Essay on Household Chores

Students are often asked to write an essay on Household Chores in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Household Chores

Introduction to household chores.

Household chores are tasks we do to keep our homes clean and organized. These tasks include cleaning, cooking, washing clothes, and many more. Everyone in the family can help with these tasks. Doing chores is important because it teaches responsibility and helps keep our homes nice and tidy.

Types of Household Chores

There are many types of household chores. Some chores, like dusting and sweeping, are done to keep the house clean. Others, like cooking and washing dishes, are done to prepare meals. We also do chores like laundry and taking out the trash.

Benefits of Doing Chores

Doing chores has many benefits. It teaches us how to take care of our things. It also helps us learn to work as a team when we do chores with others. Plus, doing chores can make us feel good because we are helping our family.

In conclusion, household chores are important tasks that help keep our homes clean and organized. Doing these chores can teach us many valuable skills, like responsibility and teamwork. So, let’s all do our part in keeping our homes clean!

250 Words Essay on Household Chores

What are household chores.

Household chores are tasks we do to keep our homes clean and tidy. They include activities like washing dishes, cleaning the house, cooking, doing laundry, and taking care of the garden.

Importance of Household Chores

Household chores are very important. They help us keep our homes clean and safe. A clean home is healthy and comfortable to live in. Chores also teach us responsibility and discipline. When we complete our chores, we learn to take care of our things and spaces.

Sharing Chores in a Family

In a family, everyone should help with chores. This way, the work is not too much for one person. Parents can do the harder tasks, while children can help with simpler ones. For example, children can help set the table or tidy up their toys.

Learning New Skills

Doing chores can also teach us new skills. For example, cooking can teach us about different foods and how to prepare them. Laundry can teach us how to take care of our clothes so they last longer.

The Joy of Completing Chores

Even though chores can sometimes feel boring, there is joy in completing them. When we finish a task, we can feel proud of our work. We can see the results immediately, like a clean room or a cooked meal.

In conclusion, household chores are an important part of our daily lives. They keep our homes clean, teach us responsibility and new skills, and can even bring us joy.

500 Words Essay on Household Chores

Introduction.

Household chores are tasks that we do to keep our homes neat and tidy. These chores include cleaning, cooking, washing dishes, doing laundry, and many more. They are part of our daily life and play a vital role in maintaining a healthy and organized environment.

There are many types of household chores. Cleaning chores involve sweeping and mopping the floors, dusting furniture, and cleaning windows. Kitchen chores include cooking, washing dishes, and cleaning the kitchen. Laundry chores involve washing, drying, and folding clothes. Outdoor chores might include gardening, mowing the lawn, or washing the car. Each chore has its importance and helps in keeping the house clean and organized.

Benefits of Household Chores

Doing household chores has many benefits. First, it helps to keep our surroundings clean and hygienic, which is good for our health. Second, it teaches us responsibility and discipline as we need to complete these tasks regularly. Third, chores can be a great way to exercise and stay fit. For example, sweeping the floor or mowing the lawn can be a good workout. Lastly, doing chores can also help us to learn new skills like cooking or gardening, which can be useful in our life.

Sharing Household Chores

Household chores should not be the responsibility of one person. They should be shared among all family members. This not only divides the work but also helps in building teamwork and cooperation. For example, parents can cook and clean, while children can help in setting the table or washing dishes. This way, everyone contributes to the household work and it becomes less burdensome for one person.

Chores as a Learning Experience

Doing household chores can be a great learning experience, especially for children. It teaches them the importance of cleanliness and hygiene. It also instills a sense of responsibility and discipline in them. They learn to manage their time effectively as they need to balance their chores and other activities like studies and play. Moreover, they learn practical skills like cooking, cleaning, and gardening which are essential life skills.

In conclusion, household chores are an integral part of our daily life. They help in maintaining cleanliness and order in our homes. They teach us valuable lessons about responsibility and teamwork. Moreover, they provide us with an opportunity to learn new skills. So, instead of seeing them as a burden, we should embrace them as a part of our routine and contribute our bit in making our homes a better place to live in.

(Word count: 500)

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Housewife

- Essay on How Can A Person Benefit From Philosophy

- Essay on Housing

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

One Comment

Definitely, these sharing of household chores equally including washing dishes, laundry, cleaning, cooking etc.are very important so that the wife ,the lady of the house can get time for herself ( and her own parents). Women already work double if they are working professionals.If working to help husband financially or to make themselves economically independent, husband must help his wife in household chores equally including washing dishes, laundry, cleaning, cooking etc.esp.if she is helping him in working financially.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Family Education

- Social Skills

- Teen Education

- Gender Edu.

- Book Reviews

- Rights In Edu.

Why it is important to help your parents in household chores

It is common for children to want to help out their parents with household chores. However, for some children, the thought of helping out with chores may not seem appealing. Despite this, it is important for children to assist their parents in household chores for a variety of reasons. In this article, we will discuss why it is important to help your parents in household chores, and what benefits can be gained from doing so.

First and foremost, helping your parents with household chores is a way of showing your gratitude and love for them. Your parents have likely spent years caring for you and providing for your needs. By helping them with household chores, you are taking some of the burden off of them and making their lives a little easier. This can be a small but meaningful way to repay them for all that they have done for you.

In addition, helping with household chores can also help to build a stronger relationship between parents and children. When children assist their parents with chores, it creates opportunities for them to interact and communicate with each other. This can lead to increased understanding and closeness between family members. Children who help with household chores are also able to gain a greater appreciation for the work that goes into maintaining a household and running a family.

Furthermore, helping with household chores can also help to build important life skills in children. Children who are taught how to perform household chores are given the opportunity to develop important skills such as responsibility, organization, and time management. These skills can be valuable in many areas of life, and can help children to be more successful in their personal and professional lives.

It is also worth noting that helping with household chores can also benefit children’s physical health. Doing chores can be a form of physical activity, and can help children to stay active and healthy. Additionally, chores can help to build strength and coordination, which can be beneficial for children as they grow and develop.

Another important aspect to consider is that helping with household chores can also help children to develop a sense of pride and self-esteem. When children are able to contribute to the household and complete tasks successfully, they feel a sense of accomplishment and pride in their abilities. This can help to boost their self-esteem and confidence, which can be valuable for children as they navigate their teenage years and beyond.

Helping your parents with household chores is important for a variety of reasons. It can help to show gratitude and love for your parents, build stronger relationships between family members, develop important life skills, benefit physical health, and improve self-esteem and confidence. Encouraging children to help with household chores can be a valuable way to help them grow and develop into successful, responsible adults.

Please indicate: Thinking In Educating » Why it is important to help your parents in household chores

Related Articles

- How do you think children can help their parents in their household chores

- How can we encourage children to help around the house

- 5 Tips for Motivating Your Child to Help with Household Chores

- The Importance of Chores for Kids A Guide to Assigning Age-Appropriate Tasks

- The Benefits of Allowing Children to Thrive in Their Own Time

- Navigating Favoritism Issues in Families with Multiple Children: A Comprehensive Approach

- Raising Happy Children: Cultivating Effort, Reward, and Perspective

- The Importance of Teaching Children Household Chores

- Addressing Bullying in Mathematics Class: Empowering Children to Overcome Challenges

- Fostering Independent Learning: A Critical Analysis of Early Education Practices

- Navigating Parental Dilemmas: Balancing Generosity and Empowerment

- Nurturing Hobbies in Children: A Comprehensive Analysis for Balanced Personalities

Hi, you need to fill in your nickname and email!

- Nickname Nickname (Required)

- Email Email (Required)

- Website Website

10 Reasons Why Household Chores Are Important

Whether we like it or not, household chores are a necessary part of everyday life, ensuring that our homes continue to run efficiently, and that our living environments remain organized and clean, thereby promoting good overall health and safety. Involving children in household chores gives them opportunity to become active participant in the house. Kids begin to see themselves as important contributors to the family. Holding children accountable for their chores can increase a sense of themselves as responsible and actually make them more responsible.

Children will feel more capable for having met their obligations and completed their tasks. If you let children off the hook for chores because they have too much schoolwork or need to practice a sport, then you are saying, intentionally or not, that their academic or athletic skills are most important. And if your children fail a test or fail to block the winning shot, then they have failed at what you deem to be most important.

They do not have other pillars of competency upon which to rely. By completing household tasks, they may not always be the star student or athlete, but they will know that they can contribute to the family, begin to take care of themselves, and learn skills that they will need as an adult. Here is a list of household chores for kids:

1. Sense of Responsibility

Kids who do chores learn responsibility and gain important life skills that will serve them well throughout their lives. Kids feel competent when they do their chores. Whether they’re making their bed or they’re sweeping the floor, helping out around the house gives them a sense of accomplishment. Doing daily household chores also helps kids feel like they’re part of the team. Pitching in and helping family members is good for them and it encourages them to be good citizens.

Read here a detail blog: Routine helps kids

2. Beneficial to siblings

It is helpful for siblings of kids who have disabilities to see that everyone in the family participates in keeping the family home running, each with responsibilities that are appropriate for his or her unique skill sets and abilities.

Having responsibilities like chores provides one with a sense of both purpose and accomplishment.

4. Preparation for Employment

Learning how to carry out household chore is an important precursor to employment. Chores can serve as an opportunity to explore what your child excels at and could possibly pursue as a job down the road.

5. Make your life easier

Your kids can actually be of help to you! At first, teaching these chores may require more of your time and energy, but in many cases your child will be able to eventually do his or her chores completely independently, ultimately relieving you of certain responsibilities.

6. Chores may make your child more accountable

If your child realizes the consequences of making a mess, he or she may think twice, knowing that being more tidy in the present will help make chores easier.

7. Develop fine and gross motor skills and planning abilities

Tasks like opening a clothes pin, filling and manipulating a watering can and many more actions are like a workout for the body and brain and provide practical ways to flex those muscles!

8. Teach empathy

Helping others out and making their lives easier is a great way to teach empathy. After your daughter completes a chore, you can praise and thank her, stating, “Wow… great job! Because you helped out, now Mommy has one less job to do. I really appreciate that!”

9. Strengthen bonds with pets

There is a growing body of research about how animals can help individuals with special needs. When your child feeds and cares for his pet, it strengthens their bond and makes your pet more likely to gravitate toward your child.

10. Gain an appreciation and understanding of currency

What better way to teach your child the value of a rupee than by having him earn it. After your child finishes his chores, pay him right away and immediately take him to his favorite toy store where he can buy something he wants.

Book your session now

Recent Posts

- Effects of Psychotherapy on Parental Stress - November 21, 2023

- Couple’s Therapy: Navigating marital issues as a parent - June 9, 2023

- Talk Therapy for stuttering - May 31, 2023

Leave a Comment

(15 Comments)

I love this! This has a lot of awesome information.

Thank you! Glad you like the information.

very well done it is resanoble reasons

cool info it helps me see why chores are important.

Thanks for your kind reply.

This was really helpful for a school debate!

Very helpful article!

My daughter has to speak about a topic which is why and how we should help our parent in household chores and this helped her a lot

Thanks so much for your feedback! All the best to your daughter.

Thnks a lot! the article helped a lot in my assignment and there is very nice information, Thank you!

Thanks, glad you found it useful.

Very nice article…Thank you 🙂

Thank you! Glad you liked it.

Very good article about house chore

This is very helpful for a student like me

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Mental Health

- Multilingual

- Occupational Therapy

- Speech Delay

- Speech Therapy

- Success Stories

- News of the month for Jan 2024 January 29, 2024

- Shining a Light on the Unseen: The Importance of Syndrome Awareness January 23, 2024

- Celebrating Excellence: Pratiksha Gupta Wins SABLA NARI Award for Best Speech Language Therapist and Audiologist 2023 January 19, 2024

- Speech Beyond Lisps: Celebrating Diversity in Communication January 16, 2024

- Diet tips while vacationing with picky eaters: Guide for parents of kids with ASD January 12, 2024

Don't miss our one of its kind SPEAK EASY PROGRAM for stuttering management. Chat with us to know more! Dismiss

- Research , Social-Emotional Wellbeing

- Written by Jenna Elgin, Ph.D. & Shanna Alvarez, Ph.D.

Should Kids do Chores? How to Promote Responsibility at Home and Beyond

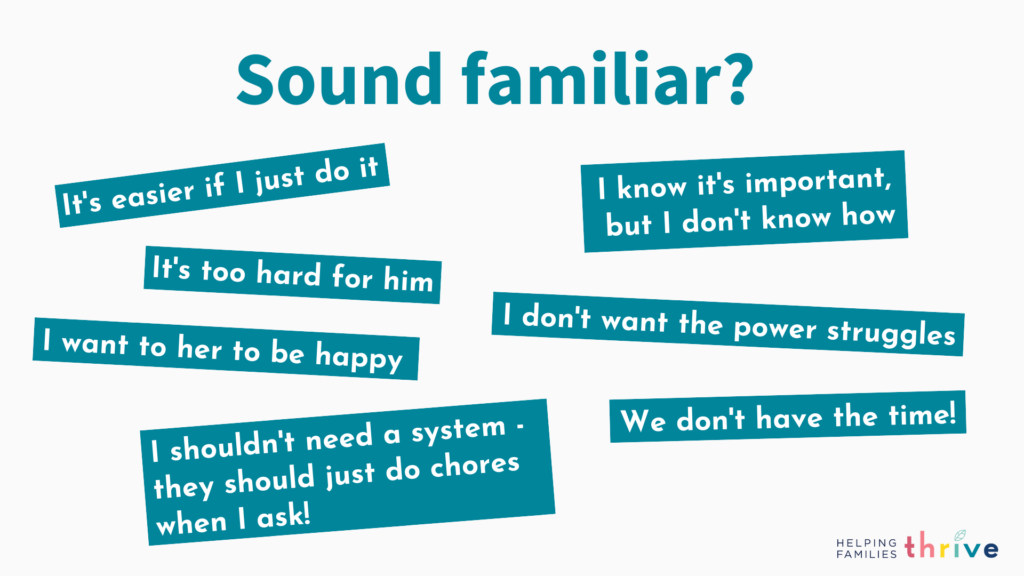

Gentle parent. Positive Parent. Free Range Parent. Conscious Parent. No matter what your parenting style or label is, most parents we work express sharing a common value: to raise resilient, capable children who contribute meaningfully to their family and community. As in most things, there is a lot of confusion how to go about achieving this goal. Should kids do chores? If so, how to actually get kids to do them?

Beware of the Parenting Pendulum

To navigate our way through the muck, it’s helpful to take a step back and understand how the swinging of the “parenting pendulum” is impacting parenting information (and misinformation) over time. In the midst of the modern “parenting wars” that dominate social media right now, parents often feel that expecting cooperation (or respect) is taboo. Sometimes it feels like any misstep in our wording or setting of a boundary may be irreversibly damaging our children!

In context, our wariness of harsh boundaries makes sense. We are recovering, evolving, and sometimes overcompensating from generations of “spare the rod spoil the child” parenting in which warmth could be hard to come by and boundaries were often more harsh than firm. Thanks to decades of research, we’ve learned that parenting styles that are high on control/boundaries but low on warmth (called the authoritarian parenting style in the research) has some significant shortcomings.

This information about what isn’t good for kids allows us as parents a wonderful opportunity for growth and evolution. However, as with many things, as we run away from the “old way” we can sometimes swing to the opposite extreme as we struggle to find a new path. In fact, as psychologists who work with families directly, our clinical work has shifted over the last few years. Previously, much of our work was helping parents find healthy replacements for spanking. However, recently we’ve had more situations where we are helping parents find a way to face their anxieties around setting firm boundaries and increasing expectations of their children.

It’s okay to have high expectations for kids

This new wave of parenting anxiety seems to result from pressure to be “purely positive” all the time. And even if parents recognize they need to set boundaries, the advice they’re seeing online about how to do so is often very rigid (i.e., if you do XYZ your child will feel abandoned or will be destined for unhealthy relationships). No wonder parents are feeling overwhelmed.

In the midst of all this mental noise, we can me calmed by remembering what we know:

Healthy parenting is a balance of warmth and boundaries.

Kids should be kids. Yes. We can go overboard with chores and expectations. Yes. But let’s not let the pendulum swing too far. No need to assign push-ups when your child’s room isn’t spotless, but also no need to wait until they feel “intrinsically motivated” to take responsibility for anything in the home.

In fact, when it comes to instilling responsibility, a recent study of 10, 000 kindergarteners found that those who participated in more household chores performed better academically, emotionally and socially by the 3rd grade. Additionally, many cultures across the world have emotionally health children (with secure attachments) who participate heartily in family teamwork in the home.

So, let’s find some balance here together. Thankfully, there is flexibility in how we do this. We use the limited research we have as a guide, mix that with what you know about your kid and give it a go. Chores are not one-size-fits-all.

3 tools to promote responsibility

1. create a culture of appreciation.

Before we can even discuss chore charts or allowance, we need to back up a bit. Our first initiative is to build a culture of appreciation in our homes. What does this mean? First, it means to shift our mindset from “how to I get my child to comply with chores” to “how can I create an environment that facilitates helpfulness, responsibility, and mutual respect.”

One way we can do this is by using process-focused praise to acknowledge a job well done (or any baby step towards that), which has been shown to build intrinsic motivation. There’s an important concept in child development research called the attention principle. It essentially means that we will get more of what we pay attention to. Unfortunately, our attention is more easily drawn to “bad” behavior than it is to positive, helpful behavior. We notice and correct our kids when they haphazardly throw their coat the ground, but don’t say anything when they hang it up.

We have to be intentional about flipping this script.

What might this sound like?

- “Thank you for hanging your coat up. It’s really helpful when you do that.”

- “Thank you for listening when I asked you to clean up. The floor looks so nice now.”

- “That’s really nice of you helping your brother get his shoes on.”

When our kids feel noticed and valued for their contributions to the home, they’re going to be more willing to participate. Moreover, when the adults in the environment thank each other for their contributions in front of their children, a powerful culture of appreciation and teamwork is being modeled.

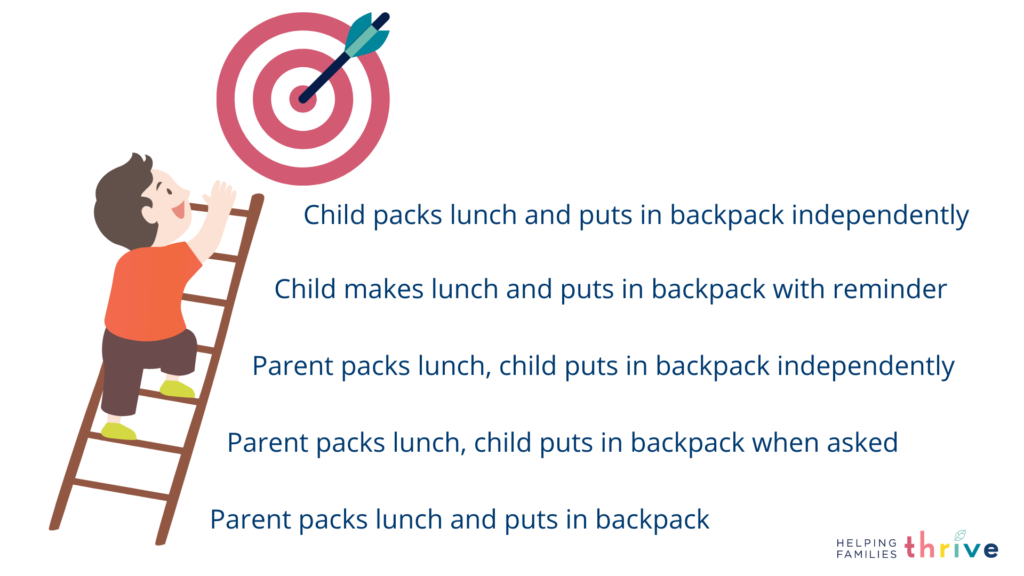

2. Avoid doing for

One of the best and easiest places to start when it comes to promoting responsibility is to assess what things you are doing for your child that they can actually begin to do for themselves. Especially when they’re little, our kids are reliant on us for so much! However, it’s easy to accidentally continue to do things for kids that they’re actually quite capable of doing themselves. Often, we continue to “help” because it’s easier and fast if we do it ourselves. But, all this “helping” can actually backfire.

Let’s take an example. For a 1-year-old who’s thirsty, it makes complete sense for the parent to grab the cup from the cupboard, fill it with water, and hand it to the child. However, this can easily turn into a parent doing this for years and years and years without even realizing their child can now learn to get their own water. Now, take a moment to review a typical day in your family. Are there moments that you’re stepping in too much? Are there things you do for you kids on autopilot that they may now be ready to learn?

Once you’ve identified some of those areas, when your child asks for help (or expresses frustration) try pausing before jumping in. What might this look like?

- If your child gets upset when building with Legos, pause and count to 10 before offering help. Often kids will work through their feelings without us intervening.

- When your child asks you do something try saying, “I’m happy to help. It looks like you are on your way to figuring it out! I’ll come back in just a minute to check on you and help out if you need it.”

3. Find the “just right” amount of support

Chores summary

We know from research that kids who participate in household chores show higher levels of self-competency and experience other benefits later on. Building a culture of appreciation, avoiding doing things for kids that they can do themselves, and finding the “just right” amount of help are simple ways parents can support this aim.

For additional tools, including a research-backed approach to chore charts and allowance , check out our recorded workshop: Raising Capable Kids .

Share this post

Pingback: RICH88 สล็อตเล่นแล้วรวย

Pingback: แผงโซล่าเซล

Pingback: เกมออนไลน์ LSM99

Pingback: Lsm99 เว็บบอล Auto

Comments are closed.

As psychologists, we were passionate about evidence-based parenting even before having kids ourselves. Once we became parents, we were overwhelmed by the amount of parenting information available, some of which isn’t backed by research. This inspired the Helping Families Thrive mission: to bring parenting science to the real world.

search the site

Learn With Us

Psychologist created, parent tested workshops and mini-courses to help families thrive.

Our comprehensive Essentials course puts the power of the most studied parenting tools in the palm of your hand.

post categories

Improve Your Child’s Emotion Regulation Skills

A free, 15-page guide filled with practical strategies.

find us elsewhere

find your way around

discover courses

important links

Our 3-Step Strategy

Download our free guide to improve your child’s cooperation.

For educational purposes only. Not intended to diagnose or treat any condition, illness or disease.

Family Work

The daily work of families—the ordinary hands-on labor of sustaining life—has the power to bind us together.

By Kathleen Slaugh Bahr and Cheri A. Loveless in the Spring 2000 Issue

Illustrations by Rich Lillash

I grew up in a little town in Northern Utah, the oldest daughter in a family of 13 children. We lived on a small two-and-a-half-acre farm with a large garden, fruit trees, and a milk cow. We children loved helping our dad plant the garden, following behind him like little quail as he cut the furrow with his hoe and we dropped in the seeds. Weeding was less exciting, but it had to be done. I was never very good at milking the cow. Fortunately, my brothers shared that task.

In the autumn, we all helped with the harvest. I especially loved picking and bottling the fruit. It required the hands of all 13 of us plus Mom and Dad. We children swarmed through the trees picking the fruit. My dad would fire up an old camp stove where we heated the water to scald the fruit. My mother supervised putting the fruit in jars, adding the sugar, putting on the lids. My youngest sister remembers feeling very important because she had hands small enough to turn the peach halves if they fell into the jars upside downand they usually did. When the harvest was complete, I loved looking at the freezer full of vegetables and all the jars of fruit. They looked like jewels to me.

Caring for our large family kept all of us busy most of the time. Mother was the overseer of the inside work, and Dad the outside, but I also remember seeing my father sweep floors, wash dishes, and cook meals when his help was needed. As children we often worked together, but not all at the same task. While we worked we talked, sang, quarreled, made good memories, and learned what it meant to be family members, good sons or daughters and fathers or mothers, good Americans, good Christians.

As a young child, I didn’t know there was anything unusual about this life. My father and mother read us stories about their parents and grandparents, and it was clear that both my father and mother had worked hard as children. Working hard was what families did, what they always had done. Their work was “family work,” the everyday, ordinary, hands-on labor of sustaining life that cannot be ignored—feeding one another, clothing one another, cleaning and beautifying ourselves and our surroundings. It included caring for the sick and tending to the tasks of daily life for those who could not do it for themselves. It was through this shared work that we showed our love and respect for each other—and work was also the way we learned to love and respect each other.

“Many social and political forces continue the devaluation of family work.”

When I went to graduate school, I learned that not everyone considered this pattern of family life ideal. At the university, much of what I read and heard belittled family work. Feminist historians reminded us students that men had long been liberated from farm and family work; now women were also to be liberated. One professor taught that assigning the tasks of nurturing children primarily to women was the root of women’s oppression. I was told that women must be liberated from these onerous family tasks so that they might be free to work for money.

Today many social and political forces continue the devaluation of family work, encouraging the belief that family work is the province of the exploited and the powerless. Chief among these forces is the idea that because money is power, one’s salary is the true indication of one’s worth. Another is that the important work of the world is visible and takes place in the public sphere—in offices, factories, and government buildings. According to this ideology, if one wants to make a difference in the world, one must do it through participation in the world of paid work.

Some have tried to convince us of the importance of family work by calling attention to its economic value, declaring, as in one recent study, that a stay-at-home mom’s work is worth more than half a million dollars. 1 But I believe assigning economic value to household work does not translate into an increase in its status or power. In fact, devaluing family work to its mere market equivalent may even have the opposite effect. People who see the value of family work only in terms of the economic value of processes that yield measurable products—washed dishes, baked bread, swept floors, clothed children—miss what some call the “invisible household production” that occurs at the same time, but which is, in fact, more important to family-building and character development than the economic products. Here lies the real power of family work—its potential to transform lives, to forge strong families, to build strong communities. It is the power to quietly, effectively urge hearts and minds toward a oneness known only in Zion.

Back to Eden

Family work actually began with Adam and Eve. As best we can discern, they lived a life of relative ease in the Garden of Eden. They “dressed” and “kept” it ( Moses 3:15 ), but it isn’t clear what that entailed since the plants were already flourishing. There were no weeds, and Adam and Eve had no children to prod or cajole into watering or harvesting, if such tasks needed to be done

When they exercised their agency and partook of the fruit, Adam and Eve left their peaceful, labor-free existence and began one of hard work. They were each given a specific area of responsibility, yet they helped each other in their labors. Adam brought forth the fruit of the earth, and Eve worked along with him ( Moses 5:1 ). Eve bore children, and Adam joined her in teaching them ( Moses 5:12 ). They were not given a choice about these two lifetime labors; these were commandments ( Moses 4:22–25 ).

Traditionally, many have considered this need to labor as a curse, but a close reading of the account suggests otherwise. God did not curse Adam; He cursed the ground to bring forth thorns and thistles ( Moses 4:24 ), which in turn forced Adam to labor. And Adam was told, “Cursed shall be the ground for thy sake ” ( vs. 23 , emphasis added). In other words, the hard work of eating one’s bread “by the sweat of thy face” ( vs. 25 ) was meant to be a blessing.

According to the New Testament, the work of bearing and rearing children was also intended as a blessing. Writes the Apostle Paul: “[Eve] shall be saved in childbearing, if they continue in faith and charity and holiness with sobriety” ( 1 Tim. 2:15 , emphasis added). Significantly, Joseph Smith corrected the verse to read, “ They shall be saved in childbearing” ( JST, 1 Tim. 2:15 , emphasis added), indicating that more than the sparing of Eve’s physical life was at issue here. Both Adam and Eve would be privileged to return to their Heavenly Father through the labor of bringing forth and nurturing their offspring.

According to scripture, then, the Lord blessed Adam and Eve (and their descendants) with two kinds of labor that would, by the nature of the work itself, help guarantee their salvation. Both of these labors—tilling the earth for food and laboring to rear children—are family work, work that sustains and nurtures members of a family from one day to the next. But there is more to consider. These labors literally could not be performed in Eden. These are the labors that ensure physical survival; thus, they became necessary only when mankind left a life-sustaining garden and entered a sphere where life was quickly overcome by death unless it was upheld by steady, continual, hard work. Undoubtedly the Lord knew that other activities associated with mortality—like study and learning or developing one’s talents—would also be important. But His initial emphasis, in the form of a commandment, was on that which had the power to bring His children back into His presence, and that was family work.

Since Eden many variations and distortions of the Lord’s original design for earthly labor have emerged. Still, the general pattern has remained dominant among many peoples of the earth, including families who lived in the United States at the turn of the last century. Mothers and fathers, teenagers and young children cared for their land, their animals, and for each other with their own hands. Their work was difficult, and it filled almost every day of their lives. But they recognized their family work as essential, and it was not without its compensations. It was social and was often carried out at a relaxed pace and in a playful spirit.

“The wrenching apart of work and home-life is one of the great themes in social history.”

Yet, long before the close of the 19th century this picture of families working together was changing. People realized that early death was often related to the harshness of their daily routine. Also, many young people longed for formal schooling or to pursue scientific careers or vocations in the arts, life courses that were sometimes prevented by the necessity of hard work. Industrialization promised to free people from the burden of domestic labor. Many families abandoned farm life and crowded into tenement housing in the cities to take jobs in factories. But factory work was irregular. Most families lived in poverty and squalor, and disease was common.

Reformers of the day sought to alleviate these miseries. In the spirit of the times, many of them envisioned a utopian world without social problems, where scientific inventions would free humans from physical labor, and modern medicine would eliminate disease and suffering. Their reforms eventually transformed work patterns throughout our culture, which in turn changed the roles of men, women, and children within the family unit.

By the turn of the century, many fathers began to earn a living away from the farm and the household. Thus, they no longer worked side by side with their children. Where a son once forged ties with his father as he was taught how to run the farm or the family business, now he could follow his father’s example only by distancing himself from the daily work of the household, eventually leaving home to do his work. Historian John Demos notes:

The wrenching apart of work and home-life is one of the great themes in social history. And for fathers, in particular, the consequences can hardly be overestimated. Certain key elements of pre-modern fatherhood dwindled and disappeared (e.g., father as pedagogue, father as moral overseer, father as companion). . . .

Of course, fathers had always been involved in the provision of goods and services to their families; but before the nineteenth century such activity was embedded in a larger matrix of domestic sharing. . . . Now, for the first time, the central activity of fatherhood was cited outside one’s immediate household. Now, being fully a father meant being separated from one’s children for a considerable part of every working day. 2

By the 1950s fathers were gone such long hours they became guests in their own homes. The natural connection between fathers and their children was supposed to be preserved and strengthened by playing together. However, play, like work, also changed over the course of the century, becoming more structured, more costly, and less interactive.

Initially, the changing role of women in the family was more subtle because the kind of work they did remained the same. Yet how their tasks were carried out changed drastically over the 20th century, influenced by the modernization of America’s factories and businesses. “Housewives” were encouraged to organize, sterilize, and modernize. Experts urged them to purchase machines to do their physical labor and told them that market-produced goods and services were superior because they freed women to do the supposedly more important work of the mind.

Women were told that applying methods of factory and business management to their homes would ease their burdens and raise the status of household work by “professionalizing” it. Surprisingly, these innovations did neither. Machines tended to replace tasks once performed by husbands and children, while mothers continued to carry out the same basic duties. Houses and wardrobes expanded, standards for cleanliness increased, and new appliances encouraged more elaborate meal preparation. More time was spent shopping and driving children to activities. With husbands at work and older children in school, care of the house and young children now fell almost exclusively to mothers, actually lengthening their work day. 3 Moreover, much of a mother’s work began to be done in isolation. Work that was once enjoyable because it was social became lonely, boring, and monotonous.

Even the purpose of family work was given a facelift. Once performed to nurture and care for one another, it was reduced to “housework” and was done to create “atmosphere.” Since work in the home had “use value” instead of “exchange value,” it remained outside the market economy and its worth became invisible. Being a mother now meant spending long hours at a type of work that society said mattered little and should be “managed” to take no time at all.

Prior to modernization, children shared much of the hard work, laboring alongside their fathers and mothers in the house and on the farm or in a family business. This work was considered good for them—part of their education for adulthood. Children were expected to learn all things necessary for a good life by precept and example, and it was assumed that the lives of the adults surrounding them would be worthy of imitation.

With industrialization, children joined their families in factory work, but gradually employers split up families, often rejecting mothers and fathers in favor of the cheap labor provided by children. Many children began working long hours to help put bread on the family table. Their work was hard, often dangerous, and children lost fingers, limbs, and lives. The child labor movement was thus organized to protect the “thousands of boys and girls once employed in sweat shops and factories” from “the grasping greed of business.” 4 However, the actual changes were much more complex and the consequences more far-reaching. 5 Child labor laws, designed to end the abuses, also ended child labor.

At the same time that expectations for children to work were diminishing, new fashions in child rearing dictated that children needed to have their own money and be trained to spend it wisely. Eventually, the relationship of children and work inside the family completely reversed itself: children went from economic asset to pampered consumer.

“In almost every facet of our prosperous, contemporary lifestyle, we strive for the ease associated with Eden. . . . Back to Eden is not onward to Zion.”

Thus, for each family member the contribution to the family became increasingly abstract and ever distant from the labor of Adam and Eve, until the work given as a blessing to the first couple had all but disappeared. Today a man feels “free” if he can avoid any kind of physical labor—actual work in the fields is left to migrant workers and illegal aliens. Meanwhile, a woman is considered “free” if she chooses a career over mothering at home, freer still if she elects not to bear children at all.

In almost every facet of our prosperous, contemporary lifestyle, we strive for the ease associated with Eden. The more abstract and mental our work, the more distanced from physical labor, the higher the status it is accorded. Better off still is the individual who wins the lottery or inherits wealth and does not have to work at all. Our homes are designed to reduce the time we must spend in family work. An enviable vacation is one where all such work is done for us—where we are fed without preparing our meals, dressed without ironing our shirts, cleaned up after wherever we go, whatever we do.

Even the way we go about building relationships denies the saving power inherent in working side by side at something that requires us to cooperate in spite of differences. Rather, we “bond” with our children by getting the housework out of the way so the family can participate in structured “play.” We improve our marriages by getting away from the house and kids, from responsibility altogether, to communicate uninterrupted as if work, love, and living were not inseparably connected. We are so thoroughly convinced that the relationship itself, abstract and apart from life, is what matters that, a relationship free from lasting obligations—to marriage, children, or family labor—is fast becoming the ideal. At every turn, we are encouraged to seek an Eden-like bliss where we enjoy life’s bounties without working for them and where we don’t have to have children, at least not interrupting whatever we’re doing. 6

However, back to Eden is not onward to Zion. Adam and Eve entered mortality to do what they could not do in the Garden: to gain salvation by bringing forth, sustaining, and nourishing life. As they worked together in this stewardship, with an eye single to the glory of God, a deep and caring relationship would grow out of their shared daily experience. Today, the need for salvation has not changed; the opportunity to do family work has not changed; the love that blossoms as spouses labor together has not changed. Perhaps, then, we are still obligated to do the work of Adam and Eve.

For Our Sakes

The story of Adam and Eve raises an important question. How does ordinary, family-centered work like feeding, clothing, and nurturing a family—work that often seems endless and mundane—actually bless our lives? The answer is so obvious in common experience that it has become obscure: Family work links people. On a daily basis, the tasks we do to stay alive provide us with endless opportunities to recognize and fill the needs of others. Family work is a call to enact love, and it is a call that is universal. Throughout history, in every culture, whether in poverty or prosperity, there has been the ever-present need to shelter, clothe, feed, and care for each other.

Ironically, it is the very things commonly disliked about family work that offer the greatest possibilities for nurturing close relationships and forging family ties. Some people dislike family work because, they say, it is mindless. Yet chores that can be done with a minimum of concentration leave our minds free to focus on one another as we work together. We can talk, sing, or tell stories as we work. Working side by side tends to dissolve feelings of hierarchy, making it easier for children to discuss topics of concern with their parents. Unlike play, which usually requires mental concentration as well as physical involvement, family work invites intimate conversation between parent and child.

We also tend to think of household work as menial, and much of it is. Yet, because it is menial, even the smallest child can make a meaningful contribution. Children can learn to fold laundry, wash windows, or sort silverware with sufficient skill to feel valued as part of the family. Since daily tasks range from the simple to the complex, participants at every level can feel competent yet challenged, including the parents with their overall responsibility for coordinating tasks, people, and projects into a cooperative, working whole.

Another characteristic of ordinary family work that gives it such power is repetition. Almost as quickly as it is done, it must be redone. Dust gathers on furniture, dirt accumulates on floors, beds get messed up, children get hungry and dirty, meals are eaten, clothes become soiled. As any homemaker can tell you, the work is never done. When compared with the qualities of work that are prized in the public sphere, this aspect of family work seems to be just another reason to devalue it. However, each rendering of a task is a new invitation for all to enter the family circle. The most ordinary chores can become daily rituals of family love and belonging. Family identity is built moment by moment amidst the talking and teasing, the singing and storytelling, and even the quarreling and anguish that may attend such work sessions.

Some people also insist that family work is demeaning because it involves cleaning up after others in the most personal manner. Yet, in so doing, we observe their vulnerability and weaknesses in a way that forces us to admit that life is only possible day-to-day by the grace of God. We are also reminded of our own dependence on others who have done, and will do, such work for us. We are reminded that when we are fed, we could be hungry; when we are clean, we could be dirty; and when we are healthy and strong, we could be feeble and dependent. Family work is thus humbling work, helping us to acknowledge our unavoidable interdependence; encouraging (even requiring) us to sacrifice “self” for the good of the whole.

God gave us family work as a link to one another, as a link to Him, as a stepping stone toward salvation that is always available and that has the power to transform us spiritually as we transform others physically. This daily work of feeding and clothing and sheltering each other is perhaps the only opportunity all humanity has in common. Whatever the world takes from us, it cannot take away the daily maintenance needed for survival. Whether we find ourselves in wealth, poverty, or struggling as most of us do in day-to-day mediocrity, we need to be fed, to be clothed, to be sheltered, to be clean. And so does our neighbor.

When Christ instituted one of the most sacred of ordinances, one still performed today among the apostles, what symbolism did He choose? Of all the things He could have done as He prepared His apostles for His imminent death and instructed them on how to become one, He chose the washing of feet—a task ordinarily done in His time by the most humble of servants. When Peter objected, thinking that this was not the kind of work someone of Christ’s earthly, much less eternal stature would be expected to do, Christ made clear the importance of participating: “If I wash thee not, thou hast no part with me” ( John 13:8 ).

So after he had washed their feet, and had taken his garments, and was set down again, he said unto them, Know ye what I have done to you?

Ye call me Master and Lord: and ye say well; for so I am. If I then, your Lord and Master, have washed your feet; ye also ought to wash one another’s feet.

For I have given you an example, that ye should do as I have done to you. ( John 13:12–15 )

And so for our sakes this work seems mindless, menial, repetitive, and demeaning. This daily toiling is in honor of life itself. After all, isn’t this temporal work of tending to the necessary and routine currents of daily life, whether for our families or for our neighbors, the work we really came to Earth to do? By this humble service—this washing of one another’s feet—we sacrifice our pride and invite God to wash our own souls from sin. Indeed, such work embodies within it the condescension of the Savior himself. It is nothing less than doing unto Christ, by serving the least of our brethren, what He has already done for us.

Family Work in Modern Times

If family work is indeed what I say it is—a natural invitation to become Christlike devalued by a world that has shattered family relationships in its quest for gain and ease—what can be done? Families working harmoniously together at a relaxed pace is a wonderful ideal, but what about the realities of our day? Men do work away from home, and many feel out-of-step when it comes to family work. Children do go to school, and between homework and other activities do not welcome opportunities to work around the house. Whether mothers are employed outside the home or not, they often live in exhaustion, doing most of the family work without willing help.

Yet we cannot go back to a pre-industrial society where hard family work was unavoidable, nor would it be desirable or appropriate to do so.

Life for most people may have changed over the century, but opportunities to instill values, develop character, and work side by side remain. We have all seen how times of crises call forth such effort—war, hurricanes, earthquakes, floods—all disasters no one welcomes, but they provide opportunities for us to learn to care for one another. In truth, opportunities are no less available in our ordinary daily lives.

The length of this article does not allow for the discussion we really need to have at this point, and there will never be “five easy steps” to accomplish these ends. Rather, the eternal principles that govern family work will be uncovered by each of us according to our personal time line of discovery. The following, however, are several ideas that may be helpful.

Tilling the Soil.

Although tilling the soil for our sustenance is unrealistic for most Americans today, modern prophets have stressed the need to labor with the earth, if only in a small way. Former LDS Church President Spencer W. Kimball was particularly insistent on the need to grow gardens–not just as a food supply, but because of the “lessons of life” inherent in the process as well as the family bonds that could be strengthened:

I hope that we understand that, while having a garden, for instance, is often useful in reducing food costs and making available delicious fresh fruits and vegetables, it does much more than this. Who can gauge the value of that special chat between daughter and Dad as they weed or water the garden? How do we evaluate the good that comes from the obvious lessons of planting, cultivating, and the eternal law of the harvest? And how do we measure the family togetherness and cooperating that must accompany successful canning? Yes, we are laying up resources in store, but perhaps the greater good is contained in the lessons of life we learn as we live providently and extend to our children their pioneer heritage. (Emphasis in original.) 7

Exemplifying the Attitudes We Want Our Children to Have.

Until we feel about family work the way we want our children to feel about it, we will teach them nothing. If we dislike this work, they will know it. If we do not really consider it our work, they will know it. If we wish to hurry and get it out of the way or if we wish we were doing it alone so it could better meet our standards, they will know it. Most of us have grown up with a strong conviction that we are fortunate to live at a time when machines and prosperity and efficient organizational skills have relieved us of much of the hands-on work of sustaining daily life. If we wish to change our family habits on this matter, we must first change our own minds and hearts.

Refusing Technology That Interferes With Togetherness.

As we labor together in our families, we will begin to cherish certain work experiences, even difficult ones, for reasons we can’t explain. When technology comes along that streamlines that work, we need not rush out and buy it just because it promises to make our labor more efficient. Saving time and effort is not always the goal. When we choose to heat convenience foods in the microwave or to process vegetables in a noisy machine, we choose not to talk, laugh, and play as we peel and chop. Deciding which modern conveniences to live with is a personal matter. Some families love washing dishes together by hand; others would never give up the dishwasher. Before we accept a scientific “improvement,” we should ask ourselves what we are giving up for what we will gain.

Insisting Gently That Children Help.

A frequent temptation in our busy lives today is to do the necessary family work by ourselves. A mother, tired from a long day of work in the office, may find it easier to do the work herself than to add the extra job of getting a family member to help. A related temptation is to make each child responsible only for his own mess, to put away his own toys, to clean his own room, to do his own laundry, and then to consider this enough family work to require of a child. When we structure work this way, we may shortchange ourselves by minimizing the potential for growing together that comes from doing the work for and with each other.

Canadian scholars Joan Grusec and Lorenzo Cohen, along with Australian Jacqueline Goodnow, compared children who did “self-care tasks” such as cleaning up their own rooms or doing their own laundry, with children who participated in “family-care tasks” such as setting the table or cleaning up a space that is shared with others. They found that it is the work one does “for others” that leads to the development of concern for others, while “work that focuses on what is one’s ‘own,’” does not. Other studies have also reported a positive link between household work and observed actions of helpfulness toward others. In one international study, African children who did “predominantly family-care tasks [such as] fetching wood or water, looking after siblings, running errands for parents” showed a high degree of helpfulness while “children in the Northeast United States, whose primary task in the household was to clean their own room, were the least helpful of all the children in the six cultures that were studied.” 8

Avoiding a Business Mentality at Home.

Even with the best of intentions, most of us revert to “workplace” skills while doing family work. We overorganize and believe that children, like employees, won’t work unless they are “motivated,” supervised, and perhaps even paid. This line of thought will get us into trouble. Some managing, of course, is necessary and helpful—but not the kind that oversees from a distance. Rather, family work should be directed with the wisdom of a mentor who knows intimately both the task and the student, who appreciates both the limits and the possibilities of any given moment. A common error is to try to make the work “fun” with a game or contest, yet to chastise children when they become naturally playful (“off task,” to our thinking). Fond family memories often center around spontaneous fun while working, like pretending to be maids, drawing pictures in spilled flour, and wrapping up in towels to scrub the floor. Another error is to reward children monetarily for their efforts. According to financial writer Grace Weinstein, “Unless you want your children to think of you as an employer and of themselves not as family members but as employees, you should think long and hard about introducing money as a motivational force. Money distorts family feeling and weakens the members’ mutual support.” 9

Working Side by side With Our Children.

Assigning family work to our children while we expect to be free to do other activities only reinforces the attitudes of the world. LDS Church President Gordon B. Hinckley said: “Children need to work with their parents, to wash dishes with them, to mop floors with them, to mow lawns, to prune trees and shrubbery, to paint and fix up, to clean up, and to do a hundred other things in which they will learn that labor is the price of cleanliness, progress, and prosperity.” 10

Most of the important lessons that flow from family work are derived from the cooperative nature of the work. Christ said, “The Son can do nothing of himself, but what he seeth the Father do: for what things soever he doeth, these also doeth the Son likewise” ( John 5:19 ). Perhaps this concept is more literal than we have assumed.

Several years ago one of my students, a young mother of two daughters, wrote of the challenges she experienced learning to feel a strong bond with her firstborn. Because this daughter was born prematurely, she was taken from her mother and kept in isolation at the hospital for the first several weeks of her life. Even after the baby came home, she looked so fragile that the mother was afraid to hold her. She felt many of the inadequacies typical of new mothers, plus additional ones that came from her own rough childhood experiences. As time passed, she felt that she loved her daughter, but suffered feelings of deficiency, often to the point of tears, and wondered, “Why don’t I have that ‘natural bond’ with my first child that I do with my second?”

Then she learned about the idea of working together as a means to build bonds. She purposely included her daughter in her work around the house, and gradually, she recalls, “our relationship . . . deepened in a way that I had despaired of ever realizing.” She describes the moment she realized the change that had taken place:

One morning before the girls were to leave [to visit family in another state], Mandy and I were sitting and folding towels together, chattering away. As I looked at her, a sudden rush of maternal love flooded over me–it was no longer something that I had to work at. She looked up at me and must have read my heart in my expression. We fell laughing and crying into each other’s arms. She looked up at me and said, “Mom, what would you do without me?” I couldn’t even answer her, because the thought was too painful to entertain. 11

In a world that lauds the signing of peace treaties and the building of skyscrapers as the truly great work, how can we make such a big thing out of folding laundry? Gary Saul Morson, a professor of Russian literature at Northwestern University, argues convincingly that “the important events are not the great ones, but the infinitely numerous and apparently inconsequential ordinary ones, which, taken together, are far more effective and significant.” 12

To Bring Again Zion

Family work is a gift from the Lord to every mortal, a gift that transcends time, place, and circumstance. On a daily basis it calls us, sometimes forces us, to face our mortality, to ask for the grace of God, to admit that we need our neighbor and that our neighbor needs us. It provides us with a daily opportunity to recognize the needs of those around us and put them before our own. This invitation to serve one another in oneness of heart and mind can become a simple tool that, over time, will bring the peace that attends Zion.

I learned firsthand of the power of this ordinary work not only to bind families but to link people of different cultures when I accompanied a group of university students on a service and study experience in Mexico. The infant mortality rate in many of the villages was high, and we had been invited by community leaders to teach classes in basic nutrition and sanitation. Experts who had worked in developing countries told us that the one month we had to do this was not enough time to establish rapport and win the trust of the people, let alone do any teaching. But we did not have the luxury of more time.

In the first village, we arrived at the central plaza where we were to meet the leaders and families of the village. On our part, tension was high. The faces of the village men and women who slowly gathered were somber and expressionless. They are suspicious of us, I thought. A formal introduction ceremony had been planned. The village school children danced and sang songs, and our students sang. The expressions on the faces of the village adults didn’t change.

“Helping one another nurture children, care for the land, prepare food, and clean homes can bind lives together.”

Unexpectedly, I was invited to speak to the group and explain why we were there. What could I say? That we were “big brother” here to try to change the ways they had farmed and fed their families for hundreds of years? I quickly said a silent prayer, desirous of dispelling the feeling of hierarchy, anxious to create a sense of being on equal footing. I searched for the right words, trying to downplay the official reasons for our visit, and began, “We are students; we want to share some things we have learned. . . .” Then I surprised even myself by saying, “But what we are really here for is, we would like to learn to make tortillas.” The people laughed. After the formalities were over, several wonderful village couples came to us and said, “You can come to our house to make tortillas.” The next morning, we sent small groups of students to each of their homes, and we all learned to make tortillas. An almost instant rapport was established. Later, when we began classes, they were surprisingly well attended, with mothers sitting on the benches and fathers standing at the back of the hall listening and caring for little children.

Because our classes were taking time from the necessary work of fertilizing and weeding their crops, we asked one of the local leaders if we could go to the fields with them on the days when we did not teach and help them hoe and spread the fertilizer. His first response was, “No. You couldn’t do that. You are teachers; we are farmers.” I assured him that several of us had grown up on farms, that we could tell weeds from corn and beans, and in any case, we would be pleased if they would teach us. So we went to the fields. As we worked together, in some amazing way we became one. Artificial hierarchies dissolved as we made tortillas together, weeded together, ate lunch together, and together took little excursions to enjoy the beauty of the valley. When the month was over, our farewells were sad and sweet—we were sorry to leave such dear friends, but happy for the privilege of knowing them.

Over the next several years I saw this process repeated again and again in various settings. I am still in awe of the power of shared participation in the simple, everyday work of sustaining life. Helping one another nurture children, care for the land, prepare food, and clean homes can bind lives together. This is the power of family work, and it is this power, available in every home, no matter how troubled, that can end the turmoil of the family, begin to change the world, and bring again Zion.

- Study by Edelman Financial Services, May 5, 1999, (see https://www.kidsource.com/kidsource/content5/mothers.worth.html ).

- John Demos, “The Changing Faces of Fatherhood,” Past, Present, Personal: The Family and the Life Course in American History (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), pp. 51–52.

- See R. S. Cowan, More Work for Mother: The Ironies of Household Technology from the Open Hearth to the Microwave (New York: Basic Books, 1983).

- William A. McKeever, “The New Child Labor Movement,” Journal of Home Economics , vol. 5 (April 1913), pp. 137–139.

- See Viviana A. Zelizer, Pricing the Priceless Child (New York: Basic Books, 1985).

- See Germaine Greer, Sex and Destiny (New York: Harper & Row, 1984), and J. Van de Kaa, “Europe’s Second Demographic Transition,” Population Bulletin , vol. 42, no. 1 (March 1987), pp. 1–57.

- Spencer W. Kimball, “Welfare Services, The Gospel in Action,” Ensign , November 1977, p. 78.

- Joan E. Grusec, Jacqueline J. Goodnow, and Lorenzo Cohen, “Household Work and the Development of Concern for Others,” Developmental Psychology , vol. 32, no. 6 (1996), pp. 999–1007.

- Grace W. Weinstein, “Money Games Parents Play,” Redbook , August 1985, p. 107, taken from her book Children and Money: A Parents’ Guide (New York: New American Library, 1985).

- Gordon B. Hinckley, “Four Simple Things to Help Our Families and Our Nations,” Ensign , September 1996, p. 7.

- Michelle Cottingham, unpublished paper.

- Gary Saul Morson, “Prosaics: An Approach to the Humanities,” American Scholar , vol. 57 (Autumn 1988), p. 519.

More Articles

Family Focus

A House Undivided

More women are working outside the home—but they are still doing lion’s share of housework. Why?

The Imperfectly Happy Family

After suffering an aneurysm, Katy and her husband had to adjust their expectations for themselves and their children.

Divide or Conquer

Thoughts about divorce are common—perhaps even inevitable—and don’t mean the end of a relationship.

- Skip to content

- Skip to navigation

Household chores: good for children, good for your family

Children can learn a lot from doing household chores.

Doing chores helps children learn about what they need to do to care for themselves, a home and a family. They learn skills they can use in their adult lives, like preparing meals, cleaning, organising and gardening.

Being involved in chores also gives children experience of relationship skills like communicating clearly, negotiating, cooperating and working as a team.

And when children contribute to family life, they might feel competent and responsible . Even if they don’t enjoy the chore, when they keep going they can feel satisfied that they’ve finished the task.

And sharing housework can also help families work better and reduce family stress. When children help out, chores get done sooner, and parents have less to do. This frees up time for the family to do fun things together.

How to get children involved in chores

It’s best to start by choosing chores that work for children’s ages and abilities. Chores that are too hard can be frustrating – or even dangerous – and chores that are too easy might be boring.

Even young children can help with chores if you choose activities that are right for their age. You can start with simple jobs like packing up toys. Chores like this send the message that your child’s contribution is important.

It’s also important to think about chores or tasks that get your child involved in caring for the family as a whole. A simple one is getting your child to help with setting or clearing the table. Jobs like these are likely to give your child a sense of responsibility and participation.

If your child is old enough, you can have a family discussion about chores . This can reinforce the idea that the whole family contributes to how the household runs. Children over 6 years old can have a say in which chores they do.

You can motivate your child to get involved in chores by:

- doing the chore together until your child can do it on their own

- being clear about each person’s chores for the day or week – write them down so they’re easy to remember

- talking about why it’s great that a particular job has been done

- showing an interest in how your child has done the job

- praising positive behaviour like doing chores without being asked

- using a reward chart when you introduce a new chore.

Plenty of encouragement keeps children interested in helping. You can boost your child’s chances of success by explaining the job and telling your child they’re doing well. It’s also a good idea to thank your child for their contribution. This models gratitude and helps your child feel valued.

Pocket money for children’s chores

Some children are motivated to do chores for pocket money. But some families believe all family members have a responsibility to help, so they don’t give pocket money for chores.

If you decide to pay pocket money for chores, explain chores clearly and make sure the chores are regular, so there’s no confusion or bargaining about what needs to be done and when. For example, tell your child that tidying up their bedroom involves making their bed and putting their clothes away, and they need to do this each day.

Some families don’t link chores to pocket money but might pay extra pocket money for extra chores.

Chores for children of different ages

Here are ideas for chores for children of different ages.

Toddlers (2-3 years)

- Help to tidy up toys after playtime.

- Help to put laundry in the washing machine.

- Help to fill a pet’s water bowl.

Preschoolers (4-5 years)

- Set the table for meals.

- Help to prepare meals, under supervision.

- Help to put clean clothes into piles for each family member, ready to fold.

- Help to do the grocery shopping and put away groceries.

School-age children and pre-teens (6-11 years)

- Water the garden and indoor plants.

- Help to hang out clothes and fold washing.

- Take out rubbish.

- Help to choose meals and do the shopping.

- Help to prepare and serve meals, under supervision.

- Vacuum or sweep floors.

- Clean the bathroom sink, wipe down kitchen benches, or mop floors.

- Empty the dishwasher.

Teenagers (12-18 years) Teenagers can do the chores they did when they were younger, but they can be responsible for doing them on their own.

Teenagers can also take on more difficult chores. For example, teenagers could do the washing, clean the bathroom and toilet, mow lawns, stack the dishwasher, do basic grocery shopping, or cook a simple family meal once a week.

When choosing chores for teenagers, think of the skills you’d like them to learn.

You can keep children motivated by letting them change jobs from time to time. This is also a way of rotating chores fairly among family members.

Chores? Or No Chores? That Is a Question

It takes parental effort to get a teenager to give regular household help..

Posted January 14, 2024 | Reviewed by Tyler Woods

- A Parent's Role

- Find a family therapist near me

- Adolescent chores are unpaid personal and household work responsibilities that parents assign.

- Adolescents may resist chores because they express authority, are not fun to do, and cost personal freedom.

- Adolescent chores often requires parental effort and pursuit to be completed.

From family to family, there is no “right” or “wrong” when it comes to parents assigning or not assigning adolescent chores. Partly, I think, the decision can depend on personal history.

Reflecting back on their youth, parents may find different stories about "chore experience." Consider these two.

Account one: “I was the only child until my sister came along six years later. My parents believed their job was doing for us, not us doing for them. Although we helped sometimes, they pretty much took care of what needed doing around the home. The regular work we were expected to do was for school.” Children rarely did chores.

Account two : “We had five kids in the family, so it was all hands on deck most of the time. By age 4, I started helping, picking up, cleaning up, and daily preparation, while the older kids were expected to take some routine care of the younger ones. This was how our family was: everyone pitching in.” Children regularly did chores.

Chores are consistent work responsibilities that parents assign, most often to take care of her or his personal needs and to regularly fulfill some ongoing household functions. “You will do this for you” and “You will do this for us” are basic chore requirements. The justification is: “We’re all in this family together. Day-to-day, keeping a home takes a lot of work, so you need to do your share. Unpaid, these are family contributions that each of us is expected to freely make.”

The performance of chores has both specific and symbolic power. Specifically, they provide practical household help. “With chores, I do needed work.” Symbolically, they represent commitment: “Chores show my support of family.”

Resistance to chores

While the child, wanting to be like parents, welcomed giving this help as an empowering way of acting older, the more self-absorbed adolescent can resist and even resent these demands when she or he has better options. Common complaints about the necessity of chores that might include: “Why do I have to?” “I’m busy!” “I’m too tired!” “Not right now!” “I’ve got enough to do!”

Chores have three strikes against an adolescent liking them:

- They are being told what to do.

- They are work, and so not enjoyable.

- They are at the expense of personal freedom.

Timing of chores

This is why, if parents expect chores to be part of their adolescent’s growing responsibilities, they are best served by starting the practice early so it is assumed and unquestioned by the arrival of the teenage years. By age 3, the child has been encouraged to start helping out, and by age 5, she or he has assumed some regular self- management and small family responsibilities which the child can feel proud to do. Chores for older children tend to demand more responsibility. If parents wait until adolescence to start chores, it's often too late because by then, more adolescent resistance is likely to be aroused.

Dealing with resistance

Sometimes, to overcome resistance like argument, avoidance, and delay, parents may punish task resistance by withholding freedom. (“You can’t go unless your chores are done!”) Or they may materially reward chores by paying money (“Chores are how you earn your allowance”).

Personally, I think both these strategies are mistakes. In the first case, they make doing chores seem like a matter of free choice when it needs to be a no-choice family obligation . And in the second case they treat doing chores as a way of making money, when it needs to be donated labor . After all, parents don't get paid for all they do to maintain a home.

If you choose to have chores, it's best to treat them as routine family contributions that everyone kicks in for mutual support. Where there is resistance, resort to the best (albeit arduous) parenting strategy to get them done: relentless supervision. “Feel like it or not, in this family, chores are not a choice, they are part of your membership obligation to help support the family. Keeping after you is our obligation to ensure that they get done.”

And then, of course, be sure to thank the young person every time a chore is accomplished to avoid the complaint: “My parents never appreciate what I do to help!”

Deciding on chores

So, chores or no chores? There are arguments for both approaches.

Reasons why you might choose no chores:

- Chores create demands on parents.

- Completion takes parental insistence.

- Chores are one more thing to argue about.

- Dislike of chores can create dislike of parents.

- Chores are resented by teenagers who have enough to do.

Setting and supervising chores may just make extra work for weary parents.

Reasons why you might choose in favor of chores:

- Chores take household responsibility.

- Chores are tasks that build practical skills.

- Chores are family membership contributions.

- Chores are unpaid labor that support ongoing needs.

- Chores sacrifice some self-interest for the greater family good.

Doing regular chores helps children feel like a valued part of the family team. Whatever parents decide about their children and adolescents doing chores, I believe it is a debate worth having.

Carl Pickhardt Ph.D. is a psychologist in private counseling and public lecturing practice in Austin, Texas. His latest book is Holding On While Letting Go: Parenting Your Child Through the Four Freedoms of Adolescence.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Letter of Recommendation

In Defense of Never Learning How to Cook

I hated domesticity so much that for years, I lived happily without a kitchen. This $19 device helped me survive.

By Iva Dixit

Iva Dixit is a staff editor for the magazine.

I found it while walking through the home-goods section of T.J. Maxx, the American retail equivalent of the Garden of Earthly Delights, at 8:00 on a Tuesday night in 2015. It was two days after Easter, and in this Hieronymus Bosch land of shopping anarchy, the shelves were stocked with pastel-colored objects of uncertain usefulness: sacks of fruit-medley popcorn dyed green and purple; a giant tub of millennial-pink Himalayan crystal salt. Somewhere among these novelties I spotted a carelessly abandoned gadget calling itself the Dash Rapid Egg Cooker. The cashier who rang me up did not share my enthusiasm for the cheery cockiness of its packaging, which proclaimed that it “Perfectly Cooks 6 Eggs at a Time!” Baffled, she asked me a question, the answer to which would have embarrassed anyone but me: “Don’t you know how to boil water?”

No. I didn’t.