- The Inventory

Support Quartz

Fund next-gen business journalism with $10 a month

Free Newsletters

Can art make us better problem solvers?

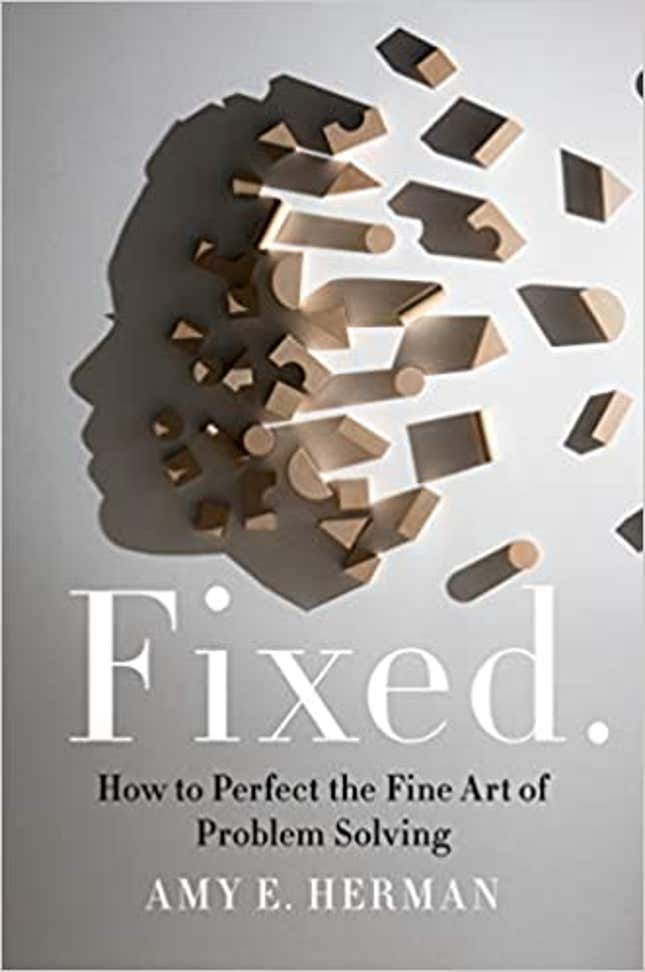

In the search for novel ways to hone our problem-solving skills , spending time with a work of art may be the simplest and most effective training, according to the art historian Amy Herman.

Herman has been teaching professionals —homicide detectives, medical students, lawyers, and engineers—to read paintings as a way to improve their analytical faculties. “Art provides a safe space outside of ourselves to analyze our observations and convert those observable details into actionable knowledge,” Herman writes in the introduction to her new book, Fixed. How to Perfect the Fine Art of Problem-Solving .

Doing so can help us understand how and why things go wrong and, more importantly, how to fix them, she explains.

Putting the lesson into practice

In her book, Herman explains how to navigate a complex composition, step by step.

Consider Théodore Géricault’s grisly painting, The Raft of the Medusa .

Herman writes:

Take in its scope, notice its details, count things, catalog what you think might be going on. Then, take a breath and let your mind wander. What did the chaos of the preceding scene bring to mind? A natural disaster? A human-made catastrophe? The current state of your country? Maybe you were reminded of more personal scenarios: office drama, an argument at home that got out of hand, Zoom Thanksgiving.

No matter who you are or where you live, chances are you can relate to the desperation depicted above.

A crucial skill in Herman’s approach is the art of noticing—the ability to quell the impulse to pick up our mobile devices and to pause long enough to ruminate on the details of a visual spectacle before us. This is particularly salient in the age of short attention spans , where the average museum-goer spends less than 30 seconds looking at a work of art .

Looking at art also attunes us to nuance and ambiguity, explains Herman. It’s a skill that’s critical for hostage negotiators to managers trying to read the room.

“The optimal way to look at art, whether alone or with others, is to look at the object first, speak after looking, and only then, read the label,” Herman tells Quartz. “My hope is that by learning to look at art in a structured way inspires and refreshes critical inquiry and that same model will be applied to when confronting problems in need of solutions.”

Herman, who once led the education department at the Frick Collection in New York City, insists that there’s no shame in “using art to study ourselves and the problems we face every single day.” “Art can be many different things to many different viewers,” she argues. “If the power of a work of art can be channeled to enable a viewer who does not have a background in art or art history to approach their vocation in a different and more expansive way, why not unleash that?”

Quartz at Work is available as a newsletter. Click here to get The Memo delivered directly to your inbox.

📬 Sign up for the Daily Brief

Our free, fast, and fun briefing on the global economy, delivered every weekday morning.

- Data Analytics

- Data-Visualisation

- Certified Information Security (CISM) / CISSP / CISA

- Cisco-(CCNP)

- Google Cloud

- Microsoft Azure

- Product Management

- Web Development

- Java Script

- Strategic Thinking

- Time Management

- Working from Home

- Entrepreneurship

- Interpersonal Communication

- Personal Branding

- Graphic Design

- UX/UI Design

- Motion Graphics

- Film & Video

- Copy Writing

- Life Coaching

- Team Building

- All Articles

- Data Science

- IT/Cloud Certifications

- Online Teaching

- Programming

- Soft Skills

Stay in touch!

Never miss out on the latest articles and get sneak peeks of our favorite classes.

September 4, 2023

How Drawing Unlocks Creativity and Problem-Solving

Drawing is a universal form of expression that transcends language barriers and taps into the innate human desire to communicate visually. Beyond its artistic allure, drawing possesses a remarkable ability to enhance problem-solving skills and unleash creativity. The act of problem solving drawing by putting pencil to paper isn’t just reserved for artists; it’s a cognitive tool that can spark innovation and lead to novel solutions.

In this article, we will explore how drawing contributes to problem-solving and the ways in which it can be harnessed as a powerful thinking tool.

Table of contents:

How does drawing improve problem-solving skills , what is a problem-solving chart , how do you draw a problem-solving diagram , additional benefits of drawing , do you have to be an artist to draw , drawing exercises to enhance creativity for beginners , conclusion .

Drawing is a unique medium that engages both hemispheres of the brain, facilitating holistic thinking.

When faced with complex problems, the act of problem solving drawing forces you to externalize your thoughts and visually map out connections, making abstract concepts more tangible. This visual representation often reveals patterns, relationships, and gaps that might not be as evident through traditional verbal or text-based approaches.

Problem solving drawing enables you to approach challenges from a fresh perspective, breaking down barriers that hinder innovative thinking. ‘

You might also like: 151 Drawing Ideas with Examples for Inspiration

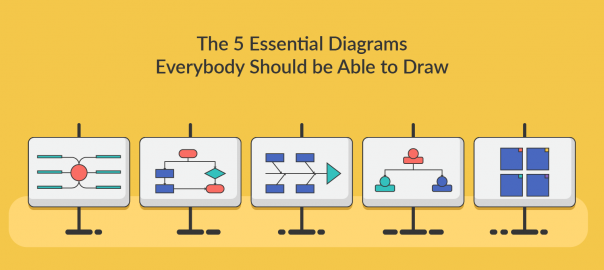

A problem-solving chart is a visual framework that organizes information and ideas related to a specific problem or challenge. It can take various forms, such as flowcharts, mind maps , or concept diagrams.

These charts serve as dynamic tools to capture and analyze the various elements of a problem, providing a clear overview and aiding in identifying potential solutions.

The process of creating a problem-solving chart encourages structured thinking and encourages you to explore different angles of a problem.

Basics of drawing and sketching for beginners

Drawing for Beginners

The Art of Public Speaking

When faced with complex problems, the act of problem solving drawing forces you to externalize your thoughts

Using problem solving drawing to create a diagram involves several steps:

- Define the Problem: Clearly articulate the problem you’re trying to solve. This will serve as the central focus of your diagram. Gather Information: Collect relevant data, ideas, and concepts related to the problem. Jot down keywords, phrases, and concepts that come to mind.

- Choose a Format: Depending on the complexity of the problem, choose a suitable format for your diagram. Mind maps are great for brainstorming, while flowcharts can illustrate processes and decision trees.

- Organize the Information: Begin placing the collected information in the diagram. Connect related ideas with lines or arrows, indicating relationships and dependencies.

- Analyze and Iterate: Step back and assess the diagram. Does it highlight potential solutions? Are there gaps or missing connections? Make adjustments as needed.

- Identify Solutions: Use the insights gained from the diagram to identify possible solutions. The visual representation can help you see connections that lead to innovative ideas.

Problem solving drawing offers a myriad of additional benefits. It enhances focus and concentration, allowing you to immerse yourself in the creative process.

Drawing also serves as a stress-relieving activity, providing a means to unwind and detach from the demands of everyday life.

Moreover, it boosts visual thinking skills, enabling you to grasp complex concepts and information more readily.

Absolutely not.

The beauty of drawing as a problem-solving tool is that it transcends artistic skill.

You don’t need to create intricate masterpieces; your goal is to externalize your thoughts and ideas visually. Simple sketches, doodles, or diagrams can effectively convey your thinking process.

The act of drawing is more about engaging with the problem and unleashing creativity than producing gallery-worthy art.

You might also like: 21 Best Drawing Courses

If you’re new to drawing but eager to enhance your creativity, there are several exercises that can help kickstart your artistic journey.

Begin with basic shape doodling.

Set aside time to doodle various shapes, lines, and patterns. This exercise not only gets your hand accustomed to the motion of drawing but also encourages your brain to think visually.

Another exercise is blind contour drawing.

Choose an object and draw it without looking at the paper. This exercise improves hand-eye coordination and forces you to observe details.

Additionally, try drawing from memory.

After studying an object or scene, put it out of sight and attempt to draw it from memory. This exercise sharpens your observation skills and encourages you to focus on essential details.

Lastly, experiment with negative space drawing .

Instead of drawing the object itself, draw the spaces around and within it. This exercise challenges your perception and helps you see objects in a new light.

By engaging in these drawing exercises regularly, you’ll not only improve your artistic skills but also ignite your creativity in various aspects of problem-solving and thinking.

Drawing isn’t solely reserved for those with an affinity for art; it’s a potent tool that can unlock creativity and enhance problem-solving skills. Problem solving drawing enables you to approach challenges from a fresh perspective, providing a visual representation of intricate ideas and connections.

As you craft problem-solving charts, you organize information, identify patterns, and explore innovative solutions. Beyond its cognitive benefits, drawing offers stress relief, improved concentration, and heightened visual thinking skills.

Embrace drawing as a thinking tool, regardless of your artistic prowess, and harness its potential to transform the way you approach problems and ignite your creative spark.

Related content:

- How To Be More Creative With Sketching

- 7 online painting classes

- drawing for beginners: Learn to draw online

- 21 Drawing Supplies and Tools Essentials

Trending Articles

Don't forget to share this article!

The largest marketplace for live classes, connecting and enriching humanity through knowledge.

Related Articles

Digital Advertising: Navigating the Future of Marketing

Astronomy vs Astrology: Know the Difference

Unlocking the Potential of BlackRock Bitcoin ETF: A Comprehensive Guide

Hot Gift Card Deals 2024

How Sour Candy Can Help Calm Anxiety

How Many 5 Letter Words are There in the English Language

Using Visual Arts to Foster Creative Thinking Skills

“A drawing is the three-way relationship between substance, surface and body. It activates the relationships between the eye and the hand, the hand and the tool, the body and the drawing surface. The elements of the drawing itself, the drawing marks on the empty page and between the eye of the artist and what lies beyond what the artist can actually touch.” Amy Sillman

“ I am not creative ” – “ I can’t draw !”, are the most common reactions I encounter when people learn that I’m working as an artist. Regrettably, the main focus of art production appears to revolve around a “beautiful outcome”, the ability to draw or paint a stunning picture. You are either good or not and if you aren’t, why carry on?

This misconception results in the profound benefits of engaging with the visual arts on your emotional health, the fostering of creative thinking skills, and art as a tool to strengthen psychological resilience being mostly overlooked.

Both art appreciation and the actual creating of visual arts can have a significant impact on the development of a young person. In fact, your brain will benefit from engaging with art at any stage of your life and you neither have to be a good artist nor know a lot about art to reap the rewards from experiencing it.

“Creativity requires the courage to let go of certainties” – Erich Fromm

Creativity requires strong self-believe, the ability to persevere despite failure and setbacks, it’s about following an idea, an intuition, it requires untiring curiosity. Carrying on, despite of what other people might say or of what your peers might say. It’s about seeing information in a different light, putting unrelated elements together, noticing patterns, inconsistencies, using everyday experiences, getting inspired by anything and everything and the need to try things in a different way over and over again.

Although, you might have an end goal in view, the creative path won’t be linear and can’t always be planned out from start to finish. There isn’t one correct answer, more of an open-ended answer to an open-ended problem. Being creative involves failing a lot, failure is indeed not a bad outcome, failure makes you look at all the pieces in a new light, it requires you to look at them differently, you need to find a new way of solving your answers and posing your questions.

In line with an easy to follow universal marking and evaluation system, most school settings teach children to deal with problem solving in a specific way, including the need to follow certain steps and leading to one correct answer. As Dr. Zorana Ivcevic Pringle, a research scientist at Yale Centre for Emotional Intelligence, explains, “ If a task poses a question with a specific set of steps required to answer it, there is no space for creativity. ”

Another stumbling block in acquiring creative thinking skills is “creative mortification”, a term used by psychologist Ron Beghetto, describing an unwillingness or outright refusal to participate in any creative work after having experienced negative feedback on your work, and lacking the ability to deal with the resulting negative emotions felt. This usually happens to children at a very young age, when they find it more difficult to regulate their emotions and don’t yet have the necessary resilience to deal with this negative experience.

In my opinion, a young person losing faith in their artistic creativity early on, will very likely refrain from using the arts as a tool for acquiring creative thinking skills. As a result, they might be less likely to explore their own ideas in other non-art related areas, as their motivation for exploring creative thinking has been discouraged at an early age.

There are individuals, who from the outset have a highly creative mind, a talent or inborn creativity, which makes them explore the world in a different and more creative way. Being creative is part of who they are, their very essence. Studies researching the connection between attention and creativity have brought to light that truly creative individuals appear to have a “diffused or “leaky attention”, which translates into their having great difficulties in filtering out external sensory stimuli whilst trying to carry out cognitive tasks. In contrast, individuals with lower creative talent are able to block out distractions from their environment and give full attention to the task at hand.

Although having a “leaky attention” would be a real disadvantage in particular exam situations, it nevertheless leads to creative individuals being able to notice more in their environment and doing so on a continuous basis. They will notice things most people overlook; therefore, the creative mind has more information to play with and furthermore the ability to create new and unusual connections between various seemingly unrelated chunks of information.

The creative brain has the ability to better regulate thoughts and behaviours whilst being involved in a creative task, getting into a state of flow and in this setting tuning out all distractions. The psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi described flow as “ being completely involved in an activity for its own sake. The ego falls away. Time flies. Every action, movement, and thought follows inevitably from the previous one, like playing jazz. Your whole being is involved, and you’re using your skills to the utmost. ”

In addition, creatives tend to be better equipped at managing their emotions, especially with regards to negative feedback, and are able to just carry on with their vision. They have a higher level of resilience when faced with obstacles; these obstacles often leading them to be even more creative.

What Happens in Your Brain When You are Drawing?

In a study conducted to investigate whether drawing could increase the brain’s plasticity and using fMRI (Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging) scans to establish what is going on in the brain, Dr Lora Likova, worked with a cohort of congenitally blind individuals, who had been taught to explore raised line tactile images with the help of their fingers and learnt for a week to draw from memory.

Congenitally blind people don’t show any activation in the visual area of their brain, however those participants who had learned to draw from memory showed a “dramatic enhancement of the activation, very specific to the primary visual cortex or what would have been the primary visual cortex in these congenitally blind subjects. ” Dr Likova’s study shows a rather remarkable and fast means of neural plasticity using drawing.

In a different study, researchers wanted to find out if art appreciation and active art production would have different effects on the brain. Neurologists Anne Bolwerk and Christian Maihofer, observed that the visual art participation group showed greater psychological resilience and a higher level of functional brain connectivity than the art appreciation cohort.

The study noted stronger connections of brain areas and an involvement of brain regions which are activated during introspection; the employment of cognitive strategies in order to reduce negative emotional experiences; the regulation of emotions; greater self- awareness; and enhanced memory processing. It has been noted that the functional connectivity of most of these areas are vital for a healthy resilience.

Whilst more research needs to be conducted in this field, the neurologists put this phenomenon down to the fact that “ the production of visual art involves more than mere cognitive and motor processing described. The creation of visual art is a personal integrative experience – an experience of “flow”, – in which the participant is fully emerged in a creative activity. ”

This intriguing connection between emotional and creative skills has led to researchers from Yale University exploring this feature in the development of children. A course that was carried out over six sessions with children from selected primary schools in Santander, Spain, showed a significant increase in creative behaviour, enhanced skills for problem finding and idea generation. Interestingly, a follow up two months later, demonstrated that these positive effects started diminishing, which indicates a need for a continuous arts based intervention to achieve longer lasting results.

Students who score higher on the TTCT Torrance Test of Creative Thinking are more likely to have been exposed to art and art education. They are generally more willing to take greater risks, have a more pronounced imagination, show higher levels of creativity and, are finding it easier to engage with cooperative learning and expression.

Nonetheless, visual arts appreciation should not be underestimated, various studies have found that viewing paintings leads to an activation of a range of brain regions and in particular regions of the brain that are associated with “vision, pleasure, memory, recognition and emotions” as well as areas which deal with the “processing of new information to give it meaning”.

Neurobiologist Semir Zeki scanned the brain activity of people looking at art and was able to detect the release of dopamine, a chemical neurotransmitter that plays a part in how we feel pleasure. Looking at art appears to create a sensation similar to falling in love or looking at a loved one.

The perception of art is a very aesthetic experience which stimulates areas of the brain that are mainly associated with visuo-spatial exploration and attention. Viewing art activates your mirror neurons; brain cells that respond to the observation of a performed action. It can lead to what is called “embodied cognition” – one of the reasons you get drawn into a painting – perhaps making you feel afloat like Botticelli’s angels in “The Birth of Venus” or almost to feel paint splatters hit the canvas standing in front of a Pollock.

Furthermore, visiting museums and art galleries has been shown to lower stress levels, improve memory, and engage and strengthen your empathy. A study conducted by the University of Westminster found that study participants who visited an art gallery during their lunch break reported a lowering of their stress levels, this observation could be supported by findings that the cortisol levels of the participants fell after a 35 minute gallery visit. Visiting an art gallery can help with recovery from mental exhaustion in the same way as spending time in nature.

In 2017, a study carried out on preschoolers found that cortisol levels, and thus stress, were lowered if the children were given the chance to participate in music, dance and visual arts classes.

Research carried out by the University of Arkansas found that children who visited galleries and viewed art, improved their critical thinking skills and had an improved historical empathy. Viewing works of art helped them to understand what life would have been like for people who lived in a different time and place. These experiences contribute to a general openness to diversity, different ways of living, thinking, and experiencing of the world. The children also showed a much higher level of tolerance, as well as an enhanced appreciation, interest and understanding for art and culture. In a world where emotional intelligence is increasingly being understood as being essential to happiness and fulfilment, visual arts can play a fundamental part in supporting people of all ages.

Visual arts engagement should play an important part in every child’s learning experience. By freely experimenting with a variety of materials, whilst simultaneously expressing their emotions and ideas, these experiences will help to form important connections in the developing brain of a child. As outlined in this article, the arts represent a perfect vehicle for engaging a young person with the concept of creativity. It will become natural to them to approach a problem from more than one point of view, and to know that there might be multiple answers to a specific problem, or question. They will be able to apply an open mind and not only work with past experiences. The combined experience of art production and art appreciation will maximise the effect art can have on a young person, be it brain development; mental wellbeing; experiencing flow; strengthening creative thinking skills; learning psychological resilience or becoming a more empathetic, tolerant open-minded thinker.

For advice on how to support children in art, see advice sheet PA414 Supporting High Learning Potential in Art and Design and the blog Art: Adding Extra Colour to the High Potential Learner’s World

Bolwerk, A., Dorfler, A., Lang, F. R., Mack-Andrick, J., Maihofner, C. (2014). How art changes your brain: Differential effects of visual art production and cognitive art evaluation on functional brain connectivity. PLoS ONE. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0101035

Bowen, D. H., Greene, Jay P., Kisida, B. (2014). The educational value of field trips. Education Next ,14 (1). https://www.educationnext.org/the-educational-value-of-field-trips/

Craft, A., Cremin, T., Burnard, P., Chappell, K. (2007). Developing creative learning through possibility thinking with children aged 3-7. In: Craft, A., Cremin, T., Burnard, P. (Eds.), Creative learning 3-11 and how we document it . Trentham.

Clow, A. (2006). Normalisation of salivary cortisol levels and self-report stress by a brief lunchtime visit to an art gallery by London City workers. Journal of Holistic Healthcare 3. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/252281628_Normalisation_of_salivary_cortisol_levels_and_self-report_stress_by_a_brief_lunchtime_visit_to_an_art_gallery_by_London_City_workers

Ebert, M., Hoffmann, J. D., Ivcevic, Z., Phan, C., Brackett M. A. (2015). Teaching emotion and creativity skills through art. A workshop for children. The International Journal for Creativity & Problem Solving , 25 (2), 23-35.

Fostering creativity: T he preschool teacher. (n.d.). [Online Lesson] in The Virtual Lab School. https://www.virtuallabschool.org/preschool/creative/lesson-4

Geirland, J. (1996). Go with the flow. Wired Magazine ,4(09). https://www.wired.com/1996/09/czik/

Hofmann, J., Ivcevic, Z., Maliakkal, N. (2020). Emotions, creativity, and the arts: Evaluating a course for children”. Empirical Studies of the Arts. Sage Journals. https://doi.org/10.1177/0276237420907864

Ivcevic Pringle, Z. (2020, April 3). Creativity at home in the times of pandemic. Dr. Zorana Ivcevic Pringle . https://www.zoranaivcevicpringle.com/post/creativity-at-home-in-the-times-of-pandemic

Ivcevic Pringle, Z. (2020, April 3). Manage emotions to innovate. Dr. Zorana Ivcevic Pringle . https://www.zoranaivcevicpringle.com/post/manage-emotions-to-innovate

Ivcevic Pringle, Z. (2020, April 3). Building your creative muscle. Dr. Zorana Ivcevic Pringle . https://www.zoranaivcevicpringle.com/post/building-your-creative-muscle

Ivcevic Pringle, Z. (2020, April 3). The how of creativity. Dr. Zorana Ivcevic Pringle . https://www.zoranaivcevicpringle.com/post/the-how-of-creativity

McDonald, H. (2019, February 15). The cognitive balancing act of creativity. Psychology Today . https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/time-travelling-apollo/201902/the-cognitive-balancing-act-creativity

Phillips, R. (2015, March). Art enhances brain function and well-being. https://www.healing-power-of-art.org/art-and-the-brain/

Skov, M., Vartanian, O. (2014). Neural correlates of viewing paintings: evidence from a quantitative meta-analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging data. Brain and Cognition , 87, 52-56.

The benefits of art on memory and creativity (2018, April 17). Invaluable . https://www.invaluable.com/blog/benefits-of-art/

Zambon, K. (2013, November 12). How engaging with art affects the human brain. American Association for the Advancement of Science . https://www.aaas.org/news/how- engaging-art-affects-human-brain

Zeidel, D. W. (2014). Creativity, brain, and art: biological and neurological considerations. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience , 8(389). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4041074/

About the author: Nina Vangerow is an artist, educator and online content creator with a MA in Ancient History. Teaching art and craft classes, Nina has developed a particular interest in the correlation between the arts, creativity and mental wellbeing. As a mother of a teenager with high learning potential, she has been a Potential Plus UK member and volunteer since 2012.

Share This Page

Related posts.

He’s Not a Bad Kid, Just Misunderstood: Ben’s Story

How to Survive a High Learning Potential Christmas

Christmas Gift Ideas the High Learning Potential Way

Summer Reading Challenge Reviews 2023

Charlie’s Story – An Outsider at 2 Years Old

Privacy overview.

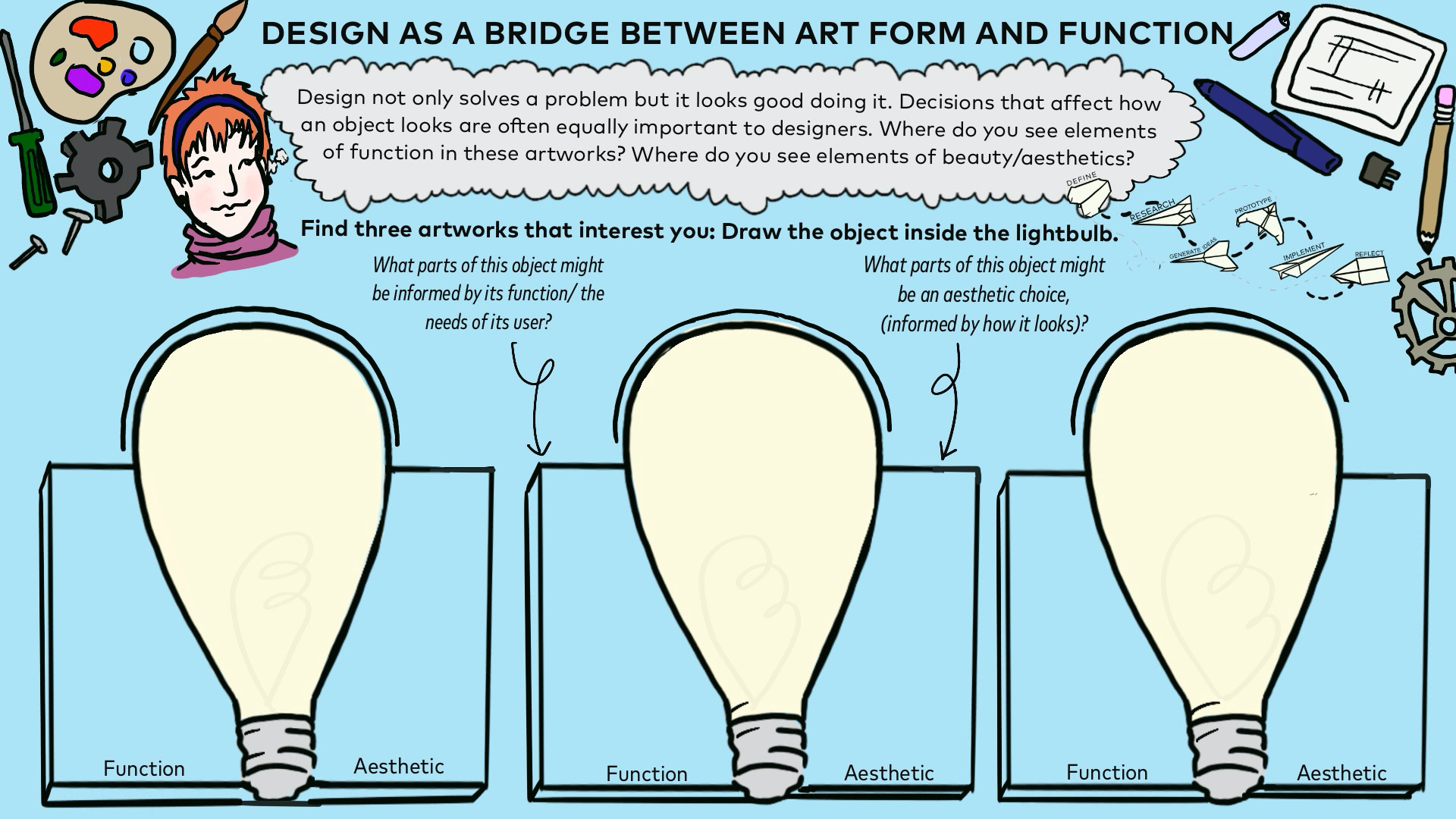

Design Thinking

Design is endlessly trying, refining, improving until slowly something begins to emerge that is so ingenious that it looks like magic if you don’t know what went on before: that’s what evolution does. – Designer, Joris Laarman

Design is all around us, whether it takes the form of objects and spaces, images and interactions, or systems and processes. Beyond meeting a need, design can experiment with forms, techniques, or materials to be an expression of a concept or beauty.

In this Web Quest, you will explore notions of design and learn about a creative problem-solving process called Design thinking. How do artists solve problems? Use these activities and videos at home, online, or in the classroom to spark curiosity, conversation, and critical thinking.

Web Quest includes:

- A scavenger hunt activity, where students identify how objects in the Denver Art Museum collection speak to both aesthetics and function

- A lesson plan inspired by Basket Chair (includes two videos, a facilitator’s guide and supportive materials for kids to dive into dive into design related concepts)

Print out this scavenger hunt or insert it into the learning management system of your choice to create an interactive activity prompting kids to look closely at the artworks found in the object gallery below.

Object Gallery

Web Quest Resources

- Design Thinking: Facilitator's Guide (web)

- Design Thinking: Facilitator's Guide (PDF)

- Design Thinking: Instructions for Kids (PDF)

- Scavenger Hunt Worksheet (PDF)

- Slides for Elementary (PowerPoint)

- Slides for Elementary (Google)

- Slides for Middle and High School (PowerPoint)

- Slides for Middle and High School (Google)

- Library Resources

The DAM established Creativity Resource thanks to a generous grant from the Morgridge Family Foundation. Featured activities are supported by funding from the Tuchman Family Foundation, The Freeman Foundation, The Virginia W. Hill Foundation, Sidney E. Frank Foundation – Colorado Fund, Colorado Creative Industries, Margulf Foundation, Riverfront Park Community Foundation, Lorraine and Harley Higbie, an anonymous donor, and the residents who support the Scientific and Cultural Facilities District (SCFD). Special thanks to our colleagues at the University of Denver Morgridge College of Education. The Free for Kids program at the Denver Art Museum is made possible by Scott Reiman with support from Bellco Credit Union.

Design Thinking: Artists Solve Problems is supported by Herman Miller Cares.

What it Takes to Live as an Ar..

Creative arts develop problem solving skills, the easiest seo tips for onlin...

- by Kaylee Osuna

- Artists Featured Articles

Public education often considers fine arts classes and programs expendable luxuries. This article explores how beneficial the fine arts are in education.

It is no secret that, when faced with recession pressures and budget cuts, most American public school systems decrease funding for fine arts programs or cut them entirely. Reasons cited for these decisions include fine arts do not generate much money for schools, nor are they part of the school’s core curriculum; therefore, they are expendable. Unfortunately, educational leaders are often not able to maximize the full educational and economic possibilities of the fine arts, and consequently, students’ learning opportunities suffer.

FINE ARTS PROGRAMS CAN GENERATE MONEY FOR SCHOOLS

Many American public schools sponsor annual plays and musicals, and despite performances being limited to a handful per semester, they do generate income for the school through ticket sales. Although they do require a considerable amount of time and practice to perfect these performances, as well as need a limited budget for props and supplies.

However, school drama performances can be increased to generate revenue and stay within budget by sponsoring ticketed events that do not require as much time or resources to produce. Such an example is orchestrating a comedy improv troupe, where only a few simple props and little preliminary preparation are necessary.

In addition, most schools completely neglect to showcase the talents of their budding visual artists. Sponsoring frequent school-wide art shows, auctions, and awards can generate additional funds for public schools, as well as provide enriching educational experiences for students.

For example, until visual art students reach college, few have opportunities to apply to an open call for entries or learn how to promote and set up an art exhibition. Learning these skills early gives visual arts students an edge over many art students who begin to navigate the exhibition circuit in their later college years. Furthermore, participating in art shows provides high school students who intend to study visual art with valuable experience to add to their college applications.

FINE ARTS PROGRAMS ARE BENEFICIAL TO STUDENTS’ LEARNING

Matthieu Comoy for Unsplash

Art education authorities Eric Oddleifson and Judith Simpson have analyzed numerous studies conducted in urban and suburban school systems involving increased integration of the arts into classrooms. These studies overwhelmingly found that when the arts are incorporated into daily curricula, positive results are observed which transcend all subject areas. Examples include increased student creativity, better problem-solving abilities, more options to express ideas, open-mindedness and tolerance for different people and ways of thinking, and increased joy and motivation to learn.

Oddleifson’s writing also references the theories of Harvard psychologist Howard Gardner, who has conducted additional research advocating fine arts in schools. Gardner hypothesizes that there are seven total forms of intelligence: visual/spatial, musical, kinesthetic, interpersonal, intrapersonal, verbal, and logical. The first five intelligence forms are predominantly found in fine arts. However, most American school systems’ core curricula focus on subjects involving verbal and logical intelligence, such as English and science.

Removing fine arts from educational institutions not only deprives students of a well-rounded education but also denies students the ability to maximize their intellectual capacities. Just as art students require a scientific understanding of the natural world so they can render plants and animals with photo-realistic accuracy, wouldn’t science students benefit from creative stimulation to better generate ideas for hypotheses and experiments?

For students who are passionate about the fine arts, little is more devastating than extensive cutbacks or complete removal of fine arts classes. Furthermore, students who prefer other subjects do learn beneficial skills from fine arts, and the fine arts can contribute financially to public schools. Let us remember the true purpose of education and enrich students with a broad range of subjects so they may reach their full potential.

ART TEACHES MAKING JUDGMENTS ABOUT QUALITATIVE RELATIONSHIPS

Martina_Bulkova for Pixabay

Through the development of qualitative intelligence, art teachers assist students to raise their consciousness and increase their capacity to interpret their world. Drawing on the work of Dewey, Eisner explains that the creation, appreciation, and understanding of visual form in general, and visual art in particular, is a mode of activity he considers to be a form of intelligence.

“The production and appreciation of visual art is a complex and cognitive-perceptual activity that does not simply emerge full-blown on its own.” [Eisner. 1972, p113]

DEFINITION OF QUALITATIVE INTELLIGENCE

Dewey advanced the idea that intelligence is the quality of an activity performed on behalf of inherently worthwhile ends. On this account, intelligence is a verb, a type of action, not a quantifiable noun, something that one possesses. For Dewey, intelligence is how a person copes with a problematic situation.

QUALITATIVE INTELLIGENCE AS PROBLEM SOLVING

When applying this notion of “intelligence” as problem-solving to the way students learn to make meaning through the modality of visual art, Eisner develops a descriptive argument [2002, p114]. He describes a process whereby students identify a problem, select qualities, and organize them so that they function expressively through a medium.

- A student who sculpts paints or draws is solving a problem

- He or she must find a way to transform, in some medium, an idea image, or feeling

- They start with a blank piece of paper, a lump of material, or data in electronic form

- The student uses this raw material to articulate a vision

- During this process, they hope to be responsive to the consequences of personal actions when managing material so that it functions as a medium

- When manipulating the media, the artist learns to be aware of the happy accident that is inevitable in the creation of artworks

- Through this learning strategy, it is hoped that the student will develop an ability to manage anxiety, frustration, and tension. The ability to forestall closure allows for the possibility of openness to a moment of unity and cohesion

- Students learn to recognize moments when the whole work comes together

- During the process, students will develop an ability to cope with thousands of interactions among visual qualities. Moments of cohesiveness, clarity, and unity will emerge through the child’s use of material

- Upon reflection students (perhaps in conversation with others) will conceive of her artistic purpose and recognize the meaning

Eisner calls the ability to problem solve in this way qualitative intelligence because it deals with the visualization of qualities expressed in images. The activity is directed at the creation and control of these qualities. It is generally recognized that artists work with seven elements of design.

MEDIATION THROUGH ARTISTIC THOUGHT

Rahul Jain for Unsplash

Qualities are mediated through thoughts, which are managed through the process, which terminates in a qualitative whole. A qualitative whole is an art form that expresses an idea or emotion by how those qualities have been created through the organization.

People use this form of intelligence throughout daily living. Artistic decision-making occurs when people select furnishings for the home, design a brochure, create a website layout, or decide upon what clothes to wear. The ability to do this is not simply given at birth, as one aspect of a genetic bundle of attributes. Rather, qualitative intelligence is an educable mode of expression that develops through experience and (hopefully) with guidance.

Intelligence, in this sense, is capable of expansion and through expansion, it expands the potential understanding of students. Through the arts, teachers assist students to raise their consciousness and increase their capacity to interpret their world.

The tendency to separate art from intellect and thought from feeling has been a source of difficulty for the field of art education. One of the results of this distinction is a lessening of the value of the creative arts fields of inquiry within the curriculum. Such a dichotomous distinction does not do justice to art or education.

For another presentation of this view see The Philosophy of a Creative Arts Educator Wisdom is the Legacy Left by Harry Broudy.

About the author : Kaylee Osuna is a professional writer at EssayWriterCheap.org , who loves to read and write about Psychology. She has participated in different conferences and presentations to gain more knowledge and experience. Her goal is to help people cope with their problems.

Kaylee Osuna

Click here to cancel the reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

ARTEXPO NEW YORK 2024

ABN Subscribe

THE REDWOOD ART COLLECTIVE

Why an education in visual arts is the key to arming students for the future

Professor, Chief Cultural Officer, Cultural Precinct, The University of Western Australia

Disclosure statement

Ted Snell does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Western Australia provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

Visual skills are essential for a sophisticated workforce, yet we offer so little education in the vital skills of learning to see and developing the ability to interpret and critique our image-saturated world.

In the global marketplace, the economy of the cultural industries is growing in importance, and visual expression is part of everyday communication. For Australia to compete in this marketplace, visual acuity, visual literacy and the ability to communicate visually must be recognised as an equally fundamental skill to those of language and numeracy. These can all be taught through grounding in the visual arts.

There is a growing body of international and Australian research that demonstrates a direct link between an arts-rich education from an early age and an increase in students’ confidence, their intellectual abilities across all learning areas, problem-solving skills, and general life skills.

The visual arts provide a vital cultural component and deliver on a range of important skills otherwise missing from the curriculum. They also provide a platform for addressing the important issues of our times; they build self-reflective, empowered communities; and, let’s not forget, they also bring great joy and reassurance in times of anxiety.

Future skills

As the 2016 World Economic Forum report on The Future of Jobs predicted, the top necessary skills required for the fourth industrial revolution will be complex problem-solving, critical thinking and creativity, alongside emotional intelligence and cognitive flexibility.

Read more: Fourth industrial revolution: sorting out the real from the unreal

Highly specialised, rigidly structured degree courses aimed at a specific job outcome will be redundant in this emerging environment. But degrees with a strong visual arts foundation will ensure individuals will flourish, not flounder, under the impact of disruptive technologies and when confronted by new ways of working.

Steve Jobs said he employed people at Apple with passion , particularly for problem-solving, “having a vision, and being able to articulate it so people around you can understand it, and getting a consensus on a common vision”. It’s why Jobs also said he wanted to see applicants’ drawing portfolios before he employed them.

Work in the visual arts also generates new images and develops new ideas. These have the potential for commercialisation at a time when the government is pursuing its agenda on innovation and promoting the creative industries. For instance, several of the residencies through the Australian Network for Art and Technology Synapse program have led to further research and potential commercialisation.

Ever-expanding digital platforms will also need more and more creative content, requiring that all employees in every profession have opportunities to develop these skills.

We must then ensure that the creative arts are a core component of the curriculum so that all students will become more resourceful and better equipped to successfully manage change.

As well as teaching us vital skills, the arts also enrich, enhance and transform individual lives. This is the intrinsic benefit of the arts, which also has a value to the wider community.

It’s not just about individual pleasure, though. The arts change attitudes, and by so doing they can transform society. An education in the visual arts provides students with a better chance of achieving these shifts in our collective consciousness.

Read more: Friday essay: can art really make a difference?

Embedding arts at universities

Studying the visual arts provides the hothouse environment that brings the instrumental and intrinsic benefits of the arts into unison. It becomes a forum in which to explore new possibilities and critique existing presumptions and preconceptions about art and life.

Our challenge is to find ways of integrating the visual arts into the core curriculum and at the heart of the student experience. This includes an object-based learning approach to teaching (for instance, including study of artworks and artefacts).

Internships, courses that integrate the arts within other disciplines, and collaborative projects designed for students across discipline areas are just some examples of strategies already employed at universities.

That is our challenge, to work collaboratively across academic disciplines to re-imagine the role of the visual arts in the 21st century university.

This article is an edited extract from a keynote address to the Australian Council of University Art & Design Schools (ACUADS) annual conference being held in Perth on September 27-28.

- Universities

- Visual arts

- Arts education

Audience Development Coordinator (fixed-term maternity cover)

Data and Reporting Analyst

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

21st-Century Skills in the Art Classroom

As you prepare students to become lifelong learners, it’s important to equip students with a variety of skills. 21st-century skills are those students need to navigate an ever-changing, global society. Many schools districts are asking teachers to use these skills in their curriculum. The good news for art teachers is that we teach a unique subject where students can creatively apply what they have learned in other classes.

So, how can we facilitate the 21st-century skills in the art classroom?

Communication and collaboration.

What are they? Communication is a necessary skill we use every day. In art class, students can communicate verbally, as well as writing, and most often, visually. They decipher meaning from contemporary and historical artworks while creating a message in their own unique projects.

Collaboration is the ability to work together effectively with others. In the art classroom, collaboration is incorporated through group projects.

In The Art Room: One way to encourage communication in the art room is to show students how artists have communicated throughout history. Introduce examples of cave paintings, Egyptian art, Greek pottery, etc. Students can see how art allows us to communicate information visually. Then, they can apply this knowledge of a visual narrative to inspire their own artwork.

Try having your students work in groups or pairs to create an altered photograph. Explain to students that their altered photograph should convey a snapshot of a story. Students will need to be able to act as designers and photographers to complete this project.

Partners or groups can create scenes of battle, friendship, or celebration. Show them examples from Greek pottery depicting scenes from mythology. The whole story isn’t necessarily featured, only a key moment or scene. Each student should begin the project with an initial idea for their story, also called a narrative. Some of these ideas may evolve through the collaboration process as their peers offer helpful suggestions. Allow students time to communicate and feel comfortable making changes as they work.

- First, the project designer needs to envision how the finished photograph will look.

- Next, the designer will need to communicate their vision clearly to their photographer.

- Then, have the designer create a rough sketch of what they envision to give their photographers an idea of composition, angle, and distance.

- Finally, the photographer will use the sketch to best capture the designer’s idea with the camera.

Innovation and Creativity

What are they? As art educators, we know innovation and creativity go hand in hand. Innovation and creativity will solve the problems of today and the future. Our students need to be prepared with new solutions to both old and new problems. In the art classroom, we encourage our students to think creatively with every single project. Their ideas inspire us as educators to keep innovating and creating!

Thinking creatively comes naturally to some students, while others struggle to generate new ideas. Try to inspire creativity by providing a variety of examples, resources, and processes. Students may develop ideas better through brainstorming, collaboration, and the application of personal experiences.

In The Art Room: Consider giving students a simple project with a few parameters and lots of opportunity for creative additions. Use the inspiration of a famous artwork or tradition. For example, introduce students to The Nian Monster for Chinese New Year. While students won’t be making replicas of Chinese parade decorations, each student can make an original paper dragon based on their own creative legend.

- First, have students write a story about their dragon. The stories can range from grand adventures to endearing friendships.

- Next, students may work together to write stories that correspond with one another. As we already know, collaboration can inspire some very creative ideas!

- Then, students can create a paper dragon using a variety of materials as unique as their written story. Some dragons may have elaborate tails, beards, or wings, while others might appear ferocious with two heads and sharp teeth. The colors, shapes, and lines should reflect the dragon’s personality and story details.

- Finally, have your students share their stories with each other.

Critical Thinking and Problem-Solving

What are they? Critical thinking and problem-solving might sound like topics for a scientist or an engineer, but they can also easily be found in the art room! Critical thinking and problem-solving use both the right and left sides of the brain.

In The Art Room: Try giving your students a sculpture project with fewer instructions and added challenges.

- First, introduce your students to three-dimensional works by Auguste Rodin, Henry Moore, and Claes Oldenburg.

- Next, have your class brainstorm what the sculptures might be made of and how the artist communicated meaning.

- Then, after the students’ discussion, ask them to create an original sculpture in groups of three to five. Your minimal instructions should be to design a free-standing sculpture out of cardboard. The colors, lines, and shapes are to reflect a mood chosen by the students. You could incorporate some literature by reading the Dr. Seuss book, My Many Colored Days , as an excellent example of how we interpret different colors as specific moods.

- To continue, students will work together to agree on a single mood and decide how to best communicate that emotion with shapes, colors, and lines. They will collaborate as they cut their shapes out of cardboard and paint them with tempera paint. Once the shapes are dry, students may add lines with oil pastels.

- Finally, the challenge: Each group should try to come up with a way of assembling the pieces to create a free-standing sculpture without the use of glue! Some students may try using pipe cleaners and hole punches to connect the shapes. While others may join the shapes by cutting slits in the cardboard to balance pieces against one another.

This project can be extremely messy, wild, and at times, overwhelming. You could easily eliminate some of the issues by being more hands-on and giving specific demonstrations, but the point of this project is to encourage your students to do some of that learning on their own through the process. As their teacher, you do not always have to solve the problems for them. Instead, encourage students to explore, think critically, and problem solve collaboratively.

Technology and Informational Literacy

What are they? The abilities to safely and effectively navigate online and use technology for the greater good are essential to today’s students. Technology and informational literacy have become more and more integrated into the arts. Through internet research, software programs, and social media, students can connect with art content like never before.

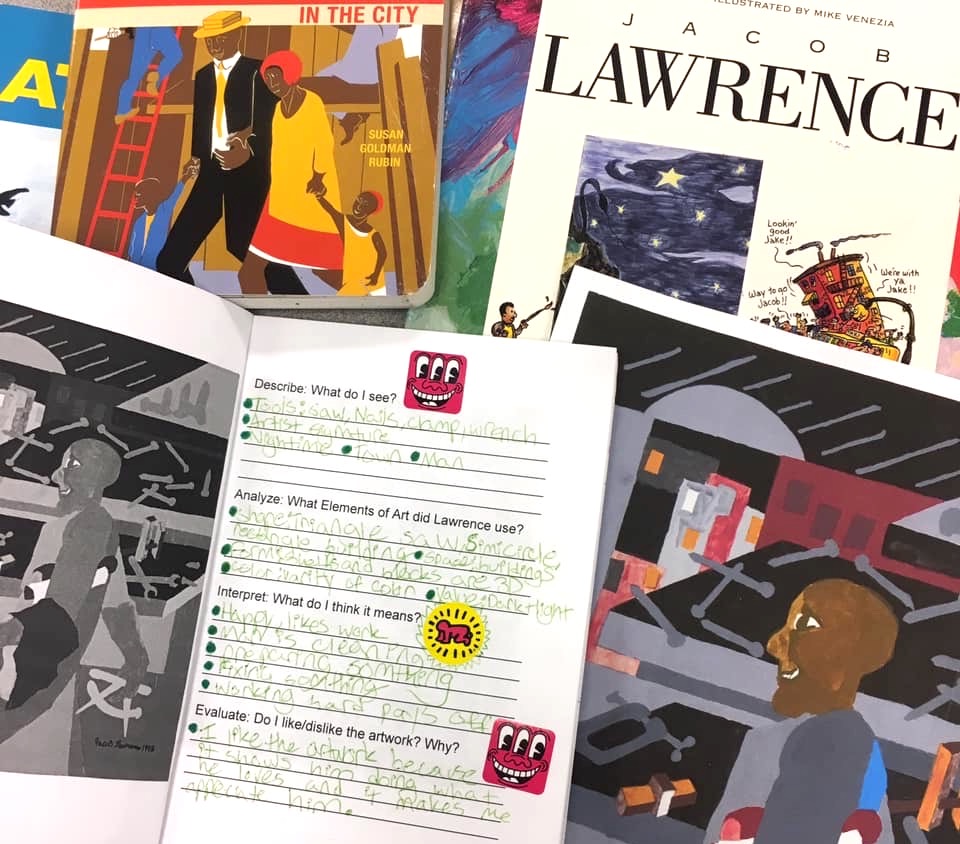

In The Art Room: Use artists affiliated with the Harlem Renaissance to inspire a research-based art project:

- First, introduce students to influential musicians and poets of the Harlem Renaissance.

- Then, rather than explaining an artist’s or culture’s perspective yourself, look for a primary source online. Use technological resources like YouTube to show students how good content can be used to learn. Students will appreciate hearing information directly from the source. For a Harlem Renaissance unit, you may choose this video featuring an expert professor from the University of Colorado in Boulder. The video was produced by teens, which may inspire your students, as these young filmmakers created the documentary for the National History Day competition.

- Next, ask your students to research information about three specific artists of the Harlem Renaissance: Jacob Lawrence, Romare Bearden, and Lois Mailou Jones, or discover their own. At the end of class, students will answer questions about their chosen artist and reflect on this information in writing.

- Finally, each student will choose one artist to inspire an original art project. When the projects are completed, students can explain, in writing, how the artist inspired their work. This type of project helps show how well students can apply research.

Final Thoughts

21st-century skills are essential for students to succeed in the Information Age. The National Art Education Association agrees, “the visual arts provide opportunities for all students to build their skills and capacity in what the Partnership for 21st-Century Skills calls ‘Learning and Innovation Skills,’ specifically Creativity and Innovation; Critical Thinking and Problem-Solving; and Communication and Collaboration.”

As art educators, we already promote many of these 21st-century skills every day, as we focus on individual student needs and project-based learning. In doing so, we can best prepare students for today’s global society.

How do you promote 21st-century skills in the art room?

What projects are encouraging your students to think critically and problem solve?

How are students collaborating in your art room?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.

Jordan DeWilde

Jordan DeWilde, a high school art educator, is a former AOEU Writer. He aims to encourage students’ individual creativity through a diverse and inclusive curriculum.

No Wheel? No Problem! 5 Functional Handbuilding Clay Project Ideas Students Love

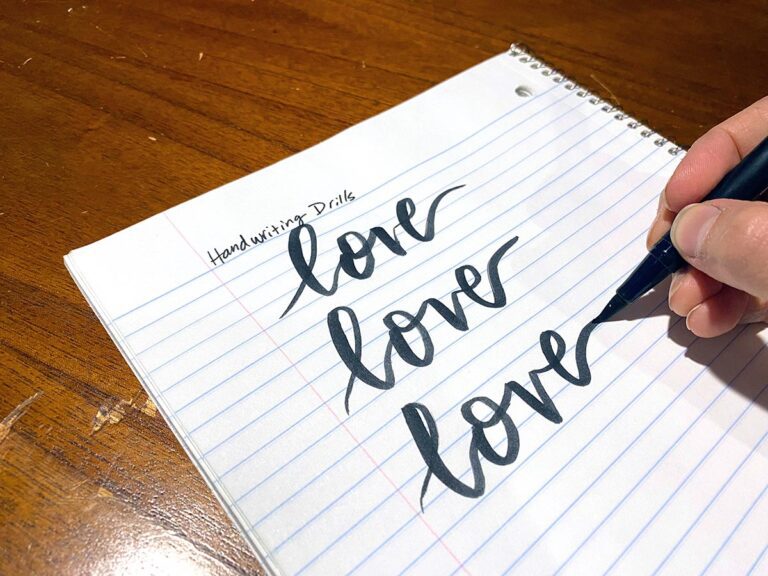

Love Letters: 3 Amazing Ways to Integrate Calligraphy, Cursive, and Typography

Embracing the Magic: A Love Letter to Pinhole Photography in the Art Room

A Love Letter to Yarn: 5 Reasons Why Art Teachers Are Obsessed

National Art Education Association

Unofficial Informational Website

Showing Art Students The Value Of Problem Solving

Creating art isn’t the place to go if you have a problem solving problems. It seems to be a never ending process of attempting to bring something new into the world and not messing up and creating mud instead.

A teacher has to make sure the students see the value in being able to solve problems and there is help.

Table of contents

The fundamentals, sources of problem solving, give the students problems, art solving life problems.

Young people are of course constantly learning the basics of survival and being part of a community. As they study and apply what they’re learning in art, they’ll run into one problem after another.

This has to be handled as soon as possible because problem solving 1 skills will be needed just to survive. With art, you’re working with materials and techniques that messy, somewhat dangerous, and expensive. For example, a student using charcoal will have to deal with the potential smudging that can easily happen if a shirtsleeve or clumsy hand brushes across the paper.

Here, students have to work with the medium and take their lumps along the way so it doesn’t happen again. With watercolor, there is no mercy. Which colors to use and how to keep from making a mistake are for starters. Watercolor is usually unforgiving if a mistake is made and only the best can do any kind of repair on a watercolor painting once it’s goofed up.

Students should be taught not to become angry 2 or exasperated, but instead take things calmly and see where what went wrong and try to remedy it and prevent such from happening in the future. Don’t even talk about oils. One has to be a junior chemist to master oils. The various brushes, oil pigments and chemicals can lead to disaster if one doesn’t keep one’s eyes open.

That all being said, there are other problems to solve they need to be prepared for. Setting up displays, learning how each of the humanities and sciences dovetail into art so that the final work is professional and has intrinsic value. As a student continues to solve one problem after another their confidence builds and new problems don’t seem so daunting.

Believe it or not, one awesome venue for teaching a student about problem solving is in video games. The well made games teach patience, conserving resources, picking the right tool, and more. The skills needed to complete the game teach the student which faults and pluses in their character that are needed to avoid or resolve problems.

One teacher, Diane Jaquith of the Burr Elementary School in Newton, MA points out several vital issues regarding students and problem solving. Actually she had a problem with introducing the term, “problem finding”. She realized the students might be confused so she took things one step at a time.

First engaging the students to discuss problems in general and what sort of problems they encountered doing art. This then led to her slowly introducing problem finding and soon the students were up to snuff. She added to her method and all went well.

The teacher should present problems for the students to solve. The teacher should take careful eye to see how each student reacts. When faced with a problem do they immediately engage in grumpy or fearful behavior? If so you’ll need to nip it in the bud right there.

Emphasize that if one gives up emotionally then one gives up everything and no progress made. See if the student uses reference material to clear up any misunderstandings and also to see how their art can be applied with less hassle. From concept to execution, a work of art will present problems.

Questions about composition and lighting, texture and more will arise and they’ll have to make a choice. The teacher should be there to encourage and guide but not to overwhelm the student or they won’t learn self initiative. Once the student realizes they can solve a problem and that no one will punish them for making a mistake or tease them, they’ll look forward to tackling problems and become far more self reliant in all areas of their lives. Parents will notice the change for the better and that will be a big feather in any teacher’s hat.

Now comes the big game. Students realizing that they can produce a work of art that could solve other problems. For example doing a painting of a problem area in town. It may be a dilapidated building that no one has taken responsibility for. No one could figure out what to do with it or how to take it down.

Then here comes one of your students finding the structure of interest. They draw it or paint it up and some city official or engineer comes by and see s the art. They realize that the painting shows something about the structure they hadn’t seen before.

It gives them an idea on how to remedy the situation and give credit to the painting and artist. A kid experiencing this kind of scenario will then know that they can make an impact on the world to solve a delicate problem with artwork skills. Armed with this knowledge they’ll forge ahead to new problems to be solved the creative way.

As stated earlier, problem solving is part of life. We all do it a hundred times a day. Kids using their art that presents problems and can be used to showcase and solve problems is a wellspring we all can drink from. In the end, once accustomed to facing and solving problems, the student will be stronger and greater asset to themselves, the school, family, and community.

- Problem solving app (ItsGoneWrong) Itsgonewrong.com

- Handling anger (Parenting.com) Teach Your Child to Handle Anger

About The Author

Professor David Percival

Director of AHVC programme, and specialist in art and technology, including presence research, mixed and virtual reality.

Try searching for

- Concerts and Events

- Employment / Jobs

- Faculty and Staff

Applications are still open for Arts Camp and Arts Academy. Programs fill quickly—submit your app today!

The art of problem solving.

Four Interlochen alumni share how their arts backgrounds inform their work in the sciences.

Aaron Parness tests one of his creations during his tenure at NASA.

NASA heliophysicist Holly Gilbert.

Biomedical engineer and Boston University professor Joyce Wong.

Independent global public health and development consultant Timothy Thomas.

In times of crisis, many cling to science for the concrete solutions it offers to our problems. There is a certain comfort in the regimented nature of science: Its laws, its data tables, its tried-and-true experimental methods.

But there are limits to science. Occasionally, we face a crisis that defies the scientific method, an issue whose solution will not be observable, measurable, and repeatable.

In these moments, we look to our creative problem-solvers, those who search for outside-the-box for answers to life’s most challenging riddles. Many of these individuals are artists-turned-scientists who cut their teeth in creative pursuits before pursuing a life of theories and equations. We caught up with four Arts Camp and Arts Academy alumni to learn how their creative pasts inform their scientific careers.

Developing discipline and focus

For all four alumni, one of the most important lessons their musical training taught them was discipline.

“The self-discipline that I learned by being involved with the arts at Interlochen definitely helped me develop patience and discipline in solving scientific problems,” said Holly Gilbert (IAA 86-88), a NASA heliophysicist and Interlochen Arts Academy cello alumna.

Aaron Parness (IAC 91-93), an Interlochen Arts Camp violin alumnus and principal research scientist on Amazon’s robotics and AI team, agrees. “The arts improved my ability to focus deeply for long periods of time—a skill I honed during practice sessions,” he said. “One of my greatest assets at work has been my ability to concentrate intensely on a complex task. Reaching that state of 'flow' is something I probably first experienced playing the violin.”

For independent public health and development consultant Timothy Thomas (IAA 76-78), a lesson from an arts instructor continues to guide his work in the scientific sphere. “I met an acting teacher who said, ‘be ruthless in your pursuit of the specific,’” Thomas said. “That has always governed how I work: doggedly pursuing the specific, trying to find what’s real and authentic in any piece I create. That commitment to specificity is important for anybody in any profession—whether they’re a surgeon, a stockbroker, or a farmer.”

Learning to play with others

While musical training often takes place in the privacy of a practice room, orchestras and chamber ensembles provide opportunities to learn the importance of collaboration.

“Playing the cello and piano taught me how to work together on a team, like in chamber music,” said Joyce Wong (IAC/NMC 78-81), a professor of biomedical engineering at Boston University. “I learned how important it is to trust your partners and pull your weight in a project.”

For Parness, the orchestra—with different players performing different parts—served as a model for how individuals with diverse skills can collaborate to solve one problem. “Playing in an orchestra provided a fertile learning opportunity for teamwork and coordinated effort,” Parness said. “All of my projects today rely on teams of scientists and engineers that bring different skills to the problem.”

Disrupting the scientific method

Science is by nature analytical. However, all have found ways to inject their creativity into the sciences.

“Being embedded with incredibly creative people at Interlochen has given me a unique perspective in attacking science,” Gilbert said. “I think I learned early on that innovation and creativity are intimately related, and it's incredibly important to leverage innovation at a place like NASA.”

Gilbert’s problem-solving method echoes the musician’s task: Applying privately honed techniques in an ensemble setting. “I first approach problems from all angles, making sure I understand the core of the problem,” she said. “Then I consult with others, preferably a diverse group of scientists, to develop potential solutions. Often, one solution is not obvious—nor is it the only approach.”

Wong, too, recognizes the parallels between practice and science. “I like to break the problem up into smaller pieces, like I would if I were learning a difficult musical piece,” she said.

Creativity is at the core of Parness’s approach to problem-solving, a technique known as iterative design. “When confronted with a difficult problem, I try to brainstorm as many possible solutions as I can before I start to pass any judgement,” he said. “In this divergent stage of the process, it's about being creative and generating outside-the-box ideas. After my team has exhausted ourselves, only then do we start to prioritize and rank what we want to prototype.”

Thomas, who frequently collaborates with scientists, understands the importance of his unique voice in the search for solutions. “Scientists see things in black-and-white, in terms of ‘it works’ or ‘it doesn’t’,” Thomas said. “What I add to the conversation is a reminder that there are many ways to look at a problem. There are factors that influence the problem that we may not know, and we have to explore the unknowns and be honest in our commitment to see all points of view and facets of the problem. A creative mind brings that into a question that would otherwise be solved in a binary way.”

Embracing a growth mindset

In a swiftly changing professional field, Parness leans on the growth mindset that his musical training helped develop. “Music provided an opportunity to internalize the process of improving with practice,” he said. “Today, I'm not afraid to dive into a subject where I'm not an expert, like machine learning and artificial intelligence in the past year, because I know that I can learn and get better over time. Being fearful of taking on new challenges is something I've seen hold back many of my colleagues.”

Maintaining balance

Music and art remain a durable part of all their lives and an important counterpoint—or enhancement—to their scientific careers.

“I listen to music while grant writing, namely Mozart’s Requiem ,” Wong said. “I also enjoy going to concerts. I would love to play chamber music again.”

Gilbert recently picked up the cello again after more than 30 years away from the instrument. “It definitely provides a dimension to my life that is hard to get from other things,” she said. “My daughters are also musical, so we have music in the house often. Music really is fundamental to feeding my soul and making my life full.”

Parness, too, enjoys sharing the arts with those closest to him. “My wife, Alma, and I subscribed to the LA Philharmonic for many years, and we regularly attend the theatre with my sister Rachel,” he said. “Recently, it's been incredibly fun introducing our two daughters to music, dance, and visual art. I'm looking forward to lots of daddy-daughter duets and trios!”

Thomas remains perhaps the most involved in the arts: When not consulting on public health, he performs semi-professionally as a classical singer, takes acting classes, teaches private voice lessons, and is a member of the board of several New York City arts organizations.

“I’ve never really left the arts,” he said. “ It’s always been an integral part of my life. I just stopped trying to make my living in it.”

More Like This

April 5, 2024

March 27, 2024

March 25, 2024

March 13, 2024

February 20, 2024

What is Art Education: Exploring its Purpose and Impact

Time to Read:

What is Art Education

Are you curious about the power of art education? Have you ever wondered why it’s so important to have art in the classroom?

In this article, we will explore what is art education. From its benefits on individual growth and development to its ability to prepare students for life and work, we will dive into the fascinating world of art education .

Join us on this journey as we discover the true value of art education and how it can make a difference in students’ lives everywhere. Get ready to be inspired and amazed!

Key Takeaways

- Art education covers a wide range of visual and performing arts disciplines.

- The main goal is to teach students the creation, production, and appreciation of various art forms.

- Art education promotes creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving skills.

Table of contents

The Disciplines in Art Education

Art education encompasses a variety of disciplines that involve learning, instruction, and programming based on visual and tangible arts.

It includes performing arts such as dance, music, theatre, and visual arts like drawing, painting, sculpture, and design.

Art education aims to teach students how to create, produce, and appreciate various art forms, as well as to understand and evaluate the work of others.

Through art education, students are exposed to diverse artistic practices, where they can develop their creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving skills.

Furthermore, it provides opportunities to explore cultural heritage and appreciate the importance of creativity in society.

Integrating arts into education allows learners to express themselves and discover their talents.

Understanding Art Education

Art education is a vital educational experience that fosters creativity and artistic expression and offers various cognitive and emotional benefits.

It prepares students for the challenges in life by enhancing their problem-solving skills, visual-spatial abilities, and collaboration capabilities.

Incorporating arts in education allows you to explore your creative potential while providing a foundation for understanding various art forms.

Whether it is music, dance, visual arts, or theatre, arts education is crucial in broadening your perspective and nurturing your imagination.

As you delve deeper into the art world, you will learn that it is a powerful medium to express emotions, thoughts, and ideas, transcending cultural and linguistic barriers.

The essence of arts learning lies in its ability to facilitate the acquisition of artistic skills and instil a sense of appreciation for diverse art forms.

This helps you better understand various cultures, traditions, and histories, fostering empathy and respect for others.

Moreover, exploring, creating, and appreciating art can be therapeutic, enabling you to manage stress and emotional turmoil effectively.

To sum up, understanding art education is vital for holistic personal growth, encompassing cognitive, emotional, and social development.

So, embrace the world of arts, experience art education’s benefits , and appreciate the richness it brings to your life.

Importance of Art Education

Art education is crucial in fostering creativity and promoting a well-rounded learning experience.

As you explore the importance of art education , you will find numerous benefits that contribute to the overall development of every student.

One of the primary reasons art education is essential is because it helps students engage with school and reduce stress.

Participating in various art forms, you can experience a sense of accomplishment, personal growth, and a deeper connection with your emotions.

This engagement enhances your learning experience and helps you better manage stress.

Incorporating art education into your curriculum aids in developing social-emotional and interpersonal skills .

Through artistic expression, you learn to communicate effectively, work collaboratively with others, and build empathy toward diverse perspectives.

These skills are essential for success in both personal and professional life.

A robust arts-learning environment enriches your educational experience by stimulating critical thinking and problem-solving skills.

Art education challenges you to view the world differently and develop innovative solutions to complex problems.

This exposure to diverse art forms fosters cognitive flexibility and adaptability, which are highly valued in today’s fast-paced world.

Partaking in art education equips you to handle constructive criticism. In the creative process, receiving feedback and refining your work is integral.

By embracing constructive criticism, you develop resilience and learn to persevere in facing challenges.

In conclusion, art education is vital to creating a well-rounded academic experience.

With numerous benefits, ranging from stress reduction to the development of interpersonal skills, it is clear that art education plays an essential role in every student’s overall growth.

Pedagogy in Art Education

As an art educator, your primary role is to foster the development of creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving skills in students.

Pedagogy in art education is vital to this role, as it outlines the methods and techniques used to teach art in a K-12 setting.

Choice-based pedagogy is a popular approach in art education, where you, as the art teacher, design learning activities that support students as artists and provide them with authentic choices to respond to their ideas and interests through art-making [1] .

This approach encourages student autonomy, allowing them to explore various materials and techniques and their artistic visions.

Another critical aspect to consider in your pedagogy is culturally responsive teaching. As an art teacher, you must acknowledge and respect the diverse backgrounds of your students.

By incorporating their unique cultural experiences into your teaching and adapting your methods to ensure that all students can connect with the material, you are contributing to an inclusive art education environment.

This can be done by showcasing diverse artists, discussing various art forms from different cultures, and incorporating culturally relevant themes into projects [2] .

You should also strongly understand discipline-specific knowledge and techniques to teach art effectively.

Your coursework and professional development should emphasize art history , contemporary artistic practices, and various media and materials.

This helps you introduce students to a wide range of artists and movements, enabling them to critically engage with the world of art.

As a teaching artist, you may also work in community settings, collaborating with schools, museums, or other organizations to bring art education experiences to various age groups and populations.

Your pedagogy might need to be flexible while working as a teaching artist, adapting to the unique needs and goals of each project or setting.

Collaboration and community engagement become essential elements of your teaching approach in these contexts.

Remember, your pedagogy in art education should be confident, knowledgeable, and clear, reflecting your dedication to fostering creative growth in your students while remaining attentive to their needs and backgrounds.

Doing so contributes to developing a new generation of artists and creative thinkers.

The Role of Art Educators

As an art educator, your primary responsibility is to provide students with a well-rounded understanding of the visual and tangible arts.

This includes teaching various art forms such as drawing, painting, sculpture, and design works and performing arts like dance, music, and theatre [3] .

Your role goes beyond teaching the techniques and skills required to create art. It would help if you also instilled in your students an appreciation for and understanding of the cultural , historical , and social contexts in which different art forms have evolved.

This helps students develop critical thinking abilities and better comprehend the significance of art in society.

In addition to being knowledgeable in your subject matter, as an art educator, you should cultivate a creative and supportive learning environment for your students.

This includes encouraging experimentation, curiosity, and self-expression while providing constructive feedback to help students grow as artists.

Actively engaging in arts advocacy is another crucial aspect of your role as an art educator.

You can promote the value of art education by communicating its benefits to parents, school administrators, and community stakeholders, highlighting how it contributes to students’ overall engagement and achievement in school National Art Education Association .

In summary, as an art educator, your role encompasses teaching a variety of art forms , nurturing creativity , fostering critical thinking , and advocating for the importance of an arts education in students’ lives.

Visual and Performing Arts

You’ll explore various disciplines in art education, including visual, performing, media , and contemporary art .