Improve your writing in one of the largest and most successful writing groups online

Join our writing community!

Types of Poetry: The Complete Guide with 28 Examples

by Fija Callaghan

Poetry has been around for almost four thousand years, predating even written language, and it’s still evolving all the time. Let’s explore some of the different types of poems you might come across, including rhymed poetry and free verse poetry, and how experimenting with a poem’s structure can make you a better poet.

Why do the different forms of poetry matter?

Poetic forms are important when we write poems for three main reasons:

1. Forms make poetry easier to remember

At its inception, poetry was used as a way to pass down stories and ideas to new generations. Poetry has been around longer than the written word, but even after people started writing things down, some cultures continued telling stories orally. They did this by telling stories as poems. Using set rhyme schemes, meters, and rhythms made it easier to learn those poems by heart.

2. Form shapes the rhythm and sound of a poem

Using poetic structure helps shape the way a poem will sound when it’s spoken out loud. Even though most of our poetry today is written down, it’s still heard at live performances, and we’ll often “hear” a poem in our head as we’re reading it. Different types of poetry will have different auditory moods and rhythms, which contributes to the overall emotional effect.

3. Form challenges our use of language

As writers, we always want to be challenging ourselves to use words in new and exciting ways. Using the constraints of formal poetry is a great way to stretch our imagination and come up with new ideas. The story theorist Robert McKee calls this “creative limitation.” By imposing limits on what we can do, we’ll instinctively look for ever more creative and imaginative ways to use the limited space that we’re given.

Free verse poetry vs. rhymed poetry

These days, rhymed poetry has fallen out of vogue with contemporary poets, though it still has its champions. In the early 20th century free verse, or free form, poetry was embraced for its fluid, conversational qualities, and dominates the poetic landscape today. It became popular in part because it feels less like a performance and more like you’re talking directly to the reader.

Rhymed poetry, on the other hand, is great for getting a message across to the reader or listener. Most pop songs today are, at least in part, rhymed poetry—that’s why we remember them and find ourselves mulling over the lyrics days later.

We’ll look more at different types of free verse poetry and rhymed poetry, and you can see which ones work best for you.

27 Types of Poetry

You might recognize some of these types of poems from reading poetry like them in school (Edgar Allan Poe, William Shakespeare, and Walt Whitman are all names you’ve probably come across in English class!) Others might be new to you. Once you know a little bit more about these common forms (and some less common ones), you can even enjoy writing some of your own!

A haiku is a traditional cornerstone of Japanese poetry with no set rhyme scheme, but a specific shape: three lines composed of five syllables in the first line, seven in the second line, and five in the third line.

Occasionally, some traditional Japanese haiku won’t fit this format because the syllables change when they’re translated into English; but when you’re writing your own haiku poem in your native language, you should try to adhere to this structure.

Haiku poems are often explorations of the natural world, but they can be about anything you like. They’re deceptively simple ideas with a lot of poignancy under the surface.

Here’s an example of a haiku poem, “Over the Wintry” by Natsume Sōseki:

Over the wintry Forest, winds howl in rage With no leaves to blow.

Learn more about writing your own haiku poetry in our dedicated Academy article.

2. Limerick

A limerick is a short, famous poetic form consisting of five lines that follow the rhyme form AABBA. Usually these are quite funny and tell a story. The first two lines should have eight or nine syllables each, the third and fourth lines should have five or six syllables each, and the final line eight or nine syllables again.

Limericks are great learning devices for children because their rhythm makes them so easy to remember. Here’s a fun example of a limerick, “There Was A Small Boy Of Quebec” by Rudyard Kipling:

There was a small boy of Quebec, Who was buried in snow to his neck; When they said, “Are you friz?” He replied, “Yes, I is— But we don’t call this cold in Quebec.”

3. Clerihew

Clerihews are a little bit like limericks in that they’re short, funny, and often satirical. A clerihew is made up of four lines (or several four-line stanzas) with the rhyme scheme AABB, and the first line of the stanza must be a person’s name.

This poetry type is great for helping people remember things (or enacting some good-natured revenge). Here’s a famous example, “Sir Humphrey Davy” by Edmund Clerihew Bentley, the inventor of the eponymous clarihew:

Sir Humphrey Davy Abominated gravy. He lived in the odium Of having discovered sodium.

4. Cinquain

A cinquain is a five-line poem consisting of twenty-two syllables: two in the first line, then four, then six, then eight, and then two syllables again in the last line. These are deceptively simple poems with a lovely musicality that make the writer think hard about the perfect word choices.

Here’s an example of a cinquain poem, “November Night” by Adelaide Crapsey:

Listen… With faint dry sound, Like steps of passing ghosts, The leaves, frost-crisp’d, break from the trees And fall.

A triolet is a traditional French single-stanza poem of eight lines with a rhyme scheme of ABAAABAB; however, it only consists of five unique lines. The first line is repeated as the fourth and seventh line, and the second line is repeated as the very last line. Although simple, a well-written triolet will bring new depth and meaning to the repeated lines each time. Here’s an example of a classic triolet poem, “How Great My Grief” by Thomas Hardy:

How great my grief, my joys how few, Since first it was my fate to know thee! Have the slow years not brought to view How great my grief, my joys how few, Nor memory shaped old times anew, Nor loving-kindness helped to show thee How great my grief, my joys how few, Since first it was my fate to know thee?

A dizain is another traditional form made up of just one ten-line stanza, and with each line having ten syllables (that’s an even hundred in total). The rhyme scheme for a dizain is ABABBCCDCD. This poetry type was a favorite of French poets in the 15th and 16th century, and many English poets adapted it into larger works. Here’s an great example of a dizain poem, “Names” by Brad Osborne:

If true that a rose by another name Holds in its fine form fragrance just as sweet If vivid beauty remains just the same And if other qualities are replete With the things that make a rose so complete Why bother giving anything a name Then on whom may I place deserved blame When new people’s names I cannot recall There seems to be an underlying shame So why do we bother with names at all

A sonnet is a lyric poem that always has fourteen lines. The oldest type of sonnet is the Italian or Petrarchan sonnet, which is broken into two stanzas of eight lines and six lines. The first stanza has a consistent rhyme scheme of ABBA ABBA and the second stanza has a rhyme scheme of either CDECDE or CDCDCD.

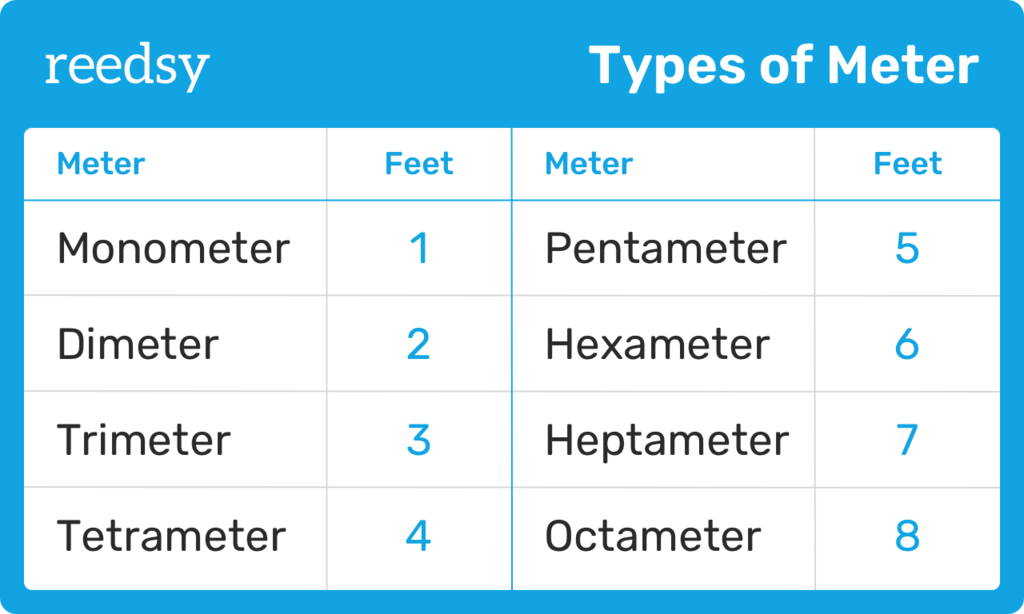

Later on, an ambitious bloke by the name of William Shakespeare developed the English sonnet (which later came to be known as the Shakespearean sonnet). It still has fourteen lines, but the rhyme scheme is different and it uses a rhythm called iambic pentameter. It has four distinctive parts, which might be separate stanzas or they might be all linked together. The rhyme scheme is ABAB CDCD EFEF GG.

William Shakespeare is famous for using iambic pentameter in his sonnets, but you can experiment with different rhythms and see what works best for you. Here’s one of his most famous sonnets, Sonnet 18:

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day? Thou art more lovely and more temperate: Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May, And summer’s lease hath all too short a date: Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines, And often is his gold complexion dimm’d; And every fair from fair sometime declines, By chance, or nature’s changing course, untrimm’d; But thy eternal summer shall not fade Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st; Nor shall Death brag thou wander’st in his shade, When in eternal lines to time thou grow’st; So long as men can breathe or eyes can see, So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

8. Blank verse

Blank verse is a type of poetry that’s written in a precise meter, usually iambic pentameter, but without rhyme. This is reminiscent of Shakespearean sonnets and many of his plays, but it reflects a movement that puts rhythm above rhyme.

Though each line of blank verse must be ten syllables, there’s no restriction on the amount of lines or individual stanzas. Here’s an excerpt from a poem in blank verse, the first stanza of “Frost at Midnight” by Samuel Taylor Coleridge:

The Frost performs its secret ministry, Unhelped by any wind. The owlet’s cry Came loud—and hark, again! loud as before. The inmates of my cottage, all at rest, Have left me to that solitude, which suits Abstruser musings: save that at my side My cradled infant slumbers peacefully. ’Tis calm indeed! so calm, that it disturbs And vexes meditation with its strange And extreme silentness. Sea, hill, and wood, This populous village! Sea, and hill, and wood, With all the numberless goings-on of life, Inaudible as dreams! the thin blue flame Lies on my low-burnt fire, and quivers not; Only that film, which fluttered on the grate

9. Villanelle

A villanelle is a type of French poem made up of nineteen lines grouped into six separate stanzas. The first five stanzas have three lines each, and the last stanza has four lines. Each three-line stanza rhymes ABA, and the last one ABAA.

Villanelles tend to feature a lot of repetition, which lends them a musical quality; usually the very first and third lines become the alternating last lines of each following stanza. This can be a bit like putting a puzzle together. Here’s an example to show you how it looks: “My Darling Turns to Poetry at Night,” a famous villanelle by Anthony Lawrence:

My darling turns to poetry at night. What began as flirtation, an aside Between abstract expression and first light Now finds form as a silent, startled flight Of commas on her face—a breath, a word… My darling turns to poetry at night. When rain inspires the night birds to create Rhyme and formal verse, stanzas can be made Between abstract expression and first light. Her heartbeat is a metaphor, a late Bloom of red flowers that refuse to fade. My darling turns to poetry at night. I watch her turn. I do not sleep. I wait For symbols, for a sign that fear has died Between abstract expression and first light. Her dreams have night vision, and in her sight Our bodies leave ghostprints on the bed. My darling turns to poetry at night Between abstract expression and first light.

10. Paradelle

The paradelle is a complex and demanding variation of the villanelle, developed in France in the 11th century… except it wasn’t. It was, in fact, a hoax developed in the 20th century that got drastically out of hand. The American poet Billy Collins invented the paradelle as a satire of the popular villanelle and, like many happy accidents, the paradelle was embraced as a welcome challenge and is now part of contemporary poetry’s repertoire.

A paradelle is composed of four six-line stanzas. In each of the first three stanzas, the first two lines must be the same, the second two lines must be the same, and the final two lines must contain every word from the first and third lines, and only those words, rearranged in a new order. The fourth and final stanza must contain every word from the fifth and sixth lines of the first three stanzas, and only those words, again rearranged in a new order.

11th-century relic or not, this poetry form is a great exercise for playing with words. Here’s an excerpt from the original paradelle that started it all, the first stanzas of “Paradelle for Susan” by Billy Collins:

I remember the quick, nervous bird of your love. I remember the quick, nervous bird of your love. Always perched on the thinnest highest branch. Always perched on the thinnest highest branch. Thinnest love, remember the quick branch. Always nervous, I perched on you highest bird the. It is time for me to cross the mountain. It is time for me to cross the mountain. And find another shore to darken with my pain. And find another shore to darken with my pain. Another pain for me to darken the mountain. And find the time, cross my shore, to with it is to. The weather warm, the handwriting familiar. The weather warm, the handwriting familiar. Your letter flies from my hand into the waters below. Your letter flies from my hand into the waters below. The familiar water below my warm hand. Into handwriting your weather flies you letter the from the. I always cross the highest letter, the thinnest bird. Below the waters of my warm familiar pain, Another hand to remember your handwriting. The weather perched for me on the shore. Quick, your nervous branch flew from love. Darken the mountain, time and find was my into it was with to to.

11. Sestina

A sestina is a complex French poetry form (a real one, this time) composed of thirty-nine lines in seven stanzas—six stanzas of six lines each, and one stanza of three lines. Each word at the end of each line in the first stanza then gets repeated at the end of each line in each following stanza, but in a different order.

Some poets use favorite metres or rhyme schemes in their sestina poems, but you don’t have to. The classic form of a sestina is:

First stanza: ABCDEF; each letter represents the word at the end of each line.

Second stanza: FAEBDC

Third stanza: CFDABE

Fourth stanza: ECBFAD

Fifth stanza: DEACFB

Sixth stanza: BDFECA

Seventh stanza: ACE or ECA

Here’s an excerpt from a modern example of a sestina, the first stanzas of “A Miracle For Breakfast” by Elizabeth Bishop. Looking at the first two stanzas, you can see that the repeated end words match the mixed-up letter guide above.

At six o’clock we were waiting for coffee, waiting for coffee and the charitable crumb that was going to be served from a certain balcony like kings of old, or like a miracle. It was still dark. One foot of the sun steadied itself on a long ripple in the river. The first ferry of the day had just crossed the river. It was so cold we hoped that the coffee would be very hot, seeing that the sun was not going to warm us; and that the crumb would be a loaf each, buttered, by a miracle. At seven a man stepped out on the balcony.

A rondel is a French type of poetry made of three stanzas: the first two are four lines long, and the third is five or six lines long. The first two lines of the poems are refrains which are repeated as the last two lines of the following two stanzas—although sometimes the poet will choose only one line to repeat at the very last line.

Rondels usually use a ABBA ABAB ABBAA rhyme scheme, but they can be written in any meter. Here’s an example of a traditional rondel poem, “The Wanderer” by Henry Austin Dobson:

Love comes back to his vacant dwelling— The old, old Love that we knew of yore! We see him stand by the open door, With his great eyes sad, and his bosom swelling. He makes as though in our arms repelling, He fain would lie as he lay before;— Love comes back to his vacant dwelling, The old, old Love that we knew of yore! Ah, who shall help us from over-spelling That sweet, forgotten, forbidden lore! E’en as we doubt in our heart once more, With a rush of tears to our eyelids welling, Love comes back to his vacant dwelling.

A ghazal is an old Arabic poetry form consisting of at least ten lines, but no more than thirty, all written in two-line stanzas called couplets. The first two lines of a ghazal end with the same word, but the words just preceding the last lines will rhyme. From this point on, the second line of each couplet will have the same last word, and the word just before it will rhyme with the others.

Ghazals are traditionally a poem of love and longing, but they can be written about any feeling or idea. Here’s an excerpt from a ghazal poem, the first stanzas of “Ghazal of the Better-Unbegun” by Heather McHugh:

Too volatile, am I? too voluble? too much a word-person? I blame the soup: I’m a primordially stirred person. Two pronouns and a vehicle was Icarus with wings. The apparatus of his selves made an absurd person. The sound I make is sympathy’s: sad dogs are tied afar. But howling I become an ever more unheard person.

14. Golden shovel

A golden shovel poem is a more recent poetry form that was developed by poet Terrance Hayes and inspired by Gwendolyn Brooks. Though it’s much newer than many of the types of poetry on this list, it has been enthusiastically embraced in contemporary poetry.

It’s a bit like an acrostic-style poem in that it hides a secret message: the last word of every line of a golden shovel poem is a word from another poem’s title or line, or a saying or headline you want to work with.

For example, if you want to write a golden shovel poem about the line, “dead men tell no tales,” the first line of your poem would end in “dead,” the second line in “men,” and so on until you can read your entire message along the right-hand side of the poem.

Here’s an excerpt from Terrance Hayes’s poem that started the golden shovel trend:

When I am so small Da’s sock covers my arm, we cruise at twilight until we find the place the real men lean, bloodshot and translucent with cool. His smile is a gold-plated incantation as we drift by women on bar stools, with nothing left in them but approachlessness. This is a school I do not know yet. But the cue sticks mean we are rubbed by light, smooth as wood, the lurk of smoke thinned to song. We won’t be out late.

15. Palindrome

Palindrome poems, also called “mirror poems,” are poems that begin repeating backwards halfway through, so that the first line and the last line are the same, the second line and the second-to-last line are the same, and so on.

They’re a challenging yet fun way to show two sides of the same story. Here’s an example of a palindrome poem, “On Reflection” by Kristin Bock:

Far from the din of the articulated world, I wanted to be content in an empty room— a barn on the hillside like a bone, a limbo of afternoons strung together like cardboard boxes, to be free of your image— crown of bees, pail of black water staggering through the pitiful corn. I can’t always see through it. The mind is a pond layered in lilies. The mind is a pond layered in lilies. I can’t always see through it staggering through the pitiful corn. Crown of Bees, Pail of Black Water, to be of your image— a limbo of afternoons strung together like cardboard boxes, a barn on the hillside like a bone. I wanted to be content in an empty room far from the din of the articulated world.

An ode is a poetic form of celebration used to honor a person, thing, or idea. They’re often overflowing with intense emotion and powerful imagery.

Odes can be used in conjunction with formal meters and rhyme schemes, but they don’t have to be; often poets will favor internal rhymes instead, to give their ode a sense of rhythm.

This is a more open-ended poetry type you can use to show your appreciation for something or someone. Here’s an excerpt from one of the most famous and beautiful odes, written in celebration of autumn: “To Autumn” by John Keats:

Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness, Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun; Conspiring with him how to load and bless With fruit the vines that round the thatch-eaves run; To bend with apples the mossed cottage-trees, And fill all fruit with ripeness to the core; To swell the gourd, and plump the hazel shells With a sweet kernel; to set budding more, And still more, later flowers for the bees, Until they think warm days will never cease, For Summer has o’er-brimmed their clammy cells.

An elegy is similar to an ode in that it celebrates a person or idea, but in this instance is the poem centers around something that has died or been lost.

There’s a tradition among poets to write elegies for one another once another poet has died. Sometimes these are obvious memoriams of a deceased person, and other times the true meaning will be hidden behind layers of symbolism and metaphor.

Like the ode, there’s no formal meter or rhyme scheme in an elegy, though you can certainly experiment with using them.

Here’s an excerpt of an elegy written by one poet for another, “In Memory of W. B. Yeats” by W. H. Auden:

He disappeared in the dead of winter: The brooks were frozen, the airports almost deserted, And snow disfigured the public statues; The mercury sank in the mouth of the dying day. What instruments we have agree The day of his death was a dark cold day. Far from his illness The wolves ran on through the evergreen forests, The peasant river was untempted by the fashionable quays; By mourning tongues The death of the poet was kept from his poems.

18. Ekphrasis

Ekphrastic poetry is a little bit like an ode, as it is also written in celebration of something. Ekphrasis, however, is very specific as it’s used to draw attention to a work of art—usually visual art, but it could be something like a song or a work of fiction too. Sometimes ekphrastic poems and odes can overlap, like in John Keats’ “Ode to a Grecian Urn”—an ekphrastic ode.

Ekphrastic poems are most often written about paintings, but it can also be about sculptures, dance, or even theatrical performances.

Ekphrasis has no set meter or rhyme scheme, but some poets like to use them. Here’s an excerpt from an ekphrastic poem, “The Starry Night” by Anne Sexton, in celebration of Van Gogh’s painting:

The town does not exist except where one black-haired tree slips up like a drowned woman into the hot sky. The town is silent. The night boils with eleven stars. Oh starry starry night! This is how I want to die. It moves. They are all alive. Even the moon bulges in its orange irons to push children, like a god, from its eye. The old unseen serpent swallows up the stars. Oh starry starry night! This is how I want to die.

19. Pastoral

Pastoral poetry can take any meter or rhyme scheme, but it focuses on the beauty of nature. These poems draw attention to idyllic settings and romanticize the idea of shepherds and agriculture laborers living in harmony with the natural world.

Often these traditional pastoral poems carry a religious overtone, suggesting that by bringing oneself closer to nature they were also becoming closer to their spirituality. They can be written in free verse, or in poetic structure. Here’s an excerpt from a famous pastoral poem, “The Passionate Shepherd to His Love” by Christopher Marlowe:

Come live with me and be my love, And we will all the pleasures prove That valleys, groves, hills, and fields, Woods, or steepy mountain yields. And we will sit upon the rocks, Seeing the shepherds feed their flocks, By shallow rivers to whose falls Melodious birds sing madrigals.

An epic poem is a grand, overarching story written in verse—they’re the novels of the poetry world. This is sometimes called ballad poetry, or narrative poetry. Before stories were written as novels and short stories and then, later, screenplays, all of our classic tales would be written as a narrative poem.

Experimenting with epic poems, such as writing a short story all in verse, is a great way to give your writer’s muscles a workout. These don’t have a specific rhyme scheme or metre, although many classic epic poems do use them to give a sense of rhythm and unity to the piece.

Here’s an excerpt from one of our oldest surviving epic poems, “Beowulf,” translated from old English by Frances B. Gummere:

Lo, praise of the prowess of people-kings of spear-armed Danes, in days long sped, we have heard, and what honor the athelings won! Oft Scyld the Scefing from squadroned foes, from many a tribe, the mead-bench tore, awing the earls. Since erst he lay friendless, a foundling, fate repaid him: for he waxed under welkin, in wealth he throve, till before him the folk, both far and near, who house by the whale-path, heard his mandate, gave him gifts: a good king he!

(Irish poet Seamus Heaney has also completed an even more modern translation for the layperson.)

A ballad is similar to an epic in that it tells a story, but it’s much shorter and a bit more structured. This poetry form is made up of four-line stanzas (as many as are needed to tell the story) with a rhyme scheme of ABCB.

Ballads were originally meant to be set to music, which is where we get the idea of our slow, sultry love song ballads today. A lot of traditional ballads are all in dialogue, where two characters are speaking back and forth.

Here’s an excerpt from a traditional ballad poem, “La Belle Dame sans Merci” by John Keats:

O what can ail thee, knight-at-arms, Alone and palely loitering? The sedge has withered from the lake, And no birds sing. O what can ail thee, knight-at-arms, So haggard and so woe-begone? The squirrel’s granary is full, And the harvest’s done.

22. Acrostic

In acrostic poems, certain letters of each line spell out a word or message. Usually the letters that spell the message will be the first letter of each line, so that you can read the secret word right down the margin; however, you can also use the letters at the end or down the middle of the lines to hide a secret message. Acrostic poems are especially popular with children and are sometimes called “name poems.”

Here’s an example of an acrostic poem, “A Boat Beneath a Sunny Sky” by Lewis Carroll. The first letter of each line spells out “Alice Pleasance Liddell,” who was a young friend of Carroll’s and the inspiration behind Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland .

A boat beneath a sunny sky, L ingering onward dreamily I n an evening of July— C hildren three that nestle near, E ager eye and willing ear, P leased a simple tale to hear— L ong has paled that sunny sky: E choes fade and memories die: A utumn frosts have slain July. S till she haunts me, phantomwise, A lice moving under skies N ever seen by waking eyes. C hildren yet, the tale to hear, E ager eye and willing ear, L ovingly shall nestle near. I n a Wonderland they lie, D reaming as the days go by, D reaming as the summers die: E ver drifting down the stream— L ingering in the golden gleam— L ife, what is it but a dream?

23. Concrete

A concrete poem, sometimes called a shape poem, is a visual poem structure where the shape of the poem resembles its content or message. These are another favorite with children, although they can be used to communicate powerful adult ideas, too.

When writing concrete poetry, you can experiment with different fonts, sizes, and even colors to create your visual poem. Here’s an example of a concrete poem, “Sonnet in the Shape of a Potted Christmas Tree” by George Starbuck:

* O fury- bedecked! O glitter-torn! Let the wild wind erect bonbonbonanzas; junipers affect frostyfreeze turbans; iciclestuff adorn all cuckolded creation in a madcap crown of horn! It’s a new day; no scapegrace of a sect tidying up the ashtrays playing Daughter-in-Law Elect; bells! bibelots! popsicle cigars! shatter the glassware! a son born now now while ox and ass and infant lie together as poor creatures will and tears of her exertion still cling in the spent girl’s eye and a great firework in the sky drifts to the western hill.

24. Prose poem

A prose poem combines elements of both prose writing and poetry into something new. Prose poems don’t have shape and line breaks in the way that traditional poems do, but they make use of poetic devices like meter, internal rhyme, alliteration, metaphor, imagery, and symbolism to create a snapshot of prose that reads and feels like a poem.

Here’s an example of a prose poem, “Be Drunk” by Charles Baudelaire:

You have to be always drunk. That’s all there is to it—it’s the only way. So as not to feel the horrible burden of time that breaks your back and bends you to the earth, you have to be continually drunk. But on what? Wine, poetry or virtue, as you wish. But be drunk. And if sometimes, on the steps of a palace or the green grass of a ditch, in the mournful solitude of your room, you wake again, drunkenness already diminishing or gone, ask the wind, the wave, the star, the bird, the clock, everything that is flying, everything that is groaning, everything that is rolling, everything that is singing, everything that is speaking… ask what time it is and wind, wave, star, bird, clock will answer you: “It is time to be drunk! So as not to be the martyred slaves of time, be drunk, be continually drunk! On wine, on poetry or on virtue as you wish.”

25. Found poetry

Found poetry is a poem made up of a composite of external quotations. This may be from poems, beloved works of literature, newspaper articles, instruction manuals, or political manifestos. You can copy out pieces of text, or you can cut out different words to make a visual collage effect.

Another form of found poetry is blackout poetry, where words are crossed out and removed from an external source to create a new meaning.

These can be a great way to find new or contrasting meaning in everyday life, but always be sure to reference what sources your poem came from originally to avoid plagiarism. Here’s an example of a found poem, “Testimony” by Charles Reznikoff, cut up from law reports between 1885 and 1915:

Amelia was just fourteen and out of the orphan asylum; at her first job—in the bindery, and yes sir, yes ma’am, oh, so anxious to please. She stood at the table, her blond hair hanging about her shoulders, “knocking up” for Mary and Sadie, the stichers (“knocking up” is counting books and stacking them in piles to be taken away).

A nonce poem is a DIY poem structure intended for one-time use to challenge yourself as a writer, or just to try something new. It’s a formal, rigid, standardized poetry form that’s brand new to the world.

For example, you might say, “I’m going to write a poem starting with a three-line stanza, then two four-line stanzas, then another three-line stanza, and each line is going to be eight syllables except the first and last line of the poem which are each going to have eleven syllables, and the last word of every stanza will be true rhymes and the first word of every stanza will be slant rhymes.” And then you do it, just to see if you can.

Nonce poems are a great way to stretch your creativity and language skills to their limit. Then, like Terrance Hayes’s “Golden Shovel,” or Billy Collins’ “Paradelle,” your nonce poem might even catch on! Here’s an excerpt from a nonce poem, “And If I Did, What Then?” by George Gascoigne:

Are you aggriev’d therefore? The sea hath fish for every man, And what would you have more?” Thus did my mistress once, Amaze my mind with doubt; And popp’d a question for the nonce To beat my brains about.

27. Free verse

Free verse is the type of poetry most favored by contemporary poets; it has no set meter, rhyme scheme, or structure, but allows the poet to feel out the content of the poem as they go.

Poets will often still use rhythmic literary devices such as assonance and internal rhymes, but it won’t be bound up with the same creative restraints as more structured poetry. However, even poets that work solely in free verse will usually argue that it’s beneficial to first work up your mastery of language through exercises in more structured poetry forms.

Here’s an example of a poem in free verse, an excerpt from “On Turning Ten,” by Billy Collins:

The whole idea of it makes me feel like I’m coming down with something, something worse than any stomach ache or the headaches I get from reading in bad light— a kind of measles of the spirit, a mumps of the psyche, a disfiguring chicken pox of the soul.

3 ways poem structure will make you a better writer

Maybe you’ve fallen in love with formal rhymed poetry, or maybe you think that for you, free verse is the way to go. Either way, it’s good training for a writer to experiment with poetry structure for a few different reasons.

1. Using poetic form will teach you about poetic devices

Using poetic form will open up your world to a huge range of useful poetic devices like assonance, chiasmus, and epistrophe, as well as broader overarching ideas like metaphor, imagery, and symbolism. We talk about these poetic devices a lot in poetry forms, but just about all of them can be used effectively in prose writing, too!

Paying attention to poetic form takes your mastery of language to a whole new level. Then you can take this skill set and apply it to your writing in a whole range of mediums.

2. Writing poems with structure teaches you how to use rhythm

Rhythm is one of the core concepts of all poetry. Rhymes and formal meter are two ways to capture rhythm in your poems, but even in free verse poetry that lacks a formal poetic structure, the key to good poetry is a smooth and addictive rhythm that makes you feel the words in your bones.

Once you start experimenting with poetry forms, you’ll find that you’ll develop an inner ear for the rhythm of language. This rhythmic sense translates into beautiful sentence structure and cadence in other types of writing, from short stories and novels, to marketing copy, to comic books. Rhythm is what makes your words a joy to read.

3. Formal poetry helps you increase your vocabulary and refine your word choice

No matter what you’re writing, specificity is a game changer when it comes to getting a point across to your reader. With the English language being well-populated with nice, easy syllables, many new writers fall into the bad habit of choosing words that are just kind of okay, instead of the exact right word for that moment.

Writing formal poetry forces you to not only expand your vocabulary to find the right word to fit the rhyme scheme or rhythm, but to weigh each word and examine it from all angles before awarding it a place in your poem. This way, when you move into other forms of writing, you’ll carry good habits and a deep respect for language into your work.

Start writing different types of poetry

Learning about different types of poems for the first time can be a bit like opening a floodgate into a whole new way of living. Whether you prefer free verse poetry, lyric poetry, romantic Shakespearean sonnets, short philosophical haiku, or even coming up with your own nonce poetry structure, you’ll find that writing poetry challenges your writer’s muscles in ways you never would have expected. Next time you’re in a creative rut, trying experimenting with poetry forms to get the words flowing in a whole new way.

Get feedback on your writing today!

Scribophile is a community of hundreds of thousands of writers from all over the world. Meet beta readers, get feedback on your writing, and become a better writer!

Join now for free

Related articles

Poetic Devices List: 27 Main Poetic Devices with Examples

How to Write a Haiku (With Haiku Examples)

Short Story Submissions: How to Publish a Short Story or Poem

9 Types Of Poems To Spark Your Creativity

Poetry styles to fit your style

On January 20, 2021, 22-year-old youth poet laureate Amanda Gorman inspired the country and made history when she read her poem “The Hill We Climb” at the inauguration of the 46th President of the United States, Joe Biden. Gorman’s free verse poem touched on themes of unity, hope, and progress; it encouraged Americans to continue working toward a “union with purpose.” (If you don’t know what “free verse” means, don’t worry—we will cover that on the next slide.)

Gorman is the youngest known inaugural poet, and her moving reading of “The Hill We Climb” ignited a newfound interest in poetry, often considered an obscure form of writing. To many, poetry can seem daunting because it’s so different from prose. But there is no wrong way to read a poem . If you find a poem that you connect with, even if you’re not sure what it is “supposed to” mean, you’re reading it right!

To help demystify poetry a bit, and in celebration of National Poetry Month, we are going to break down some of the different kinds or forms of poetry. Along the way, we are going to show you some classic examples of these poems and give you some guidance on how you can write poetry yourself—any day of the year.

Listening to Gorman’s performance of her poem is just one way to garner curiosity in poetry. Learn some fantastic ways to get your child (and yourself) excited about poetry!

If you watched Amanda Gorman’s performance, you may have noticed that it sounded very similar to typical speech patterns. That isn’t so surprising for free verse poems, or “verse that does not follow a fixed metrical pattern.” In other words, it doesn’t have to follow any of the strict rules about syllables , rhyme , or cadence that we will see in other forms. But, that doesn’t mean it doesn’t use any of these elements. It just means that the writer can choose which of them they want to use. Basically, every free verse poem uses its own unique structure.

Free verse is a popular and common form of poetry. In addition to “The Hill We Climb,” other famous free verse poems include “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” by T.S. Eliot and “Daddy” by Sylvia Plath. Perhaps the most famous American free verse poem, though, is “Song of Myself” by Walt Whitman (1892), which begins:

I celebrate myself, and sing myself, And what I assume you shall assume, For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.

I loafe and invite my soul, I lean and loafe at my ease observing a spear of summer grass.

My tongue, every atom of my blood, form’d from this soil, this air, Born here of parents born here from parents the same, and their parents the same, I, now thirty-seven years old in perfect health begin, Hoping to cease not till death.

Creeds and schools in abeyance, Retiring back a while sufficed at what they are, but never forgotten, I harbor for good or bad, I permit to speak at every hazard, Nature without check with original energy.

As you can see from this excerpt, the lines here don’t rhyme, and there isn’t a pattern in the length of the lines or how many lines there are to a stanza (group of lines). Try reading it aloud (or listen to dulcet -toned Nate DiMeo read it to you here ) and see how much it sounds like a conversation the narrator is having with himself.

slam poetry

Another poetry form that does not follow strict rules is slam poetry . Slam poetry is free-form poetry designed to be performed aloud. The name comes from poetry competitions known as “poetry slams.” In this way, slam poetry is a kind of performance art . In fact, Amanda Gorman’s recitation of “The Hill We Climb” had a lot of slam poetry elements, including hand gestures to punctuate and emphasize important moments in the text.

Slam poetry gets its inspiration from the beat poets and French-speaking Négritude poets who wanted their work to protest the conventional, European forms of poetry. Throughout its history, slam poetry has been associated with forms of activism and giving voice to those who have been historically marginalized.

Slam poetry is designed to be watched and listened to, not read. One classic example is “Falling in Like,” by Big Poppa E. You can read a short excerpt of this poem about young love below, but we recommend you watch him perform it here instead.

you make me feel… goofy.

goofy like i blush when someone mentions your name.

goofy like i have a bzillion things i wanna tell you when you’re not around, but face-to-face i just stare at my toe making circles on the ground, like i’m all thumbs and no place to put them, like i just wanna write you a note that says:

do you like me? ? yes ? no ? maybe

You probably noticed that this poem doesn’t use proper spelling, capitalization, or punctuation, and even has some unusual elements like checkboxes. That’s the thing about slam poetry —you can be as creative as you want with it. If you’re worried that you won’t be able to follow the rules of the other forms (or simply don’t want to), slam poetry is a great place to start writing. The only limit is your imagination!

Want to know more about slam poetry ? Visit our article on getting a close look at the full experience of slam poetry .

In a lot of ways, slam poetry is the modern incarnation of the ode . Originally, an ode was “a poem intended to be sung.” Today, an ode is “a lyric poem typically of elaborate or irregular metrical form and expressive of exalted or enthusiastic emotion.” A lyric poem is a poem that expresses personal feelings or emotion. (The name comes from the instrument the lyre , which was played to accompany these poems in their original form.)

Perhaps the most famous example of an ode is “Ode on a Grecian Urn” by John Keats (1819). In the poem, the narrator describes the images on an ancient Greek urn , which he uses as a way to express his feelings about art in general.

A more accessible ode might be “Ode on Solitude” by Alexander Pope (1700), in which the narrator talks about his desire to live the simple life, alone:

Happy the man, whose wish and care A few paternal acres bound, Content to breathe his native air, In his own ground.

Whose herds with milk, whose fields with bread, Whose flocks supply him with attire, Whose trees in summer yield him shade, In winter fire.

This ode happens to use a specific rhyming pattern and meter, but there are no requirements that your ode has to. In ancient Greek literature, odes were seven stanzas of five lines of 10 syllables. As you can see from our example from Pope here, that form is no longer a requirement. However, if you want to try writing your own ode , you might want to start with the ancient Greek format, because other ode structures can become quite complicated.

We just talked about types of poetry that don’t necessarily have any specific requirements when it comes to rhyme, meter, or anything else. So, let’s pause for a moment and ask ourselves, “Why do some forms of poetry follow strict rules? Why not just write in whatever way we choose, like in free verse or slam poetry ?”

Well, some poets actually find that the rules of certain forms of poetry inspire creativity. In a sense, having a structure gives you a place to start—staring at a blank page can be daunting for any writer! So ironically, having rules can give you more freedom to express yourself.

One classic form that has specific rules is the sonnet . A sonnet is a poem of 14 lines usually written in iambic pentameter . Iambic pentameter is a line of 10 syllables, with every other syllable stressed. (An iamb is an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable, like “mo tion ” or “I ate .”)

The most famous sonnets are those written by Shakespeare , like the one that begins “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day? Thou art more lovely and more temperate.”

One of our favorite sonnets is “Nuns Fret Not At Their Convent’s Narrow Room” by William Wordsworth. What is wonderful about this poem is that it explains how the strict rules of the sonnet give the narrator “ solace ” (comfort).

Nuns fret not at their convent’s narrow room; And hermits are contented with their cells; And students with their pensive citadels; Maids at the wheel, the weaver at his loom, Sit blithe and happy; bees that soar for bloom, High as the highest Peak of Furness-fells, Will murmur by the hour in foxglove bells: In truth the prison, unto which we doom Ourselves, no prison is: and hence for me, In sundry moods, ’twas pastime to be bound Within the Sonnet’s scanty plot of ground; Pleased if some Souls (for such there needs must be) Who have felt the weight of too much liberty, Should find brief solace there, as I have found.

Another classic form of poetry is the ballad . Similar to the ode , ballads were originally designed to be sung. A ballad is “a simple narrative poem of folk origin, composed in short stanzas and adapted for singing.” Usually, ballads tell a story or recount a series of events. They are often considered one of the easiest kinds of “formal” poetry to write.

A classic ballad is typically written in four-line stanzas (a quatrain ) that follow some kind of rhyming pattern, although the specific pattern can depend on the poem. Generally, though, ballads use the rhyme scheme ABCB, meaning the second and final lines of each stanza rhyme, and the first and third lines of the stanza do not rhyme. Ballads also generally use iambic tetrameter, meaning a line of eight syllables, alternating with iambic trimeter, a line of six syllables.

“The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” by Samuel Coleridge (1834) is one of the best-known ballads . It doesn’t follow the classic ballad form exactly, but you can get a sense of what ballads are all about from this excerpt:

It is an ancient Mariner, And he stoppeth one of three. ‘By thy long grey beard and glittering eye, Now wherefore stopp’st thou me?

The Bridegroom’s doors are opened wide, And I am next of kin; The guests are met, the feast is set: May’st hear the merry din.’

As you might have noticed, the lines alternate between eight syllables and six syllables, so it is a little different from a classic ballad . But you could certainly imagine these lines being put to music, right?

An enthralling speech can be pure poetry as well, especially if it uses poetic devices. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech is a prime example—find out why!

Villanelle isn’t just the name of the elusive hitwoman in the TV crime drama Killing Eve . It’s also a poetic form. A villanelle is a fancy ballad that follows these rules:

- Five stanzas of three lines each, followed by a single stanza of four lines.

- The stanzas of three lines each use an ABA rhyme (the first and last line rhyme).

- The final stanza uses an ABAA rhyme.

- The first line of the poem is repeated at the end of the second and fourth stanzas.

- The third line of the poem is repeated at the end of the third and fifth stanzas.

Likely the most famous villanelle of all time is “Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night” by Dylan Thomas (1951). You can get a sense of the rhyme scheme and the repeated lines from this excerpt here:

Do not go gentle into that good night, Old age should burn and rave at close of day; Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Though wise men at their end know dark is right, Because their words had forked no lightning they Do not go gentle into that good night.

As you can see from this example, the first line, “Do not go gentle into that good night,” is repeated at the end of the second stanza.

Villanelles are a little more challenging to write than a typical ballad. If the rhyme schemes and repetition seem like altogether too many rules for you, you may be more interested in…

The haiku form comes from Japanese poetic traditions. It’s closely associated with the 17th-century poet Matsuo Bash?. These short poems have a simple structure: the first and last line have five syllables, and the second line has seven syllables. Traditionally, these poems were “often on the subject of nature or one of the seasons,” but you can write a haiku about anything!

The most famous Bash? haiku is:

an ancient pond a frog jumps in the splash of water

Lovely, right? As you might have noticed, these lines don’t have any kind of rhyme scheme; there is just a simple syllable pattern. (The 5-7-5 pattern is there in the original Japanese.)

If you’re a total novice to writing poetry, haiku is a great place to start. Another relatively simple form of poetry to write is…

Limericks are funny, often raunchy, poems that follow the following form:

- Five lines that follow the AABBA rhyming pattern (the first, second, and fifth lines rhyme, and the third and fourth lines rhyme).

- The third and fourth lines are typically shorter than the other lines.

- On the third and fourth lines, the rhythm is two short syllables followed by a long one ( anapest ).

- On the other lines, the rhythm is short syllable, long syllable, short syllable ( amphibrach ).

All those notes about rhythm might seem daunting, but don’t worry about them too much. The most important thing is to stick to the AABBA rhyming pattern. Additionally, limericks often begin:

There was a [something] from [somewhere]…

One classic limerick that spawned countless (sometimes dirty) imitations was written by Dayton Voorhees (1902):

There once was a man from Nantucket Who kept all his cash in a bucket. But his daughter, named Nan, Ran away with a man And as for the bucket, Nantucket.

If you’re really feeling stuck with your limerick, you can take inspiration from this one—like many poets before you—and start with the same first line.

blackout poetry

If you’re not interested in, or feel daunted by, the practice of writing poetry, you might find the contemporary and innovative form of blackout poetry (also known as found poetry ) more appealing. It’s one of the most accessible forms of poetry out there.

All you need to start is a piece of paper with writing on it—a newspaper, a recipe, a page from a book—and a black marker. Then, as the creator of blackout poetry, Austin Kleon, puts it, “cross out words, leaving behind the ones you like.”

The result is a poem consisting of words that stand out on the page in contrast to the black of the marker. It’s striking, both poetically and visually. Blackout poetry is especially appealing because people of all ages can easily try their hand at it, like in this example:

Blackout Poetry continued… Ss poems are starting to take shape and we’re discovering that this is harder than it looks! If you have an old book at home, we highly recommend you try blackout poetry too! ?? @AllenbyPS_TDSB pic.twitter.com/1WvLDyg38N — Mme.Bedder (@MmeBedder) March 17, 2021

As we’ve seen, poetry can take many forms—it’s just a matter of what you’re looking for. Whether you feel inspired to write poetry yourself, or merely take the time to read a few poems every now again, don’t worry about getting it “right.” Just try to stay curious, be gentle with yourself, and remain open to multiple meanings. After all, as American poet Mary Oliver once wrote, “a poem on the page speaks to the listening mind.”

Ways To Say

Synonym of the day

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

4.29: Lesson 14: Form in Poetry

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 87434

Patterns in Poetry

Some poems come in specific patterns–a specific form, such as sonnets, villanelles, and concrete poems. These forms have specific rules that the poet must follow.

The sonnet is written in iambic pentameter. What’s that? It’s a specific rhythm. Each line has ten syllables with five pairs of iambs. Iambs are an unstressed syllable paired with a stressed syllable, so it will have the beat like this:

daDA / daDA / daDA / daDA / daDA

The Shakespearean sonnet has fourteen lines with a specific rhyme pattern. Each pair of words that rhymes alternate a line for the first 12 lines. For example, Line 1 and Line 3 end in a rhyme, and Line 2 and Line 4 end in a rhyme. The last two lines have their own rhyme. The rhyme scheme looks like this:

a b a b c d c d e f e f g g

Read William Shakespeare’s sonnet “Shall I Compare Thee to a Summer Day?” Look at the specific traits of the form: the iambic pentameter rhythm and the rhyme scheme.

Shall I Compare Thee to a Summer Day Author : William Shakespeare ©1598

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day? Thou art more lovely and more temperate: Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May, And summer’s lease hath all too short a date: Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines, And often is his gold complexion dimm’d, And every fair from fair sometime declines, By chance, or nature’s changing course untrimm’d: But thy eternal summer shall not fade, Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st, Nor shall death brag thou wander’st in his shade, When in eternal lines to time thou grow’st, So long as men can breathe, or eyes can see, So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

Other types of sonnets include the Petrarchan, a fourteen-line sonnet with the rhyme scheme of abba, abba, cde, cde.

Blank Verse

Blank verse is a poem that does not rhyme, but it has five stressed beats per line.

The villanelle contains five stanzas with three lines each, which is called tercets. The sixth stanza has four lines, which is called a quatrain. The total number of lines needed for a villanelle is 19 lines.

The villanelle also has two repeating lines. The first line in the first stanza repeats in the sixth, twelfth, and eighteenth lines. The third line in the first stanza repeats in the ninth, fifteenth, and nineteenth lines.

The villanelle follows this rhyme scheme: aba, aba, aba, aba, aba, abaa.

Check out this form in Dylan Thomas’ poem “Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night.”

Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night Author : Dylan Thomas ©1951

Concrete Poetry

Concrete poetry, also called visual poetry, takes on the shape of the topic being written about. The lines and words are typed specifically to create a design and enhance the meaning. For example, read and study the format of George Herbert’s poem “Easter Wings.”

Easter Wings Author : George Herbert ©1633

Free verse poetry has no form, meaning it has no stressed beats per line. This is the most common type of poetry that is written today.

- Lesson 14: Form in Poetry. Authored by : Linda Frances Lein. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Sonnet 18: Shall I Compare Thee to a Summer Day?. Authored by : William Shakespeare. Provided by : Wikisource. Located at : https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Sonnet_18_(Shakespeare) . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night. Authored by : Dylan Thomas. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Villanelle . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Easter Wings. Authored by : George Herbert. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Easter_Wings . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Let’s Read a Poem! What Type of Poetry Boosts Creativity?

Małgorzata osowiecka.

1 Warsaw Faculty of Psychology, SWPS University of Social Sciences and Humanities, Warsaw, Poland

Alina Kolańczyk

2 Faculty in Sopot, SWPS University of Social Sciences and Humanities, Sopot, Poland

Associated Data

Datasets are available upon request. The raw data supporting the conclusions of this manuscript will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

Poetry is one of the most creative uses of language. Yet the influence of poetry on creativity has received little attention. The present research aimed to determine how the reception of different types of poetry affect creativity levels. In two experimental studies, participants were assigned to two conditions: poetry reading and non-poetic text reading. Participants read poems (Study 1 = narrative/open metaphors; Study 2 = descriptive/conventional metaphors) or control pieces of non-poetic text. Before and after the reading manipulation, participants were given a test to determine levels of divergent thinking (DT; i.e., fluency, flexibility, and originality). Additionally, in both studies, the impact of frequent contact with poetry was examined. In Study 1 ( N = 107), participants showed increased fluency and flexibility after reading a narrative poem, while participants who read the non-poetic text showed a decrease in fluency and originality. In Study 2 ( N = 131) reception of conventional, closed metaphorization significantly lowered fluency and flexibility of thinking (compared to reading non-poetic text). The most critical finding was that poetry exposure could either increase or decrease creativity level depending on the type of poetic metaphors and style of poetic narration. Furthermore, results indicate that long-term exposure to poetry is associated with creativity. This interest in poetry can be explained by an ability to immerse oneself in a poetry content (i.e., a type of empathy) and the need for cognitive stimulation. Thus, this paper contributes a new perspective on exposure to poetry in the context of creativity and discusses possible individual differences that may affect how this type of art is received. However, future research is necessary to examine these associations further.

Introduction

Creativity is often understood in different ways. In an elitist view, creativity means eminent works of art created by great, gifted artists. In contrast, creativity has also been described as a common cognitive process, which can be improved ( Finke et al., 1992 ). This more popular approach has been labeled by Csikszentmihalyi (1996) as “little c Creativity." Previous research ( Mednick, 1962 ) has shown that creative thinking is based on flatter concept hierarchies, enabling remote associations to be more easily made. Csikszentmihalyi states that this kind of creativity is part of everyday human life, and can be observed even in young children. This type of “common" creativity results in more efficient problem solving, better performance on tasks measuring creative potential, and can even bring about the production of outstanding works of art. The current research concentrates on “little c Creativity," which can be improved by specific interventions under specific circumstances, and then observed and measured ( Guilford, 1950 ; Finke et al., 1992 ; Runco, 1999 ).

In this article, we examined whether the creative potential of a poem can be beneficial for receivers by testing whether one-time reception of poetry can influence the quality of divergent thinking (DT; i.e., multidirectional and/or potentially creative thinking). Additionally, we investigated if this impact depends on the type of poetic metaphors and/or the style of poetic narration.

There are several studies that have examined how humans produce metaphors ( Paivio, 1979 ; Chiappe and Chiappe, 2007 ; Silvia and Beaty, 2012 ; Beaty and Silvia, 2013 ), but little is known about metaphor comprehension, especially within the context of poetry. This research has inspired many books that attempt to teach the skills necessary to generate imaginative and interesting metaphors (e.g., Plotnik, 2007 ). It may be that the ability to associate remote ideas, facts, and elements of the environment, which is a key factor in metaphor production, may also be a key factor in creativity. Thus, these skills that can be taught to improve metaphorization may also overlap with skills to improve general creative ability.

Most psychological research on poetry has focused on the influence of text structure (i.e., rhythm, rhymes) on emotional reception of poems (e.g., Jakobson, 1960 ; Turner and Pöppel, 1983 ; Lerdahl, 2001 ; Obermeier et al., 2013 ). Additionally, many studies that have focused on poets’ creativity have also collected data revealing links between mental disorders and functioning (e.g., Stirman and Pennebaker, 2001 ; Djikic et al., 2006 ). Further, previous research has also examined the relationship between poetic training and creativity (e.g., Baer, 1996 ; Andonovska-Trajkovska, 2008 ; Cheng et al., 2010 ). However, the current manuscript focuses on the influence of poems as creative products that may affect receivers’ levels of creative thinking. This influence, however, likely depends on the type of poetry received.

The efficiency of DT is a key measure of idea generation (e.g., Baer, 1996 ; Runco, 1999 ; Nęcka, 2012 ). In contrast to convergent thinking, DT enables problem solving in diverse and potentially valuable ways. It often involves redefining the problem, referring to analogies, redirecting one’s thoughts, and breaking barriers in thinking. Previous research has found that spreading activation in the semantic network is indicative of DT ( Martindale, 1989 ; Ashton-James and Chartrand, 2009 ; Kaufman and Beghetto, 2009 ). Developing associations between distant ideas is a basic mechanism of creative thinking ( Mednick, 1962 ). For instance, Benedek et al. (2012) provided evidence that the ability to generate remote associations makes creative problem solving easier. Gilhooly et al. (2007) showed that ignoring close associations (but choosing remote ones) and breaking the stiff, typical relationships between ideas plays a crucial role in effective DT. The current studies are based on the hypothesis that the process of DT can be supported by poetry comprehension.

Poetry, which contains remote associations described through metaphors and analogies, combines non-related notions in atypical ways ( Lakoff and Johnson, 2003 ). In general, metaphoric expression often involves mapping between abstract and more concrete concepts ( Glucksberg, 2001 , 2003 ); therefore, the comprehension of metaphors requires the activation of a broader set of semantic associations. This is due to connecting two remote parts of a metaphor (theme and vehicle) into a meaningful expression ( Paivio, 1979 ; Kenett et al., 2018 ). Poetry reception can involve readiness to notice similarities between remote categories, which can be a crucial ability in generating creative ideas (e.g., Mednick, 1962 ; Koestler, 1964 ; Martindale, 1989 ). Training in metaphorical thinking results in the broadening of categories ( Nęcka and Kubiak, 1989 ), which leads to increased DT ( Trzebiński, 1981 ). Glucksberg et al. (1982) have shown that poetry reading broadens the scope of associations. Metaphor, based on remote associations, provides a new way of understanding reality and human feelings. In addition to fostering multidirectional and creative thinking, metaphor can also help individuals adjust to the surrounding world ( Kolańczyk, 1991 ; Nęcka, 2012 ). Metaphorization is, structurally, the most essential element of the poetic art (e.g., Lakoff and Johnson, 2003 ; Kovecses, 2010 ). Rhythm, syllabification, and word combinations in well-written poetry construct a meaningful whole aside from very remote notions ( Csikszentmihalyi, 1996 ). Thus, poetry comprehension can change readers’ DT; however, this impact likely depends on type of poetic metaphors and the narration used by the poet.

Thinking expressed in metaphors always involves the flexible activation and manipulation of acquired knowledge ( Benedek et al., 2014 ); even though metaphors are not always creative, even in poetry. Understanding a conventional metaphor is not intellectually challenging: comprehending such expressions is based on the retrieval of well-known meaning from memory ( Kenett et al., 2018 ). For example, love can be understood metaphorically as a nutrient. The metaphors “starved for affection” and “given strength by love” are not particularly creative, as they are based on a highly conventional metaphor (i.e., love = nutrient). These metaphors are ostensibly viewed as new by receivers of poetry, although they are not flexible or original. Hausman (1989) writes about two specific types of metaphors; one he describes as impoverished, frozen, and closed; the other, he refers to as original, divergent, and open. It seems logical to use terms like closed/convergent and open/divergent when referring to metaphors, which can emphasize a functional dimension of how these types of metaphors are used in poetry and casual language. To the best of our knowledge, however, previous research has never introduced this distinction in terms of differences between metaphors. Instead, Beaty and Silvia (2013) uses the metaphor labels conventional (i.e., familiar) and creative (i.e., novel).

Until now, no typologies of metaphors have been introduced that highlight differences in how poetry is constructed and how this impacts recipients. It seems that poetry uses at least these two kinds of metaphorization. Both of these can be adaptive for the recipient, because creativity requires both accommodation and assimilation ( Ayman-Nolley, 2010 ). Therefore, recipients’ reception of novel and open metaphors could result in more flexible and original thinking, whereas reception of conventional, well known, and closed metaphors could result in less flexible and less creative problem-solving.

In addition to the types of metaphors used, poetry is also characterized by content. One conceptualization of poetry describes it as a certain type of story, which is a separate and coherent whole, through which people express their thoughts and/or opinions ( Heiden, 2014 ). In this case, the author can bring an abstract idea closer to the reader through narrative imagery. This type of poetry can result in the receiver taking on another’s (i.e., the author’s) point of view, hence improving creativity. Moreover, this narrative type of poetry is an open task for readers, because understanding is reached based on the receiver’s own experience and understanding. The second type, noncreative poetry, is more conservative, and includes variously structured, commonplace (i.e., conventional) metaphors, which are often clichés based on common-sense regularities, and are sometimes the contents of parables or prayers. Metaphors in this type of poetry delineate and conventionalize meaning; they describe the world in ways known to everyone (e.g., Lakoff and Turner, 1989 ; Gibbs, 1994 ; Lakoff and Johnson, 2003 ; Kovecses, 2010 ).

The general goals of this research were to determine whether the reception of poetry stimulates creative thinking, and whether poetry’s impact on creativity varies depending on the type of poetry. Accordingly, we formulated the following research hypotheses:

- simple 1. Reception of an unconventional, open metaphor poem will stimulate the generation of creative ideas (i.e., improves DT from baseline).

- simple 2. Reception of conventional poetry either will not influence, or will negatively influence the generation of creative ideas (i.e., no increase or decrease in DT from baseline).

- simple 3. DT will be increased after the reception of open metaphor poetry, when compared to reading a neutral text.

- simple 4. DT will be decreased after reception of conventional poetry, when compared to a neutral text.

In Study 1, participants were exposed to a poem with narrative imagery expressing an author’s point of view and utilizing open metaphors. In Study 2, participants were exposed to a conventional poem that employed a biographical approach, comprised of commonplace metaphors and aphorisms.

Participants

Participants were recruited from high-school classes. All participants resided in Poland. A total of 107 participants completed the study ( M age = 17.46; SD = 1.03; 53 female). Students from the pool were randomly assigned to one of two groups. Upon entering the lab, participants were given a consent form and a brief explanation of the study procedures. The study was conducted in a group setting, with the number of participants ranging from 10 to 15. Participants provided written, informed consent, and were free to withdraw from the research at any time without giving reason or justification for withdrawing. Minors participated in research with written parental consent. Participants received points for behavior as compensation. Their participation was anonymous. The study was approved by a local ethics committee (clearance number: WKE/S 15/VI/1).

DT Measurement

To measure DT, participants were administered versions of the Question Generation task ( Chybicka, 2001 ). This task was conducted using a test-retest design (to observe creativity change). Participants listed as many questions as they could regarding an unambiguous picture (baseline image from Chybicka, 2001 ; post-test, a comparable version from Corbalan and Lopez, 1992 ). The fluency, flexibility, and the originality of answers were evaluated by three independent judges. Fluency was the total number of meaningful responses given by participant; flexibility (i.e., diversity of categories) was measured as the number of different categories; and originality was calculated as the number of original, novel, and interesting responses.

Poetry—Szymborska’s Poem

In Study 1, we chose Szymborska (2012) poem Utopia as an example of narrative, non-rhythmic poetry. In Utopia , Szymborska creates a sort of plot or story, which she conveys to the reader in a very metaphorical, condensed form. Szymborska’s narration in Utopia is characterized by ethical and metaphysical themes (e.g., “ As if all you can do here is leave and plunge, never to return, into the depths. Into unfathomable life & The Tree of Understanding, dazzlingly straight and simple, sprouts by the spring called Now I Get It” ). Six independent judges, all of which were Polish language teachers, filled in a short scale which contained three questions about affectivity of the chosen poem (e.g., “ the poem is neutral ”). They confirmed that the poem was emotionally stable, allowing for control over the influence of both rhythm and emotion on participants’ creativity.

Control Text

For the control text, we used the description of a cooking device (Speedcook, RPOL, Mielec, Poland). This description approximated the word count of a poem and did not contain any metaphors (e.g., “ Our kitchen appliance has a classic, elegant design. This device could replace every cooking appliance , a steam cooking tool, and a juicer” ). Device descriptions are often made according to the same pattern and in a comparable way. The description that we used contained close, functional associations between concepts. The text is constructed to provide concrete information to the recipient. The device description was obtained from an Internet website ( Wachowicz, 2014 ).

Contact With Poetry Scale

We developed a scale to measure poetry contact that addressed passion, as well as frequency of reading poetry and taking part in poetic meetings. Agreement/disagreement with statements was assessed. Statements included “ I am passionate about poetry,” “ In my free time, I very often read poems,” “ I write poems and share my work with others,” “I have several favorite poets,” “Sometimes, I put down my creative thoughts onto paper,” and “I was once an unpublished writer.” Participants answered the five items on a 5-point scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. The reliability of the tool, as measured by internal consistency, was satisfactory (Cronbach’s α = 0.83).

First, participants read introductory information highlighting the importance of their participation in the study and a confidentiality statement (assuring that participants would remain anonymous and encouraging them to answer all questions truthfully). Then, participants received the first version of the Question Generation Task ( Chybicka, 2001 ). Participants wrote questions about a picture printed on a piece of paper for 10 min. Next, participants were randomized into one of two groups: (a) the experimental group, which read the poem; or (b) the control group, which read the cooker description. Participants were instructed to silently read the poem twice, in a calm and attentive manner ( Kraxenberger and Menninghaus, 2016 ). After reading the text, participants answered two questions; one regarding understanding the content (“ I understand the meaning of the text”) and the other an affective estimation of the text (“ In my opinion, the text is pleasant ”). Items were rated on a 6-point scale, with response options ranging from 1 ( strongly disagree ) to 5 ( strongly agree ). Then, participants completed a parallel version of the drawing from the Question Generation Task ( Corbalan and Lopez, 1992 ). Finally, participants completed the devised scale concerning contact with poetry. Duration of the entire procedure was approximately 35 min. After completing the scale, participants were debriefed and thanked for their participation. We also collected postal addresses from participants who were interested in the results.

Data were analyzed using SPSS 24 (IBM, Armonk, NY, United States). The data from all participants were included in analyses and a significance level of p < 0.05 was adopted for all tests.

All three DT indicators were scored by three independent raters. A Kendall’s W of 1.00 was calculated for fluency at both time points; a W of 0.75 and 0.72 for flexibility in the first and the second measurement, respectively; and 0.76 for originality in both measurements ( W greater than 0.70 = good concordance). All indicators were analyzed separately via three repeated-measures analyses of variances (ANOVAs) with effect of measurement (first vs. second) as the within-subjects factor and group (poetry vs. description) as the between-subjects factor.

A 2 × 2 (measurement × group) repeated measures ANOVA for fluency revealed an interaction [ F (1,105) = 12.12, p < 0.001, η 2 = 0.1], but no main effects. Pairwise comparisons showed a significant improvement in fluency scores on the second measurement compared to the first in the poetry group [ t (56) = 2.57, p = 0.013; Cohen’s d = 0.35]. Moreover, the control group differed in fluency across the measurements. Specifically, participants in this group demonstrated significantly lower scores in the second measurement than in the first [ t (52) = 2.44, p = 0.018; Cohen’s d = 0.35]. Extended data are shown in Figure Figure1 1 .

Mean fluency scores in the poetry-reading group and description-reading group in the first and second measurement in Study 1. Error bars: 95% Confidence interval.

A 2 × 2 (measurement × group) repeated measures ANOVA for flexibility also revealed an interaction [ F (1,105) = 10.15, p < 0.01, η 2 = 0.09]. Further, a main effect of measurement was observed [ F (1,105) = 17.52, p < 0.001, η 2 = 0.14]. The second picture of the DT task led to more flexible answers ( M = 4.83, SD = 1.63) than did the first one ( M = 4.25, SD = 1.56). Two-tailed, paired t -tests for two measurements in the poetry group yielded significant differences [ t (56) = 5.47, p = 0.001; Cohen’s d = 0.75]. Extended data are presented in Figure Figure2 2 .

Mean flexibility scores in the poetry-reading group and description-reading group in the first and second measurement in Study 1. Error bars: 95% Confidence interval.

A 2 × 2 (measurement × group) repeated measures ANOVA for originality also revealed an interaction [ F (1,105) = 23.03, p = 0.01, η 2 = 0.18]. Additionally, a main effect of measurement was observed [ F (1,105) = 12.12, p < 0.01, η 2 = 0.11]. The first picture in the creativity test triggered more original answers ( M = 2.85, SD = 1.18) than did the second ( M = 2.34, SD = 1.71). Two-tailed paired t -tests yielded significant differences between the first and the second measurement only in the description group [ t (50) = 5.09, p < 0.001; Cohen’s d = 0.75]. Extended data are shown in Figure Figure3 3 .

Mean originality scores in the poetry-reading group and description-reading group in the first and second measurement in Study 1. Error bars: 95% Confidence interval.

To verify how individual differences in poetic interests are connected to DT, we also performed a linear regression analysis predicting DT on the first measurement (before the manipulation). As expected, flexibility was predicted by the level of poetic interests, F (1,56) = 3.29, p = 0.075, b = 0.24 (a near-significant trend). However, fluency and originality were not predicted by level of poetic interests. Further, no significant predictions were observed for the second measurement of creativity.

Results of the experiment support our hypotheses to a large extent, however, there are some issues that remain to be elucidated. Reading of poetry improved two creativity indicators (fluency and flexibility), while reading of the control (descriptive) text caused a decline in fluency and originality. Although these results are interesting, the question of why reading poetry does not improve originality remains. It is possible that reading this type of poetic narration introduces insufficient changes to the semantic network, so that individuals were unable to improve in the only indicator of product quality (i.e., originality). Additionally, flexibility did not decrease as a result of reading instructions. Likely because the cooker is compared with similar devices, which requires looking at it from different perspectives. Moreover, frequent contact with poetry predicted flexibility. These results suggest that the reception of narrative and open poetry broadens activation of the semantic network and allows for flexible switching between remote categories; however, it is not connected with the creation of very original solutions.