- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Research Summary – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Research Summary – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Research Summary

Definition:

A research summary is a brief and concise overview of a research project or study that highlights its key findings, main points, and conclusions. It typically includes a description of the research problem, the research methods used, the results obtained, and the implications or significance of the findings. It is often used as a tool to quickly communicate the main findings of a study to other researchers, stakeholders, or decision-makers.

Structure of Research Summary

The Structure of a Research Summary typically include:

- Introduction : This section provides a brief background of the research problem or question, explains the purpose of the study, and outlines the research objectives.

- Methodology : This section explains the research design, methods, and procedures used to conduct the study. It describes the sample size, data collection methods, and data analysis techniques.

- Results : This section presents the main findings of the study, including statistical analysis if applicable. It may include tables, charts, or graphs to visually represent the data.

- Discussion : This section interprets the results and explains their implications. It discusses the significance of the findings, compares them to previous research, and identifies any limitations or future directions for research.

- Conclusion : This section summarizes the main points of the research and provides a conclusion based on the findings. It may also suggest implications for future research or practical applications of the results.

- References : This section lists the sources cited in the research summary, following the appropriate citation style.

How to Write Research Summary

Here are the steps you can follow to write a research summary:

- Read the research article or study thoroughly: To write a summary, you must understand the research article or study you are summarizing. Therefore, read the article or study carefully to understand its purpose, research design, methodology, results, and conclusions.

- Identify the main points : Once you have read the research article or study, identify the main points, key findings, and research question. You can highlight or take notes of the essential points and findings to use as a reference when writing your summary.

- Write the introduction: Start your summary by introducing the research problem, research question, and purpose of the study. Briefly explain why the research is important and its significance.

- Summarize the methodology : In this section, summarize the research design, methods, and procedures used to conduct the study. Explain the sample size, data collection methods, and data analysis techniques.

- Present the results: Summarize the main findings of the study. Use tables, charts, or graphs to visually represent the data if necessary.

- Interpret the results: In this section, interpret the results and explain their implications. Discuss the significance of the findings, compare them to previous research, and identify any limitations or future directions for research.

- Conclude the summary : Summarize the main points of the research and provide a conclusion based on the findings. Suggest implications for future research or practical applications of the results.

- Revise and edit : Once you have written the summary, revise and edit it to ensure that it is clear, concise, and free of errors. Make sure that your summary accurately represents the research article or study.

- Add references: Include a list of references cited in the research summary, following the appropriate citation style.

Example of Research Summary

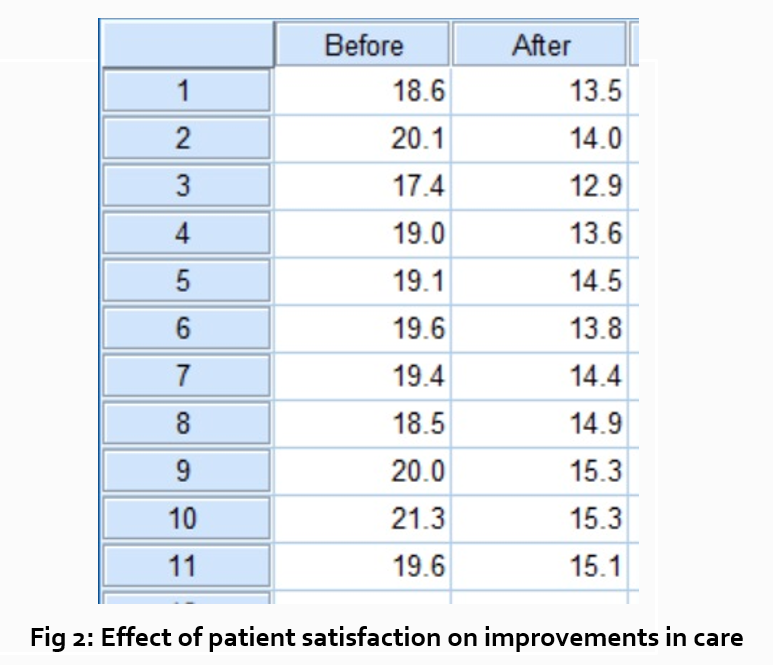

Here is an example of a research summary:

Title: The Effects of Yoga on Mental Health: A Meta-Analysis

Introduction: This meta-analysis examines the effects of yoga on mental health. The study aimed to investigate whether yoga practice can improve mental health outcomes such as anxiety, depression, stress, and quality of life.

Methodology : The study analyzed data from 14 randomized controlled trials that investigated the effects of yoga on mental health outcomes. The sample included a total of 862 participants. The yoga interventions varied in length and frequency, ranging from four to twelve weeks, with sessions lasting from 45 to 90 minutes.

Results : The meta-analysis found that yoga practice significantly improved mental health outcomes. Participants who practiced yoga showed a significant reduction in anxiety and depression symptoms, as well as stress levels. Quality of life also improved in those who practiced yoga.

Discussion : The findings of this study suggest that yoga can be an effective intervention for improving mental health outcomes. The study supports the growing body of evidence that suggests that yoga can have a positive impact on mental health. Limitations of the study include the variability of the yoga interventions, which may affect the generalizability of the findings.

Conclusion : Overall, the findings of this meta-analysis support the use of yoga as an effective intervention for improving mental health outcomes. Further research is needed to determine the optimal length and frequency of yoga interventions for different populations.

References :

- Cramer, H., Lauche, R., Langhorst, J., Dobos, G., & Berger, B. (2013). Yoga for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Depression and anxiety, 30(11), 1068-1083.

- Khalsa, S. B. (2004). Yoga as a therapeutic intervention: a bibliometric analysis of published research studies. Indian journal of physiology and pharmacology, 48(3), 269-285.

- Ross, A., & Thomas, S. (2010). The health benefits of yoga and exercise: a review of comparison studies. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 16(1), 3-12.

Purpose of Research Summary

The purpose of a research summary is to provide a brief overview of a research project or study, including its main points, findings, and conclusions. The summary allows readers to quickly understand the essential aspects of the research without having to read the entire article or study.

Research summaries serve several purposes, including:

- Facilitating comprehension: A research summary allows readers to quickly understand the main points and findings of a research project or study without having to read the entire article or study. This makes it easier for readers to comprehend the research and its significance.

- Communicating research findings: Research summaries are often used to communicate research findings to a wider audience, such as policymakers, practitioners, or the general public. The summary presents the essential aspects of the research in a clear and concise manner, making it easier for non-experts to understand.

- Supporting decision-making: Research summaries can be used to support decision-making processes by providing a summary of the research evidence on a particular topic. This information can be used by policymakers or practitioners to make informed decisions about interventions, programs, or policies.

- Saving time: Research summaries save time for researchers, practitioners, policymakers, and other stakeholders who need to review multiple research studies. Rather than having to read the entire article or study, they can quickly review the summary to determine whether the research is relevant to their needs.

Characteristics of Research Summary

The following are some of the key characteristics of a research summary:

- Concise : A research summary should be brief and to the point, providing a clear and concise overview of the main points of the research.

- Objective : A research summary should be written in an objective tone, presenting the research findings without bias or personal opinion.

- Comprehensive : A research summary should cover all the essential aspects of the research, including the research question, methodology, results, and conclusions.

- Accurate : A research summary should accurately reflect the key findings and conclusions of the research.

- Clear and well-organized: A research summary should be easy to read and understand, with a clear structure and logical flow.

- Relevant : A research summary should focus on the most important and relevant aspects of the research, highlighting the key findings and their implications.

- Audience-specific: A research summary should be tailored to the intended audience, using language and terminology that is appropriate and accessible to the reader.

- Citations : A research summary should include citations to the original research articles or studies, allowing readers to access the full text of the research if desired.

When to write Research Summary

Here are some situations when it may be appropriate to write a research summary:

- Proposal stage: A research summary can be included in a research proposal to provide a brief overview of the research aims, objectives, methodology, and expected outcomes.

- Conference presentation: A research summary can be prepared for a conference presentation to summarize the main findings of a study or research project.

- Journal submission: Many academic journals require authors to submit a research summary along with their research article or study. The summary provides a brief overview of the study’s main points, findings, and conclusions and helps readers quickly understand the research.

- Funding application: A research summary can be included in a funding application to provide a brief summary of the research aims, objectives, and expected outcomes.

- Policy brief: A research summary can be prepared as a policy brief to communicate research findings to policymakers or stakeholders in a concise and accessible manner.

Advantages of Research Summary

Research summaries offer several advantages, including:

- Time-saving: A research summary saves time for readers who need to understand the key findings and conclusions of a research project quickly. Rather than reading the entire research article or study, readers can quickly review the summary to determine whether the research is relevant to their needs.

- Clarity and accessibility: A research summary provides a clear and accessible overview of the research project’s main points, making it easier for readers to understand the research without having to be experts in the field.

- Improved comprehension: A research summary helps readers comprehend the research by providing a brief and focused overview of the key findings and conclusions, making it easier to understand the research and its significance.

- Enhanced communication: Research summaries can be used to communicate research findings to a wider audience, such as policymakers, practitioners, or the general public, in a concise and accessible manner.

- Facilitated decision-making: Research summaries can support decision-making processes by providing a summary of the research evidence on a particular topic. Policymakers or practitioners can use this information to make informed decisions about interventions, programs, or policies.

- Increased dissemination: Research summaries can be easily shared and disseminated, allowing research findings to reach a wider audience.

Limitations of Research Summary

Limitations of the Research Summary are as follows:

- Limited scope: Research summaries provide a brief overview of the research project’s main points, findings, and conclusions, which can be limiting. They may not include all the details, nuances, and complexities of the research that readers may need to fully understand the study’s implications.

- Risk of oversimplification: Research summaries can be oversimplified, reducing the complexity of the research and potentially distorting the findings or conclusions.

- Lack of context: Research summaries may not provide sufficient context to fully understand the research findings, such as the research background, methodology, or limitations. This may lead to misunderstandings or misinterpretations of the research.

- Possible bias: Research summaries may be biased if they selectively emphasize certain findings or conclusions over others, potentially distorting the overall picture of the research.

- Format limitations: Research summaries may be constrained by the format or length requirements, making it challenging to fully convey the research’s main points, findings, and conclusions.

- Accessibility: Research summaries may not be accessible to all readers, particularly those with limited literacy skills, visual impairments, or language barriers.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and...

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

How To Write A Research Summary

It’s a common perception that writing a research summary is a quick and easy task. After all, how hard can jotting down 300 words be? But when you consider the weight those 300 words carry, writing a research summary as a part of your dissertation, essay or compelling draft for your paper instantly becomes daunting task.

A research summary requires you to synthesize a complex research paper into an informative, self-explanatory snapshot. It needs to portray what your article contains. Thus, writing it often comes at the end of the task list.

Regardless of when you’re planning to write, it is no less of a challenge, particularly if you’re doing it for the first time. This blog will take you through everything you need to know about research summary so that you have an easier time with it.

What is a Research Summary?

A research summary is the part of your research paper that describes its findings to the audience in a brief yet concise manner. A well-curated research summary represents you and your knowledge about the information written in the research paper.

While writing a quality research summary, you need to discover and identify the significant points in the research and condense it in a more straightforward form. A research summary is like a doorway that provides access to the structure of a research paper's sections.

Since the purpose of a summary is to give an overview of the topic, methodology, and conclusions employed in a paper, it requires an objective approach. No analysis or criticism.

Research summary or Abstract. What’s the Difference?

They’re both brief, concise, and give an overview of an aspect of the research paper. So, it’s easy to understand why many new researchers get the two confused. However, a research summary and abstract are two very different things with individual purpose. To start with, a research summary is written at the end while the abstract comes at the beginning of a research paper.

A research summary captures the essence of the paper at the end of your document. It focuses on your topic, methods, and findings. More like a TL;DR, if you will. An abstract, on the other hand, is a description of what your research paper is about. It tells your reader what your topic or hypothesis is, and sets a context around why you have embarked on your research.

Getting Started with a Research Summary

Before you start writing, you need to get insights into your research’s content, style, and organization. There are three fundamental areas of a research summary that you should focus on.

- While deciding the contents of your research summary, you must include a section on its importance as a whole, the techniques, and the tools that were used to formulate the conclusion. Additionally, there needs to be a short but thorough explanation of how the findings of the research paper have a significance.

- To keep the summary well-organized, try to cover the various sections of the research paper in separate paragraphs. Besides, how the idea of particular factual research came up first must be explained in a separate paragraph.

- As a general practice worldwide, research summaries are restricted to 300-400 words. However, if you have chosen a lengthy research paper, try not to exceed the word limit of 10% of the entire research paper.

How to Structure Your Research Summary

The research summary is nothing but a concise form of the entire research paper. Therefore, the structure of a summary stays the same as the paper. So, include all the section titles and write a little about them. The structural elements that a research summary must consist of are:

It represents the topic of the research. Try to phrase it so that it includes the key findings or conclusion of the task.

The abstract gives a context of the research paper. Unlike the abstract at the beginning of a paper, the abstract here, should be very short since you’ll be working with a limited word count.

Introduction

This is the most crucial section of a research summary as it helps readers get familiarized with the topic. You should include the definition of your topic, the current state of the investigation, and practical relevance in this part. Additionally, you should present the problem statement, investigative measures, and any hypothesis in this section.

Methodology

This section provides details about the methodology and the methods adopted to conduct the study. You should write a brief description of the surveys, sampling, type of experiments, statistical analysis, and the rationality behind choosing those particular methods.

Create a list of evidence obtained from the various experiments with a primary analysis, conclusions, and interpretations made upon that. In the paper research paper, you will find the results section as the most detailed and lengthy part. Therefore, you must pick up the key elements and wisely decide which elements are worth including and which are worth skipping.

This is where you present the interpretation of results in the context of their application. Discussion usually covers results, inferences, and theoretical models explaining the obtained values, key strengths, and limitations. All of these are vital elements that you must include in the summary.

Most research papers merge conclusion with discussions. However, depending upon the instructions, you may have to prepare this as a separate section in your research summary. Usually, conclusion revisits the hypothesis and provides the details about the validation or denial about the arguments made in the research paper, based upon how convincing the results were obtained.

The structure of a research summary closely resembles the anatomy of a scholarly article . Additionally, you should keep your research and references limited to authentic and scholarly sources only.

Tips for Writing a Research Summary

The core concept behind undertaking a research summary is to present a simple and clear understanding of your research paper to the reader. The biggest hurdle while doing that is the number of words you have at your disposal. So, follow the steps below to write a research summary that sticks.

1. Read the parent paper thoroughly

You should go through the research paper thoroughly multiple times to ensure that you have a complete understanding of its contents. A 3-stage reading process helps.

a. Scan: In the first read, go through it to get an understanding of its basic concept and methodologies.

b. Read: For the second step, read the article attentively by going through each section, highlighting the key elements, and subsequently listing the topics that you will include in your research summary.

c. Skim: Flip through the article a few more times to study the interpretation of various experimental results, statistical analysis, and application in different contexts.

Sincerely go through different headings and subheadings as it will allow you to understand the underlying concept of each section. You can try reading the introduction and conclusion simultaneously to understand the motive of the task and how obtained results stay fit to the expected outcome.

2. Identify the key elements in different sections

While exploring different sections of an article, you can try finding answers to simple what, why, and how. Below are a few pointers to give you an idea:

- What is the research question and how is it addressed?

- Is there a hypothesis in the introductory part?

- What type of methods are being adopted?

- What is the sample size for data collection and how is it being analyzed?

- What are the most vital findings?

- Do the results support the hypothesis?

Discussion/Conclusion

- What is the final solution to the problem statement?

- What is the explanation for the obtained results?

- What is the drawn inference?

- What are the various limitations of the study?

3. Prepare the first draft

Now that you’ve listed the key points that the paper tries to demonstrate, you can start writing the summary following the standard structure of a research summary. Just make sure you’re not writing statements from the parent research paper verbatim.

Instead, try writing down each section in your own words. This will not only help in avoiding plagiarism but will also show your complete understanding of the subject. Alternatively, you can use a summarizing tool (AI-based summary generators) to shorten the content or summarize the content without disrupting the actual meaning of the article.

SciSpace Copilot is one such helpful feature! You can easily upload your research paper and ask Copilot to summarize it. You will get an AI-generated, condensed research summary. SciSpace Copilot also enables you to highlight text, clip math and tables, and ask any question relevant to the research paper; it will give you instant answers with deeper context of the article..

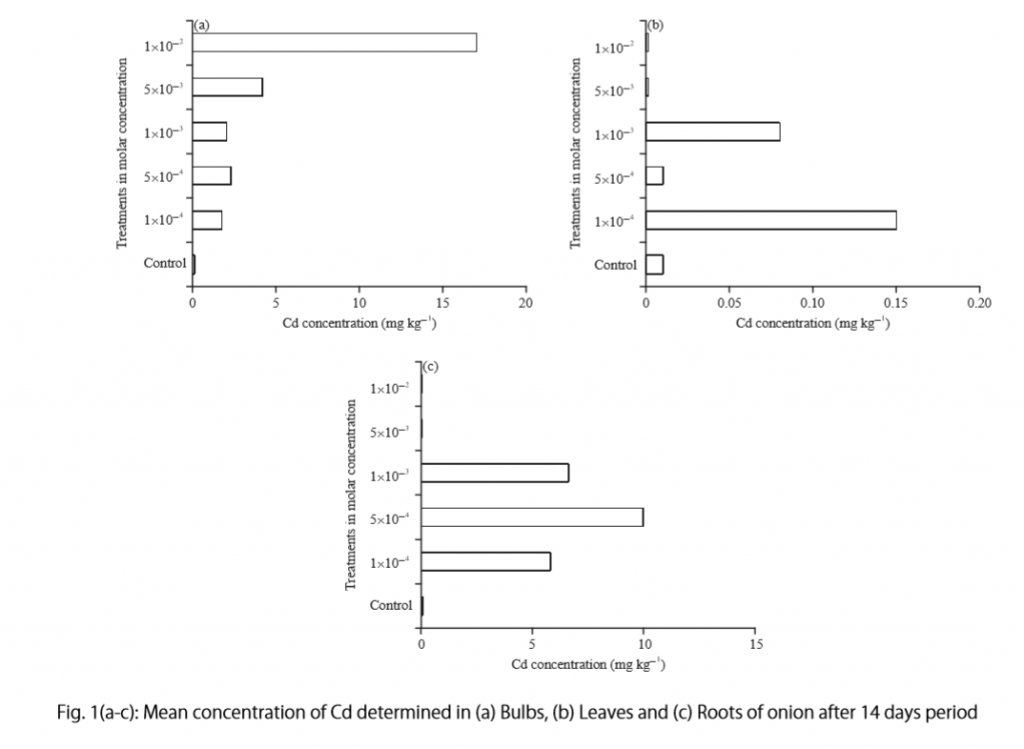

4. Include visuals

One of the best ways to summarize and consolidate a research paper is to provide visuals like graphs, charts, pie diagrams, etc.. Visuals make getting across the facts, the past trends, and the probabilistic figures around a concept much more engaging.

5. Double check for plagiarism

It can be very tempting to copy-paste a few statements or the entire paragraphs depending upon the clarity of those sections. But it’s best to stay away from the practice. Even paraphrasing should be done with utmost care and attention.

Also: QuillBot vs SciSpace: Choose the best AI-paraphrasing tool

6. Religiously follow the word count limit

You need to have strict control while writing different sections of a research summary. In many cases, it has been observed that the research summary and the parent research paper become the same length. If that happens, it can lead to discrediting of your efforts and research summary itself. Whatever the standard word limit has been imposed, you must observe that carefully.

7. Proofread your research summary multiple times

The process of writing the research summary can be exhausting and tiring. However, you shouldn’t allow this to become a reason to skip checking your academic writing several times for mistakes like misspellings, grammar, wordiness, and formatting issues. Proofread and edit until you think your research summary can stand out from the others, provided it is drafted perfectly on both technicality and comprehension parameters. You can also seek assistance from editing and proofreading services , and other free tools that help you keep these annoying grammatical errors at bay.

8. Watch while you write

Keep a keen observation of your writing style. You should use the words very precisely, and in any situation, it should not represent your personal opinions on the topic. You should write the entire research summary in utmost impersonal, precise, factually correct, and evidence-based writing.

9. Ask a friend/colleague to help

Once you are done with the final copy of your research summary, you must ask a friend or colleague to read it. You must test whether your friend or colleague could grasp everything without referring to the parent paper. This will help you in ensuring the clarity of the article.

Once you become familiar with the research paper summary concept and understand how to apply the tips discussed above in your current task, summarizing a research summary won’t be that challenging. While traversing the different stages of your academic career, you will face different scenarios where you may have to create several research summaries.

In such cases, you just need to look for answers to simple questions like “Why this study is necessary,” “what were the methods,” “who were the participants,” “what conclusions were drawn from the research,” and “how it is relevant to the wider world.” Once you find out the answers to these questions, you can easily create a good research summary following the standard structure and a precise writing style.

You might also like

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Types of Essays in Academic Writing - Quick Guide (2024)

How To Write The Results/Findings Chapter

For qualitative studies (dissertations & theses).

By: Jenna Crossley (PhD Cand). Expert Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | August 2021

So, you’ve collected and analysed your qualitative data, and it’s time to write up your results chapter – exciting! But where do you start? In this post, we’ll guide you through the qualitative results chapter (also called the findings chapter), step by step.

Overview: Qualitative Results Chapter

- What (exactly) the qualitative results chapter is

- What to include in your results chapter

- How to write up your results chapter

- A few tips and tricks to help you along the way

What exactly is the results chapter?

The results chapter in a dissertation or thesis (or any formal academic research piece) is where you objectively and neutrally present the findings of your qualitative analysis (or analyses if you used multiple qualitative analysis methods ). This chapter can sometimes be combined with the discussion chapter (where you interpret the data and discuss its meaning), depending on your university’s preference. We’ll treat the two chapters as separate, as that’s the most common approach.

In contrast to a quantitative results chapter that presents numbers and statistics, a qualitative results chapter presents data primarily in the form of words . But this doesn’t mean that a qualitative study can’t have quantitative elements – you could, for example, present the number of times a theme or topic pops up in your data, depending on the analysis method(s) you adopt.

Adding a quantitative element to your study can add some rigour, which strengthens your results by providing more evidence for your claims. This is particularly common when using qualitative content analysis. Keep in mind though that qualitative research aims to achieve depth, richness and identify nuances , so don’t get tunnel vision by focusing on the numbers. They’re just cream on top in a qualitative analysis.

So, to recap, the results chapter is where you objectively present the findings of your analysis, without interpreting them (you’ll save that for the discussion chapter). With that out the way, let’s take a look at what you should include in your results chapter.

What should you include in the results chapter?

As we’ve mentioned, your qualitative results chapter should purely present and describe your results , not interpret them in relation to the existing literature or your research questions . Any speculations or discussion about the implications of your findings should be reserved for your discussion chapter.

In your results chapter, you’ll want to talk about your analysis findings and whether or not they support your hypotheses (if you have any). Naturally, the exact contents of your results chapter will depend on which qualitative analysis method (or methods) you use. For example, if you were to use thematic analysis, you’d detail the themes identified in your analysis, using extracts from the transcripts or text to support your claims.

While you do need to present your analysis findings in some detail, you should avoid dumping large amounts of raw data in this chapter. Instead, focus on presenting the key findings and using a handful of select quotes or text extracts to support each finding . The reams of data and analysis can be relegated to your appendices.

While it’s tempting to include every last detail you found in your qualitative analysis, it is important to make sure that you report only that which is relevant to your research aims, objectives and research questions . Always keep these three components, as well as your hypotheses (if you have any) front of mind when writing the chapter and use them as a filter to decide what’s relevant and what’s not.

Need a helping hand?

How do I write the results chapter?

Now that we’ve covered the basics, it’s time to look at how to structure your chapter. Broadly speaking, the results chapter needs to contain three core components – the introduction, the body and the concluding summary. Let’s take a look at each of these.

Section 1: Introduction

The first step is to craft a brief introduction to the chapter. This intro is vital as it provides some context for your findings. In your introduction, you should begin by reiterating your problem statement and research questions and highlight the purpose of your research . Make sure that you spell this out for the reader so that the rest of your chapter is well contextualised.

The next step is to briefly outline the structure of your results chapter. In other words, explain what’s included in the chapter and what the reader can expect. In the results chapter, you want to tell a story that is coherent, flows logically, and is easy to follow , so make sure that you plan your structure out well and convey that structure (at a high level), so that your reader is well oriented.

The introduction section shouldn’t be lengthy. Two or three short paragraphs should be more than adequate. It is merely an introduction and overview, not a summary of the chapter.

Pro Tip – To help you structure your chapter, it can be useful to set up an initial draft with (sub)section headings so that you’re able to easily (re)arrange parts of your chapter. This will also help your reader to follow your results and give your chapter some coherence. Be sure to use level-based heading styles (e.g. Heading 1, 2, 3 styles) to help the reader differentiate between levels visually. You can find these options in Word (example below).

Section 2: Body

Before we get started on what to include in the body of your chapter, it’s vital to remember that a results section should be completely objective and descriptive, not interpretive . So, be careful not to use words such as, “suggests” or “implies”, as these usually accompany some form of interpretation – that’s reserved for your discussion chapter.

The structure of your body section is very important , so make sure that you plan it out well. When planning out your qualitative results chapter, create sections and subsections so that you can maintain the flow of the story you’re trying to tell. Be sure to systematically and consistently describe each portion of results. Try to adopt a standardised structure for each portion so that you achieve a high level of consistency throughout the chapter.

For qualitative studies, results chapters tend to be structured according to themes , which makes it easier for readers to follow. However, keep in mind that not all results chapters have to be structured in this manner. For example, if you’re conducting a longitudinal study, you may want to structure your chapter chronologically. Similarly, you might structure this chapter based on your theoretical framework . The exact structure of your chapter will depend on the nature of your study , especially your research questions.

As you work through the body of your chapter, make sure that you use quotes to substantiate every one of your claims . You can present these quotes in italics to differentiate them from your own words. A general rule of thumb is to use at least two pieces of evidence per claim, and these should be linked directly to your data. Also, remember that you need to include all relevant results , not just the ones that support your assumptions or initial leanings.

In addition to including quotes, you can also link your claims to the data by using appendices , which you should reference throughout your text. When you reference, make sure that you include both the name/number of the appendix , as well as the line(s) from which you drew your data.

As referencing styles can vary greatly, be sure to look up the appendix referencing conventions of your university’s prescribed style (e.g. APA , Harvard, etc) and keep this consistent throughout your chapter.

Section 3: Concluding summary

The concluding summary is very important because it summarises your key findings and lays the foundation for the discussion chapter . Keep in mind that some readers may skip directly to this section (from the introduction section), so make sure that it can be read and understood well in isolation.

In this section, you need to remind the reader of the key findings. That is, the results that directly relate to your research questions and that you will build upon in your discussion chapter. Remember, your reader has digested a lot of information in this chapter, so you need to use this section to remind them of the most important takeaways.

Importantly, the concluding summary should not present any new information and should only describe what you’ve already presented in your chapter. Keep it concise – you’re not summarising the whole chapter, just the essentials.

Tips and tricks for an A-grade results chapter

Now that you’ve got a clear picture of what the qualitative results chapter is all about, here are some quick tips and reminders to help you craft a high-quality chapter:

- Your results chapter should be written in the past tense . You’ve done the work already, so you want to tell the reader what you found , not what you are currently finding .

- Make sure that you review your work multiple times and check that every claim is adequately backed up by evidence . Aim for at least two examples per claim, and make use of an appendix to reference these.

- When writing up your results, make sure that you stick to only what is relevant . Don’t waste time on data that are not relevant to your research objectives and research questions.

- Use headings and subheadings to create an intuitive, easy to follow piece of writing. Make use of Microsoft Word’s “heading styles” and be sure to use them consistently.

- When referring to numerical data, tables and figures can provide a useful visual aid. When using these, make sure that they can be read and understood independent of your body text (i.e. that they can stand-alone). To this end, use clear, concise labels for each of your tables or figures and make use of colours to code indicate differences or hierarchy.

- Similarly, when you’re writing up your chapter, it can be useful to highlight topics and themes in different colours . This can help you to differentiate between your data if you get a bit overwhelmed and will also help you to ensure that your results flow logically and coherently.

If you have any questions, leave a comment below and we’ll do our best to help. If you’d like 1-on-1 help with your results chapter (or any chapter of your dissertation or thesis), check out our private dissertation coaching service here or book a free initial consultation to discuss how we can help you.

Psst… there’s more (for free)

This post is part of our dissertation mini-course, which covers everything you need to get started with your dissertation, thesis or research project.

You Might Also Like:

20 Comments

This was extremely helpful. Thanks a lot guys

Hi, thanks for the great research support platform created by the gradcoach team!

I wanted to ask- While “suggests” or “implies” are interpretive terms, what terms could we use for the results chapter? Could you share some examples of descriptive terms?

I think that instead of saying, ‘The data suggested, or The data implied,’ you can say, ‘The Data showed or revealed, or illustrated or outlined’…If interview data, you may say Jane Doe illuminated or elaborated, or Jane Doe described… or Jane Doe expressed or stated.

I found this article very useful. Thank you very much for the outstanding work you are doing.

What if i have 3 different interviewees answering the same interview questions? Should i then present the results in form of the table with the division on the 3 perspectives or rather give a results in form of the text and highlight who said what?

I think this tabular representation of results is a great idea. I am doing it too along with the text. Thanks

That was helpful was struggling to separate the discussion from the findings

this was very useful, Thank you.

Very helpful, I am confident to write my results chapter now.

It is so helpful! It is a good job. Thank you very much!

Very useful, well explained. Many thanks.

Hello, I appreciate the way you provided a supportive comments about qualitative results presenting tips

I loved this! It explains everything needed, and it has helped me better organize my thoughts. What words should I not use while writing my results section, other than subjective ones.

Thanks a lot, it is really helpful

Thank you so much dear, i really appropriate your nice explanations about this.

Thank you so much for this! I was wondering if anyone could help with how to prproperly integrate quotations (Excerpts) from interviews in the finding chapter in a qualitative research. Please GradCoach, address this issue and provide examples.

what if I’m not doing any interviews myself and all the information is coming from case studies that have already done the research.

Very helpful thank you.

This was very helpful as I was wondering how to structure this part of my dissertation, to include the quotes… Thanks for this explanation

This is very helpful, thanks! I am required to write up my results chapters with the discussion in each of them – any tips and tricks for this strategy?

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Jump to navigation

Cochrane Training

Chapter 14: completing ‘summary of findings’ tables and grading the certainty of the evidence.

Holger J Schünemann, Julian PT Higgins, Gunn E Vist, Paul Glasziou, Elie A Akl, Nicole Skoetz, Gordon H Guyatt; on behalf of the Cochrane GRADEing Methods Group (formerly Applicability and Recommendations Methods Group) and the Cochrane Statistical Methods Group

Key Points:

- A ‘Summary of findings’ table for a given comparison of interventions provides key information concerning the magnitudes of relative and absolute effects of the interventions examined, the amount of available evidence and the certainty (or quality) of available evidence.

- ‘Summary of findings’ tables include a row for each important outcome (up to a maximum of seven). Accepted formats of ‘Summary of findings’ tables and interactive ‘Summary of findings’ tables can be produced using GRADE’s software GRADEpro GDT.

- Cochrane has adopted the GRADE approach (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) for assessing certainty (or quality) of a body of evidence.

- The GRADE approach specifies four levels of the certainty for a body of evidence for a given outcome: high, moderate, low and very low.

- GRADE assessments of certainty are determined through consideration of five domains: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision and publication bias. For evidence from non-randomized studies and rarely randomized studies, assessments can then be upgraded through consideration of three further domains.

Cite this chapter as: Schünemann HJ, Higgins JPT, Vist GE, Glasziou P, Akl EA, Skoetz N, Guyatt GH. Chapter 14: Completing ‘Summary of findings’ tables and grading the certainty of the evidence. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.4 (updated August 2023). Cochrane, 2023. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook .

14.1 ‘Summary of findings’ tables

14.1.1 introduction to ‘summary of findings’ tables.

‘Summary of findings’ tables present the main findings of a review in a transparent, structured and simple tabular format. In particular, they provide key information concerning the certainty or quality of evidence (i.e. the confidence or certainty in the range of an effect estimate or an association), the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data on the main outcomes. Cochrane Reviews should incorporate ‘Summary of findings’ tables during planning and publication, and should have at least one key ‘Summary of findings’ table representing the most important comparisons. Some reviews may include more than one ‘Summary of findings’ table, for example if the review addresses more than one major comparison, or includes substantially different populations that require separate tables (e.g. because the effects differ or it is important to show results separately). In the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), all ‘Summary of findings’ tables for a review appear at the beginning, before the Background section.

14.1.2 Selecting outcomes for ‘Summary of findings’ tables

Planning for the ‘Summary of findings’ table starts early in the systematic review, with the selection of the outcomes to be included in: (i) the review; and (ii) the ‘Summary of findings’ table. This is a crucial step, and one that review authors need to address carefully.

To ensure production of optimally useful information, Cochrane Reviews begin by developing a review question and by listing all main outcomes that are important to patients and other decision makers (see Chapter 2 and Chapter 3 ). The GRADE approach to assessing the certainty of the evidence (see Section 14.2 ) defines and operationalizes a rating process that helps separate outcomes into those that are critical, important or not important for decision making. Consultation and feedback on the review protocol, including from consumers and other decision makers, can enhance this process.

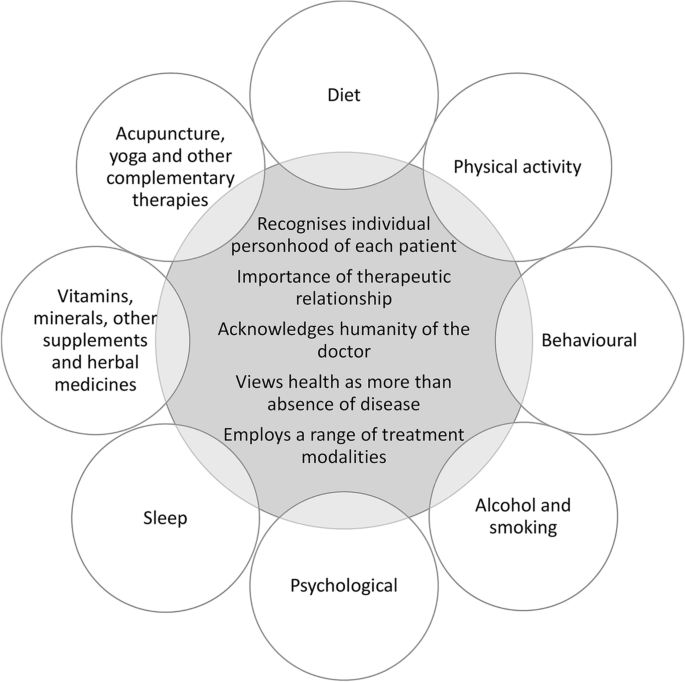

Critical outcomes are likely to include clearly important endpoints; typical examples include mortality and major morbidity (such as strokes and myocardial infarction). However, they may also represent frequent minor and rare major side effects, symptoms, quality of life, burdens associated with treatment, and resource issues (costs). Burdens represent the impact of healthcare workload on patient function and well-being, and include the demands of adhering to an intervention that patients or caregivers (e.g. family) may dislike, such as having to undergo more frequent tests, or the restrictions on lifestyle that certain interventions require (Spencer-Bonilla et al 2017).

Frequently, when formulating questions that include all patient-important outcomes for decision making, review authors will confront reports of studies that have not included all these outcomes. This is particularly true for adverse outcomes. For instance, randomized trials might contribute evidence on intended effects, and on frequent, relatively minor side effects, but not report on rare adverse outcomes such as suicide attempts. Chapter 19 discusses strategies for addressing adverse effects. To obtain data for all important outcomes it may be necessary to examine the results of non-randomized studies (see Chapter 24 ). Cochrane, in collaboration with others, has developed guidance for review authors to support their decision about when to look for and include non-randomized studies (Schünemann et al 2013).

If a review includes only randomized trials, these trials may not address all important outcomes and it may therefore not be possible to address these outcomes within the constraints of the review. Review authors should acknowledge these limitations and make them transparent to readers. Review authors are encouraged to include non-randomized studies to examine rare or long-term adverse effects that may not adequately be studied in randomized trials. This raises the possibility that harm outcomes may come from studies in which participants differ from those in studies used in the analysis of benefit. Review authors will then need to consider how much such differences are likely to impact on the findings, and this will influence the certainty of evidence because of concerns about indirectness related to the population (see Section 14.2.2 ).

Non-randomized studies can provide important information not only when randomized trials do not report on an outcome or randomized trials suffer from indirectness, but also when the evidence from randomized trials is rated as very low and non-randomized studies provide evidence of higher certainty. Further discussion of these issues appears also in Chapter 24 .

14.1.3 General template for ‘Summary of findings’ tables

Several alternative standard versions of ‘Summary of findings’ tables have been developed to ensure consistency and ease of use across reviews, inclusion of the most important information needed by decision makers, and optimal presentation (see examples at Figures 14.1.a and 14.1.b ). These formats are supported by research that focused on improved understanding of the information they intend to convey (Carrasco-Labra et al 2016, Langendam et al 2016, Santesso et al 2016). They are available through GRADE’s official software package developed to support the GRADE approach: GRADEpro GDT (www.gradepro.org).

Standard Cochrane ‘Summary of findings’ tables include the following elements using one of the accepted formats. Further guidance on each of these is provided in Section 14.1.6 .

- A brief description of the population and setting addressed by the available evidence (which may be slightly different to or narrower than those defined by the review question).

- A brief description of the comparison addressed in the ‘Summary of findings’ table, including both the experimental and comparison interventions.

- A list of the most critical and/or important health outcomes, both desirable and undesirable, limited to seven or fewer outcomes.

- A measure of the typical burden of each outcomes (e.g. illustrative risk, or illustrative mean, on comparator intervention).

- The absolute and relative magnitude of effect measured for each (if both are appropriate).

- The numbers of participants and studies contributing to the analysis of each outcomes.

- A GRADE assessment of the overall certainty of the body of evidence for each outcome (which may vary by outcome).

- Space for comments.

- Explanations (formerly known as footnotes).

Ideally, ‘Summary of findings’ tables are supported by more detailed tables (known as ‘evidence profiles’) to which the review may be linked, which provide more detailed explanations. Evidence profiles include the same important health outcomes, and provide greater detail than ‘Summary of findings’ tables of both of the individual considerations feeding into the grading of certainty and of the results of the studies (Guyatt et al 2011a). They ensure that a structured approach is used to rating the certainty of evidence. Although they are rarely published in Cochrane Reviews, evidence profiles are often used, for example, by guideline developers in considering the certainty of the evidence to support guideline recommendations. Review authors will find it easier to develop the ‘Summary of findings’ table by completing the rating of the certainty of evidence in the evidence profile first in GRADEpro GDT. They can then automatically convert this to one of the ‘Summary of findings’ formats in GRADEpro GDT, including an interactive ‘Summary of findings’ for publication.

As a measure of the magnitude of effect for dichotomous outcomes, the ‘Summary of findings’ table should provide a relative measure of effect (e.g. risk ratio, odds ratio, hazard) and measures of absolute risk. For other types of data, an absolute measure alone (such as a difference in means for continuous data) might be sufficient. It is important that the magnitude of effect is presented in a meaningful way, which may require some transformation of the result of a meta-analysis (see also Chapter 15, Section 15.4 and Section 15.5 ). Reviews with more than one main comparison should include a separate ‘Summary of findings’ table for each comparison.

Figure 14.1.a provides an example of a ‘Summary of findings’ table. Figure 15.1.b provides an alternative format that may further facilitate users’ understanding and interpretation of the review’s findings. Evidence evaluating different formats suggests that the ‘Summary of findings’ table should include a risk difference as a measure of the absolute effect and authors should preferably use a format that includes a risk difference .

A detailed description of the contents of a ‘Summary of findings’ table appears in Section 14.1.6 .

Figure 14.1.a Example of a ‘Summary of findings’ table

Summary of findings (for interactive version click here )

a All the stockings in the nine studies included in this review were below-knee compression stockings. In four studies the compression strength was 20 mmHg to 30 mmHg at the ankle. It was 10 mmHg to 20 mmHg in the other four studies. Stockings come in different sizes. If a stocking is too tight around the knee it can prevent essential venous return causing the blood to pool around the knee. Compression stockings should be fitted properly. A stocking that is too tight could cut into the skin on a long flight and potentially cause ulceration and increased risk of DVT. Some stockings can be slightly thicker than normal leg covering and can be potentially restrictive with tight foot wear. It is a good idea to wear stockings around the house prior to travel to ensure a good, comfortable fit. Participants put their stockings on two to three hours before the flight in most of the studies. The availability and cost of stockings can vary.

b Two studies recruited high risk participants defined as those with previous episodes of DVT, coagulation disorders, severe obesity, limited mobility due to bone or joint problems, neoplastic disease within the previous two years, large varicose veins or, in one of the studies, participants taller than 190 cm and heavier than 90 kg. The incidence for the seven studies that excluded high risk participants was 1.45% and the incidence for the two studies that recruited high-risk participants (with at least one risk factor) was 2.43%. We have used 10 and 30 per 1000 to express different risk strata, respectively.

c The confidence interval crosses no difference and does not rule out a small increase.

d The measurement of oedema was not validated (indirectness of the outcome) or blinded to the intervention (risk of bias).

e If there are very few or no events and the number of participants is large, judgement about the certainty of evidence (particularly judgements about imprecision) may be based on the absolute effect. Here the certainty rating may be considered ‘high’ if the outcome was appropriately assessed and the event, in fact, did not occur in 2821 studied participants.

f None of the other studies reported adverse effects, apart from four cases of superficial vein thrombosis in varicose veins in the knee region that were compressed by the upper edge of the stocking in one study.

Figure 14.1.b Example of alternative ‘Summary of findings’ table

14.1.4 Producing ‘Summary of findings’ tables

The GRADE Working Group’s software, GRADEpro GDT ( www.gradepro.org ), including GRADE’s interactive handbook, is available to assist review authors in the preparation of ‘Summary of findings’ tables. GRADEpro can use data on the comparator group risk and the effect estimate (entered by the review authors or imported from files generated in RevMan) to produce the relative effects and absolute risks associated with experimental interventions. In addition, it leads the user through the process of a GRADE assessment, and produces a table that can be used as a standalone table in a review (including by direct import into software such as RevMan or integration with RevMan Web), or an interactive ‘Summary of findings’ table (see help resources in GRADEpro).

14.1.5 Statistical considerations in ‘Summary of findings’ tables

14.1.5.1 dichotomous outcomes.

‘Summary of findings’ tables should include both absolute and relative measures of effect for dichotomous outcomes. Risk ratios, odds ratios and risk differences are different ways of comparing two groups with dichotomous outcome data (see Chapter 6, Section 6.4.1 ). Furthermore, there are two distinct risk ratios, depending on which event (e.g. ‘yes’ or ‘no’) is the focus of the analysis (see Chapter 6, Section 6.4.1.5 ). In the presence of a non-zero intervention effect, any variation across studies in the comparator group risks (i.e. variation in the risk of the event occurring without the intervention of interest, for example in different populations) makes it impossible for more than one of these measures to be truly the same in every study.

It has long been assumed in epidemiology that relative measures of effect are more consistent than absolute measures of effect from one scenario to another. There is empirical evidence to support this assumption (Engels et al 2000, Deeks and Altman 2001, Furukawa et al 2002). For this reason, meta-analyses should generally use either a risk ratio or an odds ratio as a measure of effect (see Chapter 10, Section 10.4.3 ). Correspondingly, a single estimate of relative effect is likely to be a more appropriate summary than a single estimate of absolute effect. If a relative effect is indeed consistent across studies, then different comparator group risks will have different implications for absolute benefit. For instance, if the risk ratio is consistently 0.75, then the experimental intervention would reduce a comparator group risk of 80% to 60% in the intervention group (an absolute risk reduction of 20 percentage points), but would also reduce a comparator group risk of 20% to 15% in the intervention group (an absolute risk reduction of 5 percentage points).

‘Summary of findings’ tables are built around the assumption of a consistent relative effect. It is therefore important to consider the implications of this effect for different comparator group risks (these can be derived or estimated from a number of sources, see Section 14.1.6.3 ), which may require an assessment of the certainty of evidence for prognostic evidence (Spencer et al 2012, Iorio et al 2015). For any comparator group risk, it is possible to estimate a corresponding intervention group risk (i.e. the absolute risk with the intervention) from the meta-analytic risk ratio or odds ratio. Note that the numbers provided in the ‘Corresponding risk’ column are specific to the ‘risks’ in the adjacent column.

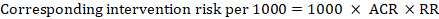

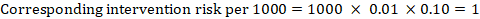

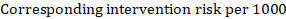

For the meta-analytic risk ratio (RR) and assumed comparator risk (ACR) the corresponding intervention risk is obtained as:

As an example, in Figure 14.1.a , the meta-analytic risk ratio for symptomless deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is RR = 0.10 (95% CI 0.04 to 0.26). Assuming a comparator risk of ACR = 10 per 1000 = 0.01, we obtain:

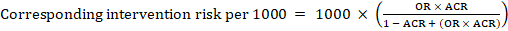

For the meta-analytic odds ratio (OR) and assumed comparator risk, ACR, the corresponding intervention risk is obtained as:

Upper and lower confidence limits for the corresponding intervention risk are obtained by replacing RR or OR by their upper and lower confidence limits, respectively (e.g. replacing 0.10 with 0.04, then with 0.26, in the example). Such confidence intervals do not incorporate uncertainty in the assumed comparator risks.

When dealing with risk ratios, it is critical that the same definition of ‘event’ is used as was used for the meta-analysis. For example, if the meta-analysis focused on ‘death’ (as opposed to survival) as the event, then corresponding risks in the ‘Summary of findings’ table must also refer to ‘death’.

In (rare) circumstances in which there is clear rationale to assume a consistent risk difference in the meta-analysis, in principle it is possible to present this for relevant ‘assumed risks’ and their corresponding risks, and to present the corresponding (different) relative effects for each assumed risk.

The risk difference expresses the difference between the ACR and the corresponding intervention risk (or the difference between the experimental and the comparator intervention).

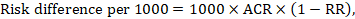

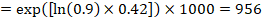

For the meta-analytic risk ratio (RR) and assumed comparator risk (ACR) the corresponding risk difference is obtained as (note that risks can also be expressed using percentage or percentage points):

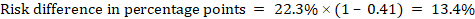

As an example, in Figure 14.1.b the meta-analytic risk ratio is 0.41 (95% CI 0.29 to 0.55) for diarrhoea in children less than 5 years of age. Assuming a comparator group risk of 22.3% we obtain:

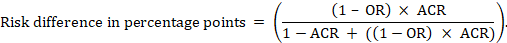

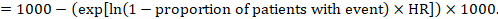

For the meta-analytic odds ratio (OR) and assumed comparator risk (ACR) the absolute risk difference is obtained as (percentage points):

Upper and lower confidence limits for the absolute risk difference are obtained by re-running the calculation above while replacing RR or OR by their upper and lower confidence limits, respectively (e.g. replacing 0.41 with 0.28, then with 0.55, in the example). Such confidence intervals do not incorporate uncertainty in the assumed comparator risks.

14.1.5.2 Time-to-event outcomes

Time-to-event outcomes measure whether and when a particular event (e.g. death) occurs (van Dalen et al 2007). The impact of the experimental intervention relative to the comparison group on time-to-event outcomes is usually measured using a hazard ratio (HR) (see Chapter 6, Section 6.8.1 ).

A hazard ratio expresses a relative effect estimate. It may be used in various ways to obtain absolute risks and other interpretable quantities for a specific population. Here we describe how to re-express hazard ratios in terms of: (i) absolute risk of event-free survival within a particular period of time; (ii) absolute risk of an event within a particular period of time; and (iii) median time to the event. All methods are built on an assumption of consistent relative effects (i.e. that the hazard ratio does not vary over time).

(i) Absolute risk of event-free survival within a particular period of time Event-free survival (e.g. overall survival) is commonly reported by individual studies. To obtain absolute effects for time-to-event outcomes measured as event-free survival, the summary HR can be used in conjunction with an assumed proportion of patients who are event-free in the comparator group (Tierney et al 2007). This proportion of patients will be specific to a period of time of observation. However, it is not strictly necessary to specify this period of time. For instance, a proportion of 50% of event-free patients might apply to patients with a high event rate observed over 1 year, or to patients with a low event rate observed over 2 years.

As an example, suppose the meta-analytic hazard ratio is 0.42 (95% CI 0.25 to 0.72). Assuming a comparator group risk of event-free survival (e.g. for overall survival people being alive) at 2 years of ACR = 900 per 1000 = 0.9 we obtain:

so that that 956 per 1000 people will be alive with the experimental intervention at 2 years. The derivation of the risk should be explained in a comment or footnote.

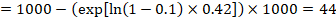

(ii) Absolute risk of an event within a particular period of time To obtain this absolute effect, again the summary HR can be used (Tierney et al 2007):

In the example, suppose we assume a comparator group risk of events (e.g. for mortality, people being dead) at 2 years of ACR = 100 per 1000 = 0.1. We obtain:

so that that 44 per 1000 people will be dead with the experimental intervention at 2 years.

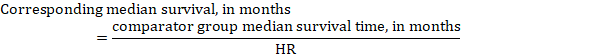

(iii) Median time to the event Instead of absolute numbers, the time to the event in the intervention and comparison groups can be expressed as median survival time in months or years. To obtain median survival time the pooled HR can be applied to an assumed median survival time in the comparator group (Tierney et al 2007):

In the example, assuming a comparator group median survival time of 80 months, we obtain:

For all three of these options for re-expressing results of time-to-event analyses, upper and lower confidence limits for the corresponding intervention risk are obtained by replacing HR by its upper and lower confidence limits, respectively (e.g. replacing 0.42 with 0.25, then with 0.72, in the example). Again, as for dichotomous outcomes, such confidence intervals do not incorporate uncertainty in the assumed comparator group risks. This is of special concern for long-term survival with a low or moderate mortality rate and a corresponding high number of censored patients (i.e. a low number of patients under risk and a high censoring rate).

14.1.6 Detailed contents of a ‘Summary of findings’ table

14.1.6.1 table title and header.

The title of each ‘Summary of findings’ table should specify the healthcare question, framed in terms of the population and making it clear exactly what comparison of interventions are made. In Figure 14.1.a , the population is people taking long aeroplane flights, the intervention is compression stockings, and the control is no compression stockings.

The first rows of each ‘Summary of findings’ table should provide the following ‘header’ information:

Patients or population This further clarifies the population (and possibly the subpopulations) of interest and ideally the magnitude of risk of the most crucial adverse outcome at which an intervention is directed. For instance, people on a long-haul flight may be at different risks for DVT; those using selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) might be at different risk for side effects; while those with atrial fibrillation may be at low (< 1%), moderate (1% to 4%) or high (> 4%) yearly risk of stroke.

Setting This should state any specific characteristics of the settings of the healthcare question that might limit the applicability of the summary of findings to other settings (e.g. primary care in Europe and North America).

Intervention The experimental intervention.

Comparison The comparator intervention (including no specific intervention).

14.1.6.2 Outcomes

The rows of a ‘Summary of findings’ table should include all desirable and undesirable health outcomes (listed in order of importance) that are essential for decision making, up to a maximum of seven outcomes. If there are more outcomes in the review, review authors will need to omit the less important outcomes from the table, and the decision selecting which outcomes are critical or important to the review should be made during protocol development (see Chapter 3 ). Review authors should provide time frames for the measurement of the outcomes (e.g. 90 days or 12 months) and the type of instrument scores (e.g. ranging from 0 to 100).

Note that review authors should include the pre-specified critical and important outcomes in the table whether data are available or not. However, they should be alert to the possibility that the importance of an outcome (e.g. a serious adverse effect) may only become known after the protocol was written or the analysis was carried out, and should take appropriate actions to include these in the ‘Summary of findings’ table.

The ‘Summary of findings’ table can include effects in subgroups of the population for different comparator risks and effect sizes separately. For instance, in Figure 14.1.b effects are presented for children younger and older than 5 years separately. Review authors may also opt to produce separate ‘Summary of findings’ tables for different populations.

Review authors should include serious adverse events, but it might be possible to combine minor adverse events as a single outcome, and describe this in an explanatory footnote (note that it is not appropriate to add events together unless they are independent, that is, a participant who has experienced one adverse event has an unaffected chance of experiencing the other adverse event).

Outcomes measured at multiple time points represent a particular problem. In general, to keep the table simple, review authors should present multiple time points only for outcomes critical to decision making, where either the result or the decision made are likely to vary over time. The remainder should be presented at a common time point where possible.

Review authors can present continuous outcome measures in the ‘Summary of findings’ table and should endeavour to make these interpretable to the target audience. This requires that the units are clear and readily interpretable, for example, days of pain, or frequency of headache, and the name and scale of any measurement tools used should be stated (e.g. a Visual Analogue Scale, ranging from 0 to 100). However, many measurement instruments are not readily interpretable by non-specialist clinicians or patients, for example, points on a Beck Depression Inventory or quality of life score. For these, a more interpretable presentation might involve converting a continuous to a dichotomous outcome, such as >50% improvement (see Chapter 15, Section 15.5 ).

14.1.6.3 Best estimate of risk with comparator intervention

Review authors should provide up to three typical risks for participants receiving the comparator intervention. For dichotomous outcomes, we recommend that these be presented in the form of the number of people experiencing the event per 100 or 1000 people (natural frequency) depending on the frequency of the outcome. For continuous outcomes, this would be stated as a mean or median value of the outcome measured.

Estimated or assumed comparator intervention risks could be based on assessments of typical risks in different patient groups derived from the review itself, individual representative studies in the review, or risks derived from a systematic review of prognosis studies or other sources of evidence which may in turn require an assessment of the certainty for the prognostic evidence (Spencer et al 2012, Iorio et al 2015). Ideally, risks would reflect groups that clinicians can easily identify on the basis of their presenting features.

An explanatory footnote should specify the source or rationale for each comparator group risk, including the time period to which it corresponds where appropriate. In Figure 14.1.a , clinicians can easily differentiate individuals with risk factors for deep venous thrombosis from those without. If there is known to be little variation in baseline risk then review authors may use the median comparator group risk across studies. If typical risks are not known, an option is to choose the risk from the included studies, providing the second highest for a high and the second lowest for a low risk population.

14.1.6.4 Risk with intervention

For dichotomous outcomes, review authors should provide a corresponding absolute risk for each comparator group risk, along with a confidence interval. This absolute risk with the (experimental) intervention will usually be derived from the meta-analysis result presented in the relative effect column (see Section 14.1.6.6 ). Formulae are provided in Section 14.1.5 . Review authors should present the absolute effect in the same format as the risks with comparator intervention (see Section 14.1.6.3 ), for example as the number of people experiencing the event per 1000 people.

For continuous outcomes, a difference in means or standardized difference in means should be presented with its confidence interval. These will typically be obtained directly from a meta-analysis. Explanatory text should be used to clarify the meaning, as in Figures 14.1.a and 14.1.b .

14.1.6.5 Risk difference

For dichotomous outcomes, the risk difference can be provided using one of the ‘Summary of findings’ table formats as an additional option (see Figure 14.1.b ). This risk difference expresses the difference between the experimental and comparator intervention and will usually be derived from the meta-analysis result presented in the relative effect column (see Section 14.1.6.6 ). Formulae are provided in Section 14.1.5 . Review authors should present the risk difference in the same format as assumed and corresponding risks with comparator intervention (see Section 14.1.6.3 ); for example, as the number of people experiencing the event per 1000 people or as percentage points if the assumed and corresponding risks are expressed in percentage.

For continuous outcomes, if the ‘Summary of findings’ table includes this option, the mean difference can be presented here and the ‘corresponding risk’ column left blank (see Figure 14.1.b ).

14.1.6.6 Relative effect (95% CI)

The relative effect will typically be a risk ratio or odds ratio (or occasionally a hazard ratio) with its accompanying 95% confidence interval, obtained from a meta-analysis performed on the basis of the same effect measure. Risk ratios and odds ratios are similar when the comparator intervention risks are low and effects are small, but may differ considerably when comparator group risks increase. The meta-analysis may involve an assumption of either fixed or random effects, depending on what the review authors consider appropriate, and implying that the relative effect is either an estimate of the effect of the intervention, or an estimate of the average effect of the intervention across studies, respectively.

14.1.6.7 Number of participants (studies)

This column should include the number of participants assessed in the included studies for each outcome and the corresponding number of studies that contributed these participants.

14.1.6.8 Certainty of the evidence (GRADE)

Review authors should comment on the certainty of the evidence (also known as quality of the body of evidence or confidence in the effect estimates). Review authors should use the specific evidence grading system developed by the GRADE Working Group (Atkins et al 2004, Guyatt et al 2008, Guyatt et al 2011a), which is described in detail in Section 14.2 . The GRADE approach categorizes the certainty in a body of evidence as ‘high’, ‘moderate’, ‘low’ or ‘very low’ by outcome. This is a result of judgement, but the judgement process operates within a transparent structure. As an example, the certainty would be ‘high’ if the summary were of several randomized trials with low risk of bias, but the rating of certainty becomes lower if there are concerns about risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision or publication bias. Judgements other than of ‘high’ certainty should be made transparent using explanatory footnotes or the ‘Comments’ column in the ‘Summary of findings’ table (see Section 14.1.6.10 ).

14.1.6.9 Comments

The aim of the ‘Comments’ field is to help interpret the information or data identified in the row. For example, this may be on the validity of the outcome measure or the presence of variables that are associated with the magnitude of effect. Important caveats about the results should be flagged here. Not all rows will need comments, and it is best to leave a blank if there is nothing warranting a comment.

14.1.6.10 Explanations

Detailed explanations should be included as footnotes to support the judgements in the ‘Summary of findings’ table, such as the overall GRADE assessment. The explanations should describe the rationale for important aspects of the content. Table 14.1.a lists guidance for useful explanations. Explanations should be concise, informative, relevant, easy to understand and accurate. If explanations cannot be sufficiently described in footnotes, review authors should provide further details of the issues in the Results and Discussion sections of the review.

Table 14.1.a Guidance for providing useful explanations in ‘Summary of findings’ (SoF) tables. Adapted from Santesso et al (2016)

14.2 Assessing the certainty or quality of a body of evidence

14.2.1 the grade approach.

The Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation Working Group (GRADE Working Group) has developed a system for grading the certainty of evidence (Schünemann et al 2003, Atkins et al 2004, Schünemann et al 2006, Guyatt et al 2008, Guyatt et al 2011a). Over 100 organizations including the World Health Organization (WHO), the American College of Physicians, the American Society of Hematology (ASH), the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technology in Health (CADTH) and the National Institutes of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) in the UK have adopted the GRADE system ( www.gradeworkinggroup.org ).

Cochrane has also formally adopted this approach, and all Cochrane Reviews should use GRADE to evaluate the certainty of evidence for important outcomes (see MECIR Box 14.2.a ).

MECIR Box 14.2.a Relevant expectations for conduct of intervention reviews

For systematic reviews, the GRADE approach defines the certainty of a body of evidence as the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association is close to the quantity of specific interest. Assessing the certainty of a body of evidence involves consideration of within- and across-study risk of bias (limitations in study design and execution or methodological quality), inconsistency (or heterogeneity), indirectness of evidence, imprecision of the effect estimates and risk of publication bias (see Section 14.2.2 ), as well as domains that may increase our confidence in the effect estimate (as described in Section 14.2.3 ). The GRADE system entails an assessment of the certainty of a body of evidence for each individual outcome. Judgements about the domains that determine the certainty of evidence should be described in the results or discussion section and as part of the ‘Summary of findings’ table.

The GRADE approach specifies four levels of certainty ( Figure 14.2.a ). For interventions, including diagnostic and other tests that are evaluated as interventions (Schünemann et al 2008b, Schünemann et al 2008a, Balshem et al 2011, Schünemann et al 2012), the starting point for rating the certainty of evidence is categorized into two types:

- randomized trials; and

- non-randomized studies of interventions (NRSI), including observational studies (including but not limited to cohort studies, and case-control studies, cross-sectional studies, case series and case reports, although not all of these designs are usually included in Cochrane Reviews).

There are many instances in which review authors rely on information from NRSI, in particular to evaluate potential harms (see Chapter 24 ). In addition, review authors can obtain relevant data from both randomized trials and NRSI, with each type of evidence complementing the other (Schünemann et al 2013).

In GRADE, a body of evidence from randomized trials begins with a high-certainty rating while a body of evidence from NRSI begins with a low-certainty rating. The lower rating with NRSI is the result of the potential bias induced by the lack of randomization (i.e. confounding and selection bias).

However, when using the new Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool (Sterne et al 2016), an assessment tool that covers the risk of bias due to lack of randomization, all studies may start as high certainty of the evidence (Schünemann et al 2018). The approach of starting all study designs (including NRSI) as high certainty does not conflict with the initial GRADE approach of starting the rating of NRSI as low certainty evidence. This is because a body of evidence from NRSI should generally be downgraded by two levels due to the inherent risk of bias associated with the lack of randomization, namely confounding and selection bias. Not downgrading NRSI from high to low certainty needs transparent and detailed justification for what mitigates concerns about confounding and selection bias (Schünemann et al 2018). Very few examples of where not rating down by two levels is appropriate currently exist.

The highest certainty rating is a body of evidence when there are no concerns in any of the GRADE factors listed in Figure 14.2.a . Review authors often downgrade evidence to moderate, low or even very low certainty evidence, depending on the presence of the five factors in Figure 14.2.a . Usually, certainty rating will fall by one level for each factor, up to a maximum of three levels for all factors. If there are very severe problems for any one domain (e.g. when assessing risk of bias, all studies were unconcealed, unblinded and lost over 50% of their patients to follow-up), evidence may fall by two levels due to that factor alone. It is not possible to rate lower than ‘very low certainty’ evidence.