Ten Important Questions About Child Poverty and Family Economic Hardship

- Publication Type Report

- Post date December, 2009

Download PDF

What is the Nature of Poverty and Economic Hardship in the United States?

- What does it mean to experience poverty?

- How is poverty measured in the United States?

- Are Americans who experience poverty now better off than a generation ago?

- How accurate are commonly held stereotypes about poverty and economic hardship?

How Serious is the Problem of Economic Hardship for American Families?

- How many children in the U.S. live in families with low incomes?

- Are some children and families at greater risk for economic hardship than others?

- What are the effects of economic hardship on children?

Is it Possible to Reduce Economic Hardship among American Families?

- Why is there so much economic hardship in a country as wealthy as the U.S.?

- Why should Americans care about family economic hardship?

- What can be done to increase economic security for America’s children and families?

1. What does it mean to experience poverty?

Families and their children experience poverty when they are unable to achieve a minimum, decent standard of living that allows them to participate fully in mainstream society. One component of poverty is material hardship. Although we are all taught that the essentials are food, clothing, and shelter, the reality is that the definition of basic material necessities varies by time and place. In the United States, we all agree that having access to running water, electricity, indoor plumbing, and telephone service are essential to 21st century living even though that would not have been true 50 or 100 years ago.

To achieve a minimum but decent standard of living, families need more than material resources; they also need “human and social capital.” Human and social capital include education, basic life skills, and employment experience, as well as less tangible resources such as social networks and access to civic institutions. These non-material resources provide families with the means to get by, and ultimately, to get ahead. Human and social capital help families improve their earnings potential and accumulate assets, gain access to safe neighborhoods and high-quality services (such as medical care, schooling), and expand their networks and social connections.

The experiences of children and families who face economic hardship are far from uniform. Some families experience hard times for brief spells while a small minority experience chronic poverty. For some, the greatest challenge is inadequate financial resources, whether insufficient income to meet daily expenses or the necessary assets (savings, a home) to get ahead. For others, economic hardship is compounded by social isolation. These differences in the severity and depth of poverty matter, especially when it comes to the effects on children.

2. How is poverty measured in the United States?

The U.S. government measures poverty by a narrow income standard — this measure does not include material hardship (such as living in substandard housing) or debt, nor does it consider financial assets (such as savings or property). Developed more than 40 years ago, the official poverty measure is a specific dollar amount that varies by family size but is the same across the continental U.S..

According to the federal poverty guidelines, the poverty level is $22,050 for a family of four and $18,310 for a family of three (see table). (The poverty guidelines are used to determine eligibility for public programs. A similar but more complicated measure is used for calculating poverty rates.)

The current poverty measure was established in the 1960s and is now widely acknowledged to be outdated. It was based on research indicating that families spent about one-third of their incomes on food — the official poverty level was set by multiplying food costs by three. Since then, the same figures have been updated annually for inflation but have otherwise remained unchanged.

Yet food now comprises only one-seventh of an average family’s expenses, while the costs of housing, child care, health care, and transportation have grown disproportionately. Most analysts agree that today’s poverty thresholds are too low. And although there is no consensus about what constitutes a minimum but decent standard of living in the U.S., research consistently shows that, on average, families need an income of about twice the federal poverty level to meet their most basic needs.

Failure to update the federal poverty level for changes in the cost of living means that people who are considered poor today by the official standard are worse off relative to everyone else than people considered poor when the poverty measure was established. The current federal poverty measure equals about 31 percent of median household income, whereas in the 1960s, the poverty level was nearly 50 percent of the median.

The European Union and most advanced industrialized countries measure poverty quite differently from the U.S. Rather than setting minimum income thresholds below which individuals and families are considered to be poor, other countries measure economic disadvantage relative to the citizenry as a whole, for example, having income below 50 percent of median.

3. Are Americans who experience poverty now better off than a generation ago?

Material deprivation is not as widespread in the United States as it was 30 or 40 years ago. For example, few Americans experience severe or chronic hunger, due in large part to public food and nutrition programs, such as food stamps, school breakfast and lunch programs, and WIC (the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children). Over time, Social Security greatly reduced poverty and economic insecurity among the elderly. Increased wealth and technological advances have made it possible for ordinary families to have larger houses, computers, televisions, multiple cars, stereo equipment, air conditioning, and cell phones.

Some people question whether a family that has air conditioning or a DVD player should be considered poor. But in a wealthy nation such as the US, cars, computers, TVs, and other technologies are considered by most to be a normal part of mainstream American life rather than luxuries. Most workers need a car to get to work. TVs and other forms of entertainment link people to mainstream culture. And having a computer with access to the internet is crucial for children to keep up with their peers in school. Even air conditioning does more than provide comfort — in hot weather, it increases children’s concentration in school and improves the health of children, the elderly, and the chronically ill.

Consider as well the devastating effects of Hurricane Katrina. Prior to the hurricane, New Orleans had one of the highest child poverty rates in the country — 38 percent (and this figure would be much higher if it included families with incomes up to twice the official poverty level). One in five households in New Orleans lacked a car, and eight percent had no phone service. The pervasive social and economic isolation increased the loss of life from the hurricane and exacerbated the devastating effects on displaced families and children.

Focusing solely on the material possessions a family has ignores the other types of resources they need to provide a decent life for their children — a home in a safe neighborhood; access to good schools, good jobs and basic services; and less tangible resources such as basic life skills and support networks.

4. How accurate are commonly held stereotypes about poverty?

The most commonly held stereotypes about poverty are false. Family poverty in the U.S. is typically depicted as a static, entrenched condition, characterized by large numbers of children, chronic unemployment, drugs, violence, and family turmoil. But the realities of poverty and economic hardship are very different.

Americans often talk about “poor people” as if they are a distinct group with uniform characteristics and somehow unlike the rest of “us.” In fact, there is great diversity among children and families who experience economic hardship. Research shows that many stereotypes just aren’t accurate: a study of children born between 1970 and 1990 showed that 35 percent experienced poverty at some point during their childhood; only a small minority experienced persistent and chronic poverty. And more than 90 percent of low-income single mothers have only one, two, or three children.

Although most portrayals of poverty in the media and elsewhere reflect the experience of only a few, a significant portion of families in America have experienced economic hardship, even if it is not life-long. Americans need new ways of thinking about poverty that allow us to understand the full range of economic hardship and insecurity in our country. In addition to the millions of families who struggle to make ends meet, millions of others are merely one crisis — a job loss, health emergency, or divorce — away from financial devastation, particularly in this fragile economy. A recent study showed that the majority of American families with children have very little savings to rely on during times of crisis. Recently, more and more families have become vulnerable to economic hardship.

5. How many children in the US live in families with low incomes?

Given that official poverty statistics are deeply flawed, the National Center for Children in Poverty uses “low income” as one measure of economic hardship. Low income is defined as having income below twice the federal poverty level — the amount of income that research suggests is needed on average for families to meet their basic needs. About 41 percent of the nation’s children — nearly 30 million in 2008 — live in families with low incomes, that is, incomes below twice the official poverty level (for 2009, about $44,000 for a family of four).

Although families with incomes between 100 and 200 percent of the poverty level are not officially classified as poor, many face material hardships and financial pressures similar to families with incomes below the poverty level. Missed rent payments, utility shut offs, inadequate access to health care, unstable child care arrangements, and running out of food are not uncommon for such families.

Low-income rates for young children are higher than those for older children — 44 percent of children under age six live in low-income families, compared to 39 percent of children over age six. Parents of younger children tend to be younger and to have less education and work experience than parents of older children, so their earnings are typically lower.

6. Are some children and families at greater risk for economic hardship than others?

Low levels of parental education are a primary risk factor for being low income. Eighty-three percent of children whose parents have less than a high school diploma live in low-income families, and over half of children whose parents have only a high school degree are low income as well. Workers with only a high school degree have seen their wages stagnate or decline in recent decades while the income gap between those who have a college degree and those who do not has doubled. Yet only 27 percent of workers in the U.S. have a college degree.

Single-parent families are at greater risk of economic hardship than two-parent families, largely because the latter have twice the earnings potential. But research indicates that marriage does not guarantee protection from economic insecurity. More than one in four children with married parents lives in a low-income family. In rural and suburban areas, the majority of low-income children have married parents. And among Latinos, more than half of children with married parents are low income. Moreover, most individuals who experience poverty as adults grew up in married-parent households.

Although low-income rates for minority children are considerably higher than those for white children, this is due largely to a higher prevalence of other risk factors, for example, higher rates of single parenthood and lower levels of parental education and earnings. About 61 percent of black, 62 percent of Latino children and 57 percent of American Indian children live in low-income families, compared to about 27 percent of white children and 31 percent of Asian children. At the same time, however, whites comprise the largest group of low-income children: 11 million white children live in families with incomes below twice the federal poverty line.

Having immigrant parents also increases a child’s chances of living in a low-income family. More than 20 percent of this country’s children — about 16 million — have at least one foreign-born parent. Sixty percent of children whose parents are immigrants are low-income, compared to 37 percent of children whose parents were born in the U.S.

7. What are the effects of economic hardship on children?

Economic hardship and other types of deprivation can have profound effects on children’s development and their prospects for the future — and therefore on the nation as a whole. Low family income can impede children’s cognitive development and their ability to learn. It can contribute to behavioral, social, and emotional problems. And it can cause and exacerbate poor child health as well. The children at greatest risk are those who experience economic hardship when they are young and children who experience severe and chronic hardship.

It is not simply the amount of income that matters for children. The instability and unpredictability of low-wage work can lead to fluctuating family incomes. Children whose families are in volatile or deteriorating financial circumstances are more likely to experience negative effects than children whose families are in stable economic situations.

The negative effects on young children living in low income families are troubling in their own right. These effects are also cause for concern because they are associated with difficulties later in life — dropping out of school, poor adolescent and adult health, poor employment outcomes and experiencing poverty as adults. Stable, nurturing, and enriching environments in the early years help create a sturdy foundation for later school achievement, economic productivity, and responsible citizenship.

Parents need financial resources as well as human and social capital (basic life skills, education, social networks) to provide the experiences, resources, and services that are essential for children to thrive and to grow into healthy, productive adults — high-quality health care, adequate housing, stimulating early learning programs, good schools, money for books, and other enriching activities. Parents who face chronic economic hardship are much more likely than their more affluent peers to experience severe stress and depression — both of which are linked to poor social and emotional outcomes for children.

Is it Possible to Reduce Economic Hardship for American Families?

8. why is there so much economic hardship in a country as wealthy as the u.s..

Given its wealth, the U.S. had unusually high rates of child poverty and income inequality, even prior to the current economic downturn. These conditions are not inevitable — they are a function both of the economy and government policy. In the late 1990s, for example, there was a dramatic decline in low-income rates, especially among the least well off families. The economy was strong and federal policy supports for low-wage workers with children — the Earned Income Tax Credit, public health insurance for children, and child care subsidies — were greatly expanded. In the current economic downturn, it is expected that the number of poor children will increase by millions.

Other industrialized nations have lower poverty rates because they seek to prevent hardship by providing assistance to all families. These supports include “child allowances” (typically cash supplements), child care assistance, health coverage, paid family leave, and other supports that help offset the cost of raising children.

But the U.S. takes a different policy approach. Our nation does little to assist low-income working families unless they hit rock bottom. And then, such families are eligible only for means-tested benefits that tend to be highly stigmatized; most families who need help receive little or none. (One notable exception is the federal Earned Income Tax Credit.)

At the same time, middle- and especially upper-income families receive numerous government benefits that help them maintain and improve their standard of living — benefits that are largely unavailable to lower-income families. These include tax-subsidized benefits provided by employers (such as health insurance and retirement accounts), tax breaks for home owners (such as deductions for mortgage interest and tax exclusions for profits from home sales), and other tax preferences that privilege assets over income. Although most people don’t think of these tax breaks as government “benefits,” they cost the federal treasury nearly three times as much as benefits that go to low- to moderate-income families. In addition, middle- and upper-income families reap the majority of benefits from the child tax credit and the child care and dependent tax credit because neither is fully refundable.

In short, high rates of child poverty and income inequality in the U.S. can be reduced, but effective, widespread, and long-lasting change will require shifts in both national policy and the economy.

9. Why should Americans care about family economic hardship?

In addition to the harmful consequences for children, high rates of economic hardship exact a serious toll on the U.S. economy. Economists estimate that child poverty costs the U.S. $500 billion a year in lost productivity in the labor force and spending on health care and the criminal justice system. Each year, child poverty reduces productivity and economic output by about 1.3 percent of GDP.

The experience of severe or chronic economic hardship limits children’s potential and hinders our nation’s ability to compete in the global economy. American students, on average, rank behind students in other industrialized nations, particularly in their understanding of math and science. Analysts warn that America’s ability to compete globally will be severely hindered if many of our children are not as academically prepared as their peers in other nations.

Long-term economic trends are also troubling as they reflect the gradual but steady growth of economic insecurity among middle-income and working families over the last 30 years. Incomes have increased very modestly for all but the highest earners. Stagnant incomes combined with the high cost of basic necessities have made it difficult for families to save, and many middle- and low-income families alike have taken on crippling amounts of debt just to get by.

Research also indicates that economic inequality in America has been on the rise since the 1970s. Income inequality has reached historic levels — the income share of the top one percent of earners is at its highest level since 1929. Between 1979 and 2006, real after-tax incomes rose by 256 percent for the top one percent of households, compared to 21 percent and 11 percent for households in the middle and bottom fifth (respectively).

Economic mobility—the likelihood of moving from one income group to another—is on the decline in the U.S. Although Americans like to believe that opportunity is equally available to all, some groups find it harder to get ahead than others. Striving African American families have found upward mobility especially difficult to achieve and are far more vulnerable than whites to downward mobility. The wealth gap between blacks and whites — black families have been found to have one-tenth the net worth of white families — is largely responsible.

What all of these trends reveal is that the American Dream is increasingly out of reach for many families. The promise that hard work and determination will be rewarded has become an increasingly empty promise in 21st century America. It is in the best interest of our nation to see that the American Dream, an ideal so fundamental to our collective identity, be restored.

10. What can be done to increase economic security for America’s children and families?

A considerable amount of research has been devoted to this question. We know what families need to succeed economically, what parents need to care for and nurture their children, and what children need to develop into healthy, productive adults. The challenge is to translate this research knowledge into workable policy solutions that are appropriate for the US.

For families to succeed economically, we need an economy that works for all — one that provides workers with sufficient earnings to provide for a family. Specific policy strategies include strengthening the bargaining power of workers, expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit, and increasing the minimum wage and indexing it to inflation. We also need to help workers get the training and education they need to succeed in a changing workforce. Dealing with low wages is necessary but not sufficient. Low- and middle-income families alike need relief from the high costs of health insurance and housing. Further programs that promote asset building among low-income families with children are also important.

As a nation, we also need to make it possible for adults to be both good workers and good parents, which requires greater workplace flexibility and paid time off. Workers need paid sick time, and parents need time off to tend to a sick child or talk to a child’s teacher. Currently, three in four low-wage workers have no paid sick days.

Despite the fact that a child’s earliest years have a profound effect on his or her life trajectory and ultimate ability to succeed, the U.S. remains one of the only industrialized countries that does not provide paid family leave for parents with a new baby. Likewise, child care is largely private in the U.S. — individual parents are left to find individual solutions to a problem faced by all working parents. Low- and middle-income families need more help paying for child care and more assistance in identifying reliable, nurturing care for their children, especially infants and toddlers.

These are only some of the policies needed to reduce economic hardship, strengthen families, and provide a brighter future for today’s — and tomorrow’s — children. With the right leadership, a strong national commitment, and good policy, it’s all possible.

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

It may be neither higher nor intelligence

Bolsonaro, Trump election cases share similarities, but not rulings

Dark concerns over upcoming vote in world’s largest democracy

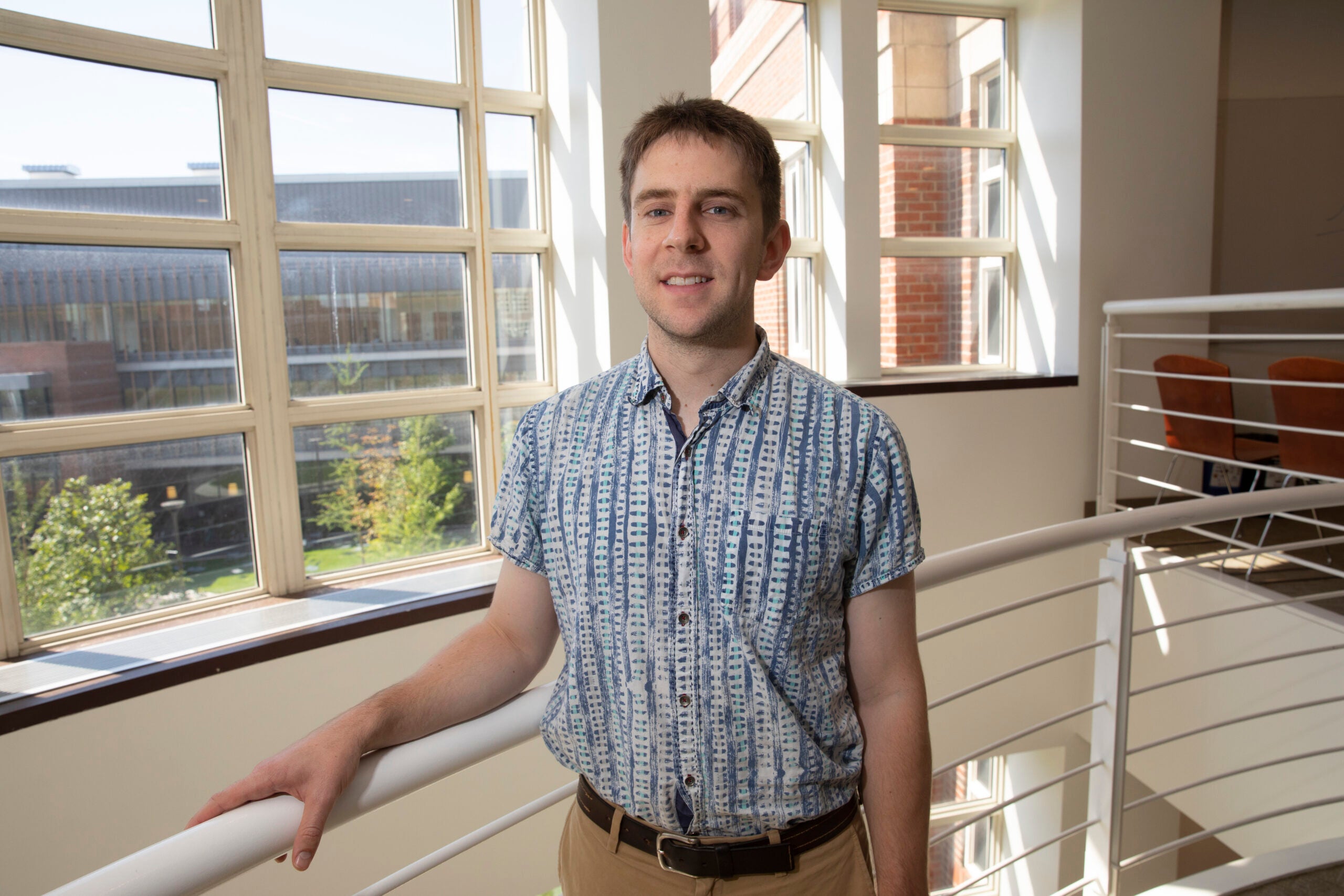

Robert Sampson, Henry Ford II Professor of the Social Sciences, is one of the researchers studying the link between poverty and social mobility.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard file photo

Unpacking the power of poverty

Peter Reuell

Harvard Staff Writer

Study picks out key indicators like lead exposure, violence, and incarceration that impact children’s later success

Social scientists have long understood that a child’s environment — in particular growing up in poverty — can have long-lasting effects on their success later in life. What’s less well understood is exactly how.

A new Harvard study is beginning to pry open that black box.

Conducted by Robert Sampson, the Henry Ford II Professor of the Social Sciences, and Robert Manduca, a doctoral student in sociology and social policy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, the study points to a handful of key indicators, including exposure to high levels of lead, violence, and incarceration as key predictors of children’s later success. The study is described in an April paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“What this paper is trying to do, in a sense, is move beyond the traditional neighborhood indicators people use, like poverty,” Sampson said. “For decades, people have shown poverty to be important … but it doesn’t necessarily tell us what the mechanisms are, and how growing up in poor neighborhoods affects children’s outcomes.”

To explore potential pathways, Manduca and Sampson turned to the income tax records of parents and approximately 230,000 children who lived in Chicago in the 1980s and 1990s, compiled by Harvard’s Opportunity Atlas project. They integrated these records with survey data collected by the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods, measures of violence and incarceration, census indicators, and blood-lead levels for the city’s neighborhoods in the 1990s.

They found that the greater the extent to which poor black male children were exposed to harsh environments, the higher their chances of being incarcerated in adulthood and the lower their adult incomes, measured in their 30s. A similar income pattern also emerged for whites.

Among both black and white girls, the data showed that increased exposure to harsh environments predicted higher rates of teen pregnancy.

Despite the similarity of results along racial lines, Chicago’s segregation means that far more black children were exposed to harsh environments — in terms of toxicity, violence, and incarceration — harmful to their mental and physical health.

“The least-exposed majority-black neighborhoods still had levels of harshness and toxicity greater than the most-exposed majority-white neighborhoods, which plausibly accounts for a substantial portion of the racial disparities in outcomes,” Manduca said.

“It’s really about trying to understand some of the earlier findings, the lived experience of growing up in a poor and racially segregated environment, and how that gets into the minds and bodies of children.” Robert Sampson

“What this paper shows … is the independent predictive power of harsh environments on top of standard variables,” Sampson said. “It’s really about trying to understand some of the earlier findings, the lived experience of growing up in a poor and racially segregated environment, and how that gets into the minds and bodies of children.”

More like this

Cities’ wealth gap is growing, too

Racial and economic disparities intertwined, study finds

The study isn’t solely focused on the mechanisms of how poverty impacts children; it also challenges traditional notions of what remedies might be available.

“This has [various] policy implications,” Sampson said. “Because when you talk about the effects of poverty, that leads to a particular kind of thinking, which has to do with blocked opportunities and the lack of resources in a neighborhood.

“That doesn’t mean resources are unimportant,” he continued, “but what this study suggests is that environmental policy and criminal justice reform can be thought of as social mobility policy. I think that’s provocative, because that’s different than saying it’s just about poverty itself and childhood education and human capital investment, which has traditionally been the conversation.”

The study did suggest that some factors — like community cohesion, social ties, and friendship networks — could act as bulwarks against harsh environments. Many researchers, including Sampson himself, have shown that community cohesion and local organizations can help reduce violence. But Sampson said their ability to do so is limited.

“One of the positive ways to interpret this is that violence is falling in society,” he said. “Research has shown that community organizations are responsible for a good chunk of the drop. But when it comes to what’s affecting the kids themselves, it’s the homicide that happens on the corner, it’s the lead in their environment, it’s the incarceration of their parents that’s having the more proximate, direct influence.”

Going forward, Sampson said he hopes the study will spur similar research in other cities and expand to include other environmental contamination, including so-called brownfield sites.

Ultimately, Sampson said he hopes the study can reveal the myriad ways in which poverty shapes not only the resources that are available for children, but the very world in which they find themselves growing up.

“Poverty is sort of a catchall term,” he said. “The idea here is to peel things back and ask, What does it mean to grow up in a poor white neighborhood? What does it mean to grow up in a poor black neighborhood? What do kids actually experience?

“What it means for a black child on the south side of Chicago is much higher rates of exposure to violence and lead and incarceration, and this has intergenerational consequences,” he continued. “This is particularly important because it provides a way to think about potentially intervening in the intergenerational reproduction of inequality. We don’t typically think about criminal justice reform or environmental policy as social mobility policy. But maybe we should.”

This research was supported with funding from the Project on Race, Class & Cumulative Adversity at Harvard University, the Ford Foundation, and the Hutchins Family Foundation.

Share this article

You might like.

Religious scholars examine value, limits of AI

Former Brazilian judge, legal scholar says deciding who can be blocked from running is perilous, fraught

Social scientists discuss controversial Indian prime minister Modi, rise of right-wing populism, erosion of political journalism

So what exactly makes Taylor Swift so great?

Experts weigh in on pop superstar's cultural and financial impact as her tours and albums continue to break records.

The 20-minute workout

Pressed for time? You still have plenty of options.

Finding right mix on campus speech policies

Legal, political scholars discuss balancing personal safety, constitutional rights, academic freedom amid roiling protests, cultural shifts

Research Areas

- Poverty & Inequality

- Federal & State Education Policy

- Teaching & Leadership Effectiveness

- Technological Innovations in Education

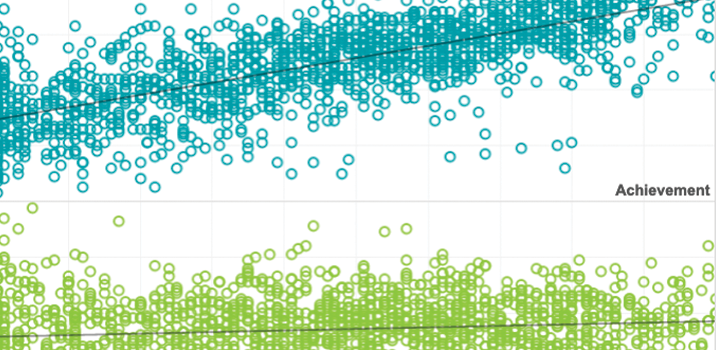

- Poverty and Inequality

Research has shown that inequality still features prominently in the US educational system and that racial and socioeconomic achievement gaps have significant long-term effects for disadvantaged students. Reducing educational inequality is a priority for educators, administrators, and policymakers. CEPA provides empirical research that explores a variety of issues relating to poverty and inequality in education. Topics of focus include the effects that income disparity, race, gender, family backgrounds, and other factors can have on educational outcomes as well as the causes, patterns, and effects of poverty and inequality.

Kaylee T. Matheny

Marissa E. Thompson

Carrie Townley-Flores

sean f. reardon

Mark Murphy

Angela Johnson

Sean F. Reardon

Ericka Weathers

Heewon Jang

Demetra Kalogrides

Eric P. Bettinger

Gregory S. Kienzl

Josh Leung-Gagne

Jessica Drescher

Anne Podolsky

Gabrielle Torrance

Francis A. Pearman, II

Danielle Marie Greene

Sade Bonilla

Thomas S. Dee

Emily K. Penner

Dominique J. Baker

Bethany Edwards

Spencer F. X. Lambert

Grace Randall

Emily Morton

Tolani Britton

Eleonora Bertoni

Gregory Elacqua

Luana Marotta

Matías Martinez

Humberto Santos

Sammara Soares

Jaymes Pyne

Erica Messner

Elise Dizon-Ross

Qiang Zheng

Prashant Loyalka

Sean Sylvia

Yaojiang Shi

Sarah-Eve Dill

Scott Rozelle

Benjamin R. Shear

Francis A. Pearman

John P. Papay

Tara Kilbride

Katharine O. Strunk

Joshua Cowen

Kate Donohue

F. Chris Curran

Benjamin W. Fisher

Joseph H. Gardella

Emily Penner

You are here

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

100 Questions: identifying research priorities for poverty prevention and reduction

Reducing poverty is important for those affected, for society and the economy. Poverty remains entrenched in the UK, despite considerable research efforts to understand its causes and possible solutions. The Joseph Rowntree Foundation, with the Centre for Science and Policy at the University of Cambridge, ran a democratic, transparent, consensual exercise involving 45 participants from government, non-governmental organisations, academia and research to identify 100 important research questions that, if answered, would help to reduce or prevent poverty. The list includes questions across a number of important themes, including attitudes, education, family, employment, heath, wellbeing, inclusion, markets, housing, taxes, inequality and power.

Related Papers

Policy & Politics

Justin Keen

Richard J White

This article explores the ways in which young people's decisions about post-compulsory education, training and employment are shaped by place, drawing on case study evidence from three deprived neighbourhoods in England. It discusses the way in which place-based social networks and attachment to place influence individuals' outlooks and how they interpret and act on the opportunities they see. While such networks and place attachment can be a source of strength in facilitating access to opportunities, they can also be a source of weakness in acting to constrain individuals to familiar choices and locations. In this way, 'subjective' geographies of opportunity may be much more limited than 'objective' geographies of opportunity. Hence it is important for policy to recognise the importance of 'bounded horizons'.

Michael Hirst , Anne Corden

Lisa Scullion

J. Poverty Soc. Justice

Toity Deave

Journal of Poverty and Social Justice

Kirsten Besemer

Stephen Sinclair , John McKendrick

Social Policy and Society

Line Nyhagen

John Hills , David Piachaud

The Joseph Rowntree Foundation has supported this project as part of its programme of research and innovative development projects, which it hopes will be of value to policy makers, practitioners and service users. The facts presented and views expressed in this report are, however, ...

CASE Papers

Ruth Lister

RELATED PAPERS

Jonathan Bradshaw

Ronald McQuaid

Colin Lindsay

Journal of Policy Analysis and Management

Liam Foster

Alison Garnham

Mark Tomlinson

Cambridge Journal of Economics

Kevin Albertson , Paul Stepney

Serena Romano

Mansel Aylward

Surya Monro

Alex Nunn , Ronald McQuaid , Tim Bickerstaffe

… by National Association of Welfare Rights …

Colin Talbot

GA Williams , Mark Tomlinson

Hilary Stevens

Chris Pittman

Ian Cummins

Information, communication & …

Abigail Davis

… , communication & society

Bryony Beresford

Martin Taulbut

research.dwp.gov.uk

Peter Allmark

Richard Riddell

Glen Bramley

Judy Corlyon

Ronald McQuaid , Vanesa Fuertes

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health

Shoshana Pollack

alan france

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Center for School and Student Progress

Media mention

Exploring the relationship between poverty and school performance

September 2019

Education Dive

Description

In this interview, Andrew Hegedus shares the origins of his work exploring the relationship between poverty and school performance, implications for educators, and where his research is headed next.

Topics: Equity , High-growth schools & practices

Associated Research

Blog article

Presentation

White paper

Related Topics

High dosage tutoring for academically at-risk students

This brief provides a review of the research on high dosage tutoring as an intervention strategy for supporting at-risk students. It highlights the benefits and the non-negotiable factors for effective implementation and usage.

By: Ayesha K. Hashim , Miles Davison , Sofia Postell , Jazmin Isaacs

Topics: COVID-19 & schools , Equity , Growth , Informing instruction

Typical learning for whom? Guidelines for selecting benchmarks to calculate months of learning

To describe the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on students, researchers have translated test scores into months of learning to claim how many months/years students are behind in school. Despite its perceived accessibility, there are major downsides to this translation. To inform future uses by researchers and media, we discuss in this brief how to calculate this metric as well as its trade-offs.

By: Megan Kuhfeld , Melissa Diliberti , Andrew McEachin , Jon Schweig , Louis T. Mariano

Topics: COVID-19 & schools , Equity , Growth , Growth modeling , Seasonal learning patterns & summer loss

Education’s long COVID: 2022–23 achievement data reveal stalled progress toward pandemic recovery

New research shows progress toward academic recovery stalled in 2022-23. This research brief covers data from 6.7 million US students examining academic gains relative to pre-pandemic years as well as tracking the gap in achievement between COVID year student groups compared to their pre-pandemic peers.

By: Karyn Lewis , Megan Kuhfeld

Products: MAP Growth

Topics: COVID-19 & schools , Equity

Technical appendix: 2022-23 achievement data reveal stalled progress toward pandemic recovery

The purpose of this technical appendix is to share more detailed results and describe the sample and methods used in the research in Education’s long COVID: 2022-23 achievement data reveal stalled progress toward pandemic recovery report.

By: Jazmin Isaacs , Megan Kuhfeld , Karyn Lewis

Technical appendix for progress towards pandemic recovery continued signs of rebounding achievement at the start of the 2022-2023 school year

The purpose of this technical appendix is to share more detailed results and describe the sample and methods used in the research in Progress towards pandemic recovery: Continued signs of rebounding achievement at the start of the 2022-23 school year.

By: Megan Kuhfeld , Karyn Lewis

Progress towards pandemic recovery: Continued signs of rebounding achievement at the start of the 2022-23 school year

New research provides evidence that student reading and math achievement at the start of the 2022–23 school year is continuing to rebound from the impacts of the pandemic, though full recovery is likely still several years away.

Topics: Equity , COVID-19 & schools

Technical appendix for: The widening achievement divide during COVID-19

The purpose of this technical appendix is to share more detailed results and to describe more fully the sample and methods used in the research included in the brief, The widening achievement divide during COVID-19.

By: Megan Kuhfeld , Meredith Langi , Karyn Lewis

Popular Topics

Data Visualizations

View interactive tools that bring complex education issues to life. Explore patterns in growth, achievement, poverty, college readiness, and more.

Research Partnerships

Our collaborations with university researchers, school systems, address diverse education research topics.

Upcoming Research Presentations

Connect with us and learn about our newest research at these conferences and events.

Media Contact

Simona Beattie Sr. Manager, Public Relations

971.361.9526

Stay current by subscribing to our newsletter

STAY CURRENT

You are now signed up to receive our newsletter containing the latest news, blogs, and resources from nwea., thank you for registering to be a partner in research.

Close Overlay

Download the guide

Click below to view now..

Continue exploring >>

Advertisement

Poverty, place and pedagogy in education: research stories from front-line workers

- Published: 10 August 2016

- Volume 43 , pages 393–417, ( 2016 )

Cite this article

- Barbara Comber ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8364-1676 1 , 2

17k Accesses

19 Citations

16 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This article considers what it means to teach and learn in places of poverty through the narratives of front-line workers—particularly students and teachers. What is the work of teaching and learning in places of poverty in current times? How has this changed? What can be learned from both the haunting and hopeful narratives of front-line workers? Is it possible to continue to educate in these times and in ways that allow for critique, imagination and optimism? These questions are addressed by drawing from studies conducted over three decades in schools located in high-poverty neighbourhoods. Literacy education is considered as a particular case. Educational researchers need to remain on the front line with teachers and students in places of poverty because that is where some of the hardest work gets done. Reinvigorated democratic research communities would include teachers, school leaders, policy workers and young people.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

The project is entitled ‘Literacy and the imagination: Working with place and space as resources for children’s learning’ and in South Australia was undertaken by Barbara Comber, Helen Grant, Lyn Kerkham, Ruth Trimboli and Marg Wells. Annette Woods worked with a teacher-researcher in Brisbane.

Educational leadership and turnaround literacy pedagogies, an Australian Research Council (ARC) Linkage Project (No. LP120100714) between the University of South Australia and the South Australian Department for Education and Child Development (DECD). The project was under taken between 2012 and 2015. The chief investigators were Robert Hattam (University of South Australia), Barbara Comber (Queensland University of Technology), and Deb Hayes (University of Sydney). The research associate was Lyn Kerkham (University of South Australia).

Thanks to Deb Hayes for pointing out to me this connection which emerged through her research. Craig Campbell and Deb Hayes (University of Sydney) are writing a biography of Jean Blackburn (1919–2001), a significant contributor to educational policy, including the SA and national Karmel reports. She was an Australian Schools Commissioner from 1974 to 1980, and key architect of the Disadvantaged Schools Program.

I observed in this school over a period of 2 years, alongside my colleague, Lyn Kerkham. I thank her for sharing her fieldnotes and excerpts of the related video recorded transcript.

ABS. (2013). Census of population and housing: Socio-economic indexes for areas (SEIFA), Australia, 2011 . Australian Bureau of Statistics. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/Lookup/2033.0.55.001main+features100052011 . Accessed 27 July 2016.

Baker, B. (2009). Educational research and strategies of world-forming: The globe, the unconscious, and the child. The Australian Educational Researcher, 36 (3), 1–39.

Article Google Scholar

Ball, S., Maguire, M., & Braun, A. (2012). How schools do policy: Policy enactments in secondary schools . Abingdon: Routledge.

Google Scholar

Bomer, R., Dworin, J. E., May, L., & Semingson, P. (2008). Miseducating teachers about the poor: A critical analysis of Ruby Payne’s claims about poverty. Teachers College Record, 110 (12), 2497–2531.

Burwell, C., & Lenters, K. (2015). Word on the street: Investigating linguistic landscapes with urban Canadian youth. Pedagogies: An International Journal, 10 (3), 201–221.

Cochran-Smith, M., & Lytle, S. (2009). Inquiry as stance: Practitioner research for the next generation . New York: Teachers College Press.

Comber, B. (1998). Problematising ‘background’: (Re)constructing categories in educational research. The Australian Educational Researcher, 25 (3), 1–21.

Comber, B. (2012). Mandated literacy assessment and the reorganisation of teachers’ work: Federal policy and local effects. Critical Studies in Education, 53 (2), 119–136.

Comber, B. (2015). School literate repertoires: That was then, this is now. In J. Rowsell & J. Sefton-Green (Eds.), Revisiting learning lives: Longitudinal perspectives on researching learning and literacy (pp. 16–31). London: Routledge.

Comber, B. (2016). Literacy, place and pedagogies of possibility . New York: Routledge.

Comber, B., & Hill, S. (2000). Socio-economic disadvantage, literacy and social justice: Learning from longitudinal case study research. The Australian Educational Researcher, 27 (3), 79–98.

Comber, B., & Kerkham, L. (2016). Gus: I cannot write anything. In A. H. Dyson (Ed.), Child cultures, schooling and literacy: Global perspectives on children composing their lives (pp. 53–64). New York: Routledge.

Comber, H., & Nixon, H. (2011). Critical reading comprehension in an era of accountability. The Australian Educational Researcher, 38 (2), 167–179.

Comber, B., & Woods, A. (forthcoming). Pedagogies of belonging in literacy classrooms and beyond: What’s holding us back? In Paper presented to the Belonging in Education Symposium . Deakin University, May 30–31, 2016.

Comber, B., & Woods, A. (2016). Literacy teacher research in high poverty schools: Why it matters. In J. Lampert & B. Burnett (Eds.), Teacher education for high poverty schools (pp. 193–210). New York: Springer.

Chapter Google Scholar

Connell, R. W. (1993). Schools and social justice . Toronto: Our Schools/Our Selves Education Foundation.

Connell, R. W. (1994). Poverty and education. Harvard Educational Review, 64 (2), 125–149.

Cope, B., & Kalantzis, M. (Eds.). (2000). Multiliteracies: Literacy learning and the design of social futures . Melbourne: Macmillan.

Dorling, D. (2014). Inequality and the 1% . London: Verso.

Dyson, A. H. (Ed.). (2016). Child cultures, schooling and literacy: Global perspectives on children composing their lives . New York: Routledge.

Eagleton, T. (2015). Hope without optimism . New Haven: Yale University Press.

Foucault, M. (1979). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison . New York: Vintage Books.

Foucault, M. (1983). On the genealogy of ethics: An overview of a work in progress. An interview with Michel Foucault. In H. L. Dreyfus & P. Rabinow (Eds.), Michel Foucault: Beyond structuralism and hermeneutics (2nd ed., pp. 229–252). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Fraser, N. (2014). Transnationalizing the public sphere . Cambridge: Polity.

Freebody, P. (2003). Qualitative research in education: Interaction and practice . London: SAGE Publications.

Book Google Scholar

Gonksi, D., Boston, K., Greiner, K., Lawrence, C., Scales, B., & Tannock, P. (2011). Review of funding for schooling—Final report . Canberra: Australian Government.

Gorski, P. (2008). The myth of the “culture of poverty”. Educational Leadership, 65 (7), 32–37.

Grant, H. (2014). English as an additional language learners (EAL) and multimedia pedagogies. In A. Morgan, B. Comber, P. Freebody, & H. Nixon (Eds.), Literacy in the middle years: Learning from collaborative classroom research (pp. 35–50). Newtown: Primary English Teaching Association Australia.

Green, B. (1988). Subject-specific literacy and school learning: A focus on writing. Australian Journal of Education, 32 (2), 156–179.

Green, B., & Beavis, C. (2012). Introduction. In B. Green & C. Beavis (Eds.), Literacy in 3D: An integrated perspective in theory and practice (pp. 15–24). Camberwell, Victoria: ACER Press.

Greene, M. (1988). The dialectic of freedom . New York: Teachers College Press.

Griffith, A., & Smith, D. (2014). Under new public management: Institutional ethnographies of changing front-line work . Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Haberman, M. (1991). The pedagogy of poverty versus good teaching. Phi Delta Kappan, 73 (4), 290–294.

Hayes, D., Mills, M., Christie, P., & Lingard, B. (2006). Teachers and schooling making a difference . Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin.

Hull, G., & Stornaiuolo, A. (2014). Cosmopolitan literacies, social networks, and “proper distance”: Striving to understand in a global world. Curriculum Inquiry, 44 (1), 15–44.

Janks, H. (2010). Literacy and power . New York: Routledge.

Karmel, P. (1971). Education in South Australia: Report of the committee of enquiry into education in South Australia 1969–1970 . Adelaide, SA: Government Printer.

Karmel, P. (1973). Schools in Australia: Report of the interim committee of the Australian Schools Commission . Canberra, ACT: Australian Government Printers.

Kress, G., & van Leeuwen, T. (2006). Reading images: The grammar of visual design . London: Routledge.

Lingard, B., Thompson, G., & Sellar, S. (Eds.). (2016). National testing in schools: An Australian assessment . London: Routledge.

Louden, W., Rohl, M., Barratt-Pugh, C., Brown, C., Cairney, T., Elderfield, J., et al. (2005). In teachers’ hands: Effective teaching practices in the early years of schooling . Perth: Edith Cowan University.

Luke, A. (1995). Text and discourse in education: An introduction to critical discourse analysis. Review of Research in Education, 21 , 3–48.

Luke, A., & Freebody, P. (1997). The social practices of reading. In S. Muspratt, A. Luke, & P. Freebody (Eds.), Constructing critical literacies: Teaching and learning textual practices (pp. 195–225). St Leonards, NSW: Allen & Unwin.

Massey, D. (2005). For space . London: SAGE.

Moll, L. C., Amanti, C., Neff, D., & Gonzalez, N. (1992). Funds of knowledge for teaching: Using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory and Practice, 31 (2), 132–141.

Munns, G., Sawyer, W., & Cole, B. (Eds.). (2013). Exemplary teachers of students in poverty: The fair go team . London: Routledge.

Nixon, H., & Comber, B. (2006). The differential recognition of children’s resources in middle primary literacy classrooms. Literacy, 40 (3), 127–136.

Nixon, H., Comber, B., Grant, H., & Wells, M. (2012). Collaborative inquiries into literacy, place and identity in changing policy contexts: Implications for teacher development. In C. Day (Ed.), The Routledge international handbook of teacher and school development (pp. 175–184). London: Routledge.

Nuthall, G. (2007). The hidden lives of learners . Wellington: New Zealand Council for Educational Research Press.

Payne, R. (2012). A framework for understanding poverty workbook: 10 actions to educate students . Highlands, TX: aha! Process.

Pickett, K., & Wilkinson, R. (2009). The spirit level: Why equality is better for everyone . London: Penguin Books.

Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the twenty - first century (A. Goldhammer, trans.). Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Rappaport, J. (2000). Community narratives: Tales of terror and joy. American Journal of Community Psychology, 28 (1), 1–24.

Rogers, R., & Wetzel, M. M. (2013). Studying agency in literacy teacher education: A layered approach to positive discourse analysis. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies, 10 (1), 62–92.

Roy, A. (2014). Capitalism: A ghost story . London: Verso.

Smith, D. E. (1987). The everyday world as problematic: A feminist sociology . Boston: Northeastern University Press.

Smith, D. E. (2005). Institutional ethnography: A sociology for people . Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press.

Smith, D. E. (Ed.). (2007). Institutional ethnography as practice . Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Smyth, J., & Wrigley, T. (2013). Living on the edge: Rethinking poverty, class and schooling . New York: Peter Lang.

Thomson, P. (2002). Schooling the rustbelt kids: Making the difference in changing times . Stoke-on-Trent: Trentham Books.

Wells, M., & Trimboli, R. (2014). Place-conscious literacy pedagogies. In A. Morgan, B. Comber, P. Freebody, & H. Nixon (Eds.), Literacy in the middle years: Learning from collaborative classroom research (pp. 15–34). Newtown: Primary English Teaching Association Australia.

Wortham, S. (2006). Learning identity: The joint emergence of social identification and academic learning . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Zipin, L., Fataar, A., & Brennan, M. (2015). Can social realism do social justice? Debating the warrants for curriculum knowledge selection. Education as Change, 19 (2), 9–36. doi: 10.1080/16823206.2015.1085610 .

Download references

Acknowledgments

Many projects have informed this address, in particular, Educational leadership and turnaround literacy pedagogies, an Australian Research Council (ARC) Linkage Project (No. LP120100714) between the University of South Australia and the South Australian Department for Education and Child Development (DECD). The project was under taken between 2012 and 2015. The chief investigators were Robert Hattam (University of South Australia), Barbara Comber (Queensland University of Technology) and Deb Hayes (University of Sydney). The research associate was Lyn Kerkham (University of South Australia). I thank colleagues and friends whose conversations contributed to these ideas, including Rob Hattam, Deb Hayes, Barbara Kamler, Lyn Kerkham, Val Klenowski, Helen Nixon and Annette Woods. I recognise that much of my work is contingent upon the willingness of teachers to have me in their classrooms and acknowledge long-term co-researchers and friends Helen Grant, Ruth Trimboli and Marg Wells. Finally, I thank the helpful critical feedback from the reviewers of this paper.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Education, University of South Australia, Adelaide, SA, Australia

Barbara Comber

Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane City, QLD, Australia

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Barbara Comber .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Comber, B. Poverty, place and pedagogy in education: research stories from front-line workers. Aust. Educ. Res. 43 , 393–417 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-016-0212-9

Download citation

Received : 06 May 2016

Accepted : 03 August 2016

Published : 10 August 2016

Issue Date : September 2016

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-016-0212-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Teachers’ work

- Critical literacy

- Social justice

- Positive discourse analysis

- Place conscious pedagogy

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

202 Poverty Essay Topics & Examples

Poverty is one of the most pressing global issues affecting millions of individuals. We want to share some intriguing poverty essay topics and research questions for you to choose the titles of your paper correctly. With the help of this collection, you can explore the intricate dimensions of poverty, its causes, consequences, and potential solutions. Have a look at our poverty topics to get a deeper understanding of poverty and its implications.

💸 TOP 10 Poverty Essay Topics

🏆 best poverty essay examples, 👍 catchy poverty research topics, 🧐 thought-provoking poverty topics, 🎓 interesting poverty essay topics, ❓ research questions about poverty.

- Poverty: Causes and Solutions to Problem

- Poverty as a Social Problem

- Homelessness and Poverty in Developed and Developing Countries

- The Eliminating Poverty Strategies

- Correlation Between Poverty and Juvenile Delinquency

- Poverty Effects on an Individual

- Poverty Effects on Mental Health

- Global Poverty and Nursing Intervention It is evident that poor health and poverty are closely linked. Community nurses who are conversant with the dynamics of the health of the poor can run successful health promotion initiatives.

- Degrading Consequences of Poverty in “The Pearl” by John Steinbeck Poverty is identity in John Steinbeck’s The Pearl, and the main character Kino, a poor fisherman, manifests a transformation in his identity,

- The Orthodox and Alternative Poverty Explanations Comparison Poverty has over the years become a worldwide subject of concern for economies. This essay will explore two theories- the orthodox and the alternative theories to poverty.

- Relationship Between Poverty and Crime The paper makes the case and discusses inequality rather than poverty being the prime reason for people committing crimes.

- Urbanization and Poverty in “Slumdog Millionaire” Film Boyle’s movie, “Slumdog Millionaire,” is one of many successful attempts to depict the conditions in which people who are below the poverty level live.

- Effects of Poverty on Education in the USA Colleges It is clear that poverty affects not only the living standards and lifestyle of people but also the college education in the United States of America.

- Poverty from Functionalist and Rational Choice Perspectives Poverty is a persistent social phenomenon, which can be examined from both the functionalist and rational choice perspectives.

- Effects of Divorce and Poverty in Families In the event of a divorce children are tremendously affected and in most cases attention is not given to them the way it should.

- Bullying in Poverty and Child Development Context The aim of the present paper is to investigate how Bullying, as a factor associated with poverty, affects child development.

- The Analysis of Henry George’s “Crime of Poverty” Reviewing Henry George’s Crime of Poverty, which was written in 1885, in its historical context can shed light on socio-political developments within the country.

- Vicious Circle of Poverty In this essay, the author describes the problem of poverty, its causes and ways of optimizing the economy and increasing production efficiency.

- Poverty and Theories of Its Causes Poverty in schools is a significant barrier to education that needs to be overcome to improve teaching and learning.

- Diana George’s Changing the Face of Poverty Book Diana George’s book, Changing the Face of Poverty, begins with a summary of several Thanksgiving commercials and catalogs.

- The Problem of Poverty in Art of Different Periods Artists have always been at the forefront of addressing social issues, by depicting them in their works and attempting to draw the attention of the public to sensitive topics.

- The Poverty as an Ethical Issue Looking at poverty as an ethical issue, we have to consider the fact that there are people who control resource distribution, which then leads to wealth or poverty in a community.

- “What Is Poverty” by Dalrymple The purpose of this paper is to present Dalrymple point of view and analyze it by applying philosophical concepts.

- Poverty and Homelessness in Jackson, Mississippi This paper will review the statistics and information about poverty and homelessness in Jackson, MS. The community of Black Americans is suffering from poverty and homelessness.

- Poverty in “On Dumpster Diving” by Lars Eighner Essay “On Dumpster Diving” by Lars Eighner evokes compassion and prompts individuals to think about social problems existing nowadays.

- Poverty in “Serving in Florida” and “Dumpster Diving” “Serving in Florida” by Barbara Ehrenreich describes the harsh reality of living in poverty while concentrating on the pragmatic dimension of the issue

- How Does Poverty Affect Crime Rates? On the basis of this research question, the study could be organized and conducted to prove the following hypothesis – when poverty increases, crime rates increase as well.

- Empowerment and Poverty Reduction The objective of this essay will be to highlight the health issues caused by poverty and the strategies needed to change the situation of poor people through empowerment.

- Rutger Bregman’s Statement of Poverty The paper states that Bregman’s approach to poverty and the proposal of guaranteed regular income is more suitable for developing countries.

- Poverty Relation With Immigrants Poverty-related immigration is usually caused by population pressures; as the natural land becomes less productive due to the increased technology and industrial production.

- The City of Atlanta, Georgia: Poverty and Homelessness This project goal is to address several issues in the community of the City of Atlanta. Georgia. The primary concern is the high rate of poverty and homelessness in the city.

- The Ideal Society: Social Stratification and Poverty The paper argues social classes exist because of the variations in socioeconomic capacities in the world; however, an ideal society can eliminate them.

- How Poverty Impacts on Life Chances, Experiences and Opportunities for Young People The paper specifically dwells on the social exclusion, class, and labeling theories to place youth poverty in its social context.

- Poverty from Christian Perspective Christians perceive poverty differently than people without faith, noting the necessity for integrated support to help those in need.

- Poverty: Behavioral, Structural, Political Factors The research paper will primarily argue that poverty is a problem caused by a combination of behavioral, structural, and political systems.

- Poverty in Young and Middle Adulthood According to functionalism, poverty is a dysfunctional aspect of interrelated components, which is the result of improper structuring.

- Poverty: “$2.00 a Day” Book by Edin and Schaefer In their book “$2.00 a Day: Living on Almost Nothing in America,” Edin and Schaefer investigate problems that people who live in poverty face every day.

- Lessons Learned From the Poverty Simulation The main lesson learned from the poverty simulation is that poverty is far more serious than depicted in the media, which carelessly documents the numbers of poor people.

- Wealth and Poverty Sources in America This paper explains the causes and consequences of poverty in the United States, programs and systems to combat it, and government benefits to support families in distress.

- Poverty, Faith, and Justice: ”Liberating God of Life” by Elizabeth Johnson “Liberating God of Life Context: Wretched Poverty” by Johnson constructs that the main goal of human beings is to combat structural violence toward the poor.

- Carl Hart’s Talk on Racism, Poverty, and Drugs In his TED Talk, Carl Hart, a professor of neuroscience at Columbia University who studies drug addiction, exposes a relationship between racism, poverty, and drugs.

- The Concept of Poverty This work is aimed at identifying the key aspects associated with poverty and its impact on the lives of people in different contexts.

- World Poverty as a Global Social Problem Poverty and the key methods helping to reduce it attract the attention of numerous researchers in different areas of expertise.

- How Poverty Affects Early Education? A number of people live in poor conditions. According to the researchers of the Department of Education in the United States, poverty influences academic performance in an adverse way.

- Immigrant Children and Poverty Immigrant child poverty poses considerable social predicaments, because it is related to several long lasting school and development linked difficulties.

- Poverty and Social Causation Hypothesis There are two identified approaches to poverty on cultural and individual levels as formulated by Turner and Lehning

- Poverty and Mental Health Correlation The analysis of the articles provides a comprehensive understanding of the poverty and mental health correlation scale and its current state.

- Utilitarianism: Poverty Reduction Through Charity This paper shows that poverty levels can be reduced if wealthy individuals donate a part of their earnings, using the main principles of the utilitarian theory.

- Poverty, Politics, and Profit as US Policy Issue Poverty remains one of the most intractable problems to deal with, both in the international community and in the United States.

- Poverty in Ghana: Reasons and Solution Strategy The analysis provided in the paper revealed some internal and external factors that deter better economic and human development in Ghana.

- Christ’s Relationships with Wealth and Poverty This paper attempts to examine Christ’s relationships with wealth, money and poverty and provide an analysis of these relationships.

- Poverty and Poor Health: Access to Healthcare Services Health disparities affecting ethnical and racial groups, as well as people with low income, operate through the social environments, access to healthcare services.

- Wealth, Poverty, and Systems of Economic Class By examining wealth, poverty, and economic classes from the perspective of social justice, the socioeconomic inequalities persistent in society will become clear.

- Love and Poverty in My Papa’s Waltz by Theodore Roethke The present paper includes a brief analysis of the poem ‘My Papa’s Waltz’ with a focus on imagery and figurative language.

- Global Poverty and Human Development Poverty rates across the globe continue to be a major issue that could impair the progress of humanity as a whole.

- Attitudes to Poverty: Singer’s Arguments Singer argues against the observation by the rich than helping one poor person can repeat over and over again until the rich eventually becomes poor.

- The U.S. Education: Effect of Poverty Poverty effects on education would stretch to other aspects of life and this justifies that, poverty in United States not only affects social lifestyles but also college education.

- Poverty and Homelessness in Canada Poverty and homelessness figure prominently in government policies and the aims of many social service organizations even in a country like Canada.

- Poverty and Homelessness: Dimensions and Constructions With the growth of the economy and the failure of employment, the number of people living in poverty and without shelter increases.

- The Issue of Poverty in Savannah, Georgia The paper addresses a serious issue that still affects Savannah, Georgia, and it is poverty. This problem influences both individuals and society.

- Child’s Development and Education: Negative Effects of Poverty Some adverse effects of poverty on a child’s development and education are poor performance academically, stagnant physical development, and behavioral issues.

- Evaluating the “Expertness” of the Southern Law Poverty Center The Southern Law Poverty Center has garnered controversy for its list of so-called “hate groups” and how it spends its half-billion-dollar budget.

- Poverty and Inequality: Income and Wealth Inequality The Stanford Center of Poverty and Inequality does an in-depth job of finding causes and capturing statistics on poverty and inequality.

- Hard Questions About Living in Poverty or Slavery The paper aims to find the answers to several questions, for example, how to remain human while living in the conditions of extreme poverty or slavery.

- Global Poverty and Education Economic theories like liberalization, deregulation, and privatization were developed to address global poverty.

- African American Families in Poverty Even though the United States declares the equality of white and black people quite often, the socio-economic situation of African Americans still need changes for the better.

- Gay and Poverty Marriage The institution of family and the issues of marriage play a crucial role in society today. Marriage status determines relations between spouses and their relations with the state.

- Poverty in New York City and Media Representation This paper will analyze recent news publications regarding the urban issue of poverty in NYC and determine how the city is represented in the media.

- Poverty from a Sociological Standpoint Poverty is a complex phenomenon, in which many explicit and implicit factors are involved. Some individuals tend not to perceive this phenomenon as critical.

- Can Marriage End Poverty? Marriages to some degree alleviate poverty, but not all marriages can do so. Only marriages build on sound principles can achieve such a feat.

- Child Poverty Assessment in Canada Child poverty is not only the problem of children but also a threat to the development of a country. In Canada today, every fifth child is estimated to be affected by poverty.

- Poverty in the “LaLee’s Kin” Documentary In this paper, the author will analyse poverty as a social problem in the Mississippi Delta. The issue will be analysed from the perspective of the documentary “LaLee’s Kin”.

- Poverty: The Negative Effects on Children Poor children often do not have access to quality healthcare, so they are sicker and more likely to miss school. Poor children are less likely to have weather-appropriate clothes.

- The Issue of the Poverty in the USA The most sustainable technique for poverty elimination in the United States is ensuring equitable resource distribution, education, and healthcare access.

- Poverty and How This Problem Can Be Solved Poverty is one of the global social problems of our time, existing even in the countries of the first world despite the generally high standard of living of people.

- Poverty: An Interplay of Social and Economic Psychology The paper demonstrates an interplay of social and economic psychology to scrutinize the poverty that has given rise to a paycheck-to-paycheck nation.

- Refugees: Poverty, Hunger, Climate Change, and Violence Individuals struggling with poverty, hunger, climate change, and gender-based violence and persecution may consider fleeing to the United States.

- The Extent of Poverty in the United States The paper states that the issue of poverty in the USA is induced by a butterfly effect, starting with widespread discrimination and lack of support.

- Poverty in Puerto Rico and Eradication Measures Studying Puerto Rican poverty as a social problem is essential because it helps identify the causes, effects, and eradication measures in Puerto Rico and other nations.

- Human Trafficking and Poverty Issues in Modern Society The problem of human trafficking affects people all over the world, which defines the need for a comprehensive approach to this issue from the criminology perspective.

- Poverty and Homelessness Among African Americans Even though the U.S. is wealthy and prosperous by global measures, poverty has persisted in the area, with Blacks accounting for a larger share.

- Poverty: Resilience and Intersectionality Theories This paper assesses the impact of poverty on adult life, looking at risk and protective factors and the impact of power and oppression on the experience of poverty.

- Human Trafficking and Poverty Discussion This paper synthesize information on human trafficking and poverty by providing an annotated bibliography of relevant sources.

- Economic Inequality and Its Relationship to Poverty This research paper will discuss the problem of economic inequality and show how this concept relates to poverty.

- Discussion of Poverty and Social Trends The advances and consequent demands on society grounded on social class and trends profoundly influence poverty levels.

- Life of Humanity: Inequality, Poverty, and Tolerance The paper concerns the times in which humanity, and especially the American people, live, not forgetting about inequality, poverty, and tolerance.

- Poverty, Its Social Context, and Solutions Understanding past and present poverty statistics is essential for developing effective policies to reduce the rate of poverty at the national level.

- Poverty in the US: “Down and Out in Paris and London” by Orwell The essay compares the era of George Orwell to the United States today based on the book “Down and Out in Paris and London” in terms of poverty.

- Is It Possible to Reduce Poverty in the United States? Reducing poverty in the United States is possible if such areas as education, employment, and health care are properly examined and improved for the public’s good.

- Poverty Among Seniors Age 65 and Above The social problem is the high poverty rate among older people aged 65 and above. Currently, there are millions of elderly who are living below the poverty line.

- Poverty in 1930s Europe and in the 21st Century US The true face of poverty may be found in rural portions of the United States’ South and Southwest regions, where living standards have plummeted, and industries have yet to begin.

- Chronic Poverty and Disability in the UK The country exhibits absolute poverty and many other social issues associated with under-developed states. The issue is resolvable through policy changes.

- Social Issue of Poverty in America The paper states that poverty is not an individual’s fault but rather a direct result of social, economic, and political circumstances.

- Poverty, Housing, and Community Benefits The community will benefit from affordable housing and business places, creating job opportunities for the residents and mentoring and apprenticeship.

- Racial Discrimination and Poverty Racial discrimination and poverty have resulted in health disparities and low living standards among African Americans in the United States.

- Poverty and Its Negative Impact on Society Poverty affects many people globally, experiencing poor living conditions, limited access to education, unemployment, poor infrastructure, malnutrition, and child labor.

- The Uniqueness of the Extent of the Poverty Rate in America The United States ranked near the top regarding poverty and inequality, and compared to other developed countries, income and wealth disparity in the United States is high.

- Globalization and Poverty: Trade Openness and Poverty Reduction in Nigeria Globalization can be defined as the process of interdependence on the global culture, economy, and population. It is brought about by cross-border trade.

- Should People Be Ashamed of Poverty? People on welfare should not feel ashamed because the definition of poverty does not necessarily place them in the category of the poor.

- Inequality and Poverty in the United States One of the most common myths is that the United States (US) is a meritocracy, where anyone can succeed if they maintain industriousness.

- Christian Perspective on Poverty Several Christian interpretations have different ideas about poverty and wealth. This paper aims to discuss the Christian perspective on poverty.

- Poverty and Problematic Housing in California The question is what are the most vulnerable aspects of the administrative system that lead to an aggravation of the situation of homelessness.

- Race, Poverty, and Incarceration in the United States The American justice system, in its current form, promotes disproportionally high incarceration rates among blacks and, to a lesser degree, Latinos from poor urban neighborhoods.

- Global Poverty and Factors of Influence This paper introduces a complex perspective on the issue of global poverty, namely, incorporating economic, social, cultural, and environmental factors into the analysis.

- Poverty Causes and Solutions in Latin America This paper aims to understand the importance of the interference of Europe in Latin American affairs and its referring to the general principles of poverty.

- Gary Haugen’s Speech on Violence and Poverty In his speech, Gary Haugen discusses the causes of poverty and concludes that violence is a hidden problem that should be addressed and eliminated.

- The Child Poverty Problem in Alabama

- Poverty Among Blacks in America

- Relationship Between Poverty and Health People in 2020

- How Access to Clean Water Influences the Problem of Poverty

- Solving the Problem of Poverty in Mendocino County

- “Promises and Poverty”: Starbucks Conceals Poverty and Deterioration of the Environment

- Global Poverty and Economic Globalization Relations

- Poverty Prevalence and Causes in the United States

- Policy Development to Overcome Child Poverty in the U.S.

- Global Poverty: Tendencies, Causes and Impacts

- The Impact of Poverty on Children and Minority Groups

- Habitat for the Homeless: Poverty

- The Problem of Poverty Among Children

- Global Issues of World Poverty: Reasons and Solutions

- Effects of Poverty on Health Care in the US and Afghanistan

- Poverty Among Children from Immigrant Workers

- “8 Million Have Slipped Into Poverty Since May as Federal Aid Has Dried Up” by Jason DeParle

- Teenage Pregnancy After Exposure to Poverty: Causation and Communication

- Poverty and Covid-19 in Developing Countries

- Poverty in America: Socio-Economic Inequality

- Poverty and Its Effects Upon Special Populations

- Global Poverty and Education Correlation

- American Dream and Poverty in the United States

- Changing the Face of Poverty

- The Link Between Poverty and Criminal Behavior

- The Cost of Saving: The Problem of Poverty

- Sociological Issues About Social Class and Poverty, Race and Ethnicity, Gender

- Speech on Mother Teresa: Poverty and Interiority in Mother Teresa

- Poverty: Causes and Reduction Measures

- Federal Poverty, Welfare, and Unemployment Policies