Free 11 Plus English papers

Merchant of Venice revenge essay

Gsce english model essay.

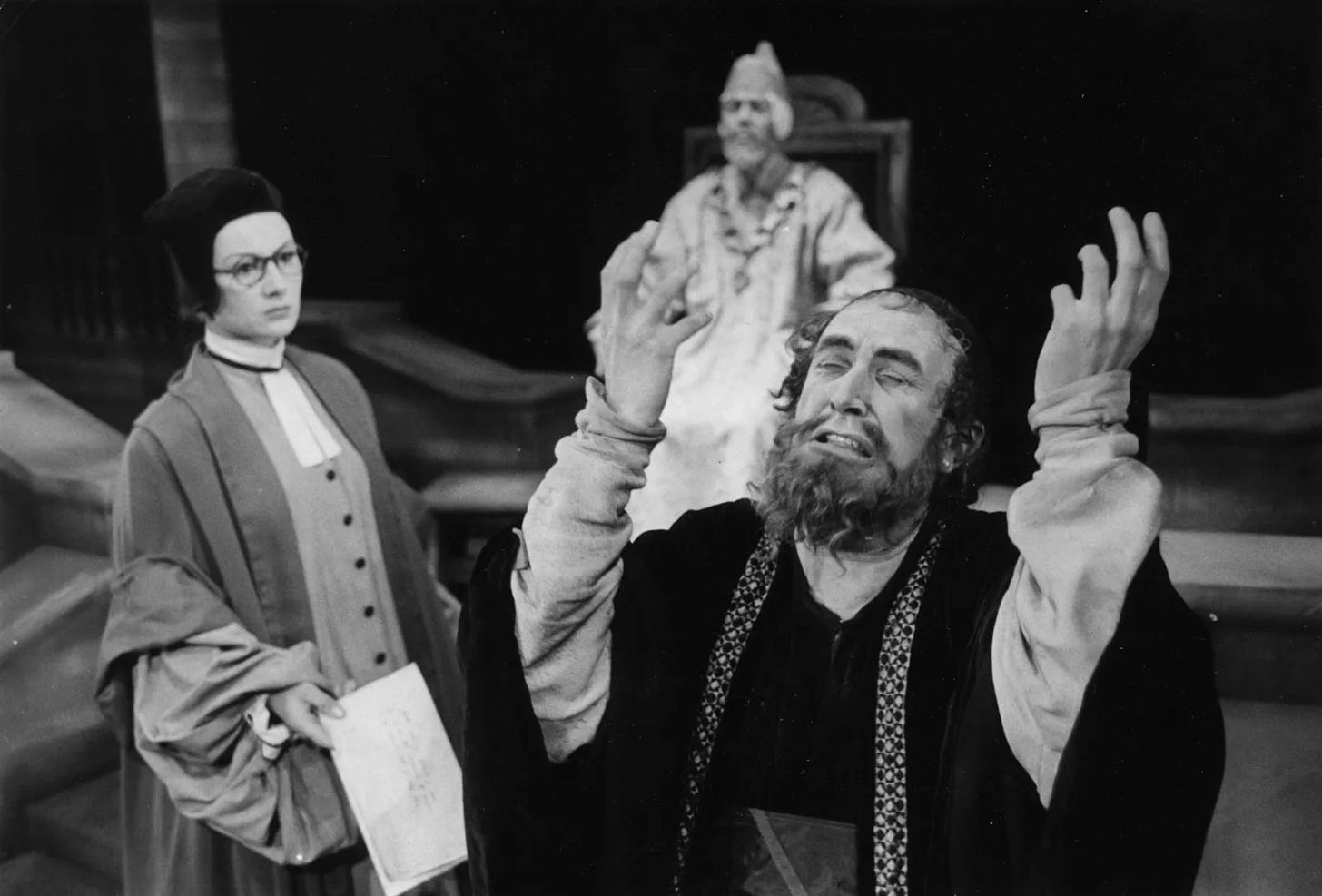

This is a grade 9+ model essay exploring the theme of revenge in The Merchant of Venice.

It’s quite long so isn’t indicative of a timed essay, but it’s full of top grade ideas and insightful contextual information which you can utilise if you’re studying the play.

Task and extract

Read the following extract from act 3, scene 1 of The Merchant of Venice and answer the question which follows.

In this part of the play, Shylock expresses his determination to take his bond and cut a pound of flesh from Antonio.

Why, I am sure if he forfeit, thou wilt not

take his flesh! What’s that good for?

To bait fish withal; if it will feed nothing else, it will feed my

revenge. He hath disgraced me, and hindered me half a million,

laughed at my losses, mocked at my gains, scorned my nation,

thwarted my bargains, cooled my friends, heated mine enemies –

and what's his reason? I am a Jew. Hath not a Jew eyes? Hath not

a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions? Fed

with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the

same diseases, healed by the same means, warmed and cooled by

the same winter and summer as a Christian is? If you prick us, do

we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh? If you poison us,

do we not die? And if you wrong us, shall we not revenge? If we

are like you in the rest, we will resemble you in that. If a Jew wrong

a Christian, what is his humility? Revenge. If a Christian wrong a

Jew, what should his sufferance be by Christian example? Why,

revenge! The villainy you teach me, I will execute, and it shall go

hard but I will better the instruction.

Starting with this moment in the play, explore how Shakespeare presents ideas about revenge in The Merchant of Venice.

Write about:

how Shakespeare presents ideas about revenge in this extract

how Shakespeare presents ideas about revenge in the whole play

The enduring popularity of The Merchant of Venice lies not in its comic but its tragic aspects. What is most compelling is Shylock’s desire for revenge. It is one of the more enigmatic plays because on the surface Shylock fulfils the role of villain but he can be interpreted as a tragic hero. Shylock, while not the protagonist of The Merchant of Venice, is more wronged than any other character, and so we sympathise with him. However, Shakespeare also seems to suggest that Shylock’s insatiable desire for revenge is his hamartia. His desire for revenge is characterized as cruel and senseless, and is what leads to his downfall. But ultimately, because of the extreme antisemitism Shylock faces and the moral hypocrisy of Christian Venice, we feel Shylock is served a great injustice by the State and that his punishment is disproportionate. This is because while his request for a ‘pound of flesh’ is cruel, he and Antonio both of their own free will agree to the contract written.

Before Antonio asks Shylock for a loan, Shylock reveals the deep seated hatred and desire for revenge he has against Antonio in an aside. He remarks upon an ‘ancient grudge’, a phrase echoed in the prologue of Romeo and Juliet , likely written just before or after The Merchant of Venice . Shylock’s language then speaks not simply to a deep rooted hatred between him and Antonio, but a deep rooted hatred between the Jews and Christians. While on the surface, he expresses a special hatred for Antonio, there is a pervasive prejudice against Christians and vice versa. Shylock says, ‘I hate him for he is a Christian’, because he ‘lends out money gratis’ and costs him money; and because Antonio in turn, being a Christian, ‘hates [his] sacred nation’. This hatred borne of anti-Christian prejudice, Shakespeare hints will fuel Shylock’s desire for revenge. His unyielding desire for revenge is foreshadowed in his closing remark, ‘Cursed be my tribe/ If I forgive him!’ In this remark Shylock frames the animosity between him and Antonio as a tribal one between Christian and Jew.

Shylock then reminds Antonio that he has condemned the way that he earns his living, ‘In the Rialto you have rated me/ About my monies and usances.’ Antonio’s moral condemnation stems from Christian doctrine which prohibited Christians from lending money and charging interest, and the way Antonio abuses Shylock reflects the ways Jews would have been persecuted in Venice and Europe during this time. So we sympathise with Shylock when he reminds Antonio of the abuse he has inflicted, ‘You call me misbeliever, cut-throat dog,/ And spit upon my Jewish gaberdine’ he says. Antonio characterises Shylock as a heretic, merciless and less than human. The fact that Antonio spits on Shylock’s Jewish robe hints that he feels utterly contemptuous and disgusted by him, and this points to the anti-semitism and degradation Jews faced generally. Shylock’s long monologue in act 1, scene 3, in which he seems intent on rejecting Antonio’s request for a loan, then serves to highlight the severity of the abuse Jews suffer from Christians, but it also more poignantly highlights the hypocrisy of Christian Venice. Jews are permitted to lend money and Christians to borrow from them when their need is urgent, but they are then lambasted for their business. They are economic scapegoats.

This sense of injustice and hypocrisy inflames Shylock’s hatred and his thirst for vengeance. But it seems Antonio’s churlish retorts and his refusal to concede any moral wrongdoing are what really inspire Shylock to ask for ‘an equal pound of [his] flesh’ as a forfeit. When Shylock has finished reminding Antonio of how he has mistreated him, he more or less asks why he should lend him any money: ‘for these courtesies’ he quips sarcastically, ‘I'll lend you thus much monies’, the monies being the 3000 ducats Antonio requests. Antonio replies bitingly, ‘I am as like to call thee so again,/ To spit on thee again,/ to spurn thee too.’ Rather than grovel apologetically as Shylock may have hoped, Antonio reaffirms his contempt for Shylock. To this reaction, Shylock is shocked and incredulous, ‘Why look you how you storm!’ he exclaims. Antonio, refusing to offer any apology, which would be fitting, sends Shylock into a fit of indignant passion which perhaps inspires the forfeit. While Shylock’s contract then is shocking and perverse, we can sympathise with his motivations.

Yet still when there is doubt that Antonio may actually be able to repay his loan on time, Shylock’s resolve to take his pound of flesh is questioned. When Shylock makes it clear that he will have his bond, the other characters are dumbfounded, characterising Shylock as cruel and unreasonable. For example, Salarino exclaims, ‘I am sure if he forfeit, thou wilt not/ take his flesh!’ (3.1) And when he asks Shylock what Antonio’s flesh would be good for’, Shylock darkly jokes, ‘To bait fish withall’ and goes on to persuade Salarino that he is deadly serious about claiming Antonio’s forfeit of a ‘pound of flesh’ should Antonio fail to repay his loan on time. Shylock then quips, ‘if it will feed nothing else, it will feed my revenge’ and this metaphor suggests that Shylock believes revenge will satisfy the wrong he has suffered from Antonio, who has, as he says to Salarino, ‘mocked at [his] gains, scorned [his] nation, thwarted [his] bargains’. Once again, Shylock reminds us of the abuse he has suffered at the hands of Antonio, underscoring the idea that the forfeit is a form of revenge. It is intentionally cruel and barbaric. So while Shylock’s desire to hurt, even to kill Antonio is monstrous, it is borne out of a desire for revenge which is understandable. Additionally, the language from the semantic field of feeding in Shylock’s monologue and throughout suggests that revenge is a natural basic desire akin to hunger.

However, Shakespeares also suggests that our desire for revenge should be tempered with mercy. Shylock’s ‘To bait fish withal’ speech (3.1) is counterbalanced with Portia’s ‘quality of mercy’ speech and ultimately Shakespeare hints that the right moral course of action is for Shylock to deny himself his thirst for revenge and to be merciful. Portia, dressed as the lawyer, Balthazar, gives a stirring speech in which she attempts to persuade Shylock to show mercy. In this speech, she presents mercy as the noblest virtue. Portia declares, ‘Tis mightiest in the mightiest’ and ‘It is an attribute to God himself’. Mercy is presented as a quality above all others and associates it with divinity. Her rhetoric attempts to persuade Shylock that showing mercy would present him in a both a virtuous and noble light appealing to ethos. Through associating mercy with nobility and divinity, Portia subtly implies that if Shylock shows mercy, he will be seen as just and noble. The monologue draws extensively from the semantic field of monarchy: mercy ‘becomes the throned monarch better than his crown.’ This is because monarchs were seen as closer to God than any other person on earth. They inhabited the highest pinnacle in the great chain of being. There is no other higher point of comparison but God which is why Portia closes her extended metaphor associating it with the divine, ‘And earthly power doth then show likest God’s/ When mercy seasons justice.’ In simpler terms, to show mercy would be to act in a way which is divine.

However, Portia’s words, though stirring in the moment, ring hollow, because of the lack of mercy shown to Shylock later. Though Portia warns those present at court ‘That in the course of justice, none of us/ Should see salvation’, the justice meted out to Shylock is disproportionately punitive. Not only is there the distinct sense that Shylock has been cheated of the justice that he deserved, there is a sense of overcorrection. Whether or not Shylock’s contract was morally justifiable, it is but a loophole, which Shylock fails to foresee in drawing up the contract, that denies him of his bond, and then inadvertently costs him all he owns. When Shylock requests nothing more than the principle once he realises he has been outwitted, he is taunted by Portia. Her behaviour is dishonest and vengeful. Further, her disguise adds an extra layer of duplicity. In fact, Portia and the Duke are both terribly hypocritical. They work in tandem to determine Shylock has conspired unlawfully to take Antonio’s life.

Further, while they gleefully mete out Shylock’s punishment, they ironically claim to be merciful. For example, in response to Gratiano’s barb that Shylock need be hanged ‘at the state’s charge’ because he has been stripped of all his wealth, the Duke, in a mock show of mercy declares, ‘That thou shalt see the difference of our spirit,/ I pardon thee thy life before thou ask it.’ Yet through utterly humiliating Shylock, confiscating all of his wealth and stripping him of his very identity by forcing him to convert to Christianity, he reduces him to nothing. Shylock reasonably retorts that he is as good as dead, ‘Nay take my life and all… you take my life/ When you do take the means whereby I live.’ Lastly, to add insult to injury, Shylock is forced to feign that he is then content with the mercy he has received making his humiliation complete.

Though the play continues and ends on a merry and comical note, our indignation at Shylock’s treatment and our sense of injustice lingers. We sense that he was setting himself up for his own downfall by refusing to compromise, but we sympathize with his desire for revenge. It is made clear that the hatred between Shylock and Antonio is borne of an ‘ancient grudge’. Antonio hates Shylock because he is a Jew and vice versa. However, Shylock, being part of a minority group in Venice, is a victim of antisemitism, whereas Antonio faces no prejudice from Shylock. So ironically, while Shylock is the villain of the play, he is also the greatest victim: Shylock receives much abuse throughout the play and is punished beyond that which feels proportionate. We are left with the sense that Christian Venice has conspired against Shylock to protect Antonio, one of its own tribe (Christian), and the stripping of Shylock’s identity and the forced conversion serve as punishment to warn others. Lastly, while presenting Shylock as cruelly vengeful, it is ultimately Christian Venice which is extreme in its revenge.

Discussion about this post

Ready for more?

The Role of Justice and Revenge in The Merchant of Venice

- Category: Literature

- Topic: The Merchant of Venice , William Shakespeare

Pages: 2 (670 words)

Views: 2302

- Downloads: -->

Revenge and Justice in the Merchant of Venice (essay)

--> ⚠️ Remember: This essay was written and uploaded by an--> click here.

Found a great essay sample but want a unique one?

are ready to help you with your essay

You won’t be charged yet!

Consider The Lobster Essays

A Modest Proposal Essays

Harrison Bergeron Essays

The Outsiders Essays

The Cask of Amontillado Essays

Related Essays

We are glad that you like it, but you cannot copy from our website. Just insert your email and this sample will be sent to you.

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Your essay sample has been sent.

In fact, there is a way to get an original essay! Turn to our writers and order a plagiarism-free paper.

samplius.com uses cookies to offer you the best service possible.By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .--> -->