Advertisement

Hilary mantel , the art of fiction no. 226, issue 212, spring 2015.

Hilary Mantel was born Hilary Thompson in Hadfield, Derbyshire, a mill town fifteen miles east of Manchester. Her memoir, Giving Up the Ghost , chronicles a grim childhood in a working-class Irish Catholic family: “From about the age of four I had begun to believe I had done something wrong.” When she was seven, her mother’s lover, Jack Mantel, moved in with the Thompsons. “The children at school question me about our living arrangements, who sleeps in what bed. I don’t understand why they want to know but I don’t tell them anything. I hate going to school. Often I am ill.” Four years later, Jack Mantel and Hilary’s mother moved the family to Cheshire, after which Hilary never saw her father again. To quote once more from Giving Up the Ghost : “The story of my own childhood is a complicated sentence that I am always trying to finish, to finish and put behind me.”

Mantel graduated from the University of Sheffield, with a B.A. in jurisprudence. During her university years, she was a socialist. She worked in a geriatric hospital and in a department store. In 1972, she married Gerald McEwen, a geologist, and soon after, the couple moved to Botswana for five years, where Mantel wrote the book that became A Place of Greater Safety . The couple divorced in 1980, but in 1982 they married again, in front of a registrar, who wished them better luck this time.

All her life, Mantel has suffered from a painful, debilitating illness, which was first misdiagnosed and treated with antipsychotic drugs. In Botswana, through reading medical textbooks, she identified and diagnosed her own disease, a severe form of endometriosis. Since then, Mantel has written a great deal about the female body, her own and others’. An essay that begins with a consideration of Kate Middleton’s wardrobe and moves on to a discussion of the royal body generated so much controversy that (as she told the New Statesman ) “if the pressmen saw any fat woman of a certain age walking along the street, they ran after her shouting, ‘Are you Hilary?’ ”

Mantel’s early novels— Wolf Hall was her tenth novel, her twelfth book—reflect the grimness she describes from her childhood and share a bleak, dark humor. The two completed books of the projected Cromwell trilogy, Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies , are not without darkness, but considering their subject—the bloody rise and fall of Henry VIII’s chief minister—they are remarkably vivid on the pleasures of work, home, and ordinary happiness. Both were awarded the Man Booker Prize, making Mantel the first woman to win the prize twice. This winter, a stage adaptation, Wolf Hall, Parts One & Two , enjoyed a sell-out run in London; a Wolf Hall miniseries aired at the same time on the BBC. In February, Mantel was made a dame.

Over the three days we spent together, she was working like an impassioned college student, until three or four a.m., and even after a day in the theater seeing both plays back to back, followed by a late supper, she was ready to meet and talk in the morning at nine.

INTERVIEWER

You started with historical fiction and then you returned to it. How did that happen?

I only became a novelist because I thought I had missed my chance to become a historian. So it began as second best. I had to tell myself a story about the French Revolution—the story of the revolution by some of the people who made it, rather than by the revolution’s enemies.

Why that story?

I’d read all the history books and novels I could lay my hands on, and I wasn’t satisfied with what I found. All the novels were about the aristocracy and their sufferings. And I thought those writers were missing a far more interesting group—the idealistic revolutionaries, whose stories are amazing. There was no novel about them. I set about writing it—at least, a story about some of them—so I could read it. And of course, for a long time it seemed as if I were the only person who ever would. My idea was to write a sort of documentary fiction, guided entirely by the facts. Then, not many months in, I came to a point where the facts about a certain episode ran out, and I spent a whole day making things up. At the end of it, I thought, I quite liked that. It sounds naive, not knowing that I would have to make things up, but I had a great belief that all the material was out there, somewhere, and if I couldn’t find it, that would be my fault.

But the majority of human history is lost, isn’t it?

Yes, and when you realize that, then you can say, I don’t know exactly how this episode occurred, but, for example, I do know where and when it took place.

Would you ever change a fact to heighten the drama?

I would never do that. I aim to make the fiction flexible so that it bends itself around the facts as we have them. Otherwise I don’t see the point. Nobody seems to understand that. Nobody seems to share my approach to historical fiction. I suppose if I have a maxim, it is that there isn’t any necessary conflict between good history and good drama. I know that history is not shapely, and I know the truth is often inconvenient and incoherent. It contains all sorts of superfluities. You could cut a much better shape if you were God, but as it is, I think the whole fascination and the skill is in working with those incoherencies.

In containing the contradictions?

Exactly. The contradictions and the awkwardness—that’s what gives historical fiction its value. Finding a shape, rather than imposing a shape. And allowing the reader to live with the ambiguities. Thomas Cromwell is the character with whom that’s most essential. He’s almost a case study in ambiguity. There’s the Cromwell in popular history and the one in academic history, and they don’t make any contact really. What I have managed to do is bring the two camps together, so now there’s a new crop of Cromwell biographies, and they will range from the popular to the very authoritative and academic. So we will have a coherent Cromwell—perhaps.

When Raymond Carver wrote a story about Chekhov’s death, he invented details and a character. Janet Malcolm traced how subsequent biographies now include the character from his fiction. History grabbed him up.

Yes, and once you know that you are working with historians in that way, then you have to raise your game. You have a responsibility to make your research good. Of course, you don’t mean for these things to happen. In A Place of Greater Safety , Camille Desmoulins wonders why he was always running into Antoine Saint-Just. We must be some sort of cousins because I used to see him at christenings, he says. It’s now become a “fact” that they were cousins. Things get passed around so easily on the Internet. And fact becomes fiction and fiction becomes fact, without anyone stepping in to arbitrate and say, What are your sources?

You worked on A Place of Greater Safety , your first novel about the French Revolution, decades before it was published.

I started it when I was twenty-two, a year after university. That would be 1974. I wrote it in the evenings and on weekends. I did more of the research up front than I would have done at a later stage—luckily for me, because in spring of ’77, we went to live in Botswana, where there were no sources to speak of, as you can imagine. I had an intense few weeks before we went, when I said to myself, Get everything you haven’t got, because this is your only chance.

It was a strange life. I was living partly in Botswana and partly in the 1790s. I was intensely engaged with my French Revolution book. But I became a teacher by accident. I was roped in by local ladies to work on a volunteer project doing a few hours a week at a little informal school set up for teenage girls. From there, I went to teach at the local secondary school. I was twenty-five and my oldest pupils were older than I was. Their ages ranged from twelve to twenty-six. We tended to have twelve-year-old girls and eighteen-year-old boys in the same classroom, which is an explosive mixture. The institution was a highly unpleasant place. Frantz Fanon would have loved it—the extent of cultural alienation, the horrific forms that colonialism takes that one doesn’t detect at the time, the tensions. We had a number of teachers from Zimbabwe, who divided themselves by language—so the teachers who were Ndebele people simply didn’t talk to the Shona people. There was a teacher from West Africa who was treated like a leper by all the teachers from southern Africa. The only way they made common cause was by hating the Nigerian. The Indian staff didn’t bother with the African staff, and the African staff gave the Indians as hard a time as possible. Botswana is the size of France, so it was a boarding school with day pupils, but many of the children came from hundreds of miles away. And to them our little bush town was New York. There was the culture shock the children lived with, the distance from their families. And then there was the horrible, sexually predatory behavior, which, to my shame, I didn’t entirely see at the time. I only dimly perceived it. Both masters and boys preying on the girls. This was Botswana just pre-AIDS. I had only very limited means of detecting what was going on, and, if I did detect it, what on earth was I going to do about it? You know, those layers of corruption permeated every aspect of life. Yet one went along day to day, teaching George Eliot.

Did you a have a prescribed curriculum?

Yes, these children were sitting exams set, moderated, and marked in England. It’s very hard to teach Eliot when you have some pupils in your class whose vocabulary is around six hundred words, basic English. On the other hand, there were some children who were from a background where their English was more fluent, who were very capable of appreciating it on the linguistic level, though not on the cultural level. Imagine trying to explain, This is George Eliot, she’s writing in the nineteenth century. She’s writing about the eighteenth century and she’s not doing it very well. Try to explain fox hunting to a child who has never seen a fox, never seen a horse, never seen a hedge, never seen a green field, never seen snow. Yet in some ways they responded to the fierce morality. They cast it in terms of their own morality. We didn’t have television, and obviously we didn’t have theater. So you were teaching literature to people who had none of the familiar means of forming a picture of the outside world. Teaching Shakespeare in Botswana was difficult, you’d think, but again they loved it. I never told them it was supposed to be difficult. I got good results, I have to say. I suppose I threw myself into it—you know, I didn’t have the world weariness of the other teachers. Then some unpleasant incidents drove me out of the school.

What happened?

I was on evening duty, and somebody jumped on me. It wasn’t a sexual thing. There were a group of pupils, with one person hitting me. Compared to what could have happened, it was trivial. It was dark, they were not my pupils, I couldn’t identify them, the school wasn’t interested in finding out. It was a shambles. I felt unsupported by the headmaster, and so I left, but I didn’t want to go, because I liked my pupils.

After I left the school, I just wrote.

Had you always wanted to be a writer?

Never. I didn’t think in terms of becoming a writer until I actually picked up my pen to become one. And that was born out of a feeling that my health was causing me problems. By the time I was nineteen, I knew there was something wrong but I didn’t have a diagnosis, I didn’t have any help, and I realized that doors were closing. I wasn’t going to be some of the things I thought I might be. The best thing I could do was to get a trade that was under my control. But then, when I looked back, I realized that even though I hadn’t said to myself as a child, I want to be a writer, I’d actually instituted a training course. I always wonder if other people’s lives have been like that, when they turn into writers. From the age of about eight, I was hyperconscious about what I read, and my reading was always analytical. I was never simply absorbing stories but always asking myself, How is this done? When I walked to school every morning, from the age of eleven to eighteen, I “did” the weather and I didn’t stop until I had one perfect paragraph. So I had a huge mental file of weather. When I wrote Every Day Is Mother’s Day , I picked a sentence from my mental file and dropped it into the book—it gave me great pleasure to do so. I didn’t worry about the ten thousand sentences that didn’t get used because they were all a means to an end. The point of the exercise was not to stop until I’d pinned it down precisely and had exactly the right word. It was all about style, not story. By the time I got into my teens, I had nothing to say, but I had a very good style in which to say it. When I studied law, it completely broke my style, because you have to write in a very prescribed and tight way. When I started writing my novel, I had to rebuild my style. As for my subject, the French Revolution was beyond anything I had to say about my own life. It was so much bigger than me. Bigger than anybody. But there wasn’t the possibility of writing any other book because I had none.

By December of ’79, I had finished A Place of Greater Safety , but I couldn’t sell it, I couldn’t get anywhere with it at all. I had twelve weeks leave in England before I was due to return to Botswana. I’d made initial contact with a publisher, who seemed interested, so that was my first port of call. And they turned the book down. Then I found myself in hospital. I was very ill, I had major surgery. As I emerged, something in me said, I don’t think you will sell this book. It wasn’t that I had lost faith in the book—because I never did—I just knew the impossibility of maneuvering from where I was. It was not a good time for historical fiction, and I knew from writing to agents and the dusty answers I got that even getting the book read was going to be impossible.

So I formed a cunning plan. I thought, I’ll write another novel. I’ll write a contemporary novel. That was Every Day Is Mother’s Day . I started it in Africa. I finished it in Saudi Arabia. At times I had very little sense of where I was going with it or whether there would be any profit or success at the end of it. It was written in the teeth of everything. It was an act of defiance—I thought, I’m not going to be beaten. I got an agent, I got a publisher, then I wrote the sequel. It wasn’t planned as two books. It was, for me, a way of getting a foot in the door. But once I had secured a contract, I just rolled up my sleeves and I set about Vacant Possession in a way that I’ve never worked before. I would write through the morning, Gerald would come home midafternoon, would have his siesta, and when he woke up, I would read him what I had written in the morning. I’ve never written like that since.

Gerald’s a geologist—did you train him to be a literary reader?

That wasn’t what I needed. It sounds horrible, but I needed a listening ear. I needed someone to write for, someone who wanted to know what would happen next.

Did you prefer historical fiction, even then? Or were they equal but different enterprises?

I have to be frank. Writing a contemporary novel was just a way to get a publisher. My heart lay with historical fiction, and I think it still does.

Though you went on to write quite a few contemporary novels.

Well, things changed. I realized that writing a contemporary novel wasn’t just a way in, it was a trade in itself. We returned to England from Saudi Arabia just as Vacant Possession was published. By then I had my mass of material from Saudi Arabia, which I knew I must use, because I had a unique opportunity. So again, that book, Eight Months on Ghazzah Street , demanded to be written. And by then I had the idea for Fludd , which had long been simmering in my mind.

During all that time you didn’t give your publisher A Place of Greater Safety . Why not?

Because I was absorbed in what I was doing. I thought, Just push on while the going’s good. Fludd was one of those books that came in an instant. You know, you’ve got the first sentence, you’ve got the last sentence. A thing like that can go off the boil. So again, I had a sense of urgency.

A lot of your subsequent themes emerged in those first two books—anorexia, diets, a drowned baby, an obsession with “the royals.”

The epigraph to Every Day Is Mother’s Day is Pascal—“Two errors; one, to take everything literally; two, to take everything spiritually.” And it’s the epigraph for the lot, isn’t it?

How did you go about writing Eight Months on Ghazzah Street ?

I kept diaries all the time, and I kept my notes. But there are a lot of problems with that novel. I think it’s too fuzzy. I don’t think I really crunched down on it. That was inexperience, and the distressing business of having to make things up. I always see that book through a dust haze, but I do remember the moment when, if it were another book, I’d say it crystallized, but being Eight Months on Ghazzah Street , it didn’t crystallize at all. We lived in the city center and one day I went up onto the roof of our apartment block, which was the only outside space available. I craned my neck and saw a crate on the neighbor’s balcony. I thought, My novel’s in that box. There was something incredibly sinister about it. And yet, what was it? It was a box. In my experience, those are the moments that set a novel. You just have to wait. Supposing I hadn’t gone up to the roof, what would the novel have been? I have no idea.

The odd thing about Ghazzah Street was that a lot of what I said proved to be pretty accurate when terrorist activity was exposed in Saudi Arabia. People were doing just what I said—they were stockpiling arms in little flats around the city.

I wrote Ghazzah Street , then I wrote Fludd , not very quickly actually, over a couple of years. By this stage, you see, I’d earned two thousand pounds from my first novel, and four thousand pounds from my second novel. For Ghazzah Street and Fludd , I got a two-book contract for £17,500—not enough to live on. It was at that point that I became a film critic. Then I became a book reviewer as well. I did one film review a week, several books reviews a month. I was an industry.

How could you do it? Did you become a fast reader?

Long hours. I don’t think I changed my reading speed. I take lots of notes. I might not have been the world’s most insightful reviewer, but I was an extremely conscientious one. Once I got the film column, I was highly visible, and I had more work coming in than I could handle. But I was making a living. I was solvent. And I felt I was building something. There’s something very seductive about opening a newspaper if your name is almost always in it. Every weekend, two papers, three papers. If you’re an un-networked person from nowhere, which is exactly what I was, then you realize that you’re drilling away into the heart of the cultural establishment.

Did the book reviewing make you see your own work within a context? Did you feel your novels were related to other schools of fiction?

No, to be honest, I never have. I think I’ve had a curve of development that was just mine. This is why, for so long, I made no money. Though I had a good reputation critically, I had very few readers because I wouldn’t find a formula and stick to it. Until the Cromwell novels, I had no identity in the mind of the reading public. It’s very hard for a publisher to market an author who doesn’t display any consistency in what she’s interested in or how she writes.

Ian McEwan jumps all over the map, doesn’t he?

I think he is more consistent in his preoccupations. You and I will know that my books are intimately connected, that there is coherence, but from a commercial point of view, they’ve not been an attractive package. And then there is the divide between contemporary fiction and historical fiction. When I began work on the French Revolution, it seemed to me the most interesting thing that had ever happened in the history of the world, and it still does in many ways. I had no idea how little the British public knew or cared or wished to know about the French Revolution. And that’s still the case. They want to know about Henry VIII.

So you feel readers’ interests are predominantly subject based.

Yes, the imagination is parochial. I couldn’t have picked anything less promising, from a commercial point of view, than the French Revolution.

How did A Place of Greater Safety get published, in the end?

It was because of a newspaper article. This was in 1992. I had four books out. I had my reviewing career. I wasn’t making a lot of money, but I was getting somewhere. And there was this monster book on the shelf. I hadn’t looked into it for years. I thought, What if it’s no good? Because if it is no good, then that’s my twenties written off. And it also means that I commenced my career with a gigantic mistake. But inside me there was still a belief that it would be published one day. And a friend of mine, the Irish writer Clare Boylan, rang me up and said she was doing an article for the Guardian about people’s unpublished first novels, and had I got one? I could have lied, but it was as if the devil jumped out of my mouth, and I said, Yes, I have! And of course she rang around a number of authors, and they were saying things like, Yes, I wrote my first novel at the age of eight, and I’ve still got it in a shoe box. I was the only person who actually wanted to see her first novel published. On my way to deliver it to my agent, I had lunch with another novelist. The manuscript was a huge parcel under my chair—unwelcome, like a surprise guest. We should have given it a chair to itself. He said, Don’t do it.

You were twenty-seven when you’d written it and now you were forty.

Something like that. A lot of things had happened in French Revolution scholarship since then. The bicentenary had come and gone, and there had been a revolution in feminist history. When I read my draft, I saw that the women were wallpaper. There had been no material. Today you would think, Well, I must invent some, then. At the time I hadn’t seen the need—I hadn’t thought the women were interesting. My life was more like the life of an eighteenth-century man than like the life of an eighteenth-century woman. And I suppose I didn’t really ask myself the questions. Now I thought, I’ve got to work this harder.

How long did you take to revise?

I did it in the course of one summer. The publication process was horrendous. Basically, the novel was written in the present tense. Someone in the publishing house didn’t want that, so changed it, and I changed it back, and so on, through proofs. The result was that, if you look at the book now, there are paragraphs where two tenses are employed. One day I’m going to straighten it out. But the work I had to do in those weeks was brutal, because I had to revise on a schedule. I worked immensely long hours. Something in me was never quite the same after that. It would be romantic to say that summer was the making of me, but it actually wasn’t like that. It brutalized me. I’m not sure if I can really express it, but it was after that, I shut down. I shut down such a lot of my life in order to do it, and never opened up again.

Do you mean you entered a level of isolation for the work, or restriction? A deeper commitment?

Restriction, yes. I think it’s good for me as a writer. I don’t think it’s very good for me as a human being. A sort of grimness entered into me, I think, which is still there. I suppose that book always was more important to me than anything else.

It was the book, until the Cromwell books.

Yes. It was me doing what I do. And I think, for better or worse, it’s me doing what only I could do. Nobody else works by this method, with my ideal of fidelity to history. Regardless of whether that’s a good thing, or gets good results, it is a thing I do.

You said you withdrew from life. What did you eliminate?

Friends. Personal relationships. Fun. Everything just went. I don’t think I had many close friends before, but it seems to me that after that summer I never relaxed again. And the only people who could be my friends were people who were enormously tolerant of my really not being there for months at a time. Because of my health, my energy has always had to be harvested, preserved, and directed at work. And then if there was any left over, fine, but usually there wasn’t. I never lived in London, so I didn’t hang out with literary people in my off-duty hours. I was not isolated, though, from other writers. Instead of going to literary parties, I went to committees. I sat on the Council of the Royal Society of Literature, on the management committee of the Society of Authors. For six years I sat on the Advisory Committee for Public Lending Right, which advised the government on giving authors an income from books borrowed from libraries. That was my involvement in the literary world. It was technical, if you like. It was useful work, but most people would have regarded it as extremely dull.

Did you have friends who were helpful with the work itself?

I’m going to say no, on the whole. Gerald is my first reader, but I don’t expect literary criticism from him. He’s not going to say, Oh, that reminds me of something in Muriel Spark. He’s going to react as a human being to it. And isn’t that what we want?

I have other people I hold in mind as I write, to whom I might show something at an early stage. A fan who became a friend, Jan Rogers—she was a BBC producer, and it was she who got me writing for radio. She is knowledgeable about revolutionary history, she got me more deeply into Irish history, and she woke me up to literary theory. I have a friend called Jane Haynes, a psychotherapist—that’s another strand of interest.

I don’t really talk about writing very much to other writers. There’s one writer—Adam Thorpe. Adam lives in France and I never see him, but if he were to walk in, we’d have a proper conversation. It would be about writing. And I think he’s the only person I have that kind of relationship with, and I haven’t heard from him for months.

I keep a big correspondence going with Mary Robertson, whom my Cromwell books are dedicated to. I write to Mary almost every week, sometimes far more often.

How did you become friends?

Some years ago, probably fifteen years ago, I was invited to the Huntington Library, to a conference along with Martin Amis, Ian McEwan, Christopher Hitchens—the lads, you know. I casually mentioned to a woman there that I was thinking of writing something down the line about Thomas Cromwell. And she said, When you do, we have a woman here you need to meet. I thought no more of it until the time came, then I said, You have a woman, I believe. And therein we fell into correspondence—very tentatively at first. Mary had long ago written a Ph.D. thesis on Thomas Cromwell’s ministerial household. She’d also written a couple of papers on his property holdings. But she had not really asked herself what this man was like, because that was not her job.

What was your correspondence like?

Luminous. I didn’t really ask her questions. I’d bounce suggestions off her. I’d say, I’ve come across this and my thought about it is that. What if I were to speculate? Would you see anything against it? Is this really a gap in the record? Or is it just something that I personally don’t know? Her interest and knowledge were there, ready to be revived.

Want to keep reading? Subscribe and save 33%.

Subscribe now, already a subscriber sign in below..

Link your subscription

Forgot password?

Featured Audio

Season 4 trailer.

The Paris Review Podcast returns with a new season, featuring the best interviews, fiction, essays, and poetry from America’s most legendary literary quarterly, brought to life in sound. Join us for intimate conversations with Sharon Olds and Olga Tokarczuk; fiction by Rivers Solomon, Jun'ichirō Tanizaki, and Zach Williams; poems by Terrance Hayes and Maggie Millner; nonfiction by Robert Glück, Jean Garnett, and Sean Thor Conroe; and performances by George Takei, Lena Waithe, and many others. Catch up on earlier seasons, and listen to the trailer for Season 4 now.

Suggested Reading

“It is several years since this dinner, and I remember best the taste of persimmons soaked in muscadet.”

Dinner Parties

The art of fiction no. 86.

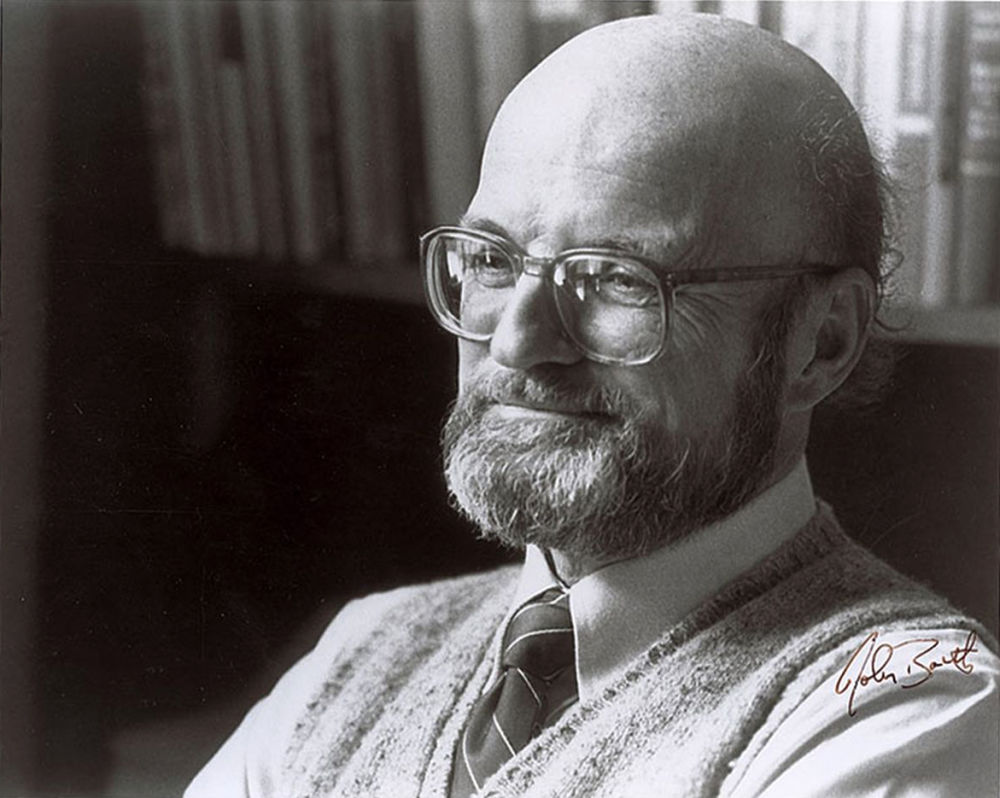

This interview with John Barth was conducted in the studios of KUHT in Houston, Texas, for a series entitled The Writer in Society . The stage set was made up to resemble a writer’s den—the decor including a small globe of the world, bronze Remington-like animal statuary, a stand-up bookshelf with glass shelves on which were placed some potted plants and a haphazard collection of books, a few volumes of the Reader’s Digest condensed novel series among them. Large pots of plants were set about. Barth sat amongst them in a cane chair. He is a tall man with a domed forehead; a pair of very large-rimmed spectacles give him a professorial, owlish look. He is a caricaturist’s delight. He sports a very wide and straight mustache. Recently he had grown a beard. In manner, Barth has been described as a combination of British officer and Southern gentleman.

“We’ll have to stick to the channel,” he wrote in his first novel, The Floating Opera , “and let the creeks and coves go by.” Every novel since then has been a refutation of this dictum of sticking to the main topic. He is especially influenced by the classical cyclical tales such as Burton’s Thousand and One Nights and the Gesta Romanorum , and by the complexities of such modern masters as Nabokov, Borges, and Beckett. For novels distinguished by a wide range of erudition, invention, wit, historical references, whimsy, bawdiness, and a great richness of image and style, Barth has been described as an “ecologist of information.”

Of his working habits Barth has said that he rises at six in the morning and puts an electric percolator in the kitchen so that during the course of sitting for six hours at his desk he has an excuse for the exercise of walking back and forth from his study to the kitchen for a cup of coffee. He speaks of measuring his work not by the day (as Hemingway did) but by the month and the year. “That way you don’t feel so terrible if you put in three days straight without turning up much of anything. You don’t feel blocked.”

This interview, being restricted to a half-hour’s conversation for a television audience, was thought to be a bit short by the usual standards of the magazine. It was assumed that Barth, being such a master of the prolix, would surely make some additions. Extra questions were sent him. The interview was returned to these offices with the questions unanswered, and the text of the interview edited and shortened. Perhaps Barth had not noticed the additional questions. This interview was sent back, this time with a small emolument attached for taking the trouble. The interview was returned once again, along with the uncashed check, with the following statement: “It doesn’t displease me to hear that our interview will be perhaps the shortest one you’ve run. In fact, it’s a bit shorter now than it was before (enclosed). Better not run it by me again!”

When were the first stirrings? When did you actually understand that writing was going to be your profession? Was there a moment?

It seems to happen later in the lives of American writers than Europeans. American boys and girls don’t grow up thinking, “I’m going to be a writer,” the way we’re told Flaubert did; at about age twelve he decided he would be a great French writer and, by George, he turned out to be one. Writers in this country, particularly novelists, are likely to come to the medium through some back door. Nearly every writer I know was going to be something else, and then found himself writing by a kind of passionate default . In my case, I was going to be a musician. Then I found out that while I had an amateur’s flair, I did not have preprofessional talent. So I went on to Johns Hopkins University to find something else to do. There I found myself writing stories—making all the mistakes that new writers usually make. After I had written about a novel’s worth of bad pages, I understood that while I was not doing it well, that was the thing I was going to do. I don’t remember that realization coming as a swoop of insight, or as an exhilarating experience, but as a kind of absolute recognition that for well or for ill, that was the way I was going to spend my life. I had the advantage at Johns Hopkins of a splendid old Spanish poet-teacher, with whom I read Don Quixote . I can’t remember a thing he said about Don Quixote , but old Pedro Salinas, now dead, a refugee from Franco’s Spain, embodied to my innocent, ingenuous eyes, the possibility that a life devoted to the making of sentences and the telling of stories can be dignified and noble. Whether the works have turned out to be dignified and noble is another question, but I think that my experience is not uncommon: You decide to be a violinist, you decide to be a sculptor or a painter, but you find yourself being a novelist.

What was the musical instrument you started out with?

I played drums. What I hoped to be eventually was an orchestrator—what in those days was called an arranger. An arranger is a chap who takes someone else’s melody and turns it to his purpose. For better or worse, my career as a novelist has been that of an arranger. My imagination is most at ease with an old literary convention like the epistolary novel, or a classical myth—received melody lines, so to speak, which I then reorchestrate to my purpose.

What’s first when you sit down to begin a novel? Is it the form, as in the epistolary novel, or character, or plot?

Different books start in different ways. I sometimes wish that I were the kind of writer who begins with a passionate interest in a character and then, as I’ve heard other writers say, just gives that character elbowroom and sees what he or she wants to do. I’m not that kind of writer. Much more often I start with a shape or form, maybe an image. The floating showboat, for example, which became the central image in The Floating Opera , was a photograph of an actual showboat I remember seeing as a child. It happened to be named Captain Adams’ Original Unparalleled Floating Opera , and when nature, in her heavy-handed way, gives you an image like that, the only honorable thing to do is to make a novel out of it. This may not be the most elevated of approaches. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, for example, comes to the medium of fiction with a high moral purpose; he wants, literally, to try to change the world through the medium of the novel. I honor and admire that intention, but just as often a great writer will come to his novel with a much less elevated purpose than wanting to undermine the Soviet government. Henry James wanted to write a book in the shape of an hourglass. Flaubert wanted to write a novel about nothing . What I’ve learned is that the muses’ decision to sing or not to sing is not based on the elevation of your moral purpose—they will sing or not regardless.

What was in your way that you had to get out of your way?

What was in my way? Chekhov makes a remark to his brother, the brother he was always hectoring in letters, “What the aristocrats take for granted, we pay for with our youth.” I had to pay my tuition in literature that way. I came from a fairly unsophisticated family from the rural, southern Eastern Shore of Maryland—which is very “deep South” in its ethos. I went to a mediocre public high school (which I enjoyed), fell into a good university on a scholarship, and then had to learn, from scratch, that civilization existed, that literature had been going on. That kind of innocence is the reverse of the exquisite sophistication with which a writer like Vladimir Nabokov comes to the medium—knowing it already, as if he’s been in on the conversation since it began. Yet the innocence that writers like myself have to overcome, if it doesn’t ruin us altogether, can become a sort of strength. You’re not intimidated by your distinguished predecessors, the great literary dead. You have a chutzpah in your approach to the medium that may carry you through those apprentice days when nobody’s telling you you’re any good because you aren’t yet. Everything is a discovery. I read Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn when I was about twenty-five. If I had read it when I was nineteen, I might have been intimidated; the same with Dickens and other great novelists. In my position I remained armed with a kind of “invincible innocence”—I think that’s what the Catholics call it—that with the best of fortune can survive even later experience and sophistication and carry you right to the end of the story.

From the Archive, Issue 95

Subscribe for free: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music

Make a gift to PBS NewsHour’s global reporting

and your donation will be doubled by the Dorney-Koppel Foundation!

A look at the literary legacy of Hilary Mantel

Jeffrey Brown Jeffrey Brown

Anne Azzi Davenport Anne Azzi Davenport

Alison Thoet Alison Thoet

Leave your feedback

- Copy URL https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/a-look-at-the-literary-legacy-of-hilary-mantel

Hilary Mantel died Thursday at age 70 near her home in Exeter, England. She authored 17 books, but it was her trilogy of historical fiction based on the life of Thomas Cromwell and King Henry VIII that brought her worldwide fame and acclaim. Here’s an excerpt of a 2015 conversation between Mantel and Jeffrey Brown as part of our arts and culture series, "CANVAS."

Read the Full Transcript

Notice: Transcripts are machine and human generated and lightly edited for accuracy. They may contain errors.

Judy Woodruff:

Hilary Mantel authored 17 books, but it was her trilogy of historical fiction based on the life of England's Thomas Cromwell and King Henry VIII that brought her worldwide fame and acclaim.

Mantel died yesterday at age 70 of a stroke at a hospital near her home in Exeter, England.

The "NewsHour"'s Jeffrey Brown sat down with Mantel in 2015. At the time, she had published the first two novels of the trilogy, "Wolf Hall" and "Bring Up the Bodies." The former was being adapted for both a PBS television series and for the Broadway stage.

Here's an excerpt of their conversation. It's part of our arts and culture series, Canvas.

Jeffrey Brown:

Hilary Mantel and her historic characters are seemingly everywhere.

Hilary Mantel, Author, "Wolf Hall": The ever-expanding Henry VIII.

Hilary Mantel:

With his six wives. No one else has a ruler with six wives, who cuts the heads off two of them. So, you're off to a flying start there.

Mantel's novels "Wolf Hall" and its sequel, "Bring Up the Bodies," have been an international sensation, with more than four million books sold in 37 languages. She won the prestigious Man Booker Prize twice, a first for a woman.

It's a familiar story in many ways, the momentous reign in the 1500s of the Tudor King Henry, played on television by Damian Lewis, basking in power, but needing a male heir, cutting loose one wife in favor of the young Anne Boleyn, only to cut her head off when no son is produced.

But Hilary Mantel has told the story in a new way, giving the lead role to Thomas Cromwell, played by Mark Rylance. Cromwell has long been cast as the heavy, a shadowy cruel schemer, especially as compared to his great rival, Thomas More. Mantel's Cromwell is certainly clever and scheming, but he's also charming and urbane.

Thomas Cromwell, son of a blacksmith, who rose to be the king's right-hand man and eventually earl of Essex.

And my question is simple: How do you do that? What kind of a man in that hierarchical, structured society can break through all the social layers, all the factors stacked against him, and climb so high? And what is the price?

You looked at the history and you said, this is wrong, the way he's been portrayed?

I thought it was a lot more complicated and nuanced than the popular picture of Cromwell. I wanted to put the spotlight on him. And I wanted to ask my reader, or our audience, well, what would you do if you were him? Just walk a mile in his shoes, and then see what you think.

Mantel says she grounded her fiction in years of research.

I think that an imaginative writer for stage or novel has a — still has a responsibility to their reader, and that responsibility is to get the history right.

You want to do that?

Absolutely. That's the absolute foundation of what I do.

I begin to imagine at the point where the facts run out. But, like a historian, I'm working on the great marshy ground of interpretation.

Which historians do, but also, you're saying, novelists?

Exactly. We all share the same sources. We share the same facts. The question is, where do we stand to view them?

I sometimes think back, though, to the day when I began, because it's very vivid in my mind, writing the first paragraph, and having that feeling, by the time I was halfway down the first page, this is the best thing you have ever done. I was walking around with a big grin: Do you want to see my first page?

From that first page to the very last one, Hilary Mantel completed her famed trilogy in 2020 with the novel "The Mirror and the Light."

Listen to this Segment

Watch the Full Episode

In his more than 30-year career with the NewsHour, Brown has served as co-anchor, studio moderator, and field reporter on a wide range of national and international issues, with work taking him around the country and to many parts of the globe. As arts correspondent he has profiled many of the world's leading writers, musicians, actors and other artists. Among his signature works at the NewsHour: a multi-year series, “Culture at Risk,” about threatened cultural heritage in the United States and abroad; the creation of the NewsHour’s online “Art Beat”; and hosting the monthly book club, “Now Read This,” a collaboration with The New York Times.

Anne Azzi Davenport is the Senior Producer of CANVAS at PBS NewsHour.

Support Provided By: Learn more

Support PBS NewsHour:

More Ways to Watch

- PBS iPhone App

- PBS iPad App

Educate your inbox

Subscribe to Here’s the Deal, our politics newsletter for analysis you won’t find anywhere else.

Thank you. Please check your inbox to confirm.

Advertisement

Supported by

What to Read by (and About) Hilary Mantel

Mantel’s body of work spanned memoir, short stories, essays — and, of course, historical fiction. Here’s a guide to her writing.

- Share full article

By The New York Times Books Staff

The British novelist Hilary Mantel, who died on Thursday at age 70, left a wide-ranging and hard-to-classify body of work that encompassed memoir, story collections, contemporary novels and brilliant, querulous literary essays. But she was most celebrated for her work as a historical novelist, covering subjects from the French Revolution to the Protestant Reformation — especially in her Wolf Hall trilogy, about Thomas Cromwell’s role as Henry VIII’s chief fixer and enforcer. Writing with her usual spiky language and rich immediacy of detail, she reinvigorated a genre that had long been ridiculed as “relentlessly uncontemporary and easy to caricature, filled with mothballed characters who wear costumes rather than clothes, use words like ‘Prithee,’” as the novelist Jonathan Lee wrote in a recent essay .

Mantel won the Booker Prize twice — first for “Wolf Hall,” which, as our critic Janet Maslin wrote, “turned the phlegmatic villain Thomas Cromwell into the best-drawn figure and easily mixed 16th-century ambience with timeless bitchery” — and then for its sequel, “Bring Up the Bodies.”

Here is a selection of The New York Times’s coverage of Mantel over the years, along with some of her own writing for the newspaper.

Reviews of Her Work

Wolf hall (2009).

This fictional portrait of Henry VIII’s scheming aide Thomas Cromwell — the first volume of Mantel’s celebrated trilogy — won the Booker Prize in 2009. “‘Wolf Hall’ has epic scale but lyric texture. Its 500-plus pages turn quickly, winged and falconlike,” Christopher Benfey wrote in his review.

Bring Up the Bodies (2012)

The second installment in the trilogy, this book finds Cromwell coping with Henry VIII’s tumultuous marriage to Anne Boleyn as Jane Seymour rises in the king’s estimation. “The wonder of Ms. Mantel’s retelling is that she makes these events fresh and terrifying all over again,” Janet Maslin wrote in her review.

The Mirror and the Light (2020)

The “triumphant capstone” to the series, as our former critic Parul Sehgal called it, begins in 1536, with the 50-year-old Cromwell “rich beyond all his imagining and very much alone.” In order to finish the 800-page book, Mantel imposed a “punishing schedule” on herself, Alexandra Alter wrote in a 2020 profile , and afterward decided that “she’s done with historical fiction and plans to focus on writing plays.”

Mantel Pieces (2020)

This collection of work from The London Review of Books contains Mantel’s most incendiary essay, “Royal Bodies,” which compared Prince William’s wife, Catherine, to a plastic doll. Fernanda Eberstadt, who reviewed the book for us, wrote that “actually the essay’s most incendiary moment is when Mantel, at a Buckingham Palace reception, finds herself staring at the queen: ‘I passed my eyes over her as a cannibal views his dinner, my gaze sharp enough to pick the meat off her bones.’”

An Experiment in Love (1996)

Mantel’s seventh novel, and her second to be published in the United States, follows the adult Carmel McBain, who, in a “Proustian time-warp experience,” Margaret Atwood wrote in her review, falls down a rabbit hole of memories of her Catholic childhood and coming-of-age. “This is Carmel’s story,” Atwood wrote, “but it is that of her generation as well: girls at the end of the ’60s, caught between two sets of values, who had the pill but still ironed their boyfriends’ shirts.”

Giving Up the Ghost (2003)

Mantel’s memoir of her “tough childhood and a serious illness,” our reviewer said, “does not reassure. It scalds.” The eldest child of poor Irish Catholic parents living outside Manchester, Mantel suffered fevers and “the crippling tedium and unintelligible torments of a rough Catholic primary school,” and was separated from her father at a young age. When she was 20 doctors diagnosed her chronic pain as “a bad case of female overambition” — a decade later, she discovered it was endometriosis. “Hers are very vital ghosts,” our reviewer wrote. “What she has done is to invite us into their unquiet company.”

Learning to Talk (2022)

First published in Britain in 2003, the same year she published “Giving Up the Ghost,” this collection of stories echoes many of the preoccupations of that memoir, following children and adolescents in midcentury northwest England who are “at odds with their families, neighbors and schools,” our reviewer said, “striving to decipher the unspoken, and often hindered more than helped by cleverness and curiosity. … These stories hold worlds as wide as those of her longest novels.”

By the Book (2013)

In this interview, brimming with marvelous, craggy detail about writing and reading, Mantel told The Times that the best part of working on a book was “the moment, at about the three-quarter point, where you see your way right through to the end: as if lights had flooded an unlit road. But the pleasure is double-edged, because from this point you’re going to work inhuman hours, not caring about your health or your human relationships; you’re just going to head down that road like a charging bull.”

“ The ‘Wolf Hall’ Trilogy and the Allure of the Past ” (2020)

Shortly before “The Mirror and the Light” was published, Mantel spoke with The Times about the “Wolf Hall” trilogy. “Once those voices begin,” said Mantel, who had been fascinated by the life of Thomas Cromwell since she was a child, “it’s like having the radio on in the background for 15 years. It never actually fades.”

Mantel’s Essays for The Times

“ hilary mantel on taking her ‘wolf hall’ novels to the stage ” (2015).

What is it like for an author to shepherd her story onto the stage? In 2015, Mantel wrote about, as she put it, starting to “build a theater inside my head.” This is an account of how the “Wolf Hall” novels made it to Stratford-on-Avon, then to Broadway. As she wrote: “Snipped from the record, processed into a novel, recycled into script, sieved through 10 drafts, through 20, they stick because they’re the best words. The dead are speaking to us, hand on our arm.”

“I Taught Shakespeare in Botswana” (2012)

In 2012, Mantel contributed a tart, honest and witty essay about working as an English teacher in Botswana in the 1970s. She moved there with her geologist husband when she was 25, and she ended up in a classroom after another instructor failed to materialize. She wrote, “Today, my pupils from 1978 are never out of my thoughts: a boy called Justice, a girl called Tears.”

Mantel’s Writing for the Book Review

Incidents in the rue laugier, by anita brookner (1996).

In this novel, a woman tries to reconstruct her dead mother’s emotional history using a handful of objects — a pink kimono, a notebook with cryptic scribblings. The story begins “warily,” Mantel writes, “as if the business of storytelling might be an infringement of good manners.”

After Hannibal , by Barry Unsworth (1997)

“Barry Unsworth’s latest novel is a sad comedy of cheats and fools,” Mantel wrote, “a story of unbounded beauty and blighted hopes, of multiple and layered betrayals, ‘a regression of falsehoods and deceptions going back through all the generations to the original agreement, God’s pact with Adam.’”

Down by the River , by Edna O’Brien (1997)

“This is powerful material, and Ms. O’Brien has apparently decided her prose must rise to it. The reader may feel some initial queasiness,” Mantel wrote. Her criticism is scalpel sharp, delivered with a crisp bedside manner.

Spending , by Mary Gordon (1998)

In 1998, Mantel cut to the chase in the first line of her review of Mary Gordon’s novel, “Spending”: “Sex, art, money: That’s what it’s all about,” she wrote. “So we learn in the neatly chiseled opening sentences of Mary Gordon’s new novel. Add in death and we would have a ferocious quaternity to frame the action.”

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

Salman Rushdie’s new memoir, “Knife,” addresses the attack that maimed him in 2022, and pays tribute to his wife who saw him through .

Recent books by Allen Bratton, Daniel Lefferts and Garrard Conley depict gay Christian characters not usually seen in queer literature.

What can fiction tell us about the apocalypse? The writer Ayana Mathis finds unexpected hope in novels of crisis by Ling Ma, Jenny Offill and Jesmyn Ward .

At 28, the poet Tayi Tibble has been hailed as the funny, fresh and immensely skilled voice of a generation in Māori writing .

Amid a surge in book bans, the most challenged books in the United States in 2023 continued to focus on the experiences of L.G.B.T.Q. people or explore themes of race.

Each week, top authors and critics join the Book Review’s podcast to talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Hilary Mantel remembered: ‘She was the queen of literature’

The beloved writer of the Wolf Hall trilogy and Beyond Black has died. Here, leading contemporaries pay tribute Hilary Mantel, celebrated author of Wolf Hall, dies aged 70 The pen is in our hands. A happy ending is ours to write’: Hilary Mantel in her own words ‘We’ve lost a genius’: authors and politicians pay tribute to Hilary Mantel

Margaret Atwood: ‘She had a grasp of the dark and spidery corners of human nature’

Canadian author of The Handmaid’s Tale and The Blind Assassin, and twice Booker winner

I was shocked and saddened to hear of Hilary Mantel’s death. It was always a pleasure to read such a smart, deft, meticulous, thoughtful writer, and one with such a grasp of the dark and spidery corners of human nature - and a pleasure to review her too, which I did both early and late. A Place of Greater Safety was an eye-opener about the French Revolution, and the Cromwell trilogy was a well-known stunner. She never shied away from the difficult folks, and doled out a tad of redemption for even the most hardened cases. What might she have written next? I don’t know, but I will miss it.

Anne Enright: ‘She bristled with intelligence’

Irish writer best known for her Booker prize-winning novel The Gathering

Hilary Mantel recently spent time in west Cork where she had acquired a house. It was her intention to reclaim her European citizenship by way of the Irish passport to which she was entitled. There were times in her life when her Irish ancestry was less important to her, but after the Brexit referendum it had become central again.

Mantel grew up in a pocket of Irish immigrants that lodged in Hadfield, a stony town in the High Peak of Derbyshire. Her mother was a mill-girl, her grandmother did not know her own date of birth. She described a childhood so frugal and windswept that she was 11 years old before she saw a rose. Her family was part of a declining Irish population in a town where tensions between Catholic and Protestant played out in daily life. This sense of displacement made history important to Mantel, whose childhood was haunted by the figures of the dead, not least the men who did not return with her beloved grandfather from the first world war. Mantel felt presences from an early age and was not fully at home in her own skin. When she was eight, she had a vision of “a body inside my body … budding and malign”, in part because she realised that she would not grow up to be a boy. When her parents’ marriage ended, she fell into repeated fevers, lost her thick hair, and turned into a child the local doctor called “little miss Neverwell”.

Mantel bristled with intelligence, looked at everything, saw everything. She described herself as a slightly pedantic small girl. “Few people acted with any malice towards me, it was just that I was unsuited to being a child.” With the uneasy energy of her early life, Mantel made rigorous and unsettling work about history, the body and the unknowable. The strangeness of the past made sense to her.

Her last interviews returned to the fact that she came from a family of immigrants. Her work about the court of Henry VIII might have placed her at the heart of a British nationalist revival, but Mantel had no interest in any such a thing. Her brilliance depended, to the last, on the piercing eye of a writer who is an outsider, one who is never fully at home.

Colm Tóibín: ‘Her range was extraordinary’

Irish author of The Heather Blazing and The Story of the Night

There was something boundless about Hilary Mantel’s imaginative process. She saw historical forces operating with immense clarity, but she also could create with real skill and flair the intimate moment, the tiny scene, the sudden shift of light or of power in a relationship. Her range was extraordinary, from early semi-autobiographical stories to the late magisterial novels. It wasn’t merely the breadth of her historical research that was impressive, it was how she could create a scene as if by magic. There was lightness in her touch. Of all her novels, I loved ‘The Giant O’Brien’, the darting, suggestive sentences, the dialogue like a chorus, or a commentary on life and its hardships. At the end of June, when I did a Zoom with her for the 92nd Street Y, she was filled with excitement at the prospect of moving to Ireland and spoke of the house she had bought in Kinsale. It is immensely sad that this now won’t happen.

Kamila Shamsie: ‘She was incredibly gracious and generous’

Pakistani and British writer of Burnt Shadows and Home Fire

How many of us, at the start of the first lockdown, had a breezy confidence that it wouldn’t last very long and in the meantime at least we would have the company of Mantel’s The Mirror and the Light (published on 5 March 2020) to take us through the dark times? I was certainly of that number, and plunged into the third book of her Cromwell trilogy, correctly assured that here was a writer with the ability to pull me into her world, no matter how distracting the news of the world around me might be. I intended to read while taking notes – I was due to interview Hilary about her new novel at the Manchester literature festival in April that year – but all plans of note-taking were quickly abandoned in favour of the pure immersive pleasure of the novel. And anyway, why did I need notes? There was no shortage of questions I already had to ask one of the greatest writers on the planet. But the one question I really wanted the answer to might just have been the one that even Mantel couldn’t answer: how exactly is your brain wired?

Mantel was that rare writer whom you read and think, I have no idea how your brain goes where it goes, and how it comes back to produce the work that it does. It is a matter of immense sadness that I will never again hear the words “new novel by Hilary Mantel”, and the only consolation is the books that she has left us with.

I deeply regret never having the chance to speak to her about The Mirror and the Light – not only for the public conversation, but for the few minutes of private talk that would precede and perhaps follow it. In my few short encounters with Mantel, she was incredibly gracious and generous. I always walked away thinking: “One day, we’ll sit down for a proper chat and we’ll have a really good laugh.”

William Boyd: ‘Her fierce intelligence, sense of humour and stoicism seemed enshrined in her novels’

Scottish author of A Good Man in Africa and Any Human Heart

I didn’t know Hilary Mantel well, but we did meet from time to time over the years. We first encountered each other some 20 years ago at a literary festival organised by Cosmopolitan magazine. We last met in June this year, at Clarence House, of all places. She seemed very well and full of energy. I have huge admiration for her body of work and, also, enormous respect for her as a person – as I was aware of the serious health issues that dominated her life. Her fierce intelligence, sense of humour and her tremendous, clear-eyed stoicism seemed somehow conjoined and enshrined in her writer’s life and the enduring novels that she wrote.

Maggie O’Farrell: ‘She leaves behind a huge, unfillable vacuum’

Northern Irish writer whose novel Hamnet won the 2020 Women’s prize for fiction

We have lost another monarch this week. Mantel was queen of literature, and her reign was, like Elizabeth II’s, long, varied and uncontested. She leaves behind a huge, unfillable vacuum, a deep sense of loss for the reading public, and a toweringly significant body of work.

As a writer, Mantel was fierce, fabulous and fearless. In her books, she took risks, she pushed back the boundaries of narrative, she grabbed hold of novelistic rules and shook them by the neck until they obeyed her. Everything she wrote, whether it was memoir, journalism, contemporary novels or weighty historical trilogies, showed the labour involved in her work – and also her love of that labour. I challenge anyone to find a word or even a comma out of place; there isn’t an ounce of fat on the bones of her work, even the books that cover 900-odd pages. It’s clear from her prose that she was profoundly committed to her craft, to editing and re-editing and redrafting it into perfection. Her voice on the page is unmistakable; it’s possible to deduce within a paragraph whether or not it was written by her. That perspicuity, those elegant sub-clauses, that precision, the psychological acuity, her logophilic daring.

As a person, she was unfailingly generous, making time to support and champion the work of other writers. She always held the ladder for those coming up behind her, which is not always the case with someone of Mantel’s stature. She loved her own work; she loved the work of others and she wanted to share it all with the world.

How fortunate we were to have her. How much poorer our shelves will be without the novels she might have gone on to write. She said in a recent interview that she believed in an afterlife and her novels often grappled with a perforated membrane between life and death. Let’s hope she has reached her ideal posthumous location, perhaps a well-stocked library. Rest in peace, Queen Hilary. You will be missed.

Ian McEwan: ‘She helped us know ourselves as a nation’

British writer known for his novels Atonement and Enduring Love

To borrow John Updike’s phrase, Mantel gave history its beautiful due. In doing so, she deployed breathtaking resources of literary skill, and helped us know ourselves as a nation. The Wolf Hall trilogy will stand as her monument, but her backlist is full of wonders. She was also brilliant, witty company with a distinctive mode of scepticism that was all her own.

Sarah Waters: ‘She was the UK’s greatest living writer’

Welsh author of Tipping the Velvet and Fingersmith

I remember selling Hilary’s books when I worked in a bookshop in the late 1980s, and it’s astonishing to think that, already an established writer then, she still had a further 30-year career ahead of her. Many authors do their most significant work early on and then simply repeat it, but she was one of those really extraordinary writers who start off great and get even better.

Her literary longevity came partly, perhaps, from the fact that she was able to take her fiction in so many different directions; she was as at home in historical epics as she was in tight domestic dramas, as comfortable with fable as with naturalism. She is best known for her marvellous Thomas Cromwell trilogy, but it is her more gothic, female-centred novels that have inspired me most, especially the creepy masterpiece Eight Months on Ghazzah Street and the sublime Beyond Black.

I associate her with two other fiercely intelligent and darkly mischievous British writers, Muriel Spark and Beryl Bainbridge: her work, like theirs, has always resisted easy categorisation and has been all the more fascinating for it. I met her only a couple of times, and she was unfailingly kind and generous, but I was as flustered in her presence as if I were meeting royalty – which, in a way, I think I was. She was the UK’s greatest living writer, and her death is a dreadful loss.

Sarah Perry: ‘What will we do without her?’

British author of The Essex Serpent

Hilary Mantel is dead and I am ashamed of the sorrow I feel, since I met her only once, and we corresponded rarely; it occurs to me she would possibly be amused by my sorrow, and amused, too, that I’ve taken out like a holy relic the Christmas card in which she hoped I was happy and that 2015 would be good to me and to my gift, which she signed Hilary (Mantel).

A year or so before, I’d locked myself in the toilets of the offices where I worked to finish her memoir Giving Up the Ghost. Alone in a cubicle, I wept over its unflinching account of suffering and loss, and returning to my desk I wrote a love letter that ran to several pages. I praised what we must all praise: the elegance and rigour of her prose, the startling visions of her imagination, the candour and courage of her self-knowledge, the treacly blackness of her wit and the piercing intelligence that riveted the lot together with bolts of stainless steel. Having once read that she bound her manuscripts with treasury tags, I raided the office stationery cupboard, shoved a fistful of them in the envelope and sent my devotion first class.

In the years that followed I have loved her only more. The year 2015, as it turned out, was not as good to me as she had hoped it would be, nor were the years that followed: I became ill and endured tormenting pain, so that her writing on bodily suffering arrived for me like despatches from a traveller who had entered a bad land long before me and had left a map and a light. I loved her for her novels, unmatched by any writer now living, but I loved her, too, because she was a woman for all seasons, whose intellect was equal to every moral or political matter the world could hurl at her door. What will we do without her? I have been waiting for her word on the crown that has passed from one old hand to another, and now the word won’t come.

All afternoon I have aimlessly paced the house, followed by dogs, holding the card she sent me, thinking myself absurd. I find her in the blue-eyed model of a jackdaw that eyes me from the mantelpiece, and the deck of tarot cards I keep close to hand; I find her in the box of opioids I store under my bed in case pain returns to my life; I find her in the postcard of Cranmer she sent me once, which I have pinned above my desk. Mostly I find her at my shoulder berating me when my prose becomes weak and thin. “All houses are haunted,” she wrote. She haunts mine and cannot be shifted. What poor priest would dare?

- Hilary Mantel

- Maggie O'Farrell

- Kamila Shamsie

- Anne Enright

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

Hilary Mantel was one of the great voices of historical fiction – and so much more

Pro-Vice-Chancellor for Cultural Engagement, Professor of English Literature, University of Liverpool

Disclosure statement

Dinah Birch does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Liverpool provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

Dame Hilary Mantel was a writer of immense skill and originality, and her death represents an incalculable loss to British literature. She will be chiefly remembered for her trilogy on the life of the Tudor politician Thomas Cromwell .

The grace and vigour of these gripping novels transformed our understanding of what historical fiction can do. They were extraordinarily successful. Wolf Hall (2009) and Bring Up the Bodies (2012) both won the Booker Prize (she was the first woman to win the prize more than once), and The Mirror and the Light (2020) was longlisted. I was a member of the jury that awarded the Booker Prize to Bring Up the Bodies, and we were of one mind about the superb quality of that novel.

Adaptations for both television and stage followed, and it is a tribute to the power of Mantel’s exploration of the ambiguities surrounding Cromwell’s dramatic life that these versions brought many enthusiastic new readers to her novels. She became, relatively late in her life, a literary star.

The popularity of Mantel’s trilogy should not overshadow the remarkable range of her achievement. Her treatment of Thomas Cromwell brought a mass readership, but the accomplishment of her earlier novels had already won critical recognition.

A writer’s life

Mantel graduated from LSE and Sheffield University, and married Gerald McEwan, a geologist, in 1972 (they divorced in 1981, and remarried in 1982). A short spell of employment as a social worker lay behind her first published novel, the darkly comic Every Day is Mother’s Day (1985), and its sequel Vacant Possession (1986).

A major historical novel, A Place of Greater Safety (completed in 1979, but not published until 1992) is a characteristically innovative interpretation of the French Revolution. Here, as throughout Mantel’s writing, a far-sighted grasp of the sweep of history and politics was fused with the inward particularities of individual experience.

Mantel had a lyrical sense of the irreducible strangeness of the world, with its vivid moments of beauty and threat, but this was never removed from her understanding of the moral imperatives of our shared responsibilities. She was never a neutral observer of the ebb and flow of history.

Mantel spent extended periods of her life overseas – notably in Botswana and Saudi Arabia – and she was always alert to a world beyond Britain. Eight Months on Ghazzah Street (1988) is a tense account of misunderstandings between westerners and Saudis living in Jeddah. A Change of Climate (1994) draws on her life in Botswana, and the traumatic social divisions she had witnessed in southern Africa.

Mantel had an unusually wide and well-informed grasp of social and cultural politics, but she never lost her interest in lives that unfold on the edge of what might be perceived as normality. Fludd (1989), describes a quasi-supernatural stranger whose arrival turns a dismal Catholic community upside down. It is never quite clear who Fludd is, or where he has come from, or whether he is an agent of good or evil.

The Giant, O’Brien (1998), based on the Irish giant Charles Byrne and the Scottish surgeon John Hunter, is in part a rueful reflection on Mantel’s own Irish roots. The legacies of Irish Catholicism also shadow An Experiment in Love (1995), a novel that looks back on the lives of girls of Mantel’s postwar generation - eager to take advantage of new opportunities for education, but still haunted by the constraints of the past.

A rich legacy

The sense that another world exists, its presence flickering just past our everyday vision, underlies all of Mantel’s work. Beyond Black (2005) is an unsettling and brilliantly entertaining account of the life of a medium, who may or may not be a fraud.

Giving up the Ghost (2003), a searing memoir, repeatedly returns to the ghosts that stalked her early years – family ghosts, ghosts of unborn children, ghosts of lives that might have taken a different shape. Learning to Talk (2003), published in the same year, is a collection of short stories that turn on the same theme.

These stories are in part autobiographical recollections of Mantel’s childhood in Glossop, as she began to remove herself from the divided world of her family. Here too, it is the sharply observed details that linger – Miss Webster, for instance, the elocution teacher, with her careful accent – “precariously genteel, Manchester with icing”.

More recent short stories have been openly political, and sometimes controversial – notably The Assassination of Margaret Thatcher , the provocative title story in a collection published in 2014.

This shining stream of writing has now come to an end. It’s good to know that Hilary Mantel experienced and enjoyed all the success she had so richly earned, and that we are left with such a rich body of writing to relish and revisit. But the sense of immediate loss is painful. She was a unique and generous talent, and she will be hugely missed.

- Hilary Mantel

- Historical fiction

- Thomas Cromwell

- Anne Boleyn

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Senior Disability Services Advisor

Deputy Social Media Producer

Associate Professor, Occupational Therapy

GRAINS RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION CHAIRPERSON

IMAGES

VIDEO