- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research Research Tools and Apps

Action Research: What it is, Stages & Examples

The best way to get things accomplished is to do it yourself. This statement is utilized in corporations, community projects, and national governments. These organizations are relying on action research to cope with their continuously changing and unstable environments as they function in a more interdependent world.

In practical educational contexts, this involves using systematic inquiry and reflective practice to address real-world challenges, improve teaching and learning, enhance student engagement, and drive positive changes within the educational system.

This post outlines the definition of action research, its stages, and some examples.

Content Index

What is action research?

Stages of action research, the steps to conducting action research, examples of action research, advantages and disadvantages of action research.

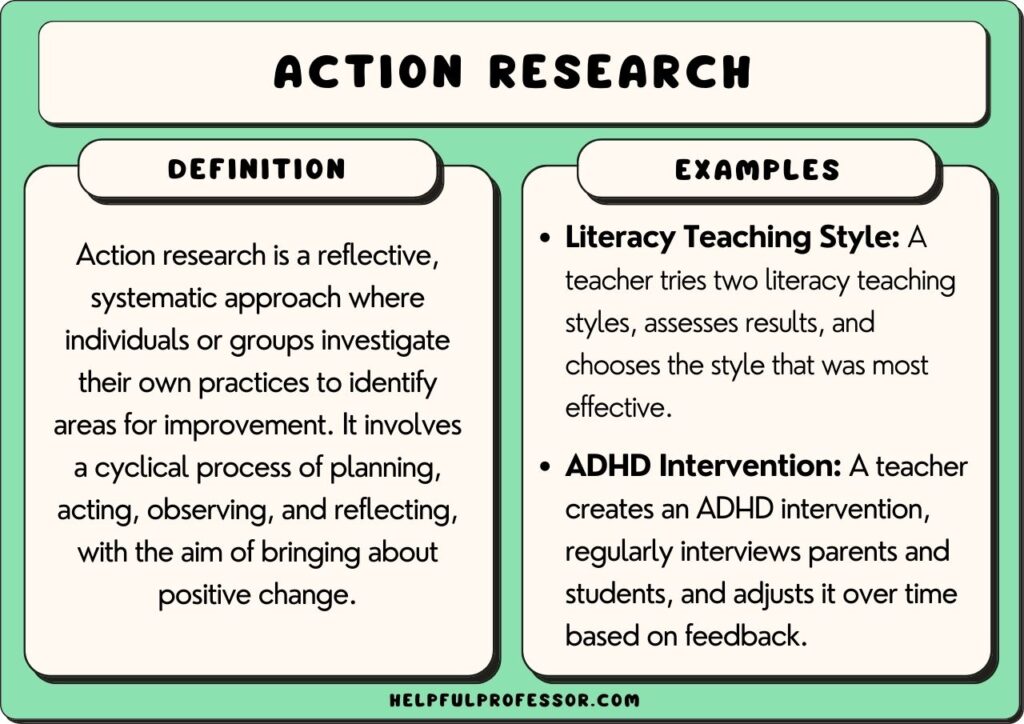

Action research is a strategy that tries to find realistic solutions to organizations’ difficulties and issues. It is similar to applied research.

Action research refers basically learning by doing. First, a problem is identified, then some actions are taken to address it, then how well the efforts worked are measured, and if the results are not satisfactory, the steps are applied again.

It can be put into three different groups:

- Positivist: This type of research is also called “classical action research.” It considers research a social experiment. This research is used to test theories in the actual world.

- Interpretive: This kind of research is called “contemporary action research.” It thinks that business reality is socially made, and when doing this research, it focuses on the details of local and organizational factors.

- Critical: This action research cycle takes a critical reflection approach to corporate systems and tries to enhance them.

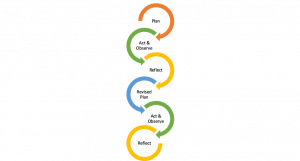

All research is about learning new things. Collaborative action research contributes knowledge based on investigations in particular and frequently useful circumstances. It starts with identifying a problem. After that, the research process is followed by the below stages:

Stage 1: Plan

For an action research project to go well, the researcher needs to plan it well. After coming up with an educational research topic or question after a research study, the first step is to develop an action plan to guide the research process. The research design aims to address the study’s question. The research strategy outlines what to undertake, when, and how.

Stage 2: Act

The next step is implementing the plan and gathering data. At this point, the researcher must select how to collect and organize research data . The researcher also needs to examine all tools and equipment before collecting data to ensure they are relevant, valid, and comprehensive.

Stage 3: Observe

Data observation is vital to any investigation. The action researcher needs to review the project’s goals and expectations before data observation. This is the final step before drawing conclusions and taking action.

Different kinds of graphs, charts, and networks can be used to represent the data. It assists in making judgments or progressing to the next stage of observing.

Stage 4: Reflect

This step involves applying a prospective solution and observing the results. It’s essential to see if the possible solution found through research can really solve the problem being studied.

The researcher must explore alternative ideas when the action research project’s solutions fail to solve the problem.

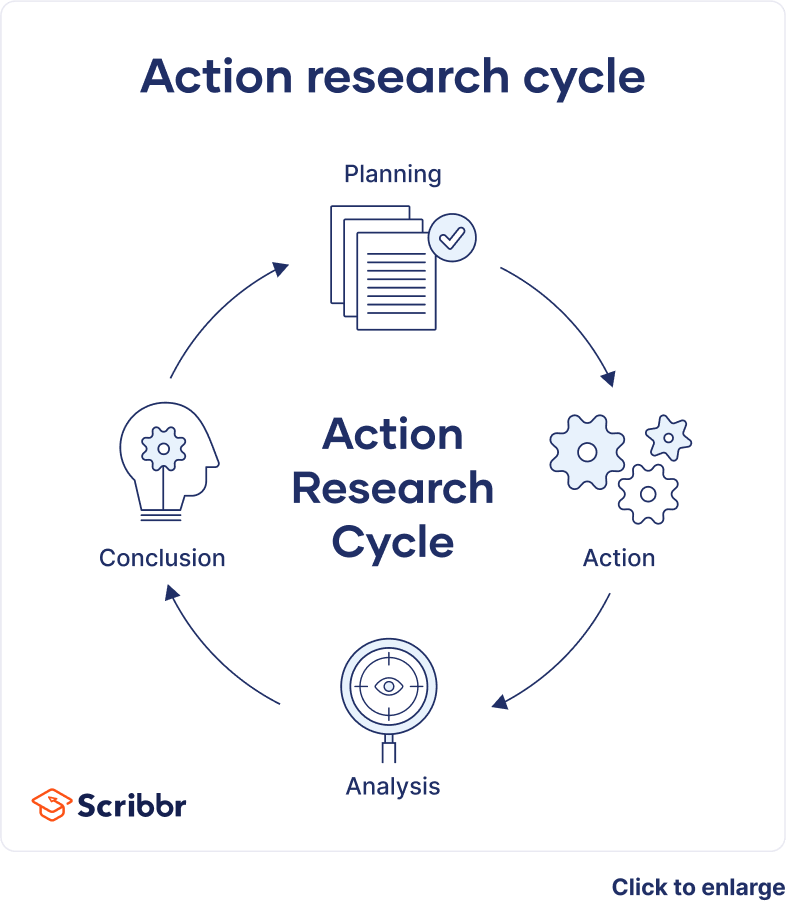

Action research is a systematic approach researchers, educators, and practitioners use to identify and address problems or challenges within a specific context. It involves a cyclical process of planning, implementing, reflecting, and adjusting actions based on the data collected. Here are the general steps involved in conducting an action research process:

Identify the action research question or problem

Clearly define the issue or problem you want to address through your research. It should be specific, actionable, and relevant to your working context.

Review existing knowledge

Conduct a literature review to understand what research has already been done on the topic. This will help you gain insights, identify gaps, and inform your research design.

Plan the research

Develop a research plan outlining your study’s objectives, methods, data collection tools, and timeline. Determine the scope of your research and the participants or stakeholders involved.

Collect data

Implement your research plan by collecting relevant data. This can involve various methods such as surveys, interviews, observations, document analysis, or focus groups. Ensure that your data collection methods align with your research objectives and allow you to gather the necessary information.

Analyze the data

Once you have collected the data, analyze it using appropriate qualitative or quantitative techniques. Look for patterns, themes, or trends in the data that can help you understand the problem better.

Reflect on the findings

Reflect on the analyzed data and interpret the results in the context of your research question. Consider the implications and possible solutions that emerge from the data analysis. This reflection phase is crucial for generating insights and understanding the underlying factors contributing to the problem.

Develop an action plan

Based on your analysis and reflection, develop an action plan that outlines the steps you will take to address the identified problem. The plan should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART goals). Consider involving relevant stakeholders in planning to ensure their buy-in and support.

Implement the action plan

Put your action plan into practice by implementing the identified strategies or interventions. This may involve making changes to existing practices, introducing new approaches, or testing alternative solutions. Document the implementation process and any modifications made along the way.

Evaluate and monitor progress

Continuously monitor and evaluate the impact of your actions. Collect additional data, assess the effectiveness of the interventions, and measure progress towards your goals. This evaluation will help you determine if your actions have the desired effects and inform any necessary adjustments.

Reflect and iterate

Reflect on the outcomes of your actions and the evaluation results. Consider what worked well, what did not, and why. Use this information to refine your approach, make necessary adjustments, and plan for the next cycle of action research if needed.

Remember that participatory action research is an iterative process, and multiple cycles may be required to achieve significant improvements or solutions to the identified problem. Each cycle builds on the insights gained from the previous one, fostering continuous learning and improvement.

Explore Insightfully Contextual Inquiry in Qualitative Research

Here are two real-life examples of action research.

Action research initiatives are frequently situation-specific. Still, other researchers can adapt the techniques. The example is from a researcher’s (Franklin, 1994) report about a project encouraging nature tourism in the Caribbean.

In 1991, this was launched to study how nature tourism may be implemented on the four Windward Islands in the Caribbean: St. Lucia, Grenada, Dominica, and St. Vincent.

For environmental protection, a government-led action study determined that the consultation process needs to involve numerous stakeholders, including commercial enterprises.

First, two researchers undertook the study and held search conferences on each island. The search conferences resulted in suggestions and action plans for local community nature tourism sub-projects.

Several islands formed advisory groups and launched national awareness and community projects. Regional project meetings were held to discuss experiences, self-evaluations, and strategies. Creating a documentary about a local initiative helped build community. And the study was a success, leading to a number of changes in the area.

Lau and Hayward (1997) employed action research to analyze Internet-based collaborative work groups.

Over two years, the researchers facilitated three action research problem -solving cycles with 15 teachers, project personnel, and 25 health practitioners from diverse areas. The goal was to see how Internet-based communications might affect their virtual workgroup.

First, expectations were defined, technology was provided, and a bespoke workgroup system was developed. Participants suggested shorter, more dispersed training sessions with project-specific instructions.

The second phase saw the system’s complete deployment. The final cycle witnessed system stability and virtual group formation. The key lesson was that the learning curve was poorly misjudged, with frustrations only marginally met by phone-based technical help. According to the researchers, the absence of high-quality online material about community healthcare was harmful.

Role clarity, connection building, knowledge sharing, resource assistance, and experiential learning are vital for virtual group growth. More study is required on how group support systems might assist groups in engaging with their external environment and boost group members’ learning.

Action research has both good and bad points.

- It is very flexible, so researchers can change their analyses to fit their needs and make individual changes.

- It offers a quick and easy way to solve problems that have been going on for a long time instead of complicated, long-term solutions based on complex facts.

- If It is done right, it can be very powerful because it can lead to social change and give people the tools to make that change in ways that are important to their communities.

Disadvantages

- These studies have a hard time being generalized and are hard to repeat because they are so flexible. Because the researcher has the power to draw conclusions, they are often not thought to be theoretically sound.

- Setting up an action study in an ethical way can be hard. People may feel like they have to take part or take part in a certain way.

- It is prone to research errors like selection bias , social desirability bias, and other cognitive biases.

LEARN ABOUT: Self-Selection Bias

This post discusses how action research generates knowledge, its steps, and real-life examples. It is very applicable to the field of research and has a high level of relevance. We can only state that the purpose of this research is to comprehend an issue and find a solution to it.

At QuestionPro, we give researchers tools for collecting data, like our survey software, and a library of insights for any long-term study. Go to the Insight Hub if you want to see a demo or learn more about it.

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

Frequently Asked Questions(FAQ’s)

Action research is a systematic approach to inquiry that involves identifying a problem or challenge in a practical context, implementing interventions or changes, collecting and analyzing data, and using the findings to inform decision-making and drive positive change.

Action research can be conducted by various individuals or groups, including teachers, administrators, researchers, and educational practitioners. It is often carried out by those directly involved in the educational setting where the research takes place.

The steps of action research typically include identifying a problem, reviewing relevant literature, designing interventions or changes, collecting and analyzing data, reflecting on findings, and implementing improvements based on the results.

MORE LIKE THIS

17 Best VOC Software for Customer Experience in 2024

Mar 28, 2024

CEM Software: What it is, 7 Best CEM Software in 2024

Resident Experience: What It Is and How to Improve It

Mar 27, 2024

11 Best Employee Onboarding and Training Software in 2024

Other categories.

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

How to Write a Conclusion for Research Papers (with Examples)

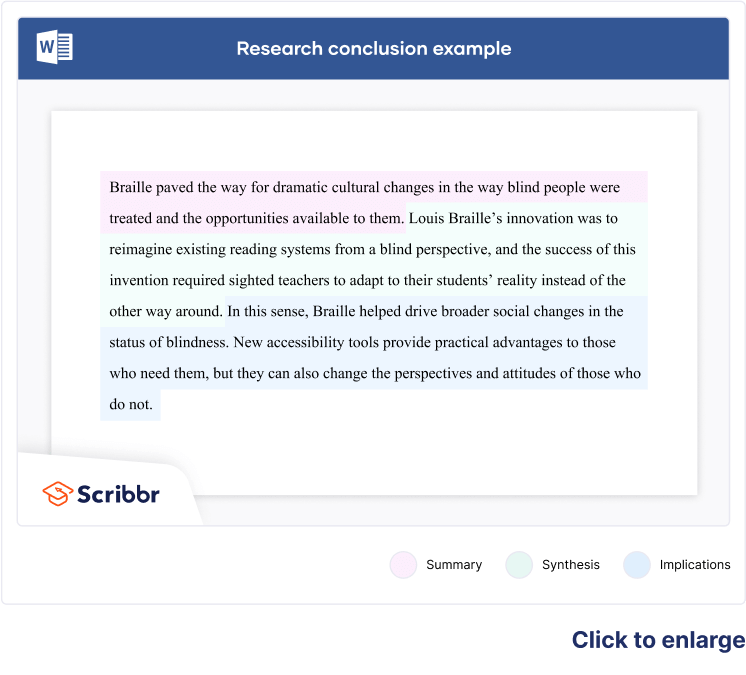

The conclusion of a research paper is a crucial section that plays a significant role in the overall impact and effectiveness of your research paper. However, this is also the section that typically receives less attention compared to the introduction and the body of the paper. The conclusion serves to provide a concise summary of the key findings, their significance, their implications, and a sense of closure to the study. Discussing how can the findings be applied in real-world scenarios or inform policy, practice, or decision-making is especially valuable to practitioners and policymakers. The research paper conclusion also provides researchers with clear insights and valuable information for their own work, which they can then build on and contribute to the advancement of knowledge in the field.

The research paper conclusion should explain the significance of your findings within the broader context of your field. It restates how your results contribute to the existing body of knowledge and whether they confirm or challenge existing theories or hypotheses. Also, by identifying unanswered questions or areas requiring further investigation, your awareness of the broader research landscape can be demonstrated.

Remember to tailor the research paper conclusion to the specific needs and interests of your intended audience, which may include researchers, practitioners, policymakers, or a combination of these.

Table of Contents

What is a conclusion in a research paper, summarizing conclusion, editorial conclusion, externalizing conclusion, importance of a good research paper conclusion, how to write a conclusion for your research paper, research paper conclusion examples.

- How to write a research paper conclusion with Paperpal?

Frequently Asked Questions

A conclusion in a research paper is the final section where you summarize and wrap up your research, presenting the key findings and insights derived from your study. The research paper conclusion is not the place to introduce new information or data that was not discussed in the main body of the paper. When working on how to conclude a research paper, remember to stick to summarizing and interpreting existing content. The research paper conclusion serves the following purposes: 1

- Warn readers of the possible consequences of not attending to the problem.

- Recommend specific course(s) of action.

- Restate key ideas to drive home the ultimate point of your research paper.

- Provide a “take-home” message that you want the readers to remember about your study.

Types of conclusions for research papers

In research papers, the conclusion provides closure to the reader. The type of research paper conclusion you choose depends on the nature of your study, your goals, and your target audience. I provide you with three common types of conclusions:

A summarizing conclusion is the most common type of conclusion in research papers. It involves summarizing the main points, reiterating the research question, and restating the significance of the findings. This common type of research paper conclusion is used across different disciplines.

An editorial conclusion is less common but can be used in research papers that are focused on proposing or advocating for a particular viewpoint or policy. It involves presenting a strong editorial or opinion based on the research findings and offering recommendations or calls to action.

An externalizing conclusion is a type of conclusion that extends the research beyond the scope of the paper by suggesting potential future research directions or discussing the broader implications of the findings. This type of conclusion is often used in more theoretical or exploratory research papers.

Align your conclusion’s tone with the rest of your research paper. Start Writing with Paperpal Now!

The conclusion in a research paper serves several important purposes:

- Offers Implications and Recommendations : Your research paper conclusion is an excellent place to discuss the broader implications of your research and suggest potential areas for further study. It’s also an opportunity to offer practical recommendations based on your findings.

- Provides Closure : A good research paper conclusion provides a sense of closure to your paper. It should leave the reader with a feeling that they have reached the end of a well-structured and thought-provoking research project.

- Leaves a Lasting Impression : Writing a well-crafted research paper conclusion leaves a lasting impression on your readers. It’s your final opportunity to leave them with a new idea, a call to action, or a memorable quote.

Writing a strong conclusion for your research paper is essential to leave a lasting impression on your readers. Here’s a step-by-step process to help you create and know what to put in the conclusion of a research paper: 2

- Research Statement : Begin your research paper conclusion by restating your research statement. This reminds the reader of the main point you’ve been trying to prove throughout your paper. Keep it concise and clear.

- Key Points : Summarize the main arguments and key points you’ve made in your paper. Avoid introducing new information in the research paper conclusion. Instead, provide a concise overview of what you’ve discussed in the body of your paper.

- Address the Research Questions : If your research paper is based on specific research questions or hypotheses, briefly address whether you’ve answered them or achieved your research goals. Discuss the significance of your findings in this context.

- Significance : Highlight the importance of your research and its relevance in the broader context. Explain why your findings matter and how they contribute to the existing knowledge in your field.

- Implications : Explore the practical or theoretical implications of your research. How might your findings impact future research, policy, or real-world applications? Consider the “so what?” question.

- Future Research : Offer suggestions for future research in your area. What questions or aspects remain unanswered or warrant further investigation? This shows that your work opens the door for future exploration.

- Closing Thought : Conclude your research paper conclusion with a thought-provoking or memorable statement. This can leave a lasting impression on your readers and wrap up your paper effectively. Avoid introducing new information or arguments here.

- Proofread and Revise : Carefully proofread your conclusion for grammar, spelling, and clarity. Ensure that your ideas flow smoothly and that your conclusion is coherent and well-structured.

Write your research paper conclusion 2x faster with Paperpal. Try it now!

Remember that a well-crafted research paper conclusion is a reflection of the strength of your research and your ability to communicate its significance effectively. It should leave a lasting impression on your readers and tie together all the threads of your paper. Now you know how to start the conclusion of a research paper and what elements to include to make it impactful, let’s look at a research paper conclusion sample.

How to write a research paper conclusion with Paperpal?

A research paper conclusion is not just a summary of your study, but a synthesis of the key findings that ties the research together and places it in a broader context. A research paper conclusion should be concise, typically around one paragraph in length. However, some complex topics may require a longer conclusion to ensure the reader is left with a clear understanding of the study’s significance. Paperpal, an AI writing assistant trusted by over 800,000 academics globally, can help you write a well-structured conclusion for your research paper.

- Sign Up or Log In: Create a new Paperpal account or login with your details.

- Navigate to Features : Once logged in, head over to the features’ side navigation pane. Click on Templates and you’ll find a suite of generative AI features to help you write better, faster.

- Generate an outline: Under Templates, select ‘Outlines’. Choose ‘Research article’ as your document type.

- Select your section: Since you’re focusing on the conclusion, select this section when prompted.

- Choose your field of study: Identifying your field of study allows Paperpal to provide more targeted suggestions, ensuring the relevance of your conclusion to your specific area of research.

- Provide a brief description of your study: Enter details about your research topic and findings. This information helps Paperpal generate a tailored outline that aligns with your paper’s content.

- Generate the conclusion outline: After entering all necessary details, click on ‘generate’. Paperpal will then create a structured outline for your conclusion, to help you start writing and build upon the outline.

- Write your conclusion: Use the generated outline to build your conclusion. The outline serves as a guide, ensuring you cover all critical aspects of a strong conclusion, from summarizing key findings to highlighting the research’s implications.

- Refine and enhance: Paperpal’s ‘Make Academic’ feature can be particularly useful in the final stages. Select any paragraph of your conclusion and use this feature to elevate the academic tone, ensuring your writing is aligned to the academic journal standards.

By following these steps, Paperpal not only simplifies the process of writing a research paper conclusion but also ensures it is impactful, concise, and aligned with academic standards. Sign up with Paperpal today and write your research paper conclusion 2x faster .

The research paper conclusion is a crucial part of your paper as it provides the final opportunity to leave a strong impression on your readers. In the research paper conclusion, summarize the main points of your research paper by restating your research statement, highlighting the most important findings, addressing the research questions or objectives, explaining the broader context of the study, discussing the significance of your findings, providing recommendations if applicable, and emphasizing the takeaway message. The main purpose of the conclusion is to remind the reader of the main point or argument of your paper and to provide a clear and concise summary of the key findings and their implications. All these elements should feature on your list of what to put in the conclusion of a research paper to create a strong final statement for your work.

A strong conclusion is a critical component of a research paper, as it provides an opportunity to wrap up your arguments, reiterate your main points, and leave a lasting impression on your readers. Here are the key elements of a strong research paper conclusion: 1. Conciseness : A research paper conclusion should be concise and to the point. It should not introduce new information or ideas that were not discussed in the body of the paper. 2. Summarization : The research paper conclusion should be comprehensive enough to give the reader a clear understanding of the research’s main contributions. 3 . Relevance : Ensure that the information included in the research paper conclusion is directly relevant to the research paper’s main topic and objectives; avoid unnecessary details. 4 . Connection to the Introduction : A well-structured research paper conclusion often revisits the key points made in the introduction and shows how the research has addressed the initial questions or objectives. 5. Emphasis : Highlight the significance and implications of your research. Why is your study important? What are the broader implications or applications of your findings? 6 . Call to Action : Include a call to action or a recommendation for future research or action based on your findings.

The length of a research paper conclusion can vary depending on several factors, including the overall length of the paper, the complexity of the research, and the specific journal requirements. While there is no strict rule for the length of a conclusion, but it’s generally advisable to keep it relatively short. A typical research paper conclusion might be around 5-10% of the paper’s total length. For example, if your paper is 10 pages long, the conclusion might be roughly half a page to one page in length.

In general, you do not need to include citations in the research paper conclusion. Citations are typically reserved for the body of the paper to support your arguments and provide evidence for your claims. However, there may be some exceptions to this rule: 1. If you are drawing a direct quote or paraphrasing a specific source in your research paper conclusion, you should include a citation to give proper credit to the original author. 2. If your conclusion refers to or discusses specific research, data, or sources that are crucial to the overall argument, citations can be included to reinforce your conclusion’s validity.

The conclusion of a research paper serves several important purposes: 1. Summarize the Key Points 2. Reinforce the Main Argument 3. Provide Closure 4. Offer Insights or Implications 5. Engage the Reader. 6. Reflect on Limitations

Remember that the primary purpose of the research paper conclusion is to leave a lasting impression on the reader, reinforcing the key points and providing closure to your research. It’s often the last part of the paper that the reader will see, so it should be strong and well-crafted.

- Makar, G., Foltz, C., Lendner, M., & Vaccaro, A. R. (2018). How to write effective discussion and conclusion sections. Clinical spine surgery, 31(8), 345-346.

- Bunton, D. (2005). The structure of PhD conclusion chapters. Journal of English for academic purposes , 4 (3), 207-224.

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- 5 Reasons for Rejection After Peer Review

- Ethical Research Practices For Research with Human Subjects

7 Ways to Improve Your Academic Writing Process

- Paraphrasing in Academic Writing: Answering Top Author Queries

Preflight For Editorial Desk: The Perfect Hybrid (AI + Human) Assistance Against Compromised Manuscripts

You may also like, what are journal guidelines on using generative ai..., quillbot review: features, pricing, and free alternatives, what is an academic paper types and elements , should you use ai tools like chatgpt for..., publish research papers: 9 steps for successful publications , what are the different types of research papers, how to make translating academic papers less challenging, self-plagiarism in research: what it is and how..., 6 tips for post-doc researchers to take their..., presenting research data effectively through tables and figures.

education, community-building and change

What is action research and how do we do it?

In this article, we explore the development of some different traditions of action research and provide an introductory guide to the literature.

Contents : what is action research · origins · the decline and rediscovery of action research · undertaking action research · conclusion · further reading · how to cite this article . see, also: research for practice ., what is action research.

In the literature, discussion of action research tends to fall into two distinctive camps. The British tradition – especially that linked to education – tends to view action research as research-oriented toward the enhancement of direct practice. For example, Carr and Kemmis provide a classic definition:

Action research is simply a form of self-reflective enquiry undertaken by participants in social situations in order to improve the rationality and justice of their own practices, their understanding of these practices, and the situations in which the practices are carried out (Carr and Kemmis 1986: 162).

Many people are drawn to this understanding of action research because it is firmly located in the realm of the practitioner – it is tied to self-reflection. As a way of working it is very close to the notion of reflective practice coined by Donald Schön (1983).

The second tradition, perhaps more widely approached within the social welfare field – and most certainly the broader understanding in the USA is of action research as ‘the systematic collection of information that is designed to bring about social change’ (Bogdan and Biklen 1992: 223). Bogdan and Biklen continue by saying that its practitioners marshal evidence or data to expose unjust practices or environmental dangers and recommend actions for change. In many respects, for them, it is linked into traditions of citizen’s action and community organizing. The practitioner is actively involved in the cause for which the research is conducted. For others, it is such commitment is a necessary part of being a practitioner or member of a community of practice. Thus, various projects designed to enhance practice within youth work, for example, such as the detached work reported on by Goetschius and Tash (1967) could be talked of as action research.

Kurt Lewin is generally credited as the person who coined the term ‘action research’:

The research needed for social practice can best be characterized as research for social management or social engineering. It is a type of action-research, a comparative research on the conditions and effects of various forms of social action, and research leading to social action. Research that produces nothing but books will not suffice (Lewin 1946, reproduced in Lewin 1948: 202-3)

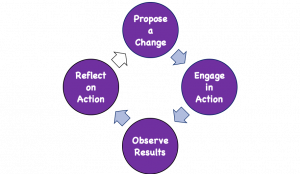

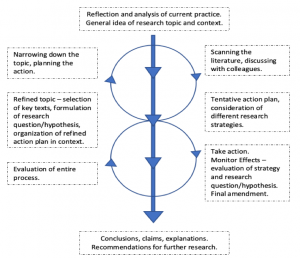

His approach involves a spiral of steps, ‘each of which is composed of a circle of planning, action and fact-finding about the result of the action’ ( ibid. : 206). The basic cycle involves the following:

This is how Lewin describes the initial cycle:

The first step then is to examine the idea carefully in the light of the means available. Frequently more fact-finding about the situation is required. If this first period of planning is successful, two items emerge: namely, “an overall plan” of how to reach the objective and secondly, a decision in regard to the first step of action. Usually this planning has also somewhat modified the original idea. ( ibid. : 205)

The next step is ‘composed of a circle of planning, executing, and reconnaissance or fact-finding for the purpose of evaluating the results of the second step, and preparing the rational basis for planning the third step, and for perhaps modifying again the overall plan’ ( ibid. : 206). What we can see here is an approach to research that is oriented to problem-solving in social and organizational settings, and that has a form that parallels Dewey’s conception of learning from experience.

The approach, as presented, does take a fairly sequential form – and it is open to a literal interpretation. Following it can lead to practice that is ‘correct’ rather than ‘good’ – as we will see. It can also be argued that the model itself places insufficient emphasis on analysis at key points. Elliott (1991: 70), for example, believed that the basic model allows those who use it to assume that the ‘general idea’ can be fixed in advance, ‘that “reconnaissance” is merely fact-finding, and that “implementation” is a fairly straightforward process’. As might be expected there was some questioning as to whether this was ‘real’ research. There were questions around action research’s partisan nature – the fact that it served particular causes.

The decline and rediscovery of action research

Action research did suffer a decline in favour during the 1960s because of its association with radical political activism (Stringer 2007: 9). There were, and are, questions concerning its rigour, and the training of those undertaking it. However, as Bogdan and Biklen (1992: 223) point out, research is a frame of mind – ‘a perspective that people take toward objects and activities’. Once we have satisfied ourselves that the collection of information is systematic and that any interpretations made have a proper regard for satisfying truth claims, then much of the critique aimed at action research disappears. In some of Lewin’s earlier work on action research (e.g. Lewin and Grabbe 1945), there was a tension between providing a rational basis for change through research, and the recognition that individuals are constrained in their ability to change by their cultural and social perceptions, and the systems of which they are a part. Having ‘correct knowledge’ does not of itself lead to change, attention also needs to be paid to the ‘matrix of cultural and psychic forces’ through which the subject is constituted (Winter 1987: 48).

Subsequently, action research has gained a significant foothold both within the realm of community-based, and participatory action research; and as a form of practice-oriented to the improvement of educative encounters (e.g. Carr and Kemmis 1986).

Exhibit 1: Stringer on community-based action research

A fundamental premise of community-based action research is that it commences with an interest in the problems of a group, a community, or an organization. Its purpose is to assist people in extending their understanding of their situation and thus resolving problems that confront them….

Community-based action research is always enacted through an explicit set of social values. In modern, democratic social contexts, it is seen as a process of inquiry that has the following characteristics:

• It is democratic , enabling the participation of all people.

• It is equitable , acknowledging people’s equality of worth.

• It is liberating , providing freedom from oppressive, debilitating conditions.

• It is life enhancing , enabling the expression of people’s full human potential.

(Stringer 1999: 9-10)

Undertaking action research

As Thomas (2017: 154) put it, the central aim is change, ‘and the emphasis is on problem-solving in whatever way is appropriate’. It can be seen as a conversation rather more than a technique (McNiff et. al. ). It is about people ‘thinking for themselves and making their own choices, asking themselves what they should do and accepting the consequences of their own actions’ (Thomas 2009: 113).

The action research process works through three basic phases:

Look -building a picture and gathering information. When evaluating we define and describe the problem to be investigated and the context in which it is set. We also describe what all the participants (educators, group members, managers etc.) have been doing.

Think – interpreting and explaining. When evaluating we analyse and interpret the situation. We reflect on what participants have been doing. We look at areas of success and any deficiencies, issues or problems.

Act – resolving issues and problems. In evaluation we judge the worth, effectiveness, appropriateness, and outcomes of those activities. We act to formulate solutions to any problems. (Stringer 1999: 18; 43-44;160)

The use of action research to deepen and develop classroom practice has grown into a strong tradition of practice (one of the first examples being the work of Stephen Corey in 1949). For some, there is an insistence that action research must be collaborative and entail groupwork.

Action research is a form of collective self-reflective enquiry undertaken by participants in social situations in order to improve the rationality and justice of their own social or educational practices, as well as their understanding of those practices and the situations in which the practices are carried out… The approach is only action research when it is collaborative, though it is important to realise that action research of the group is achieved through the critically examined action of individual group members. (Kemmis and McTaggart 1988: 5-6)

Just why it must be collective is open to some question and debate (Webb 1996), but there is an important point here concerning the commitments and orientations of those involved in action research.

One of the legacies Kurt Lewin left us is the ‘action research spiral’ – and with it there is the danger that action research becomes little more than a procedure. It is a mistake, according to McTaggart (1996: 248) to think that following the action research spiral constitutes ‘doing action research’. He continues, ‘Action research is not a ‘method’ or a ‘procedure’ for research but a series of commitments to observe and problematize through practice a series of principles for conducting social enquiry’. It is his argument that Lewin has been misunderstood or, rather, misused. When set in historical context, while Lewin does talk about action research as a method, he is stressing a contrast between this form of interpretative practice and more traditional empirical-analytic research. The notion of a spiral may be a useful teaching device – but it is all too easy to slip into using it as the template for practice (McTaggart 1996: 249).

Further reading

This select, annotated bibliography has been designed to give a flavour of the possibilities of action research and includes some useful guides to practice. As ever, if you have suggestions about areas or specific texts for inclusion, I’d like to hear from you.

Explorations of action research

Atweh, B., Kemmis, S. and Weeks, P. (eds.) (1998) Action Research in Practice: Partnership for Social Justice in Education, London: Routledge. Presents a collection of stories from action research projects in schools and a university. The book begins with theme chapters discussing action research, social justice and partnerships in research. The case study chapters cover topics such as: school environment – how to make a school a healthier place to be; parents – how to involve them more in decision-making; students as action researchers; gender – how to promote gender equity in schools; writing up action research projects.

Carr, W. and Kemmis, S. (1986) Becoming Critical. Education, knowledge and action research , Lewes: Falmer. Influential book that provides a good account of ‘action research’ in education. Chapters on teachers, researchers and curriculum; the natural scientific view of educational theory and practice; the interpretative view of educational theory and practice; theory and practice – redefining the problem; a critical approach to theory and practice; towards a critical educational science; action research as critical education science; educational research, educational reform and the role of the profession.

Carson, T. R. and Sumara, D. J. (ed.) (1997) Action Research as a Living Practice , New York: Peter Lang. 140 pages. Book draws on a wide range of sources to develop an understanding of action research. Explores action research as a lived practice, ‘that asks the researcher to not only investigate the subject at hand but, as well, to provide some account of the way in which the investigation both shapes and is shaped by the investigator.

Dadds, M. (1995) Passionate Enquiry and School Development. A story about action research , London: Falmer. 192 + ix pages. Examines three action research studies undertaken by a teacher and how they related to work in school – how she did the research, the problems she experienced, her feelings, the impact on her feelings and ideas, and some of the outcomes. In his introduction, John Elliot comments that the book is ‘the most readable, thoughtful, and detailed study of the potential of action-research in professional education that I have read’.

Ghaye, T. and Wakefield, P. (eds.) CARN Critical Conversations. Book one: the role of the self in action , Bournemouth: Hyde Publications. 146 + xiii pages. Collection of five pieces from the Classroom Action Research Network. Chapters on: dialectical forms; graduate medical education – research’s outer limits; democratic education; managing action research; writing up.

McNiff, J. (1993) Teaching as Learning: An Action Research Approach , London: Routledge. Argues that educational knowledge is created by individual teachers as they attempt to express their own values in their professional lives. Sets out familiar action research model: identifying a problem, devising, implementing and evaluating a solution and modifying practice. Includes advice on how working in this way can aid the professional development of action researcher and practitioner.

Quigley, B. A. and Kuhne, G. W. (eds.) (1997) Creating Practical Knowledge Through Action Research, San Fransisco: Jossey Bass. Guide to action research that outlines the action research process, provides a project planner, and presents examples to show how action research can yield improvements in six different settings, including a hospital, a university and a literacy education program.

Plummer, G. and Edwards, G. (eds.) CARN Critical Conversations. Book two: dimensions of action research – people, practice and power , Bournemouth: Hyde Publications. 142 + xvii pages. Collection of five pieces from the Classroom Action Research Network. Chapters on: exchanging letters and collaborative research; diary writing; personal and professional learning – on teaching and self-knowledge; anti-racist approaches; psychodynamic group theory in action research.

Whyte, W. F. (ed.) (1991) Participatory Action Research , Newbury Park: Sage. 247 pages. Chapters explore the development of participatory action research and its relation with action science and examine its usages in various agricultural and industrial settings

Zuber-Skerritt, O. (ed.) (1996) New Directions in Action Research , London; Falmer Press. 266 + xii pages. A useful collection that explores principles and procedures for critical action research; problems and suggested solutions; and postmodernism and critical action research.

Action research guides

Coghlan, D. and Brannick, D. (2000) Doing Action Research in your own Organization, London: Sage. 128 pages. Popular introduction. Part one covers the basics of action research including the action research cycle, the role of the ‘insider’ action researcher and the complexities of undertaking action research within your own organisation. Part two looks at the implementation of the action research project (including managing internal politics and the ethics and politics of action research). New edition due late 2004.

Elliot, J. (1991) Action Research for Educational Change , Buckingham: Open University Press. 163 + x pages Collection of various articles written by Elliot in which he develops his own particular interpretation of action research as a form of teacher professional development. In some ways close to a form of ‘reflective practice’. Chapter 6, ‘A practical guide to action research’ – builds a staged model on Lewin’s work and on developments by writers such as Kemmis.

Johnson, A. P. (2007) A short guide to action research 3e. Allyn and Bacon. Popular step by step guide for master’s work.

Macintyre, C. (2002) The Art of the Action Research in the Classroom , London: David Fulton. 138 pages. Includes sections on action research, the role of literature, formulating a research question, gathering data, analysing data and writing a dissertation. Useful and readable guide for students.

McNiff, J., Whitehead, J., Lomax, P. (2003) You and Your Action Research Project , London: Routledge. Practical guidance on doing an action research project.Takes the practitioner-researcher through the various stages of a project. Each section of the book is supported by case studies

Stringer, E. T. (2007) Action Research: A handbook for practitioners 3e , Newbury Park, ca.: Sage. 304 pages. Sets community-based action research in context and develops a model. Chapters on information gathering, interpretation, resolving issues; legitimacy etc. See, also Stringer’s (2003) Action Research in Education , Prentice-Hall.

Winter, R. (1989) Learning From Experience. Principles and practice in action research , Lewes: Falmer Press. 200 + 10 pages. Introduces the idea of action research; the basic process; theoretical issues; and provides six principles for the conduct of action research. Includes examples of action research. Further chapters on from principles to practice; the learner’s experience; and research topics and personal interests.

Action research in informal education

Usher, R., Bryant, I. and Johnston, R. (1997) Adult Education and the Postmodern Challenge. Learning beyond the limits , London: Routledge. 248 + xvi pages. Has some interesting chapters that relate to action research: on reflective practice; changing paradigms and traditions of research; new approaches to research; writing and learning about research.

Other references

Bogdan, R. and Biklen, S. K. (1992) Qualitative Research For Education , Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Goetschius, G. and Tash, J. (1967) Working with the Unattached , London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

McTaggart, R. (1996) ‘Issues for participatory action researchers’ in O. Zuber-Skerritt (ed.) New Directions in Action Research , London: Falmer Press.

McNiff, J., Lomax, P. and Whitehead, J. (2003) You and Your Action Research Project 2e. London: Routledge.

Thomas, G. (2017). How to do your Research Project. A guide for students in education and applied social sciences . 3e. London: Sage.

Acknowledgements : spiral by Michèle C. | flickr ccbyncnd2 licence

How to cite this article : Smith, M. K. (1996; 2001, 2007, 2017) What is action research and how do we do it?’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [ https://infed.org/mobi/action-research/ . Retrieved: insert date] .

© Mark K. Smith 1996; 2001, 2007, 2017

Last Updated on December 7, 2020 by infed.org

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research paper

Writing a Research Paper Conclusion | Step-by-Step Guide

Published on October 30, 2022 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on April 13, 2023.

- Restate the problem statement addressed in the paper

- Summarize your overall arguments or findings

- Suggest the key takeaways from your paper

The content of the conclusion varies depending on whether your paper presents the results of original empirical research or constructs an argument through engagement with sources .

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Step 1: restate the problem, step 2: sum up the paper, step 3: discuss the implications, research paper conclusion examples, frequently asked questions about research paper conclusions.

The first task of your conclusion is to remind the reader of your research problem . You will have discussed this problem in depth throughout the body, but now the point is to zoom back out from the details to the bigger picture.

While you are restating a problem you’ve already introduced, you should avoid phrasing it identically to how it appeared in the introduction . Ideally, you’ll find a novel way to circle back to the problem from the more detailed ideas discussed in the body.

For example, an argumentative paper advocating new measures to reduce the environmental impact of agriculture might restate its problem as follows:

Meanwhile, an empirical paper studying the relationship of Instagram use with body image issues might present its problem like this:

“In conclusion …”

Avoid starting your conclusion with phrases like “In conclusion” or “To conclude,” as this can come across as too obvious and make your writing seem unsophisticated. The content and placement of your conclusion should make its function clear without the need for additional signposting.

Scribbr Citation Checker New

The AI-powered Citation Checker helps you avoid common mistakes such as:

- Missing commas and periods

- Incorrect usage of “et al.”

- Ampersands (&) in narrative citations

- Missing reference entries

Having zoomed back in on the problem, it’s time to summarize how the body of the paper went about addressing it, and what conclusions this approach led to.

Depending on the nature of your research paper, this might mean restating your thesis and arguments, or summarizing your overall findings.

Argumentative paper: Restate your thesis and arguments

In an argumentative paper, you will have presented a thesis statement in your introduction, expressing the overall claim your paper argues for. In the conclusion, you should restate the thesis and show how it has been developed through the body of the paper.

Briefly summarize the key arguments made in the body, showing how each of them contributes to proving your thesis. You may also mention any counterarguments you addressed, emphasizing why your thesis holds up against them, particularly if your argument is a controversial one.

Don’t go into the details of your evidence or present new ideas; focus on outlining in broad strokes the argument you have made.

Empirical paper: Summarize your findings

In an empirical paper, this is the time to summarize your key findings. Don’t go into great detail here (you will have presented your in-depth results and discussion already), but do clearly express the answers to the research questions you investigated.

Describe your main findings, even if they weren’t necessarily the ones you expected or hoped for, and explain the overall conclusion they led you to.

Having summed up your key arguments or findings, the conclusion ends by considering the broader implications of your research. This means expressing the key takeaways, practical or theoretical, from your paper—often in the form of a call for action or suggestions for future research.

Argumentative paper: Strong closing statement

An argumentative paper generally ends with a strong closing statement. In the case of a practical argument, make a call for action: What actions do you think should be taken by the people or organizations concerned in response to your argument?

If your topic is more theoretical and unsuitable for a call for action, your closing statement should express the significance of your argument—for example, in proposing a new understanding of a topic or laying the groundwork for future research.

Empirical paper: Future research directions

In a more empirical paper, you can close by either making recommendations for practice (for example, in clinical or policy papers), or suggesting directions for future research.

Whatever the scope of your own research, there will always be room for further investigation of related topics, and you’ll often discover new questions and problems during the research process .

Finish your paper on a forward-looking note by suggesting how you or other researchers might build on this topic in the future and address any limitations of the current paper.

Full examples of research paper conclusions are shown in the tabs below: one for an argumentative paper, the other for an empirical paper.

- Argumentative paper

- Empirical paper

While the role of cattle in climate change is by now common knowledge, countries like the Netherlands continually fail to confront this issue with the urgency it deserves. The evidence is clear: To create a truly futureproof agricultural sector, Dutch farmers must be incentivized to transition from livestock farming to sustainable vegetable farming. As well as dramatically lowering emissions, plant-based agriculture, if approached in the right way, can produce more food with less land, providing opportunities for nature regeneration areas that will themselves contribute to climate targets. Although this approach would have economic ramifications, from a long-term perspective, it would represent a significant step towards a more sustainable and resilient national economy. Transitioning to sustainable vegetable farming will make the Netherlands greener and healthier, setting an example for other European governments. Farmers, policymakers, and consumers must focus on the future, not just on their own short-term interests, and work to implement this transition now.

As social media becomes increasingly central to young people’s everyday lives, it is important to understand how different platforms affect their developing self-conception. By testing the effect of daily Instagram use among teenage girls, this study established that highly visual social media does indeed have a significant effect on body image concerns, with a strong correlation between the amount of time spent on the platform and participants’ self-reported dissatisfaction with their appearance. However, the strength of this effect was moderated by pre-test self-esteem ratings: Participants with higher self-esteem were less likely to experience an increase in body image concerns after using Instagram. This suggests that, while Instagram does impact body image, it is also important to consider the wider social and psychological context in which this usage occurs: Teenagers who are already predisposed to self-esteem issues may be at greater risk of experiencing negative effects. Future research into Instagram and other highly visual social media should focus on establishing a clearer picture of how self-esteem and related constructs influence young people’s experiences of these platforms. Furthermore, while this experiment measured Instagram usage in terms of time spent on the platform, observational studies are required to gain more insight into different patterns of usage—to investigate, for instance, whether active posting is associated with different effects than passive consumption of social media content.

If you’re unsure about the conclusion, it can be helpful to ask a friend or fellow student to read your conclusion and summarize the main takeaways.

- Do they understand from your conclusion what your research was about?

- Are they able to summarize the implications of your findings?

- Can they answer your research question based on your conclusion?

You can also get an expert to proofread and feedback your paper with a paper editing service .

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

The conclusion of a research paper has several key elements you should make sure to include:

- A restatement of the research problem

- A summary of your key arguments and/or findings

- A short discussion of the implications of your research

No, it’s not appropriate to present new arguments or evidence in the conclusion . While you might be tempted to save a striking argument for last, research papers follow a more formal structure than this.

All your findings and arguments should be presented in the body of the text (more specifically in the results and discussion sections if you are following a scientific structure). The conclusion is meant to summarize and reflect on the evidence and arguments you have already presented, not introduce new ones.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, April 13). Writing a Research Paper Conclusion | Step-by-Step Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved March 26, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-paper/research-paper-conclusion/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, writing a research paper introduction | step-by-step guide, how to create a structured research paper outline | example, checklist: writing a great research paper, what is your plagiarism score.

Action Research: Steps, Benefits, and Tips

Introduction

History of action research, what is the definition of action research, types of action research, conducting action research.

Action research stands as a unique approach in the realm of qualitative inquiry in social science research. Rooted in real-world problems, it seeks not just to understand but also to act, bringing about positive change in specific contexts. Often distinguished by its collaborative nature, the action research process goes beyond traditional research paradigms by emphasizing the involvement of those being studied in resolving social conflicts and effecting positive change.

The value of action research lies not just in its outcomes, but also in the process itself, where stakeholders become active participants rather than mere subjects. In this article, we'll examine action research in depth, shedding light on its history, principles, and types of action research.

Tracing its roots back to the mid-20th century, Kurt Lewin developed classical action research as a response to traditional research methods in the social sciences that often sidelined the very communities they studied. Proponents of action research championed the idea that research should not just be an observational exercise but an actionable one that involves devising practical solutions. Advocates believed in the idea of research leading to immediate social action, emphasizing the importance of involving the community in the process.

Applications for action research

Over the years, action research has evolved and diversified. From its early applications in social psychology and organizational development, it has branched out into various fields such as education, healthcare, and community development, informing questions around improving schools, minority problems, and more. This growth wasn't just in application, but also in its methodologies.

How is action research different?

Like all research methodologies, effective action research generates knowledge. However, action research stands apart in its commitment to instigate tangible change. Traditional research often places emphasis on passive observation , employing data collection methods primarily to contribute to broader theoretical frameworks . In contrast, action research is inherently proactive, intertwining the acts of observing and acting.

The primary goal isn't just to understand a problem but to solve or alleviate it. Action researchers partner closely with communities, ensuring that the research process directly benefits those involved. This collaboration often leads to immediate interventions, tweaks, or solutions applied in real-time, marking a departure from other forms of research that might wait until the end of a study to make recommendations.

This proactive, change-driven nature makes action research particularly impactful in settings where immediate change is not just beneficial but essential.

Action research is best understood as a systematic approach to cooperative inquiry. Unlike traditional research methodologies that might primarily focus on generating knowledge, action research emphasizes producing actionable solutions for pressing real-world challenges.

This form of research undertakes a cyclic and reflective journey, typically cycling through stages of planning , acting, observing, and reflecting. A defining characteristic of action research is the collaborative spirit it embodies, often dissolving the rigid distinction between the researcher and the researched, leading to mutual learning and shared outcomes.

Advantages of action research

One of the foremost benefits of action research is the immediacy of its application. Since the research is embedded within real-world issues, any findings or solutions derived can often be integrated straightaway, catalyzing prompt improvements within the concerned community or organization. This immediacy is coupled with the empowering nature of the methodology. Participants aren't mere subjects; they actively shape the research process, giving them a tangible sense of ownership over both the research journey and its eventual outcomes.

Moreover, the inherent adaptability of action research allows researchers to tweak their approaches responsively based on live feedback. This ensures the research remains rooted in the evolving context, capturing the nuances of the situation and making any necessary adjustments. Lastly, this form of research tends to offer a comprehensive understanding of the issue at hand, harmonizing socially constructed theoretical knowledge with hands-on insights, leading to a richer, more textured understanding.

Disadvantages of action research

Like any methodology, action research isn't devoid of challenges. Its iterative nature, while beneficial, can extend timelines. Researchers might find themselves engaged in multiple cycles of observation, reflection, and action before arriving at a satisfactory conclusion. The intimate involvement of the researcher with the research participants, although crucial for collaboration, opens doors to potential conflicts. Through collaborative problem solving, disagreements can lead to richer and more nuanced solutions, but it can take considerable time and effort.

Another limitation stems from its focus on a specific context: results derived from a particular action research project might not always resonate or be applicable in a different context or with a different group. Lastly, the depth of collaboration this methodology demands means all stakeholders need to be deeply invested, and such a level of commitment might not always be feasible.

Examples of action research

To illustrate, let's consider a few scenarios. Imagine a classroom where a teacher observes dwindling student participation. Instead of sticking to conventional methods, the teacher experiments with introducing group-based activities. As the outcomes unfold, the teacher continually refines the approach based on student feedback, eventually leading to a teaching strategy that rejuvenates student engagement.

In a healthcare context, hospital staff who recognize growing patient anxiety related to certain procedures might innovate by introducing a new patient-informing protocol. As they study the effects of this change, they could, through iterations, sculpt a procedure that diminishes patient anxiety.

Similarly, in the realm of community development, a community grappling with the absence of child-friendly public spaces might collaborate with local authorities to conceptualize a park. As they monitor its utilization and societal impact, continual feedback could refine the park's infrastructure and design.

Contemporary action research, while grounded in the core principles of collaboration, reflection, and change, has seen various adaptations tailored to the specific needs of different contexts and fields. These adaptations have led to the emergence of distinct types of action research, each with its unique emphasis and approach.

Collaborative action research

Collaborative action research emphasizes the joint efforts of professionals, often from the same field, working together to address common concerns or challenges. In this approach, there's a strong emphasis on shared responsibility, mutual respect, and co-learning. For example, a group of classroom teachers might collaboratively investigate methods to improve student literacy, pooling their expertise and resources to devise, implement, and refine strategies for improving teaching.

Participatory action research

Participatory action research (PAR) goes a step further in dissolving the barriers between the researcher and the researched. It actively involves community members or stakeholders not just as participants, but as equal partners in the entire research process. PAR is deeply democratic and seeks to empower participants, fostering a sense of agency and ownership. For instance, a participatory research project might involve local residents in studying and addressing community health concerns, ensuring that the research process and outcomes are both informed by and beneficial to the community itself.

Educational action research

Educational action research is tailored specifically to practical educational contexts. Here, educators take on the dual role of teacher and researcher, seeking to improve teaching practices, curricula, classroom dynamics, or educational evaluation. This type of research is cyclical, with educators implementing changes, observing outcomes, and reflecting on results to continually enhance the educational experience. An example might be a teacher studying the impact of technology integration in her classroom, adjusting strategies based on student feedback and learning outcomes.

Community-based action research

Another noteworthy type is community-based action research, which focuses primarily on community development and well-being. Rooted in the principles of social justice, this approach emphasizes the collective power of community members to identify, study, and address their challenges. It's particularly powerful in grassroots movements and local development projects where community insights and collaboration drive meaningful, sustainable change.

Key insights and critical reflection through research with ATLAS.ti

Organize all your data analysis and insights with our powerful interface. Download a free trial today.

Engaging in action research is both an enlightening and transformative journey, rooted in practicality yet deeply connected to theory. For those embarking on this path, understanding the essentials of an action research study and the significance of a research cycle is paramount.

Understanding the action research cycle

At the heart of action research is its cycle, a structured yet adaptable framework guiding the research. This cycle embodies the iterative nature of action research, emphasizing that learning and change evolve through repetition and reflection.

The typical stages include:

- Identifying a problem : This is the starting point where the action researcher pinpoints a pressing issue or challenge that demands attention.

- Planning : Here, the researcher devises an action research strategy aimed at addressing the identified problem. In action research, network resources, participant consultation, and the literature review are core components in planning.

- Action : The planned strategies are then implemented in this stage. This 'action' phase is where theoretical knowledge meets practical application.

- Observation : Post-implementation, the researcher observes the outcomes and effects of the action. This stage ensures that the research remains grounded in the real-world context.

- Critical reflection : This part of the cycle involves analyzing the observed results to draw conclusions about their effectiveness and identify areas for improvement.

- Revision : Based on the insights from reflection, the initial plan is revised, marking the beginning of another cycle.

Rigorous research and iteration

It's essential to understand that while action research is deeply practical, it doesn't sacrifice rigor . The cyclical process ensures that the research remains thorough and robust. Each iteration of the cycle in an action research project refines the approach, drawing it closer to an effective solution.

The role of the action researcher

The action researcher stands at the nexus of theory and practice. Not just an observer, the researcher actively engages with the study's participants, collaboratively navigating through the research cycle by conducting interviews, participant observations, and member checking . This close involvement ensures that the study remains relevant, timely, and responsive.

Drawing conclusions and informing theory

As the research progresses through multiple iterations of data collection and data analysis , drawing conclusions becomes an integral aspect. These conclusions, while immediately beneficial in addressing the practical issue at hand, also serve a broader purpose. They inform theory, enriching the academic discourse and providing valuable insights for future research.

Identifying actionable insights

Keep in mind that action research should facilitate implications for professional practice as well as space for systematic inquiry. As you draw conclusions about the knowledge generated from action research, consider how this knowledge can create new forms of solutions to the pressing concern you set out to address.

Collecting data and analyzing data starts with ATLAS.ti

Download a free trial of our intuitive software to make the most of your research.

Main Navigation Menu

Action research.

- Getting Started

- Action Research by Groups

- The Teacher Action Researcher

- Bibliography & Additional Resources

Education Liaison Librarian

What is Action Research?

Action research involves a systematic process of examining the evidence. The results of this type of research are practical, relevant, and can inform theory. Action research is different than other forms of research as there is less concern for universality of findings, and more value is placed on the relevance of the findings to the researcher and the local collaborators.

Riel, M. (2020). Understanding action research. Center For Collaborative Action Research, Pepperdine University. Retrieved January 31, 2021 from the Center for Collaborative Action Research. https://www.actionresearchtutorials.org/

-----------------------------------

The short video below by John Spencer provides a quick overview of Action Research.

How is Action Research different?

This chart demonstrates the difference between traditional research and action research. Traditional research is a means to an end - the conclusion. They start with a theory, statistical analysis is critical and the researcher does not insert herself into the research.

Action research is often practiced by practitioners like teachers and librarians who remain in the middle of the research process. They are looking for ways to improve the specific situation for their clientele or students. Statistics may be collected but they are not the point of the research.

Adapted from: Mc Millan, J. H. & Wergin. J. F. (1998). Understanding and evaluating educational research. Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Teacher Action Research

According to Paul Gorski, Action Research for educators meets the following qualifications:

- a non-traditional and community-based form of educational evaluation;

- carried out by educators, not outside researchers or evaluators;

- focused on improving teaching and learning, but also social and environmental factors that affect the nature and success of teaching and learning;

- formative, not summative--an on-going process of evaluation, recommendation, practice, reflection, and reevaluation; and

- change-oriented, and undertaken with the assumption that change is needed in a given context

Gorski, P. C. (1995-2018). Teacher Action Research . Critical Multicultural Pavilion. Retrieved October 6, 2018 from https://www.edchange.org/multicultural/tar.html

- Next: Action Research by Groups >>

- Last Updated: Mar 12, 2024 3:14 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucmo.edu/actionresearch

Research Design in Business and Management pp 117–139 Cite as

Action Research Design

- Stefan Hunziker 3 &

- Michael Blankenagel 3

- First Online: 10 November 2021

2948 Accesses

This chapter addresses the peculiarities, characteristics, and major fallacies of action research design. This research design is a change-oriented approach. Its central assumption is that complex social processes can best be studied by introducing change into these processes and observing their effects. The fundamental basis for action research is taking actions to address organizational problems and their associated unsatisfactory conditions. Also, researchers find relevant information on how to write an action research paper and learn about typical methodologies used for this research design. The chapter closes with referring to overlapping and adjacent research designs.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Altrichter, H., Kemmis, S., McTaggart, R., & Zuber-Skerritt, O. (2002). The concept of action research. The Learning Organization, 9 (3), 125–131.

Article Google Scholar

Bamberger, G. G. (2015). Lösungsorientierte Beratung . 5. Auflage. Weinheim: Beltz.

Google Scholar

Baskerville, R. (1999). Investigating Information Systems with Action Research. Communications of AIS, Volume 2, Article 19. Available online at https://wise.vub.ac.be/sites/default/files/thesis_info/action_research.pdf .

Baskerville, R. (2001). Conducting action research: high risk and high reward in theory and practice. In E. M. Trauth (Ed.), Qualitative research in is: issues and trends (pp. 192–217). Hershey, PA, USA: IGI Publishing.

Baskerville, R. & Lee. A. (1999). Distinctions Among Different Types of Generalizing in Information Systems Research.” In O. Ngwenyama et al., (Ed.), New IT Technologies in Organizational Processes: Field Studies and Theoretical Reflections on the Future of Work . New York: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Baskerville, R., & Wood-Harper, A. T. (1998). Diversity in information systems action research methods. European Journal of Information Systems, 7 (2), 90–107.

Blichfeldt, B. S., & Andersen, J. R. (2006). Creating a wider audience for action research: Learning from case-study research. Journal of Research Practice, 2 (1), Article D2. Retrieved May 10, 2021, from http://jrp.icaap.org/index.php/jrp/article/view/23/69 .

Borrego, M., Douglas, E. P., & Amelink, C. T. (2009). Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed research methods in engineering education. Journal of Engineering Education, 98 (1), 53–66.

Bunning, C. (1995). Placing action learning and action research in context . International Management Centre.

Cauchick, M. (2011). Metodologia de Pesquisa em Engenharia ee Produção e Gestão de Operações. (2nd ed.). Elsevier.

Coghlan, D., & Shani, A. B. (2005). Roles, politics and ethics in action research design. Systemic Practice and Action Research, 18 (6), 533–546.

Cole, R., Purao, S., Rossi, M., & Sein, M. K. (2005). Being proactive: Where action research meets design research. ICIS .

Collatto, D. C., Dresch, A., Lacerda, D. P., & Bentz, I. G. (2018). Is action design research indeed necessary? Analysis and synergies between action research and design science research. Systemic Practice and Action Research, 31 (3), 239–267.

Coughlan, P., & Coghlan, D. (2002). Action research for operations management. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 22 (2), 220–240.

Cunningham, J. B. (1993). Action research and organizational development . Praeger Publishers.

Davison, R. M. & Martinsons, M. G. (2007). Action Research and Consulting. In Ned Kock (Ed.), Information systems action research. An applied view of emerging concepts and methods, vol. 13. New York: Springer (Integrated Series in Information Systems, vol. 13), pp. 377–394.

Davison, R., Martinsons, M. G., & Kock, N. (2004). Principles of canonical action research. Information Systems Journal, 14 (1), 65–86.

Dick, B. (2003). Rehabilitating action research: Response to Davydd Greenwood’s and Björn Gustavsen’s papers on action research perspectives. Concepts and Transformation, 7 (2), 2002 and 8 (1), 2003. Concepts and Transformation, 8 (3), 255–263.

Dickens, L., & Watkins, K. (1999). Action Research: Rethinking Lewin. Management Learning, 30 (2), 127–140.

Eden, C., & Huxham, C. (1996). Action research for management research. British Journal of Management, 7 (1), 75–86.

Foster, M. (1972). An introduction to the theory and practice of action research in work organizations. Human Relations, 25 (6), 529–556.