What Is Heaven? A Complete Guide

Heaven is a very common term in the Bible, used for the sky; for the space beyond our atmosphere; and for God’s dwelling place. Jesus frequently talks about the Kingdom of Heaven as a present reality with a future final fulfillment.

Table of Contents

Definition of Heaven

- Biblical Three-Level View of Heaven

Heaven as the Dwelling of God

- The Kingdom of Heaven: Present Day Reality

Heaven in the Bible

Heaven as the new earth for believers, common misconceptions about heaven.

- What is Heaven? A Summary

What is heaven? And what is heaven like? These are common questions. With many different answers. But what does the Bible itself have to say about heaven?

In the Old Testament the Hebrew word šāmayim is the primary word translated as heaven. The NIV Word Study Dictionary defines this word as “region above the earth: the heavens: place of the stars, sky, air; heaven: the invisible realm of God.” As you can see, it has a variety of usages.

In the New Testament, the Greek word ouranos is the primary word translated as heaven. This word is defined as “sky, air, firmament , any area above the earth; heaven(s), the place of sun, moon, and stars; heaven, in which God dwells.” Like šāmayim , this word is used in a variety of ways.

Both of these words refer to the physical realm that we live in. But they also refer to the supernatural realm of God. I suspect that is because there was not a clear distinction between the two in the Hebrew mind. The sky is ‘up there.’ But God’s throne is also ‘up there,’ beyond the stars ( Job 22:12 ). In ancient Hebrew thought, the heavens consist of everything that is ‘up there.’

The Biblical Three-Level View of Heaven

There is no description of how the Hebrews viewed the heaven in the Scripture. But from the way the term is used, it appears like they divided heaven into three regions. The air the birds flew in; the realm of the sun, moon, and stars; and God’s dwelling place.

In Matthew 5:26 Jesus tells his disciples to “look at the birds of the air.” The word ‘air’ here is ouranos , or heaven. Here, as in a few other places, it is referring to the earth’s atmosphere. It is a physical place, a part of the natural world.

In Psalm 19:1-6 , David’s psalm begins by expressing the glory of God revealed in the heavens. This passage is referring to the celestial bodies, especially the sun. These heavens were visible to humans, but beyond the reach of the birds that flew through the sky.

For the ancients, the third level of heaven was the dwelling place of God, or the gods. This third level of heaven is beyond the sun, moon, and stars. While eventually it came to be thought of as a spiritual place, it was still ‘up there,’ higher than the other heavens.

In Psalm 11:4 , Psalm 103:19 , and Isaiah 66:1 we read that God’s throne is in heaven. In Isaiah 6:1 , Isaiah has a vision of God sitting on his throne, high and exalted. In 1 Kings 8:27-53 , Solomon identifies heaven as God’s dwelling place. At the beginning of this passage Solomon acknowledges that even the highest heaven cannot contain God.

In 2 Corinthians 12:1-10 Paul shares an experience of being caught up to the third heaven, the dwelling of God. He identifies this place as being synonymous with Paradise, the Paradise that Jesus promised to share with the repentant thief on the cross.

The Kingdom of Heaven : Present Day Reality

Jesus came proclaiming the coming of the kingdom. Matthew calls it the Kingdom of Heaven . It is a spiritual kingdom that Christ rules over. A kingdom that includes all the redeemed. While this kingdom has eschatological ramifications, it is a kingdom with present day reality.

This kingdom that Jesus proclaims reflects a dramatic shift in thought. The coming kingdom had been envisioned as a physical earthly kingdom centered on Jerusalem. But the kingdom Jesus proclaims was a spiritual kingdom without an earthly center.

In Matthew 13 there are a series of parables. Most of these parables start with the expression “the kingdom of heaven is like.” But for the most part, they are not what we might expect. Rather than describing a future abode of believers, they describe heaven as a present reality. A kingdom that is growing; one that is worth all we have; and impacted by unbelievers.

Even though heaven is in some sense a present reality that we are experiencing, there is more to come. As believers we look forward to life beyond this earth and in the fragile tents in which we currently dwell ( 2 Corinthians 5:1-5 ). But what is that heaven like?

Unfortunately, the Scripture does not give us a lot of information about what awaits us. But there are a few things we know about heaven.

3 Ways God's Rainbow Represents His Loving Grace

- We know that we will experience it with transformed bodies ( 1 Corinthians 15:35-57 ), not as disembodied spirits.

- That we will in some way be like Christ ( 1 John 3:2-3 ), and in some way we will be like the angels ( Matthew 22:30 ).

- The pains of this life will be left behind ( Revelation 21:4 ).

- Believers from every nation will praise God together ( Revelation 7:9 ).

- We will be with the Lord forever ( 1 Thessalonians 4:17 ), and we will share in the glory of Christ ( Rom. 8:17 ).

But what heaven itself is like is unknown. 1 Corinthians 2:9 does give us a clue though, “What no eye has seen, what no ear has heard, and what no human mind has conceived – the things God has prepared for those who love him.” What God has prepared for us is beyond our ability to grasp now. It is indescribable to our human minds. So, while we may not know what heaven is like, we can look forward to it with expectation and joy.

Revelation 21:1-5 paints a picture of our future. In it the heaven and earth we inhabit pass away. In their place are a new heaven and earth. And then the New Jerusalem, later described as the bride of Christ ( Revelation 21:9 ) descends from heaven to earth. Finally, the announcement from the throne of God is that he will now dwell among us.

This chapter in Revelation is similar in many ways to the description of Eden, the initial home of humanity. It seems like our end is a return to our beginnings, to what we were created to be in the first place.

If this view of Revelation 21:1-5 is correct, then it would appear that our abode in heaven is temporary. And that our permanent home is on a newly recreated earth.

1. Many Mansions

There are a couple of passages that are, at least in popular thought, considered to be descriptive of heaven. In John 14:2 the KJV tells us that there in the Father’s house there are many mansions. Most modern translations use rooms or dwelling places rather than mansions. But it is still common to heard older people talk about their mansion in heaven. I suspect there will be no mansions.

2. Streets of Gold and Gates of Pearls

Another passage frequently used to describe heaven comes from the 21st and 22nd chapters of Revelation. These chapters describe an immense city with streets of gold and gates of pearls. But if you look at Revelation 21:9-10 , you will find that this chapter is describing the bride of Christ, the church, rather than heaven. It is a symbolic description of the glory of Christ’s bride, and God’s presence within.

The Pearly Gates would also seem come out of this passage in Revelation. The New Jerusalem, the bride of Christ, is described as having gates of pearls with the names of the 12 tribes written on them. But, again, this is descriptive of the bride of Christ rather than heaven.

What Is Heaven?

Heaven is a very common term in the Bible. You will find it used for the sky; for the space beyond our atmosphere; and for God’s dwelling place. Jesus frequently talks about the Kingdom of Heaven as a present reality with a future final fulfillment. And heaven is frequently associated with the home of believers when we leave this life. A home in Christ, in the presence of God.

But that ‘home in heaven’ that we look forward to is not described in the pages of Scripture. It is beyond our ability to grasp. But whether our ultimate destiny is in heaven, or in a recreated heaven and earth, it will be glorious beyond the ability of words to describe.

Ed Jarrett is a long time follower of Jesus and a member of Sylvan Way Baptist Church. He has been a Bible teacher for over 40 years and regularly blogs at A Clay Jar . You can also follow him on Twitter or Facebook . Ed is married, the father of two, and grandfather of two lovely girls. He is retired and currently enjoys his gardens and backpacking.

Photo Credit: Unsplash/Chetan Menaria

What Does the Bible Say About How Angels Can Affect Our Everyday Life?

8 Prayers to Guide You Through Each Day of Holy Week

What is Palm Sunday? Bible Story and Meaning Today

The Seven Last Words of Jesus from the Cross Explained

Morning Prayers to Start Your Day with God

10 Palm Sunday Hymns to Start Holy Week

6 Prayers for the Upcoming Presidential Election

That is why Jesus went through all that anguish. He did it for all those who would come to faith in the world. We were the joy set before Him.

Bible Baseball

Play now...

Saintly Millionaire

Bible Jeopardy

Bible Trivia By Category

Bible Trivia Challenge

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Heaven and Hell in Christian Thought

Behind the various Christian ideas about heaven and hell lies the more basic belief that our lives extend beyond the grave (see the entry on afterlife ). For suppose that our lives do not extend beyond the grave. In addition to excluding a variety of ideas about reincarnation and karma, this would also preclude the very possibility of future compensation of any kind for those who experience horrendous evil during their earthly lives. Indeed, despite their profound differences, many Christians (though perhaps not all) and many atheists can presumably agree on one thing at least. If a young girl should be brutally raped and murdered and this should be the end of the story for the child, then a supremely powerful, benevolent, and just God would not exist. An atheist may seriously doubt whether any future compensation would suffice to justify a supreme being’s decision to permit such an evil in the first place. But the point is that even many Christians would concede that, apart from an afterlife, such an evil would constitute overwhelming evidence against the existence of God; some might even concede that such an evil would be logically (or metaphysically) inconsistent with God’s existence as well.

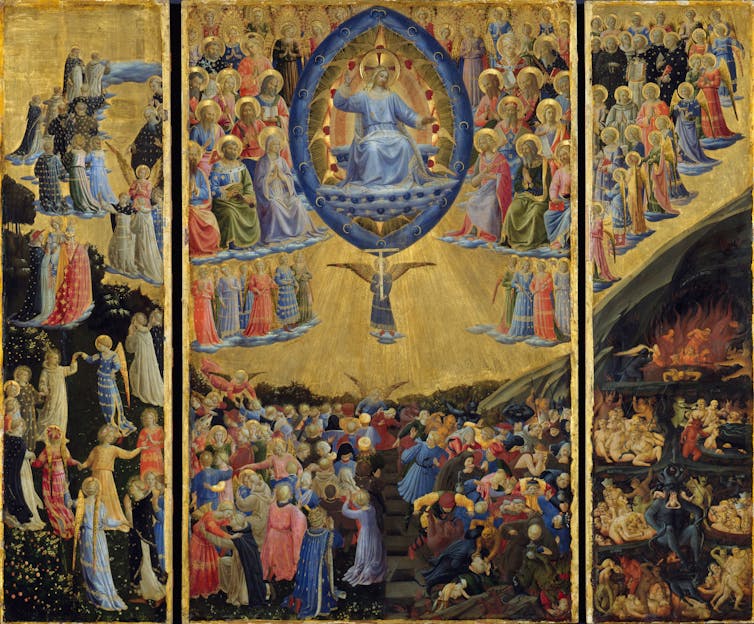

It is hardly surprising, then, that a belief in an afterlife should be an important part of the Christian tradition. Even if our lives do extend beyond the grave, however, the question remains concerning the nature of the future in store for us on the other side, and the various Christian views about heaven and hell are proposed answers to this question. According to a relatively common view in the wider Christian culture, heaven and hell are essentially deserved compensations for the kind of earthly lives we live. Good people go to heaven as a deserved reward for a virtuous life, and bad people go to hell as a just punishment for an immoral life; in that way, the scales of justice are sometimes thought to balance. But virtually all Christian theologians regard such a view, however common it may be in the popular culture, as overly simplistic and unsophisticated; the biblical perspective, as they see it, is far more subtly nuanced than that.

When we turn to the theological and philosophical literature in the Christian tradition, we encounter, as we would in any of the other great religious traditions as well, a bewildering variety of different (and often inconsistent) theological views. The views about hell in particular include very different conceptions of divine love, divine justice, and divine grace, very different ideas about free will and its role (if any) in determining a person’s ultimate destiny, very different understandings of moral evil and the purpose of punishment, and very different views about the nature of moral responsibility and the possibility of inherited guilt. There is also this further complication: in the Abrahamic family of monotheistic religions to which Christianity belongs (along with Judaism and Islam), theological reflection often includes an interpretation of various texts thought to be both sacred and authoritative. But the meaning of these texts, particularly when read in their original languages, is rarely transparent to all reasonable interpreters; that is, not even all who regard a relevant text as authoritative seem able to agree on its correct interpretation. Still, despite this bewildering diversity of theological opinion, there may be a relatively easy way to identify three primary eschatological views within the Christian religion and thus to organize the various ideas about heaven and hell around these three primary views.

1.1 Postulating a Final and Irreversible Division within the Human Race

1.2 restricting the scope of god’s love, 2.1 retributivist objections, 2.2 challenging the retributive theory itself, 3.1 moral freedom and rationality, 3.2 moral freedom and irreparable harm, 4.1 divine grace and the inclusive nature of love, 4.2 universalism and human freedom, 4.3 the limits of god’s power to preserve human freedom, 5.1 freedom in heaven, 5.2 concerning the misery of loved ones in hell, 5.3 concerning the supposed tedium of immortality, other internet resources, related entries, 1. three primary eschatological views.

Let theism in general be the belief that a supremely powerful, supremely wise, and supremely good (loving, just, merciful) personal being exists as the Creator of the universe. Christian theism is, of course, more specific than that, and Christian theists typically make the following two-fold assumption: first, that the highest possible good for created persons (true blessedness, if you will) requires that they enter into a proper relationship (or even a kind of union) with their Creator, and second, that a complete severance from the divine nature, without even an implicit experience of God (see note 11 ) would be a terrifying evil. As C. S. Lewis once put it, union with the divine “Nature is bliss and separation from it [an objective] horror” (1955, 232). Although most Christians would probably agree with this, some may want additional clarity on the nature of the union and the separation in question here. But in any case, whereas heaven is in general thought of as a realm in which people experience the bliss of perfect fellowship and harmony with God and with each other, hell is in general thought of as a realm in which people experience the greatest possible estrangement from God, the greatest possible sense of alienation, and perhaps also an intense hatred of everyone including themselves.

The ideas of heaven and hell are also closely associated with the religious idea of salvation , which in turn rests upon a theological interpretation of the human condition. Even the non-religious can perhaps agree that, for whatever reason, we humans begin our earthly lives with many imperfections and with no (conscious) awareness of God. We also emerge and begin making choices in a context of ambiguity, ignorance, and misperception, and behind our earliest choices lie a host of genetically determined inclinations and environmental (including social and cultural) influences. As young children, moreover, we initially pursue our own needs and interests as we perceive (or misperceive) them. So the context in which we humans emerge with a first person perspective and then begin developing into minimally rational agents virtually guarantees, it seems, that we would repeatedly misconstrue our own interests and pursue them in misguided ways; it also includes many sources of misery, at least some of which—the horror of war, horrifying examples of inhumanity to children, people striving to benefit themselves at the expense of others, etc.—are the product of misguided human choices. But other sources include such non-moral evils as natural disasters, sickness, and especially physical death itself.

Clearly, then, we all encounter in our natural environment many threats to our immediate welfare and many obstacles, some of our own making and some not, to enduring happiness. The Christian interpretation of this human condition thus postulates an initial estrangement from God, and the Christian religion then offers a prescription for how we can be saved from such estrangement; it teaches in particular that “God was in Christ, reconciling the world unto himself” (2 Cor. 5:19a—KJV). But Christians also disagree among themselves concerning the extent and ultimate success of God’s saving activity among human beings. Some believe that God will positively reject unrepentant sinners after a given deadline, typically thought of as the moment of physical death, and actively punish them forever after; others believe that God would never reject any of God’s own loved ones even though some of them may freely reject God forever, thereby placing themselves in a kind of self-created hell; and still others believe that God’s redemptive love will triumph in the end and will successfully bring reconciliation to all of those whom God has loved into existence in the first place. So one way to organize our thinking here is against the backdrop of the following inconsistent set of three propositions:

- All human sinners are equal objects of God’s redemptive love in the sense that God wills or aims to win over each one of them over time and thereby to prepare each one of them for the bliss of union with the divine nature.

- God’s redemptive love will triumph in the end and successfully win over each and every object of that love, thereby preparing each one of them for the bliss of union with the divine nature.

- Some human sinners will never be reconciled to God and will therefore remain separated from the divine nature forever.

If this set of propositions is logically inconsistent, as it surely is, then at least one proposition in the set is false. In no way does it follow, of course, that only one proposition in the set is false, and neither does it follow that at least two of them are true. But if someone does accept any two of these propositions, as virtually every mainline Christian theologian does, then such a person has no choice but to reject the third. [ 1 ] It is typically rather easy, moreover, to determine which proposition a given theologian ultimately rejects, and we can therefore classify theologians according to which of these propositions they do reject. So that leaves exactly three primary eschatological views. Because the Augustinians, named after St. Augustine of Hippo (354–430), believe both that God’s redemptive (or electing) love will triumph in the end (proposition (2)) and that some human sinners will never be reconciled to God (proposition (3)), they finally reject the idea that God’s redemptive love extends to all human sinners equally (proposition (1)); because the Arminians, named after Jacobus Arminius (1560–1609) for his opposition to the Augustinian understanding of limited election, believe both that God’s redemptive love extends to all human sinners equally (proposition (1)) and that some of these sinners will never be reconciled to God (proposition (3)), they finally reject the idea that God’s redemptive love will triumph in the end (proposition (2)); and finally, because the Christian universalists believe both that God’s redemptive love extends to all human sinners equally (proposition (1)) and that this love will triumph in the end (proposition (2)), they finally reject altogether the idea that some human sinners will never be reconciled to God (proposition (3)).

So here, then, are three quite different systems of theology. According to Augustinian theology, God’s redemptive love cannot be thwarted forever, but the scope of that love is restricted to a limited elect. According to Arminian theology, God’s redemptive love extends to all human sinners equally, but that love can be thwarted by factors, such as certain human choices, over which God has no direct causal control. And according to the theology of Christian universalism, God’s redemptive love extends to all human sinners equally and God’s will to save each one of them cannot be thwarted forever. Accordingly, a question that may now arise is, “Which system of theology best preserves the praiseworthy character and the glory of God?”

Some may already have observed that the third proposition in our inconsistent triad, namely

- Some humans will never be reconciled to God and will therefore remain separated from the divine nature forever,

is fairly unspecific concerning the fate of the wicked and the import of separation from God. For if we think of such separation as a state of being estranged or alienated from God, or if we think of it as simply the absence of a loving union with God, then (3) is equally consistent with many different conceptions of hell, some arguably milder than others. It is equally consistent, for example, with the idea that hell is a realm where the wicked receive retribution in the form of everlasting torment, with the idea that they will simply be annihilated in the end, with the idea that they create their own hell by rejecting God, and with the idea that God will simply make them as comfortable as possible in hell even as God graciously limits the harm they can do to each other (see Stump 1986). This lack of specificity is by design. For however one understands the fate of those who supposedly remain separated from God forever , such a fate will entail something like (3). Alternatively, anyone who rejects (3) will likewise reject the idea of everlasting torment as well as any of the supposedly milder conceptions of an everlasting separation from God.

Now when the Fifth General Council of the Christian church condemned the doctrine of universal reconciliation in 553 CE, it did not, strictly speaking, commit the institutional church of that day to a doctrine of everlasting conscious torment in hell. But it did commit the church to a final and irreversible division within the human race between those who will be saved, on the one hand, and those who will be hopelessly lost forever, on the other. So anyone who accepted the Council’s decision on this point, as most major theologians over the subsequent thousand years did, inevitably confronted an obvious question. If there is to be such a final and irreversible division within the human race, just what accounts for it? According to the Augustinians, the explanation lies in the mystery of God’s freedom to extend the divine love and mercy to a limited elect and to withhold it from the rest of humanity; but according to the Arminians, the explanation lies in our human free choices. Thanks to God’s grace, we ultimately determine our own destiny in heaven or hell.

These two very different explanations for a final and irrevocable division within the human race, where some end up in heaven and others in hell, also reflect profound disagreements over the nature of divine grace. Because the Augustinians hold that, in our present condition at least, God owes us nothing, they also believe that the grace God confers upon a limited elect is utterly gratuitous and supererogatory. As John Calvin put it, “For as Jacob, deserving nothing by good works, is taken into grace, Esau, as yet undefiled by any crime, is hated” (Calvin 1960, Bk. III, Ch. XXIII, sec. 12). But the Arminians reject such a doctrine as inherently unjust; it is simply unjust, they insist, for God to do for some, namely the elect, what God refuses to do for others, particularly since the elect have done nothing to deserve their special treatment. The Arminians therefore hold that God offers his grace to all human beings, though many are those who freely reject it and eventually seal their fate in hell forever. But for their part, the Augustinians counter that this Arminian explanation in terms of human free will contradicts St. Paul’s clear teaching that salvation is wholly a matter of grace: “For by grace you have been saved through faith,” Paul declared, “and this [the faith] is not your own doing; it is the gift of God—not the result of works, so that no one may boast” (Eph. 2:8–9). The Augustinians also challenge the Arminians with the following question: if the ultimate difference between the saved and the lost lies in the superior free choices that the saved have made during their earthly lives, then why shouldn’t they take credit for this difference or even boast about it? Why shouldn’t they say, “Well, at least I’m not as bad as those miserable people in hell who were so stupid as to have freely rejected the grace that God offers to all.”

A Christian universalist, of course, might insist that the Augustinians and the Arminians are both right in their respective criticisms of each other.

We have seen so far that the Augustinians in effect reason as follows: God’s saving grace is irresistible in the end, and yet everlasting torment in hell will nonetheless be the terrible fate for some; therefore, God does not love all created persons equally and his (electing) love is thus limited in its scope. Augustine’s own interpretation of 1 Timothy 2:4 provides a nice illustration. He wrote: “the word concerning God, ‘who will have all men to be saved,’ does not mean that there is no one whose salvation he [God] doth not will … but by ‘all men’ we are to understand the whole of mankind, in every single group into which it can be divided … For from which of these groups doth not God will that some men from every nation should be saved through his only-begotten Son our Lord?” ( Enchiridion , 103—italics added).

So it is not God’s will, Augustine claimed, to save every individual from every group and every nation; it is merely God’s will to save all kinds of people, that is, some individuals from every group and every nation. Augustine’s exegetical arguments for such an interpretation, however fantastic they may appear to non-Augustinians, need not concern us here. More important for our purposes is his pattern of argument, as illustrated in the following comment: “We could interpret it [1 Tim. 2:4] in any other fashion, as long as we are not compelled to believe that the Omnipotent hath willed something to be done which was not done”—and as long as we are not compelled to believe, he no doubt took for granted, that no one will be eternally damned. For if propositions (2) and (3) are both true, then proposition (1) is false and the scope of God’s love is restricted to a limited elect. It is as simple as that.

Nor should one suppose that this Augustinian understanding of limited election is totally bereft of contemporary defenders. One such contemporary defender, the Christian philosopher Paul Helm, has argued that God’s loving nature no more necessitates that God extend a redemptive love equally to all humans than it necessitates that God create them all with the same human characteristics. For why is it, Helm asks, “that some are strong, some weak, some male, some female, some healthy, some diseased, and so forth?” He then makes the following claim: “if it is possible for there to be differentiations in the created universe that are consistent with the attributes of God then it is presumably possible for there to be differentiations with regard to God’s redemptive purposes which are entirely consistent with the divine attributes” (Helm 1985, 53). How one evaluates such a claim will no doubt depend, at least in part, upon how one answers such questions as these: Would God’s willing that one person have black hair and another brown hair be compatible with loving both of them equally and with acting justly toward both of them? Would God’s willing that one person should come to a glorious end and another to a horrific end be compatible with loving both of them equally and with acting justly toward both of them?

In response to similar questions, Jeff Jordan has challenged the whole idea, which he acknowledges to be widely accepted among theistic philosophers, that “God’s love must be maximally extended and equally intense” (Jordan 2012, 53). According to Jordan, such maximally extended love would be a deficiency in any human who manifested it; hence, it should not be numbered among God’s perfections or great-making properties. Neither is it possible, he appears to argue, that God should love equally each and every created person. For “if God has deep attachments [with some of them], it follows that he does not love all [of them] equally. And being a perfect being, God would have loves of the deepest kind” (Jordan 2012, 67). Jordan thus asks in a later article, “What if ... it is not possible in-principle [even for God] to love every person uniformly to the same degree?” And in support of his contention that this is indeed impossible, Jordan argues, first, that people in fact have incompatible interests, second, that two “interests are incompatible just in case attempts to bring about one of them require that the other be impeded,” and third, that love of the deepest kind “has as a necessary constituent identifying with the interests of one’s beloved” (Jordan 2015, 184).

Two critical problems arise at this point. First, why suppose that the deepest love for others (in the sense of willing the very best for them) always requires identifying with their own interests? According to Jordan, a person’s interest is merely “a desire or goal had by that person—something that a person cares about” (Jordan 2012, 62, n. 26; see also Jordan 2020, 83). But in that sense of “interest,” God’s deepest love for a person surely requires that God actually oppose or impede some of that person’s interests. Why else would Christians believe, as the author of Hebrews put it, that God often “disciplines those whom he loves and chastises every child whom he accepts”? (Heb. 12:6). And second, why suppose that God cannot identify with incompatible interests anyway? Indeed, why cannot a single individual identify with incompatible interests (or conflicting desires) of his or her own? Jordan himself offers the following explanation of what it means to identify with an interest: “Identifying with an interest we might understand as, roughly, caring about what one’s beloved cares about because one’s beloved cares about it” (Jordan 2015, 184). But why, then, cannot a loving mother, for example, care deeply about the incompatible interests (or immediate desires) of her two small children as they squabble over a toy and care about these incompatible interests, however trivial they might otherwise have seemed to her, precisely because her beloved children care about them? The impossibility of her satisfying such incompatible interests hardly entails the impossibility of her identifying with them in the sense of caring deeply about them. [ 2 ] Accordingly, what a proponent of limited election needs at this point is to specify a clear sense of “to identify with” such that (a) it is impossible for God to identify with incompatible interests and (b) an equally deep love for all created persons would nonetheless require that God be able to identify with at least some of their incompatible interests.

In any case, the vast majority of Christian philosophers who have addressed the topic of hell in recent decades and have published at least some of their work in the standard philosophical journals do accept proposition (1) and also reject, therefore, any hint of Augustinian limited election. However ephemeral and changeable such a consensus may be, the contemporary consensus does seem to be that God’s redemptive love extends to all humans equally (see, for example, Buckareff and Plug 2005, Knight 1997, Kronen and Reitan 2011, Kvanvig 1993, Murray 1998, Seymour 2000b, Stump 1983, Swinburne 1983, and Walls 1998). For a more thorough examination and critique of Jordan’s specific arguments, see Parker 2013, and Talbott 2020; and for Jordan’s reply to some of this criticism, see Jordan 2015 and Jordan 2020, Ch. 5.

2. The Augustinian Understanding of Hell

Behind the Augustinian understanding of hell lies a commitment to a retributive theory of punishment, according to which the primary purpose of punishment is to satisfy the demands of justice or, as some might say, to balance the scales of justice. And the Augustinian commitment to such a theory is hardly surprising. For based upon his interpretation of various New Testament texts, Augustine insisted that hell is a literal lake of fire in which the damned will experience the horror of everlasting torment; they will experience, that is, the unbearable physical pain of literally being burned forever. The primary purpose of such unending torment, according to Augustine, is not correction, or deterrence, or even the protection of the innocent; nor did he make any claim for it except that it is fully deserved and therefore just. As for how such torment could be even physically possible, Augustine insisted further that “by a miracle of their most omnipotent Creator, they [living creatures who are damned] can burn without being consumed, and suffer without dying” ( City of God , Bk. 21, Ch. 9). Such is the metaphysics of hell, as Augustine understood it.

It would be unfair, however, to imply that all Augustinians, as classified above, accept Augustine’s own understanding of an eternal torture chamber. For many Augustinians view the agony of hell as essentially psychological and spiritual in nature, consisting of the knowledge that every possibility for joy and happiness has been lost forever. Hell, as they see it, is thus a condition in which self-loathing, hatred of others, hopelessness, and infinite despair consumes the soul like a metaphorical fire. Still, virtually all Augustinians agree with Jonathan Edwards concerning this: whatever the precise nature of the suffering, “In hell God manifests his being and perfections only in hatred and wrath, and hatred without love” (Edwards 1738, 390). In fact, according to Edwards, the damned never were an object of God’s electing love in the first place: “The saints in glory will know concerning the damned in hell, that God never loved them, but that he hates them, and [that they] will be for ever hated of God” (Edwards 1834, sec. III). So why are Christians required to love even those whom God has always hated? Because, says Edwards, we have no way of knowing in this life who is, and who is not, an object of God’s eternal hatred. “We ought now to love all, and even wicked men” because “we know not but that God loves them” (sec. III). In the next life, however, “the heavenly inhabitants will know that [the damned] … are the objects of God’s eternal hatred” (sec. II). Edwards and other Augustinians thus hold that the damned differ from the saved in one respect only: even before the damned were born, God had already freely chosen to exclude them from the grace and the redemptive love that God lavishes upon on the elect.

So why, one may wonder at this point, do the Augustinians believe that anyone—whether it be Judas Iscariot, Saul of Tarsus, or Adolph Hitler—actually deserves unending torment as a just recompense for their sins? The typical Augustinian answer appeals to the seriousness or the heinous character of even the most minor offense against God. In Cur Deus Homo (or Why God Became Man ), a classic statement of the substitution theory of atonement, St. Anselm illustrated such an appeal with the following example. Suppose that God were to forbid you to look in a certain direction, even though it seemed to you that by doing so you could preserve the entire creation from destruction. If you were to disobey God and to look in that forbidden direction, you would sin so gravely, Anselm declared, that you could never do anything to pay for that sin adequately. As a proponent of the retributive theory, Anselm first insisted that “God demands satisfaction in proportion to the extent of the sin.” He then went on to insist that “you do not make satisfaction [for any sin] unless you pay something greater than is that for whose sake [namely God’s] you ought not to have sinned” ( Cur Deus Homo I, Ch. 21). Anselm’s argument, then, appears to run as follows: Because God is infinitely great, the slightest offense against God is also infinitely serious; and if an offense is infinitely serious, then no suffering the sinner might endure over a finite period of time could possibly pay for it. So either the sinner does not pay for the sin at all, or the sinner must pay for it by enduring everlasting suffering (or at least a permanent loss of happiness).

But what about those who never commit any offense against God at all, such as those who die in infancy or those who, because of severe brain damage or some other factor, never develop into minimally rational agents? These too, according to Augustine, deserve to be condemned along with the human race as a whole. “For … the whole human race,” he insisted, “was condemned in its apostate head by a divine judgment so just that even if not a single member of the race [including, therefore, those who die in infancy] were ever saved from it, no one could rail against God’s justice” ( Enchiridion , 99). [ 3 ] Registering his agreement with Augustine, Calvin likewise wrote: “Hence, as Augustine says, whether a man is a guilty unbeliever or an innocent believer, he begets not innocent but guilty children, for he begets them from a corrupted nature” (Calvin 1536, Bk. II, Ch. I, sec. 7 —italics added). Augustine and Calvin both believed, then, that God justly condemns some who die in infancy; indeed, if their innocence required that God unite with them, then the ground of their salvation would lie in themselves rather than, as Augustine saw it, in God’s own free decision to save them from their inherited guilt. [ 4 ] With respect to the unborn twins Jacob and Esau, Augustine thus wrote: “both the twins were ‘by nature children of wrath,’ not because of any works of their own, but because they were both bound in the fetters of damnation originally forged by Adam” ( Enchiridion , 98).

As these remarks illustrate, the Augustinian understanding of original sin implies that we are all born guilty of a heinous sin against God, and this inherited guilt relieves God of any responsibility for our spiritual welfare. In Augustine’s own words, “Now it is clear that the one sin originally inherited, even if it were the only one involved , makes men liable to condemnation” ( Enchiridion , 50—italics added). Augustine thus concluded that God can freely decide whom to save and whom to damn without committing any injustice at all. “Now, who but a fool,” he declared, “would think God unfair either when he imposes penal judgment on the deserving or when he shows mercy to the undeserving” (Enchiridion, 98). For the Augustinians, then, the bottom line is that, even as our Creator, God owes us nothing in our present condition because, thanks to original sin, we come into this earthly life already deserving nothing but everlasting punishment in hell as a just recompense for original sin.

Although this Augustinian rationale for the justice of hell has had a profound influence on the Western theological tradition, particularly in the past, critics of Augustinian theology, both ancient and contemporary, have raised a number of powerful objections to it.

One set of objections arises from within the retributive theory itself, and here are three such objections that critics have raised. First, why should the greatness of the one against whom an offense occurs determine the degree of one’s personal guilt anyway? According to most proponents of the retributive theory, the personal guilt of those who act wrongly must depend, at least in part, upon certain facts about them . A schizophrenic young man who tragically kills his loving mother, believing her to be a sinister space alien who has devoured his real mother, may need treatment, they would say, but a just punishment seems out of the question. Similarly, the personal guilt of those who disobey God or violate the divine commands must likewise depend upon the answer to such questions as these: Have they knowingly violated a divine command?—and if so, to what extent are they responsible for their own rebellious impulses? To what extent do they possess not only an implicit knowledge of God and the divine commands, but a clear vision of the nature of God? To what extent do they see clearly the choice of roads, the consequences of their actions, or the true nature of evil? Even many Augustinians admit the relevance of such questions when they insist that Adam’s sin was especially heinous because he supposedly had special advantages, such as great happiness and the beatific vision, that his descendants do not enjoy. If Adam’s sin was especially heinous because he had special advantages, then the sins of those who lack his special advantages must be less heinous; and if that is true, if some sins against God are less heinous than others, then the greatness of God cannot be the only, or even the decisive, factor in determining the degree of one’s personal guilt or the seriousness of a given sin (see Adams 1975, 442 and Kvanvig 1993, 40–50).

Second, virtually all retributivists, with the notable exception of the Augustinian theologians, reject as absurd the whole idea of inherited guilt. So why, one may ask, do so many Augustinians, despite their commitment to a retributive theory of punishment, insist that God could justly condemn even infants on account of their supposedly inherited guilt? Part of the explanation, according to Philip Quinn, may lie “in a homuncular view of human nature itself” (Quinn 1988, 99) or in what some philosophers might label as a simple category mistake. A good illustration of the homuncular view, as Quinn calls it, might be the following chapter heading in Anselm’s Cur Deus Homo : “What it was that man, when he sinned, removed from God and cannot repay” (I, Ch. 23). The implication of such language, which we also find in Augustine, Calvin, and a host of others, is that humankind or human nature or the human race as a whole is itself a person (or homunculus) who can act and sin against God. Perhaps that explains how Augustine could write: “Man … produced depraved and condemned children. For we were all in that one man, since we were all that one man who fell into sin” ( City of God , Bk. XIII, Ch. 14). And perhaps it also explains how Calvin could write: “even infants themselves, while they carry their condemnation with them from the mother’s womb, are guilty not of another’s fault but of their own” fault (Calvin 1536, Bk. II, Ch. I, sec. 8). The reasoning here appears to run as follows: Humankind is guilty of a grievous offense against God; infants are instances of humankind; therefore, infants are likewise guilty of a grievous offense against God. But most retributivists would reject this way of speaking as simply incoherent. Whether one agrees with it or not, one can at least understand the claim that Adam’s sin had disastrous consequences for all his progeny in that they inherited many defects, deficiencies, and degenerate dispositions. One can also understand Calvin’s claim that, as a result of original sin, “our own insight … is utterly blind and stupid in divine matters” and that “man’s keenness of mind is mere blindness as far as the knowledge of God is concerned” (Calvin 1536, Bk. II, Ch. II, sec. 19). One can even understand the claim that we are morally responsible for doing something about our inherited defects, provided that we have the power and the opportunity to do so. But the claim that we are born guilty is another matter, as is the claim that we are all deserving of everlasting punishment on account of having inherited certain defects or deficiencies. Most retributivists would regard such inherited defects as excusing conditions that decrease , rather than increase , the degree of one’s personal guilt. So even though the Augustinians accept the idea of divine retribution, they appear at the same time to reject important parts of the retributive theory of punishment.

Third, if, as Anselm insisted, even the slightest offense against God is infinitely serious and thus deserves a permanent loss of happiness as a just recompense, then the idea, so essential to the retributive theory, that we can grade offenses and fit lesser punishments to lesser crimes appears to be in danger of collapsing. Many Christians do, it is true, speculate that gradations of punishment exist in hell; some sinners, they suggest, may experience greater pain than others, and some places in hell may be hotter than others. Augustine even tried to ameliorate his views concerning the fate of unbaptized infants by suggesting that “such infants as quit the body without being baptized will be involved in the mildest condemnation of all” ( On Merit and the Forgiveness of Sins, and the Baptism of Infants , Bk. I, Ch. 21 [ available online ]). But many retributivists would nonetheless respond as follows. If all of those in hell, including the condemned infants, are dead in the theological sense of being separated from God forever, and if this implies a permanent loss of both the beatific vision and every other conceivable source of worthwhile happiness, then they have all received a punishment so severe that the further grading of offenses seems pointless. We would hardly regard a king who executes every law-breaker, the jaywalker no less than the murderer, as just; nor would we feel much better if, in an effort to fit the punishment to the crime, the king should reserve the more “humane” forms of execution for the jaywalker. Once you make a permanent and irreversible loss of happiness the supposedly just penalty for the most minor offense, the only option left for more serious offenses is to pile on additional suffering. But at some point piling on additional suffering for more serious offenses seems utterly demonic, or at least so many retributivists would insist; and it does nothing to ameliorate a permanent loss of happiness for a minor offense or, as in the case of non-elect babies who die in infancy, for no real offense at all.

All of which brings one to what Marilyn McCord Adams and many others see as the most crucial question of all. How could any sin that a finite being commits in a context of ambiguity, ignorance, and illusion deserve an infinite penalty as a just recompense? (See Adams 1993, 313).

Another set of objections to the Augustinian understanding of hell arises from the perspective of those who reject a retributive theory of punishment. According to Anselm and the Augustinians generally, no punishment that a sinner might endure over a finite period of time can justly compensate for the slightest offense against God. Anselm thus speculated that if no suffering of finite duration will fully satisfy the demands of justice, perhaps suffering of infinite duration will do the trick. But the truth, according to many critics, is that no suffering and no punishment of any duration could in and of itself compensate for someone’s wrongdoing. In the right circumstances punishment might be a means to something that satisfies the demands of justice, but it has no power to do so in and of itself. The Victorian visionary George MacDonald thus put it this way: “Punishment, or deserved suffering, is no equipoise to sin. It is no use laying it on the other scale. It will not move it a hair’s breadth. Suffering weighs nothing at all against sin” (MacDonald 1889, 510). Why not? Because punishment, whether it consists of additional suffering or a painless annihilation, does nothing in and of itself, MacDonald insisted, to cancel out a sin, to compensate or to make up for it, to repair the harm that it brings into our lives, or to heal the estrangement that makes it possible in the first place. [ 5 ] Neither does it justify God’s decision to permit the wrongdoing in the first place.

So what, theoretically, would make things right or fully satisfy justice in the event that someone should commit murder or otherwise act wrongly? Whereas the Augustinians insist that justice requires punishment, other religious writers insist that justice requires something very different, namely reconciliation and restoration (see, for example, Marshall, 2001). Only God, however, has the power to achieve true restoration in the case of murder, because divine omnipotence can resurrect the victims of murder just as easily as it can the victims of old age. According to George MacDonald, whose religious vision was almost the polar opposite of the Augustinian vision, perfect justice therefore requires, first, that sinners repent of their sin and turn away from everything that would separate them from God and from others; it requires, second, that God forgive repentant sinners and that they forgive each other; and it requires, third, that God overcome, perhaps with their own cooperation, any harm that sinners do either to others or to themselves. Augustinians typically object to the idea that divine justice, no less than divine love, requires that God forgive sinners and undertake the divine toil of restoring a just order. But MacDonald insisted that, even as human parents have an obligation to care for their children, so God has a freely accepted responsibility, as our Creator, to meet our moral and spiritual needs. God therefore owes us forgiveness for the same reason that human parents owe it to their children to forgive them in the event that they misbehave. Of course, precisely because they do forgive their children, loving parents may sometimes punish their children and even hold the feet of a child to the proverbial fire when this seems necessary for the child’s own welfare. And if the time should come when loving parents are required to respect the misguided choices of a rebellious teenager or an adult child, they will always stand ready to restore fellowship with a prodigal son or daughter in the event of a ruptured relationship.

We thus encounter two radically different religious visions of divine justice, both of which deserve a full and careful examination. According to the Augustinian vision, those condemned to hell are recipients of divine justice but are not recipients of divine mercy; hence justice and mercy are, according to this vision, radically different (perhaps even inconsistent) attributes of God. [ 6 ] But according to an alternative religious vision, as exemplified in the work of George MacDonald 1889 and J.A.T. Robinson 1968, God’s justice and mercy are the very same attribute in this sense: divine justice is altogether merciful even as divine mercy is altogether just.

3. Free-will Theodicies of Hell

Unlike the Augustinians, Arminian theologians emphasize the role that free will plays in determining one’s eternal destiny in heaven or hell; they also accept the so-called libertarian understanding of free will, according to which freedom and determinism are incompatible (see the entry on free will) ). Because not even an omnipotent being can causally determine a genuinely free choice, the reality of free will, they say, introduces into the universe an element that, from God’s perspective, is utterly random in that it lies outside of God’s direct causal control. Accordingly, if some person should freely act wrongly—or worse yet, freely reject God’s grace—in a given set of circumstances, then it was not within God’s power to induce this person to have freely acted otherwise, at least not in the exact same circumstances in which the person was left free to act wrongly. So in that sense, our human free choices, particularly the bad ones, are genuine obstacles that God must work around in order to bring a set of loving purposes to fruition. And this may suggest the further possibility that, with respect to some free persons, God cannot both preserve their their libertarian freedom in the matter and prevent them from freely continuing to reject God forever. As C. S. Lewis, an early 20th Century proponent of such a theodicy, once put it, “In creating beings with free will, omnipotence from the outset submits to the possibility of … defeat. … I willingly believe that the damned are, in one sense, successful, rebels to the end; that the doors of hell are locked on the inside” (Lewis 1944, 115).

The basic idea here is that hell, along with the self imposed misery it entails, is essentially a freely embraced condition rather than a forcibly imposed punishment ; [ 7 ] and because freedom and determinism are incompatible, the creation of free moral agents carries an inherent risk of ultimate tragedy. Whether essential to our personhood or not, free will is a precious gift, an expression of God’s love for us; and because the very love that seeks our salvation also respects our freedom, God will not prevent us from separating ourselves from him, even forever, if that is what we freely choose to do. So even though the perfectly loving God would never reject anyone, sinners can reject God and thus freely separate themselves from the divine nature; they not only have the power as free agents to reject God for a season, during the time when they are mired in ambiguity and subject to illusion, but they are also able to cling forever to the illusions that make such rejection possible in the first place.

But why suppose it even possible that a free creature should freely reject forever the redemptive will of a perfectly loving and infinitely resourceful God? In the relevant literature over the past several decades, advocates of a free-will theodicy of hell have offered at least three quite different answers to this question:

- Perhaps the most commonly expressed answer concerns the possibility of an irrevocable decision to reject God forever. Jerry Walls thus describes the damned as those who have made a decisive choice of evil (see Walls 1992, Ch. 5), Richard Swinburne suggests that “once our will is fixed for bad, we shall never [again] desire or seek what we have missed” because we have made an “irrevocable choice of character” (Swinburne 1989, 199), and R. Zachary Manis interprets Kierkegaard, whose view he defends, as suggesting that the “damned are so filled with hatred … so motivated by malice and spite … that they will to remain in their state of torment, all for the sake of demonstrating that they are in the right, and that God is in the wrong” (Manis 2016, 290).

- Another proposed answer rejects altogether the traditional idea that those in hell are lost without any further hope of restoration. Buckareff and Plug (2005) have thus argued from the very nature of the divine perfections (including perfect love) that God will always have “an open-door policy towards those in hell—making it [always] possible for those in hell to escape” (39); and similarly, Raymond VanArragon has argued that those in hell continue to reject God freely only if they retain the power to act otherwise and hence also the power to repent and be saved (see VanArragon 2010). Because the damned never lose forever their libertarian freedom in relation to God’s offer of salvation, in other words, and never lose forever the psychological possibility of genuine repentance, there is no irreversible finality in the so-called final judgment. [ 8 ] Still, the possibility remains, according to this view, that some will never avail themselves of the opportunity to escape from hell.

- A third proposed answer rests upon a Molinist perspective, according to which God’s omniscience includes what philosophers now call middle knowledge, which in turn includes far more than a simple foreknowledge of a person’s future free actions. It also includes a perfect knowledge uf what a person would have done freely in circumstances that will never even obtain. So with respect to the decision whether or not to create a given person and to place that person in a given set of circumstances, God can base this decision in part on a knowledge of what the person would do freely if created and placed in these precise circumstances—or if, for that matter, the person were placed in any other possible set of circumstances as well. From this Molinist perspective, William Lane Craig has defended the possibility that some free persons are utterly irredeemable in this sense: short of overriding their libertarian freedom, nothing God might do for them—whether it be to impart a special revelation. to administer an appropriate punishment, or to help them in some other way—will ever win them over or persuade them to repent as a means of becoming reconciled to God (Craig 1989). Craig himself calls this dreadful property of being irredeemable transworld damnation (184).

In part because it rests upon the idea of middle knowledge, which is itself controversial, Craig’s idea of transworld damnation may be the most controversial idea that any proponent of a free will theodicy of hell has put forward. It also raises the question of why a morally perfect God would create someone (or instantiate the individual essence of someone) whom God already knew in advance would be irredeemable. By way of an answer, Craig insists on the possibility that some persons would submit to God freely only in a world in which others should damn themselves forever; it is even possible, he insists, that God must permit a large number of people to damn themselves in order to fill heaven with a larger number of redeemed. Craig himself has put it this way:

It is possible that the terrible price of filling heaven is also filling hell and that in any other possible world which was feasible for God the balance between saved and lost was worse. It is possible that had God actualized a world in which there are less persons in hell, there would also have been less persons in heaven. It is possible that in order to achieve this much blessedness, God was forced to accept this much loss (1989, 183).

As this passage illustrates, Craig accepts at least the possibility that, because of free will, history includes an element of irreducible tragedy; he even accepts the possibility that if fewer people were damned to hell, then fewer people would have been saved as well. So perhaps God knows from the outset that a complete triumph over evil is unfeasible no matter what divine actions might be taken; as a result, God merely tries to minimize the defeat, to cut the losses, and in the process to fill heaven with more saints than otherwise would have been feasible. (For a critique of this reply, see Talbott 1992; for Craig’s rejoinder, see Craig 1993; and for a critique of Craig’s rejoinder, see Seymour 2000a.)

In any case, how one assesses each of the three answers above will depend upon how one understands the idea of moral freedom and the role it plays, if any, in someone landing in either heaven or hell. The first two answers also represent a fundamental disagreement concerning the existence of free will in hell and perhaps even the nature of free will itself. According to the first answer, the inhabitants of hell are those who have freely acquired a consistently evil will and an irreversibly bad moral character. So for the rest of eternity, these inhabitants of hell do not even continue rejecting God freely in any sense that requires the psychological possibility of choosing otherwise. But is such an irreversibly bad moral character even coherent or metaphysically possible? Not according to the second answer, which implies that a morally perfect God would never cease providing those in hell with opportunities for repentance and providing these opportunities in contexts where such repentance remains a genuine psychological possibility. All of which points once again to the need for a clearer understanding of the nature and purpose of moral freedom. (See section 5.1 below for some additional issues that arise in connection with freedom in heaven and hell.)

Given the New Testament imagery associated with Gehenna, the Lake of Fire, and the outer darkness—where there is “weeping and gnashing of teeth”—the question is not how someone in a context of ambiguity, ignorance, and misperception could freely choose separation from the divine nature over union with it; the question is instead how someone could both experience such separation (or the unbearable misery of hell, for example) and freely choose to remain in such a state forever. This is not a problem for the Augustinians because, according to them, the damned have no further choice in the matter once their everlasting punishment commences. But it is a problem for those free-will theists who believe that the damned freely embrace an eternal destiny apart from God, and the latter view requires, at the very least, a plausible account of the relevant freedom.

Now, as already indicated, those who embrace a free-will theodicy of hell typically appeal, in the words of Jonathan Kvanvig, to “a libertarian account of human freedom in order to provide a complete response to” the problem of hell (Kvanvig 2011, 54). But of course such a “complete response” would also require a relatively complete account of libertarian freedom. According to Kvanvig, “some formulation of the Principle of Alternative Possibilities (PAP) correctly describes this notion of [libertarian] freedom”; and, as he also points out, this “principle claims that in order to act freely one must be able to do otherwise” (48). But at most PAP merely sets forth a necessary condition of someone acting freely in the libertarian sense, and it includes no requirement that a free choice be even minimally rational. So consider again the example, introduced in section 2.1 above, of a schizophrenic young man who kills his loving mother, believing her to be a sinister space alien who has devoured his real mother; and this time suppose further that he does so in a context in which PAP obtains and he categorically could have chosen otherwise (perhaps because he worries about possible retaliation from other sinister space aliens). Why suppose that such an irrational choice and action, even if not causally determined, would qualify as an instance of acting freely? Either our seriously deluded beliefs, particularly those with destructive consequences in our own lives, are in principle correctable by some degree of powerful evidence against them, or the choices that rest upon them are simply too irrational to qualify as free moral choices.

If that is true, then not just any causally undetermined choice, or just any agent caused choice, or just any randomly generated selection between alternatives will qualify as a free choice for which the choosing agent is morally responsible. Moral freedom also requires a minimal degree of rationality on the part of the choosing agent, including an ability to learn from experience, an ability to discern normal reasons for acting, and a capacity for moral improvement. With good reason, therefore, do we exclude lower animals, small children, the severely brain damaged, and perhaps even paranoid schizophrenics from the class of free moral agents. For, however causally undetermined some of their behaviors might be, they all lack some part of the rationality required to qualify as free moral agents. [ 9 ]

Now consider again the view of C. S. Lewis and many other Christians concerning the bliss that union with the divine nature entails, so they believe. and the objective horror that separation from it entails, and suppose that the outer darkness—that is, a soul suspended alone in nothingness, without even a physical order to experience and without any human relationships at all—should be the logical limit (short of annihilation) of possible separation from the divine nature. These ideas seem to lead naturally to a dilemma argument for the conclusion that a freely chosen eternal destiny apart from God is metaphysically impossible. For either a person S is fully informed about who God is and what both union with the divine nature and separation from it would entail, or S is not so informed. If S is fully informed and should choose a life apart from God anyway, then S’s choice would be utterly and almost inconceivably irrational; such a choice would fall well below the threshold required for moral freedom. And if S is not fully informed, then God can of course continue to work with S, subjecting S to new experiences, shattering S’s illusions, and correcting S’s misjudgments in perfectly natural ways that do not interfere with S’s freedom. Beyond that, for as long as S remains less than fully informed, S is simply in no position to reject the true God; S may reject a caricature of God, perhaps even a caricature of S’s own devising, but S is in no position to reject the true God. Therefore, in either case, whether S is fully informed or less than fully informed, it is simply not possible that S should reject the true God freely .

By way of a reply to this argument and in defense of his own free–will approach to hell—which, by the way, in no way excludes the possibility that some inhabitants of hell may eventually escape from it—Jerry Walls concedes that “the choice of evil is impossible for anyone who has a fully formed awareness that God is the source of happiness and sin the cause of misery” (Walls 1992, 133). But Walls also contends that, even if those in hell have rejected a caricature of God rather than the true God, it remains possible that some of them will finally make a decisive choice of evil and will thus remain in hell forever. He then makes a three-fold claim: first, that the damned have in some sense deluded themselves, second, that they have the power to cling to their delusions forever, and third, that God cannot forcibly remove their self-imposed deceptions without interfering with their freedom in relation to God (Walls 1992, Ch. 5).

For more detailed discussions of these and related issues, see Swinburne 1989 (Ch. 12), Craig 1989 and 1993, Talbott 2007, Walls 1992 (Ch. 5), 2004a, and 2004b, Kronen and Reitan 2011 (142–146), and Manis 2016 and 2019. See also sections 4.2 and 5.1 below.

Consider now the two conditions under which we humans typically feel justified in interfering with the freedom of others (see Talbott 1990a, 38). We feel justified, on the one hand, in preventing one person from doing irreparable harm—or more accurately, harm that no human being can repair—to another; a loving father may thus report his own son to the police in an effort to prevent the son from committing murder. We also feel justified, on the other hand, in preventing our loved ones from doing irreparable harm to themselves; a loving father may thus physically overpower his daughter in an effort to prevent her from committing suicide.

Now one might, it is true, draw a number of faulty inferences from such examples as these, in part because we humans tend to think of irreparable harm within the context of a very limited timeframe, a person’s life on earth. Harm that no human being can repair may nonetheless be harm that God can repair. It does not follow, therefore, that a loving and omnipotent God, whose goal is the reconciliation of the world, would prevent every suicide and every murder; it follows only that such a God would prevent every harm that not even omnipotence could repair at some future time, and neither suicide nor murder is necessarily an instance of that kind of harm. So even though a loving God might sometimes permit murder, such a God would never permit one person to annihilate the soul of another or to destroy the very possibility of future happiness in another; and even though a loving God might sometimes permit suicide, such a God would never permit genuine loved ones to destroy the very possibility of future happiness in themselves either. The latter conclusion concerning suicide is no doubt the more controversial, and Jonathan Kvanvig in particular has challenged it (see Kvanvig 1993, 83–88). But whatever the resolution of this particular debate, perhaps both parties can agree that God, as Creator, would deal with a much larger picture and a much longer timeframe than that with which we humans are immediately concerned.

So the idea of irreparable harm—that is, of harm that not even omnipotence could ever repair—is critical at this point. It is most relevant, perhaps, in cases where someone imagines sinners freely choosing annihilation (Kvanvig), or imagines them freely making a decisive and irreversible choice of evil (Walls), or imagines them freely locking the gates of hell from the inside (C. S. Lewis). But proponents of the so-called escapism understanding of hell can plausibly counter that hell is not necessarily an instance of such irreparable harm, and Raymond VanArragon in particular raises the possibility that God might permit some loved ones to continue forever rejecting God in a non-decisive way that would not, at any given time, harm them irreparably (see VanArragon 2010, 37ff; see also Kvanvig 2011, 52). Here it is perhaps worth noting how broadly VanArragon defines the term “rejecting God” (see 2010, 30–31)—so broadly, in fact, that any sin for which one is morally responsible would count as an instance of someone rejecting God. He thus explicitly states that rejecting God in his broad sense requires neither an awareness of God nor a conscious decision, however confused it may be, to embrace a life apart from God. Accordingly, persistent sinning without end would never result, given such an account, in anything like the traditional hell, whether the latter be understood as a lake of fire, the outer darkness, or any other condition that would reveal the full horror of separation from God (given the traditional Christian understanding of such separation). Neither would such a sinner ever achieve a state of full clarity. For given VanArragon’s understanding of libertarian freedom, continuing to sin forever would require a perpetual context of ambiguity, ignorance, and misperception.

4. The Universalist Rejection of Everlasting Separation

A theist of any religion who accepts the traditional idea of everlasting punishment, or even the idea of an everlasting separation from God, must either reject the idea that that all human sinners are equal objects of God’s redemptive love (see proposition (1) in section 1 above) or reject the idea that God’s redemptive love will triumph in the end and bring reconciliation to each and every object of such divine love (see proposition (2)). But a theist who accepts proposition (1), as the Arminians do, and also accepts proposition (2), as the Augustinians do, can then reason deductively that almighty God will indeed triumph in the end and successfully win over each and every human sinner. From the perspective of an interpretation of the Christian Bible, moreover, Christian universalists need only accept the exegetical arguments of the Arminian theologians in support of (1) and the exegetical arguments of the Augustinian theologians in support of (2); that alone would enable them to build an exegetical case for a universalist interpretation of the Bible as a whole.

One argument in support of proposition (1) contends that love (especially in the form of willing the very best for another) is inclusive in this sense: even where it is logically possible for a loving relationship to come to an end, two persons are bound together in love only when their purposes and interests, even the conditions of their happiness, are so logically intertwined as to be inseparable. If a mother should love her child even as she loves herself, for example, then any evil that befalls the child is likewise an evil that befalls the mother and any good that befalls the child is likewise a good that befalls the mother; hence, it is simply not possible, according to this argument, for God to will the best for the mother without also willing the best for the child as well.

For similar reasons, Kenneth Einar Himma has argued that some widespread moral intuitions, “together with Christian exclusivism and the traditional doctrine of hell, entail that it is morally wrong for anyone to have children” (Himma 2011, 198). That argument seems especially forceful in the context of Augustinian theology, which implies that, for all any set of potential parents know, any child they might produce could be one of the reprobate whom God has hated from the beginning and has destined from the beginning for eternal torment in hell. The title of Himma’s article, “Birth as a Grave Misfortune,” would seem to describe such cases perfectly. (See Bawulski 2013 for a reply to Himma and Himma 2016 for Himma’s rejoinder.)

In any event, Arminians and universalists both regard an acceptance of proposition (1) as essential to a proper understanding of divine grace. Could God truly extend grace to an elect mother, they might ask, by making the baby she loves with all her heart the object of a divine hatred and do this, as the Augustinians say was done in the case of Esau, even before the child was born or had done anything good or bad? As the Arminians and the universalists both view the matter, the Augustinians have embraced a logical impossibility: the idea that God could extend a genuine love and compassion to one person even as God withholds it from some of that person’s own loved ones. They therefore reject the doctrine of limited election on the ground that it undermines the concept of grace altogether. Where they disagree, of course, is over the issue of whether the objects of God’s love can resist his grace forever. Whereas Arminians hold that, given the reality of free will, we humans can, if we so choose, resist God’s grace forever, universalists tend to believe that, even though we can resist God’s grace for a while, perhaps even for a substantial period of time (while mired in ignorance and ambiguity), we cannot resist it forever. So the issue between these two camps, the Arminians and the universalists, finally comes down to the question of which position has the resources for a better account of human freedom and of God’s respect for it (see, for example, the exchange between Walls 2004 and Talbott 2004). Or, to put the question in a slightly different way, which position, if either, requires that God interfere with human freedom (or human autonomy) in morally inappropriate ways? As the following section should illustrate, the answer to this question may be far more complicated than some might at first imagine.

A widely held assumption among free–will theists is that no guarantee of universal reconciliation is even possible apart from God’s willingness to interfere with human freedom in those cases where someone persists in rejecting God and his grace. Indeed, Jonathan Kvanvig goes so far as to describe universalism as a “view, according to which God finally decides that if one has not freely chosen Heaven, there will come a time when one will be brought to Heaven against one’s will. One will experience, in this sense, coercive redemption at some point” (Kvanvig 2011, 14). But in fact, no universalist—not even a theological determinist—holds that God sometimes coerces people into heaven against their will . For although many Christian universalists believe that God provided Saul of Tarsus with certain revelatory experiences that changed his mind in the end and therefore changed his will as well, this is a far cry from claiming that he was coerced against his will. Kvanvig’s own understanding of libertarian freedom, moreover, already establishes the logical possibility that God can bring about a universal reconciliation without in any way interfering with human freedom.

But in addition to defending the bare logical possibility of such a universal reconciliation on libertarian grounds, Eric Reitan has set forth an intriguing argument, which he calls “the Argument from Infinite Opportunity,” for the conclusion that God can effectively guarantee the salvation of all sinners without ever interfering with anyone’s libertarian freedom (see Kronen and Reitan 2011, Ch. 8). The basic idea here is that a sinner could have, if necessary, infinitely many opportunities over an unending stretch of time to repent and to submit to God freely. So consider this. Although it is logically possible, given the normal philosophical view of the matter, that a fair coin would never land heads up, not even once in a trillion tosses, such an eventuality is so incredibly improbable and so close to an impossibility that no one need fear it actually happening. Similarly, in working with some sinner S (shattering S’s illusions and correcting S’s ignorance), God could presumably bring S to a point, just short of actually determining S’s choice, where S would see the choice between horror and bliss with such clarity that the probability of S repenting and submitting to God would be extremely high. Or, if you prefer, drop the probability to .5. Over an indefinitely long period of time, S would still have an indefinitely large number of opportunities to repent; and so, according to Reitan, the assumption that sinners retain their libertarian freedom together with the Christian doctrine of the preservation of the saints yields the following result. We can be just as confident that God will eventually win over all sinners (and do so without causally determining their choices), as we can be that a fair coin will land heads up at least once in a trillion tosses.