- About WordPress

- Get Involved

- WordPress.org

- Documentation

- Learn WordPress

The Center for Teaching Writing

At the university of oregon.

Designing Effective Writing Assignments

Before designing any assignment, it is necessary to first assess the course objectives and what is the best way to meet those objectives. There are several important aspects to consider when creating assignments:

- Teacher’s assignment goals

- The writer’s purpose

- The context of the assignment

- The audience of the assignment

- Format and method

- Teacher’s response and evaluation

- Opportunities for revision

- Communicating expectations

Teacher’s assignment goals: To make a successful assignment, you must first be clear about what the assignment should accomplish. You may want to use some assignments to generate discussion in class or to give students the opportunity to present their ideas in class. Other goals are to give students the opportunity to express questions and confusion; to demonstrate understanding of course concepts and information; to respond to class readings and discussion; to prepare for other assignments or exams; or to clarify ideas for themselves.

There are two main kinds of writing assignments for content courses :

Writing to Learn assignments are usually short, informal assignments. The audience for such assignments can be the student herself, peers, or the teacher. These assignments can be in-class writing, or out of class writing. The primary purpose of writing to learn assignments is for students to grasp the ideas and concepts presented in the course for themselves.

Other writing assignments are used primarily to demonstrate knowledge . The audience for these assignments is most often the teacher. These are formal assignments written for a grade.

These two types of assignments are not mutually exclusive. An assignment can both aid students in the learning process and demonstrate a student’s knowledge and understanding. However, it is important to determine the primary purpose the assignment must serve in order to decide what kind of writing to assign.

Other things to think about in terms of your goals for the assignment: What part does this assignment play in the rest of the course? Is this assignment part of a sequence of assignments that includes both formal and informal writing? Sequenced assignments are helpful in incorporating informal writing to learn assignments with formal demonstrative assignments. For example, thesis writing, reading responses, and short microthemes or abstracts can lead to a formal essay or term paper.

The writer’s purpose: The writer’s purpose dictates what kind of product the students will end up with. There are a number of different purposes for assignments to fulfill; the purpose dictates the form and content of an assignment. For example, students might be asked to articulate questions they have about course content; compose an article explaining course concepts to peers; respond to course reading or discussion; or argue a position on an issue related to the field of study. Whatever the writer’s purpose, it will determine the context, audience, and format of the assignment as well.

The context of the assignment: Will this be an in-class or out-of-class assignment? Some assignments take place in the field of research. Will the students be working alone, or in groups or pairs? To what is the student responding – one or more readings, discussion, research? Will you assign a particular issue or allow students to identify the issues themselves? Part of determining context is deciding the audience the students are to address.

The audience of the assignment: The implied audience may be the same as or different from the real audience. Both the implied and real audiences influence the shape of the assignment. To whom are the students directing their writing? The implied audience can be the teacher, peers, scholars in the field, or the general public who is unfamiliar with the concepts of the discipline. Specifying the implied audience will help students determine what common ground is available in the form of shared assumptions or theoretical perspectives. Also important is the real audience. Who is actually going to read this assignment? The student only? The teacher only? Peers only? A small group of peers? The teacher and peers? Will there be multiple drafts? Will the student get comments from you or from peers before the final product is graded?

Format and method: What should the completed assignment look like? Is there a particular way students should go about fulfilling the assignment? Is there a particular field protocol? Are students expected to use research?

Teacher’s response and evaluation: Some writing to learn assignments are not graded or receive nontraditional grades. How will this assignment help fulfill course objectives, and how much of the course grade should be determined by this assignment? Will students get your comments before the final grade or after? What should students learn from your comments?

Opportunities for revision: Another important aspect to designing an assignment is deciding whether and how to incorporate revision. There are several ways to allow students to revise their work:

- Allowing students to revise after an assignment is graded for the possibility of raising their grade.

- Assigning multiple drafts as part of the final grade. Such an assignment would be graded as a process-based on how the student challenged her own ideas-rather than as a product. The student would receive either teacher comments, peer comments, or both on early drafts that will guide them in revision.

- Using peer evaluations on early drafts. Reading and commenting on fellow students’ work helps students learn to read critically and be responsible members of the discourse community of the classroom and of the field. If you are using peer response, what is the format? Students can respond to the writing of their peers in writing or orally, in groups or one-on-one. Will you provide detailed instructions and specific protocols for responding to student writing or allow them to develop their own format?

Communicating your expectations: Once you have determined the assignment objectives and how best to meet those objectives, you should give your assignment in writing to the students. Have you designed the assignment so that the students understand your goals and their purpose? Are the terms clear? Have you specified the audience, context, format, and means of evaluation? It is often helpful to get feedback on your assignments from colleagues who can tell you whether or not your expectations are totally clear.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Teaching, Learning, & Professional Development Center

- Teaching Resources

- TLPDC Teaching Resources

How Do I Create Meaningful and Effective Assignments?

Prepared by allison boye, ph.d. teaching, learning, and professional development center.

Assessment is a necessary part of the teaching and learning process, helping us measure whether our students have really learned what we want them to learn. While exams and quizzes are certainly favorite and useful methods of assessment, out of class assignments (written or otherwise) can offer similar insights into our students' learning. And just as creating a reliable test takes thoughtfulness and skill, so does creating meaningful and effective assignments. Undoubtedly, many instructors have been on the receiving end of disappointing student work, left wondering what went wrong… and often, those problems can be remedied in the future by some simple fine-tuning of the original assignment. This paper will take a look at some important elements to consider when developing assignments, and offer some easy approaches to creating a valuable assessment experience for all involved.

First Things First…

Before assigning any major tasks to students, it is imperative that you first define a few things for yourself as the instructor:

- Your goals for the assignment . Why are you assigning this project, and what do you hope your students will gain from completing it? What knowledge, skills, and abilities do you aim to measure with this assignment? Creating assignments is a major part of overall course design, and every project you assign should clearly align with your goals for the course in general. For instance, if you want your students to demonstrate critical thinking, perhaps asking them to simply summarize an article is not the best match for that goal; a more appropriate option might be to ask for an analysis of a controversial issue in the discipline. Ultimately, the connection between the assignment and its purpose should be clear to both you and your students to ensure that it is fulfilling the desired goals and doesn't seem like “busy work.” For some ideas about what kinds of assignments match certain learning goals, take a look at this page from DePaul University's Teaching Commons.

- Have they experienced “socialization” in the culture of your discipline (Flaxman, 2005)? Are they familiar with any conventions you might want them to know? In other words, do they know the “language” of your discipline, generally accepted style guidelines, or research protocols?

- Do they know how to conduct research? Do they know the proper style format, documentation style, acceptable resources, etc.? Do they know how to use the library (Fitzpatrick, 1989) or evaluate resources?

- What kinds of writing or work have they previously engaged in? For instance, have they completed long, formal writing assignments or research projects before? Have they ever engaged in analysis, reflection, or argumentation? Have they completed group assignments before? Do they know how to write a literature review or scientific report?

In his book Engaging Ideas (1996), John Bean provides a great list of questions to help instructors focus on their main teaching goals when creating an assignment (p.78):

1. What are the main units/modules in my course?

2. What are my main learning objectives for each module and for the course?

3. What thinking skills am I trying to develop within each unit and throughout the course?

4. What are the most difficult aspects of my course for students?

5. If I could change my students' study habits, what would I most like to change?

6. What difference do I want my course to make in my students' lives?

What your students need to know

Once you have determined your own goals for the assignment and the levels of your students, you can begin creating your assignment. However, when introducing your assignment to your students, there are several things you will need to clearly outline for them in order to ensure the most successful assignments possible.

- First, you will need to articulate the purpose of the assignment . Even though you know why the assignment is important and what it is meant to accomplish, you cannot assume that your students will intuit that purpose. Your students will appreciate an understanding of how the assignment fits into the larger goals of the course and what they will learn from the process (Hass & Osborn, 2007). Being transparent with your students and explaining why you are asking them to complete a given assignment can ultimately help motivate them to complete the assignment more thoughtfully.

- If you are asking your students to complete a writing assignment, you should define for them the “rhetorical or cognitive mode/s” you want them to employ in their writing (Flaxman, 2005). In other words, use precise verbs that communicate whether you are asking them to analyze, argue, describe, inform, etc. (Verbs like “explore” or “comment on” can be too vague and cause confusion.) Provide them with a specific task to complete, such as a problem to solve, a question to answer, or an argument to support. For those who want assignments to lead to top-down, thesis-driven writing, John Bean (1996) suggests presenting a proposition that students must defend or refute, or a problem that demands a thesis answer.

- It is also a good idea to define the audience you want your students to address with their assignment, if possible – especially with writing assignments. Otherwise, students will address only the instructor, often assuming little requires explanation or development (Hedengren, 2004; MIT, 1999). Further, asking students to address the instructor, who typically knows more about the topic than the student, places the student in an unnatural rhetorical position. Instead, you might consider asking your students to prepare their assignments for alternative audiences such as other students who missed last week's classes, a group that opposes their position, or people reading a popular magazine or newspaper. In fact, a study by Bean (1996) indicated the students often appreciate and enjoy assignments that vary elements such as audience or rhetorical context, so don't be afraid to get creative!

- Obviously, you will also need to articulate clearly the logistics or “business aspects” of the assignment . In other words, be explicit with your students about required elements such as the format, length, documentation style, writing style (formal or informal?), and deadlines. One caveat, however: do not allow the logistics of the paper take precedence over the content in your assignment description; if you spend all of your time describing these things, students might suspect that is all you care about in their execution of the assignment.

- Finally, you should clarify your evaluation criteria for the assignment. What elements of content are most important? Will you grade holistically or weight features separately? How much weight will be given to individual elements, etc? Another precaution to take when defining requirements for your students is to take care that your instructions and rubric also do not overshadow the content; prescribing too rigidly each element of an assignment can limit students' freedom to explore and discover. According to Beth Finch Hedengren, “A good assignment provides the purpose and guidelines… without dictating exactly what to say” (2004, p. 27). If you decide to utilize a grading rubric, be sure to provide that to the students along with the assignment description, prior to their completion of the assignment.

A great way to get students engaged with an assignment and build buy-in is to encourage their collaboration on its design and/or on the grading criteria (Hudd, 2003). In his article “Conducting Writing Assignments,” Richard Leahy (2002) offers a few ideas for building in said collaboration:

• Ask the students to develop the grading scale themselves from scratch, starting with choosing the categories.

• Set the grading categories yourself, but ask the students to help write the descriptions.

• Draft the complete grading scale yourself, then give it to your students for review and suggestions.

A Few Do's and Don'ts…

Determining your goals for the assignment and its essential logistics is a good start to creating an effective assignment. However, there are a few more simple factors to consider in your final design. First, here are a few things you should do :

- Do provide detail in your assignment description . Research has shown that students frequently prefer some guiding constraints when completing assignments (Bean, 1996), and that more detail (within reason) can lead to more successful student responses. One idea is to provide students with physical assignment handouts , in addition to or instead of a simple description in a syllabus. This can meet the needs of concrete learners and give them something tangible to refer to. Likewise, it is often beneficial to make explicit for students the process or steps necessary to complete an assignment, given that students – especially younger ones – might need guidance in planning and time management (MIT, 1999).

- Do use open-ended questions. The most effective and challenging assignments focus on questions that lead students to thinking and explaining, rather than simple yes or no answers, whether explicitly part of the assignment description or in the brainstorming heuristics (Gardner, 2005).

- Do direct students to appropriate available resources . Giving students pointers about other venues for assistance can help them get started on the right track independently. These kinds of suggestions might include information about campus resources such as the University Writing Center or discipline-specific librarians, suggesting specific journals or books, or even sections of their textbook, or providing them with lists of research ideas or links to acceptable websites.

- Do consider providing models – both successful and unsuccessful models (Miller, 2007). These models could be provided by past students, or models you have created yourself. You could even ask students to evaluate the models themselves using the determined evaluation criteria, helping them to visualize the final product, think critically about how to complete the assignment, and ideally, recognize success in their own work.

- Do consider including a way for students to make the assignment their own. In their study, Hass and Osborn (2007) confirmed the importance of personal engagement for students when completing an assignment. Indeed, students will be more engaged in an assignment if it is personally meaningful, practical, or purposeful beyond the classroom. You might think of ways to encourage students to tap into their own experiences or curiosities, to solve or explore a real problem, or connect to the larger community. Offering variety in assignment selection can also help students feel more individualized, creative, and in control.

- If your assignment is substantial or long, do consider sequencing it. Far too often, assignments are given as one-shot final products that receive grades at the end of the semester, eternally abandoned by the student. By sequencing a large assignment, or essentially breaking it down into a systematic approach consisting of interconnected smaller elements (such as a project proposal, an annotated bibliography, or a rough draft, or a series of mini-assignments related to the longer assignment), you can encourage thoughtfulness, complexity, and thoroughness in your students, as well as emphasize process over final product.

Next are a few elements to avoid in your assignments:

- Do not ask too many questions in your assignment. In an effort to challenge students, instructors often err in the other direction, asking more questions than students can reasonably address in a single assignment without losing focus. Offering an overly specific “checklist” prompt often leads to externally organized papers, in which inexperienced students “slavishly follow the checklist instead of integrating their ideas into more organically-discovered structure” (Flaxman, 2005).

- Do not expect or suggest that there is an “ideal” response to the assignment. A common error for instructors is to dictate content of an assignment too rigidly, or to imply that there is a single correct response or a specific conclusion to reach, either explicitly or implicitly (Flaxman, 2005). Undoubtedly, students do not appreciate feeling as if they must read an instructor's mind to complete an assignment successfully, or that their own ideas have nowhere to go, and can lose motivation as a result. Similarly, avoid assignments that simply ask for regurgitation (Miller, 2007). Again, the best assignments invite students to engage in critical thinking, not just reproduce lectures or readings.

- Do not provide vague or confusing commands . Do students know what you mean when they are asked to “examine” or “discuss” a topic? Return to what you determined about your students' experiences and levels to help you decide what directions will make the most sense to them and what will require more explanation or guidance, and avoid verbiage that might confound them.

- Do not impose impossible time restraints or require the use of insufficient resources for completion of the assignment. For instance, if you are asking all of your students to use the same resource, ensure that there are enough copies available for all students to access – or at least put one copy on reserve in the library. Likewise, make sure that you are providing your students with ample time to locate resources and effectively complete the assignment (Fitzpatrick, 1989).

The assignments we give to students don't simply have to be research papers or reports. There are many options for effective yet creative ways to assess your students' learning! Here are just a few:

Journals, Posters, Portfolios, Letters, Brochures, Management plans, Editorials, Instruction Manuals, Imitations of a text, Case studies, Debates, News release, Dialogues, Videos, Collages, Plays, Power Point presentations

Ultimately, the success of student responses to an assignment often rests on the instructor's deliberate design of the assignment. By being purposeful and thoughtful from the beginning, you can ensure that your assignments will not only serve as effective assessment methods, but also engage and delight your students. If you would like further help in constructing or revising an assignment, the Teaching, Learning, and Professional Development Center is glad to offer individual consultations. In addition, look into some of the resources provided below.

Online Resources

“Creating Effective Assignments” http://www.unh.edu/teaching-excellence/resources/Assignments.htm This site, from the University of New Hampshire's Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning, provides a brief overview of effective assignment design, with a focus on determining and communicating goals and expectations.

Gardner, T. (2005, June 12). Ten Tips for Designing Writing Assignments. Traci's Lists of Ten. http://www.tengrrl.com/tens/034.shtml This is a brief yet useful list of tips for assignment design, prepared by a writing teacher and curriculum developer for the National Council of Teachers of English . The website will also link you to several other lists of “ten tips” related to literacy pedagogy.

“How to Create Effective Assignments for College Students.” http:// tilt.colostate.edu/retreat/2011/zimmerman.pdf This PDF is a simplified bulleted list, prepared by Dr. Toni Zimmerman from Colorado State University, offering some helpful ideas for coming up with creative assignments.

“Learner-Centered Assessment” http://cte.uwaterloo.ca/teaching_resources/tips/learner_centered_assessment.html From the Centre for Teaching Excellence at the University of Waterloo, this is a short list of suggestions for the process of designing an assessment with your students' interests in mind. “Matching Learning Goals to Assignment Types.” http://teachingcommons.depaul.edu/How_to/design_assignments/assignments_learning_goals.html This is a great page from DePaul University's Teaching Commons, providing a chart that helps instructors match assignments with learning goals.

Additional References Bean, J.C. (1996). Engaging ideas: The professor's guide to integrating writing, critical thinking, and active learning in the classroom . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Fitzpatrick, R. (1989). Research and writing assignments that reduce fear lead to better papers and more confident students. Writing Across the Curriculum , 3.2, pp. 15 – 24.

Flaxman, R. (2005). Creating meaningful writing assignments. The Teaching Exchange . Retrieved Jan. 9, 2008 from http://www.brown.edu/Administration/Sheridan_Center/pubs/teachingExchange/jan2005/01_flaxman.pdf

Hass, M. & Osborn, J. (2007, August 13). An emic view of student writing and the writing process. Across the Disciplines, 4.

Hedengren, B.F. (2004). A TA's guide to teaching writing in all disciplines . Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's.

Hudd, S. S. (2003, April). Syllabus under construction: Involving students in the creation of class assignments. Teaching Sociology , 31, pp. 195 – 202.

Leahy, R. (2002). Conducting writing assignments. College Teaching , 50.2, pp. 50 – 54.

Miller, H. (2007). Designing effective writing assignments. Teaching with writing . University of Minnesota Center for Writing. Retrieved Jan. 9, 2008, from http://writing.umn.edu/tww/assignments/designing.html

MIT Online Writing and Communication Center (1999). Creating Writing Assignments. Retrieved January 9, 2008 from http://web.mit.edu/writing/Faculty/createeffective.html .

Contact TTU

- Blogs @Oregon State University

Ecampus Course Development and Training

Providing inspiration for your online class.

The Power of an Assignment’s Purpose Statement

Have you ever been assigned a task but found yourself asking: “What’s the point of this task? Why do I need to do this?” Very likely, no one has informed you of the purpose of this task! Well, it likely was because that activity was missing to show a critical element: the purpose. Just like the purpose of a task can be easily left out, in the context of course design, a purpose statement for an assignment is often missing too.

Creating a purpose statement for assignments is an activity that I enjoy very much. I encourage instructors and course developers to be intentional about that statement which serves as a declaration of the underlying reasons, directions, and focus of what comes next in an assignment. But most importantly, the statement responds to the question I mentioned at the beginning of this blog… why… ?

Just as a purpose statement should be powerful to guide, shape, and undergird a business (Yohn, 2022), a purpose statement for an assignment can guide students in making decisions about using strategies and resources, shape students’ motivation and engagement in the process of completing the assignment, and undergird their knowledge and skills. Let’s look closer at the power of a purpose statement.

What does “purpose” mean?

Merriam-Webster defines purpose as “ something set up as an object or end to be” , while Cambridge Dictionary defines it as “why you do something or why something exists”. These definitions show us that the purpose is the reason and the intention behind an action.

Why a purpose is important in an assignment?

The purpose statement in an assignment serves important roles for students, instructors, and instructional designers (believe it or not!).

For students

The purpose will:

- answer the question “why will I need to complete this assignment?”

- give the reason to spend time and resources working out math problems, outlining a paper, answering quiz questions, posting their ideas in a discussion, and many other learning activities.

- highlight its significance and value within the context of the course.

- guide them in understanding the requirements and expectations of the assignment from the start.

For instructors

- guide the scope, depth, and significance of the assignment.

- help to craft a clear and concise declaration of the assignment’s objective or central argument.

- maintain the focus on and alignment with the outcome(s) throughout the assignment.

- help identify the prior knowledge and skills students will be required to complete the assignment.

- guide the selection of support resources.

For instructional designers

- guide building the structure of the assignment components.

- help identify additional support resources when needed.

- facilitate an understanding of the alignment of outcome(s).

- help test the assignment from the student’s perspective and experience.

Is there a wrong purpose?

No, not really. But it may be lacking or it may be phrased as a task. Let’s see an example (adapted from a variety of real-life examples) below:

Project Assignment:

“The purpose of this assignment is to work in your group to create a PowerPoint presentation about the team project developed in the course. Include the following in the presentation:

- Purpose of project

- Target audience

- Application of methods

- Recommendations

- Sources (at least 10)

- Images and pictures

The presentation should be a minimum of 6 slides and must include a short reflection on your experience conducting the project as a team.”

What is unclear in this purpose? Well, unless the objective of the assignment is to refine students’ presentation-building skills, it is unclear why students will be creating a presentation for a project that they have already developed. In this example, creating a presentation and providing specific details about its content and format looks more like instructions instead of a clear reason for this assignment to be.

A better description of the purpose could be:

“The purpose of this assignment is to help you convey complex information and concepts in visual and graphic formats. This will help you practice your skills in summarizing and synthesizing your research as well as in effective data visualization.”

The purpose statement particularly underscores transparency, value, and meaning. When students know why, they may be more compelled to engage in the what and how of the assignment. A specific purpose statement can promote appreciation for learning through the assignment (Christopher, 2018).

Examples of purpose statements

Below you will find a few examples of purpose statements from different subject areas.

Example 1: Application and Dialogue (Discussion assignment)

Courtesy of Prof. Courtney Campbell – PHL /REL 344

Example 2: An annotated bibliography (Written assignment)

Courtesy of Prof. Emily Elbom – WR 227Z

Example 3: Reflect and Share (Discussion assignment)

Courtesy of Profs. Nordica MacCarty and Shaozeng Zhang – ANTH / HEST 201

With the increased availability of language learning models (LLMs) and artificial intelligence (AI) tools (e.g., ChatGPT, Claude2), many instructors worry that students would resort to these tools to complete the assignments. While a clear and explicit purpose statement won’t deter the use of these highly sophisticated tools, transparency in the assignment description could be a good motivator to complete the assignments with no or little AI tools assistance.

“ Knowing why you do what you do is crucial ” in life says Christina Tiplea. The same applies to learning, when “why” is clear, the purpose of an activity or assignment can become a more meaningful and crucial activity that motivates and engages students. And students may feel less motiavted to use AI tools (Trust, 2023).

Note : This blog was written entirely by me without the aid of any artificial intelligence tool. It was peer-reviewed by a human colleague.

Christopher, K. (02018). What are we doing and why? Transparent assignment design benefits students and faculty alike . The Flourishing Academic .

Sinek, S. (2011). Start with why . Penguin Publishing Group.

Trust, T. (2023). Addressing the Possibility of AI-Driven Cheating, Part 2 . Faculty Focus.

Yohn, D.L. (2022). Making purpose statements matter . SHR Executive Network.

Leave a reply Cancel reply

Contact info.

Thesis and Purpose Statements

Use the guidelines below to learn the differences between thesis and purpose statements.

In the first stages of writing, thesis or purpose statements are usually rough or ill-formed and are useful primarily as planning tools.

A thesis statement or purpose statement will emerge as you think and write about a topic. The statement can be restricted or clarified and eventually worked into an introduction.

As you revise your paper, try to phrase your thesis or purpose statement in a precise way so that it matches the content and organization of your paper.

Thesis statements

A thesis statement is a sentence that makes an assertion about a topic and predicts how the topic will be developed. It does not simply announce a topic: it says something about the topic.

Good: X has made a significant impact on the teenage population due to its . . . Bad: In this paper, I will discuss X.

A thesis statement makes a promise to the reader about the scope, purpose, and direction of the paper. It summarizes the conclusions that the writer has reached about the topic.

A thesis statement is generally located near the end of the introduction. Sometimes in a long paper, the thesis will be expressed in several sentences or an entire paragraph.

A thesis statement is focused and specific enough to be proven within the boundaries of the paper. Key words (nouns and verbs) should be specific, accurate, and indicative of the range of research, thrust of the argument or analysis, and the organization of supporting information.

Purpose statements

A purpose statement announces the purpose, scope, and direction of the paper. It tells the reader what to expect in a paper and what the specific focus will be.

Common beginnings include:

“This paper examines . . .,” “The aim of this paper is to . . .,” and “The purpose of this essay is to . . .”

A purpose statement makes a promise to the reader about the development of the argument but does not preview the particular conclusions that the writer has drawn.

A purpose statement usually appears toward the end of the introduction. The purpose statement may be expressed in several sentences or even an entire paragraph.

A purpose statement is specific enough to satisfy the requirements of the assignment. Purpose statements are common in research papers in some academic disciplines, while in other disciplines they are considered too blunt or direct. If you are unsure about using a purpose statement, ask your instructor.

This paper will examine the ecological destruction of the Sahel preceding the drought and the causes of this disintegration of the land. The focus will be on the economic, political, and social relationships which brought about the environmental problems in the Sahel.

Sample purpose and thesis statements

The following example combines a purpose statement and a thesis statement (bold).

The goal of this paper is to examine the effects of Chile’s agrarian reform on the lives of rural peasants. The nature of the topic dictates the use of both a chronological and a comparative analysis of peasant lives at various points during the reform period. . . The Chilean reform example provides evidence that land distribution is an essential component of both the improvement of peasant conditions and the development of a democratic society. More extensive and enduring reforms would likely have allowed Chile the opportunity to further expand these horizons.

For more tips about writing thesis statements, take a look at our new handout on Developing a Thesis Statement.

Writing Process and Structure

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Getting Started with Your Paper

Interpreting Writing Assignments from Your Courses

Generating Ideas for Your Paper

Creating an Argument

Thesis vs. Purpose Statements

Developing a Thesis Statement

Architecture of Arguments

Working with Sources

Quoting and Paraphrasing Sources

Using Literary Quotations

Citing Sources in Your Paper

Drafting Your Paper

Introductions

Paragraphing

Developing Strategic Transitions

Conclusions

Revising Your Paper

Peer Reviews

Reverse Outlines

Revising an Argumentative Paper

Revision Strategies for Longer Projects

Finishing Your Paper

Twelve Common Errors: An Editing Checklist

How to Proofread your Paper

Seeking Feedback from Others

Writing Collaboratively

Collaborative and Group Writing

Understanding the Assignment

There are four kinds of analysis you need to do in order to fully understand an assignment: determining the purpose of the assignment , understanding how to answer an assignment’s questions , recognizing implied questions in the assignment , and recognizing the disciplinary expectations of the assignment .

Always make sure you fully understand an assignment before you start writing!

Determining the Purpose

The wording of an assignment should suggest its purpose. Any of the following might be expected of you in a college writing assignment:

- Summarizing information

- Analyzing ideas and concepts

- Taking a position and defending it

- Combining ideas from several sources and creating your own original argument.

Understanding How to Answer the Assignment

College writing assignments will ask you to answer a how or why question – questions that can’t be answered with just facts. For example, the question “ What are the names of the presidents of the US in the last twenty years?” needs only a list of facts to be answered. The question “ Who was the best president of the last twenty years and why?” requires you to take a position and support that position with evidence.

Sometimes, a list of prompts may appear with an assignment. Remember, your instructor will not expect you to answer all of the questions listed. They are simply offering you some ideas so that you can think of your own questions to ask.

Recognizing Implied Questions

A prompt may not include a clear ‘how’ or ‘why’ question, though one is always implied by the language of the prompt. For example:

“Discuss the effects of the No Child Left Behind Act on special education programs” is asking you to write how the act has affected special education programs. “Consider the recent rise of autism diagnoses” is asking you to write why the diagnoses of autism are on the rise.

Recognizing Disciplinary Expectations

Depending on the discipline in which you are writing, different features and formats of your writing may be expected. Always look closely at key terms and vocabulary in the writing assignment, and be sure to note what type of evidence and citations style your instructor expects.

About Writing: A Guide Copyright © 2015 by Robin Jeffrey is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 5: Audience & Purpose of Writing

Purpose, audience, tone, and content, identifying common academic purposes.

The purpose is simply the reason you are writing a particular document. Basically, the purpose of a piece of writing answers the question “why?” For example, why write a play? To entertain a packed theatre. Why write instructions to the babysitter? To inform them of your schedule and rules. Why write a letter to your Member of Parliament? To persuade them to address your community’s needs.

In academic settings, the reasons for writing typically fulfill four main purposes: to summarize , to analyze , to synthesize , and to evaluate . You will encounter these four purposes not only as you read for your classes but also as you read for work or pleasure. Because reading and writing work together, your writing skills will improve as you read.

Eventually, your instructors will ask you to complete assignments specifically designed to meet one of the four purposes. As you will see, the purpose for writing will guide you through each part of the paper, helping you make decisions about content and style. For now, identifying these purposes by reading paragraphs will prepare you to write individual paragraphs and to build longer assignments.

Summary Paragraphs

Summary paragraphs are designed to give the reader a quick overview of a subject or topic of often addresses the 5 W’s (who, what, where, when, why). This type of paragraph is often found towards the end of an essay or chapter. You may also encounter these types of paragraphs as abstracts or executive summaries .

Analysis Paragraphs

An analysis separates complex materials into their different parts and studies how the parts relate to one another. The analysis of simple table salt, for example, would require a deconstruction of its parts—the elements sodium (Na) and chloride (Cl). Then, scientists would study how the two elements interact to create the compound NaCl, or sodium chloride, which is also called simple table salt.

Analysis is not limited to the sciences, of course. An analysis paragraph in academic writing fulfills the same purpose. Instead of deconstructing chemical compounds, academic analysis paragraphs typically deconstruct documents. An analysis takes apart a primary source (an essay, a book, an article, etc.) point by point. It communicates the main points of the document by examining individual points and identifying how they relate to one another. Take a look at a student’s analysis of the journal report.

Notice how the analysis does not simply repeat information from the original report, but considers how the points within the report relate to one another? By doing this, the student uncovers a discrepancy between the points that are backed up by statistics and those that require additional information. Analyzing a document involves a close examination of each of the individual parts and how they work together.

Synthesis Paragraphs

A synthesis combines two or more items to create an entirely new item. Consider the electronic musical instrument aptly named the synthesizer. It looks like a simple keyboard but displays a dashboard of switches, buttons, and levers. With the flip of a few switches, a musician may combine the distinct sounds of a piano, a flute, or a guitar—or any other combination of instruments—to create a new sound. The purpose of the synthesizer is to blend together the notes from individual instruments to form new, unique notes.

The purpose of an academic synthesis is to blend individual documents into a new document. An academic synthesis paragraph considers the main points from one or more pieces of writing and links the main points together to create a new point, one not replicated in either document.

Take a look at a student’s synthesis of several sources about underage drinking.

Notice how the synthesis paragraphs consider each source and use information from each to create a new thesis. A good synthesis does not repeat information; the writer uses a variety of sources to create a new idea.

Evaluation Paragraphs

An evaluation judges the value of something and determines its worth. Evaluations in everyday experiences are often not only dictated by set standards but are also influenced by opinion and prior knowledge. For example, at work, a supervisor may complete an employee evaluation by judging his subordinate’s performance based on the company’s goals. If the company focuses on improving communication, the supervisor will rate the employee’s customer service according to a standard scale. However, the evaluation still depends on the supervisor’s opinion and prior experience with the employee. The purpose of the evaluation is to determine how well the employee performs on the job.

An academic evaluation communicates your opinion, and its justifications, about a document or a topic of discussion. Evaluations are influenced by your reading of the document, your prior knowledge, and your prior experience with the topic or issue. Because an evaluation incorporates your point of view and the reasons for your point of view, it typically requires more critical thinking and a combination of summary, analysis, and synthesis skills. Thus evaluation paragraphs often follow summary, analysis, and synthesis paragraphs. Read a student’s evaluation paragraph.

Notice how the paragraph incorporates the student’s personal judgment within the evaluation. Evaluating a document requires prior knowledge that is often based on additional research.

Self-Practice Exercise

Read the following paragraphs about four films and then identify the purpose of each paragraph.

This film could easily have been cut down to less than two hours. By the final scene, I noticed that most of my fellow moviegoers were snoozing in their seats and were barely paying attention to what was happening on screen. Although the director sticks diligently to the book, he tries too hard to cram in all the action, which is just too ambitious for such a detail-oriented story. If you want my advice, read the book and give the movie a miss.

During the opening scene, we learn that the character Laura is adopted and that she has spent the past three years desperately trying to track down her real parents. Having exhausted all the usual options—adoption agencies, online searches, family trees, and so on—she is on the verge of giving up when she meets a stranger on a bus. The chance encounter leads to a complicated chain of events that ultimately result in Laura getting her lifelong wish. But is it really what she wants? Throughout the rest of the film, Laura discovers that sometimes the past is best left where it belongs.

To create the feeling of being gripped in a vise, the director, May Lee, uses a variety of elements to gradually increase the tension. The creepy, haunting melody that subtly enhances the earlier scenes becomes ever more insistent, rising to a disturbing crescendo toward the end of the movie. The desperation of the actors, combined with the claustrophobic atmosphere and tight camera angles create a realistic firestorm, from which there is little hope of escape. Walking out of the theatre at the end feels like staggering out of a Roman dungeon.

The scene in which Campbell and his fellow prisoners assist the guards in shutting down the riot immediately strikes the viewer as unrealistic. Based on the recent reports on prison riots in both Detroit and California, it seems highly unlikely that a posse of hardened criminals would intentionally help their captors at the risk of inciting future revenge from other inmates. Instead, both news reports and psychological studies indicate that prisoners who do not actively participate in a riot will go back to their cells and avoid conflict altogether. Examples of this lack of attention to detail occur throughout the film, making it almost unbearable to watch.

Collaboration: Share with a classmate and compare your answers.

Writing at Work

Thinking about the purpose of writing a report in the workplace can help focus and structure the document. A summary should provide colleagues with a factual overview of your findings without going into too much detail. In contrast, an evaluation should include your personal opinion, along with supporting evidence, research, or examples to back it up. Listen for words such as summarize , analyze , synthesize , or evaluate when your boss asks you to complete a report to help determine a purpose for writing.

Consider the expository essay you will soon have to write. Identify the most effective academic purpose for the assignment.

My assignment: ____________________________________________

My purpose: ________________________________________________

Identifying the Audience

Imagine you must give a presentation to a group of executives in an office. Weeks before the big day, you spend time creating and rehearsing the presentation. You must make important, careful decisions not only about the content but also about your delivery. Will the presentation require technology to project figures and charts? Should the presentation define important words, or will the executives already know the terms? Should you wear your suit and dress shirt? The answers to these questions will help you develop an appropriate relationship with your audience, making them more receptive to your message.

Now imagine you must explain the same business concepts from your presentation to a group of high school students. Those important questions you previously answered may now require different answers. The figures and charts may be too sophisticated, and the terms will certainly require definitions. You may even reconsider your outfit and sport a more casual look. Because the audience has shifted, your presentation and delivery will shift as well to create a new relationship with the new audience.

In these two situations, the audience —the individuals who will watch and listen to the presentation—plays a role in the development of presentation. As you prepare the presentation, you visualize the audience to anticipate their expectations and reactions. What you imagine affects the information you choose to present and how you will present it. Then, during the presentation, you meet the audience in person and discover immediately how well you perform.

Although the audience for writing assignments—your readers—may not appear in person, they play an equally vital role. Even in everyday writing activities, you identify your readers’ characteristics, interests, and expectations before making decisions about what you write. In fact, thinking about audience has become so common that you may not even detect the audience driven decisions.

For example, you update your status on a social networking site with the awareness of who will digitally follow the post. If you want to brag about a good grade, you may write the post to please family members. If you want to describe a funny moment, you may write with your friends’ sense of humour in mind. Even at work, you send emails with an awareness of an unintended receiver who could intercept the message.

In other words, being aware of “invisible” readers is a skill you most likely already possess and one you rely on every day. Consider the following paragraphs. Which one would the author send to her parents? Which one would she send to her best friend?

Last Saturday, I volunteered at a local hospital. The visit was fun and rewarding. I even learned how to do cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or CPR. Unfortunately, I think caught a cold from one of the patients. This week, I will rest in bed and drink plenty of clear fluids. I hope I am well by next Saturday to volunteer again.

Most likely, you matched each paragraph to its intended audience with little hesitation. Because each paragraph reveals the author’s relationship with her intended readers, you can identify the audience fairly quickly. When writing your own paragraphs, you must engage with your audience to build an appropriate relationship given your subject. Imagining your readers during each stage of the writing process will help you make decisions about your writing. Ultimately, the people you visualize will affect what and how you write.

PRO TIP: While giving a speech, you may articulate an inspiring or critical message, but if you left your hair a mess and laced up mismatched shoes, your audience would not take you seriously. They may be too distracted by your appearance to listen to your words.

Similarly, grammar and sentence structure serve as the appearance of a piece of writing. Polishing your work using correct grammar will impress your readers and allow them to focus on what you have to say.

Because focusing on audience will enhance your writing, your process, and your finished product, you must consider the specific traits of your audience members. Use your imagination to anticipate the readers’ demographics, education, prior knowledge, and expectations.

- Demographics: These measure important data about a group of people, such as their age range, ethnicity, religious beliefs, or gender. Certain topics and assignments will require you to consider these factors as they relate to your audience. For other topics and assignments, these measurements may not influence your writing. Regardless, it is important to consider demographics when you begin to think about your purpose for writing.

- Education: Education considers the audience’s level of schooling. If audience members have earned a doctorate degree, for example, you may need to elevate your style and use more formal language. Or, if audience members are still in college, you could write in a more relaxed style. An audience member’s major or emphasis may also dictate your writing.

- Prior knowledge: Prior knowledge is what the audience already knows about your topic. If your readers have studied certain topics, they may already know some terms and concepts related to the topic. You may decide whether to define terms and explain concepts based on your audience’s prior knowledge. Although you cannot peer inside the brains of your readers to discover their knowledge, you can make reasonable assumptions. For instance, a nursing major would presumably know more about health-related topics than a business major would.

- Expectations: These indicate what readers will look for while reading your assignment. Readers may expect consistencies in the assignment’s appearance, such as correct grammar and traditional formatting like double-spaced lines and a legible font. Readers may also have content-based expectations given the assignment’s purpose and organization. In an essay titled “The Economics of Enlightenment: The Effects of Rising Tuition,” for example, audience members may expect to read about the economic repercussions of post-secondary tuition costs.

On a sheet of paper, generate a list of characteristics under each category for each audience. This list will help you later when you read about tone and content.

Your classmates: Demographics ____________________________________________ Education ____________________________________________ Prior knowledge ____________________________________________ Expectations ____________________________________________ Demographics ____________________________________________ Education ____________________________________________ Prior knowledge ____________________________________________ Expectations ____________________________________________ The head of your academic department Demographics ____________________________________________ Education ____________________________________________ Prior knowledge ____________________________________________ Expectations ____________________________________________

Now think about your next writing assignment. Identify the purpose (you may use the same purpose listed in Self–Practice Exercise 1.6b and then identify the audience. Create a list of characteristics under each category.

My assignment:____________________________________________ My purpose: ____________________________________________ My audience: ____________________________________________

Demographics ____________________________________________ Education ____________________________________________ Prior knowledge ____________________________________________ Expectations ____________________________________________

Collaboration: please share with a classmate and compare your answers.

Keep in mind that as your topic shifts in the writing process, your audience may also shift. Also, remember that decisions about style depend on audience, purpose, and content. Identifying your audience’s demographics, education, prior knowledge, and expectations will affect how you write, but purpose and content play an equally important role. The next subsection covers how to select an appropriate tone to match the audience and purpose.

Selecting an Appropriate Tone

Tone identifies a speaker’s attitude toward a subject or another person. You may pick up a person’s tone of voice fairly easily in conversation. A friend who tells you about her weekend may speak excitedly about a fun skiing trip. An instructor who means business may speak in a low, slow voice to emphasize her serious mood. Or, a co-worker who needs to let off some steam after a long meeting may crack a sarcastic joke. Tone is important because the way you might speak to your friends (“oh shut up, it’s fine…”) would definitely not be appropriate when speaking to your boss or your professor.

Just as speakers transmit emotion through voice, writers can transmit through writing a range of attitudes, from excited and humorous to somber and critical. These emotions create connections among the audience, the author, and the subject, ultimately building a relationship between the audience and the text. To stimulate these connections, writers intimate their attitudes and feelings with useful devices, such as sentence structure, word choice, punctuation, and formal or informal language. Keep in mind that the writer’s attitude should always appropriately match the audience and the purpose, which means that you need to choose appropriate language and sentence structure that will convey your ideas with your intent.

Read the following paragraph and consider the writer’s tone. How would you describe the writer’s attitude toward wildlife conservation?

Think about the assignment and purpose you selected in Self–Practice Exercise 1.6b and the audience you selected in Self–Practice Exercise 1.6c. Now, identify the tone you would use in the assignment.

My assignment: ____________________________________________ My purpose: ____________________________________________ My audience: ____________________________________________ My tone: ____________________________________________

Choosing Appropriate, Interesting Content

Content refers to all the written substance in a document. After selecting an audience and a purpose, you must choose what information will make it to the page. Content may consist of examples, statistics, facts, anecdotes, testimonies, and observations, but no matter the type, the information must be appropriate and interesting for the audience and purpose. An essay written for grade 3 students that summarizes the legislative process, for example, would have to contain succinct and simple content.

Content is also shaped by tone. When the tone matches the content, the audience will be more engaged, and you will build a stronger relationship with your readers. Consider that audience of grade 3 students. You would choose simple content that the audience will easily understand, and you would express that content through an enthusiastic tone. The same considerations apply to all audiences and purposes.

Using the assignment, purpose, audience, and tone fromSelf–Practice Exercise 1.6d, generate a list of content ideas. Remember that content consists of examples, statistics, facts, anecdotes, testimonies, and observations.

My assignment: ____________________________________________ My purpose: ____________________________________________ My audience: ____________________________________________ My tone: ____________________________________________ My content ideas: ____________________________________________

Common Writing Assignments

Writing assignments at the post-secondary level serve a different purpose than the typical writing assignments you completed in high school. In high school, teachers generally focus on teaching you to write in a variety of modes and formats, including personal writing, expository writing, research papers, creative writing, and writing short answers and essays for exams. Over time, these assignments help you build a foundation of writing skills.

Now, however, your instructors will expect you to already have that foundation. Your composition courses will focus on helping you make the transition to higher-level writing assignments. However, in most of your other courses, writing assignments serve a different purpose. In those courses, you may use writing as one tool among many for learning how to think about a particular academic discipline.

Additionally, certain assignments teach you how to meet the expectations for professional writing in a given field. Depending on the class, you might be asked to write a lab report, a case study, a literary analysis, a business plan, or an account of a personal interview. You will need to learn and follow the standard conventions for those types of written products.

Finally, personal and creative writing assignments are less common at the post-secondary level than in high school. College and university courses emphasize expository writing—writing that explains or informs. Often expository writing assignments will incorporate outside research, too. Some classes will also require persuasive writing assignments in which you state and support your position on an issue. Your instructors will hold you to a higher standard when it comes to supporting your ideas with reasons and evidence.

Common Types of Writing Assignments

Part of managing your education is communicating well with others at your institution. For instance, you might need to email your instructor to request an office appointment or explain why you will need to miss a class. You might need to contact administrators with questions about your tuition or financial aid. Later, you might ask instructors to write recommendations on your behalf.

Treat these documents as professional communications. Address the recipient politely; state your question, problem, or request clearly; and use a formal, respectful tone. Doing so helps you make a positive impression and get a quicker response.

Using the Writing Process

To complete a writing project successfully, good writers use some variation of the following process.

The Writing Process

- Prewriting. The writer generates ideas to write about and begins developing these ideas.

- Outlining a structure of ideas. The writer determines the overall organizational structure of the writing and creates an outline to organize ideas. Usually this step involves some additional fleshing out of the ideas generated in the first step.

- Writing a rough draft. The writer uses the work completed in prewriting to develop a first draft. The draft covers the ideas the writer brainstormed and follows the organizational plan that was laid out in the first step.

- Revising. The writer revisits the draft to review and, if necessary, reshape its content. This stage involves moderate and sometimes major changes: adding or deleting a paragraph, phrasing the main point differently, expanding on an important idea, reorganizing content, and so forth.

- Editing. The writer reviews the draft to make additional changes. Editing involves making changes to improve style and adherence to standard writing conventions—for instance, replacing a vague word with a more precise one or fixing errors in grammar and spelling. Once this stage is complete, the work is a finished piece and ready to share with others.

Chances are you have already used this process as a writer. You may also have used it for other types of creative projects, such as developing a sketch into a finished painting or composing a song. The steps listed above apply broadly to any project that involves creative thinking. You come up with ideas (often vague at first), you work to give them some structure, you make a first attempt, you figure out what needs improving, and then you refine it until you are satisfied.

Most people have used this creative process in one way or another, but many people have misconceptions about how to use it to write. Here are a few of the most common misconceptions students have about the writing process:

- “I do not have to waste time on prewriting if I understand the assignment.” Even if the task is straightforward and you feel ready to start writing, take some time to develop ideas before you plunge into your draft. Freewriting —writing about the topic without stopping for a set period of time—is one prewriting technique you might try in that situation.

- “It is important to complete a formal, numbered outline for every writing assignment.” For some assignments, such as lengthy research papers, proceeding without a formal outline can be very difficult. However, for other assignments, a structured set of notes or a detailed graphic organizer may suffice. The important thing is to have a solid plan for organizing ideas and details.

- “My draft will be better if I write it when I am feeling inspired.” By all means, take advantage of those moments of inspiration. However, understand that sometimes you will have to write when you are not in the mood. Sit down and start your draft even if you do not feel like it. If necessary, force yourself to write for just one hour. By the end of the hour, you may be far more engaged and motivated to continue. If not, at least you will have accomplished part of the task.

- “My instructor will tell me everything I need to revise.” If your instructor chooses to review drafts, the feedback can help you improve. However, it is still your job, not your instructor’s, to transform the draft to a final, polished piece. That task will be much easier if you give your best effort to the draft before submitting it. During revision, do not just go through and implement your instructor’s corrections. Take time to determine what you can change to make the work the best it can be.

- “I am a good writer, so I do not need to revise or edit.” Even talented writers still need to revise and edit their work. At the very least, doing so will help you catch an embarrassing typo or two. Revising and editing are the steps that make good writers into great writers.

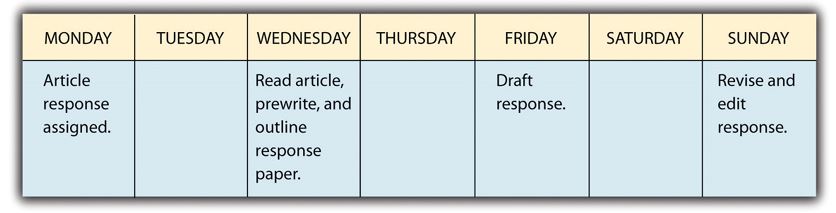

Managing Your Time

When your instructor gives you a writing assignment, write the due date on your calendar. Then work backward from the due date to set aside blocks of time when you will work on the assignment. Always plan at least two sessions of writing time per assignment, so that you are not trying to move from step 1 to step 5 in one evening. Trying to work that fast is stressful, and it does not yield great results. You will plan better, think better, and write better if you space out the steps.

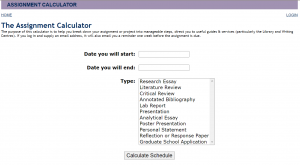

Ideally, you should set aside at least three separate blocks of time to work on a writing assignment: one for prewriting and outlining, one for drafting, and one for revising and editing. Sometimes those steps may be compressed into just a few days. If you have a couple of weeks to work on a paper, space out the five steps over multiple sessions. Long-term projects, such as research papers, require more time for each step:

Again, an assignment calculator is an incredibly useful tool for helping with this process:

Writing for Academic and Professional Contexts: An Introduction Copyright © 2023 by Sheridan College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

COMMENTS

Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like Analyze the purpose of a reading assignment, get a brief overview of the assignment's organization and content, Read the material before highlighting it Highlight key portions of any topic sentence make sure your highlighting reflects the ideas stated in the passage and more.

The primary purpose of previewing an assignment is to? Get a brief overview of the assignment's organization and content. Making predictions about a reading assignment helps you anticipate. What topics will be covered, how the topics will be presented, and how difficult the material is.

Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like A primary purpose of the ICH is to: a. Require FDA registration of worldwide clinical trials. b. Minimize the need for redundant research. c. Require publication of negative trial results. d. Develop mandatory worldwide regulations for drug development., The ICH GCP guidelines: a. Require certification of clinical research sites ...

Before designing any assignment, it is necessary to first assess the course objectives and what is the best way to meet those objectives. There are several important aspects to consider when creating assignments: Teacher's assignment goals; The writer's purpose; The context of the assignment; The audience of the assignment; Format and method

First, you will need to articulate the purpose of the assignment. Even though you know why the assignment is important and what it is meant to accomplish, you cannot assume that your students will intuit that purpose. Your students will appreciate an understanding of how the assignment fits into the larger goals of the course and what they will ...

The purpose statement particularly underscores transparency, value, and meaning. When students know why, they may be more compelled to engage in the what and how of the assignment. A specific purpose statement can promote appreciation for learning through the assignment (Christopher, 2018). Examples of purpose statements

The purpose statement may be expressed in several sentences or even an entire paragraph. A purpose statement is specific enough to satisfy the requirements of the assignment. Purpose statements are common in research papers in some academic disciplines, while in other disciplines they are considered too blunt or direct.

The wording of an assignment should suggest its purpose. Any of the following might be expected of you in a college writing assignment: Summarizing information; Analyzing ideas and concepts; Taking a position and defending it; Combining ideas from several sources and creating your own original argument. Understanding How to Answer the Assignment

Once you have figured out your purpose, use it to guide your writing. For example, after writing each paragraph, ask yourself: Does this paragraph support my assignment's purpose? 2. Identify Key Terms. Underline or highlight all the key terms in the assignment directions. Key terms are words that you must know and talk about in order to ...

An analysis takes apart a primary source (an essay, a book, an article, etc.) point by point. It communicates the main points of the document by examining individual points and identifying how they relate to one another. ... Using the assignment, purpose, audience, and tone fromSelf-Practice Exercise 1.6d, generate a list of content ideas ...