An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Subst Abuse

- PMC10176789

The Impact of Recreational Cannabis Legalization on Cannabis Use and Associated Outcomes: A Systematic Review

Kyra n farrelly.

1 Department of Psychology, York University, Toronto, ON, Canada

2 Peter Boris Centre for Addictions Research, St. Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada

Jeffrey D Wardell

3 Institute for Mental Health Policy Research, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto, ON, Canada

4 Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Emma Marsden

Molly l scarfe, peter najdzionek, jasmine turna.

5 Michael G. DeGroote Centre for Medicinal Cannabis Research, McMaster University & St. Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton, Hamilton, ON, Canada

James MacKillop

6 Homewood Research Institute, Guelph, ON, Canada

Background:

Recreational cannabis legalization has become more prevalent over the past decade, increasing the need to understand its impact on downstream health-related outcomes. Although prior reviews have broadly summarized research on cannabis liberalization policies (including decriminalization and medical legalization), directed efforts are needed to synthesize the more recent research that focuses on recreational cannabis legalization specifically. Thus, the current review summarizes existing studies using longitudinal designs to evaluate impacts of recreational cannabis legalization on cannabis use and related outcomes.

A comprehensive bibliographic search strategy revealed 61 studies published from 2016 to 2022 that met criteria for inclusion. The studies were predominantly from the United States (66.2%) and primarily utilized self-report data (for cannabis use and attitudes) or administrative data (for health-related, driving, and crime outcomes).

Five main categories of outcomes were identified through the review: cannabis and other substance use, attitudes toward cannabis, health-care utilization, driving-related outcomes, and crime-related outcomes. The extant literature revealed mixed findings, including some evidence of negative consequences of legalization (such as increased young adult use, cannabis-related healthcare visits, and impaired driving) and some evidence for minimal impacts (such as little change in adolescent cannabis use rates, substance use rates, and mixed evidence for changes in cannabis-related attitudes).

Conclusions:

Overall, the existing literature reveals a number of negative consequences of legalization, although the findings are mixed and generally do not suggest large magnitude short-term impacts. The review highlights the need for more systematic investigation, particularly across a greater diversity of geographic regions.

Introduction

Cannabis is one of the most widely used substances globally, with nearly 2.5% of the world population reporting past year cannabis use. 1 Cannabis use rates are particularly high in North America. In the U.S., 45% of individuals reported ever using cannabis and 18% reported using at least once annually in 2019. 2 , 3 In Canada, approximately 21% of people reported cannabis use in the past year use in 2019. 4 In terms of cannabis use disorder (CUD), a psychiatric disorder defined by clinically significant impairment in daily life due to cannabis use, 5 ~5.1% of the U.S. population ages 12+ years met criteria in 2020, with ~13.5% of individuals ages 18 to 25 years meeting criteria. 6

Overall, rates of cannabis use have shown long-term increasing trends among several age groups in North America. 7 - 9 Moreover, research has revealed recent cannabis use increases in at risk populations, such as individuals with depression and pregnant women. 10 , 11 Parallel to increased cannabis use over time, rates of cannabis-related consequences have also increased across Canada and the U.S., including cannabis dependence and CUD, 8 , 12 crime rates (eg, increased possession charges), 8 and cannabis-impaired driving (and, lower perception of impairment and risk from cannabis use). 11 , 13 , 14 Further, cannabis use poses a risk for early-onset or use during adolescence as there is evidence that cannabis use in adolescence is linked with poorer cognitive performance, psychotic disorders, and increased risk of mood and addictive disorders. 15 With the rates of negative consequences from cannabis use increasing, particularly in North America where cannabis has become legal in many parts of the US and all of Canada, understanding the role of cannabis legalization in these changes is crucial to inform ongoing changes in cannabis policies worldwide.

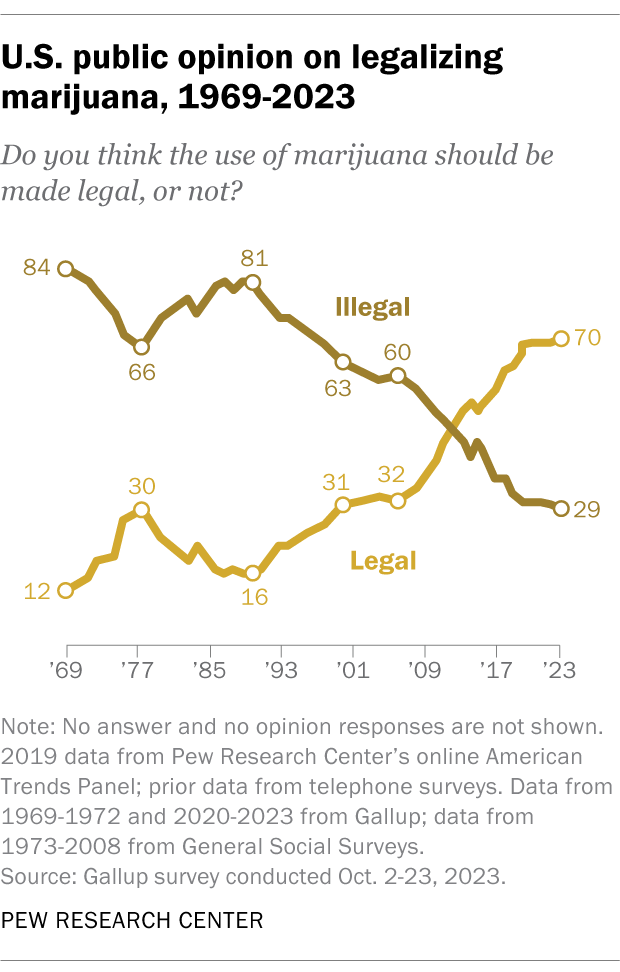

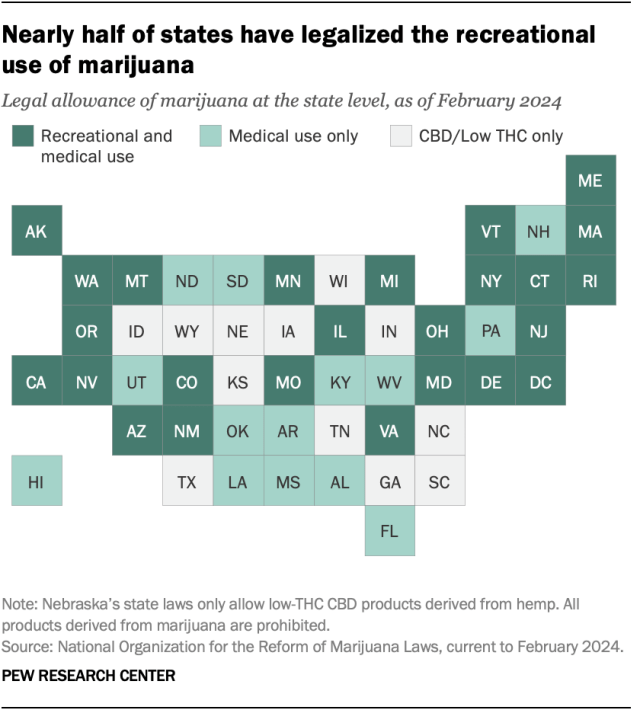

The legal status of cannabis varies widely across countries and regions. Although cannabis is largely illegal at the global level, policies surrounding cannabis use are becoming steadily liberalized. Decriminalization (reduced penalties for self-use but not distribution) is more widespread worldwide, including in the Netherlands, Portugal, and parts of Australia. Medical legalization is also seen in Peru, Germany, New Zealand, the Netherlands and across many U.S. states. To date, Canada, Uruguay, and Malta are the only 3 countries to legalize recreational cannabis use at the national level. Further, individual U.S. states began legalizing recreational cannabis in 2012, with nearly half of U.S. states having legalized recreational cannabis by 2023. As national and subnational recreational legalization continues to gain support and take effect, understanding the consequences of such major regulatory changes is crucial to informing ongoing policy changes.

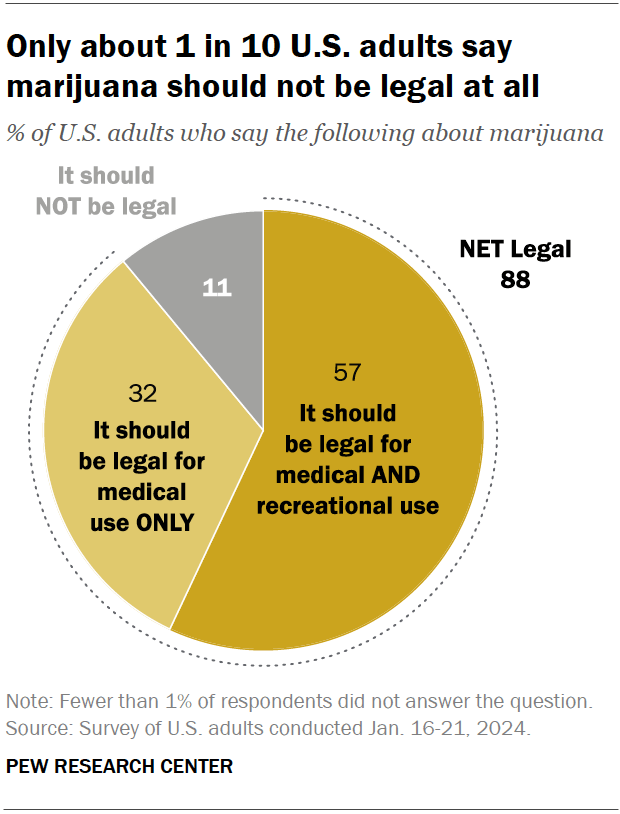

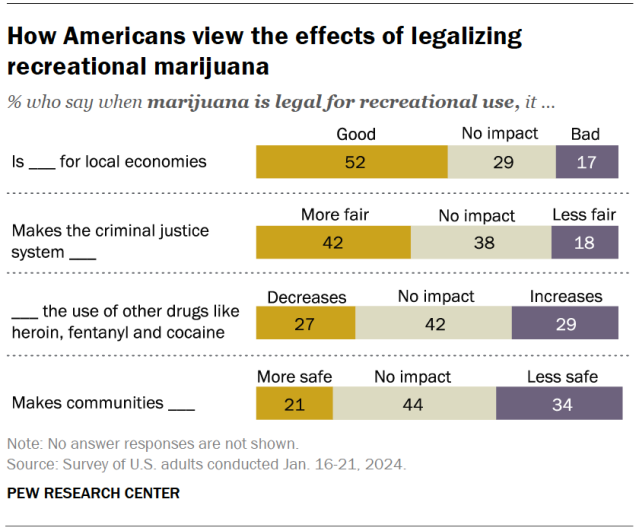

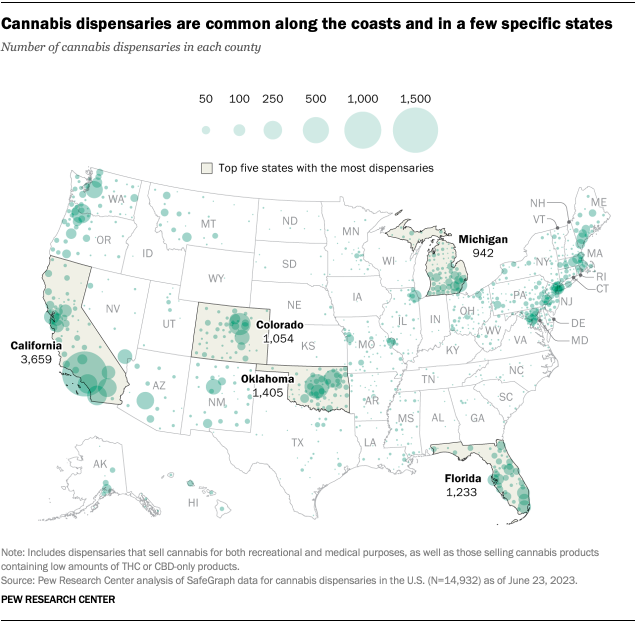

There are arguments both for and against recreational cannabis legalization (RCL). Common pro-legalization arguments involve increasing regulatory control over product distribution, weakening organized crime, reducing burden and inequality in the criminal justice system, and generating economic benefits such as tax revenues and commercial activity. 16 Furthermore, as cannabis obtained from illicit markets is of varying and unknown potency, 17 cannabis legalization may help better regulate the potency and quality of cannabis products. 18 On the other hand, there are anti-legalization arguments such as the possibility of legalization leading to increased use among youth and increased cannabis-impaired driving. 16 A nationally representative survey in the U.S. found that pro-legalization arguments were perceived to be more persuasive than public health anti-legalization arguments in a U.S. nationally representative survey, 19 suggesting policymaker concerns regarding RCL do not seem to hold as much weight in the general public. However, while research may be increasing surrounding the impacts of RCL, the general consensus of if RCL leads to more positive or negative consequences is unclear.

With RCL becoming more prevalent globally, the impacts it may have on a variety of health-related outcomes are of critical importance. Prevalence of cannabis use is of course a relevant issue, with many concerned that RCL will cause significant spikes in rates of cannabis use for a variety of groups, including youth. However, current studies have revealed mixed evidence in the U.S., 20 , 21 thus there is a need to synthesize the extant literature to better understand the balance of evidence and potential impacts of RCL across different samples and more diverse geographic areas. Another common question about RCL is whether it will result in changes in attitudes toward cannabis. These changes are of interest as they might forecast changes in consumption or adverse consequences. Similarly, there are concerns surrounding RCL and potential spill-over effects that may influence rates of alcohol and other substance use. 22 Thus, there remains a need to examine any changes in use of other substance use when studying effects of RCL.

Beyond changes in cannabis and other substance use and attitudes, health-related impacts of RCL are important to consider as there are links between cannabis use and adverse physical and mental health consequences (eg, respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, psychosis). 23 Additionally, emergency service utilization associated with cannabis consumption is a frequent concern associated with RCL, particularly due to the spikes in admissions following RCL in Colorado. 24 However, the rates of cannabis-related emergency service admissions more globally (eg, in legal countries like Canada and Uruguay) have not been fully integrated into summaries of the current literature. Finally, another health-related consequence of RCL is potential impacts on opioid use. While opioid-related outcomes can fall into substance use, they are considered health-related for this review as much of the discussion surrounding RCL and opioids involve cannabis substituting opioid use for medicinal reasons or using cannabis as an alternate to prescription opioids in the healthcare system. The current opioid crisis is a global public health problem with serious consequences. While there is evidence that medicinal cannabis may reduce prescription opioid use 25 and that cannabis may be a substitute for opioid use, 26 the role of recreational cannabis legalization should also be examined as the 2 forms of cannabis use are not interchangable 27 and have shown unique associations with prescription drug use. 28 Thus, there is a need to better understand how and if RCL has protective or negative consequences on opioid-related outcomes.

Due to the impairing effects of cannabis on driving abilities and the relationship with motor vehicle accidents, 29 another important question surrounding RCL is how these policy changes could result in adverse driving-related outcomes. An understanding of how RCL could influence impaired driving prevalence is needed to give insight into how much emphasis jurisdictions should put on impaired driving rates when considering RCL implementation. A final consequence of RCL that is often debated but requires a deeper understanding is how it impacts cannabis-related arrest rates. Cannabis-related arrests currently pose a significant burden on the U.S. and Canadian justice system. 30 , 31 Theoretically, RCL may ease the strain seen on the justice system and have positive trickle-down effects on criminal-related infrastructure. However, the overall implications of RCL on arrest rates is not well understood and requires a systematic evaluation. With the large number of RCL associated outcomes there remains a need to synthesize the current evidence surrounding how RCL can impact cannabis use and other relevant outcomes

Present review

Currently, no reviews have systematically evaluated how RCL is associated with cannabis-use changes across a variety of age groups as well as implications on other person- or health-related outcomes. The present review aims to fill an important gap in the literature by summarizing the burgeoning research examining a broad range of consequences of RCL across the various jurisdictions that have implemented RCL to date. Although previous reviews have considered the implications of RCL, 32 , 33 there has recently been a dramatic increase in studies in response to more recent changes in recreational cannabis use policies, requiring additional efforts to synthesize the latest research. Further, many reviews focus on specific outcomes (eg, parenting, 34 adolescent use 35 ). There remains a need to systematically summarize how RCL has impacted a variety of health-related outcomes to develop a more comprehensive understanding of the more negative and positive outcomes of RCL. While a few reviews have examined a broad range of outcomes such as cannabis use, related problems, and public health implications, 32 , 33 some reviews have been limited to studies from a single country or published in a narrow time window. 32 Thus, a broader review is necessary to examine multiple types of outcomes from studies in various geographic regions. Additionally, a substantial amount of the current literature examining the impact of RCL relies on cross-sectional designs (eg, comparing across jurisdictions with vs without recreational legalization) which severely limit any conclusions about causal associations. Thus, given its breadth, the current systematic review is more methodologically selective by including only studies with more rigorous designs (such as longitudinal cohort studies), which provide stronger evidence regarding the effects of RCL. In sum, the aim of the current review was to characterize the health-related impacts of RCL, including changes in these outcomes in either a positive or negative direction.

The review is compliant with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 36 ). Full-text extraction was initiated immediately following article search, therefore the protocol was not registered with PROSPERO. Relevant articles on cannabis legalization were principally identified using the Boolean search terms (“cannabis” OR “marijuana” OR “THC” OR “marihuana”) AND “legalization” AND (“recreational” OR “non-medical” OR “nonmedical”) AND (“longitudinal” OR “pre-post” OR “prospective” OR “timeseries” OR “cohort”). The search was conducted using PubMed/MEDLINE, EMBASE, and PsycINFO through November 2022. Relevant studies identified through secondary means (eg, prior knowledge of a relevant publication, articles brought to the authors’ attention) were also included for screening. Titles and abstracts resulting from the initial search were screened in Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation Inc) by 2 reviewers for suitability for full-text review and final inclusion. Conflicts were discussed by both reviewers and a final decision was made by consensus. Following screening, reviewers read and extracted relevant data. To be included, an article was required to meet the following criteria: (i) an original empirical research article published in a peer-reviewed journal; (ii) written in (or available in) English; (iii) RCL serves as an independent variable; (iv) quantitative study design that clearly permitted the evaluation of the role of RCL with a more rigorous non-cross-sectional study design (eg, pre- vs post-legalization, longitudinal, cohort, interrupted time series, etc.); and (v) reports on health-related outcomes (ie, changes in consumption or attitudes, as opposed to changes in price or potency).

RCL related outcomes that were considered were those specifically involving the behavior, perceptions, and health of individuals. Population-level outcomes (eg, health-care utilization or impaired driving) were considered eligible for inclusion as they involve the impacts that legalization has on individual behavior. Thus, economic- or product-level outcomes that do not involve individual behavior (eg, cannabis prices over time, changes in cannabis strain potency) were considered out of scope. The outcome groups were not decided ahead of time and instead 5 main themes in outcomes emerged from our search and were organized into categories for ease of presentation due to the large number of studies included.

Studies that examined medicinal cannabis legalization or decriminalization without recreational legalization, and studies using exclusively a cross-sectional design were excluded as they were outside the scope of the current review. The study also excluded articles that classified RCL as the passing of legal sales rather than implementation of RCL itself as RCL is often distinct from introduction of legal sales, or commercialization. Thus, we excluded studies examining commercialization as they were outside the scope of the current review.

Characteristics of the literature

The search revealed 65 relevant articles examining RCL and related outcomes (see Figure 1 ). There were 5 main themes established: cannabis use and other substance use behaviors ( k = 28), attitudes toward cannabis ( k = 9), health-related outcomes ( k = 33), driving related impacts ( k = 6), and crime-related outcomes ( k = 3). Studies with overlapping themes were included in all appropriate sections. Most studies (66.2%) involved a U.S. sample, 32.3% examined outcomes in Canada, and 1.5% came from Uruguay. Regarding study design, the majority (46.2%) utilized archival administrative data (ie, hospital/health information across multiple time points in one jurisdiction) followed by cohort studies (18.5%). The use of administrative data was primarily used in studies examining health-related outcomes, such as emergency department utilization. Studies examining cannabis use or attitudes over time predominantly used survey data. Finally, both driving and crime related outcome studies primarily reported findings with administrative data.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) study flow diagram.

Changes in cannabis and other substance use

Cannabis and other substance use changes represented the second largest number of studies, with 28 articles identified. Studies examining changes in cannabis use behaviors were divided by subpopulation (ie, adolescents, young adults, general population adults, clinical populations, and maternal use; see Table 1 ). Finally, we separately summarized studies reporting changes in concurrent use of other substances, and routes of cannabis administration.

Studies investigating the role of recreational cannabis legalization on cannabis and other substance consumption.

Author, author of article; Year, publication year of article; Location, jurisdiction article data was collected in; Date of Legalization, year legalization was enacted in jurisdiction; Sample, total N of article sample; RCL, Recreational Cannabis Legalization.

Cannabis use changes in adolescents (~12-17)

Ten studies examined changes in cannabis use among adolescents and found that changes in the rates of use were inconsistent following RCL. Gunadi et al 37 found an association between RCL and more pronounced transition from non-use to cannabis use when compared to states with no legalization and those with medical cannabis legalization ( P ⩽ .001) combined, but not when compared to states with medical cannabis legalization only. Another study found that in states with RCL adolescents who never used cannabis but used e-cigarettes were more likely to use cannabis at follow-up than those living in states without RCL (aOR = 18.39, 95% CI: 4.25-79.68vs aOR = 5.09, 95% CI: 2.86-9.07, respectively) suggesting a risk of cannabis initiation among legal states. 38 Among adolescents reporting recent alcohol and cannabis co-use, one study found a significant increase in the frequency of past 30-day cannabis use following RCL ( b = 0.36, SE = 0.07, P ⩽ .001). 39 In a Canadian study using a repeated cross-sectional design as well as a longitudinal design to examine changes in cannabis use, results revealed that adolescents had increased odds of ever using cannabis in the year following RCL in the cross-sectional data ( P = .009). 40 However, the longitudinal sample revealed no significant differences in the odds of ever use, current use, and regular use of cannabis post-legalization. There is also evidence of RCL impacts on adolescent cannabis use consequences, as a Washington study found a significant indirect effect of RCL on cannabis consequences through perceived risk as a mediator ( B = 0.37, P ⩽ .001). 41

On top of the above evidence, there were multiple studies examining cannabis use changes over time among adolescents in Washington and Oregon that found higher rates of cannabis use associated with cohorts examined during RCL compared to non-legal cohorts, 42 - 44 although the differences across legal cohorts were not significant in all cases. 42 Furthermore, in another study, RCL did not impact initiation of use, but for current users the RCL group had significantly greater increased rates of cannabis use compared to the pre-RCL group (RR = 1.26, 95% CI = 1.10, 1.45). 43 For the final study, cannabis use increased in the post-RCL group but patterns of use (frequency; daily vs weekly use) were similar across groups. 44 Overall, the preceding 8 studies reveal some evidence that RCL was associated with increasing rates of cannabis use in adolescent. However, 5 studies point to some inconsistent associations of RCL and cannabis use and suggest that overall relationship of RCL and adolescent cannabis as mixed.

Three studies add to these inconsistent findings and point to lack of an association between RCL and changes in cannabis use among adolescents. Two studies found no significant increase in the frequency of or prevalence of cannabis use following RCL. 41 , 45 Finally, a study examining trends of adolescent cannabis use and associations with period effects (ie, external world events that could influence use) suggests laws and regulations associated with RCL were not associated with cannabis use changes. 46 The current research reveals conflicting evidence about the role of RCL on adolescent cannabis use.

Cannabis use changes in young adults (~18-25)

Young adulthood, typically defined as ages 18 to 25 and also known as emerging adulthood, is commonly associated with decreased parental supervision, increased availability of substances, and greater substance experimentation making it a key developmental period for the onset of cannabis use. 47 Four studies examined the impact of RCL on cannabis use among young adults, 2 of which found significant associations between RCL and increased cannabis use in college students. 47 , 48 Barker and Moreno 48 found the rate of students ever using cannabis did not change. However, in those who had used cannabis prior to RCL, the proportion of students using in the past 28-days increased faster following RCL in Washington (legal-state) when compared with the rate of increase in Wisconsin (non-legal state; P ⩽ .001). 48 Further, in college students from Oregon, rates of cannabis use increased significantly from before to after RCL ( P = .0002). 47 Another study looked at changes in cannabis use in a sample of young adults from the U.S. who had never vaped cannabis at the time of recruitment. 49 Results revealed that cannabis use in the past year did not differ in states with or without RCL, although, those living in states with RCL did show a larger increase in rates of cannabis vaping across time, compared to those in non-RCL states. Finally, in a sample of youth from Oregon and Washington, RCL predicted a higher likelihood of past-year cannabis use ( P = .001). 50 In contrast to the adolescent literature, studies examining cannabis use in young adult samples fairly consistently point to an association between RCL and increasing rates of cannabis use.

Cannabis use changes in general population adults

Five studies examined changes in cannabis use in adults (without further age subclassification) associated with RCL. Four of these studies suggested higher rates of cannabis use in adults for RCL jurisdictions compared to non-legal states post-RCL, or increased use following RCL. 37 , 45 , 51 , 52 Past 30-day cannabis use increased significantly 1-month post-RCL and remained elevated 6-months post-RCL (ps = 0.01) in a sample of adults from California. 51 Another study found an association between RCL and transition from non-users to cannabis users and non-users to weekly users when compared to states with no medical legalization or RCL ( P ⩽ .001) and states with no legalization combined with those with medical cannabis legalization ( P ⩽ .001). 37 Meanwhile, in Canada, a significant increase in prevalence of cannabis use was observed following RCL. 45 Additionally, in those reporting no cannabis use prior to RCL in Canada, there were significant increases in cannabis use frequency, quantity of cannabis used, and severity of cannabis misuse following RCL. 52 The opposite pattern was seen for those reporting cannabis use prior to RCL, with significant decreases in frequency of use, quantity, and misuse. 52 However, not all studies found RCL was associated with increased cannabis use. For instance, a repeated cross-sectional study of adult in the U.S. found no association between RCL and frequency of cannabis use. 53

A benefit of the extant literature examining general population cannabis use is that it covers a variety of jurisdictions and study designs, albeit with some heterogeneity and mixed findings. On balance, the evidence within the current literature, generally suggests an increase in cannabis use for adults in the general population following RCL with 80% of the reviewed studies supporting this conclusion.

Maternal use

Three studies examined whether rates of cannabis use during pregnancy have increased following RCL. Two studies suggested increased cannabis use during pregnancy associated with RCL. In one study urine screen-detected cannabis use during pregnancy increased from 6% to 11% following RCL in California ( P = .05). 54 Another study in a sample of women participating in an intensive case management program for heavy alcohol and/or drug use during pregnancy, examined cannabis use among those exiting from the program before versus after RCL. Findings revealed women exiting after RCL were more likely to report using cannabis in the 30 days prior to exit compared to those pre-RCL (OR = 2.1, P ⩽ .0001). 55 One study revealed no significant difference in cannabis or alcohol use associated with RCL in women living with HIV during pregnancy or the postpartum period. 56 Overall, the evidence from these three studies suggests there may be increases in perinatal cannabis use following RCL, but the small number of studies and unique features of the samples suggests a need for more research.

Clinical populations use

Six studies examined cannabis use in clinical populations. One study investigated use and trauma admissions for adults and pediatric patients in California. 57 Results showed an increase in adult trauma patients with THC+ urine tests from pre- to post-RCL (9.4% to 11.0%; P = .001), but no difference for pediatric trauma patients. A study based in Colorado and Washington, found that cannabis use rates in inflammatory bowel disease patients significantly increased from 107 users to 413 ( P ⩽ .001) pre to post-RCL. 58 A Canada-based study of women with moderate-to-severe pelvic pain found an increase in the prevalence of current cannabis use following RCL (13.3% to 21.5%; P ⩽ .001). 59 Another Canadian study showed an increase in the prevalence of current cannabis use after RCL among cancer patients (23.1% to 29.1%; P ⩽ .01). 60 Finally, two studies examined changes in cannabis use among individuals receiving treatment for a substance use disorder. In a sample of Canadian youth in an outpatient addictions treatment program, there was no change in the rate of cannabis use following RCL. 61 Further, in a sample of individuals receiving treatment for opioid use disorder, cannabis use was compared for those recruited 6 months before or after RCL with no significant changes in the prevalence or frequency of self-reported ( P = .348 and P = .896, respectively) or urine screen-detected ( P = .087 and P = .638, respectively) cannabis use following RCL. 62 Although these studies only represent a small number of observations, their findings do reveal associations between RCL and increasing cannabis use within some clinical samples.

Changes in polysubstance and other substance use

One study examined simultaneous cannabis and alcohol use among 7th, 9th, and 11th grade students in the U.S. 39 This study found that RCL was associated with a 6% increase in the odds of past 30-day alcohol and cannabis co-use. The association was even stronger in students with past 30-day alcohol use and heavy drinking. However, among past 30-day cannabis users, RCL was associated with a 24% reduction in co-use. This study suggests at least a modest association between RCL and concurrent cannabis and alcohol use among adolescents.

Numerous studies examined changes of alcohol and other substance use pre to post RCL. With regard to alcohol, one study from Colorado and Washington found a decrease in alcohol consumption among adolescents following RCL, 42 whereas another Washington study found RCL predicted a higher likelihood of alcohol use among youth. 50 A Canadian study also found no significant effect of RCL on rates of alcohol or illicit drug use among youth. 61 Finally, in a sample of trauma patients in California the findings around changes in substance use were mixed. 57 In adult patients, the rates of positive screens for alcohol, opiates, methamphetamine, benzodiazepine/barbiturate, and MDMA did not change following RCL, but there was an increase in positive screens for cocaine. In pediatric patients, increases were seen in positive screens for benzodiazepine/barbiturate, but positive screens for alcohol, opiates, methamphetamine, and cocaine did not change. 57 The current evidence is divided on whether RCL is associated with increased alcohol and other substance use, with 40% of studies finding an association and 60% not observing one or finding mixed results.

In the case of cigarettes, Mason et al 42 did find significant cohort effects, where the post-RCL cohort was less likely to consume cigarettes compared to the pre-RCL one (Coefficient: − 2.16, P ⩽ .01). However, these findings were not echoed in more recent studies. Lack of an effect for cigarette use is supported by an Oregon study that found RCL was not associated with college student’s cigarette use. 47 Similarly, RCL was not significantly associated with past-year cigarette use in a sample of young adults from Oregon and Washington. 50 On balance, there is little evidence that RCL is linked with changes in cigarette smoking.

Route of administration

The increase in smoke-free alternative routes of cannabis administration (eg, vaping and oral ingestion of edibles) 63 , 64 make method of cannabis consumption an important topic to understand in the context of RCL. Two studies examined differences in route of cannabis consumption as a function of cannabis policy. One study examined changes in the number of different modes of cannabis use reported by high school students in Canada. 65 Results showed that from pre-to-post RCL 31.3% of students maintained a single mode of use, 14.3% continued to use cannabis in multiple forms, while 42.3% expanded from a single mode to multiple modes of administration and 12.1% reduced the number of modes they used. Another study found that smoking, vaping, and edibles (in that order) were the most frequent modes of cannabis use pre- and post-RCL in California, suggesting minimal impact of RCL on mode of cannabis use. 51 However, the least common mode of cannabis use was blunts, which did decline following RCL (13.5%-4.3%). 51 Overall, the evidence suggests RCL may be associated with changes in modes of cannabis consumption, but as the evidence is only from two studies there still remains a need for more studies examining RCL and cannabis route of administration.

Nine studies examined RCL and cannabis attitudes (see Table 2 ). Regarding cannabis use intentions, one U.S. study found that for both a non-RCL state and a state that underwent RCL, intention to use in young adults significantly increased post-RCL, suggesting a lack of RCL specific effect, 48 and that aside from the very first time point, there were no significant differences between the states in intention to use. Further, attitudes and willingness to use cannabis, between the RCL and non-RCL state remained similar overtime ( P s ⩾ .05), although both states reported significantly more positive attitudes toward cannabis following RCL ( P ⩽ .001). 48 However, another study U.S. from found differences in adolescent use intentions across RCL, whereby those in the RCL cohort in jurisdictions that allowed sales were less likely to increase intent to use cannabis ( P = .04), but the RCL cohort without sales were more likely to increase intent to use ( P = .02). 43 The pre-RCL cohort in communities that opted out of sales were also less likely to increase willingness to use compared to the cohort with legal sales ( P = .02). 43 Both studies reveal contrasting findings surrounding RCL’s relationship with cannabis use intentions and willingness to use.

Studies examining recreational cannabis legalization and attitudes surrounding cannabis.

Looking at cannabis use motives, one study found a non-significant increase in recreational motives for cannabis use post-RCL. 60 Similarly following RCL in Canada, 24% of individuals previously reporting cannabis use exclusively for medical purposes declared using for both medical and non-medical purposes following RCL, and 24% declared use for non-medical purposes only, 66 suggesting RCL can influence recreational/nonmedicinal motivations for cannabis use among those who previously only used for medical reasons.

In studies examining perceived risk and perceptions of cannabis use, one U.S. study found an indirect effect between RCL and increased consequences of use in adolescents through higher perceived risk ( P ⩽ .001), but no association with frequency of use. 41 Another U.S. study revealed mixed results and found that RCL was not associated with perceived harm of use in youth. 50 Further, youth in one study did not report differences in perceptions of safety of cannabis, ease of accessing cannabis use or on concealing their use from authority, 61 which contrasts with another study finding increased reports of problems accessing cannabis post-RCL ( P ⩽ .01). 60 Regarding health perceptions, a California study found that cannabis use was perceived as more beneficial for mental health, physical health, and wellbeing in adults at 6 months post-RCL compared to pre-RCL and 1-month post-RCL ( P = .02). 51 Mental health perceptions of cannabis use increased from being perceived as “slightly harmful” pre-RCL to perceived as “slightly beneficial” at 6 months post-RCL. 51 However, in a sample of treatment seeking individuals with an opioid use disorder, the vast majority of participants reported beliefs that RCL would not impact their cannabis use, with no difference in beliefs pre- to post-RCL (85.9% reported belief it would have no impact pre-RCL and 85.7%, post-RCL). 62 The combined results of the studies suggest potential associations of RCL with risk and benefit perceptions of cannabis use, however as 55% of studies suggest a lack of or inconsistent association with RCL, on balance the literature on RCL’s impact on cannabis attitudes is mixed.

Health-related outcomes

We identified 33 articles that examined various health-related outcomes associated with RCL (see Table 3 ). The largest number involved hospital utilization (ie, seeking emergency services for cannabis-related problems such as unintentional exposure, CUD, and other harms). Other health-care outcomes included opioid-related harms, mental health variables, and adverse birth outcomes.

Studies investigating the relationship of recreational cannabis legalization and health-related outcomes.

Author, Author of article; Year, Publication year of article; Location, Jurisdiction article data was collected in; Date of Legalization, Year legalization was enacted in jurisdiction; Sample, Total N of article sample; CDC, Center for Disease Prevention; WONDER, Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research; RCL, Recreational Cannabis Legalization.

Emergency service utilization

Seventeen studies examined the association between RCL and use of emergency services related to cannabis (eg, hospital visits, calls to regional poison centers). Regarding emergency service rates in youth, a Colorado study found the rate of pediatric cannabis-related emergency visits increased pre- to post-RCL ( P ⩽ .0001). 67 Similarly, cannabis-related visits requiring further evaluation in youth also increased. 67 This increasing need for emergency service related to cannabis exposure in youth following RCL was supported in 4 other U.S. studies. 68 - 71 A Canadian study supported the U.S. studies, finding a 2.6 increase in children admissions for cannabis poisonings post-RCL. 72 In contrast, overall pediatric emergency department visits did not change from pre- to post-RCL in Alberta, Canada, 73 but there was a non-significant increase of the rate and proportion of children under 12 presenting to the emergency department. However, unintentional cannabis ingestion did increase post-RCL for children under 12 (95% CI: 1.05-1.47) and older adolescents (1.48, 95% CI: 1.21-1.81). 74 Taken together, these studies do suggest a risk for increasing cannabis-related emergency visits in youth following RCL, with 75% of studies finding an association between RCL and increasing emergency service rates in youth.

There is also evidence of increased hospital utilization in adults following RCL. Five studies found evidence of increased emergency service utilization or poison control calls from cannabis exposure associated with RCL in the U.S. and Canada. 24 , 69 , 74 - 76 Finally, a Colorado study saw an increase in cannabis involved pregnancy-related hospital admissions from 2011 to 2018, with notable spikes after 2012 and 2014, timeframes associated with state RCL. 77

However, some evidence points to a lack of association between RCL and emergency service utilization. A chart review in Ontario, Canada found no difference in number of overall cannabis emergency room visits pre- versus post-RCL ( P = .27). 78 When broken down by age group, visits only increased for those 18 to 29 ( P = .03). This study also found increases in patients only needing observation ( P = .002) and fewer needing bloodwork or imaging services (both P s ⩽.05). 78 Further in a California study that found overall cannabis exposure rates were increasing, when breaking these rates down by age there was no significant change in calls for those aged 13 and up, only for those 12 and under. 69 An additional Canadian study found that rates of cannabis related visits were already increasing pre-RCL. 79 Following RCL, although there was a non-significant immediate increase in in cannabis-related emergency visits post-RCL this was followed a significant drop off in the increasing monthly rates seen prior to RCL. 79 Another Canadian study that examined cannabis hyperemesis syndrome emergency visits found that rates of admissions were increasing prior to RCL and the enactment of RCL was not associated with any changes in rates of emergency admissions. 80 As this attenuation occurred in Canada prior to commercialization where strict purchasing policy was in place, it may suggest that having proper regulations in place can prevent the uptick in cannabis-related emergency visits seen in U.S. studies.

Other hospital-related outcomes examined included admissions for cannabis misuse and other substance use exposure. One study found decreasing CUD admission rates over time (95% CI: −4.84, −1.91), with an accelerated, but not significant, decrease in Washington and Colorado (following RCL) compared to the rest of the U.S. 81 In contrast, another study found increased rates of healthcare utilization related to cannabis misuse in Colorado compared to New York and Oklahoma ( P s ⩽.0005). 82 With respect to other substance use, findings revealed post-RCL increases in healthcare utilization in Colorado for alcohol use disorder and overdose injuries but a decrease in chronic pain admissions compared to both controls ( P ⩽ .05). 82 However, two Canadian studies found the rate of emergency department visits with co-ingestant exposure of alcohol, opioid, cocaine, and unclassified substances in older adolescents and adults decreased post-RCL. 73 , 77 Another Canadian study found no change in cannabis-induced psychosis admissions nor in alcohol- or amphetamine-induced admissions. 83

Finally, three studies examined miscellaneous hospital-related outcomes. A study examining hospital records in Colorado to investigate facial fractures (of significance as substance impairment can increase the risk of accidents) showed a modest but not significant influence of RCL. 84 The only significant increases of facial trauma cases were maxillary and skull base fracture cases ( P s ⩽ .001) suggesting a partial influence of RCL on select trauma fractures. The second study found increased trauma activation (need for additional clinical care in hospital) post-RCL in California ( P = .01). 57 Moreover, both adult and pediatric trauma patients had increased mortality after RCL ( P = .03; P = .02, respectively). 57 The final study examining inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) outcomes in the U.S. found more cannabis users on total parenteral nutrition post-RCL (95% CI: 0.02, 0.89) and lower total hospital costs in users post-RCL (95% CI: −15 717, −1119). 58 No other IBD outcomes differed pre- to post-RCL (eg, mortality, length of stay, need for surgery, abscess incision and drainage).

Overall, these studies point to increased cannabis-related health-care utilization following RCL for youth and pediatrics (75% finding an increase). However, the impact of legalization on adult rates of cannabis-related emergency visits is mixed (44% finding lack of an association with RCL). As findings also varied across different countries (ie, Canada vs the U.S.), it suggests the importance of continually monitoring the role of RCL across different jurisdictions which may have different cannabis regulations in place. These studies also suggest there may be other health consequences associated with RCL. Further research should be done to examine trends of other emergency service use that could be influenced by RCL.

Two studies reported a weak or non-existent effect of RCL on opioid related outcomes. 85 , 86 First, a U.S. administrative study found no association of RCL and opioid prescriptions from orthopedic surgeons. 85 The second study found that, of U.S. states that passed RCL, those that passed policies before 2015 had fewer Schedule III opioid prescriptions ( P = .003) and fewer total doses prescribed ( P = .027), 86 but when compared to states with medicinal cannabis legislation, there were no significant differences. However, 3 studies suggested a potential protective effect of RCL, with one study finding a significant decrease for monthly opioid-related deaths following RCL (95% CI: –1.34, –0.03), compared to medical cannabis legalization and prohibition. 87 A Canadian study examining opioid prescription claims also found an accelerated decline in claims for public payers post-RCL compared to declines seen pre-RCL ( P ⩽ .05). 88 Next a study examining women with pelvic pain found that post-RCL patients were less likely to report daily opioid use, including use for pain ( P = .026). 59 These studies indicate some inconsistencies in relationships between RCL, opioid prescriptions and use indicators in the current literature, while the literature on balance points to a potential relationship with RCL (60%), the overall evidence is still mixed as 40% of studies support a weak association with RCL.

Adverse birth outcomes

Changes in adverse birth outcomes including small for gestational age (SGA) births, low birth weight, and congenital anomalies were examined in two studies. The first study, which examined birth outcomes in both Colorado and Washington, found that RCL was associated with an increase in congenital anomaly births for both states ( P ⩽ .001, P = .01 respectively). 89 Preterm births also significantly increased post-RCL, but only in Colorado ( P ⩽ .001). Regarding SGA outcomes, there was no association with RCL for either state. 89 Similarly, the second study did find an increase in the prevalence of low birth weight and SGA over time, but RCL was not directly associated with these changes. 90 Although the current literature is small and limited to studies in Washington and Colorado, the evidence suggests minimal changes in adverse birth outcomes following RCL.

Mental health outcomes

Six studies examined mental health related outcomes. A Canadian study examining psychiatric patients did not see a difference in rates of psychotic disorders pre- to post-RCL. 45 Similarly, another Canadian study did not see a difference in hospital admissions with schizophrenia or related codes post-RCL. 83 However, the prevalence of personality disorders and “other” diagnoses was higher post-RCL ( P = .038). 45 In contrast, another Canadian study found that rates of pediatric cannabis-related emergency visits with co-occurring personality and mood-related co-diagnoses decreased post-RCL among older adolescents. 73 A U.S. study examining the relationship between cannabis use and anxious mood fluctuations in adolescents found RCL had no impact on the association. 91 Similarly, another Canadian study found no difference in mental health symptomology pre- to post-RCL. 61 In contrast, anxiety scores in women with pelvic pain were higher post-RCL compared to pre-RCL ( P = .036). 59 The small number and mixed findings of these studies, 66.7% finding no association or mixed findings and 33.3% finding an association but in opposite directions, identify a need for further examination of mental health outcomes post-RCL.

Miscellaneous health outcomes

Three studies examined additional health-related outcomes. First, a California study examined changes in medical cannabis status across RCL. Post-RCL, 47.5% of medical cannabis patients remained medical cannabis patients, while 73.8% of non-patients remained so. 92 The transition into medical cannabis patient status post-RCL represented the smallest group (10%). Cannabis legalization was the most reported reason for transition out of medical cannabis patient status (36.2%). 92 Next, a study examining pelvic pain in women found that post-RCL patients reported greater pain catastrophizing ( P ⩽ .001), less anti-inflammatory ( P ⩽ .001) and nerve medication use ( P = .027), but more herbal pain medication use ( P = .010). 59 Finally, a Canadian study that examined cannabinoids in post-mortem blood samples reported that post-RCL deaths had higher odds of positive cannabis post-mortem screens compared to pre-RCL (95% CI: 1.09-1.73). 93 However, the majority of growth for positive cannabinoid screens took place in the two years prior to RCL implementation. In sub-group analyses, only 25- to 44-year-olds had a significant increase in positive cannabinoid screens (95% CI: 0.05-0.19). Additional post-mortem drug screens found an increase in positive screens for amphetamines ( P ⩽ .001) and cocaine ( P = .042) post-RCL. These additional health outcomes demonstrate the wide-ranging health impacts that may be associated with RCL and indicate a continued need to examine the role of RCL on a variety of outcomes.

Driving-related outcomes

Six studies examined rates of motor vehicle accidents and fatalities (see Table 4 ). Two U.S. studies found no statistical difference in fatal motor vehicle collisions associated with RCL. 94 , 95 Further, a California-based study examining THC toxicology screens in motor vehicle accident patients, did find a significant increase in positive screens, but this increase was not associated with implementation of RCL. 96 However, three studies suggest a negative impact of RCL, as one U.S. study found both RCL states and their neighboring states had an increase in motor vehicle fatalities immediately following RCL. 97 Additionally, a Canadian study did find a significant increase in moderately injured drivers with cannabis positive blood screens post-RCL. 98 Finally, a study in Uruguay found RCL was associated with increased immediate fatal crashes for cars, but not motorcycles; further investigation suggested this effect was noticeable in urban areas, but not rural areas. 99 While the overall evidence was inconsistent, current evidence does suggest a modest increase, seen in two studies, in motor vehicle accidents associated with RCL. Further longitudinal research in more jurisdictions is needed to understand the long-term consequences of RCL on motor vehicle accidents.

Studies looking at recreational cannabis legalization and driving related outcomes.

Crime-related outcomes

Three studies explored crime-related outcomes associated with RCL (see Table 5 ). A Washington study examining cannabis-related arrest rates in adults did find significant drops in cannabis-related arrests post-RCL for both 21+ year olds (87% drop; P ⩽ .001) and 18 to 20-year-olds (46% drop; P ⩽ .001). 100 However, in another study examining Oregon youth this post-RCL decline for arrests was not seen; cannabis-related allegations in youth actually increased following RCL (28%; 95% CI = 1.14, 1.44). 101 Further, declines in youth allegations prior to RCL ceased after RCL was implemented. In contrast, a Canadian study did find significant decreases in cannabis-related offenses in youth post RCL ( P ⩽ .001), but rates of property and violent crime did not change across RCL. 102 These studies highlight the diverse effects of RCL across different age groups. However, there remains a need for a more comprehensive evaluation on the role of RCL on cannabis-related arrests.

Studies investigating recreational cannabis legalization and crime related outcomes.

Author, Author of article; Year, Publication year of article; Location, Jurisdiction article data was collected in; Date of Legalization, Year legalization was enacted in jurisdiction; Sample, Total N of article sample; RCL, Recreational Cannabis Legalization.

Notably, two studies also examined race disparities in cannabis-related arrests. For individuals 21+ relative arrest disparities between Black and White individuals grew post-RCL. 100 When looking at 18 to 20-year-olds, cannabis-related arrest rates for Black individuals did slightly decrease, albeit non-significantly, but there was no change in racial disparities. 100 In youth ages 10 to 17, Indigenous and Alaska Native youth were more likely than White youth to receive a cannabis allegation before RCL (95% CI: 2.31, 3.01), with no change in disparity following RCL (95% CI: 2.10, 2.81). 101 On the other hand, Black youth were more likely to receive a cannabis allegation than White youth prior to RCL (95% CI: 1.66, 2.13), but the disparity decreased following RCL (95% CI: 1.06, 1.43). 101 These studies suggest improvements in racial disparities for cannabis-related arrests following RCL, although there ware only two studies and they are limited to the U.S.

The aim of this systematic review was to examine the existing literature on the impacts of RCL on a broad range of behavioral and health-related outcomes. The focus on more rigorous study designs permits greater confidence in the conclusions that can be drawn. The literature revealed five main outcomes that have been examined: cannabis use behaviors, cannabis attitudes, health-related outcomes, driving-related outcomes, and crime-related outcomes. The overall synthesizing of the literature revealed heterogenous and complex effects associated with RCL implementation. The varied findings across behavioral and health related outcomes does not give a clear or categorical answer as to whether RCL is a negative or positive policy change overall. Rather, the review reveals that while a great deal of research is accumulating, there remains a need for more definitive findings on the causal role of RCL on a large variety of substance use, health, attitude-related, driving, and crime-related outcomes.

Overall, studies examining cannabis use behavior revealed evidence for cannabis use increases following RCL, particularly for young adults (100%), peri-natal users (66%), and certain clinical populations (66%). 47 , 54 , 59 While general adult samples had some mixed findings, the majority of studies (80%) suggested increasing rates of use associated with RCL. 51 Of note, the increasing cannabis use rates found in peri-natal and clinical populations are particularly concerning as they do suggest increasing rates in more vulnerable samples where potential adverse consequences of cannabis use are more pressing. 103 However, for both groups the overall literature revealed only a few studies and thus requires further examination. Further, a reason to caution current conclusions surround RCL impacts on substance use, is that there is research suggesting cannabis use rates were increasing prior to RCL in Canada. 104 Thus, there still remains a need to better disentangle causal consequences of RCL on cannabis use rates.

In contrast to studies of adults, studies of adolescents pointed to inconsistent evidence of RCL’s influence on cannabis use rates, 38 , 45 with 60% of studies finding no change or inconsistent evidence surrounding adolescent use following RCL. Thus, a key conclusion of the cannabis use literature is that there is not overwhelming evidence that RCL is associated with increasing rates of cannabis among adolescents, which is notable as potential increases in adolescent use is a concern often voiced by critics of RCL. 16 This might suggest that current RCL policies that limit access to minors may be effective. However, a methodological explanation for the discrepancy between findings for adolescents and adults is that adults may be more willing to report their use of cannabis following RCL as it is now legal for them to use. However, for adolescents’ cannabis use remained illicit, which may lead to biased reporting from adolescents. Thus, additional research using methods to overcome limitations of self-reports may be required.

With regard to other substance use, primarily alcohol and cigarettes, there is little evidence that RCL is associated with increased use rates and may even be associated with decreased rates of cigarette use. 42 , 61 The lack of a relationship with RCL and increasing alcohol and other substance use, seen in 60% of studies, is relevant due to concerns of RCL causing “spill-over” effects to substances other than cannabis. However, the decreasing rates on cigarette use associated with RCL seen in 33% of studies may also suggest a substitution effect of cannabis. 105 It is possible that RCL encourages a substitution effect where cannabis is used to replace use other substances such as cigarettes, but 66% of studies found no association of RCL and cigarette use so further research examining a potential substitution effect is needed. In sum, the literature points to a heterogenous impact of RCL on cannabis and other substance use rates, suggesting complex effects of RCL on use rates that may vary across age and population. However, the review also highlights that there are still limited studies examining RCL and other substance use, particularly a lack of multiple studies examining the same age group.

The current evidence for the impact of RCL on attitudes surrounding cannabis revealed mixed or limited results, with 44% studies finding some sort of relationship with attitudes and RCL and 55% studies suggest a lack of or inconsistent relationship. Studies examining cannabis use attitudes or willingness to use revealed conflicting evidence whereas some studies pointed to increased willingness to use associated with RCL, 43 and others found no change or that changes were not specific to regions that implemented RCL. 48 For attitude-related studies that did reveal consistent findings (eg, use motivation changes, perceptions of lower risk and greater benefits of use), the literature was limited in the number of studies or involved heterogenous samples, making it difficult to make conclusive statements surrounding the effect of RCL. As cannabis-related attitudes (eg, perceived risk, intentions to use) can have implications for cannabis use and consequences 106 , 107 it is interesting that current literature does not reveal clear associations of cannabis-related attitudes and RCL. Rather, this review reveals a need for more research examining changes in cannabis-attitudes over time and potential impacts of RCL.

In terms of health outcomes, the empirical literature suggests RCL is associated with increased cannabis-related emergency visits 24 , 67 , 70 , 76 and other health consequences (eg, trauma-related cases 57 ). The literature also suggests there may be other potential negative health consequences associated with RCL, such as increasing adverse birth outcomes and post-mortem cannabis screens. 45 , 89 Synthesizing of the literature points to a well-established relationship of RCL and increasing cannabis-related emergency visits. While some extant literature was mixed, on balance most studies included in the review (70.6%) found consistent evidence of increased emergency service use (eg, emergency department admissions and poison control calls) for both adolescents and adults with only 31% of studies finding mixed or no association with RCL. This points to a need for stricter RCL policies to prevent unintentional consumption or hyperemesis such as promoting safe or lower risk use of cannabis (eg, using lower THC products, avoiding deep inhales while smoking), clearer packaging for cannabis products, and safe storage procedures.

However, the literature on health outcomes outside of emergency service utilization is limited and requires more in-depth evaluations to be fully understood. Additionally, not all health-outcomes indicated negative consequences associated with RCL. There is emerging evidence of the potential of RCL to help decrease CUD and multiple substance hospital admissions 74 , 82 Furthermore, while some findings were mixed and the number of studies limited, 60% of studies found potential for RCL to have protective effects for opioid-related negative consequences. 87 , 88 However, opioid-related findings should be considered in the context of population-level changes in opioid prescriptions and shifting opioid policy influence. 108 Thus, findings may be a result of changes driven by the response to the opioid epidemic rather than RCL, and there remains a need to better disentangle RCL impacts on opioid-related consequences. It is also worth noting that some opioid and cannabis studies are underwritten by the cannabis industry, so the findings should be interpreted with caution due to potential for conflicts of interest. 88 In sum, the overall literature suggests that RCL is associated with both negative and positive health-related consequences and reveals a need to examine the role of RCL across a wide range of health outcomes.

The findings from the driving-related literature do suggest RCL is associated with increased motor vehicle accidents (50% of studies) although the literature was quite evenly split as higher accident rates were not seen across all studies (50% studies). These results point to potential negative consequence associated with RCL and may indicate a need for better measures to prevent driving while under the influence of cannabis in legalized jurisdictions. However, as the evidence was split and predominately in the U.S. additional studies spanning diverse geographical jurisdictions are still needed.

On the other hand, the findings from crime-related outcomes showed some inconsistencies. While one study did suggest minimal decreases for substance-use related arrests in adults, the findings were not consistent across the two studies examining arrest-rates in youth. 100 - 102 These potential decreases in arrest rates for adults can have important implications as cannabis-related crime rates make up a large amount of overall crime statistics and drug-specific arrests. 30 , 31 This discrepancy in youth findings between a U.S. and Canadian study are notable as Canadian RCL policies do include stipulations to allow small scale regulations in youth. Thus, it suggests RCL policies that maintain prohibition of use among underage youth do not address issues related to arrests and crime among youth. In fact, the current literature suggests that cannabis-related charges are still being enforced for youth under the legal age of consumption in the U.S. Another important outcome revealed is racial disparities in cannabis-related arrests. Previous evidence has shown there are racial disparities, particularly between Black, Indigenous, and Hispanic individuals compared to White counterparts, in cannabis-related charges and arrests. 109 , 110 Regarding racial disparities and RCL, there was very little evidence of decreases in disparities for cannabis-related arrests following RCL. 100 , 101 This racialized arresting is significant as it can be associated with additional public health concerns such as physical and mental health outcomes, harm to families involved, and to communities. 111 This finding is particularly concerning as it suggests racialized arrests for cannabis are still occurring despite the intentions of liberalization of cannabis policies to help reduce racial disparities in the criminal justice system. However, it is important to note that there were only 2 studies of racial disparities in cannabis-related arrests and both were conducted in the U.S. Thus, additional research is required before drawing any firm conclusions about the ability of RCL to address systemic issues in the justice system.

Limitations

The findings should be considered within context of the following limitations. The research was predominately from North America (U.S. and Canada). While both countries have either federal or state RCL, findings only from two countries that are geographically connected may not reflect the influence of RCL across different cultures and countries globally. The majority of studies also relied on self-report data for cannabis-related outcomes. Thus, there is a risk that any increases in use or other cannabis-related outcomes may be due to an increased comfort in disclosing cannabis use due to RCL.

Given the large number of studies on multiple outcomes, we chose to focus on implementation of RCL exclusively, rather than related policy changes such as commercialization (ie, the advent of legal sales), to allow for clearer conclusions about the specific impacts on RCL. However, a limitation is that the review does not address the impact of commercialization or changes in product availability. While outside the scope of the current review, it does limit the conclusions that can be drawn about RCL overall as some jurisdictions implemented features of commercialization separately from legalization. For example, in Ontario, Canada, storefronts and edible products became legal a year after initial RCL (when online purchase was the exclusive modality), which may have had an additional impact on behavioral and health-related outcomes. Additionally, the scope of the review was limited to recreational legalization and did not consider other forms of policy changes such as medicinal legalization or decriminalization, as these have been summarized more comprehensively in prior reviews. 112 - 114 Further, this review focused on behavioral and health outcomes; other important outcomes to examine in the future include economic aspects such as cannabis pricing and purchasing behaviors, and product features such as potency. Finally, as this review considered a broad range of outcomes, we did not conduct a meta-analysis which limits conclusions that can be drawn regarding the magnitude of the associations.

Conclusions

The topic of RCL is a contentious and timely issue. With nationwide legalization in multiple countries and liberalizing policies across the U.S., empirical research on the impacts of RCL has dramatically expanded in recent years. This systematic review comprehensively evaluated a variety of outcomes associated with RCL, focusing on longitudinal study designs and revealing a wide variety of findings in terms of substance use, health, cannabis attitudes, crime, and driving outcomes examined thus far. However, the current review highlights that the findings regarding the effects of RCL are highly heterogenous, often inconsistent, and disproportionately focused on certain jurisdictions. With polarizing views surrounding whether RCL is a positive or negative policy change, it is noteworthy that the extant literature does not point to one clear answer at the current time. In general, the collective results do not suggest dramatic changes or negative consequences, but instead suggest that meaningful tectonic shifts are happening for several outcomes that may or may not presage substantive changes in personal and public health risk. Furthermore, it is clear that a more in-depth examinations of negative (eg, frequent use, CUD prevalence, ‘gateway’ relationships with other substance use), or positive consequences (eg, therapeutic benefits for mental health and/or medical conditions, use of safer products and routes of administration), are needed using both quantitative and qualitative approaches.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Funding support from the Peter Boris Chair in Addictions Research and a Canada Research Chair in Translational Addiction Research (JM). Funders had no role in the design or execution of the review.

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: James MacKillop discloses he is a principal and senior scientist in Beam Diagnostics, Inc, and a consultant to ClairvoyantRx. No other authors have disclosures.

Author Contributions: The author’s contribution is as follows: study conceptualization and design: KF, JW, JT, JM; data collection and interpretation: KF, EM, MS; manuscript writing and preparation: KF, EM, MS, PN; manuscript reviewing and editing: JW, JT, JM. All authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 04 February 2020

Marijuana legalization and historical trends in marijuana use among US residents aged 12–25: results from the 1979–2016 National Survey on drug use and health

- Xinguang Chen 1 ,

- Xiangfan Chen 2 &

- Hong Yan 2

BMC Public Health volume 20 , Article number: 156 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

107k Accesses

70 Citations

83 Altmetric

Metrics details

Marijuana is the most commonly used illicit drug in the United States. More and more states legalized medical and recreational marijuana use. Adolescents and emerging adults are at high risk for marijuana use. This ecological study aims to examine historical trends in marijuana use among youth along with marijuana legalization.

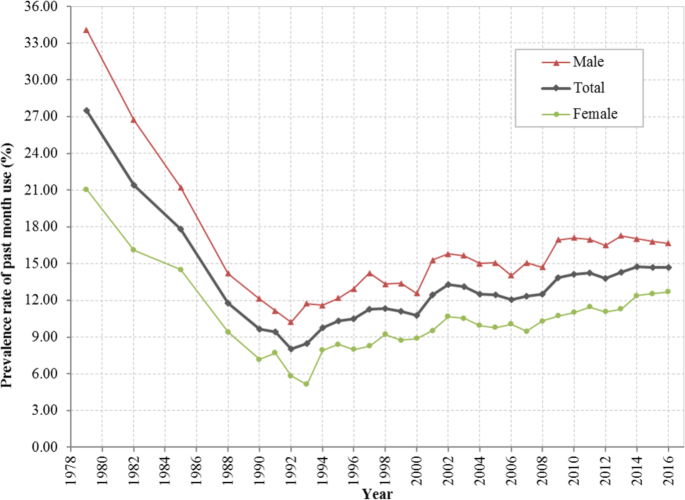

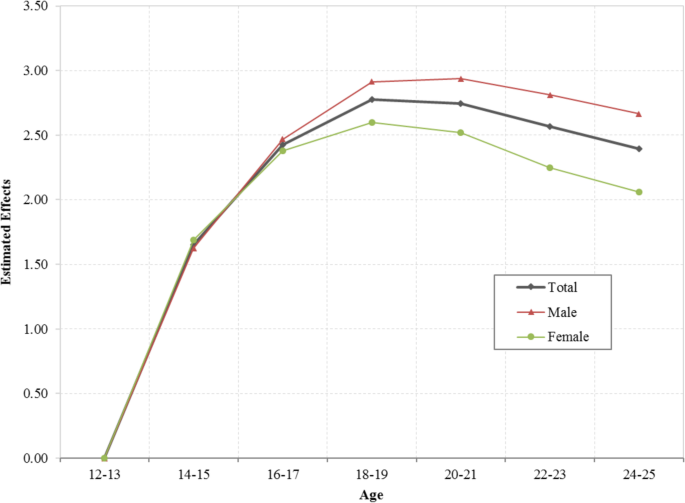

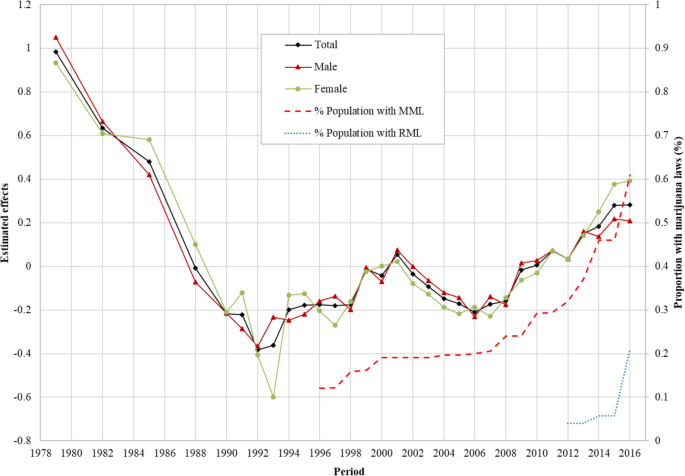

Data ( n = 749,152) were from the 31-wave National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), 1979–2016. Current marijuana use, if use marijuana in the past 30 days, was used as outcome variable. Age was measured as the chronological age self-reported by the participants, period was the year when the survey was conducted, and cohort was estimated as period subtracted age. Rate of current marijuana use was decomposed into independent age, period and cohort effects using the hierarchical age-period-cohort (HAPC) model.

After controlling for age, cohort and other covariates, the estimated period effect indicated declines in marijuana use in 1979–1992 and 2001–2006, and increases in 1992–2001 and 2006–2016. The period effect was positively and significantly associated with the proportion of people covered by Medical Marijuana Laws (MML) (correlation coefficients: 0.89 for total sample, 0.81 for males and 0.93 for females, all three p values < 0.01), but was not significantly associated with the Recreational Marijuana Laws (RML). The estimated cohort effect showed a historical decline in marijuana use in those who were born in 1954–1972, a sudden increase in 1972–1984, followed by a decline in 1984–2003.

The model derived trends in marijuana use were coincident with the laws and regulations on marijuana and other drugs in the United States since the 1950s. With more states legalizing marijuana use in the United States, emphasizing responsible use would be essential to protect youth from using marijuana.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Marijuana use and laws in the united states.

Marijuana is one of the most commonly used drugs in the United States (US) [ 1 ]. In 2015, 8.3% of the US population aged 12 years and older used marijuana in the past month; 16.4% of adolescents aged 12–17 years used in lifetime and 7.0% used in the past month [ 2 ]. The effects of marijuana on a person’s health are mixed. Despite potential benefits (e.g., relieve pain) [ 3 ], using marijuana is associated with a number of adverse effects, particularly among adolescents. Typical adverse effects include impaired short-term memory, cognitive impairment, diminished life satisfaction, and increased risk of using other substances [ 4 ].

Since 1937 when the Marijuana Tax Act was issued, a series of federal laws have been subsequently enacted to regulate marijuana use, including the Boggs Act (1952), Narcotics Control Act (1956), Controlled Substance Act (1970), and Anti-Drug Abuse Act (1986) [ 5 , 6 ]. These laws regulated the sale, possession, use, and cultivation of marijuana [ 6 ]. For example, the Boggs Act increased the punishment of marijuana possession, and the Controlled Substance Act categorized the marijuana into the Schedule I Drugs which have a high potential for abuse, no medical use, and not safe to use without medical supervision [ 5 , 6 ]. These federal laws may have contributed to changes in the historical trend of marijuana use among youth.

Movements to decriminalize and legalize marijuana use

Starting in the late 1960s, marijuana decriminalization became a movement, advocating reformation of federal laws regulating marijuana [ 7 ]. As a result, 11 US states had taken measures to decriminalize marijuana use by reducing the penalty of possession of small amount of marijuana [ 7 ].

The legalization of marijuana started in 1993 when Surgeon General Elder proposed to study marijuana legalization [ 8 ]. California was the first state that passed Medical Marijuana Laws (MML) in 1996 [ 9 ]. After California, more and more states established laws permitting marijuana use for medical and/or recreational purposes. To date, 33 states and the District of Columbia have established MML, including 11 states with recreational marijuana laws (RML) [ 9 ]. Compared with the legalization of marijuana use in the European countries which were more divided that many of them have medical marijuana registered as a treatment option with few having legalized recreational use [ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ], the legalization of marijuana in the US were more mixed with 11 states legalized medical and recreational use consecutively, such as California, Nevada, Washington, etc. These state laws may alter people’s attitudes and behaviors, finally may lead to the increased risk of marijuana use, particularly among young people [ 13 ]. Reported studies indicate that state marijuana laws were associated with increases in acceptance of and accessibility to marijuana, declines in perceived harm, and formation of new norms supporting marijuana use [ 14 ].

Marijuana harm to adolescents and young adults

Adolescents and young adults constitute a large proportion of the US population. Data from the US Census Bureau indicate that approximately 60 million of the US population are in the 12–25 years age range [ 15 ]. These people are vulnerable to drugs, including marijuana [ 16 ]. Marijuana is more prevalent among people in this age range than in other ages [ 17 ]. One well-known factor for explaining the marijuana use among people in this age range is the theory of imbalanced cognitive and physical development [ 4 ]. The delayed brain development of youth reduces their capability to cognitively process social, emotional and incentive events against risk behaviors, such as marijuana use [ 18 ]. Understanding the impact of marijuana laws on marijuana use among this population with a historical perspective is of great legal, social and public health significance.

Inconsistent results regarding the impact of marijuana laws on marijuana use

A number of studies have examined the impact of marijuana laws on marijuana use across the world, but reported inconsistent results [ 13 ]. Some studies reported no association between marijuana laws and marijuana use [ 14 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 ], some reported a protective effect of the laws against marijuana use [ 24 , 26 ], some reported mixed effects [ 27 , 28 ], while some others reported a risk effect that marijuana laws increased marijuana use [ 29 , 30 ]. Despite much information, our review of these reported studies revealed several limitations. First of all, these studies often targeted a short time span, ignoring the long period trend before marijuana legalization. Despite the fact that marijuana laws enact in a specific year, the process of legalization often lasts for several years. Individuals may have already changed their attitudes and behaviors before the year when the law is enacted. Therefore, it may not be valid when comparing marijuana use before and after the year at a single time point when the law is enacted and ignoring the secular historical trend [ 19 , 30 , 31 ]. Second, many studies adapted the difference-in-difference analytical approach designated for analyzing randomized controlled trials. No US state is randomized to legalize the marijuana laws, and no state can be established as controls. Thus, the impact of laws cannot be efficiently detected using this approach. Third, since marijuana legalization is a public process, and the information of marijuana legalization in one state can be easily spread to states without the marijuana laws. The information diffusion cannot be ruled out, reducing the validity of the non-marijuana law states as the controls to compare the between-state differences [ 31 ].

Alternatively, evidence derived based on a historical perspective may provide new information regarding the impact of laws and regulations on marijuana use, including state marijuana laws in the past two decades. Marijuana users may stop using to comply with the laws/regulations, while non-marijuana users may start to use if marijuana is legal. Data from several studies with national data since 1996 demonstrate that attitudes, beliefs, perceptions, and use of marijuana among people in the US were associated with state marijuana laws [ 29 , 32 ].

Age-period-cohort modeling: looking into the past with recent data

To investigate historical trends over a long period, including the time period with no data, we can use the classic age-period-cohort modeling (APC) approach. The APC model can successfully discompose the rate or prevalence of marijuana use into independent age, period and cohort effects [ 33 , 34 ]. Age effect refers to the risk associated with the aging process, including the biological and social accumulation process. Period effect is risk associated with the external environmental events in specific years that exert effect on all age groups, representing the unbiased historical trend of marijuana use which controlling for the influences from age and birth cohort. Cohort effect refers to the risk associated with the specific year of birth. A typical example is that people born in 2011 in Fukushima, Japan may have greater risk of cancer due to the nuclear disaster [ 35 ], so a person aged 80 in 2091 contains the information of cancer risk in 2011 when he/she was born. Similarly, a participant aged 25 in 1979 contains information on the risk of marijuana use 25 years ago in 1954 when that person was born. With this method, we can describe historical trends of marijuana use using information stored by participants in older ages [ 33 ]. The estimated period and cohort effects can be used to present the unbiased historical trend of specific topics, including marijuana use [ 34 , 36 , 37 , 38 ]. Furthermore, the newly established hierarchical APC (HAPC) modeling is capable of analyzing individual-level data to provide more precise measures of historical trends [ 33 ]. The HAPC model has been used in various fields, including social and behavioral science, and public health [ 39 , 40 ].

Several studies have investigated marijuana use with APC modeling method [ 17 , 41 , 42 ]. However, these studies covered only a small portion of the decades with state marijuana legalization [ 17 , 42 ]. For example, the study conducted by Miech and colleagues only covered periods from 1985 to 2009 [ 17 ]. Among these studies, one focused on a longer state marijuana legalization period, but did not provide detailed information regarding the impact of marijuana laws because the survey was every 5 years and researchers used a large 5-year age group which leads to a wide 10-year birth cohort. The averaging of the cohort effects in 10 years could reduce the capability of detecting sensitive changes of marijuana use corresponding to the historical events [ 41 ].

Purpose of the study

In this study, we examined the historical trends in marijuana use among youth using HAPC modeling to obtain the period and cohort effects. These two effects provide unbiased and independent information to characterize historical trends in marijuana use after controlling for age and other covariates. We conceptually linked the model-derived time trends to both federal and state laws/regulations regarding marijuana and other drug use in 1954–2016. The ultimate goal is to provide evidence informing federal and state legislation and public health decision-making to promote responsible marijuana use and to protect young people from marijuana use-related adverse consequences.

Materials and methods

Data sources and study population.

Data were derived from 31 waves of National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), 1979–2016. NSDUH is a multi-year cross-sectional survey program sponsored by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The survey was conducted every 3 years before 1990, and annually thereafter. The aim is to provide data on the use of tobacco, alcohol, illicit drug and mental health among the US population.