The Role of Art and Music Therapies in Mental Health and Beyond

Prescribing art therapy , yoga, and music lessons is truly a breakthrough for mental health treatment . I want to be completely clear here, this is a breakthrough, but not a breakthrough therapy per se. It is a huge step forward, on the level of readjusting our mental health system, it is really a systems course correction at the root of it. Art therapy, music, etc., all are tested modalities for improving mental health conditions; almost all of them. For chronic, highly disordered and severely dysfunctional patients, this is not a miracle cure. These are, at best, supplementary, tandem, and co-functioning treatment methods to mitigate the severity and intensity of symptoms.

I am not knocking or trying to minimise the importance of this breakthrough. These are not only important modalities in and of themselves, but also support the creativity , independence, and freedom of patients to not only choose their own method of care but also nourish their capacity to carry on treatment more autonomously without being under direct supervision .

Even more importantly, the system is broken, in total if not complete disarray, and needs to be revised urgently if we are to advance treatment at the speed it requires to meet the mental health crisis where it’s at. These new prescribed modalities will not only serve to add ‘person-centredness’ to the paradigm but also new flexibility within the limits of the system.

Even highly disordered patients are extremely creative during their darkest hour. Art therapy, music, and all of these modalities which draw upon creativity and promote purposeful free-flowing ideas are as self-soothing as they are productive in reducing the negative impact of active symptoms.

I can tell you that I have benefited from a music or art group on an inpatient unit in the hospital many times. Some of my fondest memories from experiencing first-episode psychosis in the hospital were singing and dancing to Stevie Nicks , at my request, when I could barely speak from word salad symptoms and was just a few moments away from being transferred to a higher level of inpatient care for unresolved psychosis. But I danced and laughed like the floor was on fire.

Art, music, yoga, all of these modalities are terribly inaccessible to most patients living off state benefits, who are consigned to a life shut-in and isolated in their homes. Aside from ‘getting out more’, these patients simply don’t have the resources to pay for and maintain a connection to art therapists and other more non-traditional treatment in the community. Unless you are connected to a special service or have the best insurance, these modalities simply aren’t an option for most service users and people with a severe mental health condition.

I truly applaud this shift in the systems paradigm that for so long was all about medication and traditional psychotherapy. We really need more of this in countries supposedly promoting better mental health treatment.

I also want to suggest that therapists who practice traditional talk therapy , straight CBT (cognitive behavioural therapy) can continue to add new self-soothing and proven techniques to their toolkit. I am always encouraging my student therapists to do artwork, let their children dance in therapy. Yes, you read this right, just dance, when the time is right and fits the course of treatment.

We need to get out of this traditional black and white thinking of what therapy is and is not . Therapy is what people need in the moment, to feel and behave in a manner that better suits their goals, chosen lifestyle, and needs. So with this said, why not let a child who is struggling to adjust to a new foster parent, dance in session when he can’t play at home. Sure, not for every session and for the duration of every patient contact, but sometimes, when it will benefit the patient, you just have to do it.

Yes, this is truly a breakthrough in thinking among us practitioners and the higher-ups in our discipline who say what’s what in mental health treatment. It signals that we need to be dynamic, and shift our thinking as practitioners, peers, and anyone charged with providing therapeutic intervention . It is high time we see more of it, from government-sponsored care and any system which is charged with the care of people with a psychiatric disability, or who needs therapeutic intervention to find relief from whatever problem in their life is causing them distress.

Max E. Guttman, LCSW is a psychotherapist and owner of Recovery Now, a mental health private practice in New York City.

VIEW AUTHOR’S PROFILE

Related Articles

Surprising factors that can impact mental health for better or worse, how addressing the mental health of millennials and gen z benefits upcoming generations, world mental health experts join summit to solve “brain health emergency” on 24th april, chiva-som hua hin encourages reflection on wellness with additional special benefits and experiences, stress and mental health challenges can alter our ability to filter thoughts, why it is important to have a ketamine therapy for depression, different types of anxiety and how therapy can help, head spa essentials: what you need, join wisdomania for 2 days of free wellness and creativity in la, the exodus of compassion: when good people leave the mental health system, experts shed light on neurodivergent-friendly lighting schemes, discover the benefits of holistic therapy: a comprehensive guide to integrative healing, “i’m a sleep expert” – here’s my top tips for sleeping better when feeling stressed and anxious, the importance of group fitness for social connection, royal college of psychiatrists says 10-year waits for bipolar diagnosis “unacceptable”, pet grooming – keeping your pet physically and psychologically healthy, mental health is a journey of personal growth and resilience, the psychological impact of pursuing a career in saving lives, how speech-to-text technology elevates mental health practices, restore investment in mental health support for nhs and social care staff, say leading organisations, understanding the mental toll of chronic illness on patients and families, the mental health benefits you can get from doing float tank therapy, bipolar uk supports big mood, navigating the intersection of mental health and the law: bridging the gap.

Psychreg is a digital media company and not a clinical company. Our content does not constitute a medical or psychological consultation. See a certified medical or mental health professional for diagnosis.

- Privacy Policy

© Copyright 2014–2034 Psychreg Ltd

- PSYCHREG JOURNAL

- MEET OUR WRITERS

- MEET THE TEAM

REVIEW article

Art therapy: a complementary treatment for mental disorders.

- 1 College of Creative Design, Shenzhen Technology University, Shenzhen, China

- 2 The Fourth Clinical Medical College of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, Shenzhen, China

- 3 Institute of Biomedical and Health Engineering, Shenzhen Institutes of Advanced Technology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shenzhen, China

Art therapy, as a non-pharmacological medical complementary and alternative therapy, has been used as one of medical interventions with good clinical effects on mental disorders. However, systematically reviewed in detail in clinical situations is lacking. Here, we searched on PubMed for art therapy in an attempt to explore its theoretical basis, clinical applications, and future perspectives to summary its global pictures. Since drawings and paintings have been historically recognized as a useful part of therapeutic processes in art therapy, we focused on studies of art therapy which mainly includes painting and drawing as media. As a result, a total of 413 literature were identified. After carefully reading full articles, we found that art therapy has been gradually and successfully used for patients with mental disorders with positive outcomes, mainly reducing suffering from mental symptoms. These disorders mainly include depression disorders and anxiety, cognitive impairment and dementias, Alzheimer’s disease, schizophrenia, and autism. These findings suggest that art therapy can not only be served as an useful therapeutic method to assist patients to open up and share their feelings, views, and experiences, but also as an auxiliary treatment for diagnosing diseases to help medical specialists obtain complementary information different from conventional tests. We humbly believe that art therapy has great potential in clinical applications on mental disorders to be further explored.

Introduction

Mental disorders constitute a huge social and economic burden for health care systems worldwide ( Zschucke et al., 2013 ; Kenbubpha et al., 2018 ). In China, the lifetime prevalence of mental disorders was 24.20%, and 1-month prevalence of mental disorders was 14.27% ( Xu et al., 2017 ). The situation is more severely in other countries, especially for developing ones. Given the large numbers of people in need and the humanitarian imperative to reduce suffering, there is an urgent need to implement scalable mental health interventions to address this burden. While pharmacological treatment is the first choice for mental disorders to alleviate the major symptoms, many antipsychotics contribute to poor quality of life and debilitating adverse effects. Therefore, clinicians have turned toward to complementary treatments, such as art therapy in addressing the health needs of patients more than half a century ago.

Art therapy, is defined by the British Association of Art Therapists as: “a form of psychotherapy that uses art media as its primary mode of expression and communication. Clients referred to art therapists are not required to have experience or skills in the arts. The art therapist’s primary concern is not to make an esthetic or diagnostic assessment of the client’s image. The overall goal of its practitioners is to enable clients to change and grow on a personal level through the use of artistic materials in a safe and convenient environment” ( British Association of Art Therapists, 2015 ), whereas as: “an integrative mental health and human services profession that enriches the lives of individuals, families, and communities through active art-making, creative process, applied psychological theory, and human experience within a psycho-therapeutic relationship” ( American Art Therapy Association, 2018 ) according to the American Art Association. It has gradually become a well-known form of spiritual support and complementary therapy ( Faller and Schmidt, 2004 ; Nainis et al., 2006 ). During the therapy, art therapists can utilize many different art materials as media (i.e., visual art, painting, drawing, music, dance, drama, and writing) ( Deshmukh et al., 2018 ; Chiang et al., 2019 ). Among them, drawings and paintings have been historically recognized as the most useful part of therapeutic processes within psychiatric and psychological specialties ( British Association of Art Therapists, 2015 ). Moreover, many other art forms gradually fall under the prevue of their own professions (e.g., music therapy, dance/movement therapy, and drama therapy) ( Deshmukh et al., 2018 ). Thus, we excluded these studies and only focused on studies of art therapy which mainly includes painting and drawing as media. Specifically, it focuses on capturing psychodynamic processes by means of “inner pictures,” which become visible by the creative process ( Steinbauer et al., 1999 ). These pictures reflect the psychopathology of different psychiatric disorders and even their corresponding therapeutic process based on specific rules and criterion ( Steinbauer and Taucher, 2001 ). It has been gradually recognized and used as an alternative treatment for therapeutic processes within psychiatric and psychological specialties, as well as medical and neurology-based scientific audiences ( Burton, 2009 ).

The development of art therapy comes partly from the artistic expression of the belief in unspoken things, and partly from the clinical work of art therapists in the medical setting with various groups of patients ( Malchiodi, 2013 ). It is defined as the application of artistic expressions and images to individuals who are physically ill, undergoing invasive medical procedures, such as surgery or chemotherapy for clinical usage ( Bar-Sela et al., 2007 ; Forzoni et al., 2010 ; Liebmann and Weston, 2015 ). The American Art Therapy Association describes its main functions as improving cognitive and sensorimotor functions, fostering self-esteem and self-awareness, cultivating emotional resilience, promoting insight, enhancing social skills, reducing and resolving conflicts and distress, and promoting societal and ecological changes ( American Art Therapy Association, 2018 ).

However, despite the above advantages, published systematically review on this topic is lacking. Therefore, this review aims to explore its clinical applications and future perspectives to summary its global pictures, so as to provide more clinical treatment options and research directions for therapists and researchers.

Publications of Art Therapy

The literatures about “art therapy” published from January 2006 to December 2020 were searched in the PubMed database. The following topics were used: Title/Abstract = “art therapy,” Indexes Timespan = 2006–2020.

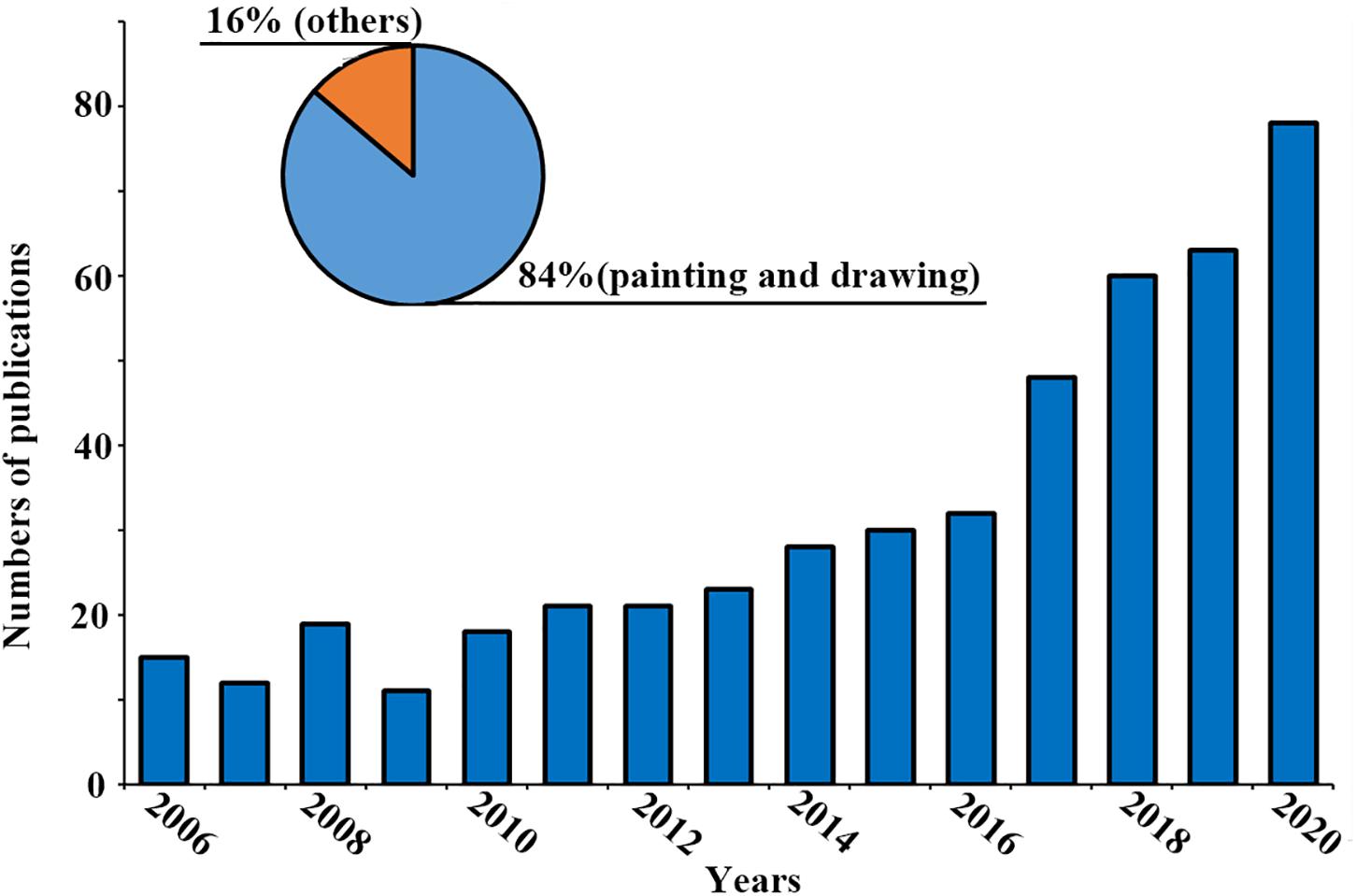

A total of 652 records were found. Then, we manually screened out the literatures that contained the word “art” but was not relevant with the subject of this study, such as state of the art therapy, antiretroviral therapy (ART), and assisted reproductive technology (ART). Finally, 479 records about art therapy were identified. Since we aimed to focus on art therapy included painting and drawing as major media, we screened out literatures deeper, and identified 413 (84%) literatures involved in painting and drawing ( Figure 1 ).

Figure 1. Number of publications about art therapy.

As we can see, the number of literature about art therapy is increasing slowly in the last 15 years, reaching a peak in 2020. This indicates that more effort was made on this topic in recent years ( Figure 1 ).

Overview of Art Therapy

As defined by the British Association of Art Therapists, art therapy is a form of psychotherapy that uses art media as its primary mode of communication. Based on above literature, several highlights need to be summarized. (1) The main media of art therapy include painting, drawing, music, drama, dance, drama, and writing ( Chiang et al., 2019 ). (2) Main contents of painting and drawing include blind drawing, spiral drawing, drawing moods and self-portraits ( Legrand et al., 2017 ; Abbing et al., 2018 ; Papangelo et al., 2020 ). (3) Art therapy is mainly used for cancer, depression and anxiety, autism, dementia and cognitive impairment, as these patients are reluctant to express themselves in words ( Attard and Larkin, 2016 ; Deshmukh et al., 2018 ; Chiang et al., 2019 ). It plays an important role in facilitating engagement when direct verbal interaction becomes difficult, and provides a safe and indirect way to connect oneself with others ( Papangelo et al., 2020 ). Moreover, we found that art therapy has been gradually and successfully used for patients with mental disorders with positive outcomes, mainly reducing suffering from mental symptoms. These findings suggest that art therapy can not only be served as an useful therapeutic method to assist patients to open up and share their feelings, views, and experiences, but also as an auxiliary treatment for diagnosing diseases to help medical specialists obtain complementary information different from conventional tests.

Art Therapy for Mental Disorders

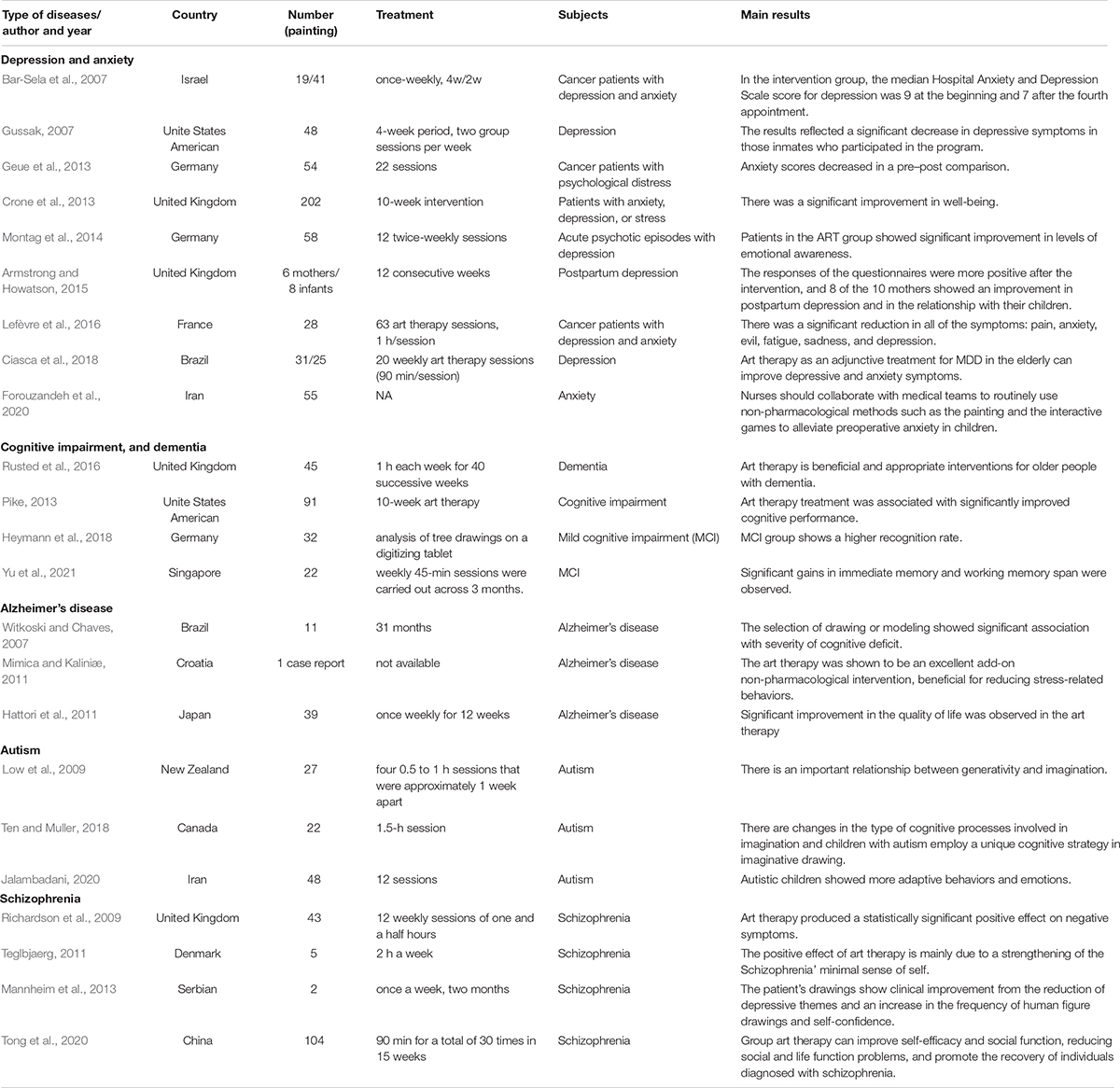

Based on the 413 searched literatures, we further limited them to mental disorders using the following key words, respectively: Depression OR anxiety OR Cognitive impairment OR dementia OR Alzheimer’s disease OR Autism OR Schizophrenia OR mental disorder. As a result, a total of 23 studies (5%) ( Table 1 ) were included and classified after reading the abstract and the full text carefully. These studies include 9 articles on depression and anxiety, 4 articles on cognitive impairment and dementia, 3 articles on Alzheimer’s disease, 3 articles on autism, and 4 articles on schizophrenia. In addition to the English literature, in fact, some Chinese literatures also described the application of art therapy in mental diseases, which were not listed but referred to in the following specific literatures.

Table 1. Studies of art therapy in mental diseases.

Depression Disorders and Anxiety

Depression and anxiety disorders are highly prevalent, affecting individuals, their families and the individual’s role in society ( Birgitta et al., 2018 ). Depression is a disabling and costly condition associated with a significant reduction in quality of life, medical comorbidities and mortality ( Demyttenaere et al., 2004 ; Whiteford et al., 2013 ; Cuijpers et al., 2014 ). Anxiety is associated with lower quality of life and negative effects on psychosocial functioning ( Cramer et al., 2005 ). Medication is the most commonly used effective way to relieve symptoms of depression and anxiety. However, nonadherence are crucial shortcomings in using antidepressant to treat depression and anxiety ( van Geffen et al., 2007 ; Nielsen et al., 2019 ).

In recent years, many studies have shown that art therapy plays a significant role in alleviating depression symptoms and anxiety. Gussak (2007) performed an observational survey about populations in prison of northern Florida and identified that art therapy significantly reduces depressive symptoms. Similarly, a randomized, controlled, and single-blind study about art therapy for depression with the elderly showed that painting as an adjuvant treatment for depression can reduce depressive and anxiety symptoms ( Ciasca et al., 2018 ). In addition, art therapy is also widely used among students, and several studies ( Runde, 2008 ; Zhenhai and Yunhua, 2011 ) have shown that art therapy also significantly reduces depressive symptoms in students. For example, Wang et al. (2011) conducted group painting therapy on 30 patients with depression for 3 months, and found that painting therapy could promote their social function recovery, improve their social adaptability and quality of life. Another randomized clinical trial also showed that it could decrease mean anxiety scores in the 3–12 year painting group ( Forouzandeh et al., 2020 ).

Studies have shown that distress, including anxiety and depression, is related to poorer health-related quality of life and satisfaction to medical services ( Hamer et al., 2009 ). Painting can be employed to express patients’ anxiety and fear, vent negative emotions by applying projection, thereby significantly improve the mood and reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety of cancer patients. A number of studies ( Bar-Sela et al., 2007 ; Thyme et al., 2009 ; Lin et al., 2012 ; Abdulah and Abdulla, 2018 ) showed that art therapy for cancer patients could enhance the vitality of patients and participation in social activities, significantly reduce depression, anxiety, and reduce stressful feelings. Importantly, even in the follow-up period, art therapy still has a lasting effect on cancer patients ( Thyme et al., 2009 ). Interestingly, art therapy based on famous painting appreciation could also significantly reduce anxiety and depression associated with cancer ( Lee et al., 2017 ). Among cancer patients treated in outpatient health care, art therapy also plays an important role in alleviating their physical symptoms and mental health ( Götze et al., 2009 ). Therefore, art therapy as an auxiliary treatment of cancer is of great value in improving quality of life.

Overall, art painting therapy permits patients to express themselves in a manner acceptable to the inside and outside culture, thereby diminishing depressed and anxiety symptoms.

Cognitive Impairment, and Dementia

Dementia, a progressive clinical syndrome, is characterized by widespread cognitive impairment in memory, thinking, behavior, emotion and performance, leading to worse daily living ( Deshmukh et al., 2018 ). According to the Alzheimer’s Disease International 2015, there is 46.8 million people suffered from dementia, and numbers almost doubling every 20 years, rising to 131.5 million by 2050. Although art therapy has been used as an alternative treatment for the dementia for long time, the positive effects of painting therapy on cognitive function remain largely unknown. One intervention assigned older adults patients with dementia to a group-based art therapy (including painting) observed significant improvements in the clock drawing test ( Pike, 2013 ), whereas two other randomized controlled trials ( Hattori et al., 2011 ; Rusted et al., 2016 ) on patients with dementia have failed to obtain significant cognitive improvement in the painting group. Moreover, a cochrane systematic review ( Deshmukh et al., 2018 ) included two clinical studies of art therapy for dementia revealed that there is no sufficient evidence about the efficacy of art therapy for dementia. This may be because patients with severely cognitive impairment, who was unable to accurately remember or assess their own behavior or mental state, might lose the ability to enjoy the benefits of art therapy.

In summary, we should intervene earlier in patients with mild cognitive impairment, an intermediate stage between normal aging and dementia, in order to prevent further transformation into dementia. To date, mild cognitive impairment is drawing much attention to the importance of painting intervening at this stage in order to alter the course of subsequent cognitive decline as soon as possible ( Petersen et al., 2014 ). Recently, a randomized controlled trial ( Yu et al., 2021 ) showed significant relationship between improvement immediate memory/working memory span and increased cortical thickness in right middle frontal gyrus in the painting art group. With the long-term cognitive stimulation and engagement from multiple sessions of painting therapy, it is likely that painting therapy could lead to enhanced cognitive functioning for these patients.

Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a sub-type of dementia, which is usually associated with chronic pain. Previous studies suggested that art therapy could be used as a complementary treatment to relief pain for these patients since medication might induce severely side effects. In a multicenter randomized controlled trial, 28 mild AD patients showed significant pain reduction, reduced anxiety, improved quality of life, improved digit span, and inhibitory processes, as well as reduced depression symptoms after 12-week painting ( Pongan et al., 2017 ; Alvarenga et al., 2018 ). Further study also suggested that individual therapy rather than group therapy could be more optimal since neuroticism can decrease efficacy of painting intervention on pain in patients with mild AD. In addition to release chronic pain, art therapy has been reported to show positive effects on cognitive and psychological symptoms in patients with mild AD. For example, a controlled study revealed significant improvement in the apathy scale and quality of life after 12 weeks of painting treatment mainly including color abstract patterns with pastel crayons or water-based paint ( Hattori et al., 2011 ). Another study also revealed that AD patients showed improvement in facial expression, discourse content and mood after 3-weeks painting intervention ( Narme et al., 2012 ).

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a complex functional psychotic mental illness that affects about 1% of the population at some point in their life ( Kolliakou et al., 2011 ). Not only do sufferers experience “positive” symptoms such as hallucinations, delusions, but also experience negative symptoms such as varying degrees of anhedonia and asociality, impaired working memory and attention, poverty of speech, and lack of motivation ( Andreasen and Olsen, 1982 ). Many patients with schizophrenia remain symptomatic despite pharmacotherapy, and even attempts to suicide with a rate of 10 to 50% ( De Sousa et al., 2020 ). For these patients, art therapy is highly recommended to process emotional, cognitive and psychotic experiences to release symptoms. Indeed, many forms of art therapy have been successfully used in schizophrenia, whether and how painting may interfere with psychopathology to release symptoms remains largely unknown.

A recent review including 20 studies overall was performed to summary findings, however, concluded that it is not clear whether art therapy leads to clinical improvement in schizophrenia with low ( Ruiz et al., 2017 ). Anyway, many randomized clinical trials reported positive outcomes. For example, Richardson et al. (2007) conducted painting therapy for six months in patients with chronic schizophrenia and found that art therapy had a positive effect on negative symptoms. Teglbjaerg (2011) examined experience of each patient using interviews and written evaluations before and after painting therapy and at a 1-year follow-up and found that group painting therapy in patients with schizophrenia could not only reduce psychotic symptoms, but also boost self-esteem and improve social function.

What’s more, the characteristics of the painting can also be used to judge the health condition in patients with schizophrenia. For example, Hongxia et al. (2013) explored the correlation between psychological health condition and characteristics of House-Tree-Person tests for patients with schizophrenia, and showed that the detail characteristic of the test results can be used to judge the patient’s anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive symptoms.

Most importantly, several other studies showed that drug plus painting therapy significantly enhanced patient compliance and self-cognition than drug therapy alone in patients with schizophrenia ( Hongyan and JinJie, 2010 ; Min, 2010 ).

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a heterogeneous neurodevelopmental syndrome with no unified pathological or neurobiological etiology, which is characterized by difficulties in social interaction, communication problems, and a tendency to engage in repetitive behaviors ( Geschwind and Levitt, 2007 ).

Art therapy is a form of expression that opens the door to communication without verbal interaction. It provides therapists with the opportunity to interact one-on-one with individuals with autism, and make broad connections in a more comfortable and effective way ( Babaei et al., 2020 ). Emery (2004) did a case study about a 6-year-old boy diagnosed with autism and found that art therapy is of great value to the development, growth and communication skills of the boy. Recently, one study ( Jalambadani, 2020 ) using 40 children with ASD participating in painting therapy showed that painting therapy had a significant improvement in the social interactions, adaptive behaviors and emotions. Therefore, encouraging children with ASD to express their experience by using nonverbal expressions is crucial to their development. Evans and Dubowski (2001) believed that creating images on paper could help children express their internal images, thereby enhance their imagination and abstract thinking. Painting can also help autistic children express and vent negative emotions and thereby bring positive emotional experience and promote their self-consciousness ( Martin, 2009 ). According to two studies ( Wen and Zhaoming, 2009 ; Jianhua and Xiaolu, 2013 ) in China, Art therapy could also improve the language and communication skills, cognitive and behavioral performance of children with ASD.

Moreover, art therapy could be used to investigate the relationship between cognitive processes and imagination in children with ASD. One study ( Wen and Zhaoming, 2009 ; Jianhua and Xiaolu, 2013 ) suggested that children with ASD apply a unique cognitive strategy in imaginative drawing. Another study ( Low et al., 2009 ) examined the cognitive underpinnings of spontaneous imagination in children with ASD and showed that ASD group lacks imagination, generative ability, planning ability and good consistency in their drawings. In addition, several studies ( Leevers and Harris, 1998 ; Craig and Baron-Cohen, 1999 ; Craig et al., 2001 ) have been performed to investigate imagination and creativity of autism via drawing tasks, and showed impairments of autism in imagination and creativity via drawing tasks.

In a word, art therapy plays a significant role in children with ASD, not only as a method of treatment, but also in understanding and investigating patients’ problems.

Other Applications

In addition to the above mentioned diseases, art therapy has also been adopted in other applications. Dysarthia is a common sequela of cerebral palsy (CP), which directly affects children’s language intelligibility and psycho-social adjustment. Speech therapy does not always help CP children to speak more intelligibly. Interestingly, the art therapy can significantly improve the language intelligibility and their social skills for children with CP ( Wilk et al., 2010 ).

In brief, these studies suggest that art therapy is meaningful and accepted by both patients and therapists. Most often, art therapy could strengthen patient’s emotional expression, self-esteem, and self-awareness. However, our findings are based on relatively small samples and few good-quality qualitative studies, and require cautious interpretation.

The Application Prospects of Art Therapy

With the development of modern medical technology, life expectancy is also increasing. At the same time, it also brings some side effects and psychological problems during the treatment process, especially for patients with mental illness. Therefore, there is an increasing demand for finding appropriate complementary therapies to improve life quality of patients and psychological health. Art therapy is primarily offered as individual art therapy, in this review, we found that art therapy was most commonly used for depression and anxiety.

Based on the above findings, art therapy, as a non-verbal psychotherapy method, not only serves as an auxiliary tool for diagnosing diseases, which helps medical specialists obtain much information that is difficult to gain from conventional tests, judge the severity and progression of diseases, and understand patients’ psychological state from painting characteristics, but also is an useful therapeutic method, which helps patients open up and share their feelings, views, and experiences. Additionally, the implementation of art therapy is not limited by age, language, diseases or environment, and is easy to be accepted by patients.

Art therapy in hospitals and clinical settings could be very helpful to aid treatment and therapy, and to enhance communications between patients and on-site medical staffs in a non-verbal way. Moreover, art therapy could be more effective when combined with other forms of therapy such as music, dance and other sensory stimuli.

The medical mechanism underlying art therapy using painting as the medium for intervention remains largely unclear in the literature ( Salmon, 1993 ; Broadbent et al., 2004 ; Guillemin, 2004 ), and the evidence for effectiveness is insufficient ( Mirabella, 2015 ). Although a number of studies have shown that art therapy could improve the quality of life and mental health of patients, standard and rigorous clinical trials with large samples are still lacking. Moreover, the long-term effect is yet to be assessed due to the lack of follow-up assessment of art therapy.

In some cases, art therapy using painting as the medium may be difficult to be implemented in hospitals, due to medical and health regulations (may be partly due to potential of messes, lack of sink and cleaning space for proper disposal of paints, storage of paints, and toxins of allergens in the paint), insufficient space for the artwork to dry without getting in the way or getting damaged, and negative medical settings and family environments. Nevertheless, these difficulties can be overcome due to great benefits of the art therapy. We thus humbly believe that art therapy has great potential for mental disorders.

In the future, art therapy may be more thoroughly investigated in the following directions. First, more high-quality clinical trials should be carried out to gain more reliable and rigorous evidence. Second, the evaluation methods for the effectiveness of art therapy need to be as diverse as possible. It is necessary for the investigation to include not only subjective scale evaluations, but also objective means such as brain imaging and hematological examinations to be more convincing. Third, it will be helpful to specify the details of the art therapy and patients for objective comparisons, including types of diseases, painting methods, required qualifications of the therapist to perform the art therapy, and the theoretical basis and mechanism of the therapy. This practice should be continuously promoted in both hospitals and communities. Fourth, guidelines about art therapy should be gradually formed on the basis of accumulated evidence. Finally, mechanism of art therapy should be further investigated in a variety of ways, such as at the neurological, cellular, and molecular levels.

Author Contributions

JH designed the whole study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. JZ searched for selected the studies. LH participated in the interpretation of data. HY and JX offered good suggestions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

This study was financially supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2019YFC1712200), International standards research on clinical research and service of Acupuncture-Moxibustion (2019YFC1712205), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62006220), and Shenzhen Science and Technology Research Program (No. JCYJ20200109114816594).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbing, A., Ponstein, A., van Hooren, S., de Sonneville, L., Swaab, H., and Baars, E. (2018). The effectiveness of art therapy for anxiety in adults: a systematic review of randomised and non-randomised controlled trials. PLoS One 13:e208716. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208716

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Abdulah, D. M., and Abdulla, B. (2018). Effectiveness of group art therapy on quality of life in paediatric patients with cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 41, 180–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2018.09.020

Alvarenga, W. A., Leite, A., Oliveira, M. S., Nascimento, L. C., Silva-Rodrigues, F. M., Nunes, M. D. R., et al. (2018). The effect of music on the spirituality of patients: a systematic review. J. Holist. Nurs. 36, 192–204. doi: 10.1177/0898010117710855

American Art Therapy Association (2018). Definition of Art. Available online at: https://arttherapy.org/about-art-therapy/

Google Scholar

Andreasen, N. C., and Olsen, S. (1982). Negative v positive schizophrenia. Definition and validation. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 39, 789–794. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290070025006

Armstrong, V. G., and Howatson, R. (2015). Parent-infant art psychotherapy: a creative dyadic approach to early intervention. Infant Ment. Health J. 36, 213–222. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21504

Attard, A., and Larkin, M. (2016). Art therapy for people with psychosis: a narrative review of the literature. Lancet Psychiatry 3, 1067–1078. doi: 10.1016/s2215-0366(16)30146-8

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Babaei, S., Fatahi, B. S., Fakhri, M., Shahsavari, S., Parviz, A., Karbasfrushan, A., et al. (2020). Painting therapy versus anxiolytic premedication to reduce preoperative anxiety levels in children undergoing tonsillectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Indian J. Pediatr. 88, 190–191. doi: 10.1007/s12098-020-03430-9

Bar-Sela, G., Atid, L., Danos, S., Gabay, N., and Epelbaum, R. (2007). Art therapy improved depression and influenced fatigue levels in cancer patients on chemotherapy. Psychooncology 16, 980–984. doi: 10.1002/pon.1175

Birgitta, G. A., Wagman, P., Hedin, K., and Håkansson, C. (2018). Treatment of depression and/or anxiety–outcomes of a randomised controlled trial of the tree theme method ® versus regular occupational therapy. BMC Psychol. 6:25. doi: 10.1186/s40359-018-0237-0

British Association of Art Therapists (2015). What is Art Therapy? Available online at: https://www.baat.org/About-Art-Therapy

Broadbent, E., Petrie, K. J., Ellis, C. J., Ying, J., and Gamble, G. (2004). A picture of health–myocardial infarction patients’ drawings of their hearts and subsequent disability: a longitudinal study. J. Psychosom. Res. 57, 583–587.

Burton, A. (2009). Bringing arts-based therapies in from the scientific cold. Lancet Neurol. 8, 784–785. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(09)70216-9

Chiang, M., Reid-Varley, W. B., and Fan, X. (2019). Creative art therapy for mental illness. Psychiatry Res. 275, 129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.03.025

Ciasca, E. C., Ferreira, R. C., Santana, C.L. A., Forlenza, O. V., Dos Santos, G. D., Brum, P. S., et al. (2018). Art therapy as an adjuvant treatment for depression in elderly women: a randomized controlled trial. Braz. J. Psychiatry 40, 256–263. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2017-2250

Craig, J., and Baron-Cohen, S. (1999). Creativity and imagination in autism and Asperger syndrome. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 29, 319–326.

Craig, J., Baron-Cohen, S., and Scott, F. (2001). Drawing ability in autism: a window into the imagination. Isr. J. Psychiatry Relat. Sci. 38, 242–253.

Cramer, V., Torgersen, S., and Kringlen, E. (2005). Quality of life and anxiety disorders: a population study. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 193, 196–202. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000154836.22687.13

Crone, D. M., O’Connell, E. E., Tyson, P. J., Clark-Stone, F., Opher, S., and James, D. V. (2013). ‘Art Lift’ intervention to improve mental well-being: an observational study from U.K. general practice. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 22, 279–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2012.00862.x

Cuijpers, P., Vogelzangs, N., Twisk, J., Kleiboer, A., Li, J., and Penninx, B. W. (2014). Comprehensive meta-analysis of excess mortality in depression in the general community versus patients with specific illnesses. Am. J. Psychiatry 171, 453–462. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13030325

De Sousa, A., Shah, B., and Shrivastava, A. (2020). Suicide and Schizophrenia: an interplay of factors. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 22:65.

Demyttenaere, K., Bruffaerts, R., Posada-Villa, J., Gasquet, I., Kovess, V., Lepine, J. P., et al. (2004). Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA 291, 2581–2590. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2581

Deshmukh, S. R., Holmes, J., and Cardno, A. (2018). Art therapy for people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 9:D11073.

Emery, M. J. (2004). Art therapy as an intervention for Autism. Art Ther. Assoc. 21, 143–147. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2004.10129500

Evans, K., and Dubowski, J. (2001). Art Therapy with Children on the Autistic Spectrum: Beyond Words. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 113.

Faller, H., and Schmidt, M. (2004). Prognostic value of depressive coping and depression in survival of lung cancer patients. Psychooncology 13, 359–363. doi: 10.1002/pon.783

Forouzandeh, N., Drees, F., Forouzandeh, M., and Darakhshandeh, S. (2020). The effect of interactive games compared to painting on preoperative anxiety in Iranian children: a randomized clinical trial. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 40:101211. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2020.101211

Forzoni, S., Perez, M., Martignetti, A., and Crispino, S. (2010). Art therapy with cancer patients during chemotherapy sessions: an analysis of the patients’ perception of helpfulness. Palliat. Support. Care 8, 41–48. doi: 10.1017/s1478951509990691

Geschwind, D. H., and Levitt, P. (2007). Autism spectrum disorders: developmental disconnection syndromes. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 17, 103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.01.009

Geue, K., Richter, R., Buttstädt, M., Brähler, E., and Singer, S. (2013). An art therapy intervention for cancer patients in the ambulant aftercare–results from a non-randomised controlled study. Eur. J. Cancer Care (Engl.) 22, 345–352. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12037

Götze, H., Geue, K., Buttstädt, M., Singer, S., and Schwarz, R. (2009). [Art therapy for cancer patients in outpatient care. Psychological distress and coping of the participants]. Forsch. Komplementmed. 16, 28–33.

Guillemin, M. (2004). Understanding illness: using drawings as a research method. Qual. Health Res. 14, 272–289. doi: 10.1177/1049732303260445

Gussak, D. (2007). The effectiveness of art therapy in reducing depression in prison populations. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol 51, 444–460. doi: 10.1177/0306624x06294137

Hamer, M., Chida, Y., and Molloy, G. J. (2009). Psychological distress and cancer mortality. J. Psychosom. Res. 66, 255–258. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.11.002

Hattori, H., Hattori, C., Hokao, C., Mizushima, K., and Mase, T. (2011). Controlled study on the cognitive and psychological effect of coloring and drawing in mild Alzheimer’s disease patients. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 11, 431–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2011.00698.x

Heymann, P., Gienger, R., Hett, A., Müller, S., Laske, C., Robens, S., et al. (2018). Early detection of Alzheimer’s disease based on the patient’s creative drawing process: first results with a novel neuropsychological testing method. J. Alzheimers Dis. 63, 675–687. doi: 10.3233/jad-170946

Hongxia, M., Shuying, C., Chuqiao, F., Haiying, Z., Xuejiao, W., et al. (2013). Relationsle-title>Relationship between psychological state and house-tree-person drawing characteristics of rehabilitation patients with schizophrenia. Chin. Gen. Pract. 16, 2293–2295.

Relationship+between+psychological+state+and+house-tree-person+drawing+characteristics+of+rehabilitation+patients+with+schizophrenia%2E&journal=Chin%2E+Gen%2E+Pract%2E&author=Hongxia+M.&author=Shuying+C.&author=Chuqiao+F.&author=Haiying+Z.&author=Xuejiao+W.&publication_year=2013&volume=16&pages=2293–2295" target="_blank">Google Scholar

Hongyan, W., and JinJie, L. (2010). Rehabilitation effect of painting therapy on chronic schizophrenia. Chin. J. Health Psychol. 18, 1419–1420.

Jalambadani, Z. (2020). Art therapy based on painting therapy on the improvement of autistic children’s social interactions in Iran. Indian J. Psychiatry 62, 218–219. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.indianjpsychiatry_215_18

Jianhua, C., and Xiaolu, X. (2013). The experimental research on children with autism by intervening with painting therapy. J. Tangshan Teach. Coll. 35, 127–130.

Kenbubpha, K., Higgins, I., Chan, S. W., and Wilson, A. (2018). Promoting active ageing in older people with mental disorders living in the community: an integrative review. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 24:e12624. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12624

Kolliakou, A., Joseph, C., Ismail, K., Atakan, Z., and Murray, R. M. (2011). Why do patients with psychosis use cannabis and are they ready to change their use? Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 29, 335–346. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2010.11.006

Lee, J., Choi, M. Y., Kim, Y. B., Sun, J., Park, E. J., Kim, J. H., et al. (2017). Art therapy based on appreciation of famous paintings and its effect on distress among cancer patients. Qual. Life Res. 26, 707–715. doi: 10.1007/s11136-016-1473-5

Leevers, H. J., and Harris, P. L. (1998). Drawing impossible entities: a measure of the imagination in children with autism, children with learning disabilities, and normal 4-year-olds. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 39, 399–410. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00335

Lefèvre, C., Ledoux, M., and Filbet, M. (2016). Art therapy among palliative cancer patients: aesthetic dimensions and impacts on symptoms. Palliat. Support. Care 14, 376–380. doi: 10.1017/s1478951515001017

Legrand, A. P., Rivals, I., Richard, A., Apartis, E., Roze, E., Vidailhet, M., et al. (2017). New insight in spiral drawing analysis methods–application to action tremor quantification. Clin. Neurophysiol. 128, 1823–1834. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2017.07.002

Liebmann, M., and Weston, S. (2015). Art Therapy with Physical Conditions. Philadelphia, PA: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Lin, M. H., Moh, S. L., Kuo, Y. C., Wu, P. Y., Lin, C. L., Tsai, M. H., et al. (2012). Art therapy for terminal cancer patients in a hospice palliative care unit in Taiwan. Palliat. Support. Care 10, 51–57. doi: 10.1017/s1478951511000587

Low, J., Goddard, E., and Melser, J. (2009). Generativity and imagination in adisorder: evidence from individual differences in children’s impossible entity drawings. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 27, 425–444. doi: 10.1348/026151008x334728

Malchiodi, C. (2013). Art Therapy and Health Care. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Mannheim, E. G., Helmes, A., and Weis, J. (2013). [Dance/movement therapy in oncological rehabilitation]. Forsch. Komplementmed. 20, 33–41.

Martin, N. (2009). Art as an Early Intervention Tool for Children with Autism. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Mimica, N., and Kaliniæ, D. (2011). Art therapy may be benefitial for reducing stress–related behaviours in people with dementia–case report. Psychiatr. Danub. 23:125.

Min, J. (2010). Application of painting therapy in the rehabilitation period of schizophrenia. Med. J. Chin. Peoples Health 22, 2012–2014.

Mirabella, G. (2015). Is art therapy a reliable tool for rehabilitating people suffering from brain/mental diseases? J. Altern. Complement. Med. 21, 196–199. doi: 10.1089/acm.2014.0374

Montag, C., Haase, L., Seidel, D., Bayerl, M., Gallinat, J., Herrmann, U., et al. (2014). A pilot RCT of psychodynamic group art therapy for patients in acute psychotic episodes: feasibility, impact on symptoms and mentalising capacity. PLoS One 9:e112348. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112348

Nainis, N., Paice, J. A., Ratner, J., Wirth, J. H., Lai, J., and Shott, S. (2006). Relieving symptoms in cancer: innovative use of art therapy. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 31, 162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.07.006

Narme, P., Tonini, A., Khatir, F., Schiaratura, L., Clément, S., and Samson, S. (2012). [Non pharmacological treatment for Alzheimer’s disease: comparison between musical and non-musical interventions]. Geriatr. Psychol. Neuropsychiatr. Vieil. 10, 215–224. doi: 10.1684/pnv.2012.0343

Nielsen, S., Hageman, I., Petersen, A., Daniel, S. I. F., Lau, M., Winding, C., et al. (2019). Do emotion regulation, attentional control, and attachment style predict response to cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders?–An investigation in clinical settings. Psychother. Res. 29, 999–1009. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2018.1425933

Papangelo, P., Pinzino, M., Pelagatti, S., Fabbri-Destro, M., and Narzisi, A. (2020). Human figure drawings in children with autism spectrum disorders: a possible window on the inner or the outer world. Brain Sci. 10:398. doi: 10.3390/brainsci10060398

Petersen, R. C., Caracciolo, B., Brayne, C., Gauthier, S., Jelic, V., and Fratiglioni, L. (2014). Mild cognitive impairment: a concept in evolution. J. Intern. Med. 275, 214–228.

Pike, A. A. (2013). The effect of art therapy on cognitive performance among ethnically diverse older adults. J. Am. Art Ther. Assoc. 30, 159–168. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2014.847049

Pongan, E., Tillmann, B., Leveque, Y., Trombert, B., Getenet, J. C., Auguste, N., et al. (2017). Can musical or painting interventions improve chronic pain, mood, quality of life, and cognition in patients with mild Alzheimer’s disease? Evidence from a randomized controlled trial. J. Alzheimers Dis. 60, 663–677. doi: 10.3233/jad-170410

Richardson, P., Jones, K., Evans, C., Stevens, P., and Rowe, A. (2007). Exploratory RCT of art therapy as an adjunctive treatment in schizophrenia. J. Ment. Health 16, 483–491. doi: 10.1080/09638230701483111

Richardson, P., Jones, K., Evans, C., Stevens, P., and Rowe, A. (2009). Exploratory RCT of art therapy as an adjunctive treatment in schizophrenia. J Ment. Health 16, 483–491.

Ruiz, M. I., Aceituno, D., and Rada, G. (2017). Art therapy for schizophrenia? Medwave 17:e6845.

Runde, P. (2008). Clinical application of painting therapy in middle school students with mood disorders. Chin. J. Health Psychol. 27, 749–750.

Rusted, J., Sheppard, L., and Waller, D. A. (2016). Multi-centre randomized control group trial on the use of art therapy for older people with dementia. Group Anal. 39, 517–536. doi: 10.1177/0533316406071447

Salmon, P. L. (1993). Viewing the client’s world through drawings. J. Holist. Nurs. 11, 21–41. doi: 10.1177/089801019301100104

Steinbauer, M., and Taucher, J. (2001). [Paintings and their progress by psychiatric inpatients within the concept of integrative art therapy]. Wien. Med. Wochenschr. 151, 375–379.

Steinbauer, M., Taucher, J., and Zapotoczky, H. G. (1999). [Integrative painting therapy. A therapeutic concept for psychiatric inpatients at the University clinic in Graz]. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 111, 525–532.

Teglbjaerg, H. S. (2011). Art therapy may reduce psychopathology in schizophrenia by strengthening the patients’ sense of self: a qualitative extended case report. Psychopathology 44, 314–318. doi: 10.1159/000325025

Ten, E. K., and Muller, U. (2018). Drawing links between the autism cognitive profile and imagination: executive function and processing bias in imaginative drawings by children with and without autism. Autism 22, 149–160. doi: 10.1177/1362361316668293

Thyme, K. E., Sundin, E. C., Wiberg, B., Oster, I., Aström, S., and Lindh, J. (2009). Individual brief art therapy can be helpful for women with breast cancer: a randomized controlled clinical study. Palliat. Support. Care 7, 87–95. doi: 10.1017/s147895150900011x

Tong, J., Yu, W., Fan, X., Sun, X., Zhang, J., Zhang, J., et al. (2020). Impact of group art therapy using traditional Chinese materials on self-efficacy and social function for individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia. Front. Psychol. 11:571124. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.571124

van Geffen, E. C., van der Wal, S. W., van Hulten, R., de Groot, M. C., Egberts, A. C., and Heerdink, E. R. (2007). Evaluation of patients’ experiences with antidepressants reported by means of a medicine reporting system. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 63, 1193–1199. doi: 10.1007/s00228-007-0375-4

Wang, Y., Jiepeng, L., Aihua, Z., Runjuan, M., and Lei, Z. (2011). Study on the application value of painting therapy in the treatment of depression. Med. J. Chin. Peoples Health 23, 1974–1976.

Wen, Z., and Zhaoming, G. (2009). A preliminary attempt of painting art therapy for autistic children. Inner Mongol. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 28, 24–25.

Whiteford, H. A., Degenhardt, L., Rehm, J., Baxter, A. J., Ferrari, A. J., Erskine, H. E., et al. (2013). Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 382, 1575–1586. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)61611-6

Wilk, M., Pachalska, M., Lipowska, M., Herman-Sucharska, I., Makarowski, R., Mirski, A., et al. (2010). Speech intelligibility in cerebral palsy children attending an art therapy program. Med. Sci. Monit. 16, R222–R231.

Witkoski, S. A., and Chaves, M. (2007). Evaluation of artwork produced by Alzheimer’s disease outpatients in a pilot art therapy program. Dement. Neuropsychol. 1, 217–221. doi: 10.1590/s1980-57642008dn10200016

Xu, G., Chen, G., Zhou, Q., Li, N., and Zheng, X. (2017). Prevalence of mental disorders among older Chinese people in Tianjin City. Can. J. Psychiatry 62, 778–786. doi: 10.1177/0706743717727241

Yu, J., Rawtaer, I., Goh, L. G., Kumar, A. P., Feng, L., Kua, E. H., et al. (2021). The art of remediating age-related cognitive decline: art therapy enhances cognition and increases cortical thickness in mild cognitive impairment. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 27, 79–88. doi: 10.1017/s1355617720000697

Zhenhai, N., and Yunhua, C. (2011). An experimental study on the improvement of depression in Obese female college students by painting therapy. Chin. J. Sch. Health 32, 558–559.

Zschucke, E., Gaudlitz, K., and Strohle, A. (2013). Exercise and physical activity in mental disorders: clinical and experimental evidence. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 46(Suppl. 1) S12–S21.

Keywords : painting, art therapy, mental disorders, clinical applications, medical interventions

Citation: Hu J, Zhang J, Hu L, Yu H and Xu J (2021) Art Therapy: A Complementary Treatment for Mental Disorders. Front. Psychol. 12:686005. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.686005

Received: 26 March 2021; Accepted: 28 July 2021; Published: 12 August 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Hu, Zhang, Hu, Yu and Xu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jinping Xu, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What to Know About Music Therapy

Music can help improve your mood and overall mental health.

Steven Gans, MD is board-certified in psychiatry and is an active supervisor, teacher, and mentor at Massachusetts General Hospital.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/steven-gans-1000-51582b7f23b6462f8713961deb74959f.jpg)

Verywell / Lara Antal

Effectiveness

Things to consider, how to get started.

Music therapy is a therapeutic approach that uses the naturally mood-lifting properties of music to help people improve their mental health and overall well-being. It’s a goal-oriented intervention that may involve:

- Making music

- Writing songs

- Listening to music

- Discussing music

This form of treatment may be helpful for people with depression and anxiety, and it may help improve the quality of life for people with physical health problems. Anyone can engage in music therapy; you don’t need a background in music to experience its beneficial effects.

Types of Music Therapy

Music therapy can be an active process, where clients play a role in creating music, or a passive one that involves listening or responding to music. Some therapists may use a combined approach that involves both active and passive interactions with music.

There are a variety of approaches established in music therapy, including:

- Analytical music therapy : Analytical music therapy encourages you to use an improvised, musical "dialogue" through singing or playing an instrument to express your unconscious thoughts, which you can reflect on and discuss with your therapist afterward.

- Benenzon music therapy : This format combines some concepts of psychoanalysis with the process of making music. Benenzon music therapy includes the search for your "musical sound identity," which describes the external sounds that most closely match your internal psychological state.

- Cognitive behavioral music therapy (CBMT) : This approach combines cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) with music. In CBMT, music is used to reinforce some behaviors and modify others. This approach is structured, not improvisational, and may include listening to music, dancing, singing, or playing an instrument.

- Community music therapy : This format is focused on using music as a way to facilitate change on the community level. It’s done in a group setting and requires a high level of engagement from each member.

- Nordoff-Robbins music therapy : Also called creative music therapy, this method involves playing an instrument (often a cymbal or drum) while the therapist accompanies using another instrument. The improvisational process uses music as a way to help enable self-expression.

- The Bonny method of guided imagery and music (GIM) : This form of therapy uses classical music as a way to stimulate the imagination. In this method, you explain the feelings, sensations, memories, and imagery you experience while listening to the music.

- Vocal psychotherapy : In this format, you use various vocal exercises, natural sounds, and breathing techniques to connect with your emotions and impulses. This practice is meant to create a deeper sense of connection with yourself.

Get Help Now

We've tried, tested, and written unbiased reviews of the best online therapy programs including Talkspace, BetterHelp, and ReGain. Find out which option is the best for you.

Music Therapy vs. Sound Therapy

Music therapy and sound therapy (or sound healing ) are distinctive, and each approach has its own goals, protocols, tools, and settings:

- Music therapy is a relatively new discipline, while sound therapy is based on ancient Tibetan cultural practices .

- Sound therapy uses tools to achieve specific sound frequencies, while music therapy focuses on addressing symptoms like stress and pain.

- The training and certifications that exist for sound therapy are not as standardized as those for music therapists.

- Music therapists often work in hospitals, substance abuse treatment centers, or private practices, while sound therapists may offer their service as a component of complementary or alternative medicine.

When you begin working with a music therapist, you will start by identifying your goals. For example, if you’re experiencing depression, you may hope to use music to naturally improve your mood and increase your happiness . You may also want to try applying music therapy to other symptoms of depression like anxiety, insomnia, or trouble focusing.

During a music therapy session, you may listen to different genres of music , play a musical instrument, or even compose your own songs. You may be asked to sing or dance. Your therapist may encourage you to improvise, or they may have a set structure for you to follow.

You may be asked to tune in to your emotions as you perform these tasks or to allow your feelings to direct your actions. For example, if you are angry, you might play or sing loud, fast, and dissonant chords.

You may also use music to explore ways to change how you feel. If you express anger or stress, your music therapist might respond by having you listen to or create music with slow, soft, soothing tones.

Music therapy is often one-on-one, but you may also choose to participate in group sessions if they are available. Sessions with a music therapist take place wherever they practice, which might be a:

- Community health center

- Correctional facility

- Private office

- Physical therapy practice

- Rehabilitation facility

Wherever it happens to be, the room you work in together will be a calm environment with no outside distractions.

What Music Therapy Can Help With

Music therapy may be helpful for people experiencing:

- Alzheimer’s disease

- Anxiety or stress

- Cardiac conditions

- Chronic pain

- Difficulties with verbal and nonverbal communication

- Emotional dysregulation

- Feelings of low self-esteem

- Impulsivity

- Negative mood

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- Problems related to childbirth

- Rehabilitation after an injury or medical procedure

- Respiration problems

- Substance use disorders

- Surgery-related issues

- Traumatic brain injury (TBI)

- Trouble with movement or coordination

Research also suggests that it can be helpful for people with:

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

- Schizophrenia

- Stroke and neurological disorders

Music therapy is also often used to help children and adolescents:

- Develop their identities

- Improve their communication skills

- Learn to regulate their emotions

- Recover from trauma

- Self-reflect

Benefits of Using Music as Therapy

Music therapy can be highly personalized, making it suitable for people of any age—even very young children can benefit. It’s also versatile and offers benefits for people with a variety of musical experience levels and with different mental or physical health challenges.

Engaging with music can:

- Activate regions of the brain that influence things like memory, emotions, movement, sensory relay, some involuntary functions, decision-making, and reward

- Fulfill social needs for older adults in group settings

- Lower heart rate and blood pressure

- Relax muscle tension

- Release endorphins

- Relieve stress and encourage feelings of calm

- Strengthen motor skills and improve communication for children and young adults who have developmental and/or learning disabilities

Research has also shown that music can have a powerful effect on people with dementia and other memory-related disorders.

Overall, music therapy can increase positive feelings, like:

- Confidence and empowerment

- Emotional intimacy

The uses and benefits of music therapy have been researched for decades. Key findings from clinical studies have shown that music therapy may be helpful for people with depression and anxiety, sleep disorders, and even cancer.

Depression

Studies have shown that music therapy can be an effective component of depression treatment. According to the research cited, the use of music therapy was most beneficial to people with depression when it was combined with the usual treatments (such as antidepressants and psychotherapy).

When used in combination with other forms of treatment, music therapy may also help reduce obsessive thoughts , depression, and anxiety in people with OCD.

In 2016, researchers conducted a feasibility study that explored how music therapy could be combined with CBT to treat depression . While additional research is needed, the initial results were promising.

Many people find that music, or even white noise, helps them fall asleep. Research has shown that music therapy may be helpful for people with sleep disorders or insomnia as a symptom of depression.

Compared to pharmaceuticals and other commonly prescribed treatments for sleep disorders, music is less invasive, more affordable, and something a person can do on their own to self-manage their condition.

Pain Management

Music has been explored as a potential strategy for acute and chronic pain management in all age groups. Research has shown that listening to music when healing from surgery or an injury, for example, may help both kids and adults cope with physical pain.

Music therapy may help reduce pain associated with:

- Chronic conditions : Music therapy can be part of a long-term plan for managing chronic pain, and it may help people recapture and focus on positive memories from a time before they had distressing long-term pain symptoms.

- Labor and childbirth : Music therapy-assisted childbirth appears to be a positive, accessible, non-pharmacological option for pain management and anxiety reduction for laboring people.

- Surgery : When paired with standard post-operative hospital care, music therapy is an effective way to lower pain levels, anxiety, heart rate, and blood pressure in people recovering from surgery.

Coping with a cancer diagnosis and going through cancer treatment is as much an emotional experience as a physical one. People with cancer often need different sources of support to take care of their emotional and spiritual well-being.

Music therapy has been shown to help reduce anxiety in people with cancer who are starting radiation treatments. It may also help them cope with the side effects of chemotherapy, such as nausea.

Music therapy may also offer emotional benefits for people experiencing depression after receiving their cancer diagnosis, while they’re undergoing treatment, or even after remission.

On its own, music therapy may not constitute adequate treatment for medical conditions, including mental health disorders . However, when combined with medication, psychotherapy , and other interventions, it can be a valuable component of a treatment plan.

If you have difficulty hearing, wear a hearing aid, or have a hearing implant, you should talk with your audiologist before undergoing music therapy to ensure that it’s safe for you.

Similarly, music therapy that incorporates movement or dancing may not be a good fit if you’re experiencing pain, illness, injury, or a physical condition that makes it difficult to exercise.

You'll also want to check your health insurance benefits prior to starting music therapy. Your sessions may be covered or reimbursable under your plan, but you may need a referral from your doctor.

If you’d like to explore music therapy, talk to your doctor or therapist. They can connect you with practitioners in your community. The American Music Therapy Association (AMTA) also maintains a database of board-certified, credentialed professionals that you can use to find a practicing music therapist in your area.

Depending on your goals, a typical music therapy session lasts between 30 and 50 minutes. Much like you would plan sessions with a psychotherapist, you may choose to have a set schedule for music therapy—say, once a week—or you may choose to work with a music therapist on a more casual "as-needed" basis.

Before your first session, you may want to talk things over with your music therapist so you know what to expect and can check in with your primary care physician if needed.

Aigen KS. The Study of Music Therapy: Current Issues and Concepts . Routledge & CRC Press. New York; 2013. doi:10.4324/9781315882703

Jasemi M, Aazami S, Zabihi RE. The effects of music therapy on anxiety and depression of cancer patients . Indian J Palliat Care . 2016;22(4):455-458. doi:10.4103/0973-1075.191823

Chung J, Woods-Giscombe C. Influence of dosage and type of music therapy in symptom management and rehabilitation for individuals with schizophrenia . Issues Ment Health Nurs . 2016;37(9):631-641. doi:10.1080/01612840.2016.1181125

MacDonald R, Kreutz G, Mitchell L. Music, Health, and Wellbeing . Oxford; 2012. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199586974.001.0001

Monti E, Austin D. The dialogical self in vocal psychotherapy . Nord J Music Ther . 2018;27(2):158-169. doi:10.1080/08098131.2017.1329227

American Music Therapy Association (AMTA). Music therapy with specific populations: Fact sheets, resources & bibliographies .

Wang CF, Sun YL, Zang HX. Music therapy improves sleep quality in acute and chronic sleep disorders: A meta-analysis of 10 randomized studies . Int J Nurs Stud . 2014;51(1):51-62. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.03.008

Bidabadi SS, Mehryar A. Music therapy as an adjunct to standard treatment for obsessive compulsive disorder and co-morbid anxiety and depression: A randomized clinical trial . J Affect Disord . 2015;184:13-7. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2015.04.011

Kamioka H, Tsutani K, Yamada M, et al. Effectiveness of music therapy: A summary of systematic reviews based on randomized controlled trials of music interventions . Patient Prefer Adherence . 2014;8:727-754. doi:10.2147/PPA.S61340

Raglio A, Attardo L, Gontero G, Rollino S, Groppo E, Granieri E. Effects of music and music therapy on mood in neurological patients . World J Psychiatry . 2015;5(1):68-78. doi:10.5498/wjp.v5.i1.68

Altenmüller E, Schlaug G. Apollo’s gift: New aspects of neurologic music therapy . Prog Brain Res . 2015;217:237-252. doi:10.1016/bs.pbr.2014.11.029

Werner J, Wosch T, Gold C. Effectiveness of group music therapy versus recreational group singing for depressive symptoms of elderly nursing home residents: Pragmatic trial . Aging Ment Health . 2017;21(2):147-155. doi:10.1080/13607863.2015.1093599

Dunbar RIM, Kaskatis K, MacDonald I, Barra V. Performance of music elevates pain threshold and positive affect: Implications for the evolutionary function of music . Evol Psychol . 2012;10(4):147470491201000420. doi:10.1177/147470491201000403

Pavlicevic M, O'neil N, Powell H, Jones O, Sampathianaki E. Making music, making friends: Long-term music therapy with young adults with severe learning disabilities . J Intellect Disabil . 2014;18(1):5-19. doi:10.1177/1744629513511354

Chang YS, Chu H, Yang CY, et al. The efficacy of music therapy for people with dementia: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials . J Clin Nurs . 2015;24(23-24):3425-40. doi:10.1111/jocn.12976

Aalbers S, Fusar-Poli L, Freeman RE, et al. Music therapy for depression . Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2017;11:CD004517. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004517.pub3

Trimmer C, Tyo R, Naeem F. Cognitive behavioural therapy-based music (CBT-music) group for symptoms of anxiety and depression . Can J Commun Ment Health . 2016;35(2):83-87. doi:10.7870/cjcmh-2016-029

Jespersen KV, Koenig J, Jennum P, Vuust P. Music for insomnia in adults . Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2015;(8):CD010459. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010459.pub2

Redding J, Plaugher S, Cole J, et al. "Where's the Music?" Using music therapy for pain management . Fed Pract . 2016;33(12):46-49.

Novotney A. Music as medicine . Monitor on Psychology . 2013;44(10):46.

McCaffrey T, Cheung PS, Barry M, Punch P, Dore L. The role and outcomes of music listening for women in childbirth: An integrative review . Midwifery . 2020;83:102627. doi:10.1016/j.midw.2020.102627

Liu Y, Petrini MA. Effects of music therapy on pain, anxiety, and vital signs in patients after thoracic surgery . Complement Ther Med . 2015;23(5):714-8.doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2015.08.002

Rossetti A, Chadha M, Torres BN, et al. The impact of music therapy on anxiety in cancer patients undergoing simulation for radiation therapy . Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys . 2017;99(1):103-110. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2017.05.003

American Music Therapy Association (AMTA). Guidance for music listening programs .

What Is Art Therapy?

Understand arts efficacy and place in therapy..

Posted April 9, 2024 | Reviewed by Ray Parker

- What Is Therapy?

- Find a therapist near me

- Art therapy is often coupled with psychotherapy as part of an integrative approach to therapy.

- Art can provide patients who struggle to verbalize trauma or emotions with alternative means of communication.

- Studies have found that art therapy can help with symptoms of anxiety and depression in some populations.

Art therapy is defined by the American Art Therapy Association as utilizing “active art-making, the creative process, and applied psychological theory—within a psychotherapeutic relationship—to enrich the lives of individuals, families, and communities.” Often practiced in tandem with psychotherapy , art therapy is nonpharmacological and can be used as a medical intervention for mental disorders. Art therapy is an integrative practice, as it encourages alternative methods of communication and expression. In doing so, art therapy is also capable of helping “ to improve cognitive and sensorimotor functions, foster self-esteem and self-awareness, cultivate emotional resilience , promote insight, enhance social skills, reduce and resolve conflicts and distress, and advance societal and ecological change.” There are many different ways of participating in art therapy, such as dance movement psychotherapy, music therapy, and drawing, painting, and craft therapy.

The History of Art Therapy

For most of human history, art has been an important method of communicating events, ideas, and stories. Closely connected to the expression of emotions, the term “art therapy” first emerged in 1942 when patients suffering from tuberculosis found freedom through drawing and painting. Art therapy practices soon moved into the mental health realm with the foundation of the British Association of Art Therapists in 1964. As art therapy gained traction around the world, it was implemented alongside child psychotherapy. The creation of art helped children express their feelings despite their “ underdeveloped or limited vocabulary .” It quickly became a treatment for patients with trauma , grief , anxiety , and a range of other mental health disorders.

The Efficacy of Art Therapy

In 2022, a report was produced by the Australian, New Zealand, and Asian Creative Arts Therapies Association called The Proven Efficacy of Creative Arts Therapies: What the Literature Tells Us . Created by Deanna Gray, the report is a compilation of over 40 peer-reviewed research articles that center around the use of creative arts as therapy. The library of research supporting the efficacy of art therapy has only continued to grow in the years since the report was published. One such study led by Khadeja Alwledat found that just four sessions of creative art therapy had a statistically significant positive impact on the levels of depression , anxiety, and stress of the participants, all of whom were within three months post-stroke diagnosis. This wide array of research behind art therapy is accompanied by the establishment of initiatives, such as the NeuroArts Blueprint, and outreach projects like the University of Michigan’s Prison Creative Arts Project.

The Blueprint is an interdisciplinary initiative that is working to “break new ground at the crossroads of science, the arts, and technology.” It is building a community of individuals and organizations who are invested in advancing the use of arts and aesthetic experiences as tools to improve health and well-being. In 2021, the Blueprint was released as an “authoritative, first-of-its-kind roadmap” to advance brain science research, policy, and funding and to catalyze and mobilize “the full power of art.”

Along with the Blueprint, some institutions have begun creating projects to acknowledge the efficacy of art therapy, as well as promote the use of art therapy across their campuses. The Prison Creative Arts Project at the University of Michigan is a program within the Residential College that provides academic training in “issues surrounding incarceration and practical skills in the arts.” This project sends a newsletter to over 1,800 recipients, informing them of upcoming programs and events. By reaching out to those impacted by the justice system and bringing them together with the University of Michigan community, the Prison Creative Arts Project promotes “artistic collaboration , mutual learning, and growth.”

How to Become an Art Therapist

In order to become an art therapist, one must complete a master’s degree in a related field, become board-certified through the Art Therapy Credentials Board , and complete “100 hours of supervised work along with 600 hours of a clinical internship.” Students looking to become art therapists must take graduate-level courses in topics such as the creative process, psychological development, psychodiagnostics, and art therapy assessment. Beyond this, they will also receive training in studio art methods such as drawing, painting, and sculpture. Students should choose a program that is approved by the Commission on the Accreditation of Allied Health Education Programs (CAAHEP) or the American Art Therapy Association (AATA). These well-renowned programs enable students to pursue national credentialing and licensure after graduation.

At its core, a degree in art therapy is a research-based discipline that “combines active art-making, the creative process, applied psychological theory, and the human experience within a psychotherapeutic relationship.” These hours of training provide art therapists with the ability to work with diverse populations and to support their clients through a wide range of challenges.

Searching for an Art Therapist

When looking for an art therapist as a patient, first make sure that the individual has completed either a CAAHEP-accredited or AATA-approved program. From there, choosing an art therapist is a matter of personal preference. Generally, the first time that you meet with an art therapist will be similar to any therapy intake session: they will ask you multiple questions about your background and experiences, and you will have the opportunity to ask them any questions, as well. You will want to choose someone with whom you feel comfortable and at ease. It is completely acceptable not to schedule another session with a therapist if there is something you do not like. Keep in mind that going to see an art therapist is meant to benefit you solely; thus, the choice is entirely yours.

Encouraging Art Therapy

For therapists, the question of whether it makes clinical sense to encourage a patient to look into art therapy depends on a variety of factors. If the patient struggles to verbalize trauma, art therapy may provide them with a better means of communication. As another example, if a patient is evasive and artistically inclined, allowing them to express themselves through art may help break down barriers, allowing them to become more cooperative.