Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

Asthma articles from across Nature Portfolio

Asthma is a form of bronchial disorder caused by inflammation of the bronchi. It is characterized by spasmodic contraction of airway smooth muscle, difficulty breathing, wheezing and coughing.

Latest Research and Reviews

Association of factors with childhood asthma and allergic diseases using latent class analysis

- Cornelia M. Borkhoff

- Jingqin Zhu

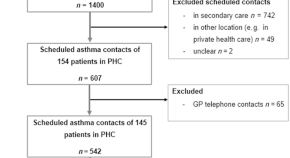

Documentation of comorbidities, lifestyle factors, and asthma management during primary care scheduled asthma contacts

- Jaana Takala

- Iida Vähätalo

- Hannu Kankaanranta

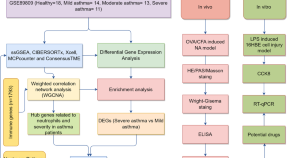

Bronchial epithelial transcriptomics and experimental validation reveal asthma severity-related neutrophilc signatures and potential treatments

Transcriptomic analysis of the airway epithelia in asthma patients identifies several neutrophilic signatures and targets associated with asthma severity, and highlights the potential therapeutic value of Reperixin in managing deteriorating asthma.

- Xinxin Zhang

- Xiufang Huang

Genomic attributes of airway commensal bacteria and mucosa

Systematic culture and genome sequencing of thoracic airway commensal bacteria finds many potential influences on lung health and disease. Polyomics of differentiated airway epithelium also suggest pathways that may sustain host-microbial interactions.

- Leah Cuthbertson

- Ulrike Löber

- William. O. C. Cookson

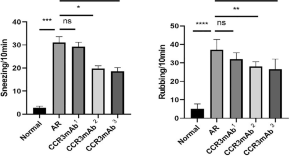

The study of the role of purified anti-mouse CD193 (CCR3) antibody in allergic rhinitis mouse animal models

- Yating Xiao

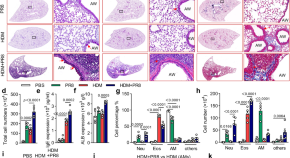

Cullin5 drives experimental asthma exacerbations by modulating alveolar macrophage antiviral immunity

Asthma may be exacerbated by respiratory viral infection, but the cellular and molecular mechanisms are still unclear. Here the authors show, using mouse models of asthma with influenza infection, that asthma-induced cullin5 in alveolar macrophages suppresses IFN-β production to promote neutrophilic inflammation but dampens antiviral immunity.

- Haibo Zhang

News and Comment

Jak1 hits a nerve.

- Stephanie Houston

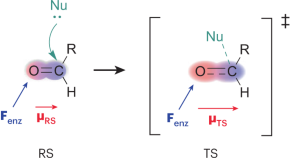

Boosted electrostatic biocatalysis

- Jan-Stefan Völler

Vitamin B-reath easier: vitamin B6 derivatives reduce IL-33 to limit lung inflammation

- Hēth R. Turnquist

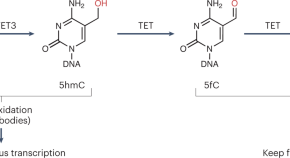

5-hydroxymethylcytosine stabilizes transcription by preventing aberrant initiation in gene bodies

5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) accumulates in transcribed gene regions (called ‘gene bodies’) and near enhancers, but its biological role has remained mysterious. A new study demonstrates that 5hmC serves to counteract inappropriate, spurious intragenic transcription in airway smooth muscle cells and by doing so, this DNA base functions in the prevention of chronic inflammation in the lung and an asthma-like phenotype.

- Gerd P. Pfeifer

Natural mouse microbes transiently block innate responses to allergens

Cohousing pet-store mice with laboratory mice leads to the natural transfer of microbes and subsequent inflammation in laboratory mice. Lung group 2 innate lymphoid cells — rapid responders to airway allergens — are transiently inhibited by inflammatory signals, but their activity recovers once the active infection subsides.

Asthma treatment for those who need it most

A biologic therapy reduces asthma exacerbations in Black and Hispanic children living in urban areas — a group with a disproportionately high asthma burden.

- Karen O’Leary

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Search by keyword

- Search by citation

Page 1 of 2

Psychological distress and associated factors among asthmatic patients in Southern, Ethiopia, 2021

There is an increased prevalence of psychological distress in adults with asthma. Psychological distress describes unpleasant feelings or emotions that impact the level of functioning. It is a significant exac...

- View Full Text

Retrospective assessment of a collaborative digital asthma program for Medicaid-enrolled children in southwest Detroit: reductions in short-acting beta-agonist (SABA) medication use

Real-world evidence for digitally-supported asthma programs among Medicaid-enrolled children remains limited. Using data from a collaborative quality improvement program, we evaluated the impact of a digital i...

Nonadherence to antiasthmatic medications and its predictors among asthmatic patients in public hospitals of Bahir Dar City, North West Ethiopia: using ASK-12 tool

Globally, adequate asthma control is not yet achieved. The main cause of uncontrollability is nonadherence to prescribed medications.

The hen and the egg question in atopic dermatitis: allergy or eczema comes first

Atopic dermatitis (AD) as a chronic inflammatory systemic condition is far more than skin deep. Co-morbidities such as asthma and allergic rhinitis as well as the psychological impact influence seriously the q...

Medication regimen complexity and its impact on medication adherence and asthma control among patients with asthma in Ethiopian referral hospitals

Various studies have found that medication adherence is generally low among patients with asthma, and that the complexity of the regimen may be a potential factor. However, there is no information on the compl...

Monoclonal antibodies targeting small airways: a new perspective for biological therapies in severe asthma

Small airway dysfunction (SAD) in asthma is characterized by the inflammation and narrowing of airways with less of 2 mm in diameter between generations 8 and 23 of the bronchial tree. It is now widely accepte...

Level of asthma control and its determinants among adults living with asthma attending selected public hospitals in northwestern, Ethiopia: using an ordinal logistic regression model

Asthma is a major public health challenge and is characterized by recurrent attacks of breathlessness and wheezing that vary in severity and frequency from person to person. Asthma control is an important meas...

Static lung volumes and diffusion capacity in adults 30 years after being diagnosed with asthma

Long-term follow-up studies of adults with well-characterized asthma are sparse. We aimed to explore static lung volumes and diffusion capacity after 30 + years with asthma.

Over-prescription of short-acting β 2 -agonists and asthma management in the Gulf region: a multicountry observational study

The overuse of short-acting β 2 -agonists (SABA) is associated with poor asthma control. However, data on SABA use in the Gulf region are limited. Herein, we describe SABA prescription practices and clinical outcom...

A serological biomarker of type I collagen degradation is related to a more severe, high neutrophilic, obese asthma subtype

Asthma is a heterogeneous disease; therefore, biomarkers that can assist in the identification of subtypes and direct therapy are highly desirable. Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease that leads to change...

Adherence to inhalers and associated factors among adult asthma patients: an outpatient-based study in a tertiary hospital of Rajshahi, Bangladesh

Adherence to inhaler medication is an important contributor to optimum asthma control along with adequate pharmacotherapy. The objective of the present study was to assess self-reported adherence levels and to...

The link between atopic dermatitis and asthma- immunological imbalance and beyond

Atopic diseases are multifactorial chronic disturbances which may evolve one into another and have overlapping pathogenetic mechanisms. Atopic dermatitis is in most cases the first step towards the development...

The effects of nebulized ketamine and intravenous magnesium sulfate on corticosteroid resistant asthma exacerbation; a randomized clinical trial

Asthma exacerbation is defined as an acute attack of shortness of breath with more than 25% decrease in morning peak flow compared to the baseline on 2 consecutive days, which requires immediate standard thera...

Determinants of asthma in Ethiopia: age and sex matched case control study with special reference to household fuel exposure and housing characteristics

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disorder characterized by airway obstruction and hyper-responsiveness. Studies suggest that household fuel exposure and housing characteristics are associated with air way rela...

Feasibility and acceptability of monitoring personal air pollution exposure with sensors for asthma self-management

Exposure to fine particulate matter (PM 2.5 ) increases the risk of asthma exacerbations, and thus, monitoring personal exposure to PM 2.5 may aid in disease self-management. Low-cost, portable air pollution sensors...

Biological therapy for severe asthma

Around 5–10% of the total asthmatic population suffer from severe or uncontrolled asthma, which is associated with increased mortality and hospitalization, increased health care burden and worse quality of lif...

Treatment outcome clustering patterns correspond to discrete asthma phenotypes in children

Despite widely and regularly used therapy asthma in children is not fully controlled. Recognizing the complexity of asthma phenotypes and endotypes imposed the concept of precision medicine in asthma treatment...

Positive change in asthma control using therapeutic patient education in severe uncontrolled asthma: a one-year prospective study

Severe asthma is difficult to control. Therapeutic patient education enables patients to better understand their disease and cope with treatment, but the effect of therapeutic patient education in severe uncon...

Asthma and COVID-19: a dangerous liaison?

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by the new severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), provoked the most striking international public health crisis of our time. COVI...

Knowledge, attitude, and practice towards COVID-19 among chronic disease patients at Aksum Hospital, Northern Ethiopia, 2020: a cross-sectional study

The Coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak is the first reported case in Wuhan, China in December 2019 and suddenly became a major global health concern. Currently, there is no vaccine and treatment have been repor...

Self-reported vs. objectively assessed adherence to inhaled corticosteroids in asthma

Adherence to inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) in asthma is vital for disease control. However, obtaining reliable and clinically useful measures of adherence remains a major challenge. We investigated the associa...

Association between prevalence of obstructive lung disease and obesity: results from The Vermont Diabetes Information System

The association of obesity with the development of obstructive lung disease, namely asthma and/or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, has been found to be significant in general population studies, and weig...

Changes in quantifiable breathing pattern components predict asthma control: an observational cross-sectional study

Breathing pattern disorders are frequently reported in uncontrolled asthma. At present, this is primarily assessed by questionnaires, which are subjective. Objective measures of breathing pattern components ma...

The role of leukotriene modifying agent treatment in neuropsychiatric events of elderly asthma patients: a nested case control study

In March 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration decided that the dangers related to neuropsychiatric events (NPEs) of montelukast, one of the leukotriene modifying agents (LTMAs), should be communicated thr...

Asthma and stroke: a narrative review

Asthma is a heterogeneous disease, usually characterized by chronic airway inflammation, bronchial reversible obstruction and hyperresponsiveness to direct or indirect stimuli. It is a severe disease causing a...

Comparison of dental caries (DMFT and DMFS indices) between asthmatic patients and control group in Iran: a meta-analysis

The association between caries index, which is diagnosed by Decayed, Missing, and Filled Teeth (DMFT), and asthma has been assessed in several studies, which yielded contradictory results. Meta-analysis is the...

ICS/formoterol in the management of asthma in the clinical practice of pulmonologists: an international survey on GINA strategy

The treatment with short-acting beta-2 agonists (SABA) alone is no longer recommended due to safety issues. Instead, the current Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) Report recommends the use of the combination...

Sustainability of residential environmental interventions and health outcomes in the elderly

Research has documented that housing conditions can negatively impact the health of residents. Asthma has many known indoor environmental triggers including dust, pests, smoke and mold, as evidenced by the 25 ...

Non-adherence to inhaled medications among adult asthmatic patients in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Medication non-adherence is one of a common problem in asthma management and it is the main factor for uncontrolled asthma. It can result in poor asthma control, which leads to decreased quality of life, incre...

The outcome of COVID-19 among the geriatric age group in African countries: protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the outbreak of coronavirus disease in 2019 (COVID-19) has been declared as a pandemic and public health emergency that infected more than 5 million people wor...

Correction to: A comparison of biologicals in the treatment of adults with severe asthma – real-life experiences

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via the original article.

The original article was published in Asthma Research and Practice 2020 6 :2

Disease control in patients with asthma and respiratory symptoms (wheezing, cough) during sleep

The Global Initiative for Asthma ( GINA)-defined criteria for asthma control include questions about daytime symptoms, limitation of activity, nocturnal symptoms, need for reliever treatment and patients’ satisfac...

The burden, admission, and outcomes of COVID-19 among asthmatic patients in Africa: protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis

Coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak is the first reported case in Wuhan, China in December 2019 and suddenly became a major global health concern. According to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Cont...

The healthcare seeking behaviour of adult patients with asthma at Chitungwiza Central Hospital, Zimbabwe

Although asthma is a serious public health concern in Zimbabwe, there is lack of information regarding the decision to seek for healthcare services among patients. This study aimed to determine the health care...

Continuous versus intermittent short-acting β2-agonists nebulization as first-line therapy in hospitalized children with severe asthma exacerbation: a propensity score matching analysis

Short-acting β2-agonist (SABA) nebulization is commonly prescribed for children hospitalized with severe asthma exacerbation. Either intermittent or continuous delivery has been considered safe and efficient. ...

Patient perceived barriers to exercise and their clinical associations in difficult asthma

Exercise is recommended in guidelines for asthma management and has beneficial effects on symptom control, inflammation and lung function in patients with sub-optimally controlled asthma. Despite this, physica...

Asthma management with breath-triggered inhalers: innovation through design

Asthma affects the lives of hundred million people around the World. Despite notable progresses in disease management, asthma control remains largely insufficient worldwide, influencing patients’ wellbeing and...

A nationwide study of asthma correlates among adolescents in Saudi Arabia

Asthma is a chronic airway inflammation disease that is frequently found in children and adolescents with an increasing prevalence. Several studies are linking its presence to many lifestyle and health correla...

A comparison of biologicals in the treatment of adults with severe asthma – real-life experiences

Anti-IgE (omalizumab) and anti-IL5/IL5R (reslizumab, mepolizumab and benralizumab) treatments are available for severe allergic and eosinophilic asthma. In these patients, studies have shown beneficial effects...

The Correction to this article has been published in Asthma Research and Practice 2020 6 :10

Determinants of Acute Asthma Attack among adult asthmatic patients visiting hospitals of Tigray, Ethiopia, 2019: case control study

Acute asthma attack is one of the most common causes of visits to hospital emergency departments in all age groups of the population and accounts for the greater part of healthcare burden from the disease. Des...

Determinants of non-adherence to inhaled steroids in adult asthmatic patients on follow up in referral hospital, Ethiopia: cross-sectional study

Asthma is one of the major non-communicable diseases worldwide. The prevalence of asthma has continuously increased over the last five decades, resulting in 235 million people suffering from it. One of the mai...

Development of a framework for increasing asthma awareness in Chitungwiza, Zimbabwe

Asthma accounts for significant global morbidity and health-care costs. It is still poorly understood among health professionals and the general population. Consequently, there are significant morbidity and mo...

Epidemiology and utilization of primary health care services in Qatar by asthmatic children 5–12 years old: secondary data analysis 2016–2017

Childhood asthma is a growing clinical problem and a burden on the health care system due to repetitive visits to children’s emergency departments and frequent hospital admissions where it is poorly controlled...

Is asthma in the elderly different? Functional and clinical characteristics of asthma in individuals aged 65 years and older

The prevalence of chronic diseases in the elderly (> 65 years), including asthma, is growing, yet information available on asthma in this population is scarce.

Factors associated with exacerbations among adults with asthma according to electronic health record data

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory lung disease that affects 18.7 million U.S. adults. Electronic health records (EHRs) are a unique source of information that can be leveraged to understand factors associated w...

What is safe enough - asthma in pregnancy - a review of current literature and recommendations

Although asthma is one of the most serious diseases causing complications during pregnancy, half of the women discontinue therapy thus diminishing the control of the disease, mostly due to the inadequate educa...

Biomarkers in asthma: state of the art

Asthma is a heterogenous disease characterized by multiple phenotypes driven by different mechanisms. The implementation of precision medicine in the management of asthma requires the identification of phenoty...

Exhaled biomarkers in childhood asthma: old and new approaches

Asthma is a chronic condition usually characterized by underlying inflammation. The study of asthmatic inflammation is of the utmost importance for both diagnostic and monitoring purposes. The gold standard fo...

Assessment of predictors for acute asthma attack in asthmatic patients visiting an Ethiopian hospital: are the potential factors still a threat?

Recurrent exacerbations in patients with moderate or severe asthma are the major causes of morbidity, mortality and medical expenditure. Identifying predictors of frequent asthma attack might offer the fertile...

Effect of adjusting the combination of budesonide/formoterol on the alleviation of asthma symptoms

The combination of budesonide + formoterol (BFC) offers the advantages of dose adjustment in a single inhaler according to asthma symptoms. We analyzed the relationship between asthma symptoms in terms of peak...

Asthma Research and Practice

ISSN: 2054-7064

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Advertisement

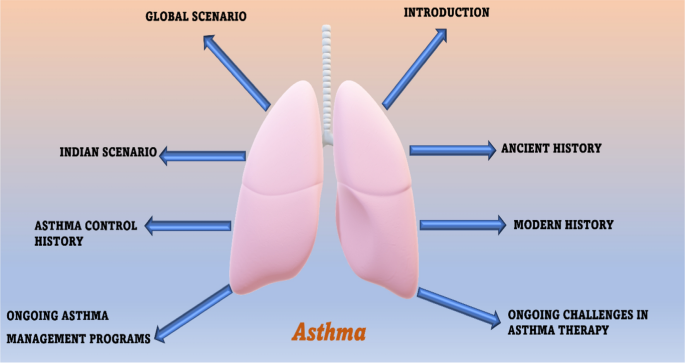

Asthma History, Current Situation, an Overview of Its Control History, Challenges, and Ongoing Management Programs: An Updated Review

- Published: 11 November 2022

- Volume 93 , pages 539–551, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Anandi Kapri ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8254-2676 1 ,

- Swati Pant ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9872-2463 1 ,

- Nitin Gupta ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8093-7295 2 ,

- Sarvesh Paliwal ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5247-2021 1 &

- Sumitra Nain ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8238-3145 1

4051 Accesses

2 Citations

4 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Asthma is a disease of the airways that is characterized by chronic inflammation and disordered airway function. The purpose of writing the current review paper is to review the history, current situation, control history, challenges, and ongoing management programs of asthma. Some official websites of known respiratory professional bodies were consulted for asthma guidelines, and information from Google Scholar® and PubMed® was also consulted. We reviewed around two hundred eight papers, and then, inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to prepare this manuscript. Out of these papers, thirty papers, factsheets, and some official websites were used to prepare this manuscript. Physicians should follow already existing asthma guidelines in order to manage asthma. All prescribed medications should be continued. The government should make and adopt more strategies to promote the rational use of anti-asthmatic drugs and healthcare facilities and also make plans to disseminate more awareness among people about the schemes and programs made for safeguarding people against this life-threatening disease. We have done so much advancement to fight against this deadly disease, and we still need time to make the globe asthma-free. The number of people suffering from asthma is more than the number of people suffering from HIV infection and tuberculosis. Understanding the recommendations of professional bodies will assist in medical decision-making in asthma management. The individual needs of patients should be considered by healthcare professionals.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Asthma epidemiology and risk factors

Jessica Stern, Jennifer Pier & Augusto A. Litonjua

Safety of Biological Therapies for Severe Asthma: An Analysis of Suspected Adverse Reactions Reported in the WHO Pharmacovigilance Database

Paola Maria Cutroneo, Elena Arzenton, … Gianluca Trifirò

The 2023 GOLD Report: Updated Guidelines for Inhaled Pharmacological Therapy in Patients with Stable COPD

Paul D. Terry & Rajiv Dhand

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

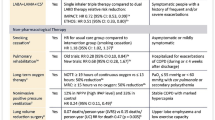

Asthma is one of the most ancient diseases of the airways, characterized by chronic inflammation and disordered airway function [ 1 ]. Despite numerous advancements in the treatment and diagnosis of asthma, unfortunately, a large population is still suffering, and worldwide it becomes one of the top infectious diseases. Approximately 10% of children and 5% of adults are suffering from this disease. A WHO key facts dated May 3, 2021, on asthma stated that approximately 262 million people are affected by this life-threatening disease in 2019 and the number will be expected to hike in the future. It is also characterized by some other symptoms like epithelial rupture, hypertrophy of airway smooth muscles, hypersecretion of mucous in lungs bronchial walls, wheezing, coughing, and dyspnea (Fig. 1 ). Although there is no proper treatment available for asthma, it can be controlled with proper management and help asthmatics to live in a better way [ 2 ]. The primary preventive measure taken by WHO (world health organization) for asthma and disease management is reducing tobacco smoke exposure, and the initiative MPOWER and Mtobacco cessation is enabling progress in this area of tobacco control.

Flowchart of asthma

The use of bronchodilators is the principal therapy used in asthma but a greater understanding of the chief role of inflammation in asthma has led to the conclusion of the use of anti-allergic or anti-inflammatory agents for the management of asthma and is an internationally recognized strategy for its cure. The ICS (Inhaled corticosteroids) can provide ideal disease control but not as monotherapy. They need additional therapies such as SABA (Short-acting β2 agonists), LABA (Long-acting β2 agonists), LTRA (Leukotriene receptor antagonist therapy), and theophylline to achieve adequate control [ 3 ]. The primary aim of writing this review paper is to provide a brief understanding of asthma by critically assessing articles related to asthma.

Material and Methods

We performed an electronic search to find out the existing literature on asthma. Initially, the search was conducted on search engines like Google Scholar® and PubMed® to gather updated information about asthma. In addition, the search was conducted on the official websites of professional organizations such as GINA (Global initiative for asthma), WHO, MOHFW (Government of India-ministry of health and family welfare), and CDC (Centers for disease control and prevention) to get relevant guidelines for asthma control, anti-asthmatic drugs, challenges, prevention, and control management programs. Approximately 10 months were completely used to compile data for this manuscript. The key terms used during the search were “Asthma,” “history of asthma” “current situation of asthma,” “asthma control history,” “challenges in asthma,” and “ongoing asthma management programs.” Two hundred eight papers were screened, and then, inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to prepare this manuscript. Out of these papers, thirty papers were used to prepare this manuscript. The last search was conducted on October 30, 2021.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Resources that were targeted at healthcare professionals and articles with a thorough understanding of asthma were included. All those papers which do not have original data and studies targeting the general public and patients were excluded.

Ancient History

For the very first-time, respiratory distress was recorded in China in 2600BC. The evidence was found in the form of “noisy breathing.” Shen nong in 2700BC was the first person to taste ephedra which was popularly known as anti-asthmatic herbal medicine around 5000 years ago [ 2 , 3 ]. The ancient Egyptians in 3000–1200BC believed respiration was one of the most crucial functions of the human body. Greco-roman (1000BC–200AD), both believe that asthma was produced due to demonic possession. Hippocrates was the first person who found that people suffering from asthma may have a hunch back. He also tried to understand the correlation between environment and respiratory problems. He also recommended ephedra along with red wine for the treatment of asthma [ 4 ].

Modern History

In the modern period, the understanding of the root cause of asthma began. In Europe 1500s, tobacco was introduced for the treatment of asthma, expectorate mucus and induce coughing. In 1579–1644, one of the chemists and physicians from Belgium Jean Baptiste Van Helmont said, “asthma was developed in the pipes of the lungs.” In (1633–1714), Bernardino Ramazzini found for the first-time exercise-induced asthma. He also acknowledged the correlation between organic dust and asthma. In the year 1873, Charles Blackley discovered the main cause of “hay asthma” and found that pollen was related to it. He rubbed pollen on different body parts to reproduce the symptoms [ 5 ]. In the 1900s, selective beta-2 adrenoceptors agonists were used for asthma treatment. In 1916, a physician and allergist named Francis Minot Rackemann reported that not all asthma is related to allergies. In 1920s, the deaths from asthma were related to airway structural changes and extensive inflammation but the information on why this happened and how it is responsible for bronchospasm was not known. For some decades, the treatment of asthma was done as episodic exacerbations [ 6 ]. Kustner and Prausnitz in the year 1921 noticed that asthmatics suffer from allergy symptoms due to indoor and outdoor irritants. In 1960s–1970s, technological advancements led to the use of peak flow meters to measure obstruction in airways and arterial blood gasses [ 7 ]. After the 1970s, inhaled corticosteroids were used for asthma cure. In 1980s, a depth understanding of how an allergen exposure, affect the release of a chemical mediator from mast cell which results in allergic asthmatic response [ 8 ].

Global Scenario

According to WHO information, asthma is included among (NCD) non-communicable diseases which is prevalent in children and adults. Generally, the deaths related to this disease mostly occur in countries with the economy in creeping and walking stage. The top fifteen countries with the largest asthmatic patients are Myanmar, Kiribati, Laos, Sri Lanka, New Guinea, Mali, Nepal, Fiji, Lesotho, Indonesia, Solomon Island, Sierra Leone, Timor-Leste, Philippines, and Vanuatu ( https://www.worldlifeexpectancy.com/cause-of-death/asthma/by-country/ ). In 2010, according to the data provided by National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, approximately 1.3 million patients hospital visits were due to asthma [ 9 ]. In 2011–2012, the national survey for children’s health reported that around 3.4% of children have used emergency hospital visits due to this life-threatening disease [ 5 , 8 ]. Around 10.1 million physician office visits were reported for the year 2015. In 2017, around 43.12 million asthma cases were recorded whereas 272.68 asthma prevalence (prevalence 3.57%) and 0.49 million deaths (mortality rate 0.006%). More than 1.6 million asthmatic patient emergency visits were reported for the year 2018. According to the 2019 data by WHO, this disease is considered one of the top ten deadliest diseases. It cannot be completely cured but proper management with inhaled medications can help to control the disease and thereby help people to lead normal life [ 10 ]. Around 262 million people were affected by this deadly disease in 2019 which caused 461,000 deaths. Globally, this disease is ranked 16th among the leading causes of years lived with a disability as well as 28th among the leading causes of burden of disease as calculated by DALY (disability-adjusted life years). It is estimated that around 300 million people were suffering from asthma worldwide and by 2025 around 100 million people were affected. There is a huge geographical variation in asthma severity, prevalence, and mortality. The prevalence is extremely high in high-income countries whereas the mortality rate is high in low-middle-income countries. As per the Lancet, the asthma statistics worldwide for 2020 reported that more than 339 million people were suffering from asthma and globally approx. four million children develop asthma each year. In North America, approx. 8% population has been diagnosed with asthma. The estimated prevalence of severe asthma is 5–10% of the global asthma population. It is more common in Puerto Rican Hispanic (13.3%) and Black (8.7%) than in white people (7.6%). The mortality rate is higher in black 25.4 than in whites 8.8 per million annually. The treatment options available for asthma are discussed as follows:

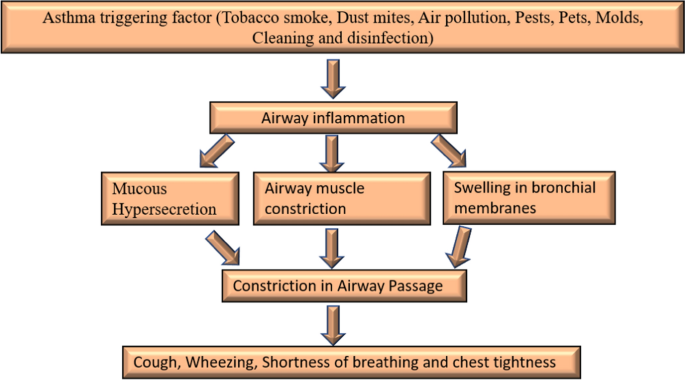

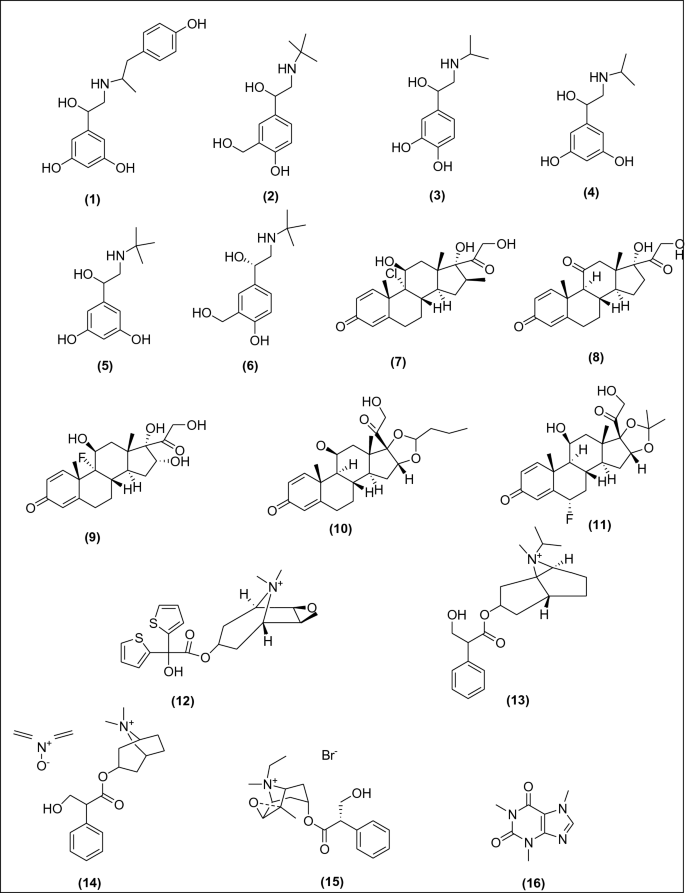

Bronchodilators or relievers act by quickly opening the airways and improving the rate of breathing. They also remove mucous from the lungs. As the airways get dilated, the mucous can be coughed with more ease. These act by targeting the β-2 adrenergic receptors in the airways. Activation of this receptor may relax the airway smooth muscles, thereby ensuring better airflow in the lungs [ 11 ]. Furthermore, they also help in inhibiting the parasympathetic nervous system receptors from functioning. As the parasympathetic nervous system increases the bronchial secretions and constriction in airways, inhibiting the nervous system should result in bronchodilation and lesser bronchial secretion [ 12 ] (Fig. 2 ). Bronchodilators are subdivided into the following parts (Fig. 3 ), Inhaled rapid-acting β-2 agonists: Fenoterol (1), Salbutamol (2), Isoproterenol (3), Metaproterenol (4), Terbutaline (5), Albuterol (6), Glucocorticoids (systemic): Beclomethasone (7), Prednisone (8), Triamcinolone (9), Budesonide (10), Flunisonide (11), Anticholinergics: Tiotropium bromide (12), Ipratropium bromide (13), Atropine methonitrate (14), Oxitropium bromide (15), Xanthine derivatives: Caffeine (16), Theobromine (17), Theophylline (18), Aminophylline (19), Hydroxyethyl theophylline (20), Choline theophyllinate (21), Doxophylline (22), Deriphylline (23), Diprophylline (24), Theophylline ethanolate of piperazine (25), Oral SABA: Salbutamol (2), Terbutaline (5), Bitolterol (26), Fenoterol (27), Rimiterol (28), Levalbuterol (29), and Pirbuterol (30).

Mechanism of action of bronchodilators in asthma

Anti-asthmatic drugs used as bronchodilators

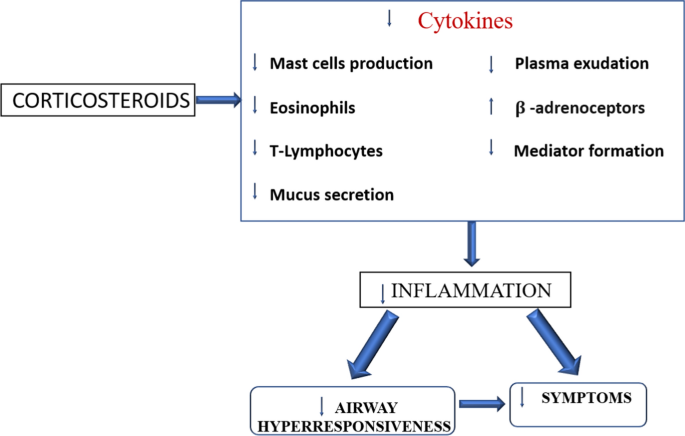

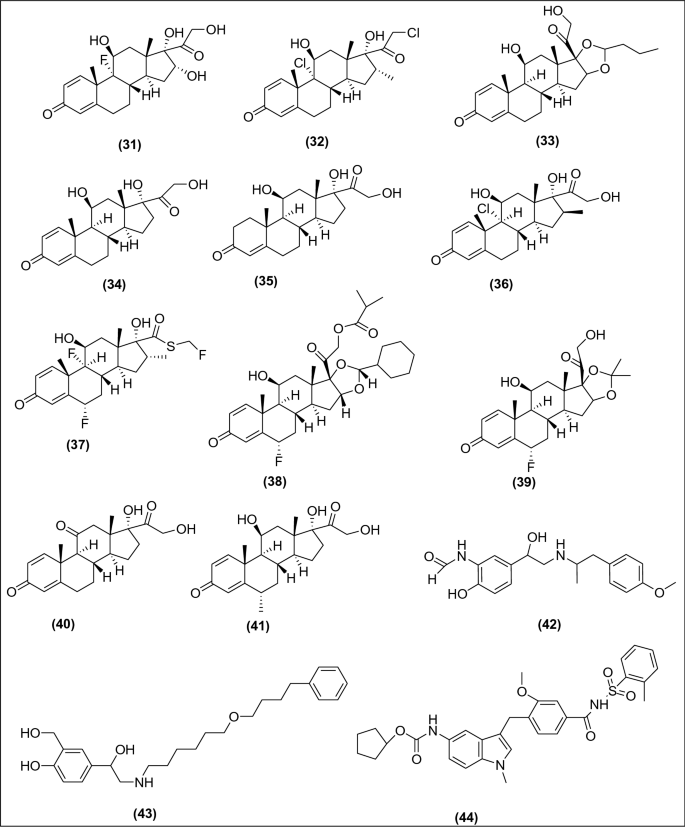

Anti-inflammatory agents reduce inflammation, swelling, and mucus production in the airways. The most important anti-inflammatory treatments are given by inhalation. Their mode of action is not completely understood, but they are likely to act in several different ways to produce an anti-inflammatory effect. The glucocorticoids act by inhibiting transcription factors that help in the regulation of pro-inflammatory mediators such as eosinophils, macrophages, dendritic cells, mast cells, and lymphocytes [ 13 ]. The steroids also act on mast cells and exert their anti-allergic action by inhibiting the signaling pathways in mast cells [ 14 ]. Furthermore, they also reduce plasma exudation in the airways and inhibit mucus glycoprotein secretion (Fig. 4 ). Anti-inflammatory agents are further classified into (Fig. 5 ), Inhaled or systemic corticosteroids: Triamcinolone (31), Mometasone (32), Budesonide (33), Prednisolone (34), Hydrocortisone (35), Beclomethasone (36), Fluticasone (37), Ciclesonide (38), Flunisolide (39), prednisone (40), Methylprednisolone (41), LABA: Formoterol (42), Salmeterol (43), Anti-IgE: Omalizumab, Leukotriene antagonist: Zafirlukast (44), Montelukast (45), Pranlukast (46), Iralukast (47), Oral anti-allergic compounds: Tranilast (48), Mast cell stabilizer: Sodium cromoglycate (49), Nedocromil Sodium (50), and Ketotifen (51).

Mechanism of action of corticosteroids on airway inflammation, symptoms and airway hyper-responsiveness

Anti-inflammatory drugs used for asthma

Indian Scenario

The Indians ayurveda believe that asthma results due to the imbalance between three doshas: (a) pitta (bile), (b) Kapha (phlegm), and (c) vata (wind). A person stays healthy if these three humors were balanced. The first book Ayurveda Materia medica from India ‘Charaka Samhita’ has a good clinical description of this life-threatening disease. A recent study on respiratory symptoms and chronic bronchitis performed on 85,105 men and 84,470 women from eleven rural and twelve urban areas in India estimated the prevalence rate of asthma is 2.05% among those aged above 15 years with an estimated national burden causing 18 million asthmatics [ 15 ]. Despite enormous advancements in the treatment and management of this disease, it becomes a major public health issue in India.

Asthma Control History

The early period of asthma control.

In 1500BC, the inhalation of the smoke of herbs is recommended for use as the treatment therapy for asthmatic patients in Egypt. In ancient China around 5000 years ago, the treatment was done by using ma-huang (Ephedra sinica), a type of Chinese herb which was later examined to have ephedrine (muscle relaxant), and these agents work as bronchodilators [ 6 , 13 ]. For a prolonged period, bronchodilators were used as the first-line drugs for the management of asthma which indicates contraction of airways as the chief pathology involved in the treatment. In 1900, the avoidance of allergens was used as the foremost therapy for asthma [ 5 ]. The use of a pressurized metered-dose inhaler in the mid-1950 has been developed for the administration of adrenaline and isoproterenol and was later used as a β2-adrenergic agonist. Later salbutamol and terbutaline were introduced as SABA. Recently, LABA is used as the principal drug incorporated into the inhaled corticosteroids in Japanese guidelines for asthma. Furthermore, LTRA and theophylline were used as the first-line drugs along with LABA and inhaled corticosteroids. The American thoracic society in the year 1962 describes asthma as a disease identified by the presence of airway hyper-responsiveness as well as reversible airway constriction [ 12 ]. Moreover, chronic airway inflammation was finally found as the clinical etiology involved in the pathogenesis of asthma and inhaled corticosteroids and the use of anti-inflammatory drugs became the first-line therapy for asthmatic patients [ 16 ]. In the early twentieth century, inhalation and intravenous administration of anticholinergic drugs were regarded as the principal therapy for asthma [ 2 ].

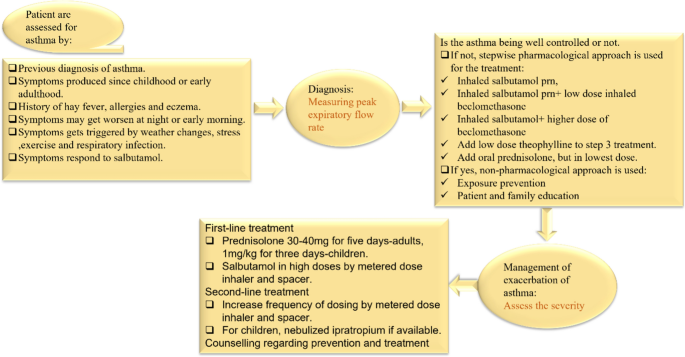

Current WHO-Aided Asthma Control Program

For the prevention and control of asthma, this disease has been incorporated in the WHO global action plan as well as the UN (United Nations) 2030 agenda for the sustainable development. WHO has taken several actions to extend the diagnosis and treatment of this disease. The PEN (package of essential non-communicable) disease intervention was developed by WHO to support people with non-communicable diseases with the help of UHC (universal health coverage) [ 17 ]. The PEN includes rules for assessment, diagnosis, and management of asthma and (COPD) chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and includes modules on healthy lifestyles (Fig. 6 ) [ 18 ]. The primary preventive measure taken for asthma and disease management is reducing tobacco smoke exposure, and the initiative MPOWER and Mtobacco cessation is enabling progress in this area of tobacco control. MPOWER is the WHO framework convention on tobacco control, and its guidelines were meant for countries working toward tobacco control. These guidelines were introduced in the year 2008 to manage tobacco control at the country level.

Assessment of asthma as per WHO PEN

WHO Global Action Plan 2013–2020

The goal of this action plan is to reduce the number of morbidities, mortality, and disability due to NCD by using multisectoral cooperation and collaboration at distinct levels (national, regional, and global), so that the population will remain at the highest standard of health and productivity at all ages as well as those diseases will no longer act as a barrier to well-being. As per the WHO, the total number of deaths due to NCD may increase to 55 million by 2030. The scientific knowledge demonstrates that the prevalence of non-communicable diseases is greatly decreased if cost-effective preventive and curative action, as well as interventions for prevention and control of NCD which are already available, are implemented in a balanced and effective manner [ 19 ].

GINA Global Strategy for Asthma 2021

On Nov 1, 2021, the GINA published an executive summary of an updated evidence-based summary for the treatment and prevention of asthma. On Oct 18, 2021, the summary was published online. The GINA science committee was developed in the year 2002 to review published research on asthma. This GINA report is updated every year and approx. 500,000 copies of GINA reports were downloaded each year by one hundred countries [ 20 ]. GINA report has been updated in the year 2020 with some modifications such as interim guidance about asthma and Covid-19, additional information for the new as well as existing therapies; additional documents have been added in supporting the use of ICS (Inhaled corticosteroid)—formoterol in mild asthma; assessment of symptom control and new data have been incorporated for the initial treatment of newly diagnosed asthma; information related to a maximum daily dose of ICS-Formoterol has been added; additional documents for the support of the use of ICS and addition of minimum and maximum doses of ICS have been incorporated in the treatment recommendation for asthma, and new additional information about the management of asthma in children has also been added [ 21 ].

India Asthma Report

As per demographics, around 6% of children and 2% of adults were suffering from this disease. A maximum number of people in India have no health insurance, and there is a big gap in healthcare facilities for the poor and the rich people. Most of the medications available in India (inhaled corticosteroids, combination inhalers, and β-2 agonists) are too expensive compared to oral formulations [ 22 ]. According to the data compiled from 1990 to 2005, the mortality rate in India decreased mainly in areas where healthcare facilities were better (urban areas and prosperous states). It was documented that Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh have the highest mortality rate. The Rajasthan government had provided free access to medicines to all the asthmatic patients of the state at government hospitals since 2011 and around 15,000 pharmacies had been opened by the state government across the state along with a free supply of metered-dose inhalers, nebulizer solutions, and dry powder inhaler capsules to asthmatic patients. In 2018, the Indian government planned to provide health insurance at no cost to 100 million low-income families, to cover their treatment costs [ 23 ].

Ongoing Challenges in Asthma Therapy

The problem of asthma is a global burden affecting more than 300 million people and causing around 2,50,000 deaths per year. Despite several effective treatments available, the control of this disease in the population remains inadequate. The advancement in treatments for children is lesser as compared to the adults due to the varying immunopathology, respiratory pathology, need for a child, parent education, and communication barrier. As most of the asthma research work was performed on adult asthma, thus this seems to be one of the principal barriers to managing the therapy childhood asthma [ 16 ]. The data on LABA use for the treatment of asthma in adults are widely available while the data available for LABA use in children are limited. Since then, several studies have been conducted to complete the gap for LABA use in children and adolescents resulting in several regulatory approvals for LABA inhalers, and inhaled corticosteroids such as fluticasone + salmeterol, budesonide + formoterol have been approved as maintenance treatment for children and adolescents in the USA and Europe [ 24 , 25 ]. Asthma management in children is a complex process due to variability in asthma severity, control, and difficulty in measuring lung function as well as airway inflammation. The primary challenge in the management of pediatric asthma is treating the symptoms of asthma rather than treating the root cause, i.e., inflammation, and switching to controller therapy when the problem worsens. The prevalence of childhood asthma increased in the 1980s–1990s, and the rate kept on increasing over the past decade; it seems to be one of the greatest global economic burdens in terms of direct and indirect costs.

Furthermore, the healthcare providers, as well as patients, are dealing with several types of challenges such as challenges in diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up challenges. As poor healthcare facilities are provided in rural areas, poverty, lack of awareness, and the high price of anti-asthmatic drugs are some of the routinely faced challenges of patients [ 26 ]. The diagnosis of asthma seems to be challenging work, both in terms of underdiagnosis and overdiagnosis. The underdiagnosis of asthma is familiar and was documented in epidemiological as well as clinical studies while the data on overdiagnosis are new [ 27 ]. Physicians are entirely dependent on asthma guidelines for the diagnosis and management of this disease. The NIH (National Institute of health) released latest updates to the national guidelines meant for the diagnosis, management, and treatment of asthma. The guidelines were made to upgrade patient care and to support decision-making about asthma management in a clinical setting.

In India, the national rural health mission (NRHM) was implemented to improve primary healthcare facilities in rural areas, to improve the health status and quality of life of people living in rural areas, and to prevent and control communicable and non-communicable diseases. The diagnosis of asthma is a difficult process because for some reasons: (a) The signs and symptoms might not show during routine analysis, (b) unavailability of the standard diagnostic test—in clinical practice, spirometry and peak expiratory flow assessment are done to check the signs and symptoms, and (c) The guideline recommendation is not always compatible with the working systems in primary care. Some of the other treatment options which might help in improving asthma management and control are switching from relievers SABA to LABA along with a combination of inhaled corticosteroids as per the recommendation of GINA to make sure that the person with asthma receives an inhaled corticosteroid to get symptomatic relief whenever possible.

Ongoing Asthma Management Programs

The problem of asthma is prevalent among children and elderly people. In UK 1 in 14 adults are affected by this alarming condition. The national public health agency of the USA, i.e., CDC has made a self-management education (SME) program “Breathe well, live well” that helps those people with prevailing health conditions to feel better. The SME program helps people to strategize and develop the skills and confidence to tackle ongoing health conditions efficiently and help in dealing with the following conditions: cope with symptoms, communicate with doctors, manage fatigue, handle stress, manage medication, eat healthy, reduce depression, and be active. These strategies can help the patients to make good decisions about health and makes them feel better [ 28 ].

The 2020 focused updates to the asthma management guidelines were published for the diagnosis and management of asthma. These guidelines help the clinician integrate the new recommendation into clinical care. These are meant for individual patient management [ 29 ]. The Alameda County public health department (ACPHD) enabled community health services asthma start programs that help families of children with asthma by providing in-home case management studies. They provide education, support, and assistance in developing an action plan to address the needs of families where the child has asthma thereby helping in regulating it. The services provided by them is as follows: (a) education to families about the disease, several types of triggers, prevention of attacks, treatments, etc., (b) collaborating with daycare providers and schools to make sure asthma medication is accessible to every child, and moreover, supplying asthma-related education to all the school staff as well as daycare providers, (c) assistance with health insurance, housing, and employment, and (d) remote home inspections to find the triggers and causes of asthma [ 30 ].

Results and Discussion

Generally, the recommendations from different professional bodies suggest that physicians should follow the already existing guidelines for the proper management of this disease. The key points are as follows: bronchodilators were considered a principal therapy for the treatment of asthma in early times, but after the advent of inhaled corticosteroids, the therapeutic history gets drastically changed. The use of bronchodilators is the principal therapy used in asthma but a greater understanding of the chief role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of asthma has led to the conclusion of the use of anti-allergic or anti-inflammatory agents for the management of asthma. The ICS can provide ideal disease control but not as monotherapy. They need additional therapies such as SABA, LABA, LTRA, and theophylline to achieve adequate control.

It is very much clear from the above discussion that we have done so much advancement to fight against this deadly disease and we still need time to make the globe asthma-free. The number of people suffering from asthma is more than the number of people suffering from HIV infection and tuberculosis.

Understanding the recommendations of professional bodies will assist in medical decision-making in asthma management. Healthcare professionals should consider the individual needs of patients. In conclusion, the main problem in the management of this disease is improper use of healthcare facilities, lack of knowledge about anti-asthmatic drugs, poverty, and the cost of drugs. The government should make and adopt more strategies to promote the rational use of anti-asthmatic drugs and make plans to spread more awareness among people about the schemes and programs made for safeguarding people against this life-threatening disease.

Löwhagen O (2015) Diagnosis of asthma–new theories. J Asthma 67(6):713–717. https://doi.org/10.3109/02770903.2014.991971

Article CAS Google Scholar

Stein SW, Thiel CG (2017) The history of therapeutic aerosols: a chronological review. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv 30(1):20–41. https://doi.org/10.1089/jamp.2016.1297

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bergmann KC (2014) Asthma. Chem Immunol Allergy 100:69–80. https://doi.org/10.1159/000358575

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Rothe TA (2018) Century of “intrinsic asthma.” Allergo J 27:19–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s15007-018-1719-3

Article Google Scholar

Sanders MJ (2017) Guiding inspiratory flow: development of the in-check DIAL G16, a tool for improving inhaler technique. Pulm Med. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/1495867

Beasley R, Harper J, Bird G et al (2019) Inhaled corticosteroid therapy in adult asthma: time for a new therapeutic dose terminology. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 199(12):1471–1477. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201810-1868ci

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Silverman RA, Hasegawa K, Egan DJ et al (2017) Multicenter study of cigarette smoking among adults with asthma exacerbations in the emergency department, 2011–2012. Respir Med 125:89–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2017.02.004

Quirt J, Hildebrand KJ, Mazza J et al (2018) Asthma. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 14:15–30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13223-018-0279-0

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2018) Usual place for medical care among children, pp 13–17. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/EarlyRelease201803_02.pdf . Accessed 8 April 2021

GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators (2020) Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 396(10258):1204–1222. Erratum in: Lancet. 2020; 396(10262):1562. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30925-9

Matera MG, Page CP, Calzetta L et al (2020) Pharmacology and therapeutics of bronchodilators revisited. Pharmacol Rev 72(1):218–252. https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.119.018150

Harma S, Hashmi MF, Chakraborty RK (2021) Asthma medications. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island

Google Scholar

Williams DM (2018) Clinical pharmacology of corticosteroids. Respir Care 63(6):655–670. https://doi.org/10.4187/respcare.06314

Oppong E, Flink N, Cato ACB (2013) Molecular mechanisms of glucocorticoid action in mast cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol 380(1–2):119–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2013.05.014

Joshi KS, Nesari TM, Dedge AP et al (2016) Dosha phenotype specific Ayurveda intervention improves asthma symptoms through cytokine modulations: results of whole system clinical trial. J Ethnopharmacol 197:110–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2016.07.071

Barcik W, Boutin RCT, Sokolowska M, Finlay BB (2020) The role of lung and gut microbiota in the pathology of asthma. Immunity 52(2):241–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2020.01.007

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

World Health Organization (2021) factsheet: Asthma. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/asthma . Accessed 17 April 2021

World Health Organization (2020) package of essential non communicable (PEN) disease interventions for primary healthcare. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-package-of-essential-noncommunicable-(pen)-disease-interventions-for-primary-health-care . Accessed 24 April 2021

World Health Organization (2013) Global action plan for the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases 2013–2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/94384/9789241506236_eng.pdf?sequence=1 . Accessed 2 May 2021

Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) (2021) Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/GINA-2021_Methodology_20210523.pdf . Accessed 12 May 2021

Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) (2020) Pocket guide for asthma management and prevention for adults and children (updated 2020). https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Main-pocket-guide_2020_04_03-final-wms.pdf . Accessed 17 June 2021

The Global Asthma Report (2018) http://globalasthmareport.org/management/india.php . Accessed 22 June 2021

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019) Most recent national asthma data. https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/most_recent_national_asthma_data.htm . Accessed 8 Aug 2021

Szefler SJ, Chipps B (2018) Challenges in the treatment of asthma in children and adolescents. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 120(4):382–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2018.01.003

Pearlman DS, Eckerwall G, McLaren J et al (2017) Efficacy and safety of budesonide/formoterol pMDI vs budesonide pMDI in asthmatic children (6–<12years). Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 118:489–499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2017.01.020

Bakirtas A (2017) Diagnostic challenges of childhood asthma. Curr Opin Pulm Med 23(1):27–33. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCP.0000000000000338

Aaron SD, Boulet LP, Reddel HK, Gershon A (2018) Under-diagnosis and over-diagnosis of asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 198(8):1–25. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201804-0682ci

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Managing asthma. https://www.cdc.gov/learnmorefeelbetter/programs/asthma.htm . Accessed 15 Aug 2021

2020 Focused updates to the asthma management guidelines (2020) Briefly guide. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/sites/default/files/publications/AsthmaClinicians-At-a-Glance-508.pdf . Accessed 10 Sept 2021

Alameda County Public Health Department. Asthma Start program. https://acphd.org/asthma/ . Accessed 30 Oct 2021

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the Honorable Vice-Chancellor, Banasthali Vidyapith, Banasthali, Rajasthan, for providing essential facilities.

There was no funding provided for the preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Pharmacy, Banasthali Vidyapith, Banasthali, Rajasthan, 304022, India

Anandi Kapri, Swati Pant, Sarvesh Paliwal & Sumitra Nain

Agilent Technologies Pvt. Ltd., 181/46, Industrial Area, Phase-1, Chandigarh, 160002, India

Nitin Gupta

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Nitin Gupta contributed to Conception and design of study, Swati Pant contributed to literature collection and Anandi Kapri contributed to Drafting the manuscript and Sumitra Nain & Sarvesh Paliwal contributed to Overall supervision.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sumitra Nain .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Significance Statement: This review paper aims to spread awareness among the general public about the scenario of Asthma. The physicians should prescribe bronchodilators and anti-inflammatory agents to manage asthma symptoms.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Kapri, A., Pant, S., Gupta, N. et al. Asthma History, Current Situation, an Overview of Its Control History, Challenges, and Ongoing Management Programs: An Updated Review. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., India, Sect. B Biol. Sci. 93 , 539–551 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40011-022-01428-1

Download citation

Received : 23 January 2022

Revised : 03 August 2022

Accepted : 31 August 2022

Published : 11 November 2022

Issue Date : September 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40011-022-01428-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Respiratory

- Healthcare professionals

- Anti-asthmatic drugs

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Open access

- Published: 15 August 2020

Treatment strategies for asthma: reshaping the concept of asthma management

- Alberto Papi 1 , 7 ,

- Francesco Blasi 2 , 3 ,

- Giorgio Walter Canonica 4 ,

- Luca Morandi 1 , 7 ,

- Luca Richeldi 5 &

- Andrea Rossi 6

Allergy, Asthma & Clinical Immunology volume 16 , Article number: 75 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

44k Accesses

51 Citations

4 Altmetric

Metrics details

Asthma is a common chronic disease characterized by episodic or persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitation. Asthma treatment is based on a stepwise and control-based approach that involves an iterative cycle of assessment, adjustment of the treatment and review of the response aimed to minimize symptom burden and risk of exacerbations. Anti-inflammatory treatment is the mainstay of asthma management. In this review we will discuss the rationale and barriers to the treatment of asthma that may result in poor outcomes. The benefits of currently available treatments and the possible strategies to overcome the barriers that limit the achievement of asthma control in real-life conditions and how these led to the GINA 2019 guidelines for asthma treatment and prevention will also be discussed.

Asthma, a major global health problem affecting as many as 235 million people worldwide [ 1 ], is a common, non-communicable, and variable chronic disease that can result in episodic or persistent respiratory symptoms (e.g. shortness of breath, wheezing, chest tightness, cough) and airflow limitation, the latter being due to bronchoconstriction, airway wall thickening, and increased mucus.

The pathophysiology of the disease is complex and heterogeneous, involving various host-environment interactions occurring at various scales, from genes to organ [ 2 ].

Asthma is a chronic disease requiring ongoing and comprehensive treatment aimed to reduce the symptom burden (i.e. good symptom control while maintaining normal activity levels), and minimize the risk of adverse events such as exacerbations, fixed airflow limitation and treatment side effects [ 3 , 4 ].

Asthma treatment is based on a stepwise approach. The management of the patient is control-based; that is, it involves an iterative cycle of assessment (e.g. symptoms, risk factors, etc.), adjustment of treatment (i.e. pharmacological, non-pharmacological and treatment of modifiable risk factors) and review of the response (e.g. symptoms, side effects, exacerbations, etc.). Patients’ preferences should be taken into account and effective asthma management should be the result of a partnership between the health care provider and the person with asthma, particularly when considering that patients and clinicians might aim for different goals [ 4 ].

This review will discuss the rationale and barriers to the treatment of asthma, that may result in poor patient outcomes. The benefits of currently available treatments and the possible strategies to overcome the barriers that limit the achievement of asthma control in real-life situations will also be discussed.

The treatment of asthma: where are we? Evolution of a concept

Asthma control medications reduce airway inflammation and help to prevent asthma symptoms; among these, inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are the mainstay in the treatment of asthma, whereas quick-relief (reliever) or rescue medicines quickly ease symptoms that may arise acutely. Among these, short-acting beta-agonists (SABAs) rapidly reduce airway bronchoconstriction (causing relaxation of airway smooth muscles).

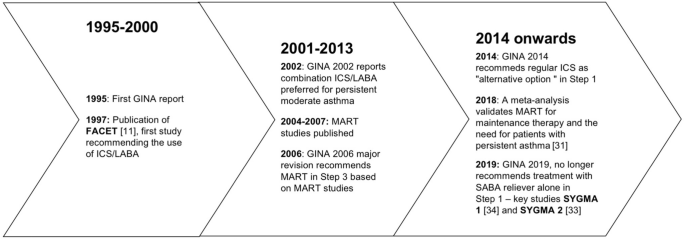

National and international guidelines have recommended SABAs as first-line treatment for patients with mild asthma, since the Global Initiative for Asthma guidelines (GINA) were first published in 1995, adopting an approach aimed to control the symptoms rather than the underlying condition; a SABA has been the recommended rescue medication for rapid symptom relief. This approach stems from the dated idea that asthma symptoms are related to bronchial smooth muscle contraction (bronchoconstriction) rather than a condition concomitantly caused by airway inflammation. In 2019, the GINA guidelines review (GINA 2019) [ 4 ] introduced substantial changes overcoming some of the limitations and “weaknesses” of the previously proposed stepwise approach to adjusting asthma treatment for individual patients. The concept of an anti-inflammatory reliever has been adopted at all degrees of severity as a crucial component in the management of the disease, increasing the efficacy of the treatment while lowering SABA risks associated with patients’ tendency to rely or over-rely on the as-needed medication.

Until 2017, the GINA strategy proposed a pharmacological approach based on a controller treatment (an anti-inflammatory, the pillar of asthma treatment), with a SABA as an additional rescue intervention. The reliever, a short-acting bronc hodilator, was merely an addendum , a medication to be used in case the real treatment (the controller) failed to maintain disease control: SABAs effectively induce rapid symptom relief but are ineffective on the underlying inflammatory process. Based on the requirement to achieve control, the intensity of the controller treatment was related to the severity of the disease, varying from low-dose ICS to combination low-dose ICS/long-acting beta-agonist (LABA), medium-dose ICS/LABA, up to high-dose ICS/LABA, as preferred controller choice, with a SABA as the rescue medication. As a result, milder patients were left without any anti-inflammatory treatment and could only rely on SABA rescue treatment.

Poor adherence to therapy is a major limitation of a treatment strategy based on the early introduction of the regular use of controller therapy [ 5 ]. Indeed, a number of surveys have highlighted a common pattern in the use of inhaled medication [ 6 ], in which treatment is administered only when asthma symptoms occur; in the absence of symptoms, treatment is avoided as patients perceive it as unnecessary. When symptoms worsen, patients prefer to use reliever therapies, which may result in the overuse of SABAs [ 7 ]. Indirect evidence suggests that the overuse of beta-agonists alone is associated with increased risk of death from asthma [ 8 ].

In patients with mild persistent disease, low-dose ICS decreases the risk of severe exacerbations leading to hospitalization and improves asthma control [ 9 ]. When low-dose ICS are ineffective in controlling the disease (Step 3 of the stepwise approach), a combination of low-dose ICS with LABA maintenance was the recommended first-choice treatment, plus as-needed SABA [ 3 , 10 ]. Alternatively, the combination low-dose ICS/LABA (formoterol) was to be used as single maintenance and reliever treatment (SMART). The SMART strategy containing the rapid-acting formoterol was recommended throughout GINA Steps 3 to 5 based on solid clinical-data evidence [ 3 ].

The addition of a LABA to ICS treatment reduces both severe and mild asthma exacerbation rates, as shown in the one-year, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group FACET study [ 11 ]. This study focused on patients with persistent asthma symptoms despite receiving ICS and investigated the efficacy of the addition of formoterol to two dose levels of budesonide (100 and 400 µg bid ) in decreasing the incidence of both severe and mild asthma exacerbations. Adding formoterol decreased the incidence of both severe and mild asthma exacerbations, independent of ICS dose. Severe and mild exacerbation rates were reduced by 26% and 40%, respectively, with the addition of formoterol to the lower dose of budesonide; the corresponding reductions were 63% and 62%, respectively, when formoterol was added to budesonide at the higher dose.

The efficacy of the ICS/LABA combination was confirmed in the post hoc analysis of the FACET study, in which patients were exposed to a combination of formoterol and low-dose budesonide [ 12 ]. However, such high levels of asthma control are not achieved in real life [ 5 ]. An explanation for this is that asthma is a variable condition and this variability might include the exposure of patients to factors which may cause a transient steroid insensitivity in the inflammatory process. This, in turn, may lead to an uncontrolled inflammatory response and to exacerbations, despite optimal controller treatment. A typical example of this mechanism is given by viral infections, the most frequent triggers of asthma exacerbations. Rhinoviruses, the most common viruses found in patients with asthma exacerbations, interfere with the mechanism of action of corticosteroids making the anti-inflammatory treatment transiently ineffective. A transient increase in the anti-inflammatory dose would overcome the trigger-induced anti-inflammatory resistance, avoiding uncontrolled inflammation leading to an exacerbation episode [ 13 , 14 , 15 ].

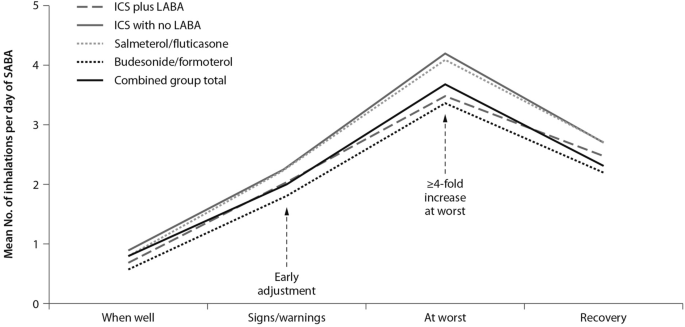

Indeed, symptoms are associated with worsening inflammation and not only with bronchoconstriction. Romagnoli et al. showed that inflammation, as evidenced by sputum eosinophilia and eosinophilic markers, is associated with symptomatic asthma [ 16 ]. A transient escalation of the ICS dose would prevent loss of control over inflammation and decrease the risk of progression toward an acute episode. In real life, when experiencing a deterioration of asthma control, patients self-treat by substantially increasing their SABA medication (Fig. 1 ); it is only subsequently that they (modestly) increase the maintenance treatment [ 17 ].

Mean use of SABA at different stages of asthma worsening. Patients have been grouped according to maintenance therapy shown in the legend. From [ 17 ], modified

As bronchodilators, SABAs do not control the underlying inflammation associated with increased symptoms. The “as required” use of SABAs is not the most effective therapeutic option in controlling a worsening of inflammation, as signaled by the occurrence of symptoms; instead, an anti-inflammatory therapy included in the rescue medication along with a rapid-acting bronchodilator could provide both rapid symptom relief and control over the underlying inflammation. Thus, there is a need for a paradigm shift, a new therapeutic approach based on the rescue use of an inhaled rapid-acting beta-agonist combined with an ICS: an anti-inflammatory reliever strategy [ 18 ].

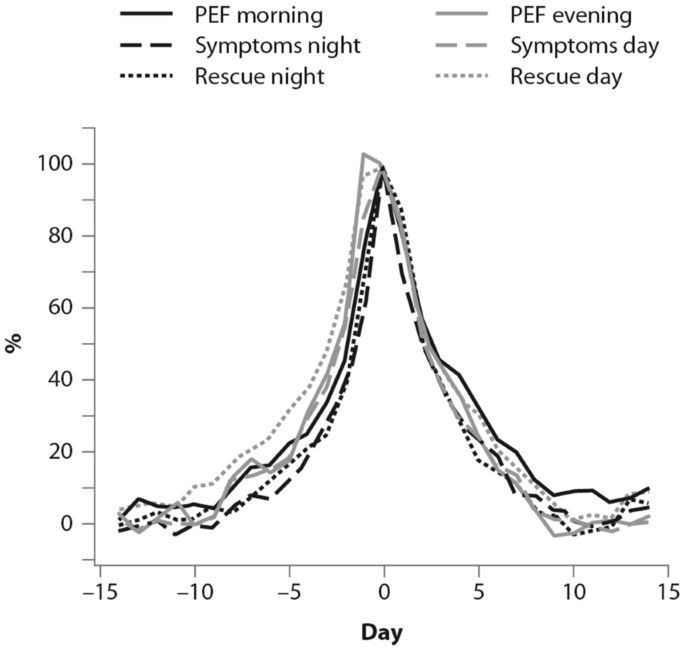

The symptoms of an exacerbation episode, as reported by Tattersfield and colleagues in their extension of the FACET study, increase gradually before the peak of the exacerbation (Fig. 2 ); and the best marker of worsening asthma is the increased use of rescue beta-agonist treatment that follows exactly the pattern of worsening symptomatology [ 19 ]. When an ICS is administered with the rescue bronchodilator, the patient would receive anti-inflammatory therapy when it is required; that is, when the inflammation is uncontrolled, thus increasing the efficiency of the anti-inflammatory treatment.

(From [ 19 ])

Percent variation in symptoms, rescue beta-agonist use and peak expiratory flow (PEF) during an exacerbation. In order to allow comparison over time, data have been standardized (Day-14 = 0%; maximum change = 100%)

Barriers and paradoxes of asthma management

A number of barriers and controversies in the pharmacological treatment of asthma have prevented the achievement of effective disease management [ 20 ]. O’Byrne and colleagues described several such controversies in a commentary published in 2017, including: (1) the recommendation in Step 1 of earlier guidelines for SABA bronchodilator use alone, despite asthma being a chronic inflammatory condition; and (2) the autonomy given to patients over perception of need and disease control at Step 1, as opposed to the recommendation of a fixed-dose approach with treatment-step increase, regardless of the level of symptoms [ 20 ]. Other controversies outlined were: (3) a difficulty for patients in understanding the recommendation to minimize SABA use at Step 2 and switch to a fixed-dose ICS regimen, when they perceive SABA use as more effective; (4) apparent conflicting safety messages within the guidelines that patient-administered SABA monotherapy is safe, but patient-administered LABA monotherapy is not; and (5) a discrepancy as to patients’ understanding of “controlled asthma” and their symptom frequency, impact and severity [ 20 ].

Controversies (1) and (2) can both establish an early over-dependence on SABAs. Indeed, asthma patients freely use (and possibly overuse) SABAs as rescue medication. UK registry data have recently suggested SABA overuse or overreliance may be linked to asthma-related deaths: among 165 patients on short-acting relievers at the time of death, 56%, 39%, and 4% had been prescribed > 6, > 12, and > 50 SABA inhalers respectively in the previous year [ 21 ]. Registry studies have shown the number of SABA canisters used per year to be directly related to the risk of death in patients with asthma. Conversely, the number of ICS canisters used per year is inversely related to the rate of death from asthma, when compared with non-users of ICS [ 8 , 22 ]. Furthermore, low-dose ICS used regularly are associated with a decreased risk of asthma death, with discontinuation of these agents possibly detrimental [ 22 ].

Other barriers to asthma pharmacotherapy have included the suggestion that prolonged treatment with LABAs may mask airway inflammation or promote tolerance to their effects. Investigating this, Pauwels and colleagues found that in patients with asthma symptoms that were persistent despite taking inhaled glucocorticoids, the addition of regular treatment with formoterol to budesonide for a 12-month period did not decrease asthma control, and improved asthma symptoms and lung function [ 11 ].

Treatment strategies across all levels of asthma severity

Focusing on risk reduction, the 2014 update of the GINA guidelines recommended as-needed SABA for Step 1 of the stepwise treatment approach, with low-dose ICS maintenance therapy as an alternative approach for long-term anti-inflammatory treatment [ 23 ]. Such a strategy was only supported by the evidence from a post hoc efficacy analysis of the START study in patients with recently diagnosed mild asthma [ 24 ]. The authors showed that low-dose budesonide reduced the decline of lung-function over 3 years and consistently reduced severe exacerbations, regardless of symptom frequency at baseline, even in subjects with symptoms below the then-threshold of eligibility for ICS [ 24 ]. However, as for all post hoc analyses, the study by Reddel and colleagues does not provide conclusive evidence and, even so, their results could have questionable clinical significance for the management of patients with early mild asthma. To be effective, this approach would require patients to be compliant to regular twice-daily ICS for 10 years to have the number of exacerbations reduce by one. In real life, it is highly unlikely that patients with mild asthma would adhere to such a regular regimen [ 25 ].

The 2016 update to the GINA guidelines lowered the threshold for the use of low-dose ICS (GINA Step 2) to two episodes of asthma symptoms per month (in the absence of any supportive evidence for the previous cut-off). The objective was to effectively increase the asthma population eligible to receive regular ICS treatment and reduce the population treated with a SABA only, given the lack of robust evidence of the latter’s efficacy and safety and the fact that asthma is a variable condition characterized by acute exacerbations [ 26 ]. Similarly, UK authorities recommended low-dose ICS treatment in mild asthma, even for patients with suspected asthma, rather than treatment with a SABA alone [ 10 ]. However, these patients are unlikely to have good adherence to the regular use of an ICS. It is well known that poor adherence to treatment is a major problem in asthma management, even for patients with severe asthma. In their prospective study of 2004, Krishnan and colleagues evaluated the adherence to ICS and oral corticosteroids (OCS) in a cohort of patients hospitalized for asthma exacerbations [ 27 ]. The trend in the data showed that adherence to ICS and OCS treatment in patients dropped rapidly to reach nearly 50% within 7 days of hospital discharge, with the rate of OCS discontinuation per day nearly double the rate of ICS discontinuation per day (− 5.2% vs. − 2.7%; p < 0.0001 respectively, Fig. 3 ), thus showing that even after a severe event, patients’ adherence to treatment is suboptimal [ 27 ].

(From [ 27 ])

Use of inhaled (ICS) and oral (OCS) corticosteroids in patients after hospital discharge among high-risk adult patients with asthma. The corticosteroid use was monitored electronically. Error bars represent the standard errors of the measured ICS and OCS use

Guidelines set criteria with the aim of achieving optimal control of asthma; however, the attitude of patients towards asthma management is suboptimal. Partridge and colleagues were the first in 2006 to evaluate the level of asthma control and the attitude of patients towards asthma management. Patients self-managed their condition using their medication as and when they felt the need, and adjusted their treatment by increasing their intake of SABA, aiming for an immediate relief from symptoms [ 17 ]. The authors concluded that the adoption of a patient-centered approach in asthma management could be advantageous to improve asthma control.

The concomitant administration of an as-needed bronchodilator and ICS would provide rapid relief while administering anti-inflammatory therapy. This concept is not new: in the maintenance and reliever approach, patients are treated with ICS/formoterol (fast-acting, long-acting bronchodilator) combinations for both maintenance and reliever therapy. An effective example of this therapeutic approach is provided in the SMILE study in which symptomatic patients with moderate to severe asthma and treated with budesonide/formoterol as maintenance therapy were exposed to three different as-needed options: SABA (terbutaline), rapid-onset LABA (formoterol) and a combination of LABA and ICS (budesonide/formoterol) [ 28 ]. When compared with formoterol, budesonide/formoterol as reliever therapy significantly reduced the risk of severe exacerbations, indicating the efficacy of ICS as rescue medication and the importance of the as-needed use of the anti-inflammatory reliever.

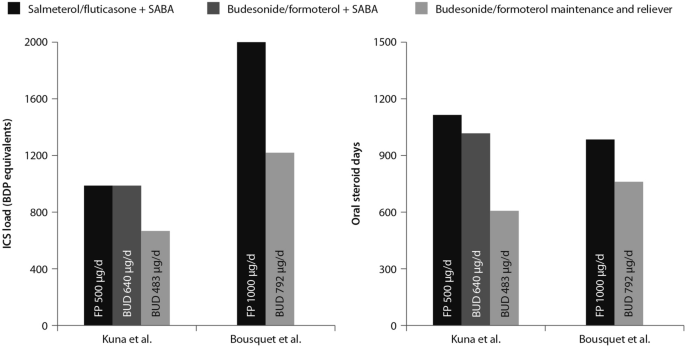

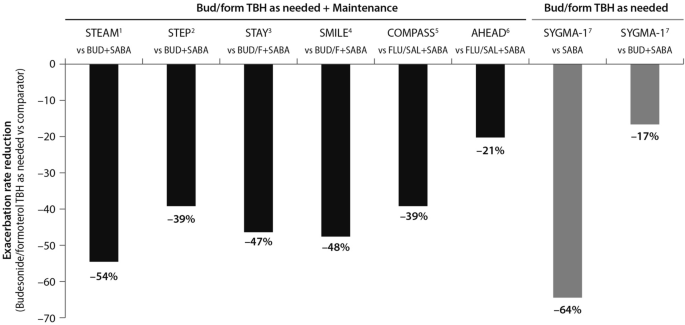

The combination of an ICS and a LABA (budesonide/formoterol) in one inhaler for both maintenance and reliever therapy is even more effective than higher doses of maintenance ICS and LABA, as evidenced by Kuna and colleagues and Bousquet and colleagues (Fig. 4 ) [ 29 , 30 ].

(Data from [ 29 , 30 ])

Comparison between the improvements in daily asthma control resulting from the use of budesonide/formoterol maintenance and reliever therapy vs. higher dose of ICS/LABA + SABAZ and steroid load for the two regimens

The effects of single maintenance and reliever therapy versus ICS with or without LABA (controller therapy) and SABA (reliever therapy) have been recently addressed in the meta-analysis by Sobieraj and colleagues, who analysed 16 randomized clinical trials involving patients with persistent asthma [ 31 ]. The systematic review supported the use of single maintenance and reliever therapy, which reduces the risk of exacerbations requiring systemic corticosteroids and/or hospitalization when compared with various strategies using SABA as rescue medication [ 31 ].

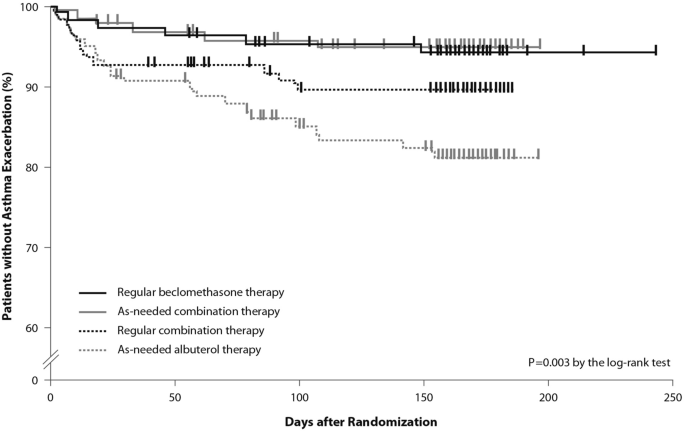

This concept was applied to mild asthma by the BEST study group, who were the first to challenge the regular use of ICS. A pilot study by Papi and colleagues evaluated the efficacy of the symptom-driven use of beclomethasone dipropionate plus albuterol in a single inhaler versus maintenance with inhaled beclomethasone and as-needed albuterol. In this six-month, double-blind, double-dummy, randomized, parallel-group trial, 455 patients with mild asthma were randomized to one of four treatment groups: an as-needed combination therapy of placebo bid plus 250 μg of beclomethasone and 100 μg of albuterol in a single inhaler; an as-needed albuterol combination therapy consisting of placebo bid plus 100 μg of albuterol; regular beclomethasone therapy, comprising beclomethasone 250 μg bid and 100 μg albuterol as needed); and regular combination therapy with beclomethasone 250 μg and albuterol 100 μg in a single inhaler bid plus albuterol 100 μg as needed.