Home — Essay Samples — Entertainment — Movie Review — Lincoln Movie Reflection

Lincoln Movie Reflection

- Categories: Movie Review

About this sample

Words: 680 |

Updated: 15 November, 2024

Words: 680 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Table of contents

Complexity of character, moral dilemmas and ethical considerations, historical accuracy.

- Seward, W.H., & Jones T.L., Stevens: Roles in Leadership Dynamics (2013).

- Spielberg S., Director: Historical Representation Techniques (2015).

- Doris Kearns Goodwin: Team Of Rivals – Film Influence On Public Perception (2016).

- Kushner T., Screenwriter Insights: Dialogue Crafting Approach Within Biopics (2017).

- Day-Lewis D., Character Embodiment Methods Throughout Cinematic Portrayals(2018).

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Entertainment

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

4 pages / 1978 words

1 pages / 656 words

3 pages / 1411 words

2 pages / 925 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Movie Review

In the iconic film "Wall Street," Gordon Gekko's speech on greed has become a timeless cultural reference, sparking endless debates on the ethics of capitalism. As we delve into an analysis of this powerful monologue, we are [...]

Silver Linings Playbook is a film directed by David O. Russell that showcases the story of Pat Solatano played by Bradley Cooper. The story has Pat Solatano as a protagonist who struggles to deal with his mental illness after [...]

In the charming and feel-good movie "Benny and Joon," directed by Jeremiah S. Chechik, we meet some really unique and lovable characters. The story mainly revolves around Benny and Joon, who are siblings with a pretty [...]

Marvel's "Black Panther" made history in 2018 as the first major superhero film with a predominantly African-American cast, and its impact on popular culture was impossible to ignore. Beyond its groundbreaking representation, [...]

Rebel archetypes in movies are portrayed as the mean person or character that does not care about any rules they are being told.when you hear rebel people assume they are talking about a bad person or the villian but really it [...]

Introduction of the movie "Fight Club" and its initial reception Mention of the movie's actual genre and surprise ending Brief summary of the movie's plot, including the protagonist's transformation into Tyler [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

A saintly wheeler-dealer

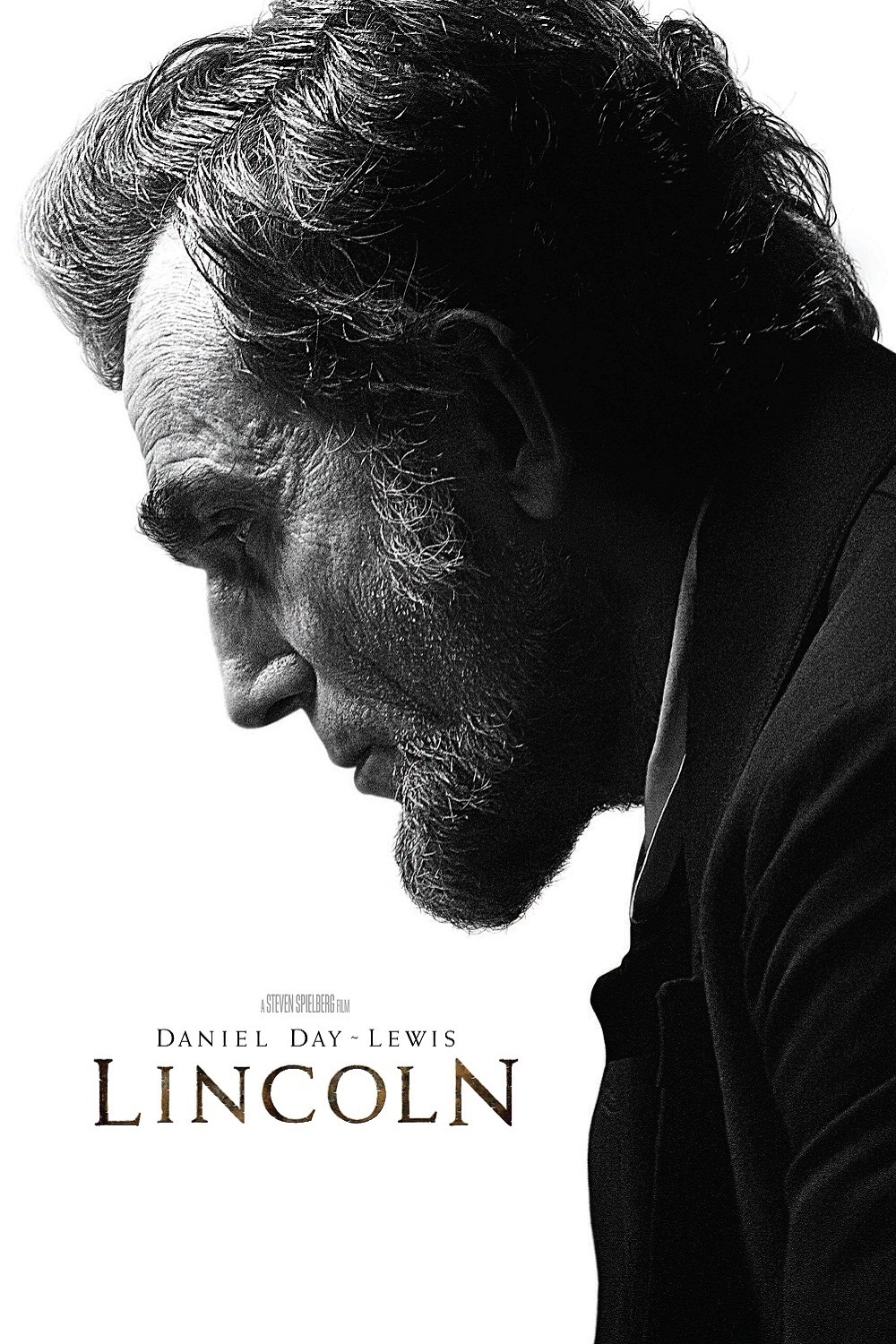

I've rarely been more aware than during Steven Spielberg's "Lincoln" that Abraham Lincoln was a plain-spoken, practical, down-to-earth man from the farmlands of Kentucky, Indiana and Illinois. He had less than a year of formal education and taught himself through his hungry reading of great books. I still recall from a childhood book the image of him taking a piece of charcoal and working out mathematics by writing on the back of a shovel.

Lincoln lacked social polish but he had great intelligence and knowledge of human nature. The hallmark of the man, performed so powerfully by Daniel Day-Lewis in "Lincoln," is calm self-confidence, patience and a willingness to play politics in a realistic way. The film focuses on the final months of Lincoln's life, including the passage of the 13th Amendment ending slavery, the surrender of the Confederacy and his assassination. Rarely has a film attended more carefully to the details of politics.

Lincoln believed slavery was immoral, but he also considered the 13th Amendment a masterstroke in cutting away the financial foundations of the Confederacy. In the film, the passage of the amendment is guided by William Seward ( David Strathairn ), his secretary of state, and by Rep. Thaddeus Stevens ( Tommy Lee Jones ), the most powerful abolitionist in the House. Neither these nor any other performances in the film depend on self-conscious histrionics; Jones in particular portrays a crafty codger with some secret hiding places in his heart.

The capital city of Washington is portrayed here as roughshod gathering of politicians on the make. The images by Janusz Kaminski , Spielberg's frequent cinematographer, use earth tones and muted indoor lighting. The White House is less a temple of state than a gathering place for wheelers and dealers. This ambience reflects the descriptions in Gore Vidal's historical novel "Lincoln," although the political and personal details in Tony Kushner's concise, revealing dialogue is based on "Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln" by Doris Kearns Goodwin. The book is well-titled. This is a film not about an icon of history, but about a president who was scorned by some of his political opponents as just a hayseed from the backwoods.

Lincoln is not above political vote buying. He offers jobs, promotions, titles and pork barrel spending. He isn't even slightly reluctant to employ the low-handed tactics of his chief negotiators (Tim Blake Nelson , James Spader , John Hawkes ). That's how the game is played, and indeed we may be reminded of the arm-bending used to pass the civil rights legislation by Lyndon B. Johnson, the subject of another biography by Goodwin.

Daniel Day-Lewis, who has a lock on an Oscar nomination, modulates Lincoln. He is soft-spoken, a little hunched, exhausted after the years of war, concerned that no more troops die. He communicates through stories and parables. At his side is his wife, Mary Todd Lincoln ( Sally Field , typically sturdy and spunky), who is sometimes seen as a social climber but here is focused as wife and mother. She has already lost one son in the war and fears to lose the other. This boy, Robert Todd Lincoln ( Joseph Gordon-Levitt ), refuses the privileges of family.

There are some battlefields in "Lincoln" but the only battle scene is at the opening, when the words of the Gettysburg Address are spoken with the greatest possible impact, and not by Lincoln. Kushner also smoothly weaves the wording of the 13th Amendment into the film without making it sound like an obligatory history lesson.

The film ends soon after Lincoln's assassination. I suppose audiences will expect that to be included. There is an earlier shot, when it could have ended, of President Lincoln walking away from the camera after his amendment has been passed. The rest belongs to history.

Roger Ebert

Roger Ebert was the film critic of the Chicago Sun-Times from 1967 until his death in 2013. In 1975, he won the Pulitzer Prize for distinguished criticism.

- Daniel Day-Lewis as Lincoln

- Tommy Lee Jones as Stevens

- Sally Field as Mary Todd

- David Strathairn as Seward

Directed by

- Steven Spielberg

- Tony Kushner

Leave a comment

Now playing.

Dear Santa (2024)

The Last Republican

Gladiator II

Bread & Roses

Ernest Cole: Lost and Found

The Black Sea

Never Look Away

Latest articles.

Miyazaki, Howl, and Matters of the Heart

Sharp, Propulsive “The Agency” Should Appeal to Fans of Spy Fiction

Solid Acting Saves the Familiar Premise of "Get Millie Black"

A Sense of Freedom: Filmmaker and Teacher Bart Weiss Talks About his Book "Smartphone Cinema"

The best movie reviews, in your inbox.

- Bulletin Board

- Document Lab

- Field Trips

- Media Center

- Teacher’s Desk

- Report Card

The Unofficial Teacher’s Guide to Spielberg’s Lincoln

General Background

Cast of Characters (with comparison images of real figures and actors)

Scene-by-scene summary (with access to Tony Kushner’s script)

Historians React to the “Lincoln” Movie

Warning: Artists at Work (extensive analysis of artistic license in the “Lincoln” movie)

Teaching the “Lincoln” Movie

Lincoln and War Powers (lesson plan aligned with Common Core)

Related Research Tools

The Basic Lincoln (records from House Divided research engine)

The Total Lincoln (Lincoln’s Collected Works, Papers, and Day-By-Day –all in one place)

Lincoln-Douglas Debates Digital Classroom (includes clickable word cloud of the debates)

Interactive Excerpts from Michael Burlingame’s Abraham Lincoln: A Life (2008)

Matthew Pinsker challenges the “Myth” of Rivals (Journal Divided)

Why is Feb. 1st “National Freedom Day”? (Blog Divided)

- Search for:

Credits & Contacts

Producer: Matthew Pinsker House Divided Project PO Box 1773 / Dickinson College Carlisle, PA 17013 [email protected]

Featured E-Book:

Forgotten Abolitionist: John A.J. Creswell of Maryland

Review Of The Movie 'Lincoln' By Steven Spielberg

- Category: Entertainment

- Topic: Film Analysis , Movie Review

Pages: 2 (964 words)

Views: 2390

- Downloads: -->

--> ⚠️ Remember: This essay was written and uploaded by an--> click here.

Found a great essay sample but want a unique one?

are ready to help you with your essay

You won’t be charged yet!

Bridge Essays

Fast Fashion Essays

Monster Essays

Movie Review Essays

12 Angry Men Essays

Related Essays

We are glad that you like it, but you cannot copy from our website. Just insert your email and this sample will be sent to you.

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Your essay sample has been sent.

In fact, there is a way to get an original essay! Turn to our writers and order a plagiarism-free paper.

samplius.com uses cookies to offer you the best service possible.By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .--> -->