Holiday Sale: 40% Off Self-Guided Courses, 10% Off Gifted Course Credit! Learn more »

The Importance of Word Choice in Writing

Sean Glatch | December 2, 2022 | 6 Comments

All strong writers have something in common: they understand the value of word choice in writing. Strong word choice uses vocabulary and language to maximum effect, creating clear moods and images and making your stories and poems more powerful and vivid.

The meaning of “word choice” may seem self-explanatory, but to truly transform your style and writing, we need to dissect the elements of choosing the right word. This article will explore what word choice is, and offer some examples of effective word choice, before giving you 5 word choice exercises to try for yourself .

Word Choice Definition: The Four Elements of Word Choice

The definition of word choice extends far beyond the simplicity of “choosing the right words.” Choosing the right word takes into consideration many different factors, and finding the word that packs the most punch requires both a great vocabulary and a great understanding of the nuances in English.

Choosing the right word involves the following four considerations, with word choice examples.

Words can be chosen for one of two meanings: the denotative meaning or the connotative meaning. Denotation refers to the word’s basic, literal dictionary definition and usage. By contrast, connotation refers to how the word is being used in its given context: which of that word’s many uses, associations, and connections are being employed.

A word’s denotative meaning is its literal dictionary definition, while its connotative meaning is the web of uses and associations it carries in context.

We play with denotations and connotations all the time in colloquial English. As a simple example, when someone says “greaaaaaat” sarcastically, we know that what they’re referring to isn’t “great” at all. In context, the word “great” connotes its opposite: something so bad that calling it “great” is intentionally ridiculous. When we use words connotatively, we’re letting context drive the meaning of the sentence.

The rich web of connotations in language are crucial to all writing, and perhaps especially so to poetry, as in the following lines from Derek Walcott’s Nobel-prize-winning epic poem Omeros :

In hill-towns, from San Fernando to Mayagüez, the same sunrise stirred the feathered lances of cane down the archipelago’s highways. The first breeze

rattled the spears and their noise was like distant rain marching down from the hills, like a shell at your ears.

Sugar cane isn’t, literally, made of “feathered lances,” which would literally denote “long metal spears adorned with bird feathers”; but feathered connotes “branching out,” the way sugar cane does, and lances connotes something tall, straight, and pointy, as sugar cane is. Together, those two words create a powerfully true visual image of sugar cane—in addition to establishing the martial language (“spears,” “marching”) used elsewhere in the passage.

Whether in poetry or prose, strong word choice can unlock images, emotions, and more in the reader, and the associations and connotations that words bring with them play a crucial role in this.

2. Specificity

Use words that are both correct in meaning and specific in description.

In the sprawling English language, one word can have dozens of synonyms. That’s why it’s important to use words that are both correct in meaning and specific in description. Words like “good,” “average,” and “awful” are far less descriptive and specific than words like “liberating” (not just good but good and freeing ), “C student” (not just average but academically average), and “despicable” (not just awful but morally awful). These latter words pack more meaning than their blander counterparts.

Since more precise words give the reader added context, specificity also opens the door for more poetic opportunities. Take the short poem “[You Fit Into Me]” by Margaret Atwood.

You fit into me like a hook into an eye

A fish hook

An open eye

The first stanza feels almost romantic until we read the second stanza. By clarifying her language, Atwood creates a simple yet highly emotive duality.

This is also why writers like Stephen King advocate against the use of adverbs (adjectives that modify verbs or other adjectives, like “very”). If your language is precise, you don’t need adverbs to modify the verbs or adjectives, as those words are already doing enough work. Consider the following comparison:

Weak description with adverbs: He cooks quite badly; the food is almost always extremely overdone.

Strong description, no adverbs: He incinerates food.

Of course, non-specific words are sometimes the best word, too! These words are often colloquially used, so they’re great for writing description, writing through a first-person narrative, or for transitional passages of prose.

3. Audience

Good word choice takes the reader into consideration. You probably wouldn’t use words like “lugubrious” or “luculent” in a young adult novel, nor would you use words like “silly” or “wonky” in a legal document.

This is another way of saying that word choice conveys not only direct meaning, but also a web of associations and feelings that contribute to building the reader’s world. What world does the word “wonky” help build for your reader, and what world does the word “seditious” help build? Depending on the overall environment you’re working to create for the reader, either word could be perfect—or way out of place.

Consider your word choice to be the fingerprint of your writing.

Consider your word choice to be the fingerprint of your writing. Every writer uses words differently, and as those words come to form poems, stories, and books, your unique grasp on the English language will be recognizable by all your readers.

Style isn’t something you can point to, but rather a way of describing how a writer writes. Ernest Hemingway, for example, is known for his terse, no-nonsense, to-the-point styles of description. Virginia Woolf, by contrast, is known for writing that’s poetic, intense, and melodramatic, and James Joyce for his lofty, superfluous writing style.

Here’s a paragraph from Joyce:

Had Pyrrhus not fallen by a beldam’s hand in Argos or Julius Caesar not been knifed to death. They are not to be thought away. Time has branded them and fettered they are lodged in the room of the infinite possibilities they have ousted.

And here’s one from Hemingway:

Bill had gone into the bar. He was standing talking with Brett, who was sitting on a high stool, her legs crossed. She had no stockings on.

Style is best observed and developed through a portfolio of writing. As you write more and form an identity as a writer, the bits of style in your writing will form constellations.

Word Choice in Writing: The Importance of Verbs

Before we offer some word choice exercises to expand your writing horizons, we first want to mention the importance of verbs. Verbs, as you may recall, are the “action” of the sentence—they describe what the subject of the sentence actually does. Unless you are intentionally breaking grammar rules, all sentences must have a verb, otherwise they don’t communicate much to the reader.

Because verbs are the most important part of the sentence, they are something you must focus on when expanding the reaches of your word choice. Verbs are the most widely variegated units of language; the more “things” you can do in the world, the more verbs there are to describe them, making them great vehicles for both figurative language and vivid description.

Consider the following three sentences:

- The road runs through the hills.

- The road curves through the hills.

- The road meanders through the hills.

Which sentence is the most descriptive? Though each of them has the same subject, object, and number of words, the third sentence creates the clearest image. The reader can visualize a road curving left and right through a hilly terrain, whereas the first two sentences require more thought to see clearly.

Finally, this resource on verb usage does a great job at highlighting how to invent and expand your verb choice.

Word Choice in Writing: Economy and Concision

Strong word choice means that every word you write packs a punch. As we’ve seen with adverbs above, you may find that your writing becomes more concise and economical—delivering more impact per word. Above all, you may find that you omit needless words .

Omit needless words is, in fact, a general order issued by Strunk and White in their classic Elements of Style . As they explain it:

Vigorous writing is concise. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentences, for the same reason that a drawing should have no unnecessary lines and a machine no unnecessary parts. This requires not that the writer make all his sentences short, or that he avoid all detail and treat his subjects only in outline, but that every word tell.

It’s worth repeating that this doesn’t mean your writing becomes clipped or terse, but simply that “every word tell.” As our word choice improves—as we omit needless words and express ourselves more precisely—our writing becomes richer, whether we write in long or short sentences.

As an example, here’s the opening sentence of a random personal essay from a high school test preparation handbook:

The world is filled with a numerous amount of student athletes that could somewhere down the road have a bright future.

Most words in this sentence are needless. It could be edited down to:

Many student athletes could have a bright future.

Now let’s take some famous lines from Shakespeare’s Macbeth . Can you remove a single word without sacrificing an enormous richness of meaning?

Out, out, brief candle! Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player, That struts and frets his hour upon the stage, And then is heard no more. It is a tale Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, Signifying nothing.

In strong writing, every single word is chosen for maximum impact. This is the true meaning of concise or economical writing.

5 Word Choice Exercises to Sharpen Your Writing

With our word choice definition in mind, as well as our discussions of verb use and concision, let’s explore the following exercises to put theory into practice. As you play around with words in the following word choice exercises, be sure to consider meaning, specificity, style, and (if applicable) audience.

1. Build Moods With Word Choice

Writers fine-tune their words because the right vocabulary will build lush, emotive worlds. As you expand your word choice and consider the weight of each word, focus on targeting precise emotions in your descriptions and figurative language.

This kind of point is best illustrated through word choice examples. An example of magnificent language is the poem “ In Defense of Small Towns ” by Oliver de la Paz. The poem’s ambivalent feelings toward small hometowns presents itself through the mood of the writing.

The poem is filled with tense descriptions, like “animal deaths and toughened hay” and “breeches speared with oil and diesel,” which present the small town as stoic and masculine. This, reinforced by the terse stanzas and the rare “chances for forgiveness,” offers us a bleak view of the town; yet it’s still a town where everything is important, from “the outline of every leaf” to the weightless flight of cattail seeds.

The writing’s terse, heavy mood exists because of the poem’s juxtaposition of masculine and feminine words. The challenge of building a mood produces this poem’s gravity and sincerity.

Try to write a poem, or even a sentence, that evokes a particular mood through words that bring that word to mind. Here’s an example:

- What mood do you want to evoke? flighty

- What words feel like they evoke that mood? not sure, whatever, maybe, perhaps, tomorrow, sometimes, sigh

- Try it in a sentence: “Maybe tomorrow we could see about looking at the lab results.” She sighed. “Perhaps.”

2. Invent New Words and Terms

A common question writers ask is, What is one way to revise for word choice? One trick to try is to make up new language in your revisions.

If you create language at a crucial moment, you might be able to highlight something that our current language can’t.

In the same way that unusual verbs highlight the action and style of your story, inventing words that don’t exist can also create powerful diction. Of course, your writing shouldn’t overflow with made-up words and pretentious portmanteaus, but if you create language at a crucial moment, you might be able to highlight something that our current language can’t.

A great example of an invented word is the phrase “wine-dark sea.” Understanding this invention requires a bit of history; in short, Homer describes the sea as “οἶνοψ πόντος”, or “wine-faced.” “Wine-dark,” then, is a poetic translation, a kind of kenning for the sea’s mystery.

Why “wine-dark” specifically? Perhaps because, like the sea, wine changes us; maybe the eyes of the sea are dark, as eyes often darken with wine; perhaps the sea is like a face, an inversion, a reflection of the self. In its endlessness, we see what we normally cannot.

Thus, “wine-dark” is a poetic combination of words that leads to intensive literary analysis. For a less historical example, I’m currently working on my poetry thesis, with pop culture monsters being the central theme of the poems. In one poem, I describe love as being “frankensteined.” By using this monstrous made-up verb in place of “stitched,” the poem’s attitude toward love is much clearer.

Try inventing a word or phrase whose meaning will be as clear to the reader as “wine-dark sea.” Here’s an example:

- What do you want to describe? feeling sorry for yourself because you’ve been stressed out for a long time

- What are some words that this feeling brings up? self-pity, sympathy, sadness, stress, compassion, busyness, love, anxiety, pity party, feeling sorry for yourself

- What are some fun ways to combine these words? sadxiety, stresslove

- Try it in a sentence: As all-nighter wore on, my anxiety softened into sadxiety: still edgy, but soft in the middle.

3. Only Use Words of Certain Etymologies

One of the reasons that the English language is so large and inconsistent is that it borrows words from every language. When you dig back into the history of loanwords, the English language is incredibly interesting!

(For example, many of our legal terms, such as judge , jury , and plaintiff , come from French. When the Normans [old French-speakers from Northern France] conquered England, their language became the language of power and nobility, so we retained many of our legal terms from when the French ruled the British Isles.)

Nerdy linguistics aside, etymologies also make for a fun word choice exercise. Try forcing yourself to write a poem or a story only using words of certain etymologies and avoiding others. For example, if you’re only allowed to use nouns and verbs that we borrowed from the French, then you can’t use Anglo-Saxon nouns like “cow,” “swine,” or “chicken,” but you can use French loanwords like “beef,” “pork,” and “poultry.”

Experiment with word etymologies and see how they affect the mood of your writing. You might find this to be an impactful facet of your word choice. You can Google “__ etymology” for any word to see its origin, and “__ synonym” to see synonyms.

Try writing a sentence only with roots from a single origin. (You can ignore common words like “the,” “a,” “of,” and so on.)

- What do you want to write? The apple rolled off the table.

- Try a first etymology: German: The apple wobbled off the bench.

- Try a second: Latin: The russet fruit rolled off the table.

4. Write in E-Prime

E-Prime Writing describes a writing style where you only write using the active voice. By eschewing all forms of the verb “to be”—using words such as “is,” “am,” “are,” “was,” and other “being” verbs—your writing should feel more clear, active, and precise!

E-Prime not only removes the passive voice (“The bottle was picked up by James”), but it gets at the reality that many sentences using to be are weakly constructed, even if they’re technically in the active voice.

Of course, E-Prime writing isn’t the best type of writing for every project. The above paragraph is written in E-Prime, but stretching it out across this entire article would be tricky. The intent of E-Prime writing is to make all of your subjects active and to make your verbs more impactful. While this is a fun word choice exercise and a great way to create memorable language, it probably isn’t sustainable for a long writing project.

Try writing a paragraph in E-Prime:

- What do you want to write? Of course, E-Prime writing isn’t the best type of writing for every project. The above paragraph is written in E-Prime, but stretching it out across this entire article would be tricky. The intent of E-Prime writing is to make all of your subjects active and to make your verbs more impactful. While this is a fun word choice exercise and a great way to create memorable language, it probably isn’t sustainable for a long writing project.

- Converted to E-Prime: Of course, E-Prime writing won’t best suit every project. The above paragraph uses E-Prime, but stretching it out across this entire article would carry challenges. E-Prime writing endeavors to make all of your subjects active, and your verbs more impactful. While this word choice exercise can bring enjoyment and create memorable language, you probably can’t sustain it over a long writing project.

5. Write Blackout Poetry

Blackout poetry , also known as Found Poetry, is a visual creative writing project. You take a page from a published source and create a poem by blacking out other words until your circled words create a new poem. The challenge is that you’re limited to the words on a page, so you need a charged use of both space and language to make a compelling blackout poem.

Blackout poetry bottoms out our list of great word choice exercises because it forces you to consider the elements of word choice. With blackout poems, certain words might be read connotatively rather than denotatively, or you might change the meaning and specificity of a word by using other words nearby. Language is at its most fluid and interpretive in blackout poems!

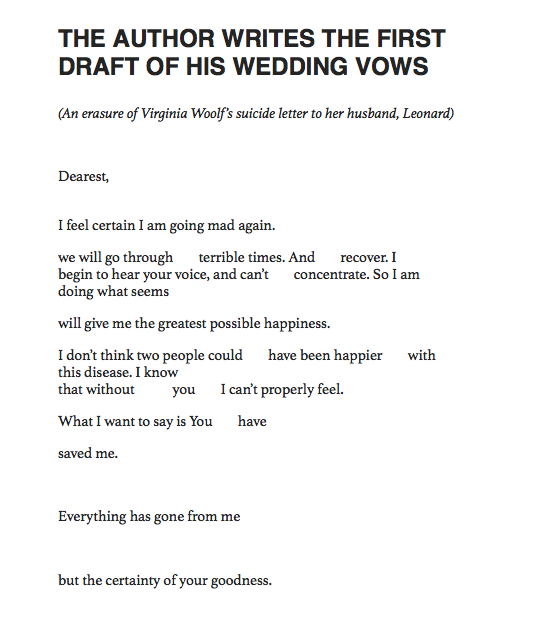

For a great word choice example using blackout poetry, read “ The Author Writes the First Draft of His Wedding Vows ” by Hanif Willis-Abdurraqib. Here it is visually:

Source: https://decreation.tumblr.com/post/620222983530807296/from-the-crown-aint-worth-much-by-hanif

Pick a favorite poem of your own and make something completely new out of it using blackout poetry.

How to Expand Your Vocabulary

Vocabulary is a last topic in word choice. The more words in your arsenal, the better. Great word choice doesn’t rely on a large vocabulary, but knowing more words will always help! So, how do you expand your vocabulary?

The simplest way to expand your vocabulary is by reading.

The simplest answer, and the one you’ll hear the most often, is by reading. The more literature you consume, the more examples you’ll see of great words using the four elements of word choice.

Of course, there are also some great programs for expanding your vocabulary as well. If you’re looking to use words like “lachrymose” in a sentence, take a look at the following vocab builders:

- Dictionary.com’s Word-of-the-Day

- Vocabulary.com Games

- Merriam Webster’s Vocab Quizzes

Improve Your Word Choice With Writers.com’s Online Writing Courses

Looking for more writing exercises ? Need more help choosing the right words? The instructors at Writers.com are masters of the craft. Take a look at our upcoming course offerings and join our community!

Sean Glatch

Interesting read. Would have appreciated some exercises to brighten our word choices.

The Real Person!

Definitely! This link takes you directly to the word choice exercises: http://writers.com/word-choice-in-writing#exercises

Let us know if you try any of them!

I have written three novels and two children’s books without “To Be Verbs!”

http://www.mysteriousgems.net

E-Prime offers writers and readers more cogent and descriptive language by removing useless irregular verbs as To Be.

Writers have credited me with the first fiction novel ever written in E-Prime. I find it useful, I employ it 100% of the time in my fiction and about 90% in other forms.

[…] suggest looking through the Meaning and Specificity sections of “The Importance of Word Choice in Writing” by Sean Glatch, as these areas of writing will give you a breakdown about denotive and […]

Thank you for posting this excellent essay. It is now stashed in my “favorites”. Also, I loved the poem “In Defense of Small Towns”. Gorgeous writing. I will purchase the collection “Requiem for the Orchard”.

Again. Thank you.

Rebecca Hanley

I’m so glad this article was useful, Rebecca! Thanks for commenting, and I hope you enjoy Requiem for the Orchard.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Word Choice

What this handout is about.

This handout can help you revise your papers for word-level clarity, eliminate wordiness and avoid clichés, find the words that best express your ideas, and choose words that suit an academic audience.

Introduction

Writing is a series of choices. As you work on a paper, you choose your topic, your approach, your sources, and your thesis; when it’s time to write, you have to choose the words you will use to express your ideas and decide how you will arrange those words into sentences and paragraphs. As you revise your draft, you make more choices. You might ask yourself, “Is this really what I mean?” or “Will readers understand this?” or “Does this sound good?” Finding words that capture your meaning and convey that meaning to your readers is challenging. When your instructors write things like “awkward,” “vague,” or “wordy” on your draft, they are letting you know that they want you to work on word choice. This handout will explain some common issues related to word choice and give you strategies for choosing the best words as you revise your drafts.

As you read further into the handout, keep in mind that it can sometimes take more time to “save” words from your original sentence than to write a brand new sentence to convey the same meaning or idea. Don’t be too attached to what you’ve already written; if you are willing to start a sentence fresh, you may be able to choose words with greater clarity.

For tips on making more substantial revisions, take a look at our handouts on reorganizing drafts and revising drafts .

“Awkward,” “vague,” and “unclear” word choice

So: you write a paper that makes perfect sense to you, but it comes back with “awkward” scribbled throughout the margins. Why, you wonder, are instructors so fond of terms like “awkward”? Most instructors use terms like this to draw your attention to sentences they had trouble understanding and to encourage you to rewrite those sentences more clearly.

Difficulties with word choice aren’t the only cause of awkwardness, vagueness, or other problems with clarity. Sometimes a sentence is hard to follow because there is a grammatical problem with it or because of the syntax (the way the words and phrases are put together). Here’s an example: “Having finished with studying, the pizza was quickly eaten.” This sentence isn’t hard to understand because of the words I chose—everybody knows what studying, pizza, and eating are. The problem here is that readers will naturally assume that first bit of the sentence “(Having finished with studying”) goes with the next noun that follows it—which, in this case, is “the pizza”! It doesn’t make a lot of sense to imply that the pizza was studying. What I was actually trying to express was something more like this: “Having finished with studying, the students quickly ate the pizza.” If you have a sentence that has been marked “awkward,” “vague,” or “unclear,” try to think about it from a reader’s point of view—see if you can tell where it changes direction or leaves out important information.

Sometimes, though, problems with clarity are a matter of word choice. See if you recognize any of these issues:

- Misused words —the word doesn’t actually mean what the writer thinks it does. Example : Cree Indians were a monotonous culture until French and British settlers arrived. Revision: Cree Indians were a homogenous culture.

- Words with unwanted connotations or meanings. Example : I sprayed the ants in their private places. Revision: I sprayed the ants in their hiding places.

- Using a pronoun when readers can’t tell whom/what it refers to. Example : My cousin Jake hugged my brother Trey, even though he didn’t like him very much. Revision: My cousin Jake hugged my brother Trey, even though Jake doesn’t like Trey very much.

- Jargon or technical terms that make readers work unnecessarily hard. Maybe you need to use some of these words because they are important terms in your field, but don’t throw them in just to “sound smart.” Example : The dialectical interface between neo-Platonists and anti-disestablishment Catholics offers an algorithm for deontological thought. Revision : The dialogue between neo-Platonists and certain Catholic thinkers is a model for deontological thought.

- Loaded language. Sometimes we as writers know what we mean by a certain word, but we haven’t ever spelled that out for readers. We rely too heavily on that word, perhaps repeating it often, without clarifying what we are talking about. Example : Society teaches young girls that beauty is their most important quality. In order to prevent eating disorders and other health problems, we must change society. Revision : Contemporary American popular media, like magazines and movies, teach young girls that beauty is their most important quality. In order to prevent eating disorders and other health problems, we must change the images and role models girls are offered.

Sometimes the problem isn’t choosing exactly the right word to express an idea—it’s being “wordy,” or using words that your reader may regard as “extra” or inefficient. Take a look at the following list for some examples. On the left are some phrases that use three, four, or more words where fewer will do; on the right are some shorter substitutes:

Keep an eye out for wordy constructions in your writing and see if you can replace them with more concise words or phrases.

In academic writing, it’s a good idea to limit your use of clichés. Clichés are catchy little phrases so frequently used that they have become trite, corny, or annoying. They are problematic because their overuse has diminished their impact and because they require several words where just one would do.

The main way to avoid clichés is first to recognize them and then to create shorter, fresher equivalents. Ask yourself if there is one word that means the same thing as the cliché. If there isn’t, can you use two or three words to state the idea your own way? Below you will see five common clichés, with some alternatives to their right. As a challenge, see how many alternatives you can create for the final two examples.

Try these yourself:

Writing for an academic audience

When you choose words to express your ideas, you have to think not only about what makes sense and sounds best to you, but what will make sense and sound best to your readers. Thinking about your audience and their expectations will help you make decisions about word choice.

Some writers think that academic audiences expect them to “sound smart” by using big or technical words. But the most important goal of academic writing is not to sound smart—it is to communicate an argument or information clearly and convincingly. It is true that academic writing has a certain style of its own and that you, as a student, are beginning to learn to read and write in that style. You may find yourself using words and grammatical constructions that you didn’t use in your high school writing. The danger is that if you consciously set out to “sound smart” and use words or structures that are very unfamiliar to you, you may produce sentences that your readers can’t understand.

When writing for your professors, think simplicity. Using simple words does not indicate simple thoughts. In an academic argument paper, what makes the thesis and argument sophisticated are the connections presented in simple, clear language.

Keep in mind, though, that simple and clear doesn’t necessarily mean casual. Most instructors will not be pleased if your paper looks like an instant message or an email to a friend. It’s usually best to avoid slang and colloquialisms. Take a look at this example and ask yourself how a professor would probably respond to it if it were the thesis statement of a paper: “Moulin Rouge really bit because the singing sucked and the costume colors were nasty, KWIM?”

Selecting and using key terms

When writing academic papers, it is often helpful to find key terms and use them within your paper as well as in your thesis. This section comments on the crucial difference between repetition and redundancy of terms and works through an example of using key terms in a thesis statement.

Repetition vs. redundancy

These two phenomena are not necessarily the same. Repetition can be a good thing. Sometimes we have to use our key terms several times within a paper, especially in topic sentences. Sometimes there is simply no substitute for the key terms, and selecting a weaker term as a synonym can do more harm than good. Repeating key terms emphasizes important points and signals to the reader that the argument is still being supported. This kind of repetition can give your paper cohesion and is done by conscious choice.

In contrast, if you find yourself frustrated, tiredly repeating the same nouns, verbs, or adjectives, or making the same point over and over, you are probably being redundant. In this case, you are swimming aimlessly around the same points because you have not decided what your argument really is or because you are truly fatigued and clarity escapes you. Refer to the “Strategies” section below for ideas on revising for redundancy.

Building clear thesis statements

Writing clear sentences is important throughout your writing. For the purposes of this handout, let’s focus on the thesis statement—one of the most important sentences in academic argument papers. You can apply these ideas to other sentences in your papers.

A common problem with writing good thesis statements is finding the words that best capture both the important elements and the significance of the essay’s argument. It is not always easy to condense several paragraphs or several pages into concise key terms that, when combined in one sentence, can effectively describe the argument.

However, taking the time to find the right words offers writers a significant edge. Concise and appropriate terms will help both the writer and the reader keep track of what the essay will show and how it will show it. Graders, in particular, like to see clearly stated thesis statements. (For more on thesis statements in general, please refer to our handout .)

Example : You’ve been assigned to write an essay that contrasts the river and shore scenes in Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn. You work on it for several days, producing three versions of your thesis:

Version 1 : There are many important river and shore scenes in Huckleberry Finn.

Version 2 : The contrasting river and shore scenes in Huckleberry Finn suggest a return to nature.

Version 3 : Through its contrasting river and shore scenes, Twain’s Huckleberry Finn suggests that to find the true expression of American democratic ideals, one must leave “civilized” society and go back to nature.

Let’s consider the word choice issues in these statements. In Version 1, the word “important”—like “interesting”—is both overused and vague; it suggests that the author has an opinion but gives very little indication about the framework of that opinion. As a result, your reader knows only that you’re going to talk about river and shore scenes, but not what you’re going to say. Version 2 is an improvement: the words “return to nature” give your reader a better idea where the paper is headed. On the other hand, they still do not know how this return to nature is crucial to your understanding of the novel.

Finally, you come up with Version 3, which is a stronger thesis because it offers a sophisticated argument and the key terms used to make this argument are clear. At least three key terms or concepts are evident: the contrast between river and shore scenes, a return to nature, and American democratic ideals.

By itself, a key term is merely a topic—an element of the argument but not the argument itself. The argument, then, becomes clear to the reader through the way in which you combine key terms.

Strategies for successful word choice

- Be careful when using words you are unfamiliar with. Look at how they are used in context and check their dictionary definitions.

- Be careful when using the thesaurus. Each word listed as a synonym for the word you’re looking up may have its own unique connotations or shades of meaning. Use a dictionary to be sure the synonym you are considering really fits what you are trying to say.

- Under the present conditions of our society, marriage practices generally demonstrate a high degree of homogeneity.

- In our culture, people tend to marry others who are like themselves. (Longman, p. 452)

- Before you revise for accurate and strong adjectives, make sure you are first using accurate and strong nouns and verbs. For example, if you were revising the sentence “This is a good book that tells about the Revolutionary War,” think about whether “book” and “tells” are as strong as they could be before you worry about “good.” (A stronger sentence might read “The novel describes the experiences of a soldier during the Revolutionary War.” “Novel” tells us what kind of book it is, and “describes” tells us more about how the book communicates information.)

- Try the slash/option technique, which is like brainstorming as you write. When you get stuck, write out two or more choices for a questionable word or a confusing sentence, e.g., “questionable/inaccurate/vague/inappropriate.” Pick the word that best indicates your meaning or combine different terms to say what you mean.

- Look for repetition. When you find it, decide if it is “good” repetition (using key terms that are crucial and helpful to meaning) or “bad” repetition (redundancy or laziness in reusing words).

- Write your thesis in five different ways. Make five different versions of your thesis sentence. Compose five sentences that express your argument. Try to come up with four alternatives to the thesis sentence you’ve already written. Find five possible ways to communicate your argument in one sentence to your reader. (We’ve just used this technique—which of the last five sentences do you prefer?)Whenever we write a sentence we make choices. Some are less obvious than others, so that it can often feel like we’ve written the sentence the only way we know how. By writing out five different versions of your thesis, you can begin to see your range of choices. The final version may be a combination of phrasings and words from all five versions, or the one version that says it best. By literally spelling out some possibilities for yourself, you will be able to make better decisions.

- Read your paper out loud and at… a… slow… pace. You can do this alone or with a friend, roommate, TA, etc. When read out loud, your written words should make sense to both you and other listeners. If a sentence seems confusing, rewrite it to make the meaning clear.

- Instead of reading the paper itself, put it down and just talk through your argument as concisely as you can. If your listener quickly and easily comprehends your essay’s main point and significance, you should then make sure that your written words are as clear as your oral presentation was. If, on the other hand, your listener keeps asking for clarification, you will need to work on finding the right terms for your essay. If you do this in exchange with a friend or classmate, rest assured that whether you are the talker or the listener, your articulation skills will develop.

- Have someone not familiar with the issue read the paper and point out words or sentences they find confusing. Do not brush off this reader’s confusion by assuming they simply doesn’t know enough about the topic. Instead, rewrite the sentences so that your “outsider” reader can follow along at all times.

- Check out the Writing Center’s handouts on style , passive voice , and proofreading for more tips.

Questions to ask yourself

- Am I sure what each word I use really means? Am I positive, or should I look it up?

- Have I found the best word or just settled for the most obvious, or the easiest, one?

- Am I trying too hard to impress my reader?

- What’s the easiest way to write this sentence? (Sometimes it helps to answer this question by trying it out loud. How would you say it to someone?)

- What are the key terms of my argument?

- Can I outline out my argument using only these key terms? What others do I need? Which do I not need?

- Have I created my own terms, or have I simply borrowed what looked like key ones from the assignment? If I’ve borrowed the terms, can I find better ones in my own vocabulary, the texts, my notes, the dictionary, or the thesaurus to make myself clearer?

- Are my key terms too specific? (Do they cover the entire range of my argument?) Can I think of specific examples from my sources that fall under the key term?

- Are my key terms too vague? (Do they cover more than the range of my argument?)

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Cook, Claire Kehrwald. 1985. Line by Line: How to Improve Your Own Writing . Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Grossman, Ellie. 1997. The Grammatically Correct Handbook: A Lively and Unorthodox Review of Common English for the Linguistically Challenged . New York: Hyperion.

Houghton Mifflin. 1996. The American Heritage Book of English Usage: A Practical and Authoritative Guide to Contemporary English . Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

O’Conner, Patricia. 2010. Woe Is I: The Grammarphobe’s Guide to Better English in Plain English , 3rd ed. New York: Penguin Publishing Group.

Tarshis, Barry. 1998. How to Be Your Own Best Editor: The Toolkit for Everyone Who Writes . New York: Three Rivers Press.

Williams, Joseph, and Joseph Bizup. 2017. Style: Lessons in Clarity and Grace , 12th ed. Boston: Pearson.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Understand the importance of word choice in writing with these tips, including a word choice definition, resources, and examples.

Word choice is critical to your writing. Get tips on selecting the right words to communicate your message, meaning, and tone.

Words have power—they can evoke emotion, make a reader care, create vivid literary imagery, and bring stories and characters to life. Word choice depends on many factors such as your intended audience, genre, tone, and subject matter.

In writing, diction is the strategic choice of words based on the audience, context, or situation. It can… Use this guide to learn everything you need to know about diction including the definition of diction and 9 different types, with examples.

This handout can help you revise your papers for word-level clarity, eliminate wordiness and avoid clichés, find the words that best express your ideas, and choose words that suit an academic audience.

As a creative writer, your word choices hold the power to shape narratives, build worlds, and influence the minds of your readers. However, what truly defines the impact of the words we choose?...