World History Edu

- Haitian Revolution

The Haitian Revolution: Origin Story, Causes, Outcome and Major Effects

by World History Edu · March 11, 2023

Haitian Revolution: the only slave uprising that resulted in the birth of the world’s first black republic

Having grown tired of over three centuries of the worst form of oppression, social hierarchy and brutal enslavement, black African slaves in the prosperous French colony of Saint-Domingue began a brutal revolt against the white plantation class and slave owners in 1791. The revolt, which lasted until 1804, came to be known as the Haitian Revolution, the first successful slave uprising that culminated in the overthrow of French and European control and then the birth of the world’s first black republic.

It was the first time in all of history that blacks were able to challenge the prevailing stereotypes about their race being inferior and lacking the capacity to rule themselves. The Haitian Revolution, which was anything but a simple affair, sent shockwaves throughout the world.

And even to this day, the successful insurrection, which is known in French as révolution haïtienne, continues to serve as a potent inspiration in the struggle against racism, oppression, and all forms of neo-colonialism across the world.

What exactly triggered the Haitian Revolution? Who were the leaders? And what did the revolution accomplish?

Below, World History Edu explores the root causes, outcome and major effects of the Haitian Revolution.

How did France begin its colonial rule of Haiti?

Famed Italian navigator and explorer Christopher Columbus is credited with being the first-known European for setting eyes on Haiti in December 1492. The explorer called the island La Isla Española (“The Spanish Island”) in honor of the Spanish monarchs that backed his expedition to the New World.

Ultimately, the island came to be called Hispaniola in English. In the decades that followed, not only did the natives of the island suffer and die as a result of diseases brought forth by the European settlers, the natives were enslaved and sent to work in the mines under terrible conditions. Such was the devastation unleashed (directly or indirectly) by the Europeans on Hispaniola that by the early 17th century, there were hardly any natives on the island.

Therefore, the European settlers did what every European power was good at the time: slavery. Several tens of thousands of black slaves were brought to Hispaniola to shore up the depleting human capital. Many of those slaves arrived from the slave coast of West Africa, while the rest were simply transferred from other Caribbean islands.

Saint-Domingue was the western part of the island of Hispaniola. The eastern part, Santo Domingo, was held by Spain. Image: Saint-Domingue

Saint-Domingue becomes France’s wealthiest overseas colony

Control of the western part of Hispaniola gradually began to move into the hands of the French as the gold mines got depleted. In mid-1660s, French colonists founded the Port-de Paix settlement in the northwestern part (Saint-Domingue) of the island. By the end of the 17th century, the French settlers had started turning their side of the island into massive plantations of sugarcane and coffee. Owing to how labor-intensive those plantations were at the time, the French landowners in Saint-Domingue began mass importing thousands and thousands of African slaves.

France would rake in a fortune from those sugarcane plantations on its part of Hispaniola. This resulted in more and more importation of African slaves. Basically, the vast wealth generated by the French colony of Saint-Domingue was built upon the backs of African slaves whom were treated worse than animals. For many decades, the slave population endured insufferable conditions.

The oppressive social hierarchy in Saint-Domingue and the size of the slave population

To put into perspective just how many slaves were at the beck and call of white slave owners in Saint-Domingue; it’s estimated that the slave population shot up from a mere 4500 in the late 1600s to about half a million by the end of the 1700s. At the peak of slavery on the island, slaves outnumbered white plantation class by 12 to 1.

The social structure of Saint-Domingue in the late 18th century had the European white plantation owners at the top, followed by the white shopkeepers, administrators and artisans. Next were the affranchis, i.e. free people of mixed-race. Firmly at the bottom, and with the slimmest of chance to rise, were the enslaved Africans that numbered about 500,000.

It was often the case that those three classes hated each other for obvious reasons. For example the rich whites were hated by the poor whites. And the middle-class whites ( petit blancs ) were often jealous of the aristocratic whites ( grands blancs ). Then, the mulattos (mixed-race) class hated the white-ruling class in general. The free Africans envied the mulattos, while the Creoles (i.e. slaves born on the island) perceived newly arrived slaves from Africa as a bit uncultured. The African-born slaves made up about 60% of the enslaved population in Saint-Domingue.

The social hierarchy of the French colony of Saint-Domingue had White colonists (les blancs) at the top, followed by the free people of color (gens de couleur libres), and then the African-born slaves. In the late 1700s, white colonists were in the region of 40,000, free people of color 28,000, and the enslaved population were around half a million. Image: slaves working on a sugarcane plantation

Why Le Cap had the largest slave population of Saint-Domingue

Just as Saint-Domingue had the largest population of enslaved Africans, it also had the largest population of grands blancs in the Caribbean. Many of them resided in the northern part (Plaine-du-Nord) of the island. This was because that region had some of the most fertile lands in the Caribbean. As a result, many of the sugar plantations were set up in that region. The northern port Le Cap (Le Cap Français) even served as the capital of Saint-Domingue from 1711 to 1770.

Causes of the Haitian Revolution

Saint-Domingue slave revolt broke out in August 1791. Led by Dutty Boukman, the rebels were merciless in their march, killing scores of enslavers. The first few days of the revolt were filled with enormous hatred that turned into extreme violence, including the decapitation of white children

Basically, the causes of the Haitian Revolution came in three folds. First, the mixed-race population although free had grown very frustrated by the lack of equality between them and the white plantation class. The mixed-race class hoped for more radical changes in the social structure. The second and equally important cause was the sheer level of brutality slave owners unleashed upon slaves. Finally, ideas of equality, liberty and fraternity that stemmed from French Revolution sent repels across the world. When those ideas hit the shores of Haiti, the disenfranchised and enslaved classes on the island embraced them and mounted a fierce fight for their independence.

Discontent from the free mulattoes

Although the population of mixed African and European descent were free, there was growing discontent among them because France never recognized them as equal to the European colonists.

What’s even interesting is that some of the mulattoes were wealthy enough to own plantations filled with many slaves. However, the majority of those mulattoes were nowhere close to the level of social and economic status that the whites on the island had. They also had to endure some level of discrimination from the whites, who considered all non-whites inferior.

At social gatherings, the free people of color (i.e. gens de couleur libres ) were required to stand up when in the presence of the white colonists. They also required to wear certain kinds of clothing. Basically, their civil rights – in terms of employment, housing and security – were nowhere near the white colonists.

This explains why this class of people were some of the first to push for radical social changes as they were free but not equal.

In 1791, citizenship rights were granted to some mulattos after an impassionate petition was made to the French National Assembly. However, the white colonists were far from pleased with those new civil protections granted to the mulattos. White colonists refused to comply with those limited reforms and even began threatening the mixed-race population.

It was as a result of this animosity that some free people of color decided to cast their lot with the slaves when the Haiti Revolution began in August 1791. Some of them even became leading figures of the revolution.

The French Revolution and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

On August 26, 1789, French Revolutionaries in the newly formed National Assembly (formed on June 20, 1789) came out with a bold declaration – i.e. the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen – to support the ideals of the revolution. Similar to the ideas propagated by French Enlightenment thinkers, the Declaration fell short when it came to granting equality slaves, women and even French citizens of the colonies.

The ideas of equality, liberty and fraternity that stemmed from French Revolution sent repels across the world. When those ideas hit the shores of Haiti, the disenfranchised and enslaved classes on the island embraced them and mounted a fierce fight for their civil liberties and independence.

RELATED: 9 Major Causes of the French Revolution

The French Revolution sent ripples across the world, heavily influencing enslaved Africans in Saint-Domingue to revolt

For example, the ambiguity of the Declaration (i.e. “all men free and equal”) obviously enraged many white farmers in the colonies. A significant number of them wanted to break free France and declare themselves independent, almost similar to what the American colonies did in the 1770s and early 1780s.

To many enslaved Africans, an independent Saint-Domingue headed by the white planters would only make their already deplorable situation much worse. For many years, Paris and the monarch were the only things that kept the white planters from going all out berserk on the slaves in Saint-Domingue.

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, painted by French illustrator Jean-Jacques-François Le Barbier

Again, almost similar to the political issues (i.e. request for representation in London, England) raised by American colonists in the lead up to the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783), many people of color in Saint-Domingue passionately appealed to Paris to grant them more civil protections. Notable advocates of the cause included Vincent Ogé and Julien Raimond. After all appeals fell on deaf ears, the former, who was a wealthy businessman, embarked on a brief insurgency with about just a few hundreds of followers. The colonial authorities on the island were quick to clamp down on the armed rebellion, and in the process, Ogé was executed in 1791. The colonial governor hoped that Ogé’s execution would send a stern message to would-be insurgents and rebels that such actions was not going to be tolerated.

Vincent Ogé, a Saint-Domingue native and a person of mixed-race, was an extremely wealthy businessman led a failed rebellion against the colonial authorities. Ogé banded with other rich members of his class and demanded social reforms, especially more civil protections for free people of color.

Vincent Ogé (c. 1757-1791) was a wealthy mixed-race member of the colonial elite of Saint-Domingue

Other causes of the Haitian Revolution

With many European powers locked in an endless struggle for big slice of the New World, the Spanish had started growing very jealous of France’s extremely wealthy colony of Saint-Domingue. Spain and other European monarchies, including Britain, desired nothing more than to wrestle the colony away from France.

By so doing, those European countries could deny France all the riches that the Saint-Domingue generated. This would in turn cripple French Revolutionaries’ efforts against the rest of Europe.

Spain and other European powers tried to court political dissenters in Saint-Domingue. They hoped that the instability created on the island would affect the riches that were generated by France from the island, which in turn were used by the French revolutionaries to fight Spain and other powers in Europe.

Life of a slave in Saint-Domingue

Luckily for the mulattoes they did not have to suffer like enslaved Africans on the island. Slaves were basically forced to work from dawn to dusk, working until the point of exhaustion or even to death.

The severest kinds of punishments were visited upon any slave who resisted in the slightest bit, or those who broke any of their master’s command.

Slaves lived in an environment of relentless terror, suffering all manner of physical and mental abuse, including amputations for runaways that tried to flee into the mountainous interior. The unlucky ones were beaten, hung and then left to die: a stern message to would-be offenders.

Basically, the lives of slaves were given little value as French colonists used brutal tools to maintain control of the island.

If the backbreaking jobs on the fields and physical abuse didn’t kill a slave, then a slave’s life was often cut short by tropical diseases (like malaria and yellow fever) and infections, starvation, and malnutrition.

Slave traders and owners found out that since the mortality rate of the slaves was very low, it was better to work the slaves to exhaustion. With slave owners paying very little regard to the lives of their slaves, especially the males, women began engaging in polyandry. This meant that France had to continually ship in new slaves to the island.

Mortality rate of enslaved people in Saint-Domingue exceeded the birth rate. It’s not surprising that polyandry became common on the island as there were more men than women. This was also the reason why more and more slaves were imported into the island, as it was needed to maintain the labor force needed to slave on the sugarcane and coffee plantations. Image: A St. Dominican girl with her nanny

Did you know?

- The commonest destination for runaway slaves in Saint-Domingue was in the mountainous regions of the island. The slaves there (known as Maroons) banded together and did their best by living of whatever the land offered them. In some cases, they mounted a number of guerrilla attacks against white settlements in order to secure vital supplies for their survival.

- Less than five years before the outbreak of the Haitian Revolution, French ships transported about a 21,000 slaves from Africa to Saint-Domingue. This further emphasis the point: slavery was an important part of the sugar production on the island.

- French slave masters took were considered the cruelest in the Caribbean. They adopted relentless terror as a means to control the slave population, which outnumbered them by more than 10 to 1. In the northern part of the island, that ratio was worse. It’s said that slave-owning class usually feared of a slave rebellion.

- With France becoming infamous for brutalizing slaves in its territories, King Louis XIV of France passed the Code Noir in 1685 in order to mitigate the level of violence directed towards the enslaved Africans in Saint-Domingue.

- The name Haiti comes from the Taino language. The name means “high mountains”. It was often the case that runaway slaves fled to the interior of the mountainous regions.

The Vodou ceremony at Bois Caïman and its importance

In early August, 1791, enslaved blacks had their first major meeting at Bois Caïman to plan a massive slave insurrection, which would later morph into the Haitian Revolution.

Vodou ritual ceremonies were seen as an important event where enslaved people could meet and reconnect with their African roots. Those rituals helped to bring them together. The whites and slave-owning class permitted the Vodou rituals because they did not see them as a threat. However, beneath those gatherings and events, laid pent up energy and desire to one day break the shackles that held enslaved Africans on the island.

At one particular Vodou ritual on the night of August 14, 1791, slaves from many nearby plantations attended a gathering. The ceremony, which was held at Bois Caïman, was led by an enslaved Jamaican Vodou priest (Houngan) called Dutty Boukman. Also present the Bois Caïman session was the Vodou high priestess (a mambo) Cécile Fatiman.

The Vodou religious ceremony at Bois Caïman is often seen as the first Haitian congress and the beginning of the Haitian Revolution. It was there that the slaves decided to no longer be in shackles. Renowned for his speaking abilities, Boukman Dutty constantly encouraged the gatherings to first free their mind and begin to think of themselves as free people. The participants of the ceremony made a bold decision to take their destiny into their hands: They planned to revolt.

Also at the meeting, which was said to have been attended by about 200 enslaved Africans, Boukman made a big prophecy that stated the likes of George Biassou and Jean François would lead enslaved Haitians to victory against the slave owners.

They strategized and agreed to begin the revolt in two weeks’ time. Before the meeting ended, the priests carried out animal sacrifices (probably pig), drank the blood of the animal, and then swore every member of the meeting to secrecy. The biggest take from the meeting was the plan to have their uprisings in multiple locations at a particular time. Most importantly, Boukman encouraged the members to be swift and decisive once the uprising began. The would-be slave rebels were also asked to not hold back and seek the highest form of revenge against their masters.

The Haitian Vodou religion served a huge purpose before and during the Haitian Revolution. Generally permitted by the slave owners, Vodou religious ceremonies helped create a common culture among enslaved Africans on the island. Bear in mind, those enslaved people, although predominantly from the slave coast of West Africa, came from different tribes. The Vodou religious gatherings allowed the slaves to band together. Steadily, the discussions held there morphed from the simple religious talk to plotting the downfall of their masters. They took a communion and ordered the members to keep what they saw and heard to themselves.

Did you know…?

- In some accounts, it is said that during the meeting at Bois Caïman, high priestess Fatiman’s body was possessed by a Vodou spirit called Erzulie Dantor.

- It is said that many of the enslaved Africans in Saint-Domingue were from the West African kingdom of Dahomey (located in present-day Benin). Others came from Nigeria, Angola and Congo.

French Enlightenment writer Guillaume Raynal (1713-1796)

August 22, 1791: the Haitian Revolution begins

Just a few weeks the Vodou meeting at Bois Caïman, over 1,000 enslaved Africans unleash terror upon the ruling white en slavers in the French colony of Saint-Domingue, marking the beginning of the Haitian Revolution.

Records show that the brutal uprising began on August 22, 1791 in a relatively coordinated manner as slaves from neighboring plantations unleashed mayhem. They showed no mercy as they were out to get full revenge for the centuries of oppression and enslavement. The rebellion completely caught the white slave-owning population by surprise, with many of them being killed while they slept.

Bookman, the leading figure of the rebel slaves at the time, encouraged the slaves to be brutal and visit upon the white the same level of violence the whites had used against them.

Vodou high priest Dutty Boukman initially served as the leader of the slave revolt that broke out in 1791

Steadily, more and more slaves joined the revolt, and sugarcane fields and refineries were set ablaze. Homes of slave owners were also destroyed. Beginning with 1000 slaves, the revolt soon swirled to 20,000. The goal was simple: Destroy the system that suppressed them for centuries. In just a few days, the slaves had successful laid waste to large parts of the Northern Plain (Plaine-du-Nord) of the island. Almost 200 sugar plantations and 1000 coffee farms were destroyed.

Some mixed-race people were not sparred, as the rebels saw them collaborators of the white Europeans. As a result, both whites and mixed-race people fled to the capital city, Port-au-Prince.

George Biassou (1741-1801) is generally revered as one of the early leaders of the 1791 slave rebellion in Saint-Domingue.

French colonists kill Boukman

Many slaves firmly believed that Boukman’s hands were being steered directly by the gods. This belief almost made the Vodou priest appear invincible. As a result, more and more slaves joined the uprising. After suffering heavy losses in the first few days of the slave uprising, the French managed to regroup a bit and went on the search of Boukman. Their goal was to take out Boukman in order to quickly douse the rebellion. Bookman was captured and beheaded November 7, 1791. His head was put in a spike to show the rebels that priest was mortal and did not have any supernatural power.

Regardless of Boukman’s death, the number of rebels continued to swirl. In the months that followed, the number reached around 110,000 in the north. In the south, the slaves were led by a free black coffee plantation owner named Romaine-la-Prophétesse. Romaine was even able to secure a peace treaty with whites and gain control of Léogâne and Jacmel, two very important cities in the south.

Once the slave forces laid waste to the plantations of the whites, they took vital supplies, including weapons, which were then used to attack other plantations.

It’s been estimated that in the early few weeks of the Haitian Revolution, the damage done was in the region of 2-3 million francs.

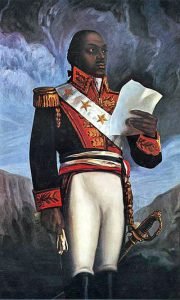

Toussaint Louverture leads the slave revolt

A very determined and ambitious man, Toussaint Louverture, although born a slave, had some sort of privileges that his fellow slaves did not have. For starters, he was allowed to read and write, things that permanently changed how he viewed the world. It’s said that he had a very endearing personality, making him a likable figure by the plantation administrators and managers.

There were some few cases where some slaves managed to escape slavery either by mounting a successful runaway or by using their wits and remarkable enterprise to buy their freedom. One of such former slaves was Toussaint Louverture. Born a slave, Louverture once stated that nature blessed him with the soul of a free man.

Born to slave parents around 1743, Louverture was raised on a plantation in Haut de Cap in Saint-Domingue. His charming personality made very likable to the plantation owner and administrator, including Bavon de Libertad who gave him access the young slave access to his personal library. It’s said that Toussaint was allowed to gain some bit of education, and it’s most likely that he came into contact with some works of early Enlightenment philosophers and writers like Guillaume Raynal. Those Enlightenment ideas of liberty and freedom undoubtedly permanently changed Toussaint.

However, Toussaint, like many of the few educated free and educated people of color in Saint-Domingue, felt those French Enlightenment writers and philosophers fell short in advocating for freedom and liberty for black people and people of mixed race in the various French colonies. It is said that Toussaint straddled both worlds of “enlightened folks” and “ignorant folks”.

He believed that true liberation of enslaved Africans could only come when the divide between those two worlds has been bridged. He certainly did not consider Western Enlightened ideas as innately superior to the culture and collective knowledge of enslaved Africans. Instead, he reasoned that both cultures could merged into one.

As a free man, he impressed the white and mixed-race population with his organizational prowess, which augured well for the few business ventures he tried to establish.

Born into slavery, Toussaint Louverture ultimately gained his freedom through sheer wits and enterprise. As a free man, he impressed impressed the white and mixed-race population with his organizational prowess, which augured well for the few business ventures he tried to establish. Image: An engraving of Louverture

March 1792: The National Assembly grants full civil protections to free men of color

By the beginning of 1792, about 30% of Saint-Domingue was in the hands of the slave rebels. Eager to bring down tensions in the colony, the National Assembly in March of that year quickly granted full civil protections to all free men of color in French colonies. Lawmakers in Paris hoped that such a gesture would pacify the slave rebels a bit.

The island’s new governor Léger-Félicité Sonthonax abolishes slavery in the north

The Assembly also sent over 5,500 French troops to the island to restore order. And as a sign of good faith, Paris also appointed a new governor for the island – in the person of Léger-Félicité Sonthonax. Known for his long stance against slavery, Sonthonax first action taken was to abolish slavery in the Northern Province. As expected, the white slave-owning class were furious.

French commissioner and abolitionist Léger-Félicité Sonthonax

Outbreak of French Revolutionary Wars adds fuel to the Haitian Revolution

Spanning from 1792 to 1802, the French Revolutionary Wars refer to a series of bloody conflicts between Revolutionary France and European monarchies at the time, including Britain, Russia, Prussia, and Austria. Those European monarchies were fighting against France in a bid to halt the spread of revolutionary ideas that were poised to bring down the monarchies in those countries.

In the Declaration of Pillnitz (on August 27, 1791), Austrian and Prussian monarchies vowed to punish France severely should something bad happen to France’s King Louis XVI and his royal family. Britain and other European monarchies took similar stance. France then went on to declare war on those European nations, marking the beginning of the French Revolutionary Wars. Making matters were the executions of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette in January and October 1793, respectively.

Cap-Haïtien, also known as Le Cap (Le Cap Français), was a vibrant port in the northern part of Saint-Domingue. Nicknamed “the Paris of the Antilles”, Le Cap was the economic powerhouse of the island. It boasted many fine residential houses that housed the aristocratic whites. Image: Fire of Cap Français, 21 June 1793

European powers court slave-owning class in Saint-Domingue

Spain and other European powers tried to court political dissenters in Saint-Domingue, hoping that the instability created on the island would affect the riches that were generated by France from the island, which in turn were used by the French revolutionaries to fight Spain and other powers in Europe.

Aggrieved by the National Assembly’s recent concessions made to people of color, the plantation class on the island decided to enter into an alliance with the British. This move was seen by the French revolutionaries as nothing short of treason.

The grands blancs on the island invited the British to also help put down the rebellion. Many of the whites hoped that should the island fall to the control of Britain, slavery would be restored in the north. Moreover, Britain as well as many other European countries were wary of slave revolt spreading to other parts of the Caribbean. Likewise, the United States, especially the slave-owning class in the south, was concerned about the unfolding events in Saint-Domingue. Basically, the breakout of the Haitian Revolution made many European powers nervous.

Britain and Spain could easily send forces, weapons, medicine and other provisions from their colonies – Jamaica and Santo Domingo (i.e. the eastern part of the island of Hispaniola and now the Dominican Republic), respectively. In the first few years of the revolution, British forces were able to overpower French forces and restore slavery wherever they went.

1794 – France’s National Assembly abolishes slavery in all its colonies

With the island descending into a civil war, the two French commissioners on the island – Léger-Félicité Sonthonax and Étienne Polverel – hoped to gain an edge by abolishing slavery in both the western and southern provinces, respectively. Enslaved Africans on the island managed to portray themselves as the true republicans – people who simply wanted their freedom. The leaders of the slave revolt maintained that they had the same ideals that coursed through the blood of the French Revolutionaries.

In 1794, the French National Assembly confirmed the decision of both Sonthonax and Polverel, proceeding to abolishing slavery in all of France’s overseas colonies. The Assembly hoped that such a profound gesture would be enough to convince slave rebels to join the French army.

Louverture changes alliance

Despite France’s abolishing of slavery in all its colonies, Toussaint Louverture, the general of the rebel forces, did not instantly join the French army. Louverture continued to fight against the French until May 1794, when he turned against Spain. The rebel general stated that he was always willing to align with any nation that promoted the rights of slaves as well as abolished slavery. His vision for Saint-Domingue was to have equality for all, regardless of race or color. At the time, he insisted that he and his forces were not fighting for independence from France.

In late 1795, Britain decided to send a fleet of British ships carrying over 28,000 men to Saint-Domingue. Britain’s goal was to conquer all of the island. British forces suffered immense losses due to many tropical diseases and the outbreak of yellow fever. They were given no respite as Toussaint and the mixed-race General André Rigaud consistently managed to halt them in their tracks. Toussaint had successfully trained former slaves, many of with no military background, into a fierce fighting force capable of mounting very successful guerilla warfare attacks.

British officer Thomas Maitland meeting with General Louverture (far left) to negotiate

Defeats after defeats caused the public in England to begin to call for a withdrawal of British forces from Saint-Domingue. Toussaint had even threatened to invade Britain’s Jamaica colony. With every city that Toussaint and his forces took, the morale in the British camp dropped.

In late August 1798, Toussaint signed treaty with Britain, stating that in exchange for Britain’s complete withdrawal from Saint-Domingue, he promised not to support any slave rebellion in Jamaica.

By the time they had withdrawn from the French colony in 1798, Britain had sunk more than 3.5 million pounds into the expedition. They also suffered more than 95,000 casualties.

Toussaint, aka “the Black Napoleon”, declares himself Governor-General for Life

With the British forces driven out of Saint-Domingue, Toussaint and his ally Rigaud became the two leading generals of the French colony. In the months that followed, the former slave-turned general became very suspicious of Riguad. The two generals faced off against each other at the War of Knives (June 1799 – July 1800), which saw Toussaint emerge victorious. That victory meant that Toussaint became the de facto leader of the whole of the Saint-Domingue, while Rigaud committed himself into exile.

With slight support from the United States during his victory over Rigaud, Toussaint emerged as the island’s dictator. The general who had been born into slavery and then became a free man came to be known as “the Black Napoleon” for his astute military skills and bravery. His military brilliance and the feats that he chalked make him one of the most renowned black generals of all time.

Toussaint was one of those few military generals that also gifted politicians. He expertly displays his political prowess in a carefully orchestrated political maneuver that forces many of his political rivals out of Saint-Domingue. In the first few years, Toussaint knew when and with whom to develop alliances in order to advance his cause of securing freedom for all enslaved people on the island.

Once General Louverture attained full control of the island, he made sure to hold on to power, preventing any interference from France. In the constitution he wrote for Saint-Domingue, the general proclaimed himself governor-for-life.

As dictator of Saint-Domingo, Toussaint issued a constitution for the territory in 1801. It was in that constitution that he proclaimed himself governor-for-life. He also proclaimed the first black independent republic. On the other side of the Atlantic, France’s new leader Napoleon Bonaparte was furious with not just the loss a rich colony as Saint-Domingo but with Toussaint’s recent proclamations. The stage was set for the clash of Napoleon and Toussaint.

To maintain his dictatorial rule over Saint-Domingue, Toussaint took to either destroying or deporting his critics, including the very popular French civil commissioner Sonthonax. The anti-slavery colonial official was exiled in 1797.

Toussaint’s reputation among the former slaves took some major hits as he tried to rebuild the devastated economy. He forced a very reluctant population to return to the sugarcane field and restart export of sugar. Bringing the economy back to life was very important in order to maintain the island’s new found civil and political freedom. However, many of the former slaves found Toussaint’s orders a lot more like slavery; they wanted to grow crops for food rather than for export. This and many more factors affected the general’s ability to fend off a French invasion.

The Toussaint-Napoleon showdown

Both Toussaint and Napoleon shared a lot of things in common. Both men came from humble beginnings, and armed with sheer determination and bravery, both men distinguished themselves brilliantly. They both became astute political leaders as a result of their military feats. Therefore it came as no surprise when Napoleon dispatched a large French expeditionary force to Saint-Domingue in 1801.

The French expeditionary force, which was led by Napoleon’s brother-in-law, Gen. Charles Leclerc, was tasked to bring Saint-Domingue back into the control of France. Beneath all of that, laid a sinister plot to have slavery restored to the island and bring Toussaint into custody, or killed. Napoleon, who despite the various disagreements he had with Toussaint, had some bit of admiration for the black general. Game does indeed recognize game!

Image: The Emperor Napoleon in His Study at the Tuileries, by French painter Jacques-Louis David, 1812

Still sour about their loss to Toussaint, Rigaud and Alexandre Pétion joined forces with the invading French force. After arriving (on February 2, 1802), Gen. Leclerc order Toussaint and his generals to surrender the city of Le Cap to the French. Fully aware of the might of the French troops, the Haitian forces refused to do so, and would rather burn the city instead of handing it over to the invading forces.

Toussaint to one of his generals Jean-Jacques Dessalines

Toussaint order his lieutenants to employ scorched-earth tactics, burning towns and plantations in order to deprive the French army access to provisions. When the opportunity presented itself, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, one of Toussaint’s lieutenants, unleashed violence on French settlements, including burning down Léogâne. Haitian forces targeted only white French. They simply refused to relinquish their recently found freedom back to the French. For this, they were willing to put their body on the line and even die.

The Haitian forces suffered a number of defeats, including at the Battle of Crête-à-Pierrot in March 1802. In that particular battle, Toussaint lost about 1400 men, while the French suffered a little bit over 200 casualties.

General Charles Emmanuel Leclerc was dispatched by Napoleon take back control of the island of Saint-Domingue

As the French bombarded the Haitians, the defiant Haitian soldiers sang songs of the French Revolution. At some point, the French soldiers began to see the double standard nature of their military commanders. Many wondered why they were trying to put down a group of enslaved people fighting for their liberty.

The French forces were clearly better equipped than the Haitians, who resorted to the use of guerrilla tactics. Come the rainy season, the French forces had to contend with tropical diseases like malaria and yellow fever. The latter claimed over 4500 French troops.

After three months of intense fighting, Toussaint suffered a huge blow: One of his lieutenants, Christophe, defected in late April 1802. Perhaps Christophe and many other Haitians had grown frustrated by Toussaint’s decision to revive the sugarcane farms. Toussaint was left with lackluster support from the island’s population.

The French army led by General Le Clerc lands in Cap Français (1802)

May 6, 1802: Toussaint surrenders to the French Army

With the tides turning against him, Toussaint Louverture decided to surrender. The French promised to treat the Haitian general with respect. Toussaint was also promised that he could keep his freedom provided he integrated his forces into the French army.

Gen. Leclerc also promised that slavery would not be restored in Saint-Domingue. On May 6, 1802, Toussaint handed his sword to the French, bringing an end to his resistance. Once in custody, Toussaint bemoaned the manner in which he was treated, stating that he was treated like a criminal.

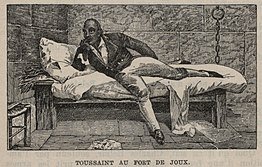

Illustration of Louverture imprisoned at the Fort-de-Joux in France, where he died in 1803.

As it turned, the French had deceived Toussaint; they reneged on their promises, imprisoned Toussaint and sent him to France. The black general died in a freezing cell (at Fort-de-Joux) in the Jura Mountains of France in 1803.

Toussaint Louverture supported the anti-colonial revolution and anti-slavery revolution right to the bitter end.

Jean-Jacques Dessalines carries on the torch

When news of the death of Toussaint reached the island, the Haitian forces were certainly sad. However, many of their generals continued to corporate with the French Army, with Jean-Jacques Dessalines becoming the governor of Saint-Domingue. The Haitians were okay so long as France did not try to re-impose slavery on them.

Unbeknownst to them, Napoleon had different ideas. The removal of slave labor made Saint-Domingue not so profitable. Therefore, Napoleon reinstated slavery. Soon, Haitian forces took up arms again and prepared to fight for their freedom and liberty.

Pétion and Dessalines joined forces and led Haitian troops to fight against the French Army. By this time, Napoleon’s French forces were so depleted that he had to send about 5,000 Polish forces to support Gen. Leclerc. The Polish soldiers had been lied to about their mission. They were told that they were on the island to put down a prison revolt. Upon realizing that Napoleon and his generals had lied to them, the turned their guns against the French. The Poles began fighting alongside the Haitians.

Making matters worse for the French Army was the death of their commander Gen. Leclerc, who died of yellow fever on November 2, 1802. He was succeeded by Vicomte de Rochambeau, whose ruthless tactics made him very infamous. To say the French general committed war crimes would be an understatement. In response, Dessalines followed suit, killing almost every white that he came into contact with. Both sides committed unspeakable atrocities against the other.

In the end, Dessalines emerged the victor, as French Army continued to suffer from yellow fever and low morale. The final showdown took place at the Battle of Vertières on November 18, 1803. The French few remaining French forces and towns surrendered to the British in order to avoid suffering at the hand of the Haitians.

Dessalines declares Haiti’s independence

After more than 12 years of fighting, Haitian slaves had successfully won their freedoms and forced their masters, i.e. France, out of Saint-Domingue. Following the defeat, Napoleon abandoned his quest to have a slice of the Americas by selling the French possession of Louisiana territory to the United States in April 1803. The French leader wanted to focus solely on the raging war in Europe, i.e. the Napoleonic Wars . Great Britain and the rest of Europe certainly welcomed the news of Napoleon’s loss of Saint-Domingue.

For his bravery and military feats against the French, Dessalines etched his name, alongside Toussaint, as one of the greatest black military generals of all time.

On January 1, 1804, Dessalines, flanked by his lieutenants, declared the independence of Haiti. The new republic was renamed “Haiti”, a name derived from the indigenous Arawak. It was now up to Dessalines and his advisors to pick up the pieces and restore the island to its former glory. However, Dessalines and the various leaders that followed miserably failed to do so. The country’s devastated economy could not be revived as post-revolutionary political infighting became the order of the day.

Jean-Jacques Dessalines (1758-1806) took command of the rebel forces following the imprisonment of Toussaint Louverture. The general went on to become the first ruler of an independent Haiti. He later became Emperor of Haiti, ruling from 1804 to 1806, when he was assassinated.

Like Toussaint Louverture, Dessalines tried to kick start the economy by forcing Haitians to go back to the plantations. It was almost similar to serfdom. Haitians decried the economic system, comparing to it to slavery. As he was in constant fear of the return of France or other European nation to the island, he sought to invest heavily in the military. About 10% of young fit men of the population were placed in the military. This took away vital resources from the plantations.

Frustrated with his policies, Dessalines was assassinated, and Henri Christophe and Alexandre Pétion took over the mantle. Christophe’s sphere of control was the north, while Pétion served as the leader of the south, which was mainly made up of mulattos. For several years, both sides to claim the other’s territory until Jean-Pierre Boyer successfully reunited the two states under his rule in 1820.

The 1804 massacre of white French and their loyalists

Following the defeat of France and the subsequent declaration of independence, General Jean-Jacques Dessalines encouraged the massacre of all remaining white French and their loyalists. Image: An 1806 engraving of Jean-Jacques Dessalines. It depicts the general, sword raised in one arm, while the other holds a severed head of a white woman.

After the declaration of independence in 1804, Haitian leaders sought revenge on all the whites that remained on the island. Known today as the 1804 Haiti massacre, the rampage was championed by Dessalines, who called the French colonists savage human beings and enemies of the revolution.

Mathurin Boisrond-Tonnerre and the 1804 massacre of the French

From February 1804 to April 1804, mass killings and rape took place across Haiti. The death toll was in region of 4,000. As he considered the French as the real threat to the new nation, Dessalines’ goal was to remove the white French population from Haiti.

Jean-Jacques Dessalines, who had declared himself emperor of Haiti, was assassinated on 17 October 1806. As first ruler of an independent Haiti, Jean-Jacques Dessalines has been referred to as the father of the nation of Haiti. Image: Assassination of Jean-Jacques Dessalines

How reparations to France and economic isolation permanently devastated Haiti

In 1825, King Charles X of France asked Haiti to pay a whopping 150 million gold francs in compensation for France’s loss of the colony. The monies were intended to go to French ex-slaveholders. Then Haitian president Jean-Pierre Boyer negotiated and was able to bring the indemnity down to 90 million gold francs. In exchange, France renounced all its claim to Haiti. At the time, the Haitian leader hoped that paying the indemnity would dispel all fears of France ever returning to retake the island.

The small Latin American country struggled to pay the indemnity, which ultimately bankrupted the country. Many have blamed those reparations for Haiti’s ill fortunes post-independence. Haiti’s poor economic situation helped fuel even more political instability in the years that followed.

Also, it must be noted that in the immediate aftermath of Haiti’s independence, many nations, especially the United States, wanted the new republic to fail miserably. A thriving republic formed by ex-slaves did not look good on countries that continued the slavery system. This explains why then-U.S. President Thomas Jefferson imposed economic sanctions on Haiti. And it was not until 1862 that the United States recognized Haiti.

Haiti becomes the haven for escaped slaves and freedom fighters

Following Haiti’s independence, the country promoted itself as the haven for former slaves and oppressed black Africans. Assurances of freedom and liberty were given to any slave that landed on the shores of Haiti. The leaders of Haiti worked very hard to integrate those people into the Haitian society. Haiti also offered aid to European colonies that were willing and ready to begin an uprising.

Haiti also took to the habit of granting asylum to revolutionary fighters across the globe. Notable freedom fighters that received aid and support from Haiti include Venezuelan revolutionaries Simón Bolívar and Francisco de Miranda, and Mexican nationalists José Joaquín de Herrera and Francisco Javier Mina.

RELATED: Causes and Major Outcomes of the Mexican Revolution

- For their contributions in the latter part of the Haitian Revolution, the Polish forces that switched side and joined the Haitians came to be termed as the “the White Negroes of Europe”. And when Haiti finally gained independence in 1804, those Polish forces were allowed to acquire Haitian citizenship.

- After Napoleon reinstated slavery in the French colonies in 1803, the French continued to practice the slavery system until 1848, when it was permanently outlawed.

Why Napoleon was bent on restoring slavery to Haiti?

The reason why Napoleon badly needed to restore slavery to Saint-Domingue was because the island extremely profitable sugar production could only remain profitable when the labor used was slave labor.

How many people lost their lives due to the Haitian Revolution?

Image: The 1804 Haiti massacre of whites

It’s been estimated that the Haitian Revolution claimed the lives of close to half a million Haitians and at least 100,000 European troops, including about 40,000 British. Yellow fever, a viral disease that was already a big culprit to the low mortality rates of enslaved Africans in Saint-Domingue, caused more deaths than the deaths on the battle field.

Other Major Outcomes of the Haitian Revolution

In quite a number of ways, the Haitian Revolution proved to be a niggling wrench in the works of Napoleon as he attempted to establish a French Empire in the Americas. Many historians claim that Napoleon’s decision to sell the Louisiana territory, i.e. France’s vast North American territory, to the U.S. [in the Louisiana Purchase deal of 1803] was as a result of Haitian Revolution. However, just as slavery came to an end in Haiti, slavery was expanded by the Americans into those newly acquired Louisiana territories.

Regardless, the fierce and long-fought struggle put up by Toussaint Louverture and his abled generals during the Haitian Revolution did indeed send shivers down the spines of many European powers and even the United States at the time. In the years that followed after France had abolished slavery in all its territories, Britain followed suit and brought an end to the transatlantic slave trade. The United States, on the other hand, took another 60 or so years to abolish slavery. There is no doubt that all those progresses would not have been chalked had it not been for the daring actions of those enslaved Haitians – brave men and women who were willing to face dangers and even death to gain and keep their freedom and liberty.

What were the early leaders of the Haitian Revolution truly fighting for?

Early leaders of the Haitian Revolution demanded freedom not independence from France. Image (L-R): Haitian leaders of the Revolution – George Biassou, Vincent Ogé, André Rigaud, Toussaint Louverture, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, and Henri Christophe

Early leaders of the revolution made it categorically clear that they were not fighting for independence from France; instead, they were fighting for the end of slavery. Many of the rebels even believed that their cause would catch the attention of Louis XIV, who would then step in and decree the end of slavery.

Why was Saint-Domingue called the Pearl of the Antilles?

The French colony of Saint-Dominigue, which occupied the western part of Hispaniola, was the most successful overseas French possession at the time. Known as the Pearl of the Antilles, the island raked in enormous amounts of profits from its vast sugar and coffee plantations. At the time, the former was seen as the item that greased the wheel of the world’s economy. Therefore, Saint-Domingue was a valuable asset which the French was ready to fight tooth and nail to keep.

The economic value of the sugar and other commodity crops shipped from Saint-Domingue was said to be the equivalent of all the crops shipped from the Thirteen American Colonies to Great Britain. The French colony was undoubtedly the richest colony in the Caribbean in the late 18th century.

Tags: André Rigaud Black history French Revolution George Biassou Haiti Haitian Revolution Henri Christophe Hispaniola Jean-Jacques Dessalines Napoleon Bonaparte Saint-Domingue Slave revolts Slavery Toussaint L'Ouverture Vincent Ogé

- Pingbacks 0

Thank you so much for all your hard work and research. The cataloging of true history is more important than ever, and hopefully we learn to enjoy justice.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Next story What was the Great Chicago Fire? – Causes and Cost

- Previous story Onesimus: The enslaved African who introduced inoculation to the United States

- Popular Posts

- Recent Posts

How did the Garuda become Thailand’s national and royal emblem?

History of Thailand and how it avoided European colonization

Life, Political Career and Accomplishments of William Pitt the Younger

Most Historic Joint Session of the United States Congress

History of the Tang dynasty and why it is considered the Golden Age in Chinese history

Greatest African Leaders of all Time

Queen Elizabeth II: 10 Major Achievements

Donald Trump’s Educational Background

Donald Trump: 10 Most Significant Achievements

8 Most Important Achievements of John F. Kennedy

Odin in Norse Mythology: Origin Story, Meaning and Symbols

Ragnar Lothbrok – History, Facts & Legendary Achievements

9 Great Achievements of Queen Victoria

12 Most Influential Presidents of the United States

Most Ruthless African Dictators of All Time

Kwame Nkrumah: History, Major Facts & 10 Memorable Achievements

Greek God Hermes: Myths, Powers and Early Portrayals

8 Major Achievements of Rosa Parks

10 Most Famous Pharaohs of Egypt

How did Captain James Cook die?

Kamala Harris: 10 Major Achievements

Poseidon: Myths and Facts about the Greek God of the Sea

How and when was Morse Code Invented?

Nile River: Location, Importance & Major Facts

The Exact Relationship between Elizabeth II and Elizabeth I

- Adolf Hitler Alexander the Great American Civil War Ancient Egyptian gods Ancient Egyptian religion Apollo Athena Athens Black history Carthage China Civil Rights Movement Cold War Constantine the Great Constantinople Egypt England France Germany Ghana Hera Horus India Isis John Adams Julius Caesar Loki Military Generals Military History Nobel Peace Prize Odin Osiris Pan-Africanism Queen Elizabeth I Ra Ragnarök Religion Set (Seth) Soviet Union Thor Timeline Women’s History World War I World War II Zeus

History Cooperative

The Haitian Revolution: The Slave Revolt Timeline in the Fight for Independence

The end of the 18th century was a period of great change around the world.

By 1776, Britain’s colonies in America — fueled by revolutionary rhetoric and Enlightenment thought that challenged the existing ideas about government and power — revolted and overthrew what many considered to be the most powerful nation in the world. And thus, the United States of America was born.

In 1789, it was the people of France that overthrew their monarchy; one that had been in power for centuries, shaking the foundations of the Western world. With it, the République Française was created.

However, while the American and French Revolutions represented a historic shift in world politics, they were, perhaps, still not the most revolutionary movements of the time . They purported to be driven by ideals that all people were equal and deserving of freedom, yet both ignored stark inequalities in their own social orders — slavery persisted in America while the new French ruling elite continued to ignore the French working class, a group known as the sans-culottes .

The Haitian Revolution, though, was led and executed by slaves, and it sought to create a society that was truly equal.

Its success challenged notions of race at the time. Most Whites thought that Blacks were simply too savage and too stupid to run things on their own. Of course, this is a ludicrous and racist notion, but at the time, the ability of Haitian slaves to rise up against the injustices they faced and break free from bondage was the true revolution — one that played just as much of a role in reshaping the world as any other 18th century social upheaval.

Unfortunately, though, this story has been lost to most people outside of Haiti.

Notions of exceptionalism keep us from studying this historic moment, something that must change if we are to better understand the world in which we live today.

Haiti Before the Revolution

Saint domingue.

Saint Domingue was the French portion of the Carribean island of Hispaniola, which was discovered by Christopher Columbus in 1492.

Since the French took it over with the Treaty of Rijswijk in 1697 — the result of the Nine Years’ War between France and the Grand Alliance, with Spain ceding the territory — it became the most economically important asset among the country’s colonies. By 1780, two thirds of France’s investments were based in Saint Domingue.

So, what made it so prosperous? Why, those age-old addictive substances, sugar and coffee, and the European socialites who were beginning to consume them by the bucketload with their shiny, new coffeehouse culture .

At that time, no less than half of the sugar and coffee consumed by Europeans was sourced from the island. Indigo and cotton were other cash crops which brought wealth to France via these colonial plantations, but in nowhere near as great numbers.

READ MORE: Who Invented the Cotton Gin? Eli Whitney and Cotton Gin Impact on America

And who should be slaving away (pun intended) in the sweltering heat of this tropical Carribean island, so as to ensure satisfaction for such sweet-tooth having European consumers and profit-making French polity?

African slaves taken forcibly from their villages.

By the time just before the Haitain Revolution began, 30,000 new slaves were coming into Saint Domingue every year . And that’s because the conditions were so harsh, so terrible — with things like nasty diseases especially dangerous to those who had never been exposed to them present, such as yellow fever and malaria — that half of them died within only a year of arriving.

Viewed, of course, as property and not as human beings, they did not have access to basic needs like adequate food, shelter, or clothing.

And they worked hard. Sugar became all the rage — the most in-demand commodity — across Europe.

But to meet the ravenous demand of the moneyed class on the continent, African slaves were being coerced into labor under the threat of death — enduring the dueling horrors of the tropical sun and weather, alongside blood-curlingly cruel working conditions in which slave drivers used violence to meet quotas at essentially any cost.

Social Structure

As was the norm, these slaves were at the very bottom of the social pyramid that developed in colonial Saint Domingue, and were most certainly not citizens (if they were even considered as a legitimate part of society at all).

But though they had the least structural power, they made up the majority of the population: in 1789, there were 452,000 Black slaves there, mostly from West Africa. This accounted for 87% of the population of Saint Domingue at the time.

Right above them in the social hierarchy were free people of color — former slaves who became free, or children of free Blacks — and people of mixed race, often called “mulattoes” (a derogatory term alikening mixed race individuals to half-breed mules), with both groups equaling around 28,000 free people — equal to around 5% of the colony’s population in 1798.

The next highest class were the 40,000 White people who lived on Saint Domingue — but even this segment of society was far from equal. Of this group, the plantation owners were the richest and the most powerful. They were called grand blancs and some of them did not even remain permanently in the colony, but instead traveled back to France to escape the risks of disease.

Just below them were the administrators who kept order in the new society, and below them were the petit blancs or the Whites who were mere artisans, merchants, or small professionals.

Wealth in the colony of Saint Domingue — 75% of it to be exact — was condensed in the White population, despite it making up only 8% of the colony’s total population. But even within the White social class, most of this wealth was condensed with the grand blancs, adding another layer to the inequality of Haitian society (2).

Building Tension

Already at this time there were tensions brewing between all of these different classes. Inequality and injustice were seething in the air, and manifesting in every facet of life.

To add to it, once in a while masters decided to be nice and let their slaves have a “slavecation” for a short time to release some tension — you know, to blow off some steam. They hid out in the hillsides away from Whites, and, along with escapee slaves (referred to as maroons ), tried to rebel a few times.

Their efforts weren’t rewarded and they failed to achieve anything significant, as they weren’t organized enough yet, but these attempts show that there was a stirring which occurred before the onset of the Revolution.

Treatment of slaves was unnecessarily cruel, and masters often made examples in order to terrorize other slaves by killing or punishing them in extremely inhumane ways — hands were chopped off, or tongues cut out; they were left to roast to death in the scalding sun, shackled to a cross; their rectums were filled with gun powder so that spectators could watch them explode.

The conditions were so bad in Saint Domingue that the death rate actually exceeded the birth rate. Something that is important, because a new influx of slaves was constantly flowing in from Africa, and they were usually brought from the same regions: like Yoruba, Fon, and Kongo.

Therefore, there was not much of a new African-colonial culture which developed. Instead, African cultures and traditions remained largely intact. The slaves could communicate well with each other, privately, and carry on their religious beliefs.

They made their own religion, Vodou (more commonly known as Voodoo ), which mixed in a bit of Catholicism with their African traditional religions, and developed a creole that mixed French with their other languages to communicate with the White slave owners.

The slaves who were brought in directly from Africa were less submissive than those who were born into slavery in the colony. And since there were more of the former, it could be said that rebellion was already bubbling in their blood.

The Enlightenment

Meanwhile, back in Europe, the Era of Enlightenment was revolutionizing thoughts about humanity, society, and how equality could fit in with all of that. Sometimes slavery was even attacked in the writings of Enlightenment thinkers, such as with Guillaume Raynal who wrote about the history of European colonization.

As a result of the French Revolution, a highly important document called the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen was created in August of 1789. Influenced by Thomas Jefferson — Founding Father and third president of the United States — and the recently created American Declaration of Independence , it espoused the moral rights of freedom, justice, and equality for all citizens. It did not specify that people of color or women, or even people in the colonies, would count as citizens, however.

And this is where the plot thickens.

The petit blancs of Saint Domingue who had no power in colonial society — and who had perhaps escaped Europe for the New World, in order to gain a chance at a new status in a new social order — connected with the ideology of Enlightenment and Revolutionary thinking. The people of mixed-race from the colony also used Enlightenment philosophy to inspire greater social access.

This middle group was not made up of slaves; they were free, but they were not legally citizens either, and as a result they were barred legally from certain rights.

One free Black man by the name of Toussaint L’Ouverture — a former slave turned prominent Haitian general in the French Army — began making this connection between the Enlightenment ideals populating in Europe, particularly in France, and what they could mean in the colonial world.

Throughout the 1790s, L’Ouverture began making more speeches and declarations against inequalities, becoming an avid supporter of the complete abolition of slavery in all of France. Increasingly, he began taking on more and more roles to support freedom in Haiti, until he eventually began recruiting and supporting rebellious slaves.

Due to his prominence, throughout the Revolution, L’Ouverture was an important liaison between the people of Haiti and the French government — though his dedication to ending slavery drove him to switch allegiances several times, a trait which has become an integral part of his legacy.

You see, the French, who were adamantly fighting for liberty and justice for all, had not yet considered what implications these ideals could have on colonialism and on slavery — how these ideals they were spouting would perhaps mean even more to a slave held captive and brutally treated, than to a guy who couldn’t vote because he wasn’t rich enough.

The Revolution

The legendary bois caïman ceremony.

On a stormy night in August of 1791, after months of careful planning, thousands of slaves held a secret Vodou ceremony at Bois Caïman in the north of Morne-Rouge, a region in the northern part of Haiti. Maroons, house slaves, field slaves, free Blacks, and people of mixed-race all gathered to chant and dance to ritual drumming.

Originally from Senegal, a former commandeur (meaning “slave driver”) who had become a maroon and Vodou priest — and who was a giant, powerful, grotesque-looking man — named Dutty Boukman, fiercely led this ceremony and the ensuing rebellion. He exclaimed in his famous speech:

“Our God who has ears to hear. You are hidden in the clouds; who watch us from where you are. You see all that the White has made us suffer. The White man’s god asks him to commit crimes. But the god within us wants to do good. Our god, who is so good, so just, He orders us to avenge our wrongs.”

Boukman (so called, because as a “Book Man” he could read) made a distinction that night between the “White man’s God” — who apparently endorsed slavery — and their own God — who was good, fair, and wanted them to rebel and be free.

He was joined by priestess Cecile Fatiman, daughter of an African slave woman and a White Frenchman. She stood out, as a Black woman with long silky hair and distinctly bright green eyes would. She looked the part of a goddess, and the mambo woman (which comes from “mother of magic”) was said to embody one.

A couple of slaves at the ceremony offered themselves up for slaughter, and Boukman and Fatiman also sacrificed a pig plus a couple other animals, slitting their throats. The human and animal’s blood was dispersed to the attendees to drink.

Cecile Fatiman was then supposedly possessed by the Haitian African Warrior Goddess of Love, Erzulie . Erzulie/Fatiman told the group of uprisers to go forth with her spiritual protection; that they would return unharmed.

And go forth, they did.

Infused with the divine energy of the incantations and rituals performed by Boukman and Fatiman, they laid waste to the surrounding area, destroying 1,800 plantations and killing 1,000 slave owners within one week.

Bois Caïman in Context

The Bois Caïman Ceremony is not only considered the starting point of the Haitian Revolution; it is considered by Haitian historians as the reason for its success.

This is due to the potent belief and powerful conviction in the Vodou ritual. In fact, it is still so important that the site is visited even today , once a year, every August 14th.

The historic Vodou ceremony is a symbol to this day of unity for Haitian people who were originally from different African tribes and backgrounds, but came together in the name of freedom and political equality. And this may even extend further to represent unity among all Blacks in the Atlantic ; in the Caribbean islands and Africa.

Furthermore, the legends of the Bois Caïman ceremony are also considered an origin point for the tradition of Haitian Vodou.

Vodou is commonly feared and even misunderstood in Western culture; there is a suspicious atmosphere around the subject matter. Anthropologist, Ira Lowenthal, interestingly posits that this fear exists because it stands for “an unbreakable revolutionary spirit threatening to inspire other Black Caribbean republics — or, God forbid, the United States itself.”

He goes further to suggest that Vodou can even act as a catalyst for racism, confirming racist beliefs that Black people are “scary and dangerous.” In truth, the spirit of the Haitian people, which was formed in tandem with Vodou and the Revolution, is of a human will to “never be conquered again.” The rejection of Vodou as a vicious faith points to embedded fears in American culture of challenges to inequality.

While some are skeptical about the precise details of what took place at the infamous rebellion meeting at Bois Caïman, the story nevertheless presents a crucial turning point in history for Haitians and others of this New World.

The slaves sought vengeance, freedom, and a new political order; the presence of Vodou was of the utmost significance. Before the ceremony, it gave slaves a psychological release and affirmed their own identity and self-existence. During, it served as a cause and as a motivation; that the spirit world wanted them to be free, and they had the protection of said spirits.

As a result, it has helped to shape Haitian culture even until today, prevailing as the dominant spiritual guide in daily life, and even medicine.

The Revolution Begins

The onset of the Revolution, kicked off by the Bois Caïman ceremony, was strategically planned by Boukman. The slaves began by burning plantations and killing Whites in the North, and, as they went along, they attracted others in bondage to join their rebellion.

Once they had a couple thousand in their ranks, they disbanded into smaller groups and branched out to attack more plantations, as pre-planned by Boukman.

Some Whites who were warned ahead of time fled to Le Cap — the central political hub of Saint Domingue, where control over the city would likely determine the outcome of the Revolution — leaving their plantations behind, but trying to save their lives.

The slave forces were held back a bit at the onset, but each time they retreated only into the nearby mountains to reorganize themselves before attacking again. Meanwhile, about 15,000 slaves had joined the rebellion at this point, some systematically burning down all plantations in the North — and they hadn’t even gotten to the South yet.

The French sent in 6,000 troops as an attempt for redemption, but half of the force was killed off just like flies, as the slaves went forth. It is said that, although more and more Frenchmen kept arriving on the island, they only came to die, as the former slaves slaughtered them all.

But eventually they managed to capture Dutty Boukman. They put his head on a stick to show the revolutionaries that their hero had been taken.

(Cecile Fatiman, however, could not be found anywhere. She later went on to marry Michelle Pirouette — who became president of the Haitian Revolutionary Army — and died at the ripe old age of 112.)

The French Respond; Britain and Spain Get Involved

Needless to say, the French had started to realize that their greatest colonial asset was beginning to slip through their fingers. They also happened to be in the midst of their own Revolution — something that deeply affected the Haitian’s perspective; believing that they too deserved the same equality espoused by the new leaders of France.

At the same time, in 1793, France declared war on Great Britain, and both Britain and Spain — which controlled the other portion of the island of Hispaniola — entered the conflict.

The British believed that they could make some extra profit by occupying Saint-Domingue and that they would have more bargaining power during peace treaties to end their war with France. They wanted to reinstate slavery for these reasons (and also to prevent slaves in their own Carribean colonies from getting too many ideas for rebellion).

By September of 1793, their navy took over a French fort on the island.

At this point, the French really began to panic, and decided to abolish slavery — not only in Saint Domingue, but in all of their colonies. At a National Convention in February 1794, as a result of the panic ensuing from the Haitian Revolution, they declared that all men, regardless of color, were considered French citizens with constitutional rights.

This really shocked other European nations, as well as the newly born United States. Although the push for including the abolition of slavery in France’s new constitution came from the threat of losing such a great source of wealth, it also set them morally apart from other countries in a time when nationalism was becoming quite the trend.

France felt especially distinguished from Britain — which was contrarily reinstating slavery wherever it landed — and like they would set the example for liberty.

Enter Toussaint L’Ouverture

The most notorious general of the Haitian Revolution was none other than the infamous Toussaint L’Ouverture — a man whose allegiances switched throughout the entirety of the period, in some ways leaving historians pondering his motives and beliefs.

Although the French had just claimed to abolish slavery, he was still suspicious. He joined ranks with the Spanish army and was even made a knight by them. But then he suddenly changed his mind, turning against the Spanish and instead joining the French in 1794.

You see, L’Ouverture didn’t even want independence from France — he just wanted former slaves to be free and have rights. He wanted Whites, some being former slave owners, to stay and rebuild the colony.

His forces were able to drive the Spanish out of Saint Domingue by 1795, and on top of this, he was also dealing with the British. Thankfully, yellow fever — or the “black vomit” as the British called it — was doing much of the resistance work for him. European bodies were much more susceptible to the disease, what with having never been exposed to it before.

12,000 men died from it in just 1794 alone. That’s why the British had to keep sending in more troops, even while they hadn’t fought many battles. In fact, it was so bad that being sent to the West Indies was fast becoming an immediate death sentence, to the point that some soldiers rioted when they learned where they were to be stationed.

The Haitians and the British fought several battles, with wins on either side. But even by 1796, the British were only hanging around Port-au-Prince and rapidly dying off with severe, disgusting illness.

By May of 1798, L’Ouverture met with the British Colonel, Thomas Maitland, to settle an armistice for Port-au-Prince. Once Maitland had withdrawn from the city, the British lost all morale and withdrew from Saint-Domingue altogether. As part of the deal, Matiland asked L’Ouverture to not go riling up the slaves in the British colony of Jamaica, or support a revolution there.

In the end, the British paid the cost of 5 years on Saint Domingue from 1793–1798, four million pounds, 100,000 men, and did not gain much at all to show for it (2).

L’Ouverture’s story seems confusing as he switched allegiences several times, but his real loyalty was to sovereignty and freedom from slavery. He turned against the Spanish in 1794 when they wouldn’t end the institution, and instead fought for and gave control to the French on occasion, working with their general, because he believed that they promised to end it.

He did all this while also being aware that he didn’t want the French to have too much power, recognizing how much control he had in his hands.

In 1801, he made Haiti a sovereign free Black state , appointing himself as governor-for-life. He gave himself absolute rule over the entire island of Hispaniola, and appointed a Constitutional Assembly of Whites.

He had no natural authority to do so, of course, but he had led the Revolutionaries to victory and was making the rules up as he went along.

The story of the Revolution seems like it would end here — with L’Ouverture and the Haitians freed and happy — but alas, it does not.

Enter a new character in the story; somebody who wasn’t so happy with L’Ouverture’s newfound authority and how he had established it without the approval from the French government.

Enter Napoleon Bonaparte

Unfortunately, the creation of a free Black state really pissed off Napoleon Bonaparte — you know, that guy who became Emperor of France during the French Revolution.

In February of 1802, he sent his brother and troops in to reinstate French rule in Haiti. He also secretly — but not-so-secretly — wanted to reinstate slavery.

In quite a devilish manner, Napoleon instructed his comrades to be nice to L’Ouverture and lure him to Le Cap, assuring him that the Haitains would retain their freedom. They planned to then arrest him.

But — by no surprise — L’Ouverture didn’t go when summoned, not falling for the bait.

After that, the game was on. Napoleon decreed that L’Ouverture and General Henri Christophe — another leader in the Revolution who had close allegiances with L’Ouverture — should be outlawed and hunted down.

L’Ouverture kept his nose down, but that didn’t stop him from devising plans.

He instructed the Haitians to burn, destroy, and rampage everything — to show what they were willing to do to resist ever becoming slaves again. He told them to be as violent with their destruction and killings as possible. He wanted to make it hell for the French army, as slavery had been a hell for him and his comrades.

The French were shocked by the gruesome rage brought forth by the previously-enslaved Blacks of Haiti. For the Whites — who felt slavery was the natural position of Blacks — the havoc being wreaked on them was mindbending.

Guess they’d never paused to think how the terrible, grueling existence of slavery could really grind someone down.

Crête-à-Pierrot Fortress

There were many battles then that followed, and great devastation, but one of the most epic conflicts was at Crête-à-Pierrot Fortress in the valley of the Artibonite River.

At first the French were defeated, one army brigade at a time. And all the while, the Haitians sang songs about the French Revolution and how all men have the right to freedom and equality. It angered some Frenchmen, but a few soldiers began to question Napoleon’s intentions and what they were fighting for.

If they were simply fighting to gain control over the colony and not reinstate slavery, then how could a sugar plantation be profitable without the institution?

In the end, though, the Haitains ran out of food and ammunition and had no choice but to retreat. This wasn’t a total loss, as the French had been intimidated and had lost 2,000 among their ranks. What was more, another outbreak of yellow fever struck and took with it another 5,000 men.

The outbreak of disease, combined with the new guerilla tactics the Haitains adopted, began to significantly weaken the French hold on the island.

But, for a short time, they weren’t weakened quite enough. In April of 1802, L’Ouverture made a deal with the French, to trade his own freedom for the freedom of his captured troops. He was then taken and shipped off to France, where he died a few months later in prison.

In his absence, Napoleon ruled Saint-Domingue for two months, and did indeed plan to reinstate slavery.

The Blacks fought back, continuing their guerilla warfare, plundering everything with makeshift weapons and reckless violence, while the French — led by Charles Leclerc — killed the Haitians by the masses.