How Effective Is Online Learning? What the Research Does and Doesn’t Tell Us

- Share article

Editor’s Note: This is part of a series on the practical takeaways from research.

The times have dictated school closings and the rapid expansion of online education. Can online lessons replace in-school time?

Clearly online time cannot provide many of the informal social interactions students have at school, but how will online courses do in terms of moving student learning forward? Research to date gives us some clues and also points us to what we could be doing to support students who are most likely to struggle in the online setting.

The use of virtual courses among K-12 students has grown rapidly in recent years. Florida, for example, requires all high school students to take at least one online course. Online learning can take a number of different forms. Often people think of Massive Open Online Courses, or MOOCs, where thousands of students watch a video online and fill out questionnaires or take exams based on those lectures.

In the online setting, students may have more distractions and less oversight, which can reduce their motivation.

Most online courses, however, particularly those serving K-12 students, have a format much more similar to in-person courses. The teacher helps to run virtual discussion among the students, assigns homework, and follows up with individual students. Sometimes these courses are synchronous (teachers and students all meet at the same time) and sometimes they are asynchronous (non-concurrent). In both cases, the teacher is supposed to provide opportunities for students to engage thoughtfully with subject matter, and students, in most cases, are required to interact with each other virtually.

Coronavirus and Schools

Online courses provide opportunities for students. Students in a school that doesn’t offer statistics classes may be able to learn statistics with virtual lessons. If students fail algebra, they may be able to catch up during evenings or summer using online classes, and not disrupt their math trajectory at school. So, almost certainly, online classes sometimes benefit students.

In comparisons of online and in-person classes, however, online classes aren’t as effective as in-person classes for most students. Only a little research has assessed the effects of online lessons for elementary and high school students, and even less has used the “gold standard” method of comparing the results for students assigned randomly to online or in-person courses. Jessica Heppen and colleagues at the American Institutes for Research and the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research randomly assigned students who had failed second semester Algebra I to either face-to-face or online credit recovery courses over the summer. Students’ credit-recovery success rates and algebra test scores were lower in the online setting. Students assigned to the online option also rated their class as more difficult than did their peers assigned to the face-to-face option.

Most of the research on online courses for K-12 students has used large-scale administrative data, looking at otherwise similar students in the two settings. One of these studies, by June Ahn of New York University and Andrew McEachin of the RAND Corp., examined Ohio charter schools; I did another with colleagues looking at Florida public school coursework. Both studies found evidence that online coursetaking was less effective.

About this series

This essay is the fifth in a series that aims to put the pieces of research together so that education decisionmakers can evaluate which policies and practices to implement.

The conveners of this project—Susanna Loeb, the director of Brown University’s Annenberg Institute for School Reform, and Harvard education professor Heather Hill—have received grant support from the Annenberg Institute for this series.

To suggest other topics for this series or join in the conversation, use #EdResearchtoPractice on Twitter.

Read the full series here .

It is not surprising that in-person courses are, on average, more effective. Being in person with teachers and other students creates social pressures and benefits that can help motivate students to engage. Some students do as well in online courses as in in-person courses, some may actually do better, but, on average, students do worse in the online setting, and this is particularly true for students with weaker academic backgrounds.

Students who struggle in in-person classes are likely to struggle even more online. While the research on virtual schools in K-12 education doesn’t address these differences directly, a study of college students that I worked on with Stanford colleagues found very little difference in learning for high-performing students in the online and in-person settings. On the other hand, lower performing students performed meaningfully worse in online courses than in in-person courses.

But just because students who struggle in in-person classes are even more likely to struggle online doesn’t mean that’s inevitable. Online teachers will need to consider the needs of less-engaged students and work to engage them. Online courses might be made to work for these students on average, even if they have not in the past.

Just like in brick-and-mortar classrooms, online courses need a strong curriculum and strong pedagogical practices. Teachers need to understand what students know and what they don’t know, as well as how to help them learn new material. What is different in the online setting is that students may have more distractions and less oversight, which can reduce their motivation. The teacher will need to set norms for engagement—such as requiring students to regularly ask questions and respond to their peers—that are different than the norms in the in-person setting.

Online courses are generally not as effective as in-person classes, but they are certainly better than no classes. A substantial research base developed by Karl Alexander at Johns Hopkins University and many others shows that students, especially students with fewer resources at home, learn less when they are not in school. Right now, virtual courses are allowing students to access lessons and exercises and interact with teachers in ways that would have been impossible if an epidemic had closed schools even a decade or two earlier. So we may be skeptical of online learning, but it is also time to embrace and improve it.

A version of this article appeared in the April 01, 2020 edition of Education Week as How Effective Is Online Learning?

Sign Up for EdWeek Tech Leader

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

- Open supplemental data

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, insights into students’ experiences and perceptions of remote learning methods: from the covid-19 pandemic to best practice for the future.

- 1 Minerva Schools at Keck Graduate Institute, San Francisco, CA, United States

- 2 Ronin Institute for Independent Scholarship, Montclair, NJ, United States

- 3 Department of Physics, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

This spring, students across the globe transitioned from in-person classes to remote learning as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. This unprecedented change to undergraduate education saw institutions adopting multiple online teaching modalities and instructional platforms. We sought to understand students’ experiences with and perspectives on those methods of remote instruction in order to inform pedagogical decisions during the current pandemic and in future development of online courses and virtual learning experiences. Our survey gathered quantitative and qualitative data regarding students’ experiences with synchronous and asynchronous methods of remote learning and specific pedagogical techniques associated with each. A total of 4,789 undergraduate participants representing institutions across 95 countries were recruited via Instagram. We find that most students prefer synchronous online classes, and students whose primary mode of remote instruction has been synchronous report being more engaged and motivated. Our qualitative data show that students miss the social aspects of learning on campus, and it is possible that synchronous learning helps to mitigate some feelings of isolation. Students whose synchronous classes include active-learning techniques (which are inherently more social) report significantly higher levels of engagement, motivation, enjoyment, and satisfaction with instruction. Respondents’ recommendations for changes emphasize increased engagement, interaction, and student participation. We conclude that active-learning methods, which are known to increase motivation, engagement, and learning in traditional classrooms, also have a positive impact in the remote-learning environment. Integrating these elements into online courses will improve the student experience.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically changed the demographics of online students. Previously, almost all students engaged in online learning elected the online format, starting with individual online courses in the mid-1990s through today’s robust online degree and certificate programs. These students prioritize convenience, flexibility and ability to work while studying and are older than traditional college age students ( Harris and Martin, 2012 ; Levitz, 2016 ). These students also find asynchronous elements of a course are more useful than synchronous elements ( Gillingham and Molinari, 2012 ). In contrast, students who chose to take courses in-person prioritize face-to-face instruction and connection with others and skew considerably younger ( Harris and Martin, 2012 ). This leaves open the question of whether students who prefer to learn in-person but are forced to learn remotely will prefer synchronous or asynchronous methods. One study of student preferences following a switch to remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic indicates that students enjoy synchronous over asynchronous course elements and find them more effective ( Gillis and Krull, 2020 ). Now that millions of traditional in-person courses have transitioned online, our survey expands the data on student preferences and explores if those preferences align with pedagogical best practices.

An extensive body of research has explored what instructional methods improve student learning outcomes (Fink. 2013). Considerable evidence indicates that active-learning or student-centered approaches result in better learning outcomes than passive-learning or instructor-centered approaches, both in-person and online ( Freeman et al., 2014 ; Chen et al., 2018 ; Davis et al., 2018 ). Active-learning approaches include student activities or discussion in class, whereas passive-learning approaches emphasize extensive exposition by the instructor ( Freeman et al., 2014 ). Constructivist learning theories argue that students must be active participants in creating their own learning, and that listening to expert explanations is seldom sufficient to trigger the neurological changes necessary for learning ( Bostock, 1998 ; Zull, 2002 ). Some studies conclude that, while students learn more via active learning, they may report greater perceptions of their learning and greater enjoyment when passive approaches are used ( Deslauriers et al., 2019 ). We examine student perceptions of remote learning experiences in light of these previous findings.

In this study, we administered a survey focused on student perceptions of remote learning in late May 2020 through the social media account of @unjadedjade to a global population of English speaking undergraduate students representing institutions across 95 countries. We aim to explore how students were being taught, the relationship between pedagogical methods and student perceptions of their experience, and the reasons behind those perceptions. Here we present an initial analysis of the results and share our data set for further inquiry. We find that positive student perceptions correlate with synchronous courses that employ a variety of interactive pedagogical techniques, and that students overwhelmingly suggest behavioral and pedagogical changes that increase social engagement and interaction. We argue that these results support the importance of active learning in an online environment.

Materials and Methods

Participant pool.

Students were recruited through the Instagram account @unjadedjade. This social media platform, run by influencer Jade Bowler, focuses on education, effective study tips, ethical lifestyle, and promotes a positive mindset. For this reason, the audience is presumably academically inclined, and interested in self-improvement. The survey was posted to her account and received 10,563 responses within the first 36 h. Here we analyze the 4,789 of those responses that came from undergraduates. While we did not collect demographic or identifying information, we suspect that women are overrepresented in these data as followers of @unjadedjade are 80% women. A large minority of respondents were from the United Kingdom as Jade Bowler is a British influencer. Specifically, 43.3% of participants attend United Kingdom institutions, followed by 6.7% attending university in the Netherlands, 6.1% in Germany, 5.8% in the United States and 4.2% in Australia. Ninety additional countries are represented in these data (see Supplementary Figure 1 ).

Survey Design

The purpose of this survey is to learn about students’ instructional experiences following the transition to remote learning in the spring of 2020.

This survey was initially created for a student assignment for the undergraduate course Empirical Analysis at Minerva Schools at KGI. That version served as a robust pre-test and allowed for identification of the primary online platforms used, and the four primary modes of learning: synchronous (live) classes, recorded lectures and videos, uploaded or emailed materials, and chat-based communication. We did not adapt any open-ended questions based on the pre-test survey to avoid biasing the results and only corrected language in questions for clarity. We used these data along with an analysis of common practices in online learning to revise the survey. Our revised survey asked students to identify the synchronous and asynchronous pedagogical methods and platforms that they were using for remote learning. Pedagogical methods were drawn from literature assessing active and passive teaching strategies in North American institutions ( Fink, 2013 ; Chen et al., 2018 ; Davis et al., 2018 ). Open-ended questions asked students to describe why they preferred certain modes of learning and how they could improve their learning experience. Students also reported on their affective response to learning and participation using a Likert scale.

The revised survey also asked whether students had responded to the earlier survey. No significant differences were found between responses of those answering for the first and second times (data not shown). See Supplementary Appendix 1 for survey questions. Survey data was collected from 5/21/20 to 5/23/20.

Qualitative Coding

We applied a qualitative coding framework adapted from Gale et al. (2013) to analyze student responses to open-ended questions. Four researchers read several hundred responses and noted themes that surfaced. We then developed a list of themes inductively from the survey data and deductively from the literature on pedagogical practice ( Garrison et al., 1999 ; Zull, 2002 ; Fink, 2013 ; Freeman et al., 2014 ). The initial codebook was revised collaboratively based on feedback from researchers after coding 20–80 qualitative comments each. Before coding their assigned questions, alignment was examined through coding of 20 additional responses. Researchers aligned in identifying the same major themes. Discrepancies in terms identified were resolved through discussion. Researchers continued to meet weekly to discuss progress and alignment. The majority of responses were coded by a single researcher using the final codebook ( Supplementary Table 1 ). All responses to questions 3 (4,318 responses) and 8 (4,704 responses), and 2,512 of 4,776 responses to question 12 were analyzed. Valence was also indicated where necessary (i.e., positive or negative discussion of terms). This paper focuses on the most prevalent themes from our initial analysis of the qualitative responses. The corresponding author reviewed codes to ensure consistency and accuracy of reported data.

Statistical Analysis

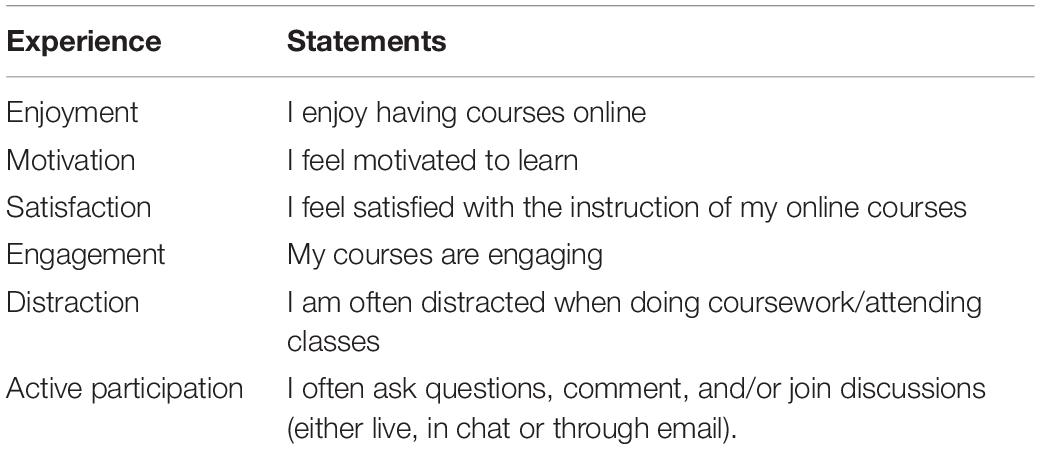

The survey included two sets of Likert-scale questions, one consisting of a set of six statements about students’ perceptions of their experiences following the transition to remote learning ( Table 1 ). For each statement, students indicated their level of agreement with the statement on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (“Strongly Disagree”) to 5 (“Strongly Agree”). The second set asked the students to respond to the same set of statements, but about their retroactive perceptions of their experiences with in-person instruction before the transition to remote learning. This set was not the subject of our analysis but is present in the published survey results. To explore correlations among student responses, we used CrossCat analysis to calculate the probability of dependence between Likert-scale responses ( Mansinghka et al., 2016 ).

Table 1. Likert-scale questions.

Mean values are calculated based on the numerical scores associated with each response. Measures of statistical significance for comparisons between different subgroups of respondents were calculated using a two-sided Mann-Whitney U -test, and p -values reported here are based on this test statistic. We report effect sizes in pairwise comparisons using the common-language effect size, f , which is the probability that the response from a random sample from subgroup 1 is greater than the response from a random sample from subgroup 2. We also examined the effects of different modes of remote learning and technological platforms using ordinal logistic regression. With the exception of the mean values, all of these analyses treat Likert-scale responses as ordinal-scale, rather than interval-scale data.

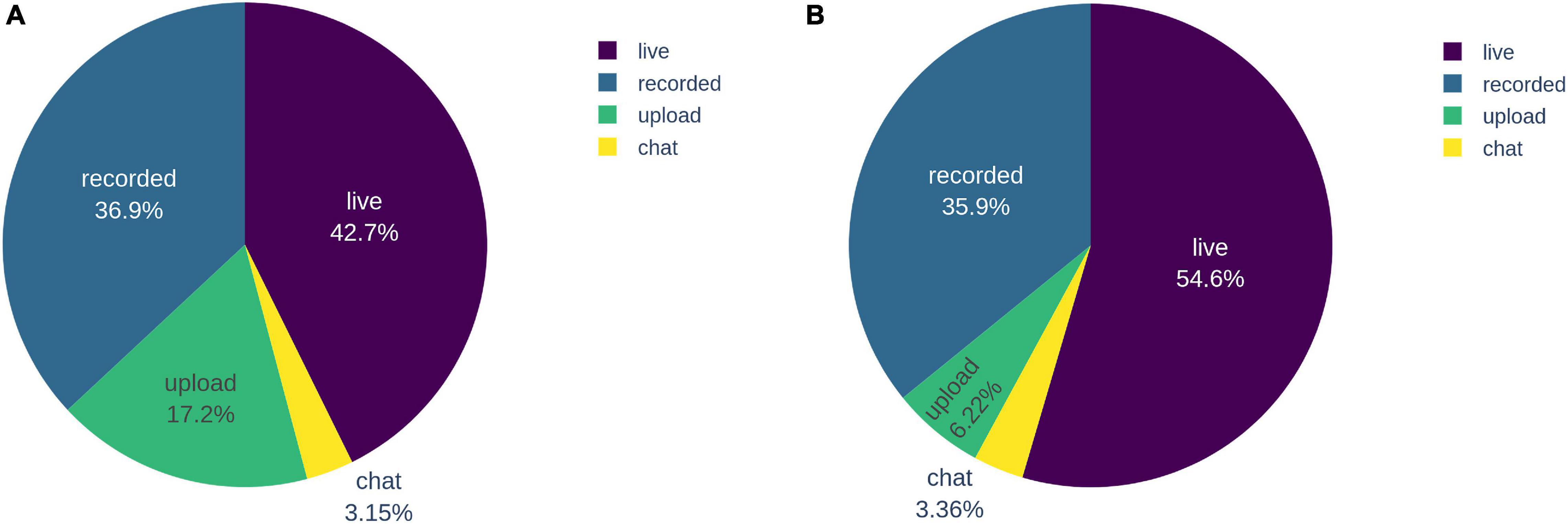

Students Prefer Synchronous Class Sessions

Students were asked to identify their primary mode of learning given four categories of remote course design that emerged from the pilot survey and across literature on online teaching: live (synchronous) classes, recorded lectures and videos, emailed or uploaded materials, and chats and discussion forums. While 42.7% ( n = 2,045) students identified live classes as their primary mode of learning, 54.6% ( n = 2613) students preferred this mode ( Figure 1 ). Both recorded lectures and live classes were preferred over uploaded materials (6.22%, n = 298) and chat (3.36%, n = 161).

Figure 1. Actual (A) and preferred (B) primary modes of learning.

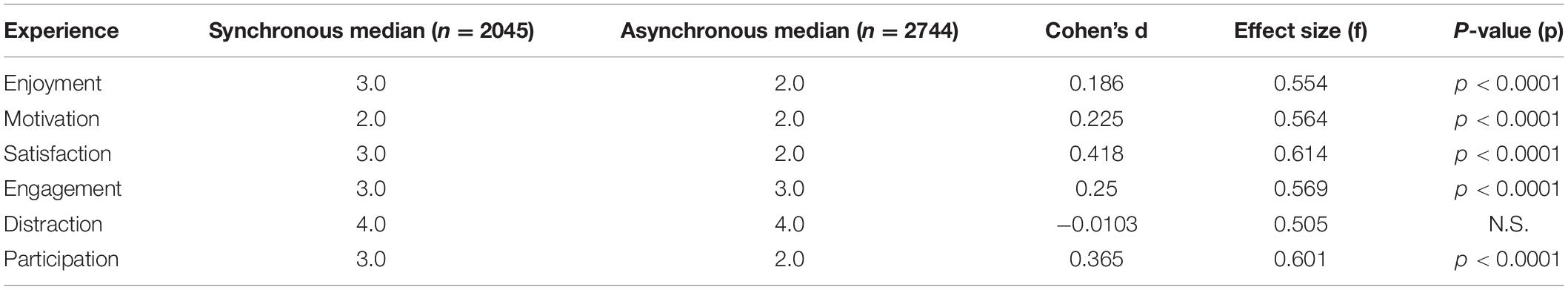

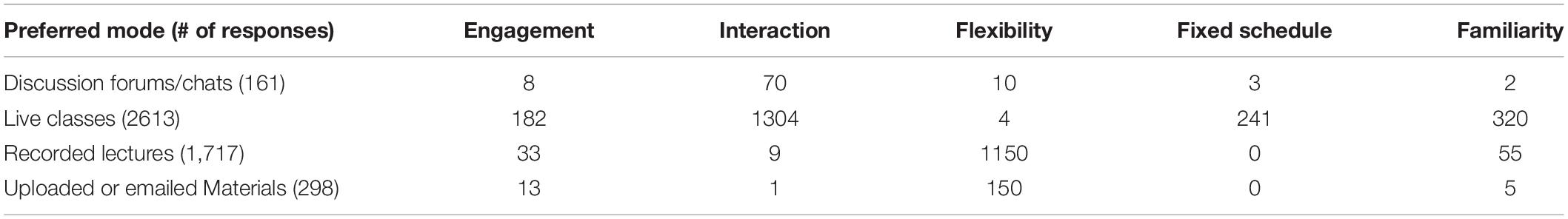

In addition to a preference for live classes, students whose primary mode was synchronous were more likely to enjoy the class, feel motivated and engaged, be satisfied with instruction and report higher levels of participation ( Table 2 and Supplementary Figure 2 ). Regardless of primary mode, over two-thirds of students reported they are often distracted during remote courses.

Table 2. The effect of synchronous vs. asynchronous primary modes of learning on student perceptions.

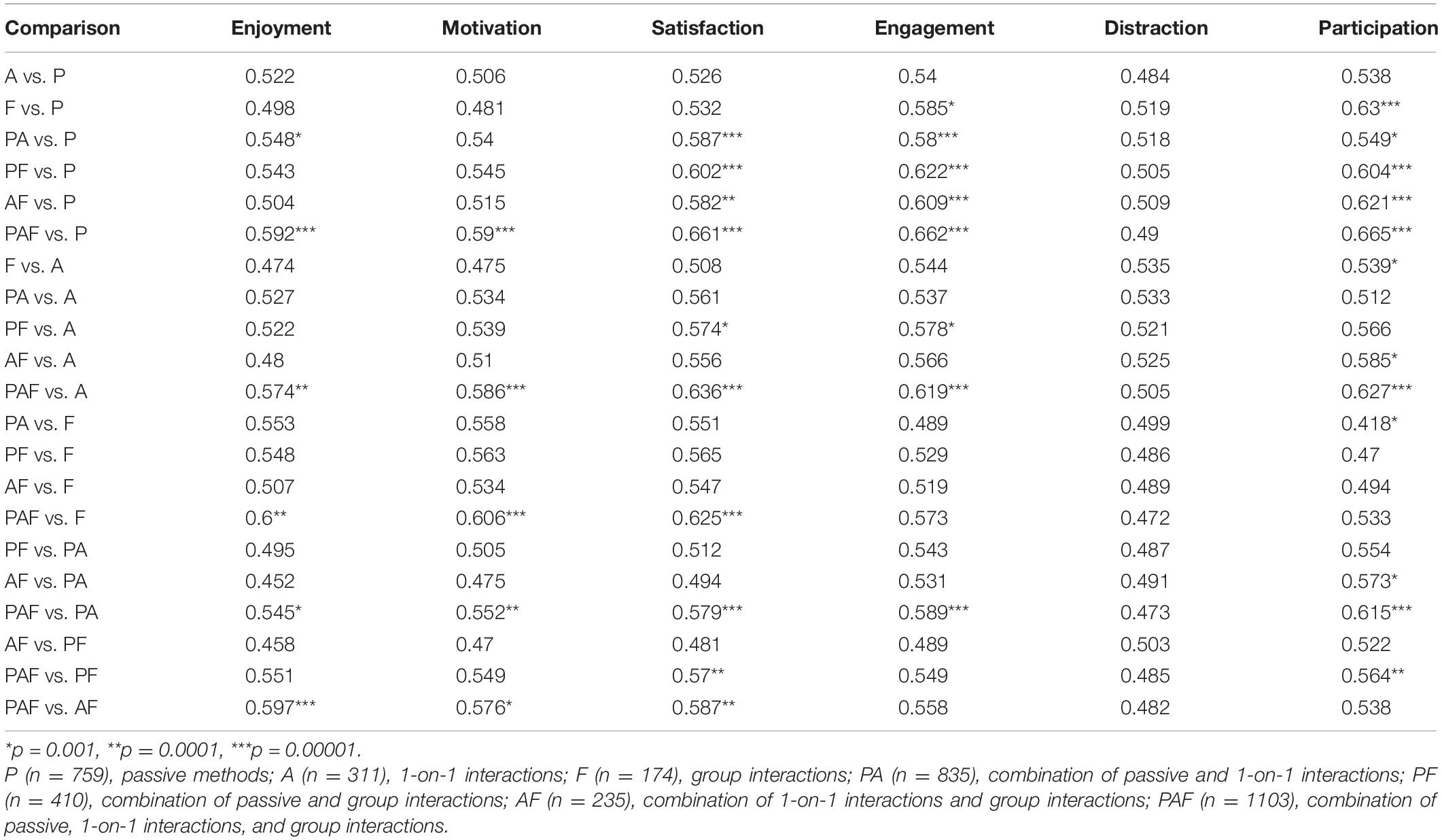

Variation in Pedagogical Techniques for Synchronous Classes Results in More Positive Perceptions of the Student Learning Experience

To survey the use of passive vs. active instructional methods, students reported the pedagogical techniques used in their live classes. Among the synchronous methods, we identify three different categories ( National Research Council, 2000 ; Freeman et al., 2014 ). Passive methods (P) include lectures, presentations, and explanation using diagrams, white boards and/or other media. These methods all rely on instructor delivery rather than student participation. Our next category represents active learning through primarily one-on-one interactions (A). The methods in this group are in-class assessment, question-and-answer (Q&A), and classroom chat. Group interactions (F) included classroom discussions and small-group activities. Given these categories, Mann-Whitney U pairwise comparisons between the 7 possible combinations and Likert scale responses about student experience showed that the use of a variety of methods resulted in higher ratings of experience vs. the use of a single method whether or not that single method was active or passive ( Table 3 ). Indeed, students whose classes used methods from each category (PAF) had higher ratings of enjoyment, motivation, and satisfaction with instruction than those who only chose any single method ( p < 0.0001) and also rated higher rates of participation and engagement compared to students whose only method was passive (P) or active through one-on-one interactions (A) ( p < 0.00001). Student ratings of distraction were not significantly different for any comparison. Given that sets of Likert responses often appeared significant together in these comparisons, we ran a CrossCat analysis to look at the probability of dependence across Likert responses. Responses have a high probability of dependence on each other, limiting what we can claim about any discrete response ( Supplementary Figure 3 ).

Table 3. Comparison of combinations of synchronous methods on student perceptions. Effect size (f).

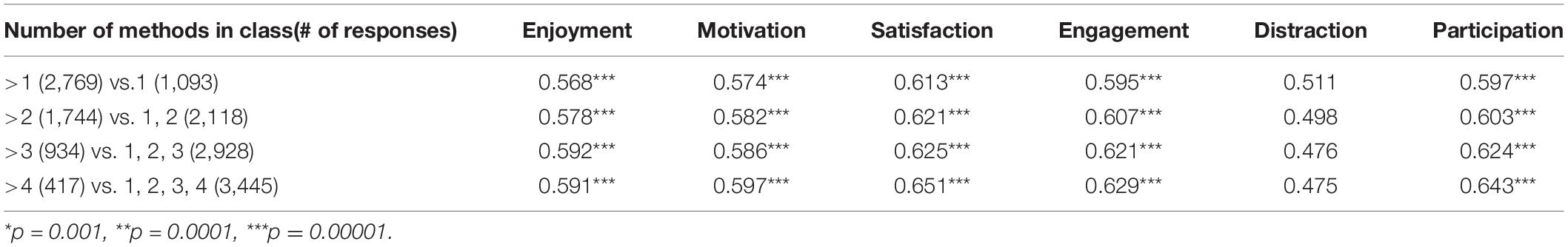

Mann-Whitney U pairwise comparisons were also used to check if improvement in student experience was associated with the number of methods used vs. the variety of types of methods. For every comparison, we found that more methods resulted in higher scores on all Likert measures except distraction ( Table 4 ). Even comparison between four or fewer methods and greater than four methods resulted in a 59% chance that the latter enjoyed the courses more ( p < 0.00001) and 60% chance that they felt more motivated to learn ( p < 0.00001). Students who selected more than four methods ( n = 417) were also 65.1% ( p < 0.00001), 62.9% ( p < 0.00001) and 64.3% ( p < 0.00001) more satisfied with instruction, engaged, and actively participating, respectfully. Therefore, there was an overlap between how the number and variety of methods influenced students’ experiences. Since the number of techniques per category is 2–3, we cannot fully disentangle the effect of number vs. variety. Pairwise comparisons to look at subsets of data with 2–3 methods from a single group vs. 2–3 methods across groups controlled for this but had low sample numbers in most groups and resulted in no significant findings (data not shown). Therefore, from the data we have in our survey, there seems to be an interdependence between number and variety of methods on students’ learning experiences.

Table 4. Comparison of the number of synchronous methods on student perceptions. Effect size (f).

Variation in Asynchronous Pedagogical Techniques Results in More Positive Perceptions of the Student Learning Experience

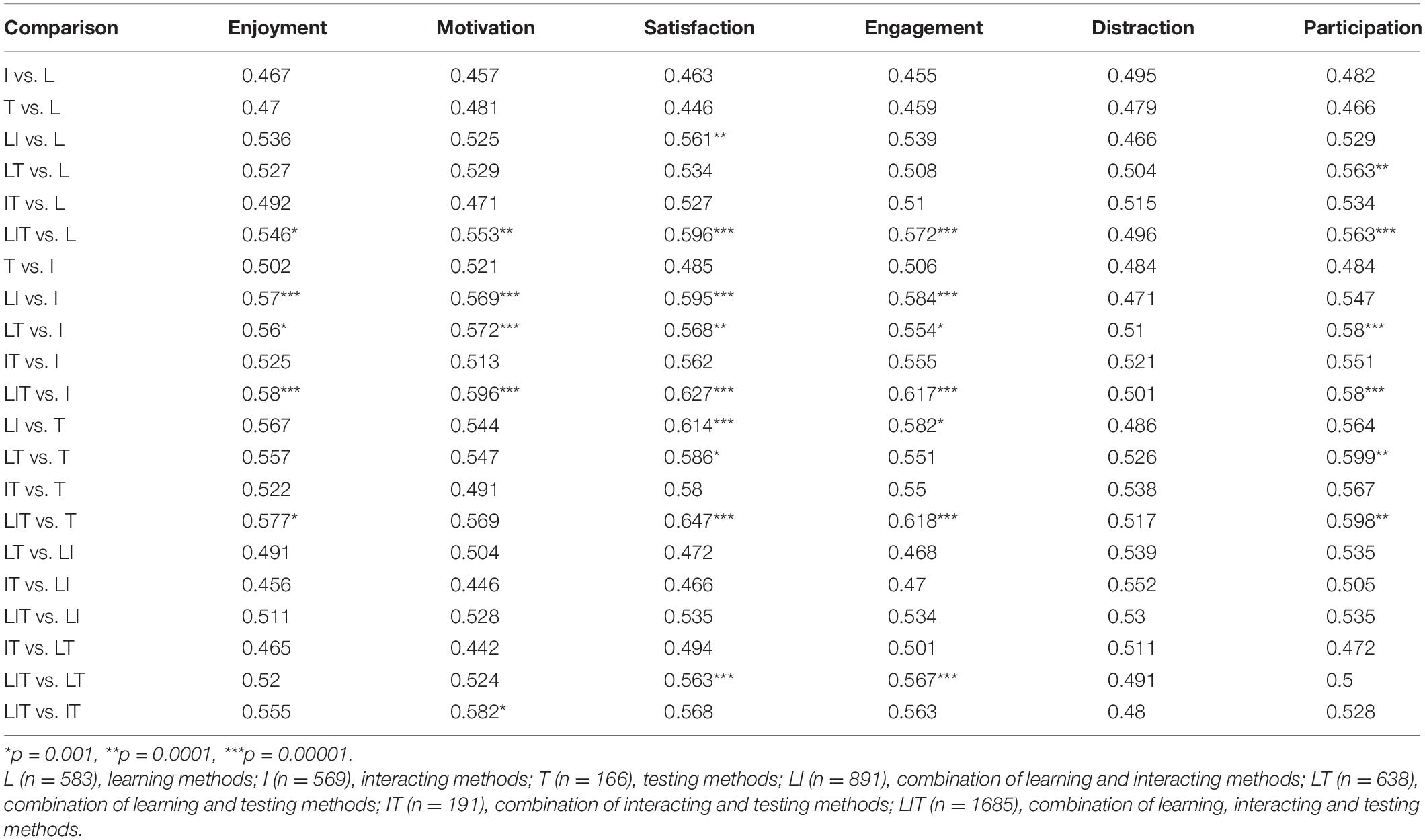

Along with synchronous pedagogical methods, students reported the asynchronous methods that were used for their classes. We divided these methods into three main categories and conducted pairwise comparisons. Learning methods include video lectures, video content, and posted study materials. Interacting methods include discussion/chat forums, live office hours, and email Q&A with professors. Testing methods include assignments and exams. Our results again show the importance of variety in students’ perceptions ( Table 5 ). For example, compared to providing learning materials only, providing learning materials, interaction, and testing improved enjoyment ( f = 0.546, p < 0.001), motivation ( f = 0.553, p < 0.0001), satisfaction with instruction ( f = 0.596, p < 0.00001), engagement ( f = 0.572, p < 0.00001) and active participation ( f = 0.563, p < 0.00001) (row 6). Similarly, compared to just being interactive with conversations, the combination of all three methods improved five out of six indicators, except for distraction in class (row 11).

Table 5. Comparison of combinations of asynchronous methods on student perceptions. Effect size (f).

Ordinal logistic regression was used to assess the likelihood that the platforms students used predicted student perceptions ( Supplementary Table 2 ). Platform choices were based on the answers to open-ended questions in the pre-test survey. The synchronous and asynchronous methods used were consistently more predictive of Likert responses than the specific platforms. Likewise, distraction continued to be our outlier with no differences across methods or platforms.

Students Prefer In-Person and Synchronous Online Learning Largely Due to Social-Emotional Reasoning

As expected, 86.1% (4,123) of survey participants report a preference for in-person courses, while 13.9% (666) prefer online courses. When asked to explain the reasons for their preference, students who prefer in-person courses most often mention the importance of social interaction (693 mentions), engagement (639 mentions), and motivation (440 mentions). These students are also more likely to mention a preference for a fixed schedule (185 mentions) vs. a flexible schedule (2 mentions).

In addition to identifying social reasons for their preference for in-person learning, students’ suggestions for improvements in online learning focus primarily on increasing interaction and engagement, with 845 mentions of live classes, 685 mentions of interaction, 126 calls for increased participation and calls for changes related to these topics such as, “Smaller teaching groups for live sessions so that everyone is encouraged to talk as some people don’t say anything and don’t participate in group work,” and “Make it less of the professor reading the pdf that was given to us and more interaction.”

Students who prefer online learning primarily identify independence and flexibility (214 mentions) and reasons related to anxiety and discomfort in in-person settings (41 mentions). Anxiety was only mentioned 12 times in the much larger group that prefers in-person learning.

The preference for synchronous vs. asynchronous modes of learning follows similar trends ( Table 6 ). Students who prefer live classes mention engagement and interaction most often while those who prefer recorded lectures mention flexibility.

Table 6. Most prevalent themes for students based on their preferred mode of remote learning.

Student Perceptions Align With Research on Active Learning

The first, and most robust, conclusion is that incorporation of active-learning methods correlates with more positive student perceptions of affect and engagement. We can see this clearly in the substantial differences on a number of measures, where students whose classes used only passive-learning techniques reported lower levels of engagement, satisfaction, participation, and motivation when compared with students whose classes incorporated at least some active-learning elements. This result is consistent with prior research on the value of active learning ( Freeman et al., 2014 ).

Though research shows that student learning improves in active learning classes, on campus, student perceptions of their learning, enjoyment, and satisfaction with instruction are often lower in active-learning courses ( Deslauriers et al., 2019 ). Our finding that students rate enjoyment and satisfaction with instruction higher for active learning online suggests that the preference for passive lectures on campus relies on elements outside of the lecture itself. That might include the lecture hall environment, the social physical presence of peers, or normalization of passive lectures as the expected mode for on-campus classes. This implies that there may be more buy-in for active learning online vs. in-person.

A second result from our survey is that student perceptions of affect and engagement are associated with students experiencing a greater diversity of learning modalities. We see this in two different results. First, in addition to the fact that classes that include active learning outperform classes that rely solely on passive methods, we find that on all measures besides distraction, the highest student ratings are associated with a combination of active and passive methods. Second, we find that these higher scores are associated with classes that make use of a larger number of different methods.

This second result suggests that students benefit from classes that make use of multiple different techniques, possibly invoking a combination of passive and active methods. However, it is unclear from our data whether this effect is associated specifically with combining active and passive methods, or if it is associated simply with the use of multiple different methods, irrespective of whether those methods are active, passive, or some combination. The problem is that the number of methods used is confounded with the diversity of methods (e.g., it is impossible for a classroom using only one method to use both active and passive methods). In an attempt to address this question, we looked separately at the effect of number and diversity of methods while holding the other constant. Across a large number of such comparisons, we found few statistically significant differences, which may be a consequence of the fact that each comparison focused on a small subset of the data.

Thus, our data suggests that using a greater diversity of learning methods in the classroom may lead to better student outcomes. This is supported by research on student attention span which suggests varying delivery after 10–15 min to retain student’s attention ( Bradbury, 2016 ). It is likely that this is more relevant for online learning where students report high levels of distraction across methods, modalities, and platforms. Given that number and variety are key, and there are few passive learning methods, we can assume that some combination of methods that includes active learning improves student experience. However, it is not clear whether we should predict that this benefit would come simply from increasing the number of different methods used, or if there are benefits specific to combining particular methods. Disentangling these effects would be an interesting avenue for future research.

Students Value Social Presence in Remote Learning

Student responses across our open-ended survey questions show a striking difference in reasons for their preferences compared with traditional online learners who prefer flexibility ( Harris and Martin, 2012 ; Levitz, 2016 ). Students reasons for preferring in-person classes and synchronous remote classes emphasize the desire for social interaction and echo the research on the importance of social presence for learning in online courses.

Short et al. (1976) outlined Social Presence Theory in depicting students’ perceptions of each other as real in different means of telecommunications. These ideas translate directly to questions surrounding online education and pedagogy in regards to educational design in networked learning where connection across learners and instructors improves learning outcomes especially with “Human-Human interaction” ( Goodyear, 2002 , 2005 ; Tu, 2002 ). These ideas play heavily into asynchronous vs. synchronous learning, where Tu reports students having positive responses to both synchronous “real-time discussion in pleasantness, responsiveness and comfort with familiar topics” and real-time discussions edging out asynchronous computer-mediated communications in immediate replies and responsiveness. Tu’s research indicates that students perceive more interaction with synchronous mediums such as discussions because of immediacy which enhances social presence and support the use of active learning techniques ( Gunawardena, 1995 ; Tu, 2002 ). Thus, verbal immediacy and communities with face-to-face interactions, such as those in synchronous learning classrooms, lessen the psychological distance of communicators online and can simultaneously improve instructional satisfaction and reported learning ( Gunawardena and Zittle, 1997 ; Richardson and Swan, 2019 ; Shea et al., 2019 ). While synchronous learning may not be ideal for traditional online students and a subset of our participants, this research suggests that non-traditional online learners are more likely to appreciate the value of social presence.

Social presence also connects to the importance of social connections in learning. Too often, current systems of education emphasize course content in narrow ways that fail to embrace the full humanity of students and instructors ( Gay, 2000 ). With the COVID-19 pandemic leading to further social isolation for many students, the importance of social presence in courses, including live interactions that build social connections with classmates and with instructors, may be increased.

Limitations of These Data

Our undergraduate data consisted of 4,789 responses from 95 different countries, an unprecedented global scale for research on online learning. However, since respondents were followers of @unjadedjade who focuses on learning and wellness, these respondents may not represent the average student. Biases in survey responses are often limited by their recruitment techniques and our bias likely resulted in more robust and thoughtful responses to free-response questions and may have influenced the preference for synchronous classes. It is unlikely that it changed students reporting on remote learning pedagogical methods since those are out of student control.

Though we surveyed a global population, our design was rooted in literature assessing pedagogy in North American institutions. Therefore, our survey may not represent a global array of teaching practices.

This survey was sent out during the initial phase of emergency remote learning for most countries. This has two important implications. First, perceptions of remote learning may be clouded by complications of the pandemic which has increased social, mental, and financial stresses globally. Future research could disaggregate the impact of the pandemic from students’ learning experiences with a more detailed and holistic analysis of the impact of the pandemic on students.

Second, instructors, students and institutions were not able to fully prepare for effective remote education in terms of infrastructure, mentality, curriculum building, and pedagogy. Therefore, student experiences reflect this emergency transition. Single-modality courses may correlate with instructors who lacked the resources or time to learn or integrate more than one modality. Regardless, the main insights of this research align well with the science of teaching and learning and can be used to inform both education during future emergencies and course development for online programs that wish to attract traditional college students.

Global Student Voices Improve Our Understanding of the Experience of Emergency Remote Learning

Our survey shows that global student perspectives on remote learning agree with pedagogical best practices, breaking with the often-found negative reactions of students to these practices in traditional classrooms ( Shekhar et al., 2020 ). Our analysis of open-ended questions and preferences show that a majority of students prefer pedagogical approaches that promote both active learning and social interaction. These results can serve as a guide to instructors as they design online classes, especially for students whose first choice may be in-person learning. Indeed, with the near ubiquitous adoption of remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, remote learning may be the default for colleges during temporary emergencies. This has already been used at the K-12 level as snow days become virtual learning days ( Aspergren, 2020 ).

In addition to informing pedagogical decisions, the results of this survey can be used to inform future research. Although we survey a global population, our recruitment method selected for students who are English speakers, likely majority female, and have an interest in self-improvement. Repeating this study with a more diverse and representative sample of university students could improve the generalizability of our findings. While the use of a variety of pedagogical methods is better than a single method, more research is needed to determine what the optimal combinations and implementations are for courses in different disciplines. Though we identified social presence as the major trend in student responses, the over 12,000 open-ended responses from students could be analyzed in greater detail to gain a more nuanced understanding of student preferences and suggestions for improvement. Likewise, outliers could shed light on the diversity of student perspectives that we may encounter in our own classrooms. Beyond this, our findings can inform research that collects demographic data and/or measures learning outcomes to understand the impact of remote learning on different populations.

Importantly, this paper focuses on a subset of responses from the full data set which includes 10,563 students from secondary school, undergraduate, graduate, or professional school and additional questions about in-person learning. Our full data set is available here for anyone to download for continued exploration: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId= doi: 10.7910/DVN/2TGOPH .

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

GS: project lead, survey design, qualitative coding, writing, review, and editing. TN: data analysis, writing, review, and editing. CN and PB: qualitative coding. JW: data analysis, writing, and editing. CS: writing, review, and editing. EV and KL: original survey design and qualitative coding. PP: data analysis. JB: original survey design and survey distribution. HH: data analysis. MP: writing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Minerva Schools at KGI for providing funding for summer undergraduate research internships. We also want to thank Josh Fost and Christopher V. H.-H. Chen for discussion that helped shape this project.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2021.647986/full#supplementary-material

Aspergren, E. (2020). Snow Days Canceled Because of COVID-19 Online School? Not in These School Districts.sec. Education. USA Today. Available online at: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/education/2020/12/15/covid-school-canceled-snow-day-online-learning/3905780001/ (accessed December 15, 2020).

Google Scholar

Bostock, S. J. (1998). Constructivism in mass higher education: a case study. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 29, 225–240. doi: 10.1111/1467-8535.00066

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bradbury, N. A. (2016). Attention span during lectures: 8 seconds, 10 minutes, or more? Adv. Physiol. Educ. 40, 509–513. doi: 10.1152/advan.00109.2016

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chen, B., Bastedo, K., and Howard, W. (2018). Exploring best practices for online STEM courses: active learning, interaction & assessment design. Online Learn. 22, 59–75. doi: 10.24059/olj.v22i2.1369

Davis, D., Chen, G., Hauff, C., and Houben, G.-J. (2018). Activating learning at scale: a review of innovations in online learning strategies. Comput. Educ. 125, 327–344. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2018.05.019

Deslauriers, L., McCarty, L. S., Miller, K., Callaghan, K., and Kestin, G. (2019). Measuring actual learning versus feeling of learning in response to being actively engaged in the classroom. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 19251–19257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1821936116

Fink, L. D. (2013). Creating Significant Learning Experiences: An Integrated Approach to Designing College Courses. Somerset, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.

Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., et al. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, 8410–8415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319030111

Gale, N. K., Heath, G., Cameron, E., Rashid, S., and Redwood, S. (2013). Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 13:117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., and Archer, W. (1999). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: computer conferencing in higher education. Internet High. Educ. 2, 87–105. doi: 10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00016-6

Gay, G. (2000). Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, Research, and Practice. Multicultural Education Series. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Gillingham, and Molinari, C. (2012). Online courses: student preferences survey. Internet Learn. 1, 36–45. doi: 10.18278/il.1.1.4

Gillis, A., and Krull, L. M. (2020). COVID-19 remote learning transition in spring 2020: class structures, student perceptions, and inequality in college courses. Teach. Sociol. 48, 283–299. doi: 10.1177/0092055X20954263

Goodyear, P. (2002). “Psychological foundations for networked learning,” in Networked Learning: Perspectives and Issues. Computer Supported Cooperative Work , eds C. Steeples and C. Jones (London: Springer), 49–75. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4471-0181-9_4

Goodyear, P. (2005). Educational design and networked learning: patterns, pattern languages and design practice. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 21, 82–101. doi: 10.14742/ajet.1344

Gunawardena, C. N. (1995). Social presence theory and implications for interaction and collaborative learning in computer conferences. Int. J. Educ. Telecommun. 1, 147–166.

Gunawardena, C. N., and Zittle, F. J. (1997). Social presence as a predictor of satisfaction within a computer mediated conferencing environment. Am. J. Distance Educ. 11, 8–26. doi: 10.1080/08923649709526970

Harris, H. S., and Martin, E. (2012). Student motivations for choosing online classes. Int. J. Scholarsh. Teach. Learn. 6, 1–8. doi: 10.20429/ijsotl.2012.060211

Levitz, R. N. (2016). 2015-16 National Online Learners Satisfaction and Priorities Report. Cedar Rapids: Ruffalo Noel Levitz, 12.

Mansinghka, V., Shafto, P., Jonas, E., Petschulat, C., Gasner, M., and Tenenbaum, J. B. (2016). CrossCat: a fully Bayesian nonparametric method for analyzing heterogeneous, high dimensional data. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 17, 1–49. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-69765-9_7

National Research Council (2000). How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School: Expanded Edition. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, doi: 10.17226/9853

Richardson, J. C., and Swan, K. (2019). Examining social presence in online courses in relation to students’ perceived learning and satisfaction. Online Learn. 7, 68–88. doi: 10.24059/olj.v7i1.1864

Shea, P., Pickett, A. M., and Pelz, W. E. (2019). A Follow-up investigation of ‘teaching presence’ in the suny learning network. Online Learn. 7, 73–75. doi: 10.24059/olj.v7i2.1856

Shekhar, P., Borrego, M., DeMonbrun, M., Finelli, C., Crockett, C., and Nguyen, K. (2020). Negative student response to active learning in STEM classrooms: a systematic review of underlying reasons. J. Coll. Sci. Teach. 49, 45–54.

Short, J., Williams, E., and Christie, B. (1976). The Social Psychology of Telecommunications. London: John Wiley & Sons.

Tu, C.-H. (2002). The measurement of social presence in an online learning environment. Int. J. E Learn. 1, 34–45. doi: 10.17471/2499-4324/421

Zull, J. E. (2002). The Art of Changing the Brain: Enriching Teaching by Exploring the Biology of Learning , 1st Edn. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

Keywords : online learning, COVID-19, active learning, higher education, pedagogy, survey, international

Citation: Nguyen T, Netto CLM, Wilkins JF, Bröker P, Vargas EE, Sealfon CD, Puthipiroj P, Li KS, Bowler JE, Hinson HR, Pujar M and Stein GM (2021) Insights Into Students’ Experiences and Perceptions of Remote Learning Methods: From the COVID-19 Pandemic to Best Practice for the Future. Front. Educ. 6:647986. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.647986

Received: 30 December 2020; Accepted: 09 March 2021; Published: 09 April 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Nguyen, Netto, Wilkins, Bröker, Vargas, Sealfon, Puthipiroj, Li, Bowler, Hinson, Pujar and Stein. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Geneva M. Stein, [email protected]

This article is part of the Research Topic

Covid-19 and Beyond: From (Forced) Remote Teaching and Learning to ‘The New Normal’ in Higher Education

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

On online learning and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: Perspectives from the Philippines

The negative mental health consequences of online learning among students can include increased anxiety and absenteeism. These can stem from the increased demand for new technological skills, productivity, and information overload ( Poalses and Bezuidenhout, 2018 ). The COVID-19 pandemic worsened these consequences when educational institutions shifted from face-to-face activities to mostly online learning modalities to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 ( Malolos et al., 2021 ). While all students may be affected, students from lower socioeconomic localities have higher mental distress due to their limited financial capacity to obtain the necessary gadgets and internet connectivity. Given these, a digital divide stemming from socioeconomic inequalities can result in mental health disparities among students during the pandemic ( Cleofas and Rocha, 2021 ). In a recent article, Hou et al. (2020) noted that young Chinese students from resource-scarce localities may be at risk for mental disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic due to social and cultural factors. Similar observations were noted in the Philippines, a developing and resource-scarce country. Children had a higher risk for poor mental health compared to adults in the Philippines partly due to their shift to online learning modalities during the pandemic ( Malolos et al., 2021 ). Thus, measures cognizant of the resources of a developing country are needed to mitigate the mental stresses from online learning including videoconferencing.

1. Open cameras only when necessary

Adopting new technologies generally is not easy. Users of videoconferencing technologies for synchronous online learning activities have found it mentally exhausting ( Bailenson, 2021 ). To combat this exhaustion, several suggestions by authors from a study in the United States included the opening of cameras to be visible to other students in the videoconference ( Peper et al., 2021 ). While this suggestion might be feasible in developed countries with good internet connectivity, this may pose an additional mental health burden to developing nations with unstable internet connections. It was found that connectivity errors and constantly seeing one’s self during videoconferencing had resulted in high stress levels and poor mental health among students ( Dhawan, 2020 ). Thus, these opening of cameras may pose as an additional source of mental health burden rather than wellbeing in developing nations. Instead, it might be helpful to ask students to open their cameras during videoconference only when necessary.

2. Avoid requiring school uniforms during online classes

It was also recommended to reenact the work and study environment at home including the wearing of school clothing ( Peper et al., 2021 ). This recommendation might be better suited in countries with high economic and financial resources. In developing and resource-scarce areas such as the Philippines, wearing school uniforms may pose an additional financial burden to an already economically constrained population as a result of economic and social lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic ( Hou et al., 2020 , Malolos et al., 2021 ). Thus, it may be imperative to avoid requiring school uniforms during online classes to alleviate the economic cost of its maintenance. In doing so, additional worries and stresses from the pandemic’s economic burden can be reduced.

3. Take regular classroom breaks and avoid multitasking

To improve concentration and burnout from online learning activities, it was also recommended to avoid multitasking and take a break regularly every thirty minutes. Doing these may also lower mental stresses and screen fatigue in long videoconferencing sessions ( Peper et al., 2021 ). To do these, curricular learning activities can be modified to include regular breaks and focused activities.

4. Mental health promotion training for teachers

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, several studies have noted that it is necessary to improve teachers’ attitudes, beliefs, and behavior towards mental illness to foster a mentally healthy school environment. This has been previously done through mental health literacy campaigns, workshops, and seminars ( Weist et al., 2017 ). With the possible increase of mental health burden among young students and limited mental health resources in the setting of developing countries such as the Philippines ( Malolos et al., 2021 ), it might be necessary to renew the efforts on these mental health promotion activities among teachers.

5. Promote self-care activities

Developing nations, such as the Philippines, often have scarce mental health resources ( Malolos et al., 2021 , World Health Organization, 2019 ). Due to this scarcity, self-care activities may be the only option for some people to maintain their mental wellbeing and avoid poor mental health ( World Health Organization, 2019 ). In promoting self-care, it is important to ensure adequate attention is paid to the body, mind, family, and environment. Thus, it is important to promote regular exercise and relaxing activities during breaks from online classes. Likewise, it is important to remind young students to foster a good social relationship with friends and loved ones despite the physical distance during the pandemic ( World Health Organization, 2013 ). Doing these, may not only promote mental health but reduce the risk factors associated with poor mental health ( World Health Organization, 2019 ). Thus, self-care in developing nations may be ever more crucial.

Generally, learning that considers the child's mental health should take cognizance of the circumstances that children faced in their daily social environment. While there is evidence that specific actions contribute to better mental health among children, the outcomes are contingent on context. In the case of a developing country context, teaching children in the COVID-19 era requires the consideration of existing social inequalities and economic constraints to safeguard their mental health in the online learning environment.

Financial disclosure

The author has not received any financial support for this article.

Declaration of Competing Interest

No conflict of interest exists in the submission of this manuscript. The author declare that he has no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

- Bailenson J.N. Nonverbal overload: a theoretical argument for the causes of Zoom fatigue. Technol. Mind Behav. 2021; 2 (1) doi: 10.1037/tmb0000030. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cleofas J.V., Rocha I.C.N. Demographic, gadget and internet profiles as determinants of disease and consequence related COVID-19 anxiety among Filipino college students. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s10639-021-10529-9. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dhawan S. Online learning: a panacea in the time of COVID-19 crisis. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 2020; 49 (1):5–22. doi: 10.1177/0047239520934018. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hou T.Y., Mao X.F., Dong W., Cai W.P., Deng G.H. Prevalence of and factors associated with mental health problems and suicidality among senior high school students in rural China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Asian J. Psychiatry. 2020; 54 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102305. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Malolos G.Z.C., Baron M.B.C., Apat F.A.J., Sagsagat H.A.A., Bianca P., Pasco M., Aportadera E.T.C.L., Tan R.J.D., Gacutno-Evardone A.J., D.E L.P., III Mental health and well-being of children in the Philippine setting during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Promot. 2021; 11 (3):2. doi: 10.34172/hpp.2021.xx. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Peper E., Wilson V., Martin M., Rosegard E., Harvey R. Avoid Zoom fatigue, be present and learn. NeuroRegulation. 2021; 8 (1):47. doi: 10.15540/nr.8.1.47. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Poalses J., Bezuidenhout A. Mental health in higher education: a comparative stress risk assessment at an open distance learning university in South Africa. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2018; 19 (2) doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v19i2.3391. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Weist M.D., Bruns E.J., Whitaker K., Wei Y., Kutcher S., Larsen T., Holsen I., Cooper J.L., Geroski A., Short K.H. School mental health promotion and intervention: Experiences from four nations. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2017; 38 (4):343–362. doi: 10.1177/0143034317695379. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- World Health Organization. 2013. Self Care for Health. World Health Organization (accessed on 2021 August 12). Available from: 〈https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/205887/B5084.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y〉 .

- World Health Organization. 2019. Self-care can be an effective part of national health systems. World Health Organization (accessed on 2021 August 12]). Available from: 〈https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/self-care-national-health-systems/en/#:~:text=What%20is%20meant%20by%20%E2%80%9Cself,a%20health%2Dcare%20provider.%E2%80%9D〉 .

Open Access is an initiative that aims to make scientific research freely available to all. To date our community has made over 100 million downloads. It’s based on principles of collaboration, unobstructed discovery, and, most importantly, scientific progression. As PhD students, we found it difficult to access the research we needed, so we decided to create a new Open Access publisher that levels the playing field for scientists across the world. How? By making research easy to access, and puts the academic needs of the researchers before the business interests of publishers.

We are a community of more than 103,000 authors and editors from 3,291 institutions spanning 160 countries, including Nobel Prize winners and some of the world’s most-cited researchers. Publishing on IntechOpen allows authors to earn citations and find new collaborators, meaning more people see your work not only from your own field of study, but from other related fields too.

Brief introduction to this section that descibes Open Access especially from an IntechOpen perspective

Want to get in touch? Contact our London head office or media team here

Our team is growing all the time, so we’re always on the lookout for smart people who want to help us reshape the world of scientific publishing.

Home > Books > E-Learning and Digital Education in the Twenty-First Century

The Impact of Online Learning Strategies on Students’ Academic Performance

Submitted: 01 September 2020 Reviewed: 11 October 2020 Published: 18 May 2022

DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.94425

Cite this chapter

There are two ways to cite this chapter:

From the Edited Volume

E-Learning and Digital Education in the Twenty-First Century

Edited by M. Mahruf C. Shohel

To purchase hard copies of this book, please contact the representative in India: CBS Publishers & Distributors Pvt. Ltd. www.cbspd.com | [email protected]

Chapter metrics overview

2,413 Chapter Downloads

Impact of this chapter

Total Chapter Downloads on intechopen.com

Total Chapter Views on intechopen.com

Higher education institutions have shifted from traditional face to face to online teaching due to Corona virus pandemic which has forced both teachers and students to be put in a compulsory lockdown. However the online teaching/learning constitutes a serious challenge that both university teachers and students have to face, as it necessarily requires the adoption of different new teaching/learning strategies to attain effective academic outcomes, imposing a virtual learning world which involves from the students’ part an online access to lectures and information, and on the teacher’s side the adoption of a new teaching approach to deliver the curriculum content, new means of evaluation of students’ personal skills and learning experience. This chapter explores and assesses the online teaching and learning impact on students’ academic achievement, encompassing the passing in review the adoption of students’ research strategies, the focus of the students’ main source of information viz. library online consultation and the collaboration with their peers. To reach this end, descriptive and parametric analyses are conducted in order to identify the impact of these new factors on students’ academic performance. The findings of the study shows that to what extent the students’ online learning has or has not led to any remarkable improvements in the students’ academic achievements and, whether or not, to any substantial changes in their e-learning competence. This study was carried out on a sample of University College (UAEU) students selected in Spring 2019 and Fall 2020.

- online learning environment

- content-based research

- process-based research

- success factors assessment

Author Information

Khaled hamdan *.

- UAEU-University College, UAE

Abid Amorri

*Address all correspondence to: [email protected]

1. Introduction

With the advent of COVID-19 pandemic and the shutdown of universities worldwide for fear of contamination due to the spread of the coronavirus, higher educational institutions have deemed necessary to adopt new teaching strategies, exclusively online, to deliver their curriculum content and keep from the Corona virus widespread at bay [ 1 ]. Technology was called upon to play this pivotal teaching/learning online role, as it has influenced people’s task accomplishment in various ways. It has become a part of our ever changing lives. It is an important part of e-learning to create relationship-involving technology, course content and pedagogy in learning/teaching environment. Therefore, e-learning is becoming unavoidable in a virtual teaching environment where students can take control of their learning and optimize it in a virtual classroom and elsewhere. So, learning today has shifted from the conventional face to face learning to online learning and to a direct access to information through technologies available as e-learning has proven to be more beneficial to students in terms of knowledge or information acquisition. Online teaching promotes learning by encouraging the students’ use of various learning strategies at hand and increases the level of their commitment to studying their majors. Virtual world represents an effective learning environment, providing users with an experience-based information acquisition. Instructors set up the course outcomes by creating tasks involving problem or challenge-based learning situations and offering the learner a full control of exploratory learning experiences. However, there are some challenges for instructors such as the selection of the most appropriate educational strategies and how best to design learning tasks and activities to meet learners’ needs and expectations. Various approaches can lead towards strong students’ behavioral changes especially when combined with ethical principles. However, with careful selection of the learning environment, pedagogical strategies lining up with the concrete specifics of the educational context, the building of learners’ self-confidence and their empowerment during the learning process becomes within reach. Another benefit of using online teaching/learning is that here is a need to explore new teaching strategies and principles that positively influence distance education, as traditional teaching/learning methods are becoming less effective at engaging students in the learning process. Finally, e-learning can solve many of the students’ learning issues in a conventional learning environment, as it helps them to attend classes for various reasons, as it has made the communication/interaction between them and their instructors much easier and the access to lectures much more at hand. Students can attend online university courses and at the same time meet other social obligations. Therefore, the circumstances in a learner’s life, and whatever problems or distraction he/she may have such as family problems or illnesses, may no longer be an impediment to his education. Learners can practice in virtual situations and face challenges in a safe environment, which leads to a more engaged learning experience that facilitates better knowledge acquisition.

The work presents the educational processes as a modern strategy for teaching/learning. e-learning tends to persuade the users to be virtually available to act naturally. There are a few factors affecting the outcomes such as learning aims and objectives, and different pedagogical choices. Instructors use various factors to measure the learning quality like Competence, Attitude, Content Delivery, Reliability, and Globalization [ 2 , 3 , 4 ]. In this work, we are going to pass in review positive and negative impacts of online learning followed by recommendations to increase awareness regarding online learning and the use of this new strategic technology. Modern teaching methods like brainstorming, problem solving, indirect-consultancy, and inquiry-based method have a significant effect in the educational progress [ 5 ].

The aim of this research is to examine the effect of using modern teaching methods, such as teacher-student interactive and student-centered methods, on students’ academic performance. Factors that may affect students’ performance and success- the technology used, students’ collaboration/teamwork, time management and communication skills are taken into consideration [ 6 ]. It also attempts to identify and to show to what extent online learning environment, when well integrated and adapted in course planning and objectives, can cater for students’ needs and wants. Does online teaching make a significant improvement in students’ academic performance and their personal skills such as organizations, communications, responsibilities, problem-solving tasks, engagement, learning interest, self-evolution, and abilities to reach their potential? Is students’ struggle is not purely academic, but rather related to the lack of personal skills?

2. Online learning experience

There are many motives behind the implementation of the online learning experience. The online learning is mandatory nowadays to all audience due to COVID −19 pandemic, which forced the higher educational authorities to start the online teaching [ 1 ]. We believe that we reached a tipping point where making changes to the current learning process is inevitable for many reasons. Today learners have instant access to information through technology and the web, can manage their own acquisition of knowledge through online learning. As a result, traditional teaching and learning methods are becoming less effective at engaging students, who no longer rely exclusively on the teacher as the only source of knowledge. Indeed, 90% of the respondents use internet as their major source of information. So the teacher is new role is to be a learning facilitator, a guide for his students. He should not only help his students locate information, but more importantly question it and reflect upon it and formulate an opinion about it. Another reason for the adoption of the online learning is that higher institution did not hesitate one moment to integrate it as a primary tool of education. So, it transformed the conventional course and current learning process into e-learning concept. The integration of the online teaching into the curriculum resulted in several issues to instructors, curriculum designer and administrators, starting from the infrastructure to online teaching and assessment. Does the current IT infrastructure support this integration? What course content should the instructor teach and how it should be delivered? What effective pedagogy needs to be adopted? How learning should be assessed? What is the direct effect of the online learning on students’ performance? [ 7 ].

With reference to the survey findings, the majority of students were among the staunch supporters of online learning taking into consideration the imposed COVID-19 lockdown circumstances, as they expressed their full support and confidence in computer skills to share digital content, using online learning and collaboration platforms with their peers, and expressed their satisfaction with the support of the online teaching and learning [ 8 ].

However, a small percentage of the survey respondents, expressed their below average satisfaction when higher educational institutions have invested in digital literacy and infrastructure, as they believe they should provide more flexible delivery methods, digital platforms and modernized user-friendly curricula to both students and teachers [ 9 ]. On the same lines, the higher education authorities regard the quick and unexpected development of the UAE’s higher education landscape, ICT infrastructure, and advanced online learning/teaching methods, imposed by COVID-19, have had a tremendous adverse impact on the students’ culture, thus leading to students’ social seclusion from their peers, imposing new social norms and behavior regarding plagiarism, affecting students’ cultural ethics and learning and collaboration with their peers, when adopting the digital culture [ 10 ].

A current study emphasized the need for adoption of technology in education as a way to lessen the effects of Coronavirus pandemic lockdown in education to palliate the loss of face- to- face teaching/learning which has more beneficial aspects of learning for students than online learning as it offers more interactive learning opportunities.

We recommend that all these questions should be taken into consideration when designing a new course i.e. the e-learning strategies, the learners’ and instructor’s new roles, course content and pedagogy and students’ performance/achievement assessment ( Figure 1 ). In this experience, we focus only on the implementation of new learning academic objectives- how they are infused into the curriculum and how they are assessed. The ultimate objective of implementing a new learning process is to design a curriculum conveyed by a creative pedagogy and oriented towards the cultivation of a creative person yearning for the exploration of new ideas [ 11 ]. The afore-mentioned objectives lead to design a comprehensive learning experience with new learning outcomes where instructors infuse new practical skills - Critical thinking and Problem-Solving Tasks, Creativity and Innovation, Communication and Collaboration. Other skills are implicitly infused into the curriculum such as, self-independent learning, interdependence, lifelong learning, flexibility, adaptability, and assuming academic learning responsibilities. Online learning is defined as virtual learning using mobile and wireless computing technologies in a way to promote learners’ learning abilities [ 12 ]. In ( Figure 2 ), each component of the e-learning process is defined clearly below [ 13 ].

E-learning approach.

E-learning process.

2.1 Active instructor

His role is to facilitate learning process in the virtual classroom, to engage students in the learning process, to allow them to participate in designing their own course content and to contribute to design learning assessment parameters.

2.2 Active learner

He can access course content anytime and from anywhere, engage with his peers in a collaborative environment, formulate his opinions continuously, interact with other learning communities, communicate effectively, share and publish their findings with others in online environment.

2.3 Creative pedagogy

Both instructors and learners decide on what to learn online and how it should be learned. This experience is designed to promote an inquiry and challenge-based learning models where teachers and students work together to learn about compelling issues, propose solutions to real problems and take actions [ 11 ]. The approach involves students to reflect on their learning, on the impact of their actions and to publish their solutions to a worldwide audience [ 14 ].

2.4 Flexible curriculum

A core curriculum is designed, but the facilitator has the freedom to innovate and customize course content accordingly up to the aspiration of the learners; this means that the learner’s knowledge of the material will mainly come from his own online research (formal and informal content), and from his own creativity and collaboration with his peers (teamwork).

2.5 Communities outreach

This allows a group of students to formulate real-world context research question, connect with local learning and global communities to find creative solutions to their problems, create opportunities to connect themselves with international communities. These opportunities will foster students’ social and leadership skills [ 15 ].

According to students’ observation, more than 70% of instructors found that the online learning using Blackboard ultra-collaboration boosts students’ learning interest, engagement and motivation. 84% of teachers use required to use interactive tools in order to engage students in presenting and sharing a five minutes presentation to their classmates, write a reflective essay on their experience, be involved in a collaborative project (interest- based learning project). 97% of students contributed to self and peer assessments, and 97% interacted using online management systems. Students were also encouraged to interact with their peers using blackboard group collaborate. Thanks to the online teaching strategy, 70% of students were able to deliver on time their work.

For the study purpose, several assessments components incorporate both individual and group work. For the individual work, each student was required to make an individual presentation on any subject of his own interest, write a reflective essay, self -assessment, class peer assessment, midterm and final exams. For the collaborative work, students were assigned teams and each student should contribute to the project delivered every two weeks in the form of a final presentation and a final project. Rubrics were designed and all students were well instructed to use them. Teachers were trained to monitor and facilitate the experience and the internal learning management systems such as Blackboard.

The subsequent ( Figure 3 ) shows the feedback loop of content mapping of factors and their relationships in relation to students’ performance and intake. The first feedback loop begins at the node called “Students”. The second one begins at the node entitled “Teacher”. There are two major positive feedback loops. For instance, a good team improves co-operation and creativity which increase the team’s learning experience. Setting clear goals and interactive strategies will enhance online learning and performance results. The E-learning process and the project outcomes are influenced by technology use [ 13 ].

Conceptual model of students’ E-learning environment parameters.

3. Research methodology

We studied the impact of online learning using technology in virtual classrooms and the effect of performance factors on students’ learning behavior and achievement. The study focused on a sample of 6045 students, collected from the enrolment of University College students in spring 2020, at United Arab Emirates University has used online teaching strategy in comparison to fall 2019 teaching/learning experience, which used conventional teaching strategy involving 7369 students (See Table 1 ). The study shows the learning outcomes are similar for both virtual and conventional learning, although the assessment methods are different. They include students’ learning outcomes assessment, testing (assessing prior and post knowledge acquisition) and quantitative versus conventional research. The findings of the survey are discussed below. Descriptive statistics were obtained to summarize the sample characteristics and performance variables. Pearson Correlation was used to evaluate the association between the learning outcomes dimensions. Independent Samples t-test was used to compare the mean overall performance of the online learning. Linear Regression was used to determine the impact of the learning characteristics (Critical thinking, Creativity, Communication and Collaboration) on the overall performance score. Factor Analysis was used to study the inter-relationships among the learning characteristics and compare the online methods.

Students’ population.

The objectives of the learning process consist of providing a diversified learning environment. The positive impact of this diversity is reflected in the students’ performance. Students in various represented colleges have similar passing grades as high (80–98%) for both Online Approach (OLA) and Conventional learning -Face-to-Face (FoF). The University College is the largest college in the University with more than 4000 students. Most of UAEU students start their study in UC; they take English, Arabic, IT and Math ( Figure 4 ).

University college percentage passing rate.

This study was limited to GEIL101 foundation students. Surveys were sent out to all information literacy sections at the end of the first semester 2019/2020, but there were only 87 respondents. The survey had 2 parts, one part is about students’ achievement/performance, and the second part use is about online learning in a virtual classroom. All sessions were conducted online by trained instructors in tandem with the University library delivered by professional librarians. In this report, fall 2019 students’ data are used as the sample for the study ( Table 2 ).

GEIL students.

Overall, the results indicate the online learning was beneficial for students as it shown in their academic achievements and in tables below. A significant number of students reported high comfort levels of attending online courses in virtual classroom instead of conventional learning. Results indicated students have a positive reception to online approach rather than traditional classrooms. Additionally, qualitative data identified a clearconsiderations for the integration of new technology into the new teaching and learning experience.

4. E-learning results and analyses

Table 3 shows the IL students’ pre and post tests performance. The analysis on the pre and post-tests, using the means comparison and one sample test, shows an increase of students’ performance by 84%, the mean of the pre-test is around 7.5 and the post test is 13.85, a significant difference of 6.35. 65% of students score above 60% (passing rate for the course) in the post-test, only 2.4% of students scored above 60% in the pre-test. This means that 97.6% of students did not have basic information literacy knowledge, but after going through intensive 12 week learning under e-learning conditions, 65% achieved the course outcomes with higher scores.

Students’ academic performance.

The following tables ( Tables 3 and 4 ) shows the students’ performance by each learning activity:

Students’ learning activity.

The scores in the post-test ranged between 11 and 20, whereas it ranged between 6 to 9 in the pre-test ( Figure 5 ).

Pre and post-tests comparison distribution.

The above results show that OLA students scored higher than the FoF in the majority of the learning activities. There is an important performance of online students in the midterm and final exams though both approaches where offered the similar assessments criteria under the same test conditions. In the next section, the online learning process validity, the learning activities, and the learning outcome achievements, will be discussed in greater details. Several statistical models, qualitative and quantitative analysis have been applied for this purpose.

5. Impact analysis of the learning activities