Adolescent Reproductive Health

Sep 14, 2014

850 likes | 1.88k Views

Adolescent Reproductive Health. Presented by: Dr. Richard O. Muga (MBS) National Co-ordinating Agency for Population and Development, Nairobi-Kenya. Seminar for African Journalist held at Hilton Hotel, Nairobi-Kenya on 15-18 th June 2006. STI’s and HIV/AIDS.

Share Presentation

- sexually active

- family planning

- reproductive health information

- men young men start

Presentation Transcript

Adolescent Reproductive Health Presented by: Dr. Richard O. Muga (MBS) National Co-ordinating Agency for Population and Development, Nairobi-Kenya Seminar for African Journalist held at Hilton Hotel, Nairobi-Kenya on 15-18th June 2006.

STI’s and HIV/AIDS • World Wide: 111 million of 333 million new cases of STI’s occur to people under age 25 years • Kenya: Among those tested for HIV/AIDS 3% (711) and 0.4% (745) of women and men aged 15-19 years respectively have been infected with HIV/AIDS

CURRENT SITUATION OF ADOLESCENTS

Outline of the presentation • Adolescent sexual experience • STIs and HIV/AIDS • Contraceptive use • Female genital cutting • Pregnancy and child bearing • Unsafe Abortions • What can we do?

Introduction • Adolescents are those aged 10-19 years • Globally, those aged 10-19 years are estimated at 1.2 billion • Most men and women become sexually active during adolescence • Adolescents reproductive health decisions outcomes are highly devastating • Adolescents face several barriers such as social norms and cultural taboos about young people’s sexuality

Sexual Behavior among Youth • Women: almosthalf of young women have sex by the time they turn 18. And more than one in ten (13%) have sex by the time they are 15. • Men: Young men start having sex at an earlier age. Sixty percent had sex by age 18, and a quarter had sex by age 15. • Sub-Saharan Africa: 30% of unmarried women (15-19 years) have had sex

Outcomes of sexual behaviour • 70% of adolescents in Kenya engage in high risk unprotected sex • STI’s, HIV/AIDS • Increased risks of unwanted pregnancies • Unsafe abortions resulting into severe illness • Complications during abortions causing infertility and deaths

Premarital Sex and Condom Use Percent

Teen Pregnancy and Motherhood Percent of women age 15-19 who are mothers or pregnant with their first child. Eastern 15% North Eastern 29% Rift Valley 31% Western 27% Central 15% Kenya: 23% Nyanza 21% • World wide it is estimated that 15 million women aged 15-19 give birth every year Coast 29% Nairobi 20%

Risks of Early Child bearing • Less education hence lower future income for young mothers • Social rejection by community • Obstructed labour resulting into permanent injury or death for mother and infant • Premature and low birth weight deliveries

Unsafe Abortions • Unsafe abortions have serious health risks • Globally, 2.5 million unsafe abortions occur among adolescent girls aged 15-19 years • Pregnancy related abortions and child birth are leading cause of deaths to adolescents aged 15-19 years • Kenya, 4 in every 10 women who die from unsafe abortions are adolescents

Contraceptive Use • Contraceptive use among the adolescents is very low • Sub-Saharan Africa 35% of unmarried sexually active women use modern contraception • Kenya: only 5% of sexually active adolescents use modern contraceptive methods

Current Use of Family Planning Percent women (age 15-24) using a family planning method Age • Sub-Saharan Africa: 35% of unmarried sexually active women (15-19 years) use modern contraception

Female Genital Cutting • Between 100 million and 180 million women world wide have undergone FGC practice • Every day some 600 girls world wide are at risk of undergoing FGC • Kenya, 20% of women aged 15-19 years have undergone FGC • The practice of FGC is currently outlawed in Kenya under the children’s Act of 2001

Female Genital Cutting • Female Genital Cutting have serious consequences on women: • Infections, pain and bleeding which can lead to shock and possibly death • Prolonged and obstructed labour • Fistula • Inability to enjoy sexual rights

What can be done? • Provide sexual and reproductive health information and services to adolescents • Put in place proper Legislation • Support multi-sectoral programmes • Provide health education to adolescents such as responsible sexual behaviour, HIV/AIDS, sexuality, family planning

What can be done? • Encourage parents to actively involve themselves in adolescent reproductive health issues • Train more peer educators to reach out the adolescents • Provide integrated health services to adolescents such as family planning information and services

What Can Be Done? • Establish adolescent-friendly services • Ensure adolescent-friendly services have high quality information necessary for informed consent • Increase opportunities for women’s education and employment • Encourage alternative rites of passage

Global Appeal • Adolescents today are increasingly facing more reproductive health challenges than ever before • More efforts is needed by all actors to address adolescents reproductive health issues • Invest in the young people today to assure tomorrow

Who we Are • NCAPD is a SAGA established through legal notice no. 120 of 29th October 2004 • Provide leadership in Population and development matters • Assess multi-sectoral population issues and support stakeholders • Advocate for Political and other support to address population issues

Who we are Mission: To provide leadership in Formulating, Coordinating and implementing Population Policies and Programmes for Sustainable Development Vision: To be an institution of excellence in Population Policy formulation and Management Contact: Chancery Building, 4th Floor, Valley Road P.O BOX 48994-00100 Nairobi, Kenya. Tel:+254-20-2711600/1 +254-20-2711711 Fax: +254-20-2716508 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ncapd-ke.org

- More by User

A Future with Promise: Latino Adolescent Reproductive Health

A Future with Promise: Latino Adolescent Reproductive Health A Future with Promise: A Chartbook on Latino Adolescent Reproductive Health Anne Driscoll, DrPH Claire Brindis, DrPh M. Antonia Biggs, PhD L. Teresa Valderrama, MPH Center for Reproductive Health Research and Policy,

2.28k views • 189 slides

Adolescent and youth reproductive health

Adolescent and youth reproductive health . Issues, Programmes & Operational barriers. Authors: Aparnaa Somanathan, Vindya Eriyagama, Ruwanthi Elwalagedara. Health Policy research Associates http://www.hpra.lk. Key questions.

1.16k views • 23 slides

Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health Globally

Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health Globally. Shifting the Paradigm. Robert Wm. Blum, M.D., M.P.H., Ph.D. Professor, Director, WHO Collaborating Centre Division of General Pediatrics & Adolescent Health University of Minnesota. Prepared for Tulane University School of Public Health

853 views • 60 slides

The Physician as Advocate for Adolescent Reproductive Health

The Physician as Advocate for Adolescent Reproductive Health. Adolescents Need Physicians to Advocate on Their Behalf. Adolescents Need Physicians to Advocate on Their Behalf. Adolescence is a unique time in life requiring special attention Characterized by:

498 views • 49 slides

The Importance of Addressing Adolescent Reproductive Health Issues

The Importance of Addressing Adolescent Reproductive Health Issues. Barthélemy Kuate Defo, PhD, MPH Professeur Titulaire, Université de Montréal Professeur-Chercheur, Centre de Recherche du CHUM

428 views • 20 slides

Physicians as Advocates for Adolescent Reproductive Health

Physicians as Advocates for Adolescent Reproductive Health. Adolescents Need Physicians to Advocate on Their Behalf. Adolescents Need Physicians to Advocate on Their Behalf. Adolescence is a unique time in life requiring special attention Characterized by:

570 views • 49 slides

Male Adolescent Reproductive and Sexual Health

Male Adolescent Reproductive and Sexual Health. Objectives. By the end of this presentation participants will be able to:. Identify. Elements of male friendly health services. Take. A comprehensive, male-focused sexual health history. Perform . A male genital exam.

1.29k views • 102 slides

Adolescent Reproductive and Sexual Health Data

Adolescent Reproductive and Sexual Health Data. Objectives. By the end of this presentation, participants will be able to: Discuss trends in adolescent sexuality and reproductive health Characterize patterns in adolescent contraceptive use

799 views • 58 slides

Adolescent Reproductive Health Data

Adolescent Reproductive Health Data. Objectives. By the end of this presentation, participants will be able to: Discuss trends in adolescent sexuality and reproductive health Characterize patterns in adolescent contraceptive use

869 views • 57 slides

Male Adolescent Reproductive Health

Male Adolescent Reproductive Health. Objectives. By the end of this presentation participants will be able to:. Male Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. Adolescence Is a Time of Major Changes. Physical, emotional, and developmental changes Emerging sexuality

1.67k views • 99 slides

Adolescent Reproductive Health Policy: Progress and Problems

Adolescent Reproductive Health Policy: Progress and Problems. James Rosen October 15, 2001. Adolescent Reproductive Health: Why Care?. 1.7 billion youth ages 10 to 24 13 million births to adolescent girls half of new HIV infections to youth. What is ARH Policy?.

1.02k views • 34 slides

Positioning Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health in the health agenda

Positioning Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health in the health agenda. Pacific Society for Reproductive Health. Rufina Latu 9 th July, Apia, Samoa WHO , Port Vila, Vanuatu. Adolescent healt h – integral part of R/health cycle. Adolescents and MDGs. What do the statistics show?

304 views • 12 slides

Male Adolescent Reproductive Health. Outline. Adolescent Male Demographics Sexuality and Contraceptive Use Healthcare Access for Males Male Adolescent-Friendly Health Services The Male Adolescent Sexual History and Physical Exam. Objectives.

1.38k views • 70 slides

ADOLESCENT SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH

ADOLESCENT SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH. Adolescent sexual and reproductive health. Adolescents are young people between the ages of 10 and 19. Adolescent sexual and reproductive health refers to the physical, mental, and emotional well being of adolescents, and includes freedom from:

691 views • 9 slides

Reproductive Health of Adolescent Girls: Perspectives from WDR07

Reproductive Health of Adolescent Girls: Perspectives from WDR07. Emmanuel Jimenez December 1, 2009. www.worldbank.org/wdr2007. Motivation. Investing in in the human capital of young people (12-24 years) is key to development:

401 views • 23 slides

Adolescent Reproductive Health Data. Objectives. By the end of this presentation, participants will be able to: Discuss trends in adolescent sexuality and reproductive health. Characterize patterns in adolescent contraceptive use.

1.73k views • 65 slides

Human Rights and Adolescent Reproductive Health (ARH)

Human Rights and Adolescent Reproductive Health (ARH). By the Human Rights and Adolescent RH Working Groups of the POLICY Project 2002. Adolescents are defined by POLICY as people between the ages of 10 and 24 years old. Why should we care about adolescents’ right to health?.

629 views • 14 slides

Adolescent Reproductive Health Working Group

Adolescent Reproductive Health Working Group. IAWG 8-10 October 2007 Nairobi, Kenya. 4.1 Advocate for better youth Programming. Policy Development – work with Government to develop an ARH policy Kenya established an Adolescent RH policy in May 2003 through efforts of Civil society actors

263 views • 7 slides

USAID/Dhaka’s Adolescent Reproductive Health Program

USAID/Dhaka’s Adolescent Reproductive Health Program. A Brief Overview!. Adolescent Profile. Adolescents (10-19) -- 22 percent of population (28 million) Average age of marriage 15 Average age of first birth 17 (ARH 2002 Baseline)

381 views • 21 slides

The Physician as Advocate for Adolescent Reproductive Health. Outline. The Need: Why Adolescents Need Physicians to Advocate on Their Behalf Advocacy on 4 Levels: Which Is Right for You? Practice Community Media Legislative and Policy. Adolescence.

816 views • 62 slides

240 views • 20 slides

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Adolescents and reproductive health

Related Papers

Reproductive Biomedicine Online

Mopo Radebe

Journal of Adolescent Health

Sebastian Emans

Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences

Monalisha Jena

Danielle Engel

American Academy of Pediatrics eBooks

Abigail English

Dr. Saradindu Bera

The World Health Organization defines adolescence as the period of life between ages 10 and 19 years. Adolescence is a stage of development transition, i.e., bridge between childhood and adulthood. The reproductive health is inextricably linked to the subject of reproductive rights and freedom also it extends beyond the narrow confines of family planning to encompass all aspects of human sexuality and reproductive health needs during the various stages of the life cycle. Adolescents are an important resource of any country. This is the stage when physical and sexual changes are taking place in their development. On this way they may face troubles due to lack of right kind of information regarding their own physical and sexual development. Going through physical and sexual development, many adolescents become sexually active increasingly at early ages. Their vulnerability and ignorance on matters related to their reproductive health, their inadequate knowledge on contraception and inability and unwillingness to use family planning and health services leads adolescents to face reproductive morbidity and mortality. It is feared that adolescent girls as well as boys if not duly informed find themselves at risk of pregnancy, child bearing and getting infected by

Gladys Canaval

Objectives: 1- To explore ideas and attitudes regarding, the use of contraceptive methods by adolescents from two “comunas” in the city Cali. 2- To determine factors that hinders the practice of contraceptive methods. Methodology: Focal groups of pregnant adolescents and their partners and adolescent not pregnant and their male friends from Cali city were studied. Results: It was found that the lack of kwowlegde, the life project, responsibility and fear were issues considered in the results. The model PRECEDE-PROCEDE for organizing the data was utilized. Discussion: Sexuality still is a taboo theme deserving awareness it in the public agenda. Lack of knowledge and negative attitudes are obstacles for using contraceptives. This has been reported also by other authors. Maternity is considered by women as a source of life fulfillment. It is important to stress that maternity is not alone for the woman and that it should involve the partner as well. Conclusions: Young people need to ov...

IJRASET Publication

The article provides theoretical views on reproductive health, especially women's health. Preserving the reproductive health of young people and optimizing their reproductive behavior by developing principles for preventing unwanted pregnancies and introducing a set of measures aimed at preventing complications of abortions, subsequent pregnancies and childbirth, and preventing repeated abortions.

Indian Journal of Youth and Adolescent Health

Kaushalendra Kumar Singh , UJJAVAL SRIVASTAVA

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Maria Elena Burbano

Poul Sørensen

Glauber Tiburtino

European History Quarterly

Emmet O'Connor

Gabriel Asprella

Saleema Gulzar

Gestión y Análisis de Políticas Públicas

Juan Carlos Herrero Murciano

Pantelis Pantelidis

Teoria e Pesquisa

Sonia Terron

Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria

Fabiana Lopes

Journal of the American College of Cardiology

Tuan Nguyen

Collaboration in International and Comparative Librarianship

Dr Achala Munigal

B. Tjeerdsma

Leonardo Zelmar Juarez Chavez

Ensaio: Avaliação e Políticas Públicas em Educação

Carlos Frederico Bernardo Loureiro

Sergio Negrete Cárdenas

Case Reports in Otolaryngology

Stefan Dorin ursachescu

Jordanian Journal of Law and Political Science

mosleh tarawneh

Terbiye-i İrade (Özgün Metin)

Ömer Faruk Can

Gerwin Schalk

Alan Friedlander

Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials

Lars Nordström

Journal of Mining and Environment

Mohammad Fatehi Marji

See More Documents Like This

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- My presentations

Auth with social network:

Download presentation

We think you have liked this presentation. If you wish to download it, please recommend it to your friends in any social system. Share buttons are a little bit lower. Thank you!

Presentation is loading. Please wait.

ADOLESCENT SEXUAL REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH

Published by Jocelin Roberts Modified over 5 years ago

Similar presentations

Presentation on theme: "ADOLESCENT SEXUAL REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH"— Presentation transcript:

1 ADOLESCENTSEXUALITY. 2 Definitions In 1989, the joint WHO/UNFPA/UNICEF Statement gave the following definitions: Adolescents:10-19 year olds; Youth:15-24.

GAP Report 2014 People with disabilities People left behind: People with disabilities Link with the pdf, People with disabilities.

Reducing inequalities: Enhancing young people’s access to SRHR Consultative meeting with African Parliamentarians on ICPD and MDGs September 2012 Sharon.

Links between youth employment, education and sexual reproductive health Dr. Frank Anthony Minister of Culture, Youth and Sport.

1 Global AIDS Epidemic The first AIDS case was diagnosed in years later, 20 million people are dead and 37.8 million people (range: 34.6–42.3 million)

© Aahung 2004 Millennium Development Goals Expanding the Agenda:

What are some serious issues that teenagers face today?

REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH ISSUES IN PAKISTAN

GAP Report 2014 People left behind: Adolescent girls and young women Link with the pdf, Adolescent girls and young women.

Introduction to adolescence & to adolescent health WHO Department of Child and Adolescent Health and Development Introduction to adolescence & to adolescent.

ADOLESCENT SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH. adolescent sexual and reproductive health ( 2 ) Adolescents are young people between the ages of 10 and 19.

1 Adolescent Reproductive Health Presented by: Dr. Richard O. Muga (MBS) National Co-ordinating Agency for Population and Development, Nairobi- Kenya Seminar.

1 Investing in the future: Addressing challenges faced by Africa's young population. 40 th Session of the Commission on Population and Development Nyovani.

INTRODUCTION. MODULE 1: ADOLESCENCE EDUCATION IN INDIA.

Definition of reproductive health (from ICPD, 1994)

Kenya’s Youth Today From the 2003 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey.

Global Awareness Program Women’s Health. What sets women’s health apart from men’s? Two big themes: 1)Women generally need more health care than men because.

UNWANTED PREGNANCY.

Part 2 Gender and HIV/AIDS HIV/AIDS IS A GENDER ISSUE BECAUSE: I Although HIV effects both men and women, women are more vulnerable because of biological,

About project

© 2024 SlidePlayer.com Inc. All rights reserved.

Adolescent sexual and reproductive health

Resource date: Nov 2014

Author: UNFPA

For millions of young people around the world, the onset of adolescence brings not only changes to their bodies but also new vulnerabilities to human rights abuses, particularly in the arenas of sexuality, marriage and childbearing.

Millions of girls are coerced into unwanted sex or marriage , putting them at risk of unwanted pregnancies, unsafe abortions, sexually transmitted infections (STIs) including HIV , and dangerous childbirth. Adolescent boys are at risk, as well. Young people – both boys and girls – are disproportionately affected by HIV.

Yet too many young people face barriers to reproductive health information and care. Even those able to find accurate information about their health and rights may be unable to access the services needed to protect their health.

Supporting adolescents’ health and rights

Adolescents’ sexual and reproductive health must be supported. This means providing access to comprehensive sexuality education ; services to prevent, diagnose and treat STIs; and counselling on family planning . It also means empowering young people to know and exercise their rights – including the right to delay marriage and the right to refuse unwanted sexual advances.

UNFPA partners with other UN agencies and with governments, civil society, young people and youth-serving organizations to actively promote and protect the sexual and reproductive health and human rights of adolescents.

Youth-friendly services

Working with ministries, NGOs and other partners, UNFPA also advocates for and supports the efficient delivery of a holistic, youth-friendly health-care package of services. These include:

- Universal access to accurate sexual and reproductive health information;

- A range of safe and affordable contraceptive methods;

- Sensitive counselling

- Quality obstetric and antenatal care for all pregnant women and girls; and

- The prevention and management of sexually transmitted infections, including HIV

UNFPA also works to ensure health services and supportive programmes are available to young people who are marginalized or hard to reach.

Selected links

The Rights to Contraceptive Information and Services for Women and Adolescents Making health services adolescent friendly Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health Toolkit for Humanitarian Situations Adolescent pregnancy Family planning

We use cookies and other identifiers to help improve your online experience. By using our website you agree to this, see our cookie policy

Adolescent and Youth Reproductive Health Module: 12. Promoting Adolescent and Youth Reproductive Health

Study session 12 promoting adolescent and youth reproductive health, introduction.

Successful implementation of adolescent and youth reproductive health services and programmes requires the full support of young people, parents, community leaders and other influential community members in your kebele . To get the support of the community including young people, you need to promote adolescent and youth reproductive health (AYRH) using a variety of promotion methods. The same health promotion principles that you learned in the Health Education , Advocacy and Community Mobilisation and other Modules apply in promoting adolescent and youth reproductive health. In this session you will learn the best methods to use to promote adolescent and youth reproductive health.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 12

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

12.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold . (SAQ 12.1)

12.2 Explain the importance of promoting adolescent and youth reproductive health. (SAQ 12.1)

12.3 Describe the different methods of promoting adolescent and youth reproductive health including community conversation, youth clubs/group discussion, peer education and age appropriate family life education. (SAQ 12.2)

12.4 Identify the health promotion strategies and actions appropriate for different age groups of young people. (SAQ 12.2)

12.1 Promoting adolescent and youth reproductive health

In Study Sessions 1 and 2 you learned that young people are especially at risk of multiple health and social problems, mainly arising from their risky behaviours. Young people can be influenced to have positive healthy behaviour provided they get sufficient support from their families, health workers and communities. Studies conducted in the years 2005 to 2006 showed that only 15% of young people living in rural areas were enrolled in secondary school and that youth reproductive health programmes in Ethiopia tend to only reach older, unmarried, urban boys who are in school. So the most vulnerable members of the population, namely rural youth (86 %), married girls and out-of-school adolescents were missed by these programme efforts. So in this Module emphasis will be given to the importance of targeting vulnerable groups of young people to get the best results from your limited resources.

Health Promotion is the process of enabling people to increase control over and to improve their health, which includes sexual and reproductive health. Young people need interventions to decrease and to alleviate their vulnerability. These include information and skills, a safe and supportive environment and appropriate and accessible health and counselling services.

Health promotion could be conducted in various settings such as schools and in the community and at health posts. In all situations, it is important to keep in mind that different groups of young people need different approaches and messages depending on their age, living and family arrangements, and school status. In the following paragraphs you will understand the specific issues that you need to address, separately, for young people aged 10–14, 15–19 and 20–24 years, orphans and other vulnerable children.

12.2 Health promotion in schools

An effective school health programme is one of the strategic means used to address important health risks among young people and to engage the education sector in efforts to change the educational, social and economic conditions that put adolescents at risk.

As the number of young adolescents being enrolled in schools is increasing all the time, school-based sexual and reproductive health (SRH) education is becoming one of the most important ways to help adolescents recognise and prevent risks and improve their reproductive health (Figure 12.1).

Studies show that school-based reproductive health education is linked with better health and reproductive health outcomes, including delayed sexual initiation, a lower frequency of sexual intercourse, fewer sexual partners and increased contraceptive use. Many programmes have had positive effects on the factors that determine risky sexual behaviours, by increasing awareness of risk and knowledge about STIs and pregnancy, values and attitudes toward sexual topics, self-efficacy (negotiating condom use or refusing unwanted sex) and intentions to abstain or restrict the number of sexual partners (Figure 12.2).

Box 12.1 elaborates the main objectives of skills-based education in schools.

Box 12.1 Objectives of skills-based health education in schools

- Prevent/reduce the number of unwanted, high-risk pregnancies

- Prevent/reduce risky behaviours and improve knowledge, attitudes and skills for prevention of STIs including HIV

- Prevent sexual harassment, gender-based violence and aggressive behaviour

- Reduce drop-out rates in girls’ education due to pregnancy

- Promote girls’ right to education.

12.3 Peer education programme

Peer education is the process whereby well-trained and motivated young people undertake informal or organised educational activities with their peers (those similar to themselves in age, background, or interests). A peer is a person who belongs to the same social group as another person or group. The social group may be based on age, sex, occupation, socio-economic or health status, and other factors.

Peer education is an effective way of learning different skills to improve young people’s reproductive and sexual health outcomes by providing knowledge, skills, and beliefs required to lead healthy lives. Peer education works as long as it is participatory and involves young people in discussions and activities to educate and share information and experiences with each other. (Figure 12.3) It creates a relaxed environment for young people to ask questions on taboo subjects without the fear of being judged and/or teased.

What is a taboo subject?

Taboo refers to strong social prohibition (or ban) relating to human activity or social custom based on moral judgement and religious beliefs. In most of our communities openly talking about sex is considered unacceptable.

The major goal of peer education is to equip young people with basic but comprehensive sexual and reproductive health information and skills vital to engage in healthy behaviours.

Several areas of adolescent and youth reproductive health such as STIs (including HIV and its progress to full-blown AIDS), life skills, gender, vulnerabilities and peer counselling could be addressed in peer education. Although peer education is mainly aimed at achieving change at the individual level by attempting to modify the young person’s knowledge, attitudes, beliefs or behaviours, it can also effect change at a group or social level by modifying existing norms and stimulating collective action.

Box 12.2 Advantages of peer education for young people

- Peer education helps the young person to obtain clear information about sensitive issues such as sexual behaviour, reproductive health, STIs including HIV

- It breaks cultural norms and taboos

- It is combined with training that is user friendly and offers opportunities to discuss concerns between equals in a relaxed environment

- Peer education training is participatory and rich in activities that are entertaining while providing reliable information

- Training in peer education offers the opportunity to ask any questions on taboo subjects and discuss them without fear of being judged and labelled

- Peer education as a youth-adult partnership: peer education, when done well, is an excellent example of a youth-adult partnership. Increased youth participation can help lead to outcomes such as improved knowledge, attitudes, skills and behaviours.

Peer education can take place in small groups or through individual contact and in a variety of settings: schools, clubs, churches, mosques, workplaces, street settings, shelters, or wherever young people gather. You will know from your own experience that young people get a great deal of information from their peers on issues that are especially sensitive or culturally taboo. Often this information is inaccurate and can have a negative effect. Peer education makes use of peer influence in a positive way.

As a health worker closely working with the community, you might be asked to give training on peer education to young people. However, before you are asked to train peer educators, you are likely to receive short-term training on how to train young people to be effective peer educators. Therefore, in this study session you will study only some basic tips that will help you in training adolescents to be peer educators. Firstly, young people, like adults, have a tendency to mask how much they don’t know about a subject. Hence, you should not assume the topic is understood because there are no questions; ask questions of the participants when they do not offer their own. Secondly, young people and adults learn better if they are neither criticised nor judged by the facilitator. It is important to keep a positive attitude. Young people will learn better in an atmosphere of support, trust and understanding.

These basic tips will also be useful to the young people who you have trained to be peer educators. They will also want to know whether they should organise some activities or just be available to talk to peers, e.g. at school, work or in a bar.

After taking the training, a good peer educator should have the following qualities.

- Ability to help young people identify their concerns and seek solutions through mutual sharing of information and experience.

- Ability to inspire young people to adopt health seeking behaviours by sharing common experiences, weaknesses, and strengths.

- Become a role model; a peer educator should demonstrate behaviours that promote risk reduction within the community in addition to informing about risk reduction practices.

- Understand and relate to the emotions, feelings, thoughts and “language” of young people.

Examples of youth peer education activities include organised sessions with students in a secondary school, where peer educators might use interactive techniques such as role plays or stories, and a theatre play in a youth club, followed by group discussions. Theatre play in this sense doesn’t mean that peer educators should be properly trained artists. It only refers to short dramas which are based on real-life experiences that young people are likely to face in their day-to-day life. Peer educators are also expected to use informal conversations with friends, where they might talk about different types of behaviour that could put their health at risk and where they can find more information and practical help.

12.4 Family life education

Family life education is defined by the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF) as ‘an educational process designed to assist young people in their physical, emotional and moral development as they prepare for adulthood, marriage, parenthood, and ageing, as well as their social relationships in the socio-cultural context of the family and society’. An effective family life education helps young people to finish their education and reach adulthood without early pregnancy by delaying initiation of sexual activity until they are physically, socially and emotionally mature and know how to avoid risking infection by HIV and other STIs.

Educating adolescents in schools can lay the groundwork for a lifetime of healthy habits; since it is often more difficult to change established habits than it is to create good habits initially.

Important family life education content includes understanding oneself and others; building self-esteem; forming, maintaining, and ending relationships; taking responsibility for one's actions; understanding family roles and responsibilities; and improving communication skills.

Note from the above descriptions that family life education has many things in common with life skills (see Study Session 2 of this Module).

Traditionally adolescents get very limited information on reproductive health topics such as physiology, reproduction cycle, and life skills. Currently in Ethiopia, Family Life Education (FLE) is being taught to adolescents in primary school (from grade 7 onwards) integrated in the natural and social sciences, with reproductive health issues mainly incorporated in biology.

12.5 Community Conversation

Community conversation is a process whereby members of the different communities come together, hold discussions on their concerns and by using their own values and capacity reach shared resolutions for change and then implement them (Figure 12.4).

As you learned in the Study Sessions on HIV/AIDS in the Communicable Diseases Module and in the Health E ducation , Advocacy and Community Mobilisation Modules, the day-to-day activities of community conversation are handled by you working closely with the kebele health committee. It is important to use the opportunity of meeting the community in the quarterly meetings for HIV/AIDS and other diseases so that you can raise the community’s awareness about adolescent and youth reproductive health issues.

In the following sections you will learn the specific health promotion activities that you need to undertake for young people of different age groups.

12.6 Girls and boys aged 10–14 years living with their parents

Young people in early adolescence (aged 10–14 years) who live with their parents are often forced into early marriage, and suffer its consequences including early pregnancy leading to child birth complications such as fistula. They could also suffer sexual violence including female genital mutilation (FGM), abduction, polygamy and rape which predisposes them to STIs/HIV/AIDS. Because of lack of economic resources and unequal power relations with spouses girls are often unable to negotiate condom use with older spouses.

The fact that they have poor health seeking behaviour with limited access to antenatal or postnatal care and skilled delivery contributes to the high maternal mortality in this age group.

Boys are particularly at risk of dropping out of school to work. Those who migrate to urban areas are likely to live on the street.

Box 12.3 shows the main activities that you are expected to undertake on behalf of young people in early adolescence (aged10–14 years).

Box 12.3 Key actions for young people aged 10–14 years who are living their parents

- Sensitise community leaders, religious leaders, kebele officials and parliamentarians on SRH so that they will advocate on behalf of 10–14 year olds having access to appropriate information and services

- Select and train mentors and educators from the community

- Train peer educators from this age group (equal number of boys and girls) on SRH to disseminate advice on SRH and provide non-prescriptive contraceptives in clubs and other venues

- Provide age appropriate family life education in clubs and other venues where this group gather

- Awareness creation/sensitisation on the new family law which sets the minimum age of marriage at 18 years for both males and females

- Monitor and follow up implementation of SRH at the community level

- Provide training on gender and its effects on the reproductive health of young people

- Provide technical and material support to parent and teachers associations (PTAs).

- Provide technical and material support to create “safe spaces” for child brides

- Provide SRH training and family life education, negotiation and assertiveness skills for girls aged 10–14 years who are about to be married or who have already married

- Provide trained community volunteers to seek out child brides and persuade them to come to health facilities for antenatal, postnatal and delivery care.

You can use the following strategies to accomplish the activities indicated in Box 12.3:

- Create parent-teacher associations (PTAs) in schools and within the kebele committee as advocates and to follow up on enrollment and retention rates of female and male students.

- Advocate against early marriage, gender based violence and other HTPs.

- Create safe places (church, mosque, kebele ) where groups meet, support each other, exchange information and receive sexual and reproductive health information and services.

- Promote antenatal, postnatal and skilled delivery services to this age group.

- Encourage and provide incentives to bring married girls and boys who have dropped out of school back to school.

- Encourage making schools gender sensitive (i.e. separate toilets for girls and boys, reduce harassment of girls on the road to schools).

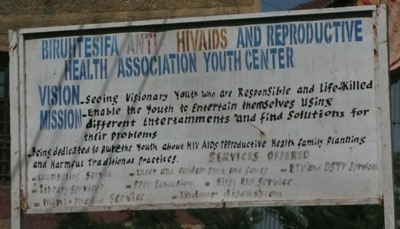

- Organise Reproductive health/HIV/AIDS clubs in-school and out-of-school. (Figure 12.5)

12.7 Girls and boys aged 15–19 years

Many in this group will be married or in a sexual relationship (remember average age at first marriage is 16 years for Ethiopian women even though marriage under 18 years is illegal). The reproductive health risks that girls in this age range are likely to encounter include sexual harassment, rape, abduction, FGM and polygamy. They are also at risk of dropping out of school because of poor performance due to work load and lack of support.

This group of late adolescents are more likely than the early adolescents to be married and to experience unwanted pregnancy, unsafe abortion, STI/HIV/AIDS. They may migrate to urban areas hoping for a better life but ending up as prostitutes (girls) and/or living on the streets (mostly boys but also girls).

What are key actions that you should undertake for this 15–19 years age group?

The key actions used for adolescents aged 10–14 years also apply to this group (see Box 12.3). In addition you need to provide youth friendly services that these adolescents can access for themselves at community level and at your health post (Figure 12.6). It may also be necessary to provide parents with communication skills and to sensitise them on the sexual and reproductive health of adolescents.

You should continue to advocate for the minimisation and eradication of sexual violence and harmful traditional practices using community conversations and dialogues; create referral linkages between schools and health facilities and outreach services, organise youth (in school and out of school) RH/HIV/AIDS clubs, gender clubs, and provide contraceptives in places where young people gather.

12.8 Young people aged 20–24 years

Important reproductive health concerns among these young people include; gender based violence, (rape, abduction), unwanted pregnancy, abortion, and sex in exchange for money or gifts. Because of this they are at risk of STIs including HIV, and of developing AIDS. Unemployment is also another significant issue that worries young people in this age group.

The key actions outlined in Box 12.3 also apply to this group. Particularly, you need to focus on training peer educators and sensitising community members to the needs for SRH services to young people whether they are married or not.

In general most strategies listed above apply to all age groups; the following are issues where you need to give greater emphasis for this older age group:

- Provide youth friendly services in vocational training schools and workplaces, and where these group congregate, ensuring you can provide an adequate supply of contraceptives

- Peer education on SRH

- Strengthen referral networks among health providers and young people.

12.9 Orphans and other vulnerable adolescents aged 10–19 years

Which groups of young people are especially vulnerable to having reproductive health problems?

As you have learned in Study Session 1, orphans, young married girls in rural areas, and youths who are abused, trafficked, physically or mentally impaired or migrate to urban areas are most vulnerable to negative reproductive health outcomes. More often they lack parental support and the financial resources to sustain on the streets and to acquiring STIs including HIV which eventually causes the themselves which predisposes them to engaging in prostitution (Figure 12.7), living development of AIDS.

It is important to keep in mind that the key actions listed above apply to these groups as well. Most of the strategies to implement the activities are also similar. Of particular importance is the need to create a safe place where they can meet to support each other and obtain RH information and services. You need to select and train individuals from the group to serve as peer educators and train community volunteers to seek out and provide them with information and services, and create a network of referrals.

Summary of the Study Session 12

In Study Session 12, you have learned that:

- Adolescent and youth reproductive health promotion needs to receive proper attention in order to protect young people from adopting risky behaviours that could negatively affect their health.

- There are a variety of ways to conduct health promotion for adolescents including school education, peer education, community conversation, and family life education. You can do promotion activities in schools, the community and at your health post.

- The kind of health promotion messages appropriate for adolescents depend on their age, living arrangements and whether they are in school or out-of school.

- Peer education is one of the effective strategies used to improve young people’s reproductive and sexual health outcomes by providing the knowledge, skills and beliefs necessary to lead healthy lives.

- Adolescent family life education is an effective adolescent health promotion strategy. It provides knowledge on physical, mental, social, moral, behavioural and mood changes and developments during puberty.

- Community conversation is also one the key strategies that should be used to raise the community’s awareness and to bring about positive behaviours among adolescents and young people.

- Young adolescents (10–14) who live with their parents may have reproductive health problems such as early marriage and pregnancy leading to difficult child birth with later complications such as obstetric fistula. They may also experience sexual violence (including FGM, abduction, polygamy and rape).

- Adolescents in the age group 15–19 years face similar reproductive health risks such as sexual harassment, rape, abduction, FGM and polygamy. They are more likely to be married but if they have unwanted pregnancies they may resort to unsafe abortion. They are also more likely to acquire STIs such as HIV and to develop AIDS.

- Major issues among young people aged 20–24 years include; unemployment, gender-based violence, (rape, abduction), unwanted pregnancy/abortion, and sex in exchange for money or gifts. Because of this they have the greatest risk of STIs including HIV/AIDS.

- To effect positive behaviour change, you need to be active in training or sensitising community leaders, religious leaders, kebele officials, and parliamentarians on SRH so that they too can advocate on access to information and services.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 12

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering these questions. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Distance Learning Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the Notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of this Module.

SAQ 12.1 (tests Learning Outcomes 12.1 and 12.2)

In the rural village where you are working you are informed by the kebele leaders that the adolescents are having significant problems. Some identified problems are violence against adolescent girls on their way to school or to social activities such as markets, and fetching water, boys engaging in risky behaviours including drinking alcohol, chewing khat, and going to prostitutes especially when they get the chance to go to the towns. There are two primary and one secondary school serving the neighbouring communities.

- a. What strategies would you use to approach the adolescents?

- b. Which groups of individuals in the community need to be involved to implement your activities aimed at changing the behaviour of the adolescents?

- a. There are many ways you can reach the adolescents. You may organise community conversations (in schools or in the community) to increase the community’s awareness of protective behaviours. You may also use peer educators to promote age appropriate family life education.

- b. To effect positive behaviour change, you need to be active in training or sensitising community leaders, religious leaders, kebele officials, and parliamentarians on adolescent and youth sexual and reproductive health issues so that they too can advocate on access to information and services for young people.

SAQ 12.2 (tests Learning Outcomes 112.1, 2.3 and 12.4)

In the same village where you are working (SAQ 12.1), you note that the adolescents aged 15–19 are a particularly vulnerable group who need your special attention.

- a. What are the common challenges that you expect adolescent girls aged 15–19 years to experience?

- b. What specific actions are necessary to address your concerns for this group?

- a. In a rural setting these groups of girls are considered mature enough to get married and hence start sexual activity. They may nevertheless have unwanted pregnancies and this may lead them to seek unsafe abortions. Some may be in polygamous marriages or married to an older husband and they may not have been able to negotiate for safer sex using a condom thereby possibly exposing themselves to the risk of STIs such as HIV. They may also have to face other reproductive health risks including; sexual harassment, rape, abduction and FGM They are at risk of dropping out of school because they are expected to do other work.

- b. These are some of the activities that you are able to initiate:

- Select and train mentors and educators from the community.

- Train boys and girls as peer educators on SRH to disseminate information and provide non-prescriptive contraceptives in clubs and other venues where young people in this age group gather.

- Provide age appropriate family life education in clubs and other venues where this group gather.

- Create awareness of the new family law which sets the minimum age at marriage of 18 years for both males and females.

- Train and sensitise parents, community members and faith based organisations on SRH issues such as HTP, gender based violence.

Except for third party materials and/or otherwise stated (see terms and conditions ) the content in OpenLearn is released for use under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Sharealike 2.0 licence . In short this allows you to use the content throughout the world without payment for non-commercial purposes in accordance with the Creative Commons non commercial sharealike licence. Please read this licence in full along with OpenLearn terms and conditions before making use of the content.

When using the content you must attribute us (The Open University) (the OU) and any identified author in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Licence.

The Acknowledgements section is used to list, amongst other things, third party (Proprietary), licensed content which is not subject to Creative Commons licensing. Proprietary content must be used (retained) intact and in context to the content at all times. The Acknowledgements section is also used to bring to your attention any other Special Restrictions which may apply to the content. For example there may be times when the Creative Commons Non-Commercial Sharealike licence does not apply to any of the content even if owned by us (the OU). In these stances, unless stated otherwise, the content may be used for personal and non-commercial use. We have also identified as Proprietary other material included in the content which is not subject to Creative Commons Licence. These are: OU logos, trading names and may extend to certain photographic and video images and sound recordings and any other material as may be brought to your attention.

Unauthorised use of any of the content may constitute a breach of the terms and conditions and/or intellectual property laws.

We reserve the right to alter, amend or bring to an end any terms and conditions provided here without notice.

All rights falling outside the terms of the Creative Commons licence are retained or controlled by The Open University.

Head of Intellectual Property, The Open University

- Resources & Tools

Take Action

Join the movement of young people working to protect our health and lives

Action Center

Module 3. male adolescent reproductive and sexual health.

This module discusses misconceptions around male sexual health and how they affect health care delivery, identifies male-friendly health services, and describes how to take a male-focused sexual health history. Participants also learn best practices for administering STI screenings, performing a male genital exam, and recognizing male sexual health concerns.

Download Powerpoint

AMAZE videos:

Want to learn more about AMAZE? Visit AMAZE.org .

Sign up for updates, sign up for updates.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Inter-Agency Field Manual on Reproductive Health in Humanitarian Settings: 2010 Revision for Field Review. Geneva: Inter-agency Working Group on Reproductive Health in Crises; 2010.

Inter-Agency Field Manual on Reproductive Health in Humanitarian Settings: 2010 Revision for Field Review.

4 adolescent reproductive health, 1. introduction.

Adolescence is one of life’s most fascinating and complex life stages and is accompanied by special reproductive health (RH) needs. Adolescents are resilient, resourceful and energetic. They can support each other through peer-to-peer counselling, education and outreach and contribute to their communities through activities such as assisting health providers as volunteers, providing care to people living with HIV/AIDS (PLHIV), and expanding access to quality RH services for their peers at the community level.

Humanitarian emergencies are accompanied by inherent risks that increase adolescents’ vulnerability to violence, poverty, separation from families, sexual abuse and exploitation. These factors can disrupt protective family and social structures, peer networks, schools and religious institutions and can greatly affect the ability of adolescents to practise safe RH behaviours. Their new environment can be violent, stressful and/or unhealthy. Adolescents (especially young women) who live under marginalized circumstances are highly vulnerable to sexual coercion, exploitation and violence, and may have no choice but to engage in high-risk or transactional sex for survival.

On the other hand, crisis-affected communities may also be exposed to new opportunities, including access to better health care, schooling and learning new languages and skills, which may place adolescents in privileged positions they would not have had in a non-crisis environment. Adolescents often adapt easily to new situations and can learn quickly how to navigate through the new environment.

RH officers, RH programme managers and health-care providers working in humanitarian settings must consider and address the special needs of adolescents who are transitioning to adulthood in very complex and difficult settings. They must also consider especially vulnerable adolescents, including former child soldiers, children heading households, adolescent mothers and young girls who are at an increased risk of sexual exploitation.

2. Objectives

The objectives of this chapter are to:

- provide guidance to RH officers, programme managers and service providers on effective adolescent reproductive health (ARH) approaches in humanitarian settings;

- list the principles and resources that inform RH officers, programme managers, service providers and community members on how to involve adolescents in RH programmes;

- ensure the provision of youth -friendly RH services and create an environment where adolescents can develop and thrive, despite the many challenges they face throughout a crisis.

While this chapter refers to adolescents (ages 10-19), the services described here can be extended to a broader cadre of young people (ages 10 to 24) that can also benefit from youth -friendly services.

3. Programming

At the onset of an emergency, implement the Minimum Initial Service Package (MISP) for reproductive health (See Chapter 2 : MISP). The MISP does not address all of adolescents’ needs and it may not be possible to incorporate all ARH principles when implementing the MISP. MISP implementation, however, must be done in a way that is sensitive to the needs and preferences of adolescents. Incorporate the following as part of the initial response:

- Make condoms, both male and female, available in places where adolescents meet, preferably in private, accessible locations where they can access them clandestinely.

- Ensure adolescent girls are safe when carrying out household tasks such as collecting firewood, water or food.

- Ensure pregnant adolescent girls have access to emergency obstetric care services and referral mechanisms when necessary.

- Establish clinical care and referral services for survivors of sexual violence that are sensitive to adolescent needs and respect confidentiality.

3.1. Needs assessment

As the situation stabilizes, conduct a needs assessment in coordination with other RH and child health actors to inform the programme design process and develop an action plan to improve the youth -friendliness of existing health services based on the assessment. Involve adolescents in this process, who can identify their own vulnerabilities as well as capacities. Use youth-friendly service assessment tools to determine whether health services meet the needs of adolescents. Also assess protective community resources. Gather information on:

- prevalence of RH issues among adolescents , including pregnancy, maternal and neonatal mortality and STI /HIV;

- adolescent vulnerabilities and harmful practices , including exposure to sexual violence and exploitation, trafficking, transactional sex and traditional practices such as female genital mutilation /cutting;

- protective community resources , such as supportive parents and teachers, and youth programmes with connections to caring adults;

- adolescent services , including professional and traditional services. Any reasons for gaps in the provision of and access to services should also be identified;

- perceptions of ARH: the adolescent and community perceptions of ARH needs, and of providing RH services and information to adolescents;

- barriers to accessing existing services , including insecurity, cultural norms, lack of confidentiality/privacy and lack of same-sex health-care professionals.

In addition, RH officers, programme managers and service providers must be familiar with national legislation and policies pertaining to adolescent reproductive health in the countries in which they work. Considerations should include:

- What are the laws or policies that restrict or protect adolescents’ access to RH information and services?

- What is the age of majority? What is the age of consent for sex? What is the age of consent for marriage? Is it different for boys/men and girls/women?

- Are there requirements for marital, parental or guardian approval for providing health information and services to children? And to non-child adolescents?

- Is the evolving capacity and best interest of children taken into consideration in laws/policies/protocols regulating their access to RH services, information and education?

- Are there national or local laws or policies regarding sexual violence and other forms of abuse against children both within and outside of the family?

- Are there mandatory requirements for health-care providers to report child abuse (including sexual abuse) and/or sexual assault? If yes, to whom and what happens once the case is reported?

- Who is allowed to gather forensic evidence in the health sector in cases relating to sexual violence against a child and who is allowed to testify about this evidence in court?

- What are the local children’s rights and women’s rights organizations that work to support the access of children and adolescents to RH information and services?

3.2. Principles for working with adolescents

When working with adolescents, it is important to consider:

- management principles

- service provision principles.

3.2.1. Management principles

Adolescents are not a homogeneous group: Their needs vary by age, sex, education and marital status. RH behaviour change messages need to be age (10 to 14 years old and 15 to 19 years old) and sex appropriate.

Engage in meaningful adolescent participation: The primary principle in working effectively with adolescents is to promote their participation, partnership and leadership. Because of the barriers adolescents face when accessing RH services, they should be involved in all aspects of programming, including design, implementation and monitoring. For example, it is helpful to identify youth who served as youth leaders or peer educators in their communities. These youth can help address the needs of their peers during programme design and can assist with implementing activities, such as condom distribution, peer education, monitoring of youth-friendly health services and referrals to gender-based violence counsellors. Services will be more accepted if they are tailored to needs identified by adolescents themselves. Adolescents may be helpful in ensuring that the MISP also addresses their needs, for example, by identifying culturally sensitive locations to make condoms available.

Community involvement: Understanding the cultural context and creating a supportive environment is critical to advancing RH services for adolescents as these may be affected by community values regarding adolescent reproductive and sexual health. Adults frequently become especially protective of cultural norms and the process of socializing youth when an emergency occurs. At the onset of the humanitarian response, it is important to make priority RH information and services available, including for adolescents, as outlined in the MISP (see Chapter 2 ). As soon as possible, focus on involving communities in issues that affect adolescent health, as this can lead to more sustained, positive health impacts. Community members, including parents, guardians and religious leaders, must be consulted and involved in developing programmes with and for adolescents.

3.2.2. Service provision principles

Privacy, confidentiality and honesty: Adolescents presenting to health providers often feel ashamed, embarrassed or confused. It is important for providers to create the most private space possible in which to talk. Information is disseminated rapidly among adolescents and if their confidentiality is breached even once, youth will not access available services.

Linking HIV prevention, treatment and care, and reproductive health : When adolescents access health services seeking HIV information, testing and care, there is an opportunity to promote comprehensive RH services such as:

- safer sex, including the use of dual protection

- family planning methods

- STI counselling and treatment

Conversely, offer all adolescents accessing family planning or other RH services the opportunity to learn about their HIV status, provided that care and treatment are available (see Chapter 5 : Family Planning, Box 24 , p. 108: Contraceptive Considerations for Adolescents).

Sex of the service provider : Whenever possible, an adolescent should be referred to a provider of the same sex, unless they prefer otherwise. Ensure that adolescent survivors of gender-based violence who are seeking support and care at a health facility have a female support person present in the examination room when a male provider is the only person available. This is essential when the survivor is an adolescent girl, but it is important also to give this option to adolescent boys who are survivors of gender-based violence.

3.3. Programming considerations for adolescents

It is important for programme managers to remember the following factors that may increase the vulnerability of adolescents during an emergency:

- Adolescent girls have greater vulnerabilities compared to their male counterparts: Existing power differences in relations between men and women can be heightened during an emergency. Adolescent girls are frequently expected to sustain social or cultural norms, such as being submissive to men, caring for the family, staying at home and marrying young. Moreover, changing power dimensions created as a result of mixing of displaced and host populations can place adolescent girls at increased risk. Economic hardships lead to increased exploitation, such as trafficking and the exchange of sex for money and other necessities, with their related RH risks (HIV, STIs, early pregnancy and unsafe abortion). Adolescent girls are vulnerable to gender-based violence , including sexual violence, domestic violence, female genital mutilation /cutting and forced early marriage. The risks of a pregnancy for an adolescent girl can be exacerbated by pre-existing health conditions such as anaemia. Young married girls often lack voice and decision-making power within the household due to the power inequalities with their husbands.

- Social norms and social supports are disrupted in a crisis situation: The breakdown of social structures can be protective if harmful practices are discontinued, but it can also be a risk to adolescent health. The use of free time of adolescents in crisis settings may not be subjected to the same kind of scrutiny that would be under normal circumstances. When adolescents are separated from family, friends, teachers, community members and traditional culture, there is less social control of risky behaviour. Without access to adequate information and services, adolescents are more likely to be exposed to unsafe sexual practices, that could result in unwanted pregnancy, unsafe abortion, STIs and HIV.

- Humanitarian crises can disrupt youth -adult partnerships at a time when role models are essential: In stable settings, adolescents usually have role models in the family and community; such role models may not be obvious in crisis settings. Service providers and youth club leaders may become important role models and must be aware of their potential influence.

- Humanitarian crises usually disrupt not only daily life, but adolescents’ future perspectives: For adolescents this may manifest in a fatalistic view on life and lead to increased risk taking, such as violence, substance use and/or unsafe sexual activity. Adolescents who attend activities or programmes assisting them to plan for the future should be provided with immediate reasons to consider the consequences of unsafe sexual activity and the need to take responsibility for their actions. Training in improved decision-making, negotiation and other life skills can be effective in encouraging adolescents to think through how to improve their current situation.

- Adolescents can take on adult roles, in emergencies: Adolescents may be forced to take on adult roles and need coping skills that far exceed their years. Humanitarian crises may cause adolescents to wield more power than their adult counterparts, which leads to further social confusion.

- Vulnerable groups: Attention should be paid to age-, gender-, marital status- and context-specific vulnerabilities (see Box 19 ).

Box 19 Vulnerable Groups among Adolescents

Vulnerable groups among adolescents include:

- Very young adolescents (10 to 14)

- Girl mothers

- Orphans and vulnerable children

- Child heads of households

- Young married girls

- HIV-positive adolescents

- Child soldiers (including girls) and other children associated with fighting forces (in noncombatant roles)

- Adolescents engaged in transactional sex

- Adolescent survivors of sexual violence, trafficking and other forms of gender-based violence

- Adolescents engaging in same-sex intercourse

3.4. Services for adolescents

3.4.1. provision of rh services at health facilities.

Health services can play an important role in promoting and protecting the health of adolescents, yet there is abundant evidence that adolescents see available health services as not responding to their needs. Adolescents mistrust and avoid services or seek help only when they are in desperate need of care. One important strategy in facilitating adolescent access to and use of RH services is to ensure that they are of high quality and “ youth -friendly”. At the same time, adolescents need to be made aware of the availability of youth-friendly services. Youth-friendly RH care services have characteristics that make them more responsive to the particular RH needs of adolescents, including the provision of contraceptives, emergency contraception, safe abortion care, STI diagnosis and treatment, HIV counselling, testing and care, and antenatal and postnatal care.

3.4.2. Provider questionnaire for adolescents

It is good practice to screen all adolescents who enter the health system for sexual and RH issues, substance use and mental health concerns. In doing this, the health-care provider will send a message to the adolescent that he or she cares about their needs and that the health centre is a safe place to discuss RH-related issues. In addition, the information can be used by health providers to provide appropriate counseling and referrals.

Table 9 Youth-friendly Health Service Characteristics

View in own window

Before collecting information from adolescents, consider the services available for referrals. Only ask sensitive questions if appropriate responses to potentially harmful situations can be provided, otherwise more damage may be done. A possible adolescent psychosocial assessment that will help guide health providers to ask age-appropriate questions and adequately assess adolescent needs follow the pneumonic HEADSSS: Home, Education/Employment, Activities, Drugs, Sexuality, Suicide and Depression, Safety.

3.4.3. Provision of RH services in the community

Community-based provision of services and information offers opportunities for adolescents to demonstrate leadership and gain new skills through volunteerism while gaining youth -adult partnerships. The community is also an ideal setting to receive RH information where adolescents are comfortable and open to dialogue and personal risk assessments.

Peer educators

Peer education offers many benefits since peers are usually perceived as safe and trustworthy sources of information. Well-designed, curriculum-based peer education programmes and supervised peer educators can be successful in improving adolescents’ knowledge, attitudes and skills about reproductive health and HIV prevention. To ensure quality in peer education programmes:

- Provide high-quality, intensive training to peer educators, including regular assessments and reinforcement of their capacities, so they can provide accurate information to their peers.

- Use standardized checklists in the development and implementation of peer education programmes to improve quality.

Community-based distribution

Youth trained as community-based distributors (CBD) are young people who have been trained to provide contraceptive counselling to their peers in the community. They typically focus on the provision of RH information, oral contraceptives, condoms and information on HIV, and refer clients to the health centre for other contraceptive methods and services. Youth CBDs can effectively integrate RH and HIV information. Since many barriers preclude adolescents from accessing RH services at clinics, training youth CBDs is a successful strategy to increase adolescents’ access to RH services and information while giving the youth CBDs themselves leadership roles in the community. Youth CBDs often become allies of facility-based health services, through working with service providers on improving the quality of youth-friendly services.

Community dialogue

In addressing the principle of community involvement, use community dialogue to gain support from and build the skills of community members. Adults need information, skills and encouragement not only to support ARH programming but also to feel more comfortable in providing information to adolescents.

3.4.4. Provide RH services in schools

Make ARH services and information available in formal and non-formal schools as well as at vocational training centres. Link with educators to advocate for the creation of an enabling environment to ensure the provision of RH services for adolescents.

Sex-specific hygiene facilities

Adolescents are likely to be uncomfortable and embarrassed about sharing hygiene facilities with the opposite sex, and even with younger children. This is especially likely for girls during menstruation. Also, mixed-sex bathroom facilities are often cited as the location of school-related gender-based violence . A lack of sex-specific hygiene facilities, as well as a lack of feminine hygiene products, will discourage adolescent girls from attending school. In order to minimize school absenteeism and school-related sexual harassment and assault, and to promote a safer learning environment:

- Ensure safe, sex-specific hygiene facilities in schools.

- Provide girls with cloth or other culturally appropriate sanitary materials for use during menstruation.

Curricula-based life skills education

Sexuality and HIV education programmes based on a written curriculum and implemented among groups of adolescents are a promising intervention to reduce adolescent sexual risk behaviours. Programme managers often tailor curricula to fit the local context. Characteristics of life skills curricula that have an impact on adolescent behaviours are outlined in Table 10 .

Characteristics of Effective Life Skills Programmes.

RH officers and programme managers can provide technical assistance to teachers and community educators to ensure they are comfortable in addressing the topics and choosing appropriate lessons for life skills curricula (see Box 20 ).

Box 20 Life Planning Skills

Life planning skills education includes:

- Physical and emotional changes to expect during puberty

- Family planning

- Mental health

- Age-appropriate life skills for younger adolescents such as identifying values, understanding consequences of behaviours

- RH life skills, such as condom self-efficacy, negotiating safe sex, refusing unwanted sex

- Sexuality and gender (including socially constructed gender norms)

- Health literacy and fertility awareness

- HIV/AIDS prevention

- Prevention of gender-based violence

- Linkages to health facilities, encouraging adolescents to seek out these services

- Other life skills, such as decision-making, critical thinking, creativity, establishing values, communication, coping with emotions and stress

3.5. Coordinating and making linkages with youth programmes

Making links and coordinating between youth programmes will enable the provision of more comprehensive services.

- Link RH services with community services for adolescents: Adolescents often seek out adults they trust in safe spaces where they feel information can be shared in confidence. Often, these people are working at the community level. Put in place referral systems to ensure that adolescents receive the appropriate treatment for problems that might be revealed outside the clinical setting (e.g. sexual violence, unwanted pregnancy or unsafe abortion).

- Ensure multisectoral programming: RH practitioners may not be able, or have the skills, to include livelihood components in their programme. In coordination with the health cluster /sector, liaise with camp management and other cluster coordination groups to establish links between youth programmes, health and protection, psychosocial services, education and livelihood opportunities. Support the implementation of vocational training and skills development for adolescents; this will enhance their feeling of control and optimism for the future, and is essential to reconstruct and rehabilitate their social networks and communities, both during and after a humanitarian crisis . Collaborate with adolescent skills-building programmes as a source for referral and to integrate RH information into livelihood programmes.

- Engage men and boys as agents of social change: Rigid male social norms have been linked to increased sexual risk-taking, which can lead to higher STI and HIV transmission, as well as increased substance use and gender-based violence . Conditions in humanitarian settings may challenge men who might feel under pressure to play out their traditional roles as providers and protectors, where they are dependent on external assistance. Resulting frustration and humiliation can lead to increased risk-taking behaviour and domestic violence. Adolescent boys need safe environments where alternative male norms can be modelled while deconstructing traditional social norms. Gain the support of men and boys: give them the opportunity to address their own needs and actively engage them in reproductive health , thereby benefitting both adolescent girls and boys.

- Girls’ empowerment and socialization: Working with girl-only groups is an ideal way to also challenge female social norms of passivity, sub-service and inferiority to men. Encourage girls to find their voice and solidify their beliefs and values, thereby enhancing their potential to be equal contributors to society. Humanitarian settings often make communities protective of the traditional roles of women. Design programmes to empower girls with this in mind.

3.6. Advocacy

Sensitize and orient influential people who are part of the relief/development community as well as the community being served to the RH vulnerabilities, specific needs and rights of adolescents. RH officers, RH managers and service providers must be change agents and:

- advocate for information and services for adolescents that ensure available services are youth -friendly;