An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Korean Med Sci

- v.37(16); 2022 Apr 25

A Practical Guide to Writing Quantitative and Qualitative Research Questions and Hypotheses in Scholarly Articles

Edward barroga.

1 Department of General Education, Graduate School of Nursing Science, St. Luke’s International University, Tokyo, Japan.

Glafera Janet Matanguihan

2 Department of Biological Sciences, Messiah University, Mechanicsburg, PA, USA.

The development of research questions and the subsequent hypotheses are prerequisites to defining the main research purpose and specific objectives of a study. Consequently, these objectives determine the study design and research outcome. The development of research questions is a process based on knowledge of current trends, cutting-edge studies, and technological advances in the research field. Excellent research questions are focused and require a comprehensive literature search and in-depth understanding of the problem being investigated. Initially, research questions may be written as descriptive questions which could be developed into inferential questions. These questions must be specific and concise to provide a clear foundation for developing hypotheses. Hypotheses are more formal predictions about the research outcomes. These specify the possible results that may or may not be expected regarding the relationship between groups. Thus, research questions and hypotheses clarify the main purpose and specific objectives of the study, which in turn dictate the design of the study, its direction, and outcome. Studies developed from good research questions and hypotheses will have trustworthy outcomes with wide-ranging social and health implications.

INTRODUCTION

Scientific research is usually initiated by posing evidenced-based research questions which are then explicitly restated as hypotheses. 1 , 2 The hypotheses provide directions to guide the study, solutions, explanations, and expected results. 3 , 4 Both research questions and hypotheses are essentially formulated based on conventional theories and real-world processes, which allow the inception of novel studies and the ethical testing of ideas. 5 , 6

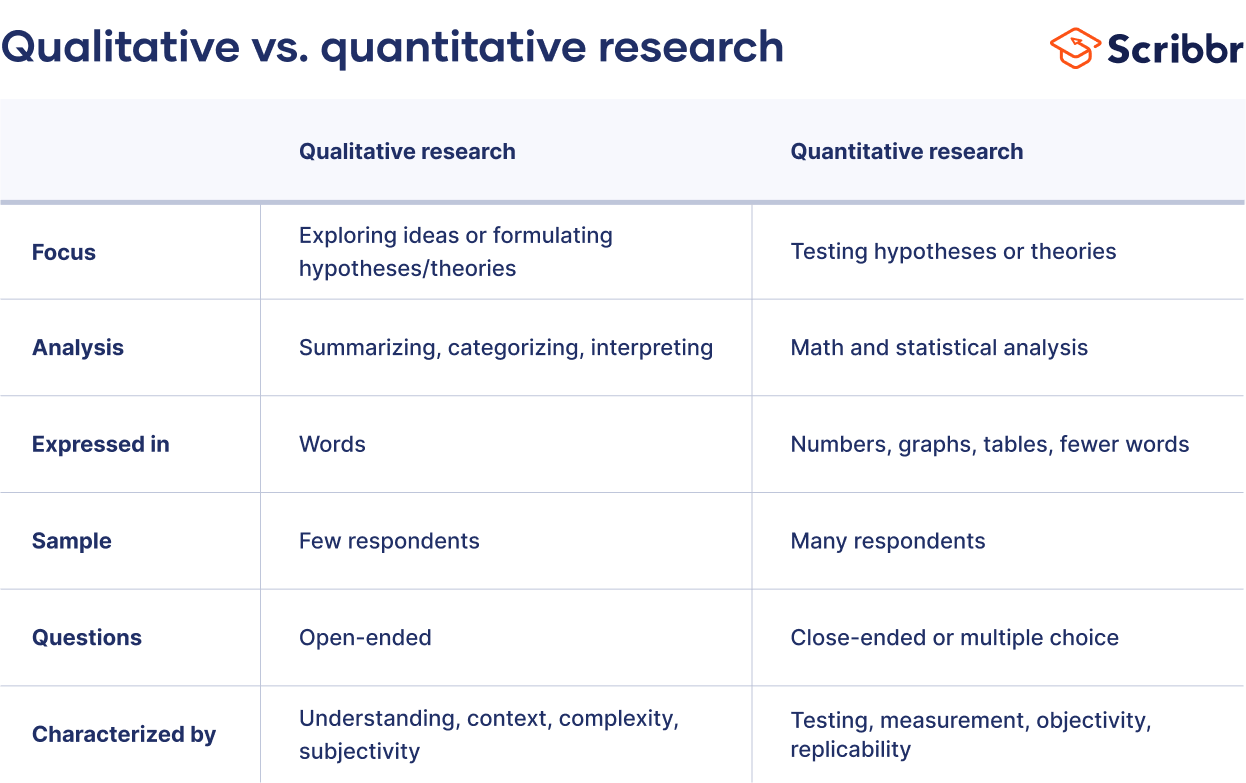

It is crucial to have knowledge of both quantitative and qualitative research 2 as both types of research involve writing research questions and hypotheses. 7 However, these crucial elements of research are sometimes overlooked; if not overlooked, then framed without the forethought and meticulous attention it needs. Planning and careful consideration are needed when developing quantitative or qualitative research, particularly when conceptualizing research questions and hypotheses. 4

There is a continuing need to support researchers in the creation of innovative research questions and hypotheses, as well as for journal articles that carefully review these elements. 1 When research questions and hypotheses are not carefully thought of, unethical studies and poor outcomes usually ensue. Carefully formulated research questions and hypotheses define well-founded objectives, which in turn determine the appropriate design, course, and outcome of the study. This article then aims to discuss in detail the various aspects of crafting research questions and hypotheses, with the goal of guiding researchers as they develop their own. Examples from the authors and peer-reviewed scientific articles in the healthcare field are provided to illustrate key points.

DEFINITIONS AND RELATIONSHIP OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

A research question is what a study aims to answer after data analysis and interpretation. The answer is written in length in the discussion section of the paper. Thus, the research question gives a preview of the different parts and variables of the study meant to address the problem posed in the research question. 1 An excellent research question clarifies the research writing while facilitating understanding of the research topic, objective, scope, and limitations of the study. 5

On the other hand, a research hypothesis is an educated statement of an expected outcome. This statement is based on background research and current knowledge. 8 , 9 The research hypothesis makes a specific prediction about a new phenomenon 10 or a formal statement on the expected relationship between an independent variable and a dependent variable. 3 , 11 It provides a tentative answer to the research question to be tested or explored. 4

Hypotheses employ reasoning to predict a theory-based outcome. 10 These can also be developed from theories by focusing on components of theories that have not yet been observed. 10 The validity of hypotheses is often based on the testability of the prediction made in a reproducible experiment. 8

Conversely, hypotheses can also be rephrased as research questions. Several hypotheses based on existing theories and knowledge may be needed to answer a research question. Developing ethical research questions and hypotheses creates a research design that has logical relationships among variables. These relationships serve as a solid foundation for the conduct of the study. 4 , 11 Haphazardly constructed research questions can result in poorly formulated hypotheses and improper study designs, leading to unreliable results. Thus, the formulations of relevant research questions and verifiable hypotheses are crucial when beginning research. 12

CHARACTERISTICS OF GOOD RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Excellent research questions are specific and focused. These integrate collective data and observations to confirm or refute the subsequent hypotheses. Well-constructed hypotheses are based on previous reports and verify the research context. These are realistic, in-depth, sufficiently complex, and reproducible. More importantly, these hypotheses can be addressed and tested. 13

There are several characteristics of well-developed hypotheses. Good hypotheses are 1) empirically testable 7 , 10 , 11 , 13 ; 2) backed by preliminary evidence 9 ; 3) testable by ethical research 7 , 9 ; 4) based on original ideas 9 ; 5) have evidenced-based logical reasoning 10 ; and 6) can be predicted. 11 Good hypotheses can infer ethical and positive implications, indicating the presence of a relationship or effect relevant to the research theme. 7 , 11 These are initially developed from a general theory and branch into specific hypotheses by deductive reasoning. In the absence of a theory to base the hypotheses, inductive reasoning based on specific observations or findings form more general hypotheses. 10

TYPES OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Research questions and hypotheses are developed according to the type of research, which can be broadly classified into quantitative and qualitative research. We provide a summary of the types of research questions and hypotheses under quantitative and qualitative research categories in Table 1 .

Research questions in quantitative research

In quantitative research, research questions inquire about the relationships among variables being investigated and are usually framed at the start of the study. These are precise and typically linked to the subject population, dependent and independent variables, and research design. 1 Research questions may also attempt to describe the behavior of a population in relation to one or more variables, or describe the characteristics of variables to be measured ( descriptive research questions ). 1 , 5 , 14 These questions may also aim to discover differences between groups within the context of an outcome variable ( comparative research questions ), 1 , 5 , 14 or elucidate trends and interactions among variables ( relationship research questions ). 1 , 5 We provide examples of descriptive, comparative, and relationship research questions in quantitative research in Table 2 .

Hypotheses in quantitative research

In quantitative research, hypotheses predict the expected relationships among variables. 15 Relationships among variables that can be predicted include 1) between a single dependent variable and a single independent variable ( simple hypothesis ) or 2) between two or more independent and dependent variables ( complex hypothesis ). 4 , 11 Hypotheses may also specify the expected direction to be followed and imply an intellectual commitment to a particular outcome ( directional hypothesis ) 4 . On the other hand, hypotheses may not predict the exact direction and are used in the absence of a theory, or when findings contradict previous studies ( non-directional hypothesis ). 4 In addition, hypotheses can 1) define interdependency between variables ( associative hypothesis ), 4 2) propose an effect on the dependent variable from manipulation of the independent variable ( causal hypothesis ), 4 3) state a negative relationship between two variables ( null hypothesis ), 4 , 11 , 15 4) replace the working hypothesis if rejected ( alternative hypothesis ), 15 explain the relationship of phenomena to possibly generate a theory ( working hypothesis ), 11 5) involve quantifiable variables that can be tested statistically ( statistical hypothesis ), 11 6) or express a relationship whose interlinks can be verified logically ( logical hypothesis ). 11 We provide examples of simple, complex, directional, non-directional, associative, causal, null, alternative, working, statistical, and logical hypotheses in quantitative research, as well as the definition of quantitative hypothesis-testing research in Table 3 .

Research questions in qualitative research

Unlike research questions in quantitative research, research questions in qualitative research are usually continuously reviewed and reformulated. The central question and associated subquestions are stated more than the hypotheses. 15 The central question broadly explores a complex set of factors surrounding the central phenomenon, aiming to present the varied perspectives of participants. 15

There are varied goals for which qualitative research questions are developed. These questions can function in several ways, such as to 1) identify and describe existing conditions ( contextual research question s); 2) describe a phenomenon ( descriptive research questions ); 3) assess the effectiveness of existing methods, protocols, theories, or procedures ( evaluation research questions ); 4) examine a phenomenon or analyze the reasons or relationships between subjects or phenomena ( explanatory research questions ); or 5) focus on unknown aspects of a particular topic ( exploratory research questions ). 5 In addition, some qualitative research questions provide new ideas for the development of theories and actions ( generative research questions ) or advance specific ideologies of a position ( ideological research questions ). 1 Other qualitative research questions may build on a body of existing literature and become working guidelines ( ethnographic research questions ). Research questions may also be broadly stated without specific reference to the existing literature or a typology of questions ( phenomenological research questions ), may be directed towards generating a theory of some process ( grounded theory questions ), or may address a description of the case and the emerging themes ( qualitative case study questions ). 15 We provide examples of contextual, descriptive, evaluation, explanatory, exploratory, generative, ideological, ethnographic, phenomenological, grounded theory, and qualitative case study research questions in qualitative research in Table 4 , and the definition of qualitative hypothesis-generating research in Table 5 .

Qualitative studies usually pose at least one central research question and several subquestions starting with How or What . These research questions use exploratory verbs such as explore or describe . These also focus on one central phenomenon of interest, and may mention the participants and research site. 15

Hypotheses in qualitative research

Hypotheses in qualitative research are stated in the form of a clear statement concerning the problem to be investigated. Unlike in quantitative research where hypotheses are usually developed to be tested, qualitative research can lead to both hypothesis-testing and hypothesis-generating outcomes. 2 When studies require both quantitative and qualitative research questions, this suggests an integrative process between both research methods wherein a single mixed-methods research question can be developed. 1

FRAMEWORKS FOR DEVELOPING RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Research questions followed by hypotheses should be developed before the start of the study. 1 , 12 , 14 It is crucial to develop feasible research questions on a topic that is interesting to both the researcher and the scientific community. This can be achieved by a meticulous review of previous and current studies to establish a novel topic. Specific areas are subsequently focused on to generate ethical research questions. The relevance of the research questions is evaluated in terms of clarity of the resulting data, specificity of the methodology, objectivity of the outcome, depth of the research, and impact of the study. 1 , 5 These aspects constitute the FINER criteria (i.e., Feasible, Interesting, Novel, Ethical, and Relevant). 1 Clarity and effectiveness are achieved if research questions meet the FINER criteria. In addition to the FINER criteria, Ratan et al. described focus, complexity, novelty, feasibility, and measurability for evaluating the effectiveness of research questions. 14

The PICOT and PEO frameworks are also used when developing research questions. 1 The following elements are addressed in these frameworks, PICOT: P-population/patients/problem, I-intervention or indicator being studied, C-comparison group, O-outcome of interest, and T-timeframe of the study; PEO: P-population being studied, E-exposure to preexisting conditions, and O-outcome of interest. 1 Research questions are also considered good if these meet the “FINERMAPS” framework: Feasible, Interesting, Novel, Ethical, Relevant, Manageable, Appropriate, Potential value/publishable, and Systematic. 14

As we indicated earlier, research questions and hypotheses that are not carefully formulated result in unethical studies or poor outcomes. To illustrate this, we provide some examples of ambiguous research question and hypotheses that result in unclear and weak research objectives in quantitative research ( Table 6 ) 16 and qualitative research ( Table 7 ) 17 , and how to transform these ambiguous research question(s) and hypothesis(es) into clear and good statements.

a These statements were composed for comparison and illustrative purposes only.

b These statements are direct quotes from Higashihara and Horiuchi. 16

a This statement is a direct quote from Shimoda et al. 17

The other statements were composed for comparison and illustrative purposes only.

CONSTRUCTING RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

To construct effective research questions and hypotheses, it is very important to 1) clarify the background and 2) identify the research problem at the outset of the research, within a specific timeframe. 9 Then, 3) review or conduct preliminary research to collect all available knowledge about the possible research questions by studying theories and previous studies. 18 Afterwards, 4) construct research questions to investigate the research problem. Identify variables to be accessed from the research questions 4 and make operational definitions of constructs from the research problem and questions. Thereafter, 5) construct specific deductive or inductive predictions in the form of hypotheses. 4 Finally, 6) state the study aims . This general flow for constructing effective research questions and hypotheses prior to conducting research is shown in Fig. 1 .

Research questions are used more frequently in qualitative research than objectives or hypotheses. 3 These questions seek to discover, understand, explore or describe experiences by asking “What” or “How.” The questions are open-ended to elicit a description rather than to relate variables or compare groups. The questions are continually reviewed, reformulated, and changed during the qualitative study. 3 Research questions are also used more frequently in survey projects than hypotheses in experiments in quantitative research to compare variables and their relationships.

Hypotheses are constructed based on the variables identified and as an if-then statement, following the template, ‘If a specific action is taken, then a certain outcome is expected.’ At this stage, some ideas regarding expectations from the research to be conducted must be drawn. 18 Then, the variables to be manipulated (independent) and influenced (dependent) are defined. 4 Thereafter, the hypothesis is stated and refined, and reproducible data tailored to the hypothesis are identified, collected, and analyzed. 4 The hypotheses must be testable and specific, 18 and should describe the variables and their relationships, the specific group being studied, and the predicted research outcome. 18 Hypotheses construction involves a testable proposition to be deduced from theory, and independent and dependent variables to be separated and measured separately. 3 Therefore, good hypotheses must be based on good research questions constructed at the start of a study or trial. 12

In summary, research questions are constructed after establishing the background of the study. Hypotheses are then developed based on the research questions. Thus, it is crucial to have excellent research questions to generate superior hypotheses. In turn, these would determine the research objectives and the design of the study, and ultimately, the outcome of the research. 12 Algorithms for building research questions and hypotheses are shown in Fig. 2 for quantitative research and in Fig. 3 for qualitative research.

EXAMPLES OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS FROM PUBLISHED ARTICLES

- EXAMPLE 1. Descriptive research question (quantitative research)

- - Presents research variables to be assessed (distinct phenotypes and subphenotypes)

- “BACKGROUND: Since COVID-19 was identified, its clinical and biological heterogeneity has been recognized. Identifying COVID-19 phenotypes might help guide basic, clinical, and translational research efforts.

- RESEARCH QUESTION: Does the clinical spectrum of patients with COVID-19 contain distinct phenotypes and subphenotypes? ” 19

- EXAMPLE 2. Relationship research question (quantitative research)

- - Shows interactions between dependent variable (static postural control) and independent variable (peripheral visual field loss)

- “Background: Integration of visual, vestibular, and proprioceptive sensations contributes to postural control. People with peripheral visual field loss have serious postural instability. However, the directional specificity of postural stability and sensory reweighting caused by gradual peripheral visual field loss remain unclear.

- Research question: What are the effects of peripheral visual field loss on static postural control ?” 20

- EXAMPLE 3. Comparative research question (quantitative research)

- - Clarifies the difference among groups with an outcome variable (patients enrolled in COMPERA with moderate PH or severe PH in COPD) and another group without the outcome variable (patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IPAH))

- “BACKGROUND: Pulmonary hypertension (PH) in COPD is a poorly investigated clinical condition.

- RESEARCH QUESTION: Which factors determine the outcome of PH in COPD?

- STUDY DESIGN AND METHODS: We analyzed the characteristics and outcome of patients enrolled in the Comparative, Prospective Registry of Newly Initiated Therapies for Pulmonary Hypertension (COMPERA) with moderate or severe PH in COPD as defined during the 6th PH World Symposium who received medical therapy for PH and compared them with patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IPAH) .” 21

- EXAMPLE 4. Exploratory research question (qualitative research)

- - Explores areas that have not been fully investigated (perspectives of families and children who receive care in clinic-based child obesity treatment) to have a deeper understanding of the research problem

- “Problem: Interventions for children with obesity lead to only modest improvements in BMI and long-term outcomes, and data are limited on the perspectives of families of children with obesity in clinic-based treatment. This scoping review seeks to answer the question: What is known about the perspectives of families and children who receive care in clinic-based child obesity treatment? This review aims to explore the scope of perspectives reported by families of children with obesity who have received individualized outpatient clinic-based obesity treatment.” 22

- EXAMPLE 5. Relationship research question (quantitative research)

- - Defines interactions between dependent variable (use of ankle strategies) and independent variable (changes in muscle tone)

- “Background: To maintain an upright standing posture against external disturbances, the human body mainly employs two types of postural control strategies: “ankle strategy” and “hip strategy.” While it has been reported that the magnitude of the disturbance alters the use of postural control strategies, it has not been elucidated how the level of muscle tone, one of the crucial parameters of bodily function, determines the use of each strategy. We have previously confirmed using forward dynamics simulations of human musculoskeletal models that an increased muscle tone promotes the use of ankle strategies. The objective of the present study was to experimentally evaluate a hypothesis: an increased muscle tone promotes the use of ankle strategies. Research question: Do changes in the muscle tone affect the use of ankle strategies ?” 23

EXAMPLES OF HYPOTHESES IN PUBLISHED ARTICLES

- EXAMPLE 1. Working hypothesis (quantitative research)

- - A hypothesis that is initially accepted for further research to produce a feasible theory

- “As fever may have benefit in shortening the duration of viral illness, it is plausible to hypothesize that the antipyretic efficacy of ibuprofen may be hindering the benefits of a fever response when taken during the early stages of COVID-19 illness .” 24

- “In conclusion, it is plausible to hypothesize that the antipyretic efficacy of ibuprofen may be hindering the benefits of a fever response . The difference in perceived safety of these agents in COVID-19 illness could be related to the more potent efficacy to reduce fever with ibuprofen compared to acetaminophen. Compelling data on the benefit of fever warrant further research and review to determine when to treat or withhold ibuprofen for early stage fever for COVID-19 and other related viral illnesses .” 24

- EXAMPLE 2. Exploratory hypothesis (qualitative research)

- - Explores particular areas deeper to clarify subjective experience and develop a formal hypothesis potentially testable in a future quantitative approach

- “We hypothesized that when thinking about a past experience of help-seeking, a self distancing prompt would cause increased help-seeking intentions and more favorable help-seeking outcome expectations .” 25

- “Conclusion

- Although a priori hypotheses were not supported, further research is warranted as results indicate the potential for using self-distancing approaches to increasing help-seeking among some people with depressive symptomatology.” 25

- EXAMPLE 3. Hypothesis-generating research to establish a framework for hypothesis testing (qualitative research)

- “We hypothesize that compassionate care is beneficial for patients (better outcomes), healthcare systems and payers (lower costs), and healthcare providers (lower burnout). ” 26

- Compassionomics is the branch of knowledge and scientific study of the effects of compassionate healthcare. Our main hypotheses are that compassionate healthcare is beneficial for (1) patients, by improving clinical outcomes, (2) healthcare systems and payers, by supporting financial sustainability, and (3) HCPs, by lowering burnout and promoting resilience and well-being. The purpose of this paper is to establish a scientific framework for testing the hypotheses above . If these hypotheses are confirmed through rigorous research, compassionomics will belong in the science of evidence-based medicine, with major implications for all healthcare domains.” 26

- EXAMPLE 4. Statistical hypothesis (quantitative research)

- - An assumption is made about the relationship among several population characteristics ( gender differences in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of adults with ADHD ). Validity is tested by statistical experiment or analysis ( chi-square test, Students t-test, and logistic regression analysis)

- “Our research investigated gender differences in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of adults with ADHD in a Japanese clinical sample. Due to unique Japanese cultural ideals and expectations of women's behavior that are in opposition to ADHD symptoms, we hypothesized that women with ADHD experience more difficulties and present more dysfunctions than men . We tested the following hypotheses: first, women with ADHD have more comorbidities than men with ADHD; second, women with ADHD experience more social hardships than men, such as having less full-time employment and being more likely to be divorced.” 27

- “Statistical Analysis

- ( text omitted ) Between-gender comparisons were made using the chi-squared test for categorical variables and Students t-test for continuous variables…( text omitted ). A logistic regression analysis was performed for employment status, marital status, and comorbidity to evaluate the independent effects of gender on these dependent variables.” 27

EXAMPLES OF HYPOTHESIS AS WRITTEN IN PUBLISHED ARTICLES IN RELATION TO OTHER PARTS

- EXAMPLE 1. Background, hypotheses, and aims are provided

- “Pregnant women need skilled care during pregnancy and childbirth, but that skilled care is often delayed in some countries …( text omitted ). The focused antenatal care (FANC) model of WHO recommends that nurses provide information or counseling to all pregnant women …( text omitted ). Job aids are visual support materials that provide the right kind of information using graphics and words in a simple and yet effective manner. When nurses are not highly trained or have many work details to attend to, these job aids can serve as a content reminder for the nurses and can be used for educating their patients (Jennings, Yebadokpo, Affo, & Agbogbe, 2010) ( text omitted ). Importantly, additional evidence is needed to confirm how job aids can further improve the quality of ANC counseling by health workers in maternal care …( text omitted )” 28

- “ This has led us to hypothesize that the quality of ANC counseling would be better if supported by job aids. Consequently, a better quality of ANC counseling is expected to produce higher levels of awareness concerning the danger signs of pregnancy and a more favorable impression of the caring behavior of nurses .” 28

- “This study aimed to examine the differences in the responses of pregnant women to a job aid-supported intervention during ANC visit in terms of 1) their understanding of the danger signs of pregnancy and 2) their impression of the caring behaviors of nurses to pregnant women in rural Tanzania.” 28

- EXAMPLE 2. Background, hypotheses, and aims are provided

- “We conducted a two-arm randomized controlled trial (RCT) to evaluate and compare changes in salivary cortisol and oxytocin levels of first-time pregnant women between experimental and control groups. The women in the experimental group touched and held an infant for 30 min (experimental intervention protocol), whereas those in the control group watched a DVD movie of an infant (control intervention protocol). The primary outcome was salivary cortisol level and the secondary outcome was salivary oxytocin level.” 29

- “ We hypothesize that at 30 min after touching and holding an infant, the salivary cortisol level will significantly decrease and the salivary oxytocin level will increase in the experimental group compared with the control group .” 29

- EXAMPLE 3. Background, aim, and hypothesis are provided

- “In countries where the maternal mortality ratio remains high, antenatal education to increase Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness (BPCR) is considered one of the top priorities [1]. BPCR includes birth plans during the antenatal period, such as the birthplace, birth attendant, transportation, health facility for complications, expenses, and birth materials, as well as family coordination to achieve such birth plans. In Tanzania, although increasing, only about half of all pregnant women attend an antenatal clinic more than four times [4]. Moreover, the information provided during antenatal care (ANC) is insufficient. In the resource-poor settings, antenatal group education is a potential approach because of the limited time for individual counseling at antenatal clinics.” 30

- “This study aimed to evaluate an antenatal group education program among pregnant women and their families with respect to birth-preparedness and maternal and infant outcomes in rural villages of Tanzania.” 30

- “ The study hypothesis was if Tanzanian pregnant women and their families received a family-oriented antenatal group education, they would (1) have a higher level of BPCR, (2) attend antenatal clinic four or more times, (3) give birth in a health facility, (4) have less complications of women at birth, and (5) have less complications and deaths of infants than those who did not receive the education .” 30

Research questions and hypotheses are crucial components to any type of research, whether quantitative or qualitative. These questions should be developed at the very beginning of the study. Excellent research questions lead to superior hypotheses, which, like a compass, set the direction of research, and can often determine the successful conduct of the study. Many research studies have floundered because the development of research questions and subsequent hypotheses was not given the thought and meticulous attention needed. The development of research questions and hypotheses is an iterative process based on extensive knowledge of the literature and insightful grasp of the knowledge gap. Focused, concise, and specific research questions provide a strong foundation for constructing hypotheses which serve as formal predictions about the research outcomes. Research questions and hypotheses are crucial elements of research that should not be overlooked. They should be carefully thought of and constructed when planning research. This avoids unethical studies and poor outcomes by defining well-founded objectives that determine the design, course, and outcome of the study.

Disclosure: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions:

- Conceptualization: Barroga E, Matanguihan GJ.

- Methodology: Barroga E, Matanguihan GJ.

- Writing - original draft: Barroga E, Matanguihan GJ.

- Writing - review & editing: Barroga E, Matanguihan GJ.

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Recent quantitative research on determinants of health in high income countries: A scoping review

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Centre for Health Economics Research and Modelling Infectious Diseases, Vaccine and Infectious Disease Institute, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing

- Vladimira Varbanova,

- Philippe Beutels

- Published: September 17, 2020

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239031

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

Identifying determinants of health and understanding their role in health production constitutes an important research theme. We aimed to document the state of recent multi-country research on this theme in the literature.

We followed the PRISMA-ScR guidelines to systematically identify, triage and review literature (January 2013—July 2019). We searched for studies that performed cross-national statistical analyses aiming to evaluate the impact of one or more aggregate level determinants on one or more general population health outcomes in high-income countries. To assess in which combinations and to what extent individual (or thematically linked) determinants had been studied together, we performed multidimensional scaling and cluster analysis.

Sixty studies were selected, out of an original yield of 3686. Life-expectancy and overall mortality were the most widely used population health indicators, while determinants came from the areas of healthcare, culture, politics, socio-economics, environment, labor, fertility, demographics, life-style, and psychology. The family of regression models was the predominant statistical approach. Results from our multidimensional scaling showed that a relatively tight core of determinants have received much attention, as main covariates of interest or controls, whereas the majority of other determinants were studied in very limited contexts. We consider findings from these studies regarding the importance of any given health determinant inconclusive at present. Across a multitude of model specifications, different country samples, and varying time periods, effects fluctuated between statistically significant and not significant, and between beneficial and detrimental to health.

Conclusions

We conclude that efforts to understand the underlying mechanisms of population health are far from settled, and the present state of research on the topic leaves much to be desired. It is essential that future research considers multiple factors simultaneously and takes advantage of more sophisticated methodology with regards to quantifying health as well as analyzing determinants’ influence.

Citation: Varbanova V, Beutels P (2020) Recent quantitative research on determinants of health in high income countries: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 15(9): e0239031. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239031

Editor: Amir Radfar, University of Central Florida, UNITED STATES

Received: November 14, 2019; Accepted: August 28, 2020; Published: September 17, 2020

Copyright: © 2020 Varbanova, Beutels. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding: This study (and VV) is funded by the Research Foundation Flanders ( https://www.fwo.be/en/ ), FWO project number G0D5917N, award obtained by PB. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Identifying the key drivers of population health is a core subject in public health and health economics research. Between-country comparative research on the topic is challenging. In order to be relevant for policy, it requires disentangling different interrelated drivers of “good health”, each having different degrees of importance in different contexts.

“Good health”–physical and psychological, subjective and objective–can be defined and measured using a variety of approaches, depending on which aspect of health is the focus. A major distinction can be made between health measurements at the individual level or some aggregate level, such as a neighborhood, a region or a country. In view of this, a great diversity of specific research topics exists on the drivers of what constitutes individual or aggregate “good health”, including those focusing on health inequalities, the gender gap in longevity, and regional mortality and longevity differences.

The current scoping review focuses on determinants of population health. Stated as such, this topic is quite broad. Indeed, we are interested in the very general question of what methods have been used to make the most of increasingly available region or country-specific databases to understand the drivers of population health through inter-country comparisons. Existing reviews indicate that researchers thus far tend to adopt a narrower focus. Usually, attention is given to only one health outcome at a time, with further geographical and/or population [ 1 , 2 ] restrictions. In some cases, the impact of one or more interventions is at the core of the review [ 3 – 7 ], while in others it is the relationship between health and just one particular predictor, e.g., income inequality, access to healthcare, government mechanisms [ 8 – 13 ]. Some relatively recent reviews on the subject of social determinants of health [ 4 – 6 , 14 – 17 ] have considered a number of indicators potentially influencing health as opposed to a single one. One review defines “social determinants” as “the social, economic, and political conditions that influence the health of individuals and populations” [ 17 ] while another refers even more broadly to “the factors apart from medical care” [ 15 ].

In the present work, we aimed to be more inclusive, setting no limitations on the nature of possible health correlates, as well as making use of a multitude of commonly accepted measures of general population health. The goal of this scoping review was to document the state of the art in the recent published literature on determinants of population health, with a particular focus on the types of determinants selected and the methodology used. In doing so, we also report the main characteristics of the results these studies found. The materials collected in this review are intended to inform our (and potentially other researchers’) future analyses on this topic. Since the production of health is subject to the law of diminishing marginal returns, we focused our review on those studies that included countries where a high standard of wealth has been achieved for some time, i.e., high-income countries belonging to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) or Europe. Adding similar reviews for other country income groups is of limited interest to the research we plan to do in this area.

In view of its focus on data and methods, rather than results, a formal protocol was not registered prior to undertaking this review, but the procedure followed the guidelines of the PRISMA statement for scoping reviews [ 18 ].

We focused on multi-country studies investigating the potential associations between any aggregate level (region/city/country) determinant and general measures of population health (e.g., life expectancy, mortality rate).

Within the query itself, we listed well-established population health indicators as well as the six world regions, as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO). We searched only in the publications’ titles in order to keep the number of hits manageable, and the ratio of broadly relevant abstracts over all abstracts in the order of magnitude of 10% (based on a series of time-focused trial runs). The search strategy was developed iteratively between the two authors and is presented in S1 Appendix . The search was performed by VV in PubMed and Web of Science on the 16 th of July, 2019, without any language restrictions, and with a start date set to the 1 st of January, 2013, as we were interested in the latest developments in this area of research.

Eligibility criteria

Records obtained via the search methods described above were screened independently by the two authors. Consistency between inclusion/exclusion decisions was approximately 90% and the 43 instances where uncertainty existed were judged through discussion. Articles were included subject to meeting the following requirements: (a) the paper was a full published report of an original empirical study investigating the impact of at least one aggregate level (city/region/country) factor on at least one health indicator (or self-reported health) of the general population (the only admissible “sub-populations” were those based on gender and/or age); (b) the study employed statistical techniques (calculating correlations, at the very least) and was not purely descriptive or theoretical in nature; (c) the analysis involved at least two countries or at least two regions or cities (or another aggregate level) in at least two different countries; (d) the health outcome was not differentiated according to some socio-economic factor and thus studied in terms of inequality (with the exception of gender and age differentiations); (e) mortality, in case it was one of the health indicators under investigation, was strictly “total” or “all-cause” (no cause-specific or determinant-attributable mortality).

Data extraction

The following pieces of information were extracted in an Excel table from the full text of each eligible study (primarily by VV, consulting with PB in case of doubt): health outcome(s), determinants, statistical methodology, level of analysis, results, type of data, data sources, time period, countries. The evidence is synthesized according to these extracted data (often directly reflected in the section headings), using a narrative form accompanied by a “summary-of-findings” table and a graph.

Search and selection

The initial yield contained 4583 records, reduced to 3686 after removal of duplicates ( Fig 1 ). Based on title and abstract screening, 3271 records were excluded because they focused on specific medical condition(s) or specific populations (based on morbidity or some other factor), dealt with intervention effectiveness, with theoretical or non-health related issues, or with animals or plants. Of the remaining 415 papers, roughly half were disqualified upon full-text consideration, mostly due to using an outcome not of interest to us (e.g., health inequality), measuring and analyzing determinants and outcomes exclusively at the individual level, performing analyses one country at a time, employing indices that are a mixture of both health indicators and health determinants, or not utilizing potential health determinants at all. After this second stage of the screening process, 202 papers were deemed eligible for inclusion. This group was further dichotomized according to level of economic development of the countries or regions under study, using membership of the OECD or Europe as a reference “cut-off” point. Sixty papers were judged to include high-income countries, and the remaining 142 included either low- or middle-income countries or a mix of both these levels of development. The rest of this report outlines findings in relation to high-income countries only, reflecting our own primary research interests. Nonetheless, we chose to report our search yield for the other income groups for two reasons. First, to gauge the relative interest in applied published research for these different income levels; and second, to enable other researchers with a focus on determinants of health in other countries to use the extraction we made here.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239031.g001

Health outcomes

The most frequent population health indicator, life expectancy (LE), was present in 24 of the 60 studies. Apart from “life expectancy at birth” (representing the average life-span a newborn is expected to have if current mortality rates remain constant), also called “period LE” by some [ 19 , 20 ], we encountered as well LE at 40 years of age [ 21 ], at 60 [ 22 ], and at 65 [ 21 , 23 , 24 ]. In two papers, the age-specificity of life expectancy (be it at birth or another age) was not stated [ 25 , 26 ].

Some studies considered male and female LE separately [ 21 , 24 , 25 , 27 – 33 ]. This consideration was also often observed with the second most commonly used health index [ 28 – 30 , 34 – 38 ]–termed “total”, or “overall”, or “all-cause”, mortality rate (MR)–included in 22 of the 60 studies. In addition to gender, this index was also sometimes broken down according to age group [ 30 , 39 , 40 ], as well as gender-age group [ 38 ].

While the majority of studies under review here focused on a single health indicator, 23 out of the 60 studies made use of multiple outcomes, although these outcomes were always considered one at a time, and sometimes not all of them fell within the scope of our review. An easily discernable group of indices that typically went together [ 25 , 37 , 41 ] was that of neonatal (deaths occurring within 28 days postpartum), perinatal (fetal or early neonatal / first-7-days deaths), and post-neonatal (deaths between the 29 th day and completion of one year of life) mortality. More often than not, these indices were also accompanied by “stand-alone” indicators, such as infant mortality (deaths within the first year of life; our third most common index found in 16 of the 60 studies), maternal mortality (deaths during pregnancy or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy), and child mortality rates. Child mortality has conventionally been defined as mortality within the first 5 years of life, thus often also called “under-5 mortality”. Nonetheless, Pritchard & Wallace used the term “child mortality” to denote deaths of children younger than 14 years [ 42 ].

As previously stated, inclusion criteria did allow for self-reported health status to be used as a general measure of population health. Within our final selection of studies, seven utilized some form of subjective health as an outcome variable [ 25 , 43 – 48 ]. Additionally, the Health Human Development Index [ 49 ], healthy life expectancy [ 50 ], old-age survival [ 51 ], potential years of life lost [ 52 ], and disability-adjusted life expectancy [ 25 ] were also used.

We note that while in most cases the indicators mentioned above (and/or the covariates considered, see below) were taken in their absolute or logarithmic form, as a—typically annual—number, sometimes they were used in the form of differences, change rates, averages over a given time period, or even z-scores of rankings [ 19 , 22 , 40 , 42 , 44 , 53 – 57 ].

Regions, countries, and populations

Despite our decision to confine this review to high-income countries, some variation in the countries and regions studied was still present. Selection seemed to be most often conditioned on the European Union, or the European continent more generally, and the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), though, typically, not all member nations–based on the instances where these were also explicitly listed—were included in a given study. Some of the stated reasons for omitting certain nations included data unavailability [ 30 , 45 , 54 ] or inconsistency [ 20 , 58 ], Gross Domestic Product (GDP) too low [ 40 ], differences in economic development and political stability with the rest of the sampled countries [ 59 ], and national population too small [ 24 , 40 ]. On the other hand, the rationales for selecting a group of countries included having similar above-average infant mortality [ 60 ], similar healthcare systems [ 23 ], and being randomly drawn from a social spending category [ 61 ]. Some researchers were interested explicitly in a specific geographical region, such as Eastern Europe [ 50 ], Central and Eastern Europe [ 48 , 60 ], the Visegrad (V4) group [ 62 ], or the Asia/Pacific area [ 32 ]. In certain instances, national regions or cities, rather than countries, constituted the units of investigation instead [ 31 , 51 , 56 , 62 – 66 ]. In two particular cases, a mix of countries and cities was used [ 35 , 57 ]. In another two [ 28 , 29 ], due to the long time periods under study, some of the included countries no longer exist. Finally, besides “European” and “OECD”, the terms “developed”, “Western”, and “industrialized” were also used to describe the group of selected nations [ 30 , 42 , 52 , 53 , 67 ].

As stated above, it was the health status of the general population that we were interested in, and during screening we made a concerted effort to exclude research using data based on a more narrowly defined group of individuals. All studies included in this review adhere to this general rule, albeit with two caveats. First, as cities (even neighborhoods) were the unit of analysis in three of the studies that made the selection [ 56 , 64 , 65 ], the populations under investigation there can be more accurately described as general urban , instead of just general. Second, oftentimes health indicators were stratified based on gender and/or age, therefore we also admitted one study that, due to its specific research question, focused on men and women of early retirement age [ 35 ] and another that considered adult males only [ 68 ].

Data types and sources

A great diversity of sources was utilized for data collection purposes. The accessible reference databases of the OECD ( https://www.oecd.org/ ), WHO ( https://www.who.int/ ), World Bank ( https://www.worldbank.org/ ), United Nations ( https://www.un.org/en/ ), and Eurostat ( https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat ) were among the top choices. The other international databases included Human Mortality [ 30 , 39 , 50 ], Transparency International [ 40 , 48 , 50 ], Quality of Government [ 28 , 69 ], World Income Inequality [ 30 ], International Labor Organization [ 41 ], International Monetary Fund [ 70 ]. A number of national databases were referred to as well, for example the US Bureau of Statistics [ 42 , 53 ], Korean Statistical Information Services [ 67 ], Statistics Canada [ 67 ], Australian Bureau of Statistics [ 67 ], and Health New Zealand Tobacco control and Health New Zealand Food and Nutrition [ 19 ]. Well-known surveys, such as the World Values Survey [ 25 , 55 ], the European Social Survey [ 25 , 39 , 44 ], the Eurobarometer [ 46 , 56 ], the European Value Survey [ 25 ], and the European Statistics of Income and Living Condition Survey [ 43 , 47 , 70 ] were used as data sources, too. Finally, in some cases [ 25 , 28 , 29 , 35 , 36 , 41 , 69 ], built-for-purpose datasets from previous studies were re-used.

In most of the studies, the level of the data (and analysis) was national. The exceptions were six papers that dealt with Nomenclature of Territorial Units of Statistics (NUTS2) regions [ 31 , 62 , 63 , 66 ], otherwise defined areas [ 51 ] or cities [ 56 ], and seven others that were multilevel designs and utilized both country- and region-level data [ 57 ], individual- and city- or country-level [ 35 ], individual- and country-level [ 44 , 45 , 48 ], individual- and neighborhood-level [ 64 ], and city-region- (NUTS3) and country-level data [ 65 ]. Parallel to that, the data type was predominantly longitudinal, with only a few studies using purely cross-sectional data [ 25 , 33 , 43 , 45 – 48 , 50 , 62 , 67 , 68 , 71 , 72 ], albeit in four of those [ 43 , 48 , 68 , 72 ] two separate points in time were taken (thus resulting in a kind of “double cross-section”), while in another the averages across survey waves were used [ 56 ].

In studies using longitudinal data, the length of the covered time periods varied greatly. Although this was almost always less than 40 years, in one study it covered the entire 20 th century [ 29 ]. Longitudinal data, typically in the form of annual records, was sometimes transformed before usage. For example, some researchers considered data points at 5- [ 34 , 36 , 49 ] or 10-year [ 27 , 29 , 35 ] intervals instead of the traditional 1, or took averages over 3-year periods [ 42 , 53 , 73 ]. In one study concerned with the effect of the Great Recession all data were in a “recession minus expansion change in trends”-form [ 57 ]. Furthermore, there were a few instances where two different time periods were compared to each other [ 42 , 53 ] or when data was divided into 2 to 4 (possibly overlapping) periods which were then analyzed separately [ 24 , 26 , 28 , 29 , 31 , 65 ]. Lastly, owing to data availability issues, discrepancies between the time points or periods of data on the different variables were occasionally observed [ 22 , 35 , 42 , 53 – 55 , 63 ].

Health determinants

Together with other essential details, Table 1 lists the health correlates considered in the selected studies. Several general categories for these correlates can be discerned, including health care, political stability, socio-economics, demographics, psychology, environment, fertility, life-style, culture, labor. All of these, directly or implicitly, have been recognized as holding importance for population health by existing theoretical models of (social) determinants of health [ 74 – 77 ].

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239031.t001

It is worth noting that in a few studies there was just a single aggregate-level covariate investigated in relation to a health outcome of interest to us. In one instance, this was life satisfaction [ 44 ], in another–welfare system typology [ 45 ], but also gender inequality [ 33 ], austerity level [ 70 , 78 ], and deprivation [ 51 ]. Most often though, attention went exclusively to GDP [ 27 , 29 , 46 , 57 , 65 , 71 ]. It was often the case that research had a more particular focus. Among others, minimum wages [ 79 ], hospital payment schemes [ 23 ], cigarette prices [ 63 ], social expenditure [ 20 ], residents’ dissatisfaction [ 56 ], income inequality [ 30 , 69 ], and work leave [ 41 , 58 ] took center stage. Whenever variables outside of these specific areas were also included, they were usually identified as confounders or controls, moderators or mediators.

We visualized the combinations in which the different determinants have been studied in Fig 2 , which was obtained via multidimensional scaling and a subsequent cluster analysis (details outlined in S2 Appendix ). It depicts the spatial positioning of each determinant relative to all others, based on the number of times the effects of each pair of determinants have been studied simultaneously. When interpreting Fig 2 , one should keep in mind that determinants marked with an asterisk represent, in fact, collectives of variables.

Groups of determinants are marked by asterisks (see S1 Table in S1 Appendix ). Diminishing color intensity reflects a decrease in the total number of “connections” for a given determinant. Noteworthy pairwise “connections” are emphasized via lines (solid-dashed-dotted indicates decreasing frequency). Grey contour lines encircle groups of variables that were identified via cluster analysis. Abbreviations: age = population age distribution, associations = membership in associations, AT-index = atherogenic-thrombogenic index, BR = birth rate, CAPB = Cyclically Adjusted Primary Balance, civilian-labor = civilian labor force, C-section = Cesarean delivery rate, credit-info = depth of credit information, dissatisf = residents’ dissatisfaction, distrib.orient = distributional orientation, EDU = education, eHealth = eHealth index at GP-level, exch.rate = exchange rate, fat = fat consumption, GDP = gross domestic product, GFCF = Gross Fixed Capital Formation/Creation, GH-gas = greenhouse gas, GII = gender inequality index, gov = governance index, gov.revenue = government revenues, HC-coverage = healthcare coverage, HE = health(care) expenditure, HHconsump = household consumption, hosp.beds = hospital beds, hosp.payment = hospital payment scheme, hosp.stay = length of hospital stay, IDI = ICT development index, inc.ineq = income inequality, industry-labor = industrial labor force, infant-sex = infant sex ratio, labor-product = labor production, LBW = low birth weight, leave = work leave, life-satisf = life satisfaction, M-age = maternal age, marginal-tax = marginal tax rate, MDs = physicians, mult.preg = multiple pregnancy, NHS = Nation Health System, NO = nitrous oxide emissions, PM10 = particulate matter (PM10) emissions, pop = population size, pop.density = population density, pre-term = pre-term birth rate, prison = prison population, researchE = research&development expenditure, school.ref = compulsory schooling reform, smoke-free = smoke-free places, SO = sulfur oxide emissions, soc.E = social expenditure, soc.workers = social workers, sugar = sugar consumption, terror = terrorism, union = union density, UR = unemployment rate, urban = urbanization, veg-fr = vegetable-and-fruit consumption, welfare = welfare regime, Wwater = wastewater treatment.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239031.g002

Distances between determinants in Fig 2 are indicative of determinants’ “connectedness” with each other. While the statistical procedure called for higher dimensionality of the model, for demonstration purposes we show here a two-dimensional solution. This simplification unfortunately comes with a caveat. To use the factor smoking as an example, it would appear it stands at a much greater distance from GDP than it does from alcohol. In reality however, smoking was considered together with alcohol consumption [ 21 , 25 , 26 , 52 , 68 ] in just as many studies as it was with GDP [ 21 , 25 , 26 , 52 , 59 ], five. To aid with respect to this apparent shortcoming, we have emphasized the strongest pairwise links. Solid lines connect GDP with health expenditure (HE), unemployment rate (UR), and education (EDU), indicating that the effect of GDP on health, taking into account the effects of the other three determinants as well, was evaluated in between 12 to 16 studies of the 60 included in this review. Tracing the dashed lines, we can also tell that GDP appeared jointly with income inequality, and HE together with either EDU or UR, in anywhere between 8 to 10 of our selected studies. Finally, some weaker but still worth-mentioning “connections” between variables are displayed as well via the dotted lines.

The fact that all notable pairwise “connections” are concentrated within a relatively small region of the plot may be interpreted as low overall “connectedness” among the health indicators studied. GDP is the most widely investigated determinant in relation to general population health. Its total number of “connections” is disproportionately high (159) compared to its runner-up–HE (with 113 “connections”), and then subsequently EDU (with 90) and UR (with 86). In fact, all of these determinants could be thought of as outliers, given that none of the remaining factors have a total count of pairings above 52. This decrease in individual determinants’ overall “connectedness” can be tracked on the graph via the change of color intensity as we move outwards from the symbolic center of GDP and its closest “co-determinants”, to finally reach the other extreme of the ten indicators (welfare regime, household consumption, compulsory school reform, life satisfaction, government revenues, literacy, research expenditure, multiple pregnancy, Cyclically Adjusted Primary Balance, and residents’ dissatisfaction; in white) the effects on health of which were only studied in isolation.

Lastly, we point to the few small but stable clusters of covariates encircled by the grey bubbles on Fig 2 . These groups of determinants were identified as “close” by both statistical procedures used for the production of the graph (see details in S2 Appendix ).

Statistical methodology

There was great variation in the level of statistical detail reported. Some authors provided too vague a description of their analytical approach, necessitating some inference in this section.

The issue of missing data is a challenging reality in this field of research, but few of the studies under review (12/60) explain how they dealt with it. Among the ones that do, three general approaches to handling missingness can be identified, listed in increasing level of sophistication: case-wise deletion, i.e., removal of countries from the sample [ 20 , 45 , 48 , 58 , 59 ], (linear) interpolation [ 28 , 30 , 34 , 58 , 59 , 63 ], and multiple imputation [ 26 , 41 , 52 ].

Correlations, Pearson, Spearman, or unspecified, were the only technique applied with respect to the health outcomes of interest in eight analyses [ 33 , 42 – 44 , 46 , 53 , 57 , 61 ]. Among the more advanced statistical methods, the family of regression models proved to be, by and large, predominant. Before examining this closer, we note the techniques that were, in a way, “unique” within this selection of studies: meta-analyses were performed (random and fixed effects, respectively) on the reduced form and 2-sample two stage least squares (2SLS) estimations done within countries [ 39 ]; difference-in-difference (DiD) analysis was applied in one case [ 23 ]; dynamic time-series methods, among which co-integration, impulse-response function (IRF), and panel vector autoregressive (VAR) modeling, were utilized in one study [ 80 ]; longitudinal generalized estimating equation (GEE) models were developed on two occasions [ 70 , 78 ]; hierarchical Bayesian spatial models [ 51 ] and special autoregressive regression [ 62 ] were also implemented.

Purely cross-sectional data analyses were performed in eight studies [ 25 , 45 , 47 , 50 , 55 , 56 , 67 , 71 ]. These consisted of linear regression (assumed ordinary least squares (OLS)), generalized least squares (GLS) regression, and multilevel analyses. However, six other studies that used longitudinal data in fact had a cross-sectional design, through which they applied regression at multiple time-points separately [ 27 , 29 , 36 , 48 , 68 , 72 ].

Apart from these “multi-point cross-sectional studies”, some other simplistic approaches to longitudinal data analysis were found, involving calculating and regressing 3-year averages of both the response and the predictor variables [ 54 ], taking the average of a few data-points (i.e., survey waves) [ 56 ] or using difference scores over 10-year [ 19 , 29 ] or unspecified time intervals [ 40 , 55 ].

Moving further in the direction of more sensible longitudinal data usage, we turn to the methods widely known among (health) economists as “panel data analysis” or “panel regression”. Most often seen were models with fixed effects for country/region and sometimes also time-point (occasionally including a country-specific trend as well), with robust standard errors for the parameter estimates to take into account correlations among clustered observations [ 20 , 21 , 24 , 28 , 30 , 32 , 34 , 37 , 38 , 41 , 52 , 59 , 60 , 63 , 66 , 69 , 73 , 79 , 81 , 82 ]. The Hausman test [ 83 ] was sometimes mentioned as the tool used to decide between fixed and random effects [ 26 , 49 , 63 , 66 , 73 , 82 ]. A few studies considered the latter more appropriate for their particular analyses, with some further specifying that (feasible) GLS estimation was employed [ 26 , 34 , 49 , 58 , 60 , 73 ]. Apart from these two types of models, the first differences method was encountered once as well [ 31 ]. Across all, the error terms were sometimes assumed to come from a first-order autoregressive process (AR(1)), i.e., they were allowed to be serially correlated [ 20 , 30 , 38 , 58 – 60 , 73 ], and lags of (typically) predictor variables were included in the model specification, too [ 20 , 21 , 37 , 38 , 48 , 69 , 81 ]. Lastly, a somewhat different approach to longitudinal data analysis was undertaken in four studies [ 22 , 35 , 48 , 65 ] in which multilevel–linear or Poisson–models were developed.

Regardless of the exact techniques used, most studies included in this review presented multiple model applications within their main analysis. None attempted to formally compare models in order to identify the “best”, even if goodness-of-fit statistics were occasionally reported. As indicated above, many studies investigated women’s and men’s health separately [ 19 , 21 , 22 , 27 – 29 , 31 , 33 , 35 , 36 , 38 , 39 , 45 , 50 , 51 , 64 , 65 , 69 , 82 ], and covariates were often tested one at a time, including other covariates only incrementally [ 20 , 25 , 28 , 36 , 40 , 50 , 55 , 67 , 73 ]. Furthermore, there were a few instances where analyses within countries were performed as well [ 32 , 39 , 51 ] or where the full time period of interest was divided into a few sub-periods [ 24 , 26 , 28 , 31 ]. There were also cases where different statistical techniques were applied in parallel [ 29 , 55 , 60 , 66 , 69 , 73 , 82 ], sometimes as a form of sensitivity analysis [ 24 , 26 , 30 , 58 , 73 ]. However, the most common approach to sensitivity analysis was to re-run models with somewhat different samples [ 39 , 50 , 59 , 67 , 69 , 80 , 82 ]. Other strategies included different categorization of variables or adding (more/other) controls [ 21 , 23 , 25 , 28 , 37 , 50 , 63 , 69 ], using an alternative main covariate measure [ 59 , 82 ], including lags for predictors or outcomes [ 28 , 30 , 58 , 63 , 65 , 79 ], using weights [ 24 , 67 ] or alternative data sources [ 37 , 69 ], or using non-imputed data [ 41 ].

As the methods and not the findings are the main focus of the current review, and because generic checklists cannot discern the underlying quality in this application field (see also below), we opted to pool all reported findings together, regardless of individual study characteristics or particular outcome(s) used, and speak generally of positive and negative effects on health. For this summary we have adopted the 0.05-significance level and only considered results from multivariate analyses. Strictly birth-related factors are omitted since these potentially only relate to the group of infant mortality indicators and not to any of the other general population health measures.

Starting with the determinants most often studied, higher GDP levels [ 21 , 26 , 27 , 29 , 30 , 32 , 43 , 48 , 52 , 58 , 60 , 66 , 67 , 73 , 79 , 81 , 82 ], higher health [ 21 , 37 , 47 , 49 , 52 , 58 , 59 , 68 , 72 , 82 ] and social [ 20 , 21 , 26 , 38 , 79 ] expenditures, higher education [ 26 , 39 , 52 , 62 , 72 , 73 ], lower unemployment [ 60 , 61 , 66 ], and lower income inequality [ 30 , 42 , 53 , 55 , 73 ] were found to be significantly associated with better population health on a number of occasions. In addition to that, there was also some evidence that democracy [ 36 ] and freedom [ 50 ], higher work compensation [ 43 , 79 ], distributional orientation [ 54 ], cigarette prices [ 63 ], gross national income [ 22 , 72 ], labor productivity [ 26 ], exchange rates [ 32 ], marginal tax rates [ 79 ], vaccination rates [ 52 ], total fertility [ 59 , 66 ], fruit and vegetable [ 68 ], fat [ 52 ] and sugar consumption [ 52 ], as well as bigger depth of credit information [ 22 ] and percentage of civilian labor force [ 79 ], longer work leaves [ 41 , 58 ], more physicians [ 37 , 52 , 72 ], nurses [ 72 ], and hospital beds [ 79 , 82 ], and also membership in associations, perceived corruption and societal trust [ 48 ] were beneficial to health. Higher nitrous oxide (NO) levels [ 52 ], longer average hospital stay [ 48 ], deprivation [ 51 ], dissatisfaction with healthcare and the social environment [ 56 ], corruption [ 40 , 50 ], smoking [ 19 , 26 , 52 , 68 ], alcohol consumption [ 26 , 52 , 68 ] and illegal drug use [ 68 ], poverty [ 64 ], higher percentage of industrial workers [ 26 ], Gross Fixed Capital creation [ 66 ] and older population [ 38 , 66 , 79 ], gender inequality [ 22 ], and fertility [ 26 , 66 ] were detrimental.

It is important to point out that the above-mentioned effects could not be considered stable either across or within studies. Very often, statistical significance of a given covariate fluctuated between the different model specifications tried out within the same study [ 20 , 49 , 59 , 66 , 68 , 69 , 73 , 80 , 82 ], testifying to the importance of control variables and multivariate research (i.e., analyzing multiple independent variables simultaneously) in general. Furthermore, conflicting results were observed even with regards to the “core” determinants given special attention, so to speak, throughout this text. Thus, some studies reported negative effects of health expenditure [ 32 , 82 ], social expenditure [ 58 ], GDP [ 49 , 66 ], and education [ 82 ], and positive effects of income inequality [ 82 ] and unemployment [ 24 , 31 , 32 , 52 , 66 , 68 ]. Interestingly, one study [ 34 ] differentiated between temporary and long-term effects of GDP and unemployment, alluding to possibly much greater complexity of the association with health. It is also worth noting that some gender differences were found, with determinants being more influential for males than for females, or only having statistically significant effects for male health [ 19 , 21 , 28 , 34 , 36 , 37 , 39 , 64 , 65 , 69 ].

The purpose of this scoping review was to examine recent quantitative work on the topic of multi-country analyses of determinants of population health in high-income countries.

Measuring population health via relatively simple mortality-based indicators still seems to be the state of the art. What is more, these indicators are routinely considered one at a time, instead of, for example, employing existing statistical procedures to devise a more general, composite, index of population health, or using some of the established indices, such as disability-adjusted life expectancy (DALE) or quality-adjusted life expectancy (QALE). Although strong arguments for their wider use were already voiced decades ago [ 84 ], such summary measures surface only rarely in this research field.

On a related note, the greater data availability and accessibility that we enjoy today does not automatically equate to data quality. Nonetheless, this is routinely assumed in aggregate level studies. We almost never encountered a discussion on the topic. The non-mundane issue of data missingness, too, goes largely underappreciated. With all recent methodological advancements in this area [ 85 – 88 ], there is no excuse for ignorance; and still, too few of the reviewed studies tackled the matter in any adequate fashion.

Much optimism can be gained considering the abundance of different determinants that have attracted researchers’ attention in relation to population health. We took on a visual approach with regards to these determinants and presented a graph that links spatial distances between determinants with frequencies of being studies together. To facilitate interpretation, we grouped some variables, which resulted in some loss of finer detail. Nevertheless, the graph is helpful in exemplifying how many effects continue to be studied in a very limited context, if any. Since in reality no factor acts in isolation, this oversimplification practice threatens to render the whole exercise meaningless from the outset. The importance of multivariate analysis cannot be stressed enough. While there is no “best method” to be recommended and appropriate techniques vary according to the specifics of the research question and the characteristics of the data at hand [ 89 – 93 ], in the future, in addition to abandoning simplistic univariate approaches, we hope to see a shift from the currently dominating fixed effects to the more flexible random/mixed effects models [ 94 ], as well as wider application of more sophisticated methods, such as principle component regression, partial least squares, covariance structure models (e.g., structural equations), canonical correlations, time-series, and generalized estimating equations.

Finally, there are some limitations of the current scoping review. We searched the two main databases for published research in medical and non-medical sciences (PubMed and Web of Science) since 2013, thus potentially excluding publications and reports that are not indexed in these databases, as well as older indexed publications. These choices were guided by our interest in the most recent (i.e., the current state-of-the-art) and arguably the highest-quality research (i.e., peer-reviewed articles, primarily in indexed non-predatory journals). Furthermore, despite holding a critical stance with regards to some aspects of how determinants-of-health research is currently conducted, we opted out of formally assessing the quality of the individual studies included. The reason for that is two-fold. On the one hand, we are unaware of the existence of a formal and standard tool for quality assessment of ecological designs. And on the other, we consider trying to score the quality of these diverse studies (in terms of regional setting, specific topic, outcome indices, and methodology) undesirable and misleading, particularly since we would sometimes have been rating the quality of only a (small) part of the original studies—the part that was relevant to our review’s goal.

Our aim was to investigate the current state of research on the very broad and general topic of population health, specifically, the way it has been examined in a multi-country context. We learned that data treatment and analytical approach were, in the majority of these recent studies, ill-equipped or insufficiently transparent to provide clarity regarding the underlying mechanisms of population health in high-income countries. Whether due to methodological shortcomings or the inherent complexity of the topic, research so far fails to provide any definitive answers. It is our sincere belief that with the application of more advanced analytical techniques this continuous quest could come to fruition sooner.

Supporting information

S1 checklist. preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses extension for scoping reviews (prisma-scr) checklist..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239031.s001

S1 Appendix.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239031.s002

S2 Appendix.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239031.s003

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- PubMed/NCBI

- 75. Dahlgren G, Whitehead M. Policies and Strategies to Promote Equity in Health. Stockholm, Sweden: Institute for Future Studies; 1991.

- 76. Brunner E, Marmot M. Social Organization, Stress, and Health. In: Marmot M, Wilkinson RG, editors. Social Determinants of Health. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 1999.

- 77. Najman JM. A General Model of the Social Origins of Health and Well-being. In: Eckersley R, Dixon J, Douglas B, editors. The Social Origins of Health and Well-being. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 2001.

- 85. Carpenter JR, Kenward MG. Multiple Imputation and its Application. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2013.

- 86. Molenberghs G, Fitzmaurice G, Kenward MG, Verbeke G, Tsiatis AA. Handbook of Missing Data Methodology. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2014.

- 87. van Buuren S. Flexible Imputation of Missing Data. 2nd ed. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2018.

- 88. Enders CK. Applied Missing Data Analysis. New York: Guilford; 2010.

- 89. Shayle R. Searle GC, Charles E. McCulloch. Variance Components: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1992.

- 90. Agresti A. Foundations of Linear and Generalized Linear Models. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons Inc.; 2015.

- 91. Leyland A. H. (Editor) HGE. Multilevel Modelling of Health Statistics: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2001.

- 92. Garrett Fitzmaurice MD, Geert Verbeke, Geert Molenberghs. Longitudinal Data Analysis. New York: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2008.

- 93. Wolfgang Karl Härdle LS. Applied Multivariate Statistical Analysis. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2015.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 06 January 2021

Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical students: a multicenter quantitative study

- Aaron J. Harries ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7107-0995 1 ,

- Carmen Lee 1 ,

- Lee Jones 2 ,

- Robert M. Rodriguez 1 ,

- John A. Davis 2 ,

- Megan Boysen-Osborn 3 ,

- Kathleen J. Kashima 4 ,

- N. Kevin Krane 5 ,

- Guenevere Rae 6 ,

- Nicholas Kman 7 ,

- Jodi M. Langsfeld 8 &

- Marianne Juarez 1

BMC Medical Education volume 21 , Article number: 14 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

135k Accesses

149 Citations

37 Altmetric

Metrics details

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the United States (US) medical education system with the necessary, yet unprecedented Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) national recommendation to pause all student clinical rotations with in-person patient care. This study is a quantitative analysis investigating the educational and psychological effects of the pandemic on US medical students and their reactions to the AAMC recommendation in order to inform medical education policy.

The authors sent a cross-sectional survey via email to medical students in their clinical training years at six medical schools during the initial peak phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Survey questions aimed to evaluate students’ perceptions of COVID-19’s impact on medical education; ethical obligations during a pandemic; infection risk; anxiety and burnout; willingness and needed preparations to return to clinical rotations.

Seven hundred forty-one (29.5%) students responded. Nearly all students (93.7%) were not involved in clinical rotations with in-person patient contact at the time the study was conducted. Reactions to being removed were mixed, with 75.8% feeling this was appropriate, 34.7% guilty, 33.5% disappointed, and 27.0% relieved.

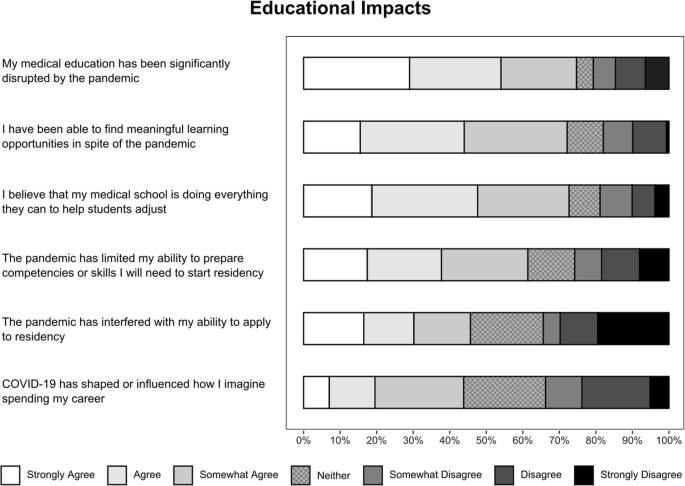

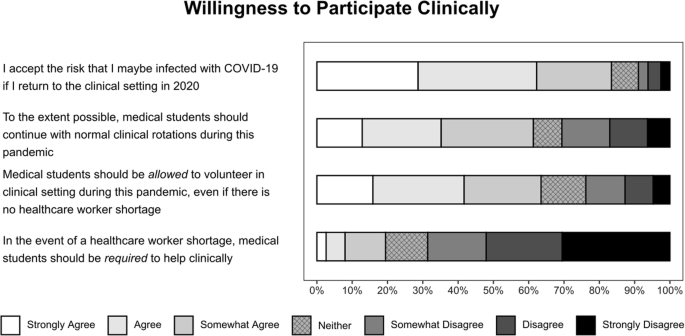

Most students (74.7%) agreed the pandemic had significantly disrupted their medical education, and believed they should continue with normal clinical rotations during this pandemic (61.3%). When asked if they would accept the risk of infection with COVID-19 if they returned to the clinical setting, 83.4% agreed.