- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Zealot: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth by Reza Aslan – review

H ad Reza Aslan not been interviewed in a gauche and silly fashion on Fox News, I doubt this book would be being reviewed at all. Zealot , to be as kind as possible, trudges down some very well-worn paths; its contribution to studies of Christianity is marginal bordering on negligible; and its breathless style suggests hasty thought.

To take just one example: the Romans are said to display "characteristic savagery" on page 13 and are "generally tolerant" on page 14. Aslan contends that an illiterate "day laborer" called Jesus was part of an insurrectionary tradition in Israel, and the story of this Che Guevara of the early Middle East was co-opted by the dastardly Saul of Tarsus, aka Saint Paul, who defanged the zealot and turned him into an apolitical metaphysician. Frankly, parts of it are closer to Jesus Christ Superstar than any serious undertaking.

If one were minded to follow this line, there are plenty of books that do a more scholarly job, and are written more eloquently. From Nazareth to Nicaea by Geza Vermes should be at the top of the list; AN Wilson's biographies of Jesus and Paul for the more narratively minded; Albert Schweitzer's Geschichte der Leben-Jesu-Forschung of 1906 to put this tradition in context; and Gustavo Gutiérrez Merino's The Theology of Liberation to show how the ideas might be activated without leaving behind the "cosmological Christ". In fiction, Naomi Alderman's The Liars' Gospel deals with many of the same ideas with both scepticism and sensitivity, while Richard Beard's Lazarus is Dead is far more imaginative in its analysis of the Jesus stories.

Aslan's argument is undermined by various facts, which even he admits. The earliest references to Jesus are from Paul, wherein he is not just one of many Messianic aspirants, but more even than that. That the gospels were written later creates his second problem. If, as Aslan contends, the gospels are both infected with Pauline theology and a source for the aboriginal Jesus cult, then how can he tell when they are wrong and when they are right?

That he frequently invokes the Q hypothesis – the idea that behind the gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke lurks an incontrovertible true document – shows just how out of touch with theology he is. If Aslan's version were true, surely the wicked Paul would not have left behind references to show how he subverted a genuine radical movement. Aslan requires Paul to be cleverer and stupider at the same time.

But these are niggles compared with the major flaw in this work. Aslan simultaneously disparages and relies on the gospels. If a verse fits, he snatches it: if it contradicts his thesis he takes it as proof of the unreliability of the source. When he requires Celsus, the vehement antagonist of Christianity, to be true, he takes his work as such (without ever mentioning we only have Celsus in fragments preserved in Origen's rebuttal); when he wishes it otherwise, Celsus is "so clearly polemical he cannot be taken seriously". He does not actually read the texts. Rather, he sifts them, making the story less important than the detail.

The gospels are not history. The idea that they are a wholly new form of literature might, in itself, be reason enough for us to read them more subtly. Aslan refers to Mark's gospel as being written in a "coarse, elementary Greek" – which nevertheless is supposed to appeal to cultural, Hellenised Jews rather than illiterate Galileans. One might, on a similar basis, say that Irvine Welsh not writing like David Hume is proof that he was not Scottish. Mark may not write like Xenophon, but the idea that he had a different audience in mind does not mean he is lacking in literary skill. Rather, his skills are more oblique and nuanced. Mark lacks the infancy narratives of Luke and the resurrection stories of Matthew because they were already known – things are written down as they pass from memory. But Mark, like the other Synoptic gospels and the gospel of John, has what I would call the divine comedy that other writings of the period lack.

Where else do we have such empathetic misunderstanding? Jesus is not impatient, but he is wry as time and again the disciples fail to get the message. Socrates was tetchy by comparison. Even Mark's Gospel includes sly interventions: when Pilate asks the crowd if they want Barrabas or Jesus, the earliest readers would have found the pun.

"Barabbas" was a name taken by zealous anti-Roman terrorists, and means "Son of the Father" – so the Son of the Father and "my ain Dad's bairn" are exchanged, literally. It also means that Jesus is crucified instead of the kind of terrorist Aslan claims he was, and crucified under the very name the Pharisees had sought to use as justification for his death – there is a profound, sardonic humour in Pilate's "What I have written, I have written".

When it comes to the resurrection, there is a peculiar hiatus. One would think that any historical reconstruction of the life of Jesus would have to deal, at least briefly, with the apostles' conviction that Jesus had returned from the dead.

Aslan gives numerous examples of Jewish, anti-Roman, and violent individuals who are historically attested to in the period before and after the life of Jesus. His description of the wood manages to ignore the tree. Jesus is not just less violent than his peers; he is the least violent of them. Compared with the Maccabees or the Sicarii, Jesus is strikingly unwilling to shed blood, stopping, for example, Simon Peter from murdering the guards sent to arrest him. Even the cleansing of the Temple stops short of death. The problem with the comparative method Aslan uses is it overlooks important discrepancies in favour of broad-brush correlations.

There is an odd intemperance about the tone of this book, with vociferous assertion often replacing argument. It seems, in its overstatements and oversights, to yearn for the very kind of furore in which it is now embroiled.

- History books

Reza Aslan on Zealot, Fox News and Richard Dawkins

Even by fox news's standards, is this its most embarrassing interview.

Zealot by Reza Aslan rushed into print after Fox News controversy

Comments (…), most viewed.

Call Today! (800) 777-2227

Campus Security (803) 807-5555

My CIU Make a Gift

Reza Aslan’s ‘Zealot’: Part 2: The Book Review

I don’t think Aslan had himself in mind when wrote that statement, but you should be warned: the Jesus in Zealot is Aslan’s own false construction.

His central thesis is that the Jesus of history, and the God Jesus believed in, demanded violence in the face of political and religious oppression. Here’s one of the relevant passages:

[F]or those seeking the simple Jewish peasant and charismatic preacher who lived in Palestine two thousand years ago, there is nothing more important than this one undeniable truth: the same God whom the Bible calls a “man of war”(Exodus 15:3), the God who repeatedly command the wholesale slaughter of every foreign man, woman, and child who occupies the land of the Jews, the “blood spattered God” of Abraham, and Moses, and Jacob, and Joshua (Isaiah 63:3) the God who “shatters the heads of his enemies,” bids his warriors to bathe their feet in their blood and leave their corpses to be eaten by dogs (Psalm 68:21-23)—that is the only God that Jesus knew and the sole God that he worshipped. (122, emphasis in the original.)

The problem that I have with this passage is indicative of the problem that I have with the way Aslan constructs his Jesus. He constantly picks and chooses which verses from the Bible he uses to support his claim that Jesus was a warrior messiah whose goal was to violently overthrow the Roman and religious establishment. He peels away all passages that conflict with his construction so that he can show us what Jesus was truly like.

Well, what Aslan thinks Jesus was truly like.

Now, I have no problem with picking and choosing certain verses over others. I admit, I do it all the time. In fact, the historical Jesus picked verses, too. I’m convinced that followers of Jesus must pick and choose certain verses of the Bible over others, and that we need to learn how to pick and choose those verses in the same way that Jesus did.

What Is the Greatest Commandment? And Who Is My Neighbor?

As Michael Hardin points out in his book The Jesus Driven Life , (and if there is one book you should read about the historical Jesus this year, it is The Jesus Driven Life) when Jesus gained popularity, some of his rivals tried to test him with a question about interpretation. “Teacher,” a lawyer asked, “which commandment in the law is the greatest?” This is a crucial moment in the life of Jesus, because, as Hardin states, “At stake in this conversation is how one interprets the Jewish Scriptures and how one lives out that interpretation” (37). Aslan’s Jesus would have responded as a man of war, “Shatter the heads of your political and religious enemies! Kill them! Set yourselves free from your oppressors!”

To be honest, I would have loved for Jesus to have said that. Deep down, I want Aslan’s violent God because I can control that God. I know that that God is for me and against my enemies. The problem is that Jesus didn’t quote anything in the Scriptures about a violent God to describe the greatest commandment. Instead, he referred to love. “You shall love the Lord your God with all of your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind…And a second is like it: ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself.’ On these two commandments hang the law and the prophets” (Matthew 22:34-40). So, according to Jesus, the law and the prophets are there to guide us in loving our neighbors, who we know from Matthew chapter five include even our enemies: “You have heard that it was said, ‘Love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ But I say to you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you.”

Of curse, Aslan never quotes Jesus specifically saying, “pray for those who persecute you” because it doesn’t fit with Aslan’s construction of zealously violent Jesus.

Aslan explains away passage like “Love your neighbor/enemy” by claiming that Jesus meant his Judean audience should only love their Judean neighbor. Oddly, he does refer to the story of the Good Samaritan to show that Jesus critiqued the religious authorities, but Jesus told this parable in response to the question, “Who is my neighbor?” The point, of course, is that the Samaritan is the one who proves to be the neighbor by showing love to the man in need. Here, Jesus is expanding his followers’ understanding of neighbor. To many of his hearers, a Samaritan was a political and religious rival. In fact, Josephus reported that Judeans and Samaritans had many violent confrontations throughout the first century. The story of the Good Samaritan was Jesus’ narrative way of expanding our understanding of “neighbor” so that our love for neighbor embraces everyone, including our national enemies.

Zealous Like Elijah?

According to Aslan, Jesus was zealous like the prophet Elijah. He says that Elijah was, “A fearsome and uncompromising warrior for Yahweh…[who] strove to root out the Canaanite god Baal among the Israelites” (128-129). Famously, Elijah challenged 150 priests of Baal to a contest. Two altars with offerings were constructed. The priests of Baal would pray that Baal would consume their offering with fire and Elijah would pray the same to Yahweh. The priests of Ball fervently prayed day and night, but nothing happened. Then it was Elijah’s turn. The first time he prayed to Yahweh a great ball of fire fell from heaven and consumed the offering and the altar. Then, in the ultimate act of “My God is bigger than your God!” Elijah seized and slaughtered all 150 priests, because, as Aslan avers, “he was ‘zealous’ for the Lord God Almighty’” (129, quoting 1 Kings 19:10).

Connecting that story from Elijah to Jesus is fallacious. After all, the closest comparative story in the Gospels is found in Luke 9:51-56. When Jesus sent messengers to the Samaritans, the Samaritans refused to welcome them. When the disciples James and John saw this, they said to Jesus, “Lord, do you want us to command fire to come down from heaven and consume them?” The parallel to Elijah is obvious, made even more so by the fact that many ancient manuscripts end the question with, “as Elijah did?” (See New Interpreter’s Study Bible , 1873.) The disciples, like Aslan, expected Jesus to be zealous like Elijah was zealous . But Jesus had the same response whenever his disciples desired violence. As Luke says, Jesus “turned and rebuked them. Then they went on to another village.” Again, Aslan never mentions this story, because it is a counter-narrative to the Elijah and Baal story, and it challenges any notion of a violent Jesus.

Those Who Live By the Sword Die By the…Oh Right…

Aslan’s retelling of the events at the Garden of Gethsemane is egregious beyond measure. He states that Jesus commanded his disciples to bring swords because he knew a fight would break out. After all, according to Aslan, “Jesus was no fool. He understood what every other claimant to the mantle of the messiah understood: God’s sovereignty could not be established except through force” (122). And so as Jesus was arrested in the garden, his disciples looked on, and, as Aslan recounts the story, “One of them draws his sword and a brief melee ensues in which a servant of the high priest is injured” (146). The impression that Aslan provides is that Jesus wanted his disciple to respond with violence. Of course, he never quotes Jesus rebuking his errant disciple, “Put your sword back into its place; for all who take the sword will perish by the sword” (26:52), nor does he quote Luke’s version of Jesus’ arrest, “Then one of them struck the slave of the high priest and cut off his right ear. But Jesus said, ‘No more of this!’ And he touched his ear and healed him” (22:50-51).

It turns out that Jesus was no fool. He knew that those who live by the sword die by the sword, that violence only breeds more violence, and that the best way to respond to violence is to say “No more of this!”

Resurrected for Vengeance or Peace?

As I continued to read Zealot , one question kept nagging me. Aslan frequently mentions that there were numerous failed messiah’s during the first century, who all attempted a violent revolution against Rome. If Aslan is right in his assertion that Jesus was a failed violent revolutionary messiah just like the others, then why were his disciples the only ones who continued to believe in their Messiah’s cause? Aslan answers this question by claiming the disciples were reinvigorated by the resurrection, because Jesus’ “resurrection confirmed his status as messiah” (165).

The interesting thing about Aslan using the resurrection to support this claim is that he never references a resurrection story. Of course, that’s because all the resurrection stories undermine his claim that Jesus was a violent revolutionary. Aslan’s Jesus would be resurrected for the purpose of vengeance. But the resurrected Jesus has nothing to do with vengeance, but everything to do with peace. The resurrected Jesus speaks to Mary in a garden, enters a closed room full of the very disciples who abandoned him in his time of need, and talks with two disciples on the road to Emmaus. He never says, “Okay guys. This time I’ve got some serious powers. It’s time for vengeance!” Rather, he says, “Peace be with you.”

And then Jesus sent his disciples, as he sends us, into the world to offer that peace to everyone. It’s a peace that has nothing to do with violence, but everything to do with nonviolent love.

(For more on Aslan, click here to read my colleague Suzanne Ross’s reflection on his interview with Fox News.)

(Much of this article is influenced by Michael Hardin’s book The Jesus Driven Life: Reconnecting Humanity with Jesus and James Alison ’s adult education book and video series Jesus the Forgiving Victim: Listening to the Unheard Voice . )

- Uncategorized

- michael hardin

- mimetic theory

- nonviolence

- Library of World Religions

- Advertise With Us

- Write for Us

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

- Do Not Sell My Data

- Radiant Digital

- Manage Newsletter Subscriptions

- Unsubscribe From Notifications

The Way It Happened

- John’s Gospel

- River of Life

Book review: Zealot: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth

Posted on Monday, October 7, 2013 in Book Reviews | 0 comments

by Reza Aslan

Captivating! Reza is a good story teller who holds your attention on every topic. His perception of Jesus differs considerably from mine, but that’s part of what made the reading interesting for me.

Aslan portrays Jesus as a revolutionary predicting a violent overthrow of the current government, both Roman and Judean. Woe to the corrupt ruling class, because the Kingdom of God is coming, with chilling destruction! Aslan points out that in the political turmoil of the first century, calling oneself the Messiah was tantamount to declaring war on Rome, and thus he assumes Jesus followed the mold of every other Jewish messianic figure of the time. The apparent failure of this portrayal is that the Gospels take pains to highlight the daftness of the apostles and their dream for a military overthrow, repeatedly redefining the Kingdom of God instead as a peaceful grassroots infiltration. Aslan recognizes this, and insists that the tone of the Gospels reflect post-war attitudes of complacency and cooperation with Rome, after the nation’s zeal had been stamped out by defeat. “Thus began the long process of transforming Jesus from a revolutionary Jewish nationalist into a peaceful spiritual leader with no interest in any earthly matter.”

Indeed, this process is even longer than I imagined, for in Aslan’s opinion, it begins even before the Gospels. It begins back at the time of Stephen’s stoning. “What Stephen cries out in the midst of his death throes is nothing less than the launch of a wholly new religion … buried with [Stephen] under the rubble of stones is the last trace of the historical person known as Jesus of Nazareth.” Aslan believes Paul also taught that Jesus was God on earth, so the high Christology of today’s Christianity began quite early after Jesus’ death.

But let’s get back to Jesus the Revolutionary. Says Aslan, “Of all the stories told about the life of Jesus of Nazareth, there is one … that, more than any other word or deed, helps reveal who Jesus was and what Jesus meant.” So differently do Aslan and I view Jesus that I actually imagined he was thinking about Jesus feeding the multitude. He wasn’t, of course. He was talking about when Jesus violently attacks the Temple. Fascinating how different Jesus can look, depending upon which side of him you hold up to the light. Aslan’s book is one-sided, a very well-written page-turner about Jesus, the Zealot.

This is not to say that Jesus himself openly advocated violent actions. But he was certainly no pacifist. “Do not think that I have come to bring peace on earth. I have not come to bring peace, but the sword.”

When Jesus holds up a penny and says, “Render to Caesar the things that are Caesars, and to God the things that are God’s,” he is not encouraging an aesthetic life unhindered by the cares of the world. Says Aslan, Jesus’ answer is “as clear a statement as one can find in the gospels on where exactly he fell in the debate between the priests and the zealots.” Jesus says, give the coin with its abominable picture of Caesar back to Rome, and take back the land which God has given to us. This is not instruction to get along; this is instruction to draw a dividing line between heathen and God-follower; a line between Judea and Rome.

I believe Aslan contains a few errors in his research, but they are minor and do not distract from the conclusion. Of greater importance is recognizing where Aslan’s own strong opinions come into play. Yet this is a book I can wholeheartedly recommend, as both thought-provoking and entertaining.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

You may use these HTML tags and attributes: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>

Fantasy Football, Anyone?

The river of life, connect with me.

A Top-100 Christian Blog

Our top book picks.

Selected by The Dubious Disciple as Best Religion Books. Don't miss these!

Subscribers:

The god show, archives by month, archives by category.

About Leslie

More Interesting Links

- Canadian Center For Progressive Christianity

- Deep River Faith

- Jesus Is A Liberal

- Liberal Christian Network

- Religious Tolerance

- The Christian Humanist

- The Christian Left

- The Religion Nerd

- The Thirsty Theologian

For Authors & Publishers

Elegant Themes | Powered by Wordpress --> Copyright 2013 The Way It Happened | Owner: Lee Harmon, writing as The Dubious Disciple Blog maintenance and editing by Leslie Levi "John" artwork by Pat Marvenko Smith, copyright 1982 / 1992 - www.revelationillustrated.com.

- Subscriber Login

Since 1900, the Christian Century has published reporting, commentary, poetry, and essays on the role of faith in a pluralistic society.

© 2023 The Christian Century.

Contact Us Privacy Policy

Zealot , by Reza Aslan

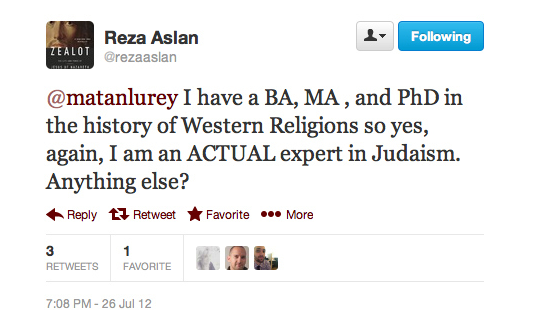

Reza Aslan’s Zealot arrived with an enormous splash. An engaging and personal interview on NPR’s Fresh Air attracted widespread interest. Then a Fox News interview commandeered Internet coverage. The network’s religion correspondent, Lauren Green, began by asking why Aslan, a Muslim, would write a book about Jesus. In his reply Aslan perhaps overstated his scholarly qualifications to write about the New Testament. The contentious interview was pure gold for Aslan and Random House: Zealot rocketed to Amazon’s no. one best-seller spot. Several accomplished biblical scholars quickly posted reviews of the book—something that rarely happens. At this point, any review must reckon with Zealot ’s remarkable marketing journey.

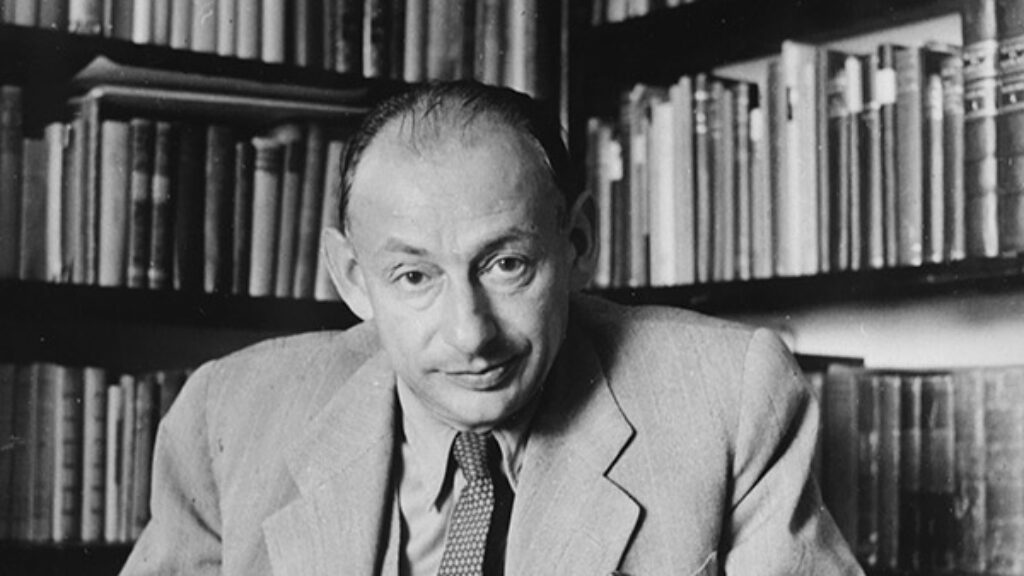

Aslan has established himself as an influential scholar and commentator on religion. His controversial No god but God: The Origins, Evolution, and Future of Islam is perhaps the most influential introduction to Islam for Western audiences. Aslan completed a master’s degree in theological studies at Harvard, then a Ph.D. in sociology at the University of California–Santa Barbara. His dissertation investigated global jihadism, a subject he took on in How to Win a Cosmic War: God, Globalization, and the End of the War on Terror . In short, Aslan is a public commentator on religion whose academic credentials are stronger in some areas than in others. New Testament studies represents one of his interests but not an area of formal expertise.

Aslan’s biography also invites interest: born a Muslim in Iran, he experienced an evangelical Christian conversion as an adolescent living in the United States. After an undergraduate encounter with critical biblical scholarship undermined his biblicist naïveté, Aslan abandoned Christianity and returned to embrace Islam—but with a difference. He identifies primarily with Sufism, Islam’s best-known expression of mysticism. Holding a critical distance from conventional dogma, Aslan welcomes truth from many religious traditions but chooses to identify primarily with Islam.

We would love to hear from you. Let us know what you think about this article by emailing our editors .

Most Recent

A refugee’s fragmented memory, april 28, easter 5b ( john 15:1–8; 1 john 4:7–21), psalm 23 in conversation (acts 4:5-12; psalm 23; 1 john 3:16-24; john 10:11-18).

by Austin Shelley

Centering Chloe and decentering Paul

Most popular.

Early Christianity, fragment by fragment

April 21, easter 4b ( psalm 23; john 10:11–18).

How might God bless a divided America?

The buddy-cop feminist detective series I didn’t know I needed

- Member Login

- Library Patron Login

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR

FREE NEWSLETTERS

Search: Title Author Article Search String:

Zealot : Book summary and reviews of Zealot by Reza Aslan

Summary | Reviews | More Information | More Books

The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth

by Reza Aslan

Critics' Opinion:

Readers' rating:

Published Jul 2013 336 pages Genre: History, Current Affairs and Religion Publication Information

Rate this book

About this book

Book summary.

From the internationally bestselling author of No god but God comes a fascinating, provocative, and meticulously researched biography that challenges long-held assumptions about the man we know as Jesus of Nazareth. Two thousand years ago, an itinerant Jewish preacher and miracle worker walked across the Galilee, gathering followers to establish what he called the "Kingdom of God." The revolutionary movement he launched was so threatening to the established order that he was captured, tortured, and executed as a state criminal. Within decades after his shameful death, his followers would call him God. Sifting through centuries of mythmaking, Reza Aslan sheds new light on one of history's most influential and enigmatic characters by examining Jesus through the lens of the tumultuous era in which he lived: first-century Palestine, an age awash in apocalyptic fervor. Scores of Jewish prophets, preachers, and would-be messiahs wandered through the Holy Land, bearing messages from God. This was the age of zealotry - a fervent nationalism that made resistance to the Roman occupation a sacred duty incumbent on all Jews. And few figures better exemplified this principle than the charismatic Galilean who defied both the imperial authorities and their allies in the Jewish religious hierarchy. Balancing the Jesus of the Gospels against the historical sources, Aslan describes a man full of conviction and passion, yet rife with contradiction; a man of peace who exhorted his followers to arm themselves with swords; an exorcist and faith healer who urged his disciples to keep his identity a secret; and ultimately the seditious "King of the Jews" whose promise of liberation from Rome went unfulfilled in his brief lifetime. Aslan explores the reasons why the early Christian church preferred to promulgate an image of Jesus as a peaceful spiritual teacher rather than a politically conscious revolutionary. And he grapples with the riddle of how Jesus understood himself, the mystery that is at the heart of all subsequent claims about his divinity. Zealot yields a fresh perspective on one of the greatest stories ever told even as it affirms the radical and transformative nature of Jesus of Nazareth's life and mission. The result is a thought-provoking, elegantly written biography with the pulse of a fast-paced novel: a singularly brilliant portrait of a man, a time, and the birth of a religion.

- "Beyond the Book" articles

- Free books to read and review (US only)

- Find books by time period, setting & theme

- Read-alike suggestions by book and author

- Book club discussions

- and much more!

- Just $45 for 12 months or $15 for 3 months.

- More about membership!

Media Reviews

Reader reviews.

"Starred Review. Why has Christianity taken hold and flourished? This book will give you the answers in the simplest, most straightforward, comprehensible manner." - Kirkus "Starred Review. Compulsively readable and written at a popular level, this superb work is highly recommended." - Publishers Weekly "A bold, powerfully argued revisioning of the most consequential life ever lived." - Lawrence Wright, Pulitzer Prize–winning author of Going Clear: Scientology, Hollywood, and the Prison of Belief "The story of Jesus of Nazareth is arguably the most influential narrative in human history. Here Reza Aslan writes vividly and insightfully about the life and meaning of the figure who has come to be seen by billions as the Christ of faith. This is a special and revealing work, one that believer and skeptic alike will find surprising, engaging, and original." - Jon Meacham, Pulitzer Prize–winning author of Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power "In Zealot , Reza Aslan doesn't just synthesize research and reimagine a lost world, though he does those things very well. He does for religious history what Bertolt Brecht did for playwriting. Aslan rips Jesus out of all the contexts we thought he belonged in and holds him forth as someone entirely new. This is Jesus as a passionate Jew, a violent revolutionary, a fanatical ideologue, an odd and scary and extraordinarily interesting man." - Judith Shulevitz, author of The Sabbath World

Author Information

Reza Aslan is an internationally acclaimed writer and scholar of religions. His first book, No god but God: The Origins, Evolution, and Future of Islam, has been translated into thirteen languages and named by Blackwell as one of the hundred most important books of the last decade. He is also the author of How to Win a Cosmic War: God, Globalization, and the End of the War on Terror (published in paperback as Beyond Fundamentalism ), as well as the editor of Tablet & Pen: Literary Landscapes from the Modern Middle East . Born in Iran, he lives in New York and Los Angeles with his wife and two sons.

More Author Information

More Recommendations

Readers also browsed . . ..

- Poverty, by America by Matthew Desmond

- Valiant Women by Lena S. Andrews

- Flee North by Scott Shane

- The Wide Wide Sea by Hampton Sides

- The Country of the Blind by Andrew Leland

- The Wager by David Grann

- Impossible Escape by Steve Sheinkin

- All You Have to Do Is Call by Kerri Maher

- High Bias by Marc Masters

- Around the World in Eighty Games by Marcus du Sautoy

more history, current affairs and religion...

Support BookBrowse

Join our inner reading circle, go ad-free and get way more!

Find out more

BookBrowse Book Club

Members Recommend

The Flower Sisters by Michelle Collins Anderson

From the new Fannie Flagg of the Ozarks, a richly-woven story of family, forgiveness, and reinvention.

The House on Biscayne Bay by Chanel Cleeton

As death stalks a gothic mansion in Miami, the lives of two women intertwine as the past and present collide.

Win This Book

The Funeral Cryer by Wenyan Lu

Debut novelist Wenyan Lu brings us this witty yet profound story about one woman's midlife reawakening in contemporary rural China.

Solve this clue:

and be entered to win..

Your guide to exceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.

Subscribe to receive some of our best reviews, "beyond the book" articles, book club info and giveaways by email.

Plot Summary? We’re just getting started.

Add this title to our requested Study Guides list!

Nonfiction | Biography | Adult | Published in 2013

Plot Summary

Continue your reading experience

SuperSummary Plot Summaries provide a quick, full synopsis of a text. But SuperSummary Study Guides — available only to subscribers — provide so much more!

Join now to access our Study Guides library, which offers chapter-by-chapter summaries and comprehensive analysis on more than 5,000 literary works from novels to nonfiction to poetry.

See for yourself. Check out our sample guides:

Toni Morrison

Malcolm Gladwell

David And Goliath

D. H. Lawrence

Whales Weep Not!

Related summaries: by Reza Aslan

A SuperSummary Plot Summary provides a quick, full synopsis of a text.

A SuperSummary Study Guide — a modern alternative to Sparknotes & CliffsNotes — provides so much more, including chapter-by-chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and important quotes.

See the difference for yourself. Check out this sample Study Guide:

Advertisement

Supported by

John Brown and Abraham Lincoln: A Study in Contrasts

- Share full article

- Apple Books

- Barnes and Noble

- Books-A-Million

When you purchase an independently reviewed book through our site, we earn an affiliate commission.

By Sean Wilentz

- Published Oct. 6, 2020 Updated Dec. 3, 2020

THE ZEALOT AND THE EMANCIPATOR John Brown, Abraham Lincoln, and the Struggle for American Freedom By H. W. Brands

Late in 1859, news of John Brown’s failed raid on the federal armory at Harpers Ferry alarmed Abraham Lincoln, and his dismay worsened when prominent Northerners celebrated Brown as a saint. For five years, Lincoln had been working to build an antislavery political coalition across the North that would finally break the Southern slaveholders’ domination of the government. Fending off absolutists who proclaimed a moral law higher than the Constitution, battling Northern racists who hurled slurs unprintable today, Lincoln and the fledgling Republican Party would put slavery on what Lincoln called “the course of ultimate extinction.” After decades in the political wilderness, slavery’s opponents were at last seriously contending for national power.

Suddenly, on the eve of a crucial presidential election year, Brown’s attempted insurrection, doomed from the start (as Frederick Douglass told Brown when he refused to join it), endangered everything. Instantly, a national chorus from Stephen A. Douglas to Jefferson Davis blamed the incident on the party they vilified as the “Black Republicans,” now disgraced as lawless traitors. Worse for Republicans, some prominent high-minded Northerners exalted Brown’s crime as a sublime act by a Christlike hero who transcended petty party politics. Ralph Waldo Emerson declared that Brown’s blood sacrifice would “make the gallows as glorious as the cross.” In some New England towns, church bells pealed at the hour of Brown’s execution.

The next day, Lincoln, on the verge of commencing to run for president, drew a distinction that was escaping some of his panicky fellow Republicans. “Old John Brown has just been executed for treason,” Lincoln wrote, and though he granted that Brown was perfectly right about slavery, he repudiated Brown’s undertaking. Brown’s antislavery convictions hardly made him a Republican; neither could they justify a desperate, even suicidal effort to instigate a violent rebellion. Nor could Brown’s strange mystique hide the damage his exploits had done to the growing antislavery cause. “It could avail him nothing that he might think himself right,” Lincoln concluded. At a time of inexorable polarization, Lincoln permitted neither racist smears nor radical pieties to deflect his own antislavery purpose.

[ Read an excerpt from “The Zealot and the Emancipator.” ]

H. W. Brands ’s study of Brown and Lincoln, which features this dramatic moment, is at heart an appraisal of contrasting political designs and personas in prerevolutionary times. A distinguished professor of American history at the University of Texas, Brands is a hyperprolific scholar, the author of more than two dozen books on subjects ranging from the life of Benjamin Franklin to Lyndon B. Johnson’s foreign policy. “The Zealot and the Emancipator,” describing Brown’s and Lincoln’s development in alternating chapters, builds on strengths long evident in Brands’s books, combining expert storytelling with thoughtful interpretation vividly to render major events through the lives of the chief participants. Apart from a biography of U. S. Grant, Brands has until now had surprisingly little to say about the Civil War era, but this book presents a gripping account of the politics that led to Southern secession, war and the abolition of slavery.

[ This book was one of our most anticipated titles of October. See the full list . ]

By calling John Brown a “zealot,” Brands appears to mean a fanatic in a righteous cause. An ironclad patriarch of Puritan rectitude — his admirers likened him to Oliver Cromwell — Brown, when in his mid-30s, consecrated his life to destroying the institution of slavery. As it was founded in wicked violence, he believed, so holy violence, including terrorist atrocities when called for, would weaken it, all leading to a final reckoning when oppressed Black people and their white allies would vanquish the Pharisee slaveholders. Brown regarded all conventional politics, including antislavery politics practiced by the likes of Abraham Lincoln, as a sham, as dangerous to the cause of liberty as the power of the slaveholders. The escalating supremacy of the slave South and its racist abettors in the 1850s, culminating in the Supreme Court’s infamous Dred Scott decision in 1857, hardened Brown’s contempt, and it propelled his attack on Harpers Ferry.

Brands offers a detailed, almost minute-by-minute account of Brown’s raid, which he rates a “wretched fiasco,” a “quixotic venture” that, far from unshackling the enslaved, tightened their shackles even further. Brands affirms the justice behind Brown’s actions, no matter how zealous, when measured against the cruelty of slavery. He describes how Brown’s self-dramatizing performance during his trial turned him into the inspiring popular martyr whose soul would mythically go marching on. But Brown’s story ends roughly two-thirds of the way through Brands’s book. The denouement — and the achievement of slavery’s destruction — belonged to Abraham Lincoln.

In calling Lincoln “the emancipator,” Brands takes exception to a view of Lincoln, now in vogue in some quarters, as a reluctant freedom fighter, a moderate politician who was devoted only to preserving the Union until the vagaries of the Civil War forced his hand. In fact, Lincoln’s hatred of slavery, established early in his life, ran deep: Brands quotes one Illinois abolitionist who got to know him in the 1840s and found “his view and mine on the wrong of slavery … in perfect accord.” As a working politician, Lincoln heeded practical limits, but he did not conceal his antislavery convictions: During his single term in Congress, from 1847 to 1849, he gravitated to antislavery colleagues, withstood abuse for opposing the American war against Mexico as pro-slavery and introduced legislation to eradicate slavery in the District of Columbia, a longtime abolitionist goal. Lincoln’s emergence as an antislavery leader in the 1850s had a long foreground.

In line with recent writings by, among others, James Oakes and Sidney Blumenthal , Brands refuses to diminish Lincoln’s antislavery moral commitment because of his politics, any more than he absolves Brown’s uncompromising higher judgments of their untethered recklessness. He quotes Frederick Douglass, who knew both men and who said in retrospect that while abolitionist agitators (including Douglass himself) might have dismissed Lincoln before the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation as cold and indifferent, in fact, given the difficulties he faced, “he was swift, zealous, radical and determined.”

At the heart of everything was Lincoln’s understanding of the Constitution: Whereas his radical critics cared little or nothing about man-made laws or believed, much as the pro-slavery secessionists did, that the framers had enshrined human bondage in national law, Lincoln saw great antislavery potential in the Constitution. In that sense, his reverence for the Union and his hatred of slavery went hand in hand. When, in 1860-61, Southern states seceded rather than accede to his election as president, Lincoln resolved to crush the rebellion. Doing so, perforce, would also crush the rebels’ claim that the national government was powerless to halt slavery’s growth and commence its extinction. At the outset, it seemed, nothing could begin on slavery unless and until the Union was saved. Yet as the war raged, it became apparent that preserving the Union required a proclamation of emancipation, a goal that, as Brands’s final chapters show, Lincoln pursued with constitutional correctness and immense political skill.

John Brown despised politicians and political parties. His disastrous raid paradoxically contributed to the nomination of Lincoln, the fresh national face from Illinois, unlike Senator William Seward of New York, who carried decades of political baggage, and was tarred, not least, for having known of Brown. This may have been Brown’s greatest feat for the antislavery cause and his most important contribution to American history. Only the sort of consummate politician Brown hated could have achieved the abolition of slavery.

Sean Wilentz teaches at Princeton and is the author of “No Property in Man: Slavery and Antislavery at the Nation’s Founding.” His edition for the Library of America of the historian Richard Hofstadter’s writings, the first of a projected three volumes, appeared earlier this year.

THE ZEALOT AND THE EMANCIPATOR John Brown, Abraham Lincoln, and the Struggle for American Freedom By H.W. Brands 464 pp. Doubleday. $30.

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

Salman Rushdie’s new memoir, “Knife,” addresses the attack that maimed him in 2022, and pays tribute to his wife who saw him through .

Recent books by Allen Bratton, Daniel Lefferts and Garrard Conley depict gay Christian characters not usually seen in queer literature.

What can fiction tell us about the apocalypse? The writer Ayana Mathis finds unexpected hope in novels of crisis by Ling Ma, Jenny Offill and Jesmyn Ward .

At 28, the poet Tayi Tibble has been hailed as the funny, fresh and immensely skilled voice of a generation in Māori writing .

Amid a surge in book bans, the most challenged books in the United States in 2023 continued to focus on the experiences of L.G.B.T.Q. people or explore themes of race.

Each week, top authors and critics join the Book Review’s podcast to talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

What Jesus Wasn’t: Zealot

- By Allan Nadler

- August 11, 2013

ithin an hour of its online debut, the number of viewers of Reza Aslan’s now notorious interview with Fox News’ Lauren Green had far exceeded the number of Israelites who crossed the Red Sea under the leadership of the father of all Jewish nationalist zealots, Moses. Aslan was being interviewed on the occasion of the appearance of his book that places Jesus of Nazareth at the top of a long list of subsequent, rabidly nationalist messianic Jewish zealots.

By now, Aslan’s Zealot: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth has come to dominate every book sales index in America, and his fifteen Fox-minutes of fame have been viewed by millions. Sales for this “scholarly” book have broken every record in the category of religious studies; the number of stops on Aslan’s current speaking tour is nothing short of staggering; and it will surely require a crack team of number-crunching accountants to calculate the tax debt on Aslan’s royalties and speaking fees.

Given such overwhelming statistics, it is perhaps understandable that Aslan himself appears to be experiencing some problems keeping his numbers, and his facts, straight. That he is numerically challenged was apparent during the Fox interview. No sooner had Green posed the first of her series of preposterous questions, all pondering what might motivate, or justify, a Muslim to publish such a provocative book about her Lord and Savior, than Aslan, with rapid-fire confidence, listed his many alleged scholarly credentials, as a “scholar of religions with four degrees, including one in the New Testament, and a PhD in the History of Religions . . . who has been studying the origins of Christianity for two decades.” He then went on to claim that he was a professor of religious history; that he had been working assiduously on his Jesus book for twenty years; that it contains more than “one hundred pages of endnotes”; and, finally, that Zealot is the fruit of research based on his “study of around 1,000 scholarly books.”

That last greatly exaggerated claim is as good, or awkward, a place as any to begin an assessment of the credibility of the man and his work. Zealot does indeed provide a respectable, if spotty, bibliography. But it lists one hundred and fifty four, not one thousand, books. Given his evident talent at self-promotion , it is hard to imagine that Aslan was holding back out of an abundance of humility. His claim regarding his extensive endnotes is also plainly false, since there is not a single footnote or conventional endnote to be found anywhere in Zealot. The book’s chapters are, rather, appended by bibliographic essays, loosely related to their respective general themes. A cursory review of Aslan’s own biography and bibliography also renders impossible his repeated claims that Zealot is the product of twenty years of “assiduous scholarly research about the origins of Christianity.”

To be sure, Aslan, 41, has been very hard at work since graduating college with a dazzling array of projects—mostly having to do with Islamic religion, culture, and literature as well as Middle Eastern politics—but none of which has anything to do with his quest for the historical Jesus. He is, to quote his own website, “the founder of AslanMedia.com, an online journal for news and entertainment about the Middle East and the world, and co-founder and Chief Creative Officer of BoomGen Studios, the premier entertainment brand for creative content from and about the Greater Middle East,” including comic books. Of his three graduate degrees, one is from the University of Iowa where he studied creative writing (the subject he actually teaches at the University of California, Riverside); the second was a two-year masters degree at the Harvard Divinity School, where he apparently concentrated on Islam; and his doctorate was not, as he indignantly told the hapless Green, in “the history of religions.” Rather, he wrote an exceedingly brief sociological study of “ Global Jihadism as a Transnational Movement ,” at UC Santa Barbara.

Speaking on CNN in the wake of his Fox interview, Aslan ruefully observed, “There’s nothing more embarrassing than an academic having to trot out his credentials. I mean, you really come off as a jerk.” Actually, there is something significantly more embarrassing, and that is when the academic trots out a long list of exaggerated claims and inflated credentials.

Perhaps it is Aslan’s general fondness for breathless, and often reckless, exaggeration that explains his problems with the basic digits and facts about his own work and life. Such hyperbole alas pervades Zealot . Depicting the religious mood of first-century Palestine early on in the book, Aslan asserts that there were “countless messianic pretenders” among the Jews (there were no more than an eminently countable half-dozen). Among his most glaring overestimations is Aslan’s problematic insistence that the foundational Christian belief about Jesus, namely that he was both human and divine, is “anathema to five thousand years of Jewish scripture, thought and theology.” The vast chronological amplification aside, Judaism’s doctrine about this matter is not nearly so simple, as Peter Schäfer demonstrated exhaustively in his very important study, The Jewish Jesus, and which Daniel Boyarin has argued even more forcefully in his latest book, The Jewish Gospels. Boyarin and Schäfer are just two of the many serious scholars whose works Aslan has clearly failed to consult.

This combination of overly confident and simplistic assertions on exceedingly complex theological matters, with stretching of truths—numerical, historical, theological, and personal—permeates Aslan’s bestseller. And yet, precisely because Zealot is generating such frenzied controversy, this is all serving Aslan very well. But as it would be wrong to judge Aslan’s book by its coverage, let us turn to its text.

Aslan’s entire book is, as it turns out, an ambitious and single-minded polemical counter-narrative to what he imagines is the New Testament’s portrayal of Jesus Christ.

The core thesis of Zealot is that the “real” Jesus of Nazareth was an illiterate peasant from the Galilee who zealously, indeed monomaniacally, aspired to depose the Roman governor of Palestine and become the King of Israel. Aslan’s essentially political portrayal of Jesus thus hardly, if at all, resembles the depiction of the spiritual giant, indeed God incarnate, found in the Gospels and the letters of Paul. While Aslan spills much ink arguing his thesis, nothing he has to say is at all new or original. The scholarly quest for the historical Jesus, or the “Jewish Jesus,” has been engaged by hundreds of academics for the past quarter millennium and has produced a mountain of books and a vast body of serious scholarly debate. The only novelty in Aslan’s book is his relentlessly reductionist, simplistic, one-sided and often harshly polemical portrayal of Jesus as a radical, zealously nationalistic, and purely political figure. Anything beyond this that is reported by his apostles is, according to Aslan, Christological mythology, not history.

Aslan is, to be sure, a gifted writer. The book’s Prologue is both titillating and bizarre. Entitled “A Different Sort of Sacrifice” it opens with a breezy depiction of the rites of the Jerusalem Temple, but very quickly descends to its ominously dark denouement: the assassination of the High Priest, Jonathan ben Ananus, on the Day of Atonement, 56 C.E., more than two decades after Jesus’s death:

The assassin elbows through the crowd, pushing close enough to Jonathan to reach out an invisible hand, to grasp the sacred vestments, to pull him away from the Temple guards and hold him in place just for an instant, long enough to unsheathe a short dagger and slide it across his throat. A different sort of sacrifice.

There follows a vivid narration of the political tumult that had gripped Roman-occupied Palestine during the mid-first century, which Aslan employs to great effect in introducing readers to the bands of Jewish zealots who wreaked terror and havoc throughout Judea for almost a century. It seems like an odd way to open a book about the historical Jesus, who was crucified long before the Zealot party ever came into existence, until one catches on to what Aslan is attempting. The Prologue effectively associates Jesus, albeit as precursor, with that chillingly bloody murder by one of the many anonymous Jewish Zealots of first-century Palestine.

To address the obvious problem that the Jesus depicted in Christian Scriptures is the antithesis of a zealously political, let alone ignorant and illiterate, peasant rebel and bandit, Aslan deploys a rich arsenal of insults to dismiss any New Testament narrative that runs counter to his image of Jesus as a guerilla leader, who gathered and led a “corps” of fellow “bandits” through the back roads of the Galilee on their way to mount a surprise insurrection against Rome and its Priestly lackeys in Jerusalem. Any Gospel verse that might complicate, let alone undermine, Aslan’s amazing account, he insolently dismisses as “ridiculous,” “absurd,” “preposterous,” “fanciful,” “fictional,” “fabulous concoction,” or just “patently impossible.”

Aslan’s entire book is, as it turns out, an ambitious and single-minded polemical counter-narrative to what he imagines is the New Testament’s portrayal of Jesus Christ. The strawman Jesus against whom he is arguing, however, is a purely heavenly creature, far closer to the solely and absolutely unearthly Christ of the 2 nd -century heretic Marcion, than the exceedingly complex man/God depicted by the Evangelists and painstakingly developed in the theological works of the early Church Fathers.

Aslan dismisses just about all of the New Testament’s accounts of the early life and teachings of Jesus prior to his “storming” of Jerusalem and his subsequent arrest and crucifixion. He goes so far as to insist that Jesus’s zealous assault on the Jerusalem Temple is the “singular fact that should color everything we read in the Gospels about the Messiah known as Jesus of Nazareth.” Everything! Aslan goes on to assert that the very fact of his crucifixion for the crime of sedition against the Roman state is “all one has to know about the historical Jesus.” Still, as the New Testament constitutes the principal primary source for these facts as well as for anything else we can know about the “life and times of Jesus,”Aslan has little choice but to rely rather heavily on certain, carefully selected New Testament narratives.

Aslan is insistently oblivious even of the powerfully resonant climax to the single act of violence on the part of any of the twelve apostles recorded in the Gospels.

The persistent problem permeating Aslan’s narrative is that he never provides his readers with so much as a hint of any method for separating fact from fiction in the Gospels, a challenge that has engaged actual scholars of the New Testament for the last two centuries. Nowhere does he explain, given his overall distrust of the Gospels as contrived at best and deliberately fictitious at worst, why he trusts anything at all recorded in the New Testament. But one needn’t struggle too hard to discern Aslan’s selection process: Whichever verses fit the central argument of his book, he accepts as historically valid. Everything else is summarily dismissed as apologetic theological rubbish of absolutely no historical worth.

So, for example, after recounting the Romans’ declaration of Jesus’s guilt, he writes:

As with every criminal who hangs on a cross, Jesus is given a plaque, or titulus , detailing the crime for which he is being crucified. Jesus’s titulus reads KING OF THE JEWS. His crime: striving for kingly rule, sedition. And so, like every bandit and revolutionary, every rabble-rousing zealot and apocalyptic prophet who came before or after him— like Hezekiah and Judas, Theudas and Athronges, the Egyptian [sic] and the Samaritan [sic], Simon son of Giora and Simon son of Kochba, Jesus is executed for daring to claim the mantle of king and messiah.

(Lest the words of the titulus be mistaken for mockery, Aslan informs us that the Romans had no sense of humor, which will come as a surprise to classicists.)

Aslan is particularly fond of assembling such lists of Jesus’s seditious predecessors, peers, and successors. Elsewhere, he compares Jesus’s mission to Elijah’s, which ended in his slaughter of the four hundred and fifty prophets of Baal; on another occasion he sets Jesus alongside Judas Maccabeus, who waged a long and bloody war against the Greek Seleucids. And Jesus is made out to be a direct forerunner of the militant rebel of the second century, Simon bar Kokhba, who battled the Romans to the goriest of ends. And so on.

The crucial distinction that Aslan fails to acknowledge is that what clearly sets Jesus so radically apart from all of these figures is his adamant rejection of violence, to say nothing of the pervasively peaceful and loving content of his teachings and parables, which Aslan willfully misconstrues and at one point revealingly describes as so “abstruse and enigmatic” as to be “nearly impossible to understand.”

Aslan is insistently oblivious even of the powerfully resonant climax to the single act of violence on the part of any of the twelve apostles recorded in the Gospels, which occurred during the tumult surrounding Jesus’s arrest by the minions of the Jewish High Priest, Caiaphas:

While he was still speaking, suddenly a crowd came, and the one called Judas, one of the twelve, was leading them. He approached Jesus to kiss him; but Jesus said to him, “Judas, is it with a kiss that you are betraying the Son of Man?” When those who were around him saw what was coming, they asked, “Lord, should we strike with the sword?” Then one of them struck the slave of the high priest and cut off his right ear. But Jesus said, “No more of this!” And he touched his ear and healed him. (Luke 22:47-51)

Matthew’s version of the same episode ends with Jesus’s stern and powerful admonition against any sort of violence:

Suddenly, one of those with Jesus put his hand on his sword, drew it, and struck the slave of the high priest, cutting off his ear. Then Jesus said to him, “Put your sword back into its place; for all who take the sword will perish by the sword.” (Matthew 26:51-52)

And in Mark’s version of the story, Jesus protests his peaceful intentions to those who come to seize him violently, crying out “Have you come out with swords and clubs to arrest me as though I were a bandit?” (Mark 14:48).

Unsurprisingly, Aslan dismisses these passages as pure invention. One problem with this is that Aslan sometimes justifies his own selective acceptance of certain New Testament narratives by pointing to their appearance in all three of the synoptic Gospels which, he argues, lends them a degree of historical credibility.

Another problem is that one of the key texts that Aslan uses to buttress his thesis that the proto-Zealot Jesus was planning for some kind of apocalyptic showdown with his enemies, is taken from the very same chapter in Luke:

He said to them, “But now, the one who has a purse must take it, and likewise a bag. And the one who has no sword must sell his cloak and buy one.” . . . They said, “Lord, look, here are two swords.” He replied, “It is enough.” (Luke 22:36, 38)

The Jesus actually depicted here is hardly prepping his “band of zealots” for a rebellion against Roman rule by strictly limiting their arsenal to two, obviously symbolic, swords.

Why would the Evangelists deliberately engage in so much wanton fabrication? Aslan offers a simple explanation:

With the Temple in ruins and the Jewish religion made pariah, the Jews who followed Jesus as messiah had an easy decision to make: they could either maintain their cultic connection to their parent religion and thus share in [sic] Rome’s enmity, or they could divorce themselves from Judaism and transform their messiah from a fierce Jewish nationalist into a pacifistic preacher of good works whose kingdom was not of this world.

Allergic to ambiguities or complexities of any kind that might interfere with his Manichean dichotomy between the historical Jesus of Nazareth and mythical Jesus Christ of the Gospels, Aslan perceives everything as an either/or proposition—either the zealous, radical, and purely political Jesus of history, or the entirely fictional moral teacher and pacifistic Jesus of Christology. He takes the same approach to the Jews of Jesus’s era: There existed either the violent apocalyptic Jewish bandits who mounted one rebellion after another against the Romans, or the corrupt quisling Priests, such as Caiaphas who suppressed all such activity. The passive, scholarly Pharisees who opposed both these postures, are simply ignored.

The only passage I could find in Aslan’s entire book where he argues for a more nuanced approach to anything pertains to Jesus’s “views on the use of violence,” which he insists have been widely misunderstood:

To be clear, Jesus was not a member of the zealot party that launched the war with Rome because no such party could be said to exist for another thirty years after his death. Nor was Jesus a violent revolutionary bent on armed rebellion, though his views on violence were far more complex than it is often assumed.

And yet, elsewhere Aslan insists, that being “no fool,” Jesus “understood what every other claimant to the mantle of messiah understood: God’s sovereignty could not be established except through force.” And it is this latter characterization which is central to Zealot .

To take account of the fact that even at the moment of Jesus’s maximal zeal, when he stormed the Temple, he was also interpreting Hebrew Scriptures would seriously undermine Aslan’s insistence on Jesus’s illiteracy, so he ignores it. The same goes for the numerous times he is addressed, both by his disciples as well as by the Pharisees and the Romans, as “teacher” and “rabbi.”

There is not so much as an allusion to be found in Zealot to the fascinating debates between Jesus and the Pharisees about the specifics of Jewish law, such as the permissibility of divorce, the proper observance of the Sabbath, the requirement to wash one’s hands before eating, the dietary laws, and—most fascinating and repercussive of all—the correct understanding of the concept of resurrection, in response to a challenge by the Sadducees who rejected that doctrine tout-court.

Aslan is intent on portraying Jesus as a faithful, Torah-abiding Jew for obvious reasons: Intent on being crowned King of Israel, and as such a candidate for the highest Jewish political office, how could he be anything less than a “Torah-true” Jew? So Aslan takes at face value the Gospel’s report (Matthew 5:7) of Jesus’s insistence that he has not come to undermine a single law of the Torah, but rather to affirm its every ordinance.

Aslan’s ignorance—if that is what it is—has serious consequences.

In this connection , alas, Aslan offers a most unflattering and skewed stereotype of Jesus as a typical Jew of his era, namely an intolerant ethnocentric nationalist prone to violence towards Gentiles and whose charity and love extend only to other Jews:

When it comes to the heart and soul of the Jewish faith—the Law of Moses—Jesus insisted that his mission was not to abolish the law but to fulfill it (Matthew 5:17). That law made a clear distinction between relations among Jews and between Jews and foreigners. The oft-repeated [sic] commandment to “love your neighbor as yourself” was originally given strictly in the context of internal relations within Israel . . . To the Israelites, as well as to Jesus’s community in first-century Palestine, “neighbor” meant one’s fellow Jews. With regard to the treatment of foreigners and outsiders, oppressors and occupiers, the Torah could not be clearer: “You shall drive them out before you. You shall make no covenant with them and their gods. They shall not live in your land ” (Exodus, 23:31-33)

As in his highly selective misuse of the Gospels, Aslan is here distorting the Hebrew Scriptures, conflating different categories of “foreigners,” and erasing the crucial distinction between the righteous ger, or foreigner, and the pernicious idolator, as well as the radically different treatments the Torah commands towards each. He mischievously omits the Torah’s many and insistent prohibitions against “taunting the stranger, for you know the soul of the stranger having been strangers in the land of Egypt,” and “cheating the foreigner in your gate”, and, most powerfully, the injunction to “love the stranger as yourself.” (See, inter alia, Exodus 22:20 & 23:9, Leviticus 19:34 and Deuteronomy 24:14.)

Aslan achieves the two central goals of his book with this distorted, and terribly unflattering, depiction of the treatment he alleges Jewish law demands of the foreigner. It at once hardens his argument about Jesus’s “fierce nationalism,” while at the same time creating an image of the Jews as a hateful bunch, profoundly intolerant of the mere presence of others in their land. It is difficult when reading this, and many similar blatant distortions, to suppress all suspicion of a political agenda lying just beneath the surface of Aslan’s narrative.

What will prove most shocking, at least to those with some very basic Jewish education, are Aslan’s many distorted, or plainly ignorant, portrayals of both the Jews and their religion in Jesus’s day. Aside from his apparent unfamiliarity with the critically important recent works of Schäfer and Boyarin, Aslan seems oblivious of more than a century of scholarship on the exceedingly complex theological relationship between the earliest disciples of Jesus and the early rabbis. The foundational work of R. Travers Herford in Christianity in Talmud and Midrash (1903) and, three-quarters of a century later, Alan Segal’s Two Powers in Heaven: Early Rabbinic Reports about Christianity and Gnosticism (1977) are just two of the hundreds of vitally important books missing from his bibliography.

This ignorance—if that is what it is—has serious consequences. For it is not only the Gospels’ accounts of Jesus citing Hebrew Scriptures while discussing Jewish law that belie Aslan’s portrait of Jesus and his apostles as an uncouth band of Galilean peasants. As Schäfer has richly documented, Rabbinic sources contain numerous references to the original biblical exegesis of Jesus and his disciples, including accounts of rabbis who were attracted to these interpretations, even as they came ultimately to regret and repent of their “heresy.” That Aslan has not read Schäfer is made most painfully clear in his pat dismissal of the Roman historian Celsus’s report of having overheard a Jew declare that Jesus’s real father was not the Jew, Joseph, but rather a Roman centurion named Panthera. Aslan says that this is too scurrilous to be taken seriously. While it would be unfair to expect him to be familiar with the common Yiddish designation of Jesus as Yoshke-Pandre (Yeshua, son of Panthera), one might expect him to have read the fascinating chapter devoted to this very familiar and well-attested theme in rabbinic sources, in Schäfer’s Jesus in the Talmud.

On the other hand, Aslan weirdly accepts at face value, and even embellishes, the dramatic accounts in the Gospels of Jesus’s entry into Jerusalem allegedly just before the Passover, as the Jewish crowds wave palm branches and chant hosannas. But were he familiar with the basic rituals of the Sukkot festival, Aslan might somewhere have acknowledged the skepticism expressed by many scholars about the Gospels’ contrived timing of this dramatic event to coincide with Passover.

I will spare readers a long list of Aslan’s blatant and egregious errors regarding Judaism, from his misunderstanding of the rabbinic epithet Am Ha-Aretz (the rabbinic description, fittingly enough, of an ignoramus) to his truly shocking assertion that rabbinic sources attest to Judaism’s practice of crucifixion. Aslan very effectively explains why the Romans employed crucifixion to such great effect; the horrific public spectacle of the corpses of those condemned for their sedition to this most agonizing of deaths was a powerful deterrent to would-be insurrectionists. However, he seems not to understand how particularly offensive this was to the Jews, whose Torah demanded the immediate burial of executed criminals (who were to be hanged, never crucified), prohibiting their corpses to linger “even unto the morning” as this was considered a desecration of the divine image in which all men were created.

Finally, there is Aslan’s description of the fate of the Jews and Judaism in the wake of the destruction of the Temple. In his account, all of the Jews were exiled from Judea, and not so much of a trace of Judaism was allowed to survive in the Holy Land after 70 C.E.. Astonishingly enough, Aslan says not a word about the tremendously important armistice arranged between the pacifistic party of Jewish moderates led by Yochanan ben Zakai, or of the academy he established at Yavneh (Jabne, or Jamnia) some forty miles northwest of Jerusalem, and which flourished for more than a half-century, breathing new life and vitality into rabbinic Judaism in the immediate aftermath of the destruction of Jerusalem.

Readers with no background in the history of rabbinic Judaism will be misled by Aslan to believe that its pacification was the result of the Jews total defeat and expulsion from Palestine. Aslan seems to think that rabbinic Judaism is entirely a product of diaspora Jews who, only many decades after the Temple’s destruction, began to develop a less virulently and racist version of the Jewish religion, centered on Torah study. Can it be that this self-professed “historian of religions” is entirely ignorant of the Sages of the Land of Israel who flourished in the wake of the destruction of the Temple, and whose teachings are recorded in the Mishnah, and later the Jerusalem Talmud? Or is Aslan, here again, choosing deliberately to ignore inconvenient historical truths? And none is less convenient than the fact that a significant, and ultimately dominant, faction of Jews of first-century Palestine, far from being nationalist zealots, were pacifists whose accord with Vespasian gave birth to the religion we today recognize as Judaism.

Which brings us back to Aslan’s awful interview on Fox. Lauren Green’s questioning of Aslan’s right, as a Muslim, to write his book was absolutely out of bounds, but perhaps she was, quite unwittingly, onto something about his agenda. While the form taken by Green’s questions was unacceptable and made Aslan look like the victim of an intolerant right-wing ambush, might it not be the case that it was Aslan who very deftly set her up? He prefaces the book with an “Author’s Note,” which is a lengthy and deeply personal confession of faith. Here Aslan recounts his early years in America as an essentially secular Iranian emigré of Islamic origins with no serious attachment to his ancestral faith, his subsequent teenage conversion to evangelical Christianity and finally his return to a more intense commitment to Islam. Aslan ends this intimately personal preface by proudly declaring:

Today, I can confidently say that two decades of rigorous academic research into the origins of Christianity have made me a more genuinely committed disciple of Jesus of Nazareth than I ever was of Jesus Christ.

This unsubtle suggestion that Evangelical Christians’ discipleship and knowledge of Jesus is inferior to his own makes it rather harder to sympathize with him as an entirely innocent victim of unprovoked, ad hominem challenges regarding his book’s possibly Islamist agenda. Aslan had to know that opening a book that portrays Jesus as an illiterate zealot and which repeatedly demeans the Gospels with a spiritual autobiography that concludes by belittling his earlier faith as an Evangelical Christian would prove deeply insulting to believing Christians.

And yet, if there is one thing Aslan must have learned during his years among the Evangelicals, it is that even the most rapturous among them, who pray fervently for the final apocalypse, reject even the suggestion that their messianic dream ought to be pursued through insurrection or war. In a word, they have, pace Aslan, responded appropriately to the question “what would Jesus do?”

Finally, is Aslan’s insistence on the essential “Jewishness” of both Jesus and his zealous political program not also a way of suggesting that Judaism and Jesus, no less than Islam and Mohammed, are religions and prophets that share a similarly sordid history of political violence; that the messianic peasant-zealot from Nazareth was a man no more literate and no less violent than the prophet Mohammed?

Excellent piece. I would only add that the author unfortunately reinforces Aslan's error of referring to "first-century Palestine." The Romans (later, Byzantines) did not refer to the area as Syria Palestina until well after the time of Jesus.

I am an academic but certainly not a scholar of religious studies by any stretch. Having strayed from my Roman Catholic roots, I am slowly working my way back to renew my relationship. Books by Aslan and others and reviews such as provided by Dr. Nadler certainly have given me a variety of views to consider. I would have found extremely helpful in Dr. Nadler's criticism some additional details about some of Aslan's comments: "Any Gospel verse that might complicate, let alone undermine, Aslan’s amazing account, he insolently dismisses as “ridiculous,” “absurd,” “preposterous,” “fanciful,” “fictional,” “fabulous concoction,” or just “patently impossible.” How specifically were these descriptors off target?

Paul Bettinger "Live Free or Die"

Whatever Aslan's faults, and I am sure they are many whereas he is hardly original, Nadler too has much fact-checking to do. Imagine this mistake on his part: "the historical Jesus, who was crucified long before the Zealot party ever came into existence" If so, then why is one of Jesus' followers called Simon the Zealot? [Matt. 10:4].

Elliott A Green

PaulDouglasHughes

"In a media-addled age, mere scrupulous scholarship is rarely a match for shameless intellectual dishonesty or emotional derangement." David Bentley Hart

In response to eil100's query, which indeed "imagines" my "mistake": It doesn't require "much fact-checking" (in fact in requires almost none at all) to know that the Zealot (upper-case) party, namely the adherents of what Josephus termed the "Fourth Philosophy" emerged in the context of the Jewish rebellion against Roman rule during the 7th decade, CE. Most scholars identify Judah of Gaulanitis as the founder of the Zealot Party. The adjective zealot (kana'i in Hebrew) to depict one who is zealous for the honor of God is as ancient as the Torah's account of Pinchas the zealot (see Numbers, 25:6-12), it has nothing to do with this militant party, and was not uncommonly used as a term of praise for especially, or "zealously," pious Jews, such as Simon the Zealot.

This was a wonderfully researched and written article. My fault is being shamelessly bemused by mythologies, thanks to the likes of Joseph Campbell. Either way, Ms. Green is clearly an idiot, and by the same token Mr. Aslan is clearly a fake. I believe the interview, which I don't wish to see in it's entirety, was a plant that Fox easily fell for. Could we expect anything less, from either side? And here ARE two sides. In closing, is there a Christian fatāwā on Aslan's life? I doubt it. And that, my friends, is the difference.

steve.gok2006

Not all Muslims believe that fatāwās are appropriate. Besides, conservative Christians have just handed the job over to God: they believe in being kind even to non-Christians but, later, during the Judgment, if a person doesn't accept J.C. as their Lord and Savior, they'll be condemned. Leave the dirty work to the Boss.

craigjbeckett

As a former evangelical Christian, the historic Jesus I encountered in my university days was extremely fascinating. Unfortunately I was studying Canadian History and English Lit...so I did not have too much time available for Jesus. Any books easily read by a lay person on the topic of the historical Jesus? I'm not sure I have the chops for Schafer's books at the moment.

vincent.calabrese

'Did Jesus Exist?:The Historical Argument for Jesus of Nazareth,' by Bart D. Ehrman, is a good one.

Frank Forth

Alas, I fear that Ehrman's tome on this topic is no better than Aslan's efforts on his topic. Ehrman has written a number of excellent books for the general reader. This isn't one of them.

I have read much of Bart Ehrman's work but not "Did Jesus Exist?:The Historical Argument for Jesus of Nazareth." However, I follow his blog, "Christianity in Antiquity" which has much fascinating material in it (there's a cost of about $25/yr. which all goes to charities). His Great Courses lectures (I prefer CD's), "The Historical Jesus" and "The New Testament," are excellent.

"If so, then why is one of Jesus' followers called Simon the Zealot? "

Pinchas, in the Old Testament, is also called Zealot. Are you suggesting that he too was a member of the Zealot party? Background on the use of the Hebrew term "zealot" (kanai) would be useful.

Thanks to JRB and Dr. Nadler for this article and for the references, some of which I haven't seen before (and thanks for y2bloch for his input on calling the area "Palestine," a common error that can have political implications itself).

This is the most thorough review of "Zealot" I've seen so far. Adam Kirsch, writing for Tablet, praised the book as giving a powerful portrait of Jesus, and Adam Gopnik, of The New Yorker, thought Aslan's book not out of the ordinary as far as portraits of the historical Jesus go. I also saw an early First Things piece in which the reviewer took issue with Aslan's credentials but said he wouldn't deign to read his book.

I'd like to see even more discussion and detail.

I would have found it very useful if Professor Nadler had included references to Geza Vermes and his studies on: the historical Jesus in the context and society of his time.

Perhaps Professor Nadler would consider appending his thoughts on this subject re the studies of the late Professor Vermes.

A serious take-down, with a real zinger at the end: Aslan as the Manchurian, nay, the Babylonian Candidate, manipulating the manipulators on Fox. The sad thing is that public life becomes viewed as a transgression by real scholars, and so along with their criticism of popular writers they relinquish their own responsibility, and possibility, to become an engaging public voice. Bravo to Professor Nadler for publishing a response in the Jewish Review. I am not suggesting he should go on Fox, but it would be nice to give Aslan credit for bringing attention to alternative readings of Jesus, and for fostering a public dialogue on this subject, as confounded as it might sometimes be.

johndavidhutsell

thanks for an interesting, educating article. i'm going to the library to check out Schafer, Boyarin, Segal and Herford. and Celsus if i can find him.

As a Catholic, I am indebted to Nadler's beautiful analysis of Aslan's book, showing his bias and rejection of Jesus's spiritualism and peace fullness. Oh, and how does a doctrinal program make a non-Jew an expert on Jewish religion and history?

Aside from those quibbles, Dr. Nadler, how did you like the book?