An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Types of Study in Medical Research

Part 3 of a Series on Evaluation of Scientific Publications

Bernd Röhrig , Dr. rer. nat.

Jean-baptist du prel , dr. med., daniel wachtlin, maria blettner , prof. dr. rer. nat..

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

*MDK Rheinland-Pfalz, Referat Rehabilitation/Biometrie, Albiger Str. 19 d, 55232 Alzey, Germany, [email protected]

Received 2008 Jun 30; Accepted 2008 Nov 13; Issue date 2009 Apr.

The choice of study type is an important aspect of the design of medical studies. The study design and consequent study type are major determinants of a study’s scientific quality and clinical value.

This article describes the structured classification of studies into two types, primary and secondary, as well as a further subclassification of studies of primary type. This is done on the basis of a selective literature search concerning study types in medical research, in addition to the authors’ own experience.

Three main areas of medical research can be distinguished by study type: basic (experimental), clinical, and epidemiological research. Furthermore, clinical and epidemiological studies can be further subclassified as either interventional or noninterventional.

Conclusions

The study type that can best answer the particular research question at hand must be determined not only on a purely scientific basis, but also in view of the available financial resources, staffing, and practical feasibility (organization, medical prerequisites, number of patients, etc.).

Keywords: study type, basic research, clinical research, epidemiology, literature search

The quality, reliability and possibility of publishing a study are decisively influenced by the selection of a proper study design. The study type is a component of the study design (see the article "Study Design in Medical Research") and must be specified before the study starts. The study type is determined by the question to be answered and decides how useful a scientific study is and how well it can be interpreted. If the wrong study type has been selected, this cannot be rectified once the study has started.

After an earlier publication dealing with aspects of study design, the present article deals with study types in primary and secondary research. The article focuses on study types in primary research. A special article will be devoted to study types in secondary research, such as meta-analyses and reviews. This article covers the classification of individual study types. The conception, implementation, advantages, disadvantages and possibilities of using the different study types are illustrated by examples. The article is based on a selective literature research on study types in medical research, as well as the authors’ own experience.

Classification of study types

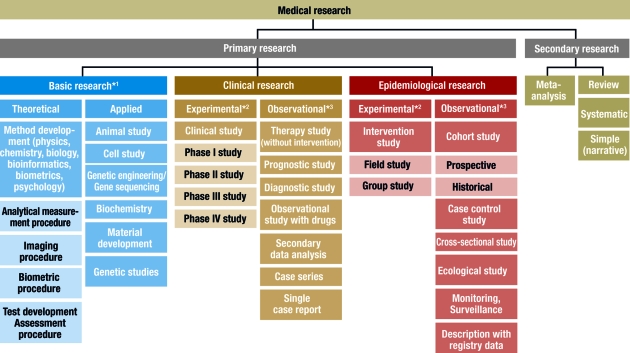

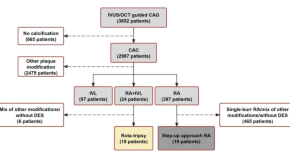

In principle, medical research is classified into primary and secondary research. While secondary research summarizes available studies in the form of reviews and meta-analyses, the actual studies are performed in primary research. Three main areas are distinguished: basic medical research, clinical research, and epidemiological research. In individual cases, it may be difficult to classify individual studies to one of these three main categories or to the subcategories. In the interests of clarity and to avoid excessive length, the authors will dispense with discussing special areas of research, such as health services research, quality assurance, or clinical epidemiology. Figure 1 gives an overview of the different study types in medical research.

Classification of different study types

*1 , sometimes known as experimental research; *2 , analogous term: interventional; *3 , analogous term: noninterventional or nonexperimental

This scheme is intended to classify the study types as clearly as possible. In the interests of clarity, we have excluded clinical epidemiology — a subject which borders on both clinical and epidemiological research ( 3 ). The study types in this area can be found under clinical research and epidemiology.

Basic research

Basic medical research (otherwise known as experimental research) includes animal experiments, cell studies, biochemical, genetic and physiological investigations, and studies on the properties of drugs and materials. In almost all experiments, at least one independent variable is varied and the effects on the dependent variable are investigated. The procedure and the experimental design can be precisely specified and implemented ( 1 ). For example, the population, number of groups, case numbers, treatments and dosages can be exactly specified. It is also important that confounding factors should be specifically controlled or reduced. In experiments, specific hypotheses are investigated and causal statements are made. High internal validity (= unambiguity) is achieved by setting up standardized experimental conditions, with low variability in the units of observation (for example, cells, animals or materials). External validity is a more difficult issue. Laboratory conditions cannot always be directly transferred to normal clinical practice and processes in isolated cells or in animals are not equivalent to those in man (= generalizability) ( 2 ).

Basic research also includes the development and improvement of analytical procedures—such as analytical determination of enzymes, markers or genes—, imaging procedures—such as computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging—, and gene sequencing—such as the link between eye color and specific gene sequences. The development of biometric procedures—such as statistical test procedures, modeling and statistical evaluation strategies—also belongs here.

Clinical studies

Clinical studies include both interventional (or experimental) studies and noninterventional (or observational) studies. A clinical drug study is an interventional clinical study, defined according to §4 Paragraph 23 of the Medicines Act [Arzneimittelgesetz; AMG] as "any study performed on man with the purpose of studying or demonstrating the clinical or pharmacological effects of drugs, to establish side effects, or to investigate absorption, distribution, metabolism or elimination, with the aim of providing clear evidence of the efficacy or safety of the drug."

Interventional studies also include studies on medical devices and studies in which surgical, physical or psychotherapeutic procedures are examined. In contrast to clinical studies, §4 Paragraph 23 of the AMG describes noninterventional studies as follows: "A noninterventional study is a study in the context of which knowledge from the treatment of persons with drugs in accordance with the instructions for use specified in their registration is analyzed using epidemiological methods. The diagnosis, treatment and monitoring are not performed according to a previously specified study protocol, but exclusively according to medical practice."

The aim of an interventional clinical study is to compare treatment procedures within a patient population, which should exhibit as few as possible internal differences, apart from the treatment ( 4 , e1 ). This is to be achieved by appropriate measures, particularly by random allocation of the patients to the groups, thus avoiding bias in the result. Possible therapies include a drug, an operation, the therapeutic use of a medical device such as a stent, or physiotherapy, acupuncture, psychosocial intervention, rehabilitation measures, training or diet. Vaccine studies also count as interventional studies in Germany and are performed as clinical studies according to the AMG.

Interventional clinical studies are subject to a variety of legal and ethical requirements, including the Medicines Act and the Law on Medical Devices. Studies with medical devices must be registered by the responsible authorities, who must also approve studies with drugs. Drug studies also require a favorable ruling from the responsible ethics committee. A study must be performed in accordance with the binding rules of Good Clinical Practice (GCP) ( 5 , e2 – e4 ). For clinical studies on persons capable of giving consent, it is absolutely essential that the patient should sign a declaration of consent (informed consent) ( e2 ). A control group is included in most clinical studies. This group receives another treatment regimen and/or placebo—a therapy without substantial efficacy. The selection of the control group must not only be ethically defensible, but also be suitable for answering the most important questions in the study ( e5 ).

Clinical studies should ideally include randomization, in which the patients are allocated by chance to the therapy arms. This procedure is performed with random numbers or computer algorithms ( 6 – 8 ). Randomization ensures that the patients will be allocated to the different groups in a balanced manner and that possible confounding factors—such as risk factors, comorbidities and genetic variabilities—will be distributed by chance between the groups (structural equivalence) ( 9 , 10 ). Randomization is intended to maximize homogeneity between the groups and prevent, for example, a specific therapy being reserved for patients with a particularly favorable prognosis (such as young patients in good physical condition) ( 11 ).

Blinding is another suitable method to avoid bias. A distinction is made between single and double blinding. With single blinding, the patient is unaware which treatment he is receiving, while, with double blinding, neither the patient nor the investigator knows which treatment is planned. Blinding the patient and investigator excludes possible subjective (even subconscious) influences on the evaluation of a specific therapy (e.g. drug administration versus placebo). Thus, double blinding ensures that the patient or therapy groups are both handled and observed in the same manner. The highest possible degree of blinding should always be selected. The study statistician should also remain blinded until the details of the evaluation have finally been specified.

A well designed clinical study must also include case number planning. This ensures that the assumed therapeutic effect can be recognized as such, with a previously specified statistical probability (statistical power) ( 4 , 6 , 12 ).

It is important for the performance of a clinical trial that it should be carefully planned and that the exact clinical details and methods should be specified in the study protocol ( 13 ). It is, however, also important that the implementation of the study according to the protocol, as well as data collection, must be monitored. For a first class study, data quality must be ensured by double data entry, programming plausibility tests, and evaluation by a biometrician. International recommendations for the reporting of randomized clinical studies can be found in the CONSORT statement (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials, www.consort-statement.org ) ( 14 ). Many journals make this an essential condition for publication.

For all the methodological reasons mentioned above and for ethical reasons, the randomized controlled and blinded clinical trial with case number planning is accepted as the gold standard for testing the efficacy and safety of therapies or drugs ( 4 , e1 , 15 ).

In contrast, noninterventional clinical studies (NIS) are patient-related observational studies, in which patients are given an individually specified therapy. The responsible physician specifies the therapy on the basis of the medical diagnosis and the patient’s wishes. NIS include noninterventional therapeutic studies, prognostic studies, observational drug studies, secondary data analyses, case series and single case analyses ( 13 , 16 ). Similarly to clinical studies, noninterventional therapy studies include comparison between therapies; however, the treatment is exclusively according to the physician’s discretion. The evaluation is often retrospective. Prognostic studies examine the influence of prognostic factors (such as tumor stage, functional state, or body mass index) on the further course of a disease. Diagnostic studies are another class of observational studies, in which either the quality of a diagnostic method is compared to an established method (ideally a gold standard), or an investigator is compared with one or several other investigators (inter-rater comparison) or with himself at different time points (intra-rater comparison) ( e1 ). If an event is very rare (such as a rare disease or an individual course of treatment), a single-case study, or a case series, are possibilities. A case series is a study on a larger patient group with a specific disease. For example, after the discovery of the AIDS virus, the Center for Disease Control (CDC) in the USA collected a case series of 1000 patients, in order to study frequent complications of this infection. The lack of a control group is a disadvantage of case series. For this reason, case series are primarily used for descriptive purposes ( 3 ).

Epidemiological studies

The main point of interest in epidemiological studies is to investigate the distribution and historical changes in the frequency of diseases and the causes for these. Analogously to clinical studies, a distinction is made between experimental and observational epidemiological studies ( 16 , 17 ).

Interventional studies are experimental in character and are further subdivided into field studies (sample from an area, such as a large region or a country) and group studies (sample from a specific group, such as a specific social or ethnic group). One example was the investigation of the iodine supplementation of cooking salt to prevent cretinism in a region with iodine deficiency. On the other hand, many interventions are unsuitable for randomized intervention studies, for ethical, social or political reasons, as the exposure may be harmful to the subjects ( 17 ).

Observational epidemiological studies can be further subdivided into cohort studies (follow-up studies), case control studies, cross-sectional studies (prevalence studies), and ecological studies (correlation studies or studies with aggregated data).

In contrast, studies with only descriptive evaluation are restricted to a simple depiction of the frequency (incidence and prevalence) and distribution of a disease within a population. The objective of the description may also be the regular recording of information (monitoring, surveillance). Registry data are also suited for the description of prevalence and incidence; for example, they are used for national health reports in Germany.

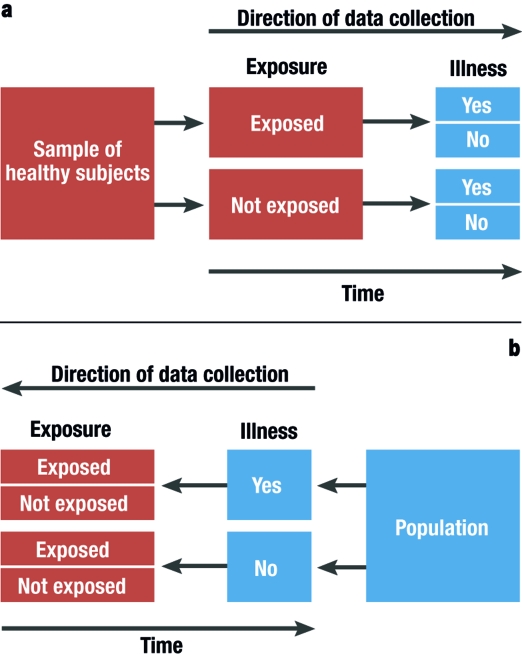

In the simplest case, cohort studies involve the observation of two healthy groups of subjects over time. One group is exposed to a specific substance (for example, workers in a chemical factory) and the other is not exposed. It is recorded prospectively (into the future) how often a specific disease (such as lung cancer) occurs in the two groups ( figure 2a ). The incidence for the occurrence of the disease can be determined for both groups. Moreover, the relative risk (quotient of the incidence rates) is a very important statistical parameter which can be calculated in cohort studies. For rare types of exposure, the general population can be used as controls ( e6 ). All evaluations naturally consider the age and gender distributions in the corresponding cohorts. The objective of cohort studies is to record detailed information on the exposure and on confounding factors, such as the duration of employment, the maximum and the cumulated exposure. One well known cohort study is the British Doctors Study, which prospectively examined the effect of smoking on mortality among British doctors over a period of decades ( e7 ). Cohort studies are well suited for detecting causal connections between exposure and the development of disease. On the other hand, cohort studies often demand a great deal of time, organization, and money. So-called historical cohort studies represent a special case. In this case, all data on exposure and effect (illness) are already available at the start of the study and are analyzed retrospectively. For example, studies of this sort are used to investigate occupational forms of cancer. They are usually cheaper ( 16 ).

Graphical depiction of a prospective cohort study (simplest case [2a]) and a retrospective case control study (2b)

In case control studies, cases are compared with controls. Cases are persons who fall ill from the disease in question. Controls are persons who are not ill, but are otherwise comparable to the cases. A retrospective analysis is performed to establish to what extent persons in the case and control groups were exposed ( figure 2b ). Possible exposure factors include smoking, nutrition and pollutant load. Care should be taken that the intensity and duration of the exposure is analyzed as carefully and in as detailed a manner as possible. If it is observed that ill people are more often exposed than healthy people, it may be concluded that there is a link between the illness and the risk factor. In case control studies, the most important statistical parameter is the odds ratio. Case control studies usually require less time and fewer resources than cohort studies ( 16 ). The disadvantage of case control studies is that the incidence rate (rate of new cases) cannot be calculated. There is also a great risk of bias from the selection of the study population ("selection bias") and from faulty recall ("recall bias") (see too the article "Avoiding Bias in Observational Studies"). Table 1 presents an overview of possible types of epidemiological study ( e8 ). Table 2 summarizes the advantages and disadvantages of observational studies ( 16 ).

Table 1. Specially well suited study types for epidemiological investigations (taken from [ e8 ]).

Table 2. advantages and disadvantages of observational studies (taken from [ 16 ])*..

1 = slight; 2 = moderate; 3 = high; N/A, not applicable.

*Individual cases may deviate from this pattern.

Selecting the correct study type is an important aspect of study design (see "Study Design in Medical Research" in volume 11/2009). However, the scientific questions can only be correctly answered if the study is planned and performed at a qualitatively high level ( e9 ). It is very important to consider or even eliminate possible interfering factors (or confounders), as otherwise the result cannot be adequately interpreted. Confounders are characteristics which influence the target parameters. Although this influence is not of primary interest, it can interfere with the connection between the target parameter and the factors that are of interest. The influence of confounders can be minimized or eliminated by standardizing the procedure, stratification ( 18 ), or adjustment ( 19 ).

The decision as to which study type is suitable to answer a specific primary research question must be based not only on scientific considerations, but also on issues related to resources (personnel and finances), hospital capacity, and practicability. Many epidemiological studies can only be implemented if there is access to registry data. The demands for planning, implementation, and statistical evaluation for observational studies should be just as high for observational studies as for experimental studies. There are particularly strict requirements, with legally based regulations (such as the Medicines Act and Good Clinical Practice), for the planning, implementation, and evaluation of clinical studies. A study protocol must be prepared for both interventional and noninterventional studies ( 6 , 13 ). The study protocol must contain information on the conditions, question to be answered (objective), the methods of measurement, the implementation, organization, study population, data management, case number planning, the biometric evaluation, and the clinical relevance of the question to be answered ( 13 ).

Important and justified ethical considerations may restrict studies with optimal scientific and statistical features. A randomized intervention study under strictly controlled conditions of the effect of exposure to harmful factors (such as smoking, radiation, or a fatty diet) is not possible and not permissible for ethical reasons. Observational studies are a possible alternative to interventional studies, even though observational studies are less reliable and less easy to control ( 17 ).

A medical study should always be published in a peer reviewed journal. Depending on the study type, there are recommendations and checklists for presenting the results. For example, these may include a description of the population, the procedure for missing values and confounders, and information on statistical parameters. Recommendations and guidelines are available for clinical studies ( 14 , 20 , e10 , e11 ), for diagnostic studies ( 21 , 22 , e12 ), and for epidemiological studies ( 23 , e13 ). Since 2004, the WHO has demanded that studies should be registered in a public registry, such as www.controlled-trials.com or www.clinicaltrials.gov . This demand is supported by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) ( 24 ), which specifies that the registration of the study before inclusion of the first subject is an essential condition for the publication of the study results ( e14 ).

When specifying the study type and study design for medical studies, it is essential to collaborate with an experienced biometrician. The quality and reliability of the study can be decisively improved if all important details are planned together ( 12 , 25 ).

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Rodney A. Yeates, M.A., Ph.D.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest in the sense of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

- 1. Bortz J, Döring N. Forschungsmethoden und Evaluation. Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, New York; 2002. pp. 39–84. [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Bortz J, Döring N. Forschungsmethoden und Evaluation. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer; 2002. 37 pp. [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Fletcher RH, Fletcher SW. Klinische Epidemiologie. Grundlagen und Anwendung. Bern: Huber; 2007. pp. 1–327. [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Altman DG. Practical statistics for medical research. 1. Aufl. Boca Raton, London, New York, Washington D.C.: Chapman & Hall; 1991. pp. 1–499. [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Schumacher M, Schulgen G. Methodik klinischer Studien. 2. Aufl. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer; 2007. pp. 1–436. [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Machin D, Campbell MJ, Fayers PM, Pinol APY. Sample size tables for clinical studies. 2. Aufl. Oxford, London, Berlin: Blackwell Science Ltd.; 1987. pp. 1–303. [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Randomization.com: Welcome to randomization.com. http://www.randomization.com/ ; letzte Version: 16. 7. 2008

- 8. Zelen M. The randomization and stratification of patients to clinical trials. J Chronic Dis. 1974;27:365–375. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(74)90015-0. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Altman DG. Randomisation: potential for reducing bias. BMJ. 1991;302:1481–1482. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6791.1481. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Fleiss JL. The design and analysis of clinical experiments. New York, Chichester, Brisbane, Toronto, Singapore: John Wiley & Sons; 1986. pp. 120–148. [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL. Modern Epidemiology. Types of epidemiologic studies: clinical trials. 3rd edition. Philadelphia: LIPPINCOTT Williams & Wilkins; 2008. pp. 89–92. [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Eng J. Sample size estimation: how many individuals should be studied? Radiology. 2003;227:309–313. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2272012051. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Schäfer H, Berger J, Biebler K-E, et al. Empfehlungen für die Erstellung von Studienprotokollen (Studienplänen) für klinische Studien. Informatik, Biometrie und Epidemiologie in Medizin und Biologie. 1999;30:141–154. [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:657–662. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-8-200104170-00011. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Machin D, Campbell MJ. Design of studies for medical research. Chichester: Wiley; 2005. pp. 1–286. [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Beaglehole R, Bonita R, Kjellström T. Einführung in die Epidemiologie. Bern: Verlag Hans Huber; 1997. pp. 1–240. [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL. Modern Epidemiology. Types of epidemiologic studies. 3rd Edition. Philadelphia: LIPPINCOTT Williams & Wilkins; 2008. pp. 87–99. [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Fleiss JL. The design and analysis of clinical experiments. New York, Chichester, Brisbane, Toronto, Singapore: John Wiley & Sons; 1986. pp. 149–185. [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Fleiss JL. The design and analysis of clinical experiments. New York, Chichester, Brisbane, Toronto, Singapore: John Wiley & Sons; 1986. pp. 186–219. [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG. Das CONSORT-Statement: Überarbeitete Empfehlungen zur Qualitätsverbesserung von Reports randomisierter Studien im Parallel-Design. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2004;129:16–20. doi: 10.1007/s00482-004-0380-9. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, et al. Towards complete and accurate reporting of studies of diagnostic accuracy: the STARD initiative. Clin Chem. 2003;49:1–6. doi: 10.1373/49.1.1. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Wald N, Cuckle H. Reporting the assessment of screening and diagnostic tests. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1989;96:389–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1989.tb02411.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453–1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. International Committee of Medical Journals (ICMJE) Clinical trial registration: a statement from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. http://www.icmje.org/clin_trial.pdf ; letzte Version: 22.05.2007

- 25. Altman DG, Gore SM, Gardner MJ, Pocock SJ. Statistical guidelines for contributors to medical journals. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1983;286:1489–1493. doi: 10.1136/bmj.286.6376.1489. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- e1. Neugebauer E, Rothmund M, Lorenz W. The concept, structure and practice of prospective clinical studies. Chirurg. 1989;60:203–213. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- e2. ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline. The International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH); 2008. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- e3. ICH 6: Good Clinical Practice. International Conference on Harmonization; London UK. 1996. adopted by CPMP July 1996 (CPMP/ICH/135/95) [ Google Scholar ]

- e4. ICH 9: Statisticlal Principles for Clinical Trials. International Conference on Harmonization; London UK. 1998. adopted by CPMP July 1998 (CPMP/ICH/363/96) [ Google Scholar ]

- e5. ICH 10: Choice of control group and related issues in clinical trails. International Conference on Harmonization; London UK. 2000. adopted by CPMP July 2000 (CPMP/ICH/363/96) [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- e6. Blettner M, Zeeb H, Auvinen A, et al. Mortality from cancer and other causes among male airline cockpit crew in Europe. Int J Cancer. 2003;106:946–952. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11328. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- e7. Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years’ observations on male British doctors. BMJ. 2004;328:1519–1527. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38142.554479.AE. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- e8. Blettner M, Heuer C, Razum O. Critical reading of epidemiological papers. A guide. Eur J Public Health. 2001;11:97–101. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/11.1.97. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- e9. Juni P, Altman DG, Egger M. Systematic reviews in health care: assessing the quality of controlled clinical trials. BMJ. 2001;323:42–46. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7303.42. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- e10. Begg C, Cho M, Eastwood S, et al. Improving the quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials. The CONSORT statement. JAMA. 1996;276:637–639. doi: 10.1001/jama.276.8.637. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- e11. Novack GD. The CONSORT statement for publication of controlled clinical trials. Ocul Surf. 2004;2:45–46. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70023-x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- e12. Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, et al. The STARD statement for reporting studies of diagnostic accuracy: explanation and elaboration. Clin Chem. 2003;49:7–18. doi: 10.1373/49.1.7. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- e13. Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Epidemiology. 2007;18:805–835. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181577511. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- e14. DeAngelis CD, Razen JM, Frizelle FA, et al. Is this clinical trial fully registered: a statement from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. JAMA. 2005;293:2908–2917. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.23.jed50037. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- e15. Altman DG, Gore SM, Gardner MJ, Pocock SJ. Statistical guidelines for contributors to medical journals. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1983;286:1489–1493. doi: 10.1136/bmj.286.6376.1489. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (238.4 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- Virtual Tour

- Staff Directory

- En Español

You are here

Nih clinical research trials and you, glossary of common terms, clinical research.

Clinical research is medical research that involves people to test new treatments and therapies.

Clinical Trial

A research study in which one or more human subjects are prospectively assigned to one or more interventions (which may include placebo or other control) to evaluate the effects of those interventions on health-related biomedical or behavioral outcomes.

Healthy Volunteer

A Healthy volunteer is a person with no known significant health problems who participates in clinical research to test a new drug, device, or intervention.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria are factors that allow someone to participate in a clinical trial are inclusion criteria . Those that exclude or not allow participation are exclusion criteria .

Informed Consent

Informed consent explains risks and potential benefits about a clinical trial before someone decides whether to participate.

Patient Volunteer

A patient volunteer has a known health problem and participates in research to better understand, diagnose, treat, or cure that disease or condition.

Phases of Clinical Trials

Clinical trials are conducted in “phases.” The trials at each phase have a different purpose and help researchers answer different questions.

- Phase I trials — An experimental drug or treatment in a small group of people (20–80) for the first time. The purpose is to evaluate its safety and identify side effects.

- Phase II trials — The experimental drug or treatment is administered to a larger group of people (100–300) to determine its effectiveness and to further evaluate its safety.

- Phase III trials — The experimental drug or treatment is administered to large groups of people (1,000–3,000) to confirm its effectiveness, monitor side effects, compare it with standard or equivalent treatments.

- Phase IV trials — After a drug is licensed and approved by the FDA researchers track its safety, seeking more information about its risks, benefits, and optimal use.

A placebo is a pill or liquid that looks like the new treatment but does not have any treatment value from active ingredients.

A Protocol is a carefully designed plan to safeguard the participants’ health and answer specific research questions.

Principal Investigator

A Principal Investigator is a doctor who leads the clinical research team and, along with the other members of the research team, regularly monitors study participants’ health to determine the study’s safety and effectiveness.

Randomization

Randomization is the process by which two or more alternative treatments are assigned to volunteers by chance rather than by choice.

Single- or Double-Blind Studies

Single- or double-blind studies (also called single- or double-masked studies) are studies in which the participants do not know which medicine is being used, so they can describe what happens without bias. In single-blind ("single-masked") studies, you are not told what is being given, but the research team knows. In a double-blind study, neither you nor the research team are told what you are given; only the pharmacist knows. Members of the research team are not told which participants are receiving which treatment, in order to reduce bias. If medically necessary, however, it is always possible to find out which treatment you are receiving.

Types of Clinical Trials

- Diagnostic trials determine better tests or procedures for diagnosing a particular disease or condition.

- Natural history studies provide valuable information about how disease and health progress.

- Prevention trials look for better ways to prevent a disease in people who have never had the disease or to prevent the disease from returning.

- Quality of life trials (or supportive care trials) explore and measure ways to improve the comfort and quality of life of people with a chronic illness.

- Screening trials test the best way to detect certain diseases or health conditions.

- Treatment trials test new treatments, new combinations of drugs, or new approaches to surgery or radiation therapy.

This page last reviewed on April 20, 2023

Connect with Us

- More Social Media from NIH

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

Medical research articles from across Nature Portfolio

Medical research involves research in a wide range of fields, such as biology, chemistry, pharmacology and toxicology with the goal of developing new medicines or medical procedures or improving the application of those already available. It can be viewed as encompassing preclinical research (for example, in cellular systems and animal models) and clinical research (for example, clinical trials).

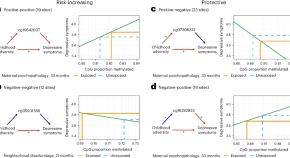

Childhood adversity may cause epigenetic changes that increase or suppress depression risk

We showed, in multiple population-based birth cohorts, that blood-based DNA methylation partially explains the relationship between childhood adversity and adolescent depressive symptoms. DNA-methylation sites across the epigenome could explain an increased risk of depression but, unexpectedly, other sites also served as markers of resilience against the effects of childhood adversity on depression risk.

Conference report of the 2024 Antimicrobial Resistance Meeting

The Antimicrobial Resistance - Genomes, Big Data and Emerging Technologies Conference explored key topics including measuring the burden of AMR, global public health pathogen genomics infrastructure and surveillance, translation and implementation of genomics for AMR control, use of techniques such as wastewater surveillance, mathematical and statistical modelling, and Artificial Intelligence (AI) to aid understanding of AMR. This report describes research presented during plenary sessions and discussions, keynote presentations and posters.

- Charlotte E. Chong

- Thi Mui Pham

- Kate S. Baker

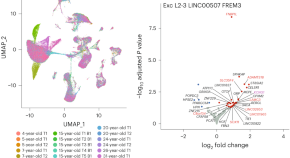

Exploring gene expression in the maturing human brain at the single-cell level

Advancements in single-cell analysis technologies are enabling exploration of the intricacies of the human brain at unprecedented resolution. However, most research thus far has focused on the adult brain. Here, these tools are applied to reveal cell-type-specific gene-expression dynamics as the brain grows from childhood to adulthood.

Related Subjects

- Drug development

- Epidemiology

- Experimental models of disease

- Genetics research

- Outcomes research

- Paediatric research

- Preclinical research

- Stem-cell research

- Clinical trial design

- Translational research

Latest Research and Reviews

Neutrophil-based single-cell sequencing combined with transcriptome sequencing to explore a prognostic model of sepsis

- Simiao Chen

Rota-Tripsy or step-up-approach rotational atherectomy for severe coronary artery calcification treatment: a comparative effectiveness study

- Fengwen Cui

- Yaliang Tong

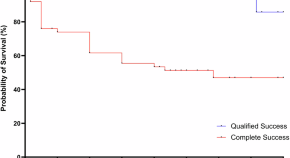

The PAUL Glaucoma Implant in the management of uveitic glaucoma—3-year follow-up

- Jay Richardson

- Filofteia Tacea

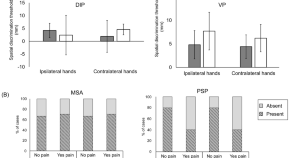

Spatial discrimination in patients with MSA, PSP, DIP, and VP with pain

- Min Seung Kim

- Suk Yun Kang

Association between oxidative stress and postoperative delirium in joint replacement using diacron-reactive oxygen metabolites and biological antioxidant potential tests

- Yoshihisa Koyama

- Shoichi Shimada

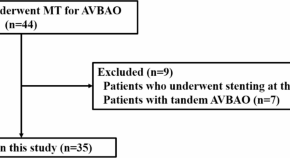

Impact of tortuosity of the V1-segment vertebral artery on mechanical thrombectomy

- Zhoucheng Kang

- Hanghang Zhao

News and Comment

Advancing keratoconus treatment: the impact of bioengineered porcine constructs on corneal reshaping and visual acuity.

- Maliha Khan

- Duaa Fatima

Intraocular endothelial Keratogel Device for protection corneal endothelium during phacoemulsification cataract surgery

- Rashmi Deshmukh

- Rasik B. Vajpayee

Hepatic vagus nerve relays signals to the brain that can alter food intake

- Rebecca Kelsey

Advancing the state of the art in congenital obstructive uropathy

In March 2024, we convened a symposium to consider the state of the art regarding the mechanisms and management of congenital obstructive uropathy caused by bladder outlet obstruction, at which overarching themes emerged and opportunities for research were discussed to fill key knowledge gaps in achieving the best future for children with congenital obstructive uropathy.

- Ashley R. Jackson

- Nathalia G. Amado

- Brian Becknell

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Participating in Health Research Studies

What is health research.

- Is Health Research Safe?

- Is Health Research Right for Me?

- Types of Health Research

The term "health research," sometimes also called "medical research" or "clinical research," refers to research that is done to learn more about human health. Health research also aims to find better ways to prevent and treat disease. Health research is an important way to help improve the care and treatment of people worldwide.

Have you ever wondered how certain drugs can cure or help treat illness? For instance, you might have wondered how aspirin helps reduce pain. Well, health research begins with questions that have not been answered yet such as:

"Does a certain drug improve health?"

To gain more knowledge about illness and how the human body and mind work, volunteers can help researchers answer questions about health in studies of an illness. Studies might involve testing new drugs, vaccines, surgical procedures, or medical devices in clinical trials . For this reason, health research can involve known and unknown risks. To answer questions correctly, safely, and according to the best methods, researchers have detailed plans for the research and procedures that are part of any study. These procedures are called "protocols."

An example of a research protocol includes the process for determining participation in a study. A person might meet certain conditions, called "inclusion criteria," if they have the required characteristics for a study. A study on menopause may require participants to be female. On the other hand, a person might not be able to enroll in a study if they do not meet these criteria based on "exclusion criteria." A male may not be able to enroll in a study on menopause. These criteria are part of all research protocols. Study requirements are listed in the description of the study.

A Brief History

While a few studies of disease were done using a scientific approach as far back as the 14th Century, the era of modern health research started after World War II with early studies of antibiotics. Since then, health research and clinical trials have been essential for the development of more than 1,000 Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved drugs. These drugs help treat infections, manage long term or chronic illness, and prolong the life of patients with cancer and HIV.

Sound research demands a clear consent process. Public knowledge of the potential abuses of medical research arose after the severe misconduct of research in Germany during World War II. This resulted in rules to ensure that volunteers freely agree, or give "consent," to any study they are involved in. To give consent, one should have clear knowledge about the study process explained by study staff. Additional safeguards for volunteers were also written in the Nuremberg Code and the Declaration of Helsinki .

New rules and regulations to protect research volunteers and to eliminate ethical violations have also been put in to place after the Tuskegee trial . In this unfortunate study, African American patients with syphilis were denied known treatment so that researchers could study the history of the illness. With these added protections, health research has brought new drugs and treatments to patients worldwide. Thus, health research has found cures to many diseases and helped manage many others.

Why is Health Research Important?

The development of new medical treatments and cures would not happen without health research and the active role of research volunteers. Behind every discovery of a new medicine and treatment are thousands of people who were involved in health research. Thanks to the advances in medical care and public health, we now live on average 10 years longer than in the 1960's and 20 years longer than in the 1930's. Without research, many diseases that can now be treated would cripple people or result in early death. New drugs, new ways to treat old and new illnesses, and new ways to prevent diseases in people at risk of developing them, can only result from health research.

Before health research was a part of health care, doctors would choose medical treatments based on their best guesses, and they were often wrong. Now, health research takes the guesswork out. In fact, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires that all new medicines are fully tested before doctors can prescribe them. Many things that we now take for granted are the result of medical studies that have been done in the past. For instance, blood pressure pills, vaccines to prevent infectious diseases, transplant surgery, and chemotherapy are all the result of research.

Medical research often seems much like standard medical care, but it has a distinct goal. Medical care is the way that your doctors treat your illness or injury. Its only purpose is to make you feel better and you receive direct benefits. On the other hand, medical research studies are done to learn about and to improve current treatments. We all benefit from the new knowledge that is gained in the form of new drugs, vaccines, medical devices (such as pacemakers) and surgeries. However, it is crucial to know that volunteers do not always receive any direct benefits from being in a study. It is not known if the treatment or drug being studied is better, the same, or even worse than what is now used. If this was known, there would be no need for any medical studies.

- Next: Is Health Research Safe? >>

- Last Updated: May 27, 2020 3:05 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/healthresearch

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

National Research Council (US) Committee for Monitoring the Nation's Changing Needs for Biomedical, Behavioral, and Clinical Personnel. Advancing the Nation's Health Needs: NIH Research Training Programs. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2005.

Advancing the Nation's Health Needs: NIH Research Training Programs.

- Hardcopy Version at National Academies Press

2 Basic Biomedical Sciences Research

Basic biomedical research, which addresses mechanisms that underlie the formation and function of living organisms, ranging from the study of single molecules to complex integrated functions of humans, contributes profoundly to our knowledge of how disease, trauma, or genetic defects alter normal physiological and behavioral processes. Recent advances in molecular biology techniques and characterization of the human genome, as well as the genomes of an increasing number of model organisms, have provided basic biomedical researchers with the tools to elucidate molecular-, cellular-, and systems-level processes at an unprecedented depth and rate.

Thus basic biomedical research affects clinical research and vice versa. Biomedical researchers supply many of the new ideas that can be translated into potential therapies and subsequently tested in clinical studies, while clinical researchers may suggest novel mechanisms of disease that can then be tested in basic studies using animal models.

The tools also now exist to rapidly apply insights gained from model organisms to human health and disease. For example, gene mutations known to contribute to human disease can be investigated in model organisms, whose underlying characteristics lend them to rapid assessment. Resulting treatment strategies can then be tested in mammalian species prior to the design of human clinical trials.

These and other mutually supportive systems suggest that such interactions between basic biomedical and clinical researchers not only will continue but will grow as the two domains keep expanding. But the two corresponding workforces will likely remain, for the most part, distinct.

Similarly, there is a symbiosis between basic biomedical and behavioral and social sciences research (covered in Chapter 3 ) and an obvious overlap at the interface of neuroscience, physiological psychology, and behavior. The boundary between these areas is likely to remain indistinct as genetic and environmental influences that affect brain formation and function are better understood. Consequently, such investigations will impact the study of higher cognitive functions, motivation, and other areas traditionally studied by behavioral and social scientists.

Basic biomedical research will therefore undoubtedly continue to play a central role in the discovery of novel mechanisms underlying human disease and in the elucidation of those suggested by clinical studies. As an example, although a number of genes that contribute to disorders such as Huntington's, Parkinson's, and Alzheimer's disease have been identified, the development of successful therapies will require an understanding of the role that the proteins encoded by these genes play in normal cellular processes. Similarly, realizing the potential of stem cell–based therapies for a number of disorders will require characterization of the signals that cause stem cells to differentiate into specific cell types. Thus a workforce trained in basic biomedical research will be needed to apply current knowledge and that gained in the future toward the improvement of human health. Since such research will be carried out not only in academic institutions but increasingly in industry as well, the workforce must be sufficient to supply basic biomedical researchers for large pharmaceutical companies as well as smaller biotech and bioengineering firms, thereby contributing to the economy as well as human health.

The role of the independent investigator in academe, industry, and government is crucial to this research enterprise. They provide the ideas that expand knowledge and the research that leads to discovery. The doubling of the NIH budget has increased the number of research grants and the number of investigators but not at a rate commensurate to the budget increases. Grants have become bigger and senior investigators have received more of them. While this trend has not decreased the nation's research capacity, there may be things that will affect the future pool of independent researchers, such as a sufficient number of academic faculty that can apply for research grants, an industrial workforce that is more application oriented, and most important, a decline in doctorates from U.S. institutions.

- BIOMEDICAL RESEARCH WORKFORCE

The research workforce for the biomedical sciences is broad and diverse. It is primarily composed of individuals who hold Ph.D.s, though it also includes individuals with broader educational backgrounds, such as those who have earned their M.D.s from the Medical Scientist Training Program (MSTP) or other dual-degree programs. In addition, some individuals with M.D.s but without Ph.D.s have acquired the necessary training to do basic biomedical research. But although the analysis in this report should ideally be based on the entire workforce just defined, there are no comprehensive databases that identify the research activities of M.D.s. Therefore much of the analysis will be restricted to holders of a Ph.D. in one of the fields listed in Appendix C , with the assumption that an individual's area of research is related to his or her degree field. A separate section in this chapter is devoted to M.D.s doing biomedical research, and an analysis of the clinical research M.D. workforce is given in Chapter 4 .

It should also be noted that the discussion in this chapter does not include individuals with doctorates in other professions, such as dentistry and nursing even if they hold a Ph.D. in addition to their professional degrees. However, there are important workforce issues in these two fields, and they are addressed separately in Chapters 5 and 6 of this report.

- EDUCATIONAL PROGRESSION

The major sources of Ph.D. researchers in the biomedical sciences are the U.S. research universities, but a substantial number also come from foreign institutions. These scientists, whether native or foreign born, enter the U.S. biomedical research workforce either directly into permanent assignments or via postdoctoral positions.

For most doctorates in the biomedical sciences, interest in the field begins at an early age, in high school or even grade school. In fact, almost all high school graduates (93 percent) in the class of 1998 took a biology course—a rate much greater than other science fields, for which the percentages are below 60 percent. 1 Even in the early 1980s, over 75 percent of high school graduates had taken biology, compared to about 30 percent for chemistry, which had the next-highest enrollment. This interest in biology continues into college, with 7.3 percent of the 2000 freshman science and engineering (S&E) population having declared a major in biology. This was an increase from about 6 percent of freshman majors in the early 1980s but less than the high of about 9.5 percent in the mid-1990s. Overall, the number of freshman biology majors increased from about 50,000 in the early 1980s to over 73,000 in 2000. 2 In terms of actual bachelor's degrees awarded in the biological sciences, there was a decrease from about 47,000 in 1980 to 37,000 in 1989 and then a relatively sharp rise to over 67,000 in 1998. This was followed by a slight decline to about 65,000 in 2000.

There is attrition, however, in the transition from undergraduate to graduate school. In the 1980s and 1990s only about 11,000 first-year students were enrolled at any one time in graduate school biology programs. Percentage-wise, this loss of students is greater than in other S&E fields but is understandable: many undergraduates obtain a bachelor's degree in biology as a precursor to medical school and have no intention of graduate study in biology per se. The total graduate enrollment in biomedical sciences at Ph.D.-granting institutions grew in the early 1990s and was steady at a little under 50,000 during the latter part of the decade. However, there was some growth in 2001, of about 4 percent over the 2000 level, and the growth from 2000 to 2002 was about 10 percent (see Figure 2-1 ), driven in large part by an 18.9 percent increase of temporary residents. The overall growth may not continue, however, as the first-year enrollment for this group slowed from 8.9 percent in 2001 to 3.0 percent in 2002.

First-year and total graduate enrollment in the biomedical sciences at Ph.D.-granting institutions, 1980–2002. SOURCE: National Science Foundation Survey of Graduate Students and Postdoctorates in Science and Engineering.

The tendency for graduate students to receive a doctorate in a field similar to that of their baccalaureate degree is not as strong in the biomedical sciences as it is in other fields, where it is about 85 percent. From 1993 to 2002, some 68.4 percent of the doctorates in biomedical programs received their bachelor's degree in the same field and another 8.4 percent received bachelor's degrees in chemistry. 3 This relative tendency to shift fields should not be viewed negatively, however, as doctoral students with exposure to other disciplines at the undergraduate level could provide the opportunity for greater interdisciplinary training and research.

- EARLY CAREER PROGRESSION IN THE BIOMEDICAL SCIENCES

Advances in biomedical research and health care delivery, together with a strong economy in the 1990s and increased R&D support, drove the growth of academic programs. Total academic R&D expenditures in the biological sciences, in 2001 dollars, began to rise dramatically in the early 1980s. They started from a base of about $3 billion and reached a plateau of almost $5 billion in the mid-1990s. As seen in Figure 2-2 , this increase of about $2 billion was virtually repeated in the much shorter period from the late 1990s to 2002, as the NIH budget doubled. Although the increases in R&D support during the earlier period were reflected in the increased graduate enrollments of the 1980s and mid-1990s (seen in Figure 2-1 ), the enrollments since then have not kept pace with fast-growing R&D expenditures. This disconnect between research funding and enrollment in the late 1990s is difficult to explain but could in part be due to the unsettled career prospects in the biomedical sciences. In a report 4 from the American Society for Cell Biology, the authors examined the data on enrollment and surveyed both undergraduate and graduate students and postdoctorates on their career goals and found that students were aware of and concerned about the problem young people were having in establishing an independent research career. This ASCB report, as well as in the National Research Council report, Trends in the Early Careers of Life Scientists, 5 express concern for the future of biomedical research, if the best young people pursue different career paths. This slowdown in graduate enrollment in the late 1990s might have also contributed to the expansion of the postdoctoral and non-tenure-track faculty pool of researchers, since there was an increasing need for research personnel.

Academic research and development expenditures in the biological sciences. (All dollars are in thousands.) SOURCE: National Science Foundation R&D Expenditures at Universities and Colleges, 1973–2002. Adjusted to 2002 dollars by the Biomedical (more...)

The increase in funding and enrollments in the early 1990s did lead to an increase in doctoral degrees awarded in the late 1990s, as seen in Figure 2-3 . Since the 1970s, Ph.D.s awarded by U.S. institutions in the biomedical sciences increased from roughly 3,000 then to 5,366 in 2002. Most of the increase occurred in the mid-1990s and has since remained fairly constant. The year with the largest number of doctorates was 2000, when 5,532 degrees were awarded. The number of degrees in 2000 may be an anomaly, since the number in 2001 (5,397 Ph.D.), 2002 (5,375 Ph.D.), and 2003 (5,412 Ph.D.) are more in line with the number in the late 1990s (see Appendix Table E-1 ).

Number of doctorates in the biomedical sciences, 1970–2003. SOURCE: National Science Foundation Survey of Earned Doctorates, 2001.

Increases in doctorates were seen among women, temporary residents, and underrepresented minorities. Notably, since 1986 much of the increase in the number of doctorates has come from increased participation by women. In 1970 only 16 percent of doctorates were awarded to women; by 2003 the percentage had grown to 45.2. Temporary residents earned about 10 percent of the doctorates in 1970, and although this had increased to almost one-quarter in the early 2000s, it was still lower than the percentage awarded in many other fields in the physical sciences and engineering. Participation by underrepresented minorities in 2003 stood at 9.4 percent—as in many other S&E fields, substantially below their representation in the general population.

The percentage of doctorates with definite postdoctoral study plans increased from about 50 percent in the early 1970s to a high of 79 percent in 1995. It then declined to 71 percent in 2002 but increased to 75 percent in 2003. The changes in doctorates electing postdoctoral study are reflected in those choosing employment after they received their degrees (from 20 percent in 1995 to 28 percent in 2002 and 25 percent in 2003). It is difficult to find reasons for these changes in career plans. Prior to 2003 it may be the result of more diverse and attractive employment opportunities generated by recent advances in the applied biological sciences, especially in industry, or a conscious choice not to pursue an academic research career, where postdoctoral training is required since an academic position may not be available down the road. The increase in postdoctoral appointments in 2003 and the decline in employment might be due to poor economic conditions in the early part of this decade. Whether these changes will impact the quality of the biomedical workforce and its research should be monitored.

Time to degree, age at receipt of degree, and the long training period prior to reaching R01 research status have been cited as critical issues in the career progression of biomedical researchers. 6 Graduate students are taking longer and longer periods of time to earn their Ph.Ds. The median registered time in a graduate degree program gradually increased from 5.4 years in 1970 to 6.7 years in 2003, and the median age of a newly minted degree holder in the biomedical sciences grew during the same period—from 28.9 in 1970 to 30.6 in 2003 (see Appendix E ). It should be noted that this time to degree is shorter than those of such fields as physics, computer science, and the earth sciences. Only chemistry, mathematics, and engineering have a lower median age at time of degree. While shortening the time in graduate school would reduce the age at which doctorates could become independent investigators, it may not significantly affect their career paths since postdoctoral training is required of almost all researchers in the biomedical sciences, and the time spent in these positions seems to be lengthening.

With the growth of research funding and productivity in the biomedical sciences, the postdoctoral appointment has become a normal part of research training. From the 1980s to the late 1990s, the number of postdoctoral appointments doubled for doctorates from U.S. educational institutions (see Figure 2-4 ). The rapid increase in the postdoctoral pool from 1993 to 1999 in particular appears to be the result of longer training periods for individuals and not the result of an increase in the number of individuals being trained since Table E-1 shows a decline in the number of new doctorates planning postdoctoral study and the number of doctorates has remained fairly constant over recent years.

Postdoctoral appointments in the biomedical sciences by sector, 1973–2001. SOURCE: National Science Foundation Survey of Doctorate Recipients.

The lengthening of postdoctoral training is documented by data collected in 1995 on the employment history of doctorates. 7 Of the Ph.D.s who pursued postdoctoral study after graduating in the early 1970s, about 35 percent spent less than two years and about 65 percent spent more than 2 years in a postdoctoral appointment. By contrast, of Ph.D.s who received their degrees in the late 1980s and completed postdoctorates in the 1990s, 80 percent spent more than two years and 20 percent spent less than 2 years in such appointments. More indicative of the change in postdoctoral training was the increase in the proportion that spent more than 4 years in a position, from about 20 percent to nearly 40 percent.

In 2001 the number of postdoctoral appointments actually declined across all employment sectors. This decline might be the result of lower interest by new doctorates in postdoctoral study and an academic career but is probably a response to the highlighting of issues related to postdoctoral appointments, such as the long periods of training with lack of employment benefits, the general perception that the positions are more like low-paying jobs than training experiences, and the poor prospects of a follow-up position as an independent investigator. Not only is interest in postdoctoral positions declining, there appears to be more rapid movement out of them by present incumbents. (These phenomena are more fully explored in Chapter 9 , Career Progression.)

The above discussion applies only to U.S. doctorates. There are also a large number of individuals with Ph.D.s from foreign institutions being trained in postdoctoral positions in U.S. educational institutions and other employment sectors. Data from another source are available for postdoctorates from this population at academic institutions, 8 but there is no source for data in the industrial, governmental, and nonprofit sectors other than an estimate that about half of the 4,000 intramural postdoctoral appointments at NIH are held by temporary residents. Almost all of these temporary residents have foreign doctorates. The number of temporary residents in academic institutions steadily increased through the 1980s and 1990s until 2002 when the number reached 10,000 (see Figure 2-5 ). The data also show that the rate at which temporary residents took postdoctoral positions slowed in 2002. The decline in academic appointments in 2001 for U.S. citizens and permanent residents population that was described above is also seen in this data, but that might be temporary since there was an increase in 2002. The reasons for this change may be twofold: a tighter employment market for citizens and permanent residents and immigration restrictions. However, it is still important to recognize that foreign-educated researchers hold about two-thirds of the postdoctoral positions in academic institutions. If national security policies were to limit the flow of foreign scientists into the United States, this could adversely affect the research enterprise in the biomedical sciences.

Postdoctoral appointments in academic institutions in the biomedical sciences. SOURCE: National Science Foundation Survey of Graduate Students and Postdoctorates in Science and Engineering.

- A PORTRAIT OF THE WORKFORCE

The traditional career progression for biomedical scientists after graduate school includes a postdoctoral position followed by an academic appointment, either a tenure-track or nonpermanent appointment that is often on “soft” research money. As shown in Figure 2-6 , the total population of academic biomedical sciences researchers, excluding postdoctoral positions, grew at an average annual rate of 3.1 percent from 1975 to 1989. 9

Academic positions for doctorates in the biomedical sciences, 1975–2001. SOURCE: National Science Foundation Survey of Doctorate Recipients.

Since 1995, growth slowed to about 2.5 percent, with almost all of the growth in the non-tenure-track area. From 1999 to 2001 there was actually a decline in the number of non-tenure-track positions (by a few hundred). The fastest-growing employment category since the early 1980s has been “Other Academic Appointments,” which is currently increasing at about 4.9 percent annually (see Appendix E-2 ). These jobs are essentially holding positions, filled by young researchers, coming from postdoctoral experiences, who would like to join an academic faculty on a tenure track and are willing to wait. In effect, they are gambling because institutions are restricting the number of faculty appointments in order to reduce the possible long-term commitments that come with such positions. From 1993 to 2001, the number of tenure-track appointments increased by only 13.8 percent, while those for non-tenure-track faculty and other academic appointments increased by 45.1 percent and 38.9 percent, respectively.

The longer time to independent research status is also seen by looking at the age distributions of tenure-track faculty over the past two decades (see Figure 2-7 ). By comparing age cohorts in 1985 and 2001, it is observed that doctorates entered tenure-track positions at a later age in 2001.

Age distribution of biomedical tenured and tenure-track faculty, 1985, 1993, and 2001. SOURCE: National Science Foundation Survey of Doctorate Recipients.

For example, while about 1,000 doctorates in the 33 to 34 age cohort were in faculty positions in 1985, only about half that number were similarly employed in 2001, even though the number of doctorates for that cohort was greater in the late 1990s than in the early 1980s. The age cohort data also show that the academic workforce is aging, with about 20 percent of the 2001 academic workforce over the age of 58. The constraints of a rather young biomedical academic workforce and the conservative attitudes of institutions to not expand their faculties in the tight economic times of the early 1990s may have slowed the progression of young researchers into research positions. However, this may change in the next 8 to 10 years as more faculty members retire.

Meanwhile, over 40 percent of the biomedical sciences workforce is employed in nonacademic institutions (see Figure 2-8 ). Researchers' employment in industry, the largest of these other sectors, has been growing at a 15 percent rate over the past 20 years. There was a lull in employment in the early 1990s, but growth since the mid-1990s has been strong. The increases in industrial employment may be due to the unavailability of faculty positions, but is more likely fueled by the R&D growth in pharmaceutical and other medical industries from $9.3 billion in 1992 to $24.6 in 2001 (constant 2001 dollars). 10 In 1992 almost all of this funding was from nonfederal sources, but in 2001 only 42 percent was from those sources. The result of this increase in federal funding has resulted in an increase in R&D employment, but not as large as would be expected. It is difficult to estimate the increase in biomedical doctorates in this industrial sector since they are drawn from many fields and are at different degree levels, but the total full-time equivalent R&D scientists and engineers increased 6.2 percent from 38,700 in 1992 to 41,100 in 2001. 11 However, there may be a trend toward increased employment in this sector, since a growing fraction of new doctorates are planning industrial employment (see Table E-1 ). The downturn in 2003 may be an anomaly due to the economy and not the strength of the medical industry, but data from a longer time period will be needed before definite trends in industrial employment can be determined. The government and nonprofit sectors have been fairly stable in their use of biomedical scientists, with about 8 and 4 percent growth rates, respectively, in recent years.

Employment of biomedical scientists by sector, 1973–2001. SOURCE: National Science Foundation Survey of Doctorate Recipients.

The number of underrepresented minorities in the basic biomedical sciences workforce increased from 1,066 in 1975 to 5,345 in 2001 and now accounts for 5.3 percent of the research employment in the field. Even though the annual average rate of growth for minorities in the workforce has been 15 percent over the past 10 years—more than twice the growth rate of the total workforce (6.5 percent)—the overall representation of minorities in biomedical research is still a small percentage of the overall workforce (see Appendix E-2 ). Their representation is also important from the scientific perspective, since researchers from minority groups may be better able and willing to address minority health care issues.

- PHYSICIAN-RESEARCHERS

Throughout this report Ph.D.s are considered to be researchers or potential researchers, but no such assumption is made of M.D.s because they could be practitioners. The above discussion, in particular, applies only to Ph.D.s in the fields listed in Appendix C , but it does not take into consideration physicians who are doing basic biomedical research. It is difficult to get a complete picture of this workforce because there is no database that tracks M.D.s involved in such activity, but a partial picture can be obtained from NIH files on R01 awards.

In 2001, R01 grants were awarded to 4,383 M.D.s (and to 17,505 Ph.D.s). 12 The number of R01-supported M.D. researchers has been increasing over the years (see Table 2-1 ) but has remained at about 20 percent. This means that the size of the biomedical workforce could be as much as one-fifth larger than indicated above. In fact, since NIH began to classify clinical research awards in 1996, it has become evident that both M.D.s and M.D./Ph.D.s supported by the agency are more likely to conduct nonclinical—that is, biomedical—than clinical research. Because many physician-investigators approach nonclinical research with the goal of understanding the mechanisms underlying a particular disease or disorder, their findings are likely to ultimately contribute to improvements in human health.

Number of M.D.s and Ph.D.s with Grant Support from NIH .

Some data are available from the American Medical Association on the national supply of physicians potentially in research. In 2002 there were 15,316 medical school faculty members in basic science departments and 82,623 in clinical departments. Of those in basic science, 2,255 had M.D. degrees, 11,471 had Ph.D.s, and 1,128 had combined M.D./ Ph.D. degrees. To identify the M.D.s in basic science departments who were actually doing research, the Association of American Medical Colleges Faculty Roster was linked to NIH records; it found that 1,261 M.D.s had been supported as principal investigators (PIs) on an R01 NIH grant at some point. This number is clearly an undercount of the M.D. research population, however, given that there are forms of NIH research support other than PI status and non-NIH organizations also support biomedical research.

- THE NATIONAL RESEARCH SERVICE AWARD PROGRAM AND BIOMEDICAL TRAINING SUPPORT

The National Research Service Award Program

In 1975, when the National Research Service Award (NRSA) program began, 23,968 graduate students in the basic biomedical sciences received some form of financial assistance for their studies, and about 8,000 supported their own education through loans, savings, or family funds. 13 The number of fellowships and traineeships, whether institutional or from external sources, was about 8,500 in 1975 and remained at about that level into the early 1990s, increasing only recently to 12,186 in 2002 (see Figure 2-9 ).

Mechanisms of support for full-time graduate students in the biomedical sciences, 1979–2002. SOURCE: National Science Foundation Survey of Graduate Students and Postdoctorates in Science and Engineering.

In the 1970s the majority of graduate student support came from these fellowships, traineeships, and institutional teaching assistantships. The picture began to change in the early 1980s as the prevalence of research grants grew. By 2002 it represented almost 50 percent of the support for graduate study in the biomedical sciences, and NIH's funding of this mechanism grew as well. In the early 1980s, NIH research grants formed about 40 percent of the total, and by the early 1990s this fraction grew to 64 percent and has remained at about this level through 2002 (see Figure 2-10 ). Even during the years when the NIH budget doubled, there was not a shift in this balance. In fact, from 1997 to 2002 both research grant and trainee/fellowship support from NIH increased by 14 percent. NIH in its response to the 2000 assessment of the NRSA program 14 has stated that research grants and trainee/fellowship awards are not used for the control of graduate support and that it would be inappropriate to try to do so.

FIGURE 2-10

Graduate support for NIH, 1979–2002. SOURCE: National Science Foundation Survey of Graduate Students and Postdoctorates in Science and Engineering.

The NRSA program now comprises the major part of NIH's fellowship and traineeship support. It began small in 1975—with 1,046 traineeships and 26 fellowships—but quickly expanded. By 1980 the number was nearly 5,000 for the traineeships; it remained at that level until 2001, though it dropped to a little over 4,000 in 2002 (see Table 2-2 ). (The drop in 2002 traineeships was probably an institutional reporting issue. Given that the total number of awards by NIH under the T32 15 mechanisms was about the same as in 2001, it is unlikely that the awards in the biomedical sciences would fall below the 2000 or 2001 levels.)

NRSA Predoctoral Trainee and Fellowship Support in the Basic Biomedical Sciences .

Information on funding patterns for postdoctorates in the basic biomedical sciences is not as complete as that for graduate students since academic institutions are the only sources of data. As has been the case for graduate student support, the portion of federal funds devoted to postdoctoral training grants and fellowships has diminished since the 1970s. In 1995, 1,966 (or 45.3 percent) of the 4,343 federally funded university-based postdoctorates received their training on a fellowship or traineeship. By 2002 the number had increased to 2,670 but was still only 20.3 percent of the total federal funding. The remaining 79.7 percent (or 10,514) in 2002 were supported by federal research grants. Meanwhile, the number of postdoctoral positions, funded by nonfederal institutional sources, was fairly constant at about 25 percent and grew from 1,325 in 1975 to 4,628 in 2002.

The picture for NRSA support at the postdoctoral level for the period following introduction of the NRSA program resembled that of the graduate level. However, in 2002 there was a sharp decrease in the number of postdoctoral traineeships; but, as in the case for predoctoral trainees, this may be an institutional reporting issue (see Table 2-3 ). Since the decline from 2001 to 2002 is nearly 50 percent and the decline for predoctoral trainees was only 20 percent, there may be a real decline at the postdoctoral level. The reason for this is unclear, though factors may include the limited number of individuals who can be supported under the increased stipend levels and the general decline in the number of postdoctoral research trainees eligible for NRSA support.

NRSA Postdoctoral Trainee and Fellowship Support in the Basic Biomedical Sciences .

The shift in the pattern of federal research training support, at both the graduate and postdoctoral levels, can be traced to a number of related trends. Over the past 25 years, the number of research grants awarded by the NIH and other agencies of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has more than doubled. 16 PIs have come to depend on graduate students and postdoctorates to carry out much of their day-to-day research work, and, as a result, the number of universities awarding Ph.D.s in the basic biomedical sciences, as well as the quantity of Ph.D.s awarded by existing programs, has grown.