Home / Guides / Citation Guides / Citation Basics / Citing Evidence

Citing Evidence

In this article, you will learn how to cite the most relevant evidence for your audience.

Writing for a specific audience is an important skill. What you present in your writing and how you present it will vary depending on your intended audience.

Sometimes, you have to judge your audience’s level of understanding. For example, a general audience may not have as much background knowledge as an academic audience.

The UNC Writing Center provides a general overview of questions about your audience that you should consider. Click here and read the section, “How do I identify my audience and what they want from me?”

Addressing Audience Bias

In addition to knowledge, values, and concerns, your audience may also hold certain biases , or judgments and prejudices, about a topic.

Take, for example, the topic of the Revolutionary War. Your intended audience may be British economists who see the American Revolution as a rebellion, which hindered British imperialism around the world.

When writing for this audience, you still want to present your claims, reasoning, and evidence to support your argument about the American Revolution, but you don’t want to alienate your British audience. You will need to be sensitive in how you explain American success and its impact on the British Empire.

Quotes, Paraphrases & Audience

Using quotes and paraphrases is a terrific way to both support your argument and make it interesting for the audience to read. You should tailor the use of these quotes and paraphrases to your audience.

Evidence Sources & Audience

Whether you’re quoting or paraphrasing, the source of your evidence matters to your audience . Readers want to see credible sources that they trust.

For example, military historians may feel reassured to see citations from the Journal of Military History (the refereed academic publication for the Society for Military History) in your writing about the American Revolution.

They may be less persuaded by a quote from a historical reenactor’s blog or a more general source like The History Channel . Historical fiction or historical films created for entertainment likely will not impress them at all, unless you are creating a critique of those sources.

It can sometimes be helpful to create an annotated bibliography before writing your paper since the annotations you write will help you to summarize and evaluate the relevance and/or credibility of each of your sources.

Quoting/Paraphrasing with Audience in Mind

Choosing when to use quotes or paraphrases can depend on your audience as well.

If your audience wants details, if you want to grab the attention of your audience, or if audience bias may prevent acceptance of a more generalized statement, use a quote.

If your audience is new to the topic or a more general audience, if they will want to see your conclusions presented quickly, or if a quote would disrupt the reading of your text, a paraphrase is better.

Using Quotes and Paraphrases Effectively: Example

John Luzader, who has worked with the Department of Defense and the National Park Service, can be considered an expert who understands the technical aspects of military history.

Click here to read his “Thoughts on the Battle of Saratoga.” As you read, consider whether you would quote or paraphrase this text when using it as evidence for a school newspaper article explaining why the British surrendered.

Quotes and Paraphrases Example: Explained

A high school newspaper’s audience is usually intelligent and informed but not expert. Unless it is a military academy’s newspaper, it is unlikely that the audience has enough expertise to understand specific technical terms like “redoubt,” “intervisual,” or “British right and rear.”

For this audience, Luzader’s Thoughts on the Battle of Saratoga would work better as a paraphrase:

Military historian John Luzader (2010) argues that the British position on the field at Saratoga allowed the Americans to take the earthwork fort that protected the Redcoats and form a circle around the British, forcing their defeat.

Notice that the above paraphrase uses an in-text citation, which all paraphrases should. Because Luzader’s name is included in the sentence, we only need the year of publication (2010) in parentheses.

Relevant Evidence for Claims and Counterclaims

As a writer, you need to supply the most relevant evidence for claims and counterclaims based on what you know about your audience. Your claim is your position on the subject, while a counterclaim is a point that someone with an opposing view may raise.

Pointing out the strengths and limitations of your evidence in a way that anticipates the audience’s knowledge level, concerns, values, and possible biases helps you select the best evidence for your readers.

Relevant Evidence for Counterclaims: Example

Your audience’s concerns may include a counterclaim you must address. For example, your readers may think that the American Revolution cannot be considered a world war because it was a fight between one country and its colonies.

You should acknowledge these differences in beliefs with evidence, but be sure to return to your original claim, emphasizing why it is correct. Your acknowledgment may look like this (the counterclaim is in italics):

Although the American Revolution was primarily a battle between the British empire and its rebellious North American colonies , the foreign alliances made during the American Revolution helped the colonists survive the war and become a nation. The French Alliance of 1778 shows how foreign intervention was necessary to keep the United States going. As Office of the Historian for the U.S. State Department (2017) explains, “The single most important diplomatic success of the colonists during the War for Independence was the critical link they forged with France.” These alliances with other nations, who provided financial and military support to the colonists, expanded the scope of the Revolution to the point of being a world war.

Now you know how to select the best evidence to include in your writing! Remember to consider your audience, address counterclaims while not straying from your own claim, and use in-text citations for quotes and paraphrases.

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?

Citation Basics

Harvard Referencing

Plagiarism Basics

Plagiarism Checker

Upload a paper to check for plagiarism against billions of sources and get advanced writing suggestions for clarity and style.

Get Started

What this handout is about

This handout will provide a broad overview of gathering and using evidence. It will help you decide what counts as evidence, put evidence to work in your writing, and determine whether you have enough evidence. It will also offer links to additional resources.

Introduction

Many papers that you write in college will require you to make an argument ; this means that you must take a position on the subject you are discussing and support that position with evidence. It’s important that you use the right kind of evidence, that you use it effectively, and that you have an appropriate amount of it. If, for example, your philosophy professor didn’t like it that you used a survey of public opinion as your primary evidence in your ethics paper, you need to find out more about what philosophers count as good evidence. If your instructor has told you that you need more analysis, suggested that you’re “just listing” points or giving a “laundry list,” or asked you how certain points are related to your argument, it may mean that you can do more to fully incorporate your evidence into your argument. Comments like “for example?,” “proof?,” “go deeper,” or “expand” in the margins of your graded paper suggest that you may need more evidence. Let’s take a look at each of these issues—understanding what counts as evidence, using evidence in your argument, and deciding whether you need more evidence.

What counts as evidence?

Before you begin gathering information for possible use as evidence in your argument, you need to be sure that you understand the purpose of your assignment. If you are working on a project for a class, look carefully at the assignment prompt. It may give you clues about what sorts of evidence you will need. Does the instructor mention any particular books you should use in writing your paper or the names of any authors who have written about your topic? How long should your paper be (longer works may require more, or more varied, evidence)? What themes or topics come up in the text of the prompt? Our handout on understanding writing assignments can help you interpret your assignment. It’s also a good idea to think over what has been said about the assignment in class and to talk with your instructor if you need clarification or guidance.

What matters to instructors?

Instructors in different academic fields expect different kinds of arguments and evidence—your chemistry paper might include graphs, charts, statistics, and other quantitative data as evidence, whereas your English paper might include passages from a novel, examples of recurring symbols, or discussions of characterization in the novel. Consider what kinds of sources and evidence you have seen in course readings and lectures. You may wish to see whether the Writing Center has a handout regarding the specific academic field you’re working in—for example, literature , sociology , or history .

What are primary and secondary sources?

A note on terminology: many researchers distinguish between primary and secondary sources of evidence (in this case, “primary” means “first” or “original,” not “most important”). Primary sources include original documents, photographs, interviews, and so forth. Secondary sources present information that has already been processed or interpreted by someone else. For example, if you are writing a paper about the movie “The Matrix,” the movie itself, an interview with the director, and production photos could serve as primary sources of evidence. A movie review from a magazine or a collection of essays about the film would be secondary sources. Depending on the context, the same item could be either a primary or a secondary source: if I am writing about people’s relationships with animals, a collection of stories about animals might be a secondary source; if I am writing about how editors gather diverse stories into collections, the same book might now function as a primary source.

Where can I find evidence?

Here are some examples of sources of information and tips about how to use them in gathering evidence. Ask your instructor if you aren’t sure whether a certain source would be appropriate for your paper.

Print and electronic sources

Books, journals, websites, newspapers, magazines, and documentary films are some of the most common sources of evidence for academic writing. Our handout on evaluating print sources will help you choose your print sources wisely, and the library has a tutorial on evaluating both print sources and websites. A librarian can help you find sources that are appropriate for the type of assignment you are completing. Just visit the reference desk at Davis or the Undergraduate Library or chat with a librarian online (the library’s IM screen name is undergradref).

Observation

Sometimes you can directly observe the thing you are interested in, by watching, listening to, touching, tasting, or smelling it. For example, if you were asked to write about Mozart’s music, you could listen to it; if your topic was how businesses attract traffic, you might go and look at window displays at the mall.

An interview is a good way to collect information that you can’t find through any other type of research. An interview can provide an expert’s opinion, biographical or first-hand experiences, and suggestions for further research.

Surveys allow you to find out some of what a group of people thinks about a topic. Designing an effective survey and interpreting the data you get can be challenging, so it’s a good idea to check with your instructor before creating or administering a survey.

Experiments

Experimental data serve as the primary form of scientific evidence. For scientific experiments, you should follow the specific guidelines of the discipline you are studying. For writing in other fields, more informal experiments might be acceptable as evidence. For example, if you want to prove that food choices in a cafeteria are affected by gender norms, you might ask classmates to undermine those norms on purpose and observe how others react. What would happen if a football player were eating dinner with his teammates and he brought a small salad and diet drink to the table, all the while murmuring about his waistline and wondering how many fat grams the salad dressing contained?

Personal experience

Using your own experiences can be a powerful way to appeal to your readers. You should, however, use personal experience only when it is appropriate to your topic, your writing goals, and your audience. Personal experience should not be your only form of evidence in most papers, and some disciplines frown on using personal experience at all. For example, a story about the microscope you received as a Christmas gift when you were nine years old is probably not applicable to your biology lab report.

Using evidence in an argument

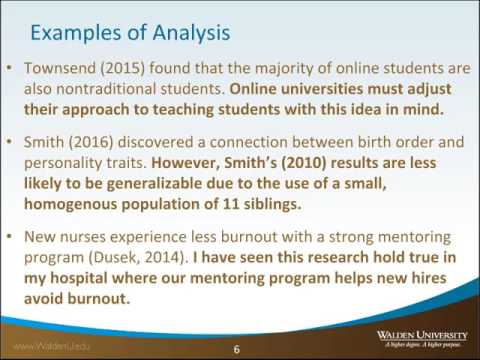

Does evidence speak for itself.

Absolutely not. After you introduce evidence into your writing, you must say why and how this evidence supports your argument. In other words, you have to explain the significance of the evidence and its function in your paper. What turns a fact or piece of information into evidence is the connection it has with a larger claim or argument: evidence is always evidence for or against something, and you have to make that link clear.

As writers, we sometimes assume that our readers already know what we are talking about; we may be wary of elaborating too much because we think the point is obvious. But readers can’t read our minds: although they may be familiar with many of the ideas we are discussing, they don’t know what we are trying to do with those ideas unless we indicate it through explanations, organization, transitions, and so forth. Try to spell out the connections that you were making in your mind when you chose your evidence, decided where to place it in your paper, and drew conclusions based on it. Remember, you can always cut prose from your paper later if you decide that you are stating the obvious.

Here are some questions you can ask yourself about a particular bit of evidence:

- OK, I’ve just stated this point, but so what? Why is it interesting? Why should anyone care?

- What does this information imply?

- What are the consequences of thinking this way or looking at a problem this way?

- I’ve just described what something is like or how I see it, but why is it like that?

- I’ve just said that something happens—so how does it happen? How does it come to be the way it is?

- Why is this information important? Why does it matter?

- How is this idea related to my thesis? What connections exist between them? Does it support my thesis? If so, how does it do that?

- Can I give an example to illustrate this point?

Answering these questions may help you explain how your evidence is related to your overall argument.

How can I incorporate evidence into my paper?

There are many ways to present your evidence. Often, your evidence will be included as text in the body of your paper, as a quotation, paraphrase, or summary. Sometimes you might include graphs, charts, or tables; excerpts from an interview; or photographs or illustrations with accompanying captions.

When you quote, you are reproducing another writer’s words exactly as they appear on the page. Here are some tips to help you decide when to use quotations:

- Quote if you can’t say it any better and the author’s words are particularly brilliant, witty, edgy, distinctive, a good illustration of a point you’re making, or otherwise interesting.

- Quote if you are using a particularly authoritative source and you need the author’s expertise to back up your point.

- Quote if you are analyzing diction, tone, or a writer’s use of a specific word or phrase.

- Quote if you are taking a position that relies on the reader’s understanding exactly what another writer says about the topic.

Be sure to introduce each quotation you use, and always cite your sources. See our handout on quotations for more details on when to quote and how to format quotations.

Like all pieces of evidence, a quotation can’t speak for itself. If you end a paragraph with a quotation, that may be a sign that you have neglected to discuss the importance of the quotation in terms of your argument. It’s important to avoid “plop quotations,” that is, quotations that are just dropped into your paper without any introduction, discussion, or follow-up.

Paraphrasing

When you paraphrase, you take a specific section of a text and put it into your own words. Putting it into your own words doesn’t mean just changing or rearranging a few of the author’s words: to paraphrase well and avoid plagiarism, try setting your source aside and restating the sentence or paragraph you have just read, as though you were describing it to another person. Paraphrasing is different than summary because a paraphrase focuses on a particular, fairly short bit of text (like a phrase, sentence, or paragraph). You’ll need to indicate when you are paraphrasing someone else’s text by citing your source correctly, just as you would with a quotation.

When might you want to paraphrase?

- Paraphrase when you want to introduce a writer’s position, but their original words aren’t special enough to quote.

- Paraphrase when you are supporting a particular point and need to draw on a certain place in a text that supports your point—for example, when one paragraph in a source is especially relevant.

- Paraphrase when you want to present a writer’s view on a topic that differs from your position or that of another writer; you can then refute writer’s specific points in your own words after you paraphrase.

- Paraphrase when you want to comment on a particular example that another writer uses.

- Paraphrase when you need to present information that’s unlikely to be questioned.

When you summarize, you are offering an overview of an entire text, or at least a lengthy section of a text. Summary is useful when you are providing background information, grounding your own argument, or mentioning a source as a counter-argument. A summary is less nuanced than paraphrased material. It can be the most effective way to incorporate a large number of sources when you don’t have a lot of space. When you are summarizing someone else’s argument or ideas, be sure this is clear to the reader and cite your source appropriately.

Statistics, data, charts, graphs, photographs, illustrations

Sometimes the best evidence for your argument is a hard fact or visual representation of a fact. This type of evidence can be a solid backbone for your argument, but you still need to create context for your reader and draw the connections you want them to make. Remember that statistics, data, charts, graph, photographs, and illustrations are all open to interpretation. Guide the reader through the interpretation process. Again, always, cite the origin of your evidence if you didn’t produce the material you are using yourself.

Do I need more evidence?

Let’s say that you’ve identified some appropriate sources, found some evidence, explained to the reader how it fits into your overall argument, incorporated it into your draft effectively, and cited your sources. How do you tell whether you’ve got enough evidence and whether it’s working well in the service of a strong argument or analysis? Here are some techniques you can use to review your draft and assess your use of evidence.

Make a reverse outline

A reverse outline is a great technique for helping you see how each paragraph contributes to proving your thesis. When you make a reverse outline, you record the main ideas in each paragraph in a shorter (outline-like) form so that you can see at a glance what is in your paper. The reverse outline is helpful in at least three ways. First, it lets you see where you have dealt with too many topics in one paragraph (in general, you should have one main idea per paragraph). Second, the reverse outline can help you see where you need more evidence to prove your point or more analysis of that evidence. Third, the reverse outline can help you write your topic sentences: once you have decided what you want each paragraph to be about, you can write topic sentences that explain the topics of the paragraphs and state the relationship of each topic to the overall thesis of the paper.

For tips on making a reverse outline, see our handout on organization .

Color code your paper

You will need three highlighters or colored pencils for this exercise. Use one color to highlight general assertions. These will typically be the topic sentences in your paper. Next, use another color to highlight the specific evidence you provide for each assertion (including quotations, paraphrased or summarized material, statistics, examples, and your own ideas). Lastly, use another color to highlight analysis of your evidence. Which assertions are key to your overall argument? Which ones are especially contestable? How much evidence do you have for each assertion? How much analysis? In general, you should have at least as much analysis as you do evidence, or your paper runs the risk of being more summary than argument. The more controversial an assertion is, the more evidence you may need to provide in order to persuade your reader.

Play devil’s advocate, act like a child, or doubt everything

This technique may be easiest to use with a partner. Ask your friend to take on one of the roles above, then read your paper aloud to them. After each section, pause and let your friend interrogate you. If your friend is playing devil’s advocate, they will always take the opposing viewpoint and force you to keep defending yourself. If your friend is acting like a child, they will question every sentence, even seemingly self-explanatory ones. If your friend is a doubter, they won’t believe anything you say. Justifying your position verbally or explaining yourself will force you to strengthen the evidence in your paper. If you already have enough evidence but haven’t connected it clearly enough to your main argument, explaining to your friend how the evidence is relevant or what it proves may help you to do so.

Common questions and additional resources

- I have a general topic in mind; how can I develop it so I’ll know what evidence I need? And how can I get ideas for more evidence? See our handout on brainstorming .

- Who can help me find evidence on my topic? Check out UNC Libraries .

- I’m writing for a specific purpose; how can I tell what kind of evidence my audience wants? See our handouts on audience , writing for specific disciplines , and particular writing assignments .

- How should I read materials to gather evidence? See our handout on reading to write .

- How can I make a good argument? Check out our handouts on argument and thesis statements .

- How do I tell if my paragraphs and my paper are well-organized? Review our handouts on paragraph development , transitions , and reorganizing drafts .

- How do I quote my sources and incorporate those quotes into my text? Our handouts on quotations and avoiding plagiarism offer useful tips.

- How do I cite my evidence? See the UNC Libraries citation tutorial .

- I think that I’m giving evidence, but my instructor says I’m using too much summary. How can I tell? Check out our handout on using summary wisely.

- I want to use personal experience as evidence, but can I say “I”? We have a handout on when to use “I.”

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Lunsford, Andrea A., and John J. Ruszkiewicz. 2016. Everything’s an Argument , 7th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Miller, Richard E., and Kurt Spellmeyer. 2016. The New Humanities Reader , 5th ed. Boston: Cengage.

University of Maryland. 2019. “Research Using Primary Sources.” Research Guides. Last updated October 28, 2019. https://lib.guides.umd.edu/researchusingprimarysources .

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- Skip to Content

- Skip to Main Navigation

- Skip to Search

Indiana University Bloomington Indiana University Bloomington IU Bloomington

- Mission, Vision, and Inclusive Language Statement

- Locations & Hours

- Undergraduate Employment

- Graduate Employment

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Newsletter Archive

- Support WTS

- Schedule an Appointment

- Online Tutoring

- Before your Appointment

- WTS Policies

- Group Tutoring

- Students Referred by Instructors

- Paid External Editing Services

- Writing Guides

- Scholarly Write-in

- Dissertation Writing Groups

- Journal Article Writing Groups

- Early Career Graduate Student Writing Workshop

- Workshops for Graduate Students

- Teaching Resources

- Syllabus Information

- Course-specific Tutoring

- Nominate a Peer Tutor

- Tutoring Feedback

- Schedule Appointment

- Campus Writing Program

Writing Tutorial Services

Using evidence.

Like a lawyer in a jury trial, a writer must convince her audience of the validity of her argument by using evidence effectively. As a writer, you must also use evidence to persuade your readers to accept your claims. But how do you use evidence to your advantage? By leading your reader through your reasoning.

The types of evidence you use change from discipline to discipline--you might use quotations from a poem or a literary critic, for example, in a literature paper; you might use data from an experiment in a lab report.

The process of putting together your argument is called analysis --it interprets evidence in order to support, test, and/or refine a claim . The chief claim in an analytical essay is called the thesis . A thesis provides the controlling idea for a paper and should be original (that is, not completely obvious), assertive, and arguable. A strong thesis also requires solid evidence to support and develop it because without evidence, a claim is merely an unsubstantiated idea or opinion.

This Web page will cover these basic issues (you can click or scroll down to a particular topic):

- Incorporating evidence effectively.

- Integrating quotations smoothly.

- Citing your sources.

Incorporating Evidence Into Your Essay

When should you incorporate evidence.

Once you have formulated your claim, your thesis (see the WTS pamphlet, " How to Write a Thesis Statement ," for ideas and tips), you should use evidence to help strengthen your thesis and any assertion you make that relates to your thesis. Here are some ways to work evidence into your writing:

- Offer evidence that agrees with your stance up to a point, then add to it with ideas of your own.

- Present evidence that contradicts your stance, and then argue against (refute) that evidence and therefore strengthen your position.

- Use sources against each other, as if they were experts on a panel discussing your proposition.

- Use quotations to support your assertion, not merely to state or restate your claim.

Weak and Strong Uses of Evidence

In order to use evidence effectively, you need to integrate it smoothly into your essay by following this pattern:

- State your claim.

- Give your evidence, remembering to relate it to the claim.

- Comment on the evidence to show how it supports the claim.

To see the differences between strong and weak uses of evidence, here are two paragraphs.

Weak use of evidence

Today, we are too self-centered. Most families no longer sit down to eat together, preferring instead to eat on the go while rushing to the next appointment (Gleick 148). Everything is about what we want.

This is a weak example of evidence because the evidence is not related to the claim. What does the claim about self-centeredness have to do with families eating together? The writer doesn't explain the connection.

The same evidence can be used to support the same claim, but only with the addition of a clear connection between claim and evidence, and some analysis of the evidence cited.

Stronger use of evidence

Today, Americans are too self-centered. Even our families don't matter as much anymore as they once did. Other people and activities take precedence. In fact, the evidence shows that most American families no longer eat together, preferring instead to eat on the go while rushing to the next appointment (Gleick 148). Sit-down meals are a time to share and connect with others; however, that connection has become less valued, as families begin to prize individual activities over shared time, promoting self-centeredness over group identity.

This is a far better example, as the evidence is more smoothly integrated into the text, the link between the claim and the evidence is strengthened, and the evidence itself is analyzed to provide support for the claim.

Using Quotations: A Special Type of Evidence

One effective way to support your claim is to use quotations. However, because quotations involve someone else's words, you need to take special care to integrate this kind of evidence into your essay. Here are two examples using quotations, one less effective and one more so.

Ineffective Use of Quotation

Today, we are too self-centered. "We are consumers-on-the-run . . . the very notion of the family meal as a sit-down occasion is vanishing. Adults and children alike eat . . . on the way to their next activity" (Gleick 148). Everything is about what we want.

This example is ineffective because the quotation is not integrated with the writer's ideas. Notice how the writer has dropped the quotation into the paragraph without making any connection between it and the claim. Furthermore, she has not discussed the quotation's significance, which makes it difficult for the reader to see the relationship between the evidence and the writer's point.

A More Effective Use of Quotation

Today, Americans are too self-centered. Even our families don't matter as much any more as they once did. Other people and activities take precedence, as James Gleick says in his book, Faster . "We are consumers-on-the-run . . . the very notion of the family meal as a sit-down occasion is vanishing. Adults and children alike eat . . . on the way to their next activity" (148). Sit-down meals are a time to share and connect with others; however, that connection has become less valued, as families begin to prize individual activities over shared time, promoting self-centeredness over group identity.

The second example is more effective because it follows the guidelines for incorporating evidence into an essay. Notice, too, that it uses a lead-in phrase (". . . as James Gleick says in his book, Faster ") to introduce the direct quotation. This lead-in phrase helps to integrate the quotation with the writer's ideas. Also notice that the writer discusses and comments upon the quotation immediately afterwards, which allows the reader to see the quotation's connection to the writer's point.

REMEMBER: Discussing the significance of your evidence develops and expands your paper!

Citing Your Sources

Evidence appears in essays in the form of quotations and paraphrasing. Both forms of evidence must be cited in your text. Citing evidence means distinguishing other writers' information from your own ideas and giving credit to your sources. There are plenty of general ways to do citations. Note both the lead-in phrases and the punctuation (except the brackets) in the following examples:

Quoting: According to Source X, "[direct quotation]" ([date or page #]).

Paraphrasing: Although Source Z argues that [his/her point in your own words], a better way to view the issue is [your own point] ([citation]).

Summarizing: In her book, Source P's main points are Q, R, and S [citation].

Your job during the course of your essay is to persuade your readers that your claims are feasible and are the most effective way of interpreting the evidence.

Questions to Ask Yourself When Revising Your Paper

- Have I offered my reader evidence to substantiate each assertion I make in my paper?

- Do I thoroughly explain why/how my evidence backs up my ideas?

- Do I avoid generalizing in my paper by specifically explaining how my evidence is representative?

- Do I provide evidence that not only confirms but also qualifies my paper's main claims?

- Do I use evidence to test and evolve my ideas, rather than to just confirm them?

- Do I cite my sources thoroughly and correctly?

Produced by Writing Tutorial Services, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN

Writing Tutorial Services social media channels

- Departments and Units

- Majors and Minors

- LSA Course Guide

- LSA Gateway

Search: {{$root.lsaSearchQuery.q}}, Page {{$root.page}}

- Accessibility

- Undergraduates

- Instructors

- Alums & Friends

- ★ Writing Support

- Minor in Writing

- First-Year Writing Requirement

- Transfer Students

- Writing Guides

- Peer Writing Consultant Program

- Upper-Level Writing Requirement

- Writing Prizes

- International Students

- ★ The Writing Workshop

- Dissertation ECoach

- Fellows Seminar

- Dissertation Writing Groups

- Rackham / Sweetland Workshops

- Dissertation Writing Institute

- Guides to Teaching Writing

- Teaching Support and Services

- Support for FYWR Courses

- Support for ULWR Courses

- Writing Prize Nominating

- Alums Gallery

- Commencement Archive

- Giving Opportunities

- How Do I Effectively Integrate Textual Evidence?

- How Do I Make Sure I Understand an Assignment?

- How Do I Decide What I Should Argue?

- How Can I Create Stronger Analysis?

- How Do I Write a Great Title?

- What Exactly is an Abstract?

- How Do I Present Findings From My Experiment in a Report?

- What is a Run-on Sentence & How Do I Fix It?

- How Do I Check the Structure of My Argument?

- How Do I Write an Intro, Conclusion, & Body Paragraph?

- How Do I Incorporate Quotes?

- How Can I Create a More Successful Powerpoint?

- How Can I Create a Strong Thesis?

- How Can I Write More Descriptively?

- How Do I Incorporate a Counterargument?

- How Do I Check My Citations?

See the bottom of the main Writing Guides page for licensing information.

Academic writing often requires students to use evidence, and learning how to use evidence effectively is an important skill for college writers to master. Often, the evidence college writers are asked to use comes from their textbooks, course readings, or other written work by professional scholars. It is important to learn how to use these writings responsibly and accurately.

General Considerations

There are three methods of incorporating the writing of others into your paper as evidence:

- quotation , which is anything from a word to several sentences taken word-for-word from the original source and enclosed in quotation marks

- paraphrase , which is a rephrasing in your own voice and sentence structure of one portion of the original source and is about the same length as the original sentence or sentences you are paraphrasing

- summary , which is shorter than the original source and gives the text’s central idea in your own words

Some words to use in signal phrases are argues, asserts, contends, emphasizes, explains, observes, suggests, writes.

In what follows, you will learn some strategies for using these methods of incorporating evidence into your paper.

In Practice

Quoting When you use a q uotation as evidence, you should integrate it into your own writing using a “signal phrase.” Take, for example, this quotation, taken from page 418 of the essay “Prejudice and the Individual” by Gordon Allport: “Much prejudice is caught rather than directly taught.” Here are three ways to integrate Allport’s quotation into a sentence of your own with a signal phrase:

Allport claims that “prejudice is caught rather than directly taught” (418). “Much prejudice is caught rather than directly taught,” claims Allport (418). “Much prejudice,” Allport claims, “is caught rather than directly taught” (418).

You can adapt a quotation to fit your own paragraph and sentence structure by making small changes to words and indicating those changes with square brackets. Say, for example, you liked this quotation from Allport:

“It should be added that overgeneralized prejudgments of this sort are prejudices only if they are not reversible when exposed to new knowledge” (417).

However, you want to apply Allport’s words to a specific example of your own. You could adapt the quotation like this:

The young man in my example was not prejudiced, according to Allport’s definition; his opinion was “reversible when [he was] exposed to new knowledge” (417).

You can also use ellipses to indicate that you have left irrelevant words out of a quotation. Again, say you wanted to use this quotation from Allport:

“The best opinion today says that if we eliminate discrimination, then—as people become acquainted with one another on equal terms—attitudes are likely to change, perhaps more rapidly than through the continued preaching or teaching of tolerance” (417).

But the middle part is less important to your paper than what Allport says at the start and the end. You could modify the quotation like this:

“The best opinion today says that if we eliminate discrimination . . . attitudes are likely to change, perhaps more rapidly than through the continued preaching or teaching of tolerance” (417).

Longer quotations must be formatted in a special way; usually, they are indented from the left margin and/or single-spaced. Depending on what citation style you use, guidelines differ regarding what defines a long quotation and how a long quotation should be formatted. Typically, a quotation of four or five lines is considered long.

Paraphrasing To paraphrase a source for use as evidence, you should use as little of the original language as possible and put the passage in your own voice and sentence structure. Also, because paraphrasing involves wrapping your words around someone else’s idea, people often forget to give credit to the author. Even though a paraphrase is in your words, it is not your idea. Remember to cite your source when you paraphrase. Here is another quotation from Allport and an example of weak and strong paraphrase:

“Education combats easy overgeneralizations, and as the educational level rises we find a reduction in stereotyped thinking” (Allport 422).

WEAK PARAPHRASE: Learning fights against stereotypes, and as more people are more educated we notice a decrease in prejudice (422).

STRONG PARAPHRASE: Allport explains that the more we learn, the harder we will find it to make unfair assumptions about groups of people, which means as more people pursue more education, prejudice decreases (422).

In the weak example above, you can see the sentence structure in the paraphrase is very similar to the quotation—notice, for instance, the use in both the original sentence and the weak paraphrase of a comma plus the conjunction “and.” Also, the replacement of Allport’s words with synonyms makes the paraphrase too close to the original—Allport’s “education” is replaced with “learning” in the paraphrase; his “combats” is exchanged for “fights”; “overgeneralizations” becomes “stereotypes.” The strong example above does a better job of restating Allport’s idea in a new sentence structure and without simple word substitution. Also, notice the weak paraphrase does not give Allport credit by mentioning him, but the strong one does.

Summarizing When you summarize another writer’s idea to use as evidence in a paper of your own, you are taking the essence of the writer’s idea and stating it more briefly, with less detail and explanation, than in the original. You may summarize an article or a chapter, or even a book, in a sentence, a paragraph, a page, or more—the purpose of your summary should dictate how specific you are. Summaries should be mostly in your own words, but often summaries include quotations or paraphrases when it is necessary to highlight a certain key point. When you are writing a summary, you need to be very careful not to use the original writer’s words without putting those words in quotation marks. You also need to be sure that when you summarize, you are fairly representing the original writer’s main idea. Here is a paragraph from Allport and examples of weak and strong summary:

“While discrimination ultimately rests on prejudice, the two processes are not identical. Discrimination denies people their natural or legal rights because of their membership in some unfavored group. Many people discriminate automatically without being prejudiced; and others, the “gentle people of prejudice,” feel irrational aversion, but are careful not to show it in discriminatory behavior. Yet in general, discrimination reinforces prejudices, and prejudices provide rationalizations for discrimination. The two concepts are most distinct when it comes to seeking remedies. The corrections for discrimination are legal, or lie in a direct change of social practices; whereas the remedy for prejudice lies in education and the conversion of attitudes. The best opinion today says that if we eliminate discrimination, then—as people become acquainted with one another on equal terms—attitudes are likely to change, perhaps more rapidly than through the continued preaching or teaching of tolerance.” (Allport 417)

WEAK SUMMARY: Discrimination is when people are denied their rights because they belong to some unfavored group, and it is addressed with legal action or a change in social practices. Eliminating discrimination from society would have a drastic effect on social attitudes overall, according to Allport (417).

STRONG SUMMARY: Allport explains that discrimination occurs when an individual is refused rights because he or she belongs to a group which is the object of prejudice. In this way, discrimination reinforces prejudice, but if instances of discrimination are ruled illegal or seen as socially unacceptable, prejudice will likely decrease along with discrimination (417).

You will notice that the weak summary above uses exact words and phrases from the source (“unfavored group,” “social practices”) and also some words and phrases very close to the original (“when people are denied,” “eliminating discrimination”). It does not effectively restate the original in different language. It also does not fairly represent the complete idea of the source paragraph: it does not explain the relationship between discrimination and prejudice, an important part of what Allport says. The strong example does a better job using independent language and fairly conveying Allport’s point.

How to choose which method of incorporating evidence to use These methods of incorporating evidence into your paper are helpful in different ways. Think carefully about what you need each piece of evidence to do for you in your paper, then choose the method that most suits your needs.

You should use a quotation if

- you are relying on the reputation of the writer of the original source to give authority or credibility to your paper.

- the original wording is so remarkable that paraphrasing would diminish it.

A paraphrase is a good choice if

- you need to provide a supporting fact or detail but the original writer’s exact words are not important.

- you need to use just one specific idea from a source and the rest of the source is not as important.

Summary is useful when

- you need to give an overview of a source to orient your reader.

- you want to provide background that leads up to the point of your paper.

Last but certainly not least, remember that anytime you use another person’s ideas or language, you must give credit to that person. If you do not know the name of the person whose idea or language you are using, you must still give credit by referring to a title or any such available information. You should always check with your instructor to see what method of citing and documenting sources you should use. The examples on this handout are cited using MLA style.

The sample text in these exercises is Holly Devor’s “Gender Role Behaviors and Attitudes.”

1. Read the paragraph from Devor below, then identify which summary of it is weak and which is strong.

“Body postures and demeanors which communicate subordinate status and vulnerability to trespass through a message of "no threat" make people appear to be feminine. They demonstrate subordination through a minimizing of spatial use: people appear to be feminine when they keep their arms closer to their bodies, their legs closer together, and their torsos and heads less vertical than do masculine-looking individuals. People also look feminine when they point their toes inward and use their hands in small or childlike gestures.” (486)

A. Devor argues that body language suggests a great deal about gender and power in our society. People who minimize the body space they occupy and whose physical gestures are minimal and unobtrusive appear inferior and feminine (486).

B. Devor says that body postures and demeanors that imply weakness make people look feminine. Minimizing the space one takes up and using infantile gestures also makes one appear feminine (486).

2. Read the sentence from Devor below, then identify which paraphrase of it is weak and which is strong.

“They demonstrate subordination through a minimizing of spatial use: people appear to be feminine when they keep their arms closer to their bodies, their legs closer together, and their torsos and heads less vertical than do masculine-looking individuals.” (486)

A. Devor explains that people demonstrate a lesser position by using less space, keeping arms close, legs together, and head less upright (486).

B. According to Devor, taking up less space with one’s body—keeping arms and legs close and hunching to reduce height—makes one appear inferior and implies femininity (486).

3. The quotations of Devor below, taken from the paragraph in exercise 1, contain technical errors. Identify and correct them.

A. Devor argues that “[b]ody postures and demeanors which communicate subordinate status and vulnerability make people appear to be feminine” (486).

B. The actress looked particularly feminine because she “point their toes inward and use their hands in small or childlike gestures” (486).

C. Devor claims that “using their hands in small or childlike gestures” makes people look feminine (486).

Answers: 1. A. STRONG B. WEAK – This example uses too many exact words and phrases from the original.

2. A. WEAK – This example uses too many exact words and phrases from the source, and its sentence structure is also too close to the original. B. STRONG

3. A. Devor argues that “[b]ody postures and demeanors which communicate subordinate status and vulnerability . . . make people appear to be feminine.” B. The actress looked particularly feminine because she “point[s her] toes inward and use[s her] hands in small or childlike gestures.” C. Devor claims that “us[ing] their hands in small or childlike gestures” makes people look feminine.

Allport, Gordon, “Prejudice and the Individual,” in The Borozoi College Reader , 6th ed. Eds. Charles Muscatine and Marlene Griffith (New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1988): 416-22.

Devor, Holly, “Gender Role Behaviors and Attitudes,” in Signs of Life in the USA: Readings on Popular Culture for Writers , 4th ed. Eds. Sonia Maasik and Jack Solomon (New York: Bedford / St Martin's, 2003): 484-89.

- Information For

- Prospective Students

- Current Students

- Faculty and Staff

- Alumni and Friends

- More about LSA

- How Do I Apply?

- LSA Opportunity Hub

- LSA Magazine

- Student Resources

- Academic Advising

- Global Studies

- Social Media

- Update Contact Info

- Privacy Statement

- Report Feedback

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Introduce Evidence: 41 Effective Phrases & Examples

Research requires us to scrutinize information and assess its credibility. Accordingly, when we think about various phenomena, we examine empirical data and craft detailed explanations justifying our interpretations. An essential component of constructing our research narratives is thus providing supporting evidence and examples.

The type of proof we provide can either bolster our claims or leave readers confused or skeptical of our analysis. Therefore, it’s crucial that we use appropriate, logical phrases that guide readers clearly from one idea to the next. In this article, we explain how evidence and examples should be introduced according to different contexts in academic writing and catalog effective language you can use to support your arguments, examples included.

When to Introduce Evidence and Examples in a Paper

Evidence and examples create the foundation upon which your claims can stand firm. Without proof, your arguments lack credibility and teeth. However, laundry listing evidence is as bad as failing to provide any materials or information that can substantiate your conclusions. Therefore, when you introduce examples, make sure to judiciously provide evidence when needed and use phrases that will appropriately and clearly explain how the proof supports your argument.

There are different types of claims and different types of evidence in writing. You should introduce and link your arguments to evidence when you

- state information that is not “common knowledge”;

- draw conclusions, make inferences, or suggest implications based on specific data;

- need to clarify a prior statement, and it would be more effectively done with an illustration;

- need to identify representative examples of a category;

- desire to distinguish concepts; and

- emphasize a point by highlighting a specific situation.

Introductory Phrases to Use and Their Contexts

To assist you with effectively supporting your statements, we have organized the introductory phrases below according to their function. This list is not exhaustive but will provide you with ideas of the types of phrases you can use.

Although any research author can make use of these helpful phrases and bolster their academic writing by entering them into their work, before submitting to a journal, it is a good idea to let a professional English editing service take a look to ensure that all terms and phrases make sense in the given research context. Wordvice offers paper editing , thesis editing , and dissertation editing services that help elevate your academic language and make your writing more compelling to journal authors and researchers alike.

For more examples of strong verbs for research writing , effective transition words for academic papers , or commonly confused words , head over to the Wordvice Academic Resources website.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

MLA In-Text Citations: The Basics

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

MLA (Modern Language Association) style is most commonly used to write papers and cite sources within the liberal arts and humanities. This resource, updated to reflect the MLA Handbook (9 th ed.), offers examples for the general format of MLA research papers, in-text citations, endnotes/footnotes, and the Works Cited page.

Guidelines for referring to the works of others in your text using MLA style are covered throughout the MLA Handbook and in chapter 7 of the MLA Style Manual . Both books provide extensive examples, so it's a good idea to consult them if you want to become even more familiar with MLA guidelines or if you have a particular reference question.

Basic in-text citation rules

In MLA Style, referring to the works of others in your text is done using parenthetical citations . This method involves providing relevant source information in parentheses whenever a sentence uses a quotation or paraphrase. Usually, the simplest way to do this is to put all of the source information in parentheses at the end of the sentence (i.e., just before the period). However, as the examples below will illustrate, there are situations where it makes sense to put the parenthetical elsewhere in the sentence, or even to leave information out.

General Guidelines

- The source information required in a parenthetical citation depends (1) upon the source medium (e.g. print, web, DVD) and (2) upon the source’s entry on the Works Cited page.

- Any source information that you provide in-text must correspond to the source information on the Works Cited page. More specifically, whatever signal word or phrase you provide to your readers in the text must be the first thing that appears on the left-hand margin of the corresponding entry on the Works Cited page.

In-text citations: Author-page style

MLA format follows the author-page method of in-text citation. This means that the author's last name and the page number(s) from which the quotation or paraphrase is taken must appear in the text, and a complete reference should appear on your Works Cited page. The author's name may appear either in the sentence itself or in parentheses following the quotation or paraphrase, but the page number(s) should always appear in the parentheses, not in the text of your sentence. For example:

Both citations in the examples above, (263) and (Wordsworth 263), tell readers that the information in the sentence can be located on page 263 of a work by an author named Wordsworth. If readers want more information about this source, they can turn to the Works Cited page, where, under the name of Wordsworth, they would find the following information:

Wordsworth, William. Lyrical Ballads . Oxford UP, 1967.

In-text citations for print sources with known author

For print sources like books, magazines, scholarly journal articles, and newspapers, provide a signal word or phrase (usually the author’s last name) and a page number. If you provide the signal word/phrase in the sentence, you do not need to include it in the parenthetical citation.

These examples must correspond to an entry that begins with Burke, which will be the first thing that appears on the left-hand margin of an entry on the Works Cited page:

Burke, Kenneth. Language as Symbolic Action: Essays on Life, Literature, and Method . University of California Press, 1966.

In-text citations for print sources by a corporate author

When a source has a corporate author, it is acceptable to use the name of the corporation followed by the page number for the in-text citation. You should also use abbreviations (e.g., nat'l for national) where appropriate, so as to avoid interrupting the flow of reading with overly long parenthetical citations.

In-text citations for sources with non-standard labeling systems

If a source uses a labeling or numbering system other than page numbers, such as a script or poetry, precede the citation with said label. When citing a poem, for instance, the parenthetical would begin with the word “line”, and then the line number or range. For example, the examination of William Blake’s poem “The Tyger” would be cited as such:

The speaker makes an ardent call for the exploration of the connection between the violence of nature and the divinity of creation. “In what distant deeps or skies. / Burnt the fire of thine eyes," they ask in reference to the tiger as they attempt to reconcile their intimidation with their relationship to creationism (lines 5-6).

Longer labels, such as chapters (ch.) and scenes (sc.), should be abbreviated.

In-text citations for print sources with no known author

When a source has no known author, use a shortened title of the work instead of an author name, following these guidelines.

Place the title in quotation marks if it's a short work (such as an article) or italicize it if it's a longer work (e.g. plays, books, television shows, entire Web sites) and provide a page number if it is available.

Titles longer than a standard noun phrase should be shortened into a noun phrase by excluding articles. For example, To the Lighthouse would be shortened to Lighthouse .

If the title cannot be easily shortened into a noun phrase, the title should be cut after the first clause, phrase, or punctuation:

In this example, since the reader does not know the author of the article, an abbreviated title appears in the parenthetical citation, and the full title of the article appears first at the left-hand margin of its respective entry on the Works Cited page. Thus, the writer includes the title in quotation marks as the signal phrase in the parenthetical citation in order to lead the reader directly to the source on the Works Cited page. The Works Cited entry appears as follows:

"The Impact of Global Warming in North America." Global Warming: Early Signs . 1999. www.climatehotmap.org/. Accessed 23 Mar. 2009.

If the title of the work begins with a quotation mark, such as a title that refers to another work, that quote or quoted title can be used as the shortened title. The single quotation marks must be included in the parenthetical, rather than the double quotation.

Parenthetical citations and Works Cited pages, used in conjunction, allow readers to know which sources you consulted in writing your essay, so that they can either verify your interpretation of the sources or use them in their own scholarly work.

Author-page citation for classic and literary works with multiple editions

Page numbers are always required, but additional citation information can help literary scholars, who may have a different edition of a classic work, like Marx and Engels's The Communist Manifesto . In such cases, give the page number of your edition (making sure the edition is listed in your Works Cited page, of course) followed by a semicolon, and then the appropriate abbreviations for volume (vol.), book (bk.), part (pt.), chapter (ch.), section (sec.), or paragraph (par.). For example:

Author-page citation for works in an anthology, periodical, or collection

When you cite a work that appears inside a larger source (for instance, an article in a periodical or an essay in a collection), cite the author of the internal source (i.e., the article or essay). For example, to cite Albert Einstein's article "A Brief Outline of the Theory of Relativity," which was published in Nature in 1921, you might write something like this:

See also our page on documenting periodicals in the Works Cited .

Citing authors with same last names

Sometimes more information is necessary to identify the source from which a quotation is taken. For instance, if two or more authors have the same last name, provide both authors' first initials (or even the authors' full name if different authors share initials) in your citation. For example:

Citing a work by multiple authors

For a source with two authors, list the authors’ last names in the text or in the parenthetical citation:

Corresponding Works Cited entry:

Best, David, and Sharon Marcus. “Surface Reading: An Introduction.” Representations , vol. 108, no. 1, Fall 2009, pp. 1-21. JSTOR, doi:10.1525/rep.2009.108.1.1

For a source with three or more authors, list only the first author’s last name, and replace the additional names with et al.

Franck, Caroline, et al. “Agricultural Subsidies and the American Obesity Epidemic.” American Journal of Preventative Medicine , vol. 45, no. 3, Sept. 2013, pp. 327-333.

Citing multiple works by the same author

If you cite more than one work by an author, include a shortened title for the particular work from which you are quoting to distinguish it from the others. Put short titles of books in italics and short titles of articles in quotation marks.

Citing two articles by the same author :

Citing two books by the same author :

Additionally, if the author's name is not mentioned in the sentence, format your citation with the author's name followed by a comma, followed by a shortened title of the work, and, when appropriate, the page number(s):

Citing multivolume works

If you cite from different volumes of a multivolume work, always include the volume number followed by a colon. Put a space after the colon, then provide the page number(s). (If you only cite from one volume, provide only the page number in parentheses.)

Citing the Bible

In your first parenthetical citation, you want to make clear which Bible you're using (and underline or italicize the title), as each version varies in its translation, followed by book (do not italicize or underline), chapter, and verse. For example:

If future references employ the same edition of the Bible you’re using, list only the book, chapter, and verse in the parenthetical citation:

John of Patmos echoes this passage when describing his vision (Rev. 4.6-8).

Citing indirect sources

Sometimes you may have to use an indirect source. An indirect source is a source cited within another source. For such indirect quotations, use "qtd. in" to indicate the source you actually consulted. For example:

Note that, in most cases, a responsible researcher will attempt to find the original source, rather than citing an indirect source.

Citing transcripts, plays, or screenplays

Sources that take the form of a dialogue involving two or more participants have special guidelines for their quotation and citation. Each line of dialogue should begin with the speaker's name written in all capitals and indented half an inch. A period follows the name (e.g., JAMES.) . After the period, write the dialogue. Each successive line after the first should receive an additional indentation. When another person begins speaking, start a new line with that person's name indented only half an inch. Repeat this pattern each time the speaker changes. You can include stage directions in the quote if they appear in the original source.

Conclude with a parenthetical that explains where to find the excerpt in the source. Usually, the author and title of the source can be given in a signal phrase before quoting the excerpt, so the concluding parenthetical will often just contain location information like page numbers or act/scene indicators.

Here is an example from O'Neill's The Iceman Cometh.

WILLIE. (Pleadingly) Give me a drink, Rocky. Harry said it was all right. God, I need a drink.

ROCKY. Den grab it. It's right under your nose.

WILLIE. (Avidly) Thanks. (He takes the bottle with both twitching hands and tilts it to his lips and gulps down the whiskey in big swallows.) (1.1)

Citing non-print or sources from the Internet

With more and more scholarly work published on the Internet, you may have to cite sources you found in digital environments. While many sources on the Internet should not be used for scholarly work (reference the OWL's Evaluating Sources of Information resource), some Web sources are perfectly acceptable for research. When creating in-text citations for electronic, film, or Internet sources, remember that your citation must reference the source on your Works Cited page.

Sometimes writers are confused with how to craft parenthetical citations for electronic sources because of the absence of page numbers. However, these sorts of entries often do not require a page number in the parenthetical citation. For electronic and Internet sources, follow the following guidelines:

- Include in the text the first item that appears in the Work Cited entry that corresponds to the citation (e.g. author name, article name, website name, film name).

- Do not provide paragraph numbers or page numbers based on your Web browser’s print preview function.

- Unless you must list the Web site name in the signal phrase in order to get the reader to the appropriate entry, do not include URLs in-text. Only provide partial URLs such as when the name of the site includes, for example, a domain name, like CNN.com or Forbes.com, as opposed to writing out http://www.cnn.com or http://www.forbes.com.

Miscellaneous non-print sources

Two types of non-print sources you may encounter are films and lectures/presentations:

In the two examples above “Herzog” (a film’s director) and “Yates” (a presentor) lead the reader to the first item in each citation’s respective entry on the Works Cited page:

Herzog, Werner, dir. Fitzcarraldo . Perf. Klaus Kinski. Filmverlag der Autoren, 1982.

Yates, Jane. "Invention in Rhetoric and Composition." Gaps Addressed: Future Work in Rhetoric and Composition, CCCC, Palmer House Hilton, 2002. Address.

Electronic sources

Electronic sources may include web pages and online news or magazine articles:

In the first example (an online magazine article), the writer has chosen not to include the author name in-text; however, two entries from the same author appear in the Works Cited. Thus, the writer includes both the author’s last name and the article title in the parenthetical citation in order to lead the reader to the appropriate entry on the Works Cited page (see below).

In the second example (a web page), a parenthetical citation is not necessary because the page does not list an author, and the title of the article, “MLA Formatting and Style Guide,” is used as a signal phrase within the sentence. If the title of the article was not named in the sentence, an abbreviated version would appear in a parenthetical citation at the end of the sentence. Both corresponding Works Cited entries are as follows:

Taylor, Rumsey. "Fitzcarraldo." Slant , 13 Jun. 2003, www.slantmagazine.com/film/review/fitzcarraldo/. Accessed 29 Sep. 2009.

"MLA Formatting and Style Guide." The Purdue OWL , 2 Aug. 2016, owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/747/01/. Accessed 2 April 2018.

Multiple citations

To cite multiple sources in the same parenthetical reference, separate the citations by a semi-colon:

Time-based media sources

When creating in-text citations for media that has a runtime, such as a movie or podcast, include the range of hours, minutes and seconds you plan to reference. For example: (00:02:15-00:02:35).

When a citation is not needed

Common sense and ethics should determine your need for documenting sources. You do not need to give sources for familiar proverbs, well-known quotations, or common knowledge (For example, it is expected that U.S. citizens know that George Washington was the first President.). Remember that citing sources is a rhetorical task, and, as such, can vary based on your audience. If you’re writing for an expert audience of a scholarly journal, for example, you may need to deal with expectations of what constitutes “common knowledge” that differ from common norms.

Other Sources

The MLA Handbook describes how to cite many different kinds of authors and content creators. However, you may occasionally encounter a source or author category that the handbook does not describe, making the best way to proceed can be unclear.

In these cases, it's typically acceptable to apply the general principles of MLA citation to the new kind of source in a way that's consistent and sensible. A good way to do this is to simply use the standard MLA directions for a type of source that resembles the source you want to cite.

You may also want to investigate whether a third-party organization has provided directions for how to cite this kind of source. For example, Norquest College provides guidelines for citing Indigenous Elders and Knowledge Keepers —an author category that does not appear in the MLA Handbook . In cases like this, however, it's a good idea to ask your instructor or supervisor whether using third-party citation guidelines might present problems.

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Finance and Business

- Legal Matters

- Contracts and Legal Agreements

How to Introduce Evidence in an Essay

Last Updated: December 5, 2023

This article was co-authored by Tristen Bonacci . Tristen Bonacci is a Licensed English Teacher with more than 20 years of experience. Tristen has taught in both the United States and overseas. She specializes in teaching in a secondary education environment and sharing wisdom with others, no matter the environment. Tristen holds a BA in English Literature from The University of Colorado and an MEd from The University of Phoenix. This article has been viewed 234,262 times.

When well integrated into your argument, evidence helps prove that you've done your research and thought critically about your topic. But what's the best way to introduce evidence so it feels seamless and has the highest impact? There are actually quite a few effective strategies you can use, and we've rounded up the best ones for you here. Try some of the tips below to introduce evidence in your essay and make a persuasive argument.

Setting up the Evidence

- You can use 1-2 sentences to set up the evidence, if needed, but usually more concise you are, the better.

- For example, you may make an argument like, “Desire is a complicated, confusing emotion that causes pain to others.”

- Or you may make an assertion like, “The treatment of addiction must consider root cause issues like mental health and poor living conditions.”

- For example, you may write, “The novel explores the theme of adolescent love and desire.”

- Or you may write, “Many studies show that addiction is a mental health issue.”

Putting in the Evidence

- For example, you may use an introductory clause like, “According to Anne Carson…”, "In the following chart...," “The author states…," "The survey shows...." or “The study argues…”

- Place a comma after the introductory clause if you are using a quote. For example, “According to Anne Carson, ‘Desire is no light thing" or "The study notes, 'levels of addiction rise as levels of poverty and homelessness also rise.'"

- A list of introductory clauses can be found here: https://student.unsw.edu.au/introducing-quotations-and-paraphrases .

- For example, you may write, “In the novel, Carson is never shy about how her characters express desire for each other: ‘When they made love/ Geryon liked to touch in slow succession each of the bones of Herakles' back…’”

- Or you may write, "The study charts the rise in addiction levels, concluding: 'There is a higher level of addiction in specific areas of the United States.'"

- For example, you may write, “Carson views events as inevitable, as man moving through time like “a harpoon,” much like the fates of her characters.”

- Or you may write, "The chart indicates the rising levels of addiction in young people, an "epidemic" that shows no sign of slowing down."

- For example, you may write in the first mention, “In Anne Carson’s The Autobiography of Red , the color red signifies desire, love, and monstrosity.” Or you may write, "In the study Addiction Rates conducted by the Harvard Review...".

- After the first mention, you can write, “Carson states…” or “The study explores…”.

- If you are citing the author’s name in-text as part of your citation style, you do not need to note their name in the text. You can just use the quote and then place the citation at the end.

- If you are paraphrasing a source, you may still use quotation marks around any text you are lifting directly from the source.

- For example, you may write, “In the novel, the characters express desire for each other: ‘When they made love/ Geryon liked to touch in slow succession each of the bones of Herakles' back (Carson, 48).”

- Or you may write, "Based on the data in the graph below, the study shows the 'intersection between opioid addiction and income' (Branson, 10)."

- If you are using footnotes or endnotes, make sure you use the appropriate citation for each piece of evidence you place in your essay.

- You may also mention the title of the work or source you are paraphrasing or summarizing and the author's name in the paraphrase or summary.

- For example, you may write a paraphrase like, "As noted in various studies, the correlation between addiction and mental illness is often ignored by medical health professionals (Deder, 10)."

- Or you may write a summary like, " The Autobiography of Red is an exploration of desire and love between strange beings, what critics have called a hybrid work that combines ancient meter with modern language (Zambreno, 15)."

- The only time you should place 2 pieces of evidence together is when you want to directly compare 2 short quotes (each less than 1 line long).

- Your analysis should then include a complete compare and contrast of the 2 quotes to show you have thought critically about them both.

Analyzing the Evidence

- For example, you may write, “In the novel, Carson is never shy about how her characters express desire for each other: ‘When they made love/ Geryon liked to touch in slow succession each of the bones of Herakles' back (Carson, 48). The connection between Geryon and Herakles is intimate and gentle, a love that connects the two characters in a physical and emotional way.”

- Or you may write, "In the study Addiction Rates conducted by the Harvard Review, the data shows a 50% rise in addiction levels in specific areas across the United States. The study illustrates a clear connection between addiction levels and communities where income falls below the poverty line and there is a housing shortage or crisis."

- For example, you may write, “Carson’s treatment of the relationship between Geryon and Herakles can be linked back to her approach to desire as a whole in the novel, which acts as both a catalyst and an impediment for her characters.”

- Or you may write, "The survey conducted by Dr. Paula Bronson, accompanied by a detailed academic dissertation, supports the argument that addiction is not a stand alone issue that can be addressed in isolation."