Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is an Observational Study? | Guide & Examples

What Is an Observational Study? | Guide & Examples

Published on March 31, 2022 by Tegan George . Revised on June 22, 2023.

An observational study is used to answer a research question based purely on what the researcher observes. There is no interference or manipulation of the research subjects, and no control and treatment groups .

These studies are often qualitative in nature and can be used for both exploratory and explanatory research purposes. While quantitative observational studies exist, they are less common.

Observational studies are generally used in hard science, medical, and social science fields. This is often due to ethical or practical concerns that prevent the researcher from conducting a traditional experiment . However, the lack of control and treatment groups means that forming inferences is difficult, and there is a risk of confounding variables and observer bias impacting your analysis.

Table of contents

Types of observation, types of observational studies, observational study example, advantages and disadvantages of observational studies, observational study vs. experiment, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions.

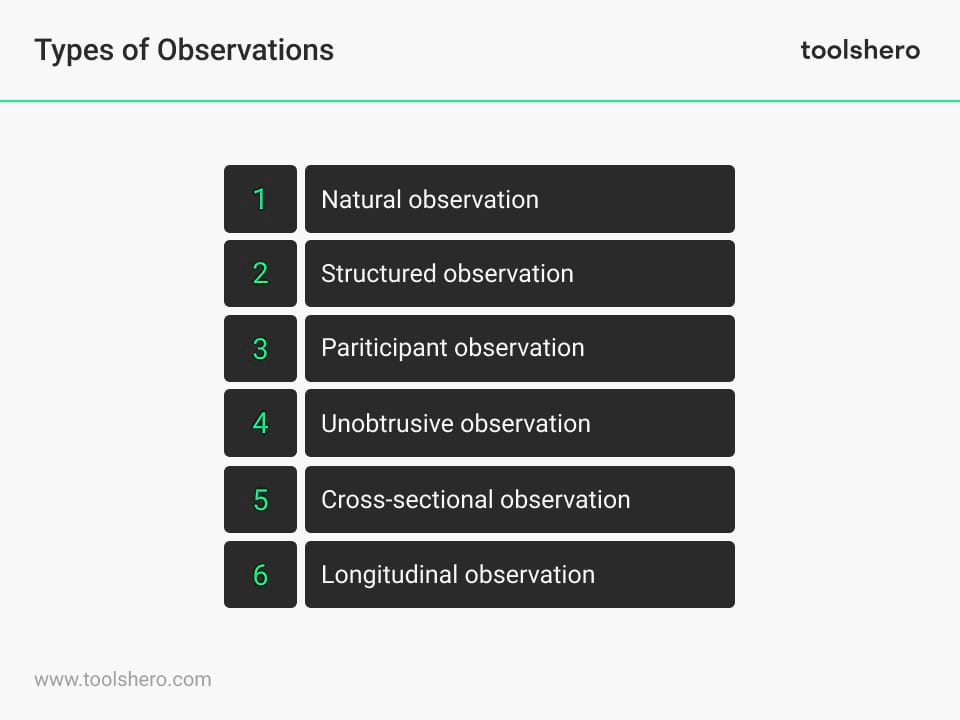

There are many types of observation, and it can be challenging to tell the difference between them. Here are some of the most common types to help you choose the best one for your observational study.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

There are three main types of observational studies: cohort studies, case–control studies, and cross-sectional studies .

Cohort studies

Cohort studies are more longitudinal in nature, as they follow a group of participants over a period of time. Members of the cohort are selected because of a shared characteristic, such as smoking, and they are often observed over a period of years.

Case–control studies

Case–control studies bring together two groups, a case study group and a control group . The case study group has a particular attribute while the control group does not. The two groups are then compared, to see if the case group exhibits a particular characteristic more than the control group.

For example, if you compared smokers (the case study group) with non-smokers (the control group), you could observe whether the smokers had more instances of lung disease than the non-smokers.

Cross-sectional studies

Cross-sectional studies analyze a population of study at a specific point in time.

This often involves narrowing previously collected data to one point in time to test the prevalence of a theory—for example, analyzing how many people were diagnosed with lung disease in March of a given year. It can also be a one-time observation, such as spending one day in the lung disease wing of a hospital.

Observational studies are usually quite straightforward to design and conduct. Sometimes all you need is a notebook and pen! As you design your study, you can follow these steps.

Step 1: Identify your research topic and objectives

The first step is to determine what you’re interested in observing and why. Observational studies are a great fit if you are unable to do an experiment for practical or ethical reasons , or if your research topic hinges on natural behaviors.

Step 2: Choose your observation type and technique

In terms of technique, there are a few things to consider:

- Are you determining what you want to observe beforehand, or going in open-minded?

- Is there another research method that would make sense in tandem with an observational study?

- If yes, make sure you conduct a covert observation.

- If not, think about whether observing from afar or actively participating in your observation is a better fit.

- How can you preempt confounding variables that could impact your analysis?

- You could observe the children playing at the playground in a naturalistic observation.

- You could spend a month at a day care in your town conducting participant observation, immersing yourself in the day-to-day life of the children.

- You could conduct covert observation behind a wall or glass, where the children can’t see you.

Overall, it is crucial to stay organized. Devise a shorthand for your notes, or perhaps design templates that you can fill in. Since these observations occur in real time, you won’t get a second chance with the same data.

Step 3: Set up your observational study

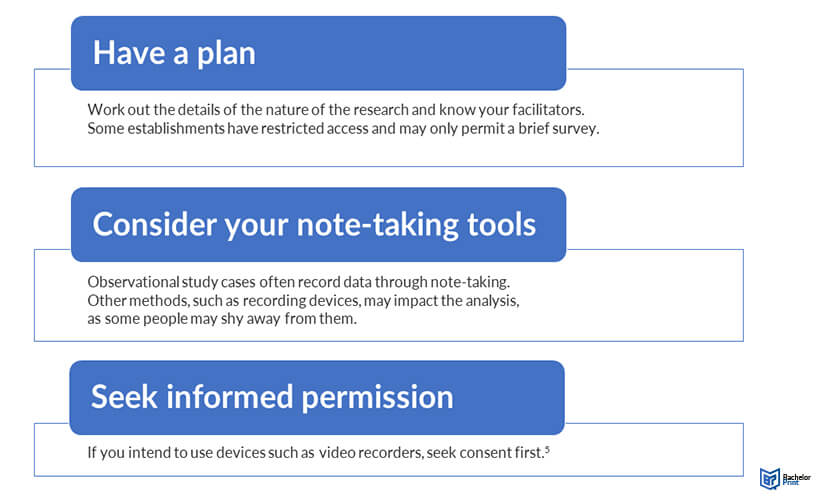

Before conducting your observations, there are a few things to attend to:

- Plan ahead: If you’re interested in day cares, you’ll need to call a few in your area to plan a visit. They may not all allow observation, or consent from parents may be needed, so give yourself enough time to set everything up.

- Determine your note-taking method: Observational studies often rely on note-taking because other methods, like video or audio recording, run the risk of changing participant behavior.

- Get informed consent from your participants (or their parents) if you want to record: Ultimately, even though it may make your analysis easier, the challenges posed by recording participants often make pen-and-paper a better choice.

Step 4: Conduct your observation

After you’ve chosen a type of observation, decided on your technique, and chosen a time and place, it’s time to conduct your observation.

Here, you can split them into case and control groups. The children with siblings have a characteristic you are interested in (siblings), while the children in the control group do not.

When conducting observational studies, be very careful of confounding or “lurking” variables. In the example above, you observed children as they were dropped off, gauging whether or not they were upset. However, there are a variety of other factors that could be at play here (e.g., illness).

Step 5: Analyze your data

After you finish your observation, immediately record your initial thoughts and impressions, as well as follow-up questions or any issues you perceived during the observation. If you audio- or video-recorded your observations, you can transcribe them.

Your analysis can take an inductive or deductive approach :

- If you conducted your observations in a more open-ended way, an inductive approach allows your data to determine your themes.

- If you had specific hypotheses prior to conducting your observations, a deductive approach analyzes whether your data confirm those themes or ideas you had previously.

Next, you can conduct your thematic or content analysis . Due to the open-ended nature of observational studies, the best fit is likely thematic analysis .

Step 6: Discuss avenues for future research

Observational studies are generally exploratory in nature, and they often aren’t strong enough to yield standalone conclusions due to their very high susceptibility to observer bias and confounding variables. For this reason, observational studies can only show association, not causation .

If you are excited about the preliminary conclusions you’ve drawn and wish to proceed with your topic, you may need to change to a different research method , such as an experiment.

- Observational studies can provide information about difficult-to-analyze topics in a low-cost, efficient manner.

- They allow you to study subjects that cannot be randomized safely, efficiently, or ethically .

- They are often quite straightforward to conduct, since you just observe participant behavior as it happens or utilize preexisting data.

- They’re often invaluable in informing later, larger-scale clinical trials or experimental designs.

Disadvantages

- Observational studies struggle to stand on their own as a reliable research method. There is a high risk of observer bias and undetected confounding variables or omitted variables .

- They lack conclusive results, typically are not externally valid or generalizable, and can usually only form a basis for further research.

- They cannot make statements about the safety or efficacy of the intervention or treatment they study, only observe reactions to it. Therefore, they offer less satisfying results than other methods.

The key difference between observational studies and experiments is that a properly conducted observational study will never attempt to influence responses, while experimental designs by definition have some sort of treatment condition applied to a portion of participants.

However, there may be times when it’s impossible, dangerous, or impractical to influence the behavior of your participants. This can be the case in medical studies, where it is unethical or cruel to withhold potentially life-saving intervention, or in longitudinal analyses where you don’t have the ability to follow your group over the course of their lifetime.

An observational study may be the right fit for your research if random assignment of participants to control and treatment groups is impossible or highly difficult. However, the issues observational studies raise in terms of validity , confounding variables, and conclusiveness can mean that an experiment is more reliable.

If you’re able to randomize your participants safely and your research question is definitely causal in nature, consider using an experiment.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Student’s t -distribution

- Normal distribution

- Null and Alternative Hypotheses

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Data cleansing

- Reproducibility vs Replicability

- Peer review

- Prospective cohort study

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Placebo effect

- Hawthorne effect

- Hindsight bias

- Affect heuristic

- Social desirability bias

An observational study is a great choice for you if your research question is based purely on observations. If there are ethical, logistical, or practical concerns that prevent you from conducting a traditional experiment , an observational study may be a good choice. In an observational study, there is no interference or manipulation of the research subjects, as well as no control or treatment groups .

The key difference between observational studies and experimental designs is that a well-done observational study does not influence the responses of participants, while experiments do have some sort of treatment condition applied to at least some participants by random assignment .

A quasi-experiment is a type of research design that attempts to establish a cause-and-effect relationship. The main difference with a true experiment is that the groups are not randomly assigned.

Exploratory research aims to explore the main aspects of an under-researched problem, while explanatory research aims to explain the causes and consequences of a well-defined problem.

Experimental design means planning a set of procedures to investigate a relationship between variables . To design a controlled experiment, you need:

- A testable hypothesis

- At least one independent variable that can be precisely manipulated

- At least one dependent variable that can be precisely measured

When designing the experiment, you decide:

- How you will manipulate the variable(s)

- How you will control for any potential confounding variables

- How many subjects or samples will be included in the study

- How subjects will be assigned to treatment levels

Experimental design is essential to the internal and external validity of your experiment.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. (2023, June 22). What Is an Observational Study? | Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/observational-study/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, what is a research design | types, guide & examples, guide to experimental design | overview, steps, & examples, naturalistic observation | definition, guide & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

10 Observational Research Examples

Observational research involves observing the actions of people or animals, usually in their natural environments.

For example, Jane Goodall famously observed chimpanzees in the wild and reported on their group behaviors. Similarly, many educational researchers will conduct observations in classrooms to gain insights into how children learn.

Examples of Observational Research

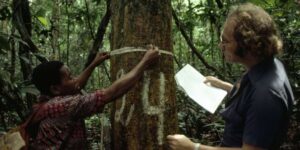

1. jane goodall’s research.

Jane Goodall is famous for her discovery that chimpanzees use tools. It is one of the most remarkable findings in psychology and anthropology .

Her primary method of study involved simply entering the natural habitat of her research subjects, sitting down with pencil and paper, and making detailed notes of what she observed.

Those observations were later organized and transformed into research papers that provided the world with amazing insights into animal behavior.

When she first discovered that chimpanzees use twigs to “fish” for termites, it was absolutely stunning. The renowned Louis Leakey proclaimed: “we must now redefine tool, redefine man, or accept chimps as humans.”

2. Linguistic Development of Children

Answering a question like, “how do children learn to speak,” can only be answered by observing young children at home.

By the time kids get to first grade, their language skills have already become well-developed, with a vocabulary of thousands of words and the ability to use relatively complex sentences.

Therefore, a researcher has to conduct their study in the child’s home environment. This typically involves having a trained data collector sit in a corner of a room and take detailed notes about what and how parents speak to their child.

Those observations are later classified in a way that they can be converted into quantifiable measures for statistical analysis.

For example, the data might be coded in terms of how many words the parents spoke, degree of sentence complexity, or emotional dynamic of being encouraging or critical. When the data is analyzed, it might reveal how patterns of parental comments are linked to the child’s level of linguistic development.

Related Article: 15 Action Research Examples

3. Consumer Product Design

Before Apple releases a new product to the market, they conduct extensive analyses of how the product will be perceived and used by consumers.

The company wants to know what kind of experience the consumer will have when using the product. Is the interface user-friendly and smooth? Does it fit comfortably in a person’s hand?

Is the overall experience pleasant?

So, the company will arrange for groups of prospective customers come to the lab and simply use the next iteration of one of their great products. That lab will absolutely contain a two-way mirror and a team of trained observers sitting behind it, taking detailed notes of what the test groups are doing. The groups might even be video recorded so their behavior can be observed again and again.

That will be followed by a focus group discussion , maybe a survey or two, and possibly some one-on-one interviews.

4. Satellite Images of Walmart

Observational research can even make some people millions of dollars. For example, a report by NPR describes how stock market analysts observe Walmart parking lots to predict the company’s earnings.

The analysts purchase satellite images of selected parking lots across the country, maybe even worldwide. That data is combined with what they know about customer purchasing habits, broken down by time of day and geographic region.

Over time, a detailed set of calculations are performed that allows the analysts to predict the company’s earnings with a remarkable degree of accuracy .

This kind of observational research can result in substantial profits.

5. Spying on Farms

Similar to the example above, observational research can also be implemented to study agriculture and farming.

By using infrared imaging software from satellites, some companies can observe crops across the globe. The images provide measures of chlorophyll absorption and moisture content, which can then be used to predict yields. Those images also allow analysts to simply count the number of acres being planted for specific crops across the globe.

In commodities such as wheat and corn, that prediction can lead to huge profits in the futures markets.

It’s an interesting application of observational research with serious monetary implications.

6. Decision-making Group Dynamics

When large corporations make big decisions, it can have serious consequences to the company’s profitability, or even survival.

Therefore, having a deep understanding of decision-making processes is essential. Although most of us think that we are quite rational in how we process information and formulate a solution, as it turns out, that’s not entirely true.

Decades of psychological research has focused on the function of statements that people make to each other during meetings. For example, there are task-masters, harmonizers, jokers, and others that are not involved at all.

A typical study involves having professional, trained observers watch a meeting transpire, either from a two-way mirror, by sitting-in on the meeting at the side, or observing through CCTV.

By tracking who says what to whom, and the type of statements being made, researchers can identify weaknesses and inefficiencies in how a particular group engages the decision-making process.

See More: Decision-Making Examples

7. Case Studies

A case study is an in-depth examination of one particular person. It is a form of observational research that involves the researcher spending a great deal of time with a single individual to gain a very detailed understanding of their behavior.

The researcher may take extensive notes, conduct interviews with the individual, or take video recordings of behavior for further study.

Case studies give a level of detailed information that is not available when studying large groups of people. That level of detail can often provide insights into a phenomenon that could lead to the development of a new theory or help a researcher identify new areas of research.

Researchers sometimes have no choice but to conduct a case study in situations in which the phenomenon under study is “rare and unusual” (Lee & Saunders, 2017). Because the condition is so uncommon, it is impossible to find a large enough sample of cases to study with quantitative methods.

Go Deeper: Pros and Cons of Case Study Research

8. Infant Attachment

One of the first studies on infant attachment utilized an observational research methodology . Mary Ainsworth went to Uganda in 1954 to study maternal practices and mother/infant bonding.

Ainsworth visited the homes of 26 families on a bi-monthly basis for 2 years, taking detailed notes and interviewing the mothers regarding their parenting practices.

Her notes were then turned into academic papers and formed the basis for the Strange Situations test that she developed for the laboratory setting.

The Strange Situations test consists of 8 situations, each one lasting no more than a few minutes. Trained observers are stationed behind a two-way mirror and have been trained to make systematic observations of the baby’s actions in each situation.

9. Ethnographic Research

Ethnography is a type of observational research where the researcher becomes part of a particular group or society.

The researcher’s role as data collector is hidden and they attempt to immerse themselves in the community as a regular member of the group.

By being a part of the group and keeping one’s purpose hidden, the researcher can observe the natural behavior of the members up-close. The group will behave as they would naturally and treat the researcher as if they were just another member. This can lead to insights into the group dynamics , beliefs, customs and rituals that could never be studied otherwise.

10. Time and Motion Studies

Time and motion studies involve observing work processes in the work environment. The goal is to make procedures more efficient, which can involve reducing the number of movements needed to complete a task.

Reducing the movements necessary to complete a task increases efficiency, and therefore improves productivity. A time and motion study can also identify safety issues that may cause harm to workers, and thereby help create a safer work environment.

The two most famous early pioneers of this type of observational research are Frank and Lillian Gilbreth.

Lilian was a psychologist that began to study the bricklayers of her husband Frank’s construction company. Together, they figured out a way to reduce the number of movements needed to lay bricks from 18 to 4 (see original video footage here ).

The couple became quite famous for their work during the industrial revolution and

Lillian became the only psychologist to appear on a postage stamp (in 1884).

Why do Observational Research?

Psychologists and anthropologists employ this methodology because:

- Psychologists find that studying people in a laboratory setting is very artificial. People often change their behavior if they know it is going to be analyzed by a psychologist later.

- Anthropologists often study unique cultures and indigenous peoples that have little contact with modern society. They often live in remote regions of the world, so, observing their behavior in a natural setting may be the only option.

- In animal studies , there are lots of interesting phenomenon that simply cannot be observed in a laboratory, such as foraging behavior or mate selection. Therefore, observational research is the best and only option available.

Read Also: Difference Between Observation and Inference

Observational research is an incredibly useful way to collect data on a phenomenon that simply can’t be observed in a lab setting. This can provide insights into human behavior that could never be revealed in an experiment (see: experimental vs observational research ).

Researchers employ observational research methodologies when they travel to remote regions of the world to study indigenous people, try to understand how parental interactions affect a child’s language development, or how animals survive in their natural habitats.

On the business side, observational research is used to understand how products are perceived by customers, how groups make important decisions that affect profits, or make economic predictions that can lead to huge monetary gains.

Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1967). Infancy in Uganda . Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A

psychological study of the Strange Situation. Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Crowe, S., Cresswell, K., Robertson, A., Huby, G., Avery, A., & Sheikh, A. (2011). The case study approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology , 11 , 100. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-100

d’Apice, K., Latham, R., & Stumm, S. (2019). A naturalistic home observational approach to children’s language, cognition, and behavior. Developmental Psychology, 55 (7),1414-1427. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000733

Lee, B., & Saunders, M. N. K. (2017). Conducting Case Study Research for Business and Management Students. SAGE Publications.

Dave Cornell (PhD)

Dr. Cornell has worked in education for more than 20 years. His work has involved designing teacher certification for Trinity College in London and in-service training for state governments in the United States. He has trained kindergarten teachers in 8 countries and helped businessmen and women open baby centers and kindergartens in 3 countries.

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 25 Positive Punishment Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 25 Dissociation Examples (Psychology)

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 15 Zone of Proximal Development Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ Perception Checking: 15 Examples and Definition

Chris Drew (PhD)

This article was peer-reviewed and edited by Chris Drew (PhD). The review process on Helpful Professor involves having a PhD level expert fact check, edit, and contribute to articles. Reviewers ensure all content reflects expert academic consensus and is backed up with reference to academic studies. Dr. Drew has published over 20 academic articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education and holds a PhD in Education from ACU.

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link 25 Positive Punishment Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link 25 Dissociation Examples (Psychology)

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link 15 Zone of Proximal Development Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link Perception Checking: 15 Examples and Definition

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Research Question Examples 🧑🏻🏫

25+ Practical Examples & Ideas To Help You Get Started

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | October 2023

A well-crafted research question (or set of questions) sets the stage for a robust study and meaningful insights. But, if you’re new to research, it’s not always clear what exactly constitutes a good research question. In this post, we’ll provide you with clear examples of quality research questions across various disciplines, so that you can approach your research project with confidence!

Research Question Examples

- Psychology research questions

- Business research questions

- Education research questions

- Healthcare research questions

- Computer science research questions

Examples: Psychology

Let’s start by looking at some examples of research questions that you might encounter within the discipline of psychology.

How does sleep quality affect academic performance in university students?

This question is specific to a population (university students) and looks at a direct relationship between sleep and academic performance, both of which are quantifiable and measurable variables.

What factors contribute to the onset of anxiety disorders in adolescents?

The question narrows down the age group and focuses on identifying multiple contributing factors. There are various ways in which it could be approached from a methodological standpoint, including both qualitatively and quantitatively.

Do mindfulness techniques improve emotional well-being?

This is a focused research question aiming to evaluate the effectiveness of a specific intervention.

How does early childhood trauma impact adult relationships?

This research question targets a clear cause-and-effect relationship over a long timescale, making it focused but comprehensive.

Is there a correlation between screen time and depression in teenagers?

This research question focuses on an in-demand current issue and a specific demographic, allowing for a focused investigation. The key variables are clearly stated within the question and can be measured and analysed (i.e., high feasibility).

Examples: Business/Management

Next, let’s look at some examples of well-articulated research questions within the business and management realm.

How do leadership styles impact employee retention?

This is an example of a strong research question because it directly looks at the effect of one variable (leadership styles) on another (employee retention), allowing from a strongly aligned methodological approach.

What role does corporate social responsibility play in consumer choice?

Current and precise, this research question can reveal how social concerns are influencing buying behaviour by way of a qualitative exploration.

Does remote work increase or decrease productivity in tech companies?

Focused on a particular industry and a hot topic, this research question could yield timely, actionable insights that would have high practical value in the real world.

How do economic downturns affect small businesses in the homebuilding industry?

Vital for policy-making, this highly specific research question aims to uncover the challenges faced by small businesses within a certain industry.

Which employee benefits have the greatest impact on job satisfaction?

By being straightforward and specific, answering this research question could provide tangible insights to employers.

Examples: Education

Next, let’s look at some potential research questions within the education, training and development domain.

How does class size affect students’ academic performance in primary schools?

This example research question targets two clearly defined variables, which can be measured and analysed relatively easily.

Do online courses result in better retention of material than traditional courses?

Timely, specific and focused, answering this research question can help inform educational policy and personal choices about learning formats.

What impact do US public school lunches have on student health?

Targeting a specific, well-defined context, the research could lead to direct changes in public health policies.

To what degree does parental involvement improve academic outcomes in secondary education in the Midwest?

This research question focuses on a specific context (secondary education in the Midwest) and has clearly defined constructs.

What are the negative effects of standardised tests on student learning within Oklahoma primary schools?

This research question has a clear focus (negative outcomes) and is narrowed into a very specific context.

Need a helping hand?

Examples: Healthcare

Shifting to a different field, let’s look at some examples of research questions within the healthcare space.

What are the most effective treatments for chronic back pain amongst UK senior males?

Specific and solution-oriented, this research question focuses on clear variables and a well-defined context (senior males within the UK).

How do different healthcare policies affect patient satisfaction in public hospitals in South Africa?

This question is has clearly defined variables and is narrowly focused in terms of context.

Which factors contribute to obesity rates in urban areas within California?

This question is focused yet broad, aiming to reveal several contributing factors for targeted interventions.

Does telemedicine provide the same perceived quality of care as in-person visits for diabetes patients?

Ideal for a qualitative study, this research question explores a single construct (perceived quality of care) within a well-defined sample (diabetes patients).

Which lifestyle factors have the greatest affect on the risk of heart disease?

This research question aims to uncover modifiable factors, offering preventive health recommendations.

Examples: Computer Science

Last but certainly not least, let’s look at a few examples of research questions within the computer science world.

What are the perceived risks of cloud-based storage systems?

Highly relevant in our digital age, this research question would align well with a qualitative interview approach to better understand what users feel the key risks of cloud storage are.

Which factors affect the energy efficiency of data centres in Ohio?

With a clear focus, this research question lays a firm foundation for a quantitative study.

How do TikTok algorithms impact user behaviour amongst new graduates?

While this research question is more open-ended, it could form the basis for a qualitative investigation.

What are the perceived risk and benefits of open-source software software within the web design industry?

Practical and straightforward, the results could guide both developers and end-users in their choices.

Remember, these are just examples…

In this post, we’ve tried to provide a wide range of research question examples to help you get a feel for what research questions look like in practice. That said, it’s important to remember that these are just examples and don’t necessarily equate to good research topics . If you’re still trying to find a topic, check out our topic megalist for inspiration.

Psst… there’s more (for free)

This post is part of our dissertation mini-course, which covers everything you need to get started with your dissertation, thesis or research project.

You Might Also Like:

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Observational Research: What is, Types, Pros & Cons + Example

Researchers can gather customer data in a variety of ways, including surveys, interviews, and research. But not all data can be collected by asking questions because customers might not be conscious of their behaviors.

It is when observational research comes in. This research is a way to learn about people by observing them in their natural environment. This kind of research helps researchers figure out how people act in different situations and what things in the environment affect their actions.

This blog will teach you about observational research, including types and observation methods. Let’s get started.

What is observational research?

Observational research is a broad term for various non-experimental studies in which behavior is carefully watched and recorded.

The goal of this research is to describe a variable or a set of variables. More broadly, the goal is to capture specific individual, group, or setting characteristics.

Since it is non-experimental and uncontrolled, we cannot draw causal research conclusions from it. The observational data collected in research studies is frequently qualitative observation , but it can also be quantitative or both (mixed methods).

Types of observational research

Conducting observational research can take many different forms. There are various types of this research. These types are classified below according to how much a researcher interferes with or controls the environment.

Naturalistic observation

Taking notes on what is seen is the simplest form of observational research. A researcher makes no interference in naturalistic observation. It’s just watching how people act in their natural environments.

Importantly, there is no attempt to modify factors in naturalistic observation, as there would be when comparing data between a control group and an experimental group.

Case studiesCase studies

A case study is a sort of observational research that focuses on a single phenomenon. It is a naturalistic observation because it captures data in the field. But case studies focus on a specific point of reference, like a person or event, while other studies may have a wider scope and try to record everything that happens in the researcher’s eyes.

For example, a case study of a single businessman might try to find out how that person deals with a certain disease’s ups and down or loss.

Participant observation

Participant observation is similar to naturalistic observation, except that the researcher is a part of the natural environment they are studying. In such research, the researcher is also interested in rituals or cultural practices that can only be evaluated by sharing experiences.

For example, anyone can learn the basic rules of table Tennis by going to a game or following a team. Participant observation, on the other hand, lets people take part directly to learn more about how the team works and how the players relate to each other.

It usually includes the researcher joining a group to watch behavior they couldn’t see from afar. Participant observation can gather much information, from the interactions with the people being observed to the researchers’ thoughts.

Controlled observation

A more systematic structured observation entails recording the behaviors of research participants in a remote place. Case-control studies are more like experiments than other types of research, but they still use observational research methods. When researchers want to find out what caused a certain event, they might use a case-control study.

Longitudinal observation

This observational research is one of the most difficult and time-consuming because it requires watching people or events for a long time. Researchers should consider longitudinal observations when their research involves variables that can only be seen over time.

After all, you can’t get a complete picture of things like learning to read or losing weight in a single observation. Longitudinal studies keep an eye on the same people or events over a long period of time and look for changes or patterns in behavior.

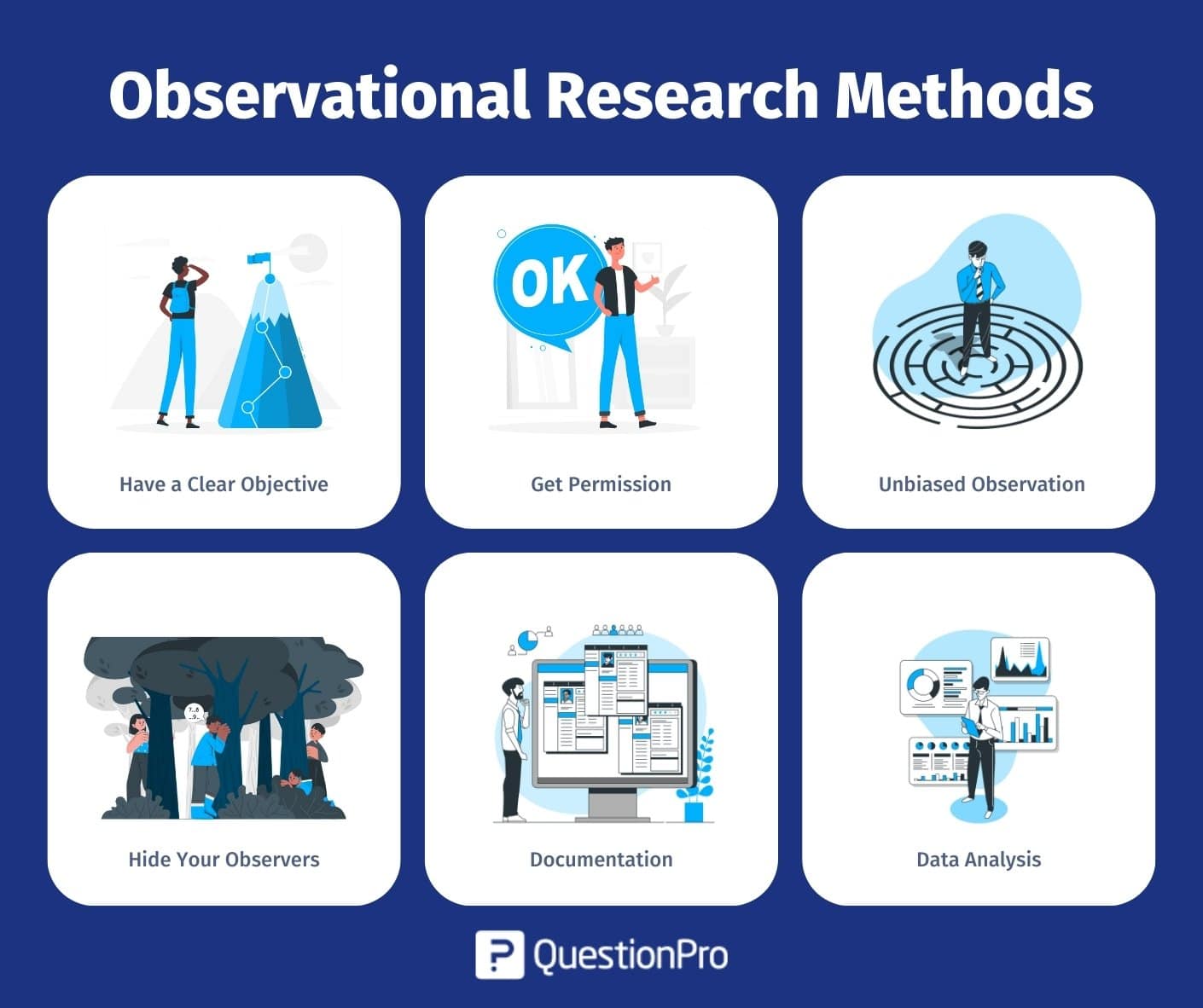

Observational research methods

When doing this research, there are a few observational methods to remember to ensure that the research is done correctly. Along with other research methods, let’s learn some key research methods of it:

Have a clear objective

For an observational study to be helpful, it needs to have a clear goal. It will help guide the observations and ensure they focus on the right things.

Get permission

Get permission from your participants. Getting explicit permission from the people you will be watching is essential. It means letting them know that they will be watched, the observation’s goal, and how their data will be used.

Unbiased observation

It is important to make sure the observations are fair and unbiased. It can be done by keeping detailed notes of what is seen and not putting any personal meaning on the data.

Hide your observers

In the observation method, keep your observers hidden. The participants should be unaware of the observers to avoid potential bias in their actions.

Documentation

It is important to document the observations clearly and straightforwardly. It will allow others to examine the information and confirm the observational research findings.

Data analysis

Data analysis is the last method. The researcher will analyze the collected data to draw conclusions or confirm a hypothesis.

Pros and cons of observational research

Observational studies are a great way to learn more about how your customers use different parts of your business. There are so many pros and cons of observational research. Let’s have a look at them.

- It provides a practical application for a hypothesis. In other words, it can help make research more complete.

- You can see people acting alone or in groups, such as customers. So, you can answer a number of questions about how people act as customers.

- There is a chance of researcher bias in observational research. Experts say that this can be a very big problem.

- Some human activities and behaviors can be difficult to understand. We are unable to see memories or attitudes. In other words, there are numerous situations in which observation alone is inadequate.

Example of observational research

The researcher observes customers buying products in a mall. Assuming the product is soap, the researcher will observe how long the customer takes to decide whether he likes the packaging or comes to the mall with his decision already made based on advertisements.

If the customer takes their time making a decision, the researcher will conclude that packaging and information on the package affect purchase behavior. If a customer makes a quick decision, the decision is likely predetermined.

As a result, the researcher will recommend more and better advertisements in this case. All of these findings were obtained through simple observational research.

How to conduct observational research with QuestionPro?

QuestionPro can help with observational research by providing tools to collect and analyze data. It can help in the following ways:

Define the research goals and question types you want to answer with your observational study . Use QuestionPro’s customizable survey templates and questions to do a survey that fits your research goals and gets the necessary information.

You can distribute the survey to your target audience using QuestionPro’s online platform or by sending a link to the survey.

With QuestionPro’s real-time data analysis and reporting features, you can collect and look at the data as people fill out the survey. Use the advanced analytics tools in QuestionPro to see and understand the data and find insights and trends.

If you need to, you can export the data from QuestionPro into the analysis tools you like to use. Draw conclusions from the collected and analyzed data and answer the research questions that were asked at the beginning of the research.

For a deeper understanding of human behaviors and decision-making processes, explore the realm of Behavioral Research .

To summarize, observational research is an effective strategy for collecting data and getting insights into real-world phenomena. When done right, this research can give helpful information and help people make decisions.

QuestionPro is a valuable tool that can help with observational research by letting you create online surveys, analyze data in real time, make surveys your own, keep your data safe, and use advanced analytics tools.

To do this research with QuestionPro, researchers need to define their research goals, do a survey that matches their goals, send the survey to participants, collect and analyze the data, visualize and explain the results, export data if needed, and draw conclusions from the data collected.

By keeping in mind what has been said above, researchers can use QuestionPro to help with their observational research and gain valuable data. Try out QuestionPro today!

FREE TRIAL LEARN MORE

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Observational research is a method in which researchers observe and systematically record behaviors, events, or phenomena without directly manipulating them.

There are three main types of observational research: naturalistic observation, participant observation, and structured observation.

Naturalistic observation involves observing subjects in their natural environment without any interference.

MORE LIKE THIS

Top 13 A/B Testing Software for Optimizing Your Website

Apr 12, 2024

21 Best Contact Center Experience Software in 2024

Government Customer Experience: Impact on Government Service

Apr 11, 2024

Employee Engagement App: Top 11 For Workforce Improvement

Apr 10, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Table of Contents

Observational Research

Definition:

Observational research is a type of research method where the researcher observes and records the behavior of individuals or groups in their natural environment. In other words, the researcher does not intervene or manipulate any variables but simply observes and describes what is happening.

Observation

Observation is the process of collecting and recording data by observing and noting events, behaviors, or phenomena in a systematic and objective manner. It is a fundamental method used in research, scientific inquiry, and everyday life to gain an understanding of the world around us.

Types of Observational Research

Observational research can be categorized into different types based on the level of control and the degree of involvement of the researcher in the study. Some of the common types of observational research are:

Naturalistic Observation

In naturalistic observation, the researcher observes and records the behavior of individuals or groups in their natural environment without any interference or manipulation of variables.

Controlled Observation

In controlled observation, the researcher controls the environment in which the observation is taking place. This type of observation is often used in laboratory settings.

Participant Observation

In participant observation, the researcher becomes an active participant in the group or situation being observed. The researcher may interact with the individuals being observed and gather data on their behavior, attitudes, and experiences.

Structured Observation

In structured observation, the researcher defines a set of behaviors or events to be observed and records their occurrence.

Unstructured Observation

In unstructured observation, the researcher observes and records any behaviors or events that occur without predetermined categories.

Cross-Sectional Observation

In cross-sectional observation, the researcher observes and records the behavior of different individuals or groups at a single point in time.

Longitudinal Observation

In longitudinal observation, the researcher observes and records the behavior of the same individuals or groups over an extended period of time.

Data Collection Methods

Observational research uses various data collection methods to gather information about the behaviors and experiences of individuals or groups being observed. Some common data collection methods used in observational research include:

Field Notes

This method involves recording detailed notes of the observed behavior, events, and interactions. These notes are usually written in real-time during the observation process.

Audio and Video Recordings

Audio and video recordings can be used to capture the observed behavior and interactions. These recordings can be later analyzed to extract relevant information.

Surveys and Questionnaires

Surveys and questionnaires can be used to gather additional information from the individuals or groups being observed. This method can be used to validate or supplement the observational data.

Time Sampling

This method involves taking a snapshot of the observed behavior at pre-determined time intervals. This method helps to identify the frequency and duration of the observed behavior.

Event Sampling

This method involves recording specific events or behaviors that are of interest to the researcher. This method helps to provide detailed information about specific behaviors or events.

Checklists and Rating Scales

Checklists and rating scales can be used to record the occurrence and frequency of specific behaviors or events. This method helps to simplify and standardize the data collection process.

Observational Data Analysis Methods

Observational Data Analysis Methods are:

Descriptive Statistics

This method involves using statistical techniques such as frequency distributions, means, and standard deviations to summarize the observed behaviors, events, or interactions.

Qualitative Analysis

Qualitative analysis involves identifying patterns and themes in the observed behaviors or interactions. This analysis can be done manually or with the help of software tools.

Content Analysis

Content analysis involves categorizing and counting the occurrences of specific behaviors or events. This analysis can be done manually or with the help of software tools.

Time-series Analysis

Time-series analysis involves analyzing the changes in behavior or interactions over time. This analysis can help identify trends and patterns in the observed data.

Inter-observer Reliability Analysis

Inter-observer reliability analysis involves comparing the observations made by multiple observers to ensure the consistency and reliability of the data.

Multivariate Analysis

Multivariate analysis involves analyzing multiple variables simultaneously to identify the relationships between the observed behaviors, events, or interactions.

Event Coding

This method involves coding observed behaviors or events into specific categories and then analyzing the frequency and duration of each category.

Cluster Analysis

Cluster analysis involves grouping similar behaviors or events into clusters based on their characteristics or patterns.

Latent Class Analysis

Latent class analysis involves identifying subgroups of individuals or groups based on their observed behaviors or interactions.

Social network Analysis

Social network analysis involves mapping the social relationships and interactions between individuals or groups based on their observed behaviors.

The choice of data analysis method depends on the research question, the type of data collected, and the available resources. Researchers should choose the appropriate method that best fits their research question and objectives. It is also important to ensure the validity and reliability of the data analysis by using appropriate statistical tests and measures.

Applications of Observational Research

Observational research is a versatile research method that can be used in a variety of fields to explore and understand human behavior, attitudes, and preferences. Here are some common applications of observational research:

- Psychology : Observational research is commonly used in psychology to study human behavior in natural settings. This can include observing children at play to understand their social development or observing people’s reactions to stress to better understand how stress affects behavior.

- Marketing : Observational research is used in marketing to understand consumer behavior and preferences. This can include observing shoppers in stores to understand how they make purchase decisions or observing how people interact with advertisements to determine their effectiveness.

- Education : Observational research is used in education to study teaching and learning in natural settings. This can include observing classrooms to understand how teachers interact with students or observing students to understand how they learn.

- Anthropology : Observational research is commonly used in anthropology to understand cultural practices and beliefs. This can include observing people’s daily routines to understand their culture or observing rituals and ceremonies to better understand their significance.

- Healthcare : Observational research is used in healthcare to understand patient behavior and preferences. This can include observing patients in hospitals to understand how they interact with healthcare professionals or observing patients with chronic illnesses to better understand their daily routines and needs.

- Sociology : Observational research is used in sociology to understand social interactions and relationships. This can include observing people in public spaces to understand how they interact with others or observing groups to understand how they function.

- Ecology : Observational research is used in ecology to understand the behavior and interactions of animals and plants in their natural habitats. This can include observing animal behavior to understand their social structures or observing plant growth to understand their response to environmental factors.

- Criminology : Observational research is used in criminology to understand criminal behavior and the factors that contribute to it. This can include observing criminal activity in a particular area to identify patterns or observing the behavior of inmates to understand their experience in the criminal justice system.

Observational Research Examples

Here are some real-time observational research examples:

- A researcher observes and records the behaviors of a group of children on a playground to study their social interactions and play patterns.

- A researcher observes the buying behaviors of customers in a retail store to study the impact of store layout and product placement on purchase decisions.

- A researcher observes the behavior of drivers at a busy intersection to study the effectiveness of traffic signs and signals.

- A researcher observes the behavior of patients in a hospital to study the impact of staff communication and interaction on patient satisfaction and recovery.

- A researcher observes the behavior of employees in a workplace to study the impact of the work environment on productivity and job satisfaction.

- A researcher observes the behavior of shoppers in a mall to study the impact of music and lighting on consumer behavior.

- A researcher observes the behavior of animals in their natural habitat to study their social and feeding behaviors.

- A researcher observes the behavior of students in a classroom to study the effectiveness of teaching methods and student engagement.

- A researcher observes the behavior of pedestrians and cyclists on a city street to study the impact of infrastructure and traffic regulations on safety.

How to Conduct Observational Research

Here are some general steps for conducting Observational Research:

- Define the Research Question: Determine the research question and objectives to guide the observational research study. The research question should be specific, clear, and relevant to the area of study.

- Choose the appropriate observational method: Choose the appropriate observational method based on the research question, the type of data required, and the available resources.

- Plan the observation: Plan the observation by selecting the observation location, duration, and sampling technique. Identify the population or sample to be observed and the characteristics to be recorded.

- Train observers: Train the observers on the observational method, data collection tools, and techniques. Ensure that the observers understand the research question and objectives and can accurately record the observed behaviors or events.

- Conduct the observation : Conduct the observation by recording the observed behaviors or events using the data collection tools and techniques. Ensure that the observation is conducted in a consistent and unbiased manner.

- Analyze the data: Analyze the observed data using appropriate data analysis methods such as descriptive statistics, qualitative analysis, or content analysis. Validate the data by checking the inter-observer reliability and conducting statistical tests.

- Interpret the results: Interpret the results by answering the research question and objectives. Identify the patterns, trends, or relationships in the observed data and draw conclusions based on the analysis.

- Report the findings: Report the findings in a clear and concise manner, using appropriate visual aids and tables. Discuss the implications of the results and the limitations of the study.

When to use Observational Research

Here are some situations where observational research can be useful:

- Exploratory Research: Observational research can be used in exploratory studies to gain insights into new phenomena or areas of interest.

- Hypothesis Generation: Observational research can be used to generate hypotheses about the relationships between variables, which can be tested using experimental research.

- Naturalistic Settings: Observational research is useful in naturalistic settings where it is difficult or unethical to manipulate the environment or variables.

- Human Behavior: Observational research is useful in studying human behavior, such as social interactions, decision-making, and communication patterns.

- Animal Behavior: Observational research is useful in studying animal behavior in their natural habitats, such as social and feeding behaviors.

- Longitudinal Studies: Observational research can be used in longitudinal studies to observe changes in behavior over time.

- Ethical Considerations: Observational research can be used in situations where manipulating the environment or variables would be unethical or impractical.

Purpose of Observational Research

Observational research is a method of collecting and analyzing data by observing individuals or phenomena in their natural settings, without manipulating them in any way. The purpose of observational research is to gain insights into human behavior, attitudes, and preferences, as well as to identify patterns, trends, and relationships that may exist between variables.

The primary purpose of observational research is to generate hypotheses that can be tested through more rigorous experimental methods. By observing behavior and identifying patterns, researchers can develop a better understanding of the factors that influence human behavior, and use this knowledge to design experiments that test specific hypotheses.

Observational research is also used to generate descriptive data about a population or phenomenon. For example, an observational study of shoppers in a grocery store might reveal that women are more likely than men to buy organic produce. This type of information can be useful for marketers or policy-makers who want to understand consumer preferences and behavior.

In addition, observational research can be used to monitor changes over time. By observing behavior at different points in time, researchers can identify trends and changes that may be indicative of broader social or cultural shifts.

Overall, the purpose of observational research is to provide insights into human behavior and to generate hypotheses that can be tested through further research.

Advantages of Observational Research

There are several advantages to using observational research in different fields, including:

- Naturalistic observation: Observational research allows researchers to observe behavior in a naturalistic setting, which means that people are observed in their natural environment without the constraints of a laboratory. This helps to ensure that the behavior observed is more representative of the real-world situation.

- Unobtrusive : Observational research is often unobtrusive, which means that the researcher does not interfere with the behavior being observed. This can reduce the likelihood of the research being affected by the observer’s presence or the Hawthorne effect, where people modify their behavior when they know they are being observed.

- Cost-effective : Observational research can be less expensive than other research methods, such as experiments or surveys. Researchers do not need to recruit participants or pay for expensive equipment, making it a more cost-effective research method.

- Flexibility: Observational research is a flexible research method that can be used in a variety of settings and for a range of research questions. Observational research can be used to generate hypotheses, to collect data on behavior, or to monitor changes over time.

- Rich data : Observational research provides rich data that can be analyzed to identify patterns and relationships between variables. It can also provide context for behaviors, helping to explain why people behave in a certain way.

- Validity : Observational research can provide high levels of validity, meaning that the results accurately reflect the behavior being studied. This is because the behavior is being observed in a natural setting without interference from the researcher.

Disadvantages of Observational Research

While observational research has many advantages, it also has some limitations and disadvantages. Here are some of the disadvantages of observational research:

- Observer bias: Observational research is prone to observer bias, which is when the observer’s own beliefs and assumptions affect the way they interpret and record behavior. This can lead to inaccurate or unreliable data.

- Limited generalizability: The behavior observed in a specific setting may not be representative of the behavior in other settings. This can limit the generalizability of the findings from observational research.

- Difficulty in establishing causality: Observational research is often correlational, which means that it identifies relationships between variables but does not establish causality. This can make it difficult to determine if a particular behavior is causing an outcome or if the relationship is due to other factors.

- Ethical concerns: Observational research can raise ethical concerns if the participants being observed are unaware that they are being observed or if the observations invade their privacy.

- Time-consuming: Observational research can be time-consuming, especially if the behavior being observed is infrequent or occurs over a long period of time. This can make it difficult to collect enough data to draw valid conclusions.

- Difficulty in measuring internal processes: Observational research may not be effective in measuring internal processes, such as thoughts, feelings, and attitudes. This can limit the ability to understand the reasons behind behavior.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Quantitative Research – Methods, Types and...

Qualitative Research Methods

Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

Survey Research – Types, Methods, Examples

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Non-Experimental Research

32 Observational Research

Learning objectives.

- List the various types of observational research methods and distinguish between each.

- Describe the strengths and weakness of each observational research method.

What Is Observational Research?

The term observational research is used to refer to several different types of non-experimental studies in which behavior is systematically observed and recorded. The goal of observational research is to describe a variable or set of variables. More generally, the goal is to obtain a snapshot of specific characteristics of an individual, group, or setting. As described previously, observational research is non-experimental because nothing is manipulated or controlled, and as such we cannot arrive at causal conclusions using this approach. The data that are collected in observational research studies are often qualitative in nature but they may also be quantitative or both (mixed-methods). There are several different types of observational methods that will be described below.

Naturalistic Observation

Naturalistic observation is an observational method that involves observing people’s behavior in the environment in which it typically occurs. Thus naturalistic observation is a type of field research (as opposed to a type of laboratory research). Jane Goodall’s famous research on chimpanzees is a classic example of naturalistic observation. Dr. Goodall spent three decades observing chimpanzees in their natural environment in East Africa. She examined such things as chimpanzee’s social structure, mating patterns, gender roles, family structure, and care of offspring by observing them in the wild. However, naturalistic observation could more simply involve observing shoppers in a grocery store, children on a school playground, or psychiatric inpatients in their wards. Researchers engaged in naturalistic observation usually make their observations as unobtrusively as possible so that participants are not aware that they are being studied. Such an approach is called disguised naturalistic observation . Ethically, this method is considered to be acceptable if the participants remain anonymous and the behavior occurs in a public setting where people would not normally have an expectation of privacy. Grocery shoppers putting items into their shopping carts, for example, are engaged in public behavior that is easily observable by store employees and other shoppers. For this reason, most researchers would consider it ethically acceptable to observe them for a study. On the other hand, one of the arguments against the ethicality of the naturalistic observation of “bathroom behavior” discussed earlier in the book is that people have a reasonable expectation of privacy even in a public restroom and that this expectation was violated.

In cases where it is not ethical or practical to conduct disguised naturalistic observation, researchers can conduct undisguised naturalistic observation where the participants are made aware of the researcher presence and monitoring of their behavior. However, one concern with undisguised naturalistic observation is reactivity. Reactivity refers to when a measure changes participants’ behavior. In the case of undisguised naturalistic observation, the concern with reactivity is that when people know they are being observed and studied, they may act differently than they normally would. This type of reactivity is known as the Hawthorne effect . For instance, you may act much differently in a bar if you know that someone is observing you and recording your behaviors and this would invalidate the study. So disguised observation is less reactive and therefore can have higher validity because people are not aware that their behaviors are being observed and recorded. However, we now know that people often become used to being observed and with time they begin to behave naturally in the researcher’s presence. In other words, over time people habituate to being observed. Think about reality shows like Big Brother or Survivor where people are constantly being observed and recorded. While they may be on their best behavior at first, in a fairly short amount of time they are flirting, having sex, wearing next to nothing, screaming at each other, and occasionally behaving in ways that are embarrassing.

Participant Observation

Another approach to data collection in observational research is participant observation. In participant observation , researchers become active participants in the group or situation they are studying. Participant observation is very similar to naturalistic observation in that it involves observing people’s behavior in the environment in which it typically occurs. As with naturalistic observation, the data that are collected can include interviews (usually unstructured), notes based on their observations and interactions, documents, photographs, and other artifacts. The only difference between naturalistic observation and participant observation is that researchers engaged in participant observation become active members of the group or situations they are studying. The basic rationale for participant observation is that there may be important information that is only accessible to, or can be interpreted only by, someone who is an active participant in the group or situation. Like naturalistic observation, participant observation can be either disguised or undisguised. In disguised participant observation , the researchers pretend to be members of the social group they are observing and conceal their true identity as researchers.

In a famous example of disguised participant observation, Leon Festinger and his colleagues infiltrated a doomsday cult known as the Seekers, whose members believed that the apocalypse would occur on December 21, 1954. Interested in studying how members of the group would cope psychologically when the prophecy inevitably failed, they carefully recorded the events and reactions of the cult members in the days before and after the supposed end of the world. Unsurprisingly, the cult members did not give up their belief but instead convinced themselves that it was their faith and efforts that saved the world from destruction. Festinger and his colleagues later published a book about this experience, which they used to illustrate the theory of cognitive dissonance (Festinger, Riecken, & Schachter, 1956) [1] .

In contrast with undisguised participant observation , the researchers become a part of the group they are studying and they disclose their true identity as researchers to the group under investigation. Once again there are important ethical issues to consider with disguised participant observation. First no informed consent can be obtained and second deception is being used. The researcher is deceiving the participants by intentionally withholding information about their motivations for being a part of the social group they are studying. But sometimes disguised participation is the only way to access a protective group (like a cult). Further, disguised participant observation is less prone to reactivity than undisguised participant observation.

Rosenhan’s study (1973) [2] of the experience of people in a psychiatric ward would be considered disguised participant observation because Rosenhan and his pseudopatients were admitted into psychiatric hospitals on the pretense of being patients so that they could observe the way that psychiatric patients are treated by staff. The staff and other patients were unaware of their true identities as researchers.

Another example of participant observation comes from a study by sociologist Amy Wilkins on a university-based religious organization that emphasized how happy its members were (Wilkins, 2008) [3] . Wilkins spent 12 months attending and participating in the group’s meetings and social events, and she interviewed several group members. In her study, Wilkins identified several ways in which the group “enforced” happiness—for example, by continually talking about happiness, discouraging the expression of negative emotions, and using happiness as a way to distinguish themselves from other groups.

One of the primary benefits of participant observation is that the researchers are in a much better position to understand the viewpoint and experiences of the people they are studying when they are a part of the social group. The primary limitation with this approach is that the mere presence of the observer could affect the behavior of the people being observed. While this is also a concern with naturalistic observation, additional concerns arise when researchers become active members of the social group they are studying because that they may change the social dynamics and/or influence the behavior of the people they are studying. Similarly, if the researcher acts as a participant observer there can be concerns with biases resulting from developing relationships with the participants. Concretely, the researcher may become less objective resulting in more experimenter bias.

Structured Observation

Another observational method is structured observation . Here the investigator makes careful observations of one or more specific behaviors in a particular setting that is more structured than the settings used in naturalistic or participant observation. Often the setting in which the observations are made is not the natural setting. Instead, the researcher may observe people in the laboratory environment. Alternatively, the researcher may observe people in a natural setting (like a classroom setting) that they have structured some way, for instance by introducing some specific task participants are to engage in or by introducing a specific social situation or manipulation.

Structured observation is very similar to naturalistic observation and participant observation in that in all three cases researchers are observing naturally occurring behavior; however, the emphasis in structured observation is on gathering quantitative rather than qualitative data. Researchers using this approach are interested in a limited set of behaviors. This allows them to quantify the behaviors they are observing. In other words, structured observation is less global than naturalistic or participant observation because the researcher engaged in structured observations is interested in a small number of specific behaviors. Therefore, rather than recording everything that happens, the researcher only focuses on very specific behaviors of interest.

Researchers Robert Levine and Ara Norenzayan used structured observation to study differences in the “pace of life” across countries (Levine & Norenzayan, 1999) [4] . One of their measures involved observing pedestrians in a large city to see how long it took them to walk 60 feet. They found that people in some countries walked reliably faster than people in other countries. For example, people in Canada and Sweden covered 60 feet in just under 13 seconds on average, while people in Brazil and Romania took close to 17 seconds. When structured observation takes place in the complex and even chaotic “real world,” the questions of when, where, and under what conditions the observations will be made, and who exactly will be observed are important to consider. Levine and Norenzayan described their sampling process as follows:

“Male and female walking speed over a distance of 60 feet was measured in at least two locations in main downtown areas in each city. Measurements were taken during main business hours on clear summer days. All locations were flat, unobstructed, had broad sidewalks, and were sufficiently uncrowded to allow pedestrians to move at potentially maximum speeds. To control for the effects of socializing, only pedestrians walking alone were used. Children, individuals with obvious physical handicaps, and window-shoppers were not timed. Thirty-five men and 35 women were timed in most cities.” (p. 186).

Precise specification of the sampling process in this way makes data collection manageable for the observers, and it also provides some control over important extraneous variables. For example, by making their observations on clear summer days in all countries, Levine and Norenzayan controlled for effects of the weather on people’s walking speeds. In Levine and Norenzayan’s study, measurement was relatively straightforward. They simply measured out a 60-foot distance along a city sidewalk and then used a stopwatch to time participants as they walked over that distance.

As another example, researchers Robert Kraut and Robert Johnston wanted to study bowlers’ reactions to their shots, both when they were facing the pins and then when they turned toward their companions (Kraut & Johnston, 1979) [5] . But what “reactions” should they observe? Based on previous research and their own pilot testing, Kraut and Johnston created a list of reactions that included “closed smile,” “open smile,” “laugh,” “neutral face,” “look down,” “look away,” and “face cover” (covering one’s face with one’s hands). The observers committed this list to memory and then practiced by coding the reactions of bowlers who had been videotaped. During the actual study, the observers spoke into an audio recorder, describing the reactions they observed. Among the most interesting results of this study was that bowlers rarely smiled while they still faced the pins. They were much more likely to smile after they turned toward their companions, suggesting that smiling is not purely an expression of happiness but also a form of social communication.