Self-Compassion and Body Image

- First Online: 24 March 2023

Cite this chapter

- Tracy L. Tylka 5 &

- Katarina L. Huellemann 6

Part of the book series: Mindfulness in Behavioral Health ((MIBH))

1847 Accesses

3 Altmetric

The study of self-compassion holds great relevance for body image theory, research, and practice. In this chapter, we review the various theoretical frameworks (i.e., tripartite influence model, objectification theory, social mentalities theory, and weight stigma theory) and research designs (meta-analytic, cross-sectional, prospective, and diary-based) researchers have used to explore the connection between self-compassion and body image. Evidence for self-compassion’s role as a predictor, moderator, and mediator has emerged. Specifically, self-compassion helps build and maintain positive body image and counteracts the development and persistence of body dissatisfaction. Next, we review various self-compassion interventions (i.e., meditations, writing tasks, a mobile application) and the research showing how these interventions improve participants’ positive body image and reduce their body dissatisfaction. We end the chapter with a discussion of opportunities for the next generation of research exploring self-compassion and body image.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Albertson, E. R., Neff, K. D., & Dill-Shackleford, K. E. (2015). Self-compassion and body dissatisfaction in women: A randomized controlled trial of a brief meditation intervention. Mindfulness, 6 (3), 444–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-014-0277-3

Article Google Scholar

Alleva, J. M., Sheeran, P., Webb, T. L., Martijn, C., & Miles, E. (2015). A meta-analytic review of stand-alone interventions to improve body image. PLoS One, 10 (9), e0139177. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0139177

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Alleva, J. M., Tylka, T. L., & Kroon Van Diest, A. M. (2017). The Functionality Appreciation Scale (FAS): Development and psychometric evaluation in U.S. community women and men. Body Image, 23 , 28–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2017.07.008

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Altman, J. K., Linfield, K., Salmon, P. G., & Beacham, A. O. (2017). The body compassion scale: Development and initial validation. Journal of Health Psychology . Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F1359105317718924

Andrew, R., Tiggemann, M., & Clark, L. (2016). Predicting body appreciation in young women: An integrated model of positive body image. Body Image, 18 , 34–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.04.003

Barnett, M. D., & Sharp, K. J. (2016). Maladaptive perfectionism, body image satisfaction, and disordered eating behaviors among U.S. college women: The mediating role of self-compassion. Personality and Individual Differences, 99 , 335–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.05.004

Bennett, E. V., Clarke, L. H., Kowalski, K. C., & Crocker, P. R. E. (2017). “I’ll do anything to maintain my health”: How women aged 65-94 perceive, experience, and cope with their aging bodies. Body Image, 21 , 71–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2017.03.002

Bowler, D. E., Buyung-Ali, L. M., Knight, T. M., & Pullin, A. S. (2010). A systematic review of the evidence for the added benefits to health of exposure to natural environments. BMC Public Health, 10 (1), 456. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-456

Braun, T. D., Park, C. L., & Gorin, A. (2016). Self-compassion, body image, and disordered eating: A review of the literature. Body Image, 17 , 117–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.03.003

Breines, J., Toole, A., Tu, C., & Chen, S. (2014). Self-compassion, body image, and self-reported disordered eating. Self and Identity, 13 (4), 432–448. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2013.838992

Calogero, R. M., & Pina, A. (2011). Body guilt: Preliminary evidence for a further subjective experience of self-objectification. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 35 (3), 428–440. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684311408564

Calogero, R. M., Tantleff-Dunn, S., & Thompson, J. K. (2011). Self-objectification in women: Causes, consequences, and counteractions . American Psychological Association.

Book Google Scholar

Cash, T. F. (2004). Body image: Past, present, and future. Body Image, 1 (1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1740-1445(03)00011-1

Cash, T. F., & Williams, E. F. (2005). Coping with body-image threats and challenges: Validation of the Body Image Coping Strategies Inventory. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 58 (2), 190–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.07.008

Comiskey, A., Parent, M. C., & Tebbe, E. A. (2020). An inhospitable world: Exploring a model of objectification theory with trans women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 44 (1), 105–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0361684319889595

Cox, A. E., Ullrich-French, S., Tylka, T. L., & McMahon, A. K. (2019). The roles of self-compassion, body surveillance, and body appreciation in predicting intrinsic motivation for physical activity: Cross-sectional association, and prospective changes within a yoga context. Body Image, 29 , 110–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.03.002

Crocker, J., Luhtanen, R. K., Cooper, M. L., & Bouvrette, A. (2003). Contingencies of self-worth in college students: Theory and measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85 (5), 894–908. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.5.894

Daye, C. A., Webb, J. B., & Jafari, N. (2014). Exploring self-compassion as a refuge against recalling the body-related shaming of caregiver eating messages on dimensions of objectified body consciousness in college women. Body Image, 11 (4), 547–556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.08.001

Dias, B. S., Ferreira, C., & Trindade, I. A. (2020). Influence of fears of compassion on body image shame and disordered eating. Eating and Weight Disorders, 25 (1), 99–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0523-0

Diener, E., & Diener, M. (1995). Cross-cultural correlates of life satisfaction and self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68 (4), 653–663. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.68.4.653

Fardouly, J., & Vartanian, L. R. (2015). Negative comparisons about one’s appearance mediate the relationship between Facebook usage and body image concerns. Body Image, 12 (1), 82–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.10.004

Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T.-A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21 (2), 173–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x

Garland, E. L., Fredrickson, B., Kring, A. M., Johnson, D. P., Meyer, P. S., & Penn, D. L. (2010). Upward spirals of positive emotions counter downward spirals of negativity: Insights from the broaden-and-build theory and affective neuroscience on the treatment of emotion dysfunctions and deficits in psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Review, 30 (7), 849–864. https://doi.org/10.1016/2Fj.cpr.2010.03.002

Gilbert, P. (2005). Compassion and cruelty: A biopsychosocial approach. In P. Gilbert (Ed.), Compassion: Conceptualisations, research and use in psychotherapy (pp. 9–74). Routledge.

Chapter Google Scholar

Gilbert, P. (2015). An evolutionary approach to emotion in mental health with a focus on affiliative emotions. Emotion Review, 7 (3), 230–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073915576552

Gilbert, P., & Irons, C. (2005). Focused therapies and compassionate mind training for shame and self-attacking. In P. Gilbert (Ed.), Compassion: Conceptualisations, research and use in psychotherapy (pp. 263–325). Routledge.

Gilbert, P., McEwan, K., Matos, M., & Rivis, A. (2011). Fears of self-compassion: Development of three self-report measures. Psychology and Psychotherapy, 84 (3), 239–255. https://doi.org/10.1348/147608310X526511

Grossbard, J. R., Lee, C. M., Neighbors, C., & Larimer, M. E. (2009). Body image concerns and contingent self-esteem in male and female college students. Sex Roles, 60 (3–4), 198–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-008-9535-y

Guest, E., Costa, B., Williamson, H., Meyrick, J., Halliwell, E., & Harcourt, D. (2019). The effectiveness of interventions aiming to promote positive body image in adults: A systematic review. Body Image, 30 , 10–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.04.002

Harter, S. (1999). The construction of the self: A developmental perspective . Guilford Press.

Google Scholar

Hazzard, V. M., Schaefer, L. M., Schaumberg, K., Bardone-Cone, A. M., Frederick, D. A., Klump, K. L., Anderson, D. A., & Thompson, J. K. (2019). Testing the tripartite influence model among heterosexual, bisexual, and lesbian women. Body Image, 30 , 145–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.07.001

Homan, K. J., & Tylka, T. L. (2015). Self-compassion moderates body comparison and appearance self-worth’s inverse relationships with body appreciation. Body Image, 15 , 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2015.04.007

Homan, K. J., & Tylka, T. L. (2018). Development and exploration of the gratitude model of body appreciation in women. Body Image, 25 , 14–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2018.01.008

Huellemann, K. L., & Calogero, R. M. (2020). Self-compassion and body checking among women: The mediating role of stigmatizing self-perceptions. Mindfulness, 11 (9), 2121–2130. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01420-8

James, W. (1890). Principles of psychology . Encyclopedia Britannica.

Josephs, R. A., Bosson, J. K., & Jacobs, C. G. (2003). Self-esteem maintenance processes: Why low self-esteem may be resistant to change. Personality and Social Psychology, 29 (7), 920–933. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0146167203029007010

Kelly, A. C., & Stephen, E. (2016). A daily diary study of self-compassion, body image, and eating behavior in female college students. Body Image, 17 , 152–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.03.006

Kelly, A. C., Vimalakanthan, K., & Carter, J. C. (2014a). Understanding the roles of self-esteem, self-compassion, and fear of self-compassion in eating disorder pathology: An examination of female students and eating disorder patients. Eating Behaviors, 15 (3), 388–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.04.008

Kelly, A. C., Vimalakanthan, K., & Miller, K. E. (2014b). Self-compassion moderates the relationship between body mass index and both eating disorder pathology and body image flexibility. Body Image, 11 (4), 446–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.07.005

Kelly, A. C., Miller, K. E., & Stephen, E. (2016). The benefits of being self-compassionate on days when interactions with body-focused others are frequent. Body Image, 19 , 195–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.10.005

Liss, M., & Erchull, M. J. (2015). Not hating what you see: Self-compassion may protect against negative mental health variables connected to self-objectification in college women. Body Image, 14 , 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2015.02.006

Lonergan, A. R., Bussey, K., Mond, J., Brown, O., Griffiths, S., Murray, S. B., & Mitchison, D. (2019). Me, my selfie, and I: The relationship between editing and posting selfies and body dissatisfaction in men and women. Body Image, 28 , 39–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2018.12.001

Lucas, R. E., Diener, E., & Suh, E. (1996). Discriminant validity of well-being measures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71 (3), 616–628. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.71.3.616

Maxwell, S. E., & Cole, D. A. (2007). Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychological Methods, 12 (1), 23–44. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.23

Mensinger, J. L., Tylka, T. L., & Calamari, M. E. (2018). Mechanisms underlying weight status and healthcare avoidance in women: A study of weight stigma, body-related shame and guilt, and healthcare stress. Body Image, 25 , 139–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2018.03.001

Modica, C. (2019). Facebook, body esteem, and body surveillance in adult women: The moderating role of self-compassion and appearance-contingent self-worth. Body Image, 29 , 17–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.02.002

Moffitt, R. L., Neumann, D. L., & Williamson, S. P. (2018). Comparing the efficacy of a brief self-esteem and self-compassion intervention for state body dissatisfaction and self-improvement motivation. Body Image, 27 , 67–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2018.08.008

Mosewich, A. D., Kowalski, K. C., Sabiston, C. M., Sedgwick, W. A., & Tracy, J. L. (2011). Self-compassion: A potential resource for young women athletes. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 33 (1), 103–123. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.33.1.103

Neff, K. (2003a). Development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2 (3), 223–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309027

Neff, K. (2003b). Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2 (3), 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309032

Neff, K. D. (2011). Self-compassion, self-esteem, and well-being. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5 (1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00330.x

Neff, K. D., & Germer, C. K. (2013). A pilot study and randomized controlled trial of the mindful self-compassion program. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69 (1), 28–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21923

Neff, K. D., & Vonk, R. (2009). Self-compassion versus global self-esteem: Two different ways of relating to oneself. Journal of Personality, 77 (1), 23–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00537.x

Przezdziecki, A., & Sherman, K. A. (2016). Modifying affective and cognitive responses regarding body image difficulties in breast cancer survivors using a self-compassion-based writing intervention. Mindfulness, 7 (5), 1142–1155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0557-1

Raes, F., Pommier, E., Neff, K. D., & Van Gucht, D. (2011). Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the Self-Compassion Scale. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 18 (3), 250–255. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.702

Raque-Bogdan, T. L., Piontkowski, S., Hui, K., Schaefer Ziemer, K., & Garriott, P. O. (2016). Self-compassion as a mediator between attachment anxiety and body appreciation: An exploratory model. Body Image, 19 , 28–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.08.001

Robinson, K. J., Mayer, S., Allen, A. B., Terry, M., Chilton, A., & Leary, M. R. (2016). Resisting self-compassion: Why are some people opposed to being kind to themselves? Self and Identity, 15 (5), 505–524. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2016.1160952

Rodgers, R. F., Franko, D. L., Donovan, E., Cousineau, T., Yates, K., McGowan, K., Cook, E., & Lowy, A. S. (2017). Body image in emerging adults: The protective role of self-compassion. Body Image, 22 , 148–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2017.07.003

Rodgers, R. F., Donovan, E., Cousineau, T., Yates, K., McGowan, K., Cook, E., Lowy, A. S., & Franko, D. L. (2018). BodiMojo : Efficacy of a mobile-based intervention in improving body image and self-compassion among adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47 (7), 1363–1372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0804-3

Salzberg, S. (1995). Loving-kindness: The revolutionary art of happiness . Shambala Publications.

Sandoz, E. K., Wilson, K. G., Merwin, R. M., & Kellum, K. K. (2013). Assessment of body image flexibility: The Body Image-Acceptance and Action Questionnaire. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 2 (1–2), 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2013.03.002

Schaefer, L. M., & Thompson, J. K. (2014). The development and validation of the Physical Appearance Comparison Scale-Revised (PACS-R). Eating Behaviors, 15 (2), 209–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.01.001

Seekis, V., Bradley, G. L., & Duffy, A. (2017). The effectiveness of self-compassion and self-esteem writing tasks in reducing body image concerns. Body Image, 23 , 206–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2017.09.003

Siegel, J. A., Huellemann, K. L., Hillier, C. C., & Campbell, L. (2020). The protective role of self-compassion for women’s positive body image: An open replication and extension. Body Image, 32 , 136–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.12.003

Slater, A., Varsani, N., & Diedrichs, P. C. (2017). #fitspo or #loveyourself? The impact of fitspiration and self-compassion Instagram images on women’s body image, self-compassion, and mood. Body Image, 22 , 87–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2017.06.004

Stutts, L. A., & Blomquist, K. K. (2018). The moderating role of self-compassion on weight and shape concerns and eating pathology: A longitudinal study. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 51 (8), 879–889. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22880

Swami, V., Barron, D., & Furnham, A. (2018). Exposure to natural environments, and photographs of natural environments, promotes more positive body image. Body Image, 24 , 82–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2017.12.006

Swami, V., Barron, D., Hari, R., Grover, S., Smith, L., & Furnham, A. (2019). The nature of positive body image: Examining associations between nature exposure, self-compassion, functionality appreciation, and body appreciation. Ecopsychology, 11 (4), 243–253. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2019.0019

Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C., Dodos, L., Chatzisarantis, N., & Ntoumanis, N. (2017). A diary study of self-compassion, upward social comparisons, and body image-related outcomes. Health and Well-Being, 9 (2), 242–258. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12089

Thompson, J. K., Heinberg, L. J., Altabe, M., & Tantleff-Dunn, S. (1999). Exacting beauty: Theory, assessment, and treatment of body image disturbance . American Psychological Association.

Toole, A. M., & Craighead, L. W. (2016). Brief self-compassion meditation training for body image distress in young adult women. Body Image, 19 , 104–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.09.001

Trekels, J., Ward, L. M., & Eggermont, S. (2018). I “like” the way you look: How appearance- focused and overall Facebook use contribute to adolescents’ self-sexualization. Computers in Human Behavior, 81 , 198–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.12.020

Turk, F., & Waller, G. (2020). Is self-compassion relevant to the pathology and treatment of eating and body image concerns? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 79 , 101856. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101856

Tylka, T. L. (2006). Development and psychometric evaluation of a measure of intuitive eating. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53 (2), 226–240. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.53.2.226

Tylka, T. L. (2011). Refinement of the tripartite influence model for men: Dual body image pathways to body change behaviors. Body Image, 8 (3), 199–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2011.04.008

Tylka, T. L., & Andorka, M. J. (2012). Support for an expanded tripartite influence model with gay men. Body Image, 9 (1), 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2011.09.006

Tylka, T. L., & Iannantuono, A. C. (2016). Perceiving beauty in all women: Psychometric evaluation of the Broad Conceptualization of Beauty Scale. Body Image, 17 , 67–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.02.005

Tylka, T. L., & Kroon Van Diest, A. M. (2015). Protective factors in the development of eating disorders. In L. Smolak & M. P. Levine (Eds.), The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of eating disorders (pp. 430–444). Wiley.

Tylka, T. L., & Wood-Barcalow, N. L. (2015a). The Body Appreciation Scale-2: Item refinement and psychometric evaluation. Body Image, 12 (1), 53–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.09.006

Tylka, T. L., & Wood-Barcalow, N. L. (2015b). What is and what is not positive body image? Conceptual foundations and construct definition. Body Image, 14 , 118–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2015.04.001

Tylka, T. L., Russell, H. L., & Neal, A. A. (2015). Self-compassion as a moderator of thinness-related pressures’ associations with thin-ideal internalization and disordered eating. Eating Behaviors, 17 , 23–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.12.009

Vartanian, L. R., & Shaprow, J. G. (2008). Effects of weight stigma on exercise motivation and behavior. Journal of Health Psychology, 13 (1), 131–138. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105307084318

Vimalakanthan, K., Kelly, A. C., & Trac, S. (2018). From competition to compassion: A caregiving approach to intervening with appearance comparisons. Body Image, 25 , 148–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2018.03.003

Voelker, D. K., Petrie, T. A., Huang, Q., & Chandran, A. (2019). Bodies in motion: An empirical evaluation of a program to support positive body image in female collegiate athletes. Body Image, 28 , 149–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.01.008

Wasylkiw, L., MacKinnon, A. L., & MacLellan, A. M. (2012). Exploring the link between self-compassion and body image in university women. Body Image, 9 (2), 236–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2012.01.007

Webb, J. B., Fiery, M. F., & Jafari, N. (2016). “You better not leave me shaming!” Conditional indirect effect analyses of anti-fat attitudes, body shame, and fat talk as a function of self-compassion in college women. Body Image, 18 , 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.04.009

Wiseman, M. C., & Moradi, B. (2010). Body image and eating disorder symptoms in sexual minority men: A test and extension of objectification theory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57 (2), 154–166. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018937

Wood-Barcalow, N. L., Tylka, T. L., & Augustus-Horvath, C. L. (2010). But I like my body: Positive body image characteristics and a holistic model for young-adult women. Body Image, 7 (2), 106–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2010.01.001

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, The Ohio State University, Marion, OH, USA

Tracy L. Tylka

Western University, London, ON, Canada

Katarina L. Huellemann

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Tracy L. Tylka .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Telethon Kids Institute, Nedlands, WA, Australia

Amy Finlay-Jones

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA

Karen Bluth

University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA

Kristin Neff

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Tylka, T.L., Huellemann, K.L. (2023). Self-Compassion and Body Image. In: Finlay-Jones, A., Bluth, K., Neff, K. (eds) Handbook of Self-Compassion. Mindfulness in Behavioral Health. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-22348-8_11

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-22348-8_11

Published : 24 March 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-22347-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-22348-8

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Body dissatisfaction, importance of appearance, and body appreciation in men and women over the lifespan.

- 1 Department of Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, Institute of Psychology, Osnabrück University, Osnabrück, Germany

- 2 Department of Research Methodology, Diagnostics & Evaluation, Institute of Psychology, Osnabrück University, Osnabrück, Germany

- 3 Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, Institute of Psychology, University of Münster, Münster, Germany

Body image disturbance is associated with several mental disorders. Previous research on body image has focused mostly on women, largely neglecting body image in men. Moreover, only a small number of studies have conducted gender comparisons of body image over the lifespan and included participants aged 50 years and older. With regard to measurement, body image has often been assessed only in terms of body dissatisfaction, disregarding further aspects such as body appreciation or the importance of appearance. The aim of this cross-sectional study was to explore different aspects of body image in the general German-speaking population and to compare men and women of various ages. Participants completed an online survey comprising questionnaires about body image. Body dissatisfaction, importance of appearance, the number of hours per day participants would invest and the number of years they would sacrifice to achieve their ideal appearance, and body appreciation were assessed and analyzed with respect to gender and age differences. We hypothesized that body dissatisfaction and importance of appearance would be higher in women than in men, that body dissatisfaction would remain stable across age in women, and that importance of appearance would be lower in older women compared to younger women. Body appreciation was predicted to be higher in men than in women. General and generalized linear models were used to examine the impact of age and gender. In line with our hypotheses, body dissatisfaction was higher in women than in men and was unaffected by age in women, and importance of appearance was higher in women than in men. However, only in men did age predict a lower level of the importance of appearance. Compared to men, women stated that they would invest more hours of their lives to achieve their ideal appearance. For both genders, age was a predictor of the number of years participants would sacrifice to achieve their ideal appearance. Contrary to our assumption, body appreciation improved and was higher in women across all ages than in men. The results seem to suggest that men’s and women’s body image are dissimilar and appear to vary across different ages.

Introduction

Many people are concerned about at least one part of their body ( 1 ). A negative cognitive evaluation of one’s body can be an expression of a negative body image ( 2 ). Body image is conceptualized as a multidimensional construct, which encompasses a behavioral component involving body-related behaviors (e.g. checking behaviors), a perceptual component involving the perception of body characteristics (e.g. estimation of one’s body size or weight), and a cognitive-affective component involving cognitions, attitudes, and feelings toward one’s body ( 3 – 6 ).

Negative thoughts and feelings about one’s body are defined as body dissatisfaction ( 7 ), which is considered to be the most important global measure of stress related to the body ( 4 ). Body dissatisfaction has been found to be a predictor for the development of an eating disorder ( 8 ) and occurs in individuals with different mental disorders, such as binge eating disorder or social anxiety disorder (e.g. 6 , 9 ), as well as in healthy persons (e.g. 10 – 12 ). It represents one of the two poles of the satisfaction-dissatisfaction continuum of body image disturbance ( 4 ), which encompasses measures of satisfaction (e.g. being satisfied with particular body areas; e.g. 13 ) and dissatisfaction (e.g. weight or muscle dissatisfaction; e.g. 14 , 15 ).

Another construct which is related to both the cognitive-affective and the behavioral component is the importance of appearance, also termed appearance orientation, which reflects the cognitive-behavioral investment in one’s appearance as an expression of the importance people place on their appearance ( 16 , 17 ). This construct was shown to be distinguishable from the construct of appearance evaluation ( 18 ), which also represents a measure of body satisfaction/dissatisfaction.

Besides negative body evaluation and the importance of appearance, a positive appraisal of one’s body also forms part of the cognitive-affective component. For instance, body appreciation is defined as accepting, respecting, and having a favorable opinion of one’s own body, as well as rejecting unrealistic body ideals portrayed by the media ( 19 ). Body appreciation was shown to predict indices of well-being beyond other measures of body image ( 19 ) and occurred simultaneously with body dissatisfaction, highlighting the independence of the two concepts ( 20 ).

In the past, studies have investigated the impact of gender and age on body features related to the cognitive-affective component. Specifically, research on body dissatisfaction has shown that girls and female adolescents (e.g. 21 – 24 ), and women of all ages (e.g. 12 , 25 , 26 ) report body dissatisfaction. While some studies revealed that the level of body dissatisfaction varied across different age groups ( 27 , 28 ), others found that body dissatisfaction remained quite stable across the adult lifespan in females ( 20 , 25 , 29 , 30 ). Studies examining other aspects of the satisfaction-dissatisfaction continuum, such as weight dissatisfaction ( 15 , 31 ) or satisfaction with particular body parts ( 13 , 32 ), also found body dissatisfaction in women. Frederick and colleagues ( 33 ) estimated that 20% to 40% of women are dissatisfied with their bodies. Nevertheless, body dissatisfaction is also reported in men, suggesting that 10% to 30% of men show body dissatisfaction ( 33 ) or 69% of male adolescents to be dissatisfied with their bodies in terms of their weight ( 34 ). Frederick and colleagues ( 14 ) even reported that 90% of male US students in their sample described themselves as being dissatisfied with respect to muscularity. In terms of body evaluation, striving for increased muscularity, referred to as drive for muscularity ( 35 ), has emerged as a central issue for boys and men (e.g. 35 – 38 ). It was shown to be distinct from body dissatisfaction ( 39 ). However, although previous studies reported that body dissatisfaction does not differ across age in women, it remains unclear whether the level of body dissatisfaction changes across age in men.

While body dissatisfaction seems to remain stable across age in women, studies suggest that the importance of appearance appears to decrease with age ( 40 ). In line with Pliner and colleagues, Tiggemann and Lynch ( 41 ) found in a group of females aged 20 to 84 years that the importance of appearance was lower in older than in younger women. For men, only one study has examined the importance of appearance, and found that it varied between age groups and reached a peak at age 75 years and older ( 42 ). To our knowledge, no other study has examined the importance of appearance in men over the lifetime. Thus, it remains relatively unclear whether the importance of appearance remains stable or changes over the lifetime in men.

With respect to body appreciation, Tiggemann and McCourt ( 20 ) demonstrated higher body appreciation in older than in younger women. Furthermore, high body appreciation was found to be protective against the negative effects of media exposure to thin models in women ( 43 ). Other studies reported that body appreciation in men and women was associated with a low level of consumption of Western and appearance-focused media ( 44 ) and correlated negatively with internalization of sociocultural ideals ( 45 ). However, studies focusing on age differences regarding body appreciation in males are lacking.

Previous studies on body image have mostly considered age-related changes in either men or women, or in particular age groups (e.g. college students, adolescents). Only a limited number of studies have compared men and women with respect to the aforementioned aspects of body image. These studies generally found greater body dissatisfaction in females than in males (e.g. 29 , 30 , 46 – 49 ). Men (vs. women) seem to place less importance on their appearance ( 42 , 50 , 51 ) and report slightly higher levels of body appreciation (e.g. 45 , 52 – 54 ). Tylka and Wood-Barcalow ( 55 ) also reported higher body appreciation in college men (vs. college women), but were unable to replicate this effect in a community sample. In contrast to this latter result, Swami and colleagues ( 53 ) reported higher body appreciation in men than in women in a sample from the general Austrian population. However, these studies comparing men and women did not analyze their data with respect to the impact of age.

Only a small number of studies have investigated the effect of age and gender on body dissatisfaction, importance of appearance and body appreciation. In a two-year longitudinal study, Mellor and colleagues ( 56 ) found that body dissatisfaction was higher in females than in males and higher in younger than in older participants. In another longitudinal study, Keel and colleagues ( 15 ) examined men and women over a period of 20 years. As men aged, the authors observed increasing weight and increasing weight dissatisfaction, while weight dissatisfaction decreased in women despite analogous increases in weight. The authors concluded that women appear to be more accepting of their weight as they age ( 15 ). Unfortunately, the mean age at the 20-year follow-up was only 40 years, meaning that conclusions could not be drawn about the whole adult lifespan. Similarly, in a large sample of men and women aged 18 to 49 years, Ålgars et al. ( 46 ) found that overall body dissatisfaction was higher in women than in men, but that only in women was age associated with decreasing body dissatisfaction, while in men, body dissatisfaction changed across the different age groups ( 46 ). However, these results have to be interpreted with caution, as the sample consisted of twins and was thus not representative of the general population.

Other studies found higher levels of body dissatisfaction ( 28 ) and lower levels of satisfaction with certain body areas ( 29 ) in women than in men. However, the latter study did not find any gender- or age-related effect on overall body dissatisfaction ( 29 ). Concerning the importance of appearance, Öberg and Tornstam ( 42 ) found that women placed more importance on their appearance than did men, and that this factor remained stable across different age groups in women but varied in men. These results are contrary to the findings of Tiggemann and Lynch ( 41 ) and Pliner et al. ( 40 ), who found that the importance of appearance decreased with age in women. However, this discrepancy may be due to the assessment method in the study by Öberg and Tornstam, as they used a single item to evaluate the importance of appearance. Hence, the development of importance of appearance in men and women across the lifespan remains unclear.

Although, as mentioned above, some studies have found that women place less importance on their appearance as they age ( 40 , 41 ), this aspect has not been examined in a large population sample comprising different age groups in relation to the impact of gender and age. Furthermore, studies comparing body appreciation between men and women across different age groups are lacking. To our knowledge, no previous study has examined body dissatisfaction, importance of appearance and body appreciation in the general population including men and women aged 16 to 50 years and older. Therefore, the present study aims to fill this research gap by analyzing these negative and positive aspects of body image in a general population sample considering gender and age.

First, based on the previous findings outlined above, we predicted that body dissatisfaction would be higher in women than in men (Hypothesis 1) and would remain stable across age in women (Hypothesis 2). As no previous study has investigated body dissatisfaction across the whole lifespan in men, we aimed to examine a potential influence of age on body dissatisfaction in men.

Second, we hypothesized that women would place more importance on their appearance than men (Hypothesis 3), but that in line with the aforementioned studies, across age, older women would report lower levels of importance than younger women (Hypothesis 4). Given the lack of corresponding studies in men, we intended to investigate the importance of appearance and its relation to age in men in an exploratory analysis. Furthermore, appearance orientation assesses the importance of appearance in terms of the extent of investment in one’s appearance (e.g. grooming behaviors) and in terms of the attention one pays to one’s appearance. However, it does not quantify how many hours or years people would be willing to invest in their appearance to look the way they want to. Therefore, as a measure of the importance of appearance, we additionally assessed the number of hours men and women would be willing to invest per day to achieve their ideal appearance, and the number of years of their life they would sacrifice to achieve their ideal appearance.

Third, we predicted that body appreciation would be higher in men than in women (Hypothesis 5). As the aforementioned studies examined gender differences without analyzing the impact of age, we aimed to investigate potential changes in body appreciation across age in an exploratory manner.

Fourth, to take into account the well-documented increase in BMI over the lifetime (e.g. 46 , 57 , 58 ) and its potential association with the outcome variables, we examined these relations as a control analysis by calculating correlations between the subjective evaluations of body image and BMI.

Materials and Methods

Participants.

Inclusion criteria were age 16 years and older, sufficient German-language skills, and internet access. Data were collected from N = 1,338 persons. From the original data set, n = 4 participants had to be excluded due to ambiguous details about their age or invalid responses to questions. Moreover, n = 7 persons were excluded as they did not fit into the binary gender categories male or female. The final study sample comprised n = 942 women and n = 385 men, aged 16 to 88 years (total sample: n = 1,327).

Demographic Data

All participants completed a questionnaire assessing demographic data such as gender, age, height and weight, educational level, relationship status, sexual orientation, and number of children. The item on sexual orientation was optional. Self-reported weight and height were used to calculate the body mass index (BMI, kg/m 2 ).

Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire–Appearance Scales

The Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire–Appearance Scales [MBSRQ-AS; ( 16 ); German-language version: ( 17 )] is a self-report questionnaire consisting of 34 items and five subscales to assess different appearance-related aspects of body image. The MBSRQ-AS has been validated for participants aged 15 years and older and for both men and women ( 16 ). For the purpose of this study, the Appearance Evaluation Scale (seven items) and Body Areas Satisfaction Scale (nine items) were used to assess body dissatisfaction, and the Appearance Orientation Scale (12 items) was applied to examine the importance people place on their appearance. According to Cash ( 16 ), the Appearance Evaluation Scale measures overall satisfaction/dissatisfaction with one’s appearance and physical attractiveness, with high scores indicating body satisfaction and low scores indicating body dissatisfaction. Furthermore, the Body Areas Satisfaction Scale (nine items) assesses satisfaction/dissatisfaction with particular body areas; high and low scores are analogous to the Appearance Evaluation Scale. The Appearance Orientation Scale (12 items) evaluates the investment in one’s appearance, with low scores indicating that people do not place importance on or invest much effort into being “good-looking”. All items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale with different response labeling ( Appearance Evaluation Scale and Appearance Orientation Scale : 1 = definitely disagree to 5 = definitely agree; Body Areas Satisfaction Scale : 1 = very dissatisfied to 5 = very satisfied). While the English-language version has been validated in both men and women ( 16 ), the German-language version has only been validated for females ( 17 ). In the German validation, all subscales showed good internal consistency (α = .78–.90; 17 ). In the current sample, high internal consistencies were found ( Appearance Evaluation Scale : α = .88; Appearance Orientation Scale : α = .85; Body Areas Satisfaction Scale : α = .81), both for men ( Appearance Evaluation Scale : α = .87; Appearance Orientation Scale : α = .85; Body Areas Satisfaction Scale : α = .80) and women ( Appearance Evaluation Scale : α = .89; Appearance Orientation Scale : α = .86; Body Areas Satisfaction Scale : α = .81).

Body Appreciation Scale-2

The Body Appreciation Scale-2 (BAS-2; 55 ; German-language version: Steinfeld, unpublished manuscript) assesses body appreciation in a gender-neutral manner using 10 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never to 5 = always). High internal consistency (α = .96) was found for the BAS-2 in an English-speaking sample of men and women ( 55 ). In our sample, internal consistency was high (α = .94), both in males (α = .92) and females (α = .94).

Investment in One’s Appearance

To investigate the amount of time which men and women would be willing to invest in and sacrifice for their own appearance, participants were asked the following two questions: “How many years of your life would you be willing to sacrifice if you could look the way you want?”, “How many hours a day would you invest in your appearance if you could look the way you want?”

Single-Item Self-Esteem Scale

The Single-Item Self-Esteem Scale (SISE; 59 ) measures self-esteem using the item “I have high self-esteem,” which is rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not very true of me to 5 = very true of me). It has shown high correlations with the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale and a high test-retest reliability after four years ( r tt = .75) ( 59 ).

Depression Anxiety Stress Scales–Depression Subscale

The Depression Anxiety Stress Scales–Depression Subscale (DASS-D) ( 60 ; German-language version: 61 ) consists of seven items assessing depressive mood over the past week on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = never to 3 = always). For the German version of the DASS-D, high internal consistency has been found (α = .88) ( 61 ). In the present study, internal consistency ranged from α = .89 for men to α = .91 for women (total sample: α = .90).

Study Procedure

Participants were recruited via social media, mailing lists, press releases, advertisements, and flyers and were asked to take part in a short online survey comprising different questionnaires about body image. To access the study website, they could either scan a barcode or use a web link. The online survey was set up using the software Unipark (Version EFS Winter 2018; 62 ). Participants were informed about the purpose of the study and were asked to provide their informed consent by clicking a button next to a declaration asserting that they agree to the processing of their personal data according to the given information. The survey began once participants had provided consent and took approximately 10 min to complete. Participants were offered no financial compensation for study participation. The research project was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of Osnabrück University.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was performed using the software SPSS Statistics (version 25; IBM 63 ) for descriptive statistics, correlation analysis, and general linear models and the software R (version 3.5.3; R 64 ) with the DHARMa package (version 0.2.4; 65 ), the glmmTMB package (version 0.2.3; 66 ), and the MASS package (version 7.3–51.3; 67 ) for generalized linear models. As we intended to explore homogenous hypotheses in terms of body dissatisfaction, the power was set at a significance level of p = .10 for the variable age.

For group comparisons on demographic and descriptive variables ( Table 1 ), we calculated Mann-Whitney U Tests, as our data were not normally distributed (except BMI). Since inferential statistics for simple comparisons are massively overpowered in such large samples, we additionally report effect sizes. For better interpretability, U -values were converted into correlation coefficients r ( 68 , 69 ). For correlations between BMI and the body image variables ( Table 3 ), Spearman’s rank correlations were calculated due to non-normally distributed data.

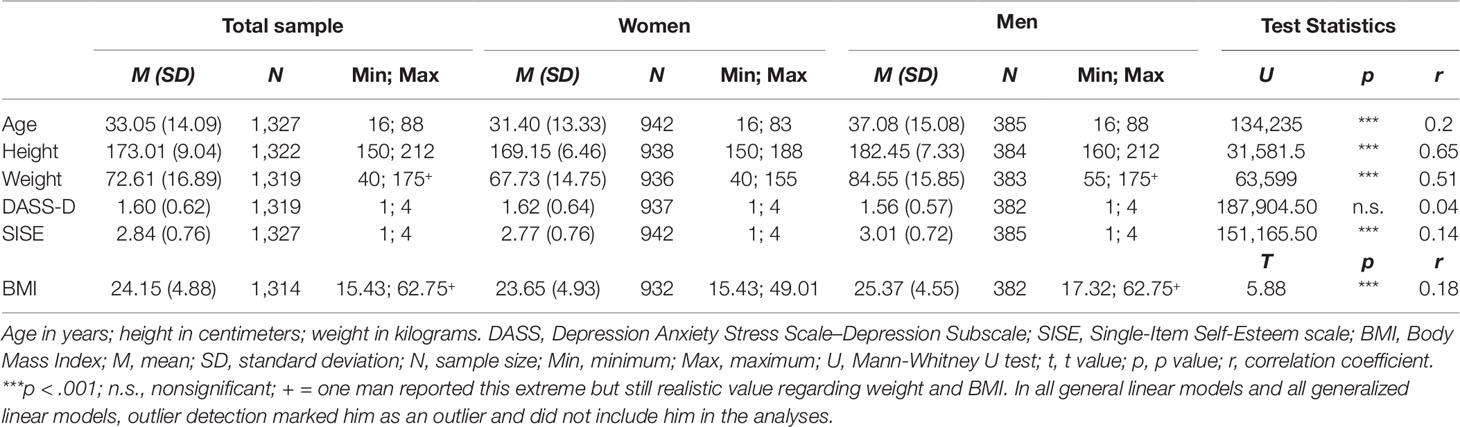

Table 1 Descriptive statistics and group comparisons regarding age, height, weight, BMI, depression, and self-esteem.

For linear and generalized linear models, gender was dummy-coded, with men as the reference category. Age was centered to simplify the interpretation of the model coefficients. Due to missing data on single items within the questionnaires, the sample sizes for the initial model estimations varied, since participants were only included in the respective data analysis if they answered all items of a scale. To examine the individual impact of gender and age for each dependent variable, we started with the general linear model and inspected the residual distributions, tested statistically and by visual inspection for normality, and tested for homogeneity of variance as well as for skewness, kurtosis, and outliers (Mahalanobis and Cook’s distance, Leverage). While Cook’s distance should be smaller than 1 ( 70 ) and Leverage for large samples <3 k / N ( 71 ), a value was identified as an outlier if the Mahalanobis distances were above the critical χ 2 value exceeding the probability of 0.01 ( 72 ) and if studentized deleted residuals were larger than 3 standard deviations. The highest number of outliers was detected for the Body Areas Satisfaction Scale, with 3.36%. Comparisons of the models with and without outliers revealed no substantial differences; hence, we report the models without potential outliers, as power issues were not expected for such a large sample size and precision of estimates was prioritized. Final sample sizes are reported for each model ( Tables 4 and 5 ).

For the Body Areas Satisfaction Scale, the assumption of homogeneity was violated. Therefore, a general linear model was calculated, using the HC3 method for robust estimation of the standard errors. Furthermore, due to skewness and non-normal distribution of the data, responses to the Body Appreciation Scale-2 were inverted and a generalized linear model with a gamma distribution and identity link function was used. The analyses of hours people would invest in their appearance and years people would sacrifice from their lives indicated severe violations of the assumptions of the general linear model, since their distributions were similar to zero-bounded count data. Therefore, the numbers of hours and years were rounded to integer values to enable us to calculate several Poisson and negative binomial regression models, which are suitable for count data. The fit of each model was assessed by tests for overdispersion and zero inflation, as well as by tests of residual fit using the DHARMa package. As a final model for the analyses of the years people would sacrifice from their lives, we used a negative binomial regression with a log-link and linearly increasing variance ( 73 ) and adjustment for zero inflation for the intercept using the glmmTMB package. For the analyses of the hours people would spend on their appearance, we used a negative binomial regression with the log-link function using the MASS package.

Sample Characteristics

Descriptive statistics and group differences are shown in Table 1 . Men and women differed significantly in terms of age, height, weight, BMI, and self-esteem. Compared to women, men were slightly older, taller, and heavier and had a higher BMI. This is in line with data from the German Federal Statistical Office ( 57 ), which reported a mean weight of 68.7 kg, a mean height of 166 cm and a mean BMI of 25.1 in German women, and a mean weight of 85.0 kg, a mean height of 179 cm and a mean BMI of 26.1 in German men. As indicators of psychopathology, men and women did not differ regarding depressive mood over the past week ( p = .152), whereas self-esteem was higher in men than in women.

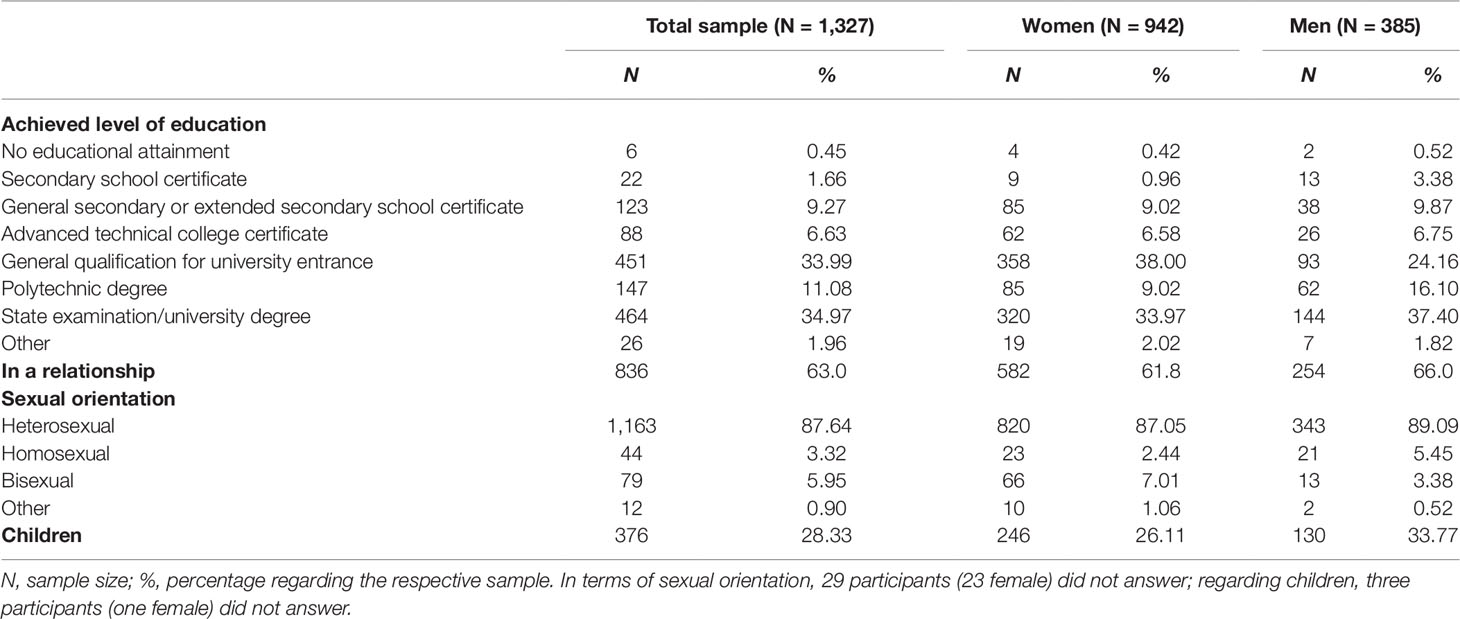

Information about educational level, relationship status, number of children, and sexual orientation is reported in Table 2 . Of the total sample, n = 29 participants (of whom n = 23 were female) refused to answer the question regarding sexual orientation, and n = 3 participants (of whom n = 1 was female) did not state whether they had children. A recent study on the proportion of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) persons in Europe reported that 7.40% of the German population identify themselves as LGBT ( 74 ). In our sample, 10.17% reported a sexual orientation other than heterosexuality, which is slightly higher than the reported value for the German population, but can be still considered as representative.

Table 2 Numbers and percentages regarding educational level, relationship status, and sexual orientation for total sample, women, and men.

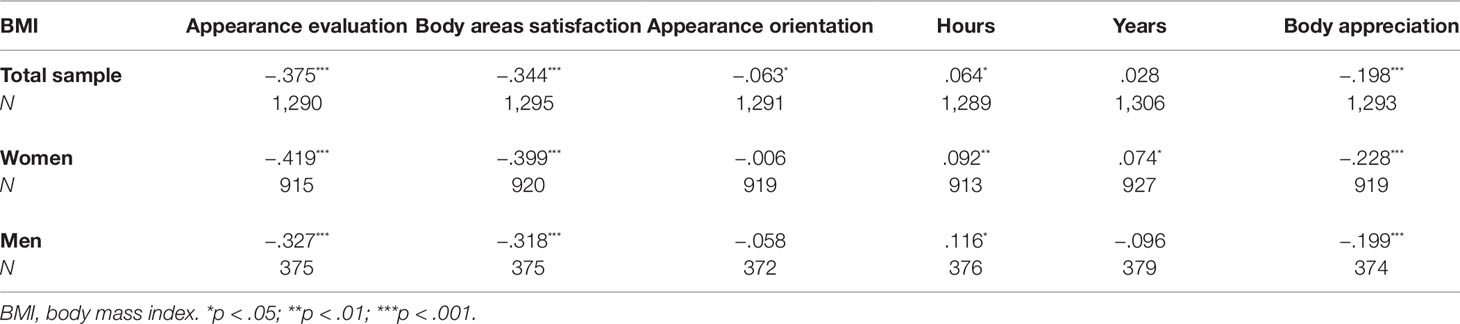

The Spearman’s rank correlations of BMI with body dissatisfaction, importance of appearance, the number of hours per day participants would invest and years they would sacrifice to achieve their ideal appearance, and body appreciation are displayed in Table 3 .

Table 3 Spearman’s correlations between BMI and the scores on the scales Appearance Evaluation, Body Areas Satisfaction, Appearance Orientation, the number of hours per day participants would invest to achieve their ideal appearance, and the number of years participants would sacrifice to achieve their ideal appearance and Body Appreciation for total sample, women, and men.

General and Generalized Linear Models

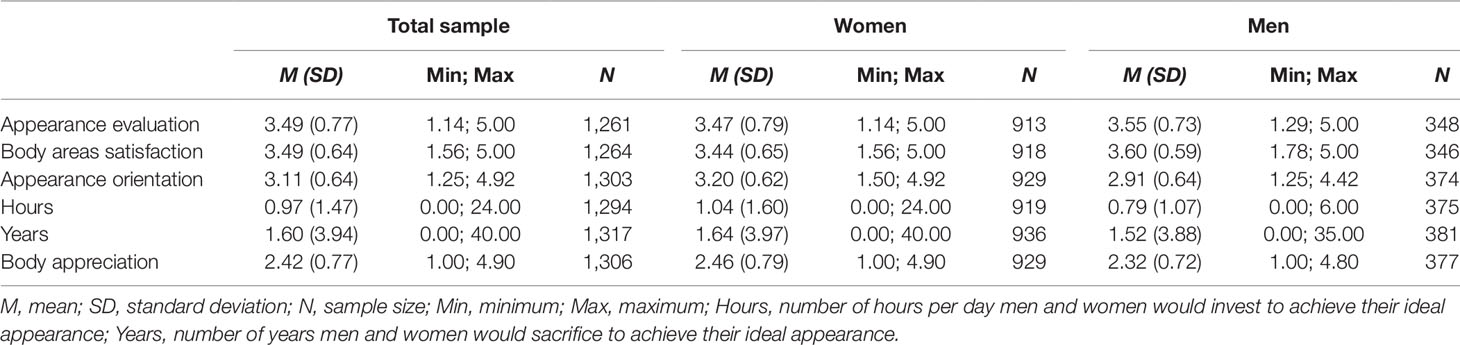

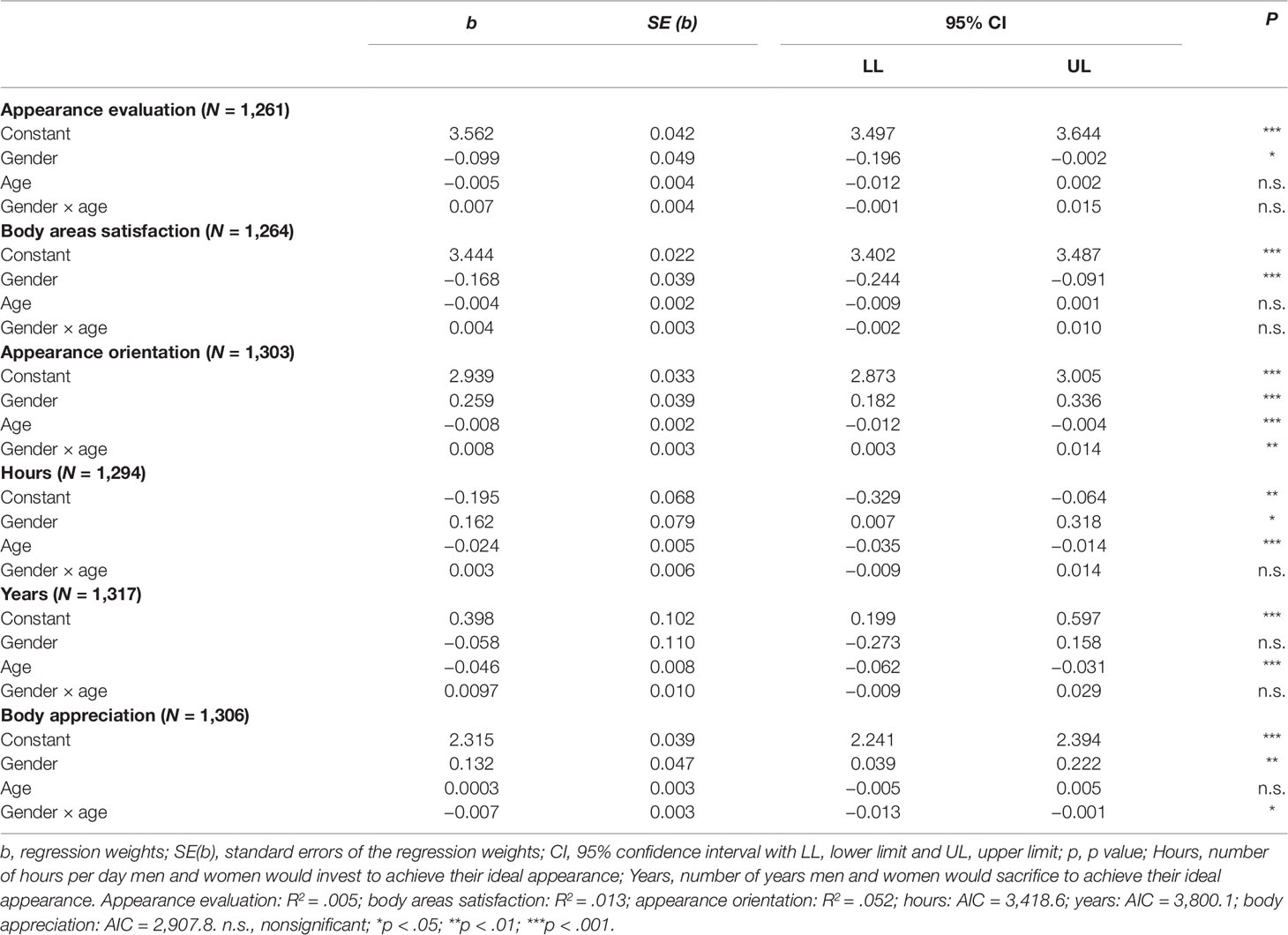

Table 4 presents the descriptive statistics for appearance evaluation, body areas satisfaction, appearance orientation, hours of investment, and years of sacrifice, as well as body appreciation, separated for total sample, men, and women. The results of the general and the generalized linear models are displayed in Table 5 . Regarding body dissatisfaction, gender emerged as the only significant predictor of appearance evaluation ( t = −2.012, p = .044) and body areas satisfaction ( t = 4.282, p < .001), indicating lower appearance evaluation and lower body areas satisfaction in women than in men. Age (appearance evaluation: t = −1.489, p = .137; body areas satisfaction: t = −1.605, p = .109) and the interaction of age × gender (appearance evaluation: t = 1.630, p = .103; body areas satisfaction: t = 1.257, p = .209) did not reach statistical significance. In terms of the importance of appearance, gender ( t = 6.597, p < .001), age ( t = −3.636, p < .001), and the interaction of gender × age ( t = 3.194, p < .001) significantly predicted appearance orientation, revealing that women placed more importance on their appearance than did men, whereas age only influenced the importance of appearance in men. The number of hours which participants would spend on their appearance if they could achieve their ideal appearance was predicted by gender ( z = 2.037, p = .042) and age ( z = −4.654, p < .001), indicating that women would invest more hours than men, but that with higher age, both genders would invest fewer hours in their appearance. The interaction of gender × age ( z = 0.428, p = .67) was not significant. Age was the only predictor of the number of years participants would be willing to sacrifice to achieve their ideal appearance ( z = −5.828, p < .001), revealing that with higher age, men and women would sacrifice fewer years for their ideal appearance. Neither gender ( z = −0.526, p = .60) nor the interaction of gender × age ( z = 1.015, p = .310) had a significant impact on the number of years. Furthermore, gender ( t = 2.828, p = . 005) and the interaction of gender × age ( t = −2.186, p = . 029) were significant predictors of body appreciation, insofar as with higher age, women reported higher body appreciation than men, while body appreciation in men remained stable with higher age. Age ( t = 0.127, p = . 899) did not reach statistical significance.

Table 4 Descriptive statistics regarding the scores on the scales Appearance Evaluation, Body Areas Satisfaction, Appearance Orientation, hours of investment, and years of sacrifice, as well as Body Appreciation for total sample, women and men used in the final models.

Table 5 General linear models for the prediction of Appearance Evaluation, Body Areas Satisfaction and Appearance Orientation as well as generalized linear models for the prediction of Body Appreciation, the number of hours per day participants would invest to achieve their ideal appearance, and the number of years participants would sacrifice to achieve their ideal appearance, with gender and age as predictors.

The aim of the present study was to investigate potential gender differences and the impact of age on body dissatisfaction, importance of appearance, the number of hours per day participants would invest and the number of years they would sacrifice to achieve their ideal appearance, and body appreciation in the general population.

As predicted in our first hypothesis, we found an effect of gender on the Appearance Evaluation Scale and the Body Areas Satisfaction Scale, suggesting that women were significantly more dissatisfied with their bodies than men. This is in accordance with the results of several studies (e.g. 28 , 30 , 46 , 56 ), which likewise reported higher levels of body dissatisfaction in women than in men. In line with our results, Fallon and colleagues ( 29 ) found that women (vs. men) reported higher levels of body dissatisfaction on the Body Areas Satisfaction Scale, but contrary to our study, the authors did not find an effect of gender on the Appearance Evaluation Scale. Keel et al. ( 15 ) even found higher weight dissatisfaction in men than in women, which is also in contrast to previous findings. Therefore, it might be possible that women may be more satisfied with their weight while still reporting more body dissatisfaction.

Additionally, we found that body dissatisfaction on the Appearance Evaluation Scale and on the Body Areas Satisfaction Scale was not influenced by age or by the interaction of gender and age, indicating that body dissatisfaction remains stable across all ages for both genders. For women, this finding confirms our second hypothesis, which assumed that body dissatisfaction would not be influenced by age, and also supports previous findings (e.g. 20 , 25 , 29 , 30 ). One study by Öberg and Tornstam ( 42 ) found that body satisfaction was higher in older than in younger women, which is also in contrast to our findings, as we found no influence of age on body dissatisfaction. For men, our results indicate that body dissatisfaction remains stable across different ages. This is in contrast to Ålgars and colleagues ( 46 ), who found that body dissatisfaction varied across different age groups in men. However, the latter finding might be attributable to artificial grouping strategies, as the authors investigated the impact of the continuous variable age as a categorical variable through the use of age groups. Moreover, Ålgars and colleagues ( 46 ) only assessed participants between the age of 18 and 49 years. The present study included men and women aged from 16 to 88 years, thus covering a broader proportion of the lifespan in Germany; according to the German Federal Statistical Office ( 75 ), the average life expectancy lies at 78.4 years for men and 83.2 years for women. To sum up, body dissatisfaction seems to remain relatively stable across different ages, both for men and for women.

In line with our third hypothesis that women would place more importance on their appearance than men, we found a significant effect of gender on the Appearance Orientation Scale, indicating that women indeed place more importance on their appearance compared to men. This finding corroborates previous studies ( 42 , 50 , 51 ). Moreover, age was a significant predictor of appearance orientation, as was the interaction of gender and age. Although age and the interaction of gender and age reached statistical significance, only in men did higher age bring about a lower importance of appearance. For women, the regression weights of age and the interaction of gender and age cancelled each other out. Therefore, gender was the only factor to impact appearance orientation in women, and the importance of appearance was not affected by age in women. This is in contrast to our fourth hypothesis that older women would report lower levels of importance of appearance than younger women. It also conflicts with previous findings ( 40 , 41 ), as we found that appearance orientation remained stable across all ages in women. In line with our finding, Öberg and Tornstam ( 42 ) also reported that the importance of appearance remained stable in women of different ages. They further found a small variation of the importance of appearance across different age groups in men, with the level of importance being more pronounced from the age of 45 years and older ( 42 ). However, we observed that older men seem to place less importance on their appearance than do younger men.

As the construct of importance of appearance does not reflect the extent to which people are willing to invest time in order to reach their ideal appearance, we additionally assessed the amount of hours per day participants would invest, and the number of years of their lives they would sacrifice, in order to achieve their ideal appearance. We found an effect of gender and age on the number of hours spent on appearance, but only an effect of age on the number of years which participants would sacrifice for their appearance. Women were more likely to spend more hours per day on their ideal appearance than men. However, older men and women would invest fewer hours than their younger counterparts. Concerning the number of years people would be willing to sacrifice to achieve their ideal appearance, we found no effect of gender, but found age to be a significant predictor, meaning that older men and women would sacrifice fewer years from their lives for the sake of their ideal appearance. This indicates that in terms of their behavioral investment regarding the importance of appearance, men and women may be more similar than hitherto assumed. Apparently, women might find it easier to relinquish a small number of hours per day to be invested in their appearance compared to men, but regarding lifetime investment, both genders might be unwilling to sacrifice years of their lives for the sake of their appearance.

Furthermore, we examined the impact of gender and age on body appreciation, and found gender and the interaction of gender and age to be significant predictors. The significant effect of gender suggested that women showed less body appreciation than did men. This is in line with our fifth hypothesis that women would show lower levels of body appreciation than men, and is also in accordance with other studies ( 45 , 53 , 76 ). However, the significant interaction of gender and age indicates that with higher age, women report higher levels of body appreciation compared to men. This is in contrast to the aforementioned studies (e.g. 45 , 53 , 76 ), but may provide an explanation for the lack of a gender effect in an English-speaking community sample in the study by Tylka and Wood-Barcalow ( 55 ). Interestingly, compared to our study, Tylka and Wood-Barcalow ( 55 ) reported slightly higher values (from 3.22 to 3.97) for their samples for both genders. Furthermore, the significant interaction in our study suggested that body appreciation also improves in women across age, and older (vs. younger) women report higher levels of body appreciation. This is in line with Tiggemann and McCourt ( 20 ), who found greater body appreciation in older than in younger women. Regarding men, as pointed out above, no previous study has investigated the impact of age on body appreciation. In our study, the level of body appreciation remained quite stable across different ages in men, and was lower compared to that of women. An explanation might be that men are possibly more affected by restrictions of their body’s functionality due to aging processes ( 27 ), whereas women may cherish their body and the remaining functionality.

With respect to the associations between BMI and the aspects of body image, we found significant negative correlations between BMI and the Appearance Evaluation Scale and Body Areas Satisfaction Scale for men and women, insofar as with increasing BMI, values on both scales decreased (= higher body dissatisfaction). This is in line with previous research, which found that BMI was positively associated with body dissatisfaction in both genders (e.g. 77 – 81 ). Body appreciation was found to be negatively correlated with BMI for both genders, which is partially in line with previous research: One study found this association for women but not for men ( 53 ), while other studies yielded mixed findings, reporting either a negative association between BMI and body appreciation (e.g. 82 , 83 ) or no significant results (e.g. 44 ). Concerning the importance of appearance, we found no significant association with BMI for either gender. In line with our results, some previous studies found no association between the importance of appearance and BMI in both men and women ( 13 , 84 ), while others reported a positive correlation for women but no significant association for men ( 85 ). The latter may be explained by the differentiation between the importance of appearance and the investment of time in appearance, as we found that BMI was positively associated with the number of invested hours for both genders, but was only associated with the number of years participants would sacrifice to achieve their ideal appearance in women. These findings emphasize the distinction between the evaluative perspective of the importance of appearance (How essential are my looks to me)? and the behavioral perspective of the extent of investment in appearance (How many hours/years am I willing to invest in my appearance)?. For instance, a person may place importance on his or her appearance, but as appearance is less important than years of his or her life, he or she is unwilling to invest much effort in appearance. As shown in our study, women reported quite stable, higher levels of importance across age than did men. Consequently, it might be assumed that they have to invest more time in order to achieve their ideal appearance. Nevertheless, as older men and women would invest fewer hours and sacrifice fewer years, the extent of investment or sacrifice is evidently not expressed by the importance of appearance. These results underline the need to differentiate between the importance of appearance and the investment of time in one’s appearance.

Although in the present study, women reported a higher degree of body dissatisfaction than did men, men’s and women’s responses on average lay slightly above the value of 3 on the 5-point Likert scale ( Table 4 ). This indicates, on average, neither agreement nor disagreement on the two scales (3 = I neither agree nor disagree) and possibly reveals a more neutral to slightly positive evaluation of one’s body. These results are in line with those of Cash ( 16 ) and Fallon et al. ( 29 ), who reported similar values on both scales for men and women. Therefore, on average, men and women may be neither particularly dissatisfied nor particularly satisfied with their bodies.

In consideration of all of the aforementioned research, one has to raise the more general question of whether the absence of body dissatisfaction is synonymous with the presence of body satisfaction in terms of a continuum model as proposed by Thompson et al. ( 4 ). Another possibility lies in an alternative model, in which body satisfaction and body dissatisfaction coexist alongside one another. For instance, it may be possible for a person to report high levels of overall body dissatisfaction, while simultaneously reporting high levels of body satisfaction with certain areas (e.g. “In general, I am dissatisfied with my body, but I like my legs, my cheeks and my hair.”). This could result in neither agreement nor disagreement on a continuum scale. Further research is needed to investigate a possible coexistence of both concepts.

Some limitations have to be mentioned when interpreting the results of the present study. Although several coefficients turned out to be significant, they contribute only a minimum of change to the dependent variables. In addition, according to the conventions of Cohen ( 86 ), we found very small values for the R 2 s, as the R 2 s in the present study explained only 0.5% (appearance evaluation) up to 5.2% (appearance orientation) of the total variance. Due to our total sample size of N = 1,327, the significance of the coefficients therefore might be attributed to the study’s power. Moreover, as was the case for most of the previous studies (except for 15 and 56 ), we did not investigate age effects in a longitudinal design. Therefore, it is not possible to disentangle the effects of age and birth cohorts. The effects found in this study may be related to different birth cohorts, the way in which people were brought up and socialized, or different ideals of beauty and fashion. Longitudinal studies including different age cohorts of men and women are therefore required.

Another limitation may lie in the assessment method. As younger people use the internet more frequently than older people ( 87 ), it cannot be excluded that this could have led to a stronger selection bias in older participants. Further, the online assessment may not be representative for the general population ( 88 ). Thus, there was no control regarding the implementation conditions of participation (e.g. whether there were distractions while participating) or regarding who was participating ( 88 ). False answers on variables such as weight, height, and age seem to be easier to notice in the laboratory. However, false statements concerning the variables of body image may be just as difficult to detect in the laboratory or in paper-and-pencil examinations as in online assessments. Our calculation of correlations between BMI and the outcome variables may be seen as a control analysis, as the participants’ answers on BMI were associated with our dependent variables, in line with aforementioned research.

Furthermore, our sample included more women than men. This may reflect the fact that women are more likely to participate in studies than men (e.g. 89 , 90 ). Although general and generalized linear models are able to control for different sample sizes, men and women differed significantly regarding age, height, weight, and self-esteem. While the differences in weight and height could be explained by natural gender differences, men were slightly older than women. As a further limitation, the assessment was restricted to certain body-related aspects and omitted other concepts such as the drive for muscularity ( 35 ) or drive for thinness ( 91 ). We only included appearance-related aspects of body image and body appreciation in order to shorten the length of our study and to decrease the burden of our survey on respondents. Therefore, we concentrated on more general aspects related to the cognitive-affective component of body image. Future studies need to investigate the impact of gender and age on other components of body image, such as perceptual estimation of body size (e.g. 92 ) or checking behaviors (e.g. 93 ). Although some studies have already investigated body image regarding genders other than the distinct categories of male and female (e.g. 94 , 95 ), we did not analyze these persons in the present study due to the insufficient sample size ( N = 7). Moreover, we did not investigate the relation between sexual orientation and body image, although previous studies have found indications of an influence of sexual orientation on body image ( 96 – 99 ). Therefore, future research should investigate the impact of age on body image for different sexual orientations.

In conclusion, the present study is one of the first to examine body dissatisfaction, importance of appearance, the number of hours participants would be willing to invest per day to achieve their ideal appearance and the number of years they would sacrifice to achieve their ideal appearance, and body appreciation in relation to gender and age. Body appreciation was higher in older than in younger women and women reported higher levels of body appreciation compared to men. While the importance of appearance was lower in older than in younger men and remained stable in women, neither gender was willing to relinquish a large amount of time for the sake of their appearance. Although we found higher body dissatisfaction for women than for men, both genders seem to be neither satisfied nor dissatisfied with their bodies on average. Eating disorder prevention programs, or therapeutic approaches for several mental disorders, could benefit from a more functional perspective on the absence of body satisfaction, as this does not necessarily equate with the presence of body dissatisfaction.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics committee of Osnabrück University. Written informed consent from the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

HQ, SV, AH, and UB planned and conducted the study. RD and HQ analyzed the data. HQ wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the compilation of the manuscript and read and approved the submitted version.

We acknowledge support by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) and the Open Access Publishing Fund of Osnabrück University for the publication of the article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. Buhlmann U, Glaesmer H, Mewes R, Fama JM, Wilhelm S, Brähler E, et al. Updates on the prevalence of body dysmorphic disorder: a population-based survey. Psychiatry Res (2010) 178(1):171–5. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.05.002

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Hartmann AS. Der Body Image Disturbance Questionnaire. Diagn (2019) 65:142–52. doi: 10.1026/0012-1924/a000220

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

3. Cash TF. Body image: past, present, and future. Body Image (2004) 1:1. doi: 10.1016/S1740-1445(03)00011-1

4. Thompson JK, Heinberg LJ, Altabe M, Tantleff-Dunn S. Exacting beauty: theory, assessment, and treatment of body image disturbance . Washington, DC: American Psychological Association (1999).

Google Scholar

5. Tuschen-Caffier B. Körperbildstörungen. In Herpertz, de Zwaan & Zipfel (Hrgs.). In: Handbuch Essstörungen und Adipositas . Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer (2015). p. 141–7.

6. Vocks S, Bauer A, Legenbauer T. Körperbildtherapie bei Anorexia und Bulimia Nervosa . Göttingen: Hogrefe (2018).

7. Grogan S. Body Image: understanding body dissatisfaction in men, women and children . 3rd ed. New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group (2016). doi: 10.4324/9781315681528

8. Rohde P, Stice E, Marti CN. Development and predictive effects of eating disorder risk factors during adolescence: implications for prevention efforts. Int J Eating Disord (2015) 48(2):187–98. doi: 10.1002/eat.22270

9. Dunkley DM, Masheb RM, Grilo CM. Childhood maltreatment, depressive symptoms, and body dissatisfaction in patients with binge eating disorder: The mediating role of self-criticism. Int J Eating Disord (2010) 43(3):274–81. doi: 10.1002/eat.20796

10. Cash TF, Morrow JA, Hrabosky JI, Perry AA. How has body image changed? a cross-sectional investigation of college women and men from 1983 to 2001. J Consulting Clin Psychol (2004) 72(6):1081–9. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1081

11. Garner DM. The 1997 body image survey results. Psychol Today (1997) 30:30–84.

12. Mond J, Mitchison D, Latner J, Hay P, Owen C, Rodgers B. Quality of life impairment associated with body dissatisfaction in a general population sample of women. BMC Public Health (2013) 13(1):920. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-920

13. Tiggemann M, Lacey C. Shopping for clothes: body satisfaction, appearance investment, and functions of clothing among female shoppers. Body Image (2009) 6(4):285–91. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2009.07.002

14. Frederick DA, Buchanan DM, Sadeghi-Azar L, Peplau LA, Haselton MG, Berezovskaya A, et al. Desiring the muscular ideal: men’s body satisfaction in the United States, Ukraine, and Ghana. Psychol Men Masc (2007) 8:103–17. doi: 10.1037/1524-9220.8.2.103

15. Keel PK, Baxter MG, Heatherton TF, Joiner TE Jr. A 20-year longitudinal study of body weight, dieting, and eating disorder symptoms. J Abnormal Psychol (2007) 116(2):422. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.2.422

16. Cash TF. (2000) . Users’ Manual (3rd revision). www.body-images.com .

17. Vossbeck-Elsebusch AN, Waldorf M, Legenbauer T, Bauer A, Cordes M, Vocks S. German version of the Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire–Appearance Scales (MBSRQ-AS): confirmatory factor analysis and validation. Body Image (2014) 11(3):191–200. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.02.002

18. Brown TA, Cash TF, Mikulka PJ. Attitudinal body-image assessment: factor analysis of the Body-Self Relations Questionnaire. J Pers Assess (1990) 55(1–2):135–44. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674053

19. Avalos L, Tylka TL, Wood-Barcalow N. The body appreciation scale: development and psychometric evaluation. Body Image (2005) 2(3):285–97. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2005.06.002

20. Tiggemann M, McCourt A. Body appreciation in adult women: relationships with age and body satisfaction. Body Image (2013) 10(4):624–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2013.07.003

21. Duncan MJ, Al-Nakeeb Y, Nevill AM, Jones MV. Body dissatisfaction, body fat and physical activity in British children. Int J Pediatr Obesity (2006) 1(2):89–95. doi: 10.1080/17477160600569420

22. Paxton SJ, Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan PJ, Eisenberg ME. Body dissatisfaction prospectively predicts depressive mood and low self-esteem in adolescent girls and boys. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol (2006) 35(4):539–49. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3504_5

23. Schur EA, Sanders M, Steiner H. Body dissatisfaction and dieting in young children. Int J Eating Disord (2000) 27(1):74–82. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(200001)27:1<74::AID-EAT8>3.0.CO;2-K

24. Wood KC, Becker JA, Thompson JK. Body image dissatisfaction in preadolescent children. J Appl Dev Psychol (1996) 17(1):85–100. doi: 10.1016/S0193-3973(96)90007-6

25. Lewis DM, Cachelin FM. Body image, body dissatisfaction, and eating attitudes in midlife and elderly women. Eating Disord (2001) 9(1):29–39. doi: 10.1080/106402601300187713

26. Neumark-Sztainer D, Paxton SJ, Hannan PJ, Haines J, Story M. Does body satisfaction matter? Five-year longitudinal associations between body satisfaction and health behaviors in adolescent females and males. J Adolesc Health (2006) 39(2):244–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.12.001

27. Baker L, Gringart E. Body image and self-esteem in older adulthood. Ageing Soc (2009) 29(6):977–95. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X09008721

28. Esnaola I, Rodríguez A, Goñi A. Body dissatisfaction and perceived sociocultural pressures: gender and age differences. Salud Ment (2010) 33(1):21–9.

29. Fallon EA, Harris BS, Johnson P. Prevalence of body dissatisfaction among a United States adult sample. Eating Behav (2014) 15(1):151–8. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.11.007

30. Tiggemann M. Body image across the adult life span: stability and change. Body Image (2004) 1(1):29–41. doi: 10.1016/S1740-1445(03)00002-0

31. Allaz AF, Bernstein M, Rouget P, Archinard M, Morabia A. Body weight preoccupation in middle-age and ageing women: a general population survey. Int J Eating Disord (1998) 23(3):287–94. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199804)23:3<287::AID-EAT6>3.0.CO;2-F

32. Deeks AA, McCabe MP. Menopausal stage and age and perceptions of body image. Psychol Health (2001) 16(3):367–79. doi: 10.1080/08870440108405513

33. Frederick DA, Jafary AM, Gruys K, Daniels EA. Surveys and the epidemiology of body image dissatisfaction. In: Encyclopedia of body image and human appearance . Amsterdam: Academic Press (2012). p. 766–74.

34. Furnham A, Calnan A. Eating disturbance, self-esteem, reasons for exercising and body weight dissatisfaction in adolescent males. Eur Eating Disord Rev: Prof J Eating Disord Assoc (1998) 6(1):58–72. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0968(199803)6:1<58::AID-ERV184>3.0.CO;2-V

35. McCreary DR, Sasse DK. An exploration of the drive for muscularity in adolescent boys and girls. J Am Coll Health (2000) 48:297–304. doi: 10.1080/07448480009596271

36. Cafri G, Thompson JK, Ricciardelli L, McCabe M, Smolak L, Yesalis CPursuit of the muscular ideal: physical and psychological consequences and putative risk factors. Clin Psychol Rev (2005) 25(2):215–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.09.003

37. Cordes M. Körperbild bei Männern: Die Bedeutung körperbezogener selektiver Aufmerksamkeitsprozesse sowie körpermodifizierender Verhaltensweisen für die Entstehung und Aufrechterhaltung eines gestörten Körperbildes . [Doctoral dissertation] Osnabrück: Osnabrück University (2017).

38. Hoffmann S, Warschburger P. Weight, shape, and muscularity concerns in male and female adolescents: predictors of change and influences on eating concern. Int J Eating Disord (2017) 50:139–47. doi: doi.org/10.1002/eat.22635