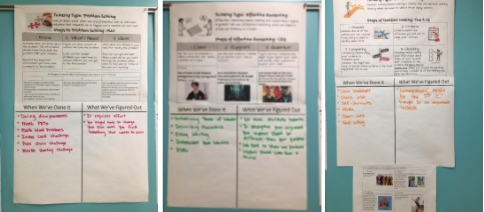

The definitions of critical thinking constructs were only useful to us in as much as they translated into practical skills that teachers could teach and students could learn and use. Consequently, we have found that to teach a set of cognitive skills, we needed thinking routines that defined the regular application of these critical thinking and problem-solving skills across domains. Building on Harvard’s Project Zero Visible Thinking work, we have named routines aligned with each of our constructs.

For example, with the construct of effective reasoning, we aligned the Claim-Support-Question thinking routine to our rubric. Teachers then were able to teach students that whenever they were making an argument, the norm in the class was to use the routine in constructing their claim and support. The flexibility of the routine has allowed us to apply it from preschool through 8th grade and across disciplines from science to economics and from math to literacy.

Kathryn Mancino, a 5th grade teacher at Two Rivers, has deliberately taught three of our thinking routines to students using the anchor charts above. Her charts name the components of each routine and has a place for students to record when they’ve used it and what they have figured out about the routine. By using this structure with a chart that can be added to throughout the year, students see the routines as broadly applicable across disciplines and are able to refine their application over time.

Assessing Critical Thinking Skills

By defining specific constructs of critical thinking and building thinking routines that support their implementation in classrooms, we have operated under the assumption that students are developing skills that they will be able to transfer to other settings. However, we recognized both the importance and the challenge of gathering reliable data to confirm this.

With this in mind, we have developed a series of short performance tasks around novel discipline-neutral contexts in which students can apply the constructs of thinking. Through these tasks, we have been able to provide an opportunity for students to demonstrate their ability to transfer the types of thinking beyond the original classroom setting. Once again, we have worked with SCALE to define tasks where students easily access the content but where the cognitive lift requires them to demonstrate their thinking abilities.

These assessments demonstrate that it is possible to capture meaningful data on students’ critical thinking abilities. They are not intended to be high stakes accountability measures. Instead, they are designed to give students, teachers, and school leaders discrete formative data on hard to measure skills.

While it is clearly difficult, and we have not solved all of the challenges to scaling assessments of critical thinking, we can define, teach, and assess these skills . In fact, knowing how important they are for the economy of the future and our democracy, it is essential that we do.

Jeff Heyck-Williams (He, His, Him)

Director of the two rivers learning institute.

Jeff Heyck-Williams is the director of the Two Rivers Learning Institute and a founder of Two Rivers Public Charter School. He has led work around creating school-wide cultures of mathematics, developing assessments of critical thinking and problem-solving, and supporting project-based learning.

Read More About Why Schools Need to Change

AI in Schools Has Prevailed for a Full Year. What Happens Next?

August 13, 2024

Connections over Consequences: Effective Strategies for Collaborative Problem-Solving with Students

Sanchel Hall

August 6, 2024

Incorporating Leadership Skills into a Student-Centered Classroom

Elizabeth Lennon (she, her)

July 8, 2024

IMAGES

VIDEO