Writing an Exceptional Presentation Letter: Stand Out from the Competition

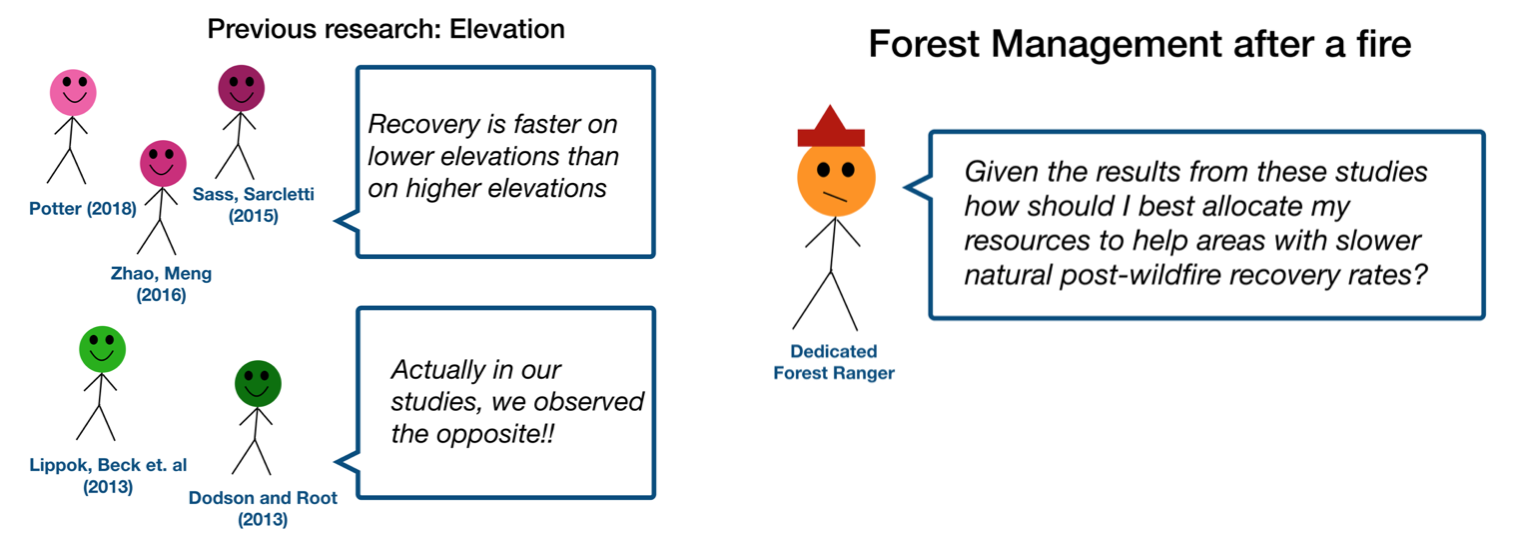

Have you ever experienced the pressure and anxiety that comes with writing a presentation letter? Crafting a compelling and effective presentation letter can be a challenging task. It's your first chance to make a good impression and stand out from the competition. In this article, we will explore the art of writing an exceptional presentation letter that will grab the attention of hiring managers and make them want to learn more about you.

Why is a Presentation Letter Important?

A presentation letter, also known as a cover letter, is a document that accompanies your resume when applying for a job. While your resume highlights your skills, experience, and qualifications, the presentation letter allows you to introduce yourself personally and express your interest in the position. It provides an opportunity to showcase your writing abilities and demonstrate your enthusiasm and fit for the role.

The Structure of a Presentation Letter

To ensure your presentation letter is well-structured, follow these essential sections:

Start your presentation letter with a professional header that includes your name, contact information, and the date. Make sure to address the letter to a specific person, if possible, rather than using a generic salutation.

2. Salutation

Begin your letter with a formal salutation, addressing the hiring manager or the person responsible for hiring. If you don't have a specific name, use a generic term such as "Dear Hiring Manager" or "Dear [Company Name] Team."

3. Introduction

In the first paragraph, introduce yourself and state the position you are applying for. Express your excitement about the opportunity and briefly mention how you learned about the job opening. This is your chance to grab the reader's attention and make them want to continue reading.

4. Body paragraphs

The body paragraphs should expand on your relevant skills, experiences, and achievements. You should tailor each paragraph to highlight why you are the perfect fit for the position. Use specific examples to demonstrate your capabilities and demonstrate how your qualifications align with the job requirements.

In the closing paragraph, summarize your key points and reiterate your interest in the position. Let the reader know that you are available for an interview and provide your contact information. Express gratitude for their time and consideration.

6. Signature

End your letter with a professional closing, such as "Sincerely" or "Best regards," followed by your full name typed out. Leave space for your handwritten signature if you are sending a printed letter.

Tips for Writing an Effective Presentation Letter

Now that you understand the structure of a presentation letter, let's explore some tips to help you craft a compelling and effective letter:

1. Personalize your letter

Avoid using generic templates and make an effort to tailor your letter to the specific company and position you are applying for. Research the company's values, goals, and culture, and highlight how your skills and experiences align with their needs.

2. Keep it concise and focused

Presentation letters shouldn't exceed one page, so keep your content concise and to the point. Avoid rambling or including irrelevant information. Focus on highlighting your most relevant qualifications and accomplishments.

3. Use a conversational tone

While your presentation letter should maintain a professional tone, it's essential to sound personable and approachable. Write in a conversational style, using personal pronouns and avoiding overly formal language. Engage the reader with active voice, short sentences, and rhetorical questions.

4. Showcase your achievements

Use specific examples to demonstrate your accomplishments and how you have contributed to previous roles or projects. Quantify your achievements whenever possible, using numbers and percentages to showcase your impact.

5. Proofread and edit

Ensure your letter is error-free by thoroughly proofreading it. Check for spelling and grammar mistakes, as well as formatting errors. Consider asking a friend or family member to review it as well, as a fresh pair of eyes may catch things you missed.

Writing an exceptional presentation letter is an essential step in the job application process. By following the structure and tips outlined in this article, you can create a compelling letter that grabs the attention of hiring managers and increases your chances of landing an interview. Remember to personalize your letter, keep it concise, and showcase your achievements. With a well-crafted presentation letter, you can make a strong first impression and stand out from the competition.

Get document management tips delivered to your inbox

Better, automated way to create documents. Use WordFields smart document templates.

- Chapter Seven: Presenting Your Results

This chapter serves as the culmination of the previous chapters, in that it focuses on how to present the results of one's study, regardless of the choice made among the three methods. Writing in academics has a form and style that you will want to apply not only to report your own research, but also to enhance your skills at reading original research published in academic journals. Beyond the basic academic style of report writing, there are specific, often unwritten assumptions about how quantitative, qualitative, and critical/rhetorical studies should be organized and the information they should contain. This chapter discusses how to present your results in writing, how to write accessibly, how to visualize data, and how to present your results in person.

- Chapter One: Introduction

- Chapter Two: Understanding the distinctions among research methods

- Chapter Three: Ethical research, writing, and creative work

- Chapter Four: Quantitative Methods (Part 1)

- Chapter Four: Quantitative Methods (Part 2 - Doing Your Study)

- Chapter Four: Quantitative Methods (Part 3 - Making Sense of Your Study)

- Chapter Five: Qualitative Methods (Part 1)

- Chapter Five: Qualitative Data (Part 2)

- Chapter Six: Critical / Rhetorical Methods (Part 1)

- Chapter Six: Critical / Rhetorical Methods (Part 2)

Written Presentation of Results

Once you've gone through the process of doing communication research – using a quantitative, qualitative, or critical/rhetorical methodological approach – the final step is to communicate it.

The major style manuals (the APA Manual, the MLA Handbook, and Turabian) are very helpful in documenting the structure of writing a study, and are highly recommended for consultation. But, no matter what style manual you may use, there are some common elements to the structure of an academic communication research paper.

Title Page :

This is simple: Your Paper's Title, Your Name, Your Institutional Affiliation (e.g., University), and the Date, each on separate lines, centered on the page. Try to make your title both descriptive (i.e., it gives the reader an idea what the study is about) and interesting (i.e., it is catchy enough to get one's attention).

For example, the title, "The uncritical idealization of a compensated psychopath character in a popular book series," would not be an inaccurate title for a published study, but it is rather vague and exceedingly boring. That study's author fortunately chose the title, "A boyfriend to die for: Edward Cullen as compensated psychopath in Stephanie Meyer's Twilight ," which is more precisely descriptive, and much more interesting (Merskin, 2011). The use of the colon in academic titles can help authors accomplish both objectives: a catchy but relevant phrase, followed by a more clear explanation of the article's topic.

In some instances, you might be asked to write an abstract, which is a summary of your paper that can range in length from 75 to 250 words. If it is a published paper, it is useful to include key search terms in this brief description of the paper (the title may already have a few of these terms as well). Although this may be the last thing your write, make it one of the best things you write, because this may be the first thing your audience reads about the paper (and may be the only thing read if it is written badly). Summarize the problem/research question, your methodological approach, your results and conclusions, and the significance of the paper in the abstract.

Quantitative and qualitative studies will most typically use the rest of the section titles noted below. Critical/rhetorical studies will include many of the same steps, but will often have different headings. For example, a critical/rhetorical paper will have an introduction, definition of terms, and literature review, followed by an analysis (often divided into sections by areas of investigation) and ending with a conclusion/implications section. Because critical/rhetorical research is much more descriptive, the subheadings in such a paper are often times not generic subheads like "literature review," but instead descriptive subheadings that apply to the topic at hand, as seen in the schematic below. Because many journals expect the article to follow typical research paper headings of introduction, literature review, methods, results, and discussion, we discuss these sections briefly next.

Introduction:

As you read social scientific journals (see chapter 1 for examples), you will find that they tend to get into the research question quickly and succinctly. Journal articles from the humanities tradition tend to be more descriptive in the introduction. But, in either case, it is good to begin with some kind of brief anecdote that gets the reader engaged in your work and lets the reader understand why this is an interesting topic. From that point, state your research question, define the problem (see Chapter One) with an overview of what we do and don't know, and finally state what you will do, or what you want to find out. The introduction thus builds the case for your topic, and is the beginning of building your argument, as we noted in chapter 1.

By the end of the Introduction, the reader should know what your topic is, why it is a significant communication topic, and why it is necessary that you investigate it (e.g., it could be there is gap in literature, you will conduct valuable exploratory research, or you will provide a new model for solving some professional or social problem).

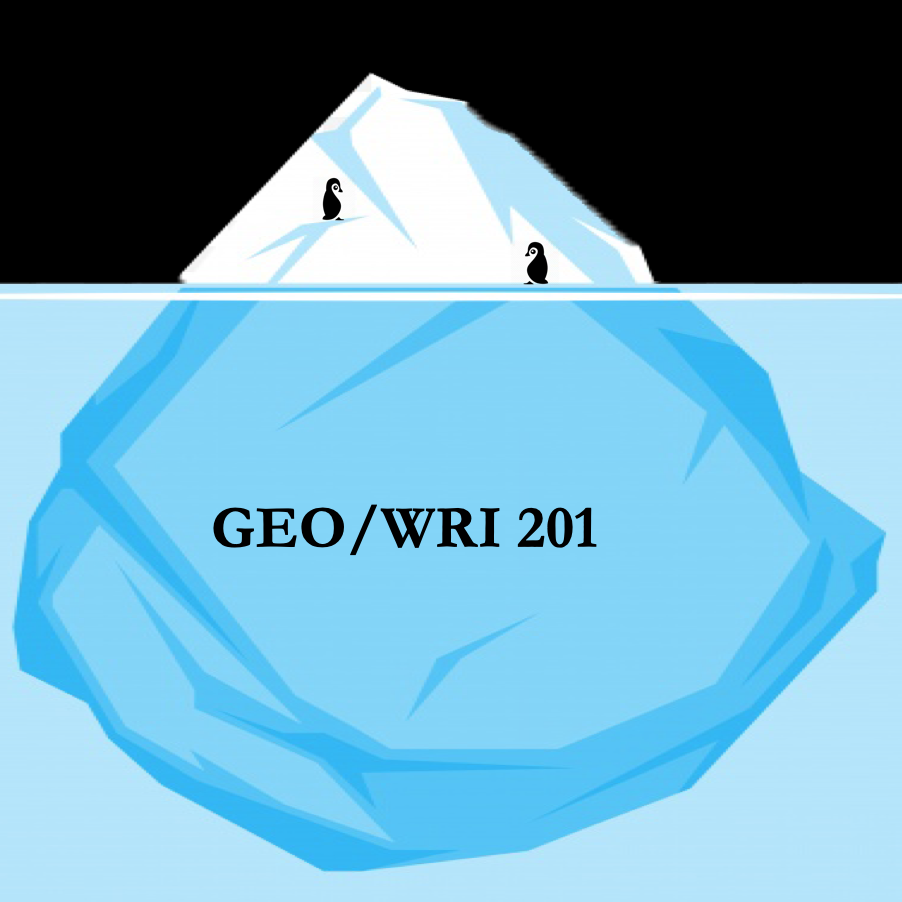

Literature Review:

The literature review summarizes and organizes the relevant books, articles, and other research in this area. It sets up both quantitative and qualitative studies, showing the need for the study. For critical/rhetorical research, the literature review often incorporates the description of the historical context and heuristic vocabulary, with key terms defined in this section of the paper. For more detail on writing a literature review, see Appendix 1.

The methods of your paper are the processes that govern your research, where the researcher explains what s/he did to solve the problem. As you have seen throughout this book, in communication studies, there are a number of different types of research methods. For example, in quantitative research, one might conduct surveys, experiments, or content analysis. In qualitative research, one might instead use interviews and observations. Critical/rhetorical studies methods are more about the interpretation of texts or the study of popular culture as communication. In creative communication research, the method may be an interpretive performance studies or filmmaking. Other methods used sometimes alone, or in combination with other methods, include legal research, historical research, and political economy research.

In quantitative and qualitative research papers, the methods will be most likely described according to the APA manual standards. At the very least, the methods will include a description of participants, data collection, and data analysis, with specific details on each of these elements. For example, in an experiment, the researcher will describe the number of participants, the materials used, the design of the experiment, the procedure of the experiment, and what statistics will be used to address the hypotheses/research questions.

Critical/rhetorical researchers rarely have a specific section called "methods," as opposed to quantitative and qualitative researchers, but rather demonstrate the method they use for analysis throughout the writing of their piece.

Helping your reader understand the methods you used for your study is important not only for your own study's credibility, but also for possible replication of your study by other researchers. A good guideline to keep in mind is transparency . You want to be as clear as possible in describing the decisions you made in designing your study, gathering and analyzing your data so that the reader can retrace your steps and understand how you came to the conclusions you formed. A research study can be very good, but if it is not clearly described so that others can see how the results were determined or obtained, then the quality of the study and its potential contributions are lost.

After you completed your study, your findings will be listed in the results section. Particularly in a quantitative study, the results section is for revisiting your hypotheses and reporting whether or not your results supported them, and the statistical significance of the results. Whether your study supported or contradicted your hypotheses, it's always helpful to fully report what your results were. The researcher usually organizes the results of his/her results section by research question or hypothesis, stating the results for each one, using statistics to show how the research question or hypothesis was answered in the study.

The qualitative results section also may be organized by research question, but usually is organized by themes which emerged from the data collected. The researcher provides rich details from her/his observations and interviews, with detailed quotations provided to illustrate the themes identified. Sometimes the results section is combined with the discussion section.

Critical/rhetorical researchers would include their analysis often with different subheadings in what would be considered a "results" section, yet not labeled specifically this way.

Discussion:

In the discussion section, the researcher gives an appraisal of the results. Here is where the researcher considers the results, particularly in light of the literature review, and explains what the findings mean. If the results confirmed or corresponded with the findings of other literature, then that should be stated. If the results didn't support the findings of previous studies, then the researcher should develop an explanation of why the study turned out this way. Sometimes, this section is called a "conclusion" by researchers.

References:

In this section, all of the literature cited in the text should have full references in alphabetical order. Appendices: Appendix material includes items like questionnaires used in the study, photographs, documents, etc. An alphabetical letter is assigned for each piece (e.g. Appendix A, Appendix B), with a second line of title describing what the appendix contains (e.g. Participant Informed Consent, or New York Times Speech Coverage). They should be organized consistently with the order in which they are referenced in the text of the paper. The page numbers for appendices are consecutive with the paper and reference list.

Tables/Figures:

Tables and figures are referenced in the text, but included at the end of the study and numbered consecutively. (Check with your professor; some like to have tables and figures inserted within the paper's main text.) Tables generally are data in a table format, whereas figures are diagrams (such as a pie chart) and drawings (such as a flow chart).

Accessible Writing

As you may have noticed, academic writing does have a language (e.g., words like heuristic vocabulary and hypotheses) and style (e.g., literature reviews) all its own. It is important to engage in that language and style, and understand how to use it to communicate effectively in an academic context . Yet, it is also important to remember that your analyses and findings should also be written to be accessible. Writers should avoid excessive jargon, or—even worse—deploying jargon to mask an incomplete understanding of a topic.

The scourge of excessive jargon in academic writing was the target of a famous hoax in 1996. A New York University physics professor submitted an article, " Transgressing the Boundaries: Toward a Transformative Hermeneutics of Quantum Gravity ," to a special issue of the academic journal Social Text devoted to science and postmodernism. The article was designed to point out how dense academic jargon can sometimes mask sloppy thinking. As the professor, Alan Sokal, had expected, the article was published. One sample sentence from the article reads:

It has thus become increasingly apparent that physical "reality", no less than social "reality", is at bottom a social and linguistic construct; that scientific "knowledge", far from being objective, reflects and encodes the dominant ideologies and power relations of the culture that produced it; that the truth claims of science are inherently theory-laden and self-referential; and consequently, that the discourse of the scientific community, for all its undeniable value, cannot assert a privileged epistemological status with respect to counter-hegemonic narratives emanating from dissident or marginalized communities. (Sokal, 1996. pp. 217-218)

According to the journal's editor, about six reviewers had read the article but didn't suspect that it was phony. A public debate ensued after Sokal revealed his hoax. Sokal said he worried that jargon and intellectual fads cause academics to lose contact with the real world and "undermine the prospect for progressive social critique" ( Scott, 1996 ). The APA Manual recommends to avoid using technical vocabulary where it is not needed or relevant or if the technical language is overused, thus becoming jargon. In short, the APA argues that "scientific jargon...grates on the reader, encumbers the communication of information, and wastes space" (American Psychological Association, 2010, p. 68).

Data Visualization

Images and words have long existed on the printed page of manuscripts, yet, until recently, relatively few researchers possessed the resources to effectively combine images combined with words (Tufte, 1990, 1983). Communication scholars are only now becoming aware of this dimension in research as computer technologies have made it possible for many people to produce and publish multimedia presentations.

Although visuals may seem to be anathema to the primacy of the written word in research, they are a legitimate way, and at times the best way, to present ideas. Visual scholar Lester Faigley et al. (2004) explains how data visualizations have become part of our daily lives:

Visualizations can shed light on research as well. London-based David McCandless specializes in visualizing interesting research questions, or in his words "the questions I wanted answering" (2009, p. 7). His images include a graph of the peak times of the year for breakups (based on Facebook status updates), a radiation dosage chart , and some experiments with the Google Ngram Viewer , which charts the appearance of keywords in millions of books over hundreds of years.

The public domain image below creatively maps U.S. Census data of the outflow of people from California to other states between 1995 and 2000.

Visualizing one's research is possible in multiple ways. A simple technology, for example, is to enter data into a spreadsheet such as Excel, and select Charts or SmartArt to generate graphics. A number of free web tools can also transform raw data into useful charts and graphs. Many Eyes , an open source data visualization tool (sponsored by IBM Research), says its goal "is to 'democratize' visualization and to enable a new social kind of data analysis" (IBM, 2011). Another tool, Soundslides , enables users to import images and audio to create a photographic slideshow, while the program handles all of the background code. Other tools, often open source and free, can help visual academic research into interactive maps; interactive, image-based timelines; interactive charts; and simple 2-D and 3-D animations. Adobe Creative Suite (which includes popular software like Photoshop) is available on most computers at universities, but open source alternatives exist as well. Gimp is comparable to Photoshop, and it is free and relatively easy to use.

One online performance studies journal, Liminalities , is an excellent example of how "research" can be more than just printed words. In each issue, traditional academic essays and book reviews are often supported photographs, while other parts of an issue can include video, audio, and multimedia contributions. The journal, founded in 2005, treats performance itself as a methodology, and accepts contribution in html, mp3, Quicktime, and Flash formats.

For communication researchers, there is also a vast array of visual digital archives available online. Many of these archives are located at colleges and universities around the world, where digital librarians are spearheading a massive effort to make information—print, audio, visual, and graphic—available to the public as part of a global information commons. For example, the University of Iowa has a considerable digital archive including historical photos documenting American railroads and a database of images related to geoscience. The University of Northern Iowa has a growing Special Collections Unit that includes digital images of every UNI Yearbook between 1905 and 1923 and audio files of UNI jazz band performances. Researchers at he University of Michigan developed OAIster , a rich database that has joined thousands of digital archives in one searchable interface. Indeed, virtually every academic library is now digitizing all types of media, not just texts, and making them available for public viewing and, when possible, for use in presenting research. In addition to academic collections, the Library of Congress and the National Archives offer an ever-expanding range of downloadable media; commercial, user-generated databases such as Flickr, Buzznet, YouTube and Google Video offer a rich resource of images that are often free of copyright constraints (see Chapter 3 about Creative Commons licenses) and nonprofit endeavors, such as the Internet Archive , contain a formidable collection of moving images, still photographs, audio files (including concert recordings), and open source software.

Presenting your Work in Person

As Communication students, it's expected that you are not only able to communicate your research project in written form but also in person.

Before you do any oral presentation, it's good to have a brief "pitch" ready for anyone who asks you about your research. The pitch is routine in Hollywood: a screenwriter has just a few minutes to present an idea to a producer. Although your pitch will be more sophisticated than, say, " Snakes on a Plane " (which unfortunately was made into a movie), you should in just a few lines be able to explain the gist of your research to anyone who asks. Developing this concise description, you will have some practice in distilling what might be a complicated topic into one others can quickly grasp.

Oral presentation

In most oral presentations of research, whether at the end of a semester, or at a research symposium or conference, you will likely have just 10 to 20 minutes. This is probably not enough time to read the entire paper aloud, which is not what you should do anyway if you want people to really listen (although, unfortunately some make this mistake). Instead, the point of the presentation should be to present your research in an interesting manner so the listeners will want to read the whole thing. In the presentation, spend the least amount of time on the literature review (a very brief summary will suffice) and the most on your own original contribution. In fact, you may tell your audience that you are only presenting on one portion of the paper, and that you would be happy to talk more about your research and findings in the question and answer session that typically follows. Consider your presentation the beginning of a dialogue between you and the audience. Your tone shouldn't be "I have found everything important there is to find, and I will cram as much as I can into this presentation," but instead "I found some things you will find interesting, but I realize there is more to find."

Turabian (2007) has a helpful chapter on presenting research. Most important, she emphasizes, is to remember that your audience members are listeners, not readers. Thus, recall the lessons on speech making in your college oral communication class. Give an introduction, tell them what the problem is, and map out what you will present to them. Organize your findings into a few points, and don't get bogged down in minutiae. (The minutiae are for readers to find if they wish, not for listeners to struggle through.) PowerPoint slides are acceptable, but don't read them. Instead, create an outline of a few main points, and practice your presentation.

Turabian suggests an introduction of not more than three minutes, which should include these elements:

- The research topic you will address (not more than a minute).

- Your research question (30 seconds or less)

- An answer to "so what?" – explaining the relevance of your research (30 seconds)

- Your claim, or argument (30 seconds or less)

- The map of your presentation structure (30 seconds or less)

As Turabian (2007) suggests, "Rehearse your introduction, not only to get it right, but to be able to look your audience in the eye as you give it. You can look down at notes later" (p. 125).

Poster presentation

In some symposiums and conferences, you may be asked to present at a "poster" session. Instead of presenting on a panel of 4-5 people to an audience, a poster presenter is with others in a large hall or room, and talks one-on-one with visitors who look at the visual poster display of the research. As in an oral presentation, a poster highlights just the main point of the paper. Then, if visitors have questions, the author can informally discuss her/his findings.

To attract attention, poster presentations need to be nicely designed, or in the words of an advertising professor who schedules poster sessions at conferences, "be big, bold, and brief" ( Broyles , 2011). Large type (at least 18 pt.), graphics, tables, and photos are recommended.

A poster presentation session at a conference, by David Eppstein (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 ( www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0 )], via Wikimedia Commons]

The Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (AEJMC) has a template for making an effective poster presentation . Many universities, copy shops, and Internet services also have large-scale printers, to print full-color research poster designs that can be rolled up and transported in a tube.

Judging Others' Research

After taking this course, you should have a basic knowledge of research methods. There will still be some things that may mystify you as a reader of other's research. For example, you may not be able to interpret the coefficients for statistical significance, or make sense of a complex structural equation. Some specialized vocabulary may still be difficult.

But, you should understand how to critically review research. For example, imagine you have been asked to do a blind (i.e., the author's identity is concealed) "peer review" of communication research for acceptance to a conference, or publication in an academic journal. For most conferences and journals , submissions are made online, where editors can manage the flow and assign reviews to papers. The evaluations reviewers make are based on the same things that we have covered in this book. For example, the conference for the AEJMC ask reviewers to consider (on a five-point scale, from Excellent to Poor) a number of familiar research dimensions, including the paper's clarity of purpose, literature review, clarity of research method, appropriateness of research method, evidence presented clearly, evidence supportive of conclusions, general writing and organization, and the significance of the contribution to the field.

Beyond academia, it is likely you will more frequently apply the lessons of research methods as a critical consumer of news, politics, and everyday life. Just because some expert cites a number or presents a conclusion doesn't mean it's automatically true. John Allen Paulos, in his book A Mathematician reads the newspaper , suggests some basic questions we can ask. "If statistics were presented, how were they obtained? How confident can we be of them? Were they derived from a random sample or from a collection of anecdotes? Does the correlation suggest a causal relationship, or is it merely a coincidence?" (1997, p. 201).

Through the study of research methods, we have begun to build a critical vocabulary and understanding to ask good questions when others present "knowledge." For example, if Candidate X won a straw poll in Iowa, does that mean she'll get her party's nomination? If Candidate Y wins an open primary in New Hampshire, does that mean he'll be the next president? If Candidate Z sheds a tear, does it matter what the context is, or whether that candidate is a man or a woman? What we learn in research methods about validity, reliability, sampling, variables, research participants, epistemology, grounded theory, and rhetoric, we can consider whether the "knowledge" that is presented in the news is a verifiable fact, a sound argument, or just conjecture.

American Psychological Association (2010). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (6th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Broyles, S. (2011). "About poster sessions." AEJMC. http://www.aejmc.org/home/2013/01/about-poster-sessions/ .

Faigley, L., George, D., Palchik, A., Selfe, C. (2004). Picturing texts . New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

IBM (2011). Overview of Many Eyes. http://www.research.ibm.com/social/projects_manyeyes.shtml .

McCandless, D. (2009). The visual miscellaneum . New York: Collins Design.

Merskin, D. (2011). A boyfriend to die for: Edward Cullen as compensated psychopath in Stephanie Meyer's Twilight. Journal of Communication Inquiry 35: 157-178. doi:10.1177/0196859911402992

Paulos, J. A. (1997). A mathematician reads the newspaper . New York: Anchor.

Scott, J. (1996, May 18). Postmodern gravity deconstructed, slyly. New York Times , http://www.nytimes.com/books/98/11/15/specials/sokal-text.html .

Sokal, A. (1996). Transgressing the boundaries: towards a transformative hermeneutics of quantum gravity. Social Text 46/47, 217-252.

Tufte, E. R. (1990). Envisioning information . Cheshire, CT: Graphics Press.

Tufte, E. R. (1983). The visual display of quantitative information . Cheshire, CT: Graphics Press.

Turabian, Kate L. (2007). A manual for writers of research papers, theses, and dissertations: Chicago style guide for students and researchers (7th ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Princeton Correspondents on Undergraduate Research

How to Make a Successful Research Presentation

Turning a research paper into a visual presentation is difficult; there are pitfalls, and navigating the path to a brief, informative presentation takes time and practice. As a TA for GEO/WRI 201: Methods in Data Analysis & Scientific Writing this past fall, I saw how this process works from an instructor’s standpoint. I’ve presented my own research before, but helping others present theirs taught me a bit more about the process. Here are some tips I learned that may help you with your next research presentation:

More is more

In general, your presentation will always benefit from more practice, more feedback, and more revision. By practicing in front of friends, you can get comfortable with presenting your work while receiving feedback. It is hard to know how to revise your presentation if you never practice. If you are presenting to a general audience, getting feedback from someone outside of your discipline is crucial. Terms and ideas that seem intuitive to you may be completely foreign to someone else, and your well-crafted presentation could fall flat.

Less is more

Limit the scope of your presentation, the number of slides, and the text on each slide. In my experience, text works well for organizing slides, orienting the audience to key terms, and annotating important figures–not for explaining complex ideas. Having fewer slides is usually better as well. In general, about one slide per minute of presentation is an appropriate budget. Too many slides is usually a sign that your topic is too broad.

Limit the scope of your presentation

Don’t present your paper. Presentations are usually around 10 min long. You will not have time to explain all of the research you did in a semester (or a year!) in such a short span of time. Instead, focus on the highlight(s). Identify a single compelling research question which your work addressed, and craft a succinct but complete narrative around it.

You will not have time to explain all of the research you did. Instead, focus on the highlights. Identify a single compelling research question which your work addressed, and craft a succinct but complete narrative around it.

Craft a compelling research narrative

After identifying the focused research question, walk your audience through your research as if it were a story. Presentations with strong narrative arcs are clear, captivating, and compelling.

- Introduction (exposition — rising action)

Orient the audience and draw them in by demonstrating the relevance and importance of your research story with strong global motive. Provide them with the necessary vocabulary and background knowledge to understand the plot of your story. Introduce the key studies (characters) relevant in your story and build tension and conflict with scholarly and data motive. By the end of your introduction, your audience should clearly understand your research question and be dying to know how you resolve the tension built through motive.

- Methods (rising action)

The methods section should transition smoothly and logically from the introduction. Beware of presenting your methods in a boring, arc-killing, ‘this is what I did.’ Focus on the details that set your story apart from the stories other people have already told. Keep the audience interested by clearly motivating your decisions based on your original research question or the tension built in your introduction.

- Results (climax)

Less is usually more here. Only present results which are clearly related to the focused research question you are presenting. Make sure you explain the results clearly so that your audience understands what your research found. This is the peak of tension in your narrative arc, so don’t undercut it by quickly clicking through to your discussion.

- Discussion (falling action)

By now your audience should be dying for a satisfying resolution. Here is where you contextualize your results and begin resolving the tension between past research. Be thorough. If you have too many conflicts left unresolved, or you don’t have enough time to present all of the resolutions, you probably need to further narrow the scope of your presentation.

- Conclusion (denouement)

Return back to your initial research question and motive, resolving any final conflicts and tying up loose ends. Leave the audience with a clear resolution of your focus research question, and use unresolved tension to set up potential sequels (i.e. further research).

Use your medium to enhance the narrative

Visual presentations should be dominated by clear, intentional graphics. Subtle animation in key moments (usually during the results or discussion) can add drama to the narrative arc and make conflict resolutions more satisfying. You are narrating a story written in images, videos, cartoons, and graphs. While your paper is mostly text, with graphics to highlight crucial points, your slides should be the opposite. Adapting to the new medium may require you to create or acquire far more graphics than you included in your paper, but it is necessary to create an engaging presentation.

The most important thing you can do for your presentation is to practice and revise. Bother your friends, your roommates, TAs–anybody who will sit down and listen to your work. Beyond that, think about presentations you have found compelling and try to incorporate some of those elements into your own. Remember you want your work to be comprehensible; you aren’t creating experts in 10 minutes. Above all, try to stay passionate about what you did and why. You put the time in, so show your audience that it’s worth it.

For more insight into research presentations, check out these past PCUR posts written by Emma and Ellie .

— Alec Getraer, Natural Sciences Correspondent

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

Welcome to the new OASIS website! We have academic skills, library skills, math and statistics support, and writing resources all together in one new home.

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Writing for Publication: Conference Proposals & Presentations

Presenting at conferences is an efficient and exciting forum in which you can share your research and findings. However, presenting your work to others at a conference requires determining what type of presentation would best suit your material as well as choosing an appropriate conference. Once you have made those decisions, you will be ready to write your conference proposal.

Types of Presentations

The types of professional conferences vary, from large international gatherings to small, regional meetings. The content can also be very research driven or be focused more specifically on the needs of practitioners. Hence, different conferences tend to have different formats, but the following are some of the most common:

Poster sessions are most frequently found in the sciences, but they are often offered as an option at conferences in other disciplines as well. A poster session is a visual representation of your work. In this format, you can highlight areas of your research and display them both textually and visually. At most conferences, poster sessions take place in a large room. Typically, researchers stand next to their display and answer informal questions about their research. See the American Public Health Association's Poster Session Guidelines for an example of the requirements for posters, keeping in mind that each professional organization and conference will have its own guidelines.

Panel discussions or presentations are formal conversations organized around a specific subject. At most conferences, several speakers take turns speaking for a predetermined amount of time about their research and findings on a given subject. Panel discussions are almost always followed by a question and answer session from the audience. At most conferences, choosing to present at a panel discussion is often more competitive than being selected for a poster session.

A paper with respondent session involves a presenter orally sharing his or her data and conclusions for an allotted period of time. Following that presentation, another researcher, often one with differing views on the same subject, gives a brief response to the paper. The initial presenter then responds to the respondent's response.

In a conference presentation, sometimes presenters just give a report of their research, especially if it has some implications to practice.

Writing the Proposal

Like an abstract, a successful conference proposal will clearly and succinctly introduce, summarize, and make conclusions about your topic and findings. Though every conference is, of course, different, objectives and conclusions are found in all conference proposals. However, be sure to follow a conference's submission guidelines, which will be listed on the conference website. Every conference has a committee that evaluates the relevance and merit of each proposal. The following are some important factors to take into consideration when crafting yours:

Length: Many conference proposals are no more than 400 words. Thus, brevity and clarity are extremely important.

Relevance: Choosing an appropriate conference is the first step toward acceptance of your work. The conference committee will want to know how your work relates to the topic of the conference and to your field as a whole. Be sure that your proposal discusses the uniqueness of your findings, along with their significance. Do not just summarize your research, but rather, place your research in a larger context. What are the implications of your findings? How might another researcher use your data?

Quotations : Avoid including in too many quotations in your conference proposal. If you do choose to include quotations, it is generally recommended that you state the author's name, though you do not need to include a full citation (Purdue Online Writing Lab, 2012).

Focus: Most experts recommend that a conference proposal have a thesis statement early on in the proposal. Do not keep the reader guessing about your conclusions. Rather, begin with your concise and arguable thesis and then discuss your main points. Remember, there is no need to prove your thesis in this shortened format, only to articulate your thesis and the central arguments you will use to back up your claims should you be invited to present your work.

Tone: Make sure to keep your audience in mind and to structure your proposal accordingly. Avoid overly specialized jargon that would only be familiar to participants in a subfield. Make sure your prose is clear, logical, and straightforward. Though your proposal should maintain an academic tone, your enthusiasm for your project should shine through, though not at the cost of formality.

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Choosing an Audience

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Cost of Attendance

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

- Utility Menu

de5f0c5840276572324fc6e2ece1a882

- How to Use This Site

- Core Competencies

- Create and Assess Your Slides

strategies, techniques, and tools for strong slide design, and maximum presentation quality.

Prior to delivering a talk, it is important to prepare and set yourself up for success with a strong slide deck. Depending on the nature of your presentation, the type of speaking engagement, your institution, and other factors and considerations, there are different kinds of approaches and priorities when it comes to slide design. This section includes some tips that will assist you with designing your slides to prepare for your presentation.

Slides drive home the main ideas of your research and play an important role to deliver a strong presentation. After reviewing the Fundamentals of Slide Design , use these resources to create and assess your slides to ensure that you have considered and included important components that make for an effective presentation.

Qualities of Strong Slide Design

Use this self-assessment checklist to design and review your slides. Check all boxes that incorporate key qualities of strong slide design. In addition to focusing on the style, typography, and layout, consider thinking about your use of visuals and color along with other elements to enhance the design of your slides.

Checklist for

Assertion-evidence slides.

The assertion-evidence slide structure is one effective technique to designing effective slides. In conjunction with the webinar on “Better Than Bullets: Transforming Slide Design” by Melissa Marshall, this checklist was developed as a resource for assertion-evidence slides but can be applied more generally to other types of slide designs. Consider the style, typography, and layout of your slides and what it might look like to incorporate these elements with an assertion-evidence slide structure in mind.

Research Presentation Rubric

The format of research presentations can vary across and within disciplines. Use this rubric to identify and assess elements of research presentations, including delivery strategies and slide design. This resource focuses on research presentations but may be useful beyond.

Templates and Examples for

Check out tips, templates, layout suggestions, and other examples of assertion-evidence slides on Rethinking Presentations in Science and Engineering by Michael Alley, MS, MFA, from Pennsylvania State University. Download the Assertion Evidence Presention template for Microsoft PowerPoint.

Additional Resources

Create and deliver standout technical presentations, present your science.

Melissa Marshall’s website explores how speakers can transform the way they present their research.

"The Craft of Scientific Presentations: Critical Steps to Succeed and Critical Errors to Avoid" book by Michael Alley

By distinguishing what makes a presenter successful, this book aims to improve your presentation skills.

Want to learn more about how to strengthen your presentation skills?

Visit the delivery authentically page for more information.

- Data Visualization

- Fundamentals of Slide Design

- Visual Design Tools

How to Prepare and Give a Scholarly Oral Presentation

- First Online: 01 January 2020

Cite this chapter

- Cheryl Gore-Felton 2

1479 Accesses

Building an academic reputation is one of the most important functions of an academic faculty member, and one of the best ways to build a reputation is by giving scholarly presentations, particularly those that are oral presentations. Earning the reputation of someone who can give an excellent talk often results in invitations to give keynote addresses at regional and national conferences, which increases a faculty member’s visibility along with their area of research. Given the importance of oral presentations, it is surprising that few graduate or medical programs provide courses on how to give a talk. This is unfortunate because there are skills that can be learned and strategies that can be used to improve the ability to give an interesting, well-received oral presentation. To that end, the aim of this chapter is to provide faculty with best practices and tips on preparing and giving an academic oral presentation.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Strategies for the Preparation and Delivery of Oral Presentation

Graduate Students and Learning How to Get Published

Pashler H, McDaniel M, Rohrer D, Bjork R. Learning styles: concepts and evidence. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2009;9:105–19.

Article Google Scholar

Newsam JM. Out in front: making your mark with a scientific presentation. USA: First Printing; 2019.

Google Scholar

Ericsson AK, Krampe RT, Tesch-Romer C. The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychol Rev. 1993;100:363–406.

Seaward BL. Managing stress: principles and strategies for health and well-being. 7th ed. Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC: Burlington; 2012.

Krantz WB. Presenting an effective and dynamic technical paper: a guidebook for novice and experienced speakers in a multicultural world. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2017.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA

Cheryl Gore-Felton

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Cheryl Gore-Felton .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Laura Weiss Roberts

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Gore-Felton, C. (2020). How to Prepare and Give a Scholarly Oral Presentation. In: Roberts, L. (eds) Roberts Academic Medicine Handbook. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-31957-1_42

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-31957-1_42

Published : 01 January 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-31956-4

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-31957-1

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

To ensure your presentation letter is well-structured, follow these essential sections: 1. Header. Start your presentation letter with a professional header that includes your name, contact information, and the date. Make sure to address the letter to a specific person, if possible, rather than using a generic salutation. 2.

Written Presentation of Results. Once you've gone through the process of doing communication research - using a quantitative, qualitative, or critical/rhetorical methodological approach - the final step is to communicate it.. The major style manuals (the APA Manual, the MLA Handbook, and Turabian) are very helpful in documenting the structure of writing a study, and are highly recommended ...

REHEARSING YOUR PRESENTATION. Practice with a friend. Practice the technology of using Zoom/Teams. Record yourself and analzye. Time yourself - presentation should be about 20 minutes. Limit fillers like "um". DO NOT READ YOUR SLIDES!!!!!

Taking this perspective can make presenting your research much less stressful because the focus of the task is no longer to engage an uninterested audience: It is to keep an already interested audience engaged. Here are some suggestions for constructing a presentation using various multimedia tools, such as PowerPoint, Keynote and Prezi.

Instead, focus on the highlights. Identify a single compelling research question which your work addressed, and craft a succinct but complete narrative around it. Craft a compelling research narrative. After identifying the focused research question, walk your audience through your research as if it were a story.

HOW TO GIVE A GOOD RESEARCH PRESENTATION . Prof. Daniel T. Gilbert, Department of Psychology, Harvard University (with a couple of tiny edits by Steve Lindsay) 1. HAVE A PLAN ... use a simple one with BIG letters. Also, give the audience a moment to read all of the words on a slide before you start talking again; otherwise they may miss what ...

Writing a Research Report: Presentation. Tables, Diagrams, Photos, and Maps. - Use when relevant and refer to them in the text. - Redraw diagrams rather than copying them directly. - Place at appropriate points in the text. - Select the most appropriate device. - List in contents at beginning of the report.

Following that presentation, another researcher, often one with differing views on the same subject, gives a brief response to the paper. The initial presenter then responds to the respondent's response. In a conference presentation, sometimes presenters just give a report of their research, especially if it has some implications to practice.

Slides drive home the main ideas of your research and play an important role to deliver a strong presentation. After reviewing the Fundamentals of Slide Design, use these resources to create and assess your slides to ensure that you have considered and included important components that make for an effective presentation.

To assist the audience, a speaker could start by saying, "Today, I am going to cover three main points.". Then, state what each point is by using transitional words such as "First," "Second," and "Finally.". For research focused presentations, the structure following the overview is similar to an academic paper.