- Privacy Policy

Home » Framework Analysis – Method, Types and Examples

Framework Analysis – Method, Types and Examples

Table of Contents

Framework Analysis

Definition:

Framework Analysis is a qualitative research method that involves organizing and analyzing data using a predefined analytical framework. The analytical framework is a set of predetermined themes or categories that are derived from the research questions or objectives. The framework provides a structured approach to data analysis and can help to identify patterns, themes, and relationships in the data.

Steps in Framework Analysis

Here are the general steps in Framework Analysis:

Familiarization

Get familiar with the data by reading and re-reading it. This step helps you to become immersed in the data and to get a sense of its content, structure, and scope.

Identify a Coding Framework

Identify a coding framework or set of themes that will be used to analyze the data. These themes can be derived from existing literature or theories or developed based on the data itself.

Code the data by applying the coding framework to the data. This involves breaking down the data into smaller units and assigning each unit to a particular theme or category.

Chart or summarize the data by creating tables or matrices that display the distribution and frequency of each theme or category across the data set.

Mapping and interpretation

Analyze the data by examining the relationship between different themes or categories, and by exploring the implications and meanings of the findings in relation to the research question.

Verification

Verify the accuracy and validity of the findings by checking them against the original data, comparing them with other sources of data, and seeking feedback from others.

Report the findings by presenting them in a clear, concise, and organized manner. This involves summarizing the key themes, presenting supporting evidence, and providing interpretations and recommendations based on the findings.

Framework Analysis Conducting Guide

Here is a step-by-step guide to conducting framework analysis:

- Define the research question: The first step in conducting framework analysis is to clearly define the research question or objective that you want to investigate.

- Develop the analytical framework: Develop a coding framework or a set of predetermined themes or categories that are relevant to the research question. These themes or categories can be derived from existing literature or theories, or they can be developed based on the data collected.

- Data collection: Collect the data using a suitable method such as interviews, focus groups, surveys or observation.

- Familiarization: Transcribe and familiarize yourself with the data. Read through the data several times and take notes to identify any patterns, themes or issues that are emerging.

- Coding : Code the data by identifying key themes or categories and assigning each piece of information to a specific theme or category.

- Charting: Create charts or tables that display the frequency and distribution of each theme or category. This helps to summarize the data and identify patterns.

- Mapping and interpretation: Analyze the data to identify patterns, relationships, and themes. Interpret the findings in light of the research objectives and provide explanations for any significant patterns or themes that have emerged.

- Validation : Validate the findings by sharing them with others and seeking feedback. This can help to ensure that the findings are robust and reliable.

- Report writing: Write a report that summarizes the findings, includes quotes or examples from the data to support the findings and provides recommendations for future research.

Applications of Framework Analysis

Framework Analysis has a wide range of applications in research, including:

- Policy analysis: Framework Analysis can be used to analyze policies and policy documents to identify key themes, patterns, and underlying assumptions.

- Social science research: Framework Analysis is commonly used in social science research to analyze qualitative data from interviews, focus groups, and other sources.

- Health research: Framework Analysis can be used to analyze qualitative data from health research studies, such as patient and provider perspectives, to identify themes and patterns.

- Environmental research : Framework Analysis can be used to analyze qualitative data from environmental research studies to identify themes and patterns related to environmental attitudes, behaviors, and practices.

- Education research: Framework Analysis can be used to analyze qualitative data from educational research studies to identify themes and patterns related to teaching practices, student learning, and educational policies.

- Market research: Framework Analysis can be used to analyze qualitative data from market research studies to identify themes and patterns related to consumer attitudes, behaviors, and preferences.

Examples of Framework Analysis

Here are some examples of Framework Analysis in various research contexts:

- Health Research: A study on the experiences of cancer survivors might use Framework Analysis to identify themes related to the psychological, social, and physical aspects of survivorship. Themes might include coping strategies, social support, and health outcomes.

- Education Research: A study on the impact of a new teaching approach might use Framework Analysis to identify themes related to the implementation of the approach, the effectiveness of the approach, and barriers to its implementation. Themes might include teacher attitudes, student engagement, and logistical challenges.

- Environmental Research : A study on the factors that influence pro-environmental behaviors might use Framework Analysis to identify themes related to environmental attitudes, behaviors, and practices. Themes might include social norms, personal values, and perceived barriers to behavior change.

- Policy Analysis: A study on the implementation of a new policy might use Framework Analysis to identify themes related to policy development, implementation, and outcomes. Themes might include stakeholder perspectives, organizational structures, and policy effectiveness.

- Social Science Research: A study on the experiences of immigrant families might use Framework Analysis to identify themes related to the challenges and opportunities faced by immigrant families in their new country. Themes might include language barriers, cultural differences, and social support.

When to use Framework Analysis

Framework Analysis is a useful method for analyzing qualitative data when the research questions require an in-depth exploration of a particular phenomenon, concept, or experience. It is particularly useful when:

- The research involves multiple sources of qualitative data, such as interviews, focus groups, or documents, that need to be analyzed and compared.

- The research questions require a systematic and structured approach to data analysis that enables the identification of patterns, themes, and relationships in the data.

- The research involves a large and complex dataset that requires a method for organizing and synthesizing the data in a meaningful way.

- The research aims to generate new insights and understandings from the data, rather than testing pre-existing hypotheses or theories.

- The research requires a method that is transparent, replicable, and verifiable, as Framework Analysis provides a clear framework for data analysis and reporting.

Purpose of Framework Analysis

The purpose of Framework Analysis is to systematically organize and analyze qualitative data in a structured and transparent manner. The method is designed to identify patterns, themes, and relationships in the data that are relevant to the research question or objective. By using a rigorous and transparent approach to data analysis, Framework Analysis enables researchers to generate new insights and understandings from the data, and to provide a clear and structured presentation of the findings.

The method is particularly useful for analyzing large and complex qualitative datasets that require a method for organizing and synthesizing the data in a meaningful way. It can be used to explore a wide range of research questions and objectives across various fields, including health research, social science research, education research, policy analysis, and environmental research, among others.

Overall, the purpose of Framework Analysis is to provide a systematic and transparent method for analyzing qualitative data that enables researchers to generate new insights and understandings from the data in a rigorous and structured manner.

Characteristics of Framework Analysis

Some Characteristics of Framework Analysis are:

- Systematic and Structured Approach: Framework Analysis provides a systematic and structured approach to data analysis that involves a series of steps that are followed in a predetermined order.

- Transparency and Replicability: Framework Analysis emphasizes transparency and replicability, as it involves a clearly defined process for data analysis that can be applied consistently across different datasets and research questions.

- Flexibility : Framework Analysis is flexible and adaptable to a wide range of research contexts and objectives, as it can be used to analyze qualitative data from various sources and to explore different research questions.

- In-depth Exploration of the Data: Framework Analysis enables an in-depth exploration of the data, as it involves a thorough and detailed analysis of the data to identify patterns, themes, and relationships.

- Applicable to Large and Complex Datasets: Framework Analysis is particularly useful for analyzing large and complex qualitative datasets, as it provides a method for organizing and synthesizing the data in a meaningful way.

- Data-Driven: Framework Analysis is data-driven, as it focuses on the analysis and interpretation of the data rather than on pre-existing hypotheses or theories.

- Emphasis on Contextual Understanding : Framework Analysis emphasizes contextual understanding, as it involves a detailed examination of the data to identify the social, cultural, and environmental factors that may influence the phenomena under investigation.

Advantages of Framework Analysis

Some Advantages of Framework Analysis are as follows:

- Transparency : Framework Analysis provides a clear and structured approach to data analysis, which makes the process transparent and easy to follow. This ensures that the findings can be easily replicated or verified by other researchers.

- Thorough Analysis : Framework Analysis enables a thorough and detailed analysis of the data, which allows for the identification of patterns, themes, and relationships that may not be apparent through other methods.

- Contextual Understanding: Framework Analysis emphasizes the importance of understanding the context in which the data was collected, which enables a more nuanced interpretation of the findings.

- Collaborative Analysis: Framework Analysis can be used as a collaborative method for data analysis, as it allows multiple researchers to work together to analyze the data and develop a shared understanding of the findings.

- Efficient and Time-saving: Framework Analysis can be an efficient and time-saving method for analyzing qualitative data, as it provides a structured and organized approach to data analysis that can help researchers manage and synthesize large datasets.

- Comprehensive Reporting: Framework Analysis can help ensure that the research findings are comprehensive and well-reported, as the method provides a clear framework for presenting the results.

Limitations of Framework Analysis

Some Limitations of Framework Analysis are as follows:

- Subjectivity : Framework Analysis relies on the interpretation of the researchers, which can introduce subjectivity into the analysis process.

- Time-consuming : Framework Analysis can be a time-consuming method for data analysis, particularly when working with large and complex datasets.

- Limited ability to generate new theory : Framework Analysis is a deductive approach that relies on pre-existing theories and concepts to guide the analysis, which may limit the ability to generate new theoretical insights.

- Risk of oversimplification: The structured approach of Framework Analysis can lead to oversimplification of the data, as complex issues may be reduced to predefined categories or themes.

- Limited ability to capture the complexity of the data : The predefined categories or themes used in Framework Analysis may not be able to capture the full complexity of the data, particularly when dealing with nuanced or context-specific phenomena.

- Limited use with non-textual data : Framework Analysis is primarily designed for analyzing qualitative textual data and may not be as effective for analyzing non-textual data such as images, videos, or audio recordings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Cluster Analysis – Types, Methods and Examples

Discriminant Analysis – Methods, Types and...

MANOVA (Multivariate Analysis of Variance) –...

Documentary Analysis – Methods, Applications and...

ANOVA (Analysis of variance) – Formulas, Types...

Graphical Methods – Types, Examples and Guide

Framework Analysis: Methods and Use Cases

Introduction

What is framework analysis, implementing the framework analysis methodology.

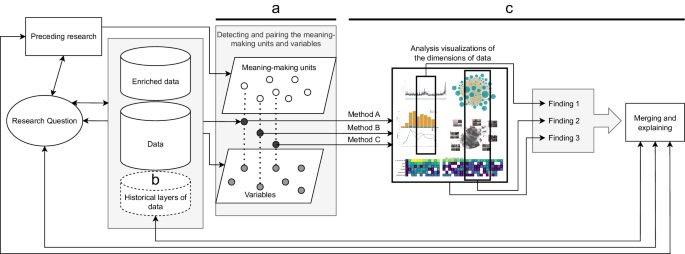

Among qualitative methods in social research, framework analysis stands out as a structured approach to analyzing qualitative data . Originally developed for applied policy analysis and multi-disciplinary health research, this method has found application in various domains due to its emphasis on transparency and systematic data analysis. As with other research methods, the objective remains to extract meaningful themes and patterns, but the framework method provides a specific roadmap for doing so.

Whether you're a seasoned researcher or someone new to the realm of qualitative methodology, understanding the nuances of framework analysis can enhance the depth and rigor of your research efforts. In this article, we will explore the methods and use cases of framework analysis, diving deep into its benefits and the analytical framework it enables researchers to develop.

Framework analysis is a systematic approach for analyzing qualitative data . Rooted in the traditions of social research relevant to policy making, it was found to be a useful tool for analysis in multi-disciplinary health research where the eventual analysis of qualitative data can identify themes and actionable insights relevant to policy outcomes.

Unlike some other qualitative analysis methods , framework analysis is explicitly focused on addressing specific research questions , making it particularly suitable for applied or policy-related qualitative research .

Purpose of framework analysis

The primary aim of framework analysis is to offer a clear and transparent process for conducting qualitative research by managing, reducing, and analyzing large datasets without losing sight of the original context. Given the vast amounts of data often generated in qualitative studies, having a systematic method to sift through this data is crucial.

By using the framework method, researchers can remain focused on their research questions while ensuring that the data collection and analysis process retains its integrity and depth.

Characteristics of framework analysis

Transparent structure: One of the distinct features of framework analysis is its emphasis on transparency . Every step in the analysis process is documented, allowing for easy scrutiny and replication by multiple researchers.

Thematic framework: Central to framework analysis is the development of a framework identifying key themes, concepts, and relationships in the data. The framework guides the subsequent stages of coding and charting.

Flexibility: While it provides a clear structure, framework analysis is also adaptable. Depending on the objectives of the study, researchers can modify the process to better suit their data and questions.

Iterative process: The process in framework analysis is not linear. As data is collected and data analysis progresses, researchers often revisit earlier stages, refining the framework or revising codes to better capture the nuances in the data.

Benefits of framework analysis

Conducting framework analysis has several advantages:

Rigorous data management: The structured approach means data is managed and analyzed with a high level of rigor, minimizing the potential influence of preconceptions.

Inclusivity: Framework analysis accommodates both a priori issues, driven by the research questions , and emergent issues that arise from the data itself.

Comparability: Given its structured nature, framework analysis allows researchers to compare and contrast data, facilitating the identification of patterns and differences.

Accessibility: By presenting data in a summarized, charted form , findings from framework analysis become more accessible and comprehensible, aiding in reporting and disseminating results.

Relevance for applied research: Given its origins in policy research and its clear focus on addressing specific research questions, framework analysis is particularly relevant for studies aiming to inform policy or practice.

Efficient, easy data analysis with ATLAS.ti

Start analyzing data quickly and more deeply with ATLAS.ti. Download a free trial today.

Successfully conducting framework analysis involves a series of structured steps. Proper implementation of framework analysis not only ensures the rigor of a qualitative analysis but also that the findings are credible and meaningful.

Familiarization with the data

Before discussing a more detailed analysis, it's paramount to understand the breadth and depth of the data at hand.

Reading and re-reading: Begin by reading textual data such as transcripts , field notes , and other data sources multiple times. This immersion allows researchers to understand participants' perspectives and grasp the overall context.

Noting preliminary ideas: As researchers familiarize themselves with the data, preliminary themes or ideas may start to emerge. Jotting these down in memos helps in forming an initial understanding and can be instrumental in the subsequent phase of developing a set of themes.

Developing a thematic framework

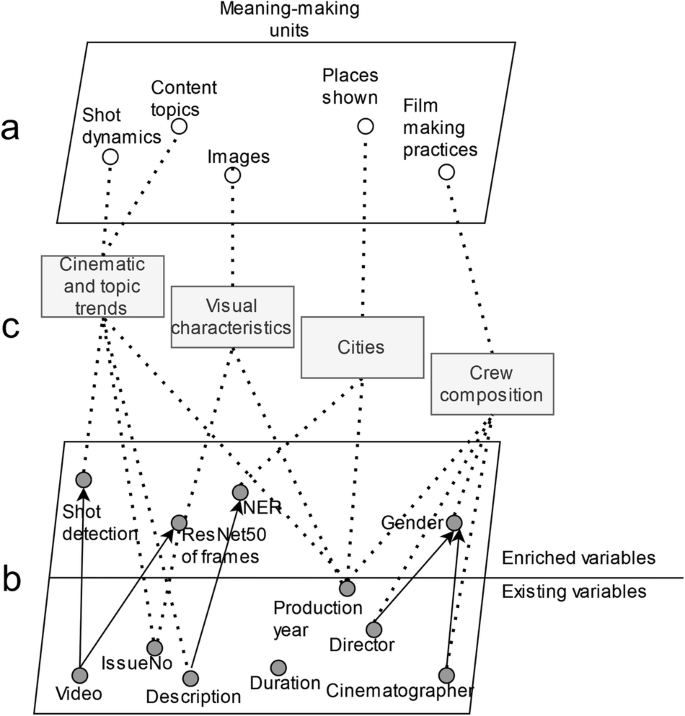

As is the case across nearly all types of qualitative methodology , central to framework analysis is the construction of a robust analytical framework . This structure aids in organizing and interpreting the data .

Identifying key themes: Based on the initial familiarization, it's important to identify themes that occur in the multimedia or textual data. These themes should be relevant to the research question . Researchers can begin assigning codes to specific chunks of data to capture emerging themes.

Categorizing and coding: Each identified theme can further be broken down into sub-themes or brought together under categories. At this stage, researchers can continue coding (or recoding ) their data according to these themes or categories.

Refining the framework: As the analysis progresses, the initial themes represented by your coding framework may need adjustments. It's an iterative process, where the framework can be continually refined to better fit the data.

Indexing and charting the data

Once the framework is established, the next phase involves systematically applying it to the data.

Indexing: Using the resulting coding framework , you can verify that codes have been systematically assigned to relevant portions of the data. This ensures every relevant piece of data is categorized under the appropriate theme or sub-theme.

Charting: This step involves creating charts or matrices for each theme. Data from different sources (like interviews or focus groups ) is summarized under the relevant theme. For example, a table can be created with each theme in a column and each data source in a row, and researchers can then populate the cells with relevant data extracts or notes. These charts provide a visual representation , allowing researchers to easily see patterns or discrepancies in the data.

Mapping and Interpretation: With the data systematically charted, researchers can begin to map the relationships between themes and interpret the broader implications. This step is where the true essence of the research emerges, as researchers link the patterns in the data to the broader objectives of the study.

Framework analysis is an involved process, with intentional decision-making at every step of the way. As a result, implementing structured qualitative methodologies such as framework analysis requires patience, meticulous attention to detail, and a clear understanding of the research objectives. When conducted diligently, it offers a transparent and systematic approach to analyzing qualitative data , ensuring the research not only has depth but also clarity.

Whether comparing data across multiple sources or drilling down into the nuances of individual narratives, framework analysis equips researchers with the tools needed to derive meaningful insights from their qualitative data . As more researchers across disciplines recognize its value, it stands to become an even more integral part of the research landscape.

Systematic data analysis made easy with ATLAS.ti

Powerful tools to analyze qualitative data are right at your fingertips. Download your free trial today.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Using framework-based synthesis for conducting reviews of qualitative studies

Mary dixon-woods.

1 Social Science Research Group, Department of Health Sciences, School of Medicine, University of Leicester, Leicester, UK

Framework analysis is a technique used for data analysis in primary qualitative research. Recent years have seen its being adapted to conduct syntheses of qualitative studies. Framework-based synthesis shows considerable promise in addressing applied policy questions. An innovation in the approach, known as 'best fit' framework synthesis, has been published in BMC Medical Research Methodology this month. It involves reviewers in choosing a conceptual model likely to be suitable for the question of the review, and using it as the basis of their initial coding framework. This framework is then modified in response to the evidence reported in the studies in the reviews, so that the final product is a revised framework that may include both modified factors and new factors that were not anticipated in the original model. 'Best fit' framework-based synthesis may be especially suitable in addressing urgent policy questions where the need for a more fully developed synthesis is balanced by the need for a quick answer.

Please see related article: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2288/11/29 .

Introduction

As the appetite for more holistic overviews of research evidence has grown, the last 10-15 years have seen increasing interest and activity directed at developing methods for synthesising qualitative studies [ 1 ]. Some of these methods might be fairly described as 'new' techniques that have been developed specifically for the purpose of conducting synthesis, while others might more properly be seen as adaptations of approaches that were originally intended for primary research [ 2 ]. Framework analysis is one of the latter. Developed during the 1980s by the UK-based National Centre for Social Research, and explicitly oriented towards applied policy questions, framework analysis is a matrix-based method involving the construction of thematic categories into which data can be coded [ 3 ]. One important feature of the approach is that, unlike some other qualitative methods, it allows themes or concepts identified a priori to be specified as coding categories from the outset, and to be combined with other themes or concepts that emerge de novo by subjecting the data to inductive analysis. A practical benefit of doing this is that it enables questions or issues identified in advance by various stakeholders (such as policymakers, practitioners, or user groups) to be explicitly and systematically considered in the analysis, while also facilitating enough flexibility to detect and characterise issues that emerge from the data.

Framework analysis has become hugely popular as a way of conducting analysis of primary qualitative data, especially in areas of healthcare with policy relevance. A recent study, for example, used framework analysis in a study of mothers' interpretations of dietary recommendations [ 4 ]. Because the study had been guided by social learning theory, and because the researchers were interested in comparing dietary beliefs and behaviours across social classes, the ability of framework analysis to cope with categories specified in advance of the data collection made it a very appropriate choice of analytic strategy. A further advantage is the use of charting techniques, which help not only in enhancing the transparency of coding, but also with teamwork in relation to analysis. Many of the properties that make framework analysis an appealing option for those conducting primary research make 'framework-based synthesis' a potentially equally attractive option for those seeking to conduct a synthesis of studies. A new article by Carroll et al [ 5 ] published this month in BMC Medical Research methodology reports an interesting evolution of the framework-based synthesis approach.

Framework analysis has previously been adapted for use in synthesis of qualitative evidence by Oliver and colleagues [ 6 ], who developed a multidimensional framework for analysing public involvement in health services research. They employed an iterative process involving familiarization with the literature, gradually developing a conceptual framework based on concepts derived from the review question and the theoretical and empirical literature, applying the framework systematically to evidence from the studies included in the review, and constructing a chart for each key dimension with distilled summaries from all relevant documents. The charts were used to map the range and nature of public involvement and to find associations between themes. Several benefits of this approach were noted by Oliver et al ., including widening the scope of the review to include relevant topics identified by lay people, and the creation of data displays that could be viewed and assessed by people other than the primary analyst. Other examples of the application of the framework approach to the conduct of synthesis have now begun to appear, though it is dismaying that these and other syntheses of qualitative evidence continue to label themselves with the confusing, tautological, and inappropriate term 'meta-synthesis' [ 7 ].

In the recent BMC Medical Research Methodology manuscript [ 5 ], Carroll and colleagues develop the framework-based synthesis approach, focusing on the views of adults taking chemopreventative agents (such as aspirin or vitamins) in an effort to prevent colorectal cancer. One of the novel features of their approach is their use of a conceptual model that was used as an initial starting point for coding the evidence from 20 studies. This conceptual model was chosen because of its broad applicability to the area under review, and the authors did not engage in the more lengthy process of model specification that is often more characteristic of framework synthesis. They augmented analysis using this prespecified model with analysis that was more inductive, and ended up generating a revised conceptual model that provided a 'best fit' to the evidence reported in the studies they reviewed. The revised model included some factors that were absent from the original model, as well as adjustments to factors that had been reported in that model.

Carroll and colleagues emphasise the advantages of this kind of approach when time is short and the demand for policy-relevant evidence is urgent. It enables focusing of the research on the priorities of those commissioning the work, while still leaving some room for finding the 'best fit' in the light of what the evidence actually reports. Of course, like framework analysis for primary research [ 8 ] there are downsides of the approach too. Reviewers who have made a hefty investment in an initial conceptual model may be unconsciously motivated to recover the sunk costs of that model, and as a consequence tend to neglect evidence that presents a fundamental challenge. Putting more time into specifying the model, using a wider range of literature, and gaining the views of a wider range of stakeholders may all be important in improving the legitimacy and validity of any ensuring synthesis. There are also the usual risks of framework analysis that it can tend to suppress interpretive creativity, and thus reduce some of the vividness of insight seen in the best qualitative research. Nonetheless, as Carroll and colleagues argue, framework-based synthesis using the 'best fit' strategy is, in the right hands, likely to be a highly pragmatic and useful approach for a range of policy urgent questions.

Conclusions

Framework-based synthesis is an important advance in conducting reviews of qualitative synthesis. The 'best fit' strategy is a variant of this approach that may be very helpful when policymakers, practitioners or other decision makers need answers quickly, and are able to tolerate some ambiguity about whether the answer is the very best that could be given.

Competing interests

The author declares that they have no competing interests.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/9/39/prepub

- Barnett-Page E, Thomas J. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009; 9 :59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-59. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dixon-Woods M, Agarwal S, Jones D, Young B, Sutton A. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. J Health Serv Res Pol. 2005; 10 :45–53. doi: 10.1258/1355819052801804. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ritchie J, Spencer L. In: Analyzing Qualitative Data. Bryman A, Burgess RG, editor. London: Routledge; 1994. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wood F, Robling M, Prout H, Kinnersley P, Houston H, Butler C. A question of balance: a qualitative study of mothers' interpretations of dietary recommendations. Ann Fam Med. 2010; 8 :51–57. doi: 10.1370/afm.1072. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carroll C, Booth A, Cooper K. A worked example of "best fit" framework synthesis: a systematic review of views concerning the taking of some potential chemopreventive agents. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011; 11 :29. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-29. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Oliver S, Rees R, Clarke-Jones L, Milne R, Oakley AR, Gabbay J, Stein K, Buchanan P, Gyte G. A multidimensional conceptual framework for analysing public involvement in health services research. Health Exp. 2008; 11 :72–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2007.00476.x. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Seymour C, Addington-Hall J, Lucassen AM, Foster CL. What facilitates or impedes family communication following genetic testing for cancer risk? A systematic review and meta-synthesis of primary qualitative research. J Genet Couns. 2010; 19 :330–342. doi: 10.1007/s10897-010-9296-y. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Barbour R. The newfound credibility of qualitative research? Tales of technical essentialism and cooption. Qual Health Res. 2003; 13 :1019–1027. doi: 10.1177/1049732303253331. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

Using Framework Analysis in nursing research: a worked example

Affiliation.

- 1 School of Nursing, Midwifery & Social Work, University of Manchester, UK.

- PMID: 23517523

- DOI: 10.1111/jan.12127

Aims: To demonstrate Framework Analysis using a worked example and to illustrate how criticisms of qualitative data analysis including issues of clarity and transparency can be addressed.

Background: Critics of the analysis of qualitative data sometimes cite lack of clarity and transparency about analytical procedures; this can deter nurse researchers from undertaking qualitative studies. Framework Analysis is flexible, systematic, and rigorous, offering clarity, transparency, an audit trail, an option for theme-based and case-based analysis and for readily retrievable data. This paper offers further explanation of the process undertaken which is illustrated with a worked example.

Data source and research design: Data were collected from 31 nursing students in 2009 using semi-structured interviews.

Discussion: The data collected are not reported directly here but used as a worked example for the five steps of Framework Analysis. Suggestions are provided to guide researchers through essential steps in undertaking Framework Analysis. The benefits and limitations of Framework Analysis are discussed.

Implications for nursing: Nurses increasingly use qualitative research methods and need to use an analysis approach that offers transparency and rigour which Framework Analysis can provide. Nurse researchers may find the detailed critique of Framework Analysis presented in this paper a useful resource when designing and conducting qualitative studies.

Conclusion: Qualitative data analysis presents challenges in relation to the volume and complexity of data obtained and the need to present an 'audit trail' for those using the research findings. Framework Analysis is an appropriate, rigorous and systematic method for undertaking qualitative analysis.

Keywords: Framework Analysis; nursing; qualitative data analysis.

© 2013 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Publication types

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Nursing Research / methods*

- Nursing Research / statistics & numerical data

- Qualitative Research*

- Statistics as Topic / methods*

- Correspondence

- Open access

- Published: 18 September 2013

Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research

- Nicola K Gale 1 ,

- Gemma Heath 2 ,

- Elaine Cameron 3 ,

- Sabina Rashid 4 &

- Sabi Redwood 2

BMC Medical Research Methodology volume 13 , Article number: 117 ( 2013 ) Cite this article

515k Accesses

4724 Citations

82 Altmetric

Metrics details

The Framework Method is becoming an increasingly popular approach to the management and analysis of qualitative data in health research. However, there is confusion about its potential application and limitations.

The article discusses when it is appropriate to adopt the Framework Method and explains the procedure for using it in multi-disciplinary health research teams, or those that involve clinicians, patients and lay people. The stages of the method are illustrated using examples from a published study.

Used effectively, with the leadership of an experienced qualitative researcher, the Framework Method is a systematic and flexible approach to analysing qualitative data and is appropriate for use in research teams even where not all members have previous experience of conducting qualitative research.

The Framework Method for the management and analysis of qualitative data has been used since the 1980s [ 1 ]. The method originated in large-scale social policy research but is becoming an increasingly popular approach in medical and health research; however, there is some confusion about its potential application and limitations. In this article we discuss when it is appropriate to use the Framework Method and how it compares to other qualitative analysis methods. In particular, we explore how it can be used in multi-disciplinary health research teams. Multi-disciplinary and mixed methods studies are becoming increasingly commonplace in applied health research. As well as disciplines familiar with qualitative research, such as nursing, psychology and sociology, teams often include epidemiologists, health economists, management scientists and others. Furthermore, applied health research often has clinical representation and, increasingly, patient and public involvement [ 2 ]. We argue that while leadership is undoubtedly required from an experienced qualitative methodologist, non-specialists from the wider team can and should be involved in the analysis process. We then present a step-by-step guide to the application of the Framework Method, illustrated using a worked example (See Additional File 1 ) from a published study [ 3 ] to illustrate the main stages of the process. Technical terms are included in the glossary (below). Finally, we discuss the strengths and limitations of the approach.

Glossary of key terms used in the Framework Method

Analytical framework: A set of codes organised into categories that have been jointly developed by researchers involved in analysis that can be used to manage and organise the data. The framework creates a new structure for the data (rather than the full original accounts given by participants) that is helpful to summarize/reduce the data in a way that can support answering the research questions.

Analytic memo: A written investigation of a particular concept, theme or problem, reflecting on emerging issues in the data that captures the analytic process (see Additional file 1 , Section 7).

Categories: During the analysis process, codes are grouped into clusters around similar and interrelated ideas or concepts. Categories and codes are usually arranged in a tree diagram structure in the analytical framework. While categories are closely and explicitly linked to the raw data, developing categories is a way to start the process of abstraction of the data (i.e. towards the general rather than the specific or anecdotal).

Charting: Entering summarized data into the Framework Method matrix (see Additional File 1 , Section 6).

Code: A descriptive or conceptual label that is assigned to excerpts of raw data in a process called ‘coding’ (see Additional File 1 , Section 3).

Data: Qualitative data usually needs to be in textual form before analysis. These texts can either be elicited texts (written specifically for the research, such as food diaries), or extant texts (pre-existing texts, such as meeting minutes, policy documents or weblogs), or can be produced by transcribing interview or focus group data, or creating ‘field’ notes while conducting participant-observation or observing objects or social situations.

Indexing: The systematic application of codes from the agreed analytical framework to the whole dataset (see Additional File 1 , Section 5).

Matrix: A spreadsheet contains numerous cells into which summarized data are entered by codes (columns) and cases (rows) (see Additional File 1 , Section 6).

Themes: Interpretive concepts or propositions that describe or explain aspects of the data, which are the final output of the analysis of the whole dataset. Themes are articulated and developed by interrogating data categories through comparison between and within cases. Usually a number of categories would fall under each theme or sub-theme [ 3 ].

Transcript: A written verbatim (word-for-word) account of a verbal interaction, such as an interview or conversation.

The Framework Method sits within a broad family of analysis methods often termed thematic analysis or qualitative content analysis. These approaches identify commonalities and differences in qualitative data, before focusing on relationships between different parts of the data, thereby seeking to draw descriptive and/or explanatory conclusions clustered around themes. The Framework Method was developed by researchers, Jane Ritchie and Liz Spencer, from the Qualitative Research Unit at the National Centre for Social Research in the United Kingdom in the late 1980s for use in large-scale policy research [ 1 ]. It is now used widely in other areas, including health research [ 3 – 12 ]. Its defining feature is the matrix output: rows (cases), columns (codes) and ‘cells’ of summarised data, providing a structure into which the researcher can systematically reduce the data, in order to analyse it by case and by code [ 1 ]. Most often a ‘case’ is an individual interviewee, but this can be adapted to other units of analysis, such as predefined groups or organisations. While in-depth analyses of key themes can take place across the whole data set, the views of each research participant remain connected to other aspects of their account within the matrix so that the context of the individual’s views is not lost. Comparing and contrasting data is vital to qualitative analysis and the ability to compare with ease data across cases as well as within individual cases is built into the structure and process of the Framework Method.

The Framework Method provides clear steps to follow and produces highly structured outputs of summarised data. It is therefore useful where multiple researchers are working on a project, particularly in multi-disciplinary research teams were not all members have experience of qualitative data analysis, and for managing large data sets where obtaining a holistic, descriptive overview of the entire data set is desirable. However, caution is recommended before selecting the method as it is not a suitable tool for analysing all types of qualitative data or for answering all qualitative research questions, nor is it an ‘easy’ version of qualitative research for quantitative researchers. Importantly, the Framework Method cannot accommodate highly heterogeneous data, i.e. data must cover similar topics or key issues so that it is possible to categorize it. Individual interviewees may, of course, have very different views or experiences in relation to each topic, which can then be compared and contrasted. The Framework Method is most commonly used for the thematic analysis of semi-structured interview transcripts, which is what we focus on in this article, although it could, in principle, be adapted for other types of textual data [ 13 ], including documents, such as meeting minutes or diaries [ 12 ], or field notes from observations [ 10 ].

For quantitative researchers working with qualitative colleagues or when exploring qualitative research for the first time, the nature of the Framework Method is seductive because its methodical processes and ‘spreadsheet’ approach seem more closely aligned to the quantitative paradigm [ 14 ]. Although the Framework Method is a highly systematic method of categorizing and organizing what may seem like unwieldy qualitative data, it is not a panacea for problematic issues commonly associated with qualitative data analysis such as how to make analytic choices and make interpretive strategies visible and auditable. Qualitative research skills are required to appropriately interpret the matrix, and facilitate the generation of descriptions, categories, explanations and typologies. Moreover, reflexivity, rigour and quality are issues that are requisite in the Framework Method just as they are in other qualitative methods. It is therefore essential that studies using the Framework Method for analysis are overseen by an experienced qualitative researcher, though this does not preclude those new to qualitative research from contributing to the analysis as part of a wider research team.

There are a number of approaches to qualitative data analysis, including those that pay close attention to language and how it is being used in social interaction such as discourse analysis [ 15 ] and ethnomethodology [ 16 ]; those that are concerned with experience, meaning and language such as phenomenology [ 17 , 18 ] and narrative methods [ 19 ]; and those that seek to develop theory derived from data through a set of procedures and interconnected stages such as Grounded Theory [ 20 , 21 ]. Many of these approaches are associated with specific disciplines and are underpinned by philosophical ideas which shape the process of analysis [ 22 ]. The Framework Method, however, is not aligned with a particular epistemological, philosophical, or theoretical approach. Rather it is a flexible tool that can be adapted for use with many qualitative approaches that aim to generate themes.

The development of themes is a common feature of qualitative data analysis, involving the systematic search for patterns to generate full descriptions capable of shedding light on the phenomenon under investigation. In particular, many qualitative approaches use the ‘constant comparative method’ , developed as part of Grounded Theory, which involves making systematic comparisons across cases to refine each theme [ 21 , 23 ]. Unlike Grounded Theory, the Framework Method is not necessarily concerned with generating social theory, but can greatly facilitate constant comparative techniques through the review of data across the matrix.

Perhaps because the Framework Method is so obviously systematic, it has often, as other commentators have noted, been conflated with a deductive approach to qualitative analysis [ 13 , 14 ]. However, the tool itself has no allegiance to either inductive or deductive thematic analysis; where the research sits along this inductive-deductive continuum depends on the research question. A question such as, ‘Can patients give an accurate biomedical account of the onset of their cardiovascular disease?’ is essentially a yes/no question (although it may be nuanced by the extent of their account or by appropriate use of terminology) and so requires a deductive approach to both data collection and analysis (e.g. structured or semi-structured interviews and directed qualitative content analysis [ 24 ]). Similarly, a deductive approach may be taken if basing analysis on a pre-existing theory, such as behaviour change theories, for example in the case of a research question such as ‘How does the Theory of Planned Behaviour help explain GP prescribing?’ [ 11 ]. However, a research question such as, ‘How do people construct accounts of the onset of their cardiovascular disease?’ would require a more inductive approach that allows for the unexpected, and permits more socially-located responses [ 25 ] from interviewees that may include matters of cultural beliefs, habits of food preparation, concepts of ‘fate’, or links to other important events in their lives, such as grief, which cannot be predicted by the researcher in advance (e.g. an interviewee-led open ended interview and grounded theory [ 20 ]). In all these cases, it may be appropriate to use the Framework Method to manage the data. The difference would become apparent in how themes are selected: in the deductive approach, themes and codes are pre-selected based on previous literature, previous theories or the specifics of the research question; whereas in the inductive approach, themes are generated from the data though open (unrestricted) coding, followed by refinement of themes. In many cases, a combined approach is appropriate when the project has some specific issues to explore, but also aims to leave space to discover other unexpected aspects of the participants’ experience or the way they assign meaning to phenomena. In sum, the Framework Method can be adapted for use with deductive, inductive, or combined types of qualitative analysis. However, there are some research questions where analysing data by case and theme is not appropriate and so the Framework Method should be avoided. For instance, depending on the research question, life history data might be better analysed using narrative analysis [ 19 ]; recorded consultations between patients and their healthcare practitioners using conversation analysis [ 26 ]; and documentary data, such as resources for pregnant women, using discourse analysis [ 27 ].

It is not within the scope of this paper to consider study design or data collection in any depth, but before moving on to describe the Framework Method analysis process, it is worth taking a step back to consider briefly what needs to happen before analysis begins. The selection of analysis method should have been considered at the proposal stage of the research and should fit with the research questions and overall aims of the study. Many qualitative studies, particularly ones using inductive analysis, are emergent in nature; this can be a challenge and the researchers can only provide an “imaginative rehearsal” of what is to come [ 28 ]. In mixed methods studies, the role of the qualitative component within the wider goals of the project must also be considered. In the data collection stage, resources must be allocated for properly trained researchers to conduct the qualitative interviewing because it is a highly skilled activity. In some cases, a research team may decide that they would like to use lay people, patients or peers to do the interviews [ 29 – 32 ] and in this case they must be properly trained and mentored which requires time and resources. At this early stage it is also useful to consider whether the team will use Computer Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software (CAQDAS), which can assist with data management and analysis.

As any form of qualitative or quantitative analysis is not a purely technical process, but influenced by the characteristics of the researchers and their disciplinary paradigms, critical reflection throughout the research process is paramount, including in the design of the study, the construction or collection of data, and the analysis. All members of the team should keep a research diary, where they record reflexive notes, impressions of the data and thoughts about analysis throughout the process. Experienced qualitative researchers become more skilled at sifting through data and analysing it in a rigorous and reflexive way. They cannot be too attached to certainty, but must remain flexible and adaptive throughout the research in order to generate rich and nuanced findings that embrace and explain the complexity of real social life and can be applied to complex social issues. It is important to remember when using the Framework Method that, unlike quantitative research where data collection and data analysis are strictly sequential and mutually exclusive stages of the research process, in qualitative analysis there is, to a greater or lesser extent depending on the project, ongoing interplay between data collection, analysis, and theory development. For example, new ideas or insights from participants may suggest potentially fruitful lines of enquiry, or close analysis might reveal subtle inconsistencies in an account which require further exploration.

Procedure for analysis

Stage 1: transcription.

A good quality audio recording and, ideally, a verbatim (word for word) transcription of the interview is needed. For Framework Method analysis, it is not necessarily important to include the conventions of dialogue transcriptions which can be difficult to read (e.g. pauses or two people talking simultaneously), because the content is what is of primary interest. Transcripts should have large margins and adequate line spacing for later coding and making notes. The process of transcription is a good opportunity to become immersed in the data and is to be strongly encouraged for new researchers. However, in some projects, the decision may be made that it is a better use of resources to outsource this task to a professional transcriber.

Stage 2: Familiarisation with the interview

Becoming familiar with the whole interview using the audio recording and/or transcript and any contextual or reflective notes that were recorded by the interviewer is a vital stage in interpretation. It can also be helpful to re-listen to all or parts of the audio recording. In multi-disciplinary or large research projects, those involved in analysing the data may be different from those who conducted or transcribed the interviews, which makes this stage particularly important. One margin can be used to record any analytical notes, thoughts or impressions.

Stage 3: Coding

After familiarization, the researcher carefully reads the transcript line by line, applying a paraphrase or label (a ‘code’) that describes what they have interpreted in the passage as important. In more inductive studies, at this stage ‘open coding’ takes place, i.e. coding anything that might be relevant from as many different perspectives as possible. Codes could refer to substantive things (e.g. particular behaviours, incidents or structures), values (e.g. those that inform or underpin certain statements, such as a belief in evidence-based medicine or in patient choice), emotions (e.g. sorrow, frustration, love) and more impressionistic/methodological elements (e.g. interviewee found something difficult to explain, interviewee became emotional, interviewer felt uncomfortable) [ 33 ]. In purely deductive studies, the codes may have been pre-defined (e.g. by an existing theory, or specific areas of interest to the project) so this stage may not be strictly necessary and you could just move straight onto indexing, although it is generally helpful even if you are taking a broadly deductive approach to do some open coding on at least a few of the transcripts to ensure important aspects of the data are not missed. Coding aims to classify all of the data so that it can be compared systematically with other parts of the data set. At least two researchers (or at least one from each discipline or speciality in a multi-disciplinary research team) should independently code the first few transcripts, if feasible. Patients, public involvement representatives or clinicians can also be productively involved at this stage, because they can offer alternative viewpoints thus ensuring that one particular perspective does not dominate. It is vital in inductive coding to look out for the unexpected and not to just code in a literal, descriptive way so the involvement of people from different perspectives can aid greatly in this. As well as getting a holistic impression of what was said, coding line-by-line can often alert the researcher to consider that which may ordinarily remain invisible because it is not clearly expressed or does not ‘fit’ with the rest of the account. In this way the developing analysis is challenged; to reconcile and explain anomalies in the data can make the analysis stronger. Coding can also be done digitally using CAQDAS, which is a useful way to keep track automatically of new codes. However, some researchers prefer to do the early stages of coding with a paper and pen, and only start to use CAQDAS once they reach Stage 5 (see below).

Stage 4: Developing a working analytical framework

After coding the first few transcripts, all researchers involved should meet to compare the labels they have applied and agree on a set of codes to apply to all subsequent transcripts. Codes can be grouped together into categories (using a tree diagram if helpful), which are then clearly defined. This forms a working analytical framework. It is likely that several iterations of the analytical framework will be required before no additional codes emerge. It is always worth having an ‘other’ code under each category to avoid ignoring data that does not fit; the analytical framework is never ‘final’ until the last transcript has been coded.

Stage 5: Applying the analytical framework

The working analytical framework is then applied by indexing subsequent transcripts using the existing categories and codes. Each code is usually assigned a number or abbreviation for easy identification (and so the full names of the codes do not have to be written out each time) and written directly onto the transcripts. Computer Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software (CAQDAS) is particularly useful at this stage because it can speed up the process and ensures that, at later stages, data is easily retrievable. It is worth noting that unlike software for statistical analyses, which actually carries out the calculations with the correct instruction, putting the data into a qualitative analysis software package does not analyse the data; it is simply an effective way of storing and organising the data so that they are accessible for the analysis process.

Stage 6: Charting data into the framework matrix

Qualitative data are voluminous (an hour of interview can generate 15–30 pages of text) and being able to manage and summarize (reduce) data is a vital aspect of the analysis process. A spreadsheet is used to generate a matrix and the data are ‘charted’ into the matrix. Charting involves summarizing the data by category from each transcript. Good charting requires an ability to strike a balance between reducing the data on the one hand and retaining the original meanings and ‘feel’ of the interviewees’ words on the other. The chart should include references to interesting or illustrative quotations. These can be tagged automatically if you are using CAQDAS to manage your data (N-Vivo version 9 onwards has the capability to generate framework matrices), or otherwise a capital ‘Q’, an (anonymized) transcript number, page and line reference will suffice. It is helpful in multi-disciplinary teams to compare and contrast styles of summarizing in the early stages of the analysis process to ensure consistency within the team. Any abbreviations used should be agreed by the team. Once members of the team are familiar with the analytical framework and well practised at coding and charting, on average, it will take about half a day per hour-long transcript to reach this stage. In the early stages, it takes much longer.

Stage 7: Interpreting the data

It is useful throughout the research to have a separate note book or computer file to note down impressions, ideas and early interpretations of the data. It may be worth breaking off at any stage to explore an interesting idea, concept or potential theme by writing an analytic memo [ 20 , 21 ] to then discuss with other members of the research team, including lay and clinical members. Gradually, characteristics of and differences between the data are identified, perhaps generating typologies, interrogating theoretical concepts (either prior concepts or ones emerging from the data) or mapping connections between categories to explore relationships and/or causality. If the data are rich enough, the findings generated through this process can go beyond description of particular cases to explanation of, for example, reasons for the emergence of a phenomena, predicting how an organisation or other social actor is likely to instigate or respond to a situation, or identifying areas that are not functioning well within an organisation or system. It is worth noting that this stage often takes longer than anticipated and that any project plan should ensure that sufficient time is allocated to meetings and individual researcher time to conduct interpretation and writing up of findings (see Additional file 1 , Section 7).

The Framework Method has been developed and used successfully in research for over 25 years, and has recently become a popular analysis method in qualitative health research. The issue of how to assess quality in qualitative research has been highly debated [ 20 , 34 – 40 ], but ensuring rigour and transparency in analysis is a vital component. There are, of course, many ways to do this but in the Framework Method the following are helpful:

Summarizing the data during charting, as well as being a practical way to reduce the data, means that all members of a multi-disciplinary team, including lay, clinical and (quantitative) academic members can engage with the data and offer their perspectives during the analysis process without necessarily needing to read all the transcripts or be involved in the more technical parts of analysis.

Charting also ensures that researchers pay close attention to describing the data using each participant’s own subjective frames and expressions in the first instance, before moving onto interpretation.

The summarized data is kept within the wider context of each case, thereby encouraging thick description that pays attention to complex layers of meaning and understanding [ 38 ].

The matrix structure is visually straightforward and can facilitate recognition of patterns in the data by any member of the research team, including through drawing attention to contradictory data, deviant cases or empty cells.

The systematic procedure (described in this article) makes it easy to follow, even for multi-disciplinary teams and/or with large data sets.

It is flexible enough that non-interview data (such as field notes taken during the interview or reflexive considerations) can be included in the matrix.

It is not aligned with a particular epistemological viewpoint or theoretical approach and therefore can be adapted for use in inductive or deductive analysis or a combination of the two (e.g. using pre-existing theoretical constructs deductively, then revising the theory with inductive aspects; or using an inductive approach to identify themes in the data, before returning to the literature and using theories deductively to help further explain certain themes).

It is easy to identify relevant data extracts to illustrate themes and to check whether there is sufficient evidence for a proposed theme.

Finally, there is a clear audit trail from original raw data to final themes, including the illustrative quotes.

There are also a number of potential pitfalls to this approach:

The systematic approach and matrix format, as we noted in the background, is intuitively appealing to those trained quantitatively but the ‘spreadsheet’ look perhaps further increases the temptation for those without an in-depth understanding of qualitative research to attempt to quantify qualitative data (e.g. “13 out of 20 participants said X). This kind of statement is clearly meaningless because the sampling in qualitative research is not designed to be representative of a wider population, but purposive to capture diversity around a phenomenon [ 41 ].

Like all qualitative analysis methods, the Framework Method is time consuming and resource-intensive. When involving multiple stakeholders and disciplines in the analysis and interpretation of the data, as is good practice in applied health research, the time needed is extended. This time needs to be factored into the project proposal at the pre-funding stage.

There is a high training component to successfully using the method in a new multi-disciplinary team. Depending on their role in the analysis, members of the research team may have to learn how to code, index, and chart data, to think reflexively about how their identities and experience affect the analysis process, and/or they may have to learn about the methods of generalisation (i.e. analytic generalisation and transferability, rather than statistical generalisation [ 41 ]) to help to interpret legitimately the meaning and significance of the data.

While the Framework Method is amenable to the participation of non-experts in data analysis, it is critical to the successful use of the method that an experienced qualitative researcher leads the project (even if the overall lead for a large mixed methods study is a different person). The qualitative lead would ideally be joined by other researchers with at least some prior training in or experience of qualitative analysis. The responsibilities of the lead qualitative researcher are: to contribute to study design, project timelines and resource planning; to mentor junior qualitative researchers; to train clinical, lay and other (non-qualitative) academics to contribute as appropriate to the analysis process; to facilitate analysis meetings in a way that encourages critical and reflexive engagement with the data and other team members; and finally to lead the write-up of the study.

We have argued that Framework Method studies can be conducted by multi-disciplinary research teams that include, for example, healthcare professionals, psychologists, sociologists, economists, and lay people/service users. The inclusion of so many different perspectives means that decision-making in the analysis process can be very time consuming and resource-intensive. It may require extensive, reflexive and critical dialogue about how the ideas expressed by interviewees and identified in the transcript are related to pre-existing concepts and theories from each discipline, and to the real ‘problems’ in the health system that the project is addressing. This kind of team effort is, however, an excellent forum for driving forward interdisciplinary collaboration, as well as clinical and lay involvement in research, to ensure that ‘the whole is greater than the sum of the parts’, by enhancing the credibility and relevance of the findings.

The Framework Method is appropriate for thematic analysis of textual data, particularly interview transcripts, where it is important to be able to compare and contrast data by themes across many cases, while also situating each perspective in context by retaining the connection to other aspects of each individual’s account. Experienced qualitative researchers should lead and facilitate all aspects of the analysis, although the Framework Method’s systematic approach makes it suitable for involving all members of a multi-disciplinary team. An open, critical and reflexive approach from all team members is essential for rigorous qualitative analysis.

Acceptance of the complexity of real life health systems and the existence of multiple perspectives on health issues is necessary to produce high quality qualitative research. If done well, qualitative studies can shed explanatory and predictive light on important phenomena, relate constructively to quantitative parts of a larger study, and contribute to the improvement of health services and development of health policy. The Framework Method, when selected and implemented appropriately, can be a suitable tool for achieving these aims through producing credible and relevant findings.

The Framework Method is an excellent tool for supporting thematic (qualitative content) analysis because it provides a systematic model for managing and mapping the data.

The Framework Method is most suitable for analysis of interview data, where it is desirable to generate themes by making comparisons within and between cases.

The management of large data sets is facilitated by the Framework Method as its matrix form provides an intuitively structured overview of summarised data.

The clear, step-by-step process of the Framework Method makes it is suitable for interdisciplinary and collaborative projects.

The use of the method should be led and facilitated by an experienced qualitative researcher.

Ritchie J, Lewis J: Qualitative research practice: a guide for social science students and researchers. 2003, London: Sage

Google Scholar

Ives J, Damery S, Redwod S: PPI, paradoxes and Plato: who's sailing the ship?. J Med Ethics. 2013, 39 (3): 181-185. 10.1136/medethics-2011-100150.

Article Google Scholar

Heath G, Cameron E, Cummins C, Greenfield S, Pattison H, Kelly D, Redwood S: Paediatric ‘care closer to home’: stake-holder views and barriers to implementation. Health Place. 2012, 18 (5): 1068-1073. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.05.003.

Elkington H, White P, Addington-Hall J, Higgs R, Petternari C: The last year of life of COPD: a qualitative study of symptoms and services. Respir Med. 2004, 98 (5): 439-445. 10.1016/j.rmed.2003.11.006.

Murtagh J, Dixey R, Rudolf M: A qualitative investigation into the levers and barriers to weight loss in children: opinions of obese children. Archives Dis Child. 2006, 91 (11): 920-923. 10.1136/adc.2005.085712.

Barnard M, Webster S, O’Connor W, Jones A, Donmall M: The drug treatment outcomes research study (DTORS): qualitative study. 2009, London: Home Office

Ayatollahi H, Bath PA, Goodacre S: Factors influencing the use of IT in the emergency department: a qualitative study. Health Inform J. 2010, 16 (3): 189-200. 10.1177/1460458210377480.

Sheard L, Prout H, Dowding D, Noble S, Watt I, Maraveyas A, Johnson M: Barriers to the diagnosis and treatment of venous thromboembolism in advanced cancer patients: a qualitative study. Palliative Med. 2012, 27 (2): 339-348.

Ellis J, Wagland R, Tishelman C, Williams ML, Bailey CD, Haines J, Caress A, Lorigan P, Smith JA, Booton R, et al: Considerations in developing and delivering a nonpharmacological intervention for symptom management in lung cancer: the views of patients and informal caregivers. J Pain Symptom Manag (0). 2012, 44 (6): 831-842. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.12.274.

Gale N, Sultan H: Telehealth as ‘peace of mind’: embodiment, emotions and the home as the primary health space for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder. Health place. 2013, 21: 140-147.

Rashidian A, Eccles MP, Russell I: Falling on stony ground? A qualitative study of implementation of clinical guidelines’ prescribing recommendations in primary care. Health policy. 2008, 85 (2): 148-161. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2007.07.011.

Jones RK: The unsolicited diary as a qualitative research tool for advanced research capacity in the field of health and illness. Qualitative Health Res. 2000, 10 (4): 555-567. 10.1177/104973200129118543.

Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N: Analysing qualitative data. British Med J. 2000, 320: 114-116. 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114.

Pope C, Mays N: Critical reflections on the rise of qualitative research. British Med J. 2009, 339: 737-739.

Fairclough N: Critical discourse analysis: the critical study of language. 2010, London: Longman

Garfinkel H: Ethnomethodology’s program. Soc Psychol Quarter. 1996, 59 (1): 5-21. 10.2307/2787116.

Merleau-Ponty M: The phenomenology of perception. 1962, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul

Svenaeus F: The phenomenology of health and illness. Handbook of phenomenology and medicine. 2001, Netherlands: Springer, 87-108.

Reissmann CK: Narrative methods for the human sciences. 2008, London: Sage

Charmaz K: Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. 2006, London: Sage

Glaser A, Strauss AL: The discovery of grounded theory. 1967, Chicago: Aldine

Crotty M: The foundations of social research: meaning and perspective in the research process. 1998, London: Sage

Boeije H: A purposeful approach to the constant comparative method in the analysis of qualitative interviews. Qual Quant. 2002, 36 (4): 391-409. 10.1023/A:1020909529486.

Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE: Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005, 15 (9): 1277-1288. 10.1177/1049732305276687.

Redwood S, Gale NK, Greenfield S: ‘You give us rangoli, we give you talk’: using an art-based activity to elicit data from a seldom heard group. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012, 12 (1): 7-10.1186/1471-2288-12-7.

Mishler EG: The struggle between the voice of medicine and the voice of the lifeworld. The sociology of health and illness: critical perspectives. Edited by: Conrad P, Kern R. 1990, New York: St Martins Press, Third

Hodges BD, Kuper A, Reeves S: Discourse analysis. British Med J. 2008, 337: 570-572. 10.1136/bmj.39370.701782.DE.

Sandelowski M, Barroso J: Writing the proposal for a qualitative research methodology project. Qual Health Res. 2003, 13 (6): 781-820. 10.1177/1049732303013006003.

Ellins J: It’s better together: involving older people in research. HSMC Newsletter Focus Serv Users Publ. 2010, 16 (1): 4-

Phillimore J, Goodson L, Hennessy D, Ergun E: Empowering Birmingham’s migrant and refugee community organisations: making a difference. 2009, York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation

Leamy M, Clough R: How older people became researchers. 2006, York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation

Glasby J, Miller R, Ellins J, Durose J, Davidson D, McIver S, Littlechild R, Tanner D, Snelling I, Spence K: Final report NIHR service delivery and organisation programme. Understanding and improving transitions of older people: a user and carer centred approach. 2012, London: The Stationery Office

Saldaña J: The coding manual for qualitative researchers. 2009, London: Sage

Lincoln YS: Emerging criteria for quality in qualitative and interpretive research. Qual Inquiry. 1995, 1 (3): 275-289. 10.1177/107780049500100301.

Mays N, Pope C: Qualitative research in health care: assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ British Med J. 2000, 320 (7226): 50-10.1136/bmj.320.7226.50.

Seale C: Quality in qualitative research. Qual Inquiry. 1999, 5 (4): 465-478. 10.1177/107780049900500402.

Dingwall R, Murphy E, Watson P, Greatbatch D, Parker S: Catching goldfish: quality in qualitative research. J Health serv Res Policy. 1998, 3 (3): 167-172.

Popay J, Rogers A, Williams G: Rationale and standards for the systematic review of qualitative literature in health services research. Qual Health Res. 1998, 8 (3): 341-351. 10.1177/104973239800800305.

Morse JM, Barrett M, Mayan M, Olson K, Spiers J: Verification strategies for establishing reliability and validity in qualitative research. Int J Qual Methods. 2008, 1 (2): 13-22.

Smith JA: Reflecting on the development of interpretative phenomenological analysis and its contribution to qualitative research in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2004, 1 (1): 39-54.

Polit DF, Beck CT: Generalization in quantitative and qualitative research: Myths and strategies. Int J Nurs Studies. 2010, 47 (11): 1451-1458. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.06.004.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2288/13/117/prepub

Download references

Acknowledgments

All authors were funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) through the Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care for Birmingham and Black Country (CLAHRC-BBC) programme. The views in this publication expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Health Services Management Centre, University of Birmingham, Park House, 40 Edgbaston Park Road, Birmingham, B15 2RT, UK

Nicola K Gale

School of Health and Population Sciences, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham, B15 2TT, UK

Gemma Heath & Sabi Redwood

School of Life and Health Sciences, Aston University, Aston Triangle, Birmingham, B4 7ET, UK

Elaine Cameron

East and North Hertfordshire NHS Trust, Lister hospital, Coreys Mill Lane, Stevenage, SG1 4AB, UK

Sabina Rashid

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Nicola K Gale .

Additional information

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors were involved in the development of the concept of the article and drafting the article. NG wrote the first draft of the article, GH and EC prepared the text and figures related to the illustrative example, SRa did the literature search to identify if there were any similar articles currently available and contributed to drafting of the article, and SRe contributed to drafting of the article and the illustrative example. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Additional file 1: illustrative example of the use of the framework method.(docx 167 kb), authors’ original submitted files for images.

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Authors’ original file for figure 1

Authors’ original file for figure 2, authors’ original file for figure 3, authors’ original file for figure 4, authors’ original file for figure 5, authors’ original file for figure 6, rights and permissions.

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Gale, N.K., Heath, G., Cameron, E. et al. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 13 , 117 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-117

Download citation

Received : 17 December 2012

Accepted : 06 September 2013

Published : 18 September 2013

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-117

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Qualitative research

- Qualitative content analysis

- Multi-disciplinary research

BMC Medical Research Methodology

ISSN: 1471-2288

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Research Writing and Analysis

- NVivo Group and Study Sessions

- SPSS This link opens in a new window

- Statistical Analysis Group sessions

- Using Qualtrics