Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- NEWS & VIEWS FORUM

- 10 February 2020

Scrutinizing the effects of digital technology on mental health

- Jonathan Haidt &

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

You have full access to this article via your institution.

The topic in brief

• There is an ongoing debate about whether social media and the use of digital devices are detrimental to mental health.

• Adolescents tend to be heavy users of these devices, and especially of social media.

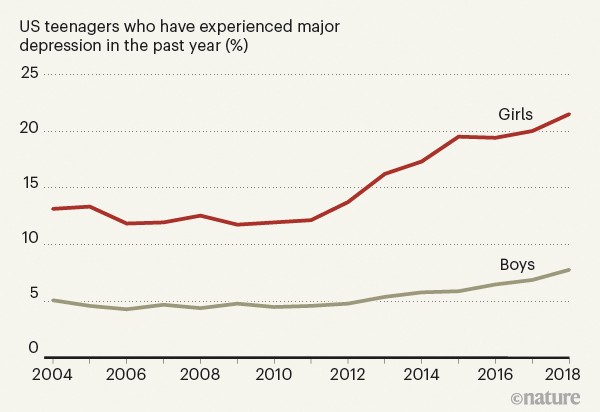

• Rates of teenage depression began to rise around 2012, when adolescent use of social media became common (Fig. 1).

• Some evidence indicates that frequent users of social media have higher rates of depression and anxiety than do light users.

• But perhaps digital devices could provide a way of gathering data about mental health in a systematic way, and make interventions more timely.

Figure 1 | Depression on the rise. Rates of depression among teenagers in the United States have increased steadily since 2012. Rates are higher and are increasing more rapidly for girls than for boys. Some researchers think that social media is the cause of this increase, whereas others see social media as a way of tackling it. (Data taken from the US National Survey on Drug Use and Health, Table 11.2b; go.nature.com/3ayjaww )

JONATHAN HAIDT: A guilty verdict

A sudden increase in the rates of depression, anxiety and self-harm was seen in adolescents — particularly girls — in the United States and the United Kingdom around 2012 or 2013 (see go.nature.com/2up38hw ). Only one suspect was in the right place at the right time to account for this sudden change: social media. Its use by teenagers increased most quickly between 2009 and 2011, by which point two-thirds of 15–17-year-olds were using it on a daily basis 1 . Some researchers defend social media, arguing that there is only circumstantial evidence for its role in mental-health problems 2 , 3 . And, indeed, several studies 2 , 3 show that there is only a small correlation between time spent on screens and bad mental-health outcomes. However, I present three arguments against this defence.

First, the papers that report small or null effects usually focus on ‘screen time’, but it is not films or video chats with friends that damage mental health. When research papers allow us to zoom in on social media, rather than looking at screen time as a whole, the correlations with depression are larger, and they are larger still when we look specifically at girls ( go.nature.com/2u74der ). The sex difference is robust, and there are several likely causes for it. Girls use social media much more than do boys (who, in turn, spend more of their time gaming). And, for girls more than boys, social life and status tend to revolve around intimacy and inclusion versus exclusion 4 , making them more vulnerable to both the ‘fear of missing out’ and the relational aggression that social media facilitates.

Second, although correlational studies can provide only circumstantial evidence, most of the experiments published in recent years have found evidence of causation ( go.nature.com/2u74der ). In these studies, people are randomly assigned to groups that are asked to continue using social media or to reduce their use substantially. After a few weeks, people who reduce their use generally report an improvement in mood or a reduction in loneliness or symptoms of depression.

The best way forward

Third, many researchers seem to be thinking about social media as if it were sugar: safe in small to moderate quantities, and harmful only if teenagers consume large quantities. But, unlike sugar, social media does not act just on those who consume it. It has radically transformed the nature of peer relationships, family relationships and daily activities 5 . When most of the 11-year-olds in a class are on Instagram (as was the case in my son’s school), there can be pervasive effects on everyone. Children who opt out can find themselves isolated. A simple dose–response model cannot capture the full effects of social media, yet nearly all of the debate among researchers so far has been over the size of the dose–response effect. To cite just one suggestive finding of what lies beyond that model: network effects for depression and anxiety are large, and bad mental health spreads more contagiously between women than between men 6 .

In conclusion, digital media in general undoubtedly has many beneficial uses, including the treatment of mental illness. But if you focus on social media, you’ll find stronger evidence of harm, and less exculpatory evidence, especially for its millions of under-age users.

What should we do while researchers hash out the meaning of these conflicting findings? I would urge a focus on middle schools (roughly 11–13-year-olds in the United States), both for researchers and policymakers. Any US state could quickly conduct an informative experiment beginning this September: randomly assign a portion of school districts to ban smartphone access for students in middle school, while strongly encouraging parents to prevent their children from opening social-media accounts until they begin high school (at around 14). Within 2 years, we would know whether the policy reversed the otherwise steady rise of mental-health problems among middle-school students, and whether it also improved classroom dynamics (as rated by teachers) and test scores. Such system-wide and cross-school interventions would be an excellent way to study the emergent effects of social media on the social lives and mental health of today’s adolescents.

NICK ALLEN: Use digital technology to our advantage

It is appealing to condemn social media out of hand on the basis of the — generally rather poor-quality and inconsistent — evidence suggesting that its use is associated with mental-health problems 7 . But focusing only on its potential harmful effects is comparable to proposing that the only question to ask about cars is whether people can die driving them. The harmful effects might be real, but they don’t tell the full story. The task of research should be to understand what patterns of digital-device and social-media use can lead to beneficial versus harmful effects 7 , and to inform evidence-based approaches to policy, education and regulation.

Long-standing problems have hampered our efforts to improve access to, and the quality of, mental-health services and support. Digital technology has the potential to address some of these challenges. For instance, consider the challenges associated with collecting data on human behaviour. Assessment in mental-health care and research relies almost exclusively on self-reporting, but the resulting data are subjective and burdensome to collect. As a result, assessments are conducted so infrequently that they do not provide insights into the temporal dynamics of symptoms, which can be crucial for both diagnosis and treatment planning.

By contrast, mobile phones and other Internet-connected devices provide an opportunity to continuously collect objective information on behaviour in the context of people’s real lives, generating a rich data set that can provide insight into the extent and timing of mental-health needs in individuals 8 , 9 . By building apps that can track our digital exhaust (the data generated by our everyday digital lives, including our social-media use), we can gain insights into aspects of behaviour that are well-established building blocks of mental health and illness, such as mood, social communication, sleep and physical activity.

Stress and the city

These data can, in turn, be used to empower individuals, by giving them actionable insights into patterns of behaviour that might otherwise have remained unseen. For example, subtle shifts in patterns of sleep or social communication can provide early warning signs of deteriorating mental health. Data on these patterns can be used to alert people to the need for self-management before the patterns — and the associated symptoms — become more severe. Individuals can also choose to share these data with health professionals or researchers. For instance, in the Our Data Helps initiative, individuals who have experienced a suicidal crisis, or the relatives of those who have died by suicide, can donate their digital data to research into suicide risk.

Because mobile devices are ever-present in people’s lives, they offer an opportunity to provide interventions that are timely, personalized and scalable. Currently, mental-health services are mainly provided through a century-old model in which they are made available at times chosen by the mental-health practitioner, rather than at the person’s time of greatest need. But Internet-connected devices are facilitating the development of a wave of ‘just-in-time’ interventions 10 for mental-health care and support.

A compelling example of these interventions involves short-term risk for suicide 9 , 11 — for which early detection could save many lives. Most of the effective approaches to suicide prevention work by interrupting suicidal actions and supporting alternative methods of coping at the moment of greatest risk. If these moments can be detected in an individual’s digital exhaust, a wide range of intervention options become available, from providing information about coping skills and social support, to the initiation of crisis responses. So far, just-in-time approaches have been applied mainly to behaviours such as eating or substance abuse 8 . But with the development of an appropriate research base, these approaches have the potential to provide a major advance in our ability to respond to, and prevent, mental-health crises.

These advantages are particularly relevant to teenagers. Because of their extensive use of digital devices, adolescents are especially vulnerable to the devices’ risks and burdens. And, given the increases in mental-health problems in this age group, teens would also benefit most from improvements in mental-health prevention and treatment. If we use the social and data-gathering functions of Internet-connected devices in the right ways, we might achieve breakthroughs in our ability to improve mental health and well-being.

Nature 578 , 226-227 (2020)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-00296-x

Twenge, J. M., Martin, G. N. & Spitzberg, B. H. Psychol. Pop. Media Culture 8 , 329–345 (2019).

Article Google Scholar

Orben, A. & Przybylski, A. K. Nature Hum. Behav. 3 , 173–182 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Odgers, C. L. & Jensen, M. R. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13190 (2020).

Maccoby, E. E. The Two Sexes: Growing Up Apart, Coming Together Ch. 2 (Harvard Univ. Press, 1999).

Google Scholar

Nesi, J., Choukas-Bradley, S. & Prinstein, M. J. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 21 , 267–294 (2018).

Rosenquist, J. N., Fowler, J. H. & Christakis, N. A. Molec. Psychiatry 16 , 273–281 (2011).

Orben, A. Social Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01825-4 (2020).

Mohr, D. C., Zhang, M. & Schueller, S. M. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 13 , 23–47 (2017).

Nelson, B. W. & Allen, N. B. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 13 , 718–733 (2018).

Nahum-Shani, I. et al. Ann. Behav. Med. 52 , 446–462 (2018).

Allen, N. B., Nelson, B. W., Brent, D. & Auerbach, R. P. J. Affect. Disord. 250 , 163–169 (2019).

Download references

Reprints and permissions

Competing Interests

N.A. has an equity interest in Ksana Health, a company he co-founded and which has the sole commercial licence for certain versions of the Effortless Assessment of Risk States (EARS) mobile-phone application and some related EARS tools. This intellectual property was developed as part of his research at the University of Oregon’s Center for Digital Mental Health (CDMH).

Related Articles

See all News & Views

- Human behaviour

Scientists under arrest: the researchers taking action over climate change

News Feature 21 FEB 24

Gender bias is more exaggerated in online images than in text

News & Views 14 FEB 24

Online images amplify gender bias

Article 14 FEB 24

Circulating myeloid-derived MMP8 in stress susceptibility and depression

Article 07 FEB 24

Only 0.5% of neuroscience studies look at women’s health. Here’s how to change that

World View 21 NOV 23

Sustained antidepressant effect of ketamine through NMDAR trapping in the LHb

Article 18 OCT 23

Artificial intelligence and illusions of understanding in scientific research

Perspective 06 MAR 24

Economists count the cost of ‘risky’ science

Career News 06 FEB 24

Backend/ DevOps Engineer – National Facility for Data Handling and Analysis

APPLICATION CLOSING DATE: April 2nd, 2024. About the institute Human Technopole (HT) is a new interdisciplinary life science research institute, cr...

Human Technopole

Professorship for Pneumology (W3)

The Jena University Hospital (JUH) invites applications for a Professorship for Pneumology (W3) to be filled at the earliest possible date. The pro...

07743 Jena, Thüringen (DE)

Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena

Faculty Positions at Great Bay University, China

We are now seeking outstanding candidates in Physics, Chemistry and Physical Sciences.

Dongguan, Guangdong, China

Great Bay University, China (GBU)

Tenure-Track Assistant Professor to the rank of Associate Professor in computational biology

UNIL is a leading international teaching and research institution, with over 5,000 employees and 15,500 students split between its Dorigny campus, ...

Lausanne, Canton of Vaud (CH)

University of Lausanne (UNIL)

Assistant Scientist/Professor in Rare Disease Research, Sanford Research

Assistant Scientist/Professor in Rare Disease Research, Sanford Research Sanford Research invites applications for full-time faculty at the rank of...

Sioux Falls, South Dakota

Sanford Research

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 15 February 2023

The impact of food insecurity on health outcomes: empirical evidence from sub-Saharan African countries

- Sisay Demissew Beyene ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7347-4168 1

BMC Public Health volume 23 , Article number: 338 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

17k Accesses

9 Citations

7 Altmetric

Metrics details

Food insecurity adversely affects human health, which means food security and nutrition are crucial to improving people’s health outcomes. Both food insecurity and health outcomes are the policy and agenda of the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). However, there is a lack of macro-level empirical studies (Macro-level study means studies at the broadest level using variables that represent a given country or the whole population of a country or economy as a whole. For example, if the urban population (% of the total population) of XYZ country is 30%, it is used as a proxy variable to represent represent country's urbanization level. Empirical study implies studies that employ the econometrics method, which is the application of math and statistics.) concerning the relationship between food insecurity and health outcomes in sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries though the region is highly affected by food insecurity and its related health problems. Therefore, this study aims to examine the impact of food insecurity on life expectancy and infant mortality in SSA countries.

The study was conducted for the whole population of 31 sampled SSA countries selected based on data availability. The study uses secondary data collected online from the databases of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), and the World Bank (WB). The study uses yearly balanced data from 2001 to 2018. This study employs a multicountry panel data analysis and several estimation techniques; it employs Driscoll-Kraay standard errors (DKSE), a generalized method of momentum (GMM), fixed effects (FE), and the Granger causality test.

A 1% increment in people’s prevalence for undernourishment reduces their life expectancy by 0.00348 percentage points (PPs). However, life expectancy rises by 0.00317 PPs with every 1% increase in average dietary energy supply. A 1% rise in the prevalence of undernourishment increases infant mortality by 0.0119 PPs. However, a 1% increment in average dietary energy supply reduces infant mortality by 0.0139 PPs.

Conclusions

Food insecurity harms the health status of SSA countries, but food security impacts in the reverse direction. This implies that to meet SDG 3.2, SSA should ensure food security.

Peer Review reports

Food security is essential to people’s health and well-being [ 1 ]. Further, the World Health Organization (WHO) argues that health is wealth and poor health is an integral part of poverty; governments should actively seek to preserve their people’s lives and reduce the incidence of unnecessary mortality and avoidable illnesses [ 2 ]. However, lack of food is one of the factors which affect health outcomes. Concerning this, the Food Research and Action Center noted that the social determinants of health, such as poverty and food insecurity, are associated with some of the most severe and costly health problems in a nation [ 3 ].

According to the FAO, the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), and the World Food Programme (WFP), food insecurity is defined as "A situation that exists when people lack secure access to sufficient amounts of safe and nutritious food for normal growth and development and an active and healthy life" ([ 4 ]; p50). It is generally believed that food security and nutrition are crucial to improving human health and development. Studies show that millions of people live in food insecurity, which is one of the main risks to human health. Around one in four people globally (1.9 billion people) were moderately or severely food insecure in 2017 and the greatest numbers were in SSA and South Asia. Around 9.2% of the world's population was severely food insecure in 2018. Food insecurity is highest in SSA countries, where nearly one-third are defined as severely insecure [ 5 ]. Similarly, 11% (820 million) of the world's population was undernourished in 2018, and SSA countries still share a substantial amount [ 5 ]. Even though globally the number of people affected by hunger has been decreasing since 1990, in recent years (especially since 2015) the number of people living in food insecurity has increased. It will be a huge challenge to achieve the SDGs of zero hunger by 2030 [ 6 ]. FAO et al. [ 7 ] projected that one in four individuals in SSA were undernourished in 2017. Moreover, FAO et al. [ 8 ] found that, between 2014 and 2018, the prevalence of undernourishment worsened. Twenty percent of the continent's population, or 256 million people, are undernourished today, of which 239 million are in SSA. Hidden hunger is also one of the most severe types of malnutrition (micronutrient deficiencies). One in three persons suffers from inadequacies related to hidden hunger, which impacts two billion people worldwide [ 9 ]. Similarly, SSA has a high prevalence of hidden hunger [ 10 , 11 ].

An important consequence of food insecurity is that around 9 million people die yearly worldwide due to hunger and hunger-related diseases. This is more than from Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS), malaria, and tuberculosis combined [ 6 ]. Even though the hunger crisis affects many people of all genders and ages, children are particularly affected in Africa. There are too many malnourished children in Africa, and malnutrition is a major factor in the high infant mortality rates and causes physical and mental development delays and disorders in SSA [ 12 ]. According to UN statistics, chronic malnutrition globally accounts for 165 million stunted or underweight children. Around 75% of these kids are from SSA and South Asia. Forty percent of children in SSA are impacted. In SSA, about 3.2 million children under the age of five dies yearly, which is about half of all deaths in this age group worldwide. Malnutrition is responsible for almost one child under the age of five dying every two minutes worldwide. The child mortality rate in the SSA is among the highest in the world, about one in nine children pass away before the age of five [ 12 ].

In addition to the direct impact of food insecurity on health outcomes, it also indirectly contributes to disordered eating patterns, higher or lower blood cholesterol levels, lower serum albumin, lower hemoglobin, vitamin A levels, and poor physical and mental health [ 13 , 14 , 15 ]. Iodine, iron, and zinc deficiency are the most often identified micronutrient deficiencies across all age groups. A deficiency in vitamin A affects an estimated 190 million pre-schoolers and 19 million pregnant women [ 16 ]. Even though it is frequently noted that hidden hunger mostly affects pregnant women, children, and teenagers, it further affects people’s health at all stages of life [ 17 ].

With the above information, researchers and policymakers should focus on the issue of food insecurity and health status. The SDGs that were developed in 2015 intend to end hunger in 2030 as one of its primary targets. However, a growing number of people live with hunger and food insecurity, leading to millions of deaths. Hence, this study questioned what is the impact of food insecurity on people's health outcomes in SSA countries. In addition, despite the evidence implicating food insecurity and poor health status, there is a lack of macro-level empirical studies concerning the impact of food insecurity on people’s health status in SSA countries, which leads to a knowledge (literature) gap. Therefore, this study aims to examine the impact of food insecurity on life expectancy and infant mortality in SSA countries for the period ranging from 2001–2018 using panel mean regression approaches.

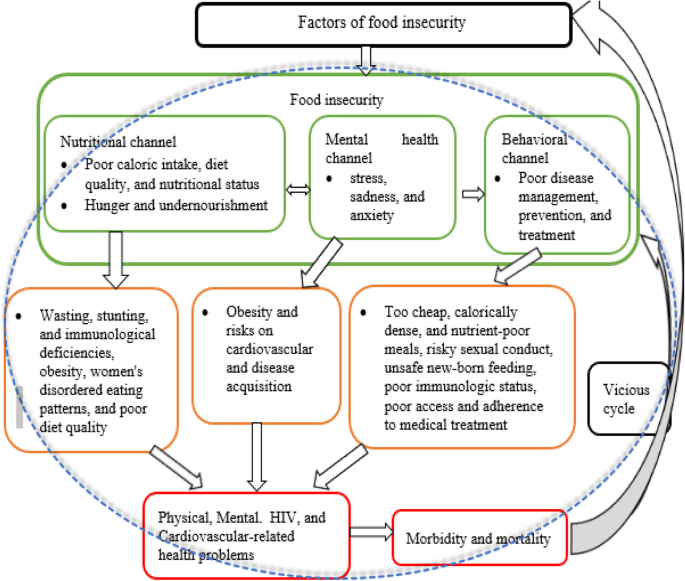

Theoretical and conceptual framework

Structural factors, such as climate, socio-economic, social, and local food availability, affect people’s food security. People’s health condition is impacted by food insecurity through nutritional, mental health, and behavioral channels [ 18 ]. Under the nutritional channel, food insecurity has an impact on total caloric intake, diet quality, and nutritional status [ 19 , 20 , 21 ]. Hunger and undernutrition may develop when food supplies are scarce, and these conditions may potentially lead to wasting, stunting, and immunological deficiencies [ 22 ]. However, food insecurity also negatively influences health due to its effects on obesity, women's disordered eating patterns [ 23 ], and poor diet quality [ 24 ].

Under the mental health channel, Whitaker et al. [ 25 ] noted that food insecurity is related to poor mental health conditions (stress, sadness, and anxiety), which have also been linked to obesity and cardiovascular risk [ 26 ]. The effects of food insecurity on mental health can worsen the health of people who are already sick as well as lead to disease acquisition [ 18 ]. Similarly, the behavioral channel argues that there is a connection between food insecurity and health practices that impact disease management, prevention, and treatment. For example, lack of access to household food might force people to make bad decisions that may raise their risk of sickness, such as relying too heavily on cheap, calorically dense, nutrient-poor meals or participating in risky sexual conduct. In addition, food insecurity and other competing demands for survival are linked to poorer access and adherence to general medical treatment in low-income individuals once they become sick [ 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 ]

Food insecurity increases the likelihood of exposure to HIV and worsens the health of HIV-positive individuals [ 18 ]. Weiser et al. [ 31 ] found that food insecurity increases the likelihood of unsafe sexual activities, aggravating the spread of HIV. It can also raise the possibility of transmission through unsafe newborn feeding practices and worsening maternal health [ 32 ]. In addition, food insecurity has been linked to decreased antiretroviral adherence, declines in physical health status, worse immunologic status [ 33 ], decreased viral suppression [ 34 , 35 ], increased incidence of serious illness [ 36 ], and increased mortality [ 37 ] among people living with HIV.

With the above theoretical relationship between target variables and since this study focuses on the impact of food insecurity on health outcomes, and not on the causes, it adopted the conceptual framework of Weiser et al. [ 18 ] and constructed Fig. 1 .

A conceptual framework of food insecurity and health. Source: Modified and constructed by the author using Weiser et al. [ 18 ] conceptual framework. Permission was granted by Taylor & Francis to use their original Figs. (2.2, 2.3, and 2.4); to develop the above figure. Permission number: 1072954

Several findings associate food insecurity with poorer health, worse disease management, and a higher risk of premature mortality even though they used microdata. For instance, Stuff et al. [ 38 ] found that food insecurity is related to poor self-reported health status, obesity [ 39 ], abnormal blood lipids [ 40 ], a rise in diabetes [ 24 , 40 ], increased gestational diabetes[ 41 ], increased perceived stress, depression and anxiety among women [ 25 , 42 ], Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) acquisition risk [ 43 , 44 , 45 ], childhood stunting [ 46 ], poor health [ 47 ], mental health and behavioral problem [ 25 , 48 , 49 ].

The above highlight micro-level empirical studies, and since the scope of this study is macro-level, Table 1 provides only the existing macro-level empirical findings related to the current study.

Empirical findings in Table 1 are a few, implying a limited number of macro-level level empirical findings. Even the existing macro-level studies have several limitations. For instance, most studies either employed conventional estimation techniques or overlooked basic econometric tests; thus, their results and policy implications may mislead policy implementers. Except for Hameed et al. [ 53 ], most studies’ data are either outdated or unbalanced; hence, their results and policy implications may not be valuable in the dynamic world and may not be accurate like balanced data. Besides, some studies used limited (one) sampled countries; however, few sampled countries and observations do not get the asymptotic properties of an estimator [ 56 ]. Therefore, this study tries to fill the existing gaps by employing robust estimation techniques with initial diagnostic and post-estimation tests, basic panel econometric tests and robustness checks, updated data, a large number of samples.

Study setting and participants

According to Smith and Meade [ 57 ], the highest rates of both food insecurity and severe food insecurity were found in Sub-Saharan Africa in 2017 (55 and 28%, respectively), followed by Latin America and the Caribbean (32 and 12%, respectively) and South Asia (30 and 13%). Similarly, SSA countries have worst health outcomes compared to other regions. For instance, in 2020, the region had the lowest life expectancy [ 58 ] and highest infant mortality [ 59 ]. Having the above information, this study's target population are SSA countries chosen purposively. However, even though SSA comprises 49 of Africa's 55 countries that are entirely or partially south of the Sahara Desert. This study is conducted for a sample of 31 SSA countries (Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Cabo Verde, Chad, Congo Rep., Côte d'Ivoire, Ethiopia, Gabon, The Gambia, Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Sudan, Tanzania, and Togo). The sampled countries are selected based on data accessibility for each variable included in the empirical models from 2001 to 2018. Since SSA countries suffer from food insecurity and related health problems, this study believes the sampled countries are appropriate and represent the region. Moreover, since this study included a large sample size, it improves the estimator’s precision.

Data type, sources, and scope

This study uses secondary data collected in December 2020 online from the databases of the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and the World Bank (WB) (see Table 2 ). In addition, the study uses yearly balanced data from 2001 to 2018, which is appropriate because it captures the Millennium Development Goals, SDGs, and other economic conditions, such as the rise of SSA countries’ economies and the global financial crisis of the 2000s. Therefore, this study considers various global development programs and events. Generally, the scope of this study (sampled countries and time) is sufficient to represent SSA countries. In other words, the study has n*T = 558 observations, which fulfills the large sample size criteria recommended by Kennedy [ 56 ].

The empirical model

Model specification is vital to conduct basic panel data econometric tests and estimate the relationship of target variables. Besides social factors, the study includes economic factors determining people's health status. Moreover, it uses two proxies indicators to measure both food insecurity and health status; hence, it specifies the general model as follows:

The study uses four models to analyze the impact of food insecurity on health outcomes.

where LNLEXP and LNINFMOR (dependent variables) refer to the natural logarithm of life expectancy at birth and infant mortality used as proxy variables for health outcomes. Similarly, PRUND and AVRDES are the prevalence of undernourishment and average dietary energy supply adequacy – proxy and predictor variables for food insecurity.

Moreover, to regulate countries’ socio-economic conditions and to account for time-varying bias that can contribute to changes in the dependent variable, the study included control variables, such as GDPPC, GOVEXP, MNSCHOOL, and URBAN. GDPPC is GDP per capita, GOVEXP refers to domestic general government health expenditure, MNSCHOOL is mean years of schooling and URBAN refers to urbanization. Further, n it , v it , ε it , and μ it are the stochastic error terms at period t. The parameters \({\alpha }_{0}, { \beta }_{0}, { \theta }_{0},{ \delta }_{0}\) refer to intercept terms and \({\alpha }_{1}-{\alpha }_{5}, {\beta }_{1}-{\beta }_{5}, { \theta }_{1}-{\theta }_{5}, and {\delta }_{1}-{\delta }_{5}\) are the long-run estimation coefficients. Since health outcomes and food insecurity have two indicators used as proxy variables, this study estimates different alternative models and robustness checks of the main results. Furthermore, the above models did not address heterogeneity problems; hence, this study considers unobserved heterogeneity by introducing cross-section and time heterogeneity in the models. This is accomplished by assuming a two-way error component for the disturbances with:

From Eq. 2 , the unobservable individual (cross-section) and unobservable time heterogeneities are described by \({\delta }_{i} and {\tau }_{t}\) (within components), respectively. Nonetheless, the remaining random error term is \({\gamma }_{it}\) (panel or between components). Therefore, the error terms in model 1A-1D will be substituted by the right-hand side elements of Eq. 2 .

Depending on the presumptions of whether the error elements are fixed or random, the FE and RE models are the two kinds of models that will be evaluated. Equation ( 2 ) yields a two-way FE error component model, or just a FE model if the assumptions are that \({\delta }_{i} and {\tau }_{t}\) are fixed parameters to be estimated and that the random error component, \({\gamma }_{it}\) , is uniformly and independently distributed with zero mean and constant variance (homoscedasticity).

Equation ( 2 ), on the other hand, provides a two-way RE error component model or a RE model if we suppose \({\delta }_{i} and {\tau }_{t}\) are random, just like the random error term, or \({\delta }_{i},{\tau }_{t}, and {\gamma }_{it}\) are all uniformly and independently distributed with zero mean and constant variance, or they are all independent of each other and independent variables [ 60 ].

Rather than considering both error components, \({\delta }_{i}, and {\tau }_{t}\) , we can examine only one of them at a time (fixed or random), yielding a one-way error component model, FE or RE. The stochastic error term \({\varpi }_{it}\) in Eq. 2 will then be:

Statistical analysis

This study conducted descriptive statistics, correlation analysis, and initial diagnosis tests (cross-sectional and time-specific fixed effect, outliers and influential observations, multicollinearity, normality, heteroscedasticity, and serial correlation test). Moreover, it provides basic panel econometric tests and panel data estimation techniques. For consistency, statistical software (STATA) version 15 was used for all analyses.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

Descriptive statistics is essential to know the behavior of the variables in the model. Therefore, it captures information, such as the mean, standard deviation, minimum, maximum, skewness, and kurtosis. Similarly, the study conducted Pearson correlation analysis to assess the degree of relationship between the variables.

Initial diagnosis

Cross-sectional and time-specific fixed effect.

One can anticipate differences arising over time or within the cross-sectional units, given that the panel data set comprises repeated observations over the same units gathered over many periods. Therefore, before estimation, this study considered unexplained heterogeneity in the models. One fundamental limitation of cross-section, panel, and time series data regression is that they do not account for country and time heterogeneity [ 60 ]. These unobserved differences across nations and over time are crucial in how the error term is represented and the model is evaluated. These unobserved heterogeneities, however, may be represented by including both country and time dummies in the regression. However, if the parameters exceed the number of observations, the estimate will fail [ 60 ]. However, in this study, the models can be estimated. If we include both country and time dummies, we may assume that the slope coefficients are constant, but the intercept varies across countries and time, yielding the two-way error components model. As a result, this study examines the null hypothesis that intercepts differ across nations and time in general.

Detecting outliers and influential observations

In regression analysis, outliers and influential observations may provide biased findings. Therefore, the Cooks D outlier and influential observation test was used in the study to handle outliers and influencing observations. To evaluate whether these outliers have a stronger impact on the model to be estimated, each observation in this test was reviewed and compared with Cook’s D statistic [ 61 ]. Cook distance evaluates the extent to which observation impacts the entire model or the projected values. Hence, this study tested the existence of outliers.

Normality, heteroscedasticity, multicollinearity, and serial correlation test

Before the final regression result, the data used for the variables were tested for normality, heteroscedasticity, multicollinearity, and serial correlation to examine the characteristics of the sample.

Regression models should be checked for nonnormal error terms because a lack of Gaussianity (normal distribution) can occasionally compromise the accuracy of estimation and testing techniques. Additionally, the validity of inference techniques, specification tests, and forecasting critically depends on the normalcy assumption [ 62 ]. Similarly, multicollinearity in error terms leads to a dataset being highly sensitive to a minor change, instability in the regression model, and skewed and unreliable results. Therefore, this study conducted the normality using Alejo et al. [ 62 ] proposed command and multicollinearity (using VIF) tests.

Most conventional panel data estimation methods rely on homoscedastic individual error variance and constant serial correlation. Since the error component is typically connected to the variance that is not constant during the observation and is serially linked across periods, these theoretical presumptions have lately reduced the applicability of various panel data models. Serial correlation and heteroskedasticity are two estimate issues frequently connected to cross-sectional and time series data, respectively. Similarly, panel data is not free from these issues because it includes cross-sections and time series, making the estimated parameters ineffective, and rendering conclusions drawn from the estimation incorrect [ 63 ]. Therefore, this study used the Wooldridge [ 63 ] test for serial correlation in linear panel models as well as the modified Wald test for heteroskedasticity.

Basic panel econometric tests

The basic panel data econometric tests are prerequisites for estimating the panel data. The three main basic panel data tests are cross-sectional dependence, unit root, and cointegration.

Cross-sectional dependence (CD)

A growing body of the panel data literature concludes that panel data models are likely to exhibit substantial CD in the errors resulting from frequent shocks, unobserved components, spatial dependence, and idiosyncratic pairwise dependence. Even though the impact of CD in estimation depends on several factors, relative to the static model, the effect of CD in dynamic panel estimators is more severe [ 64 ]. Moreover, Pesaran [ 65 ] notes that recessions and economic or financial crises potentially affect all countries, even though they might start from just one or two countries. These occurrences inevitably introduce cross-sectional interdependencies across the cross-sectional unit, their regressors, and the error terms. Hence, overlooking the CD in panel data leads to biased estimates and spurious results [ 64 , 66 ]. Further, the CD test determines the type of panel unit root and cointegration tests we should apply. Therefore, examining the CD is vital in panel data econometrics.

In the literature, there are several tests for CD, such as the Breusch and Pagan [ 67 ] Lagrange multiplier (LM) test, Pesaran [ 68 ] scaled LM test, Pesaran [ 68 ] CD test, and Baltagi et al. [ 69 ] bias-corrected scaled LM test (for more detail, see Tugcu and Tiwari [ 70 ]). Besides, Friedman [ 71 ] and Frees [ 72 , 73 ] also have other types of CD tests (for more detail, see De Hoyos and Sarafidis [ 64 ]). This study employs Frees [ 72 ] and Pesaran [ 68 ] among the existing CD tests. This is because, unlike the Breusch and Pagan [ 67 ] test, these tests do not require infinite T and fixed N, and are rather applicable for both a large N and T. Additionally, Free’s CD test can overcome the irregular signs associated with correlation. However, it also employs Friedman [ 71 ] CD for mixed results of the above tests.

Unit root test

The panel unit root and cointegration tests are common steps following the CD test. Generally, there are two types of panel unit root tests: (1) the first-generation panel unit root tests, such as Im et al. [ 74 ], Maddala and Wu [ 75 ], Choi [ 76 ], Levin et al. [ 77 ], Breitung [ 78 ] and Hadri [ 79 ], and (2) the second-generation panel unit root tests, such as [ 66 , 80 , 81 , 82 , 83 , 84 , 85 , 86 , 87 , 88 , 89 ].

The first-generation panel unit root tests have been criticized because they assume cross-sectional independence [ 90 , 91 , 92 , 93 ]. This hypothesis is somewhat restrictive and unrealistic, as macroeconomic time series exhibit significant cross-sectional correlation among countries in a panel [ 92 ], and co-movements of economies are often observed in the majority of macroeconomic applications of unit root tests [ 91 ]. The cross-sectional correlation of errors in panel data applications in economics is likely to be the rule rather than the exception [ 93 ]. Moreover, applying first-generation unit root tests under CD models can generate substantial size distortions [ 90 ], resulting in the null hypothesis of nonstationary being quickly rejected [ 66 , 94 ]. As a result, second-generation panel unit root tests have been proposed to take CD into account. Therefore, among the existing second-generation tests, this study employs Pesaran’s [ 66 ] cross-sectionally augmented panel unit root test (CIPS) for models 1A–1C . The rationale for this is that, unlike other unit root tests that allow CD, such as Bai and Ng [ 80 ], Moon and Perron [ 87 ], and Phillips and Sul [ 84 ], Pesaran’s [ 66 ] test is simple and clear. Besides, Pesaran [ 66 ] is robust when time-series’ heteroscedasticity is observed in the unobserved common factor [ 95 ]. Even though theoretically, Moon and Perron [ 87 ], Choi [ 96 ] and Pesaran [ 66 ] require large N and T, Pesaran [ 66 ] is uniquely robust in small sample sizes [ 97 ]. Therefore, this study employs the CIPS test to take into account CD, and heteroskedasticity in the unobserved common factor and both large and small sample countries. However, since there is no CD in model 1D , this study employs the first-generation unit root tests called Levin, Lin, and Chu (LLC), Im, Pesaran, Shin (IPS) and Fisher augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) for model 1D .

Cointegration test

The most common panel cointegration tests when there is CD are Westerlund [ 98 ], Westerlund and Edgerton [ 99 ], Westerlund and Edgerton [ 100 ], Groen and Kleibergen [ 101 ], Westerlund’s [ 102 ] Durbin-Hausman test, Gengenbach et al. [ 103 ] and Banerjee and Carrion-i-Silvestre [ 104 ]. However, except for a few, most tests are not coded in Statistical Software (STATA) and are affected by insufficient observations. The current study primarily uses Westerlund [ 98 ] and Banerjee and Carrion-i-Silvestre [ 104 ] for models 1A–1C . However, to decide uncertain results, it also uses McCoskey and Kao [ 105 ] cointegration tests for model 1C . The rationale for using Westerlund’s [ 98 ] cointegration test is that most panel cointegration has failed to reject the null hypothesis of no cointegration due to the failure of common-factor restriction [ 106 ]. However, Westerlund [ 98 ] does not require any common factor restriction [ 107 ] and allows for a large degree of heterogeneity (e.g., individual-specific short-run dynamics, intercepts, linear trends, and slope parameters) [ 92 , 107 , 108 ]. Besides, its command is coded and readily available in STATA. However, it suffers from insufficient observations, especially when the number of independent variables increases. The present study employs the Banerjee and Carrion-i-Silvestre [ 104 ] and McCoskey and Kao [ 105 ] cointegration tests to overcome this limitation. The two Engle-Granger-based cointegration tests applicable when there is no CD and are widely used and available in STATA are Pedroni [ 109 , 110 ] and Kao [ 111 ]. However, the Pedroni test has two benefits over Kao: it assumes cross-sectional dependency and considers heterogeneity by employing specific parameters [ 112 ]. Hence, this study uses the Pedroni cointegration test for model 1D .

Panel data estimation techniques

The panel data analysis can be conducted using different estimation techniques and is mainly determined by the results of basic panel econometric tests. Thus, this study mainly employs the Driscoll-Kraay [ 113 ] standard error (DKSE) (for models 1A and 1B ), FE (for model 1C ), and two-step GMM (for model 1D ) estimation techniques to examine the impact of food insecurity on health outcomes. It also employs the Granger causality test. However, for robustness checks, it uses fully modified ordinary least squares (FMOLS), panel-corrected standard error (PCSE), and feasible generalized least squares (FGLS) methods (for models 1A and 1B ). Moreover, it uses a random effect (RE) for model 1C and panel dynamic fixed effect (DFE) techniques for model 1D .

Even though several panel estimation techniques allow CD, most of them – such as cross-section augmented autoregressive distributed lag (CS-ARDL), cross-section augmented distributed lag (CS-DL), common correlated effects pooled (CCEP), and common correlated effects mean group (CCEMG) estimators – require a large number of observations over groups and periods. Similarly, the continuously updated fully modified (CUP-FM) and continuously updated bias-corrected (CUP-BC) estimators are not coded in STATA. Others, like the PCSE, FGLS, and seemingly unrelated regression (SUR), are feasible for T (the number of time series) > N (the number of cross-sectional units) [ 114 , 115 ]. However, a DKSE estimate is feasible for N > T [ 114 ]. Therefore, depending on the CD, cointegration test, availability in STATA, and comparing N against T, this study mainly employs the DKSE regression for models 1A and 1B , FE model for model 1C , and GMM for model 1C .

Finally, to check the robustness of the main result, this study employs FMOLS, FGLS, and PCSE estimation techniques for models 1A and 1B . Furthermore, even though the Hausman test confirms that the FE is more efficient, the study employs the RE for model 1C . This is because Firebaugh et al. [ 116 ] note that the RE and FE models perform best in panel data. Besides, unlike FE, RE assumes that individual differences are random. In addition, this study uses panel DFE for model 1D (selected based on the Hausman test). Finally, the robustness check is also conducted using an alternative model (i.e., when a dependent variable is without a natural log and Granger causality test).

Table 3 shows the overall mean of LNLEXP of the region is 4.063 years which indicates that the region can achieve only 57.43 (using ln(x) = 4.063 = loge (x) = e 4.063 , where e = 2.718) years of life expectancy. This is very low compared to other regions. Besides, the ranges in the value of LNLEXP are between 3.698 and 4.345 or (40–76 years), implying high variation. Similarly, the mean value of LNINFMOR is 3.969; implying SSA countries recorded 52 infants death per 1000. Moreover, the range of LNINFMOR is between 2.525 and 4.919 or (12 – 135 infant death per 1000), implying high variation within the region. The mean value of people’s prevalence for undernourishment is 21.26; indicating 21% of the population is undernourished. However, the mean value of AVRDES is 107.826, which is greater than 100, implying that the calorie supply is adequate for all consumers if the food is distributed according to the requirements of individuals. When we observe the skewness and kurtosis of the variables of the models, except for LNLEXP and LNINFMOR, all variables are positively skewed. In addition, all variables have positive kurtosis with values between 2.202 and 6.092.

Table 3 also shows the degree of relationship between variables, such that most values are below the threshold or rule of thumb (0.7) for a greater association [ 117 ]. However, the association between LNINFMOR and LNLEXP, as well as between PRUNP and AVRDES, is over the threshold and seems to have a multicollinearity issue. Nevertheless, these variables did not exist together in the models, indicating the absence of a multicollinearity problem.

Table 4 shows whether the cross-sectional specific and time-specific FE in extended models ( model 1A-1D plus Eq. 2 ) are valid. The result reveals that the null hypothesis of the captured unobserved heterogeneity is homogenous across the countries, and time is rejected at 1%, implying the extended models are correctly specified. Besides, to check the robustness of the two-way error component model relative to the pooled OLS estimator, this study conducted an additional poolability test. The result shows the null hypothesis that intercepts homogeneity (pooling) is rejected at a 1% level; thus, the FE model is most applicable, but the pooled OLS is biased.

Cooks D is an indicator of high leverage and residuals. The impact is high when D exceeds 4/N, (N = number of observations). A D > 1 implies a significant outlier problem. The Cooks D result of this study confirms the absence of outliers' problem (see supplementary file 1 ).

Normality, heteroscedasticity, serial correlation, and multicollinearity tests

The results in Table 5 indicate that the probability value of the joint test for normality on e and u are above 0.01, implying that the residuals are normally distributed. The heteroscedasticity results show that the probability value of the chi-square statistic is less than 0.01 in all models. Therefore, the null hypothesis of constant variance can be rejected at a 1% level of significance. In other words, the modified Wald test result for Groupwise heteroskedasticity presented in Table 5 , rejects the null hypothesis of Groupwise homoskedasticity observed by the probability value of 0.0000, which implies the presence of heteroscedasticity in the residuals. Similarly, all models suffer from serial correlation since the probability value of 0.0000 rejects the null hypothesis of no first-order serial correlation, indicating the presence of autocorrelation in all panel models. Finally, the multicollinearity test reveals that the models have no multicollinearity problem since the Variance inflation Factors (VIF) values are below 5.

Cross-sectional dependence test

Results in Table 6 strongly reject the null hypothesis of cross-sectional independence for models 1A – 1C . However, for model 1D , the study found mixed results (i.e., Pesaran [ 68 ] fails to reject the null hypothesis of no CD while Frees [ 72 ] strongly rejects it). Thus, to decide, this study employs the Friedman [ 71 ] CD test. The result fails to reject the null hypothesis of cross-sectional independence, implying that two out of three tests fail to reject the null hypothesis of cross-sectional independence in model 1D . Therefore, unlike others, there is no CD in model 1D (see Table 6 ).

Unit root tests

Table 7 shows that all variables are highly (at 1% level) significant either at level (I(0)) or first difference (I(1)), which implies all variables are stationary. In other words, the result fails to reject the null hypothesis of unit root (non-stationary) for all variables at a 1%-significance level, either at levels or the first differences. Thus, we might expect a long-run connection between these variables collectively.

Cointegration tests

The results in Table 8 show that both the Westerlund [ 98 ] and Banerjee and Carrion-i-Silvestre [ 104 ] cointegration tests strongly reject the null hypothesis of no-cointegration in models 1A and 1B . However, model 1C provides a mixed result, i.e. the Banerjee and Carrion-i-Silvestre [ 104 ] test rejects the null hypothesis of no cointegration, yet the reverse is true for the Westerlund [ 98 ] test. Therefore, this study conducted further cointegration tests for model 1C . Even though Westerlund and Edgerton [ 99 ] suffer from insufficient observation, it is based on the McCoskey and Kao [ 105 ] LM test [ 118 ]. Thus, we can use a residual-based cointegration test in the heterogeneous panel framework proposed by McCoskey and Kao [ 105 ]. However, an efficient estimation technique of cointegrated variables is required, and hence the FMOLS and DOLS estimators are recommended. The residuals derived from the FMOLS and DOLS will be tested for stationarity with the null hypothesis of no cointegration amongst the regressors. Since the McCoskey and Kao [ 105 ] test involves averaging the individual LM statistics across the cross-sections, for testing the residuals FMOLS and DOLS stationarity, McCoskey, and Kao [ 105 ] test is in the spirit of IPS (Im et al. [ 74 ]) [ 119 ].

Though FMOLS and DOLS are recommended for the residuals cointegration test, DOLS is better than FMOLS (for more detail, see Kao and Chiang [ 120 ]); therefore, this study uses a residual test derived from DOLS. The result fails to reject the null hypothesis of no cointegration. Two (Banerjee and Carrion-i-Silvestre [ 104 ] and McCoskey and Kao [ 105 ]) out of three tests fail to reject the null hypothesis of no cointegration; hence, we can conclude that there is no long-run relationship among the variables in model 1C .

Unlike other models, since there is CD in model 1D , this study employs the Pedroni [ 109 ] and Kao [ 111 ] cointegration tests for model 1D . The result strongly rejects the null hypothesis of no cointegration, which is similar to models 1A and 1B , that a long-run relationship exists among the variables in model 1D (see Table 5 ).

Panel data estimation results

Table 9 provides long-run regression results of all models employing appropriate estimation techniques such as DKSE, FE, and two-step GMM, along with the Granger causality test. However, the DKSE regression can be estimated in three ways: FE with DKSE, RE with DKSE, and pooled Ordinary Least Squares/Weighted Least Squares (pooled OLS/WLS) regression with DKSE. Hence, we must choose the most efficient model using Hausman and Breusch-Pagan LM for RE tests (see supplementary file 2 ). As a result, this study employed FE with DKSE for models 1A and 1B . Further, due to Hausman's result, absence of cointegration and to deal with heterogeneity and spatial dependence in the dynamic panel, this study employs FE for the model1C (see the supplementary file 2). However, due to the absence of CD, the presence of cointegration, and N > T, this study uses GMM for model 1D . Moreover, according to Roodman [ 121 ], the GMM approach can solve heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation problems. Furthermore, even though two-step GMM produces only short-run results, it is possible to generate long-run coefficients from short-run results [ 122 , 123 ].

The DKSE result of model 1A shows that a 1% increment in people's prevalence for undernourishment reduces their life expectancy by 0.00348 PPs (1 year or 366 days). However, in model 1C, a 1% rise in the prevalence of undernourishment increases infant mortality by 0.0119 PPs (1 year or 369 days). The DKSE estimations in model 1B reveal that people’s life expectancy rises by 0.00317 PPs with every 1% increase in average dietary energy supply. However, the GMM result for model 1D confirms that a 1% incrementin average dietary energy supply reduces infant mortality by 0.0139 PPs. Moreover, this study conducted a panel Granger causality test to confirm whether or not food insecurity has a potential causality to health outcomes. The result demonstrates that the null hypothesis of change in people’s prevalence for undernourishment and average dietary energy supply does not homogeneously cause health outcomes is rejected at 1% significance, implying a change in food insecurity does Granger-cause health outcomes of SSA countries (see Table 9 ).

In addition to the main results, Table 9 also reports some post-estimation statistics to ascertain the consistency of the estimated results. Hence, in the case of DKSE and FE models, the validity of the models is determined by the values of R 2 and the F statistics. For instance, R 2 quantifies the proportion of the variance in the dependent variable explained by the independent variables, representing the model’s quality. The results in Table 9 demonstrate that the explanatory variables explain more than 62% of the variance on the dependent variable. Cohen [ 125 ] classifies the R 2 value of 2% as a moderate influence in social and behavioral sciences, while 13 and 26% are considered medium and large effects, respectively. Therefore, the explanatory variables substantially impact this study's models. Similarly, the F statistics explain all independent variables jointly explain the dependent one. For the two-step system GMM, the result fails to reject the null hypothesis of no first (AR(1)) and second-order (AR(2)) serial correlation, indicating that there is no first and second-order serial correlation. In addition, the Hansen [ 126 ] and Sargan [ 127 ] tests fail to reject the null hypothesis of the overall validity of the instruments used, which implies too many instruments do not weaken the model.

Robustness checks

The author believes the above findings may not be enough for policy recommendations unless robustness checks are undertaken. Hence, the study estimated all models without the natural logarithm of the dependent variables (see Table 10 ). The model 1A result reveals, similar to the above results, individuals’ prevalence for undernourishment significantly reduces their life expectancy in SSA countries. That means a 1% increase in the people's prevalence of undernourishment reduces their life expectancy by 0.1924 PPs. Moreover, in model 1B , life expectancy rises by 0.1763 PPs with every 1% increase in average dietary energy supply. In model 1C , the rise in infants’ prevalence for undernourishment has a positive and significant effect on their mortality rate in SSA countries. The FE result implies that a 1% rise in infants’ prevalence for undernourishment increases their mortality rate by 0.9785 PPs. The GMM result in model 1D indicates that improvement in average dietary energy supply significantly reduces infant mortality. Further, the Granger causality result confirms that the null hypothesis of change in the prevalence of undernourishment and average dietary energy supply does not homogeneously cause health outcomes and is rejected at a 1% level of significance. This implies a change in food insecurity does Granger-cause health outcomes in SSA countries (see Table 10 ).

The study also conducted further robustness checks using the same dependent variables (as Table 9 ) but different estimation techniques. The results confirm that people’s prevalence of undernourishment has a negative and significant effect on their life expectancy, but improvement in average dietary energy supply significantly increases life expectancy in SSA countries. However, the incidence of undernourishment in infants contributes to their mortality; however, progress in average dietary energy supply for infants significantly reduces their mortality (see Table 11 ).

The main objective of this study is to examine the impact of food insecurity on the health outcomes of SSA countries. Accordingly, the DKSE result of model 1A confirms that the rise in people’s prevalence for undernourishment significantly reduces their life expectancy in SSA countries. However, the FE result shows that an increment in the prevalence of undernourishment has a positive and significant impact on infant mortality in model 1C . This indicates that the percentage of the population whose food intake is insufficient to meet dietary energy requirements is high, which leads to reduce life expectancy but increases infant mortality in SSA countries. The reason for this result is linked to the insufficient food supply in SSA due to low production and yields, primitive tools, lack of supporting smallholder farms and investment in infrastructure, and government policies. Besides, even though the food is available, it is not distributed fairly according to the requirements of individuals. Moreover, inadequate access to food, poor nutrition, and chronic illnesses are caused by a lack of well-balanced diets. In addition, many of these countries are impacted by poverty, making it difficult for citizens to afford nutritious food. All these issues combine to create an environment where individuals are more likely to suffer malnutrition-related illnesses, resulting in a lower life expectancy rate. The DKSE estimation result in model 1B reveals that improvement in average dietary energy supply positively impacts people's life expectancy in SSA countries. However, the improvement in average dietary energy supply reduces infant mortality.

Based on the above results, we can conclude that food insecurity harms SSA nations' health outcomes. This is because the prevalence of undernourishment leads to increased infant mortality by reducing the vulnerability, severity, and duration of infectious diseases such as diarrhea, pneumonia, malaria, and measles. Similarly, the prevalence of undernourishment can reduce life expectancy by increasing the vulnerability, severity, and duration of infectious diseases. However, food security improves health outcomes – the rise in average dietary energy supply reduces infant mortality and increases the life expectancy of individuals.

Several facts and theories support the above findings. For instance, similar to the theoretical and conceptual framework section, food insecurity in SSA countries can affect health outcomes in nutritional, mental health, and behavioral channels. According to FAO et al. [ 128 ], the prevalence of undernourishment increased in Africa from 17.6% of the population in 2014 to 19.1% in 2019. This figure is more than twice the global average and the highest of all regions of the world. Similarly, SSA is the world region most at risk of food insecurity [ 129 ]. According to Global Nutrition [ 130 ] report, anemia affects an estimated 39.325% of women of reproductive age. Some 13.825% of infants have a low weight at birth in the SSA region. Excluding middle African countries (due to lack of data), the estimated average prevalence of infants aged 0 to 5 months who are exclusively breastfed is 35.73%, which is lower than the global average of 44.0%. Moreover, SSA Africa still experiences a malnutrition burden among children aged under five years. The average prevalence of overweight is 8.15%, which is higher than the global average of 5.7%. The prevalence of stunting is 30.825%—higher than the worldwide average of 22%. Conversely, the SSA countries’ prevalence of wasting is 5.375%, which is higher than most regions such as Central Asia, Eastern Asia, Western Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, and North America. The SSA region's adult population also faces a malnutrition burden: an average of 9.375% of adult (aged 18 and over) women live with diabetes, compared to 8.25% of men. Meanwhile, 20.675% of women and 7.85% of men live with obesity.

According to Saltzman et al. [ 17 ], micronutrient deficiencies can affect people’s health throughout their life cycle. For instance, at the baby age, it causes (low birth weight, higher mortality rate, and impaired mental development), child (stunting, reduced mental capacity, frequent infections, reduced learning capacity, higher mortality rate), adolescent (stunting, reduced mental capacity, fatigue, and increased vulnerability to infection), pregnant women (increased mortality and perinatal complications), adult (reduced productivity, poor socio-economic status, malnutrition, and increased risk of chronic disease), elderly (increased morbidity (including osteoporosis and mental impairment), and higher mortality rate).

Though this study attempts to fill the existing gaps, it also has limitations. It examined the impact of food insecurity on infant mortality; however, their association is reflected indirectly through other health outcomes. Hence, future studies can extend this study by examining the indirect effect of food insecurity on infant mortality, which helps to look at in-depth relationships between the variables. Moreover, this study employed infant mortality whose age is below one year; hence, future studies can broaden the scope by decomposing infant mortality into (neonatal and postnatal) and under-five mortality.

Millions of people are dying every year due to hunger and hunger-related diseases worldwide, especially in SSA countries. Currently, the link between food insecurity and health status is on researchers' and policymakers' agendas. However, macro-level findings in this area for most concerned countries like SSA have been given only limited attention. Therefore, this study examined the impact of food insecurity on life expectancy and infant mortality rates. The study mainly employs DKSE, FE, two-step GMM, and Granger causality approaches, along with other estimation techniques for robustness checks for the years between 2001 and 2018. The result confirms that food insecurity harms health outcomes, while food security improves the health status of SSA nations'. That means that a rise in undernourishment increases the infant mortality rate and reduces life expectancy. However, an improvement in the average dietary energy supply reduces infant mortality and increases life expectancy. Therefore, SSA countries need to guarantee their food accessibility both in quality and quantity, which improves health status. Both development experts and political leaders agree that Africa has the potential for agricultural outputs, can feed the continent, and improve socio-economic growth. Besides, more than half of the world's unused arable land is found in Africa. Therefore, effective utilization of natural resources is essential to achieve food security. Moreover, since the majority of the food in SSA is produced by smallholder farmers [ 131 ] while they are the most vulnerable to food insecurity and poverty [ 132 , 133 ]; hence, special focus and support should be given to smallholder farmers that enhance food self-sufficiency. Further, improvement in investment in agricultural research; improvement in markets, infrastructures, and institutions; good macroeconomic policies and political stability; and developing sub-regional strategies based on their agroecological zone are crucial to overcoming food insecurity and improving health status. Finally, filling a stomach is not sufficient; hence, a person's diet needs to be comprehensive and secure, balanced (including all necessary nutrients), and available and accessible. Therefore, SSA countries should ensure availability, accessibility, usability, and sustainability to achieve food and nutrition security.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available in supplementary materials.

Abbreviations

Augmented Dickey–Fuller

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

Average Dietary Energy Supply

Common Correlated Effects Mean Group

Common Correlated Effects Pooled

Cross-Sectional Dependence

Cross-Sectionally Augmented Panel Unit Root Test

Cross-Section Augmented Autoregressive Distributed Lag

Cross-Section Augmented Distributed Lag

Continuously Updated Bias-Corrected

Continuously Updated Full Modified

Dynamic Fixed Effect

Driscoll-Kraay Standard Errors

Dynamic Ordinary Least Square

Error Correction Model

Food and Agricultural Organization

Fixed Effect

Feasible Generalised Least Squares

Fully Modified Ordinary Least Square

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita

Generalised Method of Momentum

Domestic General Government Health Expenditure

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

Integration at First Difference

International Fund for Agricultural Development

Infant Mortality Rate

Im, Pesaran, Shin

Lag of Infant Mortality Rate

Lag of Natural Logarithm of Infant Mortality Rate

Life Expectancy at Birth

Levin, Lin, and Chu

Lagrange Multiplier

Natural Logarithm of Infant Mortality Rate

Natural Logarithm of Life Expectancy at Birth

Mean Years of Schooling

Ordinary Least Squares

Panel-Corrected Standard Error

Pooled Mean Group

Prevalence of Undernourishment

Random Effect

Sustainable Development Goals

Sub-Saharan African

Statistical Software

Seemingly Unrelated Regression

Urbanisation

World Food Programme

World Health Organization

Weighted Least Squares

Giller KE. The food security conundrum of sub-Saharan Africa. Glob Food Sec. 2020;2020(26): 100431.

Article Google Scholar

WHO. Reducing risks, promoting healthy life. World Health Report. Switzerland: WHO; 2002. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42510/WHR_2002.pdf?sequence=1 .

Food Research and Action Center. Hunger and health: the impact of poverty, food insecurity, and poor nutrition on health and well-being. Washington, DC: Food Research & Action Center; 2017. https://frac.org/research/resource-library/hunger-health-impact-poverty-food-insecurity-poor-nutrition-health-well .

Google Scholar

FAO, IFAD, WFP. The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2013. The multiple dimensions of food security. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 2013. Available from: http://www.fao.org/3/i3434e/i3434e00.htm .

Roser M, Ritchie H. Hunger, and Undernourishment. Oxford: University of Oxford; 2013. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/hunger-and-undernourishment .

Word Count. How many people die from hunger each year. Denmark: The World Counts; 2020. Available from: https://www.theworldcounts.com/challenges/people-and-poverty/hunger-and-obesity/how-many-people-die-from-hunger-each-year/story .

FAO IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, and WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2018. Building Climate Resilience for Food Security and Nutrition. Technical report. FAO. 11 September 2018. Available from: https://www.fao.org/3/I9553EN/i9553en.pdf or https://www.wfp.org/publications/2018-state-food-security-and-nutrition-world-sofi-report .

FAO, ECA, AUC. Africa regional overview of food security and nutrition 2019 -in brief. 2020.

UNHCR. UNHCR describes the alarming health and nutrition situation in South Sudan camps. News Stories, 24 August 2012. Available from: http://www.unhcr.org/503881659.html .

Laxmaiah A, Arlappa N, Balakrishna N, Mallikarjuna RK, Galreddy C, Kumar S, Ravindranath M, Brahmam GN. Prevalence and determinants of micronutrient deficiencies among rural children of eight states in India. Ann NutrMetab. 2013;62(3):231–41.

CAS Google Scholar

Muthayya S, Rah JH, Sugimoto JD, Roos FF, Kraemer K, Black RE. The global hidden hunger indices and maps: an advocacy tool for action. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(6): e67860.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

SOS. Hunger and Food Scarceness in Africa. Washington, DC: SOS Children’s Villages; 2018. Available from: https://www.sos-usa.org/about-us/where-we-work/africa/hunger-in-africa .

Gulliford MC, Mahabir D, Rocke B. Food insecurity, food choices, and body mass index in adults: nutrition transition in Trinidad and Tobago. Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32:508–16.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Stuff JE, Casey PH, Szeto K, Gossett J, Weber J, Simpson P, et al. Household food insecurity and adult chronic disease in the lower Mississippi delta. J Federation Am Soc Experiment Biol. 2005;19:A986.

Parker ED, Widome R, Nettleton JA, Pereira MA. Food security and metabolic syndrome in U.S. adults and adolescents: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999-2006. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20:364–70.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

WHO. Global Prevalence of Vitamin A Deficiency in Populations at Risk 1995–2005: WHO Global Database on Vitamin A Deficiency. 2009. Available from: www.who.int/vmnis/vitamina/en/ .

Saltzman A, Birol E, Wiesman D, Prasai N, Yohannes Y, Menon P, Thompson J. 2014 global hunger index: The challenge of hidden hunger. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute; 2014.

Weiser SD, Palar K, Hatcher AM, Young SL, Frongillo EA. Food insecurity and health: a conceptual framework. In: Ivers L, editors. Food insecurity and public health (pp. 23-50). 1st ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2015.

Rose D. Economic determinants and dietary consequences of food insecurity in the United States. J Nutr. 1999;129(2):517S-S520.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Dixon LB, Winkleby MA, Radimer KL. Dietary intakes and serum nutrients differ between adults from food-insufficient and food-sufficient families: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. J Nutr. 2001;131(4):1232–46.

Kirkpatrick SI, Tarasuk V. Food insecurity is associated with nutrient inadequacies among Canadian adults and adolescents. J Nutr. 2008;138(3):604–12.

Schaible UE, Kaufmann SH. Malnutrition and infection: complex mechanisms and global impacts. PLoS Med. 2007;4(5): e115.

Laraia B, Epel E, Siega-Riz AM. Food insecurity with the experience of restrained eating is a recipe for increased gestational weight gain. Appetite. 2013;65:178–84.

Seligman HK, Bindman AB, Vittinghoff E, Kanaya AM, Kushel MB. Food insecurity is associated with diabetes mellitus: results from the National Health Examination and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2002. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(7):1018–23.

Whitaker RC, Phillips SM, Orzol SM. Food insecurity and the risks of depression and anxiety in mothers and behavior problems in their preschool-aged children. Pediatrics. 2006;118(3):e859–68.

Black PH, Garbutt LD. Stress, inflammation, and cardiovascular disease. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52(1):1–23.

Cunningham WE, Andersen RM, Katz MH, Stein MD, Turner BJ, Crystal S, Zierler S, Kuromiya K, Morton SC, St. Clair P, Bozzette SA. The impact of competing subsistence needs and barriers on access to medical care for persons with human immunodeficiency virus receiving care in the United States. Med Care. 1999;37(12):1270–81.

Kushel MB, Gupta R, Gee L, Haas JS. Housing instability and food insecurity as barriers to health care among low-income Americans. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(1):71–7.

Weiser SD, Tuller DM, Frongillo EA, Senkungu J, Mukiibi N, Bangsberg DR. Food insecurity as a barrier to sustained antiretroviral therapy adherence in Uganda. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(4): e10340.

Bengle R, Sinnett S, Johnson T, Johnson MA, Brown A, Lee JS. Food insecurity is associated with cost-related medication non-adherence in community-dwelling, low-income older adults in Georgia. J Nutr Elder. 2010;29(2):170–91.

Weiser SD, Leiter K, Bangsberg DR, Butler LM, Percy-de Korte F, Hlanze Z, Phaladze N, Iacopino V, Heisler M. Food insufficiency is associated with high-risk sexual behavior among women in Botswana and Swaziland. PLoS med. 2007;4(10): e260.

Mehta S, Manji KP, Young AM, Brown ER, Chasela C, Taha TE, Read JS, Goldenberg RL, Fawzi WW. Nutritional indicators of adverse pregnancy outcomes and mother-to-child transmission of HIV among HIV-infected women. Am J ClinNutr. 2008;87(6):1639–49.

Weiser SD, Bangsberg DR, Kegeles S, Ragland K, Kushel MB, Frongillo EA. Food insecurity among homeless and marginally housed individuals living with HIV/AIDS in San Francisco. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(5):841–8.

Weiser SD, Frongillo EA, Ragland K, Hogg RS, Riley ED, Bangsberg DR. Food insecurity is associated with incomplete HIV RNA suppression among homeless and marginally housed HIV-infected individuals in San Francisco. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(1):14–20.

Kalichman SC, Cherry C, Amaral C, White D, Kalichman MO, Pope H, Swetsze C, Jones M, Macy R. Health and treatment implications of food insufficiency among people living with HIV/AIDS, Atlanta. Georgia J Urban Health. 2010;87(4):631–41.

Weiser SD, Gupta R, Tsai AC, Frongillo EA, Grede N, Kumbakumba E, Kawuma A, Hunt PW, Martin JN, Bangsberg DR. Changes in food insecurity, nutritional status, and physical health status after antiretroviral therapy initiation in rural Uganda. J Acquir Immune DeficSyndr (1999). 2012;61(2):179.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Weiser SD, Fernandes KA, Brandson EK, Lima VD, Anema A, Bangsberg DR, Montaner JS, Hogg RS. The association between food insecurity and mortality among HIV-infected individuals on HAART. J Acquir Immune DeficSyndr (1999). 2009;52(3):342.

Stuff JE, Casey PH, Szeto KL, Gossett JM, Robbins JM, Simpson PM, et al. Household food insecurity is associated with adult health status. J Nutr. 2004;134(9):2330–5.

Dinour LM, Bergen D, Yeh MC. The food insecurity–obesity paradox: a review of the literature and the role food stamps may play. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107(11):1952–61.

Seligman HK, Davis TC, Schillinger D, Wolf MS. Food insecurity is associated with hypoglycemia and poor diabetes self-management in a low-income sample with diabetes. J Health Care Poor U. 2010;21(4):1227.

Laraia B, Siega-Riz AM, Gundersen C. Household food insecurity is associated with self-reported pregravid weight status, gestational weight gain, and pregnancy complications. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110:692–701.

Laraia BA, Siega-Riz AM, Gundersen C, Dole N. Psychosocial factors and socioeconomic indicators are associated with household food insecurity among pregnant women. J Nutr. 2006;136:177–82.

Miller CL, Bangsberg DR, Tuller DM, Senkungu J, Kawuma A, Frongillo EA, et al. Food insecurity and sexual risk in an HIV endemic community in Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(7):1512–9.

Tsai AC, Bangsberg DR, Frongillo EA, Hunt PW, Muzoora C, Martin JN, et al. Food insecurity, depression and the modifying role of social support among people living with HIV/AIDS in rural Uganda. SocSci Med. 2012;74(12):2012–9.

Vogenthaler NS, Kushel MB, Hadley C, Frongillo EA, Riley ED, Bangsberg DR, et al. Food insecurity and risky sexual behaviors among homeless and marginally housed HIV-infected individuals in San Francisco. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(5):1688–93.

Baig-Ansari N, Rahbar MH, Bhutta ZA, Badruddin SH. Child’s Child’s gender and household food insecurity are associated with stunting among young Pakistani children residing in urban squatter settlements. Food Nutr Bull. 2006;27(2):114–27.

Gundersen C, Kreider B. Bounding the effects of food insecurity on children’s health outcomes. J Health Econ. 2009;28(5):971–83.

Cole SM, Tembo G. The effect of food insecurity on mental health: panel evidence from rural Zambia. SocSci Med. 2011;73(7):1071–9.

Weaver LJ, Owens C, Tessema F, Kebede A, Hadley C. Unpacking the “black box” of global food insecurity and mental health. SocSci Med. 2021;282: 114042.

Uchendu FN. Hunger influenced life expectancy in war-torn Sub-Saharan African countries. J Health PopulNutr. 2018;37(1):1–4.