Crime and Deviance Essay

Introduction, sociological perspective.

Deviance is an act perceived to be against one cultural belief and the act cannot be tolerated. Deviance acts are different from one community to another and also can vary depending on generational time.

For example, the homosexuality is allowed in American society, but in Africa the act is seen as satanic and can make the victims to be stoned to death. In some decades ago, divorce was seen to be against the rule of the church society, but with modernization, divorced has grown to be accepted as part of marriage life (Lukes 28).

Crime is an act that is against the norm of a society and the registered law of the entire country. If a person breaks a certain section of a country law, there is a correction sanction to that person. A person is usually taken to the court of law where the offence is listened to, by the judge and the person is either proven guilty or innocent.

A criminal can be put in jail for some time or for life, sentenced to death and even pay some money as a penalty (Lukes 28). A country law which is constitution is mostly formed by the parliament of that country.

Introduction . Sociologists have tried to understand crime and deviance in different ways. Most of the ancient sociologists have come up with different sociological perspectives that try to explain crime and deviance.

Emile Durkheim came up with rule of sociological methods that explained crime as part of society norms. Durkheim believed crime to be higher in modernized and industrialized society as compared to less modernized. In industrialized society, division of labor is the norm of life and each person is exposed to different work experiences (Moyer 54).

Division of labor exists in two ways, one is mechanical solidarity whereby the members of the society are similar and the organic solidarity in which society members creates a relationship among themselves through the division of labor. As in the division of labor, society people have different influences and situational experiences that distinguish one person from the other.

The personal differences make some people to be criminals and other to be good. No society lacks deviance or crime however perfect it could be. Every community has norms and traditions that put the members together and if the norms are broken, there is state of anomie and lawlessness.

Advantages of the perspective . Durkheim argued that besides division of labor helping to make production rise and improve the human capital it also possessed a moral character that created a sense of solidarity in humans. He explained with a married couple arguing that sexual desire would only exist after the material life has disappeared if the division of labor was to be reduced between the marriage partners.

Durkheim suggested that division of labor has more of social and moral order therefore married couple is bided by their common things they do. Durkheim saw that crime was beneficial to the society in some instances. Crime builds future morality by showing what law is to be followed.

For example a committed crime will lead to establishment of an order that will be followed by the people to avoid repetition of the same crime. Crime corrections or rewards were put not to punish a criminal and make the person stop the crime, but the punishment was to strengthen the entire law to help control crime. Durkheim saw that punishment and crime go together and cannot be separated (Marsh 98).

Drawbacks of the perspective . Crime is has negative impacts and dangerous to the people and the community at large if is at high levels. If crime is not controlled and increases more and more each day, the society can be unable to prevent the criminals. On the other hand, if the crime rate is too low, the society maybe abnormal.

According to Durkheim the breaking of the society way of living or the norms is what brings in the social change which is very important in community development. Otherwise the social change should be controlled or moderate to avoid social problem. In any case the deviance which motivate the social change should be regulated so that to prevent the loss of criminal identity which it is important in the future (Marsh 95).

Durkheim failed to explain how for example division of labor would be used to control crime in the society. Also not all crimes would be beneficial to the society because if a crime resulted to killing or a big damage then the society will drag behind on development.

Lukes, Steven. The rules of the sociological method . New York: Free press, 2007.

Marsh, Ian., Melville, Gaynor. Theories of crime . Canada: Routledge, 2006

Moyer, Imogene. Criminological theories: traditional and non traditional voices . London: sage publishers, 2001.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, February 26). Crime and Deviance. https://ivypanda.com/essays/crime-and-deviance/

"Crime and Deviance." IvyPanda , 26 Feb. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/crime-and-deviance/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'Crime and Deviance'. 26 February.

IvyPanda . 2024. "Crime and Deviance." February 26, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/crime-and-deviance/.

1. IvyPanda . "Crime and Deviance." February 26, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/crime-and-deviance/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Crime and Deviance." February 26, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/crime-and-deviance/.

- Durkheim's Ideas on Social Solidarity

- Police Deviance

- "The Functions of Crime" by Emile Durkheim

- Emile Durkheim Life and Career

- Emile Durkheim's Theory of Functionalism

- Emile Durkheim and His Philosophy

- Functionalist Approach to Deviance and Crime

- Marxists and Functionalists' Views on Crime and Deviance

- Durkheim’s Methodology and Theory of Suicide

- Merton’s Argument of Deviance: The Case of Drug Abuse

- Stereotypes of American Citizens

- Social Care in Ireland

- Evaluating the debate between proponents of qualitative and quantitative inquiries

- The Effects of Social Networking Sites on an Individual's Life

- Parenting's Skills, Values and Styles

7.2 Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance and Crime

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you should be able to:

- Describe the functionalist view of deviance in society through four sociologist’s theories

- Explain how conflict theory understands deviance and crime in society

- Describe the symbolic interactionist approach to deviance, including labeling and other theories

Why does deviance occur? How does it affect a society? Since the early days of sociology, scholars have developed theories that attempt to explain what deviance and crime mean to society. These theories can be grouped according to the three major sociological paradigms: functionalism, symbolic interactionism, and conflict theory.

Functionalism

Sociologists who follow the functionalist approach are concerned with the way the different elements of a society contribute to the whole. They view deviance as a key component of a functioning society. Strain theory and social disorganization theory represent two functionalist perspectives on deviance in society.

Émile Durkheim: The Essential Nature of Deviance

Émile Durkheim believed that deviance is a necessary part of a successful society. One way deviance is functional, he argued, is that it challenges people’s present views (1893). For instance, when Black students across the United States participated in sit-ins during the civil rights movement, they challenged society’s notions of segregation. Moreover, Durkheim noted, when deviance is punished, it reaffirms currently held social norms, which also contributes to society (1893). Seeing a student given detention for skipping class reminds other high schoolers that playing hooky isn’t allowed and that they, too, could get detention.

Durkheim’s point regarding the impact of punishing deviance speaks to his arguments about law. Durkheim saw laws as an expression of the “collective conscience,” which are the beliefs, morals, and attitudes of a society. “A crime is a crime because we condemn it,” he said (1893). He discussed the impact of societal size and complexity as contributors to the collective conscience and the development of justice systems and punishments. For example, in large, industrialized societies that were largely bound together by the interdependence of work (the division of labor), punishments for deviance were generally less severe. In smaller, more homogeneous societies, deviance might be punished more severely.

Robert Merton: Strain Theory

Sociologist Robert Merton agreed that deviance is an inherent part of a functioning society, but he expanded on Durkheim’s ideas by developing strain theory , which notes that access to socially acceptable goals plays a part in determining whether a person conforms or deviates. From birth, we’re encouraged to achieve the “American Dream” of financial success. A person who attends business school, receives an MBA, and goes on to make a million-dollar income as CEO of a company is said to be a success. However, not everyone in our society stands on equal footing. That MBA-turned-CEO may have grown up in the best school district and had means to hire tutors. Another person may grow up in a neighborhood with lower-quality schools, and may not be able to pay for extra help. A person may have the socially acceptable goal of financial success but lack a socially acceptable way to reach that goal. According to Merton’s theory, an entrepreneur who can’t afford to launch their own company may be tempted to embezzle from their employer for start-up funds.

Merton defined five ways people respond to this gap between having a socially accepted goal and having no socially accepted way to pursue it.

- Conformity : Those who conform choose not to deviate. They pursue their goals to the extent that they can through socially accepted means.

- Innovation : Those who innovate pursue goals they cannot reach through legitimate means by instead using criminal or deviant means.

- Ritualism : People who ritualize lower their goals until they can reach them through socially acceptable ways. These members of society focus on conformity rather than attaining a distant dream.

- Retreatism : Others retreat and reject society’s goals and means. Some people who beg and people who are homeless have withdrawn from society’s goal of financial success.

- Rebellion : A handful of people rebel and replace a society’s goals and means with their own. Terrorists or freedom fighters look to overthrow a society’s goals through socially unacceptable means.

Social Disorganization Theory

Developed by researchers at the University of Chicago in the 1920s and 1930s, social disorganization theory asserts that crime is most likely to occur in communities with weak social ties and the absence of social control. An individual who grows up in a poor neighborhood with high rates of drug use, violence, teenage delinquency, and deprived parenting is more likely to become engaged in crime than an individual from a wealthy neighborhood with a good school system and families who are involved positively in the community.

Social disorganization theory points to broad social factors as the cause of deviance. A person isn’t born as someone who will commit crimes but becomes one over time, often based on factors in their social environment. Robert Sampson and Byron Groves (1989) found that poverty and family disruption in given localities had a strong positive correlation with social disorganization. They also determined that social disorganization was, in turn, associated with high rates of crime and delinquency—or deviance. Recent studies Sampson conducted with Lydia Bean (2006) revealed similar findings. High rates of poverty and single-parent homes correlated with high rates of juvenile violence. Research into social disorganization theory can greatly influence public policy. For instance, studies have found that children from disadvantaged communities who attend preschool programs that teach basic social skills are significantly less likely to engage in criminal activity. (Lally 1987)

Conflict Theory

Conflict theory looks to social and economic factors as the causes of crime and deviance. Unlike functionalists, conflict theorists don’t see these factors as positive functions of society. They see them as evidence of inequality in the system. They also challenge social disorganization theory and control theory and argue that both ignore racial and socioeconomic issues and oversimplify social trends (Akers 1991). Conflict theorists also look for answers to the correlation of gender and race with wealth and crime.

Karl Marx: An Unequal System

Conflict theory was greatly influenced by the work of German philosopher, economist, and social scientist Karl Marx. Marx believed that the general population was divided into two groups. He labeled the wealthy, who controlled the means of production and business, the bourgeois. He labeled the workers who depended on the bourgeois for employment and survival the proletariat. Marx believed that the bourgeois centralized their power and influence through government, laws, and other authority agencies in order to maintain and expand their positions of power in society. Though Marx spoke little of deviance, his ideas created the foundation for conflict theorists who study the intersection of deviance and crime with wealth and power.

C. Wright Mills: The Power Elite

In his book The Power Elite (1956), sociologist C. Wright Mills described the existence of what he dubbed the power elite , a small group of wealthy and influential people at the top of society who hold the power and resources. Wealthy executives, politicians, celebrities, and military leaders often have access to national and international power, and in some cases, their decisions affect everyone in society. Because of this, the rules of society are stacked in favor of a privileged few who manipulate them to stay on top. It is these people who decide what is criminal and what is not, and the effects are often felt most by those who have little power. Mills’ theories explain why celebrities can commit crimes and suffer little or no legal retribution. For example, USA Today maintains a database of NFL players accused and convicted of crimes. 51 NFL players had been convicted of committing domestic violence between the years 2000 and 2019. They have been sentenced to a collective 49 days in jail, and most of those sentences were deferred or otherwise reduced. In most cases, suspensions and fines levied by the NFL or individual teams were more severe than the justice system's (Schrotenboer 2020 and clickitticket.com 2019).

Crime and Social Class

While crime is often associated with the underprivileged, crimes committed by the wealthy and powerful remain an under-punished and costly problem within society. The FBI reported that victims of burglary, larceny, and motor vehicle theft lost a total of $15.3 billion dollars in 2009 (FB1 2010). In comparison, when former advisor and financier Bernie Madoff was arrested in 2008, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission reported that the estimated losses of his financial Ponzi scheme fraud were close to $50 billion (SEC 2009).

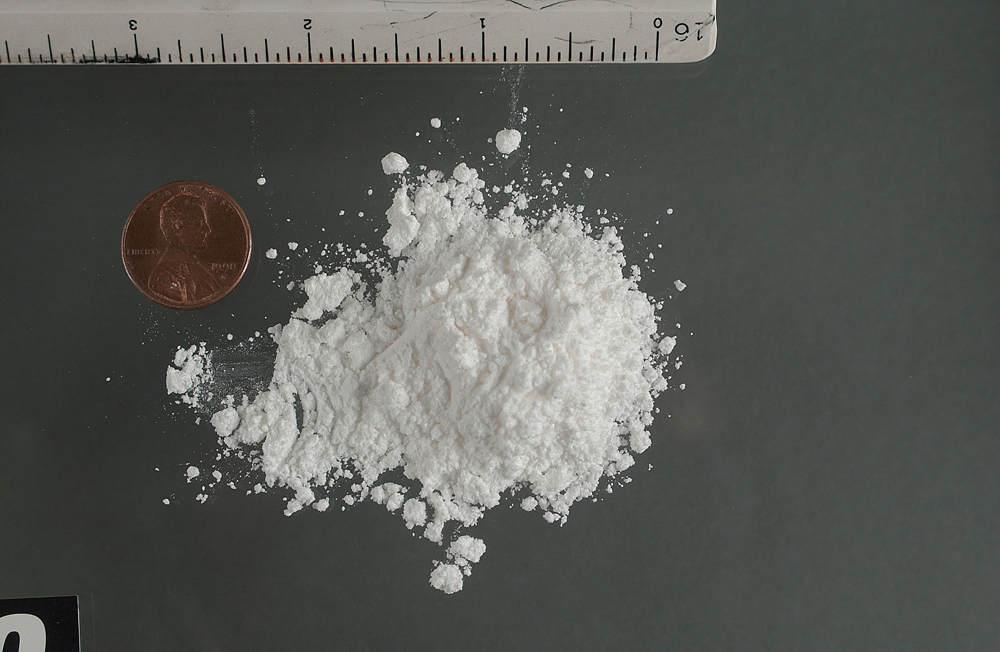

This imbalance based on class power is also found within U.S. criminal law. In the 1980s, the use of crack cocaine (a less expensive but powerful drug) quickly became an epidemic that swept the country’s poorest urban communities. Its pricier counterpart, cocaine, was associated with upscale users and was a drug of choice for the wealthy. The legal implications of being caught by authorities with crack versus cocaine were starkly different. In 1986, federal law mandated that being caught in possession of 50 grams of crack was punishable by a ten-year prison sentence. An equivalent prison sentence for cocaine possession, however, required possession of 5,000 grams. In other words, the sentencing disparity was 1 to 100 (New York Times Editorial Staff 2011). This inequality in the severity of punishment for crack versus cocaine paralleled the unequal social class of respective users. A conflict theorist would note that those in society who hold the power are also the ones who make the laws concerning crime. In doing so, they make laws that will benefit them, while the powerless classes who lack the resources to make such decisions suffer the consequences. Throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, states passed numerous laws increasing penalties, especially for repeat offenders. The U.S. government passed an even more significant law, the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 (known as the 1994 Crime Bill), which further increased penalties, funded prisons, and incentivized law enforcement agencies to further pursue drug offenders. One outcome of these policies was the mass incarceration of Black and Hispanic people, which led to a cycle of poverty and reduced social mobility. The crack-cocaine punishment disparity remained until 2010, when President Obama signed the Fair Sentencing Act, which decreased the disparity to 1 to 18 (The Sentencing Project 2010).

Symbolic Interactionism

Symbolic interactionism is a theoretical approach that can be used to explain how societies and/or social groups come to view behaviors as deviant or conventional.

Labeling Theory

Although all of us violate norms from time to time, few people would consider themselves deviant. Those who do, however, have often been labeled “deviant” by society and have gradually come to believe it themselves. Labeling theory examines the ascribing of a deviant behavior to another person by members of society. Thus, what is considered deviant is determined not so much by the behaviors themselves or the people who commit them, but by the reactions of others to these behaviors. As a result, what is considered deviant changes over time and can vary significantly across cultures.

Sociologist Edwin Lemert expanded on the concepts of labeling theory and identified two types of deviance that affect identity formation. Primary deviance is a violation of norms that does not result in any long-term effects on the individual’s self-image or interactions with others. Speeding is a deviant act, but receiving a speeding ticket generally does not make others view you as a bad person, nor does it alter your own self-concept. Individuals who engage in primary deviance still maintain a feeling of belonging in society and are likely to continue to conform to norms in the future.

Sometimes, in more extreme cases, primary deviance can morph into secondary deviance. Secondary deviance occurs when a person’s self-concept and behavior begin to change after his or her actions are labeled as deviant by members of society. The person may begin to take on and fulfill the role of a “deviant” as an act of rebellion against the society that has labeled that individual as such. For example, consider a high school student who often cuts class and gets into fights. The student is reprimanded frequently by teachers and school staff, and soon enough, develops a reputation as a “troublemaker.” As a result, the student starts acting out even more and breaking more rules; the student has adopted the “troublemaker” label and embraced this deviant identity. Secondary deviance can be so strong that it bestows a master status on an individual. A master status is a label that describes the chief characteristic of an individual. Some people see themselves primarily as doctors, artists, or grandfathers. Others see themselves as beggars, convicts, or addicts.

Techniques of Neutralization

How do people deal with the labels they are given? This was the subject of a study done by Sykes and Matza (1957). They studied teenage boys who had been labeled as juvenile delinquents to see how they either embraced or denied these labels. Have you ever used any of these techniques?

Let’s take a scenario and apply all five techniques to explain how they are used. A young person is working for a retail store as a cashier. Their cash drawer has been coming up short for a few days. When the boss confronts the employee, they are labeled as a thief for the suspicion of stealing. How does the employee deal with this label?

The Denial of Responsibility: When someone doesn’t take responsibility for their actions or blames others. They may use this technique and say that it was their boss’s fault because they don’t get paid enough to make rent or because they’re getting a divorce. They are rejecting the label by denying responsibility for the action.

The Denial of Injury: Sometimes people will look at a situation in terms of what effect it has on others. If the employee uses this technique they may say, “What’s the big deal? Nobody got hurt. Your insurance will take care of it.” The person doesn’t see their actions as a big deal because nobody “got hurt.”

The Denial of the Victim: If there is no victim there’s no crime. In this technique the person sees their actions as justified or that the victim deserved it. Our employee may look at their situation and say, “I’ve worked here for years without a raise. I was owed that money and if you won’t give it to me I’ll get it my own way.”

The Condemnation of the Condemners: The employee might “turn it around on” the boss by blaming them. They may say something like, “You don’t know my life, you have no reason to judge me.” This is taking the focus off of their actions and putting the onus on the accuser to, essentially, prove the person is living up to the label, which also shifts the narrative away from the deviant behavior.

Appeal to a Higher Authority: The final technique that may be used is to claim that the actions were for a higher purpose. The employee may tell the boss that they stole the money because their mom is sick and needs medicine or something like that. They are justifying their actions by making it seem as though the purpose for the behavior is a greater “good” than the action is “bad.” (Sykes & Matza, 1957)

Social Policy and Debate

The right to vote.

Before she lost her job as an administrative assistant, Leola Strickland postdated and mailed a handful of checks for amounts ranging from $90 to $500. By the time she was able to find a new job, the checks had bounced, and she was convicted of fraud under Mississippi law. Strickland pleaded guilty to a felony charge and repaid her debts; in return, she was spared from serving prison time.

Strickland appeared in court in 2001. More than ten years later, she is still feeling the sting of her sentencing. Why? Because Mississippi is one of twelve states in the United States that bans convicted felons from voting (ProCon 2011).

To Strickland, who said she had always voted, the news came as a great shock. She isn’t alone. Some 5.3 million people in the United States are currently barred from voting because of felony convictions (ProCon 2009). These individuals include inmates, parolees, probationers, and even people who have never been jailed, such as Leola Strickland.

Under the Fourteenth Amendment, states are allowed to deny voting privileges to individuals who have participated in “rebellion or other crime” (Krajick 2004). Although there are no federally mandated laws on the matter, most states practice at least one form of felony disenfranchisement .

Is it fair to prevent citizens from participating in such an important process? Proponents of disfranchisement laws argue that felons have a debt to pay to society. Being stripped of their right to vote is part of the punishment for criminal deeds. Such proponents point out that voting isn’t the only instance in which ex-felons are denied rights; state laws also ban released criminals from holding public office, obtaining professional licenses, and sometimes even inheriting property (Lott and Jones 2008).

Opponents of felony disfranchisement in the United States argue that voting is a basic human right and should be available to all citizens regardless of past deeds. Many point out that felony disfranchisement has its roots in the 1800s, when it was used primarily to block Black citizens from voting. These laws disproportionately target poor minority members, denying them a chance to participate in a system that, as a social conflict theorist would point out, is already constructed to their disadvantage (Holding 2006). Those who cite labeling theory worry that denying deviants the right to vote will only further encourage deviant behavior. If ex-criminals are disenfranchised from voting, are they being disenfranchised from society?

Edwin Sutherland: Differential Association

In the early 1900s, sociologist Edwin Sutherland sought to understand how deviant behavior developed among people. Since criminology was a young field, he drew on other aspects of sociology including social interactions and group learning (Laub 2006). His conclusions established differential association theory , which suggested that individuals learn deviant behavior from those close to them who provide models of and opportunities for deviance. According to Sutherland, deviance is less a personal choice and more a result of differential socialization processes. For example, a young person whose friends are sexually active is more likely to view sexual activity as acceptable. Sutherland developed a series of propositions to explain how deviance is learned. In proposition five, for example, he discussed how people begin to accept and participate in a behavior after learning whether it is viewed as “favorable” by those around them. In proposition six, Sutherland expressed the ways that exposure to more “definitions” favoring the deviant behavior than those opposing it may eventually lead a person to partake in deviance (Sutherland 1960), applying almost a quantitative element to the learning of certain behaviors. In the example above, a young person may find sexual activity more acceptable once a certain number of their friends become sexually active, not after only one does so.

Sutherland’s theory may explain why crime is multigenerational. A longitudinal study beginning in the 1960s found that the best predictor of antisocial and criminal behavior in children was whether their parents had been convicted of a crime (Todd and Jury 1996). Children who were younger than ten years old when their parents were convicted were more likely than other children to engage in spousal abuse and criminal behavior by their early thirties. Even when taking socioeconomic factors such as dangerous neighborhoods, poor school systems, and overcrowded housing into consideration, researchers found that parents were the main influence on the behavior of their offspring (Todd and Jury 1996).

Travis Hirschi: Control Theory

Continuing with an examination of large social factors, control theory states that social control is directly affected by the strength of social bonds and that deviance results from a feeling of disconnection from society. Individuals who believe they are a part of society are less likely to commit crimes against it.

Travis Hirschi (1969) identified four types of social bonds that connect people to society:

- Attachment measures our connections to others. When we are closely attached to people, we worry about their opinions of us. People conform to society’s norms in order to gain approval (and prevent disapproval) from family, friends, and romantic partners.

- Commitment refers to the investments we make in the community. A well-respected local businessperson who volunteers at their synagogue and is a member of the neighborhood block organization has more to lose from committing a crime than a person who doesn’t have a career or ties to the community.

- Similarly, levels of involvement , or participation in socially legitimate activities, lessen a person’s likelihood of deviance. A child who plays little league baseball and takes art classes has fewer opportunities to ______.

- The final bond, belief , is an agreement on common values in society. If a person views social values as beliefs, they will conform to them. An environmentalist is more likely to pick up trash in a park, because a clean environment is a social value to them (Hirschi 1969).

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Introduction to Sociology 3e

- Publication date: Jun 3, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/7-2-theoretical-perspectives-on-deviance-and-crime

© Jan 18, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Sociology of Deviance and Crime

The Study of Cultural Norms and What Happens When They Are Broken

- News & Issues

- Key Concepts

- Major Sociologists

- Research, Samples, and Statistics

- Recommended Reading

- Archaeology

Sociologists who study deviance and crime examine cultural norms, how they change over time, how they are enforced, and what happens to individuals and societies when norms are broken. Deviance and social norms vary among societies, communities, and times, and often sociologists are interested in why these differences exist and how these differences impact the individuals and groups in those areas.

Sociologists define deviance as behavior that is recognized as violating expected rules and norms . It is simply more than nonconformity, however; it is behavior that departs significantly from social expectations. In the sociological perspective on deviance, there is a subtlety that distinguishes it from our commonsense understanding of the same behavior. Sociologists stress social context, not just individual behavior. That is, deviance is looked at in terms of group processes, definitions, and judgments, and not just as unusual individual acts. Sociologists also recognize that not all behaviors are judged similarly by all groups. What is deviant to one group may not be considered deviant to another. Further, sociologists recognize that established rules and norms are socially created, not just morally decided or individually imposed. That is, deviance lies not just in the behavior itself, but in the social responses of groups to behavior by others.

Sociologists often use their understanding of deviance to help explain otherwise ordinary events, such as tattooing or body piercing, eating disorders, or drug and alcohol use. Many of the kinds of questions asked by sociologists who study deviance deal with the social context in which behaviors are committed. For example, are there conditions under which suicide is acceptable ? Would one who commits suicide in the face of a terminal illness be judged differently from a despondent person who jumps from a window?

Four Theoretical Approaches

Within the sociology of deviance and crime, there are four key theoretical perspectives from which researchers study why people violate laws or norms, and how society reacts to such acts. We'll review them briefly here.

Structural strain theory was developed by American sociologist Robert K. Merton and suggests that deviant behavior is the result of strain an individual may experience when the community or society in which they live does not provide the necessary means to achieve culturally valued goals. Merton reasoned that when society fails people in this way, they engage in deviant or criminal acts in order to achieve those goals (like economic success, for example).

Some sociologists approach the study of deviance and crime from a structural functionalist standpoint . They would argue that deviance is a necessary part of the process by which social order is achieved and maintained. From this standpoint, deviant behavior serves to remind the majority of the socially agreed upon rules, norms, and taboos , which reinforces their value and thus social order.

Conflict theory is also used as a theoretical foundation for the sociological study of deviance and crime. This approach frames deviant behavior and crime as the result of social, political, economic, and material conflicts in society. It can be used to explain why some people resort to criminal trades simply in order to survive in an economically unequal society.

Finally, labeling theory serves as an important frame for those who study deviance and crime. Sociologists who follow this school of thought would argue that there is a process of labeling by which deviance comes to be recognized as such. From this standpoint, the societal reaction to deviant behavior suggests that social groups actually create deviance by making the rules whose infraction constitutes deviance, and by applying those rules to particular people and labeling them as outsiders. This theory further suggests that people engage in deviant acts because they have been labeled as deviant by society, because of their race, or class, or the intersection of the two, for example.

Updated by Nicki Lisa Cole, Ph.D.

- An Overview of Labeling Theory

- The Life and Work of Howard S. Becker

- Deviance and Strain Theory in Sociology

- The Sociological Definition of Anomie

- Major Sociological Theories

- How Psychology Defines and Explains Deviant Behavior

- What Is Social Order in Sociology?

- Definition of Ritualism in Sociology

- What is a Norm? Why Does it Matter?

- Criminology Definition and History

- What Is Social Learning Theory?

- A Sociological Understanding of Moral Panic

- Using Ethnomethodology to Understand Social Order

- Units of Analysis as Related to Sociology

- The Sociology of Education

- A Brief Overview of Émile Durkheim and His Historic Role in Sociology

ReviseSociology

A level sociology revision – education, families, research methods, crime and deviance and more!

Crime and Deviance

Table of Contents

Last Updated on November 14, 2023 by Karl Thompson

This page provides links to blog posts on the main topics of the AQA’s Crime and Deviance module. It includes links to posts on sociological perspectives on crime (Functionalism, strain theory etc); crime control and punishment, including surveillance; the relationship between class, gender, ethnicity and crime; and globalisation, state and green crime (everyone’s favourite!).

Introductory Material

Sociological Perspectives on the London Riots – The London Riots remain the biggest act of mass criminality of the 2000s, I like to use them to introduce sociological perspectives on crime and deviance. You can also use this as an example of how media narratives on the causes of the riots differ so much from the London School of Economics research findings on the actual ’causes’ of the riots.

Perspectives on Crime and Deviance – A Very Brief Overview – A summary grid of 21 theorists, their ‘key points’, their ‘perspective’ and an evaluation. If you like you can cut and paste, cut it up and use it as a sentence sort!

Key Concepts for A Level Sociology Crime and Deviance – definitions of most of the key concepts relevant to crime and deviance within A-level sociology.

Hints on how to answer the AQA’s Sociology Crime and Deviance with Theory and Methods exam paper – in case you need to know how you’re assessed (only covers the crime and deviance material).

The social construction of crime – a timeline of some relatively recent events that have been criminalised due to changes in the law – once they weren’t criminal, now they are! (U.K. focus).

Consensus Theories of Crime and Deviance

The Functionalist Perspective on Crime and Deviance – class notes covering Durkhiem’s ‘society of saints’ (the inevitability of crime), and his views on the positive functions of crime – social integration, social regulation and allowing for social change.

Hirschi’s Social Control Theory of Crime – class notes covering Hirschi’s four bonds of attachment – attachment, commitment, involvement and belief.

Robert Merton’s Strain Theory – class notes: the easy summary of Merton’s strain theory is that people who try to succeed by normal means (getting a job for example) and fail turn to crime in oder to achieve what they couldn’t through normal means.

Functionalism and Strain Theories of Crime – summary revision notes – a briefer version of the three posts above.

Subcultural Theories of Deviance – class notes on mainly Albert Cohen’s consensus theory of status frustration, but also with details of other subcultural theories (e.g. Willis).

Subcultural Theories of Crime – summary revision version of the above.

The Underclass Theory of Crime – brief class notes covering Charle’s Murray’s theory of the underclass. Murray argues the long term unemployed get cut off over the generations and socialise their kids into a culture of worklesseness and criminality.

Marxist Theories of Crime and Deviance

The Marxist Perspective on Crime – very detailed class notes covering concepts such as crimogenic capitalism, the costs of corporate crime and the ideological functions of selective law enforcement.

The Marxist Perspective on Crime – summary revision notes of the above.

Evaluating the Marxist Perspective on Crime – evaluative posts, mostly links to research which supports the Marxist perspective on crime.

Assess the Contribution of Marxism to our Understanding of Crime and Deviance – an outline 30 mark essay plan.

Interactionist Theories of Crime and Deviance

The Labelling Theory of Crime – very detailed class notes covering concepts such as labelling as applied to education and crime, the self fulfilling prophecy, Howard Becker’s Master Status, and Cicourel’s Negotiation of Justice.

The Labelling Theory of Crime – brief summary notes of the above.

Realist Theories of Crime and Deviance

Right Realist Criminology – Includes an introduction to Realism and detailed class notes on Right Realism covering rational choice theory, broken windows theory, Charles Murray’s views on the underclass, situational crime prevention and environmental crime prevention (mainly zero tolerance policing)

Evaluating Broken Windows Theory – evaluative post. Wilson and Kelling’s Broken Windows Theory has been referred to as ‘the most influential theory of crime control’ of recent decades, this post offers some evaluations of this theory. (Spoiler Alert – it doesn’t hold up to scrutiny very well!)

Environmental Crime Prevention – Definition and Examples – supplementary notes to Right Realism covering zero tolerance policing and ASBOs

Public Space Protection Orders and Criminal Behaviour Orders – supplementary notes to Right Realist policies of crime control

Left Realist Criminology – class notes covering relative deprivation, marginalisation, subcultures, early intervention, community based solutions to crime and community policing

Post and Late Modern Theories of Crime and Deviance

Post/ Late Modern Criminology – brief summary notes covering how crime has changed with shift to post modernity , which as resulted in society being more consumerist, more fragment and more globalized , as well as summaries of Jock Young and Cultural Criminology (covered in more detail below)

Jock Young – Late Modernity, Exclusion and Crime – Jock Young argues that more people suffer from the ‘Vertigo of Late Modernity’ in late modern society. This is essentially a state of extreme anomie, and this is kind of an updated version of Strain Theory.

Cultural Criminology – Crime as Edgework – argues that a lot of crime is done for thrill for of it today.

Foucault – Surveillance and Crime Control – A very simplified explanation of Foucault, who argued that surveillance by agents of the state becomes more important for social control in modernity than the threat of physical punishment .

Synoptic Surveillance and Crime Control – synoptic surveillance is surveillance from below rather than surveillance from above. In simple terms it means all of us watching each other rather than just the state watching citizens.

Actuarial Justice and Risk Management – this is statistical surveillance, a form of surveillance long used by insurance companies, but increasingly used by state agencies. It is where people who have a statistically higher risk of truanting/ offending/ failing will be under a higher level of surveillance than the norm.

Controlling and Reducing Crime – the Role of the Community, the Police and Different Forms of Punishment

Crime Prevention and Control Strategies – very brief summary revision notes on situational crime prevention, environmental crime prevention and community crime control strategies

The Role of the Community in Controlling and Reducing Crime – a summary of consensus, right realist, left realist and postmodern perspectives on the community in controlling crime

The Role of the Police in Controlling and Reducing Crime – right and left realists both tend to be on the side of the police, but right realists believe the police should be more ‘militaristic’, while left realists emphasise that they should work with communities and avoid being antagonistic. Marxists and interactionists tend to see the police as being ‘the problem’ and are more likely to side with the criminals.

Sociological Perspectives on Punishment – summary notes covering the Consensus, Marxist, interactionist, Realist and Postmodern views on punishment.

Does Prison Work? – an evaluative post looking at some of the evidence on whether prison works to prevent crime. Spoiler alert: it generally doesn’t!

Social Class and Crime

Social Class and Crime – detailed class notes covering the consensus view which tends to see most crime being committed by the working classes and the underclass, hence these classes are seen as part of the problem of crime; this is contrasted with mainly the Marxist view which sees all classes as committing crime, with agents of social control largely ignoring elite crime.

Outline and Analyse Two Ways in Which Patterns of Crime Vary by Social Class – 10 mark exam style question

See also the perspective links above, especially Marxism!

Ethnicity and Crime

Official Statistics on Ethnicity and Crime – Official statistics suggest that black people are around 6 times more likely to go to jail than white people, while Asians are 2-3 times more likely to go to jail . Of course there are limitations to these statistics!

Ethnicity and Crime – The Role of Cultural Factors – structural theorists focus on some of the background differences between ethnic groups. Pointing out, for example, that the high rates of absent fathers among British-Caribbean households may explain the higher rates of recorded offending by ‘black’ boys especially.

Left Realist Explanations for Ethnic Differences in Crime – left realists explain the higher rates of offending among certain ethnic groups as being due to higher rates of relative deprivation and marginalisation.

Neo-Marxist Approaches to Ethnicity and Crime – Applying the fully social theory of deviance to explaining the higher rates of black offending.

Paul Gilroy’s Anti-Racist Theory – summary notes on this classic text, taken from Haralambos.

Criminal Justice, Ethnicity and Racism – Selected Key Statistics – evaluative post

Racism in the Criminal Justice System – Selected Evidence – there is A LOT of evidence that suggests the police are racist – the stop and search stats alone point to this, with black people being almost 30 times as likely to be stopped compared to white people in some circumstances. There is also more qualitative evidence based on Participant Observation which suggests this.

Ethnicity and Crime – Two examples of possible short answer 4 and 6 mark ‘outline’ questions.

Outline and Analyse Question on Police Racism – 10 mark exam question and answer – ‘Analyse two criticisms of the theory that police racism is the main factor which explains the higher imprisonment rates of ethnic minorities’

Gender and Crime

Sex-Role Theory – suggests that women commit less crime than men because of their different roles in society, such as the motherhood role, which results in them being more constrained and more caring and responsible.

The Liberationist Perspective on the (Long Term) Increase in the Female Crime Rate – This classic Liberal Feminist perspective argues that the female crime rate has increased in line with female liberation.

Globalisation, state and green crime

Globalisation, global criminal networks and crime – covering Misha Glenny’s work on the McMafia. He argues that the growth of the Mafia in ex-communist countries such as Bulgaria have been central to the growth of global crime – because they are perfectly located to ship illegal products such as drugs and sex-slaves from the global south to meet demand in the wealth global north.

Capitalism, Globalisation and Crime – A Marxist perspective on global crime covering global finance and tax havens and TNCs and law evasion.

What is State Crime? – A simple explanation is that state crimes are crimes committed by governments, which are in breach of human rights. Historically the Nazi Genocide is the most obvious example.

Sociological perspectives on state crime – covering the different types of state crime and a slightly unusual take applying material from global development to analyse state crime.

Green crime and green criminology – revision notes covering primary and secondary green crime, Ulrich Beck’s Risk Society theory and Marxist views of Green Crime.

Victimology

Victimology – covering trends in victimisation, and positivist and critical victimology .

The Economic and Social Costs of Crime – a summary of a recent (2021) government report looking at the social and economic harms crime does in England and Wales .

What are the impacts of crime on victims ? – a post examining how crime affects individuals and their families, including a look at secondary victimisation.

The Media and Crime

How the Media Simplifies Crime – a brief post summarising how the media tends to take the side of the police and victims, focus on crimes with easy to understand individual ‘harm’ stories and provide a narrow analysis of crime control options .

Sensationalisation of Crime in the Media – There are a lot of fictional programmes about crime in the UK, many of them tend to present criminal characters as likeable and make the hideous crimes they commit (in fiction) seem ‘cool’ .

Moral Panics and The Media – brief class notes covering the definition of a moral panic, Stan Cohen’s work on the Mods and Rockers and some criticisms.

The Exaggeration of Violent and Sexual Crimes in the Media – The mainstream media exaggerates the extent of violent crime 10 times, tending to focus a lot more on very serious horrific crimes rather than less serious crimes which are much more common according to official statistics .

What is CyberCrime ? – A long form post examining crimes such as identify theft, online fraud, ransomware attacks and phishing scams.

Posts on Specific Types of Crime

How do we explain the recent surge in Knife Crime? – exploring this is a useful way to evaluate Right Realist theories of deviance especially.

Sociological Perspectives on Hate Crime – a very ‘postmodern’ type of crime, but some of the other sociological perspectives can also help us understand this crime.

How is Coronavirus affecting crime and deviance? – all of a sudden certain acts that used to be ‘normal’ are now criminal, this is perfect analytical feeding ground for any A-level sociology student!

Fraud and Computer Misuse – this seems to be one of the more common types of crime. Roughly one in five adults was a victim to the twelve months ending December 2020.

Crime and Deviance Revision Bundle for Sale

If you like this sort of thing then you might like my Crime and Deviance Revision Bundle.

It contains

- 12 exam practice questions including short answer, 10 mark and essay question exemplars.

- 32 pages of revision notes covering the entire A-level sociology crime and deviance specification

- Seven colour mind maps covering sociological perspective on crime and deviance

Written specifically for the AQA sociology A-level specification.

A-level sociology revision mega bundle…

For better value I’ve bundled all of the above topics into six revision bundles , containing revision notes, mind maps, and exam question and answers, available for between £4.99 and £5.99 on Sellfy .

Best value is my A level sociology revision mega bundle – which contains the following:

- over 200 pages of revision notes

- 60 mind maps in pdf and png formats

- 50 short answer exam practice questions and exemplar answers

- Covers the entire A-level sociology syllabus, AQA focus.

Crime and Deviance in Contemporary Society

Below are some selected, recent posts outlining how you might use contemporary examples to illustrate key concepts within crime and deviance. Examiners like this sort of contemporary focus!

How Coronavirus is changing crime – all of a sudden sitting on a park bench was illegal!

The deportation of foreign nationals – an example of a state crime? Outlines when the UK government tried to deport 42 criminals (in some cases ‘criminals’) back to Jamaica on their release from prison, despite the fact that some of them had been in the UK since they were children!

Contemporary examples of crime and deviance in the news – further examples from 2019 and 2018 which are relevant to A-level sociology.

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7.2 Explaining Deviance

Learning objective.

- State the major arguments and assumptions of the various sociological explanations of deviance.

If we want to reduce violent crime and other serious deviance, we must first understand why it occurs. Many sociological theories of deviance exist, and together they offer a more complete understanding of deviance than any one theory offers by itself. Together they help answer the questions posed earlier: why rates of deviance differ within social categories and across locations, why some behaviors are more likely than others to be considered deviant, and why some kinds of people are more likely than others to be considered deviant and to be punished for deviant behavior. As a whole, sociological explanations highlight the importance of the social environment and of social interaction for deviance and the commision of crime. As such, they have important implications for how to reduce these behaviors. Consistent with this book’s public sociology theme, a discussion of several such crime-reduction strategies concludes this chapter.

We now turn to the major sociological explanations of crime and deviance. A summary of these explanations appears in Table 7.1 “Theory Snapshot: Summary of Sociological Explanations of Deviance and Crime” .

Table 7.1 Theory Snapshot: Summary of Sociological Explanations of Deviance and Crime

Functionalist Explanations

Several explanations may be grouped under the functionalist perspective in sociology, as they all share this perspective’s central view on the importance of various aspects of society for social stability and other social needs.

Émile Durkheim: The Functions of Deviance

As noted earlier, Émile Durkheim said deviance is normal, but he did not stop there. In a surprising and still controversial twist, he also argued that deviance serves several important functions for society.

First, Durkheim said, deviance clarifies social norms and increases conformity. This happens because the discovery and punishment of deviance reminds people of the norms and reinforces the consequences of violating them. If your class were taking an exam and a student was caught cheating, the rest of the class would be instantly reminded of the rules about cheating and the punishment for it, and as a result they would be less likely to cheat.

A second function of deviance is that it strengthens social bonds among the people reacting to the deviant. An example comes from the classic story The Ox-Bow Incident (Clark, 1940), in which three innocent men are accused of cattle rustling and are eventually lynched. The mob that does the lynching is very united in its frenzy against the men, and, at least at that moment, the bonds among the individuals in the mob are extremely strong.

A final function of deviance, said Durkheim, is that it can help lead to positive social change. Although some of the greatest figures in history—Socrates, Jesus, Joan of Arc, Mahatma Gandhi, and Martin Luther King Jr. to name just a few—were considered the worst kind of deviants in their time, we now honor them for their commitment and sacrifice.

Émile Durkheim wrote that deviance can lead to positive social change. Many Southerners had strong negative feelings about Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. during the civil rights movement, but history now honors him for his commitment and sacrifice.

U.S. Library of Congress – public domain.

Sociologist Herbert Gans (1996) pointed to an additional function of deviance: deviance creates jobs for the segments of society—police, prison guards, criminology professors, and so forth—whose main focus is to deal with deviants in some manner. If deviance and crime did not exist, hundreds of thousands of law-abiding people in the United States would be out of work!

Although deviance can have all of these functions, many forms of it can certainly be quite harmful, as the story of the mugged voter that began this chapter reminds us. Violent crime and property crime in the United States victimize millions of people and households each year, while crime by corporations has effects that are even more harmful, as we discuss later. Drug use, prostitution, and other “victimless” crimes may involve willing participants, but these participants often cause themselves and others much harm. Although deviance according to Durkheim is inevitable and normal and serves important functions, that certainly does not mean the United States and other nations should be happy to have high rates of serious deviance. The sociological theories we discuss point to certain aspects of the social environment, broadly defined, that contribute to deviance and crime and that should be the focus of efforts to reduce these behaviors.

Social Ecology: Neighborhood and Community Characteristics

An important sociological approach, begun in the late 1800s and early 1900s by sociologists at the University of Chicago, stresses that certain social and physical characteristics of urban neighborhoods raise the odds that people growing up and living in these neighborhoods will commit deviance and crime. This line of thought is now called the social ecology approach (Mears, Wang, Hay, & Bales, 2008). Many criminogenic (crime-causing) neighborhood characteristics have been identified, including high rates of poverty, population density, dilapidated housing, residential mobility, and single-parent households. All of these problems are thought to contribute to social disorganization , or weakened social bonds and social institutions, that make it difficult to socialize children properly and to monitor suspicious behavior (Mears, Wang, Hay, & Bales, 2008; Sampson, 2006).

Sociology Making a Difference

Improving Neighborhood Conditions Helps Reduce Crime Rates

One of the sociological theories of crime discussed in the text is the social ecology approach. To review, this approach attributes high rates of deviance and crime to the neighborhood’s social and physical characteristics, including poverty, high population density, dilapidated housing, and high population turnover. These problems create social disorganization that weakens the neighborhood’s social institutions and impairs effective child socialization.

Much empirical evidence supports social ecology’s view about negative neighborhood conditions and crime rates and suggests that efforts to improve these conditions will lower crime rates. Some of the most persuasive evidence comes from the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods (directed by sociologist Robert J. Sampson), in which more than 6,000 children, ranging in age from birth to 18, and their parents and other caretakers were studied over a 7-year period. The social and physical characteristics of the dozens of neighborhoods in which the subjects lived were measured to permit assessment of these characteristics’ effects on the probability of delinquency. A number of studies using data from this project confirm the general assumptions of the social ecology approach. In particular, delinquency is higher in neighborhoods with lower levels of “collective efficacy,” that is, in neighborhoods with lower levels of community supervision of adolescent behavior.

The many studies from the Chicago project and data in several other cities show that neighborhood conditions greatly affect the extent of delinquency in urban neighborhoods. This body of research in turn suggests that strategies and programs that improve the social and physical conditions of urban neighborhoods may well help decrease the high rates of crime and delinquency that are so often found there. (Bellair & McNulty, 2009; Sampson, 2006)

Strain Theory

Failure to achieve the American dream lies at the heart of Robert Merton’s (1938) famous strain theory (also called anomie theory). Recall from Chapter 1 “Sociology and the Sociological Perspective” that Durkheim attributed high rates of suicide to anomie, or normlessness, that occurs in times when social norms are unclear or weak. Adapting this concept, Merton wanted to explain why poor people have higher deviance rates than the nonpoor. He reasoned that the United States values economic success above all else and also has norms that specify the approved means, working, for achieving economic success. Because the poor often cannot achieve the American dream of success through the conventional means of working, they experience a gap between the goal of economic success and the means of working. This gap, which Merton likened to Durkheim’s anomie because of the resulting lack of clarity over norms, leads to strain or frustration. To reduce their frustration, some poor people resort to several adaptations, including deviance, depending on whether they accept or reject the goal of economic success and the means of working. Table 7.2 “Merton’s Anomie Theory” presents the logical adaptations of the poor to the strain they experience. Let’s review these briefly.

Table 7.2 Merton’s Anomie Theory

Despite their strain, most poor people continue to accept the goal of economic success and continue to believe they should work to make money. In other words, they continue to be good, law-abiding citizens. They conform to society’s norms and values, and, not surprisingly, Merton calls their adaptation conformity .

Faced with strain, some poor people continue to value economic success but come up with new means of achieving it. They rob people or banks, commit fraud, or use other illegal means of acquiring money or property. Merton calls this adaptation innovation .

Other poor people continue to work at a job without much hope of greatly improving their lot in life. They go to work day after day as a habit. Merton calls this third adaptation ritualism . This adaptation does not involve deviant behavior but is a logical response to the strain poor people experience.

One of Robert Merton’s adaptations in his strain theory is retreatism, in which poor people abandon society’s goal of economic success and reject its means of employment to reach this goal. Many of today’s homeless people might be considered retreatists under Merton’s typology.

Franco Folini – Homeless woman with dogs – CC BY-SA 2.0.

In Merton’s fourth adaptation, retreatism , some poor people withdraw from society by becoming hobos or vagrants or by becoming addicted to alcohol, heroin, or other drugs. Their response to the strain they feel is to reject both the goal of economic success and the means of working.

Merton’s fifth and final adaptation is rebellion . Here poor people not only reject the goal of success and the means of working but work actively to bring about a new society with a new value system. These people are the radicals and revolutionaries of their time. Because Merton developed his strain theory in the aftermath of the Great Depression, in which the labor and socialist movements had been quite active, it is not surprising that he thought of rebellion as a logical adaptation of the poor to their lack of economic success.

Although Merton’s theory has been popular over the years, it has some limitations. Perhaps most important, it overlooks deviance such as fraud by the middle and upper classes and also fails to explain murder, rape, and other crimes that usually are not done for economic reasons. It also does not explain why some poor people choose one adaptation over another.

Merton’s strain theory stimulated other explanations of deviance that built on his concept of strain. Differential opportunity theory , developed by Richard Cloward and Lloyd Ohlin (1960), tried to explain why the poor choose one or the other of Merton’s adaptations. Whereas Merton stressed that the poor have differential access to legitimate means (working), Cloward and Ohlin stressed that they have differential access to illegitimate means . For example, some live in neighborhoods where organized crime is dominant and will get involved in such crime; others live in neighborhoods rampant with drug use and will start using drugs themselves.

In a more recent formulation, two sociologists, Steven F. Messner and Richard Rosenfeld (2007), expanded Merton’s view by arguing that in the United States crime arises from several of our most important values, including an overemphasis on economic success, individualism, and competition. These values produce crime by making many Americans, rich or poor, feel they never have enough money and by prompting them to help themselves even at other people’s expense. Crime in the United States, then, arises ironically from the country’s most basic values.

In yet another extension of Merton’s theory, Robert Agnew (2007) reasoned that adolescents experience various kinds of strain in addition to the economic type addressed by Merton. A romantic relationship may end, a family member may die, or students may be taunted or bullied at school. Repeated strain-inducing incidents such as these produce anger, frustration, and other negative emotions, and these emotions in turn prompt delinquency and drug use.

Deviant Subcultures

Some sociologists stress that poverty and other community conditions give rise to certain subcultures through which adolescents acquire values that promote deviant behavior. One of the first to make this point was Albert K. Cohen (1955), whose status frustration theory says that lower-class boys do poorly in school because schools emphasize middle-class values. School failure reduces their status and self-esteem, which the boys try to counter by joining juvenile gangs. In these groups, a different value system prevails, and boys can regain status and self-esteem by engaging in delinquency. Cohen had nothing to say about girls, as he assumed they cared little about how well they did in school, placing more importance on marriage and family instead, and hence would remain nondelinquent even if they did not do well. Scholars later criticized his disregard for girls and assumptions about them.

Another sociologist, Walter Miller (1958), said poor boys become delinquent because they live amid a lower-class subculture that includes several focal concerns , or values, that help lead to delinquency. These focal concerns include a taste for trouble, toughness, cleverness, and excitement. If boys grow up in a subculture with these values, they are more likely to break the law. Their deviance is a result of their socialization. Critics said Miller exaggerated the differences between the value systems in poor inner-city neighborhoods and wealthier, middle-class communities (Akers & Sellers, 2008).

A very popular subcultural explanation is the so-called subculture of violence thesis, first advanced by Marvin Wolfgang and Franco Ferracuti (1967). In some inner-city areas, they said, a subculture of violence promotes a violent response to insults and other problems, which people in middle-class areas would probably ignore. The subculture of violence, they continued, arises partly from the need of lower-class males to “prove” their masculinity in view of their economic failure. Quantitative research to test their theory has failed to show that the urban poor are more likely than other groups to approve of violence (Cao, Adams, & Jensen, 1997). On the other hand, recent ethnographic (qualitative) research suggests that large segments of the urban poor do adopt a “code” of toughness and violence to promote respect (Anderson, 1999). As this conflicting evidence illustrates, the subculture of violence view remains controversial and merits further scrutiny.

Social Control Theory

Travis Hirschi (1969) argued that human nature is basically selfish and thus wondered why people do not commit deviance. His answer, which is now called social control theory (also known as social bonding theory ), was that their bonds to conventional social institutions such as the family and the school keep them from violating social norms. Hirschi’s basic perspective reflects Durkheim’s view that strong social norms reduce deviance such as suicide.

Hirschi outlined four types of bonds to conventional social institutions: attachment, commitment, involvement, and belief.

- Attachment refers to how much we feel loyal to these institutions and care about the opinions of people in them, such as our parents and teachers. The more attached we are to our families and schools, the less likely we are to be deviant.

- Commitment refers to how much we value our participation in conventional activities such as getting a good education. The more committed we are to these activities and the more time and energy we have invested in them, the less deviant we will be.

- Involvement refers to the amount of time we spend in conventional activities. The more time we spend, the less opportunity we have to be deviant.

- Belief refers to our acceptance of society’s norms. The more we believe in these norms, the less we deviate.

Travis Hirschi’s social control theory stresses the importance of bonds to social institutions for preventing deviance. His theory emphasized the importance of attachment to one’s family in this regard.

More Good Foundation – Mormon Family Dinner – CC BY-NC 2.0.

Hirschi’s theory has been very popular. Many studies find that youths with weaker bonds to their parents and schools are more likely to be deviant. But the theory has its critics (Akers & Sellers, 2008). One problem centers on the chicken-and-egg question of causal order. For example, many studies support social control theory by finding that delinquent youths often have worse relationships with their parents than do nondelinquent youths. Is that because the bad relationships prompt the youths to be delinquent, as Hirschi thought? Or is it because the youths’ delinquency worsens their relationship with their parents? Despite these questions, Hirschi’s social control theory continues to influence our understanding of deviance. To the extent it is correct, it suggests several strategies for preventing crime, including programs designed to improve parenting and relations between parents and children (Welsh & Farrington, 2007).

Conflict and Feminist Explanations

Explanations of crime rooted in the conflict perspective reflect its general view that society is a struggle between the “haves” at the top of society with social, economic, and political power and the “have-nots” at the bottom. Accordingly, they assume that those with power pass laws and otherwise use the legal system to secure their position at the top of society and to keep the powerless on the bottom (Bohm & Vogel, 2011). The poor and minorities are more likely because of their poverty and race to be arrested, convicted, and imprisoned. These explanations also blame street crime by the poor on the economic deprivation and inequality in which they live rather than on any moral failings of the poor.

Some conflict explanations also say that capitalism helps create street crime by the poor. An early proponent of this view was Dutch criminologist Willem Bonger (1916), who said that capitalism as an economic system involves competition for profit. This competition leads to an emphasis in a capitalist society’s culture on egoism , or self-seeking behavior, and greed . Because profit becomes so important, people in a capitalist society are more likely than those in noncapitalist ones to break the law for profit and other gains, even if their behavior hurts others.

Not surprisingly, conflict explanations have sparked much controversy (Akers & Sellers, 2008). Many scholars dismiss them for painting an overly critical picture of the United States and ignoring the excesses of noncapitalistic nations, while others say the theories overstate the degree of inequality in the legal system. In assessing the debate over conflict explanations, a fair conclusion is that their view on discrimination by the legal system applies more to victimless crime (discussed in a later section) than to conventional crime, where it is difficult to argue that laws against such things as murder and robbery reflect the needs of the powerful. However, much evidence supports the conflict assertion that the poor and minorities face disadvantages in the legal system (Reiman & Leighton, 2010). Simply put, the poor cannot afford good attorneys, private investigators, and the other advantages that money brings in court. As just one example, if someone much poorer than O. J. Simpson, the former football player and media celebrity, had been arrested, as he was in 1994, for viciously murdering two people, the defendant would almost certainly have been found guilty. Simpson was able to afford a defense costing hundreds of thousands of dollars and won a jury acquittal in his criminal trial (Barkan, 1996). Also in accordance with conflict theory’s views, corporate executives, among the most powerful members of society, often break the law without fear of imprisonment, as we shall see in our discussion of white-collar crime later in this chapter. Finally, many studies support conflict theory’s view that the roots of crimes by poor people lie in social inequality and economic deprivation (Barkan, 2009).

Feminist Perspectives

Feminist perspectives on crime and criminal justice also fall into the broad rubric of conflict explanations and have burgeoned in the last two decades. Much of this work concerns rape and sexual assault, intimate partner violence, and other crimes against women that were largely neglected until feminists began writing about them in the 1970s (Griffin, 1971). Their views have since influenced public and official attitudes about rape and domestic violence, which used to be thought as something that girls and women brought on themselves. The feminist approach instead places the blame for these crimes squarely on society’s inequality against women and antiquated views about relations between the sexes (Renzetti, 2011).

Another focus of feminist work is gender and legal processing. Are women better or worse off than men when it comes to the chances of being arrested and punished? After many studies in the last two decades, the best answer is that we are not sure (Belknap, 2007). Women are treated a little more harshly than men for minor crimes and a little less harshly for serious crimes, but the gender effect in general is weak.

A third focus concerns the gender difference in serious crime, as women and girls are much less likely than men and boys to engage in violence and to commit serious property crimes such as burglary and motor vehicle theft. Most sociologists attribute this difference to gender socialization. Simply put, socialization into the male gender role, or masculinity, leads to values such as competitiveness and behavioral patterns such as spending more time away from home that all promote deviance. Conversely, despite whatever disadvantages it may have, socialization into the female gender role, or femininity, promotes values such as gentleness and behavior patterns such as spending more time at home that help limit deviance (Chesney-Lind & Pasko, 2004). Noting that males commit so much crime, Kathleen Daly and Meda Chesney-Lind (1988, p. 527) wrote,

A large price is paid for structures of male domination and for the very qualities that drive men to be successful, to control others, and to wield uncompromising power.…Gender differences in crime suggest that crime may not be so normal after all. Such differences challenge us to see that in the lives of women, men have a great deal more to learn.

Gender socialization helps explain why females commit less serious crime than males. Boys are raised to be competitive and aggressive, while girls are raised to be more gentle and nurturing.

Philippe Put – Fight – CC BY 2.0.

Two decades later, that challenge still remains.

Symbolic Interactionist Explanations

Because symbolic interactionism focuses on the means people gain from their social interaction, symbolic interactionist explanations attribute deviance to various aspects of the social interaction and social processes that normal individuals experience. These explanations help us understand why some people are more likely than others living in the same kinds of social environments. Several such explanations exist.

Differential Association Theory

One popular set of explanations, often called learning theories , emphasizes that deviance is learned from interacting with other people who believe it is OK to commit deviance and who often commit deviance themselves. Deviance, then, arises from normal socialization processes. The most influential such explanation is Edwin H. Sutherland’s (1947) differential association theory , which says that criminal behavior is learned by interacting with close friends and family members. These individuals teach us not only how to commit various crimes but also the values, motives, and rationalizations that we need to adopt in order to justify breaking the law. The earlier in our life that we associate with deviant individuals and the more often we do so, the more likely we become deviant ourselves. In this way, a normal social process, socialization, can lead normal people to commit deviance.

Sutherland’s theory of differential association was one of the most influential sociological theories ever. Over the years much research has documented the importance of adolescents’ peer relationships for their entrance into the world of drugs and delinquency (Akers & Sellers, 2008). However, some critics say that not all deviance results from the influences of deviant peers. Still, differential association theory and the larger category of learning theories it represents remain a valuable approach to understanding deviance and crime.

Labeling Theory

If we arrest and imprison someone, we hope they will be “scared straight,” or deterred from committing a crime again. Labeling theory assumes precisely the opposite: it says that labeling someone deviant increases the chances that the labeled person will continue to commit deviance. According to labeling theory, this happens because the labeled person ends up with a deviant self-image that leads to even more deviance. Deviance is the result of being labeled (Bohm & Vogel, 2011).

This effect is reinforced by how society treats someone who has been labeled. Research shows that job applicants with a criminal record are much less likely than those without a record to be hired (Pager, 2009). Suppose you had a criminal record and had seen the error of your ways but were rejected by several potential employers. Do you think you might be just a little frustrated? If your unemployment continues, might you think about committing a crime again? Meanwhile, you want to meet some law-abiding friends, so you go to a singles bar. You start talking with someone who interests you, and in response to this person’s question, you say you are between jobs. When your companion asks about your last job, you reply that you were in prison for armed robbery. How do you think your companion will react after hearing this? As this scenario suggests, being labeled deviant can make it difficult to avoid a continued life of deviance.

Labeling theory also asks whether some people and behaviors are indeed more likely than others to acquire a deviant label. In particular, it asserts that nonlegal factors such as appearance, race, and social class affect how often official labeling occurs.

Labeling theory assumes that someone who is labeled deviant will be more likely to commit deviance as a result. One problem that ex-prisoners face after being released back into society is that potential employers do not want to hire them. This fact makes it more likely that they will commit new offenses.

Victor – Handcuffs – CC BY 2.0.