An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

What are the key elements of a positive learning environment? Perspectives from students and faculty

Shayna a. rusticus.

Department of Psychology, Kwantlen Polytechnic University, 12666 72 Ave, Surrey, BC V3W 2M8 Canada

Tina Pashootan

The learning environment comprises the psychological, social, cultural and physical setting in which learning occurs and has an influence on student motivation and success. The purpose of the present study was to explore qualitatively, from the perspectives of both students and faculty, the key elements of the learning environment that supported and hindered student learning. We recruited a total of 22 students and 9 faculty to participate in either a focus group or an individual interview session about their perceptions of the learning environment at their university. We analyzed the data using a directed content analysis and organized the themes around the three key dimensions of personal development, relationships, and institutional culture. Within each of these dimensions, we identified subthemes that facilitated or impeded student learning and faculty work. We also identified and discussed similarities in subthemes identified by students and faculty.

Introduction

The learning environment (LE) comprises the psychological, social, cultural, and physical setting in which learning occurs and in which experiences and expectations are co-created among its participants (Rusticus et al., 2020 ; Shochet et al., 2013 ). These individuals, who are primarily students, faculty and staff, engage in this environment and the learning process as they navigate through their personal motivations and emotions and various interpersonal interactions. This all takes place within a physical setting that consists of various cultural and administrative norms (e.g. school policies).

While many studies of the LE have focused on student perspectives (e.g. Cayubit, 2021 ; Schussler et al., 2021 ; Tharani et al., 2017 ), few studies have jointly incorporated the perspectives of students and faculty. Both groups are key players within the educational learning environment. Some exceptions include researchers who have used both instructor and student informants to examine features of the LE in elementary schools (Fraser & O’Brien, 1985 ; Monsen et al., 2014 ) and in virtual learning and technology engaged environments in college (Annansingh, 2019 ; Downie et al., 2021 ) Other researchers have examined perceptions of both groups, but in ways that are not focused on understanding the LE (e.g. Bolliger & Martin, 2018 ; Gorham & Millette, 1997 ; Midgly et al., 1989 ).

In past work, LEs have been evaluated on the basis of a variety of factors, such as students’ perceptions of the LE have been operationalized as their course experiences and evaluations of teaching (Guo et al., 2021 ); level of academic engagement, skill development, and satisfaction with learning experience (Lu et al., 2014 ); teacher–student and student–peer interactions and curriculum (Bolliger & Martin, 2018 ; Vermeulen & Schmidt, 2008 ); perceptions of classroom personalization, involvement, opportunities for and quality of interactions with classmates, organization of the course, and how much instructors make use of more unique methods of teaching and working (Cayubit, 2021 ). In general, high-quality learning environments are associated with positive outcomes for students at all levels. For example, ratings of high-quality LEs have been correlated with outcomes such as increased satisfaction and motivation (Lin et al., 2018 ; Rusticus et al., 2014 ; Vermeulen & Schmidt, 2008 ), higher academic performance (Lizzio et al., 2002 ; Rusticus et al., 2014 ), emotional well-being (Tharani et al., 2017 ), better career outcomes such as satisfaction, job competencies, and retention (Vermeulen & Schmidt, 2008 ) and less stress and burnout (Dyrbye et al., 2009 ). From teacher perspectives, high-quality LEs have been defined in terms of the same concepts and features as those used to evaluate student perspective and outcomes. For example, in one quantitative study, LEs were rated as better by students and teachers when they were seen as more inclusive (Monsen et al., 2014 ).

However, LEs are diverse and can vary depending on context and, although many elements of the LE that have been identified, there has been neither a consistent nor clear use of theory in assessing those key elements (Schönrock-Adema et al., 2012 ). One theory that has been recommended by Schönrock-Adema et al. ( 2012 ) to understand the LE is Moos’ framework of human environments (Insel & Moos, 1974 ; Moos, 1973 , 1991 ). Through his study of a variety of human environments (e.g. classrooms, psychiatric wards, correctional institutions, military organizations, families), Moos proposed that all environments have three key dimensions: (1) personal development/goal direction, (2) relationships, and (3) system maintenance/change. The personal development dimension encompasses the potential in the environment for personal growth, as well as reflecting the emotional climate of the environment and contributing to the development of self-esteem. The relationship dimension encompasses the types and quality of social interactions that occur within the environment, and it reflects the extent to which individuals are involved in the environment and the degree to which they interact with, and support, each other. The system maintenance/change dimension encompasses the degree of structure, clarity and openness to change that characterizes the environment, as well as reflecting physical aspects of the environment.

We used this framework to guide our research question: What do post-secondary students and faculty identify as the positive and negative aspects of the learning environment? Through the use of a qualitative methodology to explore the LE, over the more-typical survey-based approaches, we were able to explore this topic in greater depth, to understand not only the what, but also the how and the why of what impacts the LE. Furthermore, in exploring the LE from both the student and faculty perspectives, we highlight similarities and differences across these two groups and garner an understanding of how both student and faculty experience the LE.

Participants

All participants were recruited from a single Canadian university with three main campuses where students can attend classes to obtain credentials, ranging from a one-year certificate to a four-year undergraduate degree. Approximately 20,000 students attend each year. The student sample was recruited through the university’s subject pool within the psychology department. The faculty sample was recruited through emails sent out through the arts faculty list-serve and through direct recruitment from the first author.

The student sample was comprised of 22 participants, with the majority being psychology majors ( n = 10), followed by science majors ( n = 4) and criminology majors ( n = 3). Students spanned all years of study with seven in their first year, three in second year, five in third year, six in fourth year, and one unclassified. The faculty sample consisted of nine participants (6 male, 3 female). Seven of these participants were from the psychology department, one was from the criminology department and one was from educational studies. The teaching experience of faculty ranged from 6 to 20 years.

Interview schedule and procedure

We collected student data through five focus groups and two individual interviews. The focus groups ranged in size from two to six participants. All sessions occurred in a private meeting room on campus and participants were provided with food and beverages, as well as bonus credit. Each focus group/interview ranged from 30 to 60 min. We collected all faculty data through individual interviews ranging from 30 to 75 min. Faculty did not receive any incentives for their participation. All sessions were conducted by the first author, with the second author assisting with each of the student focus groups.

With the consent of each participant, we audio-recorded each session and transcribed them verbatim. For both samples, we used a semi-structured interview format involving a set of eight open-ended questions about participants’ overall perceptions of the LE at their institution (see Appendix for interview guide). These questions were adapted from a previous study conducted by the first author (Rusticus et al., 2020 ) and focused on how participants defined the LE, what they considered to be important elements of the LE, and their positive and negative experiences within their environment. Example questions were: “Can you describe a [negative/positive] learning [students]/teaching [faculty] experience that you have had?”.

We analyzed the data using a directed content analysis approach (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005 ) that used existing theory to develop the initial coding scheme. We used Moos’s (Insel & Moos, 1974 ; Moos, 1973 , 1991 ) framework and its three dimensions of personal development, relationships, and system maintenance/change to guide our analysis. During the analysis phase, we renamed the system maintenance/change dimension to ‘institutional setting’ as we felt it was more descriptive of, and better represented, the content of this theme.

We analyzed student and faculty data separately, starting with the student data, but used the same process for both. First, we randomly selected two transcripts. We each independently coded the first transcript using the broad themes of personal development, relationships and institutional setting, and developed subcodes within each of these themes, as needed. We then reviewed and discussed our codes, reaching consensus on any differences in coding. We then repeated this process for the second transcript and, through group discussions, created a codebook. The first author then coded the remaining transcripts.

When coding the faculty data, we aimed to maintain subcodes similar to the student data while allowing for flexibility when needed. For instance, within the personal development theme, a subcode for the student data was ‘engagement with learning’, whereas a parallel subcode for the faculty data was ‘engagement with teaching’.

We present the results of the student and faculty data separately. For both, we have organized our analysis around the three overarching themes of personal development, relationships and institutional setting.

Student perspectives of the learning environment

Personal development.

Personal development was defined as any motivation either within or outside the LE that provide students with encouragement, drive, and direction for their personal growth and achievement. Within this theme, there were two subthemes: engaging with learning and work-life balance.

Engagement with learning reflected a student’s desire and ability to participate in their learning, as opposed to a passive-learning approach. Students felt more engaged when they were active learners, as well as when they perceived the material to be relevant to their career goals or real-world applications. Students also said that having opportunities to apply their learning helped them to better understand their own career paths:

I had two different instructors and both of them were just so open and engaging and they shared so many personal stories and they just seemed so interested in what they were doing and what I was like. Wow, I want to be that. I want to be interested in what I’m learning. (G6P1)

A common complaint that negatively impacted student motivation was that instructors would lecture for the entire class without supporting materials or opportunities for students to participate.

I’ve had a couple professors who just don’t have any visuals at all. All he does is talk. So, for the whole three hours, we would just be scrambling to write down the notes. It’s brutal...(G7P2)

Trying to establish a healthy work-life balance and managing the demands of their courses, often in parallel with managing work and family demands, were key challenges for students and were often sources of stress and anxiety. For instance, one student spoke about her struggles in meeting expectations:

It was a tough semester. For the expectations that I had placed on myself, I wasn’t meeting them and it took a toll on me. But now I know that I can exceed my expectations, but you really have to try and work hard for it. (G6P1)

Achieving a good work-life balance and adjusting to university life takes time. Many students commented that, as they reached their third year of study, they felt more comfortable in the school environment. Unfortunately, students also noted that the mental and emotional toll of university life can lead to doubt about the future and a desire to leave. One student suggested more support for students to help with this adjustment:

I think school should give students more service to help them to overcome the pressure and make integration into the first year and second year quicker and faster. Maybe it’s very helpful for the new students. (G7P4)

Relationships

Relationships was the second dimension of the LE. Subthemes within this dimension included: faculty support, peer interaction, and group work. Most students commented on the impact that faculty had on their learning. Faculty support included creating a safe or unsafe space in the classroom (i.e. ability to ask questions without judgement, fostering a respectful atmosphere), providing additional learning material, accommodating requests, or simply listening to students. Students generally indicated that faculty at this university were very willing to offer extra support and genuinely cared for them and their education. Faculty were described as friendly and approachable, and their relationships with students were perceived as “egalitarian”.

I think feeling that you’re safe in that environment, that anything you pose or any questions that you may have, you’re free to ask. And without being judged. And you’ll get an answer that actually helps you. (G1P4)

While most students felt welcome and comfortable in their classes, a few students spoke about negative experiences that they had because of lack of faculty support. Students cited examples of professors “shutting down” questions, saying that a question was “stupid”, refusing requests for additional help, or interrupting them while speaking. Another student felt that the inaction of faculty sometimes contributed to a negative atmosphere:

I’ve had bad professors that just don't listen to any comment or, if you suggest something to improve it which may seem empirically better, they still shut you down! That’s insane. (G2P2)

The peer interactions subtheme referred to any instances when students could interact with other students; this occurred both in and out of the classroom. Most often, students interacted with their peers during a class or because of an assignment:

I think the way the class is structured really helps you build relationships with your peers. For example, I met S, we had several classes with each other. Those classes were more proactive and so it allowed us to build a relationship… I think that’s very important because we’re going to be in the same facility for a long time and to have somebody to back you up, or to have someone to study with…”. (G1P4)

However, other students felt that they lacked opportunities to interact with peers in class. Although a few participants stated that they felt the purpose of going to school was to get a degree, rather than to socialize with others, students wanted more opportunities to interact with peers.

The final subtheme, group work, was a very common activity at this school. The types of group work in which students engaged included classroom discussions, assignments/projects, and presentations. Many students had enjoyable experiences working in groups, noting that working together helped them to solve problems and create something that was better than one individual’s work. Even though sometimes doing the work itself was a negative experience, people still saw value in group work:

Some of the best memories I’ve ever had was group work and the struggles we've had. (G2P2) I don’t like group work but it taught me a lot, I’ve been able to stay friends and be able to connect with people that I’ve had a class with in 2nd year psych all the way up till now. I think that’s very valuable. (G6P1)

Almost all students who spoke about group work also talked about negative aspects or experiences they had. When the work of a group made up a large proportion of the final grade, students sometimes would have preferred to be evaluated individually. Students disliked when they worked in groups when members were irresponsible or work was not shared equally, and they were forced to undertake work that other students were not completing.

A lot of people don’t really care, or they don’t take as much responsibility as you. I think people have different goals and different ways of working, so sometimes I find that challenging. (G7P2)

Institutional setting

The third overarching theme was the institutional setting. Broadly, this theme refers to the physical structure, expectations, and the overall culture of the environment and was composed of two key subthemes: importance of small class sizes; and the lack of a sense of community.

Small class sizes, with a maximum of 35 students, were a key reason why many students chose to come to this institution. The small classes created an environment in which students and faculty were able to get to know one another more personally; students felt that they were known as individuals, not just as numbers. They also noted that this promoted greater feelings of connectedness to the class environment, more personalized attention, and opportunities to request reference letters in the future:

My professors know my name. Not all of them that I’m having for the first time ever, but they try… That means a lot to me. (G6P4)

Several students also said that having smaller class sizes helped them to do well in their courses. The extra attention encouraged them to perform better academically, increased their engagement with their material, and made them feel more comfortable in asking for help.

Having a sense of belonging was a key feature of the environment and discussions around a sense of community (or lack thereof) was a prominent theme among the students. Students generally agreed that the overall climate of the school is warm and friendly. However, many students referred to the institution as a “commuter school”, because there are no residencies on campus and students must commute to the school. This often resulted in students attending their classes and then leaving immediately after, contributing to a lack of community life on campus.

What [other schools] have is that people live on campus. I think that plays a huge role. We can’t ignore that we are a commuter school… They have these events and people go because they’re already there and you look at that and it seems to be fun and engaging. (G4P1)

Furthermore, students commented on a lack of campus areas that supported socialization and encouraged students to remain on campus. While there were events and activities that were regularly hosted at the school, students had mixed opinions about them. Some students attended the events and found them personally beneficial. Other students stated that, although many events and activities were available, turnout was often low:

There isn’t any hanging out after campus and you can even see in-events and in-event turnout for different events… It is like pulling teeth to get people to come out to an event… There are free food and fun music and really cool stuff. But, no one’s going to go. It’s sad. (G5P1)

Faculty perspectives on the learning environment

Similar to the student findings, faculty data were coded within the three overarching themes of personal development, relationships, and institutional setting.

Personal development reflected any motivation either within or outside the LE that provided faculty with the encouragement, drive, and direction for their personal growth and engagement with teaching. Within this dimension, there were two main subthemes: motivation to teach and emotional well-being.

As with any career, there are many positive and negative motivating factors that contribute to one’s involvement in their work. Faculty generally reported feeling passionate about their work, and recounted positive experiences they have had while teaching, both personally and professionally. While recollecting positive drives throughout their career, one instructor shared:

It’s [teaching in a speciality program] allowed me to teach in a very different way than the traditional classroom… I’ve been able to translate those experiences into conferences, into papers, into connections, conversations with others that have opened up really interesting dialogues…. (8M)

Faculty also reported that receiving positive feedback from students or getting to see their students grow over time was highly motivating:

I take my teaching evaluations very seriously and I keep hearing that feedback time and time again they feel safe. They feel connected, they feel listened too, they feel like I'm there for them. I think, you know, those are the things that let me know what I'm doing is achieving the goals that I have as an educator. (1F) Being able to watch [students] grow over time is very important to me… I always try to have a few people I work with and see over the course of their degree. So, when they graduate, you know I have a reason to be all misty-eyed. (2M)

Emotional well-being related to how different interactions, primarily with students, affected instructors’ mental states. Sometimes the emotional well-being of faculty was negatively affected by the behaviour of students. One instructor spoke about being concerned when students drop out of a class:

A student just this last semester was doing so well, but then dropped off the face of the earth… I felt such a disappointing loss… So, when that happens, I'm always left with those questions about what I could have done differently. Maybe, at the end of the day, there is nothing I could've done, nothing. It's a tragedy or something's happened in their life or I don't know. But those unanswered questions do concern-- they cause me some stress or concern. (1F)

Another instructor said that, while initially they had let the students’ behaviour negatively affect their well-being, over time, they had eventually become more apathetic.

There are some who come, leave after the break. Or they do not come, right, or come off and on. Previously I was motivated to ask them ‘what is your problem?’ Now I do not care. That is the difference which has happened. I do not care. (4M)

This dimension included comments related to interactions with other faculty and with students and consisted of three subthemes: faculty supporting faculty; faculty supporting students; and creating meaningful experiences for students.

Most faculty felt that it was important to be supported by, and supportive to, their colleagues. For instance, one instructor reported that their colleagues’ helpfulness inspired them to be supportive of others:

If I was teaching a new course, without me having to go and beg for resources or just plead and hope that someone might be willing to share, my experience was that the person who last taught the course messaged me and said let me know if anything I have will be useful to you… When people are willing to do that for you, then you’re willing to do that for someone else….(7M)

Many faculty members also spoke about the importance of having supportive relationships with students, and that this would lead to better learning outcomes:

If you don't connect with your students, you're not going to get them learning much. They're not; they're just going to tune out. So, I think, I think connection is critical to having a student not only trust in the learning environment, but also want to learn from the learning environment. (3M)

Facilitating an open, inviting space in the classroom and during their office hours, where students were comfortable asking questions, was one way that faculty tried to help students succeed. Faculty also spoke about the value of having close mentorship relationships with students:

I work with them a lot and intensively…and their growth into publishing, presenting, and seeing them get recognized and get jobs on their way out and so forth are extraordinary. So, being able to watch them grow over time is very important to me. (2M)

Faculty also noted that occasionally there were instances when students wanted exceptions to be made for them which can create tensions in the environment. One instructor spoke about the unfairness of those requests arguing that students need to be accountable to themselves:

The failure rate, …it was 43%. I do not know if there is any other course in which there is a 43% failure rate. So, I do not want to fail these students, why? Instructors want these students to pass, these are my efforts […], and there are also the efforts of these students and their money, right? But, if a student doesn’t want to pass himself or herself, I cannot pass this student, that’s it. (4M)

Faculty were generally motivated to provide memorable and engaging experiences for students. These included providing practical knowledge and opportunities to apply knowledge in real-world settings, field schools, laboratory activities, group discussions, guest speakers, field trips, videos and group activities. They were often willing to put in extra effort if it meant that students would have a better educational experience.

Creating meaningful experiences for students was also meaningful for faculty. One faculty member said that faculty felt amazing when the methods that they used in their courses were appreciated by students. Another faculty member noted:

This student who was in my social psychology class, who was really bright and kind of quirky, would come to my office, twice a week, and just want to talk about psychology … That was like a really satisfying experience for me to see someone get so sparked by the content. (9F)

This third theme refers to the physical structure, expectation, and overall culture of the environment and it consisted of two subthemes: the importance of small class sizes, and the lack of a sense of community.

The majority of the faculty indicated that the small class sizes are an integral feature of the LE. The key advantage of the small classes was that they allowed greater connection with students.

Your professor knows your name. That’s a huge difference from other schools. It’s a small classroom benefit. (6F)

Similar to the students, nearly all the faculty indicated that a sense of community at the institution was an important part of the environment, and something that was desired, but it currently was lacking. They spoke about various barriers which prevent a sense of community, such as the lack of residences, a dearth of events and activities at the university, the busy schedules of faculty and students, the commuter nature of the school, and characteristics of the student population:

When I complain about the commuter campus feeling that occurs with students, we suffer from that too at a faculty level… People are just not in their offices because we work from home… And that really also affects the culture… We come in. We do our thing. We meet with students. And then we leave… I encounter so many students in the hallway who are looking for instructors and they can’t find them. (9F)

These findings have provided insight into the perspectives of both students and faculty on the LE of a Canadian undergraduate university. We found that framing our analysis and results within Moos’ framework of human environments (Insel & Moos, 1974 ; Moos, 1973 , 1991 ) was an appropriate lens for the data and that the data fit well within these three themes. This provides support for the use of this theory to characterize the educational LE. Within each of these dimensions, we discuss subthemes that both facilitated and hindered student learning and commonalities among student and faculty perspectives.

Within the personal development dimension, both students and faculty discussed the importance of engagement and/or motivation as a facilitator of a positive LE. When students were engaged with their learning, most often by being an active participant or seeing the relevance of what they were learning, they saw it as a key strength. Other studies have also identified engagement as a feature of positive LEs for populations such as high-school students (Seidel, 2006 ), nursing students (D’Souza et al., 2013 ) and college students taking online courses (e.g. Holley & Dobson, 2008 ; O’Shea et al., 2015 ). Faculty who reported being motivated to teach, often felt that this motivation was fueled by the reactions of their students; when students were engaged, they felt more motivated. This creates a positive cyclic pattern in which one group feeds into the motivation and engagement levels of the other. However, this can also hinder the LE when a lack of engagement in one group can bring down the motivation of the other group (such as students paying more attention to their phones than to a lecture or faculty lecturing for the entire class period).

Emotional climate was another subtheme within the personal development dimension that was shared by both students and faculty although, for students, this was focused more on the stress and anxiety that they felt trying to manage their school workloads with their work and family commitments. The overall emotional climate of the school was generally considered to be positive, which was largely driven by the supportive and welcoming environment provided by the faculty. However, it was the negative emotions of stress and anxiety that often surfaced as a challenging aspect in the environment for students. Past research suggests that some types of stress, such as from a challenge, can improve learning and motivation, but negative stress, such as that reported by our participants, is associated with worsened performance and greater fatigue (LePine et al., 2004 ).

For faculty, their emotional state was often influenced by their students. When things were going well for their students, faculty often shared in the joy; however, when students would disappear without notice from a class, it was a source of disappointment and self-doubt. For other faculty, the accumulation of negative experiences resulted in them being more distant and less affected emotionally than they had been earlier in their career. This diminishing concern could have implications for how engaged faculty are in their teaching, which could in turn influence student engagement and harm the LE.

The relationships dimension was the most influential aspect of the environment for both students and faculty. While both groups felt that the relationships that they formed were generally positive, they also reported a desire for more peer connections (i.e. students with other students and faculty with other faculty). Students commented that it was a typical experience for them to come to campus to attend their classes and then leave afterwards, often to work or study at home. Many of the students at this school attend on a part-time basis while they work part- or full-time and/or attend to family commitments. While this is a benefit to these students to have the flexibility to work and further their education, it comes at loss of the social aspect of post-secondary education.

The one way in which student–peer relationships were fostered was through group work. However, students held both positive and negative views on this: the positive aspect was the opportunity to get to know other students and being able to share the burden of the workload, and the negative aspect was being unfair workloads among team members. When group dynamics are poor, such as unfair work distribution, having different goals and motivations, or not communicating effectively with their groups, it has been shown to lead to negative experiences (Rusticus & Justus, 2019 ).

Faculty also commented that it was typical for them and other faculty to come up to campus only to teach their classes and then leave afterwards. They noted that their office block was often empty and noted instances when students have come looking for faculty only to find a locked office. Overall, faculty did report feeling congenial with, and supported by, their peers. They also desired a greater connection with their peers, but noted that it would require effort to build, which many were not willing to make.

Finally, student–faculty relationships were the most-rewarding experience for both groups. Students saw these experiences as highly encouraging and felt that they created a safe and welcoming environment where they could approach faculty to ask questions and get extra support. However, in some cases, students had negative experiences with faculty and these had an impact on their self-esteem, motivation and willingness to participate in class. Students’ negative experiences and feedback have been shown to result in declined levels of intrinsic motivation, even if their performance ability is not low (Weidinger et al., 2016 ).

Within the third dimension, institutional setting, a key strength was the small class sizes. With a maximum class size of 35 students, this created a more personal and welcoming environment for students. Students felt that their instructors got to know their names and this promoted more opportunities for interactions. Faculty concurred with this, indicating that the small classes provided greater opportunities for interactions with their students. This enabled more class discussions and grouped-based activities which contributed to a more engaging and interactive educational experience for students and faculty. For students, not being able to hide in the crowd of a large lecture hall, as is common in other university settings, encouraged them to work harder on their studies and to seek help from their instructor if needed.

Finally, both students and faculty commented that the lack of a sense of community was a negative aspect of the LE. This institution is known as a commuter school and both groups reported that they would often attend campus only for school/work and would leave as soon as their commitments were done. This limits opportunities to interact with others and could also potentially impact one’s identity as a member of this community. While both groups expressed a desire for more of a community life, neither group was willing to put in much effort to make this happen. Others have also found that sense of community, including opportunities to engage and interact with others, is important in LEs (e.g. Sadera et al., 2009 ). Schools with more activities and opportunities for student involvement have reports of higher satisfaction for both academic and social experiences (Charles et al., 2016 ).

Limitations

Because this study is based on a relatively small sample at a single university, there is a question of whether the findings can be applied to other departments, universities or contexts. However, it is a strength of this study that both student and faculty perceptions were included, because few past studies have jointly looked at these two groups together using qualitative methods. The use of focus groups among the student groups might have limited the openness of some participants. We also acknowledge that the analysis of qualitative data is inevitably influenced by our roles, life experiences and backgrounds. (The first author is a faculty member and the second and third authors were fourth year students at the time of the study.) This might have impacted our approach to the interpretation of the data compared with how others might approach the data and analysis (Denzin & Lincoln, 2008 ). However, the analysis involved consultation among the research team to identify and refine the themes, and the findings are presented with quotes to support the interpretation. Finally, because experiences were self-reported in this study, they have the associated limitations of self-report data. Despite these limitations, we believe that our findings add to what is known about LEs by capturing multiple perspectives within the same environment.

Future directions

Because our sample was comprised of students across multiple years of their program, some of our findings suggest that upper-level students might have different perceptions of the LE from lower-level students (e.g. work/life balance, access to resources, and overall familiarity with the environment and resources available). However, because the small sample sizes within these subgroups prevent any strong conclusions being made, future researchers might want to explore year-of-study differences in the LE. Additionally, the data collected for this study occurred prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and the mandatory switch to online teaching and learning. Future researchers might want to consider how this has impacted student and faculty perceptions of the LE regarding their personal motivation, the nature and quality of the relationships that have formed with peers and faculty, and the culture and norms of their institution.

This study increases our understanding of LEs by incorporating data collected from both students and faculty working in the same context. Across both groups, we identified important aspects of the LE as being high levels of engagement and motivation, a positive emotional climate, support among peers, strong faculty–student relationships, meaningful experiences, and small class sizes. Students identified negative aspects of the LE, such as certain characteristics of group work and struggles with work–life balance. Both faculty and students identified a lack of a sense of community as something that could detract from the LE. These findings identify important elements that educators and researchers might want to consider as they strive to promote more-positive LEs and learning experiences for students.

Appendix: Interview guide

[Faculty] Tell me a little bit about yourself. For instance, what department you are in, how long you have been teaching at KPU, what courses you teach, why you were interested in this study

- When I say the word learning environment, what does that mean to you?

- Probe for specific examples

- Relate to goal development, relationships, KPU culture

- Probe for factors that made it a positive environment

- Probe for factors that made it a negative environment

- How would you describe an ideal environment?

- Probe for reasons why

- Probe for how KPU could be made more ideal

- What recommendations would you give to the Dean of Arts regarding the learning environment? This could be changes you would recommend or things you recommend should stay the same.

- Do you have any final comments? Or feel there is anything about the learning environment that we have not addressed?

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- Annansingh F. Mind the gap: Cognitive active learning in virtual learning environment perception of instructors and students. Education and Information Technologies. 2019; 24 (6):3669–3688. doi: 10.1007/s10639-019-09949-5. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bolliger DU, Martin F. Instructor and student perceptions of online student engagement strategies. Distance Education. 2018; 39 (4):568–583. doi: 10.1080/01587919.2018.1520041. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cayubit RFO. Why learning environment matters? An analysis on how the learning environment influences the academic motivation, learning strategies and engagement of college students. Learning Environments Research. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10984-021-09382-x. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Charles CZ, Fischer MJ, Mooney MA, Massey DS. Taming the river: Negotiating the academic, financial, and social currents in selective colleges and universities. Princeton University Press; 2016. [ Google Scholar ]

- D’Souza MA, Venkatesaperumal R, Radhakrishnan J, Balachandran S. Engagement in clinical learning environment among nursing students: Role of nurse educators. Open Journal of Nursing. 2013; 31 (1):25–32. doi: 10.4236/ojn.2013.31004. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. Collecting and interpreting qualitative materials. Sage; 2008. [ Google Scholar ]

- Downie S, Gao X, Bedford S, Bell K, Kuit T. Technology enhanced learning environments in higher education: A cross-discipline study on teacher and student perceptions. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice. 2021; 18 (4):12–21. doi: 10.53761/1.18.4.12. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Harper W, Massie FS, Jr, Power DV, Eacker A, Szydlo DW, Novotny PJ, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. The learning environment and medical student burnout: A multicentre study. Medical Education. 2009; 43 (3):274–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03282.x. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fraser BJ, O'Brien P. Student and teacher perceptions of the environment of elementary school classrooms. The Elementary School Journal. 1985; 85 (5):567–580. doi: 10.1086/461422. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gorham J, Millette DM. A comparative analysis of teacher and student perceptions of sources of motivation and demotivation in college classes. Communication Education. 1997; 46 (4):245–261. doi: 10.1080/03634529709379099. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Guo JP, Yang LY, Zhang J, Gan YJ. Academic self-concept, perceptions of the learning environment, engagement, and learning outcomes of university students: Relationships and causal ordering. Higher Education. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10734-021-00705-8. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Holley D, Dobson C. Encouraging student engagement in a blended learning environment: The use of contemporary learning spaces. Learning, Media and Technology. 2008; 33 (2):139–150. doi: 10.1080/17439880802097683. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005; 15 :1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Insel PM, Moos RH. Psychological environments: Expanding the scope of human ecology. American Psychologist. 1974; 29 :179–188. doi: 10.1037/h0035994. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- LePine JA, LePine MA, Jackson CL. Challenge and hindrance stress: Relationships with exhaustion, motivation to learn, and learning performance. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2004; 89 (5):883–891. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.89.5.883. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lin S, Salazar TR, Wu S. Impact of academic experience and school climate of diversity on student satisfaction. Learning Environments Research. 2018; 22 :25–41. doi: 10.1007/s10984-018-9265-1. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lizzio A, Wilson K, Simons R. University students’ perceptions of the learning environment and academic outcomes: Implications for theory and practice. Studies in Higher Education. 2002; 27 :27–52. doi: 10.1080/03075070120099359. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lu G, Hu W, Peng Z, Kang H. The influence of undergraduate students’ academic involvement and learning environment on learning outcomes. International Journal of Chinese Education. 2014; 2 (2):265–288. doi: 10.1163/22125868-12340024. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Midgley C, Feldlaufer H, Eccles JS. Student/teacher relations and attitudes toward mathematics before and after the transition to junior high school. Child Development. 1989; 60 (4):981–992. doi: 10.2307/1131038. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Monsen JJ, Ewing DL, Kwoka M. Teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion, perceived adequacy of support and classroom learning environment. Learning Environments Research. 2014; 17 :113–126. doi: 10.1007/s10984-013-9144-8. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Moos RH. Conceptualizations of human environments. American Psychologist. 1973; 28 :652–665. doi: 10.1037/h0035722. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Moos RH. Connections between school, work and family settings. In: Fraser BJ, Walberg HJ, editors. Educational environments: Evaluation, antecedents and consequences. Pergamon Press; 1991. pp. 29–53. [ Google Scholar ]

- O’Shea S, Stone C, Delahunty J. “I ‘feel’ like I am at university even though I am online.” Exploring how students narrate their engagement with higher education institutions in an online learning environment. Distance Education. 2015; 36 (1):41–58. doi: 10.1080/01587919.2015.1019970. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rusticus SA, Justus B. Comparing student- and teacher-formed teams on group dynamics, satisfaction and performance. Small Group Research. 2019; 50 (4):443–457. doi: 10.1177/1046496419854520. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rusticus, S. A., Wilson, D., Casiro, O., & Lovato, C. (2020). Evaluating the quality of health professions learning environments: development and validation of the health education learning environment survey (HELES). Evaluation & the health professions, 43 (3), 162–168. 10.1177/0163278719834339 [ PubMed ]

- Rusticus SA, Worthington A, Wilson DC, Joughin K. The Medical School Learning Environment Survey: An examination of its factor structure and relationship to student performance and satisfaction. Learning Environments Research. 2014; 17 :423–435. doi: 10.1007/s10984-014-9167-9. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sadera WA, Robertson J, Song L, Midon MN. The role of community in online learning success. Journal of Online Learning and Teaching. 2009; 5 (2):277–284. [ Google Scholar ]

- Schönrock-Adema J, Bouwkamp-Timmer T, van Hell EA, Cohen-Schotanus J. Key elements in assessing the educational environment: Where is the theory? Advances in Health Sciences Education. 2012; 17 :727–742. doi: 10.1007/s10459-011-9346-8. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schussler, E. E., Weatherton, M., Chen Musgrove, M. M., Brigati, J. R., & England, B. J. (2021). Student perceptions of instructor supportiveness: What characteristics make a difference? CBE—Life Sciences Education , 20 (2), Article 29. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]

- Seidel T. The role of student characteristics in studying micro teaching–learning environments. Learning Environments Research. 2006; 9 (3):253–271. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2005.08.004. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Shochet RB, Colbert-Getz JM, Levine RB, Wright SM. Gauging events that influence students’ perceptions of the medical school learning environment: Findings from one institution. Academic Medicine. 2013; 88 :246–252. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31827bfa14. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tharani A, Husain Y, Warwick I. Learning environment and emotional well-being: A qualitative study of undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Education Today. 2017; 59 :82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2017.09.008. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Vermeulen L, Schmidt HG. Learning environment, learning process, academic outcomes and career success of university graduates. Studies in Higher Education. 2008; 33 (4):431–451. doi: 10.1080/03075070802211810. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Weidinger AF, Spinath B, Steinmayr R. Why does intrinsic motivation decline following negative feedback? The mediating role of ability self-concept and its moderation by goal orientations. Learning and Individual Differences. 2016; 47 :117–128. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2016.01.003. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

Essay on Enabling Learning Environment

Students are often asked to write an essay on Enabling Learning Environment in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Enabling Learning Environment

Understanding a learning environment.

A learning environment refers to the diverse physical locations, contexts, and cultures in which we learn. It’s not just about the classroom, but also includes homes, parks, or even virtual spaces.

Importance of a Learning Environment

A good learning environment is crucial because it can help students feel safe, comfortable, and engaged, making it easier for them to learn. It also encourages positive social interaction among students.

Creating an Enabling Learning Environment

Teachers can create an enabling learning environment by arranging the classroom in a way that promotes interaction and collaboration. They can also use technology to enhance learning.

Benefits of an Enabling Learning Environment

An enabling learning environment can improve student performance and motivation. It can also help students develop important skills such as critical thinking and problem-solving.

250 Words Essay on Enabling Learning Environment

Introduction.

An enabling learning environment is a setting in which all students feel empowered, engaged, and capable of high academic achievement. It is not merely about the physical space, but also about how the environment is structured and the pedagogical strategies employed.

Physical and Virtual Aspects

A physically enabling environment is well-resourced, safe, and comfortable. It should be flexible to accommodate various learning styles and activities. In the digital age, virtual environments such as online learning platforms also play a crucial role. They should be user-friendly, interactive, and accessible to all students.

Social and Emotional Climate

The social-emotional climate is equally important. A positive climate is characterized by respect, trust, and mutual understanding between teachers and students. It promotes collaboration, reduces fear of failure, and encourages risk-taking in learning.

Teaching and Learning Approaches

Effective teaching strategies are central to an enabling environment. These should be learner-centered, promoting active engagement and critical thinking. Differentiation and personalization of instruction are key to cater to individual learning needs.

In conclusion, an enabling learning environment is a multifaceted concept that involves physical and virtual aspects, a positive social-emotional climate, and effective teaching strategies. It is crucial for promoting high academic achievement and fostering a lifelong love for learning.

500 Words Essay on Enabling Learning Environment

An enabling learning environment is a critical element in the educational process. It is a space that fosters a positive atmosphere conducive to learning, where students feel safe, comfortable, and engaged. It goes beyond the physical classroom and includes emotional, social, and academic support.

The Concept of an Enabling Learning Environment

An enabling learning environment is not just about having a well-equipped classroom. It is an environment that encourages students to engage, explore, and learn. It is a space where students feel respected and valued, promoting their self-esteem and confidence. This environment also encourages the development of critical thinking skills, creativity, and innovation.

Components of an Enabling Learning Environment

The enabling learning environment consists of various components. The physical environment includes the classroom’s layout, lighting, temperature, and noise levels. The emotional environment involves the relationships among students and between students and teachers. The pedagogical environment includes teaching methods, curriculum, and assessment.

Creating an enabling learning environment requires thoughtful planning and execution. It involves setting clear expectations, fostering a sense of belonging, encouraging student engagement, and providing effective feedback.

The teacher plays a crucial role in creating this environment. They should promote diversity and inclusion, ensuring that all students feel valued and respected. Additionally, they should use teaching methods that cater to different learning styles, providing a variety of learning opportunities.

The Impact of an Enabling Learning Environment

An enabling learning environment has a profound impact on students’ learning outcomes. It enhances students’ motivation and engagement, leading to improved academic performance. It also promotes social and emotional development, fostering skills such as communication, collaboration, and self-regulation.

Challenges in Creating an Enabling Learning Environment

Despite its importance, creating an enabling learning environment is not without challenges. These include managing diverse learning needs, dealing with disruptive behavior, and maintaining a balance between academic demands and students’ well-being.

In conclusion, an enabling learning environment is a fundamental aspect of effective education. It requires a holistic approach, taking into account the physical, emotional, and pedagogical aspects of the learning environment. Despite the challenges, it is crucial for educators to strive to create such an environment to foster students’ academic success and personal growth.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on World Environment Day

- Essay on Lifestyle for Environment

- Essay on Discipline In The Classroom

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

Shaping a Positive Learning Environment

Several years ago, American surgeon, author, and public health researcher Atul Gawande experimented with using a two-minute checklist in operating rooms in eight different hospitals. One unexpected result was that a round of team-member introductions before surgery lowered the average number of surgical complications by 35%. Learning names and building a positive environment at the outset of this short-term medical community experience made huge impacts on their ability to function effectively together. How might we apply this and other community-building principles to establish positive learning environments that facilitate student learning?

Learning is an emotional process—we feel excitement when learning a new skill, embarrassment about mistakes, and fear of being misunderstood. Fostering positive emotions in your classroom will motivate students to learn, while negative emotions such as stress and alienation will inhibit their learning.

Research tells us students learn better when they are part of a supportive community of learners. When you create a positive learning environment where students feel accepted, seen, and valued, they are more likely to persist in your course, in their majors, and at the university.

In How Learning Works: Seven Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching , Susan Ambrose et al. address the many and complex factors that influence learning environments, including intellectual, social, emotional, and physical (2010).

They offer a few key takeaways for educators:

Learning doesn’t happen in a vacuum. Your classroom community is made up of individuals with diverse identities, backgrounds, and experiences; the act of learning is intertwined with a variety of socioemotional influences.

Classroom climate is determined by both intentional and unintentional actions, and by both explicit and implicit messages. And their impact on students is not always obvious. Seemingly well-meaning or unimportant choices and remarks can have unintended effects on student learning.

The good news: You have more control over the learning environment in your courses than you might guess. If you know how learning environments influence student learning, you can employ a variety of strategies to consciously shape a welcoming and inclusive classroom.

Sense of Belonging in College

In a welcoming and inclusive classroom, students are more likely to feel a sense of belonging . A sense of belonging is a basic human need. That is, everyone needs to belong. In the college context, sense of belonging refers to whether or not students feel respected, accepted, valued, included, cared for, and that they matter—in your classroom, at the university, or in their chosen career path (Strayhorn, 2012).

Although everyone needs to belong, students’ feelings of comfort in your class largely depends on their identities and experiences (Strayhorn, 2012; Walton & Cohen, 2007). Being the only student, or one of a few, of a particular identity group can lead students to feel detached, apathetic, or reluctant to participate. They may feel marginalized by the course content or by other students’ comments.

Indeed, research shows that minoritized students tend to report a lower sense of belonging than their peers (Johnson et al., 2007; Strayhorn, 2008a). Academic performance or preparation can also raise or lower students’ perceived sense of belonging (Hoops, Green, Baker, & Hensley, 2016; Strayhorn, 2008b; Zumbrunn, McKim, Buhs, & Hawley, 2014). Particularly for minoritized students, academic struggle can be internalized as a sign that they do not belong (Walton & Cohen, 2007).

Research by DeSurra and Church in 1994 provides a spectrum for understanding learning environments that ranges from explicitly marginalizing, where the course climate is openly hostile and cold, to explicitly centralizing, where multiple perspectives are validated and integrated into the course. While this particular research was based on sexual orientation, the earliest research on learning environments—the “chilly climate studies”—focused on gender and had similar findings (Hall, 1982; Hall & Sandler, 1984; and Sandler & Hall, 1986). These early studies demonstrated that marginalization of students does not require an openly hostile environment. Rather, the accumulation of microaggressions alone can adversely impact learning. Later studies showed similar effects based on the race and ethnicity of students (Hurtado et al., 1999; Watson et al., 2002).

Diversity and Inclusion

Students, like all of us, are complex human beings—they have a gender, race, class, nationality, sexual orientation, and other axes of identity. These overlapping identities mean that an individual may face multiple barriers at once to feeling welcome in your class. Rather than thinking your course should support “a” student of color or “a” student with a disability, craft a learning environment that is welcoming to as many students—and their complexities—as possible.

Students struggling with sense of belonging are less engaged. They may sit in the back of class, be inattentive during lecture, or avoid participation in discussion or group activities. They may even skip class or show up late more often than others. However, sense of belonging is not static but dynamic, and it can fluctuate with transitions from class to class, year to year, or situation to situation. For example, a student who feels they belong in your course today may suddenly doubt they belong if they score poorly on an exam tomorrow. Therefore, it is important to continually observe students’ behavior and support their belonging throughout the term.

Sense of belonging affects students’ academic engagement and motivation, as well as their emotional wellbeing. The bottom line is this: Students who feel they belong are more likely to succeed.

For more insight into college students’ sense of belonging, watch this engaging TEDx talk by Ohio State professor Dr. Terrell Strayhorn.

In Practice

You want all students to feel they belong in your course. What concrete strategies can you use to shape a positive learning environment?

Set a positive tone from the start

Simple efforts to establish a welcoming atmosphere in the early days and weeks of class can help students feel more comfortable, included, and confident.

Use positive language in your syllabus . Your syllabus is the first impression students have of your course. Framing policies and expectations in friendly and constructive language, rather than with strong directives or punitive warnings, can increase students’ comfort.

Get to know students and help them get to know each other . On the first day, ask students their preferred names and pronouns and facilitate icebreaker activities to build community. Use Namecoach in CarmenCanvas to have students record the pronunciation of their names and set their pronouns. Surveys and polling, such as through Top Hat , are great ways to informally assess students’ motivations, learning goals, and prior knowledge early in the course.

Be warm, friendly, and present . Greet students when they enter the class, make yourself available before and after class, and set up office hours. Share your enthusiasm about the course and relevant personal experience—this can humanize you and increase students’ connection to the material.

Share positive messages about student success . Show students you believe in their capacity to succeed. Avoid negative statements such as, “Only 1 in 4 of you will pass this class.” Instead, normalize academic struggle and assure students they can master difficult content with effort.

Online Instructor Presence

Strong instructor presence in online courses has been shown to increase participation, facilitate knowledge acquisition, and foster a healthy learning community. When teaching online, you can make meaningful connections to students through video introductions, online office hours, and regular and planned communication. Read more about online instructor presence .

Foster open discourse and communication

Meaningful class discourse requires more than a friendly demeanor. Be prepared to address complex issues, difficult questions, and conflict in collaborative ways.

Develop a classroom agreement . Involve students explicitly in shaping the learning environment. Help them craft a (potentially living) document that outlines community norms and ground rules for respect, civil discourse, and communication.

Resist “right” answers . Encourage discussion that promotes critical thinking rather than simple consensus. Invite students to offer their perspectives before sharing your own, and guide them to consider multiple viewpoints and avenues to solving problems.

Respond to classroom conflict . Consider how you will frame controversial content or “hot topics” in your course. Rather than avoiding these conversations, plan in advance how to facilitate a productive and civil discussion. Refer students back to the ground rules they laid out in the classroom agreement. See Calling in Classroom Conflict for more information.

Get feedback from students . Provide opportunities for students to give frequent anonymous feedback on your course—and show you value their input by acting on it. Surveys or exit slips, in addition to conventional midterm feedback, can bring to light issues that affect students’ sense of belonging or inhibit their learning.

Create an inclusive environment

Embrace multiple perspectives, ways of learning, and modes of expression so all students feel included and supported.

Choose inclusive course content . Do the authors of your course materials represent the spectrum of identities of people in your field? Of students in your class? Who is depicted in the readings and videos you assign? Include course material representing diverse identities, perspectives, and experiences to help all students connect to your content.

Use a variety of teaching methods . Incorporate multiple strategies that appeal to various abilities and preferences: lecture, whole-group and small-group discussion, think-pair-share, in-class writing exercises, case studies, role-playing, games, technology tools, and more. And don’t limit yourself to conventional “texts”—film and video, podcasts, and guest lectures are all engaging ways to present content.

Provide assignment options . Support student success by offering multiple modes to complete assignments. Options range from traditional, such as papers, presentations, and posters, to creative, such as websites, blogs, infographics, games, videos, and podcasts. Allow both individual and group work options, when feasible.

Make space for differing participation . Fear of being called on can hinder students’ comfort and motivation. Encourage, but don’t force, participation during in-class discussions, and acknowledge introverted students when they contribute. Consider alternate ways students can share ideas, such as via written reflections, online discussion posts, and lower-pressure think-pair-shares. Giving students time to reflect on “big questions” before discussion can also increase their confidence to speak up.

Organize your course to support students

The structure and content of your course, in addition to how you deliver it, are key to creating a supportive course climate.

Communicate learning outcomes . Being explicit about what you want students to do—and why it matters—can increase their motivation. Discuss the purpose of your course and its relevance to their lives, tell them what you will cover at the beginning of each class, and share a rationale for all assignments.

Be transparent and efficient with grading . Create student-friendly rubrics that lay out clear expectations for all assignments. Grade and return student work in a timely manner, with actionable feedback that helps them understand their progress and areas for improvement.

Ensure course materials are accessible . When content is accessible , students with vision, auditory, motor, and cognitive disabilities can successfully navigate, use, and benefit from it. Using heading structures in documents, providing alternate text for images, and captioning videos are a few practices that make your course material accessible, as well as more clear and user-friendly for everyone.

Share resources . In addition to extended material on your course subject, link students to helpful resources for mental health, stress, and learning assistance.

Carmen Common Sense

Consult Carmen Common Sense , a student-authored list of ten solutions to a student-friendly course, to learn how to build a supportive learning environment in Carmen.

Icebreaker Activities

Tips for learning student names, addressing offensive comments in class.

Students are more likely to succeed in positive learning environments where they feel a sense of belonging.

There is no singular or perfect learning environment. Every class you teach is a unique community made up of individuals with diverse identities, backgrounds, and experiences. A number of strategies can help you foster a classroom climate that is welcoming, inclusive, and responsive to their needs.

Set a positive tone from the start through your syllabus, community-building activities, a warm demeanor, and constructive messages about student success.

Foster open discourse and communication through classroom agreements, addressing complex issues and conflict productively, and collecting regular feedback from students.

Create an inclusive environment by choosing diverse and representative course material, using a variety of teaching methods, and providing options for assignments and participation.

Organize your course to support students by making your goals, rationale, and expectations for the course and assignments clear, ensuring materials are accessible, and providing resources to support students’ wellbeing.

- Office of Diversity and Inclusion (website)

- Teaching for Racial Justice (website)

- Classroom Climate: Creating a Supportive Learning Environment (website)

- Encouraging a Sense of Belonging (video)

- Namecoach for Instructors (guide)

Learning Opportunities

Ambrose, S. A., & Mayer, R. E. (2010). How learning works: seven research-based principles for smart teaching . Jossey-Bass.

DeSurra, C. J., & Church, K. A. (1994). Unlocking the Classroom Closet Privileging the Marginalized Voices of Gay/Lesbian College Students . Annual Meeting of the Speech Communication Association, New Orleans, LA. Distributed by ERIC. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED379697

Hall, R. (1982). A classroom climate: A chilly one for women?. Association of American Colleges. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED215628

Hall, R., & Sandler, B. (1984). Out of the classroom: A chilly campus climate for women?. Association of American Colleges. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED254125

Hoops, L. D., Green, M., Baker, A., & Hensley, L. C. (2016, February). Success in terms of belonging: An exploration of college student success stories. The Ohio State University Hayes Research Forum, Columbus, OH.

Hurtado, S., Milem, J., Clayton-Pedersen, A., & Allen, W. (1999). Enacting diverse learning environments: Improving the climate for racial/ethnic diversity in higher education. ERIC Clearinghouse on Higher Education in cooperation with Association for the Study of Higher Education. The George Washington University. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED430514

Johnson, D. R., Soldner, M., Leonard, J. B., Alvarez, P., Inkelas, K. K., Rowan-Kenyon, H. T., & Longerbeam, S. D. (2007). Examining Sense of Belonging Among First-Year Undergraduates From Different Racial/Ethnic Groups. Journal of College Student Development , 48 (5), 525–542. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2007.0054

Sandler, B., & Hall, R. (1986). The campus climate revisited: Chilly for women faculty, administrators, and graduate students. Association of American Colleges. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED282462

Strayhorn, T. L. (2008). Sentido de Pertenencia: A hierarchical analysis predicting sense of belonging among Latino college students. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education , 7 (4), 301–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/1538192708320474

Strayhorn, T. L. (2009). Fittin' In: Do Diverse Interactions with Peers Affect Sense of Belonging for Black Men at Predominantly White Institutions? NASPA Journal , 45 (4). https://doi.org/10.2202/0027-6014.2009

Walton, G. M., & Cohen, G. L. (2007). A question of belonging: Race, social fit, and achievement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 92 (1), 82–96. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.1.82

Watson, L. W., Person, D. R., Rudy, D. E., Gold, J. A., Cuyjet, M. J., Bonner, F. A. I., … Terrell, M. C. (2002). How Minority Students Experience College: Implications for Planning and Policy . Stylus Publishing.

Whitt, E. J., Edison, M. I., Pascarella, E. T., Nora, A., & Terenzini, P. T. (1999). Women's perceptions of a "chilly climate" and cognitive outcomes in college: Additional evidence. Journal of College Student Development, 40 (2), 163–177. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ590847

Zumbrunn, S., Mckim, C., Buhs, E., & Hawley, L. R. (2014). Support, belonging, motivation, and engagement in the college classroom: a mixed method study. Instructional Science , 42 (5), 661–684. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-014-9310-0

Related Teaching Topics

Creating an inclusive environment in carmenzoom, supporting student learning and metacognition, search for resources.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Appendix 1: Building an effective learning environment

A.2 What is a learning environment?

A.2.1 definition.

‘Learning environment refers to the diverse physical locations, contexts, and cultures in which students learn. Since students may learn in a wide variety of settings, such as outside-of-school locations and outdoor environments, the term is often used as a more accurate or preferred alternative to classroom, which has more limited and traditional connotations—a room with rows of desks and a chalkboard, for example. The term also encompasses the culture of a school or class—its presiding ethos and characteristics, including how individuals interact with and treat one another—as well as the ways in which teachers may organize an educational setting to facilitate learning…..’

The Glossary of Educational Reform , 29 August, 2014

This definition recognises that students learn in many different ways in very different contexts. Since learners must do the learning, the aim is to create a total environment for learning that optimises the ability of students to learn. There is of course no single optimum learning environment. There is an infinite number of possible learning environments, which is what makes teaching so interesting.

A.2.2 Components of an effective learning environment

Developing a total learning environment for students in a particular course or program is probably the most creative part of teaching. While there is a tendency to focus on either physical institutional learning environments (such as classrooms, lecture theatres and labs), or on the technologies used to to create online personal learning environments (PLEs), learning environments are broader than just these physical components. They will also include:

- the characteristics of the learners;

- the goals for teaching and learning;

- the activities that will best support learning;

- the assessment strategies that will best measure and drive learning

- the culture that infuses the learning environment.

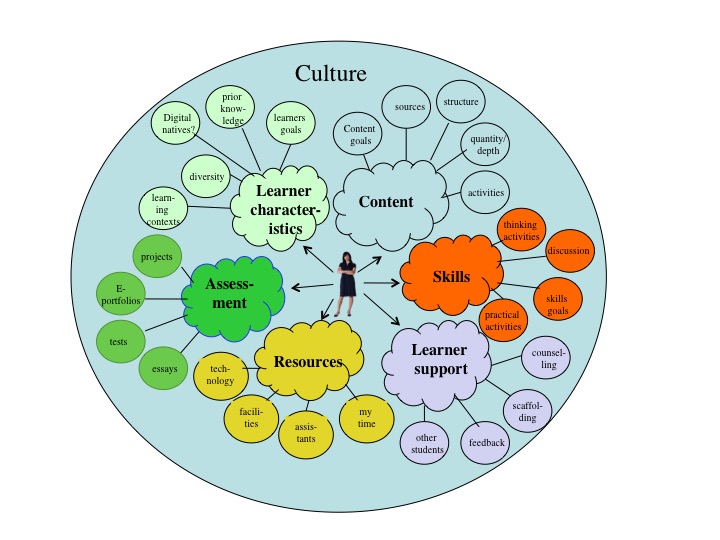

Figure A.2.2 illustrates one possible learning environment from the perspective of a teacher or instructor. A teacher may have little or no control over some components, such as learner characteristics or resources, but may have full control over other components such as choice of content and how learners will be supported. Within each of the main components there are a set of sub-components that will need to be considered. In fact, it is in the sub-components (content structure, practical activities, feedback, use of technology, assessment methods, and so on) where the real decisions need to be made.

I have listed just a few components in Figure A.2.2 and the set is not meant to be comprehensive. For instance it could have included other components, such as developing ethical behaviour, institutional factors, or external accreditation, each of which might also affect the learning environment in which a teacher or instructor has to work. Creating a model of a learning environment then is a heuristic device that aims to provide a comprehensive view of the whole teaching context for a particular course or program, by a particular instructor or teacher with a particular view of learning. Once again, the choice of components and their perceived importance will be driven to some extent by personal epistemologies and beliefs about knowledge, learning and teaching methods.

Lastly, I have deliberately suggested a learning environment from the perspective of a teacher, as the teacher has the main responsibility for creating an appropriate learning environment, but it is also important to consider learning environments from the learners’ perspectives. Indeed, adult or mature learners are capable of creating their own, personal, relatively autonomous learning environments.

The significant point is that it is important to identify those components that need to be considered in teaching a course or program, and in particular that there are other components besides content or curriculum. Each of the key components of the learning environment I have chosen as an example are discussed briefly in the following sections, with a focus on the components of a learning environment that are particularly relevant for a digital age.

Activity A.2 Influencing a learning environment

- Why do you think I focused on learning environments from a teacher’s perspective rather than a learner’s perspective?

- In order to create the learning environment for HIST 305 in Scenario E, Ralph Goodyear carefully considered the learning environment he wanted to create and ones he had little or no control over. What components do you think he had little or no control over?

- What would you add (or remove) from the learning environment in Figure A.2.2?

- Figure A.2.2 focuses on a learning environment from a teacher’ perspective. Could you design a similar model of a learning environment from the perspective of a learner? What would be the main differences?

- Does thinking about the whole learning environment overly complicate the teaching endeavour? Why not just get on with it?

Teaching in a Digital Age Copyright © 2015 by Anthony William (Tony) Bates is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Created by the Great Schools Partnership , the GLOSSARY OF EDUCATION REFORM is a comprehensive online resource that describes widely used school-improvement terms, concepts, and strategies for journalists, parents, and community members. | Learn more »

Learning Environment

Learning environment refers to the diverse physical locations, contexts, and cultures in which students learn. Since students may learn in a wide variety of settings, such as outside-of-school locations and outdoor environments, the term is often used as a more accurate or preferred alternative to classroom , which has more limited and traditional connotations—a room with rows of desks and a chalkboard, for example.