Customer-Focused Service Guarantees and Transparency Practices (2018)

Chapter: chapter 2 - literature review.

Below is the uncorrected machine-read text of this chapter, intended to provide our own search engines and external engines with highly rich, chapter-representative searchable text of each book. Because it is UNCORRECTED material, please consider the following text as a useful but insufficient proxy for the authoritative book pages.

10 The Need for Customer-Focused Public Transit Ensuring customer satisfaction is essential for businesses because a customerâs satisfaction with a particular transaction often determines whether the customer will return and whether the customer will describe the interaction in a positive or negative way to others. Particularly true for private sector and for-profit organizations, customers have choices and may choose to purchase goods and services elsewhere if they are not satisfied. If customers choose competitors, companies will see declines in revenue and profit and may ultimately even have to close. In the public sector, the connection between customer satisfaction and organizational stability and financial standing may not be as directâparticularly in public services that are largely, if not wholly, provided by a single public entity. When there is only one service provider (or even a handful of them), âcustomers cannot express their dissatisfaction with the service . . . by switching to another operatorâ (Schiefelbusch 2009, p. 6). However, there are several services and regions in which both the public and private sectors essentially compete for customers (e.g., package delivery and transportation). In the services where competition exists, public agencies may have to continually win customersâ loyalty. The increasing ability for customers to make alternative choices is especially apparent in the public transit space, where shared mobility and similar for-hire transportation services have entered the marketplace. Advances in technology and social media also have provided customers of both public and private services increased capability to voice concerns, provide reviews, and rate service providers. Because those venues for comments and ratings may be completely open to the public and sharable with others, the damage of a negative review can have far-reaching implications. Alternatives to public transit and easy tools for sharing personal experiences can provide significant impetus for public transit agencies to become more customer focused. However, there is value simply in improving the satisfaction of citizens who interact with public servicesâ high-quality public services may help improve citizensâ quality of life. Being customer focused helps produce a positive experience for pub- lic transit passengersâa stated or unstated goal of many public transit agencies. Customer-focused public transit can take different forms and be manifested in many different types of programs and initiatives. Examples include: ⢠Implementing mystery shopper programs (Miller 1995), ⢠Improving the quality of transit service based on customer feedback (Miller 1995, Foote 2004), ⢠Measuring performance from a passengerâs perspective (Kesten and Ãgüt 2014, Morton et al. 2016). C h a p t e r 2 Literature Review There is value in improving the satisfaction of citizens who interact with public servicesâhigh-quality public services may help improve citizensâ quality of life.

Literature review 11 ⢠Providing a service guaranteeâincluding money-back guarantees (Giard 2002, Lidén 2004), and ⢠Increasing agency accountability to the customer and the public (Adams 2015). Although there are several examples of transit agencies that have worked to become more customer focused, there is little understanding of the actual impacts customer-focused public transit initiatives have on public transit customers and transit providers. TCRP Synthesis 45 found that âthe public transportation industry uses relatively few spe- cific methods to achieve customer satisfactionâ (Potts 2002, p. 26). Of the 33 transit agencies that responded to the TCRP Synthesis 45 survey, only nine used some form of service guarantee, and two had a passen- ger bill of rights. The synthesis made no mention of customer-focused transparency as a customer-focused practice. This report focuses on two particular customer-focused practices and their relationship with each other: service guarantees and customer-focused transparency. Although these two practices are not codependent, they go well together: service guarantees provide a way for a transit agency to address an individualâs specific negative experience, and transparency provides a mechanism for a transit agency to present its efforts to improve its aggregate performance to a broad spectrum of public transit stakeholders (customers and noncustomers). Service Guarantees In most cases, customers have an implicit expectation that they should have a positive experi- ence with a service provider or get some remuneration, if not all of their money back. This is true for restaurants, retailers, services, and even vending machines. Companies have often surpassed this implicit expectation and provided service guaranteesâexplicit promises to customers that delineate exactly what customers can expect in the event services do not meet expectations. Although research on service guarantees has been under way for several decades, there is still significant debate on the exact definition and purpose of a service guarantee. Generally speaking, a service guarantee refers to a promise made by a service provider that a customer will experience a certain level or quality of service. A service guarantee may include as a part of that promise some form of recompense or remuneration for customers whose experi- ences do not meet the minimum level of quality promised by the service guarantee. The Role of Service Guarantees Lidén (2004) presents a summary of perspectives on the roles that service guarantees can serve (see Figure 3). First, some researchers state that a service guaranteeâs main feature is to ârestore customer satisfaction after a service failureâ (p. 10). Second, other researchers state that service guarantees help customers understand the quality of the service or product before a pur- chase or utilization. In this case, the service guarantee helps customers choose a service provider and becomes a marketing tool. Third, some researchers blend both the marketing and restorative features of service guarantees and argue that guarantees help increase the appeal of a product or service before purchase and help recover customer satisfaction after a negative experience. Research suggests that service guarantees help increase not only customer confidence when deciding whether to make a purchase or pay for a service (Hogreve and Gremler 2009, Neugebauer 2009) but also satisfaction of customers who invoke the guarantee (Giard 2002, Lidén 2004). Lidén (2004) found evidence that the satisfaction of public transit customers who TCRP Synthesis 45 found that âthe public transportation industry uses relatively few specific methods to achieve customer satisfactionâ (Potts 2002, p. 26).

12 Customer-Focused Service Guarantees and transparency practices invoked the service guarantee and had their claim resolved in their favor were more satisfied than they were before the service problem had occurred. Service guarantees not only work directly on customer satisfaction but also indirectly improve customer satisfaction by focusing transit agency employees on improving service quality. That is, service guar- antees can serve as a quality control tool (Neugebauer 2009) and an impetus behind quality improvements (Giard 2002, Lidén 2004). For example, Giard (2002) stated, âThe arrival of the [service guarantee] has mobilized [Société de Transport de Laval]. . . . In less than two years, the number of late bus arrivals has been more than halved, while the time required for processing applications and claims has been slashed by 40%â (p. 6). (Société de Transport de Laval [STL] is a public transit operator in the city of Laval, Quebec, Canada.) The available evidence suggests that service guaranteesâparticularly those that provide for customer remunerationâcan play an important role in public transit by: ⢠Helping decrease the perceived risk of choosing to take transit, ⢠Providing a tool for transit agencies to maintain and improve public transit customer satisfaction when there are service problems, and ⢠Improving service quality through increased transit agency employee commitments to quality. Structure of Service Guarantees There is debate not only on the main purpose and role of service guarantees but also on the best specific contents of guarantees. As discussed by McDougall et al. (1998), service guarantees contain both a coverage statement (what services or qualities of service are guaranteed) and an Figure 3. Potential roles of service guarantees in both prepurchase and postpurchase decisions. Source: Created by author, based on Lidén (2004). Service guarantees not only work directly on customer satisfaction but also indirectly improve customer satisfaction by focusing transit agency employees on improving service quality.

Literature review 13 action statement (what the customer will receive in the event the covered services do not meet the set standard). (McDougall et al. use the term âpayoutâ instead of âaction,â but the author of the current synthesis uses âactionâ to refer to any action taken by a provider to fulfill its service guarantee, whether or not the action includes financial compensation.) The coverage and action statements in a service guarantee may be defined or undefined (see Table 1 for examples). McDougall et al. found that some customers preferred guarantees with well-defined coverage and action statements whereas others found undefined statements more appealing. In an oft-cited article, Hart (1988) argues that service guarantees should be unconditionalâ that is, the service provider should not place restrictions on the guarantee, and customers who are dissatisfied with their experiences should receive remuneration regardless of whether the cause of the service issue was within or without of the providerâs direct control. Hart also states that service guarantees should be: ⢠Easy to understand and communicate, ⢠Meaningful, ⢠Easy to invoke, and ⢠Easy and quick to collect on. Research continues to better define customer preferences for the content and impact of service guarantees across different private- and public-sector industries (e.g., see Lidén and SkÃ¥lén 2003). In this synthesis on public transit, service guarantees are defined as any explicit commitment to a quality customer experience, regardless of whether the agency compensates or responds directly to individual customers in the event the commitment is not met. This definition of service guarantee is relatively loose and allowed transit agencies with or without statements labeled as a âguaranteeâ to be included in this synthesis. For example, some transit agencies have what Neugebauer (2009) considers merely a âquality or performance promiseâ (p. 36)âin other words, a statement that promises a certain level of service without any specific restitution pro- vided to the customer for promises not kept. In these cases, the transit agency may guarantee a specific attribute of a transit trip (e.g., reliability, cleanliness) but not define the specific param- eters by which quality would be defined. These guarantees, by their nature, also make it nearly impossible to offer an action to restore customer confidence because the transit agency is not explicit about what it deems acceptable performance. Other transit agencies have service guarantees that are part of an official passenger charter or similar stand-alone policy that lists the transit agencyâs commitments to the customer. In many cases, these service guarantees define both the attribute of service and the expected level of quality (e.g., âtrains will arrive in 15 minutes of the scheduleâ) but do not necessarily establish an action in the event service does not meet the standard. Some public transit service guarantees provide for customer remuneration (e.g., a refund or credit toward future transit fares) or other action in the event the service does not meet Coverage Defined Undefined Action Defined Delivery within 30 minutes or your money back. Satisfaction guaranteed or your money back. Undefined Delivery within 30 minutes. Period. Satisfaction guaranteed. Period. Source: Adapted from McDougall et al. (1998). Table 1. Example service guarantees with defined and undefined coverage and remuneration statements.

14 Customer-Focused Service Guarantees and transparency practices the level of quality promised in the guarantee (e.g., âTrains will arrive within 15 minutes of the schedule or your ride is freeâ). This form of guarantee was the rarest found during the literature review and the rarest found in the transit agency survey. Most service guarantees that do provide an action have several limitations or exclusions under which the guarantee does not apply (e.g., delays caused by extreme weather are not eligible for the guarantee). To demonstrate how these forms of service guarantees fit into the existing literature, several example service guarantees were developed for this report and categorized according to a modified version of McDougall et al.âs (1998) taxonomy for service guarantee structures (see Table 2). Because some transit agencies define what a customer should experience (e.g., reliability) but not the precise definition of that experience (e.g., trains will arrive within 15 minutes of the schedule), a type of coverage statement was added that allowed for defining the covered attribute of service but not defining the expected level of quality. A type of action statement was added called âno actionâ to reflect that transit agencies make service guarantees but rarely back them with actions to take when the guarantee is not met. Most transit agencies had service guarantees with defined attributes but undefined quality levels and no defined actions (see Chapter 3). The lack of standardization of service guarantees across transit agencies likely demonstrates the complex nature of the issue and the apparent dearth of resources available to transit agencies to make informed decisions about whether and how to construct their service guarantees. Customer-Focused Transparency Expectations and Variations of Transparency As with expectations for high-quality service, citizens are increasingly expecting transparencyâ particularly from governments and public service agencies. Transparency has been defined in many ways but is best summed up by Grimmelikhuijsen and Welch (2012) as âthe disclosure of information by an organization that enables external actors to monitor and assess its internal workings and performanceâ (p. 563). Sharing information with the public may be done for many reasons: for example, to maintain political competitiveness (Bearfield and Bowman 2017), adhere to a formal rule or regulation, increase public participation (Welch 2012), or as part of a broad transparency strategy. Although the rationale may vary, transparency has been found (in some cases) to result in actual improve- ments in service performance and financial management (Cucciniello et al. 2017) and citizen satisfaction (Ma 2017). Coverage Defined Attribute and Quality Level Defined Attribute but No Quality Level Undefined Attribute Action Defined Trains will arrive within 15 minutes of the schedule or your ride is free. Trains will be reliable or your ride is free. Youâll be satisfied with your trip or your ride is free. Undefined Trains will arrive within 15 minutes of the schedule. Contact us if you experience a problem. Trains will be reliable. Contact us if you experience a problem. Youâll be satisfied with your trip, and contact us if you arenât. No Action Trains will arrive within 15 minutes of the schedule. Trains will be reliable. Youâll be satisfied with your trip. Source: Adapted from McDougall et al. (1998) and informed by the authorâs literature review. Table 2. Example transit service guarantees for all types of coverage and action statements.

Literature review 15 Organizations can choose the extent of their transparency initiatives by determining trans- parency type (data, policy, or both), topic (e.g., finance, human resources, maintenance), time period (days, weeks, months, or years), and level of detail (aggregated versus transactional). Not surprisingly, there is a great deal of variability around the extent to which local governments and other public organizations share information with the public (e.g., Cucciniello and Nasi 2014, Bearfield and Bowman 2017). Customer-Focused Transparency in Public Transit Transit agencies also exhibit this variability of transparency, so not all transit agency transparency is necessarily customer focused. Customer- focused transparency is not a well-defined term in the literature; how- ever, in this report, the term refers to any open and public reporting updated at least annually that includes customer-focused metrics. Customer-focused metrics are those that reflect some aspect of the customer experience, when either riding transit or interacting with the transit agency. Examples of customer-focused metrics are listed as metrics from the customer point of view in TCRP Report 88 (Nakanishi 2003). In addition to customer-focused transparency, a transit agency may be transparent in other ways: for example, by opening its schedule and real-time data to the public using standardized data sets such as the general transit feed specification (e.g., see Rojas 2012), or opening its financial data to the public [e.g., Capital Metro in Austin, Texas, reports its budget, audits, and even financial transactions to the public (Capital Metro n.d.)]. Although financial and service information can have value for transit customers, these data do not portray the quality of transit service and do not reflect the experience of customers. This synthesis project did not accept as customer-focused transparency any transparent reporting of finances, ridership, or other metrics that did not measure some aspect of the customerâs experience. Last, many agencies are required to report their performance data to a board or other oversight body, which often maintain openness to the public through meeting agendas and report contents. Transit agencies that report data only as a part of a board or oversight process and not as a stand- alone effort may not be included in this synthesis because reports to oversight bodies may not be easily found on a transit agency website. In addition, reporting only to oversight bodies may manifest a transit agencyâs wishes to meet mandates without actually having a strategy for being intentionally transparent. Resources Available to Transit Agencies Although extensive research has been done on service guarantees and transparency, there is still little available in resources for transit agencies to understand best practices, implications, and implementation strategies. Previous relevant transit-specific guidance includes ⢠TCRP Synthesis 45: Customer-Focused Transit: A Synthesis of Transit Practice (Potts 2002); ⢠TCRP Report 88: A Guidebook for Developing a Transit Performance-Measurement System (Nakanishi 2003); ⢠TCRP Report 141: A Methodology for Performance Measurement and Peer Comparison in the Public Transportation Industry (Ryus et al. 2010); ⢠National Rural Transit Assistance Programâs Customer Driven Service: Learnerâs Guide (National Rural Transit Assistance Program 2011); and ⢠The Canadian Urban Transit Associationâs (CUTA) Introducing a Passenger Charter: Your Guide for Success (CUTA 2013). Customer-focused metrics reflect some aspect of the customer experience, when either riding transit or interacting with the transit agency.

16 Customer-Focused Service Guarantees and transparency practices Although this handful of resources exist, they may not deal with specific topics (e.g., TCRP Synthesis 45 did not include transparency as a part of customer-focused transit), may be out- dated, or may be too general to be a ready and relevant resource to transit agencies specifically con sidering implementing a service guarantee or customer-focused transparency. The technol- ogy supporting transit agency services, passenger interactions, and transparent reporting has changed significantly in the last several years, and the operational context in which transit agencies operate and the mobility options available to potential transit customers look much different now than they did just a few years ago. As the literature review demonstrates, customer-focused service guarantees and transpar- ency may be beneficial, but they have many complexities, mixed theoretical underpinnings, and empirical evaluations. This synthesis builds on and extends previous transit-specific research to provide transit practitioners a snapshot of the current state of the industry concerning service guarantees and customer-focused transparency, including their prevalence, implementation strategies, benefits and challenges, and important lessons learned.

TRB's Transit Cooperative Research Program (TCRP) Synthesis 134: Customer-Focused Service Guarantees and Transparency Practices documents the nature and prevalence of customer-focused practices among transit providers in North America and supplements the discussion by including information from European transit providers.

A growing number of North American public transit agencies have adopted service guarantees or transparency practices as part of a customer-focused service strategy. Service guarantees describe the level of service customers can expect and the procedures they may follow if standards are not met. Transparency practices might include reporting performance metrics as online dashboards or report cards on the agency’s website. Currently, there is little existing research on these practices and experiences among U.S. transit providers.

Update June 29, 2018: Page i of the synthesis omits some of the authors. The correct author list is as follows:

Michael J. Walk

James P. Cardenas

Kristi Miller

Paige Ericson-Graber

Chris Simek

Texas A&M Transportation Institute

READ FREE ONLINE

Welcome to OpenBook!

You're looking at OpenBook, NAP.edu's online reading room since 1999. Based on feedback from you, our users, we've made some improvements that make it easier than ever to read thousands of publications on our website.

Do you want to take a quick tour of the OpenBook's features?

Show this book's table of contents , where you can jump to any chapter by name.

...or use these buttons to go back to the previous chapter or skip to the next one.

Jump up to the previous page or down to the next one. Also, you can type in a page number and press Enter to go directly to that page in the book.

To search the entire text of this book, type in your search term here and press Enter .

Share a link to this book page on your preferred social network or via email.

View our suggested citation for this chapter.

Ready to take your reading offline? Click here to buy this book in print or download it as a free PDF, if available.

Get Email Updates

Do you enjoy reading reports from the Academies online for free ? Sign up for email notifications and we'll let you know about new publications in your areas of interest when they're released.

Focusing the customer through smart services: a literature review

- Research Paper

- Open access

- Published: 09 February 2019

- Volume 29 , pages 55–78, ( 2019 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Sonja Dreyer ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8933-3714 1 ,

- Daniel Olivotti 1 ,

- Benedikt Lebek 2 &

- Michael H. Breitner 1

17k Accesses

53 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Smart services serve customers and their individual, continuously changing needs; information and communications technology enables such services. The interactions between customers and service providers form the basis for co-created value. A growing interest in smart services has been reported in the literature in recent years. However, a categorization of the literature and relevant research fields is still missing. This article presents a structured literature search in which 109 relevant publications were identified. The publications are clustered in 13 topics and across five phases of the lifecycle of a smart service. The status quo is analyzed, and a heat map is created that graphically shows the research intensity in various dimensions. The results show that there is diverse knowledge related to the various topics associated with smart services. One finding suggests that economic aspects such as new business models or pricing strategies are rarely considered in the literature. Additionally, the customer plays a minor role in IS publications. Machine learning and knowledge management are identified as promising fields that should be the focus of further research and practical applications. Concrete ideas for future research are presented and discussed and will contribute to academic knowledge. Addressing the identified research gaps can help practitioners successfully provide smart services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Towards a Better Understanding of Smart Services - A Cross-Disciplinary Investigation

Towards Managing Smart Service Innovation: A Literature Review

Data Science and Analytics: An Overview from Data-Driven Smart Computing, Decision-Making and Applications Perspective

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Increasing digitalization and the emergence of the Internet of Things have fostered growing interest in smart services in recent years (Georgakopoulos and Jayaraman 2016 ). Smart services are characterized by the fact that the service provider and the customer interact to create value. This process is called value co-creation (Gavrilova and Kokoulina 2015 ) and enables service providers to continuously adjust to a customer’s individual and constantly changing needs (Massink et al. 2010 ). Customers are supported, and new business models are realized via smart services.

The number of publications that have focused on smart services has greatly increased in recent years. Although these publications have answered many relevant research questions, none have yet articulated a systematic and comprehensive research agenda for smart services. Systematic insights in different topics help to provide a broader view on the subject (Kamp et al. 2016 ). Therefore, the objective of the article is to present a holistic overview of past research and opportunities for further research in the field of smart services.

The presented literature review clusters existing publications related to smart services based on topics and lifecycle phases. Both in theory and practice, the lifecycle concept is adopted to describe a product or service from the design to the continual improvement (e.g., Fischbach et al. 2013 ; Wiesner et al. 2015 ). It helps to organize the complex structure of a product or a service and makes it more transparent. In this article, this approach is also applied to smart services, since the lifecycle indicates that they are dynamic and constantly refined. How to involve customers to meet the requirements and to provide successful smart services varies in the different phases. Only passing the lifecycle together with the customers enables value co-creation. By investigating existing research and future research opportunities in the context of a smart service lifecycle, a new viewpoint is taken that is not yet considered in literature. It enables to consciously view a specific step from the strategy development to the continual improvement. Through the lifecycle, not only a topic-centered focus is considered in the present review but also an organizational perspective. It enables to identify phases that are unexplored.

The research intensity in different fields is discussed. It aims at getting an overview of smart service research. Past results are presented briefly, and research gaps are identified. For example, the customer is generally accepted as an essential component of successful smart services but has rarely been the focus of research. Additionally, few viewpoints on operating smart services exist.

Investigating concrete starting points for further research will advance the understanding of smart services in the IS literature. For example, some possible future contributions are identifying appropriate technology and necessary data streams. In practice, knowledge gained through theoretical research can be used to introduce new perspectives on smart services. For practitioners, designing, realizing and maintaining them is a key need (Kamp et al. 2016 ). Because such services are a relatively new development, best practice approaches have not been well defined. Theoretical investigations can help practitioners to provide smart services successfully.

To present a comprehensive literature review including suggestions for further research opportunities, the following research questions are investigated:

RQ 1: How does academic literature conceptually approach smart services along the smart service lifecycle?

RQ 2: Which research gaps and related further research opportunities can be derived from prior research on smart services?

Based on the approach presented by Webster and Watson ( 2002 ), a literature review is conducted by searching through academic databases using a set of predefined search terms. This review includes a forward and backward search, as well as a search using the Tool for Semantic Indexing and Similarity Queries (TSISQ), a literature tool presented by Koukal et al. ( 2014 ). In total, 109 publications were found to be relevant and are included in the literature review. After assigning each publication to at least one of the smart service lifecycle phases, an analysis of several topics is performed. Five lifecycle phases, in addition to the investigated topics, are used to develop a heat map. The heat map shows the research intensity for each combination of topics and lifecycle phases. Selected areas of the heat map are analyzed and discussed. Based on the findings, directions for further research are presented.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows: a definition of smart services is derived, and the smart service lifecycle is presented. Next, the research design is explained, and the results of the literature review are presented. Finally, results are discussed and directions for further research are developed. The article concludes with limitations and conclusions.

Smart services and a smart service lifecycle

Although there is little controversy regarding how to define smart services, various authors emphasize different aspects and characteristics of the fundamental topics. Smart services co-create value by the customers and providers via connected systems and machine intelligence (Gavrilova and Kokoulina 2015 ). Interaction between customer and provider is necessary, in addition to the service offered by the technology itself (Baldoni et al. 2010 ; Wünderlich et al. 2012 ; Demirkan et al. 2015 ). Through collaboration the service provider knows the current needs and thus can adapt the smart service constantly. Lee et al. ( 2012 ) suggested that value co-creation does not require direct input from a customer because functionalities should be provided in a convenient way. Nevertheless, the present article indicates that the customer and the environment are involved and form an important part in all phases from a strategic development to the improvement of operational smart services. This interaction can be direct, e.g. in form of feedback, or indirect, e.g. by providing information. By considering individual needs it is possible to improve and simplify the customers’ tasks and processes, both in the business-to-business (B2B) and the business-to-consumer (B2C) sector (Massink et al. 2010 ). Smart services are quality-based services, thus services in which the quality of processes plays a decisive role for economic success (Gerke and Tamm 2009 ).

Smart services are strictly based on field intelligence (Allmendinger and Lombreglia 2005 ). Field intelligence refers to the concept that connected systems and devices pave the way to intelligence that is higher than the intelligence of the individual parts. It is enabled by context information and high dynamics (Oh et al. 2010 ; Byun and Park 2011 ). Support from technology such as information and communications technology, as well as the ability to react to an individual’s context and its changes make up “smart” service (Calza et al. 2015 ). Intelligent sensors (i.e. sensors that not only collect data, but also prepare and preprocess them) are often used to determine the current contexts (Byun and Park 2011 ; Delfanti et al. 2015 ), combined with continuous communication and feedback (Wünderlich et al. 2015 ). Information from several sources, including technology, the environment and social contexts (Alahmadi and Qureshi 2015 ; Lee et al. 2012 ) is collected and then presented, or suggestions are made via data analysis (Kynsilehto and Olsson 2012 ).

Based on the aspects named in the literature, the following definition of smart services is derived, forming the basis for this article:

Smart services are individual, highly dynamic and quality-based service solutions that are convenient for the customer, realized with field intelligence and analyses of technology, environment and social context data (partially in real-time), resulting in co-creating value between the customer and the provider in all phases from the strategic development to the improvement of a smart service.

The definition contains the necessary attributes of a smart service from the article’s point of view. Individual customer needs are not mentioned as precondition because they must be considered to be able to offer individual smart services. Additionally, customer needs often are the result of data analyses what forms part of the definition. Information and communications technology is not named explicitly because it is necessary for field intelligence and analyses, what forms part of the definition. The reaction to the individual’s context is represented by naming that smart services are highly dynamic as well as individual. Intelligent sensors are only one possibility to receive data which is why it is not mentioned in the general definition. The same applies to the feedback of the customer. For what the collected data and information from different sources are used depends on the specific smart service and cannot be answered generally. As business and private customers are the only two possible target groups, it is assumed to be not a necessary part of the definition.

Predictive maintenance for production machines is an example for a smart service. Depending on the machines, production processes, current production planning and further factors, maintenance activities are planned and continually adapted. For example, mathematical models and artificial intelligence in connection with data in real-time contribute to an individual and dynamic solution. Constant exchange of knowledge and information enables the development as well as continual adaption and optimization of the applied predictive maintenance service. Additionally, feedback of the customer enables to adapt the scope of service. Thinking of predictive maintenance, after a while the customer might want that the provider does not only carry out predictive maintenance activities, but also the spare parts supply. The service provider orders spare parts when they are required, thereby fixed capital is reduced. Considering this aspect further, another form of collaboration between customer and service provider is imaginable; the customer can become a co-producer. When small spare parts, e.g. gearwheels, are needed, they could be printed in 3D by the customer itself. Thereby, machine downtimes resulting from delivery times are reduced. Detailed data and information that are required for the 3D print are supplied by the service provider.

For physical products, it is common to think in terms of their lifecycle, from the planning and development to the improvement stages. Services have a similar lifecycle (Fischbach et al. 2013 ). Several publications describe services in a lifecycle using a model that has phases progressing from idea to improvement (e.g., Niemann et al. 2009 ; Wiesner et al. 2015 ). Smart services are also subject to a lifecycle that ranges from strategic development to service improvement. In this article, it is referred to the basic service lifecycle defined in the Information Technology Infrastructure Library (ITIL) framework because it contains and clearly defines the phases of a service lifecycle. The sub-processes described in the ITIL lifecycle are not considered. This framework is widely accepted and contains best practice approaches, from both the public and private sectors (Cater-Steel et al. 2011 ). It is suitable for quality-based services that use information technology (Gerke and Tamm 2009 ). These characteristics apply to smart services, which is why the framework is considered adequate.

The service lifecycle of the current version from 2011 consists of five phases. In the first phase, the process objective is defined. Based on customer requirements, a service strategy is developed, and the necessary capabilities are defined. A more theoretical view of smart services discusses business alignment due to this kind of services. The second phase, namely service design , uses a predefined strategy to design services. The phase considers all articles that propose new smart services as a whole, i.e. infrastructures, service platforms, or related necessary aids. Deployment of the designed services is covered in the service transition phase, describing the way in which a new or changed smart service is implemented. Descriptions of a concrete implementation within a use case are included. The fourth phase is the service operation phase; this phase contains failure management, maintenance, and the execution of tasks and processes. Publications describing challenges and requirements during the use phase of a service are included. The final phase of the service lifecycle is continual service improvement . Learning from past successes and failures is a key component of this phase. This phase also describes how to continually adapt a service, use its pertinent data and information, and involve the customers. Figure 1 illustrates the described service lifecycle transferred to smart services.

Smart service lifecycle following the ITIL framework

Research design

The research design for this study includes two components: identifying relevant literature and analyzing it. The first part describes how the comprehensive and broad literature search is conducted. The second part presents how the identified literature is analyzed. The research design enables to review existing contributions to obtain a comprehensive overview of the status quo.

Identifying relevant literature

To find relevant literature that focuses on smart services, a systematic search was performed. To ensure a structured and broad overview, the approach by Webster and Watson ( 2002 ) was chosen as the underlying methodology. According to Vom Brocke et al. ( 2009 ), validity and reliability are essential components of a rigorous literature search. In general, validity is defined as the degree of accuracy, and, for a literature review, the validity is regarded as the degree to which all publications relevant to a topic are discovered (Vom Brocke et al. 2009 ). For this study, the validity of the literature search was considered by examining the selected databases, the predefined search terms, the performance of forward and backward searches, and the use of the TSISQ (Koukal et al. 2014 ). The TSISQ uses the concept of latent semantic indexing and is an extension of conventional term-matching methods. Reliability is generally understood to be the formal precision of a scientific study. In the case of a literature search, reliability is the replicability of the search process; thus, it is necessary to comprehensively document the search process (Vom Brocke et al. 2009 ).

Searches were carried out in the following eight databases: ACM, AISeL, Emerald Insight, IEEEXplore, InformsOnline, JSTOR, Science Direct, and SpringerLink. These databases provide articles from the most important outlets in the ISR field and yield different rankings, such as the VHB-JOURQUAL3 ranking. A search was not only carried out for the term “smart service” but also for digital and electronic services; The latter two terms have sometimes been used as synonyms for smart services, especially in earlier publications. To summarize, the three predefined search terms were as follows:

“smart service” OR “smart services”

“digital service” OR “digital services”

“electronic service” OR “electronic services” OR “e-service” OR “e-services”

A search was performed in the listed databases to determine whether a publication contained at least one of the search terms in the title or abstract. For SpringerLink and InformsOnline, it was not possible to specify the criteria in the search field; therefore, a full-text search was conducted on these databases. There were 25,056 hits in total from all the databases.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined to identify the most relevant articles. Publications that were non-academic articles or not peer-reviewed were filtered out. However, to be sure of achieving a broad literature review, the search was not limited to high-ranking journals and conferences. According to Webster and Watson ( 2002 ), a topic-centric view of the literature is much more valuable than a view limited to a few top journals. Articles that were not written in English were excluded, which is why only English search terms were used to identify relevant literature. It was assumed that potentially relevant articles in the field of smart services would be in English because most researchers write in English, aiming to address a broad target group. To avoid regional overrepresentation of research in the formal analysis, articles in other languages were excluded. This choice also helped avoid regional bias based on differences in research topics. After implementing the named inclusion and exclusion criteria, 10,012 potentially relevant hits remained. In this literature review smart services are viewed from an ISR perspective. Articles in different disciplines such as history or art were excluded. This criterion was applied by using the filters whenever possible while searching the different databases and disciplines. A publication by Bianchi ( 2015 ), which includes a discussion of the roles of risks and trust in art exchanges, is an example of an article that was not from the ISR field and thus excluded. Additionally, articles that only used the terms smart/digital/electronic service, without subsequently focusing on these topics, were not considered. One example is a technical analysis and presentation of strategies for network scenarios (Sohn and Gwak 2016 ).

Most of the articles were found using second and third search terms; that is, they contained the terms “digital” or “electronic”, but not “smart”. The definition of smart services presented earlier was used to determine whether an article was using the terms “digital service” or “electronic service” as a synonym for smart services. Implementing this criterion led to a large reduction in potentially relevant articles, because most of the articles that used the second and third search terms did not consider “smart” services in accordance with the definition presented in this article. Appendix Table 4 shows the number of hits and their reduction for each search term in the different databases. If it was not possible to decide whether the terms used in an article complied with the definition of smart services considered in this article, the full text was examined. An article by Mecella and Pernici ( 2001 ) is an example of a hit using the search term “electronic service” that was eventually excluded. They define electronic services as open, developed for interaction in an organization and between organizations and as easily composable. Using this definition, electronic services are not necessarily based on context information or data analytics.

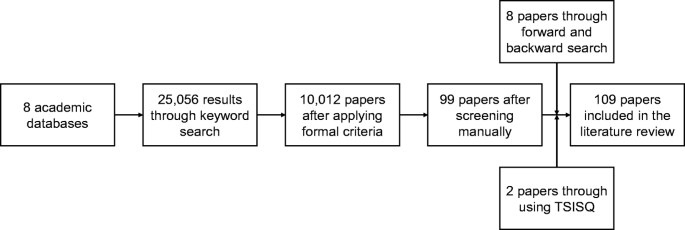

Following the search described above, both a backward and a forward search were conducted (Webster and Watson 2002 ). For the backward search step, the citations of the articles were screened manually for additional relevant literature. Google Scholar was used for the forward search to find articles that cited the identified literature, resulting in seven additional articles. Finally, the literature tool TSISQ (Koukal et al. 2014 ) was used to enhance the keyword-based search via latent semantic indexing. The tool compares unstructured texts and identifies semantically similar texts in a database. The database contains IS literature from the “AIS basket of eight” and other IS conferences and led to the identification of two further articles. In total, 109 articles were considered in the literature review. Figure 2 illustrates the literature search process.

Literature search process

Analyzing the identified literature

In the second phase of the literature review an analysis of the identified articles was conducted, involving the following steps: identifying relevant aspects and issues, categorizing them and discussing the highlights and results. First, a formal exploration of the 109 articles was conducted. The years of publication were examined to identify a possible trend. The identified industries used as context were also determined. Next, the articles were analyzed thematically. The smart service lifecycle explained in section two was used to identify the phases covered by each article. During analysis, it was found that considering the service lifecycle is helpful for organizing the relevant publications. Associating research with a specific lifecycle phase enabled to draw more concrete conclusions and to better understand the opportunities and challenges. For each article in the literature review, it was determined which phases of the smart service lifecycle were covered. The service lifecycle is also relevant in practice. Niemann et al. ( 2009 ) indicated that a given topic must be examined at multiple points in the smart service process. All existing publications focus on specific lifecycle phases but do not consider the entire lifecycle. The considered topics were also analyzed. In the different phases it is focused on different topics. As not all articles identified can form part of the findings section, publications are selected that, in total, represent the diversity of research results.

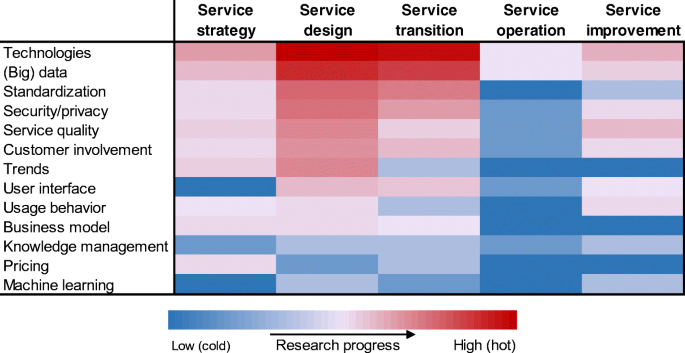

Based on the categorizations, a heat map was created to show the number of articles published for each topic and lifecycle phase. The heat map formed the basis for a discussion of important research fields. As a result, research gaps were identified that form promising areas for further research.

Based on the 109 identified publications, both a formal and a content analysis were conducted. The formal analysis provides a first insight into the publications covering smart services. The publications were then categorized based on the phases of the smart service lifecycle that they covered and the topics they considered. This forms the basis for the subsequently developed heat map and the discussion of research gaps.

Categorization of the literature

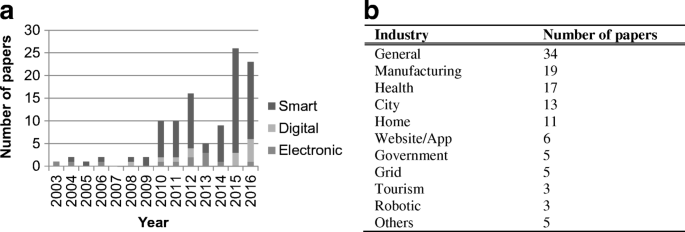

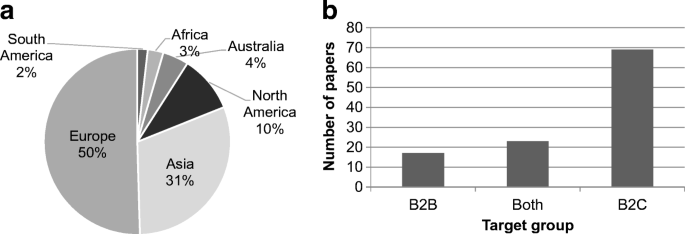

The issue of smart services was first mentioned in the literature in 2003 (Fig. 3 a). Initially, the term “electronic service” emerged for individual and interactive services. One year later, the term “smart service” appeared for the first time in the literature and finally became widely established in 2010. For three years, the interest was constant or growing. Although research in this field declined temporarily, it reached a new peak during the past years.

a Years of publication. b Research contexts

There is no outlet that concentrates publications dealing with smart services. Considering the outlets that researchers chose more than once (Appendix Table 5 ), conferences are the most common. The research context is also broad. Smart services are most often discussed in literature in the fields of manufacturing and healthcare. The topics of smart cities and smart homes also occur frequently. General approaches that do not specialize in a specific industry are also common (Fig. 3 b). An overview of the industries considered by each publication is presented in Appendix Table 6 . Details on the origins of the first authors and the target groups can be found in Appendix Fig. 5 . The identified publications were categorized according to the phase of the smart service lifecycle that they represent (Table 1 ). The design and the transition phases were the most frequently considered parts of the service lifecycle. To date, little research has been done in the field of smart service operation.

After assigning the publications to the relevant phases of the service lifecycle, the publications were categorized according to their focus. These topics were not predefined but were derived continuously throughout the literature review. In total, 13 topics were identified (Table 2 ), and each article was reviewed to determine whether it covered each topic. Each article focuses on at least one of the key topics.

Smart service strategy

In total, 25 articles deal with the strategic level of smart services; this number is relatively low compared to the later phases of the smart service lifecycle. Discussions about the most suitable technologies and how to include them in the strategy occurred in eleven articles (e.g., Ferretti and D'Angelo 2016 ; Perera et al. 2014 ). Six different risk types in the context of technology-based service innovations, namely privacy, functional, financial, psychological, temporal and social risks revealed challenges (Paluch and Wünderlich 2016 ). Interviews with both providers and customers enabled to identify the most important risks. From a provider’s perspective, it is privacy risks while functional risks are named most frequently by customers.

The eight articles (e.g., Smith et al. 2016 ; Tien 2012 ) that considered data during the strategy phase suggested that data represent a key factor in providing smart services. Using remote maintenance services as an example, real-time data are necessary to make such services possible. Looking at technologies, they should support data collection (Holgado and Macchi 2014 ).

The context in which a smart service is provided is a key ingredient for satisfying customer demands (Lee et al. 2012 ). The customer should be involved to find a strategy for satisfying individual needs (Spottke et al. 2016 ; Wang et al. 2012 ). A certain level of service quality contributes to customer satisfaction. The perception of service quality strongly impacts the probability that a service will be used again (Zo 2003 ). This is especially true when multiple services are interconnected (Wang et al. 2012 ).

Smart service design

In total, 59 articles examined the smart service design phase, covering a set of diverse topics. Service design should always be context-aware (Weijie et al. 2012 ). A design approach showed how to use industrial equipment for smart services (Priller et al. 2014 ). Considering existing production lines, the approach enables to make equipment smart to integrate it into the smart service world. A similar approach resulted in a platform as basis for smart mobile health services (Alti et al. 2015 ).

In contrast to the strategic phase, standardization, security and privacy concerns were frequently investigated. The dominant conclusion regarding standardization was that standards are necessary to combine and extend smart services and apply them to individual customer requirements. Open standards are necessary when designing new services (Kryvinska et al. 2008 ). Such standards enable a rapid and cost-effective development (Mihaylov et al. 2015 ). A model-driven approach that refers to several standards and contains different combined methods enabled the design of service systems (De Oliveira and Silva 2015 ). A case study showed applicability in practice.

A total of 14 articles (e.g., Gretzel et al. 2015 ; Roduner and Langheinrich 2010 ) highlighted the importance of security and privacy issues. Privacy is a fundamental challenge with respect to the concept of “smartness” (Cellary 2013 ). In the field of smart governance, the possibility of identifying any person at any time causes privacy problems. Therefore, rules and regulations regarding security and privacy are required for a successful smart service. Broadly, security is the primary concern regarding the Internet of Things technology (Keskin and Kennedy 2015 ). Therefore, it must be considered during the service design phase. The implementation of a maintained and frequently updated knowledge management helps to quantify security and privacy risks, e.g., through providing lists of risks for different situations or technologies (Moawad et al. 2015 ).

Eleven articles (e.g., Buchanan and McMenemy 2012 ; Yong and Hui-ying 2013 ) investigated how to involve the customer during the smart service design process. The importance of customer involvement is justified by the fact that value should be co-created (Wünderlich et al. 2012 ). A framework for user involvement helps to optimize the service design process (Gillig and Sailer 2012 ). A study enabled to develop the framework and shows that the customers must be analyzed from the beginning, e.g. regarding their role, activities and environment. For example, machine learning techniques are helpful to analyze the customers and to identify preferences (Abdellatif et al. 2013 ).

Although business models are changing through the Internet of Things (Keskin and Kennedy 2015 ), it is rarely a subject of discussion when investigating smart services. Pricing is only named one time as a fundamental design dimension of a comprehensive business model (Williams et al. 2008 ).

Smart service transition

In total, 40 publications focused on smart service transition. As in other lifecycle phases, technologies and big data received the most attention in the transition phase. Technology-based services generally have great potential (Paluch and Wünderlich 2016 ). Especially context-aware tools enable smart services and help to adapt them to individual customer needs (Pistofidis and Emmanouilidis 2012 ). The implementation of a robotic system for smart home-care services illustrated that openness and flexibility is a key for successful smart service technology (Ma et al. 2010 ).

The use of large datasets, e.g. in form of real-time data, provides great potential regarding the identification of individual customer needs (Lê Tuán et al. 2012 ). But when introducing a service based on big data, several challenges and potential problems must be carefully investigated (Al Nuaimi et al. 2015 ). It must be ensured that the foundations are laid to be able to transform different types of data into storable datasets (Li et al. 2015 ). Dynamic environments require robustness when collecting, transforming and storing big data (Al Nuaimi et al. 2015 ).

The user interface plays a central role in the academic literature and was mentioned six times (e.g., Mukudu et al. 2016 ; Oh et al. 2010 ) in discussions of the smart service transition phase. All researchers that dealt with this topic agreed that an intuitively operable user interface is a key component for interaction with the customer. An interactive user interface improves efficiency and simplifies smart service transition (Pao et al. 2011 ). It is important to understand both usage behavior and a customer’s preferences and needs to implement a suitable user interface (Seeliger et al. 2015 ).

Knowledge management only occurred twice (Chu and Lin 2011 ; Li et al. 2015 ) in this phase as a topic of discussion. Knowledge is a valuable asset when offering smart services and improves the efficiency of communication and coordination (Chu and Lin 2011 ). Smart services are knowledge-intensive and require consistent knowledge management (Chu and Lin 2011 ; Li et al. 2015 ); this management includes collecting, packaging, distributing and reusing knowledge (Ferneley et al. 2002 ). That is why a knowledge management portal is a precondition to create and realize innovative services. The idea is to use knowledge management to implement a learning culture within an organization. A medical knowledge recommendation service for patients functions as starting point for designing an information framework to enable knowledge management in the health sector (Li et al. 2015 ). A prototype shows how to implement such a framework in practice. Connected to knowledge management, little attention has been paid to machine learning techniques. Kamp et al. ( 2016 ) are the only authors who recommended conducting data analyses using machine learning techniques. During the service transition phase, machine learning can help to ensure the quality of the processes.

Smart service operation

Only five articles dealt with the service operation phase, which received the least amount of attention in the literature. The three articles (Chatterjee and Armentano 2015 ; Lee et al. 2010 ; Yachir et al. 2009 ) concerned with technologies agreed that technology which operates smoothly is essential for individual and dynamic smart services. Taking the healthcare sector as an example, a system for electronic health services that bases on the Internet of Things contributes to smooth operation (Chatterjee and Armentano 2015 ). Technology that is used for monitoring especially is important to guarantee the functionality of a smart service (Lee et al. 2010 ). A real-time monitoring system enables to process sensor data during service operation (Lee et al. 2010 ). Looking at technologies for data analyses, effective fault diagnosis in wireless sensor networks is important for a successful service operation (Hamdan et al. 2012 ). Abstraction of functionalities for heterogeneous devices is required in order to support interoperability for concurrency management and failure detection in whole systems (Baldoni et al. 2010 ). Scalability of large data handling during an operation based on the number of connected devices is necessary (Lee et al. 2010 ). To compose different smart services, several parameters must be considered. One of the most important parameters is the quality of services (Yachir et al. 2009 ).

Continual smart service improvement

In total, 19 articles address the requirement to continually improve smart services. Seven of these articles (e.g., Kwak et al. 2014 ; Yu 2004 ) focused on service quality. In addition to discussing the importance of service quality, recommendations help to understand how it can be determined. For example, a mathematical model can be used to estimate the quality of a service. An algorithm was developed using previously defined preconditions and determines whether these are fulfilled (Yachir et al. 2009 ). Another approach is the provision of a list of indices. They help to measure service quality based on considerations regarding the service provider, customer, and platform (Hong et al. 2014 ).

Four articles (e.g., Böcker et al. 2010 ; Kuebel and Zarnekow 2015 ) concluded that the usage behavior should be considered when improving smart services. A system should be able to learn from usage behavior (Kynsilehto and Olsson 2011 ). Knowledge management systems that integrate domain knowledge and human expertise (Wang et al. 2011 ) enable to detect, analyze and respond to the customer’s local environment and the usage behavior (Kynsilehto and Olsson 2011 ).

Discussion of research gaps and further research topics

The discussion of opportunities for further research consists of two parts. First, the research intensity along the different topics and lifecycle phases is summarized to get an overview of the role of smart services in the literature. Second, five specific fields are discussed to provide promising starting points for further research.

Research intensity in the field of smart services

The results indicate a growing interest in the topic of smart services in the ISR field since 2010. A heat map was created using the 109 articles analyzed in the literature review (Fig. 4 ). Each article was assigned to at least one area of the heat map, and each area describes a combination of a topic and a lifecycle phase.

Summary of research intensity

a Origins of first authors. b Target groups of smart services

The colors in the heat map represent the number of articles in an area. A detailed overview of the publications and their respective areas can be found in Appendix Table 7 . As demonstrated by the heat map, research intensity in the different areas is highly variable. In many areas (the cold areas), there is hardly any research. It is necessary to examine whether these are interesting for research, because it is not sensible to look at a specific topic in each lifecycle phase; or whether they are good starting points for further research. In contrast, other areas (hot areas) include many articles. For these areas, the question is whether more research is needed; in other words, whether the area has already been comprehensively explored, or if it is a diverse area where research is still required.

In the following discussion, it is focused on five specific fields that seem to be interesting for discussion (Table 3 ). Each field integrates several areas that belong together because they address the same topic or lifecycle phase. Both topics and lifecycle phases are considered in the discussion for their potential to provide promising starting points for further research. The fields represent all areas because hot areas, cold areas and areas between these two extremes are considered.

Technologies and (big) data as key enablers in the service design and transition phases

Most research on smart services was carried out in the fields of technology and big data, particularly in the design and transition phases. In addition to existing research, a classification that can recommend technologies when a specific service is designed would be an important contribution. A discussion of the advantages and challenges of the different technologies would also be an interesting topic for further research. The design phase has a more theoretical perspective, which is why general predictions would support a broader overview of technologies in the field of smart services. Technologies that are necessary for such services can be implemented and are already well covered in the literature. However, previous studies generally discussed a specific application (e.g., Ferretti et al. 2016 ; Ma et al. 2010 ). Further analysis of technologies in the transition phase in various contexts would contribute to a broader understanding of smart service implementations.

In the service transition phase, data play an essential role, since smart services are mainly based on data. Real-time data such as sensor data, were emphasized as being interesting for satisfying individual customer needs (Lê Tuán et al. 2012 ). Specific applications were discussed that are suitable for a specific industry, such as the health sector (e.g., Alti et al. 2015 ). Prototypes were developed for a specific application and predefined types of customers, such as private end users (e.g., Mukudu et al. 2016 ). Apart from a specific industry, a structured analysis of the role of data in the design phase is missing. An investigation into the different data types and their importance for different smart services would help to structure the current knowledge of data and data analyses. In the transition phase, special attention is given to concrete examples of the implementation. Taking a more general approach on how to implement smart services on the customer side under consideration of data streams might result in a general framework.

Considering the customer

Although a characteristic of smart services is that value is co-created via interactions between the service provider and the customer, the role of the customer in the literature has not been as well explored as would be expected. Research has addressed the question of how to involve the customer in the innovation process (e.g., Gillig and Sailer 2012 ) but customer involvement in the operation and improvement phases is relatively unexamined. While exploratory case studies have already indicated the importance of the customer (e.g., Wang et al. 2012 ; Spottke et al. 2016 ), general conclusions across different applications and industries are still missing. A systematic overview of the customer’s role across all lifecycle phases of a smart service would help those engaged in the practice to improve their processes. A theoretical framework presenting the role of the customer from a more general perspective would contribute to academic knowledge.

Another aspect regarding the customer’s role would be to measure and predict their behavior. Investigating in detail how usage behavior influences smart services in all phases of the lifecycle would provide a better understanding of smart services. It would also be interesting to investigate how usage behavior can be influenced by designing smart services in a specific way. Knowledge about usage behavior would also help to improve customizable user interfaces as the user interface is a critical element for enabling interactions between customer and provider (Tien 2012 ). One possible approach would be to determine critical success factors related to user interfaces. Systemizing the current knowledge of user interfaces in connection with smart services would enable practitioners to satisfy customer needs.

Knowledge management and machine learning to gain, preserve and use information

Little attention has been paid to knowledge management and machine learning. Knowledge permits the improvement of the provision of smart services and ensures that past problems and challenges do not persist in the future. Therefore, a knowledge base should be filled, maintained and used (Moawad et al. 2015 ). A systematic investigation of the role of knowledge management for smart services would contribute to academic research. Studies that compare different approaches would close the gap between theory and practice. Another starting point for further research is the investigation of the extent to which reliable knowledge management can be a success factor for smart services.

Machine learning uses data to continually optimize the services provided. It generally contributes to satisfying individual customer requirements (Abdellatif et al. 2013 ). The topic of machine learning is diverse and methods suitable for smart services have not yet been established. Researching machine learning in the context of smart services has the potential to uncover new opportunities and may lead to new business concepts. A possible approach is to investigate as to which extend established machine learning methods are suitable for smart services.

Putting smart services into money

As economic decisions are mainly strategic decisions, business models and pricing strategies are important in the first two phases of the smart service lifecycle. Notably, business models for smart services have rarely been discussed. Business models are changing through smart service systems (Keskin and Kennedy 2015 ), which is why more attention should be devoted to this topic. One reason for the lack of research into business models for smart services could be the fact that they are still under development (Lee et al. 2016 ). It is difficult to develop a business model without knowing the concrete services that will be provided. An investigation could be carried out to determine whether there are new aspects of a smart service business model that are absent in other business models. This could result in a business model framework for smart services. Although these are relatively general approaches, they help place such services in the context of whole business models.

Pricing strategies have been emphasized and are fundamental for smart service design (Williams et al. 2008 ). Identifying the best pricing model for a specific smart service is a key for the success. Nevertheless, pricing strategies are rarely discussed in the literature. Depending on the industry concerned, pricing strategies differ. However, the industry is not the only factor that can influence the optimum pricing strategy. The type of customer (i.e. private or business customer) and the corporate strategy also play a role. A systematic investigation of possible additional influencing factors would help to introduce smart services. Based on these factors, it is possible to develop a decision support system that can identify the optimum pricing strategy for a particular service.

Using smart services in practice

Few academic studies have discussed the phase of smart service operation. Technology and especially sensors have been identified as important tools for smooth operation (Hamdan et al. 2012 ). Investigating how to run faultless and smooth technical systems for smart services may provide interesting possibilities to connect theory and practice. Researching critical success factors of technologies is interesting both for researchers and smart service providers. A model focusing on the interplay of technologies and further elements such as big data contributes to a comprehensive overview of smart services. Going further in the direction of big data and data collection in real-time, their handling in different application areas in practice may lead to a better understanding of the variety of data and how to process and store them in databases.

The attention that is paid in the smart service operation phase to topics apart from technologies and data is smaller, there are virtually no publications. Some of these cold fields are interesting starting points for further research. An example would be case studies of how security and privacy concerns are considered during the operation phase. The gained knowledge might form the basis for further investigations regarding the role of security and privacy in practice. It might be interesting to find out whether this topic forms a large part when operating a smart service. In turn, this influences the research of security and privacy in the operation phase. The same applies to knowledge management and machine learning. Conducting case studies would provide a first insight in their use in practice. Depending on the findings further research can be conducted, e.g., regarding relevance, challenges and possibilities of machine learning and knowledge management when operating smart services.

Standardization is one example that may be of less interest regarding operation. Generally, standards are determined in the design and transition phases. Although they may be used in the operation phase, this topic has lower potential resulting in new knowledge.

Many topics concerning the customer also contain interesting avenues for further research. Studying usage behavior during the smart service operation phase would be a good basis for subsequent service improvement. Studies on how to track usage behavior could lead to interesting results. Such investigations should not stop at the point of collecting information about the usage behavior, though; appropriately using this information is also an important aspect. Therefore, the operation phase should not be considered in isolation but in connection with the phase of continual improvement.

Limitations

As a starting point for the literature search, three search terms were predefined; further search terms were not included during the search process. A second search process could be conducted using additional search terms identified during the literature analysis. Similarly, the literature identification process was limited to eight different databases. Although these databases were identified to be the most important ones in the ISR field, searching additional databases could have generated additional results. Additionally, only peer-reviewed articles published in journals or conference proceedings were included in the literature review; whitepapers and book chapters were excluded. Considering these types of publications could have also yielded further results. Next, only one of the search terms contained the word “smart”. The definition for smart services was derived based on the literature identified using this search term. Consequently, literature that did not use the words “smart service” but rather “digital service” or “electronic service” was examined to determine whether the use of the terms was consistent with the definition of smart services presented in this article. The decision to include articles resulting from the second and third search terms was based on manual analysis. Considering another definition of smart services could have led to other results. Finally, the 13 identified topics were not predefined; they were determined during the literature analysis phase to ensure that all relevant topics were considered. Five fields were selected as starting points for discussion and identification of research fields. The remaining fields would likely also have provided interesting avenues for further research.

Conclusions

The literature review presented in this study provides a broad, structured overview of research in the field of smart services. A systematic search led to 109 publications dealing with smart services in the ISR field. The research context of the resulting literature is diverse and reflects the applicability of smart services in several industries (e.g., manufacturing, health, city).

To provide a better overview, the articles were categorized based on the phases of the smart service lifecycle that they covered. Next, the publications were classified according to their thematic focus. During the literature analysis phase, 13 topics were defined based on the focus of the articles (e.g., technologies, (big) data, standardization). Each publication covered at least one of these topics. A summary in the form of a heat map demonstrated the research intensity of topics regarding smart services. Possible research gaps were identified from the heat map (e.g., measuring and predicting customer’s behavior, role of knowledge management, using established machine learning methods for smart services).

The fact that several publications may have covered the same topic and lifecycle phase does not necessarily mean that no more research is required. Research is still needed in certain fields of technology and data in the context of smart services, even though these topics have been frequently discussed. A general approach considering e.g. the roles and different functions of technology and big data is still missing. In past publications topics related to technologies and big data are rather discussed for a specific field or application. Part from looking at specific forms of smart services enables to take an overall view in order to deepen the global understanding. Nevertheless, it must be ensured that the approaches are not too shallow without providing added value.

The heat map shows that only a few topics have been a major focus of research. Although the importance of the customer’s role is undisputed in the literature, this aspect has rarely been examined. On the one hand it is postulated that focusing on the customer is the key for successful smart services. On the other hand, this importance is not reflected in the number of publications dealing with the customer in the context of such services. Especially looking at the customer during the operation phase might provide interesting insights that are helpful for smart service research. Taking a broader view, overall findings of how to involve the customer and considering the usage behavior across all phases of the lifecycle are not yet investigated. This is important because it does not have to be neglected that the better the customer and the customer’s behavior is understood, the better and more precise appropriate smart services can be provided.

Economic aspects, such as the development of business models or pricing strategies, have rarely been discussed in the literature. For providers it is valid that offering smart services is only reasonable if it is profitable. But how to identify profitability and examining which information is necessary to make a feasibility study is yet to be explored. Investigating in what sense known business models are changing through smart services helps to understand how they work in practice.

The research of knowledge management and machine learning in the field of smart services stands mostly at the very beginning. This is interesting because especially for this type of service data interpretation is important. Smart services are frequently adapted to meet the customer’s requirements. Knowledge gained from past events, employees and further sources enables to continually improve them. Machine learning enables to turn data into information what also contributes to continual improvement. As smart services are a relatively new development, best practice approaches are not yet established. Research that investigates suggestions of how knowledge management and machine learning for smart services can be designed is interesting both for theory and practice. Related to the design it is also necessary to investigate how to embed it into the different contexts.

Not only the thematic focus is limited to only a few topics, but there is also a clear focus along the lifecycle. While both the design phase and the implementation phase have been frequently discussed, the operation of smart services has been neglected. This phase seems to be more practice-oriented than the other phases which provides great potential for research. Case studies are an appropriate opportunity to gain an insight into what the most important topics in practice are. The results help to improve theoretically developed results, such as models or frameworks. Therefore, detailed investigations are useful to both theory and practice.