Skip to content

Support the College of Dental Medicine

Community outreach.

Learn more about the College of Dental Medicine's community outreach programs.

Postdoctoral and Residency Programs

dds program.

Half of our graduates go directly into specialty training upon completion of the DDS degree.

Research Areas

Patient care, columbiadoctors dentistry, become a student.

Learn more about the admissions process and how you can apply.

Student Research Projects

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 01 March 2019

Research dental hygienist - whoever knew there was such a role?

- Rachael England 1

BDJ Team volume 6 , pages 21–23 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

1779 Accesses

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

You have full access to this article via your institution.

After spotting a job advertisement for a research dental hygienist, Rachael England soon found herself in the job and out on the road .

After 13 years of working clinically, I was feeling the need for a new role outside the surgery and with a Master's in Public Health under my belt, I was particularly interested in academia. When I saw a role advertised for 'research dental hygienist' at University College London, the timing couldn't have been better.

I was joining the British Regional Heart Study (BRHS) as a member of the field team. This longitudinal study began in 1978 to understand why high numbers of men were dying prematurely. Around 7,500 men aged 40-60 were recruited via their local GP surgeries. Over the following 40 years the men have undergone several health screenings, activity monitoring, completed annual questionnaires and every two years the office team liaise with their GP surgeries to check for serious health events. At the outset, the team looked at hard water, cardiovascular disease and socioeconomic factors in 24 towns around the UK. The men are now aged 77-97, making it one of the longest running cohort studies in the UK.

In 2012, Dr. Sheena Ramsay joined the research team as Principal Investigator. Her early career as a dentist meant the study developed a more dental theme. As we know, the effects of oral-systemic disease are significant with this age group who may suffer from chronic diseases such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Also in this cohort, we could examine the self-reported diet sheets and carry out frailty assessments and dental health checks to see any associations between the remaining dentition and how 'well' the men are now.

The health screenings were to examine the remaining 1,400 men who are well enough to attend the mobile clinic in the town where they were originally recruited (see figure 1 ). The field team comprised a nurse, a phlebotomist and a dental hygienist (me). In addition to a dental examination, the men would have the following recorded:

blood pressure,

arm, calf and waist circumference

frailty measurements (ie grip strength)

walking speed

time of standing to sitting

lung function.

The participants would also complete a memory test while they waited. The office-based team would find premises suitable for the mobile clinic, contact the participants, send reminders, deal with all administration and book hotels for the field team to stay in.

The first two weeks were spent at University College London training and organising the equipment and, most importantly, developing the study protocol and calibrating the dental measurements. Working with Dr. Ramsay, I developed a coded dental chart that would record:

pocket depth

loss of attachment

number of teeth

functional pairs of dentition,

xerostomia score

any other pathology.

I was also responsible for carrying out the lung function assessment using a Vitalograph machine. This is used to assess how well your lungs work by measuring how much air you inhale and how much and how quickly you exhale. The data it delivers - spirometry - diagnoses asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and other conditions that affect breathing. This is especially appropriate among older people who may have been exposed to damaging substances in their earlier lives. The research manager thought the Vitalograph would fit well with the dental station and I only needed a day of training to get to grips with.

As health professionals we all have heard about the North/South divide and have discussed determinants of health during our training. Yet to see it so starkly, in real life, in front of my eyes was staggering.

Despite it being a relatively simple piece of equipment, the training didn't prepare me for the challenge of instructing patients who have experienced cognitive decline. Thankfully, the patient management skills I had learned through being a dental hygienist helped me through.

We then carried out a pilot study. Our statistician belongs to a church in North London and very kindly recruited members of the congregation. This allowed us to tweak the dental protocol, making it easier to record and ensure the whole set up worked smoothly with the right equipment. After a small electrical fire and an urgently purchased new Vitalograph, we were ready to head to the first town!

©RapidEye/E+/Getty Images Plus

Anxiously heading out of London to Bedford we navigated together. The first venue was a community centre, where we set up the mobile clinic in a conference room. Early the next morning the men started arriving.

Each day we had capacity to see 20 men. However, the number who came in varied greatly. Bedford proved to be quite busy, with fit, well and active men aged 80+, mostly still with the majority of their own dentition - albeit heavily restored. After three days we returned to London for a debrief. These sessions allowed us to deal with any challenges, make some input to the next stage and chat about the results.

Next, we headed off for two weeks in Scotland and the North-West. Dunfermline, Falkirk, Ayr and Carlisle. Far fewer participants attended and they were much frailer and mostly had broken or missing teeth or faded, plastic dentures.

As health professionals we have all heard about the North/South divide and have discussed determinants of health during our training. Yet, to see it so starkly, in real life, in front of my eyes was staggering.

Every town holds its own unique history that has shaped the health of these men and their rate of decline into old age. Taking a walk around in an evening I could observe the ghosts of past industry, Burnley's now converted cotton mills and the traces of a mining history, Scunthorpe's steel mills, Lowestoft's deep-sea fishing and Hartlepool, once a thriving port with ship building and steel making industries. With the decimation of the North-East's industrial age, 10,000 jobs were lost, leaving a town the hallmarks of endemic deprivation - substance abuse, urban decay, crime and twice the national average rate of unemployment.

One participant told me 'you'll never get rich working with your back', a testament to the tough, working lives these men have led. Despite this, I have never spent such precious time with people before, older participants who had served in World War II as well as those slightly younger who regaled us with stories of their National Service. We laughed with them over crazy adventures and cried with them when they described the passing of their beloved wives.

What really struck me was the poor state of dental health in every town - except (perhaps predictably), Guildford, Bedford and Southport. Nothing could prepare me for seeing such terrible neglect in so many men, I kept asking myself - how does this happen? How have we reached a state where our elderly are somehow managing without a functional dentition?

Some of the participants shared their barriers to treatment, such as a lack of:

time - due to being the primary carer for their spouse

availability of NHS access

commitment to caring for themselves.

Many were just happy to maintain the status-quo and have regular check-ups and what we probably consider to be palliative dentistry. Is this acceptable with our current knowledge of the oral-systemic link and frailty in old age related to an ability to eat nutritious food?

Taking a walk around in an evening I could observe the ghosts of past industry, Burnley's now converted cotton mills and the traces of a mining history, Scunthorpe's steel mills, Lowestoft's deep-sea fishing, Hartlepool - once a thriving port with ship building and steel making industries.

We need to improve awareness in this age group that their oral health affects their general health and how important it is to see a dental professional regularly.

The role is intense as you see a participant every 10-15 minutes on a busy day. Ergonomics are pretty much out of the window as you lean over a masseuse bed to complete the examination.

Moving between towns was our greatest challenge, packing the equipment back into the van, driving several hundred miles, finding a new location and setting the clinic back up. The facilities varied from doctors' surgeries and church halls to community centres and conference halls. Being greeted with a friendly smile and a cup of tea was the reassurance we needed the session would run smoothly.

©Mark Waugh / Alamy Stock Photo

After 6 months the data collection was complete. It has been sent for entry and processing which takes up to 12 months before the research teams can begin analysis of the findings.

As a career option this role was a refreshing change from working in a clinic, without being too dissimilar.

Although dental hygienists can get involved with research through epidemiological data collection, I would really encourage dental therapists and dental hygienists to look into the role of Research Dental Hygienist. For me, it is wonderful to be a part of such a historic study that has made an impact on so many lives.

It is both fascinating and disturbing to witness first-hand the inequities in health the population suffer and how the determinants of health shape our lives. Our elderly population have amazing lives to share; we should all take the time to listen.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

FDI, Geneva, Schweiz

Rachael England

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Rachael England .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

England, R. Research dental hygienist - whoever knew there was such a role?. BDJ Team 6 , 21–23 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41407-019-0004-y

Download citation

Published : 01 March 2019

Issue Date : March 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41407-019-0004-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

121+ Interesting Dental Research Topics for Undergraduates

Did you know poor oral health can be linked to heart disease? It’s true! This surprising fact underscores the importance of dental research in maintaining overall health and well-being.

Understanding the intricate connections between oral health and systemic conditions like heart disease highlights the critical role of research in advancing our knowledge and improving patient outcomes.

In this blog, we will delve into various dental research topics tailored specifically for undergraduates, providing insights, resources, and inspiration to explore this fascinating field further.

Whether you’re passionate about dentistry or simply curious about the intersection of oral health and overall wellness, join us as we uncover the exciting possibilities in dental research for undergraduates.

What is Dental Research Topic?

Table of Contents

A dental research topic is a subject of study within the field of dentistry that aims to explore, investigate, and analyze various aspects related to oral health, dental care, and dental treatments.

These topics cover a wide range of areas, including but not limited to dental diseases, preventive measures, treatment methods, oral hygiene practices, dental technology advancements, and the impact of oral health on overall well-being.

Dental research topics provide opportunities for scholars, researchers, and students to contribute to the advancement of dental science, improve patient care, and address current challenges in oral health care.

Importance of Dental Research Topics for Undergraduates

Dental research topics are essential for undergraduates for several reasons:

Skill Development

Engaging in dental research topics helps undergraduates develop critical thinking, problem-solving, and analytical skills essential for their academic and professional growth.

Contribution to Knowledge

Undertaking research allows undergraduates to contribute to the existing body of knowledge in dentistry, advancing the field and addressing emerging challenges.

Career Preparation

Research experience enhances students’ competitiveness for dental school admissions, graduate programs, and future careers in academia, clinical practice, or research institutions.

Practical Application

Research topics offer undergraduates the opportunity to apply theoretical knowledge gained in the classroom to real-world scenarios, fostering a deeper understanding of dental concepts and techniques.

Professional Networking

Engaging in research exposes undergraduates to collaboration with peers, faculty, and professionals, facilitating valuable networking opportunities within the dental community.

Popular Dental Research Topics for Undergraduates

Dental research topics for undergraduates encompass a wide range of areas within dentistry. Here are some examples across different subfields:

Dental Diseases

- The role of genetics in the development of periodontal disease.

- Strategies for early detection and prevention of dental caries.

- Investigating the link between diabetes and periodontal disease.

- Factors influencing the prevalence of oral cancer among different demographics.

- Impact of dietary habits on the occurrence of enamel erosion.

- Effectiveness of fluoride in preventing dental decay.

- The role of saliva in maintaining oral health and preventing diseases.

- Trends in the prevalence of temporomandibular joint disorders.

- Oral manifestations of systemic diseases: A comprehensive review.

- Investigating the relationship between oral health and overall systemic health.

- The effectiveness of probiotics in preventing oral infections.

- Psychological factors influencing dental anxiety and its management.

Dental Treatments

- Comparison of different types of dental implants: Materials, techniques, and success rates.

- Advancements in minimally invasive techniques for dental restoration.

- Comparative analysis of traditional braces versus clear aligners in orthodontic treatment.

- The role of lasers in various dental procedures: Benefits and limitations.

- Innovations in endodontic treatment: From rotary instruments to regenerative techniques.

- Efficacy of different whitening agents in professional and over-the-counter dental bleaching.

- The impact of COVID-19 on dental practice: Adaptations, challenges, and future implications.

- Investigating the use of stem cells in dental tissue regeneration.

- Comparative study of different materials used in dental restorations: Strength, durability, and aesthetics.

- Exploring the potential of 3D printing technology in prosthodontics and oral surgery.

- Patient satisfaction and outcomes following different types of orthognathic surgeries.

- Long-term success rates of various techniques in root canal therapy.

Oral Health Promotion and Education

- Effectiveness of school-based oral health education programs in improving children’s oral hygiene.

- Strategies for promoting oral health in underserved communities: Challenges and solutions.

- Role of social media and technology in disseminating oral health information.

- Impact of community water fluoridation on dental caries prevention.

- The role of parents and caregivers in establishing children’s oral hygiene habits.

- Cultural influences on oral health beliefs and practices: Implications for public health campaigns.

- Effectiveness of motivational interviewing in promoting behavior change for better oral health.

- Investigating the efficacy of school-based dental sealant programs.

- Oral health literacy among different populations: Assessments and interventions.

- The role of dentists in advocating for policies promoting oral health equity.

- Strategies for improving oral health outcomes among elderly populations.

- Integrating oral health education into primary care settings: Opportunities and challenges.

Dental Materials and Biomaterials

- Biocompatibility of dental materials: Assessing safety and long-term effects.

- Development of antimicrobial dental materials to prevent biofilm formation.

- Investigating the mechanical properties of novel dental composites.

- Bioactive materials in dentistry: Applications and clinical implications.

- Biodegradable materials for temporary dental restorations.

- Nanotechnology in dentistry: Potential applications and future directions.

- Development of remineralizing agents for the management of dental caries.

- Investigating the properties and applications of dental ceramics.

- Biomimetic materials in dentistry: Mimicking natural tooth structure for improved outcomes.

- Sustainable practices in dental material manufacturing and disposal.

- Advances in adhesive systems for bonding dental restorations.

- Biomechanical properties of dental implant materials: Enhancing stability and osseointegration.

Oral Microbiology and Immunology

- Microbiome of the oral cavity: Composition, dynamics, and role in health and disease.

- Host-pathogen interactions in periodontal diseases: Insights into disease progression.

- Immunological responses to dental biofilms and their implications for treatment.

- Role of probiotics in modulating oral microbiota and preventing dental diseases.

- Viral infections in dentistry: From herpesviruses to SARS-CoV-2.

- Impact of antimicrobial resistance on dental infections and treatment outcomes.

- Microbial ecology of dental plaques in different oral environments.

- Oral manifestations of HIV/AIDS: Diagnosis, management, and implications.

- Biofilm formation on dental implant surfaces: Prevention and management strategies.

- Innate and adaptive immune responses in oral mucosal diseases.

- Virulence factors of oral pathogens and their role in disease progression.

- Immunomodulatory properties of dental materials and their impact on tissue response.

Dental Public Health

- Epidemiology of dental diseases: Trends, disparities, and risk factors.

- Health promotion strategies for improving access to dental care in rural areas.

- Oral health inequalities among different socioeconomic groups: Causes and solutions.

- Cost-effectiveness of preventive dental interventions: A systematic review.

- Integrating oral health into primary care: Models of collaborative practice.

- Tele-dentistry: Opportunities and challenges for improving access to dental care.

- Oral health surveillance systems: Monitoring trends and assessing needs.

- Assessing the effectiveness of community water fluoridation programs.

- Role of dental professionals in addressing oral health disparities.

- Impact of environmental factors on oral health outcomes: Pollution, climate change, and urbanization.

- Dental workforce issues: Distribution, shortages, and workforce diversity.

- Oral health policies and advocacy: Strategies for promoting legislative change.

Pediatric Dentistry

- Early childhood caries: Risk factors, prevention, and management strategies.

- Behavior management techniques in pediatric dentistry: Evidence-based approaches.

- Oral health outcomes of children with special healthcare needs: Challenges and interventions.

- Dental trauma in children: Prevention, diagnosis, and treatment.

- Assessment of dental fear and anxiety in pediatric patients: Tools and interventions.

- Maternal and child oral health: Prenatal factors influencing dental health outcomes.

- Dental developmental anomalies: Diagnosis, management, and long-term implications.

- Effectiveness of fluoride varnish application in preventing dental caries in children.

- Impact of nutrition and dietary habits on pediatric oral health.

- Pediatric sedation techniques in dentistry: Safety, efficacy, and guidelines.

- Orthodontic considerations in pediatric dentistry: Early intervention and treatment planning.

- Pediatric dental emergencies: Management and prevention strategies.

Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Outcomes of orthognathic surgery in patients with skeletal discrepancies.

- Management of impacted third molars: Indications, techniques, and complications.

- Reconstruction of maxillofacial defects following trauma or tumor resection: Surgical options and outcomes.

- Temporomandibular joint disorders: Diagnosis, management, and surgical interventions.

- Bone grafting techniques in implant dentistry: Approaches and success rates.

- Surgical management of obstructive sleep apnea: Role of maxillomandibular advancement.

- Surgical treatment options for cleft lip and palate: Multidisciplinary approaches and long-term outcomes.

- Surgical management of oral and maxillofacial infections: Antibiotic therapy, drainage, and debridement.

- Soft tissue augmentation techniques in aesthetic and functional maxillofacial surgery.

- Advancements in minimally invasive techniques for orthognathic surgery.

- Surgical management of facial trauma: Emergency interventions and long-term rehabilitation.

- Digital planning and navigation in oral and maxillofacial surgery: Enhancing precision and outcomes.

Dental Education and Training

- Effectiveness of simulation-based training in dental education: Skill acquisition and retention.

- Integration of digital technology into dental curricula: Challenges and opportunities.

- Peer-assisted learning in dental education: Impact on student performance and satisfaction.

- Interprofessional education in dentistry: Collaborative approaches to patient care.

- Continuing education requirements for dental professionals: Trends and implications.

- Assessment methods in dental education: Moving beyond traditional exams.

- The role of mentorship in shaping the career trajectories of dental students.

- Global perspectives in dental education: Cross-cultural experiences and challenges.

- Incorporating evidence-based practice into dental curricula: Strategies and outcomes.

- Tele-education in dentistry: Remote learning platforms and their effectiveness.

- Student perceptions of clinical experiences in dental education: Barriers and facilitators.

- Innovations in competency-based dental education: Assessing clinical proficiency and readiness for practice.

Dental Technology and Innovation

- Artificial intelligence in dentistry: Applications in diagnosis, treatment planning, and outcomes prediction.

- Virtual reality and augmented reality in dental education and patient care.

- Robotics in dentistry: Automation of procedures and precision in surgical interventions.

- Wearable technology for monitoring oral health behaviors and conditions.

- 3D printing in dentistry: Customization of dental implants, prostheses, and surgical guides.

- Digital smile design: Utilizing technology for aesthetic treatment planning and communication.

- Smart materials in dentistry: Self-healing, self-cleaning, and bioactive properties.

- Teledentistry platforms for remote consultations, monitoring, and patient education.

- Biomimetic approaches in dental materials design: Mimicking natural tooth structure and function.

- Nanomaterials in oral healthcare products: Enhanced delivery systems and therapeutic applications.

- Bioprinting of dental tissues and organs: Advancements in regenerative dentistry.

- Energy-based devices in dentistry: Laser therapy, photobiomodulation, and electrosurgery applications.

- Development of a Smart Toothbrush with Artificial Intelligence Integration.

These topics offer a comprehensive overview of the diverse areas within the field of dental research and provide undergraduates with a plethora of options for exploring their interests and making meaningful contributions to the discipline.

Current Trends in Dental Research

Several trends were prevalent in dental research. While there may have been further developments since then, here are some prominent trends at that time:

Biomimetic Dentistry

Mimicking natural tooth structure and function using advanced materials and techniques.

Tele-dentistry

Utilizing technology for remote consultations, monitoring, and patient education, especially amidst the COVID-19 pandemic.

Regenerative Dentistry

Developing therapies to regenerate dental tissues and promote natural healing processes.

Personalized Dentistry

Tailoring treatment plans based on individual patient characteristics, genetics, and preferences.

Minimally Invasive Dentistry

Emphasizing conservative approaches to preserve tooth structure and improve patient comfort.

Digital Dentistry

Integration of digital technology for diagnostics, treatment planning, and fabrication of dental restorations.

Nanotechnology

Utilizing nanomaterials for improved dental materials, drug delivery systems, and diagnostic tools.

Challenges in Dental Research Topics

Dental research, like any scientific field, faces its share of challenges. These challenges can span various aspects of the research process, from funding and resources to methodological complexities and ethical considerations. Here are some common challenges in dental research:

Funding Constraints

Limited financial resources hinder the initiation and continuation of dental research projects.

Access to Resources

Inadequate access to specialized equipment, materials, and facilities poses a barrier to conducting comprehensive research.

Recruitment of Participants

Difficulty in recruiting diverse and representative study populations affects the generalizability of research findings.

Ethical Considerations

Navigating ethical complexities, such as informed consent and privacy concerns, adds challenges to dental research.

Interdisciplinary Collaboration

Facilitating collaboration between dental professionals, researchers, and other disciplines is essential but often challenging.

Translation of Research into Practice

Bridging the gap between research findings and clinical implementation remains a significant challenge in dental research.

The exploration of dental research topics holds immense promise for advancing oral health care and addressing multifaceted challenges within the field.

From unraveling the mysteries of oral diseases to pioneering innovative treatments and technologies, dental research serves as the cornerstone of progress and improvement in patient outcomes.

Despite facing various challenges such as funding constraints and ethical considerations, the pursuit of dental research remains crucial for enhancing preventive measures, refining treatment modalities, and promoting overall well-being.

By fostering interdisciplinary collaboration, embracing emerging trends, and prioritizing the translation of research findings into practice, the dental community can continue to drive impactful discoveries and advancements for the benefit of individuals worldwide.

1. How can I stay updated on the latest dental research?

Staying updated on the latest dental research can be as simple as subscribing to reputable dental journals, attending conferences, and following dental research institutions and experts on social media platforms.

2. What are some examples of emerging dental research topics?

Emerging dental research topics include genetics and oral health, biomaterials and tissue engineering, and microbiome studies, among others.

3. Why is dental research important for patients?

Dental research drives innovation in oral healthcare, leading to improved treatment outcomes, personalized care, and enhanced preventive strategies for patients.

Related Posts

Science Fair Project Ideas For 6th Graders

When it comes to Science Fair Project Ideas For 6th Graders, the possibilities are endless! These projects not only help students develop essential skills, such…

Java Project Ideas for Beginners

Java is one of the most popular programming languages. It is used for many applications, from laptops to data centers, gaming consoles, scientific supercomputers, and…

- Live CE Event – June 1, 2024

- Self-Study CE Courses

- Live Event CE Certificates

- Dental Quizzes

- Dental Hygiene

Dental Research

- Patient Care

- Life at Work

- Infection Control

- Students & New Grads

- Ask Kara RDH

- Curiosity Killed the Plaque

- Videos & Hygiene Chats

- Hygiene Chats: Kara & Emily

- Hygienist Spotlight

- Today’s RDH Honor Awards

- Submissions

- June 1st Live CE Event

- Featured posts

- Most popular

- 7 days popular

- By review score

Research Finds Potential Association Between Oral Bacteria and High Blood Pressure

Researchers Find the Mechanism Behind Potential Anticancer Properties in Lidocaine

Oral Microbiome and Diet: Researchers Analyze DNA From Ancient “Chewing Gum”

Researchers Use Saliva Analysis to Help Diagnose Pain in Patients with Dementia

Research Reveals an Association Between Primary Teeth Biorhythm and Adolescent Weight Gain

Research Explores How Dietary Choices Affect the Oral Microbiome in Postmenopausal Women

The Mystery of Tooth Enamel Defects: A New Autoimmune Disorder Discovered

Research Suggests Association with Oral Infections and Metabolic Profiles

Researchers Find that Viking Age Dentistry Was Probably More Sophisticated than Previously Thought

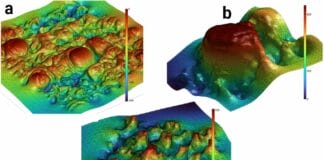

Research Using AI and 3D Imaging Unveils Unique Terrain of Individual Tongue Surfaces

Research Explores Innovative Tissue Regeneration for Endodontic Diseases With Potential Beyond Dentistry

Research Explores the Association Between Immune System’s Memory, Inflammatory Systemic Conditions, and Periodontitis

Systematic Review Analyzes the Association Between Daily Toothbrushing and Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia

Ancient Dental Calculus Reveals an Oral Microbiome Shift after the Black Death

Research Examines the Association Between Periodontal Care and Acute Myocardial Infarction Hospitalization

Research Finds a High Abundance of Previously Unknown Antibiotic-resistant Genes in Bacteria

Research Examines Fluoridated Water’s Impact on Child Emotional and Behavioral Development and Executive Functioning

Longitudinal Look at Tooth Loss and Cognitive Decline among Older Adults

Dental Health Improvement and Its Effects on Dentists’ and Hygienists’ Demand

Research Looks into the Unnecessary Prescribing of Antibiotics Among Dentists

Trending now.

Dental Polishing and Cleansing Agents: A Quick Guide to Coronal Polishing Considerations

4 Simple Tips for Newly Graduated Dental Hygienists

How Hygienists Can Be the First Line of Defense Against Oral Cancer

Caviar Tongue: Are Dental Hygiene Patients Displaying Signs of “Aging?”

- Dental Hygiene 592

- Patient Care 319

- Dental Research 263

- Hygiene Chats & Videos 139

- Life at Work 121

- Healthy Smiles, Healthy Practices 86

- Students & New Grads 56

- COVID-19 53

- Hygienist Spotlight 48

Most Recent

Instrument Sharpening by the RDH: The How and Why

Curiosity Killed the Plaque Ep. 20: Dangers of Oral Clay Products

A Hygienist’s Guide to Succeeding at Dental Conferences

Don't miss.

New Antimicrobial Dental Fillings May Kill Harmful Oral Bacteria

High Blood Pressure: Medications Can Have Impact on Dental Hygiene Care

5 Things to Know about HIPAA When Patients Request Dental Records

Stomatitis: How Dental Professionals Treat and Manage these Conditions

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Dent J (Basel)

Broadening the Dental Hygiene Students’ Perspectives on the Oral Health Professionals: A Text Mining Analysis

Yukiko nagatani.

1 Department of Dental Hygiene, University of Shizuoka Junior College, 2-2-1 Oshika, Suruga-ku, Shizuoka-shi 422-8021, Japan

Rintaro Imafuku

2 Medical Education Development Center, Gifu University, 1-1 Yanagido, Gifu 501-1194, Japan

Yukie Nakai

Associated data.

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Professional identity formation, an important component of education, is influenced by participation, social relationships, and culture in communities of practice. As a preliminary investigation of dental hygienists’ professional identity formation, this study examined changes in the dental hygiene students’ perceptions of oral health professionals over the three years of their undergraduate program. At a Japanese dental hygiene school, 40 students participated in surveys with open-ended questions about professional groups several times during their studies. The text data were analyzed through content analysis with text mining software. The themes that characterized their dental hygienist profession perceptions in their programs each year were identified as: “Supporters at the dental clinic”; “Engagement with interprofessional care” and “Improved problem-solving skills for clinical issues regarding the oral region”; and “Active contribution to general health” and “Recognition of the roles considering relationships” (in the first, second, and third years, respectively). The students acquired professional knowledge and recognized the significance and roles of oral health professionals in practice. They gained more learning experiences in their education, including clinical placements and interprofessional education. This study provides insight into curriculum development for professional identity formation in dental hygiene students.

1. Introduction

Dental hygienists specialize in the control of dental diseases; this profession is prevalent and generally professionally licensed in over 30 countries [ 1 , 2 ]. They are primarily responsible for preventive procedures and non-surgical periodontal treatments. Their role is usually to investigate dental diseases, and motivate and instruct patients about dental health [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. In Japan’s aging society, the necessity of implementing oral health management as primary care is becoming widely recognized by health professionals and the public. It is essential for dental hygienists to prevent and treat dental diseases and support general health by maintaining and promoting the oral environment [ 4 ], and improve the quality of life [ 5 ]. To respond to these social needs, it is necessary to secede from the emphasis on manual procedures in dental clinics [ 6 ] and practice as directed by the dentists; to train the dental hygienists with high qualities and professional skills who can think and practice on their own in the community in cooperation with multiple professionals; and to establish a way of the dental hygiene work that is adapted to the aging society [ 7 ]. Therefore, it is necessary to develop a deep understanding of one’s professional role and expertise, in addition to the roles of the other professionals with whom they work, considering social needs. Moreover, the internalization of this value system promotes the identity formation of a learner who practices in the health profession.

Identity formation is “the process by which an individual self-defines as a member of that profession based on the acquisition of the requisite knowledge, skills, attitudes, values and behaviors” [ 8 ]. It is considered an important component of education in the health profession. In identity formation in health professions, social interactions, experiences, and learning contexts are influential factors. At the collective level, it is influenced by context, including culture and the learning environment chosen by the learner. According to Wenger, gaining practical experience through active engagement and interactions with other members of a community is essential to professional identity formation [ 9 ].

In health profession education, the learners’ profound transformation occurs through learning experiences, most notably the clinical ones [ 10 , 11 , 12 ]. To make the transition from a layperson to a professional, they need learning opportunities that encourage a re-identification of the past (or the present) self [ 13 ]. Furthermore, building social relationships with peers and mentors in clinical education, as well as reflecting and discussing about learning experiences in clinical settings, strengthens professional identity formation through socialization with professional groups [ 14 , 15 ]. Therefore, the health profession education programs need to be structured stepwise from the first year to enable the development of values and professional identity regarding evidence-based practice and professionalism [ 16 ].

The importance of introducing education and support that promotes professional identity formation in dental hygiene education has been internationally recognized. For example, service-learning exercises and curriculum revisions have been implemented to develop students’ attitudes and sense of professional responsibility [ 17 , 18 ]. In addition, Imafuku et al. explored the interprofessional identity formation in dental hygienists [ 19 ]. However, the overall understanding of the process of dental hygienists’ professional identity formation over time, beginning with their first year of study, remains unclear. Clarifying the process of dental hygienists’ professional identity formation could provide insight into students’ actual perceptions of the nature, tasks, and value system of the profession. Analyzing the discrepancy between their perceptions of the profession of dental hygienist and the learning outcomes expected by their teachers would provide a basis for improving and developing new educational strategies and learning support methods in the future. Therefore, in this study, as a preliminary investigation of dental hygienists’ professional identity formation, we examined the changes in their perceptions of the dental hygienist profession during the three years of their undergraduate education.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. participants.

An observational, longitudinal, and prospective study was conducted in the Department of Dental Hygiene at the University of Shizuoka Junior College. All freshmen in the cohort who enrolled in the school in 2019 were invited to participate in this study, and all consented ( n = 40). They were 18–19 years old at the time of enrollment. Their background prior to enrollment was high school or post-high school graduates preparing for university entrance exams. In addition, none of them had clinical experience in the medical field.

2.2. Data Collection

An open-ended questionnaire was self-administered to 40 students each year for three years, from the second half of their first year to the second half of their third year. The open-ended format allowed the researchers to elicit richer data on students’ perceptions of the professional roles and prospects as health professionals at each stage of their undergraduate education. Specifically, this questionnaire survey was structured by five open-ended questions about their reasons for choosing the profession, their ideal future image as a dental professional, their perceptions of professionalism in dental hygiene, societal expectations, and competencies required for the profession. The actual questions in the survey are as listed below:

- - Why did you decide to become a dental hygienist?

- - What kind of dental hygienist do you want to be?

- - What do you think is the professionalism of dental hygienists?

- - What do you think is required of you as dental health professionals by society and patients?

- - What competencies do you think that dental hygienists need to have for clinical practice?

The data were gathered in October 2019 (at the beginning of the first year’s second semester), October 2020 (at the beginning of the second year’s second semester), and November 2021 (at the end of the clinical practice).

2.3. Data Analysis

Data were transcribed from questionnaires and then subjected to text mining analysis using the software, KH Coder 3 (Koichi Higuchi, Kyoto, Japan) [ 20 ]. The software produced a list of words according to their frequencies and interrelationships. It is a quantitative process of adapting algorithms to discover hidden, useful, and interesting patterns in unstructured qualitative text data [ 21 , 22 , 23 ]. In analyzing the qualitative text data, text mining increases the reliability and validity of the coding [ 23 ]. In addition, it can be used in conjunction with human coding content analysis to enhance the rigor [ 24 ].

In this study, the software was used for the research participants’ perceptions of the dental hygienist profession to obtain an overall picture of the diversity, type, and distribution as a framework for understanding the data before conceptualization. A hierarchical cluster analysis was conducted on the pupils’ perceptions of the oral health professionals at each of the three data collection points; moreover, frequently occurring words were extracted. Subsequently, the co-occurrence of the strength of the association between the extracted words was calculated using the Jaccard coefficient. In these analyses, the Key Word in Content (KWIC) concordance function was used to identify words with three or more occurrences to qualitatively examine students’ interpretations of their perceptions of the dental hygienist and how they changed over time. The resulting associations were visually represented on a Co-Occurrence Network Map and coded and categorized by the first and second authors to increase rigor and explore the meaning of the data in conjunction with the qualitative analysis. The authors discussed and identified underlying themes in the visualization of the results. Preliminary results were then discussed and a consensus was reached by all members of the research team. The chi-square test was applied to assess the significance of differences in the distribution of students’ perceptions of oral health professionals at each of the three data collection points using KH Coder, version 3 (Koichi Higuchi, Kyoto, Japan). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

In addition, the relationship between the results of each period and the content of the curriculum taken up to that point, as well as a comparison of the data at the end of the third-year field training with the diploma, were also examined.

2.4. Study Context

This study was conducted at the Department of Dental Hygiene, Junior College of the University of Shizuoka, involving students enrolled in a three-year education program. Regarding the educational philosophy, this school follows the diploma policy, which entails the student learning outcome objectives and graduation approval/degree awarding program; it is set to train dental hygienists who can respond to the oral health needs of the community. A junior college bachelor’s degree is awarded to those who have studied in an educational program to acquire the abilities listed below and have earned the necessary credits.

- - Professional knowledge, abilities, and communication skills related to dental hygiene

- - Logical thinking and problem-solving skills

- - Awareness of their roles and responsibilities as dental hygiene practitioners and the ability to perform them appropriately

- - A rich sense of humanity and high ethical standards, and ability to collaborate and cooperate with other professionals

- - Contribution to the development of people’s health and a striving for lifelong learning.

In the training school included in this study, the curriculum was designed to enable students to achieve the above-mentioned diploma. As shown in Figure 1 , in the first year, students attend lectures on liberal arts, basic specialties, and dental hygiene. In the second year, they opt for specialized clinical subjects, on-campus training related to dental hygiene work, and subjects related to interpersonal support and well-being in collaboration with students from other departments. In addition, elective subjects related to health and medical well-being have been established from the second semester of the first year to the first semester of the second year. After studying these subjects, the third year includes off-campus practical training in dental clinics, oral surgery departments of general hospitals, nursing homes, and disability support facilities.

Three-year curriculum of dental hygiene at the research site. (The intensity of the color indicates the volume of the subject’s content.)

2.5. Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the University of Shizuoka Research Ethics Committee [approval number 1-19]. Furthermore, informed consent was provided by all the study participants.

3.1. Changes in the Word Frequency

Overall, 333 statements were related to the professional role and attitude of dental hygiene, of which 120, 177, and 192 statements were categorized for the first, second, and third years, respectively. The following five words were found to occur over 30 times in total:

- Oral: 90 times

- Patient: 64 times

- Dental: 62 times

- Health: 51 times

- Knowledge: 35 times

3.2. Number of Code Occurrences

The occurrence rate of the aforementioned words varied from year to year ( Figure 2 ). In the first year, “oral” was the most frequently appearing word, followed by “prevention”, “dental”, “health”, “knowledge”, and “patient”; in the second year, “oral” was the most frequently occurring word, similar to the first year, followed by “patient”, “dental”, “health”, “whole body”, and “knowledge”. The increased utilization of the words “patient” and “whole body” was characteristic. The former occurred 12, 24, and 28 times in the first, second, and third years of school, respectively, and the number of occurrences tended to increase as the school year progressed. In the third year, “oral” was the most frequently used word, followed by “patient”, “dental”, “health”, “do”, and “knowledge”, similar to the first and second years. Although “do” did not occur in the first year, it showed an increasing trend with 5 and 13 occurrences in the second and third years, respectively. However, the number of occurrences of “prevention” tended to decrease with increasing grade level, from 16 to 8 and 6 times in the first, second, and third years, respectively.

The number of the extracted words of expertise perceived by the dental hygiene students over time.

3.3. Code Occurrence Rate

Figure 3 visualized the changes in the occurrence rate of the specialty codes as perceived by the dental hygiene students over time. The square size indicates the occurrence rate of each code (showing “percent”), and its color corresponds to the standardized residuals (Pearson residuals). Therefore, a larger square represents a higher rate of occurrence, and the darker color represents the larger residual. According to Figure 3 , only “do”, which did not appear in the first year, showed a significant difference in the proportion of the occurrence of the three points ( p < 0.05, Chi-square test).

Changes in the occurrence of the specialty codes as perceived by the dental hygiene students.

3.4. Recognition of Professional Roles, Competence, and Attitude at the Three Time Points Based on the Strength of the Relationship between the Words

From the co-occurrence network model diagram showing the strength of the association between the words with three or more occurrences, the characteristic themes were extracted for the dental hygiene students’ perceptions of their professional roles, competence, and attitude at each of the three time points, using the KWIC concordance function to assess the word usage.

3.4.1. At the Beginning of the First Year’s Second Semester

During the first year, the following two themes were extracted ( Figure 4 ):

The co-occurrence network diagram of the first-year dental hygienists’ perceptions of professional role and competencies.

Supporters at the Dental Clinic

The dental hygienists were identified as assistants in the dental clinic, professionals who help patients improve their health by providing expert knowledge and skillful care in the prevention and treatment of dental caries, alleviating their fear of treatment, and supporting the dentists during the dental treatment.

- - “How to comfort the patients at the dental clinic, a place where they are considered to be uncomfortable”.

- - “Supporting the dental treatment to run smoothly”.

Understanding the Relationship between Oral and General Health

The participants were aware that the oral region and the whole body are deeply related; however, as professionals in oral health, they believed that they must enhance their knowledge, treatment, instruction, and care techniques for “improving the health of the whole body through oral care”.

- - “Understanding better than anyone else that the teeth and oral health are linked to general health”.

- - “Dental caries prevention and understanding the relationship between the oral region and the whole body”.

- - “The ability to communicate the importance of oral health in various settings, both in the medical and educational fields”.

3.4.2. At the Beginning of the Second Year’s Second Semester

During the second year, the following four themes were extracted: ( Figure 5 ).

The co-occurrence network diagram of the second-year dental hygienists’ perceptions of professional role and competencies.

Dental Hygienists’ Work Frames

Participants recognized the framework of the three main tasks of a dental hygienist in Japan, including caries prevention treatment through fluoride application, assistance work for smooth dental treatment by standing between patients and dentists, and oral health instruction.

- - “Must be able to assist in the dental treatment, provide the oral health instruction, and perform the caries prevention procedures”.

- - “A person who can stand between the dentist and the patient and contribute to enhanced treatment”.

Engagement with Interprofessional Care

The participants felt they must have a broad knowledge of medicine, not only regarding oral health, which is their profession, but also systemic diseases. They aimed to confidently collaborate and communicate with multiple professionals and develop the ability to handle interprofessional medicine that could provide patient-centered care.

- - “To acquire an awareness of the whole body, not just the oral, and to be able to perform team medicine with other professionals”.

- - “Have a patient-centered attitude and the communication skills to practice in a team-based environment”.

Health Support from the Perspective of the Oral Health

The need for dental hygienists to acquire medical information along with oral health knowledge in order to demonstrate support for general health from the perspective of oral health has been recognized. These skills help prevent infection and improve general health and quality of life by helping to maintain and promote oral health throughout life, including the perioperative period and old age.

- - “To improve the quality of life as well as the oral health of patients”.

- - “Promoting and maintaining general health through the oral health”.

Improved Problem-Solving Skills for Clinical Issues Regarding the Oral Region

The participants were aware of their role in solving and improving oral problems. Therefore, participants recognized the need for the ability to provide medical care, including instruction, care, and hygiene management, to identify and resolve issues based on each person’s condition status and needs, and to build a relationship of trust with the patient.

- - “Perceive the patients’ condition, their oral health situation, understand their problems, and provide them with appropriate care to resolve those issues”.

- - “I think it is about improving oral health, instructing about oral health, and building trusting relationships to solve oral health problems”.

3.4.3. At the End of the Third-Year Clinical Practice

At the end of the third-year clinical practice, the following four themes were identified: ( Figure 6 ).

The co-occurrence network diagram of the dental hygienists’ perceptions of professional role and competencies in the third year.

Active Contribution to General Health

Participants mentioned the need for evidence-based and correct professional knowledge and skills, as well as the ability to make decisions in clinical practice. They recognized that acquiring these competencies would enable them to respond to patient complaints and work smoothly with multiple health care professionals from an oral health perspective.

- - “Dental as well as medical knowledge and working with various professionals to approach problems”.

- - “As a dental hygienist, we must have the knowledge to answer patient complaints”.

Recognition of the Roles Considering Relationships

As professionals supporting patients’ autonomous oral health care, they recognized their role in improving self-care and providing professional care based on their relationship with patients; they were able to incorporate specific preventive approaches such as dietary instructions and periodontal treatments. In addition, they recognized their role based on their clinical relationship with the dentist, which included managing the patients overall health during treatment and paying attention to the intentions and feelings of both the patient and the dentist.

- - “We are professionals in terms of prevention; thus, hygienists are required to provide care and prevention so that we do not get to the treatment stage”.

- - “To support the patients’ feelings (chief complaint) and to help them feel comfortable through the dentist”.

Protecting the Oral and Overall Health

The students expressed their intention to be actively involved in the whole health management not limited to oral health care, such as supporting the daily quality of life from a holistic perspective.

- - “Improvement of the overall health and quality of life through oral health”.

- - “To enhance the quality of life by improving and maintaining oral health that is closely related to the everyday life, such as eating, speaking and laughing”.

Intervention in the Life Context

In the approach to oral health maintenance and promotion, participants recognized the need to not only understand the oral and general condition of patients, but also to actively incorporate their oral function and hygiene into their daily lives by intervening in their life background, such as their diet and lifestyle.

- - “To be able to provide health instruction from a dental perspective, including dietary instruction and lifestyle modification”.

- - “To provide instruction for the patients’ own oral health self-care, so that they themselves can maintain a good oral health”.

4. Discussion

This study found that dental hygiene students’ perceptions were strongly influenced and shaped by their learning experiences during college. This included lectures on their specific duties, the interdisciplinary education program, and clinical placements in dental facilities. As previous studies have shown, it is critical that they gain a clear understanding of the core values, expectations, and behaviors of the profession during health professions education and are encouraged to develop their own identities in addition to acquiring knowledge and skills [ 14 , 25 ]. Accordingly, the present longitudinal research demonstrated four aspects of changing the perceptions of the oral health professional among dental hygiene students.

The first aspect is the relationship between knowledge acquisition and professionalism. The establishment of a knowledge system in a professional domain has a significant impact on identity formation [ 26 , 27 ]. Moreover, self-efficacy has been related to professional recognition, skill mastery, and knowledge [ 28 ]. In this research, the first-year students were expected to acquire knowledge related to the “oral and general health promotion” such as “dental caries prevention and understanding the relationship between the oral region and the whole body” and “the teeth and oral health are linked to general health”. In the second year, the concept of the “dental hygienists’ work frames” learned in lectures such as “assist in the dental treatment, provide the oral health instruction, and perform the caries prevention procedures”, was often mentioned as a competence of dental hygienists. Specifically, in the first and second years, their professionality was frequently viewed from the aspect of knowledge acquisition reflected in the content of the specialized clinical courses. Knowledge acquisition is also essential in forming the professional identity foundation [ 26 ]. Nevertheless, in the first and second years, the students tended to focus excessively on obtaining the expertise of a dental hygienist. As it is said that identity formation is facilitated by active engagement and interaction in the community [ 9 ], therefore, education programs that promote the pupils’ understanding of “Recognition of the roles considering relationships”, such as communication training, interprofessional education, and early exposure program need to be developed and incorporated into the basic education stage. For example, early exposure is an educational strategy to help students adapt to the clinical environment, improve their skills of reflection and evaluation, and establish their professional identity [ 29 , 30 , 31 ].

Regarding knowledge acquisition, enhancing logical thinking and problem-solving skills are key for curriculum development. Specifically, it is important to incorporate research and exploratory activities into each subject area step-by-step in dental hygiene education. These skills are necessary to apply the acquired knowledge in practice. In medical education, undergraduate research courses in which pupils independently conduct research for a certain time have been offered; further, efforts to improve their logical thinking and evidence-based medicine have been reported [ 32 , 33 ]. Similarly, in the three years of dental hygiene education, it is necessary to promote a continuum of learning through exploratory activities about assessment, planning, implementation, and evaluation to develop logical thinking and problem-solving skills for evidence-based medical practice [ 34 ]. Therefore, educational objectives and content should be jointly determined by the clinical practice organization and the educational institution, and research activities should be integrated into the curriculum.

The second aspect is the students’ broadened perceptions of their professional roles and responsibilities, which influence professional identity formation [ 35 , 36 , 37 ]. Thus, this study indicated the changes in the pupils’ perceptions of the role and responsibilities of a dental hygienist. Specifically, the first-year students limited the place of work to the “dental clinic” and viewed dental hygienists as professionals involved in the dental care there; further, there was a limited term or phrase indicating a professional role of caring for people at different life stages, such as oral function management in the elderly and perioperative oral care. In the second year, the pupils acquired the perspective of the “patient” and the theme of supporting patient health from the oral health perspective was extracted. In the third year, the theme of protecting the patient’s overall health as a role of a dental hygienist was obtained. These results suggested that health is not limited to the oral region but is also considered from the standpoint of the whole body and that the students had been taking more initiative in “protecting” the patient’s health. Furthermore, the vague image of the role of a dental hygienist in the first year was transformed into a more concrete image and gained a more generalist view. They were able to think about the clinical issues from a patient’s standpoint in the third year. Their text data included “improving and maintaining oral health that is closely related to everyday life, such as eating, speaking and laughing”, and the “improvement of the overall health and quality of life through oral health”. This result is consistent with that of the study by Imafuku et al., that explored the identity formation processes of dental hygienists in the field as interprofessional collaborators [ 19 ]; however, the significance of this research is that it showed that such a change in perception might be occurring among the undergraduate students.

In dental hygienist education, for example, it is essential to provide opportunities for the students to reaffirm professional values and beliefs, including what kind of a dental hygienist they want to become, and to clarify their vision for the future in their education’s early stage. In clinical education, dental hygienists and other professionals can assume specific roles within the community of practice through collaborative practice. To encourage group-level socialization, opportunities to meet role models who are active in various situations [ 8 , 38 ] and internships in a community of practice can be used. It is also important to incorporate into the curriculum supportive methods that internalize the values of the dental hygienist during these social experiences [ 8 , 25 , 38 , 39 , 40 ]

The third aspect is a change in perception from individual to team care. Over three years, this study’s participants modified their perceptions of the dental hygienist’s professional role and responsibilities from a focus on the “individual” as a specialist involved in the dental treatment to an “interpersonal” or “team” perspective, such as interprofessional collaboration and patient communication. In the first year, many of the texts referred to their skills, such as “dental caries prevention and understanding the relationship between the oral region and the whole body” and “the ability to communicate the importance of oral health in various settings, both in the medical and educational fields”. Similarly, in the second year, there were several statements about their skills; however, the concepts related to the professions in which they work with the people they care for, such as “provide them with appropriate care to resolve these issues” and “have a patient-centered attitude and the communication skills to practice in a team-based environment”, were more common. During this time, students are believed to have gained a deeper understanding of the relationship between oral and general health, as well as a perspective on the importance of the dental hygienist’s intervention to a person’s general health through the study of specialized clinical subjects. In addition, learning about welfare, management, and clinical psychology, planning dental health instruction, and experiencing being in the role of a patient during campus clinical training may have fostered an awareness of the need for interprofessional collaboration, the ability to provide interpersonal support, and the responsibility to solve health problems. In the third year, students interacted with patients and dental hygienists in clinical practice. They noted the relationships between patients and medical staff, patients and dental hygienists, and dental hygienists and various professionals. Students mentioned the need for clarification of the relationship and their own roles between dental hygienists and multidisciplinary professionals, the ability to respond to patient complaints, the ability to make judgments that allow active participation in multidisciplinary care confidently, and scientifically sound clinical skills.

This finding corroborates the results of previous studies, which show that students focus more on enhancing teamwork and collaborative practice, and their identity confidence is increased after interprofessional education programs [ 41 , 42 ]. However, this study did not confirm the pupils’ improved collective learning skills, such as consensus-building and leadership, and the relationships between their interprofessional learning experience and quality care provision, as suggested by Cooper and Imafuku [ 41 , 42 ]. A possible factor influencing this is that during their clinical practice at the university, the pupils themselves had limited opportunities to experience interprofessional collaborative practice with professionals other than dentists.

Regarding interprofessional collaboration, most clinical practice hours were spent in private dental clinics, presumably because there were not enough opportunities to experience situations of interprofessional collaboration with other professionals. During the five-day oral surgery clinical practicum in the general hospital, students did not proactively practice interprofessional collaboration due to the severity of patients’ illnesses, systemic management issues, and limited skills; it is assumed that they only observed the instructor and had difficulty recognizing interprofessional collaboration. Furthermore, there is a strong perception that they are employees who perform their duties under the instruction of the Dental Hygienists Act, which states that “dental hygienists are those whose work is to perform the following acts under the instruction of dentists and preventive measures for diseases of the teeth and oral” [ 43 ]. Annan-Coultas indicated that observations of real-life teamwork environments can be a meaningful way to teach interprofessional teamwork concepts [ 44 ]. Similarly, although it is difficult for pupils to practice interprofessional teamwork on high-risk patients in a clinical setting, it may be useful for them to observe a multidisciplinary conference and how dental hygienists practice collaborative medicine in such a situation to deepen their awareness of interprofessional collaboration.

Finally, analysis of the textual data suggests that dental hygiene students have a stronger sense of ownership as health care providers. It suggests that participation in the clinical placements strengthened students’ professional identity and sense of responsibility. Specifically, text analysis in the third year showed that the verbs “to do” and “to protect”, which indicate proactive action in terms of professional role and responsibility, were frequently described. This change may be primarily due to their insertion into the dental clinic community during their field training and gaining experience in clinical practice, albeit in a peripheral role, while building relationships with the dentists and dental hygienists in the dental clinic. Students’ identities are formed not only by their associations with professional networks, but also by their actual experiences and participation in the community [ 9 ].

The increased sense of ownership is related to student’s attitude toward lifelong learning. Thus, further educational support is needed from the first-year education to continuously enhance their awareness of the importance of self-learning in healthcare. Lifelong learning is an integral part of the communities of practice, with time and expectations for reflection [ 45 ]. Encouraging pupils to reflect on their experiences in clinical placements deeply can enhance their awareness of lifelong learning and cultivate their self-learning skills. Some studies in medical education show that medical students’ identities are promoted in relationships through reflective activities and the need to provide educational spaces for them to understand their identity as a doctor by recounting their clinical experiences [ 14 , 46 , 47 ].

In this study, we conducted a content analysis of an open-ended questionnaire related to the role and competencies of oral health professionals in dental hygiene students. The results of this study have implications for society as a whole, particularly in the areas of dental education and health care. However, the questionnaire survey did not reflect the background of the students’ descriptions, what they could not express, and the depth of their insight. In particular, we did not explore the kind of individuality and specific experiences from which their perceptions emerged, how they perceived their experiences, and what kind of identity they formed in the narrative process. In addition, although we related the changes in students’ perceptions to the curriculum, we were unable to examine the influence of extracurricular factors, such as extracurricular activities and prior learning experiences. As the data in this study were compiled and compared across all participants at the three time points, changes in individual perceptions over time could not be tracked and the effects of individual personalities and environments could not be analyzed. Therefore, further qualitative interview studies are needed to more fully incorporate students’ experiences behind their perceptions of professionals and to shed light on professional identity formation among dental hygienists.

5. Conclusions

The dental hygiene students in this study acquired professional knowledge, became aware of the importance and role of oral health professionals in practice, and broadened their perspectives as dental hygienists through their health care education, which included lectures, clinical placements, and interprofessional education. Therefore, this study provides insight into the development of curricula to promote the professional identity of dental hygiene students.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the dental hygiene students who participated in this study.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the research grant of the University of Shizuoka and JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP22K17279.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.N. (Yukiko Nagatani) and R.I.; methodology, Y.N. (Yukiko Nagatani) and R.I; software, Y.N. (Yukiko Nagatani); validation, Y.N. (Yukiko Nagatani), R.I. and Y.N. (Yukie Nakai); formal analysis, Y.N. (Yukiko Nagatani) and R.I.; investigation, Y.N. (Yukiko Nagatani) and R.I.; resources, Y.N. (Yukiko Nagatani) and R.I.; data curation, Y.N. (Yukiko Nagatani) and Y.N. (Yukie Nakai); writing—original draft preparation, Y.N. (Yukiko Nagatani) and R.I.; writing—review and editing, Y.N. (Yukiko Nagatani) and R.I.; visualization, Y.N. (Yukiko Nagatani) and R.I.; supervision, Y.N. (Yukie Nakai); project administration, Y.N. (Yukiko Nagatani); funding acquisition, Y.N. (Yukiko Nagatani). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the national and institutional ethical standards. The ethical approval for the study protocol was obtained from the Human Institutional and Regional Biomedical Research Ethics Committee, the University of Shizuoka Research Ethics Committee [approval number 1-19].

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of interest.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Division of HHS: Dental Health Programs: Hygiene Capstone Project

- General Resources Lists

- Trending News

- FHTC Career Placement

- DNA/ HYG- APA Citation

- DNA PDV Cultural Diversity

- HYG 232 Special Needs

- Virtual Desktop- Software Access

- Helpful Paper Writing Tools

- Creating Presentations

Hygiene Capstone Project

This capstone project is designed to provide the student with an opportunity to apply their knowledge of concepts and skills through an individually designed project. Students will execute the project through the development and implementation of a patient treatment plan that culminates in a final paper and presentation on the specific "Periodontal Type II" or greater case identified.

Keys to Finding Research

Some Basics of Searching for Research:

1.) In any search bar start with the whole of your research topic. For example: If the topic of the paper is "Periodontal Attachment Loss in Diabetic Patients" and you only search "Attachment Loss," you will get articles and information that do not apply to the topic. Start with the whole topic and see what comes up.

2.) Refining the results:

2a.) TOO MUCH - If you are getting too many articles, try putting quotes around key search terms "Attachment Loss" "Diabetic Patients." This will limit the search to articles where those terms appear beside each other in context.

2b.) NOT ENOUGH- Break down the topic into variations . "Diabetes and Dental Care," "Attachment Loss in Dental Care," "Periodontal Care and Diabetes"

3.) Don't stop at the required number of sources! Although the requirement says you need three additional resources, always find a few more than required. Just because you have them, doesn't mean you have to use them. It is better to have choices when writing a paper than trying to force a paper from limited options.

4.) READ THE WHOLE ARTICLE (Or at the very least 1st Paragraph, a Middle Paragraph, and the Last paragraph)!!! Your search engine may pull up an article that has your search terms in the article, but that does not always mean the article actually speaks to your topic. Be sure that the entirety of the source supports your topic, not just a single sentence.

Link to APA Libguide

- How To: APA Formatting Guide Link To connect to the full libgide on APA formatting click here. Offers additional videos, instruction, links, and source citation breakdowns.

Your Assignment

- Case Study and Assignment Details

- Project Rubric 2022-2-16

Guide Video

Plagiarism: What it is and how to avoid it

- Plagiarism Rutgers University This link opens in a new window Entertaining video describing plagiarism and how to avoid it.

- Dr. Cite Rite Central Piedmont Community College Libraries This link opens in a new window Help for citing correctly.

- You Quote It, You Note It Acadia University This link opens in a new window Techniques for proper citation.

- Plagiarism Court Fairfield University This link opens in a new window Choose Flash or HTML for viewing this video.

- What is plagiarism and how to avoid it 2 Minute video explaining plagairism

- Schmooc on Plagiarism This 4 minute video is funny but explains the ins and outs of plagiarism very well.

- Tips to avoid Accidental Plagiarism Best methods to make sure you do not accidentally plagiarize.

Recommended Research Sites

- FHTC Online Library Quick Link Available 24/7

Even if you are researching from home there are resources that can be accessed from the Online Library Catalog. There are several eBooks and eVideos on the topic options for your research paper. Click the link below, use the login information listed, search for your topic area. Pay attention to "format" information if you want only online material.

- Kansas State Library Quick Link Click on "Online Resources" Scroll down to the "Health" collection to find recommended databases. To Expand click "View All" at the bottom of the list

-For general knowledge of conditions or disorders the "Gale Health Reference Collection" is recommended for starting your research.

-For research studies, journal articles, and similar academic based materials on your topics go to "Health Source Academic & Nursing;" " ProQuest Nursing and Allied Health;" or "Medline"

-For some topics these databases will be of value: "Alternative HealthWatch;" "Consumer Health Complete;" "Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection"

-Remember to only use FULL-TEXT articles. Never use "Abstracts" as primary research.