Publications

- Journal Articles

- Books: Books, Chapters, Reviews

- Working Papers

- Critical race theory, interest convergence, and teacher education

Richard Milner

Ebony O. McGee

Francis A. Pearman

In this chapter, we discuss Bell’s (1980) interest convergence, a key concept in critical race theory,1 as a useful analytic and strategic tool to analyze, critique, make sense of, and reform sites in teacher education that we argue should be studied and interrogated to improve policies and practices in the field. The tenet “interest convergence” originated with the work of Derrick Bell (1980), who argued that the Brown v. Board of Education (1954) decision, in which the Supreme Court outlawed de jure segregation of public schools, was not the result of a moral breakthrough of the high court but rather a decision that was necessary: (1) to advance American Cold War objectives in which the United States was competing with the Soviet Union for loyalties in the third world; (2) to quell the threat of domestic disruption that was a legitimate concern with Black veterans, who now saw continued discrimination as a direct affront to their service during WWII; and (3) to facilitate desegregation in the South, which was now viewed as a barrier to the economic development of the region. In other words, the interests of Black civil rights coincided for a brief time with the interests of White elites, thus enabling a decision that benefited the interests of Black people. In Bell’s (1980) words, “the interests of Blacks in achieving racial equality will be accommodated only when it converges with the interests of Whites”

Primary Research Area:

- Poverty and Inequality

Topic Areas:

- Other , Societal Context

APA Citation

You are here.

Critical Race Theory

Brown v. Board of Education and the Interest-Convergence Dilemma

In this article, Bell outlines the concept of interest convergence, an idea that has since become vital to Critical Race Theory, through an analysis of the Brown v. Board of Education decision. Interest convergence has proven to be a useful tool in understanding how historical racial reforms are achieved. Here, Bell argues that, though popular discourses of American history present the Brown decision as motivated by moral and political convictions, it can be better understood as a result of intersecting practical considerations. Bell compares the circumstances of the case to similar preceding cases challenging school segregation. In those previous instances, the courts ruled not to end segregation in schooling, but to improve the standards of segregated schooling, to meet the standards of the “separate but equal” doctrine. What, Bell asks, makes Brown different? Interest convergence answers this question.

The outcome of Brown v. Board of Education was the result of a convergence of racial interests with a number of interests for the dominant class, domestically and abroad. Agitation was growing within the Black American population, many of whom had contributed to the nation’s success in World War II, and many of whom were increasingly dissatisfied with a continued lack of progress in racial reform. The dominant class faced a threat of civil unrest; more importantly, they risked the growth of communist sympathies within the United States. Abroad, claims of political freedom from the US, contrasted with continued segregation, threatened America’s international reputation, a particularly valuable resource given the ongoing Cold War with the USSR. Finally, as the post-war economy was booming, segregation (like enslavement before it) stood in the way of urbanization and industrialization, in the South in particular. As a result of the intersection of these social, political, and economic interests, it became more costly for the dominant class to maintain segregation than it would be to gradually abolish it.

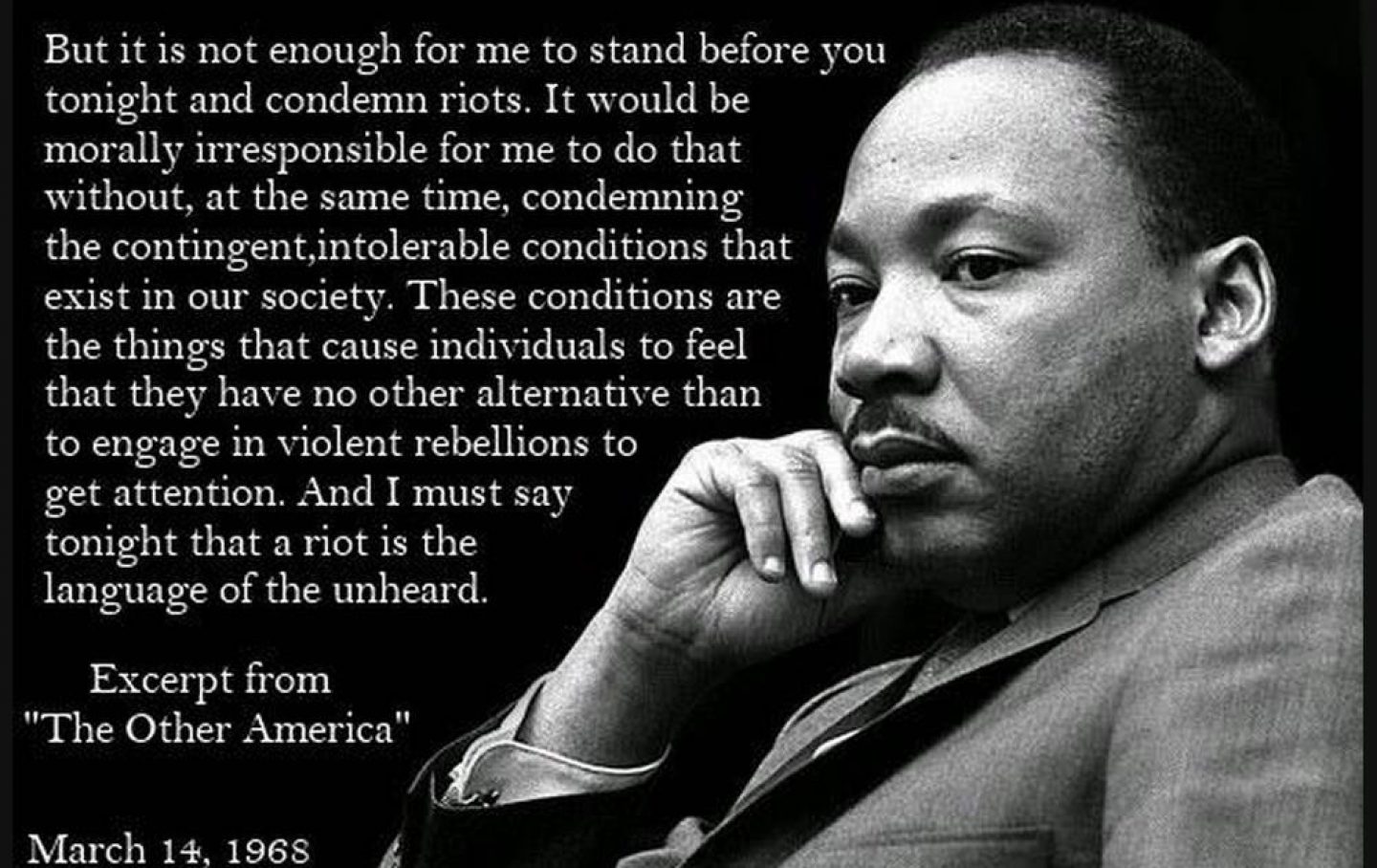

Applied to other historical instances of racial reform, interest convergence is similarly useful. What, for example, could an application of interest convergence explain about the Emancipation Proclamation, the Fourteenth Amendment, or even the success of Barrack Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign? Moreover, interest convergence is valuable as a tool through which to imagine how contemporary and future movements towards Black liberation may find success. While interest convergence theory emphasizes the agency of the dominant class in the movements of history, it also emphasizes the ways in which the agency of marginalized classes can bring about change. The threat of social unrest, or even insurrection, can impact the cost-benefit analysis employed by the dominant class; at times, this impact is enough to precipitate meaningful reform.

Paying attention to the changing interests and circumstances of the dominant class can be a legitimate strategy for Black liberation movements, as tracking these changes, like tracking the weather, might be informative concerning when particular political strategies may be the most effective. As Bell notes, “Further progress to fulfill the mandate of Brown is possible to the extent that the divergence of racial interests can be avoided or minimized” (Bell 528). If the actions of liberatory movements can take advantage of moments of convergence, as well as divergence, the political landscape of the United States could be strategically altered, reformed, or, even, radically reimagined.

(Point of clarification: when I note that interest convergence can be usefully applied in pursuit of liberation, I am not arguing for making appeals to white moderates, or for tactics of respectability and collaboration regarding dominant political classes. What I am trying to argue is that the actions of radical movements can change the cost-benefit analysis that the dominant class engages in, in pursuit of its interests. For example, the outcome of Brown was meaningfully influenced by the threat of domestic unrest. Likewise, the Haitian Revolution succeeded in part because the acts of revolutionaries made it too costly for France or any other imperial power to try to directly reassert enslavement on the Haitian people.)

3 Replies to “ Brown v. Board of Education and the Interest-Convergence Dilemma ”

Gabriel, I liked your point about the importance of interest convergence and divergence. I was also wondering about this likelihood, especially with the tensions between political parties and the growing popularity of politicians like Donald Trump and Ron DeSantis. I was thinking about what they would say if you suggested that interest convergence is a tool they could use to help with Black liberation and allow marginalized classes to create change and have change happen to them. That’s super important about this class, but it’s also a little disheartening how Critical Race Theory is treated in the U.S. and how few people know what it means. A big takeaway from the article was that the primary goal is to create effective schools for black children. I was interested in learning this in ProfSi’s ‘Money Politics and Prison class last semester. It is how the school system’s discrimination and marginalization of students of color directly impact the Prison Industrial Complex, and I think the article does an excellent job of reinforcing the importance of good schooling and school systems like successful magnet schools, for example. I’m from Baltimore City, and I have seen the direct impacts of states/governments letting students and communities down when it comes to educating the young.

I really like how you not only summarized some of the key points in the reading but you also highlighted why they are important. I liked how you mention using the demands of the dominant class to help with black liberation. I also believe this tactic is crucial because we can get people to see that we are not so different from each other, not just in race but in class too. By utilizing this tactic, black people may find that their initiatives are followed by more support. The article mentions how because of Brown’s decision, a large majority of the white population thought they would lose their influence or power (pg 35 and 37). The “interest-convergence” comes into play when the white families leave their schools to attend these newly created private ones. Black students not only get a proper funded education but the white families can either keep attending school or attend a private one.

I will say that Brown v. Board is an interesting case for a couple of points. First, by targeting education as the point of interest, it allows black people to delve into multiple other areas. For example housing is closely related to schooling and they wanted this case to eventually start to leak into that area as well. But justice moves slowly and one step at a time. What the black population needed was to first end Plessy v. Ferguson. By overturning this case first, “separate but equal” was considered unconstitutional. Although Brown was very significant, there’s other cases that played a more important role such as Bradley v. Richmond or Green v. New Kent County (this threatened schools to cooperate or federal funding will stop from HEW). It goes back to what they first needed to accomplish and that was ending separate but equal. It forced schools to desegregate but there was barely any push for integration. The actual text from Brown v. Board was how schools should “desegregate with all deliberate speed”. This is problematic because it allows schools to move on their own account. As we know, this made schools follow through very late after the decision. What it comes down to is being a resource problem. It’s not about morality right or wrong, changes were made due to resources. This is where interest-convergence comes into play.

Derrick Bell’s analysis of the Brown v. Board of Education decision reveals how the interests of different groups, particularly Black Americans and the dominant class, intersected strategically. The fear of civil unrest, potential communist sympathies, and the international reputation of the U.S. during the Cold War made segregation costly for the dominant class.

This convergence of interests played a role in the decision to end school segregation. Bell suggests that grasping the interests of those in power can guide Black liberation movements. It’s not about trying to please those in charge but using their interests to advocate for what’s right.

However, while the idea of interests aligning can be useful, it raises a concern. Progress might seem real, but there’s a risk it could resemble the deceptive “separate but equal” era. This cautionary note questions whether advancements in racial equality are genuine or just symbolic, echoing worries from the Plessy v. Ferguson era. The reminder that interest convergence doesn’t always guarantee true equality serves as a critical lens to scrutinize societal changes. It prompts us to be wary of situations where progress might be more appearance than reality. In essence, Bell’s insights emphasize the need for a careful and critical approach to assessing the genuineness of advancements in the fight for racial equality.

Comments are closed.

- DOI: 10.1177/0022487108321884

- Corpus ID: 145607803

Critical Race Theory and Interest Convergence as Analytic Tools in Teacher Education Policies and Practices

- IV H. Richard Milner

- Published 1 September 2008

- Education, Political Science, Sociology

- Journal of Teacher Education

344 Citations

Counter-narrative as method: race, policy and research for teacher education.

- Highly Influenced

Framing Critical Race Theory and Methodologies

Critical race theory: disruption in teacher education pedagogy, disrupting policies and reforms in mathematics education to address the needs of marginalized learners, critical race theory and the teacher education curriculum: challenging understandings of racism, whiteness, and white supremacy, critical race theory 20 years later, the paradox of teaching for social justice: interest convergence in early-career educators, institutional racism and anti-racism in teacher education: perspectives of teacher educators, critical race theory and the whiteness of teacher education, putting antiracism into action in teacher education: developing and implementing an antiracist pedagogy course audit, 73 references, and we are still not saved: critical race theory in education ten years later.

- Highly Influential

- 20 Excerpts

Critical-Race Educational Foundations: Toward Democratic Practices in Teaching “Other People's Children” and Teacher Education

The burden of teaching teachers: memoirs of race discourse in teacher education, uncertain allies: understanding the boundaries of race and teaching., critical race theory, multicultural education, and the hidden curriculum of hegemony, toward a critical race theory of education, cross cultural competency and multicultural teacher education, race, culture, and researcher positionality: working through dangers seen, unseen, and unforeseen, chapter 7: preparing teachers for diverse student populations: a critical race theory perspective, what precipitates change in cultural diversity awareness during a multicultural course, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

Review of Stamped from the Beginning: The definitive history of racist ideas in America

- Laura C. Chávez-Moreno University of California, Los Angeles http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6804-4961

Author Biography

Laura c. chávez-moreno, university of california, los angeles.

Laura C. Chávez-Moreno is a Postdoctoral Scholar in UCLA’s Graduate School of Education & Information Studies. Guided by a background in ethnic studies and languages/literacies, Laura’s research engages questions about Chicanx/Latinx education, critical literacy, and racial equity. Her work on teaching and teachers has been published in the Handbook of research on teaching (5 th ed.), Pennsylvania Language Forum , Peabody Journal of Education , and Journal of Teacher Education .

Alemán, E., & Alemán, S. M. (2010). 'Do Latin@ interests always have to "converge" with White interests?': (Re)claiming racial realism and interest-convergence in critical race theory praxis. Race Ethnicity and Education, 13(1), 1-21. doi: 10.1080/13613320903549644

Brayboy, B. M. J. (2005). Toward a tribal critical race theory in education. The Urban Review, 37(5), 425-446. doi: 10.1007/s11256-005-0018-y

Burns, M. (2017). “Compromises that we make”: Whiteness in the dual language context. Bilingual Research Journal, 40(4), 339-352. doi: 10.1080/15235882.2017.1388303

Castagno, A. E. (2014). Educated in whiteness: Good intentions and diversity in schools. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Dumas, M. J. (2016). Against the dark: Antiblackness in education policy and discourse. Theory Into Practice, 55(1), 11-19. doi: 10.1080/00405841.2016.1116852

Flores, N., Lewis, M. C., & Phuong, J. (2018). Raciolinguistic chronotopes and the education of Latinx students: Resistance and anxiety in a bilingual school. Language & Communication, 62, 15-25.

Garmon, M. A. (2004). Changing preservice teachers’ attitudes/beliefs about diversity: What are the critical factors?. Journal of Teacher Education, 55(3), 201-213.

Harper, S. R. (2009). Race, interest convergence, and transfer outcomes for Black male student athletes. New Directions for Community Colleges(147), 29-37.

Kumar, R., & Lauermann, F. (2017). Cultural beliefs and instructional intentions: Do experiences in teacher education institutions matter? American Educational Research Journal, 55(3) doi: 0002831217738508.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1999). Preparing teachers for diverse student populations: A critical race theory perspective. Review of Research in Education, 24(1), 211-247. doi: 10.3102/0091732x024001211Ledesma, M. C., & Calderón, D. (2015). Critical race theory in education: A review of past literature and a look to the future. Qualitative Inquiry, 21(3), 206-222. doi: 10.1177/1077800414557825

Leonardo, Z. (2016). Tropics of whiteness: Metaphor and the literary turn in white studies. Whiteness and Education, 1(1), 3-14. doi: 10.1080/23793406.2016.1167111

Milner, H. R. (2008). Critical race theory and interest convergence as analytic tools in teacher education policies and practices. Journal of Teacher Education, 59(4), 332-346. doi: 10.1177/0022487108321884

Picower, B. (2009). The unexamined whiteness of teaching: How White teachers maintain and enact dominant racial ideologies. Race Ethnicity and Education, 12(2), 197-215.

Sung, K. K. (2017). “Accentuate the positive; eliminate the negative”: Hegemonic interest convergence, racialization of Latino poverty, and the 1968 Bilingual Education Act. Peabody Journal of Education, 1-20. doi: 10.1080/0161956X.2017.1324657

Wideen, M., Mayer-Smith, J., & Moon, B. (1998). A critical analysis of the research on learning to teach: Making the case for an ecological perspective on inquiry. Review of Educational Research, 68(2), 130.

Wiedeman, C. R. (2002). Teacher preparation, social justice, equity: A review of the literature. Equity & Excellence in Education, 35(3), 200–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/713845323

Yosso, T., Villalpando, O., Delgado Bernal, D., & Solórzano, D. G. (2001, April 1). Critical race theory in Chicana/o education. Paper presented at the National Association for Chicana/Chicano Studies Annual Conference.

How to Cite

- Endnote/Zotero/Mendeley (RIS)

Education Review/Reseñas Educativas/Resenhas Educativas is supported by the Scholarly Communications Group at the Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College, Arizona State University. Copyright is retained by the first or sole author, who grants right of first publication to the Education Review . Readers are free to copy, display, distribute, and adapt this article, as long as the work is attributed to the author(s) and Education Review , the changes are identified, and the same license applies to the derivative work. More details of this Creative Commons license are available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/

All Education Review/Reseñas Educativas/Resenhas Educativas content from 1998-2020 and was published under an earlier Creative Commons license: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0

Education Review is a signatory to the Budapest Open Access Initiative.

ISSN: 1094-5296

- Español (España)

- Português (Brasil)

Make a Submission

Anped books for review.

Agosto 2024

Entrelaçando Pesquisas: História das Mulheres, gêneros e sexualidade

Orgs: Denize Sepulveda e Renan Corrêa

Mais informações e livros

Solicitar para revisão

Mais informações para chamada

Additional Information

Disclaimer: The views or opinions presented in book reviews are solely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent those of Education Review .

Education Review/Reseñas Educativas/Resenhas Educativas is supported by the Scholarly Communications Group at the Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College, Arizona State University.

Breadcrumbs Section. Click here to navigate to respective pages.

Handbook of Critical Race Theory in Education

DOI link for Handbook of Critical Race Theory in Education

Get Citation

This handbook illustrates how education scholars employ Critical Race Theory (CRT) as a framework to bring attention to issues of race and racism in education. It is the first authoritative reference work to provide a truly comprehensive description and analysis of the topic, from the defining conceptual principles of CRT in Law that gave shape to its radical underpinnings to the political and social implications of the field today. It is divided into six sections, covering innovations in educational research, policy and practice in both schools and in higher education, and the increasing interdisciplinary nature of critical race research. New chapters broaden the scope of theoretical lenses to include LatCrit, AsianCrit and Critical Race Feminism, as well as coverage of Discrit Studies, Research Methods, and other recent updates to the field. This handbook remains the definitive statement on the state of critical race theory in education and on its possibilities for the future.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapter | 5 pages, introduction, section section i | 83 pages, foundations of critical race theory and critical race theory in education, chapter 1 | 13 pages, the history and conceptual elements of critical race theory, chapter 2 | 10 pages, discerning critical moments, chapter 3 | 12 pages, critical race theory—what it is not, chapter 4 | 18 pages, critical race theory's intellectual roots, chapter 5 | 17 pages, w.e.b. du bois's contributions to critical race studies in education, chapter 6 | 11 pages, scholar activism in critical race theory in education, section section ii | 158 pages, intersectional frameworks, chapter 7 | 15 pages, chapter 8 | 17 pages, critical race theory offshoots, chapter 9 | 11 pages, the inclusion and representation of asian americans and pacific islanders in america's equity agenda in higher education, chapter 10 | 17 pages, examining black male identity through a prismed lens, chapter 11 | 13 pages, other kids' teachers, chapter 12 | 13 pages, the last plantation, chapter 13 | 12 pages, doing class in critical race analysis in education, chapter 14 | 12 pages, tribal critical race theory, chapter 15 | 18 pages, “straight, no chaser”, chapter 16 | 15 pages, utilities of counterstorytelling in exposing racism within higher education, chapter 17 | 13 pages, a discrit abolitionist imaginary, section section iii | 94 pages, methods/praxis, chapter 18 | 17 pages, blurring boundaries, chapter 19 | 11 pages, no longer just a qualitative methodology, chapter 20 | 17 pages, critical race quantitative intersectionality, chapter 21 | 12 pages, confronting our own complicity, chapter 22 | 13 pages, still “fightin' the devil 24/7”, chapter 23 | 9 pages, countering they schools, chapter 24 | 13 pages, critical race theory and education history, section section iv | 97 pages, critical race policy analysis, chapter 25 | 10 pages, the policy of inequity, chapter 26 | 9 pages, a call to “do justice”, chapter 27 | 15 pages, critical race theory, teacher education, and the “new” focus on racial justice, chapter 28 | 15 pages, let's be for real, chapter 29 | 10 pages, a critical race policy analysis of the school-to-prison pipeline for chicanos, chapter 30 | 13 pages, badges of inferiority, chapter 31 | 10 pages, racial failure normalized as correlational racism, chapter 32 | 13 pages, a movement in two acts.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Taylor & Francis Online

- Taylor & Francis Group

- Students/Researchers

- Librarians/Institutions

Connect with us

Registered in England & Wales No. 3099067 5 Howick Place | London | SW1P 1WG © 2024 Informa UK Limited

Derrick Bell’s Interest Convergence and the Permanence of Racism: A Reflection on Resistance

- Alexis Hoag

Nothing about this moment — COVID-19’s disproportionate impact on Black people, Trump’s explicit anti-Black racism , or the mass demonstrations following lethal police use of force against Black people — would have surprised Professor Derrick Bell. These fault lines are not new; rather, these events merely expose longstanding structural damage to the nation’s foundation. A central theme of Bell’s scholarship is the permanence and cyclical predictability of racism. He urged us to accept “the reality that we live in a society in which racism has been internalized and institutionalized,” a society that produced “a culture from whose inception racial discrimination has been a regulating force for maintaining stability and growth.” Bell would have also foreseen Trump’s presidency as the likely follow-up to eight years of the nation’s first Black President. Any amount of racial advancement, Bell argued , signified “temporary ‘peaks of progress,’ short-lived victories that slide into irrelevance as racial patterns adapt in ways that maintain white dominance.” In this reflection, I revisit Bell’s arguments, including his interest convergence theory , to provide clarity on the current moment and to reflect on the way his scholarship has impacted my work as a civil rights lawyer, scholar, and teacher.

I first encountered Professor Bell in 2005, as a student at New York University School of Law. By then, he had maintained a visiting professorship for nearly two decades in an arrangement made with his former student, NYU Law Dean and later University President, John Sexton . Bell’s legendary status as the father of Critical Race Theory and as a champion of faculty diversity was firmly ensconced. At the time, I was active in a student group demanding more faculty of color, and our group asked Bell for advice. Soft-spoken and impeccably dressed, he was surprisingly accessible. Bell was intimately aware of our concerns, having experienced them in nearly every professional space he had entered. His advice was gentle and encouraging, but decisive. With his support, we regularly staged silent protests before faculty meetings, lining the hallway armed with posters, as our professors walked past to vote on candidates. Bell likely sensed that staging the protests would be more beneficial for our development as social justice lawyers than for hiring more people of color for the faculty.

To the casual observer, Bell’s warmth, wit, and gentle demeanor belied his radical beliefs and scholarship. But what made his writings, actions, and teaching so effective was that Bell embodied all these qualities. As his student and teaching assistant in Constitutional Law, it was hard for me to reconcile what I perceived as pessimism and cynicism in his writings with the affable and charming professor presiding over the classroom. At first read, the ending of Space Traders made me shudder, but I could not deny the allegory’s accuracy in depicting the plight of Black people at the hands of white people in power; given the opportunity to access wealth, unlimited energy, and technological advances in exchange for Black people, white America made the trade. It is one of Bell’s many works to which I often turn, as I did last year when I transitioned to teaching law . And I frequently recommend it to my students.

Only after I started practicing did I cease seeing Bell as a pessimist and recognize him for what he was: a realist . Working on capital cases as an appellate defender in Tennessee, no federal judge wanted to acknowledge the gross racial disparities in death sentencing in a state where Black men convicted in a single county made up the largest subgroup on death row. The draconian rules of procedural default prevented these same clients from securing relief on otherwise meritorious claims of racial discrimination in jury selection. Later, as a lawyer at the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. ( LDF ), I inherited one of the Mississippi school desegregation cases that Bell filed with his colleagues Mel Leventhal and Marian Wright Edelman . Despite five decades of federal court monitoring, the public school district was still failing to adhere to the law established in Brown v. Board of Education . My colleagues and I reengaged members of the original plaintiff class, now grandparents of children enrolled in the same district. The district no longer operated a dual school system separated by race; instead, it operated a single, virtually all-Black, under-resourced school system that funneled children into the criminal legal system. In civil rights and the criminal legal system, I was fighting the same fight as my forebearers with similarly racist results.

So, as Bell posed , “Now what?”

For the answer, I turn to Bell’s theory of interest convergence: that the rights of Black people only advance when they converge with the interests of white people. Twenty-five years after the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of Education , Bell argued that the holding “cannot be understood without some consideration of the decision’s value to whites, not simply those concerned about the immorality of racial inequality, but also those whites in policymaking positions able to see the economic and political advances at home and abroad that would follow abandonment of segregation.” How else, Bell argued , could one account for the country’s “sudden shift . . . away from . . . separate but equal . . . towards a commitment to desegregation?” Then, the world was in the midst of the Cold War, and the nation’s hypocrisy in its treatment of Black people at home was not lost on our adversaries abroad.

It is through this lens that I view the actions that have transpired since George Floyd’s murder: the rapid passage of law enforcement reforms (that had previously stalled), swift actions and statements from corporations decrying anti-Black racism (from corporations that had previously denied it), and the sudden cross-racial embrace of “Black Lives Matter” (by white people who had previously resisted it). To be clear, my argument here largely applies to the sharp increase in (public) racial consciousness among white people. What has changed is not the legal, or even social status of Black people, but rather the social (media) acceptability of anti-Black racism. Said another way, it is now popular and financially advantageous to be anti-racist.

The popularity and profitability of anti-racism is nowhere more evident than on social media. With many Americans either out of work or working from home, we are all glued to pocket-sized screens. The hyper focus online created a higher stakes platform for the performance of protesting anti-Black racism. Social media enables users to measure the popularity and reach of each post. Yes, millions marched against anti-Black racism in cities and small towns across the nation, but these demonstrations were largely captured and shared via social media. Appearing at a Black Lives Matter demonstration showed solidarity, but appearing and then posting a photograph of it had measurable social currency. Consumer-driven corporations were all quick to showcase their anti-racist positions. Never mind that some of these corporations had engaged, or continue to engage, in anti-Black practices . Although retail spending decreased during the pandemic, companies could not possibly lose more money speaking out against racism, but they could by remaining silent, or worse, condoning racism .

I argue that a major motivating factor for many white peoples’ actions and corporations’ pronouncements against racism was not to advance Black equality. Rather, it was the realization that the nation cannot maintain its economic, political, and social superiority over the rest of the world while remaining silent about anti-Black racism in America. Racism is a bad look. Silence in the wake of racist events is even worse. And just as in the 1950s, the world is watching America. Only now, the world is consuming America’s hypocrisy in real time on social media. Instead of America decrying human rights abuses across the globe, the globe is protesting human rights abuses in America. We all witnessed the responses: Democratic members of Congress donned West African kente cloth to announce their police reform bill, later kneeling in long-belated solidarity with Colin Kaepernick. Broadcast from the Rose Garden, Trump gave lip service to the experiences of Black people at the hands of law enforcement. Quaker Oats changed the name and image of its Aunt Jemima brand. NASCAR prohibited confederate flags from its events and properties. All abrupt, performative displays of wokeness, despite prior unanswered complaints of anti-Black racism.

And lest we forget, just a few years ago many white people responded with distaste and hostility to the expression “Black lives matter” following the murders of Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown. With earnestness, well-meaning white people asked , “don’t all lives matter”? Yet, here we are, roughly six years later, witnessing millions of people posting black squares on their Instagram accounts with long captions or simple hashtags denouncing anti-Black racism. Again, these were largely white people. I observed many of my Black peers posting variations of: “I’m tired” or nothing at all. On my bike rides and runs through New York City, whenever I pass wealthy, white enclaves I frequently observe signs in windows or draped flags adorned with the words: “Black Lives Matter” and “White Silence is Violence.” Where were these signs when New York City police officers fatally shot Amadou Diallo, unarmed and standing in the doorway of his home, 41 times?

Will this moral posturing online translate into substantive changes in the law and in society for Black people? It was lost on no one that police used excessive force on Black people protesting excessive police force against Black people. Law enforcement officials murdered Rayshard Brooks on camera weeks after officers murdered George Floyd, his death also captured on camera. Officials have not yet arrested the officers who murdered Breonna Taylor. The wave of police reforms is not insignificant, but when we closely examine these measures, they fail to provide paths to redress for Black victims of excessive police force or even address the practices that result in a disproportionate use of force against Black people. For that, we would need to eradicate the presumption of criminality and dangerousness that society assigns Black people. But according to Bell, that is unlikely because “white people desperately need[] . . . black people — or most blacks — in a subordinate status in order to sustain . . . the . . . preferential treatment to which every white person is granted…”

Bell warned us that “yearning for racial equality is fantasy.” There is no vaccine for America’s illness. Like Bell, I do not believe we can eradicate racism from a nation built and dependent upon it. The subordination of Black people provides “whites with a comforting sense of their position in society. . . whether or not [white people] want it.” But this acknowledgment does not mean we should abandon the fight to challenge the racial hierarchy.

To counter the permanence of racism, Professor Bell advocated that our fight against it must be equally persistent. He implored us to “realize with our slave forbearers that the struggle for freedom is, at bottom, a manifestation of our humanity that survives and grows stronger through resistance to oppression even if that oppression is never overcome.” Although many of my death-sentenced clients — now represented by successor counsel — still await rulings from federal judges, there was nevertheless something meaningful about the process of post-conviction litigation. For many of my clients, the work my team and I performed on their behalves enabled them for the first time to feel listened to, heard, and seen. In investigating and presenting their habeas claims, we told their stories and elevated their humanity. The collective effort reminded our clients that their lives have value. Later, while working for LDF, I encountered an older woman in Meridian, Mississippi. She had grandchildren enrolled in the same school district as her children were during the desegregation litigation Bell initiated. She recalled that the white townspeople threatened to kill her and her children if she got involved in the lawsuit. This was no idle threat: James Chaney had been teaching her children to read when he was lynched during Freedom Summer. I asked why she nevertheless agreed to put her name on the lawsuit. She responded: “At least I’d die fighting with my babies.” Sometimes, the whole point is to resist. Professor Bell was a brilliant scholar, activist, and civil rights litigator, but he was also an exceptional teacher and mentor. He gifted me with the knowledge that there is power in amplifying the voices and experiences of those most impacted by racial inequality. And although I may not see the change for which I advocate, there is value in the struggle against oppression. I will continue to bear witness, amplify stories of injustice, and encourage my students to do the same.

More from the Blog

Toward effectuating the right to vote from jail.

Assemb. B. 286, 82nd Sess. (Nev. 2023)

- Jackie O'Neil

Enforceable Ethics for the Supreme Court

The anti-regulation quartet and internationally informed regulation.

- Elena Chachko

- Permissions

- New Releases

- Browse Books

- Upcoming Events

- ERS Overview

- PAS & BAS

- Foreign Language Editions

- Purchase orders

- For Customers

- For Authors

- For Booksellers

- For Librarians

- Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies Series

- Disability, Culture, and Equity Series

- Early Childhood Education Series

- International Perspectives on Education Reform Series

- Language and Literacy Series

- Multicultural Education Series

- Practitioner Inquiry Series

- Research and Practice in Social Studies Series

- School : Questions

- Speculative Education Approaches Series

- Spaces In-between Series

- STEM for Our Youngest Learners Series

- Teaching for Social Justice Series

- Technology, Education—Connections

- Visions of Practice Series

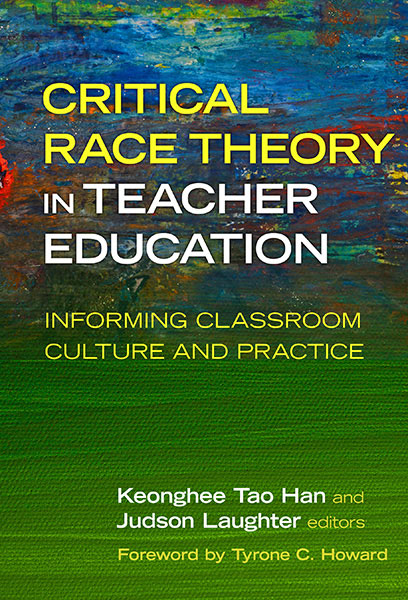

Critical Race Theory in Teacher Education

Informing classroom culture and practice.

Edited by: Keonghee Tao Han , Judson Laughter

Foreword by: Tyrone C. Howard

Publication Date: March 22, 2019

Available Formats

- Description

Description +

This important volume promotes the widespread application of Critical Race Theory (CRT) to better prepare K–12 teachers to bring an informed asset-based approach to teaching today’s highly diverse populations. Part I explores the tradition and longevity of CRT in teacher education. Part II, “Beyond Black and White,” expands CRT into new contexts, including LatCrit, AsianCrit, TribalCrit, QueerCrit, and BlackCrit. Part III looks beyond CRT to other epistemologies often dismissed in White conceptions of teacher preparation. Throughout the text, the authors collaborate across demographic lines to work together toward social justice and compassion. A closing chapter presents and synthesizes the lessons to be learned for teacher educators who want to prepare teachers to be agents of social change.

Book Features:

- Presents the history and theory of CRT and its applications to education and teacher preparation.

- Moves beyond a Black/White binary to consider applications of CRT across various groups, contexts, and identities in the U.S.

- Expands CRT to include Indigenous epistemologies from a global context.

Keonghee Tao Han is an associate professor at the University of Wyoming. Judson Laughter is an associate professor of English education at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

“The authors present foundational knowledge that teachers must have before they are able to incorporate transformative social justice concepts in their curricula.“

—Teachers College Record

“ Critical Race Theory in Teacher Education has put forth a challenge that requires all of our attentions. Not only does this work have important implications for teaching and learning in schools, it provides an epistemological and moral call for us to do justice work with a global framework that captures, reclaims, and restores our humanity.” —From the Foreword by Tyrone C. Howard , Graduate School of Education and Information Studies, The University of California, Los Angeles

“Han and Laughter have assembled an amazing group of scholars and practitioners merging the fields of Critical Race Theory and teacher education. This original work has taken us down some important pathways as we train educators to serve all communities and communities of color in particular. This is a remarkable, compelling, and insightful book.” — Daniel Solorzano , Graduate School of Education and Information Studies, The University of California, Los Angeles

Foreword by Tyrone C. Howard

Chapter 1. Introduction and Overview Judson Laughter and Keonghee Tao Han

PART I: CRT AND TEACHER EDUCATION

Chapter 2. Race, Violence, and Teacher Education: An Overview of Critical Race Theory in Teacher Education DaVonna Graham, Adam Alvarez, Derric Heck, Jawanza Rand, and Rich Milner

Chapter 3. Teacher Education, Diversity, and the Interest Convergence Conundrum: How the Demographic Divide Shapes Teacher Education Ashlee Anderson and Brittany Aronson

Chapter 4. "I See Whiteness": The Sixth Sense of Teacher Education Cheryl Matias and Jared Aldern

Chapter 5. Racial Literacy: Ebony and Ivory Perspectives of Race in Two Graduate Courses Rebecca Rogers and Gwen McMillon

PART II: BEYOND BLACK AND WHITE

Chapter 6. Latino Critical Race Theory (LatCrit): A Historical and Compatible Journey from Legal Scholarship to Teacher Education Rachel Salas

Chapter 7. Exploring Asian American Invisibility in Teacher Education: The AsianCrit Account Keonghee Tao Han

Chapter 8. Tribal Critical Race Theory Angela Jaime and Caskey Russell

Chapter 9. Queer Theory: QueerCrit Eric Teman

Chapter 10. The Normalization of Anti-Blackness in Teacher Education: A Call for Critical Race Frameworks Andrew Torres and Lamar Johnson

PART III: BEYOND CRT

Chapter 11. Ghanaian Epistemology in Teacher Education Adeline Borti

Chapter 12. Working Within a Contact Zone to Explore Indigenous Fijian Epistemology Cynthia Brock, Pauline Harris, and Ufemia Camaitoga

Chapter 13. Kenya's Education: An Eclectic Epistemological Collage Lydiah Nganga and John Kambutu

Chapter 14. Confucian Epistemology and Its Implications for Teacher Education Qi Sun and Reed Scull

Chapter 15. Critical Race Theory and Teacher Education: Toward Compassionate Coalitions for the Future? Andrew Peterson and Rob Hattam

About the Contributors

Professors: Request an Exam Copy

Print copies available for US orders only. For orders outside the US, see our international distributors .

Teaching About Race Is Good, Actually. States Need to Stop Banning It.

By Ian Wright

In this back to school season, millions of American students are returning to classrooms where the wrong course, lesson, or textbook can lead to deep trouble. Why? Because for the last several years, conservative activists and lawmakers have been waging a crusade against “critical race theory,” or CRT.

Critical race theory is an academic concept acknowledging that racism isn’t simply the result of individual prejudice but is also embedded in our institutions through laws, regulations, and rules.

As school districts have emphasized , it’s a higher education concept rarely taught in K-12 schools. But cynical activists have used CRT as a catch-all term to target a broad range of diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives — and seemingly any discussion about race and racism in the classroom.

Since January 2021, 44 states have “introduced bills or taken other steps that would restrict teaching critical race theory or limit how teachers can discuss racism and sexism,” according to Education Weekly . And as of this writing, UCLA has identified 807 anti-CRT “bills, resolutions, executive orders, opinion letters, statements, and other measures” since September 2020.

Critics claim — falsely — that CRT teaches that all white people are oppressors, while Black people are simply oppressed victims. Many opponents claim it teaches white students to “hate their own race,” or to feel guilty about events that happened before they were born.

In reality, CRT gives students of every race the tools to understand how our institutions treat people of different races unequally — and how we can make those systems fairer. That’s learning students of every race would be better off with.

But instead, this barrage of draconian legislation is having a chilling effect on speech in the classroom.

In 2022, Florida passed the “ Stop W.O.K.E. Act ,” which prohibits teaching that could lead to a student feeling “discomfort” because of their race, sex, or nationality. But the law’s vague language makes it difficult for educators to determine what they can or cannot teach, ultimately restricting classroom instruction. In my home state of Texas, SB3 similarly restricts these classroom discussions.

Running afoul of these laws can get teachers and school administrators in trouble. As a result of this hostile environment, the RAND Corporation found that two-thirds of K-12 school teachers have decided “to limit instruction about political and social issues in the classroom.”

Notably, this self-censorship extends beyond states with such policies: 55 percent of teachers without state or local restrictions on CRT have still decided to limit classroom discussions of race and history.

As a student, I find this distressing.

My high school history classes gave me a much richer understanding of race in our history, especially the discussions we had at the height of the Black Lives Matter protests. And in college, I’ve gotten to learn about racial inequalities in everything from housing and real estate to health care, politics, education, and immigration policy.

As a person of color, I can’t imagine where I’d be without this understanding. Neither white students nor students of color will benefit from laws designed to censor their understanding of history, critical thinking, and open dialogue in the classroom.

The fight against CRT is a fight against the principles of education that encourage us to question, learn, and grow. Rather than shielding students from uncomfortable truths, which they can certainly handle, we should seek to equip them with the knowledge to navigate the world, think critically about our history and institutions, and push for a more inclusive country.

Originally in OtherWords .

For press inquiries, contact IPS Deputy Communications Director Olivia Alperstein at (202) 704-9011 or [email protected] . For recent press statements, visit our Press page .

Subscribe to our newsletter

Further reading, netanyahu is threatening regional war to save his career, america's nuclear 'downwinders' deserve justice, the olympic refugee team was an inspiration — and also a tragedy, our project sites.

Interest Convergence: Definition and Examples

Viktoriya Sus (MA)

Viktoriya Sus is an academic writer specializing mainly in economics and business from Ukraine. She holds a Master’s degree in International Business from Lviv National University and has more than 6 years of experience writing for different clients. Viktoriya is passionate about researching the latest trends in economics and business. However, she also loves to explore different topics such as psychology, philosophy, and more.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Chris Drew (PhD)

This article was peer-reviewed and edited by Chris Drew (PhD). The review process on Helpful Professor involves having a PhD level expert fact check, edit, and contribute to articles. Reviewers ensure all content reflects expert academic consensus and is backed up with reference to academic studies. Dr. Drew has published over 20 academic articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education and holds a PhD in Education from ACU.

Interest convergence is a concept developed by Derrick Bell that describes the idea that progress toward racial equality only occurs when the interests of dominant and subordinate groups converge.

In other words, positive change for marginalized communities only happens when it benefits those in power as well.

For instance, we can examine the emergence of affirmative action policies in universities and workplaces. Many universities started implementing affirmative action policies after pressure from student protests and civil rights organizations, or, when it becomes of marketing benefit to do so.

Employment-based affirmative actions are often introduced to increase workplace diversity but also to improve public relations for businesses seeking a positive reputation among an increasingly diverse social and consumer base.

Overall, interest convergence theory suggests that marginalized communities can’t rely solely on morality or appeals to justice for equal rights without convincing those with more power on how it benefits that dominant group directly.

Definition of Interest Convergence

“Interest convergence” is a term used primarily within critical race theory to describe how progress toward racial justice tends to occur only when it aligns with the interests of dominant groups.

Interest convergence is not a term commonly used in scientific research, but rather it is a sociological concept introduced by Derrick Bell and used extensively within cultural, critical and sociological theories .

He argues that interest convergence is a phenomenon where dominant groups tend to support initiatives that promote equality and justice only when it benefits their own self-interests, making their allyship a relatively selfish action (Shih, 2017).

Milner (2008) adds that:

“…interest convergence stresses that racial equality and equity for people of color will be pursued and advanced when they converge with the interests, needs, expectations, and ideologies of Whites” (p. 333).

Interest convergence is a concept based on social identity theory as well as critical race theory. If people strongly identify with a certain group, they tend to support policies and actions to benefit that group (Unbound & Driver, 2011).

It can be seen in everything from grassroots campaigns by workers’ unions fighting for better wages and benefits to efforts by LGBTQ+ advocates to secure equal rights under the law.

They are more likely to support societal goals and identity acceptance that bring personal benefits, such as higher wages for workers through affirmative actions based on employment, if these align with their group interests.

10 Examples of Interest Convergence

- Sponsoring a pride parade : A corporation sponsoring a pride parade to portray itself as an inclusive and diverse company while also targeting the LGBTQ+ market. By targeting this demographic and positioning itself as a supporter of diversity and inclusion , the corporation increases its likelihood of obtaining new business and generating revenue.

- Introducing diversity & inclusion programs : Employers introduce diversity and inclusion training in the workplace to improve morale and productivity while also preventing potential lawsuits related to discrimination. These initiatives benefit both employees, who are more likely to feel valued in a diverse workplace, and employers who minimize their risk of legal action from employees who feel discriminated against.

- Offering halal products : A grocery store is offering halal products to attract Muslim customers and increase profits. This practice benefits both the store (through increased profits) and Muslim customers (having greater availability of their dietary required products).

- Suggesting grants : Universities offer scholarships and grants for students from underrepresented communities to fulfill diversity quotas while improving their college rankings. This example demonstrates how universities utilize interest convergence by fulfilling their social responsibility toward promoting diversity while benefiting themselves through positive press coverage.

- Adopting eco-friendly practices : Businesses choose eco-friendly practices not only due to environmental concerns but because they attract customers who prioritize sustainability in their purchasing decisions. These active measures give value to the cause while evolving consumer tendencies towards consumption choices in market economies.

- Gaining political support : Political candidates adopt positions on social issues that align with popular opinion as a means of gaining support during elections. By adapting to popular social trends, politicians use interest convergence as a means of generating greater public appeal relative to one’s competitors.

- Producing content with non-white actors : A movie studio is producing content featuring predominantly non-white actors for greater representation while also catering to diverse global markets where this demographic is prominent. This example highlights how media corporations can utilize interest convergence by fulfilling societal sentiments and earning profit through cross-border movie sales.

- Investing in public transport : Cities are investing in public transportation not only for environmental reasons but also because it can spur economic growth by providing more efficient access for workers without cars and drive-creating more buyers for local businesses near stations. Here, cities actively promote public transport initiatives not only for urban development purposes and reducing traffic congestion but also to position themselves as eco-friendly whilst generating economic opportunities.

- Promoting health initiatives : Corporations promote health initiatives such as gym discounts and healthy food options (such as salads) for employees’ physical well-being because various studies have demonstrated that healthy employees are more productive. This example presents how healthy initiatives further contribute to employee retention and job satisfaction, thereby increasing corporate profits.

- Introducing flexible working hours : An organization introduces flexible work schedules not only to accommodate employees’ work-life balance but also because studies show that flexibility increases employee satisfaction. Happier staff members tend to stick around longer, reducing the organization’s need for expensive recruitment, hiring & training of new personnel.

Fact File: Derrick Bell’s Contribution

Derrick Bell (2004) , a prominent legal scholar, and civil rights activist, developed the concept of interest convergence in the context of his work on critical race theory.

Bell (2004) was concerned with understanding how legal institutions perpetuate racial inequalities in society, and he saw interest convergence as a way to explain why some changes occur while others do not.

Bell (2004) argued that interest convergence emerged historically because dominant groups mainly sought self-interest when supporting policies that benefited marginalized communities.

He believed that white Americans often only supported policies to advance racial equality if they also promoted economic or other benefits for themselves (Bell, 2004).

Bell’s (2004) interest in convergence theory was influenced by his experiences working as an attorney for organizations trying to promote equal-opportunity legislation during the Civil Rights Movement era of the 1960s.

During this period, many white Americans opposed legislation like Affirmative Action without any tangible benefit to them.

This is why workplace diversity through affirmative action has been botched by employers running poorly performed diversity programs- rather than creating safe environments where employees can truly thrive.

From this, Bell (2004) understood that progress towards achieving social justice in America required a broader recognition by those with political power and economic resources.

Overall, Bell’s concept of interest convergence originated from observations of how dominant interests affect reform efforts while recognizing the importance of shared interests across different groups as an additional driving force toward social change .

3 Case Study Examples

1. brown vs. board of education.

Interest convergence played a significant role in the landmark Brown vs. Board of Education decision of 1954 that declared racial segregation unconstitutional (Bell, 2004).

While many civil rights activists pushed for desegregation because they believed it was inherently unjust, legal scholar Derrick Bell (2004) argued that progress towards desegregation would only occur when it aligned with the interests of white Americans.

White Americans were motivated to support integrated schools to win international approval and counter the propaganda efforts of nations advocating against racial discrimination.

Through this motivation, white Americans came to believe that a racially integrated society would be necessary to establish America’s global authority and reputation.

2. Voting Rights Act of 1965

Signed in 1965 by President Lyndon B. Johnson, the Voting Rights Act prohibited states from imposing discriminatory voting laws or practices to prevent African Americans from exercising the electoral power they were legally entitled to (Ray, 2022).

The Voting Rights Act is a clear example of interest convergence in action.

Many progressive White Americans were concerned that the ongoing disenfranchisement of minority groups could potentially destabilize the political system in the United States.

Additionally, they recognized that granting voting rights to historically deprived communities, such as young people and Latinos who tend to vote for the Democratic party, could yield significant advantages (Ray, 2022).

As a result, these progressive Whites supported legislation to expand voting rights, even though it went beyond just addressing blatant discrimination.

3. Immigration Reform Act (IRCA) of 1986

The IRCA was signed by President Ronald Reagan because it provided advantages for various groups and addressed issues related to undocumented immigrants that were then being framed as directly damaging to US interests.

The Law granted amnesty for millions of undocumented immigrants already residing in the US but also contained provisions establishing tighter controls on future immigration (Golash-Boza, 2015).

Politically groups with economically-similar interests (e.g., White farmers and immigrant farm workers) lobbied for support despite vehement disagreements.

It is argued that the IRCA represented a critical agreement between ethnic, racial, and class interests to ensure a working solution could benefit the individual and the larger society, thus illustrating interest convergence (Golash-Boza, 2015).

So, this law allowed different groups to put aside their differences, recognize common interests and unite for a greater cause.

Interest convergence is a concept introduced by legal scholar Derrick Bell that highlights the importance of shared interests and mutual benefits in promoting social justice.

Throughout history, we have seen how marginalized communities like African Americans and minorities have struggled to realize their goals without forming coalitions with individuals or groups in positions of privilege.

To achieve progress, it becomes essential for disadvantaged groups to showcase how their aims are aligned with the interests of influential people or organizations who tend only to act when it serves themselves.

Only then do they stand a chance at gaining much-needed help toward achieving equality and justice.

Understanding the principles of interest convergence helps us recognize opportunities for collaboration and coalition-building between different social groups to achieve progress toward equity and inclusion.

Bell, D. A. (2004). Silent covenants: Brown v. Board of Education and the unfulfilled hopes for racial reform . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Golash-Boza, T. M. (2015). Immigration nation . New York: Routledge.

Milner, H. R. (2008). Critical race theory and interest convergence as analytic tools in teacher education policies and practices. Journal of Teacher Education , 59 (4), 332–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487108321884

Ray, V. (2022). On critical race theory: Why it matters & why you should care . New York: Random House.

Shih, D. (2017, April 19). A theory to better understand diversity, and who really benefits . NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2017/04/19/523563345/a-theory-to-better-understand-diversity-and-who-really-benefits

Unbound, C., & Driver, J. (2011). Rethinking the interest-convergence thesis. Northwestern University Law Review , 105 (1), 149–197. https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=6036&context=journal_articles&httpsredir=1&referer=

- Viktoriya Sus (MA) #molongui-disabled-link Cognitive Dissonance Theory: Examples and Definition

- Viktoriya Sus (MA) #molongui-disabled-link 15 Free Enterprise Examples

- Viktoriya Sus (MA) #molongui-disabled-link 21 Sunk Costs Examples (The Fallacy Explained)

- Viktoriya Sus (MA) #molongui-disabled-link Price Floor: 15 Examples & Definition

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 23 Achieved Status Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Ableism Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 25 Defense Mechanisms Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Theory of Planned Behavior Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

IMAGES

COMMENTS

In this chapter, we discuss Bell's (1980) interest convergence, a key concept in critical race theory,1 as a useful analytic and strategic tool to analyze, critique, make sense of, and reform sites in teacher education that we argue should be studied and interrogated to improve policies and practices in the field. The tenet "interest convergence" originated with the work of

In The Report of the AERA Panel on Research and Teacher Education, Cochran-Smith and Zeichner's (2005) review of studies in the field of teacher education revealed that many studies lacked theoretical and conceptual grounding.The author argues that Derrick Bell's (1980) interest convergence, a principle of critical race theory, can be used as an analytic, explanatory, and conceptual tool in ...

Seeking Support in Teacher Education for Racial Knowledge: The Role of Professional Networks and Social Identities. Drawing from the narrated experiences of teacher educators (TEs) at different institutions, this paper analyzes TEs' perceptions of support related to their work in teaching about race and racism.….

Abstract. This article uses three tenets of critical race theory to critique the common pattern of teacher education focusing on preparing predominantly White cohorts of teacher candidates for racially and ethnically diverse students. The tenet of interest convergence asks how White interests are served through incremental steps.

Critical race theory and interest convergence as analytic tools in teacher education policies and practices. Journal of Teacher Education, 59(4), 332-346. Crossref. Web of Science. ... Black feminist thought in education, (b) fostering critical race approaches to teacher education, and (c) challenging global anti-Black racism in education ...

Request PDF | Critical Race Theory and Interest Convergence as Analytic Tools in Teacher Education Policies and Practices | In The Report of the AERA Panel on Research and Teacher Education ...

Critical Race Theory and Interest Convergence as Analytic Tools in Teacher Education Policies and Practices. Milner, H. Richard, IV. Journal of Teacher Education, v59 n4 p332-346 2008. ... applies the interest-convergence principle to teacher education, and introduces an evolving theory of disruptive movement in teacher education to fight ...

The tenets of interest convergence and permanence of racism are examined in the ... Critical Race Theory in Teacher Education Discussions of race and racism are not highly emphasized in teacher education nor the preparation of teacher educators (Quaye, 2014). Over the past decade, many teacher

daily basis, Critical Race Theory is the one movement within academe. that unapologetically and relentlessly makes the study of race its primary. focus. When a theorist is faced with an issue in which racial attitudes. play a role, the analyst responds by fully exploring how race functions in that particular context.

It is divided into three sections, covering innovations in educational research, policy and practice in both schools and in higher education, and the increasing interdisciplinary nature of critical race research. With 28 newly commissioned pieces written by the most renowned scholars in the field, this handbook provides the definitive statement ...

In this chapter, we discuss Bell's (1980) interest convergence, a key concept in critical race theory,1 as a useful analytic and strategic tool to analyze, critique, make sense of, and reform sites in teacher education that we argue should be studied and interrogated to improve policies and practices in the field. The tenet "interest ...

In this article, Bell outlines the concept of interest convergence, an idea that has since become vital to Critical Race Theory, through an analysis of the Brown v. Board of Education decision. Interest convergence has proven to be a useful tool in understanding how historical racial reforms are achieved. Here, Bell argues that, though popular ...

1995), and I argue, to a degree, under-theorized in teacher education; (b) critical race theory—and in particular interest convergence1—may be a useful tool to analyze policy and practice in teacher education; and (c) the lack of theoretical framing in teacher education is, to some degree, an epistemological issue as much as a conceptual one.

By deploying several concepts central to critical race theory, as well as critiques that note the shortcomings of past attempts at racial reform (Brown v. ... (1980). Brown v. Board of Education and the interest convergence dilemma. Harvard Law Review, 93, 518—533. Crossref. Google Scholar. Bell D. A. (2004). ... Developing cultural critical ...

In The Report of the AERA Panel on Research and Teacher Education, Cochran-Smith and Zeichner's (2005) review of studies in the field of teacher education revealed that many studies lacked theoretical and conceptual grounding. The author argues that Derrick Bell's (1980) interest convergence, a principle of critical race theory, can be used as an analytic, explanatory, and conceptual tool in ...

Vanderbilt University - Cited by 19,896 - teacher education - urban education - race - social context of education - English Education ... Critical race theory and interest convergence as analytic tools in teacher education policies and practices. HR Milner IV. Journal of teacher education 59 (4 ...

Critical race theory and interest convergence as analytic tools in teacher education policies and practices. Journal of Teacher Education, 59(4), 332-346. doi: 10.1177/0022487108321884 . Picower, B. (2009). The unexamined whiteness of teaching: How White teachers maintain and enact dominant racial ideologies. Race Ethnicity and Education, 12(2 ...

Board of Education and the Interest-Convergence Dilemma. Derrick A. Bell Jr. Download. In the lead up to Volume 134, the Harvard Law Review republished five classic Critical Race Theory articles from our archives. This is the second piece in our series. The full version of this Comment may be found by clicking on the PDF link below. After Brown v.

This handbook illustrates how education scholars employ Critical Race Theory (CRT) as a framework to bring attention to issues of race and racism in education. ... The Convergence of Dead Prez and The Matrix as a Method of Promoting a Critical Conscious Intellectualism in the Social Justice Education Project/Tucson's Mexican American/Raza ...

This article examines the development of Critical Race Theory (CRT) in education, paying attention to how researchers use CRT (and its branches) in the study of K-12 and higher education. ... Brown vs. Board of Education and the interest-convergence principle. Harvard Law Review, 93, 518-533 ... Evans-Winters V., Twyman Hoff P. (2011). The ...

In this reflection, I revisit Bell's arguments, including his interest convergence theory, to provide clarity on the current moment and to reflect on the way his scholarship has impacted my work as a civil rights lawyer, scholar, and teacher. I first encountered Professor Bell in 2005, as a student at New York University School of Law.

Race, Violence, and Teacher Education: An Overview of Critical Race Theory in Teacher Education DaVonna Graham, Adam Alvarez, Derric Heck, Jawanza Rand, and Rich Milner ... and the Interest Convergence Conundrum: How the Demographic Divide Shapes Teacher Education Ashlee Anderson and Brittany Aronson. Chapter 4. "I See Whiteness": The Sixth ...

But cynical activists have used CRT as a catch-all term to target a broad range of diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives — and seemingly any discussion about race and racism in the classroom. Since January 2021, 44 states have "introduced bills or taken other steps that would restrict teaching critical race theory or limit how ...

Definition of Interest Convergence. "Interest convergence" is a term used primarily within critical race theory to describe how progress toward racial justice tends to occur only when it aligns with the interests of dominant groups. Interest convergence is not a term commonly used in scientific research, but rather it is a sociological ...