- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Quantitative Methods in Sociological Research

Introduction, professional associations.

- Data Sources

- Data Archives

- Statistical Software Packages

- Research Design

- Survey Research

- Categorical Data Analysis

- Longitudinal Data Analysis

- Structural Equation Modeling

- Multilevel Modeling

- Causal Inference

- Critical Reflections

- Mixed Methods

- Network Analysis

- Training and Other Resources

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Agent-Based Modeling

- Cohort Analysis

- Mathematical Sociology

- Multilevel Models

- Panel Studies

- Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA)

- Qualitative Methods in Sociological Research

- Social Indicators

- Social Networks

- Survey Methods

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Consumer Credit and Debt

- Global Inequalities

- LGBTQ+ Spaces

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Quantitative Methods in Sociological Research by Erin Leahey LAST REVIEWED: 13 November 2018 LAST MODIFIED: 27 July 2011 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199756384-0044

Sociology develops, adopts, and adapts a wide variety of methods for understanding the social world. Realizing that this embarrassment of riches can bewilder the newcomer, this entry is intended to guide scholars through some of the main methods used by quantitative social scientists and some of the key resources for learning such methods. Because many sociologists in the United States receive foundational training in multivariate linear regression, this entry focuses on developments that go beyond this topic, including categorical data analysis, structural equation modeling, multilevel modeling, longitudinal data analysis, causal inference, and even network analysis. The recent wave of interest in mixed methods also merits inclusion. A section on critical reflections aims to encourage researchers to be reflective and thoughtful about the approach(es) they choose.

A number of professional associations are open to quantitative methodologists and researchers, including the two ASAs ( American Sociological Association and American Statistical Association ), the Population Association of American (PAA) , for demographers broadly defined, and the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) for survey researchers and methodologists.

American Association of Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) .

Founded in 1947, AAPOR is an association of individuals who share an interest in survey research, qualitative and quantitative research methods, and public opinion data. Members come from academia, media, government, the nonprofit sector, and private industry. Meetings are held in even-numbered years.

American Sociological Association (ASA) .

The national professional association for sociologists, ASA serves as a reference for professional, ethical, and pedagogical topics; sponsors nine journals; and hosts an annual meeting.

American Statistical Association (ASA) .

ASA is the world’s largest community of statisticians and the second-oldest professional society in the United States. For 170 years, ASA has supported excellence in the development and dissemination of statistical science. Its members serve in industry, government, and academia, advancing research and promoting sound statistical practice to inform public policy and improve human welfare.

Population Association of America (PAA) .

PAA is a nonprofit organization that promotes research on population issues such as fertility, migration, health, and mortality. PAA sponsors the journal Demography .

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Sociology »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Actor-Network Theory

- Adolescence

- African Americans

- African Societies

- Analysis, Spatial

- Analysis, World-Systems

- Anomie and Strain Theory

- Arab Spring, Mobilization, and Contentious Politics in the...

- Asian Americans

- Assimilation

- Authority and Work

- Bell, Daniel

- Biosociology

- Bourdieu, Pierre

- Catholicism

- Chicago School of Sociology

- Chinese Cultural Revolution

- Chinese Society

- Citizenship

- Civil Rights

- Civil Society

- Cognitive Sociology

- Collective Efficacy

- Collective Memory

- Comparative Historical Sociology

- Comte, Auguste

- Conflict Theory

- Conservatism

- Consumer Culture

- Consumption

- Contemporary Family Issues

- Contingent Work

- Conversation Analysis

- Corrections

- Cosmopolitanism

- Crime, Cities and

- Cultural Capital

- Cultural Classification and Codes

- Cultural Economy

- Cultural Omnivorousness

- Cultural Production and Circulation

- Culture and Networks

- Culture, Sociology of

- Development

- Discrimination

- Doing Gender

- Du Bois, W.E.B.

- Durkheim, Émile

- Economic Institutions and Institutional Change

- Economic Sociology

- Education and Health

- Education Policy in the United States

- Educational Policy and Race

- Empires and Colonialism

- Entrepreneurship

- Environmental Sociology

- Epistemology

- Ethnic Enclaves

- Ethnomethodology and Conversation Analysis

- Exchange Theory

- Families, Postmodern

- Family Policies

- Feminist Theory

- Field, Bourdieu's Concept of

- Forced Migration

- Foucault, Michel

- Frankfurt School

- Gender and Bodies

- Gender and Crime

- Gender and Education

- Gender and Health

- Gender and Incarceration

- Gender and Professions

- Gender and Social Movements

- Gender and Work

- Gender Pay Gap

- Gender, Sexuality, and Migration

- Gender Stratification

- Gender, Welfare Policy and

- Gendered Sexuality

- Gentrification

- Gerontology

- Globalization and Labor

- Goffman, Erving

- Historic Preservation

- Human Trafficking

- Immigration

- Indian Society, Contemporary

- Institutions

- Intellectuals

- Intersectionalities

- Interview Methodology

- Job Quality

- Knowledge, Critical Sociology of

- Labor Markets

- Latino/Latina Studies

- Law and Society

- Law, Sociology of

- LGBT Parenting and Family Formation

- LGBT Social Movements

- Life Course

- Lipset, S.M.

- Markets, Conventions and Categories in

- Marriage and Divorce

- Marxist Sociology

- Masculinity

- Mass Incarceration in the United States and its Collateral...

- Material Culture

- Medical Sociology

- Mental Illness

- Methodological Individualism

- Middle Classes

- Military Sociology

- Money and Credit

- Multiculturalism

- Multiracial, Mixed-Race, and Biracial Identities

- Nationalism

- Non-normative Sexuality Studies

- Occupations and Professions

- Organizations

- Parsons, Talcott

- Political Culture

- Political Economy

- Political Sociology

- Popular Culture

- Proletariat (Working Class)

- Protestantism

- Public Opinion

- Public Space

- Race and Sexuality

- Race and Violence

- Race and Youth

- Race in Global Perspective

- Race, Organizations, and Movements

- Rational Choice

- Relationships

- Religion and the Public Sphere

- Residential Segregation

- Revolutions

- Role Theory

- Rural Sociology

- Scientific Networks

- Secularization

- Sequence Analysis

- Sex versus Gender

- Sexual Identity

- Sexualities

- Sexuality Across the Life Course

- Simmel, Georg

- Single Parents in Context

- Small Cities

- Social Capital

- Social Change

- Social Closure

- Social Construction of Crime

- Social Control

- Social Darwinism

- Social Disorganization Theory

- Social Epidemiology

- Social History

- Social Mobility

- Social Movements

- Social Network Analysis

- Social Policy

- Social Problems

- Social Psychology

- Social Stratification

- Social Theory

- Socialization, Sociological Perspectives on

- Sociolinguistics

- Sociological Approaches to Character

- Sociological Research on the Chinese Society

- Sociological Research, Qualitative Methods in

- Sociological Research, Quantitative Methods in

- Sociology, History of

- Sociology of Manners

- Sociology of Music

- Sociology of War, The

- Suburbanism

- Symbolic Boundaries

- Symbolic Interactionism

- The Division of Labor after Durkheim

- Tilly, Charles

- Time Use and Childcare

- Time Use and Time Diary Research

- Tourism, Sociology of

- Transnational Adoption

- Unions and Inequality

- Urban Ethnography

- Urban Growth Machine

- Urban Inequality in the United States

- Veblen, Thorstein

- Visual Arts, Music, and Aesthetic Experience

- Wallerstein, Immanuel

- Welfare, Race, and the American Imagination

- Welfare States

- Women’s Employment and Economic Inequality Between Househo...

- Work and Employment, Sociology of

- Work/Life Balance

- Workplace Flexibility

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|195.216.135.184]

- 195.216.135.184

2.2 Research Methods

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you should be able to:

- Recall the 6 Steps of the Scientific Method

- Differentiate between four kinds of research methods: surveys, field research, experiments, and secondary data analysis.

- Explain the appropriateness of specific research approaches for specific topics.

Sociologists examine the social world, see a problem or interesting pattern, and set out to study it. They use research methods to design a study. Planning the research design is a key step in any sociological study. Sociologists generally choose from widely used methods of social investigation: primary source data collection such as survey, participant observation, ethnography, case study, unobtrusive observations, experiment, and secondary data analysis , or use of existing sources. Every research method comes with plusses and minuses, and the topic of study strongly influences which method or methods are put to use. When you are conducting research think about the best way to gather or obtain knowledge about your topic, think of yourself as an architect. An architect needs a blueprint to build a house, as a sociologist your blueprint is your research design including your data collection method.

When entering a particular social environment, a researcher must be careful. There are times to remain anonymous and times to be overt. There are times to conduct interviews and times to simply observe. Some participants need to be thoroughly informed; others should not know they are being observed. A researcher wouldn’t stroll into a crime-ridden neighborhood at midnight, calling out, “Any gang members around?”

Making sociologists’ presence invisible is not always realistic for other reasons. That option is not available to a researcher studying prison behaviors, early education, or the Ku Klux Klan. Researchers can’t just stroll into prisons, kindergarten classrooms, or Klan meetings and unobtrusively observe behaviors or attract attention. In situations like these, other methods are needed. Researchers choose methods that best suit their study topics, protect research participants or subjects, and that fit with their overall approaches to research.

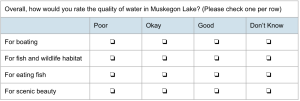

As a research method, a survey collects data from subjects who respond to a series of questions about behaviors and opinions, often in the form of a questionnaire or an interview. The survey is one of the most widely used scientific research methods. The standard survey format allows individuals a level of anonymity in which they can express personal ideas.

At some point, most people in the United States respond to some type of survey. The 2020 U.S. Census is an excellent example of a large-scale survey intended to gather sociological data. Since 1790, United States has conducted a survey consisting of six questions to received demographical data pertaining to residents. The questions pertain to the demographics of the residents who live in the United States. Currently, the Census is received by residents in the United Stated and five territories and consists of 12 questions.

Not all surveys are considered sociological research, however, and many surveys people commonly encounter focus on identifying marketing needs and strategies rather than testing a hypothesis or contributing to social science knowledge. Questions such as, “How many hot dogs do you eat in a month?” or “Were the staff helpful?” are not usually designed as scientific research. The Nielsen Ratings determine the popularity of television programming through scientific market research. However, polls conducted by television programs such as American Idol or So You Think You Can Dance cannot be generalized, because they are administered to an unrepresentative population, a specific show’s audience. You might receive polls through your cell phones or emails, from grocery stores, restaurants, and retail stores. They often provide you incentives for completing the survey.

Sociologists conduct surveys under controlled conditions for specific purposes. Surveys gather different types of information from people. While surveys are not great at capturing the ways people really behave in social situations, they are a great method for discovering how people feel, think, and act—or at least how they say they feel, think, and act. Surveys can track preferences for presidential candidates or reported individual behaviors (such as sleeping, driving, or texting habits) or information such as employment status, income, and education levels.

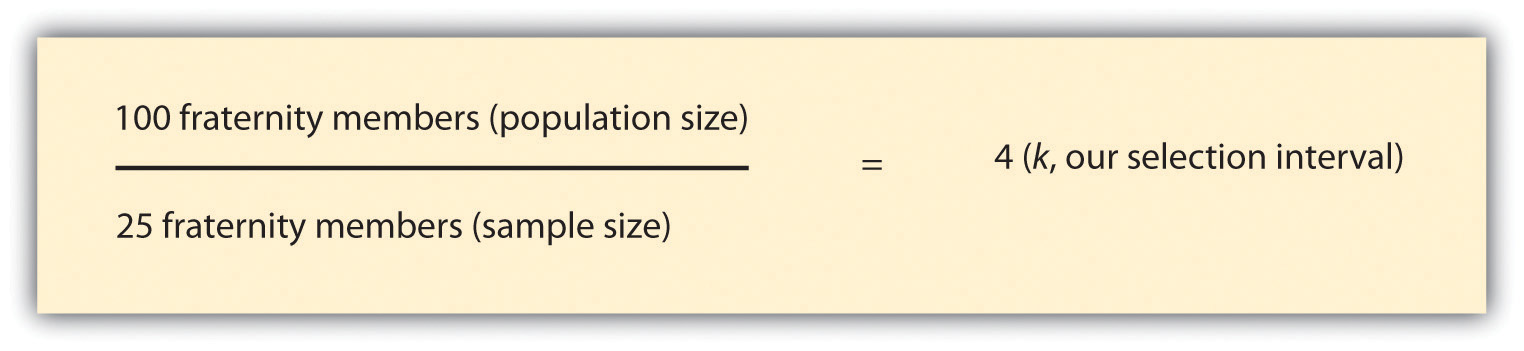

A survey targets a specific population , people who are the focus of a study, such as college athletes, international students, or teenagers living with type 1 (juvenile-onset) diabetes. Most researchers choose to survey a small sector of the population, or a sample , a manageable number of subjects who represent a larger population. The success of a study depends on how well a population is represented by the sample. In a random sample , every person in a population has the same chance of being chosen for the study. As a result, a Gallup Poll, if conducted as a nationwide random sampling, should be able to provide an accurate estimate of public opinion whether it contacts 2,000 or 10,000 people.

After selecting subjects, the researcher develops a specific plan to ask questions and record responses. It is important to inform subjects of the nature and purpose of the survey up front. If they agree to participate, researchers thank subjects and offer them a chance to see the results of the study if they are interested. The researcher presents the subjects with an instrument, which is a means of gathering the information.

A common instrument is a questionnaire. Subjects often answer a series of closed-ended questions . The researcher might ask yes-or-no or multiple-choice questions, allowing subjects to choose possible responses to each question. This kind of questionnaire collects quantitative data —data in numerical form that can be counted and statistically analyzed. Just count up the number of “yes” and “no” responses or correct answers, and chart them into percentages.

Questionnaires can also ask more complex questions with more complex answers—beyond “yes,” “no,” or checkbox options. These types of inquiries use open-ended questions that require short essay responses. Participants willing to take the time to write those answers might convey personal religious beliefs, political views, goals, or morals. The answers are subjective and vary from person to person. How do you plan to use your college education?

Some topics that investigate internal thought processes are impossible to observe directly and are difficult to discuss honestly in a public forum. People are more likely to share honest answers if they can respond to questions anonymously. This type of personal explanation is qualitative data —conveyed through words. Qualitative information is harder to organize and tabulate. The researcher will end up with a wide range of responses, some of which may be surprising. The benefit of written opinions, though, is the wealth of in-depth material that they provide.

An interview is a one-on-one conversation between the researcher and the subject, and it is a way of conducting surveys on a topic. However, participants are free to respond as they wish, without being limited by predetermined choices. In the back-and-forth conversation of an interview, a researcher can ask for clarification, spend more time on a subtopic, or ask additional questions. In an interview, a subject will ideally feel free to open up and answer questions that are often complex. There are no right or wrong answers. The subject might not even know how to answer the questions honestly.

Questions such as “How does society’s view of alcohol consumption influence your decision whether or not to take your first sip of alcohol?” or “Did you feel that the divorce of your parents would put a social stigma on your family?” involve so many factors that the answers are difficult to categorize. A researcher needs to avoid steering or prompting the subject to respond in a specific way; otherwise, the results will prove to be unreliable. The researcher will also benefit from gaining a subject’s trust, from empathizing or commiserating with a subject, and from listening without judgment.

Surveys often collect both quantitative and qualitative data. For example, a researcher interviewing people who are incarcerated might receive quantitative data, such as demographics – race, age, sex, that can be analyzed statistically. For example, the researcher might discover that 20 percent of incarcerated people are above the age of 50. The researcher might also collect qualitative data, such as why people take advantage of educational opportunities during their sentence and other explanatory information.

The survey can be carried out online, over the phone, by mail, or face-to-face. When researchers collect data outside a laboratory, library, or workplace setting, they are conducting field research, which is our next topic.

Field Research

The work of sociology rarely happens in limited, confined spaces. Rather, sociologists go out into the world. They meet subjects where they live, work, and play. Field research refers to gathering primary data from a natural environment. To conduct field research, the sociologist must be willing to step into new environments and observe, participate, or experience those worlds. In field work, the sociologists, rather than the subjects, are the ones out of their element.

The researcher interacts with or observes people and gathers data along the way. The key point in field research is that it takes place in the subject’s natural environment, whether it’s a coffee shop or tribal village, a homeless shelter or the DMV, a hospital, airport, mall, or beach resort.

While field research often begins in a specific setting , the study’s purpose is to observe specific behaviors in that setting. Field work is optimal for observing how people think and behave. It seeks to understand why they behave that way. However, researchers may struggle to narrow down cause and effect when there are so many variables floating around in a natural environment. And while field research looks for correlation, its small sample size does not allow for establishing a causal relationship between two variables. Indeed, much of the data gathered in sociology do not identify a cause and effect but a correlation .

Sociology in the Real World

Beyoncé and lady gaga as sociological subjects.

Sociologists have studied Lady Gaga and Beyoncé and their impact on music, movies, social media, fan participation, and social equality. In their studies, researchers have used several research methods including secondary analysis, participant observation, and surveys from concert participants.

In their study, Click, Lee & Holiday (2013) interviewed 45 Lady Gaga fans who utilized social media to communicate with the artist. These fans viewed Lady Gaga as a mirror of themselves and a source of inspiration. Like her, they embrace not being a part of mainstream culture. Many of Lady Gaga’s fans are members of the LGBTQ community. They see the “song “Born This Way” as a rallying cry and answer her calls for “Paws Up” with a physical expression of solidarity—outstretched arms and fingers bent and curled to resemble monster claws.”

Sascha Buchanan (2019) made use of participant observation to study the relationship between two fan groups, that of Beyoncé and that of Rihanna. She observed award shows sponsored by iHeartRadio, MTV EMA, and BET that pit one group against another as they competed for Best Fan Army, Biggest Fans, and FANdemonium. Buchanan argues that the media thus sustains a myth of rivalry between the two most commercially successful Black women vocal artists.

Participant Observation

In 2000, a comic writer named Rodney Rothman wanted an insider’s view of white-collar work. He slipped into the sterile, high-rise offices of a New York “dot com” agency. Every day for two weeks, he pretended to work there. His main purpose was simply to see whether anyone would notice him or challenge his presence. No one did. The receptionist greeted him. The employees smiled and said good morning. Rothman was accepted as part of the team. He even went so far as to claim a desk, inform the receptionist of his whereabouts, and attend a meeting. He published an article about his experience in The New Yorker called “My Fake Job” (2000). Later, he was discredited for allegedly fabricating some details of the story and The New Yorker issued an apology. However, Rothman’s entertaining article still offered fascinating descriptions of the inside workings of a “dot com” company and exemplified the lengths to which a writer, or a sociologist, will go to uncover material.

Rothman had conducted a form of study called participant observation , in which researchers join people and participate in a group’s routine activities for the purpose of observing them within that context. This method lets researchers experience a specific aspect of social life. A researcher might go to great lengths to get a firsthand look into a trend, institution, or behavior. A researcher might work as a waitress in a diner, experience homelessness for several weeks, or ride along with police officers as they patrol their regular beat. Often, these researchers try to blend in seamlessly with the population they study, and they may not disclose their true identity or purpose if they feel it would compromise the results of their research.

At the beginning of a field study, researchers might have a question: “What really goes on in the kitchen of the most popular diner on campus?” or “What is it like to be homeless?” Participant observation is a useful method if the researcher wants to explore a certain environment from the inside.

Field researchers simply want to observe and learn. In such a setting, the researcher will be alert and open minded to whatever happens, recording all observations accurately. Soon, as patterns emerge, questions will become more specific, observations will lead to hypotheses, and hypotheses will guide the researcher in analyzing data and generating results.

In a study of small towns in the United States conducted by sociological researchers John S. Lynd and Helen Merrell Lynd, the team altered their purpose as they gathered data. They initially planned to focus their study on the role of religion in U.S. towns. As they gathered observations, they realized that the effect of industrialization and urbanization was the more relevant topic of this social group. The Lynds did not change their methods, but they revised the purpose of their study.

This shaped the structure of Middletown: A Study in Modern American Culture , their published results (Lynd & Lynd, 1929).

The Lynds were upfront about their mission. The townspeople of Muncie, Indiana, knew why the researchers were in their midst. But some sociologists prefer not to alert people to their presence. The main advantage of covert participant observation is that it allows the researcher access to authentic, natural behaviors of a group’s members. The challenge, however, is gaining access to a setting without disrupting the pattern of others’ behavior. Becoming an inside member of a group, organization, or subculture takes time and effort. Researchers must pretend to be something they are not. The process could involve role playing, making contacts, networking, or applying for a job.

Once inside a group, some researchers spend months or even years pretending to be one of the people they are observing. However, as observers, they cannot get too involved. They must keep their purpose in mind and apply the sociological perspective. That way, they illuminate social patterns that are often unrecognized. Because information gathered during participant observation is mostly qualitative, rather than quantitative, the end results are often descriptive or interpretive. The researcher might present findings in an article or book and describe what he or she witnessed and experienced.

This type of research is what journalist Barbara Ehrenreich conducted for her book Nickel and Dimed . One day over lunch with her editor, Ehrenreich mentioned an idea. How can people exist on minimum-wage work? How do low-income workers get by? she wondered. Someone should do a study . To her surprise, her editor responded, Why don’t you do it?

That’s how Ehrenreich found herself joining the ranks of the working class. For several months, she left her comfortable home and lived and worked among people who lacked, for the most part, higher education and marketable job skills. Undercover, she applied for and worked minimum wage jobs as a waitress, a cleaning woman, a nursing home aide, and a retail chain employee. During her participant observation, she used only her income from those jobs to pay for food, clothing, transportation, and shelter.

She discovered the obvious, that it’s almost impossible to get by on minimum wage work. She also experienced and observed attitudes many middle and upper-class people never think about. She witnessed firsthand the treatment of working class employees. She saw the extreme measures people take to make ends meet and to survive. She described fellow employees who held two or three jobs, worked seven days a week, lived in cars, could not pay to treat chronic health conditions, got randomly fired, submitted to drug tests, and moved in and out of homeless shelters. She brought aspects of that life to light, describing difficult working conditions and the poor treatment that low-wage workers suffer.

The book she wrote upon her return to her real life as a well-paid writer, has been widely read and used in many college classrooms.

Ethnography

Ethnography is the immersion of the researcher in the natural setting of an entire social community to observe and experience their everyday life and culture. The heart of an ethnographic study focuses on how subjects view their own social standing and how they understand themselves in relation to a social group.

An ethnographic study might observe, for example, a small U.S. fishing town, an Inuit community, a village in Thailand, a Buddhist monastery, a private boarding school, or an amusement park. These places all have borders. People live, work, study, or vacation within those borders. People are there for a certain reason and therefore behave in certain ways and respect certain cultural norms. An ethnographer would commit to spending a determined amount of time studying every aspect of the chosen place, taking in as much as possible.

A sociologist studying a tribe in the Amazon might watch the way villagers go about their daily lives and then write a paper about it. To observe a spiritual retreat center, an ethnographer might sign up for a retreat and attend as a guest for an extended stay, observe and record data, and collate the material into results.

Institutional Ethnography

Institutional ethnography is an extension of basic ethnographic research principles that focuses intentionally on everyday concrete social relationships. Developed by Canadian sociologist Dorothy E. Smith (1990), institutional ethnography is often considered a feminist-inspired approach to social analysis and primarily considers women’s experiences within male- dominated societies and power structures. Smith’s work is seen to challenge sociology’s exclusion of women, both academically and in the study of women’s lives (Fenstermaker, n.d.).

Historically, social science research tended to objectify women and ignore their experiences except as viewed from the male perspective. Modern feminists note that describing women, and other marginalized groups, as subordinates helps those in authority maintain their own dominant positions (Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada n.d.). Smith’s three major works explored what she called “the conceptual practices of power” and are still considered seminal works in feminist theory and ethnography (Fensternmaker n.d.).

Sociological Research

The making of middletown: a study in modern u.s. culture.

In 1924, a young married couple named Robert and Helen Lynd undertook an unprecedented ethnography: to apply sociological methods to the study of one U.S. city in order to discover what “ordinary” people in the United States did and believed. Choosing Muncie, Indiana (population about 30,000) as their subject, they moved to the small town and lived there for eighteen months.

Ethnographers had been examining other cultures for decades—groups considered minorities or outsiders—like gangs, immigrants, and the poor. But no one had studied the so-called average American.

Recording interviews and using surveys to gather data, the Lynds objectively described what they observed. Researching existing sources, they compared Muncie in 1890 to the Muncie they observed in 1924. Most Muncie adults, they found, had grown up on farms but now lived in homes inside the city. As a result, the Lynds focused their study on the impact of industrialization and urbanization.

They observed that Muncie was divided into business and working class groups. They defined business class as dealing with abstract concepts and symbols, while working class people used tools to create concrete objects. The two classes led different lives with different goals and hopes. However, the Lynds observed, mass production offered both classes the same amenities. Like wealthy families, the working class was now able to own radios, cars, washing machines, telephones, vacuum cleaners, and refrigerators. This was an emerging material reality of the 1920s.

As the Lynds worked, they divided their manuscript into six chapters: Getting a Living, Making a Home, Training the Young, Using Leisure, Engaging in Religious Practices, and Engaging in Community Activities.

When the study was completed, the Lynds encountered a big problem. The Rockefeller Foundation, which had commissioned the book, claimed it was useless and refused to publish it. The Lynds asked if they could seek a publisher themselves.

Middletown: A Study in Modern American Culture was not only published in 1929 but also became an instant bestseller, a status unheard of for a sociological study. The book sold out six printings in its first year of publication, and has never gone out of print (Caplow, Hicks, & Wattenberg. 2000).

Nothing like it had ever been done before. Middletown was reviewed on the front page of the New York Times. Readers in the 1920s and 1930s identified with the citizens of Muncie, Indiana, but they were equally fascinated by the sociological methods and the use of scientific data to define ordinary people in the United States. The book was proof that social data was important—and interesting—to the U.S. public.

Sometimes a researcher wants to study one specific person or event. A case study is an in-depth analysis of a single event, situation, or individual. To conduct a case study, a researcher examines existing sources like documents and archival records, conducts interviews, engages in direct observation and even participant observation, if possible.

Researchers might use this method to study a single case of a foster child, drug lord, cancer patient, criminal, or rape victim. However, a major criticism of the case study as a method is that while offering depth on a topic, it does not provide enough evidence to form a generalized conclusion. In other words, it is difficult to make universal claims based on just one person, since one person does not verify a pattern. This is why most sociologists do not use case studies as a primary research method.

However, case studies are useful when the single case is unique. In these instances, a single case study can contribute tremendous insight. For example, a feral child, also called “wild child,” is one who grows up isolated from human beings. Feral children grow up without social contact and language, which are elements crucial to a “civilized” child’s development. These children mimic the behaviors and movements of animals, and often invent their own language. There are only about one hundred cases of “feral children” in the world.

As you may imagine, a feral child is a subject of great interest to researchers. Feral children provide unique information about child development because they have grown up outside of the parameters of “normal” growth and nurturing. And since there are very few feral children, the case study is the most appropriate method for researchers to use in studying the subject.

At age three, a Ukranian girl named Oxana Malaya suffered severe parental neglect. She lived in a shed with dogs, and she ate raw meat and scraps. Five years later, a neighbor called authorities and reported seeing a girl who ran on all fours, barking. Officials brought Oxana into society, where she was cared for and taught some human behaviors, but she never became fully socialized. She has been designated as unable to support herself and now lives in a mental institution (Grice 2011). Case studies like this offer a way for sociologists to collect data that may not be obtained by any other method.

Experiments

You have probably tested some of your own personal social theories. “If I study at night and review in the morning, I’ll improve my retention skills.” Or, “If I stop drinking soda, I’ll feel better.” Cause and effect. If this, then that. When you test the theory, your results either prove or disprove your hypothesis.

One way researchers test social theories is by conducting an experiment , meaning they investigate relationships to test a hypothesis—a scientific approach.

There are two main types of experiments: lab-based experiments and natural or field experiments. In a lab setting, the research can be controlled so that more data can be recorded in a limited amount of time. In a natural or field- based experiment, the time it takes to gather the data cannot be controlled but the information might be considered more accurate since it was collected without interference or intervention by the researcher.

As a research method, either type of sociological experiment is useful for testing if-then statements: if a particular thing happens (cause), then another particular thing will result (effect). To set up a lab-based experiment, sociologists create artificial situations that allow them to manipulate variables.

Classically, the sociologist selects a set of people with similar characteristics, such as age, class, race, or education. Those people are divided into two groups. One is the experimental group and the other is the control group. The experimental group is exposed to the independent variable(s) and the control group is not. To test the benefits of tutoring, for example, the sociologist might provide tutoring to the experimental group of students but not to the control group. Then both groups would be tested for differences in performance to see if tutoring had an effect on the experimental group of students. As you can imagine, in a case like this, the researcher would not want to jeopardize the accomplishments of either group of students, so the setting would be somewhat artificial. The test would not be for a grade reflected on their permanent record of a student, for example.

And if a researcher told the students they would be observed as part of a study on measuring the effectiveness of tutoring, the students might not behave naturally. This is called the Hawthorne effect —which occurs when people change their behavior because they know they are being watched as part of a study. The Hawthorne effect is unavoidable in some research studies because sociologists have to make the purpose of the study known. Subjects must be aware that they are being observed, and a certain amount of artificiality may result (Sonnenfeld 1985).

A real-life example will help illustrate the process. In 1971, Frances Heussenstamm, a sociology professor at California State University at Los Angeles, had a theory about police prejudice. To test her theory, she conducted research. She chose fifteen students from three ethnic backgrounds: Black, White, and Hispanic. She chose students who routinely drove to and from campus along Los Angeles freeway routes, and who had had perfect driving records for longer than a year.

Next, she placed a Black Panther bumper sticker on each car. That sticker, a representation of a social value, was the independent variable. In the 1970s, the Black Panthers were a revolutionary group actively fighting racism. Heussenstamm asked the students to follow their normal driving patterns. She wanted to see whether seeming support for the Black Panthers would change how these good drivers were treated by the police patrolling the highways. The dependent variable would be the number of traffic stops/citations.

The first arrest, for an incorrect lane change, was made two hours after the experiment began. One participant was pulled over three times in three days. He quit the study. After seventeen days, the fifteen drivers had collected a total of thirty-three traffic citations. The research was halted. The funding to pay traffic fines had run out, and so had the enthusiasm of the participants (Heussenstamm, 1971).

Secondary Data Analysis

While sociologists often engage in original research studies, they also contribute knowledge to the discipline through secondary data analysis . Secondary data does not result from firsthand research collected from primary sources, but are the already completed work of other researchers or data collected by an agency or organization. Sociologists might study works written by historians, economists, teachers, or early sociologists. They might search through periodicals, newspapers, or magazines, or organizational data from any period in history.

Using available information not only saves time and money but can also add depth to a study. Sociologists often interpret findings in a new way, a way that was not part of an author’s original purpose or intention. To study how women were encouraged to act and behave in the 1960s, for example, a researcher might watch movies, televisions shows, and situation comedies from that period. Or to research changes in behavior and attitudes due to the emergence of television in the late 1950s and early 1960s, a sociologist would rely on new interpretations of secondary data. Decades from now, researchers will most likely conduct similar studies on the advent of mobile phones, the Internet, or social media.

Social scientists also learn by analyzing the research of a variety of agencies. Governmental departments and global groups, like the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics or the World Health Organization (WHO), publish studies with findings that are useful to sociologists. A public statistic like the foreclosure rate might be useful for studying the effects of a recession. A racial demographic profile might be compared with data on education funding to examine the resources accessible by different groups.

One of the advantages of secondary data like old movies or WHO statistics is that it is nonreactive research (or unobtrusive research), meaning that it does not involve direct contact with subjects and will not alter or influence people’s behaviors. Unlike studies requiring direct contact with people, using previously published data does not require entering a population and the investment and risks inherent in that research process.

Using available data does have its challenges. Public records are not always easy to access. A researcher will need to do some legwork to track them down and gain access to records. To guide the search through a vast library of materials and avoid wasting time reading unrelated sources, sociologists employ content analysis , applying a systematic approach to record and value information gleaned from secondary data as they relate to the study at hand.

Also, in some cases, there is no way to verify the accuracy of existing data. It is easy to count how many drunk drivers, for example, are pulled over by the police. But how many are not? While it’s possible to discover the percentage of teenage students who drop out of high school, it might be more challenging to determine the number who return to school or get their GED later.

Another problem arises when data are unavailable in the exact form needed or do not survey the topic from the precise angle the researcher seeks. For example, the average salaries paid to professors at a public school is public record. But these figures do not necessarily reveal how long it took each professor to reach the salary range, what their educational backgrounds are, or how long they’ve been teaching.

When conducting content analysis, it is important to consider the date of publication of an existing source and to take into account attitudes and common cultural ideals that may have influenced the research. For example, when Robert S. Lynd and Helen Merrell Lynd gathered research in the 1920s, attitudes and cultural norms were vastly different then than they are now. Beliefs about gender roles, race, education, and work have changed significantly since then. At the time, the study’s purpose was to reveal insights about small U.S. communities. Today, it is an illustration of 1920s attitudes and values.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Introduction to Sociology 3e

- Publication date: Jun 3, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/2-2-research-methods

© Jan 18, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Quantitative Research? | Definition, Uses & Methods

What Is Quantitative Research? | Definition, Uses & Methods

Published on June 12, 2020 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Quantitative research is the process of collecting and analyzing numerical data. It can be used to find patterns and averages, make predictions, test causal relationships, and generalize results to wider populations.

Quantitative research is the opposite of qualitative research , which involves collecting and analyzing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio).

Quantitative research is widely used in the natural and social sciences: biology, chemistry, psychology, economics, sociology, marketing, etc.

- What is the demographic makeup of Singapore in 2020?

- How has the average temperature changed globally over the last century?

- Does environmental pollution affect the prevalence of honey bees?

- Does working from home increase productivity for people with long commutes?

Table of contents

Quantitative research methods, quantitative data analysis, advantages of quantitative research, disadvantages of quantitative research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about quantitative research.

You can use quantitative research methods for descriptive, correlational or experimental research.

- In descriptive research , you simply seek an overall summary of your study variables.

- In correlational research , you investigate relationships between your study variables.

- In experimental research , you systematically examine whether there is a cause-and-effect relationship between variables.

Correlational and experimental research can both be used to formally test hypotheses , or predictions, using statistics. The results may be generalized to broader populations based on the sampling method used.

To collect quantitative data, you will often need to use operational definitions that translate abstract concepts (e.g., mood) into observable and quantifiable measures (e.g., self-ratings of feelings and energy levels).

Note that quantitative research is at risk for certain research biases , including information bias , omitted variable bias , sampling bias , or selection bias . Be sure that you’re aware of potential biases as you collect and analyze your data to prevent them from impacting your work too much.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Once data is collected, you may need to process it before it can be analyzed. For example, survey and test data may need to be transformed from words to numbers. Then, you can use statistical analysis to answer your research questions .

Descriptive statistics will give you a summary of your data and include measures of averages and variability. You can also use graphs, scatter plots and frequency tables to visualize your data and check for any trends or outliers.

Using inferential statistics , you can make predictions or generalizations based on your data. You can test your hypothesis or use your sample data to estimate the population parameter .

First, you use descriptive statistics to get a summary of the data. You find the mean (average) and the mode (most frequent rating) of procrastination of the two groups, and plot the data to see if there are any outliers.

You can also assess the reliability and validity of your data collection methods to indicate how consistently and accurately your methods actually measured what you wanted them to.

Quantitative research is often used to standardize data collection and generalize findings . Strengths of this approach include:

- Replication

Repeating the study is possible because of standardized data collection protocols and tangible definitions of abstract concepts.

- Direct comparisons of results

The study can be reproduced in other cultural settings, times or with different groups of participants. Results can be compared statistically.

- Large samples

Data from large samples can be processed and analyzed using reliable and consistent procedures through quantitative data analysis.

- Hypothesis testing

Using formalized and established hypothesis testing procedures means that you have to carefully consider and report your research variables, predictions, data collection and testing methods before coming to a conclusion.

Despite the benefits of quantitative research, it is sometimes inadequate in explaining complex research topics. Its limitations include:

- Superficiality

Using precise and restrictive operational definitions may inadequately represent complex concepts. For example, the concept of mood may be represented with just a number in quantitative research, but explained with elaboration in qualitative research.

- Narrow focus

Predetermined variables and measurement procedures can mean that you ignore other relevant observations.

- Structural bias

Despite standardized procedures, structural biases can still affect quantitative research. Missing data , imprecise measurements or inappropriate sampling methods are biases that can lead to the wrong conclusions.

- Lack of context

Quantitative research often uses unnatural settings like laboratories or fails to consider historical and cultural contexts that may affect data collection and results.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Chi square goodness of fit test

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

In mixed methods research , you use both qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis methods to answer your research question .

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organizations.

Operationalization means turning abstract conceptual ideas into measurable observations.

For example, the concept of social anxiety isn’t directly observable, but it can be operationally defined in terms of self-rating scores, behavioral avoidance of crowded places, or physical anxiety symptoms in social situations.

Before collecting data , it’s important to consider how you will operationalize the variables that you want to measure.

Reliability and validity are both about how well a method measures something:

- Reliability refers to the consistency of a measure (whether the results can be reproduced under the same conditions).

- Validity refers to the accuracy of a measure (whether the results really do represent what they are supposed to measure).

If you are doing experimental research, you also have to consider the internal and external validity of your experiment.

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics. It is used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses , by calculating how likely it is that a pattern or relationship between variables could have arisen by chance.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, June 22). What Is Quantitative Research? | Definition, Uses & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved April 13, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/quantitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, descriptive statistics | definitions, types, examples, inferential statistics | an easy introduction & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

A Quick Guide to Quantitative Research in the Social Sciences

(11 reviews)

Christine Davies, Carmarthen, Wales

Copyright Year: 2020

Last Update: 2021

Publisher: University of Wales Trinity Saint David

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Learn more about reviews.

Reviewed by Tiffany Kindratt, Assistant Professor, University of Texas at Arlington on 3/9/24

The text provides a brief overview of quantitative research topics that is geared towards research in the fields of education, sociology, business, and nursing. The author acknowledges that the textbook is not a comprehensive resource but offers... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 3 see less

The text provides a brief overview of quantitative research topics that is geared towards research in the fields of education, sociology, business, and nursing. The author acknowledges that the textbook is not a comprehensive resource but offers references to other resources that can be used to deepen the knowledge. The text does not include a glossary or index. The references in the figures for each chapter are not included in the reference section. It would be helpful to include those.

Content Accuracy rating: 4

Overall, the text is accurate. For example, Figure 1 on page 6 provides a clear overview of the research process. It includes general definitions of primary and secondary research. It would be helpful to include more details to explain some of the examples before they are presented. For instance, the example on page 5 was unclear how it pertains to the literature review section.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 4

In general, the text is relevant and up-to-date. The text includes many inferences of moving from qualitative to quantitative analysis. This was surprising to me as a quantitative researcher. The author mentions that moving from a qualitative to quantitative approach should only be done when needed. As a predominantly quantitative researcher, I would not advice those interested in transitioning to using a qualitative approach that qualitative research would enhance their research—not something that should only be done if you have to.

Clarity rating: 4

The text is written in a clear manner. It would be helpful to the reader if there was a description of the tables and figures in the text before they are presented.

Consistency rating: 4

The framework for each chapter and terminology used are consistent.

Modularity rating: 4

The text is clearly divided into sections within each chapter. Overall, the chapters are a similar brief length except for the chapter on data analysis, which is much more comprehensive than others.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 4

The topics in the text are presented in a clear and logical order. The order of the text follows the conventional research methodology in social sciences.

Interface rating: 5

I did not encounter any interface issues when reviewing this text. All links worked and there were no distortions of the images or charts that may confuse the reader.

Grammatical Errors rating: 3

There are some grammatical/typographical errors throughout. Of note, for Section 5 in the table of contents. “The” should be capitalized to start the title. In the title for Table 3, the “t” in typical should be capitalized.

Cultural Relevance rating: 4

The examples are culturally relevant. The text is geared towards learners in the UK, but examples are relevant for use in other countries (i.e., United States). I did not see any examples that may be considered culturally insensitive or offensive in any way.

I teach a course on research methods in a Bachelor of Science in Public Health program. I would consider using some of the text, particularly in the analysis chapter to supplement the current textbook in the future.

Reviewed by Finn Bell, Assistant Professor, University of Michigan, Dearborn on 1/3/24

For it being a quick guide and only 26 pages, it is very comprehensive, but it does not include an index or glossary. read more

For it being a quick guide and only 26 pages, it is very comprehensive, but it does not include an index or glossary.

Content Accuracy rating: 5

As far as I can tell, the text is accurate, error-free and unbiased.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 5

This text is up-to-date, and given the content, unlikely to become obsolete any time soon.

Clarity rating: 5

The text is very clear and accessible.

Consistency rating: 5

The text is internally consistent.

Modularity rating: 5

Given how short the text is, it seems unnecessary to divide it into smaller readings, nonetheless, it is clearly labelled such that an instructor could do so.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 5

The text is well-organized and brings readers through basic quantitative methods in a logical, clear fashion.

Easy to navigate. Only one table that is split between pages, but not in a way that is confusing.

Grammatical Errors rating: 5

There were no noticeable grammatical errors.

The examples in this book don't give enough information to rate this effectively.

This text is truly a very quick guide at only 26 double-spaced pages. Nonetheless, Davies packs a lot of information on the basics of quantitative research methods into this text, in an engaging way with many examples of the concepts presented. This guide is more of a brief how-to that takes readers as far as how to select statistical tests. While it would be impossible to fully learn quantitative research from such a short text, of course, this resource provides a great introduction, overview, and refresher for program evaluation courses.

Reviewed by Shari Fedorowicz, Adjunct Professor, Bridgewater State University on 12/16/22

The text is indeed a quick guide for utilizing quantitative research. Appropriate and effective examples and diagrams were used throughout the text. The author clearly differentiates between use of quantitative and qualitative research providing... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 5 see less

The text is indeed a quick guide for utilizing quantitative research. Appropriate and effective examples and diagrams were used throughout the text. The author clearly differentiates between use of quantitative and qualitative research providing the reader with the ability to distinguish two terms that frequently get confused. In addition, links and outside resources are provided to deepen the understanding as an option for the reader. The use of these links, coupled with diagrams and examples make this text comprehensive.

The content is mostly accurate. Given that it is a quick guide, the author chose a good selection of which types of research designs to include. However, some are not provided. For example, correlational or cross-correlational research is omitted and is not discussed in Section 3, but is used as a statistical example in the last section.

Examples utilized were appropriate and associated with terms adding value to the learning. The tables that included differentiation between types of statistical tests along with a parametric/nonparametric table were useful and relevant.

The purpose to the text and how to use this guide book is stated clearly and is established up front. The author is also very clear regarding the skill level of the user. Adding to the clarity are the tables with terms, definitions, and examples to help the reader unpack the concepts. The content related to the terms was succinct, direct, and clear. Many times examples or figures were used to supplement the narrative.

The text is consistent throughout from contents to references. Within each section of the text, the introductory paragraph under each section provides a clear understanding regarding what will be discussed in each section. The layout is consistent for each section and easy to follow.

The contents are visible and address each section of the text. A total of seven sections, including a reference section, is in the contents. Each section is outlined by what will be discussed in the contents. In addition, within each section, a heading is provided to direct the reader to the subtopic under each section.

The text is well-organized and segues appropriately. I would have liked to have seen an introductory section giving a narrative overview of what is in each section. This would provide the reader with the ability to get a preliminary glimpse into each upcoming sections and topics that are covered.

The book was easy to navigate and well-organized. Examples are presented in one color, links in another and last, figures and tables. The visuals supplemented the reading and placed appropriately. This provides an opportunity for the reader to unpack the reading by use of visuals and examples.

No significant grammatical errors.

Cultural Relevance rating: 5

The text is not offensive or culturally insensitive. Examples were inclusive of various races, ethnicities, and backgrounds.

This quick guide is a beneficial text to assist in unpacking the learning related to quantitative statistics. I would use this book to complement my instruction and lessons, or use this book as a main text with supplemental statistical problems and formulas. References to statistical programs were appropriate and were useful. The text did exactly what was stated up front in that it is a direct guide to quantitative statistics. It is well-written and to the point with content areas easy to locate by topic.

Reviewed by Sarah Capello, Assistant Professor, Radford University on 1/18/22

The text claims to provide "quick and simple advice on quantitative aspects of research in social sciences," which it does. There is no index or glossary, although vocabulary words are bolded and defined throughout the text. read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 4 see less

The text claims to provide "quick and simple advice on quantitative aspects of research in social sciences," which it does. There is no index or glossary, although vocabulary words are bolded and defined throughout the text.

The content is mostly accurate. I would have preferred a few nuances to be hashed out a bit further to avoid potential reader confusion or misunderstanding of the concepts presented.

The content is current; however, some of the references cited in the text are outdated. Newer editions of those texts exist.

The text is very accessible and readable for a variety of audiences. Key terms are well-defined.

There are no content discrepancies within the text. The author even uses similarly shaped graphics for recurring purposes throughout the text (e.g., arrow call outs for further reading, rectangle call outs for examples).

The content is chunked nicely by topics and sections. If it were used for a course, it would be easy to assign different sections of the text for homework, etc. without confusing the reader if the instructor chose to present the content in a different order.

The author follows the structure of the research process. The organization of the text is easy to follow and comprehend.

All of the supplementary images (e.g., tables and figures) were beneficial to the reader and enhanced the text.

There are no significant grammatical errors.

I did not find any culturally offensive or insensitive references in the text.

This text does the difficult job of introducing the complicated concepts and processes of quantitative research in a quick and easy reference guide fairly well. I would not depend solely on this text to teach students about quantitative research, but it could be a good jumping off point for those who have no prior knowledge on this subject or those who need a gentle introduction before diving in to more advanced and complex readings of quantitative research methods.

Reviewed by J. Marlie Henry, Adjunct Faculty, University of Saint Francis on 12/9/21

Considering the length of this guide, this does a good job of addressing major areas that typically need to be addressed. There is a contents section. The guide does seem to be organized accordingly with appropriate alignment and logical flow of... read more

Considering the length of this guide, this does a good job of addressing major areas that typically need to be addressed. There is a contents section. The guide does seem to be organized accordingly with appropriate alignment and logical flow of thought. There is no glossary but, for a guide of this length, a glossary does not seem like it would enhance the guide significantly.

The content is relatively accurate. Expanding the content a bit more or explaining that the methods and designs presented are not entirely inclusive would help. As there are different schools of thought regarding what should/should not be included in terms of these designs and methods, simply bringing attention to that and explaining a bit more would help.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 3

This content needs to be updated. Most of the sources cited are seven or more years old. Even more, it would be helpful to see more currently relevant examples. Some of the source authors such as Andy Field provide very interesting and dynamic instruction in general, but they have much more current information available.

The language used is clear and appropriate. Unnecessary jargon is not used. The intent is clear- to communicate simply in a straightforward manner.

The guide seems to be internally consistent in terms of terminology and framework. There do not seem to be issues in this area. Terminology is internally consistent.

For a guide of this length, the author structured this logically into sections. This guide could be adopted in whole or by section with limited modifications. Courses with fewer than seven modules could also logically group some of the sections.

This guide does present with logical organization. The topics presented are conceptually sequenced in a manner that helps learners build logically on prior conceptualization. This also provides a simple conceptual framework for instructors to guide learners through the process.

Interface rating: 4

The visuals themselves are simple, but they are clear and understandable without distracting the learner. The purpose is clear- that of learning rather than visuals for the sake of visuals. Likewise, navigation is clear and without issues beyond a broken link (the last source noted in the references).

This guide seems to be free of grammatical errors.

It would be interesting to see more cultural integration in a guide of this nature, but the guide is not culturally insensitive or offensive in any way. The language used seems to be consistent with APA's guidelines for unbiased language.

Reviewed by Heng Yu-Ku, Professor, University of Northern Colorado on 5/13/21

The text covers all areas and ideas appropriately and provides practical tables, charts, and examples throughout the text. I would suggest the author also provides a complete research proposal at the end of Section 3 (page 10) and a comprehensive... read more

The text covers all areas and ideas appropriately and provides practical tables, charts, and examples throughout the text. I would suggest the author also provides a complete research proposal at the end of Section 3 (page 10) and a comprehensive research study as an Appendix after section 7 (page 26) to help readers comprehend information better.

For the most part, the content is accurate and unbiased. However, the author only includes four types of research designs used on the social sciences that contain quantitative elements: 1. Mixed method, 2) Case study, 3) Quasi-experiment, and 3) Action research. I wonder why the correlational research is not included as another type of quantitative research design as it has been introduced and emphasized in section 6 by the author.

I believe the content is up-to-date and that necessary updates will be relatively easy and straightforward to implement.

The text is easy to read and provides adequate context for any technical terminology used. However, the author could provide more detailed information about estimating the minimum sample size but not just refer the readers to use the online sample calculators at a different website.

The text is internally consistent in terms of terminology and framework. The author provides the right amount of information with additional information or resources for the readers.

The text includes seven sections. Therefore, it is easier for the instructor to allocate or divide the content into different weeks of instruction within the course.

Yes, the topics in the text are presented in a logical and clear fashion. The author provides clear and precise terminologies, summarizes important content in Table or Figure forms, and offers examples in each section for readers to check their understanding.

The interface of the book is consistent and clear, and all the images and charts provided in the book are appropriate. However, I did encounter some navigation problems as a couple of links are not working or requires permission to access those (pages 10 and 27).

No grammatical errors were found.

No culturally incentive or offensive in its language and the examples provided were found.

As the book title stated, this book provides “A Quick Guide to Quantitative Research in Social Science. It offers easy-to-read information and introduces the readers to the research process, such as research questions, research paradigms, research process, research designs, research methods, data collection, data analysis, and data discussion. However, some links are not working or need permissions to access them (pages 10 and 27).

Reviewed by Hsiao-Chin Kuo, Assistant Professor, Northeastern Illinois University on 4/26/21, updated 4/28/21

As a quick guide, it covers basic concepts related to quantitative research. It starts with WHY quantitative research with regard to asking research questions and considering research paradigms, then provides an overview of research design and... read more

As a quick guide, it covers basic concepts related to quantitative research. It starts with WHY quantitative research with regard to asking research questions and considering research paradigms, then provides an overview of research design and process, discusses methods, data collection and analysis, and ends with writing a research report. It also identifies its target readers/users as those begins to explore quantitative research. It would be helpful to include more examples for readers/users who are new to quantitative research.

Its content is mostly accurate and no bias given its nature as a quick guide. Yet, it is also quite simplified, such as its explanations of mixed methods, case study, quasi-experimental research, and action research. It provides resources for extended reading, yet more recent works will be helpful.

The book is relevant given its nature as a quick guide. It would be helpful to provide more recent works in its resources for extended reading, such as the section for Survey Research (p. 12). It would also be helpful to include more information to introduce common tools and software for statistical analysis.

The book is written with clear and understandable language. Important terms and concepts are presented with plain explanations and examples. Figures and tables are also presented to support its clarity. For example, Table 4 (p. 20) gives an easy-to-follow overview of different statistical tests.

The framework is very consistent with key points, further explanations, examples, and resources for extended reading. The sample studies are presented following the layout of the content, such as research questions, design and methods, and analysis. These examples help reinforce readers' understanding of these common research elements.

The book is divided into seven chapters. Each chapter clearly discusses an aspect of quantitative research. It can be easily divided into modules for a class or for a theme in a research method class. Chapters are short and provides additional resources for extended reading.

The topics in the chapters are presented in a logical and clear structure. It is easy to follow to a degree. Though, it would be also helpful to include the chapter number and title in the header next to its page number.

The text is easy to navigate. Most of the figures and tables are displayed clearly. Yet, there are several sections with empty space that is a bit confusing in the beginning. Again, it can be helpful to include the chapter number/title next to its page number.

Grammatical Errors rating: 4

No major grammatical errors were found.

There are no cultural insensitivities noted.

Given the nature and purpose of this book, as a quick guide, it provides readers a quick reference for important concepts and terms related to quantitative research. Because this book is quite short (27 pages), it can be used as an overview/preview about quantitative research. Teacher's facilitation/input and extended readings will be needed for a deeper learning and discussion about aspects of quantitative research.

Reviewed by Yang Cheng, Assistant Professor, North Carolina State University on 1/6/21

It covers the most important topics such as research progress, resources, measurement, and analysis of the data. read more

It covers the most important topics such as research progress, resources, measurement, and analysis of the data.

The book accurately describes the types of research methods such as mixed-method, quasi-experiment, and case study. It talks about the research proposal and key differences between statistical analyses as well.

The book pinpointed the significance of running a quantitative research method and its relevance to the field of social science.

The book clearly tells us the differences between types of quantitative methods and the steps of running quantitative research for students.

The book is consistent in terms of terminologies such as research methods or types of statistical analysis.

It addresses the headlines and subheadlines very well and each subheading should be necessary for readers.

The book was organized very well to illustrate the topic of quantitative methods in the field of social science.

The pictures within the book could be further developed to describe the key concepts vividly.

The textbook contains no grammatical errors.

It is not culturally offensive in any way.

Overall, this is a simple and quick guide for this important topic. It should be valuable for undergraduate students who would like to learn more about research methods.

Reviewed by Pierre Lu, Associate Professor, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley on 11/20/20

As a quick guide to quantitative research in social sciences, the text covers most ideas and areas. read more

As a quick guide to quantitative research in social sciences, the text covers most ideas and areas.

Mostly accurate content.

As a quick guide, content is highly relevant.

Succinct and clear.

Internally, the text is consistent in terms of terminology used.

The text is easily and readily divisible into smaller sections that can be used as assignments.

I like that there are examples throughout the book.

Easy to read. No interface/ navigation problems.

No grammatical errors detected.

I am not aware of the culturally insensitive description. After all, this is a methodology book.