The Vernacular Architecture of Kerala: A Case Study of Mishkal Mosque of Calicut, India

By Kenner N. Carmody ( Master in Design Studies / Energy & Environment , Class of 2019), through the Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture Research Fellowship 2019

This exhibition is designed to provide a small insight and broad introduction to the climate, culture, and context of Kerala and the city of Calicut through drawings and photographs.

The heat during the summer season in Kerala is brutal. The sun, almost vertical in the sky at this latitude, shines relentlessly on the Grand Bazaar Market in Calicut at midday. In fact, the local government prohibits manual labor during these afternoon hours, but judging by the ferocious loading of trucks, motorbikes and handcarts, nobody has taken notice. Calicut, a bustling maritime city on the Malabar Coast of India, has existed under this stroke-inducing sunlight since the dawn of the medieval spice trade, when Arab traders first introduced Islam to the Indian subcontinent, not by war and conquest, but rather by trade and commerce. Save for the effects of benign neglect witnessed by the aging architecture and infrastructure here, not much has changed in the old quarter of this city. Indeed, in the early morning hours, before the onset of cacophonous motorbike, truck, and automobile traffic – one can imagine the city sounds and smells much as it did well before the industrial age.

The genesis of this research began as an effort to document a building representative of a regional style of architecture not largely published within the domain of vernacular timber construction. Mishkal Mosque, a 16th-century laterite (an earthen block that is cut out of the ground to form masonry blocks in the region) and timber building in Calicut, was selected for its exemplar building tectonics, qualities of light and shade, and its material composition considering its unique position in India. This research not only aims to contribute to general scholarship on architecture in the region, but also endeavors to make contributions to the methodologies for the study of historic vernacular buildings as well as framing larger questions around preservation, maintenance, and building types. To date, the vernacular buildings in Kerala have been studied for their religious and cultural significance as well as their relationship to broader art and architectural heritage, but their detailed material composition, tectonics, and environmental and geographical relationship to the people and landscape remain under examined.

Composed of a tiered timber superstructure set atop coursed laterite stone masonry at the ground floor (rendered with mud-lime plaster), Mishkal Mosque is one of the oldest and largest of Kerala style mosques and is located at the center of the historic Mappila Muslim quarter in Calicut, called Kuttichira. Unlike any other architecture on the Indian subcontinent, this architectural style is a combination of various features born of its local tropical climate and context. Proportionally, the building exhibits more roof than it does façade, as the building consists of a series of tiered volumes, each wrapped by an umbrella-like assemblage of timber rafters and clay tile shingles – with each tier resting on the one below. Shading the building is paramount: Even at the second floor veranda, one must almost lay prone to steal a view to the exterior, as the roof reaches as far as possible beyond the exterior masonry walls, further compressing the already narrow balcony space. Supported principally by the masonry walls that extend beyond the ground floor, the slender columns at the veranda serve to tie the roof down more than transfer any vertical loads to the ground. Instead, this barely habitable zone acts as a buffer, a thickened zone within the building façade that shields the second level of the building from the nearly vertical year-round solar radiation, as well as the almost equally intense indirect horizontal solar radiation abundant in the region. The third and fourth levels of the building are underused or even unused spaces in the building. They do however, contribute to the mosque’s monumental scale. And even as they are underused spaces in the building, the third and fourth levels are treated with equal consideration when examining how they address the tropical monsoon climate and context. Both the third and fourth levels of the building use horizontal latticed screen walls that provide access to views while reducing glare from both the direct and indirect sunlight. The roof framing on the fourth level at the hip roof is perhaps the most unique feature of the building’s timber framing. The roof framing at the hip roof bears on a single timber drum which holds the rafters in place. According to local building tradition, and my conversations with local carpenters, one may not call oneself a master builder until this particular joint has been successfully constructed.

To observe all of this, I visited the mosque during the peak of the summer dry season just before the summer monsoon season begins, when not a single cloud is present in the sky. Upon entering the mosque from the south side, the ground floor masonry walls break the searing daylight sun. A continuous gallery protects the principal worshiping spaces of the building, forming a solid façade, punctuated only by modest doorways guarded with solid teak door panels. The transition from outside to inside of the building is immediately palpable, with an almost blinding transition from white light to a pitch darkness as one’s eyes adjust to the contrasting conditions. There is an immediate sense of refuge upon entering the ante chamber and main prayer hall at the ground floor, as there is a clear sense of the local architecture’s ability to banish direct sunlight from the building’s interior. The building is organized as a sequence of vertical rooms that increase in height as one ascends the building through series of stairs that separate one floor from another. Qualities of light, shade, and thermal comfort are also stratified vertically. As one moves from the ground and second floor, with their heavy mass and punched openings to the lightweight third and fourth levels of the building which exhibit a softer light and more well-ventilated spaces enabled by light-diffusing louvers and an enclosure made entirely of timber – save for the clay tile roofing.

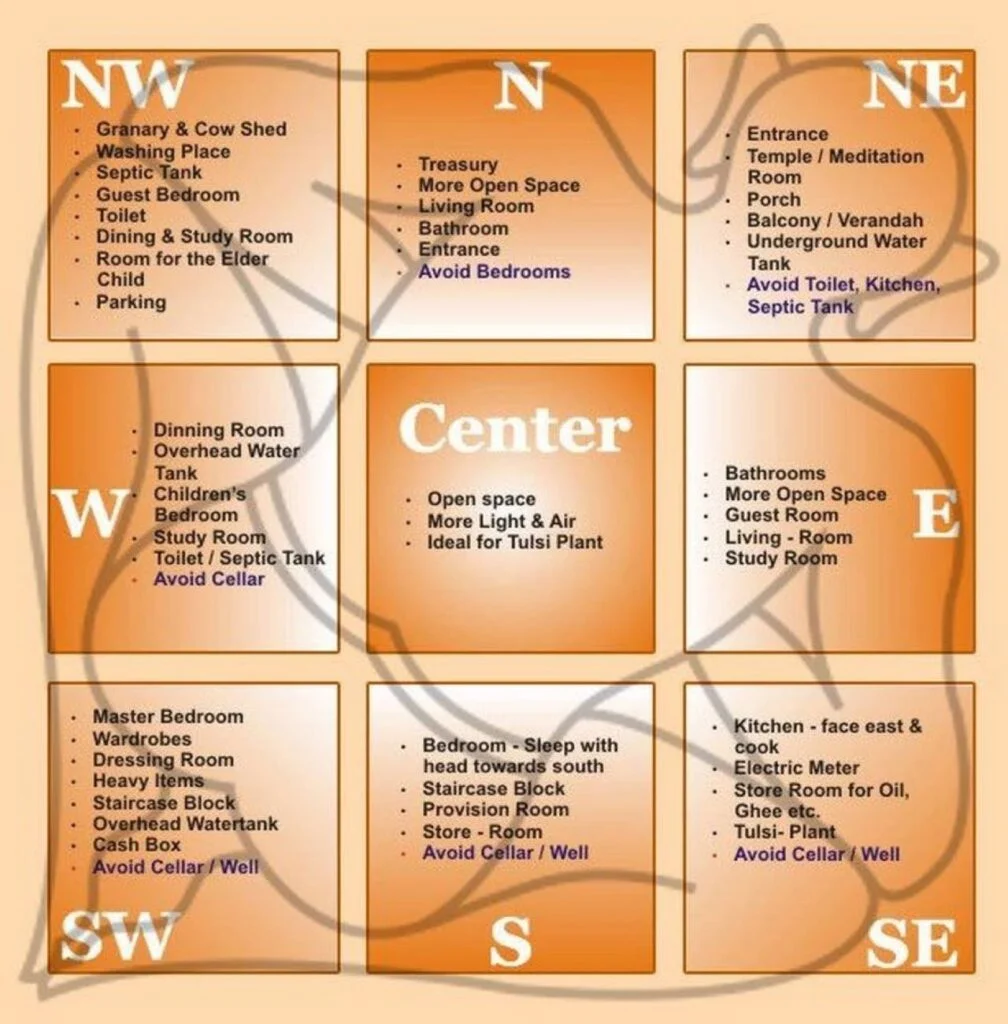

Vernacular Architecture of Kerala: Learning Sustainability from the Best

Table of Contents

Introduction to Vernacular Architecture

Vernacular architecture is a style of architecture that is designed and built for the needs of people, with locally available materials, reflecting upon the culture of the place. Vernacular architecture is specific to a region and climate. In theory, a vernacular building is built without the guidance of a professional, like an architect. Thus, vernacular architecture is cost-effective, climate-responsive, modest, sustainable, and a reflection of the culture of the place.

Introduction to Kerala and its Architecture

Kerala is the twenty-fifth largest state in India, in the area surrounded by Karnataka on the northeast, Tamil Nadu on the east, and the Arabian Sea on the west. With a coastline of around 600km of the Arabian sea, Kerala is known for its spectacular flora and fauna, backwaters, and respect for its culture. Kerala prides itself for being the flag bearer for not just how a culture can respect its past, but also march forward with growth & progress as well. Kerala’s vernacular architecture, which is still heavily practiced throughout Kerala and some of south India, is one such inspiration for all. It is in striking contrast with the Dravidian Architecture followed in other parts of South India and is strongly influenced by Indian Vedic architectural science (Vastu Shastra).

History and Origin

Kerala gets its indigenous style of architecture from all climatic, geographical, and historical factors. Favored by generous rains because of monsoon and bright sun, this land is lush green with foliage and rich in beast life. In the uneven terrain of this region, mortal habitation is distributed thickly in the rich low- lands and sparsely towards the hostile mounds. Heavy rains have brought in presence of large water bodies in form of lakes, gutters, backwoods, and lagoons. The climatic factors, therefore, made its significant benefactions in developing the architecture style, to fight the wettest climatic conditions coupled with heavy moisture and harsh tropical summers. Geographically, Kerala is a narrow strip of land lying in between the seacoast of peninsular India and confined between the towering Western Ghats on its east and the vast Arabian ocean on its west. History also played its benefactions on the Kerala architecture. The towering Western Ghats on its east have successfully averted influences of bordering Tamil countries into present-day Kerala in after times. While the Western Ghats insulated Kerala to a lesser extent from Indian conglomerates, the exposure of the Arabian ocean on its east brought in close connections between the ancient people of Kerala with major maritime societies like Egyptians, Romans, Arabs, and so on. Kerala’s rich spice polish brought it a center of global maritime trade until the ultramodern ages, helping several transnational powers to laboriously engage with Kerala as trading mates. This helped in bringing in influences of these civilizations into Kerala’s architecture.

Different types of Kerala Architecture

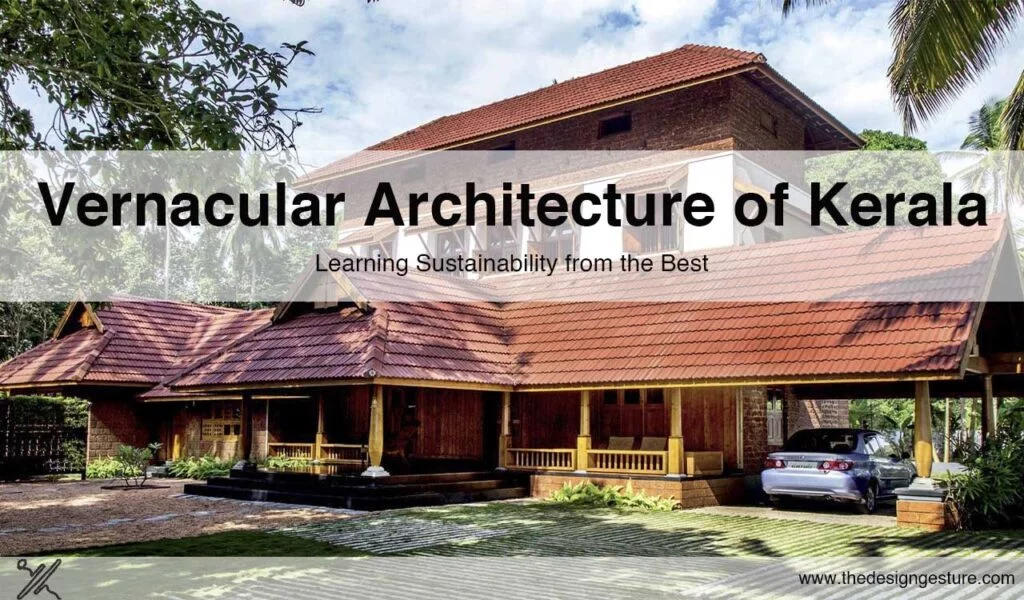

The architecture of Kerala is divided into two parts, Nalukettu and Ettukettu.

Nālukettu is the home of generations of joint family kinfolk or Tharavadu, where many generations of a matrilineal family lived. These types of structures are observed in the Indian state of Kerala. The traditional architecture of Kerala is a rectangular structure where four blocks are joined with a central, open to the sky courtyard.

The four halls on each side are named Vadakkini (northern block), Padinjattini (western block), Kizhakkini (eastern block), and Thekkini (southern block). The architecture was especially provisioned to large families of the traditional tharavadu, to live under one roof and enjoy the commonly owned facilities and services of the marumakkathayam homestead.

Ettukettu, which is eight halls with two central yards) or Pathinarukettu, which is sixteen halls with four central yards, is the further elaborate forms of the same architecture. Every structure faces the sun, and in some well-conditioned designed nalukettu, there’s excellent ventilation as well. Temperatures, indeed in the heat of summer, are markedly lower within the nalukettu.

Elements of Nalukettu and Ettukettu

It’s a structure containing a door, forming part of the boundary wall for the house with a tiled roof on top. It’s the formal entry to the site with the house.

It’s the porch of the house led by steps. Traditionally, it has a pitch-tiled roof with pillars supporting the same.

Chuttu gallery

In Kerala architecture, the poomukham is accompanied by an open passage, the chuttu gallery, which leads to either side of the house surrounding it.

Charupadi

Along the chuttu gallery and the poomukham are traditionally sculpted, rustic, wooden, or cement benches. These benches are called charupadi.

Ambal Kulam

Nearly every Nalukettu has its own Kulam or Pond for bathing of its members. At the end of Chuttu verandah, there is a small pond constructed with debris on sides where lotus or Ambal is planted. The water bodies are maintained to maintain energy flow inside.

Nadumuttam

A typical Nadumuttom of Kerala Nalukettu is a courtyard placed at the prime center of the Nalukettu. This is surrounded by an open corridor square-shaped, in the exact middle of the house dividing the house into its four sides.

Key Features of Vernacular Architecture of Kerala

Orientation and planning.

Kerala experiences a hot and humid climate and hence the orientation of the building becomes one of the crucial aspects of planning.

The building should face the direction of the prevailing winds rather than the sun. This helps in maintaining cross ventilation in a humid climate. Houses preferably face East direction according to the direction of prevailing winds.

Cross ventilation

The juxtaposition of open-and-closed spaces in a way to allows a continuous flow of air.

Being in a tropical climate, cross ventilation plays an important role in creating comfortable spaces. The presence of high moisture content in hot air causes discomfort for the user.

Courtyard spaces are extensively used in houses of Kerala of all scales. It helps in achieving passive cooling and reduces the dependence on HVAC systems. It also helps to induce continuous air movement.

Openings in walls facing each other and internal partitions help in increasing cross-ventilation. Using vertical louvers and large window shutters helps to reduce thermal discomfort with ample daylight.

Solar Shading

The temperature in Kerala can rise to up to 40 degrees Celsius in summers . Therefore, sun shading strategies and elements become vital.

Traditional buildings in Kerala have an internal and external verandah. The external verandah acts as buffer space to reduce direct exposure to sunlight, whereas the internal verandah allows light to enter the building via a courtyard.

The east and west façade should be least exposed to the sun to prevent late afternoon and early morning heat. One way is to have dense tree plantations around these façades.

Overhangs, louvers, canopies, and so on are used for shading. Shading devices for doors and windows are also used to avoid solar heat gain.

Roof Insulation

The most distinctive visual form of Kerala’s architecture is the high, steep sloping roof with eaves constructed to shade the walls of the house and to repel the heavy thunderstorm, typically laid with tiles or thatch, and supported on a roof framework made of hardwood and timber. Structurally, the roof frame is supported on the pillars standing on a raised platform from the ground, for protection against moistness and insects in the tropical climate. Many times, the walls are also made of timber, locally available in Kerala.

Gable windows were introduced at either end of the roof to maximize attic ventilation of the room when the ceiling was incorporated for these spaces. Most structures of Kerala appear to be low height visually, because of high, steep sloping of roofs, which cover walls from rains and direct sunshine.

Prevention from Rain

Kerala receives heavy rainfall for a significant part of the year which requires effective solutions to endure the extreme climatic conditions.

Buildings should be placed at a high plinth to restrict water from entering inside. Sloping roof should be provided to avoid the accumulation of rainwater on the surfaces.

Commonly Used Materials

Kerala architecture uses local materials that are locally available and also sustainable. Some of the commonly used building materials in the Kerala area are bamboo , earth, lime, timber, leaves, and so on.

Laterite is a hardened earth layer formed because of the weathering action of acid jewels. It is dug out from the earth and its compressive strength can be significantly higher than that of burnt clay bricks. It is non-porous and has poor water retention capacity. It is found 3 to 15 meters below the ground. The top one to two meters is soft, and the bottom merges with the clay layer. Laterite can be called the “Blessing of Kerala” since 80 percent of the state is covered with it. In Kerala, the foundations were erected with laterite blocks.

Laterite has been extensively used for constructing the superstructure. Using burnt bricks for construction was rare, except with a few palaces. Currently, the laterite blocks can be machine cut as well. The advantage of these machine-cut blocks is that they have much higher compressive strength. The disadvantage is that these have to be transported over a long distance, ergo the process involves further energy.

Lime, which was obtained from shells, was burnt in kilns and used as mortar in structures in Kerala. It was produced by beating it round with a stiff bristle encounter, after adding water. It was beaten with a special rustic tool in tanks specifically made for this purpose. This process helped to increase its strength and plasticity, reducing the amount of water to be added. This is beneficial as the strength of lime further improves when lower water is used, and when it’s air-dried. Many organic details were also added to increase the strength of the lime, hence the mortar.

In theory, it is believed that lime has a lot of disadvantages like slow setting, not having enough strength, and so on. But, in contrast, lime is significantly sustainable as a binding material, as various studies show that it is much lower energy-consuming when compared with cement. Cement is a high energy-consuming material with limestone as one of the main constituents for its manufacture. When cement is used as mortar in a wall, the bricks cannot be recovered for play, if the structure is demolished latterly. If lime is used, the bricks can be reused, which eventually makes lime mortar more sustainable.

Granite is the most common stone used for construction in Kerala. Traditional Kerala houses use a granite slab below the ground to avoid the risk of dampness. Whereas thatch or clay tiles on the sloped roof, keep it dry.

The state does not have deposits of limestone or sandstone. Granite is a hard stone and is used in the foundations. It has been infrequently used for the superstructure until lately.

In the olden days, it was a locally available material, but now big quarries have come up in the western ghats, many of whom are present in vulnerable and fragile areas. Granite that is being excavated from these places is not sustainable, because of the adverse impact it causes on our terrain as landslides and other natural disasters.

Timber is one of the most used structural materials in Kerala. It was extensively available in many kinds and with high durability as well. Teak, jack wood, Anjili wood, and Thembavu were some of the commonly used types of timber.

Structures with timber walls were constructed in Travancore till about 100 years ago. The vernacular architecture of Kerala considerably uses timber for walls, doors, windows, intermediate floors, and roofs.

The biggest advantage of timber is that by using them in our buildings, the carbon gets locked. Trees are the only things that can convert carbon dioxide in the atmosphere into oxygen. If timber is allowed to decay or used as firewood, then the carbon is released back into the atmosphere, completing the carbon cycle.

Every timber that we use in our structures needs not be sustainable. However, also it is less sustainable if the source of the timber is from cutting down virgin forests.

In earlier times, several large structures were constructed using earth or mud. The sun-dried mud bricks may be used for the alternate story of a two-story structure, with the ground bottom made of laterite. They may also be used for the less important corridor of structures. Using earth blocks (without ramming or sun-dried bricks) was popular among the poorer sections of society.

Many structures constructed with laterite also use earth as mortar to save the cost of construction. The general print of the public is that a structure with earth blocks is sustainable. But most times, it need not be true.

The cost of the superstructure of a structure is only 15-20 percent of the overall cost of construction, meaning the rest of the structural units need not be sustainable at all. When the earth from the structure point is used, it becomes very sustainable. But if the material has to be transported over a distance, also the embodied energy will go over, reducing the sustainability factor. Strengthening of earth blocks by cement will also reduce the sustainability aspect. If interlocking earth blocks are used, also the sustainable character will be more since no cement mortar is involved.

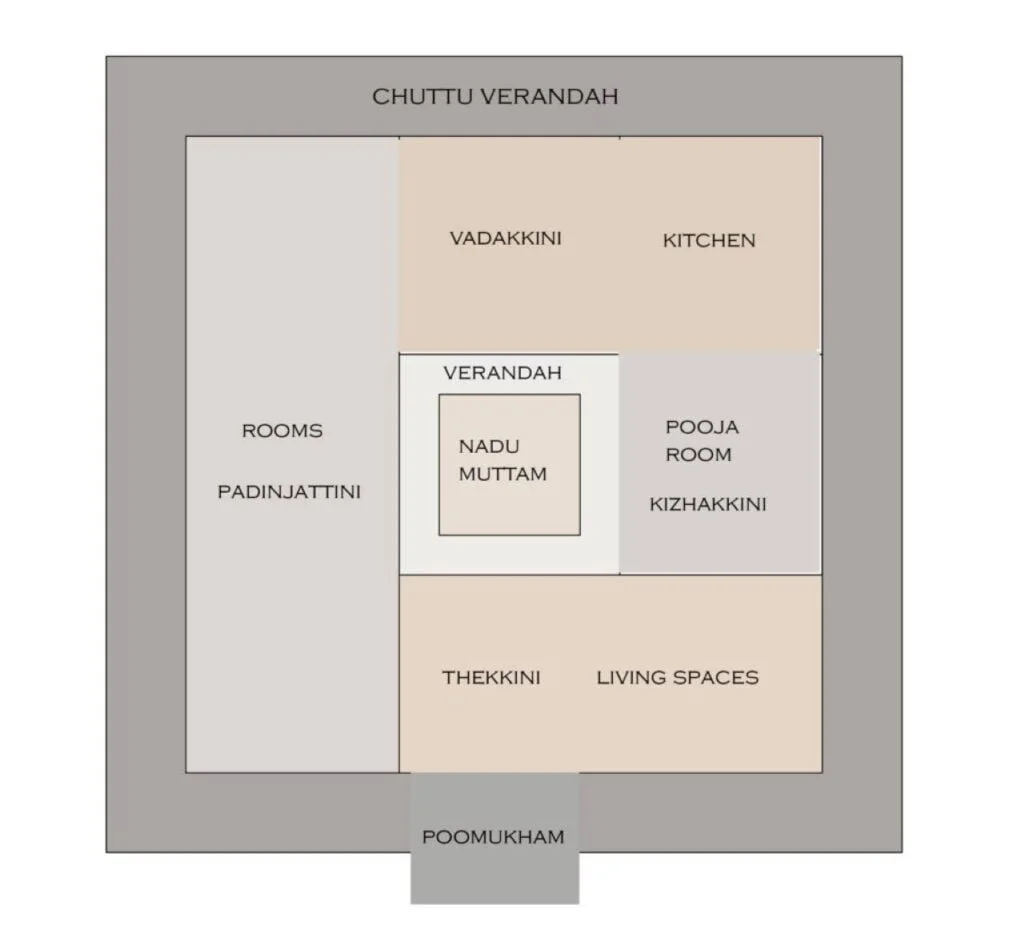

Influence of Vastu Shastra

One can notice the strong influence of Vastu shastra’ s study on the architecture of Kerala. The basic underlying belief is that every structure erected on earth has its own life, with a soul and personality which is shaped by its surroundings. The most important wisdom which Kerala has developed purely indigenously is Thachu-Shastra (Science of Carpentry) as the easy vacuity of timber and its heavy use of it.

From cattle sheds to trees, everything used to be planned and laid according to the ancient texts of shastra.

In traditional houses, the kitchen is strategically placed in the northeast corner as the prevailing winds blow from the southwest direction. These houses have pitched roofs and if the roof catches fire at any point, it will be blown away by the prevailing winds. A well would also be constructed close to it. In a house with a courtyard, the main living area is always in the southwest part, away from the fireplace. The puja room of the house is placed in the northeast corner and the idols face either east or west direction.

In two to three-storied houses of Noth Kerala, the northeast part is usually a single storey because of the kitchen. The bedrooms are present upstairs in the southwest direction.

There has been a rapid change in the architectural fraternity in the past two decades. The new trend has been fast-paced racing towards quantity over quality. Using craftsmen has declined considerably.

Therefore, to get out of this present crisis, an architecture typology, like the vernacular architecture of Kerala, that suits the environment, climate, and the people, should be developed. A blend of vernacular architecture with modern needs seems an appropriate solution.

Similar Articles

7 Interesting Ways Work From Home Lifestyle Affected Architects

Psychology of Architecture: It’s Surprisingly Interesting Impact on Human Behavior

How To Generate Good Secondary Incomes Along with 9-5 Job?

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 28 April 2021

Resilience of vernacular and modernising dwellings in three climatic zones to climate change

- Khadeeja Henna 1 ,

- Aysha Saifudeen 1 , 2 &

- Monto Mani 1

Scientific Reports volume 11 , Article number: 9172 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

4986 Accesses

13 Citations

34 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Energy science and technology

- Engineering

Climate change impacts buildings in multiple ways, including extreme weather events and thermal stresses. Rural India comprising 65% of the population is characterised by vernacular dwellings evolved over time to passively regulate and maintain comfortable indoors. Increasing modernization in rural habitations (transitions) evident from the ingress of modern materials and electro-mechanical appliances undermines the ability of building envelopes to passively regulate and maintain comfortable indoors. While such trends are deemed good for the economy, their underlying implications in terms of climate change have not been adequately examined. The current study evaluates the climate-resilience of vernacular dwellings and those undergoing transitions in response to three climate-change scenarios, viz, A1B (rapid economic growth fuelled by balanced use of energy sources), A2 (regionally sensitive economic development) and B1 (structured economic growth and adoption of clean and resource efficient technologies). The study examines dwellings characteristic to three rural settlements representing three major climate zones in India and involves both real-time monitoring and simulation-based investigation. The study is novel in investigating the impact of climate change on indoor thermal comfort in rural dwellings, adopting vernacular and modern materials. The study revealed higher resilience of vernacular dwellings in response to climate change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Ghost roads and the destruction of Asia-Pacific tropical forests

Heat health risk assessment in Philippine cities using remotely sensed data and social-ecological indicators

Expert review of the science underlying nature-based climate solutions

Introduction.

Climate change and its effect on human health, economy and environment is one of the most widely researched topics in the twenty-first century. Building and construction industry, the highest contributor to global emissions and climate change, is responsible for 39% of the global energy- and process-related emissions, with 17% from residential sector 1 . However, buildings are also the most vulnerable to climate change, especially in progressive and developing regions. Climate change could involve gradual/abrupt changes in temperatures to unprecedented rains, floods and cyclones. It impacts building thermal comfort, alters operating conditions and energy demands while rendering existing appliances inadequate 2 . This impact is evident as altered comfortable temperature conditions and increased heating/cooling energy demand. In 2018, 22% of the global final energy was consumed by residential buildings 1 , with 40% of energy utilization on space conditioning. This is projected to increase by 40% by 2050 over 2010 levels based on International Energy Agency’s (IEA) 6 ºC (6DS) scenario 3 . The energy consumed by buildings varies depending on the climate, lifestyle and building typology. Per capita energy consumed by buildings in prosperous countries in a cold climate zone like the United States or Canada, could be 5–10 times that of low-income countries in a warm climate zone in Africa or Latin America 4 . In 2018, India’s per capita residential energy consumption was less than 0.6 MWh while that of the US was over 10 MWh 5 . While 66% of India’s population resides in rural areas, only 18% of US population is rural 6 . However, unlike in westernised regions, the disparity in energy consumption between rural and urban India is huge (96 kWh in rural areas, 288 kWh in urban areas as in 2009) 7 . A 4 × increase in embodied energy (EE) and a 40 × increase in operational energy (OE) respectively has been observed with buildings transitioning from vernacular to modern 8 . If rural life in India rapidly transitions towards global urban lifestyles, the ecological stresses (resource extraction and greenhouse gas emissions) could exasperate global efforts to mitigate climate change. The national statistics indicate rapid transition from traditional climate-responsive houses constructed using locally available materials towards an urban-like dwellings adopting industry manufactured, energy-intensive materials, disregarding the local climate. In 2001, clay tiles roofs (32.5%) had given way to concrete (29%) by 2011 9 . A growth of 89% in the use of concrete and 76% increase in metal/asbestos roofing sheets has been witnessed between 2001 and 2011.

While vernacular dwellings have evolved to passively maintain comfortable indoors, modern dwellings inevitably rely on energy-intensive appliances for comfort. Modern buildings tend to be energy-intensive and result in huge emissions through their lifecycle. Residential energy consumption in India in 2014 was 50 times that in 1971 10 . Such increase could cripple global efforts to mitigate climate change. On the other hand, vernacular dwellings could hold key solutions for mitigation and adaptation to climate change, given their capability to withstand wider temperature variations with lower lifecycle energy-resource intensity 11 . This study attempts to assess the thermal performance of vernacular dwellings in three climate zones in India and the effect of material transitions on the thermal performance of these dwellings. The study also investigates the impact of climate change on their performance.

Literature review

The effect and severity of climate change on thermal comfort in dwellings can be measured as change in heating and/or cooling demand and resulting energy consumption. Severe cold climates are expected to witness reduction in heating demands, while warmer climates are expected to witness considerable increase in cooling demand 12 . The impact of climate change also varies according to building type. Wang and Chen 13 , studied impact of climate change on seven commercial buildings and two residential buildings in different climate zones across the US and found a net increase in energy consumption in warm and moderate climates while a net decrease in energy consumption in colder climates. Karimpour et al. 14 investigated the impact of different building envelope (insulation and glazing) configurations in mild Australian temperate climate on energy consumption in current and future climates and recommended higher insulation, double glazing and low emittance glass in response to increased cooling energy demand. Huang and Gurney 15 studied US building stock, focusing on commercial building types, across three building age classes- pre-1980, post-1980 and new-2004, to understand their performance under climate change. The buildings equipped with the newest technology with more energy efficient equipment and better insulation exhibited higher efficiency in maintaining comfortable indoor environment.

Naturally ventilated (NV) vernacular dwellings constructed using local materials have lower embodied energy and ecological footprint. Mani et al. 16 estimated the ecological footprint of conventional dwellings to be 2.5 times that of traditional dwellings in West Bengal, India. Vernacular buildings also tend to be resilient in wider range of temperatures in providing comfort when compared to conventional buildings 17 , 18 , 19 . Dili et al. 20 studied vernacular and conventional dwellings in Kerala, India, with warm-humid climate, and confirmed that vernacular dwellings outperformed conventional dwellings in maintaining indoor comfort across seasons. Shastry et al. 21 studied the impact of modern transitions on rural dwellings in West Bengal, India, and found an increase in average indoor temperatures from 7 to 10 °C. Given the lower EE and OE energy and higher resilience to maintain indoor thermal comfort in response to wider variations in weather conditions, vernacular dwellings could hold important insights for mitigation and adaptation to climate change.

Methodology

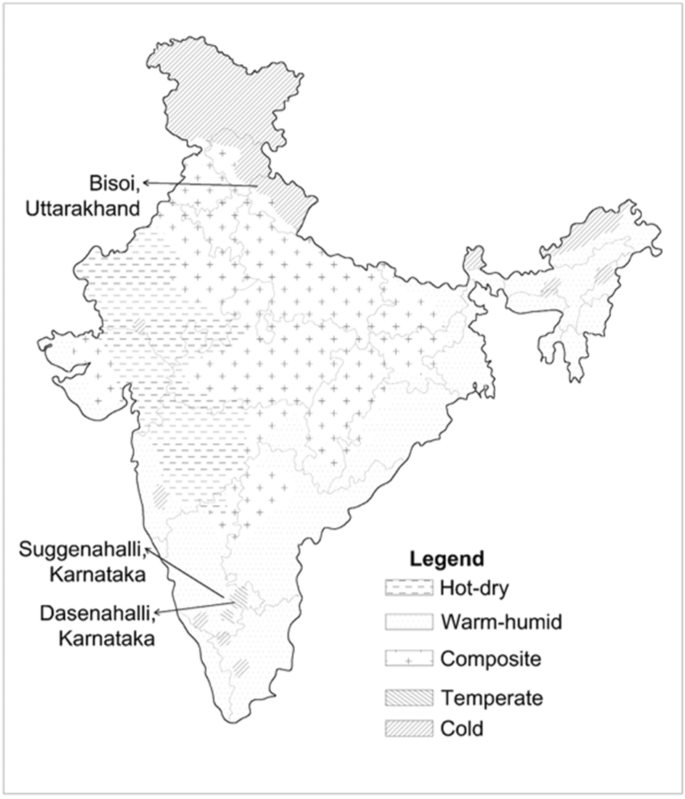

India is broadly classified into five climatic zones- hot-dry, warm-humid, composite, temperate and cold 22 . In this study, three distinct villages belonging to warm-humid, temperate and cold climate zones have been selected to represent warm, moderate and cold climatic conditions in India, respectively. A typical vernacular dwelling from each village was selected for detailed investigation into climate-resilience. Real-time indoor air temperatures at different locations in the dwellings were recorded at 30-min intervals using calibrated Resistance Temperature Detector (RTD) data loggers (0.05 °C resolution and ± 1 °C accuracy). Real-time measurement of indoor parameters proceeded according to Class III level of detail as defined in 23 , widely adopted in thermal comfort field study research. It was important to prevent the loggers from interfering with the daily lives of the inhabitants as these loggers were being installed in occupied houses for almost a year. Calibrated simulation models of the vernacular dwellings were developed using DesignBuilder (v 3.4), an integrated building performance simulation package 24 . The model calibration essentially involved a correlation with real-time climatic-performance data (see Sect. 4 ). In order to examine performance of vernacular dwellings in response to climate change, weather files for both typical and future climate scenarios were generated using Meteonorm . Meteonorm is a global climatological tool, that derives data from weather stations between 1991 and 2010 and integrates IPCC AR4 (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change- Fourth Assessment Report) emission scenarios 25 . Three future scenarios, namely, A1B (rapid economic growth fuelled by balanced fossil/non-fossil energy use), A2 (regionally oriented economic development characterised by less innovation) and B1 (structured economic growth and adoption of clean and resource efficient technologies) are explored in this paper. Both A1B and A2 are high emission scenarios, with A2 resulting in higher global surface warming in the second half of the twenty-first century. B1 on the other hand is one of the scenarios with lowest emissions and global surface warming 26 . Modern transitions in each of the habitations were studied based on trends revealed through satellite imagery, field visits and government reports, and were incorporated in the simulation models to examine the impact of future climate change scenarios.

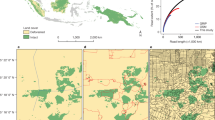

This study comprises three agrarian rural settlements (Fig. 1 ) namely Suggenahalli, Karnataka (12.816° N, 76.993° E), Dasenahalli, Karnataka (13.146° N, 77.465° E) and Bisoi, Uttarakhand (30.971° N, 77.928° E) belonging to warm-humid, temperate and cold climate zones respectively. In addition to the willingness of the inhabitants, these settlements were identified for unique vernacular architecture (Table 1 ) and an evident trend of modern transitions. The vernacular dwellings in these villages are naturally ventilated and constructed using locally available materials with local traditional know-how passed over generations.

(Adapted from National Building Code of India, 2005 22 ) and selected rural settlements: Figure shows the location of the rural settlements studied in this paper on the climate zone map of India. Suggenahalli lies in Warm-humid zone, Dasenahalli in Temperate zone and Bisoi in Cold zone. The authors used Autodesk AutoCAD 2018 (Product version: O.49.0.0 AutoCAD 2018) https://www.autodesk.com/products/autocad/overview?support=ADVANCED&plc=ACDIST&term=1-YEAR&quantity=1 to draw the map and mark the rural settlements on it.

Climatic zones in India.

The proximity and improved connectivity of Suggenahalli and Dasenahalli to Bengaluru city and Bisoi to Dehradun has helped spur modern lifestyles. Access to electricity and modern construction materials is evident as transitions in the dwellings. These transitions that mimic urban habitations are characteristic to many rural habitation and involve traditional local materials giving way to energy-intensive exotic materials 8 , 27 , 28 .

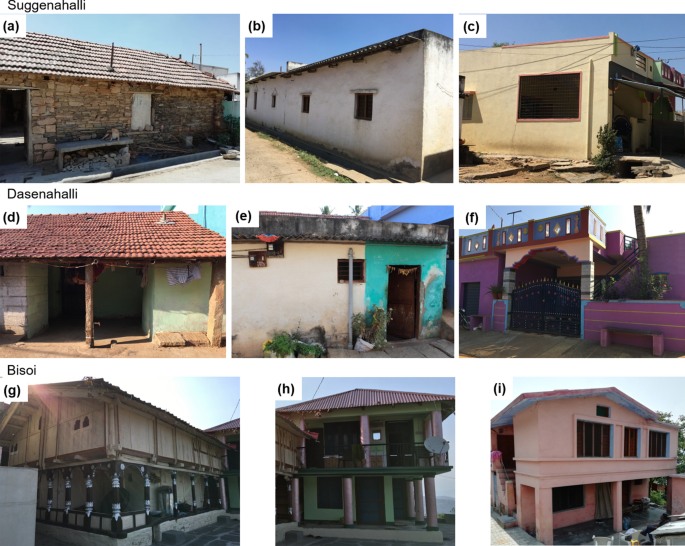

Transitions in vernacular dwellings were characterised by progressive inclusion of modern materials, while retaining the original form. Newer constructions adopted modern construction materials, seldom carrying a semblance of traditional form and indoor spaces. In Suggenahalli (Fig. 2 a–c), the thick rubble walls were increasingly being replaced by slender brick masonry, the pitched clay-tile roofs were replaced by flat AC sheet roofing and then by reinforced cement concrete (RCC) slabs, and the cool earthen floors have made way to cement flooring. In Dasenahalli (Fig. 2 d–f), clay from the agricultural fields were moulded into mud blocks to construct walls. These walls were increasingly being replaced by cement blocks, pitched clay tiled roof by tin/AC sheets and ultimately by flat RCC roof and the mud flooring by cement and tiles. Bisoi, which once depended on forest-harvested timber for houses, is faced with state regulations restricting the use of forest produce. This also has forced villagers to look for alternate building materials, with the older generation preferring vernacular dwellings, and the younger city-educated/employed generation preferring conventional dwellings. The geographic isolation by mountain ranges has moderated the rate of transitions and helped in higher retention of vernacular dwellings. The transitions in Bisoi (Fig. 2 g–i) mostly involve replacing of timber walls on the first floor by brick walls while retaining the ground floor stone and timber wall construction, the slate roof by metal sheets and pitched RCC roof and mud/timber flooring by cement flooring. Flat RCC roofs originally constructed revealed cracks under heavy snow load and were eventually replaced by sloping RCC roof. In all the three villages, material transitions remained the most prominent and evident type of transition. The current study examines the primary material transition in vernacular dwellings retaining their form and orientation for their thermal performance and resilience to climate change. Table 2 summarises the vernacular and conventional building materials used in constructing the simulation models for the three case studies.

Stages of material transition (from left to right) in vernacular dwellings in the three villages: Stages of transition in the use of construction materials for each rural settlement is shown in the figure. Images in each row from left to right shows transition from traditional materials to conventional materials. ( a ), ( d ) and ( g ) represents the typical vernacular construction using traditional materials in Suggenahalli, Dasenahalli and Bisoi, respectively. ( b ), ( e ) and ( h ) represent a common intermediate stage in the process of transition using conventional but mostly temporary materials in the three villages. ( c ), ( f ) and ( i ) are the final products of transitions in the three villages using conventional factory-made materials which are more permanent in nature.

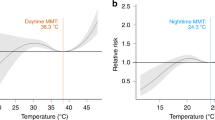

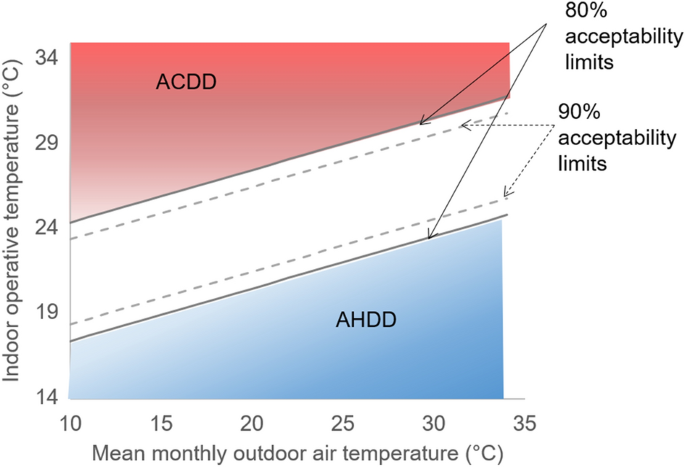

Studies focusing on naturally ventilated buildings rely on adaptive thermal comfort models to assess building climatic performance. These models more precisely accommodate the natural physiological ability to adapt indoor comfort requirements in response to external climatic (temperature) conditions. The performance of dwellings in this study adopts Adaptive Heating and Cooling Degree Days (AHDD and ACDD) calculated based on the Adaptive thermal comfort model (ATCM) incorporated in the ASHRAE 55 standard, 2010 29 . ATCM takes into account the acceptability of wider range of temperatures by occupants in naturally ventilated buildings, especially in tropical climates 30 . It illustrates a linear dependence of indoor operative temperatures on mean monthly outdoor temperatures and also describes a 90% and 80% acceptability limits indicating the percentage of occupants expressing comfort 31 . The days when indoor temperatures exceed acceptability limits, the corresponding ACDD and AHDD are computed as a measure of the augmented cooling or heating need (see Fig. 3 ):

Representation of ACDD and AHDD based on Adaptive Thermal comfort model, ASHRAE 55: The plot shown in the figure represents the Adaptive thermal comfort model defined in ASHRAE 55. Solid line indicates 80% acceptability limits and dotted line indicates 90% acceptability limits. Figure depicts the method adopted for calculating Adaptive Heating Degree Days (AHDD) and Adaptive Cooling Degree Days (ACDD). Indoor operative temperatures falling above or below the 80% acceptability limits multiplied by the duration for which the temperature lasts are used to calculate ACDD and AHDD, respectively. Duration for which the indoor operative temperatures fall above the 80% acceptability limit will require active cooling to attain comfort. Similarly, duration for which the indoor operative temperatures fall below the 80% acceptability limit will require active heating for comfort.

where \(T_{op.i}\) is the daily operative temperatures and \(T_{b.m}^{ul}\) and \(T_{b.m}^{ll}\) are the upper and lower limits of the monthly base temperature above and below which cooling and heating requirements surface. \(T_{b.m}^{ul}\) and \(T_{b.m}^{ll}\) are calculated based on ATCM for each month using the relation:

where T mm is the mean monthly outdoor temperature and x is the variability based on acceptability limit, which is 3.5 for 80% acceptability and 2.5 for 90% acceptability 31 , 32 .

Model calibration

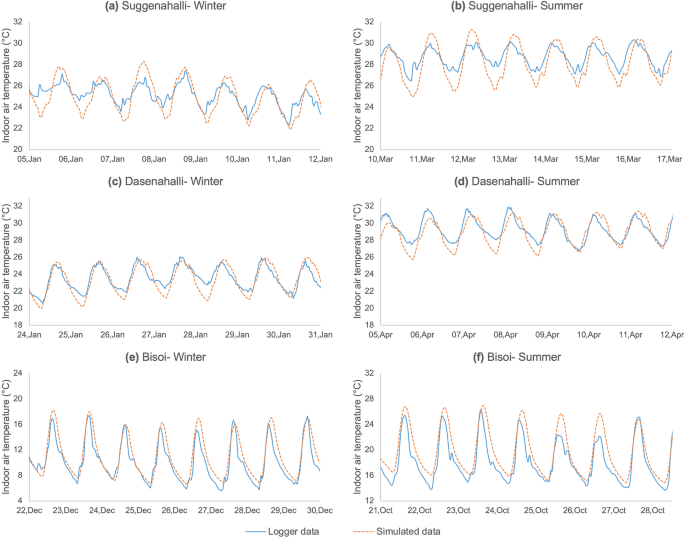

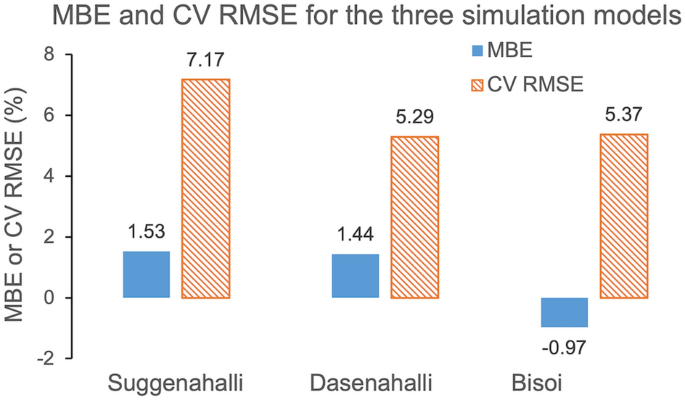

ASHRAE Guideline 14 suggest use of Mean Bias Error (MBE) and Coefficient of Variation of Root Mean Square Error (CV RMSE) for calibration of simulation model based on measured performance data 33 , 34 , 35 . MBE and CV RMSE indicate the relative and accumulated divergences between measured and simulated value, respectively. According to the guideline, for an acceptable calibrated simulation model, MBE hourly data should lie within ± 10% and CV RMSE hourly data should not exceed 30%. For this study, the simulated indoor air temperatures were calibrated based on real time measurements. Royapoor and Roskilly 36 in their study on performance of an office building had validated their EnergyPlus virtual building model by calculating MBE and CV RMSE. For better reliability, ASHRAE recommends using both statistical and graphical approaches to model calibration 33 , 37 , which has been adopted in this study: firstly, by graphically comparing the measured and simulated indoor air temperatures, and secondly, by calculating the MBE and CV RMSE. Figure 4 illustrates the concurrence between measured and simulated weeklong summer and winter temperatures for the three case studies. Since summer data for Bisoi was not accessible, a warm week in October was relied on as representative for summer. A one-on-one match between real-time and simulated temperature is rarely feasible given the variability in the external climatic data between the simulation model and on-site conditions. Also, variations attributed to non-routine indoor occupancy are difficult to precisely predict and include in the simulation model 38 , 39 . This approach to calibration has been adopted for reliable building performance studies 36 , 37 , 39 , 40 . Figure 5 illustrates the MBE and CV RMSE for the three simulation models being well within recommended favourable limits for calibration. Moreover, the lower error values indicate improved reliability of the simulation results 33 , 35 . MBE and CV RMSE between measured and simulation data are calculated using Eqs. ( 5 ) and ( 6 ):

where m i and s i are measured and simulated data points for i th hour, \(\overline{m}\) is the average of measured data points and N is the total number of data points.

Comparison of simulated and measured temperature data for a representative week-long period in Summer and Winter for the dwellings studied in the three settlements: Figure shows comparison of measured and simulated hourly indoor air temperatures (in °C) for a representative week in winter and summer for the three dwellings to understand how the simulation model has been able to represent the actual indoor operating conditions prevailing in the dwellings. Solid blue line shows the real-time temperature measurements recorded by the loggers, while the dotted orange line shows the simulated data. The simulation models tend to closely imitate real-time operating conditions, suggesting that the models are representative enough to be used for studying the behaviour of the original dwellings.

MBE and CV RMSE between measured and simulated temperature data for the dwellings in the three settlements: Figure shows the Mean Bias Error (MBE) and Coefficient of Variation of Root Mean Square Error (CV RMSE) in percentage calculated between the measured and simulated indoor air temperature data for the dwellings studied in each of the three settlements. The blue coloured solid bar shows MBE, while orange coloured bar with diagonal stripes shows CV RMSE. Both MBE and CV RMSE for all the three settlements are within the limits prescribed by ASHRAE 14 guideline.

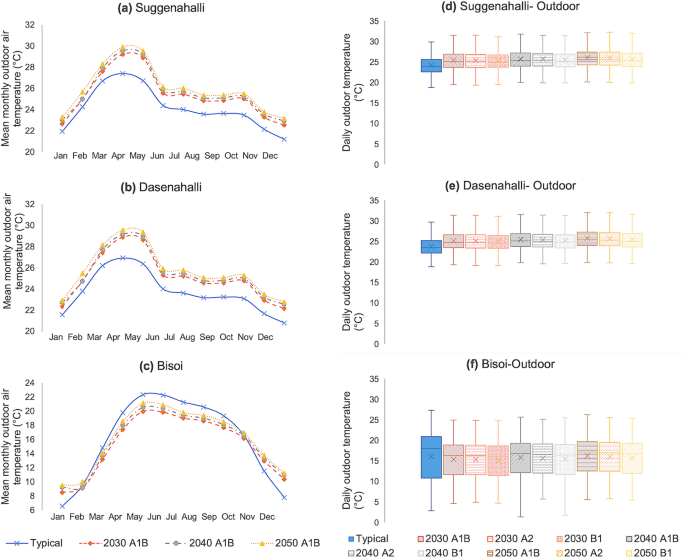

With regards to climate change scenarios, for both Dasenahalli and Suggenahalli, the likely outdoor temperatures are much higher than the prevalent trends for all the three scenarios, with a steady decadal increase (see Fig. 6 a, b, d and e). A1B witnesses the highest increase in temperature across the years while B1 had the lowest. Notably, increase in summer (March–May) temperatures are higher than increase in winter (December–February) temperatures. In Bisoi (Fig. 6 c and f), the prevalent mean monthly temperatures ranging from 6 to 22 °C narrowed to 8–21 °C in the future years, while also registering a decadal increase. Here, while future winter temperatures are likely to increase, summer temperatures are likely to decrease.

( a )–( c ) Mean monthly outdoor air temperatures for typical and A1B scenario for 2030, 2040 and 2050 and ( d ), ( e ) the range of daily outdoor air temperatures for the three settlements for typical scenario and all future scenarios: ( a ), ( b ) and ( c ) shows the mean monthly outdoor air temperature (in °C) for typical scenario and A1B scenario for the years 2030, 2040 and 2050 for the rural settlements Suggenahalli, Dasenahalli and Bisoi, respectively. The same is not shown for A2 and B1 scenarios but they show similar trend with increasing temperatures with each passing decade. ( d ), ( e ) and ( f ) show the range of outdoor air temperatures (in °C) for typical and all three scenarios for future years 2030, 2040 and 2050 for the rural settlements Suggenahalli, Dasenahalli and Bisoi, respectively. The temperatures tend to increase with each decade with the highest increase in A1B scenario and lowest in B1 scenario for both Suggenahalli and Dasenahalli. In case of Bisoi winters tend to get warmer than typical conditions while summers tend to get cooler than typical conditions. The decadal increase in temperature can be witnessed here as well.

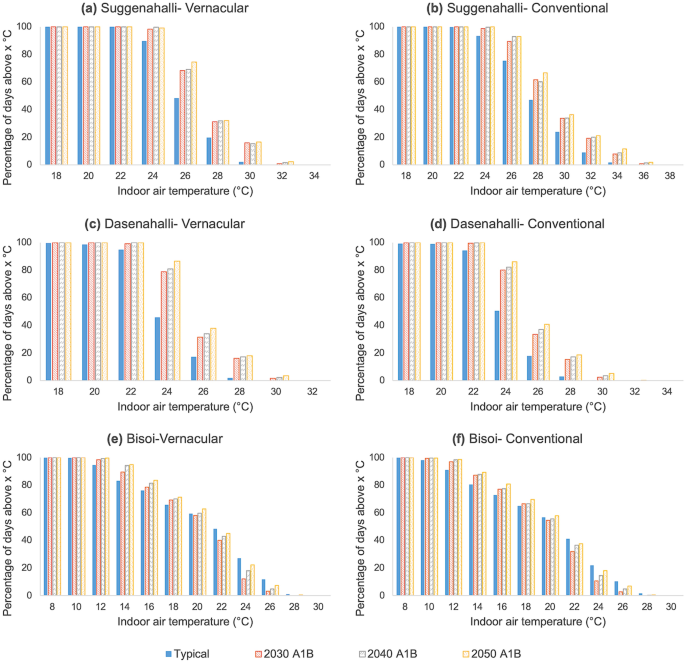

Figure 7 shows daily indoor temperature distribution in the vernacular and conventional dwelling in both typical and future A1B climate scenario for the three cases. The graphs reveal the % days/year with an average daily temperature greater than the value on the abscissa. In the vernacular dwelling in Suggenahalli (Fig. 7 a), climate change tends to increase indoor temperatures in the future. When the indoor temperatures exceeded 30 °C for only 2% of days in a normal year, in 2030, 16% of the days revealed temperature above 30 °C. A similar trend can also be noted in the conventional dwelling (Fig. 7 b). In typical climate the indoor temperatures in conventional dwelling exceeded 30 °C for 24% of the days and 34 °C for 2% of the days. By 2030, indoor temperatures exceeded 30 °C for 34% of the days and 34 °C for 8% of the days. The persistence of higher temperatures in conventional dwelling shows the effect of material transitions. Dasenahalli (Fig. 7 c and d) also shows a similar trend, though the difference between vernacular and conventional dwelling is not as high. In typical climate, average daily indoor temperatures exceed 26 °C, 17% of the days in vernacular dwelling and 18% in conventional dwelling. Climate change does influence the thermal environment in the dwellings and tends to increase the daily indoor temperatures as is evident from the figure. The temperature in both the dwellings does not exceed 32 °C in any case. Bisoi (Fig. 7 e and f) recorded a wider temperature range from 8 to 28 °C. Even though there is a general increase in temperatures due to climate change, at higher temperatures the trend reverses. Future years does not witness an increase in higher temperatures compared to typical climate. The daily indoor temperature in both the dwellings does not exceed 28 °C. Bisoi being in cold climate zone, the concern should be on the persistence of lower temperatures. In vernacular dwelling, temperature falls below 16 °C, 24% of the time in typical climate while in 2030 A1B scenario it falls below 16 °C for 22% of the time. While in conventional dwelling, temperature falls below 16 °C, 13% of the time in typical climate while in 2030 A1B scenario it falls below 16 °C for 23% of the time. Transitions and climate change seem to maintain comfortable temperature range indoors.

Percentage of days above a daily temperature given on abscissa for vernacular and conventional dwelling in the three settlements for typical scenario and future years under A1B scenario: Each bar in the plot shows the percentage of days in a year for which the mean daily indoor air temperature (in °C) is greater than the corresponding temperature (in °C) given on the abscissa. The plot helps to understand the range of temperatures and extent to which those temperatures prevail inside a dwelling throughout the year. This is shown for typical scenario and future years for A1B scenario. ( a ) and ( b ) shows the same for vernacular and conventional dwelling in Suggenahalli, ( c ) and ( d ) for dwellings in Dasenahalli and ( e ) and ( f ) for dwellings in Bisoi. Higher temperatures tend to persist in the dwellings in future years compared to typical conditions especially for conventional dwelling in case of both Suggenahalli and Dasenahalli. This is more evident in Suggenahalli than Dasenahalli. In the case of Bisoi, the frequency of lower temperatures in higher in the future compared to typical conditions, while frequency of higher temperature is higher in typical conditions than future years.

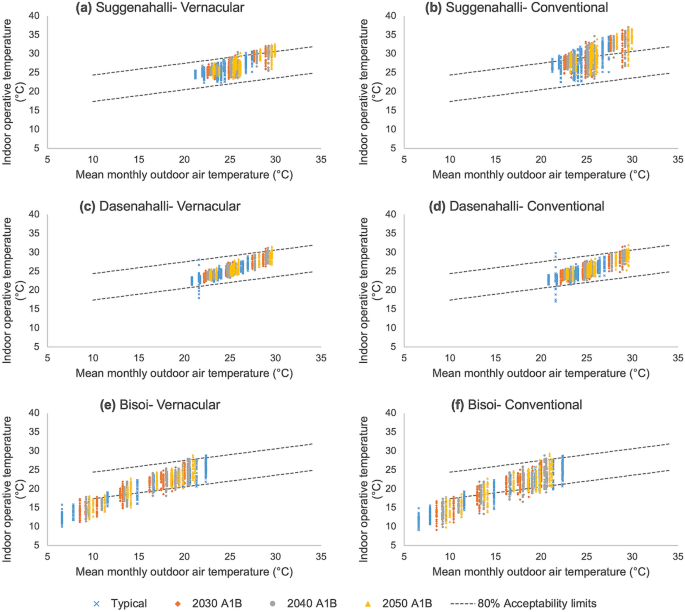

In Fig. 8 , the daily operative temperatures for each dwelling in the three villages are plotted against mean monthly daily temperatures for typical climate and future years for A1B scenario. It also shows the 80% acceptability limits as prescribed by ASHRAE 55. This figure forms the basis for the calculation of ACDD and AHDD. The vernacular dwelling in Suggenahalli (Fig. 8 a) maintains an indoor operative temperature within the acceptability limits for most part of the year for typical climate but exceeds the upper limit for future years at higher outdoor temperatures. On the other hand, the conventional dwelling (Fig. 8 b) fails to maintain indoor temperatures within the acceptability limits for both typical as well as future years for large part of the year. This shows that transitions hugely impact the indoor operative conditions in the dwelling. In the case of Dasenahalli (Fig. 8 c and d), the indoor operative temperatures are maintained within the acceptability limits for both vernacular and conventional dwellings for typical climate and future years. In Bisoi (Fig. 8 e and f), for both the dwellings, the temperatures fall below the lower acceptability limit for a large part of the year for typical climate and future years.

Indoor operative temperature against mean monthly outdoor air temperature for vernacular and conventional dwellings in the three settlements in typical and future climate for A1B scenario: Each plot shows the daily indoor operative temperatures (in °C) inside the dwelling throughout a year plotted against mean outdoor air temperature (in °C) for the corresponding month. The two dotted lines shown in each figure indicates the 80% acceptability limits prescribed by ASHRAE 55 Adaptive thermal comfort model. The points lying within the 80% acceptability limit band are considered to be comfortable by at least 80% of the inhabitants, while those lying outside indicate thermal discomfort. Higher number of points lying outside the band indicate higher discomfort in the given dwelling. Comparing ( a ) and ( b ), conventional dwelling tends to be highly uncomfortable throughout the year for typical as well as future scenarios. Comparing ( c ) and ( d ), there is only marginal difference between vernacular and conventional dwelling in Dasenahalli. Comparing ( e ) and ( f ), though both vernacular and conventional dwelling tend to be uncomfortable at lower outdoor temperatures, vernacular dwelling seems to be warmer than conventional dwelling providing better comfort in cold weather.

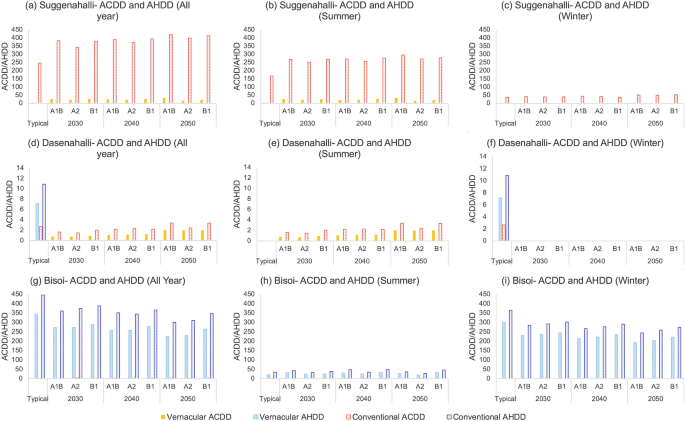

As followed in the comparative evaluation of vernacular buildings under climate change, AHDD and ACDD were computed for the material transitions in dwellings under typical and future (A1B, A2 and B1) climate scenarios. The dwelling in Suggenahalli (Fig. 9 a–c), being in a warm-humid climate zone, do not require any heating throughout the year for all scenarios alike. For the vernacular dwelling, ACDD tend to be quite low in typical climate with small increase in future years. Both climate change and transitions tend to have a serious effect on thermal comfort inside the dwelling in warm-humid climate zone. When the building materials changed from vernacular to modern, ACDD increased from 4 to 246 in typical climate condition (4 to 167 in summer and 0 to 36 in winter). This high difference in degree days between vernacular and conventional dwelling is evident from Fig. 8 a and b shows that a large number of data points lie above the acceptability limit in conventional dwelling compared to vernacular dwelling. Climate change further increased ACDD in the future years with highest increase in A1B scenario and lowest in A2 scenario. Cooling requirement increases considerably due to climate change and transitions especially in summer. In the case of Dasenahalli (Fig. 9 d–f), both AHDD and ACDD are very low in both vernacular and conventional dwelling in typical climate. ACDD is zero in all future years while AHDD, though small, steadily increases in future years, especially for A1B scenario. Transition also affects the thermal comfort in the dwellings where transitions increased both ACDD and AHDD in typical climate, marking an increase in cooling as well as heating demand. In all future years across scenarios, transitions increase ACDD in the dwelling. In Dasenahalli, ACDD and AHDD are not severe enough to require cooling or heating appliances. Bisoi (Fig. 9 g–i) being in cold climate zone, does not require cooling throughout the year for both typical as well as future climatic conditions. The warming climate in Bisoi tend to decrease heating demand in the dwelling in both vernacular and conventional dwelling. Transitions have an adverse effect on the thermal comfort in the dwelling as it increases heating demand in the dwelling by an average of 25% compared to the vernacular dwelling in winter. This shows the effectiveness of insulation provided by the timber walls and the timber and slate roofing in vernacular dwelling over conventional materials.

All year, summer and winter AHDD and ACDD for the dwellings in the three villages for typical and future climate scenarios: Each plot depicts the Adaptive heating degree days (AHDD) and Adaptive cooling degree days (ACDD) calculated for vernacular and conventional dwelling for typical scenario and future years 2030, 2040 and 2050 for A1B, A2 and B1 scenarios. Plots from left to right shows typical and future ACDD and AHDD calculated for the entire year, for summer and winter for each rural settlement for both vernacular and conventional dwelling. From ( a ), ( b ) and ( c ) conventional dwelling in Suggenahalli tend to demand active cooling for most part of the year compared to vernacular dwelling. In case of Dasenahalli ( d ), ( e ) and ( f ), it can be seen that demand for heating or cooling is fairly low, cooling demand is slightly higher in conventional dwelling. From ( g ), ( h ) and ( i ), heating demand is high in both dwellings in Bisoi, especially in winter, with heating demand higher in conventional dwelling than vernacular dwelling.

The study investigated the effect of climate change and material transitions (replacing local traditional materials with conventional materials) on vernacular dwellings in three villages in India across three different climate zones. The impact of climate change on the dwellings were examined for the years 2030, 2040 and 2050 under the IPCC SRES scenarios A1B, A2 and B1 and compared with typical climate which is an average of 20 years of recorded weather data. In both Suggenahalli and Dasenahalli, climate change increased the outdoor temperatures throughout the year affecting the indoor environment as well. The effect of climate change was more pronounced in the case of Suggenahalli located in warm-humid climate zone, making the indoors warmer than the typical, climate demanding the use of cooling appliances. Due to climate change, winter outdoor temperatures increased while summer temperatures decreased in Bisoi. Summer temperatures can be expected to increase further in the second half of the century. Climate change has helped increase indoor temperatures which reduced heating demand in the dwellings. In warm climates, A1B scenario had the worst impact on the weather and the indoor temperatures, while B1 scenario which was a low emission scenario had comparatively lower impact on the temperatures. On the other hand, in cold climates A1B helped reduce the heating demand much better than A2 and B1 scenarios.

For both Suggenahalli and Dasenahalli, the vernacular dwelling maintained comfortable indoor operating conditions for most part of the year. The conventional dwelling in Dasenahalli also was able to maintain comfortable indoor conditions. Transitions in Suggenahalli led to warmer indoor environment pushing it beyond the acceptability limits. In case of Bisoi, indoor temperatures fall below acceptability limit for both vernacular and conventional dwelling. The thermal insulation provided by the traditional materials in the vernacular dwelling helped it to perform better than the conventional dwelling in maintaining warmer indoors. Vernacular dwellings seem to perform better than the conventional dwellings in all the three cases for typical as well as future climate. Conventional dwelling that replaced the traditional materials with modern materials failed to adequately respond to changes in climate, compromising indoor thermal comfort and necessitating dependence on active space conditioning.

Modern material transitions in dwellings compromised the thermal comfort in the dwellings across all climate zones, though the effect was not severe in Temperate climate as it was in Warm-humid and Cold climates. Climate change further exasperated the thermal comfort in dwellings in warm climates but seemed favourable in cold climates. The study helps to verify the climate-resilience of vernacular dwellings to perform in the context of much imminent climate change and shows that modern dwellings constructed using modern industry manufactured materials, to meet the modern aspirations of inhabitants may not perform in the event of climate change. This confirms the need for reinterpretation in design of houses that meet the modern aspirations of the people and perform in the future climate scenarios. The study indicates that vernacular dwellings hold key answers in the direction of mitigation and adaptation strategies in response to climate change and advocates designers to understand the present and future climatic conditions and future demands in the local context, to appreciate and scientifically validate traditional wisdom while designing buildings for the future. Designers must ensure that the dwellings they construct not only meet the aspirations of the modern inhabitant but also perform under future climatic pressures.

Limitations of the study and scope for future work

A country like India is home to diverse vernacular architecture which varies with climate, culture, customs, and available resources. This paper studies three rural settlements with unique vernacular architecture and evident transitions in three different climate zones in India. The authors have selected the settlements such that the vernacular architecture is representative of the climate zone they are in. Inclusion of more case studies and other climate zones would increase the scope of the paper and present a better estimate on the nature of transitions and their ramifications on resource and energy requirement and vulnerabilities to climate change. The current study is a step in this direction and is also a methodological contribution for such studies, tested for three diverse settlements. The selection of settlements for the study was difficult as it required a combination of both vernacular and modern dwellings and those that are in transition. Overcoming scepticism of villagers and gaining their trust was an important requirement to ensure the corporation of the villagers as the study extended for more than a year in each of the villages. Extending this study to cover the diversity of habitations in India, would require networking with local academic institutions, a larger group and a longer time to identify appropriate interventions/mitigation measures in response to climate change.

Understanding the contribution of each stage of transition on the thermal performance of the dwelling is also important to identify critical stages of transition and adopt preventive or adaptive strategies to improve thermal comfort in the dwelling without compromising the requirements of the inhabitants. Future work will involve investigation of individual stages of transitions and their effects on thermal comfort in the dwelling to assess the contribution of each transition on the performance of the dwellings. The study could subsequently evolve into regional building codes and recommendations for interventions in response to climate change, and the revalidation of vernacular building typologies for their relevance in the modern world. Further, the study could promote dependence on local decentralized circular economies that rely on local resources and skill, thereby lowering the global carbon footprint.

The current study is limited to understanding the thermal performance of the dwellings to changing climate. Studies have reported increased discomfort among occupants due to transitions 20 , 21 as well as climate change 2 . The response of the occupants to changing climate and performance of dwellings should shed light on possible adaptation strategies since rural population tend to be proactive in responding to change. Research reveals increased dependence on electro-mechanical equipment for thermal comfort, clothing adjustments and window operation as some of the major adaptation strategies 41 , 42 . Future work should aim to explore adaptation and mitigation strategies adopted in form, materials, or surface treatments in the dwelling elements and in clothing, window operation and use of spaces by the occupants.

However, understanding how people are going to change as climate warms, would involve intergenerational attitude and physiological studies, as current forecasts rely on thermal comfort responses valid for the current (adult) generation. Attitude is a critical determinant of sustainablity in human settlements and determines how the built environment evolves, with forcasting models relying on current generation attitudes 45 . In 2050, the present-day infants and youth would be the adults responsible for affecting changes or responses to climate change vulnerabilities. Given the diversity in ethnicity and other physiological differences, such studies on human exposure to climatic variations are extremely challenging in providing the causal basis required for forecasting 43 , 44 .

Global Alliance for Buildings and Construction, International Energy Agency & United Nations Environment Programme. 2019 Global status report for buildings and construction: Towards a zero-emissions, efficient and resilient buildings and construction sector . (2019). ISBN No: 978-92-807-3768-4

de Wilde, P. & Coley, D. The implications of a changing climate for buildings. Build. Environ. 55 , 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2012.03.014 (2012).

Article ADS Google Scholar

IEA. Transition to sustainable buildings: Strategies and opportunities to 2050 . (2013). ISBN: 978-92-64-20241-2

GEA. Chapter 10. Energy end-use Buildings, in Global energy assessment toward a sustainable future (eds. Johansson, T. B., Patwardhan, A., Nakicenovic, N. & Gomez-Echeverri, L.) 649–760 (Cambridge University Press and International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, 2012). ISBN: 97805211829355

US Energy Information Administration. International Energy Outlook 2019 with projections to 2050 . (2019). www.eia.gov/ieo . Accessed on 22-04-2020

The World Bank. World Bank Open Data . (2018). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.RUR.TOTL.ZS last accessed on 12-02-2021

Anandan, M. & Sankaravelu, R. Energy Uses in India: A Case of Electricity. Int. J. Res. Commer. IT Manag. 3, 27–33 (2013). ISSN 2231–57568

Chandran, K. M., Balaji, N. C. & Mani, M. Understanding transitions in a rural Indian building typology in the context of well-being. Curr. Sci. 109 , 1610–1621. https://doi.org/10.18520/v109/i9/1610-1621 (2015).

Article Google Scholar

Laurie Baker Centre for Habitat Studies. Housing conditions in India: With special focus on rural areas and socially disadvantaged sections . I, (2014).

Prayas (Energy Group). Residential electricity consumption in India : What do we know? (2016).

Henna, K., Saifudeen, A. & Mani, M. Responsiveness and resilience of existing dwellings in warm-humid climate zone to changing climate. in Proc. 1st Int. Conf. Comf. Extrem. Energy, Econ. Clim. (ed. Finlayson, S. R. and W.) 758–773 (2019).

Li, D. H. W., Yang, L. & Lam, J. C. Impact of climate change on energy use in the built environment in different climate zones—A review. Energy 42 , 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2012.03.044 (2012).

Wang, H. & Chen, Q. Impact of climate change heating and cooling energy use in buildings in the United States. Energy Build. 82 , 428–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2014.07.034 (2014).

Karimpour, M., Belusko, M., Xing, K., Boland, J. & Bruno, F. Impact of climate change on the design of energy efficient residential building envelopes. Energy Build. 87 , 142–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2014.10.064 (2015).

Huang, J. & Gurney, K. R. The variation of climate change impact on building energy consumption to building type and spatiotemporal scale. Energy 111 , 137–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2016.05.118 (2016).

Mani, M., Dayal, A. & Chattopadhyay, R. N. An Assessment into the sustainability of earthen structures and modern transitions, in International symposium on earthen structures , pp. 22–24 (2007).

Singh, M. K., Mahapatra, S. & Atreya, S. K. Bioclimatism and vernacular architecture of north-east India. Build. Environ. 44 , 878–888. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2008.06.008 (2009).

Shastry, V., Mani, M. & Tenorio, R. Evaluating thermal comfort and building climatic response in warm-humid climates for vernacular dwellings in Suggenhalli (India). Archit. Sci. Rev. 59 , 12–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/00038628.2014.971701 (2016).

Praseeda, K. I., Mani, M. & Reddy, B. V. V. Assessing impact of material transition and thermal comfort models on embodied and operational energy in vernacular dwellings (India). Energy Procedia 54 , 342–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2014.07.277 (2014).

Dili, A. S., Naseer, M. A. & Varghese, T. Z. Thermal comfort study of Kerala traditional residential buildings based on questionnaire survey among occupants of traditional and modern buildings. Energy Build. 42 , 2139–2150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2010.07.004 (2010).

Shastry, V., Mani, M. & Tenorio, R. Impacts of modern transitions on thermal Comfort in vernacular dwellings in warm-humid climate of Sugganahalli (India). Indoor Built Environ. 23 , 543–564. https://doi.org/10.1177/1420326X12461801 (2014).

Bureau of Indian Standards. National Building Code of India 2005 . 883 (Bureau of Indian Standards, 2005).

Brager, G. S. & de Dear, R. J. Thermal adaptation in the built environment : a literature review. Energy Build. 27 , 83–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-7788(97)00053-4 (1998).

Crawley, D. B. et al. EnergyPlus: Creating a new-generation building energy simulation program. Energy Build. 33 , 319–331 (2001).

Meteotest. Meteonorm Handbook part I : Software version 7.3.4. (2020).

IPCC. Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working groups I, II and III to the fourth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change . [Core Writing Team, Pachauri, R.K. and Reisinger, A. (eds.)] (IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 2007). ISBN 92-9169-122-4

Mani, M. & Reddy, B. V. V. Sustainability in human settlements: Imminent material and energy challenges for buildings in India. J. Indian Inst. Sci. 92 , 145–162 (2012).

Google Scholar

Belz, M. M. Unconscious landscapes: Identifying with a changing vernacular in Kinnaur, Himachal Pradesh. Mater. Cult. 45, 1–27 (2013). http://www.jstor.org/stable/24397619 Last accessed: 03-11-2017.

ASHRAE. Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy . (2010). ISSN 1041-2336

de Dear, R. J. & Brager, G. S. Developing an adaptive model of thermal comfort and preference. ASHRAE Trans. 104 , 1–18 (1998).

de Dear, R. J. & Brager, G. S. Thermal comfort in naturally ventilated buildings : revisions to ASHRAE Standard 55. Energy Build. 34 , 549–561. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-7788(02)00005-1 (2002).

de Dear, R. Adaptive comfort applications in Australia and impacts on building energy consumption. in IAQVEC 2007 Proceedings of the 6th international conference on indoor air quality, ventilation and energy conservation in buildings: sustainable built environment 2, 1–8 (2007).

ASHRAE. ASHRAE Guideline 14: Measurement of Energy and Demand Savings . (2002). ISSN 1049-894X

Coakley, D., Raftery, P. & Keane, M. A review of methods to match building energy simulation models to measured data. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 37 , 123–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2014.05.007 (2014).

Allesina, G., Mussatti, E., Ferrari, F. & Muscio, A. A calibration methodology for building dynamic models based on data collected through survey and billings. Energy Build. 158 , 406–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2017.09.089 (2018).

Royapoor, M. & Roskilly, T. Building model calibration using energy and environmental data. Energy Build. 94 , 109–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2015.02.050 (2015).

Carlander, J., Trygg, K. & Moshfegh, B. Integration of measurements and time diaries as complementary measures to improve resolution of BES. Energies 12 , 2072. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12112072 (2019).

Hoes, P., Hensen, J. L. M., Loomans, M. G. L. C., de Vries, B. & Bourgeois, D. User behavior in whole building simulation. Energy Build. 41 , 295–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2008.09.008 (2009).

Qiu, S., Li, Z., Pang, Z., Zhang, W. & Li, Z. A quick auto-calibration approach based on normative energy models. Energy Build. 172 , 35–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2018.04.053 (2018).

Ruiz, G. R. & Bandera, C. F. Validation of calibrated energy models: Common errors. Energies 10 , 1587. https://doi.org/10.3390/en10101587 (2017).

Bonte, M., Thellier, F. & Lartigue, B. Impact of occupant’s actions on energy building performance and thermal sensation. Energy Build. 76 , 219–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2014.02.068 (2014).

Chen, S. et al. Effect of inhabitant behavioral responses on adaptive thermal comfort under hot summer and cold winter climate in China. Build. Environ. 168 , 106492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2019.106492 (2020).

Evans, G. W. Projected behavioral impacts of global climate change. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 70 , 449–474. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-103023 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Schweiker, M., Huebner, G. M., Kingma, B. R. M., Kramer, R. & Pallubinsky, H. Drivers of diversity in human thermal perception—A review for holistic comfort models. Temperature 5 , 308–342. https://doi.org/10.1080/23328940.2018.1534490 (2018).

Mani, M., Varghese, K. & Ganesh, L.S. Integrated model framework to simulate sustainability of human settlements. ASCE J. of Urban Planning and Development, 131 (3), 147–158 (2005)

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank the Centre for Sustainable Technologies, Indian Institute of Science for providing the unwavering academic support and freedom to purse this valuable research. The current work has relied on and continued the sustained research by our SuDesi (Sustainability and Design) Lab in studying diverse building typologies. Thanks also to the SPARC (Scheme for Promotion of Academic and Research Collaboration) initiative, which has been instrumental in our access to the dwellings in Bisoi.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centre for Sustainable Technologies, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, India

Khadeeja Henna, Aysha Saifudeen & Monto Mani

Department of Architecture, College of Engineering Trivandrum, Thiruvananthapuram, India

Aysha Saifudeen

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

K.H., A.S., M.M., All authors were part of the conception of the paper, data collection, and real-time monitoring of the houses. K.H. and A.S. built the simulation models. K.H. performed the simulation, calibration, and analysis. K.H. wrote the main manuscript and prepared the figures and tables. M.M. further edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Monto Mani .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Henna, K., Saifudeen, A. & Mani, M. Resilience of vernacular and modernising dwellings in three climatic zones to climate change. Sci Rep 11 , 9172 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-87772-0

Download citation

Received : 08 October 2020

Accepted : 22 February 2021

Published : 28 April 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-87772-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Vernacular architecture of Kerala in modern world: A way to sustainable development

Main article content, article sidebar.

Kerala is a land of diverse cultures, traditions and art forms. Each art form has its own significance that represents the style of the specific region and culture. Many of the traditional art forms are going unappreciated and are declining. The revival of these art forms demands an infrastructure that creates an atmosphere reminiscent of Kerala’s traditional spaces, which helps to provide better awareness and visual experience for the spectator.

As an impact of globalisation, Kerala was influenced by various cultures around the world, which brought in changes to the traditional architecture of Kerala that had evolved over years. The changes in the build structures led to climatic changes and issues like global warming. It was not solely about the climatic and environmental issues, but also about the loss of the culture and identity of the state. These issues need to be addressed at the earliest, and this calls for the revival of traditional Kerala architecture in the modern world. The traditional Kerala architecture is unique, here the buildings are shaped by the region. These climate responsive buildings that evolved over time needs to be studied to understand how sustainability was the basic guideline for design process. The traditional way of planning spaces created healthier environment, people and community.

The proposed cultural performance centre in Kerala aims to bring back the traditional Kerala architecture for addressing various sustainability issues faced by the current era. The integration of these structures with the native Kerala landscape creates good quality outdoor and indoor environment.

Through the case study, the research focuses on sustainability potential of vernacular architecture of Kerala, and how the principles and strategies for sustainable development could be drawn from vernacular heritage and be integrated into structures of the present society. The research examines how the sustainable development goals were contained in the vernacular structures in Kerala and how the globalisation brought in changes to the architectural styles which in turn affected the environment, socio economic, and socio-cultural characters of the society.

The integration of traditional architectural principles and techniques of designing could be solutions to many sustainable development goals that include good health and well-being (SDG3), affordable energy by using passive methods (SDG 7), climate action (SDG 13) and create sustainable cities and communities (SDG11). The revival of the traditional architecture could make a change in the way of addressing sustainability issues that emerged as the result of globalisation over the years and it could help in creating sustainable and healthy communities.

How to Cite

Article details, most read articles by the same author(s).