Research Design Review

A discussion of qualitative & quantitative research design, the use of quotes & bringing transparency to qualitative analysis.

“An overemphasis on the researcher’s interpretations at the cost of participant quotes will leave the reader in doubt as to just where the interpretations came from [however] an excess of quotes will cause the reader to become lost in the morass of stories.” (Morrow, 2005, p. 256)

By embedding carefully chosen extracts from participants’ words in the final document, the researcher uniquely gives participants a voice in the outcomes while contributing to the credibility – and transparency – of the research. In essence, the use of verbatims gives the users of the research a peek into the analyst’s codebook by illustrating how codes associated with particular categories or themes in the data were defined during the analysis process.

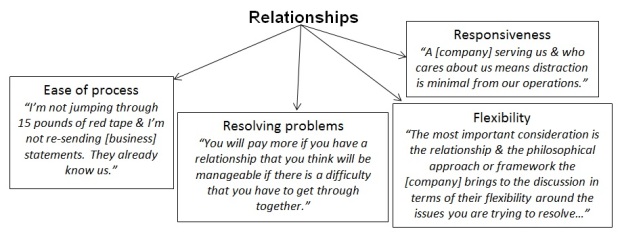

As an example, the analysis of data from a recent in-depth interview study among business decision makers determined that the broad concept of “relationships” was a critical factor to driving certain types of decisions. That alone is not a useful finding; however, the analysis of data within this category uncovered themes that effectively gave definition to the “relationships” concept. As shown below, the definitional themes, in conjunction with illustrative quotes from participants, give the reader a concise and useful understanding of “relationships.”

In this way, quotes contribute much-needed transparency to the analytical process. As discussed elsewhere in Research Design Review (e.g., see this April 2017 article ), transparency in the final document is built around “thick description,” defined as “a complete account…of the phenomena under investigation as well as the rich details of the data collection and analysis processes and interpretations of the findings” (Roller & Lavrakas, 2015, p. 363). One of the ingredients in a thick description of the analytical process is the details of code development and the coding procedures. The utilization of verbatims from participants in the final report adds to the researcher’s thick description (and transparency) by helping to convey the researcher’s thinking during data analysis and how that thinking steered the creation and application of codes.

Morrow, S. L. (2005). Quality and trustworthiness in qualitative research in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology , 52 (2), 250–260. http://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.250

Roller, M. R., & Lavrakas, P. J. (2015). Applied qualitative research design: A total quality framework approach . New York: Guilford Press.

Image captured from: https://cdmginc.com/testing-corner-quotation-marks-add-power/

Share this:

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Pingback: Qualitative Data Analysis: 16 Articles on Process & Method | Research Design Review

A good reference, as well as making a good point about the integration and grounding of the participant’s voice with the researcher’s/ evaluator’s interpretations and recommendations. This exemplfies the strentgh of a qualitative approach!

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Can J Hosp Pharm

- v.67(6); Nov-Dec 2014

Qualitative Research: Getting Started

Introduction.

As scientifically trained clinicians, pharmacists may be more familiar and comfortable with the concept of quantitative rather than qualitative research. Quantitative research can be defined as “the means for testing objective theories by examining the relationship among variables which in turn can be measured so that numbered data can be analyzed using statistical procedures”. 1 Pharmacists may have used such methods to carry out audits or surveys within their own practice settings; if so, they may have had a sense of “something missing” from their data. What is missing from quantitative research methods is the voice of the participant. In a quantitative study, large amounts of data can be collected about the number of people who hold certain attitudes toward their health and health care, but what qualitative study tells us is why people have thoughts and feelings that might affect the way they respond to that care and how it is given (in this way, qualitative and quantitative data are frequently complementary). Possibly the most important point about qualitative research is that its practitioners do not seek to generalize their findings to a wider population. Rather, they attempt to find examples of behaviour, to clarify the thoughts and feelings of study participants, and to interpret participants’ experiences of the phenomena of interest, in order to find explanations for human behaviour in a given context.

WHAT IS QUALITATIVE RESEARCH?

Much of the work of clinicians (including pharmacists) takes place within a social, clinical, or interpersonal context where statistical procedures and numeric data may be insufficient to capture how patients and health care professionals feel about patients’ care. Qualitative research involves asking participants about their experiences of things that happen in their lives. It enables researchers to obtain insights into what it feels like to be another person and to understand the world as another experiences it.

Qualitative research was historically employed in fields such as sociology, history, and anthropology. 2 Miles and Huberman 2 said that qualitative data “are a source of well-grounded, rich descriptions and explanations of processes in identifiable local contexts. With qualitative data one can preserve chronological flow, see precisely which events lead to which consequences, and derive fruitful explanations.” Qualitative methods are concerned with how human behaviour can be explained, within the framework of the social structures in which that behaviour takes place. 3 So, in the context of health care, and hospital pharmacy in particular, researchers can, for example, explore how patients feel about their care, about their medicines, or indeed about “being a patient”.

THE IMPORTANCE OF METHODOLOGY

Smith 4 has described methodology as the “explanation of the approach, methods and procedures with some justification for their selection.” It is essential that researchers have robust theories that underpin the way they conduct their research—this is called “methodology”. It is also important for researchers to have a thorough understanding of various methodologies, to ensure alignment between their own positionality (i.e., bias or stance), research questions, and objectives. Clinicians may express reservations about the value or impact of qualitative research, given their perceptions that it is inherently subjective or biased, that it does not seek to be reproducible across different contexts, and that it does not produce generalizable findings. Other clinicians may express nervousness or hesitation about using qualitative methods, claiming that their previous “scientific” training and experience have not prepared them for the ambiguity and interpretative nature of qualitative data analysis. In both cases, these clinicians are depriving themselves of opportunities to understand complex or ambiguous situations, phenomena, or processes in a different way.

Qualitative researchers generally begin their work by recognizing that the position (or world view) of the researcher exerts an enormous influence on the entire research enterprise. Whether explicitly understood and acknowledged or not, this world view shapes the way in which research questions are raised and framed, methods selected, data collected and analyzed, and results reported. 5 A broad range of different methods and methodologies are available within the qualitative tradition, and no single review paper can adequately capture the depth and nuance of these diverse options. Here, given space constraints, we highlight certain options for illustrative purposes only, emphasizing that they are only a sample of what may be available to you as a prospective qualitative researcher. We encourage you to continue your own study of this area to identify methods and methodologies suitable to your questions and needs, beyond those highlighted here.

The following are some of the methodologies commonly used in qualitative research:

- Ethnography generally involves researchers directly observing participants in their natural environments over time. A key feature of ethnography is the fact that natural settings, unadapted for the researchers’ interests, are used. In ethnography, the natural setting or environment is as important as the participants, and such methods have the advantage of explicitly acknowledging that, in the real world, environmental constraints and context influence behaviours and outcomes. 6 An example of ethnographic research in pharmacy might involve observations to determine how pharmacists integrate into family health teams. Such a study would also include collection of documents about participants’ lives from the participants themselves and field notes from the researcher. 7

- Grounded theory, first described by Glaser and Strauss in 1967, 8 is a framework for qualitative research that suggests that theory must derive from data, unlike other forms of research, which suggest that data should be used to test theory. Grounded theory may be particularly valuable when little or nothing is known or understood about a problem, situation, or context, and any attempt to start with a hypothesis or theory would be conjecture at best. 9 An example of the use of grounded theory in hospital pharmacy might be to determine potential roles for pharmacists in a new or underserviced clinical area. As with other qualitative methodologies, grounded theory provides researchers with a process that can be followed to facilitate the conduct of such research. As an example, Thurston and others 10 used constructivist grounded theory to explore the availability of arthritis care among indigenous people of Canada and were able to identify a number of influences on health care for this population.

- Phenomenology attempts to understand problems, ideas, and situations from the perspective of common understanding and experience rather than differences. 10 Phenomenology is about understanding how human beings experience their world. It gives researchers a powerful tool with which to understand subjective experience. In other words, 2 people may have the same diagnosis, with the same treatment prescribed, but the ways in which they experience that diagnosis and treatment will be different, even though they may have some experiences in common. Phenomenology helps researchers to explore those experiences, thoughts, and feelings and helps to elicit the meaning underlying how people behave. As an example, Hancock and others 11 used a phenomenological approach to explore health care professionals’ views of the diagnosis and management of heart failure since publication of an earlier study in 2003. Their findings revealed that barriers to effective treatment for heart failure had not changed in 10 years and provided a new understanding of why this was the case.

ROLE OF THE RESEARCHER

For any researcher, the starting point for research must be articulation of his or her research world view. This core feature of qualitative work is increasingly seen in quantitative research too: the explicit acknowledgement of one’s position, biases, and assumptions, so that readers can better understand the particular researcher. Reflexivity describes the processes whereby the act of engaging in research actually affects the process being studied, calling into question the notion of “detached objectivity”. Here, the researcher’s own subjectivity is as critical to the research process and output as any other variable. Applications of reflexivity may include participant-observer research, where the researcher is actually one of the participants in the process or situation being researched and must then examine it from these divergent perspectives. 12 Some researchers believe that objectivity is a myth and that attempts at impartiality will fail because human beings who happen to be researchers cannot isolate their own backgrounds and interests from the conduct of a study. 5 Rather than aspire to an unachievable goal of “objectivity”, it is better to simply be honest and transparent about one’s own subjectivities, allowing readers to draw their own conclusions about the interpretations that are presented through the research itself. For new (and experienced) qualitative researchers, an important first step is to step back and articulate your own underlying biases and assumptions. The following questions can help to begin this reflection process:

- Why am I interested in this topic? To answer this question, try to identify what is driving your enthusiasm, energy, and interest in researching this subject.

- What do I really think the answer is? Asking this question helps to identify any biases you may have through honest reflection on what you expect to find. You can then “bracket” those assumptions to enable the participants’ voices to be heard.

- What am I getting out of this? In many cases, pressures to publish or “do” research make research nothing more than an employment requirement. How does this affect your interest in the question or its outcomes, or the depth to which you are willing to go to find information?

- What do others in my professional community think of this work—and of me? As a researcher, you will not be operating in a vacuum; you will be part of a complex social and interpersonal world. These external influences will shape your views and expectations of yourself and your work. Acknowledging this influence and its potential effects on personal behaviour will facilitate greater self-scrutiny throughout the research process.

FROM FRAMEWORKS TO METHODS

Qualitative research methodology is not a single method, but instead offers a variety of different choices to researchers, according to specific parameters of topic, research question, participants, and settings. The method is the way you carry out your research within the paradigm of quantitative or qualitative research.

Qualitative research is concerned with participants’ own experiences of a life event, and the aim is to interpret what participants have said in order to explain why they have said it. Thus, methods should be chosen that enable participants to express themselves openly and without constraint. The framework selected by the researcher to conduct the research may direct the project toward specific methods. From among the numerous methods used by qualitative researchers, we outline below the three most frequently encountered.

DATA COLLECTION

Patton 12 has described an interview as “open-ended questions and probes yielding in-depth responses about people’s experiences, perceptions, opinions, feelings, and knowledge. Data consists of verbatim quotations and sufficient content/context to be interpretable”. Researchers may use a structured or unstructured interview approach. Structured interviews rely upon a predetermined list of questions framed algorithmically to guide the interviewer. This approach resists improvisation and following up on hunches, but has the advantage of facilitating consistency between participants. In contrast, unstructured or semistructured interviews may begin with some defined questions, but the interviewer has considerable latitude to adapt questions to the specific direction of responses, in an effort to allow for more intuitive and natural conversations between researchers and participants. Generally, you should continue to interview additional participants until you have saturated your field of interest, i.e., until you are not hearing anything new. The number of participants is therefore dependent on the richness of the data, though Miles and Huberman 2 suggested that more than 15 cases can make analysis complicated and “unwieldy”.

Focus Groups

Patton 12 has described the focus group as a primary means of collecting qualitative data. In essence, focus groups are unstructured interviews with multiple participants, which allow participants and a facilitator to interact freely with one another and to build on ideas and conversation. This method allows for the collection of group-generated data, which can be a challenging experience.

Observations

Patton 12 described observation as a useful tool in both quantitative and qualitative research: “[it involves] descriptions of activities, behaviours, actions, conversations, interpersonal interactions, organization or community processes or any other aspect of observable human experience”. Observation is critical in both interviews and focus groups, as nonalignment between verbal and nonverbal data frequently can be the result of sarcasm, irony, or other conversational techniques that may be confusing or open to interpretation. Observation can also be used as a stand-alone tool for exploring participants’ experiences, whether or not the researcher is a participant in the process.

Selecting the most appropriate and practical method is an important decision and must be taken carefully. Those unfamiliar with qualitative research may assume that “anyone” can interview, observe, or facilitate a focus group; however, it is important to recognize that the quality of data collected through qualitative methods is a direct reflection of the skills and competencies of the researcher. 13 The hardest thing to do during an interview is to sit back and listen to participants. They should be doing most of the talking—it is their perception of their own life-world that the researcher is trying to understand. Sophisticated interpersonal skills are required, in particular the ability to accurately interpret and respond to the nuanced behaviour of participants in various settings. More information about the collection of qualitative data may be found in the “Further Reading” section of this paper.

It is essential that data gathered during interviews, focus groups, and observation sessions are stored in a retrievable format. The most accurate way to do this is by audio-recording (with the participants’ permission). Video-recording may be a useful tool for focus groups, because the body language of group members and how they interact can be missed with audio-recording alone. Recordings should be transcribed verbatim and checked for accuracy against the audio- or video-recording, and all personally identifiable information should be removed from the transcript. You are then ready to start your analysis.

DATA ANALYSIS

Regardless of the research method used, the researcher must try to analyze or make sense of the participants’ narratives. This analysis can be done by coding sections of text, by writing down your thoughts in the margins of transcripts, or by making separate notes about the data collection. Coding is the process by which raw data (e.g., transcripts from interviews and focus groups or field notes from observations) are gradually converted into usable data through the identification of themes, concepts, or ideas that have some connection with each other. It may be that certain words or phrases are used by different participants, and these can be drawn together to allow the researcher an opportunity to focus findings in a more meaningful manner. The researcher will then give the words, phrases, or pieces of text meaningful names that exemplify what the participants are saying. This process is referred to as “theming”. Generating themes in an orderly fashion out of the chaos of transcripts or field notes can be a daunting task, particularly since it may involve many pages of raw data. Fortunately, sophisticated software programs such as NVivo (QSR International Pty Ltd) now exist to support researchers in converting data into themes; familiarization with such software supports is of considerable benefit to researchers and is strongly recommended. Manual coding is possible with small and straightforward data sets, but the management of qualitative data is a complexity unto itself, one that is best addressed through technological and software support.

There is both an art and a science to coding, and the second checking of themes from data is well advised (where feasible) to enhance the face validity of the work and to demonstrate reliability. Further reliability-enhancing mechanisms include “member checking”, where participants are given an opportunity to actually learn about and respond to the researchers’ preliminary analysis and coding of data. Careful documentation of various iterations of “coding trees” is important. These structures allow readers to understand how and why raw data were converted into a theme and what rules the researcher is using to govern inclusion or exclusion of specific data within or from a theme. Coding trees may be produced iteratively: after each interview, the researcher may immediately code and categorize data into themes to facilitate subsequent interviews and allow for probing with subsequent participants as necessary. At the end of the theming process, you will be in a position to tell the participants’ stories illustrated by quotations from your transcripts. For more information on different ways to manage qualitative data, see the “Further Reading” section at the end of this paper.

ETHICAL ISSUES

In most circumstances, qualitative research involves human beings or the things that human beings produce (documents, notes, etc.). As a result, it is essential that such research be undertaken in a manner that places the safety, security, and needs of participants at the forefront. Although interviews, focus groups, and questionnaires may seem innocuous and “less dangerous” than taking blood samples, it is important to recognize that the way participants are represented in research can be significantly damaging. Try to put yourself in the shoes of the potential participants when designing your research and ask yourself these questions:

- Are the requests you are making of potential participants reasonable?

- Are you putting them at unnecessary risk or inconvenience?

- Have you identified and addressed the specific needs of particular groups?

Where possible, attempting anonymization of data is strongly recommended, bearing in mind that true anonymization may be difficult, as participants can sometimes be recognized from their stories. Balancing the responsibility to report findings accurately and honestly with the potential harm to the participants involved can be challenging. Advice on the ethical considerations of research is generally available from research ethics boards and should be actively sought in these challenging situations.

GETTING STARTED

Pharmacists may be hesitant to embark on research involving qualitative methods because of a perceived lack of skills or confidence. Overcoming this barrier is the most important first step, as pharmacists can benefit from inclusion of qualitative methods in their research repertoire. Partnering with others who are more experienced and who can provide mentorship can be a valuable strategy. Reading reports of research studies that have utilized qualitative methods can provide insights and ideas for personal use; such papers are routinely included in traditional databases accessed by pharmacists. Engaging in dialogue with members of a research ethics board who have qualitative expertise can also provide useful assistance, as well as saving time during the ethics review process itself. The references at the end of this paper may provide some additional support to allow you to begin incorporating qualitative methods into your research.

CONCLUSIONS

Qualitative research offers unique opportunities for understanding complex, nuanced situations where interpersonal ambiguity and multiple interpretations exist. Qualitative research may not provide definitive answers to such complex questions, but it can yield a better understanding and a springboard for further focused work. There are multiple frameworks, methods, and considerations involved in shaping effective qualitative research. In most cases, these begin with self-reflection and articulation of positionality by the researcher. For some, qualitative research may appear commonsensical and easy; for others, it may appear daunting, given its high reliance on direct participant– researcher interactions. For yet others, qualitative research may appear subjective, unscientific, and consequently unreliable. All these perspectives reflect a lack of understanding of how effective qualitative research actually occurs. When undertaken in a rigorous manner, qualitative research provides unique opportunities for expanding our understanding of the social and clinical world that we inhabit.

Further Reading

- Breakwell GM, Hammond S, Fife-Schaw C, editors. Research methods in psychology. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications Ltd; 1995. [ Google Scholar ]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications Ltd; 1998. [ Google Scholar ]

- Willig C. Introducing qualitative research in psychology. Buckingham (UK): Open University Press; 2001. [ Google Scholar ]

- Guest G, Namey EE, Mitchel ML. Collecting qualitative data: a field manual for applied research. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications Ltd; 2013. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ogden R. Bias. In: Given LM, editor. The Sage encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications Inc; 2008. pp. 61–2. [ Google Scholar ]

This article is the seventh in the CJHP Research Primer Series, an initiative of the CJHP Editorial Board and the CSHP Research Committee. The planned 2-year series is intended to appeal to relatively inexperienced researchers, with the goal of building research capacity among practising pharmacists. The articles, presenting simple but rigorous guidance to encourage and support novice researchers, are being solicited from authors with appropriate expertise.

Previous article in this series:

Bond CM. The research jigsaw: how to get started. Can J Hosp Pharm . 2014;67(1):28–30.

Tully MP. Research: articulating questions, generating hypotheses, and choosing study designs. Can J Hosp Pharm . 2014;67(1):31–4.

Loewen P. Ethical issues in pharmacy practice research: an introductory guide. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2014;67(2):133–7.

Tsuyuki RT. Designing pharmacy practice research trials. Can J Hosp Pharm . 2014;67(3):226–9.

Bresee LC. An introduction to developing surveys for pharmacy practice research. Can J Hosp Pharm . 2014;67(4):286–91.

Gamble JM. An introduction to the fundamentals of cohort and case–control studies. Can J Hosp Pharm . 2014;67(5):366–72.

Competing interests: None declared.

Higher Ed Professor

Demystifying higher education.

- Productivity

- Issue Discussion

- Current Events

Tips for novice qualitative researchers when using quotes

O ne of the biggest struggles that new qualitative researchers experience is how to make use of their data, specifically the use of quotes. The balance is a delicate one where you want to maintain fidelity to the voices of your participants and other data sources, yet you cannot simply dump pages and pages of transcriptions into the findings section. You have to identify the most central elements, pick out representative quotes, and at the most basic level tell a story about what you found. In this post, I want to provide tips for novice qualitative researchers when using quotes to help navigate this difficult balancing act.

It can be helpful to think about how a good journalist would convey information in a newspaper or magazine article. The best reporters are able to blend in the voices of their sources (using quotes) along with context setting prose.

There is a balancing act that conveys the information of the article using an effective mix of direct quotations and other text to understand and evaluate the facts being presented.

As the reader, you hopefully have enough information by the end of the story to understand what is happening but also to consider the various viewpoints presented in the story.

In many ways, this is exactly what you want to do with the presentation of your findings. You want to present the main ideas (i.e. your themes) along with supporting quotations.

The way you talk about the data, as in the case of the reporter, will provide additional context and a narrative to help guide the reader through the information presented.

Along these same lines, as the author, you will have to determine your voice in the writing of your findings.

Are you an impartial observer? Are you a participant in the conversation?

The type of study you are conducting will also provide some hints as to the approach you may take.

For instance, an ethnography would suggest the author as a more active participant as compared to a traditional case study approach.

Of course, as you discussed in your positionality section of your research, there are no truly impartial observers.

Rather, novice researchers often write their findings in a more neutral tone rather than overtly inserting themselves into the narrative. In many cases, this is because students so used to the rhetoric around bias as a negative try to remove themselves to make their research less biased.

In other cases, it is simply easier to “report the news” than be a part of the story.

Moreover, the author must decide how much of a quote to use in a particular section.

The options can range from a small phrase through a sentence to a longer block quotation. Often, new qualitative researchers will too liberally use block quotations.

In other words, a key phrase or sentence may be all they really want to convey but they include a paragraph to “provide context.”

Avoid this trap.

If you need to provide context for a quote, then put this in your own words rather than in the participants.

Along the same lines, nearly every qualitative research falls into the trap of falling in love with a one or two participants.

It is amazing to sit down with an interviewee who provides great insight, is exceptionally quotable, and hits on everything you want to address in your findings.

However, no matter how great a participant might be, you have to be careful that you are relying too much on a single or even a few participants.

Likewise, there will always be those dud interviews that do not provide much information.

As the author, try to vary up the participants you use in your findings. There may be a good reason to focus on one or two people in a section. For example, they may have been the only people with a given perspective.

Ultimately, to the extent possible, you want to vary how often you are quoting your participants.

If you see that you are using one or two for more than a paragraph or two, ask yourself if there are others who may not be quite as quotable, but still provide a shared perspective or view on the topic you are discussing.

There are two ways to approach which quotes you will use that will provide the best information while also demonstrating the range of your data (which is the primary reason to vary your sources).

First, your goal should be to begin by identify the best and most exemplary quotes for each point that you want to make, a process that begins with data analysis but is not completed until writing.

Second, you want to make sure to spread these quotes around across participants.

You will likely have a participant or two that have the most amazing quotes for every section of your findings. That is great and this is a good problem to have, but you obviously need to use more people or sources of data.

So after you identify the best quotes, look to see if you are relying too much on a few sources through the findings chapter or inside of individual sections.

If you are, then look at who has the second-best quote.

It might not be quite as pithy as your exemplary quote, but it still makes the point you are trying to convey. Replace some of your exemplary quotes with some second or even third best quotes to provide better balance throughout your discussion of the data.

Of course, there is far more that could be said when discussion how to write up qualitative data. My goal here as been to provide some tips for novice qualitative researchers when using quotes and discussing findings.

One of the great challenges of qualitative research is constantly working to improve your writing and how you convey the voices of your data.

Whether you are a novice or an experienced qualitative researcher, this is an ongoing challenge and I hope you continue working to improve the craft of qualitative research.

Beyond the default colon: Effective use of quotes in qualitative research

- The Writer's Craft

- Open access

- Published: 22 November 2019

- Volume 8 , pages 360–364, ( 2019 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Lorelei Lingard 1

11k Accesses

65 Citations

38 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In the Writer’s Craft section we offer simple tips to improve your writing in one of three areas: Energy, Clarity and Persuasiveness. Each entry focuses on a key writing feature or strategy, illustrates how it commonly goes wrong, teaches the grammatical underpinnings necessary to understand it and offers suggestions to wield it effectively. We encourage readers to share comments on or suggestions for this section on Twitter, using the hashtag: #how’syourwriting?

Last week the ‘e’ key died on my laptop. It’s a first-world problem, I’ll admit, but it really threw my writing for a loop—a lot of words require an ‘e’ key. Reflecting on what other keys I could not do without, I made a quick shortlist: comma, ‘ly’ and colon. The comma because its absence would consign me to the sort of breathy, adolescent writing that fills social media. The ‘ly’ because without that duo I can’t make most of the adverbs that prop up my first drafts. And the colon because I’m a qualitative researcher. How would I introduce quotes if the colon key were out of order?

I’m only partly joking. Every qualitative researcher confronts the challenge of selecting the right quotes and integrating them effectively into their manuscripts. As writers, we are all guilty of resorting to the default colon as an easy way to tuck quotes into our sentences; as readers, we have all suffered through papers that read like a laundry list of quotes rather than a story about what the writer learned. This Writer’s Craft instalment offers suggestions to help you choose the right quotes and integrate them with coherence and style, following the principles of authenticity and argument.

Authenticity

At the point of manuscript writing, a qualitative researcher is swimming in a sea of data. Innumerable transcript excerpts have been copied and pasted into data analysis software or (for the more tactile among us) onto multi-coloured sticky notes. Some of these excerpts we like very much. However, very few of them will make it into the final manuscript, particularly if we are writing for publication in a health research or medical education journal, with their 3000–4000 word limits.

Selecting the best quotes from among these cherished excerpts is harder than it looks. We should be guided by the principle of authenticity: does the quote offer readers first hand access to dominant patterns in the data? There are three parts to selecting a good, authentic quote: the quote is illustrative of the point the writer is making about the data, it is reasonably succinct, and it is representative of the patterns in data. Consider this quote, introduced with a short phrase to orient the reader:

Rather than feeling they were changing identities as they went through their training, medical students described the experience of accumulating and reconciling multiple identities: ‘the “life me”, who I was when I started this, is still here, but now there’s also, like, a “scientific me” as well as a sort of “doctor me”. And I’m trying to be all of that’ (S15) .

This quote is illustrative, providing an explicit example of the point that student identity is multiplying as training unfolds. It is succinct, expressing efficiently what other participants took pages to describe. And it is representative, remaining faithful to the overall sentiments of the many participants reporting this idea.

We have all read—and written!—drafts in which the quoted material does not reflect these characteristics. The remainder of this section addresses these recurring problems.

Is the quote illustrative?

A common challenge is the quote that illustrates the writer’s point implicitly, but not explicitly. Consider this example:

Medical students are undergoing a process of identity-negotiation: we’re ‘learning so much all the time, and some of it is the science stuff and some of it is professional or, like, practical ethical things, and we have to figure all that out’ (S2).

For this quote to serve as evidence for the point of identity-negotiation, the reader must infer that ‘figure all that out’ is a reference to this process. But readers may read their own meaning into decontextualized transcript extracts. Explicit is better, even if it sacrifices succinctness. In fact, this is the right quote, but we had trimmed away the first three sentences where ‘figuring out identity’ got explicit mention. The quote could be lengthened to include these sentences, or, to preserve succinctness, just that quoted phrase can be inserted into the introduction to the quote:

Medical students are ‘figuring out identity’, a process of negotiation in which they are ‘learning so much all the time, and some of it is the science stuff and some of it is professional or, like, practical ethical things, and we have to figure all that out’ (S2).

Is the quote succinct?

Interview transcripts are characterized by meandering and elliptical or incomplete speech. Therefore, you can search diligently and still come up with a 200-word quote to illustrate your 10-word point. Sometimes the long quote is perfect and you should include it. Often, however, you need to tighten it up. By including succinctness as part of the authenticity principle, my aim is to remind writers to explicitly consider whether their tightening up retains the gist of the quote.

The previous example illustrates one tightening technique: extract key phrases and integrate them into your own, introductory sentence to the quote. Another solution is to use the ellipsis to signal that you have cut part of the quote out:

Identity formation in the clinical environment is also influenced by materials and tools, ‘all this stuff you’ve never used before … you don’t know where it is or how to use it, and don’t even get me started on the computerized record. … So many hours and I’m still confused, am I ever going to know where to enter things?’ (S7) .

The first ellipsis signals that something mid-sentence has been removed. In this case, this missing material was an elaboration of ‘all this stuff’ that mentioned other details not relevant to the point being made. The second ellipsis follows a period, and therefore signals that at least one sentence has been removed and perhaps more. When using an ellipsis, only remove material that is irrelevant to the meaning of the quote, not relevant material that importantly nuances the meaning of the quote. The goal is not a bricolage which cuts and pastes tiny bits so that participants say what you want them to; it is a succinct-enough representation that remains faithful to the participant’s intended meaning.

Changing the wording of a quotation always risks violating the authenticity principle, so writers must do it thoughtfully. Two other situations, however, may call for this approach: to maintain the grammatical integrity of your sentence and to tidy up oral speech Footnote 1 . The first is usually not problematic, particularly if you are altering for consistent tense or for agreement of verb and subject or pronoun and antecedent, or replacing a pronoun with its referent. Square brackets signal such changes:

Participants from the community hospital setting, however, ‘[challenged] the assumption of anonymity when evaluating teachers’. (verb tense changed from present to past)

The second situation can be trickier: when should you tidy up the messiness of conversational discourse? Interview transcripts are replete with what linguists refer to as ‘fillers’ or ‘hesitation markers’, sounds and words such as ‘ah/uh/um/like/you know/right’ [ 1 ]. There is general agreement among qualitative scholars that quotes should be presented verbatim as much as possible, and those engaged in discourse and narrative analysis will necessarily analyze such hesitations as part of the meaning. In other applied social research methodologies, however, writers might do some ‘light tidying up’ both for readability and for ethical reasons, as long as they do not undermine authenticity in doing so [ 2 ]. Ethical issues include the desire not to do a disservice to participants by representing the um’s and ah’s of their natural speech, and the concern to protect participant anonymity by removing identifiable linguistic features such as regional or accented speech.

Finally, an emerging strategy for succinctness is to put the quotes into a table. Many qualitative researchers resent the constraints of the table format as an incursion from the quantitative realm. However, used thoughtfully, it can offer a means of presenting complex results efficiently. In this example, Goldszmidt et al. name, define and illustrate five main types of supervisor interruptions that they observed during their study of case review on internal medicine teaching teams (Tab. 1 ; [ 3 ]).

This is a nice example of how ‘Tab. 1 ’, conventionally used in quantitative research papers for demographic details of the research sample, can be re-conceptualized to feature the key findings from a qualitative analysis. Tables should be supplemented, however, with narrative explanation in which the writer contextualizes and interprets the quoted material. More on this in the section on Argument.

Is the quote representative?

We have all been tempted to include the highly provocative quote (that thing we cannot believe someone said on tape), only to realize by the third draft that it misrepresents the data and must be relinquished. Quote selection should reflect strong patterns in the data; while discrepant examples serve an important purpose, their use should be purposeful and explicit. Your quote selection should also be distributed across participants, in order that you represent the data set. This may mean using the second- or third-best example rather than continuing to quote the same one or two highly articulate individuals.

You must provide sufficient context that readers can accurately infer the meaning of the quote. Sometimes this means including the interviewer’s question as well as the participant’s answer. In focus group research, where the emphasis is on the group discussion, it might be necessary to quote an exchange among participants rather than extracting individual comments. This example illustrates this technique:

Interviewer: And, in your experience, how do the students respond to your feedback about how well they communicated? SP1: Oh, really well, it’s really important to the students, they listen to what we say about their performance— Interruption with overlapping talk SP4: Well, yeah, on a good day maybe, sure. But not every time. Lots of sessions I feel like we’re probably more like props to them, so how well we think they did, I’m not sure that matters. SP3: Don’t you find it depends on the student? (FG2)

Of course, such a long excerpt threatens the goal of succinctness. Alternatively, you could use multiple quotes from this excerpt in a single sentence of your own:

Some standardized patients in the group believed that their assessor role was ‘really important to the students, they listen to what we say about their performance’, while others argued that ‘we’re probably more like props to them, so how well we think they did, I’m not sure that matters’. (FG2)

Sometimes a quote is representative but also, therefore, identifiable, jeopardizing confidentiality:

One participant explained that, ‘as chair of the competency committee, I prioritize how we spend our time. So that we can pay sufficient attention to this 2nd year resident. She’s supposed to be back from maternity leave but she had complications so her rotations need some altering for her to manage.’ (CCC4, P2)

In this case, the convention of using a legend (Clinical Competency Committee 4, participant 2) to attribute the quote may be insufficient to protect anonymity. If the study involves few programs and the methods identify them (e.g., Paediatrics and Medicine) and name the institution (e.g., Western University), the speaker may be identifiable to some readers, as may the resident.

Quoted material does not stand on its own: we must incorporate it into our texts, both grammatically and rhetorically. Grammatical incorporation is relatively straightforward, with one main rule to keep in mind: quoted material is subject to the same sentence-level conventions for grammar and punctuation as non-quoted material. Read this example aloud:

Arts and humanities teaching offers an opportunity for faculty to connect with medical students on a different level, ‘we can share how we feel about the work of caring, what it costs us, how it rewards us, as human beings’ (F9).

Your ear likely hears that this should be two sentences. But quotation marks seem to distract us from this, and we create a run-on sentence by putting a comma between the sentences. An easy correction is to replace the comma with a colon.

Arts and humanities teaching offers an opportunity for faculty to connect with medical students on a different level: ‘we can share how we feel about the work of caring, what it costs us, how it rewards us, as human beings’ (F9).

Many writers rely on the colon as their default mechanism for integrating quoted material. However, while it is often grammatically accurate, it is not always rhetorically sufficient. That is, the colon doesn’t contextualize, it doesn’t interpret. Instead, it ‘drops’ the quote in and leaves the reader to infer how the quoted material illustrates or advances the argument. This is problematic because it does not fulfil the requirement for adequacy of interpretation in presenting qualitative results. As Morrow argues, writers should aim for a balance of their interpretations and supporting quotations: ‘an overemphasis on the researcher’s interpretations at the cost of participant quotes will leave the reader in doubt as to just where the interpretations came from; an excess of quotes will cause the reader to become lost in the morass of stories’ [ 4 ]. (p. 256).

There are many techniques for achieving this balance between researcher interpretations and supporting quotations. Some techniques retain the default colon but attend carefully to the material that precedes it. Consider the following examples:

One clinician said: ‘Entrustment isn’t a decision, it’s a relationship’. (F21) One clinician argued: ‘Entrustment isn’t a decision, it’s a relationship’. (F21) One clinician in the focus group disagreed with the idea that entrustment was about deciding trainee progress: ‘Entrustment isn’t a decision, it’s a relationship’. (F21) Focus group participants debated the meaning of entrustment. Many described it matter-of-factly as ‘the process we use to decide whether the trainee should progress’, while a few argued that ‘entrustment isn’t a decision, it’s a relationship’. (F21)

These examples offer progressively more contextualization for the quote. The first example simply drops the quote in following the nondescript verb, ‘said’, offering no interpretive gloss and therefore exerting minimal rhetorical control over the reader. The second offers some context via the verb ‘argued’, which interprets the participant’s positioning or tone. The third interprets the meaning of the quote even more by situating it in the context of a focus group debate. And the fourth eschews the default colon entirely, integrating two quotes into the narrative structure of the author’s sentence to illustrate the dominant and the discrepant positions on entrustment in this focus group debate.

Integrating quotes into the narrative structure of your sentence, like the last example, offers two advantages to the writer. First, it interprets the quote for the reader and therefore exerts strong rhetorical control over the quote’s meaning. Second, it offers variety and style. If your goal is compelling prose, variety and style should not be underestimated. We have all had the experience of reading Results sections that proceed robotically: point-colon-quote, point-colon-quote, point-colon-quote …. If only to make the reader’s experience more enjoyable, your revision process should involve converting some of these to integrated narration.

Notwithstanding the goal of succinctness, sometimes you will include a longer quote because it beautifully illustrates the point. However, a long quote may offer opportunities for readers to focus on images or phrases other than those you intended, therefore creating incoherence in the argument you are making about your results. To guard against this, you might try the ‘quotation sandwich’ technique [ 5 ] of both an introductory phrase that sets up the context of the quote and a summary statement following it emphasizing why you consider it important and what you are using it to illustrate.

Finally, how many quotes do you need to support your point? More is not necessarily better. One quote should be sufficient to illustrate your point. Some points in your argument may not require a quoted excerpt at all. Consider this example, in which the first sentence presents a finding that is not illustrated with a quotation:

Residents described themselves as being always tired. However, their perceptions of the impact of their fatigue varied, from ‘not a factor in the care I provide’ (R8) to ‘absolutely killing me … I’m falling asleep at the bedside’ (R15).

The finding that residents are always tired does not require illustration. It is readily understandable and will not surprise anyone; therefore, following it with the quote ‘I’m tired all the time’ (R2) will feel redundant. The second part of the finding, however, benefits from illustration to show the variety of perception regarding impact.

If you do use multiple quotes to illustrate a point in your argument, then you must establish the relations between them for the reader. You can do this between the quoted excerpts or after them, as modelled above with the four examples used to illustrate progressively stronger quote contextualization.

In conclusion, quotes can be the life’s blood of your qualitative research paper. However, they are the evidence, not the argument. They do not speak for themselves and readers cannot infer what you intend them to illustrate. The authenticity principle can help you select a quote that is illustrative, succinct and representative, while the argument principle can remind you to attend to the grammatical and the rhetorical aspects of integrating the quote into the story you are telling about your research.

A third situation is beyond the scope of this piece: translating quoted material from another language into English. For careful consideration of this issue, please see Helmich et al. [ 6 ].

Gunnel T. Planning what to say: Uh and um among the pragmatic markers. In Kaltenbock G, Keizer E, Lohmann A. (eds). Outside the Clause: Form and Function of Extra-Clausal Constituents. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins; 2016: pp. 97–122.

Corden A, Sainsbury R. Using Verbatim Quotations in Reporting Qualitative Social Research: Researchers’ views. University of. York: York: Social Policy Research Unit; 2006.

Google Scholar

Goldszmidt M, Aziz N, Lingard L. Taking A Detour: Positive And Negative Impacts Of Supervisor Interruptions During Admission Case Review, Acad Med. 2012;87:1382–8.

Morrow SL. Quality and Trustworthiness in Qualitative Research in Counseling Psychology. J Couns Psychol. 2005;52:250–60.

Article Google Scholar

Graff G, Birkenstein C. ‘They Say/I Say’: The Moves that Matter in Academic Writing. 4th edition. London: Norton & Co; 2018.

Helmich E, Cristancho S, Diachun L, et al. ‘How would you call this in English?’ Being reflective about translations in international, cross-cultural qualitative research. Perspect Med Educ. 2017;6:127.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centre for Education Research & Innovation and Department of Medicine, Health Sciences Addition, Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry, Western University, London, Canada

Lorelei Lingard

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Lorelei Lingard .

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Lingard, L. Beyond the default colon: Effective use of quotes in qualitative research. Perspect Med Educ 8 , 360–364 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-019-00550-7

Download citation

Published : 22 November 2019

Issue Date : December 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-019-00550-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Market Research

17 research quotes to inspire and amuse you

Being a researcher requires dedication, hard work and more than a little inspiration. Here’s something to boost the last item on that list.

We’ve sourced some of the most interesting and thought-provoking research quotes we can find. We hope they’ll leave you feeling inspired and motivated to start – or complete – your best ever research project.

As these quotes show, research is a common thread running through all kinds of professions and pursuits, from Ancient Rome right up to the present day. If you practice research, you’re part of a long list of people throughout history, all dedicated to finding new knowledge and ideas that ultimately make the world a better place.

Looking for the most recent trends to enhance your results?

Free eBook: The new era of market research is about intelligence

1. “No research without action, no action without research”

- Kurt Lewin

Lewin (1890-1947) was a German-American social psychologist. He’s known for his theory that human behavior is a function of our psychological environment.

2. “Research is seeing what everybody else has seen and thinking what nobody else has thought.”

- Albert Szent-Györgyi

Szent-Györgyi (1893-1986) was a Hungarian pharmacologist known for his work on vitamins and oxidation. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1937.

3. "Bad news sells papers. It also sells market research."

- Byron Sharp

Sharp is Professor of Marketing Science and Director of the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute, the world’s largest centre for research into marketing.

4. "In fact, the world needs more nerds."

- Ben Bernanke

Bernanke is an American economist and former chair of the board of governors at the United Stares Federal Reserve.

5. "Research is what I'm doing when I don't know what I'm doing."

- Wernher von Braun

Von Braun (1912-1977) was a German-American physicist and rocket engineer whose team launched the first US satellite into space.

6. "Research is formalized curiosity. It is poking and prying with a purpose."

- Zora Neale Hurston

Hurston (1891-1960) was an American anthropologist and writer known for her research and writing on slavery, race, folklore and the African-American experience.

7. "Research is creating new knowledge."

- Neil Armstrong

Armstrong (1930-2012) was an American astronaut famed for being the first man to walk on the Moon.

8. "I believe in innovation and that the way you get innovation is you fund research and you learn the basic facts."

- Bill Gates

Gates needs little introduction – he’s an entrepreneur, philanthropist and the founder of Microsoft.

9. “The best research you can do is talk to people”

- Terry Pratchett

Pratchett is an award-winning British science fiction and fantasy author. He was knighted in 2009. He is known for The Hitch Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy and the Discworld series.

10. “Research means that you don’t know, but are willing to find out”

- Charles F. Kettering

Kettering (1876-1958) was an American engineer, known for inventing the electric starter used in combustion engines, as well as other automobile technologies.

11. “Nothing has such power to broaden the mind as the ability to investigate systematically and truly all that comes under thy observation in life.”

- Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius (121-180) was a Roman Emperor and Stoic philosopher.

12. “It is a good thing for a research scientist to discard a pet hypothesis every day before breakfast.“

- Konrad Lorenz

Lorenz (1903-1989) was an Austrian biologist known for his game-changing research on animal behavior. He was jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1973.

13. “Research is something that everyone can do, and everyone ought to do. It is simply collecting information and thinking systematically about it.”

- Raewyn Connell

Connell is an Australian sociologist. She is a former professor of at the University of Sydney and is known for her work on gender and transgender studies.

14. “As for the future, your task is not to foresee it, but to enable it.”

- Antoine de Saint Exupery

De Saint Exupery (1900-1944) was a French aviator, author and poet, best known for his story The Little Prince, one of the best-selling books of all time.

15. “It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data.”

- Arthur Conan Doyle (writing as Sherlock Holmes)

Conan Doyle (1859-1930) was a British crime writer and creator of the legendary Sherlock Holmes, master of deduction.

16. “If we knew what we were doing, it would not be called research, would it?”

- Albert Einstein

Maybe the most famous scientist of all time, Albert Einstein (1879-1955) was a German physicist who came up with the theory of relativity. However, it was his description of the photoelectric effect, the interplay between light and electrically charged atoms, that won him the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1921.

17. “The power of statistics and the clean lines of quantitative research appealed to me, but I fell in love with the richness and depth of qualitative research.”

- Brené Brown

Brown is a researcher and storyteller studying courage, shame, empathy and vulnerability. She is a best-selling author and inspirational speaker. She is a research professor at the University of Houston.

Sarah Fisher

Related Articles

June 27, 2023

The fresh insights people: Scaling research at Woolworths Group

June 20, 2023

Bank less, delight more: How Bankwest built an engine room for customer obsession

June 16, 2023

How Qualtrics Helps Three Local Governments Drive Better Outcomes Through Data Insights

April 1, 2023

Academic Experience

Great survey questions: How to write them & avoid common mistakes

March 21, 2023

Sample size calculator

March 9, 2023

Experience Management

X4 2023: See the XM innovations unveiled for customer research, marketing, and insights teams

February 22, 2023

Achieving better insights and better product delivery through in-house research

December 6, 2022

Improved Topic Sentiment Analysis using Discourse Segmentation

Stay up to date with the latest xm thought leadership, tips and news., request demo.

Ready to learn more about Qualtrics?

- Open access

- Published: 25 April 2024

A qualitative evaluation of factors influencing Tumor Treating fields (TTFields) therapy decision making among brain tumor patients and physicians

- Priya Kumthekar 1 , 2 ,

- Madison Lyleroehr 3 ,

- Leilani Lacson 7 ,

- Rimas V. Lukas 1 , 2 ,

- Karan Dixit 1 , 2 ,

- Roger Stupp 1 , 2 ,

- Timothy Kruser 7 ,

- Jeff Raizer 1 , 2 ,

- Alexander Hou 6 ,

- Sean Sachdev 5 , 2 ,

- Margaret Schwartz 1 , 2 ,

- Jessica Bajas PA 1 ,

- Ray Lezon 1 , 2 ,

- Karyn Schmidt 1 ,

- Christina Amidei 4 , 2 &

- Karen Kaiser 3

BMC Cancer volume 24 , Article number: 527 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

Tumor Treating Fields (TTFields) Therapy is an FDA-approved therapy in the first line and recurrent setting for glioblastoma. Despite Phase 3 evidence showing improved survival with TTFields, it is not uniformly utilized. We aimed to examine patient and clinician views of TTFields and factors shaping utilization of TTFields through a unique research partnership with medical neuro oncology and medical social sciences.

Adult glioblastoma patients who were offered TTFields at a tertiary care academic hospital were invited to participate in a semi-structured interview about their decision to use or not use TTFields. Clinicians who prescribe TTFields were invited to participate in a semi-structured interview about TTFields.

Interviews were completed with 40 patients with a mean age of 53 years; 92.5% were white and 60% were male. Participants who decided against TTFields stated that head shaving, appearing sick, and inconvenience of wearing/carrying the device most influenced their decision. The most influential factors for use of TTFields were the efficacy of the device and their clinician’s opinion. Clinicians ( N = 9) stated that TTFields was a good option for glioblastoma patients, but some noted that their patients should consider the burdens and benefits of TTFields as it may not be the desired choice for all patients.

Conclusions

This is the first study to examine patient decision making for TTFields. Findings suggest that clinician support and efficacy data are among the key decision-making factors. Properly understanding the path to patients’ decision making is crucial in optimizing the use of TTFields and other therapeutic decisions for glioblastoma patients.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Glioblastoma is the most common malignant primary brain tumor in adults, accounting for over 50% of all gliomas, with an annual incidence rate of 3 to 4 cases per 100,000 people, resulting in 240,000 newly diagnosed cases worldwide each year [ 1 , 2 ]. Since 2005, the standard treatment for glioblastoma has been surgical resection followed by radiotherapy with concurrent and adjuvant temozolomide (TMZ). For newly diagnosed glioblastomas, the addition of TMZ to surgery and radiation therapy prolongs median survival from 12.1 to 14.6 months and increases the five-year survival rate from 2 to 10% [ 3 ].

In addition to the current standard of care, patients with glioblastomas can receive a more recently approved therapy called Tumor Treating Fields Therapy (TTFields) (Optune™). TTFields utilizes a portable, battery-operated device that delivers a low-intensity, alternating electric field to the tumor via surface electrodes (transducer arrays) [ 4 ]. The electric field disrupts the normal mitotic process for tumor cells and leads to cancer cell death [ 5 ]. In patients with recurrent glioblastoma brain tumors, TTFields has shown clinical efficacy comparable to that of active chemotherapies, without many of the side effects of chemotherapy [ 6 , 7 ]. TTFields was first FDA approved in the recurrent setting after it showed non-inferiority in a phase 3 trial compared to “physician’s best choice” treatment [ 8 ]. Subsequently, a first line randomized Phase 3 trial compared TTFields plus TMZ to TMZ alone among 695 glioblastoma patients who had completed radiochemotherapy. The TTFields treatment arm showed a significant improvement in both progression-free survival (median progression-free survival was 6.7 months in the TTFields plus TMZ group and 4.0 months in the TMZ alone group) and overall survival (median overall survival 20.9 months versus 16.0 months), leading to FDA approval of TTFields in the first line setting [ 9 , 10 ]. Side effects reported in the TTFields plus TMZ group were limited to mild to moderate skin toxicity under the transducer arrays [ 10 ]. Following FDA approval to use TTFields for glioblastoma and, subsequently, mesothelioma [ 11 ], the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) added TTFields to its guidelines for evidence-based management of new or recurrent glioblastoma in 2018 [ 12 , 13 ].

Despite regulatory and national guideline support for TTFields, evidence demonstrating improved survival with TTFields, no severe side effects from the device, and limited treatments for glioblastoma, not all patients who qualify for TTFields choose to use the device. Moreover, there has been reluctance among neuro-oncologists to adopt TTFields [ 12 ]. This qualitative study aimed to grow our understanding of glioblastoma patients’ decision on whether or not to use TTFields, the role of clinicians in their decisions, and clinicians’ views of TTFields.

Materials and methods

Patient enrollment.

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Northwestern University and all patients enrolled on study provided written informed consent prior to any study-related procedures. Patients with a glioblastoma receiving treatment at the Malnati Brain Tumor Institute at the Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University who had been offered treatment with TTFields and had decided whether to initiate TTFields therapy were eligible to participate in the study. Other eligibility criteria included: able to speak and understand English, age 18 or older, and cognitively able to complete a study interview. We aimed to interview up to 50 glioblastoma patients who had been offered TTFields. In 2020, 180 new glioblastoma patients were seen at the Malnati Brain Tumor Institute and 51 TTFields prescriptions were written.

Patients were enrolled consecutively between June of 2020 and February of 2021, the entirety of which occurred during Covid-19 pandemic; therefore, consenting and interviews occurred remotely. In the first month of the project, clinicians provided the names of glioblastoma patients who had been offered TTFields for study inclusion; subsequently, a study coordinator (co-author LL) identified glioblastoma patients in the electronic medical record who had been offered or who had decided to use TTFields. Clinicians then confirmed patients were physically and cognitively able to participant and the study coordinator contacted eligible patients via telephone, explained the study, and obtained informed consent electronically. The approximately 30-minute study interview was subsequently conducted via phone by the study coordinator, who had extensive experience conducting patient interviews. A semi-structured interview guide was used to gather patient input on their views of TTFields, factors that influenced their TTFields decision, and their perceptions of whether their clinician wanted them to use TTFields. Patients also completed the Control Preference Scale, which is a one-item measure of preferred role in medical decision making that has been tested and validated with cancer patients [ 14 , 15 , 16 ]. Patients received a $25 Visa gift card following participation. Interviews were audio recorded to ensure comprehensive capture of all relevant patient-reported information.

Clinician sample

Clinicians in the Malnati Brain Tumor Institute of Northwestern University who offer and prescribe TTFields therapy received an invitation via email to participate in a study interview. This included physicians (neuro-oncologists) and advanced practitioners (Advanced Practice Nurses and Physicians Assistants). All eligible physicians and advanced practitioners interviewed were specifically trained and certified to prescribe tumor treating fields by Novocure through the company-run training program. This is required to be able to prescribe this device to patients. Clinician participants provided verbal consent via telephone prior to participating in a telephone interview. As with the patient interviews, clinicians’ interviews were audio recorded. A semi-structured interview guide was used to gather their views of TTFields. Clinicians were not compensated for participating.

Data analysis

The interviewer entered detailed notes into an Excel database following each interview. The database became the basis for a preliminary analysis of each interview question. Notes for each question were reviewed by the study coordinator, an experienced qualitative analyst (co-author ML), and a qualitative researcher (co-author KK) to identify preliminary themes. Next, the three study team members reviewed the interview transcripts to finalize themes, confirm themes were comprehensive and reflected the data, and to identify supporting quotations.

Patient results

One-hundred and five glioblastoma patients were identified via physician recommendation or medical record review between June of 2020 and February of 2021. Of these, a total of 11 (10.5%) patients were deemed ineligible because they were not offered TTFields ( n = 2), had gone to another center for treatment ( n = 1), had entered hospice ( n = 6), or died prior to recruitment ( n = 2). Twenty-one patients (20.0%) were excluded per clinician recommendation. Reasons for clinician-recommended exclusion included cognitive issues, speech difficulties, and illness severity. Twenty (19.1%) patients were unresponsive to recruitment efforts, and 13 (12.4%) patients declined to participate. Individual interviews were conducted with 40 (38.1%) individuals with glioblastoma. Among the 40 participants (Table 1 ), the mean age was 53 years (range 21–77 years). Most participants were white (92.5%), married (80.0%), and male (60.0%). The study coordinator confirmed each patient’s TTFields status at the time of recruitment. Thirty-two participants (80.0%) chose to pursue TTFields therapy, while eight (20.0%) did not use TTFields. The TTFields group and the no-TTFields group were similar in age and gender. Patients who declined TTFields were less likely to use TTFields resources (Table 1 ); however, we would expect that TTFields users would be more apt to seek out information about TTFields.

Control Preference Scale results are shown in Table 2 . In both groups, patients most often preferred to make decisions for themselves after considering their doctors opinion ( n = 15, 46.9% among patients who utilized TTFields, n = 5, 62.5% among patients who declined TTFields). Six (18.8%) of the patients who chose TTFields preferred to have their doctor make their medical decisions either with consideration for the patient’s opinion ( n = 3, 9.4%) or on their own ( n = 3, 9.4%). In contrast, none of the patients who declined TTFields preferred to have their doctor make their decisions.

Participants who chose TTFields

Participants who chose TTFields noted downsides associated with the treatment. The most frequently mentioned downside of TTFields was the burden of changing the TTFields arrays, which happened frequently (every few days) and could be painful. The heat of the device on one’s head was also noted as a downside, along with the discomfort of wearing the cap and the burden on caregivers who assist them when changing their cap and arrays. Some users of TTFields experience skin reactions, such as blisters or itching. Participants also noted it could be difficult to sleep or shower with the device, and carrying the device was cumbersome.

However, many of the patients who chose TTFields came to accept the burdens of using the device. For example, some noted that shaving their head for TTFields was easy and/or worth the trouble. “The head shaving part was easy because I had lost most of my hair already.” Another participant said, “I used it (TTFields) for two years, and if they told me that I had to re-shave my head and use it longer, I would do it.” Likewise, participants who chose TTFields said that the appearance of the device could be bothersome, but they were not deterred by it. In fact, one participant had a positive experience due to the visible nature of TTFields: “Pretty much right after I was fitted for it, I think the next day, I was back at work. So, it was kind of awkward at first, but I actually had some good conversations with people about it in the days and weeks after that.”

For the patients who chose TTFields, the efficacy of TTFields was the most frequently cited reason for choosing to use the device. As shown in Table 3 , they described efficacy in several ways, including extension of life, shrinking one’s tumor, and the device being supported by clinical studies. Extension of life was cited by over a third ( n = 13, 40.6%) of those who chose TTFields (Table 3 ). One participant stated, “I don’t want to die. And I feel that if I don’t have this, that I will die.” Another participant spoke of the value of extending life even with potential negative effects: “Am I willing to be slightly inconvenienced for an additional five months of life? Yeah, I’ll go with that deal.” For others, clinical evidence supporting the efficacy of TTFields, particularly the extension of life, was pivotal in their decision to undergo TTFields. One participant stated that the biggest factor in their decision was “without question, FDA approved that this treatment does extend your life by a significant percentage.”

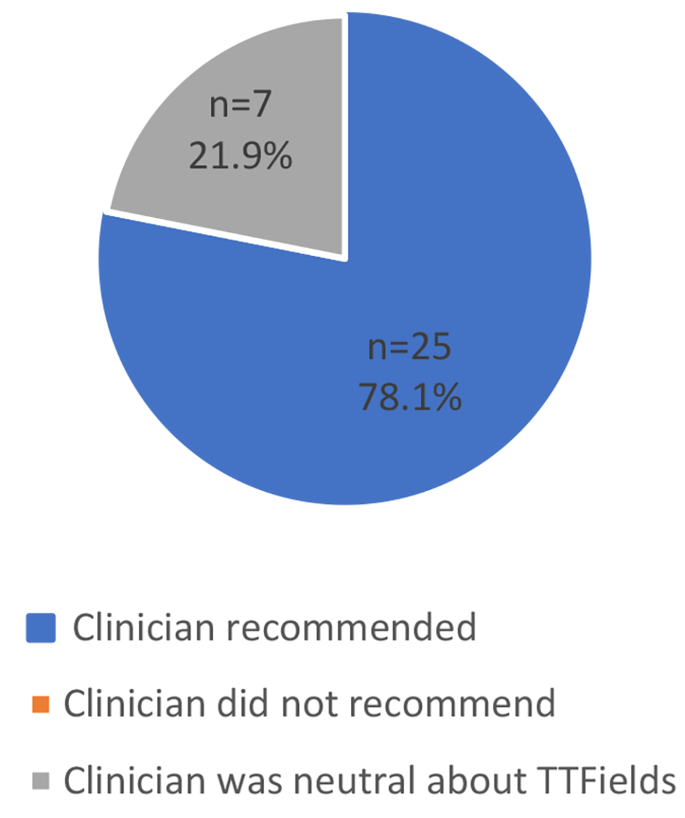

The second most influential factor reported by those who chose TTFields was their doctor’s opinion ( n = 9, 28.1%). As one participant stated, “We (participant and their spouse) absolutely believe in both the physicians who recommended it (TTFields). So, we really trust them a lot.” All participants who reported that their doctor’s opinion was the most influential factor in their decision to undergo TTFields also reported that their doctor recommended TTFields.

Familial considerations were cited as the most influential factor for four (12.5%) participants. Three of the four people in this group noted that they wanted to extend time with their families. Several other influences were mentioned by one person each (Table 3 ). For example, one participant said she chose TTFields after hearing about the experience of a family friend who had used TTFields and recommended it despite the inconveniences of wearing the device.

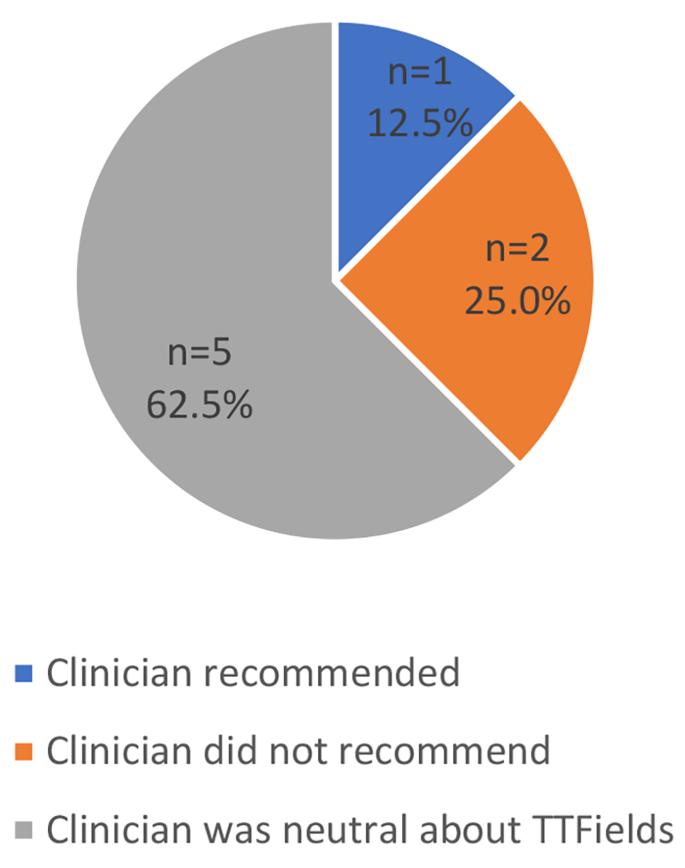

Participants who declined TTFields

For those glioblastoma patients who chose not to use TTFields, the most influential factor in their decision was the requirement to shave their head ( n = 4, 50.0%) (Table 4 ). “I know some people probably think that’s kind of silly, like, ‘You have cancer, so who cares if you have hair or not?’ But it’s just been really hard for me.” Another influential factor was the visibility of TTFields ( n = 3, 37.5%). For example, two participants did not like the idea of wearing the device at work. One of them said, “I was still working, and at that time, I did not share with them everything that was going on. So, it would have definitely exposed things, and who knows what would have happened after that.”

Other reasons for declining TTFields included the inconvenience of continuously wearing the device and carrying the battery pack. One participant expressed a personal concern about the idea of simultaneously receiving chemo and TTFields, while another reported that multiple doctors recommended against going on TTFields because of an existing surgical implant. Additional reasons for not going on TTFields included thinking it would not be needed, that it would not improve quality of life, and that the increased lifespan would not outweigh the negative impact of TTFields. As one participant explained:

Yes, there’s no negative impact, I guess, physically. However, the idea of having something attached to my head and then having to carry around the battery pack doesn’t really mesh well with my relatively physical quality of life…(TTFields) would actually have quite significant negative impacts on how I live my life.

Questions about TTFields