Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- How to Write an Abstract | Steps & Examples

How to Write an Abstract | Steps & Examples

Published on February 28, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on July 18, 2023 by Eoghan Ryan.

An abstract is a short summary of a longer work (such as a thesis , dissertation or research paper ). The abstract concisely reports the aims and outcomes of your research, so that readers know exactly what your paper is about.

Although the structure may vary slightly depending on your discipline, your abstract should describe the purpose of your work, the methods you’ve used, and the conclusions you’ve drawn.

One common way to structure your abstract is to use the IMRaD structure. This stands for:

- Introduction

Abstracts are usually around 100–300 words, but there’s often a strict word limit, so make sure to check the relevant requirements.

In a dissertation or thesis , include the abstract on a separate page, after the title page and acknowledgements but before the table of contents .

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Abstract example, when to write an abstract, step 1: introduction, step 2: methods, step 3: results, step 4: discussion, tips for writing an abstract, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about abstracts.

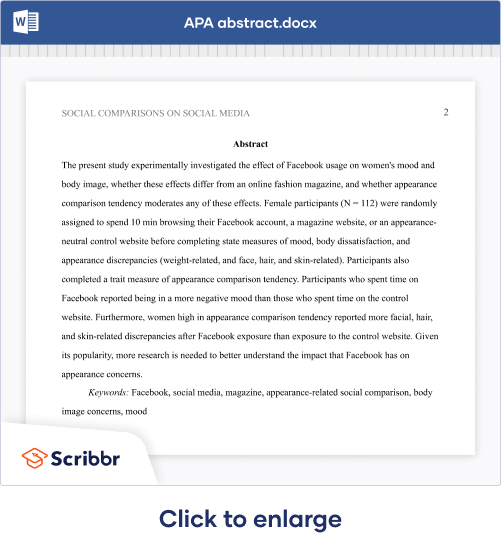

Hover over the different parts of the abstract to see how it is constructed.

This paper examines the role of silent movies as a mode of shared experience in the US during the early twentieth century. At this time, high immigration rates resulted in a significant percentage of non-English-speaking citizens. These immigrants faced numerous economic and social obstacles, including exclusion from public entertainment and modes of discourse (newspapers, theater, radio).

Incorporating evidence from reviews, personal correspondence, and diaries, this study demonstrates that silent films were an affordable and inclusive source of entertainment. It argues for the accessible economic and representational nature of early cinema. These concerns are particularly evident in the low price of admission and in the democratic nature of the actors’ exaggerated gestures, which allowed the plots and action to be easily grasped by a diverse audience despite language barriers.

Keywords: silent movies, immigration, public discourse, entertainment, early cinema, language barriers.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

You will almost always have to include an abstract when:

- Completing a thesis or dissertation

- Submitting a research paper to an academic journal

- Writing a book or research proposal

- Applying for research grants

It’s easiest to write your abstract last, right before the proofreading stage, because it’s a summary of the work you’ve already done. Your abstract should:

- Be a self-contained text, not an excerpt from your paper

- Be fully understandable on its own

- Reflect the structure of your larger work

Start by clearly defining the purpose of your research. What practical or theoretical problem does the research respond to, or what research question did you aim to answer?

You can include some brief context on the social or academic relevance of your dissertation topic , but don’t go into detailed background information. If your abstract uses specialized terms that would be unfamiliar to the average academic reader or that have various different meanings, give a concise definition.

After identifying the problem, state the objective of your research. Use verbs like “investigate,” “test,” “analyze,” or “evaluate” to describe exactly what you set out to do.

This part of the abstract can be written in the present or past simple tense but should never refer to the future, as the research is already complete.

- This study will investigate the relationship between coffee consumption and productivity.

- This study investigates the relationship between coffee consumption and productivity.

Next, indicate the research methods that you used to answer your question. This part should be a straightforward description of what you did in one or two sentences. It is usually written in the past simple tense, as it refers to completed actions.

- Structured interviews will be conducted with 25 participants.

- Structured interviews were conducted with 25 participants.

Don’t evaluate validity or obstacles here — the goal is not to give an account of the methodology’s strengths and weaknesses, but to give the reader a quick insight into the overall approach and procedures you used.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Next, summarize the main research results . This part of the abstract can be in the present or past simple tense.

- Our analysis has shown a strong correlation between coffee consumption and productivity.

- Our analysis shows a strong correlation between coffee consumption and productivity.

- Our analysis showed a strong correlation between coffee consumption and productivity.

Depending on how long and complex your research is, you may not be able to include all results here. Try to highlight only the most important findings that will allow the reader to understand your conclusions.

Finally, you should discuss the main conclusions of your research : what is your answer to the problem or question? The reader should finish with a clear understanding of the central point that your research has proved or argued. Conclusions are usually written in the present simple tense.

- We concluded that coffee consumption increases productivity.

- We conclude that coffee consumption increases productivity.

If there are important limitations to your research (for example, related to your sample size or methods), you should mention them briefly in the abstract. This allows the reader to accurately assess the credibility and generalizability of your research.

If your aim was to solve a practical problem, your discussion might include recommendations for implementation. If relevant, you can briefly make suggestions for further research.

If your paper will be published, you might have to add a list of keywords at the end of the abstract. These keywords should reference the most important elements of the research to help potential readers find your paper during their own literature searches.

Be aware that some publication manuals, such as APA Style , have specific formatting requirements for these keywords.

It can be a real challenge to condense your whole work into just a couple of hundred words, but the abstract will be the first (and sometimes only) part that people read, so it’s important to get it right. These strategies can help you get started.

Read other abstracts

The best way to learn the conventions of writing an abstract in your discipline is to read other people’s. You probably already read lots of journal article abstracts while conducting your literature review —try using them as a framework for structure and style.

You can also find lots of dissertation abstract examples in thesis and dissertation databases .

Reverse outline

Not all abstracts will contain precisely the same elements. For longer works, you can write your abstract through a process of reverse outlining.

For each chapter or section, list keywords and draft one to two sentences that summarize the central point or argument. This will give you a framework of your abstract’s structure. Next, revise the sentences to make connections and show how the argument develops.

Write clearly and concisely

A good abstract is short but impactful, so make sure every word counts. Each sentence should clearly communicate one main point.

To keep your abstract or summary short and clear:

- Avoid passive sentences: Passive constructions are often unnecessarily long. You can easily make them shorter and clearer by using the active voice.

- Avoid long sentences: Substitute longer expressions for concise expressions or single words (e.g., “In order to” for “To”).

- Avoid obscure jargon: The abstract should be understandable to readers who are not familiar with your topic.

- Avoid repetition and filler words: Replace nouns with pronouns when possible and eliminate unnecessary words.

- Avoid detailed descriptions: An abstract is not expected to provide detailed definitions, background information, or discussions of other scholars’ work. Instead, include this information in the body of your thesis or paper.

If you’re struggling to edit down to the required length, you can get help from expert editors with Scribbr’s professional proofreading services or use the paraphrasing tool .

Check your formatting

If you are writing a thesis or dissertation or submitting to a journal, there are often specific formatting requirements for the abstract—make sure to check the guidelines and format your work correctly. For APA research papers you can follow the APA abstract format .

Checklist: Abstract

The word count is within the required length, or a maximum of one page.

The abstract appears after the title page and acknowledgements and before the table of contents .

I have clearly stated my research problem and objectives.

I have briefly described my methodology .

I have summarized the most important results .

I have stated my main conclusions .

I have mentioned any important limitations and recommendations.

The abstract can be understood by someone without prior knowledge of the topic.

You've written a great abstract! Use the other checklists to continue improving your thesis or dissertation.

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or research bias, make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

Research bias

- Anchoring bias

- Halo effect

- The Baader–Meinhof phenomenon

- The placebo effect

- Nonresponse bias

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

An abstract is a concise summary of an academic text (such as a journal article or dissertation ). It serves two main purposes:

- To help potential readers determine the relevance of your paper for their own research.

- To communicate your key findings to those who don’t have time to read the whole paper.

Abstracts are often indexed along with keywords on academic databases, so they make your work more easily findable. Since the abstract is the first thing any reader sees, it’s important that it clearly and accurately summarizes the contents of your paper.

An abstract for a thesis or dissertation is usually around 200–300 words. There’s often a strict word limit, so make sure to check your university’s requirements.

The abstract is the very last thing you write. You should only write it after your research is complete, so that you can accurately summarize the entirety of your thesis , dissertation or research paper .

Avoid citing sources in your abstract . There are two reasons for this:

- The abstract should focus on your original research, not on the work of others.

- The abstract should be self-contained and fully understandable without reference to other sources.

There are some circumstances where you might need to mention other sources in an abstract: for example, if your research responds directly to another study or focuses on the work of a single theorist. In general, though, don’t include citations unless absolutely necessary.

The abstract appears on its own page in the thesis or dissertation , after the title page and acknowledgements but before the table of contents .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, July 18). How to Write an Abstract | Steps & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 4, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/abstract/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a thesis or dissertation introduction, shorten your abstract or summary, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Research Voyage

Research Tips and Infromation

How to Write Effective Research Grant Proposal Abstract?

Introduction

Research methodology and approach, key findings or results, significance and potential impact of the proposed research, title: developing a deep learning model for computer vision-based gesture recognition, phrasal verbs that can be used to write an effective research grant proposal, how long should a research grant proposal abstract be.

- "Significance and potential impact" Section of a Research Grant Proposal Abstract?

Common Mistakes to Avoid when Writing a Research Grant Proposal Abstract

How can i make my research grant proposal abstract stand out, tailoring your research grant proposal abstract for a specific funding agency, difference between a research grant proposal abstract and a research paper abstract, feedback on my research grant proposal abstract.

A research grant proposal abstract is a brief summary of a research proposal that provides an overview of the proposed project’s objectives, methods, results, and potential impact. It is often the first part of the proposal that reviewers will read and serves as a key factor in determining whether a grant proposal is accepted or rejected.

Writing a clear and concise abstract is important because it helps reviewers quickly and easily understand the proposed research project’s main objectives, approach, and potential impact. A well-written abstract can also help to catch the attention of reviewers and encourage them to read the full proposal, increasing the chances of funding success.

Components of a Research Grant Proposal Abstract

The research question or problem should be clearly and succinctly stated in the abstract, providing the reader with a clear understanding of the scope and purpose of the proposed research. This description should highlight the novelty, importance, or relevance of the research question.

For example: “This research proposal aims to investigate the relationship between physical activity and mental health outcomes in adolescents with a focus on exploring the role of community-based interventions.”

The abstract should provide a brief description of the research methodology and approach, highlighting the key elements of the proposed research design. This section should provide enough information to help the reader understand the proposed research methodology and approach.

For example: “The proposed study will utilize a mixed-methods approach, consisting of a randomized controlled trial and qualitative interviews to explore the impact of a community-based physical activity program on mental health outcomes in adolescents.”

If the research proposal involves a pilot study or preliminary data, the abstract may summarize the key findings or results. This summary should be brief and provide an overview of the expected outcomes or results of the proposed research.

For example: “Preliminary data from a small pilot study suggests that community-based physical activity interventions may be effective in improving mental health outcomes in adolescents. The proposed study aims to build upon these findings to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the impact of such interventions.”

The abstract should conclude with a brief explanation of the significance and potential impact of the proposed research. This section should highlight the potential contributions of the proposed research to the research field and its broader implications for society.

For example: “This research has the potential to inform the development of community-based physical activity interventions for adolescents, with implications for improving mental health outcomes and reducing healthcare costs. Additionally, this study may inform policies related to physical activity and mental health in adolescents.”

Tips for Writing an Effective Research Grant Proposal Abstract

Keep the abstract clear, concise, and specific: The abstract should be written in a clear and concise manner, avoiding unnecessary detail or repetition. The language should be specific and focused on the key elements of the proposed research.

Use plain language and avoid technical jargon: The abstract should be written in plain language, avoiding complex technical terminology that may be difficult for readers outside of the field to understand. Technical terms should be defined and explained in simple language.

Focus on the most important aspects of the research proposal : The abstract should focus on the most important elements of the proposed research project, including the research question or problem, methodology, and potential impact. Other details that are not essential to the understanding of the proposed research can be left out of the abstract.

Highlight the unique contributions of the proposed research : The abstract should emphasize the unique contributions of the proposed research, highlighting what sets it apart from other research projects in the field. This can include innovative methodologies, novel research questions, or the potential to fill gaps in the existing research.

Emphasize the potential benefits to society or the research field: The abstract should emphasize the potential benefits of the proposed research to society or the research field, including its potential impact on public health, policy, or clinical practice. This can help to make the research proposal more compelling to funders.

Be sure to follow any specific guidelines or requirements for the grant proposal abstract: The abstract should be written in accordance with any specific guidelines or requirements provided by the funding agency or organization. Failure to follow these guidelines may result in rejection of the proposal.

Example of a Research Grant Proposal Abstract

Introduction: This research grant proposal abstract outlines a project to develop a deep learning model for computer vision-based gesture recognition. The proposed research addresses the growing need for more accurate and reliable gesture recognition technologies for applications in human-computer interaction, virtual reality, and robotics.

Components of a research grant proposal abstract : This research proposal will involve developing and evaluating a deep learning model that can accurately recognize and interpret hand gestures captured by a camera. The research methodology will involve collecting and analyzing data on hand gestures, training and testing the deep learning model using various algorithms and evaluating the model’s accuracy and efficiency. The key findings of the proposed research will be a deep learning model that can accurately recognize hand gestures and an understanding of the key features that are most important in training such a model. The significance and potential impact of the proposed research include improving the accuracy and reliability of gesture recognition technologies, enabling more efficient and natural human-computer interaction, and advancing the fields of virtual reality and robotics.

Here are some examples of phrasal verbs that can be used to write an effective research grant proposal abstract:

Note that these are just a few examples and there are many other phrasal verbs that can be used to effectively convey the purpose and goals of a research grant proposal.

The length of a research grant proposal abstract can vary depending on the specific guidelines provided by the funding agency or grant opportunity. In general, most research grant proposal abstracts should be around 250 to 300 words or less.

However, it’s important to follow the specific instructions provided by the funding agency, which may specify a different word limit or even a specific format or structure for the abstract. It’s important to make sure that the abstract is clear, concise, and includes all the necessary information to give a clear overview of the proposed research project.

“Significance and potential impact” Section of a Research Grant Proposal Abstract?

The “significance and potential impact” section of a research grant proposal abstract should describe why the proposed research project is important and what potential benefits it could have for society or the research field. This section should convince the funding agency that the proposed research is worth funding.

Some key points that can be included in this section are:

- The significance of the research question or problem being addressed, including any gaps in existing knowledge or areas where further research is needed.

- The potential impact of the proposed research, both in terms of advancing scientific understanding and in terms of practical applications or benefits to society.

- Any potential risks or challenges associated with the research project, and how these will be addressed.

- The broader implications of the proposed research for the research field or related fields, including any potential for future research or applications.

Overall, this section should demonstrate the importance and potential impact of the proposed research project, and why it is a worthwhile investment for the funding agency.

Here are some common mistakes to avoid when writing a research grant proposal abstract:

- Failing to follow the guidelines: It’s important to carefully read and follow the guidelines and requirements provided by the funding agency or grant opportunity. Failure to do so may result in the abstract being rejected without review.

- Being too technical or jargon-heavy: It’s important to use plain language and avoid technical jargon or acronyms that may not be familiar to a broader audience.

- Including unnecessary details: The abstract should focus on the most important aspects of the proposed research project and avoid including extraneous details or background information.

- Making unsupported claims: Any claims or assertions made in the abstract should be supported by evidence or data from the proposed research project.

- Failing to clearly articulate the significance and potential impact of the research: The abstract should clearly and convincingly explain why the proposed research project is important and what potential benefits it could have for society or the research field.

- Being too vague or general: The abstract should provide enough detail to give a clear overview of the proposed research project, without being overly vague or general.

- Being too long or too short: The abstract should be within the specified word limit and provide enough detail to clearly and effectively communicate the proposed research project.

Here are some tips to make your research grant proposal abstract stand out:

- Focus on the uniqueness of your research: Highlight the unique contributions and potential impact of your research project, and explain why it is different from existing research in the field.

- Emphasize the potential benefits: Clearly articulate the potential benefits of the proposed research, both in terms of advancing scientific understanding and in terms of practical applications or benefits to society.

- Use clear and concise language: Use plain language and avoid technical jargon, acronyms or overly complex language that may not be familiar to a broader audience.

- Provide sufficient detail: Provide enough detail to give a clear overview of the proposed research project, without being overly vague or general.

- Follow the guidelines and requirements: Carefully read and follow the guidelines and requirements provided by the funding agency or grant opportunity.

- Include preliminary results: If you have any preliminary data or results, include them in the abstract to demonstrate the feasibility and potential impact of the proposed research project.

- Be persuasive: Use persuasive language and a clear structure to convince the funding agency or grant opportunity that your proposed research project is worth funding.

Overall, making your research grant proposal abstract stand out involves effectively communicating the significance and potential impact of your proposed research project, and demonstrating why it is a worthwhile investment for the funding agency or grant opportunity.

When tailoring your research grant proposal abstract for a specific funding agency or grant opportunity, consider the following tips:

- Read and follow the guidelines: Carefully read and follow the guidelines and requirements provided by the funding agency or grant opportunity. Ensure that your abstract adheres to the specific formatting, length, and content requirements specified in the guidelines.

- Highlight alignment with funding priorities: Consider the specific priorities and focus areas of the funding agency or grant opportunity, and tailor your abstract to demonstrate how your proposed research aligns with those priorities.

- Use appropriate language: Use language that is appropriate for the specific funding agency or grant opportunity. For example, if the funding agency is focused on advancing practical applications, emphasize the practical implications and potential benefits of your proposed research.

- Provide evidence of fit: Provide evidence that your proposed research project is a good fit for the funding agency or grant opportunity. This might include highlighting relevant experience or expertise, or demonstrating how your proposed research addresses a particular gap in knowledge or addresses an important research question.

- Be clear and concise: Ensure that your abstract is clear and concise, using plain language and avoiding technical jargon or overly complex language.

- Consider the review process: Consider the review process for the funding agency or grant opportunity, and tailor your abstract to address the specific criteria or evaluation criteria that will be used to evaluate proposals.

Overall, tailoring your research grant proposal abstract for a specific funding agency or grant opportunity involves carefully reviewing the guidelines and priorities of the funding agency or grant opportunity, and highlighting how your proposed research aligns with those priorities while adhering to the specific requirements and evaluation criteria specified by the funding agency or grant opportunity.

A research grant proposal abstract and a research paper abstract serve different purposes and have different audiences.

A research grant proposal abstract is a brief summary of a proposed research project that is typically submitted as part of a grant application to funding agencies. The abstract is used to provide a quick overview of the proposed research project and to convince the funding agency to provide financial support for the research. The abstract is typically focused on the research question, methodology, key findings or results, and the significance and potential impact of the proposed research. The abstract is often written with a broader audience in mind, as it may be reviewed by multiple individuals who are not experts in the specific research area.

A research paper abstract , on the other hand, is a brief summary of a completed research paper that is included at the beginning of the paper. The abstract is used to provide readers with a quick overview of the research paper and to help readers decide whether they want to read the full paper. The abstract is typically focused on the research question, methodology, key findings or results, and the implications of the research. The abstract is typically written for an audience of experts in the specific research area who have a deeper understanding of the topic.

In summary, the main differences between a research grant proposal abstract and a research paper abstract are the purpose, audience, and content. While both provide a summary of a research project, the research grant proposal abstract is focused on obtaining funding, while the research paper abstract is focused on providing an overview of the completed research paper.

Here’s a table summarizing the main differences between a research grant proposal abstract and a research paper abstract, with examples from computer science:

There are several ways to get feedback on your research grant proposal abstract before submitting it:

- Ask colleagues or mentors in your field: You can ask colleagues or mentors in your field to review your abstract and provide feedback on its clarity, organization, and overall effectiveness.

- Attend a grant writing workshop or seminar: Many universities and research institutions offer grant writing workshops or seminars that provide guidance on how to write effective grant proposals. These events often include opportunities for participants to receive feedback on their proposals.

- Consult with a grant writing consultant: If you have the budget for it, you can hire a grant writing consultant to review your proposal and provide feedback. These consultants are experienced in writing successful grant proposals and can offer valuable insights into how to improve your proposal. Read my article on hiring research consultant for research-related works.

- Use online resources: There are many online resources available that provide guidance on how to write effective grant proposals, including tips for writing an effective abstract. You can also use online platforms, such as LinkedIn or Twitter, to connect with experts in your field and seek feedback on your proposal.

Regardless of the method you choose, it is important to get feedback from multiple sources to ensure that your proposal is as strong as possible before submitting it.

Writing a clear and compelling research grant proposal abstract is essential for securing funding in the competitive field of computer science research. By defining the purpose of the abstract and highlighting its key components, we have provided a framework for crafting a successful proposal.

By following our tips for writing an effective abstract and avoiding common mistakes, you can increase your chances of securing funding for your research project. Whether you are an experienced researcher or just starting out in your career, we hope that the information and examples provided here will help you to write an abstract that will grab the attention of grant reviewers and make a compelling case for your research proposal.

Upcoming Events

- Visit the Upcoming International Conferences at Exotic Travel Destinations with Travel Plan

- Visit for Research Internships Worldwide

Recent Posts

- How to Put Research Grants on Your CV ?

- How to Request for Journal Publishing Charge (APC) Discount or Waiver?

- Do Review Papers Count for the Award of a PhD Degree?

- Vinay Kabadi, University of Melbourne, Interview on Award-Winning Research

- Do You Need Publications for a PhD Application? The Essential Guide for Applicants

- All Blog Posts

- Research Career

- Research Conference

- Research Internship

- Research Journal

- Research Tools

- Uncategorized

- Research Conferences

- Research Journals

- Research Grants

- Internships

- Research Internships

- Email Templates

- Conferences

- Blog Partners

- Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2024 Research Voyage

Design by ThemesDNA.com

Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper

Definition and Purpose of Abstracts

An abstract is a short summary of your (published or unpublished) research paper, usually about a paragraph (c. 6-7 sentences, 150-250 words) long. A well-written abstract serves multiple purposes:

- an abstract lets readers get the gist or essence of your paper or article quickly, in order to decide whether to read the full paper;

- an abstract prepares readers to follow the detailed information, analyses, and arguments in your full paper;

- and, later, an abstract helps readers remember key points from your paper.

It’s also worth remembering that search engines and bibliographic databases use abstracts, as well as the title, to identify key terms for indexing your published paper. So what you include in your abstract and in your title are crucial for helping other researchers find your paper or article.

If you are writing an abstract for a course paper, your professor may give you specific guidelines for what to include and how to organize your abstract. Similarly, academic journals often have specific requirements for abstracts. So in addition to following the advice on this page, you should be sure to look for and follow any guidelines from the course or journal you’re writing for.

The Contents of an Abstract

Abstracts contain most of the following kinds of information in brief form. The body of your paper will, of course, develop and explain these ideas much more fully. As you will see in the samples below, the proportion of your abstract that you devote to each kind of information—and the sequence of that information—will vary, depending on the nature and genre of the paper that you are summarizing in your abstract. And in some cases, some of this information is implied, rather than stated explicitly. The Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , which is widely used in the social sciences, gives specific guidelines for what to include in the abstract for different kinds of papers—for empirical studies, literature reviews or meta-analyses, theoretical papers, methodological papers, and case studies.

Here are the typical kinds of information found in most abstracts:

- the context or background information for your research; the general topic under study; the specific topic of your research

- the central questions or statement of the problem your research addresses

- what’s already known about this question, what previous research has done or shown

- the main reason(s) , the exigency, the rationale , the goals for your research—Why is it important to address these questions? Are you, for example, examining a new topic? Why is that topic worth examining? Are you filling a gap in previous research? Applying new methods to take a fresh look at existing ideas or data? Resolving a dispute within the literature in your field? . . .

- your research and/or analytical methods

- your main findings , results , or arguments

- the significance or implications of your findings or arguments.

Your abstract should be intelligible on its own, without a reader’s having to read your entire paper. And in an abstract, you usually do not cite references—most of your abstract will describe what you have studied in your research and what you have found and what you argue in your paper. In the body of your paper, you will cite the specific literature that informs your research.

When to Write Your Abstract

Although you might be tempted to write your abstract first because it will appear as the very first part of your paper, it’s a good idea to wait to write your abstract until after you’ve drafted your full paper, so that you know what you’re summarizing.

What follows are some sample abstracts in published papers or articles, all written by faculty at UW-Madison who come from a variety of disciplines. We have annotated these samples to help you see the work that these authors are doing within their abstracts.

Choosing Verb Tenses within Your Abstract

The social science sample (Sample 1) below uses the present tense to describe general facts and interpretations that have been and are currently true, including the prevailing explanation for the social phenomenon under study. That abstract also uses the present tense to describe the methods, the findings, the arguments, and the implications of the findings from their new research study. The authors use the past tense to describe previous research.

The humanities sample (Sample 2) below uses the past tense to describe completed events in the past (the texts created in the pulp fiction industry in the 1970s and 80s) and uses the present tense to describe what is happening in those texts, to explain the significance or meaning of those texts, and to describe the arguments presented in the article.

The science samples (Samples 3 and 4) below use the past tense to describe what previous research studies have done and the research the authors have conducted, the methods they have followed, and what they have found. In their rationale or justification for their research (what remains to be done), they use the present tense. They also use the present tense to introduce their study (in Sample 3, “Here we report . . .”) and to explain the significance of their study (In Sample 3, This reprogramming . . . “provides a scalable cell source for. . .”).

Sample Abstract 1

From the social sciences.

Reporting new findings about the reasons for increasing economic homogamy among spouses

Gonalons-Pons, Pilar, and Christine R. Schwartz. “Trends in Economic Homogamy: Changes in Assortative Mating or the Division of Labor in Marriage?” Demography , vol. 54, no. 3, 2017, pp. 985-1005.

![how to write an abstract for a research grant “The growing economic resemblance of spouses has contributed to rising inequality by increasing the number of couples in which there are two high- or two low-earning partners. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence introduces the topic under study (the “economic resemblance of spouses”). This sentence also implies the question underlying this research study: what are the various causes—and the interrelationships among them—for this trend?] The dominant explanation for this trend is increased assortative mating. Previous research has primarily relied on cross-sectional data and thus has been unable to disentangle changes in assortative mating from changes in the division of spouses’ paid labor—a potentially key mechanism given the dramatic rise in wives’ labor supply. [Annotation for the previous two sentences: These next two sentences explain what previous research has demonstrated. By pointing out the limitations in the methods that were used in previous studies, they also provide a rationale for new research.] We use data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) to decompose the increase in the correlation between spouses’ earnings and its contribution to inequality between 1970 and 2013 into parts due to (a) changes in assortative mating, and (b) changes in the division of paid labor. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The data, research and analytical methods used in this new study.] Contrary to what has often been assumed, the rise of economic homogamy and its contribution to inequality is largely attributable to changes in the division of paid labor rather than changes in sorting on earnings or earnings potential. Our findings indicate that the rise of economic homogamy cannot be explained by hypotheses centered on meeting and matching opportunities, and they show where in this process inequality is generated and where it is not.” (p. 985) [Annotation for the previous two sentences: The major findings from and implications and significance of this study.]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-1.png)

Sample Abstract 2

From the humanities.

Analyzing underground pulp fiction publications in Tanzania, this article makes an argument about the cultural significance of those publications

Emily Callaci. “Street Textuality: Socialism, Masculinity, and Urban Belonging in Tanzania’s Pulp Fiction Publishing Industry, 1975-1985.” Comparative Studies in Society and History , vol. 59, no. 1, 2017, pp. 183-210.

![how to write an abstract for a research grant “From the mid-1970s through the mid-1980s, a network of young urban migrant men created an underground pulp fiction publishing industry in the city of Dar es Salaam. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence introduces the context for this research and announces the topic under study.] As texts that were produced in the underground economy of a city whose trajectory was increasingly charted outside of formalized planning and investment, these novellas reveal more than their narrative content alone. These texts were active components in the urban social worlds of the young men who produced them. They reveal a mode of urbanism otherwise obscured by narratives of decolonization, in which urban belonging was constituted less by national citizenship than by the construction of social networks, economic connections, and the crafting of reputations. This article argues that pulp fiction novellas of socialist era Dar es Salaam are artifacts of emergent forms of male sociability and mobility. In printing fictional stories about urban life on pilfered paper and ink, and distributing their texts through informal channels, these writers not only described urban communities, reputations, and networks, but also actually created them.” (p. 210) [Annotation for the previous sentences: The remaining sentences in this abstract interweave other essential information for an abstract for this article. The implied research questions: What do these texts mean? What is their historical and cultural significance, produced at this time, in this location, by these authors? The argument and the significance of this analysis in microcosm: these texts “reveal a mode or urbanism otherwise obscured . . .”; and “This article argues that pulp fiction novellas. . . .” This section also implies what previous historical research has obscured. And through the details in its argumentative claims, this section of the abstract implies the kinds of methods the author has used to interpret the novellas and the concepts under study (e.g., male sociability and mobility, urban communities, reputations, network. . . ).]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-2.png)

Sample Abstract/Summary 3

From the sciences.

Reporting a new method for reprogramming adult mouse fibroblasts into induced cardiac progenitor cells

Lalit, Pratik A., Max R. Salick, Daryl O. Nelson, Jayne M. Squirrell, Christina M. Shafer, Neel G. Patel, Imaan Saeed, Eric G. Schmuck, Yogananda S. Markandeya, Rachel Wong, Martin R. Lea, Kevin W. Eliceiri, Timothy A. Hacker, Wendy C. Crone, Michael Kyba, Daniel J. Garry, Ron Stewart, James A. Thomson, Karen M. Downs, Gary E. Lyons, and Timothy J. Kamp. “Lineage Reprogramming of Fibroblasts into Proliferative Induced Cardiac Progenitor Cells by Defined Factors.” Cell Stem Cell , vol. 18, 2016, pp. 354-367.

![how to write an abstract for a research grant “Several studies have reported reprogramming of fibroblasts into induced cardiomyocytes; however, reprogramming into proliferative induced cardiac progenitor cells (iCPCs) remains to be accomplished. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence announces the topic under study, summarizes what’s already known or been accomplished in previous research, and signals the rationale and goals are for the new research and the problem that the new research solves: How can researchers reprogram fibroblasts into iCPCs?] Here we report that a combination of 11 or 5 cardiac factors along with canonical Wnt and JAK/STAT signaling reprogrammed adult mouse cardiac, lung, and tail tip fibroblasts into iCPCs. The iCPCs were cardiac mesoderm-restricted progenitors that could be expanded extensively while maintaining multipo-tency to differentiate into cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells in vitro. Moreover, iCPCs injected into the cardiac crescent of mouse embryos differentiated into cardiomyocytes. iCPCs transplanted into the post-myocardial infarction mouse heart improved survival and differentiated into cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells. [Annotation for the previous four sentences: The methods the researchers developed to achieve their goal and a description of the results.] Lineage reprogramming of adult somatic cells into iCPCs provides a scalable cell source for drug discovery, disease modeling, and cardiac regenerative therapy.” (p. 354) [Annotation for the previous sentence: The significance or implications—for drug discovery, disease modeling, and therapy—of this reprogramming of adult somatic cells into iCPCs.]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-3.png)

Sample Abstract 4, a Structured Abstract

Reporting results about the effectiveness of antibiotic therapy in managing acute bacterial sinusitis, from a rigorously controlled study

Note: This journal requires authors to organize their abstract into four specific sections, with strict word limits. Because the headings for this structured abstract are self-explanatory, we have chosen not to add annotations to this sample abstract.

Wald, Ellen R., David Nash, and Jens Eickhoff. “Effectiveness of Amoxicillin/Clavulanate Potassium in the Treatment of Acute Bacterial Sinusitis in Children.” Pediatrics , vol. 124, no. 1, 2009, pp. 9-15.

“OBJECTIVE: The role of antibiotic therapy in managing acute bacterial sinusitis (ABS) in children is controversial. The purpose of this study was to determine the effectiveness of high-dose amoxicillin/potassium clavulanate in the treatment of children diagnosed with ABS.

METHODS : This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Children 1 to 10 years of age with a clinical presentation compatible with ABS were eligible for participation. Patients were stratified according to age (<6 or ≥6 years) and clinical severity and randomly assigned to receive either amoxicillin (90 mg/kg) with potassium clavulanate (6.4 mg/kg) or placebo. A symptom survey was performed on days 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 10, 20, and 30. Patients were examined on day 14. Children’s conditions were rated as cured, improved, or failed according to scoring rules.

RESULTS: Two thousand one hundred thirty-five children with respiratory complaints were screened for enrollment; 139 (6.5%) had ABS. Fifty-eight patients were enrolled, and 56 were randomly assigned. The mean age was 6630 months. Fifty (89%) patients presented with persistent symptoms, and 6 (11%) presented with nonpersistent symptoms. In 24 (43%) children, the illness was classified as mild, whereas in the remaining 32 (57%) children it was severe. Of the 28 children who received the antibiotic, 14 (50%) were cured, 4 (14%) were improved, 4(14%) experienced treatment failure, and 6 (21%) withdrew. Of the 28children who received placebo, 4 (14%) were cured, 5 (18%) improved, and 19 (68%) experienced treatment failure. Children receiving the antibiotic were more likely to be cured (50% vs 14%) and less likely to have treatment failure (14% vs 68%) than children receiving the placebo.

CONCLUSIONS : ABS is a common complication of viral upper respiratory infections. Amoxicillin/potassium clavulanate results in significantly more cures and fewer failures than placebo, according to parental report of time to resolution.” (9)

Some Excellent Advice about Writing Abstracts for Basic Science Research Papers, by Professor Adriano Aguzzi from the Institute of Neuropathology at the University of Zurich:

Academic and Professional Writing

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Analysis Papers

Reading Poetry

A Short Guide to Close Reading for Literary Analysis

Using Literary Quotations

Play Reviews

Writing a Rhetorical Précis to Analyze Nonfiction Texts

Incorporating Interview Data

Grant Proposals

Planning and Writing a Grant Proposal: The Basics

Additional Resources for Grants and Proposal Writing

Job Materials and Application Essays

Writing Personal Statements for Ph.D. Programs

- Before you begin: useful tips for writing your essay

- Guided brainstorming exercises

- Get more help with your essay

- Frequently Asked Questions

Resume Writing Tips

CV Writing Tips

Cover Letters

Business Letters

Proposals and Dissertations

Resources for Proposal Writers

Resources for Dissertators

Research Papers

Planning and Writing Research Papers

Quoting and Paraphrasing

Writing Annotated Bibliographies

Creating Poster Presentations

Thank-You Notes

Advice for Students Writing Thank-You Notes to Donors

Reading for a Review

Critical Reviews

Writing a Review of Literature

Scientific Reports

Scientific Report Format

Sample Lab Assignment

Writing for the Web

Writing an Effective Blog Post

Writing for Social Media: A Guide for Academics

PRDV009: Writing Grant Proposals

Writing a grant abstract.

Read this article, which describes the basic components commonly requested of a grant abstract.

Here, a non-profit consultant and expert grant writer shares some ideas for writing a grant abstract: An abstract is a short summary of your grant narrative, it gives the reader the big picture and should motivate them to want to learn more about your proposal. You'll be required to submit an abstract for most proposals, but it is rarely part of the scoring criteria. This does not minimize its importance, however, because it may be the first part of your application the reader sees. These are the basic components commonly requested in an abstract. Be sure to read the Request For Proposals (RFP) carefully to see if there is a specified outline for you to follow that may deviate from this list below:

- Statement of Purpose : Who is applying? What does this proposal do, who does it serve, where is it located? What is the proposed grant period?

- Goals and Objectives : List or summarize the goals and objectives that this proposal seeks to address.

- Management Plan : Summarize the key features that ensure your project will be professionally managed. Adequate budget, agency commitment, supervision, commitment of resources, etc.

- Evaluation : Describe the key features of your evaluation methods and plans which will ensure that the project is properly monitored and that outcomes will be accurately measured.

Remember that most abstracts are limited to a single page so you must be brief and to the point. I suggest that you write the abstract before you write your proposal so you have the whole proposal clearly in mind before you begin to write the detailed narrative.

Mastering Project Abstracts - The Ultimate Guide | Grantboost

When it comes to research, grant proposals, and academic writing, project abstracts play a crucial role in summarizing the key elements of a proposal or research paper. However, many nonprofit grant writers, students and researchers often struggle to understand their meaning and purpose. We’ll explore what project abstracts are, why they are important, and provide an example to give you an idea.

Project Abstract Meaning

- How Long Should a Project Abstract Be?

- Why Are Project Abstracts Important?

Elements of a Good Project Abstract

Proposal abstract example, using ai to generate project abstracts.

A project abstract is a brief summary of a research project or proposal that outlines the main objectives, methods, and expected outcomes. It is typically the first section of a research paper or grant proposal and is designed to give readers a clear idea of what the project is about without having to read the entire document. Merriam-Webster defines an abstract as something that summarizes or concentrates the essentials of a larger thing or several things .

How Long Should Project Abstracts Be?

The length of a project abstract can vary depending on the requirements of the specific project or proposal. They are meant to be persuasive, but it’s best practice for an abstract to be concise and to the point.

It’s important to keep in mind that grant reviewers often have a lot of proposals to read and evaluate, so brevity and clarity are key.

As a general guideline, a project abstract should be between 150-250 words or one page in length. This length should be sufficient to convey the essential information about the project and its significance, without overwhelming the reader with unnecessary details. Carefully review the guidelines of each grant application and tailor the length of the project abstract accordingly.

Why are Project Abstracts Important?

Project abstracts serve a variety of important functions in grant writing. Firstly, they help to ensure that the project and/or proposal is clearly defined and that the objectives and expected outcomes are communicated effectively. This is particularly important when applying for grants or funding, as the abstract is often the first thing that reviewers will read.

In addition, project abstracts provide readers with a quick overview of the research topic and can help them to determine whether the project is relevant to their own work or interests. This can be particularly useful for grant proposal reviewers who are conducting dozens of reviews and trying to identify potential collaborators.

Finally, project abstracts can be used to promote the project or proposal to a wider audience. For example, they can be used in conference programs or on websites to promote the project and attract potential collaborators or funders.

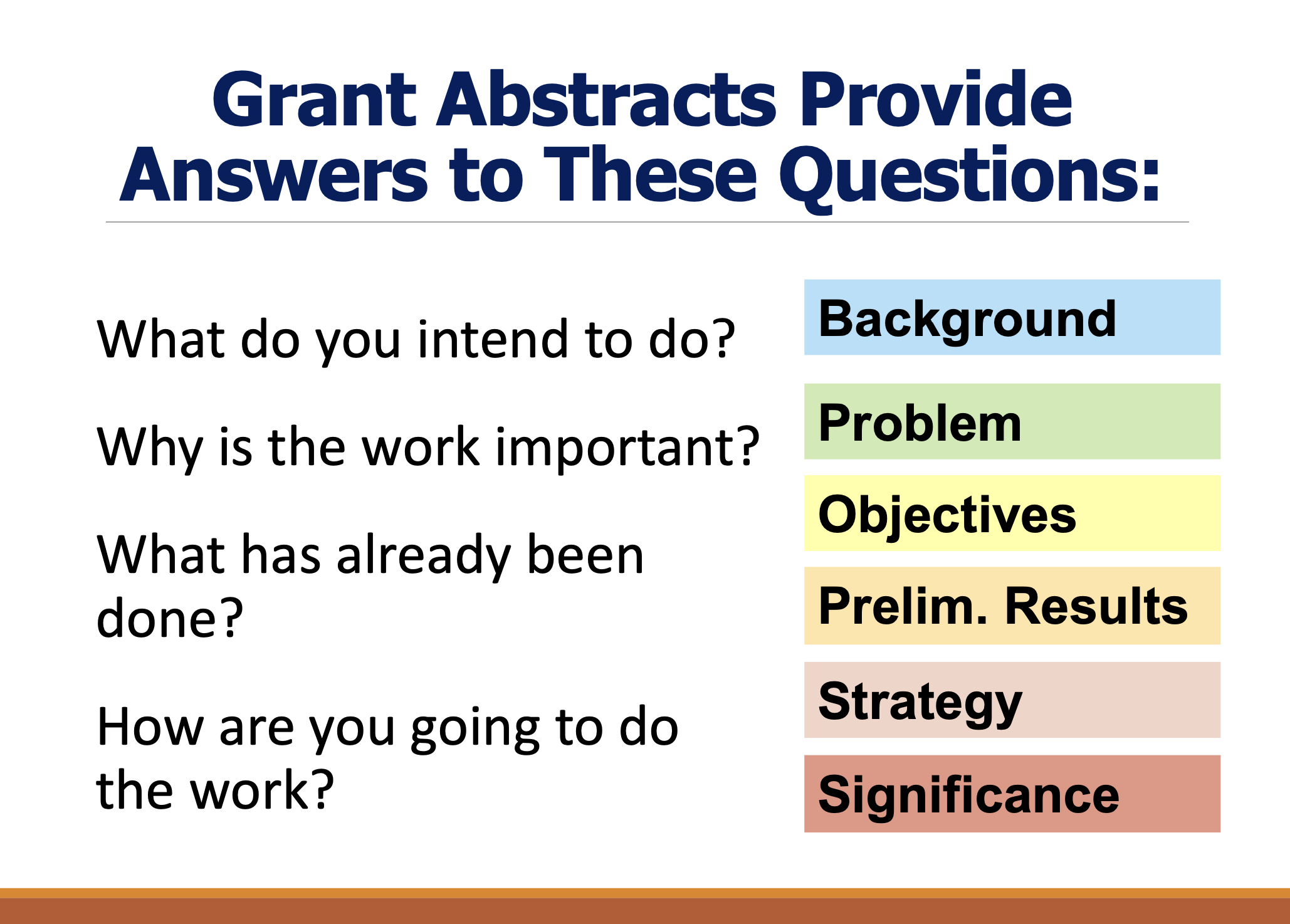

A good project abstract is essential to any successful grant application or research proposal. It is the first thing that reviewers or potential collaborators will read, and it plays a crucial role in determining whether or not they will continue to read on. To write a compelling project abstract, it is important to answer the core questions that reviewers will have about your project.

According to Yale’s Center for Teaching and Learning a good project abstract answers these 4 questions.

1. What do you intend to do? 2. Why is the work important? 3. What has already been done? 4. How are you going to do the work?

The first question that a project abstract should seek to answer is: what do you intend to do? This question relates to the overarching problem that your project seeks to address and the background context around it. It is important to clearly articulate the aims and objectives of your project in the abstract, and to do so in a way that is concise and easy to understand. Ideally, the aims and objectives should be framed in a way that highlights the novelty and impact of your project.

The second question that a project abstract should address is: why is the work important? This question relates to the broader context of your research, and should explain why your project is relevant and timely. It is important to demonstrate the potential impact of your research, and to show how it relates to current trends or challenges in your field. This can be achieved by providing a brief overview of the state of the art in your area of research, and by highlighting the potential implications of your work for both theoretical understanding and practical application.

The third question that a project abstract should answer is: what has already been done? This question relates to the background and context of your research, and should demonstrate that you have a good understanding of the existing literature and research in your field. It is important to show how your project builds upon existing work, and to highlight any gaps or limitations in the current understanding of the problem that your research aims to address. This can be achieved by providing a brief overview of the relevant literature and research, and by highlighting any key findings or insights that your project aims to contribute.

The final question that a project abstract should seek to answer is: how are you going to do the work? This question relates to the methodology and approach that you will use to carry out your research. It is important to provide a clear and concise overview of the methods and techniques that you will use to collect and analyze data, and to explain how these methods are appropriate for addressing the research question or problem that you have identified. It is also important to highlight any potential challenges or limitations in your methodology, and to explain how you plan to address these challenges.

In addition to answering these core questions, a good project abstract should also be well-written and well-structured. It should be concise and to-the-point, while still providing enough detail to give reviewers a clear understanding of your project. It should also be free of jargon or technical language that might be difficult for non-specialists to understand.

To help ensure that your project abstract is effective and compelling, it can be useful to seek feedback from colleagues or mentors in your field. They can provide valuable insights into the strengths and weaknesses of your abstract, and can help you to refine your message and improve your writing. By taking the time to craft a well-written and compelling project abstract, you can increase your chances of securing funding, attracting collaborators, and making a significant contribution to your field of research. If you’re a small nonprofit, reach out to our team for free feedbcack on your proposal.

To help illustrate the key elements of a project abstract, let’s look at an example of a research proposal abstract, courtesy of our friends at Yale:

Global warming is arguably one of the most pressing concerns of our time. However, we lack an effective model to predict precisely by how much the temperature will rise as a consequence of the increased levels of CO2 and other factors.

The width of this range is due to several uncertainties in different elements of the climate models, including the variability in the Sun’s rate of energy output.

To gain greater insight into the relationship between solar energy output and global temperature, we propose to launch the internationally led ABC satellite in April 2018.

Our aim is to collect for 2 years data on the solar diameter and shape, oscillations, and photospheric temperature variation. We will assess these data to model solar variability. Our findings will dramatically advance our understanding of solar activity and its climate effects.

Source: Yale’s Teaching and Learning Center

In recent years, advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) technology have revolutionized the way we approach proposal writing. AI-powered tools can help writers to automate repetitive tasks, generate ideas, and even write content from scratch. These “AI Grants” are powered by tools and companies that specialize in the writing process. One such tool is Grantboost, a company that specializes in using AI to help researchers and grant writers to write project abstracts more efficiently. Another tool with more broad use cases is ChatGPT.

Grantboost uses Generative AI to take in information about the grant opportunity and information about the problem being solved to create custom proejct abstracts based on the the specific needs of the researcher or grant writer.

One of the key benefits of using an AI-powered tool like Grantboost or ChatGPT is that it can save writers a significant amount of time and effort. Writing a project abstract can be a time-consuming and challenging process, particularly for those who are not experienced in academic writing. When asking for funding, the language being used in the abstract is incredibly important. If you’re not experienced in technical writing or fundraising, it can be a big challenge just to understand what a good proposal looks like. By using an AI-powered tool like Grantboost, writers can generate a high-quality project abstract in a matter of minutes, rather than spending hours focusing on just trying to get the language and tone right.

In addition, using an AI-powered tool can help to ensure that the project abstract is of high quality and meets the requirements of the funding agency or academic institution. Grantboost’s takes in information about the Grant opportunity to make sure that the abstract is aligned with the priorities of the Funder. This means that the project abstract generated by the tool is more likely to be successful in securing funding or attracting attention from potential collaborators.

Of course, it is important to note that using an AI-powered tool to write a project abstract does not mean that the writer can simply sit back and let the tool do all the work. The writer still needs to provide input and guidance to the tool to ensure that the project abstract accurately reflects the research project or proposal. This might involve inputting key information such as the research question, methodology, and expected outcomes, as well as providing feedback on the generated project abstract and making any necessary revisions.

In conclusion, AI-powered tools like Grantboost can be a valuable resource for writers who are looking to streamline the process of writing project abstracts. By using machine learning to generate successful grant proposals and research abstracts, these tools can generate high-quality project abstracts in a matter of minutes, saving writers time and effort. However, it is important to note that these tools should be used in conjunction with human input and guidance to ensure that the project abstract accurately reflects the research project or proposal. By combining the power of AI with human expertise, writers can produce project abstracts that are both efficient and effective.

Project abstracts are an important component of academic writing that provide a brief summary of a research project or proposal. They serve to define the project, communicate objectives and expected outcomes, and can be used to promote the research to a wider audience. By understanding the key elements of a project abstract, researchers and students can ensure that their work is effectively communicated and stands out in a crowded field of academic writing.

Transform Your Grant Writing with Grantboost: Join Our Beta and Try Our Project Abstract Generator Today!

As a nonprofit grant writer, you know the importance of making an impact in your community. That’s why we’re excited to announce Grantboost - a platform designed specifically to help you write better grants faster.

Grantboost is a game-changer, my friends. It’s a one-stop-shop for all your grant writing needs, and it’s completely free. That’s right, free. We’re about to launch our closed beta, and we’re giving you the opportunity to be one of the first to try out our revolutionary ✨ project abstract generator✨

The project abstract generator is a powerful tool that will help you create compelling abstracts for your grant proposals in just a few clicks. No more struggling to find the right words or spending hours writing and rewriting. With Grantboost, you’ll have everything you need to make a real difference in your community.

So what are you waiting for? Sign up for our closed beta today and join the revolution. With Grantboost, you’ll be able to write better grants faster than ever before.

The Ultimate Grant Writing Guide (and How to Find and Apply for Grants)

Securing grants requires strategic planning. Identifying relevant opportunities, building collaborations, and crafting a comprehensive grant proposal are crucial steps. Read our ultimate guide on grant writing, finding grants, and applying for grants to get the funding for your research.

Updated on February 22, 2024

Embarking on a journey of groundbreaking research and innovation always requires more than just passion and dedication, it demands financial support. In the academic and research domains, securing grants is a pivotal factor for transforming these ideas into tangible outcomes.

Grant awards not only offer the backing needed for ambitious projects but also stand as a testament to the importance and potential impact of your work. The process of identifying, pursuing, and securing grants, however, is riddled with nuances that necessitate careful exploration.

Whether you're a seasoned researcher or a budding academic, navigating this complex world of grants can be challenging, but we’re here to help. In this comprehensive guide, we'll walk you through the essential steps of applying for grants, providing expert tips and insights along the way.

Finding grant opportunities

Prior to diving into the application phase, the process of finding grants involves researching and identifying those that are relevant and realistic to your project. While the initial step may seem as simple as entering a few keywords into a search engine, the full search phase takes a more thorough investigation.

By focusing efforts solely on the grants that align with your goals, this pre-application preparation streamlines the process while also increasing the likelihood of meeting all the requirements. In fact, having a well thought out plan and a clear understanding of the grants you seek both simplifies the entire activity and sets you and your team up for success.

Apply these steps when searching for appropriate grant opportunities:

1. Determine your need

Before embarking on the grant-seeking journey, clearly articulate why you need the funds and how they will be utilized. Understanding your financial requirements is crucial for effective grant research.

2. Know when you need the money

Grants operate on specific timelines with set award dates. Align your grant-seeking efforts with these timelines to enhance your chances of success.

3. Search strategically

Build a checklist of your most important, non-negotiable search criteria for quickly weeding out grant options that absolutely do not fit your project. Then, utilize the following resources to identify potential grants:

- Online directories

- Small Business Administration (SBA)

- Foundations

4. Develop a tracking tool

After familiarizing yourself with the criteria of each grant, including paperwork, deadlines, and award amounts, make a spreadsheet or use a project management tool to stay organized. Share this with your team to ensure that everyone can contribute to the grant cycle.

Here are a few popular grant management tools to try:

- Jotform : spreadsheet template

- Airtable : table template

- Instrumentl : software

- Submit : software

Tips for Finding Research Grants

Consider large funding sources : Explore major agencies like NSF and NIH.

Reach out to experts : Consult experienced researchers and your institution's grant office.

Stay informed : Regularly check news in your field for novel funding sources.

Know agency requirements : Research and align your proposal with their requisites.

Ask questions : Use the available resources to get insights into the process.

Demonstrate expertise : Showcase your team's knowledge and background.

Neglect lesser-known sources : Cast a wide net to diversify opportunities.

Name drop reviewers : Prevent potential conflicts of interest.

Miss your chance : Find field-specific grant options.

Forget refinement : Improve proposal language, grammar, and clarity.

Ignore grant support services : Enhance the quality of your proposal.

Overlook co-investigators : Enhance your application by adding experience.

Grant collaboration

Now that you’ve taken the initial step of identifying potential grant opportunities, it’s time to find collaborators. The application process is lengthy and arduous. It requires a diverse set of skills. This phase is crucial for success.

With their valuable expertise and unique perspectives, these collaborators play instrumental roles in navigating the complexities of grant writing. While exploring the judiciousness that goes into building these partnerships, we will underscore why collaboration is both advantageous and indispensable to the pursuit of securing grants.

Why is collaboration important to the grant process?

Some grant funding agencies outline collaboration as an outright requirement for acceptable applications. However, the condition is more implied with others. Funders may simply favor or seek out applications that represent multidisciplinary and multinational projects.

To get an idea of the types of collaboration major funders prefer, try searching “collaborative research grants” to uncover countless possibilities, such as:

- National Endowment for the Humanities

- American Brain Tumor Association

For exploring grants specifically for international collaboration, check out this blog:

- 30+ Research Funding Agencies That Support International Collaboration

Either way, proposing an interdisciplinary research project substantially increases your funding opportunities. Teaming up with multiple collaborators who offer diverse backgrounds and skill sets enhances the robustness of your research project and increases credibility.

This is especially true for early career researchers, who can leverage collaboration with industry, international, or community partners to boost their research profile. The key lies in recognizing the multifaceted advantages of collaboration in the context of obtaining funding and maximizing the impact of your research efforts.

How can I find collaborators?

Before embarking on the search for a collaborative partner, it's essential to crystallize your objectives for the grant proposal and identify the type of support needed. Ask yourself these questions:

1)Which facet of the grant process do I need assistance with:

2) Is my knowledge lacking in a specific:

- Population?

3) Do I have access to the necessary:

Use these questions to compile a detailed list of your needs and prioritize them based on magnitude and ramification. These preliminary step ensure that search for an ideal collaborator is focused and effective.

Once you identify targeted criteria for the most appropriate partners, it’s time to make your approach. While a practical starting point involves reaching out to peers, mentors, and other colleagues with shared interests and research goals, we encourage you to go outside your comfort zone.

Beyond the first line of potential collaborators exists a world of opportunities to expand your network. Uncover partnership possibilities by engaging with speakers and attendees at events, workshops, webinars, and conferences related to grant writing or your field.

Also, consider joining online communities that facilitate connections among grant writers and researchers. These communities offer a space to exchange ideas and information. Sites like Collaboratory , NIH RePorter , and upwork provide channels for canvassing and engaging with feasible collaborators who are good fits for your project.

Like any other partnership, carefully weigh your vetted options before committing to a collaboration. Talk with individuals about their qualifications and experience, availability and work style, and terms for grant writing collaborations.

Transparency on both sides of this partnership is imperative to forging a positive work environment where goals, values, and expectations align for a strong grant proposal.

Putting together a winning grant proposal

It’s time to assemble the bulk of your grant application packet – the proposal itself. Each funder is unique in outlining the details for specific grants, but here are several elements fundamental to every proposal:

- Executive Summary

- Needs assessment

- Project description

- Evaluation plan

- Team introduction

- Sustainability plan

This list of multi-faceted components may seem daunting, but careful research and planning will make it manageable.

Start by reading about the grant funder to learn:

- What their mission and goals are,

- Which types of projects they have funded in the past, and

- How they evaluate and score applications.

Next, view sample applications to get a feel for the length, flow, and tone the evaluators are looking for. Many funders offer samples to peruse, like these from the NIH , while others are curated by online platforms , such as Grantstation.

Also, closely evaluate the grant application’s requirements. they vary between funding organizations and opportunities, and also from one grant cycle to the next. Take notes and make a checklist of these requirements to add to an Excel spreadsheet, Google smartsheet, or management system for organizing and tracking your grant process.

Finally, understand how you will submit the final grant application. Many funders use online portals with character or word limits for each section. Be aware of these limits beforehand. Simplify the editing process by first writing each section in a Word document to be copy and pasted into the corresponding submission fields.

If there is no online application platform, the funder will usually offer a comprehensive Request for Proposal (RFP) to guide the structure of your grant proposal. The RFP:

- Specifies page constraints

- Delineates specific sections

- Outlines additional attachments

- Provides other pertinent details

Components of a grant proposal

Cover letter.

Though not always explicitly requested, including a cover letter is a strategic maneuver that could be the factor determining whether or not grant funders engage with your proposal. It’s an opportunity to give your best first impression by grabbing the reviewer’s attention and compelling them to read further.

Cover letters are not the place for excessive emotion or detail, keep it brief and direct, stating your financial needs and purpose confidently from the outset. Also, try to clearly demonstrate the connection between your project and the funder’s mission to create additional value beyond the formal proposal.

Executive summary

Like an abstract for your research manuscript, the executive summary is a brief synopsis that encapsulates the overarching topics and key points of your grant proposal. It must set the tone for the main body of the proposal while providing enough information to stand alone if necessary.

Refer to How to Write an Executive Summary for a Grant Proposal for detailed guidance like:

- Give a clear and concise account of your identity, funding needs, and project roadmap.

- Write in an instructive manner aiming for an objective and persuasive tone

- Be convincing and pragmatic about your research team's ability.

- Follow the logical flow of main points in your proposal.

- Use subheadings and bulleted lists for clarity.

- Write the executive summary at the end of the proposal process.

- Reference detailed information explained in the proposal body.

- Address the funder directly.

- Provide excessive details about your project's accomplishments or management plans.

- Write in the first person.

- Disclose confidential information that could be accessed by competitors.

- Focus excessively on problems rather than proposed solutions.

- Deviate from the logical flow of the main proposal.

- Forget to align with evaluation criteria if specified

Project narrative

After the executive summary is the project narrative . This is the main body of your grant proposal and encompasses several distinct elements that work together to tell the story of your project and justify the need for funding.

Include these primary components:

Introduction of the project team

Briefly outline the names, positions, and credentials of the project’s directors, key personnel, contributors, and advisors in a format that clearly defines their roles and responsibilities. Showing your team’s capacity and ability to meet all deliverables builds confidence and trust with the reviewers.

Needs assessment or problem statement

A compelling needs assessment (or problem statement) clearly articulates a problem that must be urgently addressed. It also offers a well-defined project idea as a possible solution. This statement emphasizes the pressing situation and highlights existing gaps and their consequences to illustrate how your project will make a difference.

To begin, ask yourself these questions:

- What urgent need are we focusing on with this project?

- Which unique solution does our project offer to this urgent need?

- How will this project positively impact the world once completed?

Here are some helpful examples and templates.

Goals and objectives

Goals are broad statements that are fairly abstract and intangible. Objectives are more narrow statements that are concrete and measurable. For example :

- Goal : “To explore the impact of sleep deprivation on cognitive performance in college students.”

- Objective : “To compare cognitive test scores of students with less than six hours of sleep and those with 8 or more hours of sleep.”

Focus on outcomes, not processes, when crafting goals and objectives. Use the SMART acronym to align them with the proposal's mission while emphasizing their impact on the target audience.

Methods and strategies