- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Empirical study article, attitudes towards school violence based on aporophobia. a qualitative study.

- 1 Department of Socio-Health Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of Murcia, Murcia, Spain

- 2 Applied Psychology Service, University of Murcia, Murcia, Spain

- 3 Department of Psychology, Universidad Europea de Valencia, Valencia, Spain

- 4 Department of Psychiatry and Social Psychology, Faculty of Psychology, University of Murcia, Murcia, Spain

School violence is a worldwide problem. Among the variables that influence its frequency, perceived socioeconomic status seems to be associated with a higher risk of exposure to violence and attitudes toward violence. The aim of this study is to examine attitudes toward violence based on socioeconomic discrimination (aporophobia) and its relationship with violent behaviors in the school context. For this purpose, 96 Spanish students of Primary Education (PE) and Compulsory Secondary Education (CSE) participated in this qualitative study through focus groups and thematic analysis. The results identified three types of attitudes toward violence directed toward those who are perceived as members of a lower status. The attitudes observed are related to self-esteem or feeling better, legitimization and socialization.

Introduction

Whether inside the school classroom or outside of it, in the surroundings of the school or even online, school violence remains a worldwide problem of difficult solution ( UNESCO, 2017 ). Several variables influence the occurrence of this phenomenon, among which impulsivity, empathy, attitudes toward violence, self-efficacy, anxiety, depression, substance abuse or parenting styles, among others, have been studied ( Varela et al., 2018 ; Álvarez-García et al., 2018 ; Ruiz-Hernández et al., 2019 ). In this regard, attitudes toward violence have been shown to be a variable closely related to school violence, as well as to the improvement of school climate in general terms ( Jiménez-Barbero et al., 2016 ; Fraguas et al., 2021 ). This attitude-violent behavior relationship in the school context has enough evidence that attitudes can be considered a predictor of behavior ( Kraus, 1995 ; Pina et al., 2022 ).

Schools are not immune to the cultural influence of the context. Along these lines, several factors have been considered risk factors for being a victim of school violence. For example, the stigma-based framework of violence ( Earnshaw et al., 2018 ) frames the complexities of violent behaviors in social stigmas. These stigmas cause the social devaluation of certain characteristics or identities, structural biases that are reproduced in policy, law, or cultural beliefs. In this way, stigmas, often influenced by social dominance orientation, stereotypes and prejudices, have an impact on interpersonal interactions ( Ho et al., 2012 ; Malecki et al., 2020 ). Thus, social, structural (e.g., school or family) and individual characteristics of youth interact to create conditions conducive or not conducive to bullying behaviors, especially when a traditionally stigmatized characteristic is at stake ( Malecki et al., 2020 ). In this framework, several variables such as poverty level, racial or ethnic identity, being part of the LGBTQ + community, or disability status have been studied ( Malecki et al., 2020 ).

Within the group of variables that influence the interpersonal interactions of minors, the socioeconomic status (SES) perceived by the group is a variable of interest. SES refers to the position a person occupies in the structure of society due to social or economic factors ( Galobardes et al., 2006a ). Some variables related to family socioeconomic status are the education of both parents (both as a quantitative measure, where the more years of study, the better the socioeconomic status; and as a categorical measure, focused on specific achievements, where the more successful the studies, the better the socioeconomic status), parental occupation (e.g., parental unemployment is a strong indicator of low socioeconomic status), household income (e.g., family affluence, annual household income and combined income of both parents) and household conditions (e.g., overcrowding, considered if the threshold of two or more persons per room is exceeded; and household conditions, considered by the presence of humidity and condensation, construction materials, rooms of the dwelling) ( Galobardes et al., 2006a , b ).

In general terms, a higher incidence of bullying problems has been observed in schools in disadvantaged areas ( Olweus, 1993 ; Woods and Wolke, 2004 ; Fu et al., 2013 ), with an Odds Ratio of 0.46 ( Woods and Wolke, 2004 ). Of all the family SES indicators, a strong association is reported between low parental educational level and child victimization ( Jansen et al., 2012 ). Similarly, there seems to be a relationship between the SES and the role assumed in a situation of violence ( Tippett and Wolke, 2014 ). Throughout the literature, it is observed that children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds may act as perpetrators, bullying their peers more often, or be more vulnerable to victimization ( Alikasifoglu et al., 2007 ; Due et al., 2009a , b ; Wolke et al., 2010 ; Jansen et al., 2011 ). Specifically, in the meta-analysis conducted by Tippett and Wolke (2014) concluded that being a victim of bullying was positively associated with low family socioeconomic status, highlighting the influence of factors such as economic disadvantage ( Bowes et al., 2009 ; Lumeng et al., 2010 ) and poverty ( Glew et al., 2005 ). Specifically, it appears that coming from a lower socioeconomic background or being unable to afford the goods or resources available to other peers may expose children to peer victimization ( Tippett and Wolke, 2014 ).

In general terms, the data suggest that children living in low-income households should make a greater effort to avoid becoming involved in violence, although there are discrepancies in the literature in this regard. An example of this is reflected in the qualitative studies by Daly and Leonard (2002 , p. 12) and Davis and Ridge (1997 , p. 64). For some of the minors in these studies, not following or not being able to follow fashion trends was met with verbal abuse, teasing, or bullying from others. Likewise, economic disparity between schools is associated with an increased likelihood of being exposed to bullying ( Due et al., 2009b ). Higher rates of school violence have been observed in countries where social inequality is greater ( Due et al., 2009b ; Elgar et al., 2009 ). For this reason, it has been pointed out that the relationship between family socioeconomic status and bullying might be better understood at the societal level than at the individual level ( Tippett and Wolke, 2014 ).

From this social perspective, discrimination against those members of the community who have fewer resources has been associated with the term aporophobia, defined for the first time in our context by Cortina (1995) . Although initially this term did not appear in Spanish language dictionaries ( Cortina, 2000 ; Martínez, 2002 ), it is now accepted by the Royal Spanish Academy, who defines it as “exaggerated aversion to poor or disadvantaged people” ( Pozo-Enciso and Arbieto-Mamani, 2020 ). Thus, aporophobia refers to the feeling of rejection or fear of the poor, the underprivileged, those who lack outlets, means or resources, thus blaming them for the situation in which they find themselves ( Andrade, 2008 ). Likewise, such discomfort seems to be an induced and provoked sensation that is learned and disseminated through alarmist and sensationalist stories that show poor people as responsible for crime and as an alleged threat to the stability of the socioeconomic system ( Martínez, 2002 ).

The roots of aporophobic thinking are found in Smith’s (1976) Theory of Moral Sentiments. Smith makes use of the concept of “sympathy” to explain why poor people arouse negative emotions. The observer determines the sympathy or antipathy response to another person’s emotions by allowing the observer to imagine oneself in the other’s position in an effort to understand why one is in the same situation as the other person and, thus, understand why one feels a certain way which, from an economic point of view, translates into feeling greater sympathy for rich people because of their greater association with happiness ( Bakke, 2011 ). In turn, the observer feels discomfort at the pain of others, so they sympathize to some extent ( Smith, 1976 ). For this reason, if someone who is poor asks for more compassion than the impartial spectator justifies, the observer ends up resenting the poor person and inducing them to enter fully into their hardship being able to justify this in the non-dissimulation of their painful situations, making them appear pathetic and despicable to others ( Smith, 1976 ; Bakke, 2011 ). Following Smith’s (1976) proposal, poor people are perceived as useless, lazy, lacking talent, let alone the ability to earn a living. In cases of extreme poverty or destitution, the very situation of hunger, physical pain, and emotional depression of the poor person is naturally repulsive to the observer and, therefore, compassionately impenetrable. Conversely, the poor person come to resent the observer for not considering the full reality of their situation. According to this author, the fear and disgust felt toward the poor person and the admiration for the rich and powerful one would be human in nature, in a way that it could not be manipulated or altered, since it is not only a way of preserving our moral sentiments, but is also necessary to establish and maintain the distinction of ranks and the order of society.

Based on the conceptualization of the phenomenon by Smith (1976) , Cortina (2000) , Martínez (2002) , and Bakke (2011) , different psychological categories such as attitudes, beliefs and behaviors are associated with the concept of aporophobia ( Comim et al., 2020 ). Likewise, the concept of aporophobia is closely related to other widely studied social problems such as gender-based violence, hate crimes, racism, ethnic discrimination, xenophobia, and homophobia, with SES inequality being the common factor that could serve as a link between many of these ( Pozo-Enciso and Arbieto-Mamani, 2020 ). According to some authors, such discriminatory behaviors are mainly explained by perceived SES inequalities, regardless of other conditions such as race, ethnicity, religion, politics, or sexual orientation ( Cortina, 1996 ; Andrade, 2008 ; p. 70; Pozo-Enciso and Arbieto-Mamani, 2020 ). In this regard, poverty would be the common and precipitating factor of this type of social problems, understanding poverty as deprivation and inequality attributed to a sector ( Pozo-Enciso and Arbieto-Mamani, 2020 ). From the aporophobic logic, “poor” people have nothing to offer, making their presence uncomfortable because it reminds us that situations of homelessness are, to some extent, a responsibility of people who are well off and this, possibly, is wanted to be forgotten ( Andrade, 2008 ). Thus, it is not usually taken into consideration that “poor” people are not only “poor” because of their insufficient purchasing power of goods, but that they are also immersed within a complex network of socioeconomic, environmental and cultural conditions defined by the society to which they belong ( Ardiles, 2008 ).

Under this prism, aporophobia would translate into violent behaviors with a high prevalence. In this sense, the Network of Support for Social and Labor Integration ( RAIS fundación, 2017 ) indicates that, in the specific case of Spain, 47% of people in poverty have been victims of at least one hate crime due to aporophobia. Aporophobia as a psychological and social pathology has not been studied in depth despite the fact that its definition and the arguments that define it are quite clear ( Pozo-Enciso and Arbieto-Mamani, 2020 ). This lack of evidence carries over to the school context. Although poverty has been studied as a risk factor in school violence, there does not seem to be any study that delves into the problem from the point of view of aporophobia in the school context, especially through qualitative methodology. This vision is necessary since the interest is not to know the relationship between SES and aggressive behaviors and/or victimization, but from the point of view of aporophobia as a social pathology, the interest of study are the attitudes and violent behaviors directed toward those members of the community who are perceived as “poor” or of a lower status. Along these lines, qualitative indicators will vary according to the particular social context where the study of the same is conducted ( Pozo-Enciso and Arbieto-Mamani, 2020 ). Under this premise, the objectives of this study are, on the one hand, to identify attitudes toward school violence based on aporophobic discrimination using qualitative techniques in schoolchildren. In addition, behaviors associated with these attitudes will be explored. On the other hand, a theoretical approach to the structure and dynamics that seem to maintain and justify these attitudes in the school context is intended.

Participant recruitment

For this study, a qualitative design was used with participants from three schools in southeastern Spain, two of Primary Education (PE) and one of them of Compulsory Secondary Education (CSE). The socioeconomic status of the areas of the schools included in this study is medium. The schools were selected incidentally. The census of these schools was high ( M = 663.33, SD = 458.29, range between 240 and 1,150). From among the students at the school, those enrolled between the fourth and sixth year of PE (9–11 years) and first and fourth year of CSE (12–16 years) were invited to participate. The target sample size was 90–120 students, obtaining a final sample of 96 participants. The mean age of the interviewees was 11.35 (SD = 2.09) with an age range between 9 and 16 years old. A total of 95.8% were born in Spain and 83.5% had a remarkable or outstanding academic performance. A large number of students had a high school diploma. A large number of students had at least one sibling (82.3%) and lived with both parents (86.5%). Regarding the educational level of the parents, in both cases it was more common for them to have basic or compulsory studies (35.4 and 35.4%). No other measures of socioeconomic level were taken because of the difficulties that children have in estimating these indicators ( Wardle et al., 2002 ). More information on the participants is available in the study by Pina et al. (2021a) .

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the authors’ university (ID: 2317/2019) and followed the recommendations of the COREQ guide for focus groups ( Tong et al., 2007 ). The selection of schools for the study was incidental, excluding those that, according to the data from the Observatory of School Coexistence of the Autonomous Community, had extremely low or high rates of school violence. Of the four schools initially invited, three finally participated, since one of them was unable to participate for reasons related to COVID-19.

All the students, teachers and parents/legal guardians belonging to the classrooms selected for the study were provided with written information together with informed consents about the objectives of the study. In these documents, they were asked to accept both the audio recordings in the focus groups and the publication of the data obtained in subsequent scientific publications.

For the creation of the groups, a maximum of four participants per classroom were randomly selected, with the common nexus of the groups being the school year. A total of 12 focus groups were conducted, with an average of eight participants and lasting between 41.5 and 54.47 min ( M = 48.85, SD = 4.89). Of all the minors invited, only 10 of them declined to participate in the research.

The inclusion criteria for being part of these groups were as follows: (a) being enrolled in one of the selected schools, (b) being between 9 and 16 years old, and (c) speaking and understanding Spanish. Meanwhile, the exclusion criteria were: (a) being enrolled in a grade lower than fourth year of PE or higher than fourth year of CSE, (b) refusing to participate or not submitting the informed consent signed by the minor and parents/guardians, (c) showing some type of cognitive limitation that prevented participation in the study, and (d) not attending the school on the day the focus groups were conducted.

All the group interviews were conducted during school hours. A member of the school management team accompanied the children from their classroom to a space specially prepared for the focus groups. Only the children and the interviewers were present in these spaces. Before starting the recording, the participants were again asked for their explicit consent, this time verbally. In addition, they were reminded that the audio recording would be destroyed after transcription. In the text file, any data provided that could identify the participant or another person was replaced by a code.

Data collection

For the exploration of aporophobia, focus group discussions were used following the methodology proposed by Krueger (1991) . These focus groups involve a data collection technique, of a qualitative nature employed on numerous occasions in research (e.g., Edwards et al., 2020 ; Miranda Miranda et al., 2020 ; Pina et al., 2021b ). For their formation, people with common characteristics that are relevant to the research topic are grouped together, in our case, minors from the same school and course. Prior to conducting the focus groups, a script was created in which general statements related to the topic of the study were generated. It was decided to opt for the study of attitudes toward aporophobia in the school context given the scarcity of qualitative research published with this approach. This script was previously tested on a pilot group of students not contemplated in the results of the study.

The focus groups were conducted by the first author with the assistance of the other authors. This first author is a male with extensive training and experience in focus groups, having published several studies using this methodology. There was no previous relationship with the participants in the groups. Before starting with the recordings, the interviewer spent between 5- and 10-min generating rapport with the participants, with questions outside the object of study and of trivial subject matter. Once this was done, about the objectives, functions and importance of the study of coexistence in the academic environment were explained.

The interviewer tried to remain neutral throughout the process, remaining free of bias, assumptions, or displays of interest in the participants’ responses. The rest of the authors of the study took notes and supplemented the interviews whenever necessary. Likewise, the interviewees were encouraged to provide as much information as possible, whether it was their own or an experience from a colleague or acquaintance, and to avoid focusing exclusively on their own experiences. More information on the questions is available in the study by Pina et al. (2021a) .

Data analysis

The data of this study were analyzed through a thematic analysis following the proposal of Braun and Clarke (2006) , assuming a constructivist and inductive approach. Once the focus groups were conducted, with the aim of identifying and describing certain patterns in the data, the transcriptions of the recordings were carried out as a first contact with these data. Following this method, the data should be transcribed with the supervision of a minimum of two researchers, taking notes and ideas that could be relevant to consider in later phases of the study. Once this was done, codes were generated using an inductive or bottom-up method, starting from the virgin data without the intention of framing them in an existing theoretical framework. These codes were subsequently discussed by all the authors of the study, divided into pairs, and, if no consensus was reached, multiple coding was carried out.

The codes generated were grouped into topics and subtopics, with the researchers relying on maps and tables for better visual representation, thus discarding codes irrelevant to the research. For the proper construction of topics, we chose to follow a constructivist perspective, exploring latent topics in the information collected and avoiding the simple description of data.

Once these steps were completed, it was decided to go back in the process to review the codes, adjusting them as necessary and thus ensuring congruence with the data collected. Finally, for a topic to be considered, it had to be present in a minimum of four focus groups, except for information considered very important by most of the researchers. After this definition, all the information was structured using a conceptual map.

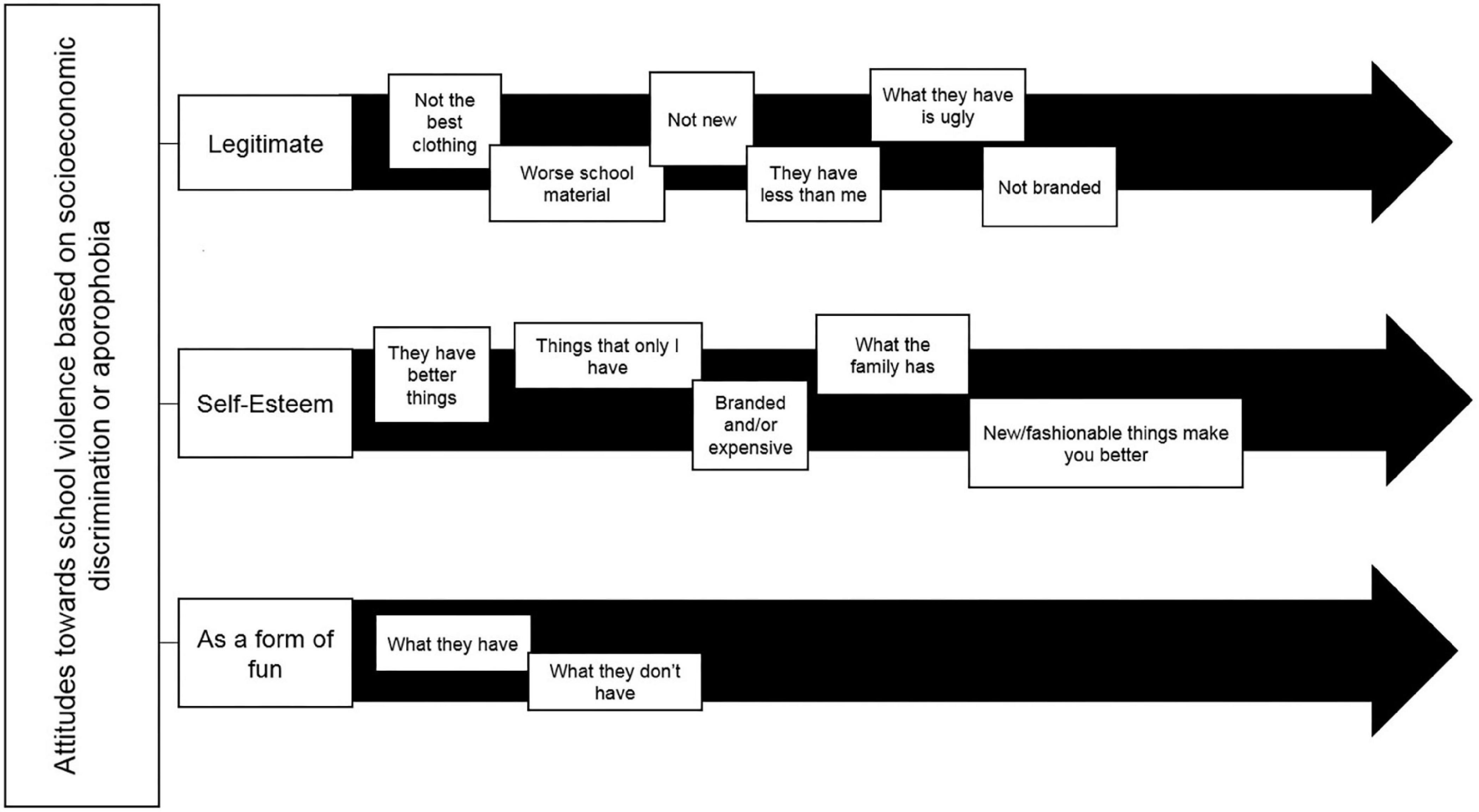

The thematic analysis applied to the various focus groups identified three interrelated blocks of attitudes toward violence based on socioeconomic discrimination or aporophobia. Due to the complexity of their interactions, the information is presented separately. The extracted topics were titled as attitudes toward violence based on aporophobia (a) to feel better or increase self-esteem, (b) perceived as legitimate, and (c) as a way of socializing. Each of these blocks are divided into subtopics that elaborate on each of these attitudes ( Figure 1 ).

Figure 1. Attitudes toward school violence based on socioeconomic discrimination or aporophobia.

Attitudes toward aporophobic violence in school to feel better

In the different focus groups, it was observed that attitudes toward violence based on aporophobia are strongly related to the need to feel better about oneself, whether the objective is to increase one’s self-esteem or to have fun. The ways to feel better are multiple. For example, possessing things that are considered better or novel by others can place the child in a position of power and take advantage of this to make fun of or even exclude the rest of the peers who do not share this status as can be seen in this example with video game consoles:

“I know a case that happened to a friend of mine, he had a Nintendo Switch when it had just been released. As I don’t have it, and neither does my other friend, he would say “I have a Nintendo Switch and I have Super Mario 11” and he would start bragging. He was bragging because it was more expensive, and they bought it to him, and he feels special.”

On some occasions, it seems that children consider it a positive thing to be envied by others for what they possess. In many occasions, this is given by the economic value of these objects:

“For example, you say that they are going to give you a present if you get good grades, and then people compare what they have with others. And they ask you, how much money did it cost? It cost me 100 and you prefer not to tell them how much yours cost because the most important thing is that you like it. They tell you that it’s better to say how much it costs because then you can tell how good it is.”

Status is not always marked by material possessions. In this regard, being a relevant figure in the school (popular) or having access to figures of power, such as having family members who are teachers or directors, can give certain power to children who use this to position themselves above others. Access to power figures seems to be more important at younger ages while, as adolescence progresses, it seems to be more important to be popular or to have followers. The following example would refer to this idea.

“he’s always laughing at others, but it’s because his mother is a teacher and he thinks he’s better.”

This type of attitude may be accentuated if the object (or relevant figure) itself is something that only the minor or a very small group of minors in the school possesses. The magnitude of the associated violent behaviors may be increased in relation to this, leading to the generalization of this type of behavior to a larger number of peers in the school.

Attitudes toward aporophobic violence in school perceived as legitimate

On occasions, minors consider it fair or legitimate to exercise violence toward peers based mainly on aspects related to the material objects they own or access to these relevant figures mentioned above. One aspect that seems to be of importance is the “branding” of the things owned. That is to say, the group seems to strongly penalize those minors who do not wear “prestigious brand” clothing in their social circle, with teasing and exclusion predominating. Objects or garments that imitate “prestigious brands” deserve special mention due to their high prevalence and intensity of the associated behaviors. If the footwear they wear is an imitation of one of these “brands,” the group can legitimize violent behaviors of greater intensity, even reaching the point of physical violence:

“If you don’t wear brand shoes, you wear imitations, they take it out on you.”

“Well, many times it usually happens because of the shoes. Because many times kids wear ones … That are not of a brand, right? Imitation, basically, right? And other kids go and say: look! These are Nike and they cost me 100 euros, and you don’t! You are wearing 10-euro shoes (laughs).”

“Maybe she’s wearing an Adidas T-shirt and I’m wearing a fake [Adidas] one and she says: ‘Oh, yours is from the market, whatever … Look at her, she’s wearing one from the market’.”

“Just because you’re wearing something fake you are less than me.”

The legitimization of violence based on what one has or does not have can lead minors to violent behaviors that are aimed at damaging or destroying the things of others that are perceived to be of lesser value:

“Sometimes they step on my sneakers and yeah, I don’t know. Because they don’t cost the same as theirs.”

“They also step on [your shoes] if you wear high heels or you are not fashionable.”

Although the clothes the children are wearing seems to be an important factor here, they claim that other aspects are even more relevant, such as whether an object looks ugly to them, such as the backpack or pencil case they have, or how expensive the cell phone they have is:

“If you have an iPhone, then you have more money, they can afford it. If they have an Android phone or that stuff, then they don’t have as much money, they can’t afford to buy an iPhone. If you have that you can do whatever you want.”

The idea of what you have varies by age. Younger students tend to have fewer possessions so they may make these distinctions based on the possessions their parents or guardians have:

“How many TVs, how many cars you have … If you have a Smart TV, you are God.”

An exceptional case of legitimization is based on something that the whole school considers basic, i.e., that everyone has or should have. When a minor lacks this element, there seems to be greater justification for violent behavior. Some of these things could be the school uniform: “Worse things happen to you if you wear the old school equipment. ” In this type of circumstance, the child who lacks this element may receive violent behavior from many schoolmates:

“I once, for a whole year, I wore a swim cap from when I was in first grade, a yellow one. Everyone started laughing at me because I didn’t have the red one until I bought the other one in second grade.”

Attitudes toward aporophobic violence in school as a form of socialization

Attitudes toward aporophobic violence seem to influence the social interactions of minors. Although social behaviors, such as exclusion, are observed in the examples reported above, they are not included in this section because exclusion has been understood as the manifestation of violent behavior and not as a motivating attitude. In this regard, here we include attitudes that guide socialization with peers based on what they have or do not have.

When a minor differs physically from what is established for their sex, this is perceived as a sufficient reason to tease, ridicule, or perform other actions. This type of behavior is performed especially when the recipients are boys with characteristics associated with the feminine stereotype:

“For example, I once heard that some kids were fighting because one of them wanted to play dodgeball, and those that were playing wouldn’t let him because he was wearing the old school equipment. And they said ‘You can’t play because you are not updated’.”

“The Fila brand shoes, the girls who wear them tell the others: why aren’t you wearing them? If you are not fashionable, you don’t play.”

In line with the above, there seems to be a social norm that leads children to relate more to those who are of the same status, i.e., those who have things of similar value or as new as those they own:

“There are shoes that I can’t wear because I have an allergy in my foot, so sometimes they leave me alone because I don’t wear the same shoes they wear.”

“If you have the newest console, if it’s the best console out there right now, they don’t discriminate you if you play some games.”

In general terms, these attitudes hardly occur in isolation. A minor can exercise violence toward another for not wearing brand clothing and do so with the social legitimization of these behaviors and with the aim of increasing their own self-esteem.

This study is an exploration of attitudes toward violence against those with fewer resources in a Spanish sample and their relationship with different manifestations of violence. The results obtained are in line with a possible attitude-behavior relationship previously discussed ( Kraus, 1995 ; Pina et al., 2022 ).

From the perspective of school violence, data on the participants’ experiences obtained through qualitative studies allow a better understanding of this social phenomenon, favoring the specificity of the results, a prerequisite for the design of more effective intervention programs ( Merrell et al., 2008 ).

Regarding the hypothesis of our study, the results obtained show the existence of attitudes toward aporophobic violence in schools. Specifically, it is observed that these attitudes are related to the use of violence as a way of feeling better about oneself, perceived as legitimate and as a way of relating to peers. All these blocks interact with each other, thus forming a complex network of attitudes and behaviors that influence school coexistence problems that especially affect students from families of low socioeconomic levels.

At the time of this study, there is no knowledge of previous studies that explore attitudes toward school violence from the perspective of aporophobia. However, several studies have delved into the attitude-violent behavior relationship in the school context. For example, Pina et al. (2021a) concluded, in a study similar to this one, that attitudes toward school violence in the general population are related to violence to feel better about oneself, as a form of fun, perceived as legitimate, when directed at those who are different, when it has no consequences, as a way to resolve conflicts, as a way to socialize, and as a way to attract the attention of peers. Likewise, the study by Pina et al. (2021b) identifies four types of attitudes toward violence directed toward students belonging to the LGBTQI + community were identified, these being the use of violence as a form of fun, to feel better, when it is perceived as legitimate and as a way of relating to members of this community. The results presented in both studies partially agree with ours, sharing two of the topics obtained.

From the perspective of studies on aporophobia, there is previous evidence on the relationship between attitudes toward violence and socioeconomic status of students. Along these lines, a positive correlation has been found between attitudes toward violence and belonging to a higher socioeconomic level ( Massarwi and Khoury-Kassabri, 2017 ). Students with a high family income level in their samples present a higher risk of being bullies ( Barboza et al., 2009 ; Chang et al., 2013 ). In turn, adolescents from low socioeconomic status families would be at higher risk of victimization ( Due et al., 2009b ). Furthermore, Due et al. (2009b) suggested that the association between SES and bullying behavior may be more salient when SES among students varies markedly from the overall wealth of a school or community. These results would support those presented in our study where, according to the interviews, minors with greater economic resources could have greater access to valuable, novelty or “branded” objects, enhancing their attitudes toward violence and, therefore, increasing the risk of manifesting such attitudes in the form of school violence. However, there are studies that claim that socioeconomic status is not a variable statistically associated with being a perpetrator of school violence ( Wang et al., 2009 , 2012 ; Larochette et al., 2010 ; Magklara et al., 2012 ; Shetgiri et al., 2013 ). Taking this into account, it would be interesting to propose studies that consider violence among students from the same school who are perceived as belonging to different social statuses in order to reach more solid conclusions.

Regarding the topics obtained in our analysis, the children showed a wide range of attitudes toward violence as a way to feel better about themselves or to increase their self-esteem. Based on the data, the issue lies in the need to increase self-esteem, even though it may be apparently high ( Pina et al., 2021a ). Previous studies highlight that high and low levels of self-esteem have been related to increased bullying perpetration ( Tsaousis, 2016 ). Specifically, other works have found a positive association between self-esteem and being a bully, such that the probability of being a bully is higher when the student has high self-esteem ( Guerra et al., 2011 ). In our understanding, minors see in material things an opportunity to differentiate themselves from others and position themselves as a person of value in their social circle, using things as a way to “inflate” self-esteem. As has been observed in previous studies (e.g., Ruiz-Hernández et al., 2020 ), the legitimization of school violence is one of the most influential factors in the manifestation of violent behavior. This could drive violent behaviors in children who have more things than others simply because they have them, and these behaviors could become normalized in schools. In this regard, violence toward those who don’t own objects or garments is also observed in the focus groups of other qualitative studies, for example, in Morrow (2001) , Daly and Leonard (2002) , and Willow (2002 , p. 53). For many minors, especially among older age groups, social acceptance meant being able to dress similarly to others in their social circle, wearing brand-name clothing, for example ( Attree, 2006 ). Likewise, the children interviewed showed a wide range of attitudes toward violence as a way of socializing. In this line, it has been found that violence can be used to socialize, especially if social skills have not been developed ( Werner and Hill, 2010 ). Social skills, together with the level of maladjustment, indirectly predict involvement in bullying ( Postigo et al., 2012 ).

Based on our results, on direct experience and on what has been previously presented in the bibliography ( Middleton et al., 1994 ; Morrow, 2001 ; Daly and Leonard, 2002 ; Willow, 2002 ; Backett-Milburn et al., 2003 ; Attree, 2006 ; p. 53), we consider it appropriate to make a theoretical approach to the reality of aporophobia in schools. In this sense, there seem to be three fundamental dimensions that serve as a basis for establishing the hierarchical structure or status of the school. These three dimensions are: (a) the amount of expensive or brand-name items owned, (b) the exclusive or fashionable items owned, and (c) access to relevant or powerful figures. As our results show, children base their violent aporophobic attitudes on one or more of these dimensions. The reader should bear in mind that the culture of the school itself will mark what is considered expensive, novel or a power figure. This means that one object may be considered very valuable in one school, but of little or no value in another. In our understanding, the relational dynamics that arise according to these three dimensions generate four statuses in the schools. These would be: (a) high status, defined by those children who stand out in all three dimensions (for example: they have expensive or brand items, are fashionable and popular); (b) medium-high status, encompassing those children who have some of these resources considered special; (c) medium-low status, composed of children who do not stand out in any of these dimensions but do not lack anything considered essential and; (d) low status, which would include children who lack something that is considered basic in the culture of their school. Based on this structure, attitudes toward violence and aporophobic violent behavior would have a hierarchical character. In this sense, children who perceive themselves as having a higher status than others might have higher attitudes toward this type of violence in order to feel better or as a way of socializing. The rest of the group could legitimize/normalize those attitudes toward violence when they are directed from a member of a higher status to a lower status. In short, based on the proposals of various works ( Smith, 1976 ; Cortina, 1995 ; Martínez, 2002 ; Andrade, 2008 ; Bakke, 2011 ; Pozo-Enciso and Arbieto-Mamani, 2020 ), aporophobia in the school context could be defined as emotions, attitudes and/or behaviors of rejection of peers who are perceived as “poorer” or of lower social status. This perception is induced or learned through the culture of the school itself, laying the foundations of the socioeconomic system or status of minors. Thus, according to Attree (2006) review of qualitative studies, these disadvantages in childhood can lead to the perception that economic and social constraints are natural and normal, which has an impact on children’s life expectancy.

The conclusions reached in this study have a wide variety of implications for socio-community intervention and research. In terms of research, the qualitative approach to attitudes toward violence based on aporophobia is a novel contribution to this field of study. This study provides evidence to the previous quantitative studies, allowing us to explore the specificity, complexity, and variety of attitudes. Our results are useful to understand the school climate and school violence based on aporophobia, facilitating the proactive participation of children in knowledge-building about the subject.

Regarding socio-community intervention, our results suggest that it is important to include a change of attitude toward violence within the programs to improve coexistence in the academic area. As mentioned earlier, meta-analytic studies suggest that modification of attitudes toward violence is an effective perspective to improve the school climate ( Mytton et al., 2006 ; Fox et al., 2010 ; Jiménez-Barbero et al., 2012 , 2016 ).

Implications for research and practice

The findings of this study have a wide range of implications not only from a research point of view but also from a welfare point of view. First, this qualitative approach to attitudes toward violence makes a new contribution to the field. On the one hand, attitudes are usually approached from a quantitative point of view, with our results being useful for the research topic through the proactive participation of students. In this sense, the qualitative approach allows a better understanding of emotional experiences and how they occur in their contexts ( Callaghan et al., 2015 ). On the other hand, this study focuses on attitudes toward violence based on aporophobia. Studies dealing with this type of population are almost non-existent, so these results can serve as a basis for future research. Finally, our results and theoretical proposals suggest the usefulness of designing school violence prevention or intervention plans from the approach of changing attitudes toward violence. Some programs already address this problem considering attitudes with excellent results ( Jiménez-Barbero et al., 2016 ), however, it could be useful to improve the specificity of these programs, adapting them to the context of children with diverse characteristics, thus increasing their effectiveness.

This study has some limitations. For example, in qualitative studies it is not possible to generalize the results, so it would be interesting to replicate similar studies in other countries or social contexts. This type of work would allow us to explore the similarities and differences with the results described here. Another limitation of this study would be the small sample size. Although qualitative studies are characterized by limited samples, it would be interesting to carry out studies especially with primary school students or with secondary school students, specifically with larger sample sizes. Another limitation of this study is that no values were collected for the socioeconomic level of the participants or the school. According to Due et al. (2009b) , the association between SES and bullying behavior may be more salient when SES among students varies markedly from the general wealth of a school or community, so collecting this information will contribute more information to the study.

In our opinion, it would be advisable to complement the results of this study with quantitative studies, either by applying or creating instruments specific to this type of attitudes toward violence. Finally, the use of an incidental sample of three schools may not be representative of the adolescent population of the region or the country. In our understanding, the culture of the center will be what marks what is “good” or “bad,” “new” or “old” and, therefore, will have a direct influence on attitudes toward aporophobic violence. However, we believe that the formal structure and dynamics mentioned will be relatively stable between schools and can serve as a basis for the interpretation of similar studies.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Murcia (ID: 2317/2019). Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author contributions

DP and MM-T contributed to the conception and design of the study. DP conducted the interviews. DP, MM-T, EP-L, and JR-H conducted the qualitative analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. DP, MM-T, RL-L, and LM-A wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

The publication of this article was funded by the Applied Psychology Service of the University of Murcia.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank all the participants of this study, as well as their mothers, fathers, legal guardians, and the professionals of the schools for their participation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Alikasifoglu, M., Erginoz, E., Ercan, O., Uysal, O., and Albayrak-Kaymak, D. (2007). Bullying behaviours and psychosocial health: results from a cross-sectional survey among high school students in Istanbul, Turkey. Eur. J. Pediatr . 166, 1253–1260. doi: 10.1007/s00431-006-0411-x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Álvarez-García, D., Núñez, J. C., García, T., and Barreiro-Collazo, A. (2018). Individual, family, and community predictors of cyber-aggression among adolescents. Eur. J. Psychol. Appl. Leg. Context. 10, 79–88. doi: 10.5093/ejpalc2018a8

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Andrade, M. (2008). >Qué es la “aporofobia”? Un análisis conceptual sobre prejuicios, estereotipos y discriminación hacia los pobres. Agenda Soc. 2, 117–139.

Google Scholar

Ardiles, F. (2008). Apuntes sobre la pobreza y su cultura. Observat. Lab. Rev. Venezolan 1, 127–137.

Attree, P. (2006). The social costs of child poverty: A systematic review of the qualitative evidence. Child. Soc. 20, 54–66. doi: 10.1002/chi.854

Backett-Milburn, K., Cunningham-Burley, S., and Davis, J. (2003). Contrasting lives, contrasting views? Understandings of health inequalities from children in different social circumstances. Soc. Sci. Med. 57, 613–623. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00413-6

Bakke, K. (2011). The opposite of poverty is not plenty, but friendship: “Dorothy Day’s pragmatic theology of detachment. Ph D thesis, Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania.

Barboza, G. E., Schiamberg, L. B., Oehmke, J., Korzeniewski, S. J., Post, L. A., and Heraux, C. G. (2009). Individual characteristics and the multiple contexts of adolescent bullying: An ecological perspective. J. Youth Adolesc. 38, 101–121. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9271-1

Bowes, L., Arseneault, L., Maughan, B., Taylor, A., Caspi, A., and Moffitt, T. E. (2009). School, neighborhood, and family factors are associated with children’ s bullying involvement: a nationally representative longitudinal study. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. 48, 545–553. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819cb017

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Callaghan, J. E. M., Alexander, J. H., Sixsmith, J., and Fellin, L. C. (2015). Beyond “witnessing:” Children’s experiences of coercive control in domestic violence and abuse. J. Interpers. Viol . 33, 1551–1581. doi: 10.1177/0886260515618946

Chang, F., Lee, C., Chiu, C., Hsi, W., Huang, T., and Pan, Y. (2013). Relationships among cyberbullying, school bullying, and mental health in Taiwanese adolescents. J. Sch. Health 83, 454–462. doi: 10.1111/josh.12050

Comim, F., Borsi, M. T., and Valerio Mendoza, O. (2020). The Multi-dimensions of Aporophobia. Ph D thesis, Germany: Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich.

Cortina, A. (1995). La educación del hombre y del ciudadano. Rev. Iberoam Educ. 7, 41–63.

Cortina, A. (1996). Ética. Spain: Editorial Santillana.

Cortina, A. (2000). Aporofobia. Spain: El País.

Daly, M., and Leonard, M. (2002). Against all odds: Family life on a low income in Ireland. Ireland: Combat Poverty Agency.

Davis, J., and Ridge, T. (1997). Same scenery, different lifestyle: Rural children on a low income. London: The Children’s Society.

Due, P., Damsgaard, M. T., Lund, R., and Holstein, B. E. (2009a). Is bullying equally harmful for rich and poor children?: A study of bullying and depression from age 15 to 27. Eur. J. Public Health 19, 464–469. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckp099

Due, P., Merlo, J., Harel-Fisch, Y., Damsgaard, M. T., Holstein, B. E., Hetland, J., et al. (2009b). Socioeconomic inequality in exposure to bullying during adolescence: A comparative, cross-Sectional, multilevel study in 35 countries. J. Am. Public Health Assoc. 99, 907–914. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.139303

Earnshaw, V. A., Reisner, S. L., Menino, D. D., Poteat, V. P., Bogart, L. M., Barnes, T. N., et al. (2018). Stigma-based bullying interventions: A systematic review. Dev. Rev. 48, 178–200. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2018.02.001

Edwards, K. M., Rodenhizer, K. A., and Eckstein, R. P. (2020). School personnel’s bystander action in situations of dating violence, sexual violence, and sexual harassment among high school teens: A qualitative analysis. J. Interpers. Viol. 35, 2358–2369. doi: 10.1177/0886260517698821

Elgar, F. J., Craig, W., Boyce, W. T., Morgan, A., and Vella-Zarb, R. (2009). Income inequality and school bullying: Multilevel study of adolescents in 37 countries. J. Adolesc. Health 45, 351–359. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.04.004

Fox, C. L., Elder, T., Gater, J., and Johnson, E. (2010). The association between adolescents’ beliefs in a just world and their attitudes to victims of bullying. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 80, 183–198. doi: 10.1348/000709909X479105

Fraguas, D., Díaz-Caneja, C. M., Ayora, M., Durán-Cutilla, M., Abregú-Crespo, R., Ezquiaga-Bravo, I., et al. (2021). Assessment of school anti-bullying interventions: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Pediatr. 175, 44–55. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.3541

Fu, Q., Land, K. C., and Lamb, V. L. (2013). Bullying victimization, socioeconomic status and behavioral characteristics of 12th graders in the United States, 1989 to 2009: Repetitive trends and persistent risk differentials. Child Indic. Res. 6, 1–21. doi: 10.1007/s12187-012-9152-8

Galobardes, B., Shaw, M., Lawlor, D. A., and Lynch, J. W. (2006a). Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1). J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 60, 7–12.

Galobardes, B., Shaw, M., Lawlor, D. A., and Lynch, J. W. (2006b). Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 2). J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 60, 95–101. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.028092

Glew, G. M., Fan, M. Y., Katon, W., Rivara, F. P., and Kernic, M. A. (2005). Bullying, psychosocial adjustment, and academic performance in elementary school. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med . 159, 1026–1031. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.11.1026

Guerra, N. G., Williams, K. R., and Sadek, S. (2011). Understanding bullying and victimization during childhood and adolescence: A mixed methods study. Child Dev. 82, 295–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01556.x

Ho, A., Sidanius, J., Pratto, F., Levin, S., Thomsen, L., Kteily, N., et al. (2012). Social dominance orientation: Revisiting the structure and function of a variable predicting social and political attitudes. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 38, 583–606. doi: 10.1177/0146167211432765

Jansen, D. E. M. C., Veenstra, R., Ormel, J., Verhulst, F. C., and Reijneveld, S. A. (2011). Early risk factors for being a bully, victim, or bully/victim in late elementary and early secondary education. The longitudinal TRAILS study. BMC Public Health 11:440–447. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-440

Jansen, P. W., Verlinden, M., Dommisse-van Berkel, A., Mieloo, C., Van der Ende, J., Verhulst, F. C., et al. (2012). Prevalence of bullying and victimization among children in early elementary school: do family and school neighbourhood socioeconomic status matter? BMC Public Health 12:494–504. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-494

Jiménez-Barbero, J. A., Ruiz-Hernández, J. A., Llor-Esteban, B., and Pérez-García, M. (2012). Effectiveness of antibullying school programmes: A systematic review by evidence levels. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 34, 1646–1658. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.04.025

Jiménez-Barbero, J. A., Ruiz-Hernández, J. A., Llor-Zaragoza, L., Pérez-García, M., and Llor-Esteban, B. (2016). Children and youth services review effectiveness of anti-bullying school programs: A meta-analysis. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 61, 165–175. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.12.015

Kraus, S. J. (1995). Attitudes and the Prediction of Behavior: A Meta-Analysis of the empirical literature. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 21, 58–75. doi: 10.1177/0146167295211007

Krueger, R. A. (ed.) (1991). El grupo de discusión. Guía práctica para la investigación aplicada [Focus groups: Practical guide for applied research]. Spain: Pirámide.

Larochette, A., Murphy, A. N., and Craig, W. M. (2010). Racial bullying and victimization in Canadian school-aged children: Individual and school level effects. Relationships among cyberbullying, school bullying, and mental health in Taiwanese adolescents. Sch. Psychol. Int. 31, 389–408. doi: 10.1177/0143034310377150

Lumeng, J. C., Forrest, P., Appugliese, D. P., Kaciroti, N., Corwyn, R. F., and Bradley, R. H. (2010). Weight status as a predictor of being bullied in third through sixth grades. Pediatrics 125, 1301–1307. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0774

Magklara, K., Skapinakis, P., Gkatsa, T., Bellos, S., Araya, R., Stylianidis, S., et al. (2012). Bullying behaviour in schools, socioeconomic position and psychiatric morbidity: A cross-sectional study in late adolescents in Greece. Child Adolesc. Psych. Ment. Health 6, 1–13. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-6-8

Malecki, C. K., Demaray, M. K., Smith, T. J., and Emmons, J. (2020). Disability, poverty, and other risk factors associated with involvement in bullying behaviors. J. Sch. Psychol. 78, 115–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2020.01.002

Martínez, E. (2002). “Aporofobia,” in Glosario Para una Sociedad Intercultural , ed. J. Conill (Spain: Bancaja), 17–23.

Massarwi, A. A., and Khoury-Kassabri, M. (2017). Serious physical violence among Arab-Palestinian adolescents: The role of exposure to neighborhood violence, perceived ethnic discrimination, normative beliefs, and, parental communication. Child Abuse Negl. 63, 233–244. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.11.002

Merrell, K. W., Gueldner, B. A., Ross, S. W., and Isava, D. M. (2008). How effective are school bullying intervention programs? A meta-analysis of intervention research. Sch. Psychol. Q. 23, 26–42. doi: 10.1037/1045-3830.23.1.26

Middleton, S., Ashworth, K., and Walker, R. (1994). Family Fortunes: Pressures on Parents and Children in the 1990s. London, UK: Child Poverty Action Group (CPAG).

Miranda Miranda, J. K., Ganga León, C., and Crockett Castro, M. (2020). A qualitative account of children’s perspectives and responses to intimate partner violence in Chile. Ph D thesis, Santiago de Chile, Chile: Universidad de Chile. doi: 10.1177/0886260520903132

Morrow, V. (2001). Networks and Neighbourhoods: Children’s and Young People’s Perspectives. London, UK: Health Development Agency.

Mytton, J. A., DiGuiseppi, C., Gough, D., Taylor, R. S., and Logan, S. (2006). School-based secondary prevention programmes for preventing violence. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2006:CD004606. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004606.pub2

Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at school: What we know and what we can do. Psychol. Sch. 40, 699–700. doi: 10.1002/pits.10114

Pina, D., Llor-Esteban, B., Ruiz-Hernández, J. A., Luna-Maldonado, A., and Puente-López, E. (2021a). Attitudes towards school violence: a qualitative study with Spanish children. J. Interpers. Viol. 37, 13–14. doi: 10.1177/0886260520987994

Pina, D., Marín-Talón, M. C., López-López, R., Martínez-Sánchez, A., Simina-Cormos, L., Ruiz-Hernández, J. A., et al. (2021b). Attitudes toward school violence against LGBTQIA+. a qualitative study. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 18:11389. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182111389

Pina, D., López-Nicolás, R., López-López, R., Puente-López, E., and Ruiz-Hernández, J. A. (2022). Association between attitudes toward violence and violent behavior in the school context: A systematic review and correlational meta-analysis. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 22:100278. doi: 10.1016/j.ijchp.2021.100278

Postigo, S., González, R., Mateu, C., and Montoya, I. (2012). Predicting bullying: maladjustment, social skills and popularity. Educ. Psychol. 32, 627–639. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2012.680881

Pozo-Enciso, R. S., and Arbieto-Mamani, O. (2020). La aporofobia en el contexto de la sociedad peruana: Una revisión. Rev. Cien. Soc. Humanid. 30, 134–149. doi: 10.20983/noesis.2020.2.6

RAIS fundación (2017). Informe jurídico sobre aporofobia, el odio al pobre. España: RAIS Fundación.

Ruiz-Hernández, J. A., Pina, D., Puente-López, E., Luna-Maldonado, A., and Llor-Esteban, B. (2020). Attitudes towards school violence questionnaire, revised version: CAHV-28. Eur. J. Psychol. Appl. Leg. Context 12, 61–68. doi: 10.5093/ejpalc2020a8

Ruiz-Hernández, J. A., Moral-Zafra, E., Llor-Esteban, B., and Jiménez-Barbero, J. A. (2019). Influence of parental styles and other psychosocial variables on the development of externalizing behaviors in adolescents: a sytematic review. Eur. J. Psychol. Appl. Leg. Context 11, 000–000. doi: 10.5093/ejpalc2018a11

Shetgiri, R., Lin, H., and Flores, G. (2013). Trends in risk and protective factors for child bullying perpetration in the United States. Child Psych. Hum. Dev. 44, 89–104. doi: 10.1007/s10578-012-0312-3

Smith, A. (1976). The theory of moral sentiments , 6th Edn. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

Tippett, N., and Wolke, D. (2014). Socioeconomic Status and Bullying: A meta-analysis. Am. J. Public Health 104, e48–e59. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301960

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., and Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 19, 349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

Tsaousis, I. (2016). The relationship of self-esteem to bullying perpetration and peer victimization among schoolchildren and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. Aggress Viol. Behav. 31, 186–199. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2016.09.005

UNESCO (2017). School violence and bullying: Global status report. France: UNESCO.

Varela, J. J., Zimmerman, M. A., Ryan, A. M., Stoddard, S. A., and Heinze, J. E. (2018). School attachment and violent attitudes preventing future violent behavior among youth. J. Interpers. Viol. 36, 5407–5426. doi: 10.1177/0886260518800314

Wang, H., Zhou, X., Lu, C., Wu, J., Deng, X., Hong, L., et al. (2012). Adolescent bullying involvement and psychosocial aspects of family and school life: A cross-sectional study from Guangdong Province in China. PLoS One 7:e38619. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038619

Wang, J., Iannotti, R. J., and Nansel, T. R. (2009). School bullying among adolescents in the United States: Physical, verbal, relational, and cyber. J. Adolesc. Health 45, 368–375. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.021

Wardle, J., Robb, K., and Johnson, F. (2002). Assessing socioeconomic status in adolescents: The validity of a home affluence scale. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 56, 595–599. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.8.595

Werner, N. E., and Hill, L. G. (2010). Individual and peer group normative beliefs about relational aggression. Child Dev. 81, 826–836. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01436.x

Willow, C. (2002). Bread is Free: Children and Young People Talk about Poverty. London, UK: Children’s Rights Alliance.

Wolke, D., Woods, S., Stanford, K., and Schluz, H. (2010). Bullying and victimization of primary school children in England and Germany: Prevalence and school factors. Br. J. Psychol. 92, 673–696. doi: 10.1348/000712601162419

Woods, S., and Wolke, D. (2004). Direct and relational bullying among primary school children and academic achievement. J. Sch. Psychol. 42, 135–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2003.12.002

Keywords : attitudes, qualitative study, bullying, school violence, aporophobia, socioeconomic discrimination

Citation: Pina D, Marín-Talón MC, López-López R, Martínez-Andreu L, Puente-López E and Ruiz-Hernández JA (2022) Attitudes towards school violence based on aporophobia. A qualitative study. Front. Educ. 7:1009405. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.1009405

Received: 01 August 2022; Accepted: 01 September 2022; Published: 23 September 2022.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2022 Pina, Marín-Talón, López-López, Martínez-Andreu, Puente-López and Ruiz-Hernández. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: María Catalina Marín-Talón, [email protected]

This article is part of the Research Topic

Towards 2030: Sustainable Development Goal 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions. An Educational Perspective

TEACHERS AND STUDENTS’ PERCEPTIONS ABOUT SCHOOL VIOLENCE: A QUALITATIVE STUDY

ABSTRACT The study aimed to understand the perceptions of elementary and high school students and teachers about school violence. This is a qualitative study that used the focus group as a form of data collection. Physical and verbal violence were the most common responses about identified forms of school violence. Psychological and socioeconomic factors, damage to family relationships, personal and educational problems were identified as predisposing factors for the occurrence of different forms of school violence. Educational actions, participation of the public authorities in a punitive manner (police) and the presence of psychology, psychiatry and social assistance professionals were identified as measures to curb school violence, in addition to greater family involvement in the school. It is understood that school violence can be faced through the valorization of human rights and the joint action of the school, family and community.

Read full text

- http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1413-85572021000100319&lng=en&tlng=en

Usage metrics

- Educational Psychology

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Teacher and Peer Responses to Warning Behavior in 11 School Shooting Cases in Germany

Nora fiedler.

1 Department of Education and Psychology, Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin, Germany

Friederike Sommer

2 Department of Police and Security Management, Berlin School of Economics and Law, Berlin, Germany

Vincenz Leuschner

Nadine ahlig, kristin göbel, herbert scheithauer, associated data.

The datasets generated for this study will not be made publicly available. The datasets analyzed for this study, i.e., original inquiry files from law enforcement authorities, cannot be shared for legal and privacy restrictions.

Warning behavior prior to an act of severe targeted school violence was often not recognized by peers and school staff. With regard to preventive efforts, we attempted to identify barriers to information exchange in German schools and understand mechanisms that influenced the recognition, evaluation, and reporting of warning behavior through a teacher or peer. Our analysis is based on inquiry files from 11 cases of German school shootings that were obtained during the 3-year research project “Incident and case analysis of highly expressive targeted violence (TARGET).” We conducted a qualitative retrospective case study to analyze witness reports from school staff and peers. Our results point to subjective explanations used by teachers and peers toward conspicuous behavior (e.g., situational framing and typical adolescent behavior), as well as reassuring factors that indicated harmlessness (e.g., no access to a weapon). Additionally, we found organizational barriers similar to those described in US-American case studies (e.g., organizational deviance).

Introduction

A key finding from the retrospective analysis of cases of severe targeted school violence (e.g., school shootings) is that these violent acts can be regarded as an endpoint of a long-term negative developmental pathway (e.g., Levin and Madfis, 2009 ; Scheithauer et al., 2014 ; Sommer et al., 2020 ). Furthermore, there is a consensus in the literature on school shootings that several types of warning behaviors and indicators of a personal crisis were observable by persons in the school, family, or peer context prior to a violent act ( Hoffmann et al., 2009 ; Rocque, 2012 ; Bondü and Scheithauer, 2014b ; Gerard et al., 2016 ). Perpetrators either gave warning to peers by announcing an attack (“leakage” cf. Meloy et al., 2012 ), made direct threats to kill toward potential victims, or displayed behaviors that can be regarded as indicative of a psychosocial crisis (e.g., sudden behavioral changes, social withdrawal, or school absenteeism). However, as international case studies reveal, warning behaviors were often not recognized or responded to by the perpetrators’ peers and members of school staff ( Daniels J.A. et al., 2007 ; Syvertsen et al., 2009 ; Scheithauer and Bondü, 2011 ). Newman et al. (2004) found the inability of the social support systems to identify and bundle warning behaviors—beside social marginality, individual vulnerabilities, access to guns, and cultural scripts—to be one of five necessary conditions for school shootings. It is significant to understand why warning behaviors that became apparent in the school context were not recognized or adequately identified by peers and school staff, and—if identified—a progression of a negative psychosocial development could not be averted through case management measures. In that respect, research findings from US-American case studies provide some explanations taking schools’ organizational structures, as well as peer group norms, into account ( Fox and Harding, 2005 ; Daniels J. et al., 2007 ; Pollack et al., 2008 ). In the following, we present structural barriers as well as challenges school staff and peers are facing when identifying, assessing, evaluating, and handling students’ warning behaviors.

Awareness of Potential Warning Behavior

Research provides evidence that a school’s organizational complexity and lack of resources are barriers to successful communication and crisis management. Fox and Harding (2005) consider “organizational deviance” as a structural obstacle, meaning that warning behavior of students is not recognized and properly handled by school staff and results from routines and behaviors in an institution that were established to serve a specific purpose. For instance, Fox and Harding (2005) found a general tendency in members of large organizations to primarily respond to behavior that disturbs an organization’s day-to-day functioning (e.g., aggressive behavior; “The squeaky wheel gets the oil”; “decoy problem”). However, this scheme of action may not be sufficient in cases of students’ trajectories leading to severe school violence. Many school shooters did not show aggression or apparent frustration prior to an attack, even while already engaging into planning behavior, but were more “invisible kids,” a term used by Bender et al. (2001) referring to students who did not draw much teacher attention on them. Moreover, a single school staff member’s autonomy in day-to-day decision-making and task segregation can result in “structural secrecy” and “loose coupling” leading to what is described as “institutional memory loss” in the literature ( Vossekuil et al., 2002 ; Fox and Harding, 2005 ). Due to a lack of time resources, information on student warning behavior is often not shared with colleagues or reported to authorities ( Harding et al., 2002 ). Instead, an observation remains fragmented within a school. Moreover, typical conflict situations in a school require quick reactions from educational staff who primarily rely on gut feelings instead of an informed decision-making procedure ( Leuschner et al., 2011 ). A pilot study conducted in 2009, the Berlin Leaking Project, indicated a significant lack of knowledge and uncertainty in risk assessment among German school staff ( Bondü et al., 2011 ). Teachers reported a strong need for general sensitization and intense expert training to create awareness for the topic. Additionally, participants have demanded increasing support and counseling from their local professional network ( Leuschner et al., 2011 ). “Information fragmentation” can also occur when observations of a student behavior are not exchanged with professionals from a school’s external network and local service institutions. Eventually, a lack of inter-institutional cooperation can become a significant barrier to effective case management and the initialization of supportive measures for an adolescent in crisis ( Harding et al., 2002 ). Finally, an insufficient documentation of observations is another structural risk factor: data on apparently harmless disciplinary incidents are often not recorded in a student’s file due to law restrictions or a well-meant “clean-slate” mentality. Information on a student’s social biography, family background, or psychological particularities literally “diffuses” and cannot be integrated in case assessment after a student transitions to secondary school or another school district. From a developmental perspective, this can have a harmful impact, since teachers at a new school will have difficulties to evaluate the progression of a student’s crisis properly.

Identification and Correct Interpretation of Students’ Potential Warning Behavior

In the majority of cases, peers—and not adults—were the first to identify behavioral changes ( Bender et al., 2001 ; Oksanen et al., 2013 ; Madfis, 2014 ). In most cases, peers of subsequent perpetrators had advanced knowledge about a planned attack but followed a “code of silence” and opted to withhold knowledge or concern from an adult ( Daniels J.A. et al., 2007 ; Syvertsen et al., 2009 ; Madfis, 2014 ). The “code of silence” is a behavioral norm followed by adolescents to protect a peer from trouble, implying not to share conspicuous information (e.g., leaking behavior, or a peer’s problems) with an adult or authority figure. Thus, for the majority of school shootings, indicators of a perpetrator’s negative psychosocial development were hardly visible to adults; consequently, school staff did not obtain the significant information necessary to identify a student in crisis. In a qualitative study conducted by the United States Secret Service as part of the United States Safe School Initiative (SSI), Pollack et al. (2008) interviewed 119 students that were involved as bystanders in school shootings that happened in the United States. The authors refer to bystanders as “students who had some prior knowledge that an attack was planned.” The study revealed that 59% of bystanders reported advanced knowledge about the perpetrator’s violent fantasies, often days or weeks prior to the attack, and 82% had their information directly from the perpetrator, but did not share it ( Pollack et al., 2008 ). Additionally, school staff face challenges in the identification and correct interpretation of students’ warning behavior potentially leading to school shootings. Predictions of school shooting behavior based on risk factors of former shooters using checklists (i.e., profiling) are inappropriate, as they would lead to a high amount of falsely identified students, which may result in stigmatization and unreasonable reduced sense of safety in schools ( Borum et al., 2010 ). School staff may tend to rely on personal presumptions or media-disseminated knowledge about school shootings without reliable information about students’ warning behavior.

Evaluation of Seriousness of Students’ Threats and Warning Behavior

Peer bystanders mostly underestimated the seriousness of a threat (e.g., threat was a “joke” or made “in jest”) or did not believe their peer would be able to carry it out. Pollack et al. (2008) found “misjudgment of the likelihood and immediacy of an attack” and “disbelief in seriousness of threats” as explanations to keep information to themselves. Finally, Wike and Fraser (2009) identified “high-risk-school cultures” among US-American schools with a school shooting attack, which described a social climate that encourages low school bonding and high “social stratification” and provides few opportunities for participation, rewards, and positive interaction between teachers and students, hence fostering bullying, harassment, and other forms of violence. On the contrary, Eliot et al. (2010) used a sample of 7,318 students from 291 schools from the Virginia High School Safety Study to examine the correlation of characteristics related to school culture with school. The authors found that the students’ willingness to seek help from an adult when confronted with a threat of violence increases with a supportive school climate and perceived support from teachers, as well as a positive attitude toward the school ( Eliot et al., 2010 ).

Finding an Appropriate Response to Students’ Warning Behavior

One effort in preventing school violence in the United States is described under the term “zero tolerance,” referring to a range of policies that seek to impose severe sanctions (e.g., suspensions and school expulsion) for minor offenses in hopes of preventing more serious ones ( Borum et al., 2010 ; Muschert and Madfis, 2013 ). However, due to the lack of empirical evidence of any positive effect in deterring or reducing school violence, zero-tolerance policies have been questioned and even criticized as measures contrary to the principles of a healthy child development ( Gregory and Cornell, 2009 ; Borum et al., 2010 ). The challenge of finding an appropriate response to students’ warning behavior can be illustrated by Sommer et al. (2016) who analyzed interventions of school staff when confronted with a student’s psychosocial crisis at risk for a school shooting (cf. Bondü and Scheithauer, 2014c ). While in most cases school staff responded to the student crisis or warning behavior by initiating resource-oriented measures, finding appropriate interventions in high-risk cases (e.g., student in possession of guns, detailed execution plans) proved to be a particular challenge. Often lacking sustainable knowledge or networks to accessible experts (e.g., prevention officers and psychotherapists), school staff mostly dealt with the students’ critical behavior within the institution, which might have resulted in feelings of overstraining and unsafety ( Sommer et al., 2016 ).

To summarize, a growing body of case studies and research on organizational risk factors has produced valuable insights into the phenomenon of severe, targeted school violence from a social framing perspective. The identification of social and structural risk factors, organizational deviance, and a negative school climate along with a better understanding of why peers of subsequent perpetrators underestimated the seriousness of threats points to opportunities of school-wide prevention and measures with a focus on the individual perpetrator (e.g., risk assessment). The purpose of this study is to identify barriers to information exchange in German schools with a school shooting incident and to highlight organizational risk factors as well as risk factors resulting from peer group norms. Additionally, the paper will discuss underlying mechanisms and individual assumptions of peers and teachers that had an impact on the identification of conspicuous behavior and to investigate them more closely. With regard to preventive efforts, the following research questions will be addressed: (1) Which measures of case management were initiated either within the schools, or with the help of a school’s professional support network? (2) How did peers respond to threats and leakage, and what can we learn about adolescent code of silence and peer evaluation of conspicuous behavior? (3) Which assumptions and specific factors can be found in the material that led teachers and peers to assess a conspicuous behavior as concerning or alarming? How did teachers and peers attempt to explain a behavioral change in the perpetrator that in retrospect can be considered a warning behavior?

Eventually, by integrating research findings from United States studies on school risk factors with results from the analysis of German school shooting cases, we aim to introduce an environmental perspective—in addition to the identification of individual risk factors—on the developmental pathways toward school shootings. A study on motives and specific constellations of individual risk factors of the perpetrator (e.g., mental disorders) provides an understanding of why an individual commits a violent act. In addition, a deeper investigation of social and organizational risk factors will help to explain why warning signs were not taken seriously, or individual support measures failed, which could eventually open new windows for prevention (e.g., by enhancing the expertise of persons within the social environment of an adolescent in crisis, such as school staff and peers) and simultaneously increase their feelings of safety. Overall, the study serves the purpose to bring light to the question why past acts of severe targeted violence could not be averted by school-related interventions.

Materials and Methods

Case selection.