Thesis Statements

What is a thesis statement.

Your thesis statement is one of the most important parts of your paper. It expresses your main argument succinctly and explains why your argument is historically significant. Think of your thesis as a promise you make to your reader about what your paper will argue. Then, spend the rest of your paper–each body paragraph–fulfilling that promise.

Your thesis should be between one and three sentences long and is placed at the end of your introduction. Just because the thesis comes towards the beginning of your paper does not mean you can write it first and then forget about it. View your thesis as a work in progress while you write your paper. Once you are satisfied with the overall argument your paper makes, go back to your thesis and see if it captures what you have argued. If it does not, then revise it. Crafting a good thesis is one of the most challenging parts of the writing process, so do not expect to perfect it on the first few tries. Successful writers revise their thesis statements again and again.

A successful thesis statement:

- makes an historical argument

- takes a position that requires defending

- is historically specific

- is focused and precise

- answers the question, “so what?”

How to write a thesis statement:

Suppose you are taking an early American history class and your professor has distributed the following essay prompt:

“Historians have debated the American Revolution’s effect on women. Some argue that the Revolution had a positive effect because it increased women’s authority in the family. Others argue that it had a negative effect because it excluded women from politics. Still others argue that the Revolution changed very little for women, as they remained ensconced in the home. Write a paper in which you pose your own answer to the question of whether the American Revolution had a positive, negative, or limited effect on women.”

Using this prompt, we will look at both weak and strong thesis statements to see how successful thesis statements work.

While this thesis does take a position, it is problematic because it simply restates the prompt. It needs to be more specific about how the Revolution had a limited effect on women and why it mattered that women remained in the home.

Revised Thesis: The Revolution wrought little political change in the lives of women because they did not gain the right to vote or run for office. Instead, women remained firmly in the home, just as they had before the war, making their day-to-day lives look much the same.

This revision is an improvement over the first attempt because it states what standards the writer is using to measure change (the right to vote and run for office) and it shows why women remaining in the home serves as evidence of limited change (because their day-to-day lives looked the same before and after the war). However, it still relies too heavily on the information given in the prompt, simply saying that women remained in the home. It needs to make an argument about some element of the war’s limited effect on women. This thesis requires further revision.

Strong Thesis: While the Revolution presented women unprecedented opportunities to participate in protest movements and manage their family’s farms and businesses, it ultimately did not offer lasting political change, excluding women from the right to vote and serve in office.

Few would argue with the idea that war brings upheaval. Your thesis needs to be debatable: it needs to make a claim against which someone could argue. Your job throughout the paper is to provide evidence in support of your own case. Here is a revised version:

Strong Thesis: The Revolution caused particular upheaval in the lives of women. With men away at war, women took on full responsibility for running households, farms, and businesses. As a result of their increased involvement during the war, many women were reluctant to give up their new-found responsibilities after the fighting ended.

Sexism is a vague word that can mean different things in different times and places. In order to answer the question and make a compelling argument, this thesis needs to explain exactly what attitudes toward women were in early America, and how those attitudes negatively affected women in the Revolutionary period.

Strong Thesis: The Revolution had a negative impact on women because of the belief that women lacked the rational faculties of men. In a nation that was to be guided by reasonable republican citizens, women were imagined to have no place in politics and were thus firmly relegated to the home.

This thesis addresses too large of a topic for an undergraduate paper. The terms “social,” “political,” and “economic” are too broad and vague for the writer to analyze them thoroughly in a limited number of pages. The thesis might focus on one of those concepts, or it might narrow the emphasis to some specific features of social, political, and economic change.

Strong Thesis: The Revolution paved the way for important political changes for women. As “Republican Mothers,” women contributed to the polity by raising future citizens and nurturing virtuous husbands. Consequently, women played a far more important role in the new nation’s politics than they had under British rule.

This thesis is off to a strong start, but it needs to go one step further by telling the reader why changes in these three areas mattered. How did the lives of women improve because of developments in education, law, and economics? What were women able to do with these advantages? Obviously the rest of the paper will answer these questions, but the thesis statement needs to give some indication of why these particular changes mattered.

Strong Thesis: The Revolution had a positive impact on women because it ushered in improvements in female education, legal standing, and economic opportunity. Progress in these three areas gave women the tools they needed to carve out lives beyond the home, laying the foundation for the cohesive feminist movement that would emerge in the mid-nineteenth century.

Thesis Checklist

When revising your thesis, check it against the following guidelines:

- Does my thesis make an historical argument?

- Does my thesis take a position that requires defending?

- Is my thesis historically specific?

- Is my thesis focused and precise?

- Does my thesis answer the question, “so what?”

Download as PDF

6265 Bunche Hall Box 951473 University of California, Los Angeles Los Angeles, CA 90095-1473 Phone: (310) 825-4601

Other Resources

- UCLA Library

- Faculty Intranet

- Department Forms

- Office 365 Email

- Remote Help

Campus Resources

- Maps, Directions, Parking

- Academic Calendar

- University of California

- Terms of Use

Social Sciences Division Departments

- Aerospace Studies

- African American Studies

- American Indian Studies

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Asian American Studies

- César E. Chávez Department of Chicana & Chicano Studies

- Communication

- Conservation

- Gender Studies

- Military Science

- Naval Science

- Political Science

- Recent changes

- Random page

- View source

- What links here

- Related changes

- Special pages

- Printable version

- Permanent link

- Page information

- Create account

Why was the Turner Thesis abandoned by historians

Fredrick Jackson Turner’s thesis of the American frontier defined the study of the American West during the 20th century. In 1893, Turner argued that “American history has been in a large degree the history of the colonization of the Great West. The existence of an area of free land, its continuous recession, and the advance of American settlement westward explain American development.” ( The Frontier in American History , Turner, p. 1.) Jackson believed that westward expansion allowed America to move away from the influence of Europe and gain “independence on American lines.” (Turner, p. 4.) The conquest of the frontier forced Americans to become smart, resourceful, and democratic. By focusing his analysis on people in the periphery, Turner de-emphasized the importance of everyone else. Additionally, many people who lived on the “frontier” were not part of his thesis because they did not fit his model of the democratizing American. The closing of the frontier in 1890 by the Superintendent of the census prompted Turner’s thesis.

Despite its faults, his thesis proved powerful because it succinctly summed up the concerns of Turner and his contemporaries. More importantly, it created an appealing grand narrative for American history. Many Americans were concerned that American freedom would be diminished by the end of colonization of the West. Not only did his thesis give voice to these Americans’ concerns, but it also represented how Americans wanted to see themselves. Unfortunately, the history of the American West became the history of westward expansion and the history of the region of the American West was disregarded. The grand tapestry of western history was essentially ignored. During the mid-twentieth century, most people lost interest in the history of the American West.

While appealing, the Turner thesis stultified scholarship on the West. In 1984, colonial historian James Henretta even stated, “[f]or, in our role as scholars, we must recognize that the subject of westward expansion in itself longer engages the attention of many perhaps most, historians of the United States.” ( Legacy of Conquest , Patricia Limerick, p. 21.) Turner’s thesis had effectively shaped popular opinion and historical scholarship of the American West, but the thesis slowed continued academic interest in the field.

Reassessment of Western History

In the last half of the twentieth century, a new wave of western historians rebelled against the Turner thesis and defined themselves by their opposition to it. Historians began to approach the field from different perspectives and investigated the lives of Women, miners, Chicanos, Indians, Asians, and African Americans. Additionally, historians studied regions that would not have been relevant to Turner. In 1987, Patricia Limerick tried to redefine the study of the American West for a new generation of western scholars. In Legacy of Conquest, she attempted to synthesize the scholarship on the West to that point and provide a new approach for re-examining the West. First, she asked historians to think of the America West as a place and not as a movement. Second, she emphasized that the history of the American West was defined by conquest; “[c]onquest forms the historical bedrock of the whole nation, and the American West is a preeminent case study in conquest and its consequences.” (Limerick, p. 22.)

Finally, she asked historians to eliminate the stereotypes from Western history and try to understand the complex relations between the people of the West. Even before Limerick’s manifesto, scholars were re-evaluating the west and its people, and its pace has only quickened. Whether or not scholars agree with Limerick, they have explored new depths of Western American history. While these new works are not easy to categorize, they do fit into some loose categories: gender ( Relations of Rescue by Peggy Pascoe), ethnicity ( The Roots of Dependency by Richard White, and Lewis and Clark Among the Indians by James P. Rhonda), immigration (Impossible Subjects by Ming Ngai), and environmental (Nature’s Metropolis by William Cronon, Rivers of Empire by Donald Worster) history. These are just a few of the topics that have been examined by American West scholars. This paper will examine how these new histories of the American West resemble or diverge from Limerick’s outline.

Defining America or a Threat to America's Moral Standing

Peggy Pascoe’s Relations of Rescue described the creation and operation of Rescue Homes in Salt Lake City, the Sioux Reservation, Denver and San Francisco by missionary women for abused, neglected and exploited women. By focusing on the missionaries and the tenants of these homes, Pascoe depicted not just relations between women, but provided examples of how missionaries responded to issues which they believed were unique in the West. Issues that not only challenged the Victorian moral authority but threatened America’s moral standing. Unlike Turner, the missionary women did not believe that the West was an engine for democracy; instead, they envisioned a place where immoral practice such as polygamy, prostitution, premarital pregnancy, and religious superstition thrived and threatened women’s moral authority. Instead of attempting to portray a prototypical frontier or missionary woman, Pascoe reveals complicated women who defy easy categorization. Instead of re-enforcing stereotypes that women civilized (a dubious term at best) the American West, she instead focused on three aspects of the search for female moral authority: “its benefits and liabilities for women’s empowerment; its relationship to systems of social control; and its implication for intercultural relations among women.” (Pascoe, p. xvii.) Pascoe used a study of intercultural relations between women to better understand each of the sub-cultures (missionaries, unmarried mothers, Chinese prostitutes, Mormon women, and Sioux women) and their relations with governmental authorities and men.

Unlike Limerick, Pascoe did not find it necessary to define the west or the frontier. She did not have to because the Protestant missionaries in her story defined it for her. While Turner may have believed that the West was no longer the frontier in 1890, the missionaries certainly would have disagreed. In fact, the rescue missions were placed in the communities that the Victorian Protestant missionary judged to be the least “civilized” parts of America (Lakota Territory, San Francisco’s Chinatown, rough and tumble Denver and Salt Lake City.) Instead of being a story of conquest by Victorian or western morality, it was a story of how that morality was often challenged and its terms were negotiated by culturally different communities. Pascoe’s primary goal in this work was not only to eliminate stereotypes but to challenge the notion that white women civilized the west. While conquest may be a component of other histories, no one group in Pascoe’s story successfully dominated any other.

Changing the Narrative of Native Americans in the West

Two books were written before Legacy was published, Lewis and Clark Among the Indians (James Rhonda) and The Roots of Dependency (Richard White) both provide a window into the world of Native Americans. Both books took new approaches to Native American histories. Rhonda’s book looked at the familiar Lewis and Clark expedition but from an entirely different angle. Rhonda described the interactions between the expedition and the various Native American tribes they encountered. White’s book also sought to describe the interactions between the United States and the Choctaws, Pawnees, and Navajos, but he sought to explain why the economies of these tribes broke down after contact. Each of these books covers new ground by addressing the impact of these interactions between the United States and the Native Americans.

Whether or not Rhonda’s work is an example of the New Western History is debatable, but he sought to eliminate racial stereotypes of Native Americans and describe the first governmental attempt to conquer the western landscape by traversing it. Rhonda described the interactions between the expedition and the various Indians who encountered it. While Rhonda’s book may resemble a classic Lewis and Clark history, it provides a much more nuanced examination of the limitations and effectiveness of the diplomatic aspects of the Lewis and Clark expedition. He took a great of time to describe each of the interactions with the Indian tribes in detail. Rhonda recognized that the interactions between the expedition and the various tribes were nuanced and complex. Rhonda’s work clarified that Native Americans had differing views of the Lewis and Clark expedition. Any stereotypes the reader may have regarding the Native Americans with would have shattered. Additionally, Rhonda described how the expedition persevered despite its clumsy attempts at diplomacy.

Instead of describing the initial interactions of the United States government with the Choctaws, Pawnees, and Navajos, White explained how the self-sufficient economies of these people were destroyed. White described how the United States government turned these successful native people into wards of the American state. His story explained how the United States conquered these tribes without firing a shot. The consequence of this conquest was the creation of weak, dependent nations that could not survive without handouts from the federal government. Like Rhonda, White also sought to shatter long-standing stereotypes and myths regarding Native Americans. White verified that each of these tribes had self-sufficient economies which permitted prosperous lifestyles for their people before the devastating interactions with the United States government occurred. The United States in each case fundamentally altered the tribes’ economies and environments. These alterations threatened the survival of the tribes. In some cases, the United States sought to trade with these tribes in an effort put the tribes in debt. After the tribes were in debt, the United States then forced the tribes to sell their land. In other situations, the government damaged the tribes’ economies even when they sought to help them.

Even though White book was published a few years before Legacy, The Roots of Dependency certainly satisfies some of Limerick’s stated goals. Conquest and its consequences are at the heart of White’s story. White details the problems these societies developed after they became dependant on American trade goods and handouts. White also dissuaded anyone from believing that the Native American economies were inefficient. The Choctaws, Pawnees, and Navajos economies were successful. The Choctaws and Pawnees had thriving economies and their food supplies were more than sufficient. While the Navajos were not as successful as the other two tribes, their story was remarkable because they learned how to survive in some of the most inhospitable lands in the American West. These stories exploded the myths that the Native Americans subsistence economies were somehow insufficient.

The Impact of Immigrants to the West

The American West was both a borderland and a destination for a multitude of immigrants. Native Americans, Spaniards, Mexicans, Anglos, and Asians have all immigrated into the American West. The American West has seen waves of immigration. These immigrants have constantly changed the complexion of its people. Starting with the Native Americans who first moved into the region and the most recent tide of undocumented Mexican immigrants, the West has always been a place where immigrants seeking their fortunes. The California gold rush brought in a number of immigrants who did not fit their American ideal. When non-whites started immigrating to California, the United States was faced with a new problem, the introduction of people who could not become citizens. Chinese immigrants troubled the Anglo majority because they could not be easily assimilated into American society. Additionally, many Americans were perplexed by their substantially different appearances, clothing, religions, and cultures. Anglos became concerned that the new immigrants differed too much from them. In 1924, after 150 years of unregulated immigration, the United States Congress passed the Johnson-Reed Act, the most restrictionist immigration law in US history. The Johnson-Reed Act was specifically designed to keep the most undesirable races out of America, but immigrants continued to arrive in America without documents. Ming Ngai’s Impossible Subjects addresses this new class of immigrants: illegal immigrants. Illegal immigrants began to flow into the United States soon after the passage of the Johnson-Reed Act.

While illegal immigration is not an issue isolated to the history of the American West, the immigrants moved predominantly into California, Texas and the American Southwest. Like Anglo settlers who were attracted to the West for the potential for new life in the nineteenth century, illegal immigrants continued to move in during the twentieth. The illegal immigrants were welcomed, despite their status, because California’s large commercial farms needed inexpensive labor to harvest their crops. Impossible Subjects describes four groups of illegal immigrants (Filipinos, Japanese, Chinese and Mexican braceros) who were created by the United States immigration policy. Ngai specifically examines the role that the government played in defining, controlling and disciplining these groups for their allegedly illegal misconduct.

Impossible Subjects is not a book on the American West, but it is a book that is very much about the American West. While Ngai’s story primarily takes place in the American West she does not appear to have any interest in defining the West because her story has national implications. The American West is relevant to her study only because it was where most of the illegal immigrants described in her story lived and worked. Additionally, it is not a story of conquest and its consequences, but it introduced the American public and scholars to members of the American society that are silent. Limerick even stated that while “Indians, Hispanics, Asians, blacks, Anglos, businesspeople, workers, politicians, bureaucrats, natives and newcomers” all shared the same region, they still needed to be introduced to one another. In addition to being a sophisticated policy debate on immigration law, Ngai’s work introduced Americans to these people. (Limerick, p. 349.)

The Rise of Western Environmental History

Environmental history has become an increasingly important component of the history of the American West. Originally, the American West was seen as an untamed wilderness, but over time that description has changed. Two conceptually different, but nonetheless important books on environmental history discussed the American West and its importance in America. Nature’s Metropolis by William Cronon and Rivers of Empire by Donald Worster each explored the environment and the economy of the American West. Cronon examined the formation of Chicago and the importance of its commodities market for the development of the American West. Alternatively, Worster focuses on the creation of an extensive network of government subsidized dams in the early twentieth century. Rivers of Empire describes that despite the aridity of the natural landscape the American West became home to massive commercial farms and enormous swaths of urban sprawl.

In Nature’s Metropolis , Cronon, used the central place theory to analyze the economic and ecological development of Chicago. Johann Heinrich von Thunen developed the central place theory to explain the development of cities. Essentially, geographically different economic zones form in concentric circles the farther you went from the city. These different zones form because of the time it takes to get the different types of goods to market. Closest to the city and then moving away you would have the following zones: first, intensive agriculture, second, extensive agriculture, third, livestock raising, fourth, trading, hunting and Indian trade and finally, you would have the wilderness. While the landscape of the Mid-West was more complicated than this, Cronon posits that the “city and country are inextricably connected and that market relations profoundly mediate between them.” (Cronon, p. 52.) By emphasizing the connection between the city of Chicago and the rural lands that surrounded it, Cronon was able to explain how the land, including the West, developed. Cronon argued that the development of Chicago had a profound influence on the development and appearance of the Great West. Essentially Cronon used the creation of the Chicago commodities and trading markets to explain how different parts of the Mid-West and West produced different types of resources and fundamentally altered their ecology.

According to Donald Worster’s Rivers of Empire, economics played an equally important role in the economic and environmental development of the Rocky Mountain and Pacific Slope states. Worster argued that the United States wanted to continue creating family farms for Americans in the West. Unfortunately, the aridity of the west made that impossible. The land in the West simply could not be farmed without water. Instead of adapting to the natural environment, the United States government embarked on the largest dam building project in human history. The government built thousands of dams to irrigate millions of acres of land. Unfortunately, the cost of these numerous irrigation projects was enormous. The federal government passed the cost on to the buyers of the land which prevented family farmers from buying it. Therefore, instead of family farms, massive commercial farms were created. The only people who could afford to buy the land were wealthy citizens. The massive irrigation also permitted the creation of cities which never would have been possible without it. Worster argues that the ensuing ecological damage to the West has been extraordinary. The natural environment throughout the region was dramatically altered. The west is now the home of oversized commercial farms, artificial reservoirs which stretch for hundreds of miles, rivers that run only on command and sprawling cities which depend on irrigation.

Both Cronon and Worster described how commercial interests shaped the landscape and ecology of the American West, but their approaches were very different. Still, each work fits comfortably into the new western history. Both Cronon and Worster see the West as a place and not as a movement of westward expansion. Cronon re-orders the typical understanding of the sequence of westward expansion. Instead of describing the steady growth of rural communities which transformed into cities, he argued that cities and rural areas formed at the same time. Often the cities developed first and that only after markets were created could land be converted profitable into farms. This development fits westward development much more closely than paradigms that emphasized the creation of family farms. Worster defines the West by its aridity. While these definitions differ from Limerick’s, they reflect new approaches. Conquest plays a critical role in each of these books. Instead of conquering people, the authors describe efforts to conquer western lands. In Cronon, westerners forever altered the landscape of the west. Agricultural activities dominated the zones closest to Chicago, cattle production took over lands previously occupied by the buffalo, and even the wilderness was changed by people to satisfy the markets in Chicago. The extensive damming of the West’s rivers described by Worster required the United States government to conquer, control and discipline nature. While this conquest was somewhat illusory, the United States government was committed to reshaping the West and ecology to fit its vision.

Each of these books demonstrates that the Turner thesis no longer holds a predominant position in the scholarship of the American West. The history of the American West has been revitalized by its demise. While westward expansion plays an important role in the history of the United States, it did not define the west. Turner’s thesis was fundamentally undermined because it did not provide an accurate description of how the West was peopled. The nineteenth century of the west is not composed primarily of family farmers. Instead, it is a story of a region peopled by a diverse group of people: Native Americans, Asians, Chicanos, Anglos, African Americans, women, merchants, immigrants, prostitutes, swindlers, doctors, lawyers, farmers are just a few of the characters who inhabit western history.

Suggested Readings

- Frederick Jackson Turner, The Frontier in American History

- Patricia Limerick, Legacy of Conquest

- Peggy Pascoe, Relations of Rescue

- Richard White, The Roots of Dependency

- Nature's Metropolis, William Cronon

- Rivers of Empire, Donald Worster

- Historiography

- Book Review

- This page was last edited on 5 October 2021, at 01:36.

- Privacy policy

- About DailyHistory.org

- Disclaimers

- Mobile view

- CAMPAIGN TRAIL

Frontier Thesis

The Frontier Thesis or Turner Thesis , is the argument advanced by historian Frederick Jackson Turner in 1893 that American democracy was formed by the American frontier. He stressed the process—the moving frontier line—and the impact it had on pioneers going through the process. He also stressed results, especially that American democracy was the primary result, along with egalitarianism , a lack of interest in high culture , and violence. "American democracy was born of no theorist's dream; it was not carried in the Sarah Constant to Virginia, nor in the Mayflower to Plymouth. It came out of the American forest, and it gained new strength each time it touched a new frontier," said Turner. In the thesis, the American frontier established liberty by releasing Americans from European mindsets and eroding old, dysfunctional customs. The frontier had no need for standing armies, established churches, aristocrats or nobles, nor for landed gentry who controlled most of the land and charged heavy rents. Frontier land was free for the taking. Turner first announced his thesis in a paper entitled " The Significance of the Frontier in American History ", delivered to the American Historical Association in 1893 in Chicago. He won wide acclaim among historians and intellectuals. Turner elaborated on the theme in his advanced history lectures and in a series of essays published over the next 25 years, published along with his initial paper as The Frontier in American History.

Turner's emphasis on the importance of the frontier in shaping American character influenced the interpretation found in thousands of scholarly histories. By the time Turner died in 1932, 60% of the leading history departments in the U.S. were teaching courses in frontier history along Turnerian lines.

Full article ...

Books/Sources

- The Frontier Thesis: Valid Interpretation of American History? - Ray Allen Billington

- The Turner Thesis: Concerning the Role of the Frontier in American History (Problems in American civilization)... - George Rogers Taylor

- Block 6 Lecture 1 Turner's Frontier Thesis

- 7 1 c 6 TURNER'S THESIS OF EXPANSION OF FRONTIER 7 1 C 6

American History

Economic history, the gilded age and progressive era (1877-1929), spread the word.

Log in with a Google or Facebook account to save game/trivia results, or to receive optional email updates.

- Which President Are You Most Similar To?

RECENT ARTICLES

- The History of the United States, in 10,000 Words

- Joseph McCarthy, and Other Facets of the 1950s Red Scare

- Did the Mayflower Go Off Course on Purpose? And Other Questions...

- The Fourteen Points, the League of Nations, and Wilson's Failed Idealism

- Jeanette Rankin, First Woman in Congress

- Anne Hutchinson and the Puritan Trials

- The National Woman Suffrage Association and the American Woman Suffrage Association

- Grover Cleveland, Mugwumps, and the 1884 Election

POPULAR ARTICLES

- The Great (Farm) Depression of the 1920s

- The "Cleveland Massacre" -- Standard Oil makes its First Attack

- Working and Voting -- Women in the 1920s

- The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 and its Effects

- The Building of the Panama Canal

- The Great Mistake - Why Did the South Secede in 1860?

- Yellow Journalism - Present and Past

- Chinatown's Sex Slaves - Human Trafficking and San Francisco's History

SEARCH OUR SITE

Writing a Thesis and Making an Argument

Almost every assignment you complete for a history course will ask you to make an argument. Your instructors will often call this your "thesis"– your position on a subject.

What is an Argument?

An argument takes a stand on an issue. It seeks to persuade an audience of a point of view in much the same way that a lawyer argues a case in a court of law. It is NOT a description or a summary.

- This is an argument: "This paper argues that the movie JFK is inaccurate in its portrayal of President Kennedy."

- This is not an argument: "In this paper, I will describe the portrayal of President Kennedy that is shown in the movie JFK."

What is a Thesis?

A thesis statement is a sentence in which you state an argument about a topic and then describe, briefly, how you will prove your argument.

- This is an argument, but not yet a thesis: "The movie ‘JFK’ inaccurately portrays President Kennedy."

- This is a thesis: "The movie ‘JFK’ inaccurately portrays President Kennedy because of the way it ignores Kennedy’s youth, his relationship with his father, and the findings of the Warren Commission."

A thesis makes a specific statement to the reader about what you will be trying to argue. Your thesis can be a few sentences long, but should not be longer than a paragraph. Do not begin to state evidence or use examples in your thesis paragraph.

A Thesis Helps You and Your Reader

Your blueprint for writing:

- Helps you determine your focus and clarify your ideas.

- Provides a "hook" on which you can "hang" your topic sentences.

- Can (and should) be revised as you further refine your evidence and arguments. New evidence often requires you to change your thesis.

- Gives your paper a unified structure and point.

Your reader’s blueprint for reading:

- Serves as a "map" to follow through your paper.

- Keeps the reader focused on your argument.

- Signals to the reader your main points.

- Engages the reader in your argument.

Tips for Writing a Good Thesis

- Find a Focus: Choose a thesis that explores an aspect of your topic that is important to you, or that allows you to say something new about your topic. For example, if your paper topic asks you to analyze women’s domestic labor during the early nineteenth century, you might decide to focus on the products they made from scratch at home.

- Look for Pattern: After determining a general focus, go back and look more closely at your evidence. As you re-examine your evidence and identify patterns, you will develop your argument and some conclusions. For example, you might find that as industrialization increased, women made fewer textiles at home, but retained their butter and soap making tasks.

Strategies for Developing a Thesis Statement

Idea 1. If your paper assignment asks you to answer a specific question, turn the question into an assertion and give reasons for your opinion.

Assignment: How did domestic labor change between 1820 and 1860? Why were the changes in their work important for the growth of the United States?

Beginning thesis: Between 1820 and 1860 women's domestic labor changed as women stopped producing home-made fabric, although they continued to sew their families' clothes, as well as to produce butter and soap. With the cash women earned from the sale of their butter and soap they purchased ready-made cloth, which in turn, helped increase industrial production in the United States before the Civil War.

Idea 2. Write a sentence that summarizes the main idea of the essay you plan to write.

Main Idea: Women's labor in their homes during the first half of the nineteenth century contributed to the growth of the national economy.

Idea 3. Spend time "mulling over" your topic. Make a list of the ideas you want to include in the essay, then think about how to group them under several different headings. Often, you will see an organizational plan emerge from the sorting process.

Idea 4. Use a formula to develop a working thesis statement (which you will need to revise later). Here are a few examples:

- Although most readers of ______ have argued that ______, closer examination shows that ______.

- ______ uses ______ and ______ to prove that ______.

- Phenomenon X is a result of the combination of ______, ______, and ______.

These formulas share two characteristics all thesis statements should have: they state an argument and they reveal how you will make that argument. They are not specific enough, however, and require more work.

As you work on your essay, your ideas will change and so will your thesis. Here are examples of weak and strong thesis statements.

- Unspecific thesis: "Eleanor Roosevelt was a strong leader as First Lady." This thesis lacks an argument. Why was Eleanor Roosevelt a strong leader?

- Specific thesis: "Eleanor Roosevelt recreated the role of the First Lady by her active political leadership in the Democratic Party, by lobbying for national legislation, and by fostering women’s leadership in the Democratic Party." The second thesis has an argument: Eleanor Roosevelt "recreated" the position of First Lady, and a three-part structure with which to demonstrate just how she remade the job.

- Unspecific thesis: "At the end of the nineteenth century French women lawyers experienced difficulty when they attempted to enter the legal profession." No historian could argue with this general statement and uninteresting thesis.

- Specific thesis: "At the end of the nineteenth century French women lawyers experienced misogynist attacks from male lawyers when they attempted to enter the legal profession because male lawyers wanted to keep women out of judgeships." This thesis statement asserts that French male lawyers attacked French women lawyers because they feared women as judges, an intriguing and controversial point.

Making an Argument – Every Thesis Deserves Its Day in Court

You are the best (and only!) advocate for your thesis. Your thesis is defenseless without you to prove that its argument holds up under scrutiny. The jury (i.e., your reader) will expect you, as a good lawyer, to provide evidence to prove your thesis. To prove thesis statements on historical topics, what evidence can an able young lawyer use?

- Primary sources: letters, diaries, government documents, an organization’s meeting minutes, newspapers.

- Secondary sources: articles and books from your class that explain and interpret the historical event or person you are writing about, lecture notes, films or documentaries.

How can you use this evidence?

- Make sure the examples you select from your available evidence address your thesis.

- Use evidence that your reader will believe is credible. This means sifting and sorting your sources, looking for the clearest and fairest. Be sure to identify the biases and shortcomings of each piece of evidence for your reader.

- Use evidence to avoid generalizations. If you assert that all women have been oppressed, what evidence can you use to support this? Using evidence works to check over-general statements.

- Use evidence to address an opposing point of view. How do your sources give examples that refute another historian’s interpretation?

Remember -- if in doubt, talk to your instructor.

Thanks to the web page of the University of Wisconsin at Madison’s Writing Center for information used on this page. See writing.wisc.edu/handbook for further information.

Conquering the West

The west as history: the turner thesis.

In 1893, the American Historical Association met during that year’s World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The young Wisconsin historian Frederick Jackson Turner presented his “frontier thesis,” one of the most influential theories of American history, in his essay, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History.”

Turner looked back at the historical changes in the West and saw, instead of a tsunami of war and plunder and industry, waves of “civilization” that washed across the continent. A frontier line “between savagery and civilization” had moved west from the earliest English settlements in Massachusetts and Virginia across the Appalachians to the Mississippi and finally across the Plains to California and Oregon. Turner invited his audience to “stand at Cumberland Gap [the famous pass through the Appalachian Mountains], and watch the procession of civilization, marching single file—the buffalo following the trail to the salt springs, the Indian, the fur trader and hunter, the cattle-raiser, the pioneer farmer—and the frontier has passed by.”

Americans, Turner said, had been forced by necessity to build a rough-hewn civilization out of the frontier, giving the nation its exceptional hustle and its democratic spirit and distinguishing North America from the stale monarchies of Europe. Moreover, the style of history Turner called for was democratic as well, arguing that the work of ordinary people (in this case, pioneers) deserved the same study as that of great statesmen. Such was a novel approach in 1893.

But Turner looked ominously to the future. The Census Bureau in 1890 had declared the frontier closed. There was no longer a discernible line running north to south that, Turner said, any longer divided civilization from savagery. Turner worried for the United States’ future: what would become of the nation without the safety valve of the frontier? It was a common sentiment. Theodore Roosevelt wrote to Turner that his essay “put into shape a good deal of thought that has been floating around rather loosely.”

The history of the West was many-sided and it was made by many persons and peoples. Turner’s thesis was rife with faults, not only its bald Anglo Saxon chauvinism—in which non-whites fell before the march of “civilization” and Chinese and Mexican immigrants were invisible—but in its utter inability to appreciate the impact of technology and government subsidies and large-scale economic enterprises alongside the work of hardy pioneers. Still, Turner’s thesis held an almost canonical position among historians for much of the twentieth century and, more importantly, captured Americans’ enduring romanticization of the West and the simplification of a long and complicated story into a march of progress.

This chapter was edited by Lauren Brand, with content contributions by Lauren Brand, Carole Butcher, Josh Garrett-Davis, Tracey Hanshew, Nick Roland, David Schley, Emma Teitelman, and Alyce Vigil.

- American Yawp. Located at : http://www.americanyawp.com/index.html . Project : American Yawp. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

17.9: The West as History- the Turner Thesis

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 10013

- American YAWP

- Stanford via Stanford University Press

.png?revision=1)

In 1893, the American Historical Association met during that year’s World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The young Wisconsin historian Frederick Jackson Turner presented his “frontier thesis,” one of the most influential theories of American history, in his essay “The Significance of the Frontier in American History.”

Turner looked back at the historical changes in the West and saw, instead of a tsunami of war and plunder and industry, waves of “civilization” that washed across the continent. A frontier line “between savagery and civilization” had moved west from the earliest English settlements in Massachusetts and Virginia across the Appalachians to the Mississippi and finally across the Plains to California and Oregon. Turner invited his audience to “stand at Cumberland Gap [the famous pass through the Appalachian Mountains], and watch the procession of civilization, marching single file—the buffalo following the trail to the salt springs, the Indian, the fur trader and hunter, the cattle-raiser, the pioneer farmer—and the frontier has passed by.” 26

Americans, Turner said, had been forced by necessity to build a rough-hewn civilization out of the frontier, giving the nation its exceptional hustle and its democratic spirit and distinguishing North America from the stale monarchies of Europe. Moreover, the style of history Turner called for was democratic as well, arguing that the work of ordinary people (in this case, pioneers) deserved the same study as that of great statesmen. Such was a novel approach in 1893.

But Turner looked ominously to the future. The Census Bureau in 1890 had declared the frontier closed. There was no longer a discernible line running north to south that, Turner said, any longer divided civilization from savagery. Turner worried for the United States’ future: what would become of the nation without the safety valve of the frontier? It was a common sentiment. Theodore Roosevelt wrote to Turner that his essay “put into shape a good deal of thought that has been floating around rather loosely.” 27

The history of the West was many-sided and it was made by many persons and peoples. Turner’s thesis was rife with faults, not only in its bald Anglo-Saxon chauvinism—in which nonwhites fell before the march of “civilization” and Chinese and Mexican immigrants were invisible—but in its utter inability to appreciate the impact of technology and government subsidies and large-scale economic enterprises alongside the work of hardy pioneers. Still, Turner’s thesis held an almost canonical position among historians for much of the twentieth century and, more importantly, captured Americans’ enduring romanticization of the West and the simplification of a long and complicated story into a march of progress.

- AHA Communities

- Buy AHA Merchandise

- Cookies and Privacy Policy

In This Section

- Brief History of the AHA

- Annual Reports

- Year in Review

- Historical Archives

- Presidential Addresses

- GI Roundtable Series

- National History Center

The Significance of the Frontier in American History (1893)

By Frederick J. Turner, 1893

Editor's Note: Please note, this is a short version of the essay subsequently published in Turner's essay collection, The Frontier in American History (1920). This text is closer to the original version delivered at the 1893 meeting of the American Historical Association in Chicago, published in Annual Report of the American Historical Association , 1893, pp. 197–227.

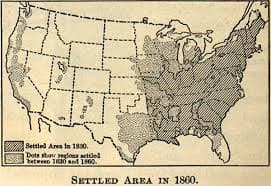

In a recent bulletin of the Superintendent of the Census for 1890 appear these significant words: “Up to and including 1880 the country had a frontier of settlement, but at present the unsettled area has been so broken into by isolated bodies of settlement that there can hardly be said to be a frontier line. In the discussion of its extent, its westward movement, etc., it can not, therefore, any longer have a place in the census reports.” This brief official statement marks the closing of a great historic movement. Up to our own day American history has been in a large degree the history of the colonization of the Great West. The existence of an area of free land, its continuous recession, and the advance of American settlement westward, explain American development.

Behind institutions, behind constitutional forms and modifications, lie the vital forces that call these organs into life and shape them to meet changing conditions. The peculiarity of American institutions is, the fact that they have been compelled to adapt themselves to the changes of an expanding people—to the changes involved in crossing a continent, in winning a wilderness, and in developing at each area of this progress out of the primitive economic and political conditions of the frontier into the complexity of city life. Said Calhoun in 1817, “We are great, and rapidly—I was about to say fearfully—growing!” 1 So saying, he touched the distinguishing feature of American life. All peoples show development; the germ theory of politics has been sufficiently emphasized. In the case of most nations, however, the development has occurred in a limited area; and if the nation has expanded, it has met other growing peoples whom it has conquered. But in the case of the United States we have a different phenomenon. Limiting our attention to the Atlantic coast, we have the familiar phenomenon of the evolution of institutions in a limited area, such as the rise of representative government; the differentiation of simple colonial governments into complex organs; the progress from primitive industrial society, without division of labor, up to manufacturing civilization. But we have in addition to this a recurrence of the process of evolution in each western area reached in the process of expansion. Thus American development has exhibited not merely advance along a single line, but a return to primitive conditions on a continually advancing frontier line, and a new development for that area. American social development has been continually beginning over again on the frontier. This perennial rebirth, this fluidity of American life, this expansion westward with its new opportunities, its continuous touch with the simplicity of primitive society, furnish the forces dominating American character. The true point of view in the history of this nation is not the Atlantic coast, it is the great West. Even the slavery struggle, which is made so exclusive an object of attention by writers like Prof. von Holst, occupies its important place in American history because of its relation to westward expansion.

In this advance, the frontier is the outer edge of the wave—the meeting point between savagery and civilization. Much has been written about the frontier from the point of view of border warfare and the chase, but as a field for the serious study of the economist and the historian it has been neglected.

The American frontier is sharply distinguished from the European frontier—a fortified boundary line running through dense populations. The most significant thing about the American frontier is, that it lies at the hither edge of free land. In the census reports it is treated as the margin of that settlement which has a density of two or more to the square mile. The term is an elastic one, and for our purposes does not need sharp definition. We shall consider the whole frontier belt, including the Indian country and the outer margin of the “settled area” of the census reports. This paper will make no attempt to treat the subject exhaustively; its aim is simply to call attention to the frontier as a fertile field for investigation, and to suggest some of the problems which arise in connection with it.

In the settlement of America we have to observe how European life entered the continent, and how America modified and developed that life and reacted on Europe. Our early history is the study of European germs developing in an American environment. Too exclusive attention has been paid by institutional students to the Germanic origins, too little to the American factors. The frontier is the line of most rapid and effective Americanization. The wilderness masters the colonist. It finds him a European in dress, industries, tools, modes of travel, and thought. It takes him from the railroad car and puts him in the birch canoe. It strips off the garments of civilization and arrays him in the hunting shirt and the moccasin. It puts him in the log cabin of the Cherokee and Iroquois and runs an Indian palisade around him. Before long he has gone to planting Indian corn and plowing with a sharp stick; he shouts the war cry and takes the scalp in orthodox Indian fashion. In short, at the frontier the environment is at first too strong for the man. He must accept the conditions which it furnishes, or perish, and so he fits himself into the Indian clearings and follows the Indian trails. Little by little he transforms the wilderness; but the outcome is not the old Europe, not simply the development of Germanic germs, any more than the first phenomenon was a case of reversion to the Germanic mark. The fact is, that here is a new product that is American. At first, the frontier was the Atlantic coast. It was the frontier of Europe in a very real sense. Moving westward, the frontier became more and more American. As successive terminal moraines result from successive glaciations, so each frontier leaves its traces behind it, and when it becomes a settled area the region still partakes of the frontier characteristics. Thus the advance of the frontier has meant a steady movement away from the influence of Europe, a steady growth of independence on American lines. And to study this advance, the men who grew up under these conditions, and the political, economic, and social results of it, is to study the really American part of our history.

Stages of Frontier Advance

In the course of the seventeenth century the frontier was advanced up the Atlantic river courses, just beyond the “fall line,” and the tidewater region became the settled area. In the first half of the eighteenth century another advance occurred. Traders followed the Delaware and Shawnese Indians to the Ohio as early as the end of the first quarter of the century. 2 Gov. Spotswood, of Virginia, made an expedition in 1714 across the Blue Ridge. The end of the first quarter of the century saw the advance of the Scotch-Irish and the Palatine Germans up the Shenandoah Valley into the western part of Virginia, and along the Piedmont region of the Carolinas. 3 The Germans in New York pushed the frontier of settlement up the Mohawk to German Flats. 4 In Pennsylvania the town of Bedford indicates the line of settlement. Settlements had begun on New River, a branch of the Kanawha, and on the sources of the Yadkin and French Broad. 5 The King attempted to arrest the advance by his proclamation of 1763, 6 forbidding settlements beyond the sources of the rivers flowing into the Atlantic; but in vain. In the period of the Revolution the frontier crossed the Alleghanies into Kentucky and Tennessee, and the upper waters of the Ohio were settled. 7 When the first census was taken in 1790, the continuous settled area was bounded by a line which ran near the coast of Maine, and included New England except a portion of Vermont and New Hampshire, New York along the Hudson and up the Mohawk about Schenectady, eastern and southern Pennsylvania, Virginia well across the Shenandoah Valley, and the Carolinas and eastern Georgia. 8 Beyond this region of continuous settlement were the small settled areas of Kentucky and Tennessee, and the Ohio, with the mountains intervening between them and the Atlantic area, thus giving a new and important character to the frontier. The isolation of the region increased its peculiarly American tendencies, and the need of transportation facilities to connect it with the East called out important schemes of internal improvement, which will be noted farther on. The “West,” as a self-conscious section, began to evolve.

From decade to decade distinct advances of the frontier occurred. By the census of 1820, 9 the settled area included Ohio, southern Indiana and Illinois, southeastern Missouri, and about one-half of Louisiana. This settled area had surrounded Indian areas, and the management of these tribes became an object of political concern. The frontier region of the time lay along the Great Lakes, where Astor’s American Fur Company operated in the Indian trade, 10 and beyond the Mississippi, where Indian traders extended their activity even to the Rocky Mountains; Florida also furnished frontier conditions. The Mississippi River region was the scene of typical frontier settlements. 11

The rising steam navigation 12 on western waters, the opening of the Erie Canal, and the westward extension of cotton 13 culture added five frontier states to the Union in this period. Grund, writing in 1836, declares: “It appears then that the universal disposition of Americans to emigrate to the western wilderness, in order to enlarge their dominion over inanimate nature, is the actual result of an expansive power which is inherent in them, and which by continually agitating all classes of society is constantly throwing a large portion of the whole population on the extreme confines of the State, in order to gain space for its development. Hardly is a new State or Territory formed before the same principle manifests itself again and gives rise to a further emigration; and so is it destined to go on until a physical barrier must finally obstruct its progress.” 14

In the middle of this century the line indicated by the present eastern boundary of Indian Territory, Nebraska, and Kansas marked the frontier of the Indian country. 15 Minnesota and Wisconsin still exhibited frontier conditions, 16 but the distinctive frontier of the period is found in California, where the gold discoveries had sent a sudden tide of adventurous miners, and in Oregon, and the settlements in Utah. 17 As the frontier has leaped over the Alleghanies, so now it skipped the Great Plains and the Rocky Mountains; and in the same way that the advance of the frontiersmen beyond the Alleghanies had caused the rise of important questions of transportation and internal improvement, so now the settlers beyond the Rocky Mountains needed means of communication with the East, and in the furnishing of these arose the settlement of the Great Plains and the development of still another kind of frontier life. Railroads, fostered by land grants, sent an increasing tide of immigrants into the far West. The United States Army fought a series of Indian wars in Minnesota, Dakota, and the Indian Territory.

By 1880 the settled area had been pushed into northern Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota, along Dakota rivers, and in the Black Hills region, and was ascending the rivers of Kansas and Nebraska. The development of mines in Colorado had drawn isolated frontier settlements into that region, and Montana and Idaho were receiving settlers. The frontier was found in these mining camps and the ranches of the Great Plains. The superintendent of the census for 1890 reports, as previously stated, that the settlements of the West lie so scattered over the region that there can no longer be said to be a frontier line.

In these successive frontiers we find natural boundary lines which have served to mark and to affect the characteristics of the frontiers, namely: The “fall line;” the Alleghany Mountains; the Mississippi; the Missouri, where its direction approximates north and south; the line of the arid lands, approximately the ninety-ninth meridian; and the Rocky Mountains. The fall line marked the frontier of the seventeenth century; the Alleghanies that of the eighteenth; the Mississippi that of the first quarter of the nineteenth; the Missouri that of the middle of this century (omitting the California movement); and the belt of the Rocky Mountains and the arid tract, the present frontier. Each was won by a series of Indian wars.

The Frontier Furnishes a Field for Comparative Study of Social Development

At the Atlantic frontier one can study the germs of processes repeated at each successive frontier. We have the complex European life sharply precipitated by the wilderness into the simplicity of primitive conditions. The first frontier had to meet its Indian question, its question of the disposition of the public domain, of the means of intercourse with older settlements, of the extension of political organization, of religious and educational activity. And the settlement of these and similar questions for one frontier served as a guide for the next. The American student needs not to go to the “prim little townships of Sleswick” for illustrations of the law of continuity and development. For example, he may study the origin of our land policies in the colonial land policy; he may see how the system grew by adapting the statutes to the customs of the successive frontiers. 18 He may see how the mining experience in the lead regions of Wisconsin, Illinois, and Iowa was applied to the mining laws of the Rockies, 19 and how our Indian policy has been a series of experimentations on successive frontiers. Each tier of new States has found in the older ones material for its constitutions. 20 Each frontier has made similar contributions to American character, as will be discussed farther on.

But with all these similarities there are essential differences, due to the place element and the time element. It is evident that the farming frontier of the Mississippi Valley presents different conditions from the mining frontier of the Rocky Mountains. The frontier reached by the Pacific Railroad, surveyed into rectangles, guarded by the United States Army, and recruited by the daily immigrant ship, moves forward at a swifter pace and in a different way than the frontier reached by the birch canoe or the pack horse. The geologist traces patiently the shores of ancient seas, maps their areas, and compares the older and the newer. It would be a work worth the historian’s labors to mark these various frontiers and in detail compare one with another. Not only would there result a more adequate conception of American development and characteristics, but invaluable additions would be made to the history of society.

Loria, 21 the Italian economist, has urged the study of colonial life as an aid in understanding the stages of European development, affirming that colonial settlement is for economic science what the mountain is for geology, bringing to light primitive stratifications. “America,” he says, “has the key to the historical enigma which Europe has sought for centuries in vain, and the land which has no history reveals luminously the course of universal history.” There is much truth in this. The United States lies like a huge page in the history of society. Line by line as we read this continental page from west to east we find the record of social evolution. It begins with the Indian and the hunter; it goes on to tell of the disintegration of savagery by the entrance of the trader, the pathfinder of civilization; we read the annals of the pastoral stage in ranch life; the exploitation of the soil by the raising of unrotated crops of corn and wheat in sparsely settled farming communities; the intensive culture of the denser farm settlement; and finally the manufacturing organization with city and factory system. 22 This page is familiar to the student of census statistics, but how little of it has been used by our historians. Particularly in eastern States this page is a palimpsest. What is now a manufacturing State was in an earlier decade an area of intensive farming. Earlier yet it had been a wheat area, and still earlier the “range” had attracted the cattle-herder. Thus Wisconsin, now developing manufacture, is a State with varied agricultural interests. But earlier it was given over to almost exclusive grain-raising, like North Dakota at the present time.

Each of these areas has had an influence in our economic and political history; the evolution of each into a higher stage has worked political transformations. But what constitutional historian has made any adequate attempt to interpret political facts by the light of these social areas and changes? 23

The Atlantic frontier was compounded of fisherman, far trader, miner, cattle-raiser, and farmer. Excepting the fisherman, each type of industry was on the march toward the West, impelled by an irresistible attraction. Each passed in successive waves across the continent. Stand at Cumberland Gap and watch the procession of civilization, marching single file—the buffalo following the trail to the salt springs, the Indian, the fur-trader and hunter, the cattle-raiser, the pioneer farmer—and the frontier has passed by. Stand at South Pass in the Rockies a century later and see the same procession with wider intervals between. The unequal rate of advance compels us to distinguish the frontier into the trader’s frontier, the rancher’s frontier, or the miner’s frontier, and the farmer’s frontier. When the mines and the cow pens were still near the fall line the traders’ pack trains were tinkling across the Alleghanies, and the French on the Great Lakes were fortifying their posts, alarmed by the British trader’s birch canoe. When the trappers scaled the Rockies, the farmer was still near the mouth of the Missouri.

The Indian Trader’s Frontier

Why was it that the Indian trader passed so rapidly across the continent? What effects followed from the trader’s frontier? The trade was coeval with American discovery, The Norsemen, Vespuccius, Verrazani, Hudson, John Smith, all trafficked for furs. The Plymouth pilgrims settled in Indian cornfields, and their first return cargo was of beaver and lumber. The records of the various New England colonies show how steadily exploration was carried into the wilderness by this trade. What is true for New England is, as would be expected, even plainer for the rest of the colonies. All along the coast from Maine to Georgia the Indian trade opened up the river courses. Steadily the trader passed westward, utilizing the older lines of French trade. The Ohio, the Great Lakes, the Mississippi, the Missouri, and the Platte, the lines of western advance, were ascended by traders. They found the passes in the Rocky Mountains and guided Lewis and Clarke, 24 Fremont, and Bidwell. The explanation of the rapidity of this advance is connected with the effects of the trader on the Indian. The trading post left the unarmed tribes at the mercy of those that had purchased fire-arms—a truth which the Iroquois Indians wrote in blood, and so the remote and unvisited tribes gave eager welcome to the trader. “The savages,” wrote La Salle, “take better care of us French than of their own children; from us only can they get guns and goods.” This accounts for the trader’s power and the rapidity of his advance. Thus the disintegrating forces of civilization entered the wilderness. Every river valley and Indian trail became a fissure in Indian society, and so that society became honeycombed. Long before the pioneer farmer appeared on the scene, primitive Indian life had passed away. The farmers met Indians armed with guns. The trading frontier, while steadily undermining Indian power by making the tribes ultimately dependent on the whites, yet, through its sale of guns, gave to the Indians increased power of resistance to the farming frontier. French colonization was dominated by its trading frontier; English colonization by its farming frontier. There was an antagonism between the two frontiers as between the two nations. Said Duquesne to the Iroquois, “Are you ignorant of the difference between the king of England and the king of France? Go see the forts that our king has established and you will see that you can still hunt under their very walls. They have been placed for your advantage in places which you frequent. The English, on the contrary, are no sooner in possession of a place than the game is driven away. The forest falls before them as they advance, and the soil is laid bare so that you can scarce find the wherewithal to erect a shelter for the night.”

And yet, in spite of this opposition of the interests of the trader and the farmer, the Indian trade pioneered the way for civilization. The buffalo trail became the Indian trail, and this because the trader’s “trace;” the trails widened into roads, and the roads into turnpikes, and these in turn were transformed into railroads. The same origin can be shown for the railroads of the South, the far West, and the Dominion of Canada. 25 The trading posts reached by these trails were on the sites of Indian villages which had been placed in positions suggested by nature; and these trading posts, situated so as to command the water systems of the country, have grown into such cities as Albany, Pittsburg, Detroit, Chicago, St. Louis, Council Bluffs, and Kansas City. Thus civilization in America has followed the arteries made by geology, pouring an ever richer tide through them, until at last the slender paths of aboriginal intercourse have been broadened and interwoven into the complex mazes of modern commercial lines; the wilderness has been interpenetrated by lines of civilization growing ever more numerous. It is like the steady growth of a complex nervous system for the originally simple, inert continent. If one would understand why we are to-day one nation, rather than a collection of isolated states, he must study this economic and social consolidation of the country. In this progress from savage conditions lie topics for the evolutionist. 26

The effect of the Indian frontier as a consolidating agent in our history is important. From the close of the seventeenth century various intercolonial congresses have been called to treat with Indians and establish common measures of defense. Particularism was strongest in colonies with no Indian frontier. This frontier stretched along the western border like a cord of union. The Indian was a common danger, demanding united action. Most celebrated of these conferences was the Albany congress of 1754, called to treat with the Six Nations, and to consider plans of union. Even a cursory reading of the plan proposed by the congress reveals the importance of the frontier. The powers of the general council and the officers were, chiefly, the determination of peace and war with the Indians, the regulation of Indian trade, the purchase of Indian lands, and the creation and government of new settlements as a security against the Indians. It is evident that the unifying tendencies of the Revolutionary period were facilitated by the previous cooperation in the regulation of the frontier. In this connection may be mentioned the importance of the frontier, from that day to this, as a military training school, keeping alive the power of resistance to aggression, and developing the stalwart and rugged qualities of the frontiersman.

The Rancher’s Frontier

It would not be possible in the limits of this paper to trace the other frontiers across the continent. Travelers of the eighteenth century found the “cowpens” among the canebrakes and peavine pastures of the South, and the “cow drivers” took their droves to Charleston, Philadelphia, and New York. 27 Travelers at the close of the War of 1812 met droves of more than a thousand cattle and swine from the interior of Ohio going to Pennsylvania to fatten for the Philadelphia market. 28 The ranges of the Great Plains, with ranch and cowboy and nomadic life, are things of yesterday and of to-day. The experience of the Carolina cowpens guided the ranchers of Texas. One element favoring the rapid extension of the rancher’s frontier is the fact that in a remote country lacking transportation facilities the product must be in small bulk, or must be able to transport itself, and the cattle raiser could easily drive his product to market. The effect of these great ranches on the subsequent agrarian history of the localities in which they existed should be studied.

The Farmer’s Frontier

The maps of the census reports show an uneven advance of the farmer’s frontier, with tongues of settlement pushed forward and with indentations of wilderness. In part this is due to Indian resistance, in part to the location of river valleys and passes, in part to the unequal force of the centers of frontier attraction. Among the important centers of attraction may be mentioned the following: fertile and favorably situated soils, salt springs, mines, and army posts.

The frontier army post, serving to protect the settlers from the Indians, has also acted as a wedge to open the Indian country, and has been a nucleus for settlement. 29 In this connection mention should also be made of the Government military and exploring expeditions in determining the lines of settlement. But all the more important expeditions were greatly indebted to the earliest pathmakers, the Indian guides, the traders and trappers, and the French voyageurs, who were inevitable parts of governmental expeditions from the days of Lewis and Clarke. 30 Each expedition was an epitome of the previous factors in western advance.

Salt Springs

In an interesting monograph, Victor Hehn 31 has traced the effect of salt upon early European development, and has pointed out how it affected the lines of settlement and the form of administration. A similar study might be made for the salt springs of the United States. The early settlers were tied to the coast by the need of salt, without which they could not preserve their meats or live in comfort. Writing in 1752, Bishop Spangenburg says of a colony for which he was seeking lands in North Carolina, “They will require salt & other necessaries which they can neither manufacture nor raise. Either they must go to Charleston, which is 300 miles distant * * * Or else they must go to Boling’s Point in Va on a branch of the James & is also 300 miles from here * * * Or else they must go down the Roanoke—I know not how many miles—where salt is brought up from the Cape Fear.” 32 This may serve as a typical illustration. An annual pilgrimage to the coast for salt thus became essential. Taking flocks or furs and ginseng root, the early settlers sent their pack trains after seeding time each year to the coast. 33 This proved to be an important educational influence, since it was almost the only way in which the pioneer learned what was going on in the East. But when discovery was made of the salt springs of the Kanawha, and the Holston, and Kentucky, and central New York, the West began to be freed from dependence on the coast. It was in part the effect of finding these salt springs that enabled settlement to cross the mountains.

From the time the mountains rose between the pioneer and the seaboard, a new order of Americanism arose. The West and the East began to get out of touch of each other. The settlements from the sea to the mountains kept connection with the rear and had a certain solidarity. But the overmountain men grew more and more independent. The East took a narrow view of American advance, and nearly lost these men. Kentucky and Tennessee history bears abundant witness to the truth of this statement. The East began to try to hedge and limit westward expansion. Though Webster could declare that there were no Alleghanies in his politics, yet in politics in general they were a very solid factor.

The exploitation of the beasts took hunter and trader to the west, the exploitation of the grasses took the rancher west, and the exploitation of the virgin soil of the river valleys and prairies attracted the farmer. Good soils have been the most continuous attraction to the farmer’s frontier. The land hunger of the Virginians drew them down the rivers into Carolina, in early colonial days; the search for soils took the Massachusetts men to Pennsylvania and to New York. As the eastern lands were taken up migration flowed across them to the west. Daniel Boone, the great backwoodsman, who combined the occupations of hunter, trader, cattle-raiser, farmer, and surveyor—learning, probably from the traders, of the fertility of the lands on the upper Yadkin, where the traders were wont to rest as they took their way to the Indians, left his Pennsylvania home with his father, and passed down the Great Valley road to that stream. Learning from a trader whose posts were on the Red River in Kentucky of its game and rich pastures, he pioneered the way for the farmers to that region. Thence he passed to the frontier of Missouri, where his settlement was long a landmark on the frontier. Here again he helped to open the way for civilization, finding salt licks, and trails, and land. His son was among the earliest trappers in the passes of the Rocky Mountains, and his party are said to have been the first to camp on the present site of Denver. His grandson, Col. A. J. Boone, of Colorado, was a power among the Indians of the Rocky Mountains, and was appointed an agent by the Government. Kit Carson’s mother was a Boone. 34 Thus this family epitomizes the backwoodsman’s advance across the continent.

The farmer’s advance came in a distinct series of waves. In Peck’s New Guide to the West, published in Boston in 1837, occurs this suggestive passage:

Generally, in all the western settlements, three classes, like the waves of the ocean, have rolled one after the other. First comes the pioneer, who depends for the subsistence of his family chiefly upon the natural growth of vegetation, called the “range,” and the proceeds of hunting. His implements of agriculture are rude, chiefly of his own make, and his efforts directed mainly to a crop of corn and a “truck patch.” The last is a rude garden for growing cabbage, beans, corn for roasting ears, cucumbers, and potatoes. A log cabin, and, occasionally, a stable and corn-crib, and a field of a dozen acres, the timber girdled or “deadened,” and fenced, are enough for his occupancy. It is quite immaterial whether he ever becomes the owner of the soil. He is the occupant for the time being, pays no rent, and feels as independent as the “lord of the manor.” With a horse, cow, and one or two breeders of swine, he strikes into the woods with his family, and becomes the founder of a new county, or perhaps state. He builds his cabin, gathers around him a few other families of similar tastes and habits, and occupies till the range is somewhat subdued, and hunting a little precarious, or, which is more frequently the case, till the neighbors crowd around, roads, bridges, and fields annoy him, and he lacks elbow room. The preemption law enables him to dispose of his cabin and cornfield to the next class of emigrants; and, to employ his own figures, he “breaks for the high timber,” “clears out for the New Purchase,” or migrates to Arkansas or Texas, to work the same process over.

The next class of emigrants purchase the lands, add field to field, clear out the roads, throw rough bridges over the streams, put up hewn log houses with glass windows and brick or stone chimneys, occasionally plant orchards, build mills, schoolhouses, court-houses, etc., and exhibit the picture and forms of plain, frugal, civilized life.