- Open access

- Published: 08 April 2024

Patient satisfaction with preoperative nursing care and its associated factors in surgical procedures, 2023: a cross-sectional study

- Bizuayehu Atinafu Ataro 1 ,

- Temesgen Geta 2 ,

- Eshetu Elfios Endirias 1 ,

- Christian Kebede Gadabo 3 &

- Getachew Nigussie Bolado 1

BMC Nursing volume 23 , Article number: 235 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

359 Accesses

Metrics details

To enhance patient satisfaction, nurses engaged in preoperative care must possess a comprehensive understanding of the most up-to-date evidence. However, there is a notable dearth of relevant information regarding the current status of preoperative care satisfaction and its impact, despite a significant rise in the number of patients seeking surgical intervention with complex medical requirements.

To assess patient satisfaction with preoperative nursing care and its associated factors in surgical procedures of, 2023.

A cross-sectional study was conducted, and the data was collected from the randomly selected 468 patients who had undergone surgery during the study period. The collected data was entered into Epidata version 3.1 and analyzed using SPSS version 25 software.

The complete participation and response of 468 participants resulted in a response rate of 100%. Overall patient satisfaction with preoperative nursing care was 79.5%. Sex (Adjusted odds ratio (AOR): 1.14 (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.21–2.91)), payment status for treatment (AOR: 1.45 (95% CI: 0.66–2.97)), preoperative fear and anxiety (AOR: 1.01, 95% CI: 0.49–2.13)), patient expectations (AOR: 3.39, 95% CI: 2.17–7.11)), and preoperative education (AOR: 1.148, 95% CI: 0.54–2.86)) exhibited significant associations with patient satisfaction with preoperative nursing care.

It is important to exercise caution when interpreting the level of preoperative nursing care satisfaction in this study. The significance of preoperative nursing care satisfaction lies in its reflection of healthcare quality, as even minor deficiencies in preoperative care can potentially lead to life-threatening complications, including mortality. Therefore, prioritizing the improvement of healthcare quality is essential to enhance patient satisfaction.

Peer Review reports

Preoperative care encompasses the provisions given prior to surgery, wherein the patient’s unique requirements are considered to undertake physical and psychological preparations in anticipation of the procedure [ 1 ]. This phase commences upon the patient’s admission to the hospital or surgical facility and extends until the commencement of the actual procedure [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ]. The primary emphasis in preoperative preparation should lie in the advancement of techniques aimed at mitigating the emotional distress experienced by surgical patients [ 5 ]. In this context, nurses play a crucial role in formulating, developing, expanding, and implementing interventions and modifications [ 5 , 6 ].

The primary goal of a healthcare system is to ensure the provision of medical care that is of the utmost quality and safety [ 7 ]. In this context, patient safety has emerged as a paramount concern and is currently placed at the forefront of priorities [ 8 , 9 ]. A systematic review conducted in Saudi Arabia and Turkey concluded that preoperative nursing assessment plays a vital role in mitigating preoperative complications by alleviating anxiety and enhancing patients’ understanding of the surgical procedure. This, in turn, has a substantial positive impact on patient satisfaction [ 10 , 11 ]. The review also emphasized the necessity of nurses receiving proper training and education in preoperative assessment, as the absence of adequately trained nursing staff elevates patient anxiety levels and renders them susceptible to potential complications [ 2 , 10 ].

Patient satisfaction is defined as a subjective reaction to the context, process, and result of the service experience one has received [ 12 , 13 ]. The measurement of quality is closely linked to the satisfaction levels expressed by patients regarding the care they have received [ 14 , 15 ]. Both the practice environment and the personal characteristics of nurses serve as significant indicators of the quality of patient care [ 16 ]. Enhancing working conditions and achieving improved patient outcomes, including reduced mortality rates, are facilitated by a positive relationship between the work environment attributes of nurses and their levels of proficiency and personal capabilities [ 17 ]. Additionally, various aspects of the workplace, such as the physical setting, working hours, and the level of fatigue among nursing staff, have been found to influence the safety and quality of patient care [ 18 ].

Comprehensive nursing interventions should be implemented throughout the entire perioperative phase to prevent complications and adverse events in the surgical domain [ 19 ]. Although the impact of perioperative nursing interventions on patient health outcomes may not be fully comprehended, it is substantial in its significance [ 20 ]. Through the provision of care during the postoperative period, nurses can effectively mitigate the occurrence of adverse events, even though certain studies have identified nurses’ workload and time constraints as predominant barriers to effective nurse-patient communication [ 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 ]. Preoperative nursing assessment plays a pivotal role in delineating and discerning the patient’s risk factors throughout their perioperative care, extending beyond the confines of the surgical procedure itself [ 25 , 26 ].

To optimize patient care and enhance postoperative outcomes, it is imperative for nurses engaged in patient assessment and preoperative care to possess comprehensive knowledge and understanding of the latest research in this field [ 27 ]. Throughout the preoperative phase, nurses provided comfort, guidance, and rehabilitation to the patients. However, they failed to involve the patients in their treatment [ 28 , 29 ]. An unfortunate number of patients endured minor injuries due to improper utilization of theater equipment, such as diathermy devices, along with inadequate implementation of safety precautions by the nursing staff during the surgical procedure [ 28 , 30 ]. Furthermore, patients were left feeling bewildered and unsettled due to the nurses’ deficient communication [ 28 , 31 ].

The perioperative environment possesses distinctive characteristics, encompassing intricate clinical care delivered by specialized teams, substantial costs, utilization of advanced technologies, and a vast array of challenging-to-manage resources [ 30 , 32 ]. These factors can contribute to the development of highly intricate settings prone to adverse events concerning patient safety [ 32 , 33 ]. Medication errors, omissions, patient misidentification, and surgical site misidentification are among the various types of mistakes that can occur during surgical procedures [ 34 ]. Birmingham-based research showcased that reducing waiting times, enhancing patient satisfaction, and upholding the efficacy of clinical services were the outcomes of evaluating patient load and the delivery system within the clinic [ 35 , 36 ]. To optimize patient satisfaction, nurses involved in preoperative care must possess up-to-date knowledge and understanding of the most recent research [ 27 ]. Despite the significant increase in the number of patients requiring surgery, with complex medical needs, a scarcity of pertinent data exists regarding the satisfaction levels and impacts associated with preoperative care.

Studies conducted in Ethiopia showed varying levels of patient satisfaction with preoperative nursing care in surgical procedures. The cross-sectional study carried out in Addis Ababa, Western Amhara referral hospitals, University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, East Amhara referral hospitals and Gamo and Gofa zone showed that the patient satisfaction with preoperative care ranges from 36.6 to 84% [ 12 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 ]. According to the study conducted at Sohag University, the overall satisfaction score of patients who underwent surgery was determined to be 61.9% [ 41 ].

Various factors play key roles in influencing patient satisfaction with preoperative nursing care, both related to the hospital and nursing environment (such as ward/unit dynamics, length of hospitalization, surgical specialization, waiting times, nurse responsiveness), patient and family characteristics (including financial status, prior hospitalizations, service expectations, health conditions, procedure types, complications, discharge plans, anxiety levels, illness duration, family size), and preoperative education can seriously influence satisfaction levels of patients with preoperative nursing care. Additionally, sociodemographic factors like gender, age, income, residence, marital status, religion, ethnicity, education level, and occupation may also significantly impact patient satisfaction [ 1 , 10 , 12 , 32 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 ].

Enhancing patient satisfaction with preoperative nursing care is vital for patient-centered healthcare. This study investigates the factors influencing patient satisfaction in surgical procedures, aiming to improve care quality. By identifying areas for enhancement, the research informs healthcare practices, potentially leading to better patient experiences and outcomes. Contributing to the existing literature, this contemporary study provides updated insights into patient preferences, guiding efforts toward optimized preoperative care delivery and improved surgical outcomes. This research can also pave the way for advancements in patient-centered care approaches and potentially lead to positive impacts on healthcare outcomes and patient experiences in surgical settings.

Most of the previous research conducted in Ethiopia has primarily focused on evaluating patient satisfaction with the overall hospital services. However, this particular study honed in on specifically examining the satisfaction levels of preoperative nursing care services. This focus was chosen due to the profound impact that such care has on surgical outcomes and subsequent postoperative recovery. Notably, this study stands as the first of its kind within our study area; as far as we know, no prior study of this nature has been conducted. It is also worth noting that while some previous studies had utilized nurses as study participants, this study appropriately selected patients, as they possess indispensable insights into the quality of nursing care and ultimately determine the level of satisfaction experienced. Additionally, this study introduced previously unstudied variables, such as patient flow per shift and nurses’ willingness to listen and respond to questions, which hold the potential for significant associations with satisfaction levels regarding preoperative nursing care services. Therefore, this study aimed to comprehensively assess patient satisfaction with preoperative nursing care and its associated factors in surgical procedures.

Methods and materials

Study area and period.

This study was carried out in the Wolaita Zone, located 329 km away from Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia. Currently, Wolaita Sodo serves as the capital city of southern Ethiopia. Known for its high population density, the zone boasts 290 individuals per square kilometer, making it one of the most densely populated regions in the country. According to the 2021 population projection by the Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia, the Wolaita Zone is home to a total population of 6,142,063 people residing within an area of 4,208.64 square kilometers (1,624.96 sq. mi). Within this zone, there are nine public hospitals, with Wolaita Sodo University Comprehensive Specialized Hospital being the sole specialized healthcare facility. The hospital provides a broad range of surgical services spanning multiple departments, including general surgery, orthopedic surgery, urologic surgery, obstetrics and gynecologic surgery, and maxillofacial surgery. The study was conducted from July 15 to July 30, 2023.

Study design:

Facility-based cross-sectional study was employed because it allows for the exploration of relationships between variables at a specific moment, providing valuable insights into the prevalence of patient satisfaction and associated factors concurrently.

Populations

Source population:.

All surgical patients who have undergone surgery.

The study sample:

All surgical patients that are available during a study period.

Eligibility

Inclusion criteria:.

All adult patients aged ≥ 18 years who have undergone surgery and have been admitted to a surgical, obstetrics/gynecology ward, ophthalmic, orthopedic, or other department were included.

Exclusion criteria:

Patients who sought treatment as outpatients, individuals who were severely ill and unconscious, as well as patients with known mental health issues, were excluded from the study.

Sample size determination and procedure

The sample size was determined using a formula for a single population proportion, taking into account the following assumptions: a prevalence of 52.75% for patient satisfaction with nursing care in Eastern Ethiopia [ 25 ], a confidence level of 95%, a margin of error of 5%, a nonresponse rate of 10% as follows:

n- The minimum sample size required.

P- Prevalence of satisfaction with preoperative nursing care.

d- Margin of error.

Z 𝛼 /2- Standard normal distribution at 95% confidence level

After accounting for a 10% contingency for potential non-response, the final sample size for this study amounted to 468 subjects.

Study variables

Dependent variable:.

Patients’ satisfaction.

Independent variables:

Sociodemographic variables (sex, age, monthly income, residence, marital status, religion, ethnicity, educational, occupational status); Hospital and nurse-related variables (ward/unit, length of hospital stay, surgical specialty, surgery waiting time, patient flow per shift, nurses’ willingness to listen and respond to questions); Patient and family factors (payment status, previous admission, patient service expectations, co-morbidity, surgery type, complications, discharge destination, preoperative fear and anxiety, duration of the illness, family size), and Preoperative education.

Data collection tools and procedures

The data was collected through a meticulously tested, structured, interview-administered questionnaire originally written in English and then translated into the local language, Wolaitigna, to ensure accessibility and accurate comprehension among the participants. The questionnaire was divided into six sections and was obtained from previous studies conducted in Ethiopia and other locations internationally [ 12 , 13 , 31 , 39 ]. The first part of the questionnaire contains the sociodemographic characteristics of the patients. The second part contains institution- or health facility-related variables affecting patients’ preoperative nursing care services. Items in the third and fourth sections assessed the nurse-related factors and patient- and family-related variables influencing patients’ preoperative nursing care services, respectively. One of the patient-related factors was preoperative fear and anxiety and it was measured by tools adapted from previous studies conducted in Ethiopia and Iraq [ 43 , 44 ]. The fifth part of the question contains items used to measure preoperative education containing 16 questions [ 12 ]. The final part contains items to measure the level of preoperative nursing care satisfaction among nurses. The instruments utilized to assess patient satisfaction with preoperative nursing care comprised a set of 22 Likert-scale questions. Each question was rated on a scale from 1, indicating “very unsatisfied,” to 5, indicating “very satisfied”. This tool was valid in Ethiopia and had internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.96. The overall patient satisfaction with preoperative nursing care in surgical procedures was classified into two categories: satisfied and unsatisfied [ 12 , 31 , 37 ].. A team of four nursing professionals who held BSc degrees was specifically assigned to take on the role of data collectors. They were closely supervised by two BSc-qualified nurse professionals throughout the study, who were selected from Sodo Health Center.

Data processing and analysis

The collected data were cleaned, coded, and entered using Epidata software and exported into Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 26 to facilitate analysis. To explore the relationship between the dependent and independent variables, both bivariable and multivariable logistic regression techniques were utilized. In the bivariable logistic regression model, all independent variables with a p-value less than 0.25 were subsequently entered into the multivariable logistic regression model. The evaluation of significance relied on the adjusted odds ratio (AOR), accompanied by a 95% confidence interval (CI) and a p-value less than 0.05, allowing for meaningful interpretation of the obtained associations. Descriptive statistics, such as tables, graphs, frequencies, and percentages, were employed to provide an overview of the characteristics observed within the sample.

Data quality control

A preliminary assessment, commonly referred to as a pilot study, of the questionnaire, took place at Grace Primary Hospital, which lies outside the scope of the target hospitals. This pre-test was conducted on a subset of the sample size, comprising 5%, a week before the commencement of the actual data collection period. Based on the outcomes of the pre-test, necessary modifications were made to address issues such as unclear questions, typographical errors, and ambiguous wording. Furthermore, the reliability of the Likert-scale items was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, yielding a coefficient of 0.82. To ensure proficient data collection, a comprehensive one-day training session was provided to the data collectors, encompassing instructions on both the data collection tool and the collection process itself. The principal investigator oversaw the data collection process and monitored its completeness, accuracy, and consistency daily. To enhance data integrity, a double-entry method was employed, involving two separate data clerks who independently entered the collected data into SPSS. The consistency of the entered data was cross-verified by comparing the two versions of the data to identify any discrepancies.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants

The response rate for this study was an impressive 100%. Out of the total of 468 respondents, the majority were female (55.1%), and the mean age of the participants was 34 years with a standard deviation of 8.9. Notably, a significant proportion (21.6%) fell within the age bracket of 25 to 34 years. Among the respondents, 210 (44.9%) resided in urban areas, while 258 (55.1%) hailed from rural regions. Regarding marital status, the majority (68.6%) were married, and adherents of the Protestant faith constituted more than 50% of the participants. Approximately 60% of the respondents were illiterate, and 138 (29.5%) identified themselves as farmers. Furthermore, 131 (28.0%) were engaged in the role of housewives, and 107 (22.9%) were students. Out of the total 468 respondents, 223 (47.6%) reported earning less than 1000 ETB per month (Table 1 ).

Patient satisfaction with preoperative nursing care

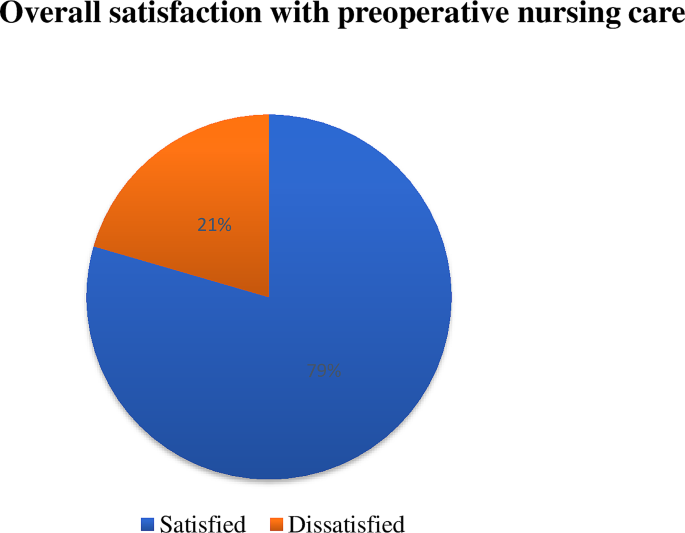

The overall satisfaction with preoperative nursing care among patients who have undergone surgical procedures at Wolaita Sodo University Comprehensive Specialized Hospital was 79.5% (75.4–83.6) (Fig. 1 ).

Patient satisfaction with preoperative nursing care in surgical procedures at Wolaita Sodo University Comprehensive Specialized Hospital

Variables influencing patient satisfaction with preoperative nursing care

Hospital and nurse-related variables.

Among the participants, a substantial majority (84.8%) were admitted to the surgical unit of the hospital, highlighting the prevalence of surgical cases in the study sample. In terms of the duration of hospital stay, 289 (61.8%) reported a stay of less than seven days, indicating relatively shorter periods of hospitalization. When it came to interactions with surgeons, the participants disclosed that 151 (32.2%) had contact with surgeons specializing in general surgery, while 129 (27.6%) had contact with surgeons specializing in traumatology. Regarding the waiting time for surgery, more than half of the participants (53.2%) indicated a waiting period of less than one month. Moreover, a majority of the participants (55.3%) acknowledged that there was a high number of patient or a high patient flow during their waiting period, suggesting the burden on the healthcare system. Disturbingly, 277 (59.2%) of the participants reported dissatisfaction with the nurses’ willingness to listen and respond to their concerns, indicating poor communication and responsiveness on the part of the nursing staff (Table 2 ).

Patient and family variables

Among the respondents who participated in this study, a significant proportion (61.3%) revealed that they had fewer than three family members, while 148 (31.6%) reported having four to six family members. More than half of the participants (53.4%) reported receiving free-of-charge treatment from the hospital, indicating a reliance on the hospital’s financial support. Additionally, a considerable number of respondents (63.7%) recalled previous admissions for various health issues. Similarly, 171 (63.5%) of the patients reported having co-morbidities during their initial diagnosis, further complicating their healthcare journey. A substantial proportion of the participants (83.3%) experienced complications related to their current surgery, with pain being the most prevalent complication, affecting 324 (83.1%) of those experiencing complications. The majority of the participants (40.2%) reported that their illness had persisted for several days before undergoing surgery. Abdominal surgery was the most common surgical procedure among the participants, accounting for 119 (25.4%) cases. As for the anticipated discharge destination, 301 (64.3%) participants stated that they would be returning home upon discharge, emphasizing the preference for familiar surroundings. Unsurprisingly, preoperative fear and anxiety were prevalent among the participants, with 373 (79.9%) reporting experiencing high fear and anxiety. Moreover, a significant majority (78.6%) had high service expectations from the hospital, indicating the importance of quality care and support during the preoperative period (Table 3 ).

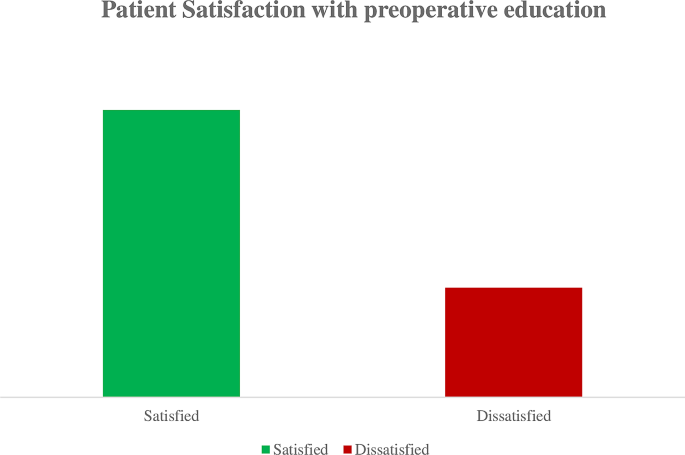

Patient satisfaction with preoperative education

The overall patient satisfaction with preoperative education on surgical procedures was 79.5% (Fig. 2 ).

Overall patient satisfaction with preoperative education on surgical procedures at Wolaita Sodo University Comprehensive Specialized Hospital

Factors associated with satisfaction with preoperative nursing care

Sex, age, educational status, monthly income, length of hospital stays, surgery waiting time, nurses’ willingness to listen and respond, payment status for treatment, complications, duration of illness, preoperative fear and anxiety, patient expectations, and preoperative education were all evaluated as potential factors in the bivariable logistic regression analysis (p < 0.25) to determine their association with patient satisfaction with preoperative nursing care. In the multivariable logistic regression, it was found that sex, payment status for treatment, preoperative fear and anxiety, patient expectations, and preoperative education exhibited significant associations with patient satisfaction with preoperative nursing care (p < 0.05). Male patients were found to be 1.14 times more likely to report satisfaction with preoperative nursing care compared to female patients (AOR: 1.14 (95% CI: 0.21–2.91)). Patients who received free treatment were found to be 1.45 times more likely to express satisfaction with preoperative nursing care compared to those who had to pay for their treatment (AOR: 1.45 (95% CI: 0.66–2.97)). Participants who did not experience preoperative fear and anxiety were found to be 1.01 times more likely to report satisfaction with preoperative nursing care compared to those who did have preoperative fear and anxiety (AOR: 1.01, 95% CI: 0.49–2.13). Patients who had low expectations of hospital services were found to be 3.39 times more likely to express satisfaction with preoperative nursing care compared to those who had high service expectations from the hospital (AOR: 3.39, 95% CI: 2.17–7.11). Participants who received preoperative education from nurses were 1.15 times more likely to be satisfied with preoperative nursing care compared to those who did not receive such education from nurses (AOR: 1.148, 95% CI: 0.54–2.86) (Table 4 ).

The primary objective of this study was to determine the level of patient satisfaction with preoperative nursing care at Wolaita Sodo University Comprehensive Specialized Hospital. Furthermore, the study sought to identify factors significantly associated with patient satisfaction with preoperative nursing care. Consequently, the findings of this study demonstrated that the level of patient satisfaction with perioperative nursing care was 79.5%.

This finding was lower when compared with the previous studies conducted at the University of Gondar Teaching Hospital (98.1%) [ 31 ] and Public hospitals in Addis Ababa (84%) [ 12 ]. This disparity can potentially be attributed to various factors, including differences in patient variables such as sociodemographic characteristics, variations in hospital settings, potential inadequacies in the provision of preoperative education and care within the hospitals examined in this study, an increased influx of patients, heightened health-seeking behaviors among individuals, as well as elevated patient expectations regarding the quality of services rendered by the hospitals.

Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that the current finding exhibited a higher level of satisfaction when compared with previous studies conducted at Sohag University (61.9%) [ 41 ], Western Amhara referral hospitals (68.7%) [ 37 ], Gondar University Comprehensive Specialized Hospital (74%) [ 39 ], East Amhara referral hospitals (38.5%) [ 40 ], and Gamo and Gofa zones (36.6%) [ 38 ]. This discrepancy could potentially be attributed to various factors such as differences in the time gaps between the studies, variations in the study participants (for example, the study in East Amhara referral hospitals focused on nurses instead of patients), discrepancies in the services assessed (for instance, the study in the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital solely evaluated satisfaction related to anesthesia services), as well as variances in the perception of the services provided by the patients themselves and the methodologies employed in the studies.

The sex of the patient was significantly associated with patient satisfaction with preoperative nursing care. Male patients were found to be 1.14 times more likely to report satisfaction with preoperative nursing care compared to female patients. This was in line with the study conducted in Barcelona, Spain, [ 13 ] which, strengthens that men patients were more satisfied with preoperative nursing care than women. This finding may be attributed to the fact that women reported experiencing more challenges with hospital care when compared to men. This disparity could potentially arise from the fact that female patients place greater emphasis on their health and often assume the role of evaluators and even administrators of care practices, not just for themselves but also for other family members [ 22 ].

Similarly, payment status for treatment had a significant association with patient satisfaction with preoperative nursing care. Patients who received free treatment were found to be 1.45 times more likely to express satisfaction with preoperative nursing care compared to those who had to pay for their treatment. This could be because patients who receive treatment for free may view it as a gesture of kindness or support, which can enhance their overall experience and level of satisfaction with the preoperative care they receive. Furthermore, patients who do not have to pay for their medical needs may feel less stressed and anxious about the expense, which frees them up to concentrate more on the quality of nursing care they receive. Furthermore, patients who receive free treatment could feel appreciative of the hospital or healthcare system, which could affect how they feel about the care they receive and raise their satisfaction levels.

In this study, patients with preoperative fear and anxiety had also a significant association with satisfaction with preoperative nursing care. Patients who did not experience preoperative fear and anxiety were found to be 1.01 times more likely to report satisfaction with preoperative nursing care compared to those who did have preoperative fear and anxiety. A similar finding was reported in the study conducted in public hospitals in Addis Ababa [ 12 ]. This could be because patients who approach their surgery feeling emotionally stable and at ease may be more receptive to the nursing care they receive. Their ability to maintain composure and relaxation may have a favorable impact on how they view the nursing care they receive, increasing their level of satisfaction. Additionally, patients who do not experience worry or panic before surgery could be better able to express their needs and concerns to the nursing staff. They will be more satisfied as a consequence of this excellent communication, which can improve the standard of care and support they receive. Furthermore, people who are not experiencing preoperative worry or fear may have a more upbeat and hopeful view. This optimistic outlook may lead to a more favorable perception.

Patient expectation of the services was also significantly associated with satisfaction with preoperative nursing care. Participants who had low expectations of hospital services were found to be 3.39 times more likely to express satisfaction with preoperative nursing care compared to those who had high service expectations from the hospital. The possible explanation for this could be that patients who have modest expectations may possess a more pragmatic understanding of the limitations and complexities inherent in the healthcare system. As a consequence, they may display greater gratitude towards the care and attention delivered by the nursing staff, even if it falls short of their initial expectations. Conversely, patients with high service expectations might establish unattainable standards or possess excessively demanding criteria. Consequently, if their expectations are not met, they may experience a sense of disappointment or dissatisfaction with the preoperative nursing care, even if it is of exemplary quality. In contrast, individuals with lower expectations are more likely to find the care they receive to be satisfactory, even if it does not reach the lofty heights of their anticipations.

Likewise, preoperative education was significantly associated with satisfaction with preoperative nursing care. Participants who received preoperative education from nurses were 1.15 times more likely to be satisfied with preoperative nursing care compared to those who did not receive such education from nurses. This finding was similar to the finding of the study conducted at the University of Gondar referral hospital and public hospitals in Addis Ababa [ 12 , 31 ]. The possible reason for this might be that patients who receive preoperative education from nurses are better prepared for surgery by having knowledge and comprehension of the procedures and expectations surrounding their experience. They feel less nervous and uncertain as a result of this instruction, which may improve how they see the nursing care they get. Preoperative education also increases the likelihood that participants will feel powerful and engaged in their care. They can be more engaged in their healing process and may comprehend the significance of specific nursing interventions. A greater sense of participation and teamwork with the nursing staff may be a factor in increased satisfaction [ 12 ].

This study’s results were flavored by Kolcaba’s Comfort Theory, which centers on improving patient satisfaction through attending to their comfort requirements. The study showed that aspects aligning with the theory’s relief component can be improved by meeting particular comfort needs to alleviate pain or discomfort. Additionally, the maintenance of the ease component can be achieved through proactive measures to prevent discomfort to prevent known risk factors that would keep a patient from feeling comfortable, while fulfillment of the transcendence component involves providing patients experiencing physical or emotional discomfort with peace, significance, or opportunities for personal growth through preoperative education and creating a positive nurse-patient relationship through the lens of communication, trust, and empathy in preoperative care.

Implication of the study

In the context of nursing practice, the findings of this study can help nurses in practice by illuminating the variables influencing patients’ satisfaction with preoperative nursing care. Nurses can create tailored methods of care delivery that improve patient experiences and satisfaction by having a greater understanding of the effects of variables including patient gender, treatment costs, preoperative anxiety, and service expectations. Regarding nursing education, the study emphasizes how crucial it is to include preoperative education and communication skills in nursing curricula. It emphasizes how important it is to give nurses the skills and information they need to properly counsel and assist patients before surgery, allaying their anxieties, controlling expectations, and encouraging favorable patient outcomes. The study establishes the foundation for future research endeavors aimed at delving deeper into the topic of patient satisfaction with preoperative nursing treatment. Additional factors that might affect satisfaction, the efficacy of certain interventions or educational initiatives, and the long-term effects of preoperative nursing care on patient outcomes are all potential areas for further research. This information can support evidence-based procedures and guidelines meant to enhance patients’ overall surgical experiences.

Conclusion and recommendation

The study revealed patient satisfaction with preoperative nursing care was high, even though there is room for improvement to ensure optimal healthcare quality. Preoperative care satisfaction is a critical indicator, as even slight deficiencies in this area can have severe consequences, including fatal outcomes. Factors significantly associated with satisfaction in preoperative nursing care were sex, payment status for treatment, preoperative fear and anxiety, patient expectations, and preoperative education.

To address these findings, hospital managers and health policymakers must develop comprehensive strategies aimed at enhancing satisfaction with preoperative nursing care. Initiatives could involve the implementation of tailored training programs for nurses in collaboration with the Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health, regional health bureaus, and non-governmental organizations. These programs should prioritize equipping nurses with the necessary skills and knowledge to deliver high-quality preoperative care. It is essential to emphasize the need for further research to fully comprehend the specific factors and their impact on patient satisfaction with preoperative nursing care. This research would contribute to a deeper understanding of how nurses can enhance satisfaction levels, ultimately informing the development of evidence-based practices and policies in this crucial healthcare domain.

Strength of the study

To enhance the representativeness and generalizability of our study findings, we employed a substantial sample size and incorporated variables that were overlooked in the previous literature. This approach contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing satisfaction with preoperative nursing care and ensures that our findings encompass a wider range of variables, thereby increasing the validity and applicability of the study results.

Limitations of the study

It is important to acknowledge that the cross-sectional nature of our study design only allows us to establish associations and correlations between the dependent and independent variables, rather than establishing a cause-and-effect relationship. Furthermore, as the quantitative data were collected through a self-administered questionnaire, there is a possibility of response bias from the respondents, which could introduce some limitations to the validity of the data.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Adjusted Odds Ratio

Confidence Interval

Crude Odds Ratio

Obstetrics and Gynecology

Statistical Package for Social Sciences

Makau PM, Mbithi BW, J.J.A.J.o.H S, Odero. Factors affecting compliance to preoperative patient care guidelines among nurses working in surgical wards of a tertiary referral hospital in Nairobi, Kenya. 2023. 36(2): p. 124–30 https://doi.org/10.4314/ajhs.v36i2.4 .

Turunen E et al. An integrative review of a preoperative nursing care structure. 2017. 26(7–8): p. 915–930 https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13448 .

Soydaş Yeşilyurt D, Yildiz Findik Ü. Effect of preoperative video information on anxiety and satisfaction in patients undergoing abdominal surgery. 2019. 37(8): p. 430–6 https://doi.org/10.1097/cin.0000000000000505 https://journals.lww.com/cinjournal/fulltext/2019/08000/effect_of_preoperative_video_information_on.7.aspx .

Mulugeta H et al. Patient satisfaction with nursing care in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. 2019. 18: p. 1–12 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-019-0348-9 .

Dos Santos MMB, Martins JCA, L.M.N.J.R.d.E R, Oliveira. Anxiety, depression and stress in the preoperative period of surgical patients. 2014. 4(3): p. 7–15 https://doi.org/10.12707/RIII1393 .

Health F. Continuous Health Care Quality Improvement through Knowledge Management. Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health, 2019: p. 5 https://www.healthynewbornnetwork.org/resource/continuous-health-care-quality-improvement-through-knowledge-management-in-ethiopia/ .

Van der Voorden M, Ahaus K. and A.J.B.o. Franx, explaining the negative effects of patient participation in patient safety: an exploratory qualitative study in an academic tertiary healthcare centre in the Netherlands. 2023. 13(1): p. e063175 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-063175 .

Gómara AOJEc. The occurrence of adverse events potentially attributable to nursing care in hospital units. 2014. 24(6): p. 356–7 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enfcli.2014.08.001 .

Heslop L, Lu S. and X.J.J.o.a.n. Xu, nursing-sensitive indicators: a concept analysis. 2014. 70(11): p. 2469–82 https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12503 .

Almalki ATA et al. Effectiveness of preoperative nursing assessments in reducing Preoperative complications across Saudi Arabia; a Sysetmatic Review based study. 2023. 30(17): p. 973–83 https://doi.org/10.53555/jptcp.v30i17.2667 .

Oner B et al. Nursing-sensitive indicators for nursing care: a systematic review (1997–2017). 2021. 8(3): p. 1005–22 https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.654 .

Deressa D et al. Satisfaction with preoperative education and surgical services among adults elective surgical patients at selected public hospitals in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. 2022. 10: p. 20503121221143219 https://doi.org/10.1177/20503121221143219 .

Sillero Sillero A. and A.J.S.o.m. Zabalegui, satisfaction of surgical patients with perioperative nursing care in a Spanish tertiary care hospital. 2018. 6: p. 2050312118818304 https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312118818304 .

Lake ET et al. Missed nursing care is linked to patient satisfaction: a cross-sectional study of US hospitals. 2016. 25(7): p. 535–43 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2015-003961 .

Lake ET et al. Higher quality of care and patient safety associated with better NICU work environments. 2016. 31(1): p. 24–32 https://doi.org/10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000146 .

Stimpfel AW et al. Common predictors of nurse-reported quality of care and patient safety. 2019. 44(1): p. 57–66 https://doi.org/10.1097/HMR.0000000000000155 .

Hill B. J.B.J.o.N., do nurse staffing levels affect patient mortality in acute secondary care? 2017. 26(12): p. 698–704 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2017.26.12.698 .

Van Bogaert P, et al. Nurse work engagement impacts job outcome and nurse-assessed quality of care: model testing with nurse practice environment and nurse work characteristics as predictors. 5. 2014;p(1261). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01261 .

Arakelian E et al. The meaning of person-centred care in the perioperative nursing context from the patient’s perspective–an integrative review. 2017. 26(17–18): p. 2527–44 https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13639 .

Ball JE et al. Post-operative mortality, missed care and nurse staffing in nine countries: a cross-sectional study. 2018. 78: p. 10–5 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.08.004 .

Wune G et al. Nurses to patients communication and barriers perceived by nurses at Tikur Anbessa Specilized Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia., 2018. 2020. 12: p. 100197 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijans.2020.100197 .

Sillero-Sillero A. and A.J.R.l.-a.d.e. Zabalegui, Safety and satisfaction of patients with nurse’s care in the perioperative. 2019. 27 https://doi.org/10.1590/1518-8345.2646.3142 .

Gonçalves MAR, Cerejo MdNR, J.C.A.J.R.d.E R, Martins. The influence of the information provided by nurses on preoperative anxiety. 2017. 4(14): p. 17–25 https://doi.org/10.12707/RIV17023 .

Alvarado LE, Bretones FD, J.A.J.F.i P, Rodríguez. The effort-reward model and its effect on burnout among nurses in Ecuador. 2021. 12: p. 760570 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.760570 .

Ahmed T et al. Levels of adult patients’ satisfaction with nursing care in selected public hospitals in Ethiopia. 2014. 8(4): p. 371 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4350891/ .

Malley A et al. The role of the nurse and the preoperative assessment in patient transitions. 2015. 102(2): p. 181. e1-181. e9 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aorn.2015.06.004 .

Liddle CJNS. An overview of the principles of preoperative care. 2018. 33(6) https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.2018.e11170 .

Adugbire BA, Aziato L, F.J.I.J.o.A NS, Dedey. Patients’ experiences of pre and intra operative nursing care in Ghana: A qualitative study. 2017. 6: p. 45–51 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijans.2017.04.001 .

Sadia H et al. Assessment of nurses’ knowledge and practices regarding prevention of surgical site infection. 2017. 3(6): p. 585–95 https://doi.org/10.21276/sjmps .

Fetene MB et al. Perioperative patient satisfaction and its predictors following surgery and anesthesia services in North Shewa, Ethiopia. A multicenter prospective cross-sectional study. 2022. 76: p. 103478 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2022.103478 .

Gebremedhn EG, G.F.J.P.A.M.J., Lemma. Patient satisfaction with the perioperative surgical services and associated factors at a University Referral and Teaching Hospital, 2014: a cross-sectional study. 2017. 27(1) https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2017.27.176.10671 .

Kibru EA et al. Patient satisfaction with post-operative surgical services and associated factors at Addis Ababa City government tertiary hospitals’ surgical ward, cross-sectional study, 2022. 2023. 45 https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2023.45.189.38416 .

Trinh LN, Fortier MA, Kain ZNJPM. Primer on adult patient satisfaction in perioperative settings. 2019. 8: p. 1–13 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13741-019-0122-2 .

Astier A et al. What is the role of technology in improving patient safety? A French, German and UK healthcare professional perspective. 2020. 25(6): p. 219–24 https://doi.org/10.1177/2516043520975661 .

Tadesse F, Yohannes Z, J.R.R.J.H L. Knowledge and practice of pain assessment and management and factors associated with nurses’ working at Hawassa University Referral Hospital, Hawassa city, South Ethiopia. 2016. 6(3): p. 24–8.

Criscitelli TJAj. Improving efficiency and patient experiences: the perioperative surgical home model. 2017. 106(3): p. 249–53 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aorn.2017.07.009 .

Alemu ME, Worku WZ, Berhie AYJH. Patient satisfaction and associated factors towards surgical service among patients undergoing surgery at referral hospitals in western Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia. 2023. 9(3) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14266 .

Alito GA, Madebo WE, Eromo NC, Quality of Perioperative Informations Provided and it’s Associated Factors Among Adult Patients Who Undergone Surgery in Public Hospitals of Gamo &Gofa Zones: A Mixed Design Study, Ethiopia S. 2019. 2019 https://gssrr.org/index.php/JournalOfBasicAndApplied/article/view/11761 .

Endale Simegn A et al. Patient Satisfaction Survey on Perioperative Anesthesia Service in University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia, 2021. 2021. 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/3379850 .

Tadesse B et al. Preoperative Patient Education Practices and Predictors Among Nurses Working in East Amhara Comprehensive Specialized Hospitals, Ethiopia, 2022. 2023: p. 237–247 https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S398663 .

Findik UY et al. Patient satisfaction with nursing care and its relationship with patient characteristics. 2019. 12(2): p. 162–9 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-2018.2009.00511.x .

Teng K, Norazliah SJJEH. Surgical patients’ satisfaction of nursing care at the orthopedic wards in hospital universiti sains Malaysia (HUSM). 2012. 3(1): p. 36–43.

Dawood KSJM-LU. Preoperative anxiety and fears among adult Surgical patients in Baghdad Teaching Hospital, Iraq. 2020. 20(1) https://doi.org/10.37506/v20/i1/2020/mlu/194433 .

Dibabu AM et al. Preoperative anxiety and associated factors among women admitted for elective obstetric and gynecologic surgery in public hospitals, Southern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. 2023. 23(1): p. 728 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-05005-2 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

We extend our sincere appreciation and gratitude to Wolaita Sodo University and our supervisors for their invaluable advice and supportive mentorship throughout this study. We would also like to express our thanks to the management and staff of the health institution, as well as the dedicated data collectors who played a crucial role in gathering the necessary data. Moreover, we are deeply grateful to the study participants and all other groups and individuals who contributed their time and effort to make this research possible. Their valuable contributions have been instrumental in the success of this study.

No funding was received.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Adult Health Nursing, School of Nursing, College of Health Science and Medicine, Wolaita Sodo University, Sodo, Ethiopia

Bizuayehu Atinafu Ataro, Eshetu Elfios Endirias & Getachew Nigussie Bolado

Maternity and Child Health Nursing, School of Nursing, College of Health Science and Medicine, Wolaita Sodo University, Sodo, Ethiopia

Temesgen Geta

Pediatrics and Child Health Nursing, School of Nursing, College of Health Science and Medicine, Wolaita Sodo University, Sodo, Ethiopia

Christian Kebede Gadabo

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

BAA wrote a manuscript, conceived data and designed a study, supervised the data collection, performed the analysis, interpreted data, drafted a manuscript, and revised and approved a manuscript for publication. TG, EEE, and GNB assisted in designing the study, were involved in data analysis and interpretation, and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Bizuayehu Atinafu Ataro or Getachew Nigussie Bolado .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

We obtained ethical clearance from the Ethical Review Committee of the Wolaita Sodo University Institutional Review Board (IRB-WSU). Written informed consent was obtained from respondents during data collection after explaining the purpose of the study. Information was also collected anonymously after obtaining written consent from each respondent, ensuring confidentiality by omitting their name and personal identification throughout the data collection period. The study identification number went from 001 to 468. This code was stored in electronic format, encrypted using the encryption software Mac OS X version 10.9.8, and password-protected on the principal investigator’s personal computer. No other identifier was collected, such as a name or the participant’s home address. Participants were also informed that they have the right to refuse, stop, or withdraw at any time during data collection. Finally, participants were informed that there was no incentive or harm to their participation in this study. This declaration was obtained according to the Helsinki form.

We, the undersigned, affirm that this paper is an original piece of work conducted by us and has not been previously presented or published in any Journal. We are fully aware of the importance of academic integrity and understand that plagiarism is strictly prohibited. Any direct quotations or material taken from other sources have been appropriately referenced and credited.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. The authors declare the absence of any other conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Ataro, B.A., Geta, T., Endirias, E.E. et al. Patient satisfaction with preoperative nursing care and its associated factors in surgical procedures, 2023: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs 23 , 235 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-01881-5

Download citation

Received : 10 January 2024

Accepted : 18 March 2024

Published : 08 April 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-01881-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Preoperative nursing care

- Patient satisfaction

- Surgical procedure

- Associated factors

BMC Nursing

ISSN: 1472-6955

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Preoperative Phase

The patient who consents to have surgery , particularly surgery that requires a general anesthetic, renders himself dependent on the knowledge, skill, and integrity of the health care team. In accepting this trust, the healthcare team members have an obligation to make the patient’s welfare their first consideration during the surgical experience.

The scope of activities during the preoperative phase includes the establishment of the patient’s baseline assessment in the clinical setting or at home, carrying out preoperative interview and preparing the patient for the anesthetic to be given and the surgery.

Although the physician is responsible for explaining the surgical procedure to the patient, the patient may ask the nurse questions about the surgery. There may be specific learning needs about the surgery that the patient and support persons should know. A nursing care plan and a teaching plan should be carried out. During this phase, emphasis is placed on:

- Assessing and correcting physiological and psychological problems that may increase surgical risk.

- Giving the patient and significant others complete learning and teaching guidelines regarding the surgery.

- Instructing and demonstrating exercises that will benefit the patient postoperatively.

- Planning for discharge and any projected changes in lifestyle due to the surgery.

Physiologic Assessment

Before any treatment is initiated, a health history is obtained and a physical examination is performed during which vital signs are noted and a data base is establish for future comparisons.

The following are the physiologic assessments necessary during the preoperative phase:

- Obtain a health history and perform a physical examination to establish vital signs and a database for future comparisons.

- Assess patient’s usual level of functioning and typical daily activities to assist in patient’s care and recovery or rehabilitation plans.

- Assess mouth for dental caries, dentures, and partial plates. Decayed teeth or dental prostheses may become dislodged during intubation for anesthetic delivery and occlude the airway.

- Nutritional status and needs – determined by measuring the patient’s height and weight, triceps skinfold, upper arm circumference, serum protein levels and nitrogen balance. Obesity greatly increases the risk and severity of complications associated with surgery.

- Fluid and Electrolyte Imbalance – Dehydration , hypovolemia and electrolyte imbalances should be carefully assessed and documented.

- Drug and alcohol use – the acutely intoxicated person is susceptible to injury .

- Respiratory status – patients with pre-existing pulmonary problems are evaluated by means pulmonary function studies and blood gas analysis to note the extent of respiratory insufficiency. The goal for potential surgical patient us to have an optimum respiratory function. Surgery is usually contraindicated for a patient who has a respiratory infection.

- Cardiovascular status – cardiovascular diseases increases the risk of complications. Depending on the severity of symptoms, surgery may be deferred until medical treatment can be instituted to improve the patient’s condition.

- Hepatic and renal function – surgery is contraindicated in patients with acute nephritis, acute renal insufficiency with oliguria or anuria, or other acute renal problems. Any disorder of the liver on the other hand, can have an effect on how an anesthetic is metabolized.

- Presence of trauma

- Endocrine function – diabetes , corticosteroid intake, amount of insulin administered

- Immunologic function – existence of allergies, previous allergic reactions, sensitivities to certain medications, past adverse reactions to certain drugs, immunosuppression

- Adrenal corticosteroids – not to be discontinued abruptly before the surgery. Once discontinued suddenly, cardiovascular collapse may result for patients who are taking steroids for a long time. A bolus of steroid is then administered IV immediately before and after surgery.

- Diuretics – thiazide diuretics may cause excessive respiratory depression during the anesthesia administration.

- Phenothiazines – these medications may increase the hypotensive action of anesthetics.

- Antidepressants – MAOIs increase the hypotensive effects of anesthetics.

- Tranquilizers – medications such as barbiturates , diazepam and chlordiazepoxide may cause an increase anxiety , tension and even seizures if withdrawn suddenly.

- Insulin – when a diabetic person is undergoing surgery, interaction between anesthetics and insulin must be considered.

- Antibiotics – “Mycin” drugs such as neomycin, kanamycin, and less frequently streptomycin may present problems when combined with curariform muscle relaxant. As a result nerve transmission is interrupted and apnea due to respiratory paralysis develops.

Gerontologic Considerations

- Monitor older patients undergoing surgery for subtle clues that indicate underlying problems since elder patients have less physiologic reserve than younger patients.

- Monitor also elderly patients for dehydration , hypovolemia , and electrolyte imbalances.

Nursing Diagnosis

The following are possible nursing diagnosis during the preoperative phase:

- Anxiety related to the surgical experience (anesthesia, pain ) and the outcome of surgery

- Risk for Ineffective Therapeutic Management Regiment related to deficient knowledge of preoperative procedures and protocols and postoperative expectations

- Fear related to perceived threat of the surgical procedure and separation from support system

- Deficient Knowledge related to the surgical process

Diagnostic Tests

These diagnostic tests may be carried out during the perioperative phase:

- Blood analyses such as complete blood count , sedimentation rate, c-reactive protein, serum protein electrophoresis with immunofixation, calcium , alkaline phosphatase, and chemistry profile

- X-ray studies

- MRI and CT scans (with or without myelography)

- Electrodiagnostic studies

- Endoscopies

- Tissue biopsies

- Stool studies

- Urine studies

Significant physical findings are also noted to further describe the patient’s overall health condition. When the patient has been determined to be an appropriate candidate for surgery, and has elected to proceed with surgical intervention, the pre-operative assessment phase begins.

The purpose of pre-operative evaluation is to reduce the morbidity of surgery, increase quality of intraoperative care, reduce costs associated with surgery, and return the patient to optimal functioning as soon as possible.

Psychological Assessment

Psychological nursing assessment during the preoperative period:

- Fear of the unknown

- Fear of death

- Fear of anesthesia

- Concerns about loss of work, time, job and support from the family

- Concerns on threat of permanent incapacity

- Spiritual beliefs

- Cultural values and beliefs

- Fear of pain

Psychological Nursing Interventions

- Explore the client’s fears, worries and concerns.

- Encourage patient verbalization of feelings.

- Provide information that helps to allay fears and concerns of the patient.

- Give empathetic support.

Informed consent

- Reinforce information provided by surgeon.

- Notify physician if patient needs additional information to make his or her decision.

- Ascertain that the consent form has been signed before administering psychoactive premedication. Informed consent is required for invasive procedures, such as incisional, biopsy , cystoscopy , or paracentesis; procedures requiring sedation and/or anesthesia; nonsurgical procedures that pose more than slight risk to the patient (arteriography); and procedures involving radiation .

- Arrange for a responsible family member or legal guardian to be available to give consent when the patient is a minor or is unconscious or incompetent (an emancipated minor [married or independently earning own living] may sign his or her own surgical consent form).

- Place the signed consent form in a prominent place on the patient’s chart.

An informed consent is necessary to be signed by the patient before the surgery. The following are the purposes of an informed consent:

- Protects the patient against unsanctioned surgery.

- Protects the surgeon and hospital against legal action by a client who claims that an unauthorized procedure was performed.

- To ensure that the client understands the nature of his or her treatment including the possible complications and disfigurement.

- To indicate that the client’s decision was made without force or pressure.

Criteria for a Valid Informed Consent

- Consent voluntarily given. Valid consent must be freely given without coercion.

- For incompetent subjects, those who are NOT autonomous and cannot give or withhold consent, permission is required from a responsible family member who could either be apparent or a legal guardian. Minors (below 18 years of age), unconscious, mentally retarded, psychologically incapacitated fall under the incompetent subjects.

- Procedure explanation and the risks involved

- Description of benefits and alternatives

- An offer to answer questions about the procedure

- Statement that emphasizes that the client may withdraw the consent

- The information in the consent must be written and be delivered in language that a client can comprehend.

- Should be obtained before sedation.

Nursing Interventions

Reducing anxiety and fear.

- Provide psychosocial support.

- Be a good listener, be empathetic, and provide information that helps alleviate concerns.

- During preliminary contacts, give the patient opportunities to ask questions and to become acquainted with those who might be providing care during and after surgery.

- Acknowledge patient concerns or worries about impending surgery by listening and communicating therapeutically.

- Explore any fears with patient, and arrange for the assistance of other health professionals if required.

- Teach patient cognitive strategies that may be useful for relieving tension, overcoming anxiety, and achieving relaxation, including imagery, distraction, or optimistic affirmations.

Managing Nutrition and Fluids

- Provide nutritional support as ordered to correct any nutrient deficiency before surgery to provide enough protein for tissue repair.

- Instruct patient that oral intake of food or water should be withheld 8 to 10 hours before the operation (most common), unless physician allows clear fluids up to 3 to 4 hours before surgery.

- Inform patient that a light meal may be permitted on the preceding evening when surgery is scheduled in the morning, or provide a soft breakfast, if prescribed, when surgery is scheduled to take place after noon and does not involve any part of the GI tract.

- In dehydrated patients, and especially in older patients, encourage fluids by mouth, as ordered, before surgery, and administer fluids intravenously as ordered.

- Monitor the patient with a history of chronic alcoholism for malnutrition and other systemic problems that increase the surgical risk as well as for alcohol withdrawal ( delirium tremens up to 72 hours after alcohol withdrawal).

Promoting Optimal Respiratory and Cardiovascular Status

- Urge patient to stop smoking 2 months before surgery (or at least 24 hours before).

- Teach patient breathing exercises and how to use an incentive spirometer if indicated.

- Assess patient with underlying respiratory disease (eg, asthma , chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD]) carefully for current threats to pulmonary status; assess patient’s use of medications that may affect postoperative recovery.

- In the patient with cardiovascular disease, avoid sudden changes of position, prolonged immobilization, hypotension or hypoxia, and overloading of the circulatory system with fluids or blood.

Supporting Hepatic and Renal Function

- If patient has a disorder of the liver, carefully assess various liver function tests and acid–base status.

- Frequently monitor blood glucose levels of the patient with diabetes before, during, and after surgery.

- Report the use of steroid medications for any purpose by the patient during the preceding year to the anesthesiologist and surgeon.

Monitor patient for signs of adrenal insufficiency.

- Assess patients with uncontrolled thyroid disorders for a history of thyrotoxicosis (with hyperthyroid disorders) or respiratory failure (with hypothyroid disorders).

Promoting Mobility and Active Body Movement

- Explain the rationale for frequent position changes after surgery (to improve circulation, prevent venous stasis, and promote optimal respiratory function) and show patient how to turn from side to side and assume the lateral position without causing pain or disrupting IV lines, drainage tubes, or other apparatus.

- Discuss any special position patient will need to maintain after surgery (eg, adduction or elevation of an extremity) and the importance of maintaining as much mobility as possible despite restrictions.

- Instruct patient in exercises of the extremities, including extension and flexion of the knee and hip joints (similar to bicycle riding while lying on the side); foot rotation (tracing the largest possible circle with the great toe); and range of motion of the elbow and shoulder.

- Use proper body mechanics, and instruct patient to do the same. Maintain patient’s body in proper alignment when patient is placed in any position.

Respecting Spiritual and Cultural Beliefs

- Help patient obtain spiritual help if he or she requests it; respect and support the beliefs of each patient.

- Ask if the patient’s spiritual adviser knows about the impending surgery.

- When assessing pain, remember that some cultural groups are unaccustomed to expressing feelings openly. Individuals from some cultural groups may not make direct eye contact with others; this lack of eye contact is not avoidance or a lack of interest but a sign of respect.

- Listen carefully to patient, especially when obtaining the history. Correct use of communication and interviewing skills can help the nurse acquire invaluable information and insight. Remain unhurried, understanding, and caring.

Providing Preoperative Patient Education

- Teach each patient as an individual, with consideration for any unique concerns or learning needs.

- Begin teaching as soon as possible, starting in the physician’s office and continuing during the pre admission visit, when diagnostic tests are being performed, through arrival in the operating room.

- Space instruction over a period of time to allow patient to assimilate information and ask questions.

- Combine teaching sessions with various preparation proce-dures to allow for an easy flow of information. Include descriptions of the procedures and explanations of the sensations the patient will experience.

- During the preadmission visit, arrange for the patient to meet and ask questions of the perianesthesia nurse, view audiovisuals, and review written materials. Provide a telephone number for patient to call if questions arise closer to the date of surgery.

- Reinforce information about the possible need for a ventilator and the presence of drainage tubes or other types of equipment to help the patient adjust during the postoperative period .

- Inform the patient when family and friends will be able to visit after surgery and that a spiritual advisor will be available if desired.

Teaching the Ambulatory Surgical Patient

- For the same day or ambulatory surgical patient, teach about discharge and follow-up home care. Education can be provided by a videotape, over the telephone, or during a group meeting, night classes, preadmission testing, or the preoperative interview.

- Answer questions and describe what to expect.

- Tell the patient when and where to report, what to bring (insurance card, list of medications and allergies), what to leave at home (jewelry, watch, medications, contact lenses), and what to wear (loose-fitting, comfortable clothes; flat shoes).

- During the last preoperative phone call, remind the patient not to eat or drink as directed; brushing teeth is permitted, but no fluids should be swallowed.

Teaching Deep Breathing and Coughing Exercises

- Teach the patient how to promote optimal lung expansion and consequent blood oxygenation after anesthesia by assuming a sitting position, taking deep and slow breaths (maximal sustained inspiration), and exhaling slowly.

- Demonstrate how patient can splint the incision line to minimize pressure and control pain (if there will be a thoracic or abdominal incision).

- Inform patient that medications are available to relieve pain and that they should be taken regularly for pain relief to enable effective deepbreathing and coughing exercises.

Explaining Pain Management

- Instruct patient to take medications as frequently as prescribed during the initial postoperative period for pain relief .

- Discuss the use of oral analgesic agents with patient before surgery, and assess patient’s interest and willingness to participate in pain relief methods.

- Instruct patient in the use of a pain rating scale to promote postoperative pain management.

Preparing the Bowel for Surgery

- If ordered preoperatively, administer or instruct the patient to take the antibiotic and a cleansing enema or laxative the evening before surgery and repeat it the morning of surgery.

- Have the patient use the toilet or bedside commode rather than the bedpan for evacuation of the enema, unless the patient’s condition presents some contraindication.

Preparing Patient for Surgery

- Instruct patient to use detergent–germicide for several days at home (if the surgery is not an emergency).

- If hair is to be removed, remove it immediately before the operation using electric clippers.

- Dress patient in a hospital gown that is left untied and open in the back.

- Cover patient’s hair completely with a disposable paper cap; if patient has long hair, it may be braided; hairpins are removed.

- Inspect patient’s mouth and remove dentures or plates.

Remove jewelry, including wedding rings

- If patient objects, securely fasten the ring with tape.

- Give all articles of value, including dentures and prosthetic devices, to family members , or if needed label articles clearly with patient’s name and store in a safe place according to agency policy.

- Assist patients (except those with urologic disorders) to void immediately before going to the operating room.

- Administer preanesthetic medication as ordered, and keep the patient in bed with the side rails raised. Observe patient for any untoward reaction to the medications. Keep the immediate surroundings quiet to promote relaxation.

Transporting Patient to Operating Room

- Send the completed chart with patient to operating room; attach surgical consent form and all laboratory reports and nurses’ records, noting any unusual last minute observations that may have a bearing on the anesthesia or surgery at the front of the chart in a prominent place.

- Take the patient to the preoperative holding area, and keep the area quiet, avoiding unpleasant sounds or conversation.

Attending to Special Needs of Older Patients

- Assess the older patient for dehydration , constipation , and malnutrition; report if present.

- Maintain a safe environment for the older patient with sensory limitations such as impaired vision or hearing and reduced tactile sensitivity.

- Initiate protective measures for the older patient with arthritis , which may affect mobility and comfort. Use adequate padding for tender areas. Move patient slowly and protect bony prominences from prolonged pressure. Provide gentle massage to promote circulation.

- Take added precautions when moving an elderly patient because decreased perspiration leads to dry, itchy, fragile skin that is easily abraded.

- Apply a lightweight cotton blanket as a cover when the elderly patient is moved to and from the operating room, because decreased subcutaneous fat makes older people more susceptible to temperature changes.

- Provide the elderly patient with an opportunity to express fears; this enables patient to gain some peace of mind and a sense of being understood

Attending to the Family’s Needs

- Assist the family to the surgical waiting room, where the surgeon may meet the family after surgery.

- Reassure the family they should not judge the seriousness of an operation by the length of time the patient is in the operating room.

- Inform those waiting to see the patient after surgery that the patient may have certain equipment or devices in place (ie, IV lines, indwelling urinary catheter, nasogastric tube , suction bottles, oxygen lines, monitoring equipment, and blood transfusion lines).

- When the patient returns to the room, provide explanations regarding the frequent postoperative observations.

Spiritual Considerations

- Perioperative Nursing

- Intraoperative Phase

- Postoperative Phase

7 thoughts on “Preoperative Phase”

thank you very much Matt Vera, I love that and I love you for what you did and think for student now a days……….I love you very much!!!!!!!!!!!!!

thank you po for all of these 🤗

Thank you Sir Matt for your input. This information will guide me tremendously.

The site has been helpful and has provided all that I needed for learning.

That’s music to my ears! Super happy to hear that the post about the preoperative phase met your needs. If you ever have questions or want more details on other phases or topics, just let me know. Here to support your learning journey! Thank you, Phaustine for your comment.

Amazing, this is very helpful and in depth knowledge. I find this site helpful and as a second avenue to reinstate my knowledge after my professor’s lecture in class. And it is mostly almost the same. So it helps and stick. Thank you a lot. The exams practice questions does help prepare for my actual in person exams! Started nursing school August 2023, and in my first year(second semester). May the Lord bless you for your efforts and time on these. Thank you!!

Thank you so much for your kind words and blessings! It’s incredibly rewarding to hear how Nurseslabs has been a valuable resource for you, especially as you navigate through your first year of nursing school. Exciting times right? Congratulations on starting this journey in August 2023, and it’s great to know you’re already making such positive strides in your second semester.

We’re here to support your learning every step of the way, so if there’s ever a topic you’re curious about or need more practice questions on, don’t hesitate to ask. Your success is what motivates us to keep creating and improving our content.

Best of luck with your studies and exams! May your passion for nursing continue to grow, and may you find every success in your career.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Quality and Safety Education for Nurses

Strategy submission, perioperative unfolding case study.

Gerry Altmiller

EdD, APRN, ACNS-BC, ANEF, FAAN

Professor of Nursing

Institution:

The College of New Jersey

Competency Categories:

Informatics, Patient-Centered Care, Quality Improvement, Safety, Teamwork and Collaboration

Learner Level(s):

Continuing Education, New Graduates/Transition to Practice, Pre-Licensure ADN/Diploma, Pre-Licensure BSN, Staff Development

Learner Setting(s):

Classroom, Skills or Simulation Laboratories

Strategy Type:

Case Studies

Learning Objectives:

Strategy Overview:

Submitted Materials:

Perioperative-unfolding-case-4.pptx - https://drive.google.com/open?id=11dYMfwXPejfb9jSTMPKaZ0NMyY3L_j-F&usp=drive_copy

267.2-Student-Worksheet-Perioperative-Unfolding-Case.docx - https://drive.google.com/open?id=1qzAel75FBGLysXeyezkK-wbN6ym5qqps&usp=drive_copy

Additional Materials:

Students can use the student worksheet to record data as the case study unfolds.

Evaluation Description:

Case Studies: Preoperative assessment

Trust/Healthboard/Hospital: University Hospitals Bristol

Thoracic pre-operative assessment

The thoracic multidisciplinary team hold a weekly ‘complex case review meeting’ to plan the most appropriate care for high risk patients. Discussion covers the type of surgery required, the patient’s pre-op review and investigations. Morbidity scoring systems are completed. Together, these guide recommendations for prehabilitation and appropriate post-operative care.

Previd incorporates video assessment where patients are videoed introducing themselves, performing the ‘sit-stand test’ and walking a fixed distance. The sit-stand test is analysed as to the quality of the exercise, the number of repetitions and the motivation the patient shows during the test. They are then timed walking down a 20 m slope and back up. The camera is kept running after completion to see how breathless they are. This video is essential as surgeons pool patients, and therefore may not have met face to face; seeing them on screen adds additional information to numbers and scans.