Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Factors that influence uptake of routine postnatal care: Findings on women’s perspectives from a qualitative evidence synthesis

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Department of International Health, Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland, United States of America

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation School of Community Health and Midwifery, University of Central Lancashire, Preston, United Kingdom

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Reproductive Health and Research, World Health Organization, Genève, Switzerland

Roles Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Centre Hospitalier de l’Universite de Montreal, Montreal, Canada

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Partnership for Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health, World Health Organization, Genève, Switzerland

Affiliation Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts, United States of America

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing

- Emma Sacks,

- Kenneth Finlayson,

- Vanessa Brizuela,

- Nicola Crossland,

- Daniela Ziegler,

- Caroline Sauvé,

- Étienne V. Langlois,

- Dena Javadi,

- Soo Downe,

- Mercedes Bonet

- Published: August 12, 2022

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270264

- Reader Comments

Effective postnatal care is important for optimal care of women and newborns–to promote health and wellbeing, identify and treat clinical and psychosocial concerns, and to provide support for families. Yet uptake of formal postnatal care services is low and inequitable in many countries. As part of a larger study examining the views of women, partners, and families requiring both routine and specialised care, we analysed a subset of data on the views and experiences of women related to routine postnatal care.

We undertook a qualitative evidence synthesis, using a framework analysis approach. We included studies published up to December 2019 with extractable qualitative data, with no language restriction. We focused on women in the general population and their accounts of routine postnatal care utilization. We searched MEDLINE, PUBMED, CINAHL, EMBASE, EBM-Reviews, and grey literature. Two reviewers screened each study independently; inclusion was agreed by consensus. Data abstraction and scientific quality assessment were carried out using a study-specific extraction form and established quality assessment tools. The analysis framework was developed a priori based on previous knowledge and research on the topic and adapted. Due to the number of included texts, the final synthesis was developed inductively from the initial framework by iterative sampling of the included studies, until data saturation was achieved. Findings are presented by high versus low/middle income country, and by confidence in the finding, applying the GRADE-CERQual approach.

Of 12,678 papers, 512 met the inclusion criteria; 59 articles were sampled for analysis. Five themes were identified: access and availability; physical and human resources; external influences; social norms; and experience of care. High confidence study findings included the perceived low value of postnatal care for healthy women and infants; concerns around access and quality of care; and women’s desire for more emotional and psychosocial support during the postnatal period. These findings highlight multiple missed opportunities for postnatal care promotion and ensuring continuity of care.

Conclusions

Factors that influence women’s utilization of postnatal care are interlinked, and include access, quality, and social norms. Many women recognised the specific challenges of the postnatal period and emphasised the need for emotional and psychosocial support in this time, in addition to clinical care. While this is likely a universal need, studies on mental health needs have predominantly been conducted in high-income settings. Postnatal care programmes and related research should consider these multiple drivers and multi-faceted needs, and the holistic postpartum needs of women and their families should be studied in a wider range of settings.

Registration

This protocol is registered in the PROSPERO database for systematic reviews: CRD42019139183.

Citation: Sacks E, Finlayson K, Brizuela V, Crossland N, Ziegler D, Sauvé C, et al. (2022) Factors that influence uptake of routine postnatal care: Findings on women’s perspectives from a qualitative evidence synthesis. PLoS ONE 17(8): e0270264. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270264

Editor: Hannah Tappis, Jhpiego, UNITED STATES

Received: September 20, 2021; Accepted: June 7, 2022; Published: August 12, 2022

Copyright: © 2022 Sacks et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting information files.

Funding: Funding was provided by the UNDP/UNFPA/UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP), Department of Reproductive Health and Research, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Abbreviations: LMIC, Low- or Middle-Income Countries; MeSH, Medical Subject Headings; PNC, Postnatal Care; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses; WHO, World Health Organisation

Postnatal care (PNC) is a fundamental component of the maternal, newborn and child care continuum, and contributes to reducing maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality and improving overall health and wellbeing [ 1 – 3 ]. It is generally defined as the care provided during the postnatal period, beginning immediately after childbirth and up to six weeks (42 days) after birth [ 1 ] or beyond [ 4 ]. PNC represents a set of healthcare services designed to promote the health of women and newborns; it includes risk identification, preventive measures, health education and promotion, and management or referral for complications. Postnatal care not only improves mortality and clinical care, but also affects the satisfaction and experience of health care users; understanding the experiences and needs of women and their families with regard to postnatal care can improve utilization and positive experiences. The World Health Organisation (WHO) recommends that all women and newborns receive postnatal care in the first 24 hours following childbirth, regardless of where the birth occurs, and subsequent postnatal check-ups in the first six weeks [ 5 ].

Nevertheless, postnatal care ranks among the lowest coverage of maternal and child health services interventions; after facility discharge, only 31% of women and 13% of newborns receive a postnatal check [ 6 , 7 ]. Previous studies have also identified important socioeconomic and geographic inequities in access to and utilisation of postnatal care services [ 8 ].

Over the last two decades, there have been multiple contributions to a large and growing canon of literature on facilitators and barriers to maternity care, including recent systematic reviews [ 9 – 11 ]. However, most of these studies have focused on care-seeking for intrapartum care and immediate PNC (within 24 hours), and not later (e.g. post discharge) postnatal care [ 12 – 14 ]. Much of the literature on maternity care focuses on facilitators and barriers to utilization [ 15 – 18 ] but, as low quality care has recently been associated with a potentially higher attributable risk of mortality than lack of access [ 19 ], studies have begun to examine perceived and actual quality of care, including disrespect and abuse at facilities, as contributing factors to low utilisation of maternal health services [ 15 – 18 ]. Very few studies have examined the impact of mistreatment or disrespect of newborns as discouraging factors for uptake of postnatal care, but recent studies have demonstrated the importance of satisfaction with maternal and neonatal care on subsequent care utilization [ 20 , 21 ].

This paper presents the results of a sub-set of the data from a qualitative evidence synthesis designed to explore the views and experiences of women, their partners, families and communities in the postnatal period, and factors that influence uptake of routine postnatal care. For this analysis, our aim was to assess the views and experiences of women in the general population in accessing routine postnatal care for themselves and their infants.

We included qualitative or mixed-methods studies where the focus was the views of women in the general population (i.e. excluding sub-populations such as adolescents or migrants) on factors that influence uptake of routine postnatal care (i.e. those without additional postnatal needs due to comorbidities or identified medical risk), irrespective of parity, mode of delivery, or place of delivery. Qualitative studies and mixed methods studies were those that included a qualitative component, either for design (i.e. ethnography, phenomenology), data collection (i.e. focus groups, interviews, observations, diaries, oral histories), or analysis (i.e. thematic analysis, framework approach, grounded theory).

A framework approach was used to inductively develop initial themes [ 22 ] and thematic synthesis [ 23 ] and was then used iteratively based on the initial thematic framework. Study assessment included the use of a validated quality appraisal tool [ 24 ]. Confidence in the findings was assessed using the GRADE-CERQual tool [ 25 ].

Definitions

We define the postnatal period as the time between birth, including the immediate postpartum period (first 24 hours after birth), and up to six weeks (42 days) after birth [ 1 ]. This period varies cross-culturally, but usually coincides with confinement periods and other cultural practices in the 30–45 days following birth.

We define ‘routine postnatal care’ as formal service provision that is specifically designed to support, advise, inform, educate, identify those at risk and, where necessary, manage or refer women or newborns, to ensure optimal transition from childbirth to motherhood and childhood. Postnatal care can include a wide range of activities, including risk identification (assessments, screening), prevention of complications, health education and promotion (infant feeding and care, life-skills education, postpartum family planning, nutrition, vaccines, mental health support, and prevention and management of harmful practices—including smoking and alcohol—and violence) and support for families. Routine postnatal care does not typically include specialist services for comorbidities, address social needs, or the management of conditions not related to pregnancy or postpartum care, though referrals can be made for such services as a result of routine postnatal care.

Reflexive statement

Our study team included a medical doctor, a midwife, epidemiologists, public health researchers, and librarians, all with extensive experience in the provision and study of maternal and neonatal healthcare. We began this study with anecdotal and experiential knowledge that postnatal care is very often unavailable or inadequate, with minimal emphasis on the psychosocial needs. We believed PNC to be poorly and inequitably accessible, even in high-income settings, and especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), and that due to perceived or actual poor quality care, including potential fears of mistreatment, and services not being user-friendly, families may be discouraged from seeking care. Multiple members of our study team have been involved in the direct provision of postnatal care, and in developing national and international guidelines for postnatal care.

Search strategy

The search strategy was developed with senior librarians based on the following concepts: barriers and limitations, postnatal care, and health services needs and demands. The search was limited to qualitative and mixed-methods studies (see S1 Appendix ). Databases searched included MEDLINE (OVID), PubMed, CINAHL (EBSCO), EMBASE (OVID), and EBM-Reviews (OVID), as well as a search for grey literature. The search strategy covered papers published from inception through December 2019. There were no language restrictions. Hand searching was used to identify grey literature documents on the following websites: BASE (Bielefeld University Library), OpenGrey, and on the World Health Organization. Duplicates were excluded through the EndNote X9 software using a method developed by Bramer et al. [ 26 ] Inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in Table 1 .

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270264.t001

Study selection

- Either “general population” or sub-populations such as adolescents, migrants

- “Women’s view’s only”, “partners and family views only”, or “women’s, and partner/family views”.

- Either high-income (HIC) or low or middle-income (LMIC) country setting, using the 2019 World Bank Classification Scheme.

In accord with the global nature of the review, and to ensure sufficient representation of country levels especially lower income settings, we divided the studies into either HIC or LMIC for sampling. Due to the very large number of eligible papers, 40 papers (~15%) from each geographic group (HIC or LMIC) were randomly sampled at a time, and screening and extraction was conducted until it was agreed by consensus that thematic saturation was reached for each geographic group, at which point 10 additional papers were selected from each group for confirmatory analysis (if saturation was not, 20 more papers were selected for that group, until it was agreed that saturation was reached, at which point a confirmatory set was then selected). Prior to undertaking this process, it was agreed that, if no further themes were identified after confirmatory analysis, the group was considered saturated.

Extraction of data and assessment of quality was conducted for each eligible paper by study team members. Disagreements were settled by consensus among reviewers. Themes from HIC and LMIC groups were analysed together, which notations made where the specifics or manifestation of each theme different between country groups.

Study team members did not assess papers in which they were a co-author. Two of the included studies were published in a language other than English: a Brazilian study [ 27 ] was analysed by one of the study team members fluent in Portuguese and a Japanese study [ 28 ] was translated by a Japanese-speaker into English prior to analysis. All quotes included in this manuscript were translated into English by the study authors, the respective study team members, or colleagues who assisted with translation.

Papers which did not meet either the general or specific inclusion criteria upon full review were either excluded or put aside to be evaluated separately for future analysis. Studies which did not include first-hand reports of women’s experiences were excluded; studies which focused exclusively on a sub-population (e.g. young adolescent mothers) were put aside for separate subsequent analysis.

Data extraction and analysis

Data extraction, analysis and quality appraisal proceeded concurrently and broadly followed the ‘best fit’ framework approach described by Carroll [ 22 ]. Based on previous related reviews of antenatal care [ 29 ] and intrapartum care [ 30 ] as well as a recent thematic synthesis of ‘what matters to women’ during the postnatal period [ 31 ] we used a deductive approach to develop a thematic framework comprising four broad concepts (Resources and access; Behaviours and attitudes; External influences; What women want and need) as well as a number of sub-themes (see S2 Appendix ). We then used thematic synthesis techniques [ 23 ] to confirm our a priori framework, or to develop new themes where emerging data failed to fit. We began by using an Excel spreadsheet to record pertinent details from each study (e.g. author, country, publication date, study design, setting and location of birth, setting and location of postnatal care, sample size, data collection methods, participant demographics, contexts, study objectives). The four concepts from our a priori framework were added to the Excel sheet and the author-identified findings from each study were extracted (along with supporting quotes) and mapped to the framework as appropriate. Any codes which did not map to the framework were placed in a section marked ‘other’ to allow for the emergence of new sub-themes or concepts. This process included looking for what was similar between papers and for what contradicted (‘disconfirms’) the emerging themes. For the disconfirming process we consciously looked for data that would contradict our emerging themes, or our prior beliefs, and views related to the topic of the review.

Quality assessment

Included studies were appraised using an instrument developed by Walsh and Downe [ 32 ] and modified by Downe et al. [ 33 ]. Studies were rated against 11 pre-defined criteria [ 33 ], and then allocated a score from A–D (including + and -), where A+ was the highest and D- the lowest (see Table 2 ). Studies rated with a D were excluded from further data analysis.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270264.t002

Studies were appraised by each reviewer independently and a 10% sample was cross-checked by a different study team member to ensure consistency. Each reviewer was asked to extract and assess both LMIC and HIC papers in order to increase intra-rater reliability between the two geographic groups. Any studies where there were scoring discrepancies of more than a grade were referred to another study team member for moderation.

Once the framework of descriptive themes (or review findings) was agreed by the study team, the level of confidence in each review finding was assessed using the GRADE-CERQual tool [ 34 ] and agreed by consensus between two study team members. GRADE-CERQual assesses the methodological limitations and relevance to the review of the studies contributing to a review finding, the coherence of the review finding, and the adequacy of data supporting a review finding. Based on these criteria, review findings were graded for confidence using a classification system ranging from ‘high’ to ‘moderate’ to ‘low’ to ‘very low’. Following CERQual assessment the review findings were grouped into higher order analytical themes and the final framework was agreed by consensus amongst the study team.

Papers included in overall study and analytic sample

Our systematic searches yielded 12,678 records, of which 17 were duplicates. An additional 12,149 were excluded by title and by abstract, leaving 602 for full text review (See Fig 1 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270264.g001

Our final list of articles for the analytic sample included 59 studies with views from women in the general population on routine postnatal care, with 32 coming from HICs and 27 from LMICs. Specifically, of the LMIC studies, 6 were from low income countries, 12 from lower-middle income countries, and 9 from upper-middle income countries. The global representation of studies was reasonably wide with 17 coming from Europe, 13 from Africa, 10 from North America, 9 from Asia, 4 from the Middle East, 4 from Australasia, and 2 from South America. The two South American studies were both from Brazil and, although we actively searched our entire database for studies from other Latin American countries, no others fulfilled our inclusion criteria. The studies were generally of good quality with an average quality rating of B and were mainly qualitative and descriptive in design. A full list of the included studies with relevant characteristics is shown in Table 3 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270264.t003

This process generated 20 review findings. Following discussions amongst the study team, these descriptive themes were then mapped against our a priori framework themes to generate our final analytical themes. Resources and Access was split into two separate themes: Access and Availability and Physical and Human Resources . We changed Behaviours and Attitudes to Social Norms to better reflect the larger group of stakeholders influencing maternal choice or behaviour, and we changed the title of What Women Want and Need to Experience of Care to better reflect the experiential nature of the findings.

Our analysis reinforced some aspects of the themes in our a priori framework and modified or expanded others. This final framework includes twenty-one themes and five overarching study findings: Access and Availability; Physical and Human Resources; External Influences; Social Norms; and Experience of Care . Our final framework displaying the analytical themes and descriptive themes, with their associated CERQual gradings, is shown in Table 4 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270264.t004

Themes identified from included studies

Access and availability..

Whilst proximity to a health facility appeared to encourage engagement with maternity providers, our evidence suggests that, for some women living in remote or rural areas, a lack of transport or the poor quality of transport networks limited attendance at postnatal clinics. This was compounded in situations where women did not have the personal resources to pay for relatively expensive journeys to health facilities and/or could not afford to take time away from their work or family. Even in high income settings where access to postnatal services is ostensibly free at point of care, the additional costs associated with attendance including insurance levies, childcare costs, and transport costs limited engagement for women living in poverty.

For accessing postnatal care post-discharge from a health facility after birth, women wanted a wide range of possible options and flexible schedules for reaching healthcare workers. Women generally valued the ability to contact providers at convenient times even more so than having a large number of contacts. Women wanted to be able to get support during moments of high stress, or on their schedules, rather than on a pre-defined health systems schedule, and many referenced the value of their time. Women expressed frustration about not being able to reach healthcare workers when needed. Service providers that were able to offer more flexible opportunities for engagement like drop-in clinics, telephone contacts, out of hours services and, in particular, home visits, were viewed more positively.

Physical and human resources.

For women in a variety of different settings, the ability to engage with formal postnatal services was influenced by resource and infrastructure constraints, especially in settings where community-based services were limited or non-existent. The evidence also suggests that the poor availability of resources in some health facilities may act as a deterrent to women who might otherwise benefit from postnatal care. A lack of basic medicine and equipment and inadequate or inconsistent water or electricity supplies limited attendance in some low-income settings. Whilst the availability of essential equipment and utilities was not reported to be an issue in most high-income countries, women were sometimes aware of staff shortages on postnatal wards and this affected their experience of care. Women’s perception that some health facilities were understaffed, especially from studies in LMICs, was also reflected in the length of time they had to wait to be seen by a healthcare provider. In some instances, this was compounded by cursory and impersonal exchanges with care providers, leaving women feeling frustrated, annoyed and undervalued.

External influences.

Women identified several external influences as having a bearing on their engagement with postnatal services. These ranged from environmental influences such as the physical condition of the health facility itself to the availability and affordability of private providers to a willingness (or otherwise) to engage with traditional postnatal practices, either in accordance with or against the advice of family and community members.

For women in a variety of different settings and contexts, the condition of postnatal wards and health facilities was important. Women used words such as ‘clean’ and ‘modern’ to frame positive perceptions or ‘dirty’ and ‘unhygienic’ to highlight negative experiences. These negative accounts were more commonly associated with facilities in low-income settings but even in high income countries women used words like ‘dilapidated’ and ‘unwelcoming’ to describe postnatal wards. In addition to the condition of the buildings, women also commented on the lack of physical space in some facilities and how this impacted on their sense of personal space and perception of privacy. Some women felt the opportunity to engage in confidential conversations with family members or healthcare providers was compromised whilst others felt the shared facilities and tight surroundings in some postnatal wards generated a noisy and disruptive atmosphere. For mothers who already felt exhausted and fatigued from childbirth, the impact of this environment coupled with their inability to control system-oriented, organizational routines, led to feelings of frustration and exasperation.

By contrast, for women who gave birth at home, the nurturing nature of familiar surroundings as well as their ability to establish personal routines and control access to their home created a more relaxing environment. In settings where private facilities were available, they were generally considered to be of better quality and were utilised by some women with the financial means to do so. However, in some contexts, the integration between private and public providers was inadequate and impacted on women’s engagement with postnatal services once they were discharged from the health facility.

Women’s capacity to engage with postnatal services was influenced by other family members and individuals in their social circles. In some contexts, women’s autonomy was inhibited by patriarchal social structures and decisions relating to engagement with maternity services, including postnatal care, were largely deferred to husbands. Sometimes, these kinds of decisions were agreed jointly between the woman’s husband and her mother-in-law and sometimes the decision was solely the responsibility of the mother-in-law.

Women expressed that elderly relatives and the broader beliefs and expectations of local communities influenced their observance of traditional postnatal practices rather than ‘westernised’ approaches to postnatal care, which some may have preferred. In some rural communities, especially in Africa, the reliance on TBAs to administer specific herbs and medicines in the postnatal period was integral to a communal belief system, whilst in other settings it was simply more convenient or financially viable. For other women, especially in Asia, the cultural practice of ‘doing the month’ involved extended periods of isolation and seclusion and limited interaction with formal postnatal services. Our findings also indicate that, in these contexts, some women (and their families) found it difficult to steer a course between the increasing influence of “Western” approaches to postnatal care and adhering to the traditional practices advocated by previous generations.

Social norms.

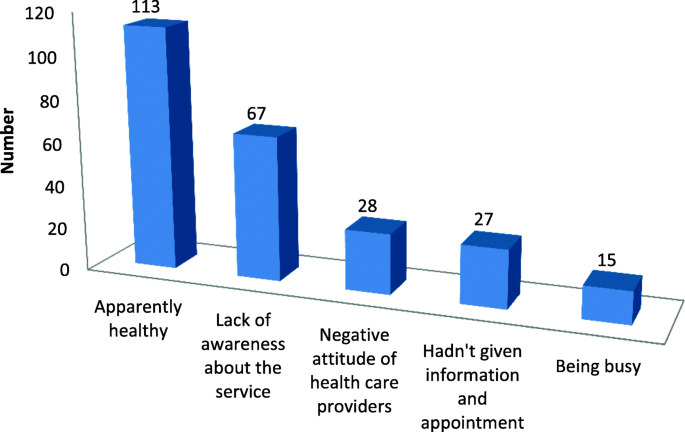

Women highlighted a variety of behaviours and understandings about the health system that affected their willingness to engage with postnatal care providers. For some women, especially from studies in LMICs, these understandings were based on a perception that attendance at health facilities offering postnatal care was only necessary if they felt unwell or if there was a problem with their infant. In many cases, this notion was reinforced by healthcare providers who did not encourage attendance or devalued the services they offered. When health workers devalued PNC, families also tended to devalue PNC and not see the need to seek care.

Some women also believed that postnatal services were solely focused on infant wellbeing and development and, although they valued the services on offer for newborns (clinical assessments and immunizations), they were not aware of, or did not acknowledge, any sources of care and support for themselves.

For some women, a reluctance to engage with postnatal services was rooted in a lack of trust in the system. In certain contexts, this was based on a perception that some providers were corrupt and expected informal payments, gifts, or bribes in return for care. In other settings, women’s trust in the system was undermined by perceived inadequacies in the clinical or personal skills of the healthcare providers. More infrequently, women complained that confidential information shared with health providers might be compromised or abused and, in more extreme cases, women believed that disclosure of mental health issues (like postnatal depression) might lead to their infant being taken away from them. In a few specific contexts, women expressed a preference to be seen by female health providers and highlighted safety concerns when postnatal visits at home were conducted by male health workers.

Experience of care.

Based on their experiences of postnatal care, women identified a range of issues that were of particular importance during their postnatal journey, including the need for information and support and the desire to be treated with care and respect by familiar and trusted healthcare providers.

Women from a variety of different settings and contexts highlighted the need for information during all phases of postnatal care. Although some of these informational needs were met by friends, peers, family members and online sources, women looked to healthcare providers for information about infant nutrition and development as well as tips and advice on infant crying cues, sleeping patterns, breastfeeding, and safety concerns. Although women tended to prioritise the needs of their newborns over their own, they also sought personal information for example on wound care, contraception, and when to resume sexual activity. The timing and delivery of information was also discussed by many women indicating that information should be supplied both antenatally and postnatally and given in a clear and consistent format. For some women, intense emotions of joy and elation coupled with feelings of extreme fatigue affected their ability to absorb information in the immediate postnatal period, whilst for others, the sheer volume of information was difficult to process.

In addition to a need for information, women also identified needs for both practical support and, especially in high-income countries, for psychosocial support. In a practical sense, women appreciated the support they received from family members but also valued support from healthcare providers, particularly in the immediate postpartum period, prior to hospital discharge, when they were trying to bond with their newborn and/or establish breastfeeding. Help with specific newborn-oriented tasks like nappy changing and bathing as well as tending to the newborn whilst the mothers recuperated, showered, or carried out chores, were highlighted and, in some instances, women felt disappointed when these needs were not recognised.

In many settings, women also highlighted the need for ongoing practical support once they returned home and, although this was often facilitated by family members, women also appreciated assistance from healthcare providers during the transition to motherhood. Usually this was a continuation of the advice received in hospital relating to infant feeding and development but, in uncommon circumstances, women received visits from associated agency workers to helped with domestic activities (shopping, cleaning, cooking) and these services were highly valued.

Many women experienced intense emotional peaks and troughs during the postpartum period ranging from elation to despair to overwhelming exhaustion. Women, particularly first-time mothers, discussed their fears, anxieties, and insecurities about becoming a mother and, for some, the pressure and responsibility of living up to some idealised version of a mother. Women wanted support from healthcare providers to help them to process and manage these difficult emotions and often expressed this in terms of a need for reassurance. In some contexts, particularly in high-income settings, where much of the published evidence comes from, women wanted to discuss the birth experience with a midwife who was present or have access to healthcare providers support if they felt their birth was challenging or traumatic.

In a broader sense, many women felt that their own care needs were overlooked or undervalued during the postpartum period. Whilst new mothers completely accepted and understood that the focus of postnatal care was on their infant, they nevertheless felt disappointed when unvoiced pleas for attention or recognition were ignored by healthcare providers.

Our findings also indicate that women placed great importance on their ability to build a relationship with care providers and this was particularly apparent in high-income settings. For some women this involved seeing the same healthcare provider at each postnatal contact, for others it meant being able to see the same midwife during the postnatal period as they saw antenatally, and for women who gave birth at home, the prospect of having the same midwife throughout their maternity journey played a significant role in their decision to opt for a homebirth. Where women were able to build these relationships, they were more likely to report ‘a sense of companionship’, ‘trust’ and ‘authenticity’, but in settings where continuity of healthcare models were not in place, women reported feeling ‘dissatisfied’, ‘like a number’ or even, ‘like an animal’.

For women in several contexts, interactions with healthcare providers sometimes became disrespectful and abusive. In high income settings, women indicated that healthcare providers could be rude or undermining and occasionally discriminatory during postnatal encounters, whilst in lower-income contexts women reported acts of rudeness, humiliation and, in rare cases, punishment by health providers.

Factors that influence women’s utilization of postnatal care are interlinked, and include access, quality, and social norms. Five review findings were identified: access and availability; physical and human resources; external influences; social norms; and experience of care. Many women recognised the specific challenges of the postnatal period and emphasised the need for emotional and psychosocial support in this time, in addition to clinical care.

Staffing and resources were important to women, although in low-resource settings, more emphasis was placed on poor physical infrastructure. In low- and middle-income countries, women further expressed that healthcare providers themselves often devalued postnatal care, contributing to their lack of utilization and sense of unpreparedness. Many studies from high-income countries highlighted women’s desire for more psychosocial and emotional support; yet, women in low income settings may not have been asked as directly about this challenge. Women also may not believe this is a role of the health system, or may not feel comfortable stating this as a vulnerability. These findings point to the need to strengthen comprehensive health care services, which can more fully address the holistic and ongoing needs of women and their families.

Many of the findings related to experience of care derived from high-income countries. Because of the number of included studies related to this topic were biased toward high income countries, this review finding should not be interpreted necessarily as women in low- and middle-income countries having positive experiences of care; evidence indicates that disrespectful practices are common globally [ 93 ]. This area is understudied in low- and middle-income countries and therefore it is difficult to draw robust conclusions. However, it is likely that women in settings with insufficient resources will more often refer to unhygienic conditions or lack of equipment as a more immediate priority than their experiences, and/or that they perceive less ability to change the situation than women in settings with more resources. A recent qualitative evidence review of studies in sub-Saharan Africa affirmed that aspects of respectful and disrespectful maternity care and women’s previous experiences of health care influenced their “decisions to access postnatal care services” [ 94 ]. The fact that many of the studies related to experience of care are from high-income settings may reflect the study authors’ biases and points to the need to study women and families’ experiences more holistically in low- and middle-income settings.

When situating this review within the context of other research [ 29 ], many similarities emerge in review findings across various phases of maternity care. From antenatal and intrapartum through postnatal care, women emphasised the need for information, continuity of care, adequate resources, and comprehensive and holistic support. Access and cost continue to be issues for many women, especially in low- and middle-income countries and in rural areas, but compared with intrapartum care, the incentive to overcome these challenges is further diminished with the devaluing of postnatal care and perception of low need for healthy women and their healthy infants. In the postnatal period, women’s access needs include when and how they can contact healthcare providers and for what purposes. Women greatly value continuity of care and flexible schedules for obtaining information and assistance. Infrastructure and health system resources play into both decisions about if and when to seek care, as well as the experience of care itself. This pattern and commonality across maternity care periods reflects the fact women may seek care from the same places and thus experience some of the same facilitators and challenges, but also emphasises women’s perception that maternity and the postnatal period are a continuum. The factors influencing postnatal care utilization may be different than other maternal and child health services for a number of reasons: postnatal may not be seen as important (especially if the woman and newborn are apparently healthy); during the postnatal care period, maternal and newborn needs may arise at the same time, adding to complexity of recognition and care seeking; and health care visits may take place in the home, unlike visits which must take place in a health facility. However, many of the same factors may be at play, including the recognition of need, the perception of quality, and the physical barriers such as cost and distance.

The review findings on postnatal care utilization largely conform with previous studies around what women want during this time period, as well as challenges related to access, health system quality, and experience of care. Our review builds on previous work in postnatal care utilization by explicitly including both women and newborns. The strengths of this review include a rigorous methodology, comprehensive search, very large database, wide search terms and concepts, and a diverse study team. Our review encompassed a geographically and linguistically diverse search, with a balance of papers from high, middle, and low-income countries, although the number of available studies from certain regions (e.g. Latin America and the Eastern Mediterranean) were limited. Despite the design of the search to be global, including a lack of language restrictions, we identified few papers from Australasia, Middle East, and South America.

Some potential limitations of the study include the limitations of the included papers themselves, especially the different prioritised topics studied in different regions of the world. Although the objectives of the included papers represented a range of topics, it is possible that certain areas, as well as certain topics in each region, are understudied. While we acknowledge that there may be context specific issues, we are bound by the content of the included studies and recognise that different questions may have been posed to participants in different contexts, depending on the nature of the research inquiry and the pre-existing beliefs of the research team members of those particular studies. Further, the World Bank Country Classifications are broad and group countries with very different profiles together. Country-specific terminology (such as the specific words used in a particular setting around health insurance or a certain cadre of support worker) may not have been captured.

As with other systematic reviews, there is a trade-off between speed and comprehensiveness and, while our use of sampling could limit our interpretation, our iterative process until reaching saturation increases confidence in our findings [ 95 , 96 ]. New studies have been published since the end of the search that were not included, however, the comprehensiveness and rigor of our search and analysis provides confidence in the findings.

Many papers identified in our search included the term “postnatal care” but in fact referred only to intrapartum care. It was difficult to disentangle experiences of postnatal care by time period as this was rarely disaggregated in studies. The differentiation was included in our extraction form, but some papers reported on when data were collected and others on the period the respondents were referring to with the latter often encompassing multiple time points post birth. More research is needed in distinguishing the needs during the immediate (e.g. pre-discharge from a health facility) and later postnatal periods.

The findings from this study have implications at the individual, family, health system, and policy levels, and interventions may be needed to address factors at each. Individual empowerment of women may be insufficient if her partner, family, or community have significant influence in healthcare decisions. The desire of women to have increased emotional and psychosocial support may or may not be best served by existing cadres of medical providers. Future research should explore who the optimal providers might be and what the scope (and burden) might be for each type of provider, including traditional birth attendants [ 97 ] and non-medical carers. The intervening time from the end of our search to completion of analysis included the emergence of a global pandemic, which has already had significant impact on postnatal experiences and care utilization [ 98 , 99 ]. Further areas of research include the impact of the pandemic on care utilization, increased anxiety and psychosocial support needs [ 100 ], and the role of digital and virtual care technologies [ 101 ].

There are clear steps which can be taken to improve the quality, experience, and uptake of care for women and newborns in the postnatal period. The value of PNC should be promoted as part of quality improvement, health worker training, and community mobilization. As much as possible, care should be provided in a continuous and coordinated manner, between health facilities, clinics, medical offices, communities, and households. At each level there must be sufficient staffing, resources, and infrastructure to provide high quality of care. Efforts should be taken to eliminate barriers to cost and transport, including illegal or unethical barriers such as bribes and other out-of-pocket or unanticipated costs for care, and all types of abuse and denial of care.

Postnatal care must be positioned as a high priority for both the woman and the newborn, much like antenatal and intrapartum care, and not seen as an optional service, or one only accessed in cases of emergencies. As a pre-requisite for increased utilization of postnatal care, quality must be improved [ 102 ]. The benefit of postnatal care for the mother and entire family may increase utilization, especially if services are available to improve emotional and psychosocial support. The implementation of standards for quality of care and respectful care must move beyond childbirth to ensure a positive experience of postnatal care for all women and their newborns.

Supporting information

S1 appendix. full search strategy..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270264.s001

S2 Appendix. A priori framework.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270264.s002

S1 Checklist. PRISMA 2020 checklist.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270264.s003

Acknowledgments

The authors owe a debt of gratitude to Annie Portela at WHO for feedback on the analysis and manuscript. The authors also acknowledge the methodological inputs from the Cochrane EPOC group, specifically Simon Lewin, Claire Glenton, and Susan Munabi-Babigamura. Thank you to the many research assistants who worked on various stages of this review: Uktarsh Ojha, Clara Tam, Sakshi Jain, Sushama Sreedhara, Younghee Jung, Kate Cho, Lex Londino, Leonie Sawoh, and Prince Gyebi. Thanks to Kiriko Sasayama for assistance in translation of an included study.

- 1. WHO. WHO technical consultation on postpartum and postnatal care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

- 2. WHO. Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health. In. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

- 3. National Institute for Care and Health Excellence. Postnatal care quality standard [QS37]. London, UK; Published: 16 July 2013 Last updated: 20 April 2021.

- 4. American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Optimizing Postpartum Care. Committee Opinion. Number 736. May 2018.

- 5. WHO. WHO recommendations on maternal and newborn care for a positive postnatal experience. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022.

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 28. 野口真貴子,; 高橋紀子,; 藤田和佳子,; 安積陽子,; 髙室典子,札幌市産後ケア事業を利用した女性の認識, Journal of Japan Academy of Midwifery 2018;32(2):178–189

- 52. Hindley J. Having a baby in Balsall Heath: women’s experiences and views of continuity and discontinuity of midwifery care in the mother-midwife relationship: a review of the findings from a report of a research project commissioned by ’Including Women’. Birmingham Community Empowerment Network, Birmingham. 2005.

- 99. Unicef. Coronavirus could reverse decades of progress toward eliminating preventable child deaths, agencies warn. Press release 9 September 2020, New York, NY. https://www.unicef.org.uk/press-releases/coronavirus-could-reverse-decades-of-progress-toward-eliminating-preventable-child-deaths-agencies-warn/

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier Sponsored Documents

A qualitative study of first time mothers’ experiences of postnatal social support from health professionals in England

Jenny mcleish.

a NIHR Policy Research Unit in Maternal and Neonatal Health and Care, National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford, Old Road Campus, Headington, Oxford OX3 7LF, UK

Merryl Harvey

b School of Nursing and Midwifery, City South Campus, Birmingham City University, Westbourne Road, Birmingham B15 3TN, UK

Maggie Redshaw

Fiona alderdice.

Many women experience the transition to motherhood as stressful and find it challenging to cope, contributing to poor emotional wellbeing.

Postnatal social support from health professionals can support new mothers in coping with this transition, but their social support role during the postnatal period is poorly defined.

To explore how first time mothers in England experienced social support from health professionals involved in their postnatal care.

A qualitative descriptive study, theoretically informed by phenomenological social psychology, based on semi-structured, in-depth interviews with 32 mothers from diverse backgrounds. These were analysed using inductive thematic analysis, with themes subsequently mapped on to the four dimensional model of social support (emotional, appraisal, informational, practical).

There were nine themes connected to social support, with the strongest mapping to appraisal and informational support: for appraisal support, ‘Praise and validation’, ‘Criticism and undermining’, and ‘Made to feel powerless’; for informational support, ‘Is this normal?’, ‘Need for proactive information’, and ‘Confusion about postnatal care’; for emotional support, ‘Treated as an individual and heard’ and ‘Impersonal care and being ignored’; for practical support, ‘Enabling partners to provide practical support’.

Conclusions

Health professionals can play an important role postnatally in helping first time mothers to cope, develop confidence and to thrive, by taking every opportunity to give appropriate and personalised appraisal, informational and emotional social support alongside clinical care. Training and professional leadership may help to ensure that all health professionals are able and expected to offer the positive social support already offered by some.

Statement of significance

Becoming a mother for the first time can be stressful and some mothers struggle to cope.

What is already known

Social support from health professionals can help new mothers to cope with this transition, but their social support role is unclear.

What this paper adds

Appraisal and informational support from health professionals were very important for confidence and coping in first time mothers from varied socio-demographic backgrounds, whether or not they also had social support from a partner, family or friends. Emotional support was valued but had a more limited role. There was minimal practical support from health professionals.

1. Introduction

National guidance in England conceptualises the role of postnatal care to be primarily about support for the transition to parenthood [ 1 ]. Some women experience becoming a mother for the first time as a time of stress and poor emotional wellbeing, leading to psychological distress (including depression and anxiety) if they feel unable to cope effectively [ [2] , [3] , [4] ]. Social support – a person’s perception of the availability of others to provide emotional, psychological and material resources [ 5 ] – is an important factor in enabling a successful transition to motherhood [ 3 ]. Empirical research demonstrates that effective social support from health professionals can assist new mothers in coping with the stress of new parenthood by increasing their parenting confidence [ [6] , [7] , [8] ].

Social support is a multi-dimensional concept, commonly analysed as having four functional aspects — emotional, appraisal (affirmational), informational and practical [ 9 ]. Emotional support consists of words or actions that show love, liking, empathy, respect and trust, leading the recipient to believe that they are cared for, esteemed and valued [ 9 ]. Appraisal or affirmational support is the communication of information to enable positive self-evaluation, specifically affirmation of the rightness of what the recipient has done or said [ 9 ], and thus a key ingredient of constructive feedback [ 10 ]. Informational support is information provided to another at a time of stress [ 9 ], including information about a baby’s health and development [ 10 ]. Practical or instrumental support is the provision of tangible goods, services or aid [ 9 ], in this context specifically help with caring for the baby [ 10 ].

There are contrasting findings from different countries about the principal aspect of social support mothers report receiving from health professionals postnatally, for example practical or informational support on postnatal wards in Finland [ 11 ], and informational support in Ireland [ 8 ] and in the community in Finland [ 6 ]. This is complicated by different definitions, for example Salonen et al. [ 11 ] categorise ‘infant-care instructions’ as part of appraisal support and ‘directions for infant feeding’ as part of practical support, while Tarkka et al. [ 6 ] categorise information and advice on child development as part of affirmation support.

New mothers may receive social support from a variety of sources apart from health professionals, including their partner, parents, other family members, friends, neighbours, and community volunteers [ [6] , [7] , [8] , 12 ]. They may want and receive different aspects of support from informal and formal sources, so one does not replace the other [ 7 , 8 ]. Where the aspect of support received does not match the aspect of support desired, it may be ineffective or may increase rather than diminish stress [ 5 ]. In particular, where health professionals do not provide the emotional and affirmational support that new mothers want in the immediate postnatal period, interactions with health professionals may themselves become an additional source of stress instead of buffering the stress of new motherhood [ 7 ].

Mothers who give birth in England usually have access to free National Health Service postnatal care. This includes support from midwives and maternity support workers on a hospital postnatal ward or birth centre and in the community, a health visitor who takes over from the midwifery team as the lead practitioner approximately 10–14 days after birth, and a general practitioner who assesses the baby and mother at 6–8 weeks [ 1 ]. The social support role expected of health professionals in the postnatal period is poorly defined, but every interaction with a health professional in the postnatal period has a potential social support meaning for the mother, and being aware of these meanings these will enable health professionals to avoid harm and maximise their positive impact on maternal wellbeing [ 10 ]. In order to deepen understanding of their social support role and how it can contribute to maternal wellbeing in the transition to motherhood, this article explores how first time mothers in England experienced different aspects of social support from health professionals involved in their immediate postnatal care in the hospital or birth centre and in the community. It reports research that is part of a programme of work on first time mothers’ expectations and experiences of postnatal care that includes an online survey, antenatal interviews and a qualitative longitudinal study, which have been reported separately [ [13] , [14] , [15] ].

2. Participants, ethics and methods

2.1. study design.

This was a qualitative descriptive study [ 16 ], based on semi-structured, in-depth interviews, theoretically informed by phenomenological social psychology which focuses on participants’ lived experiences and subjective meanings of social interactions [ 17 ]. This ‘low-inference’ [ 16 ] design was chosen because the purpose was to explore participants’ own perceptions and thus to stay close to their accounts [ 17 ], while acknowledging the role of both participants’ understandings and the researchers’ interpretations in the production of knowledge [ 18 ]. Throughout the research process, the researchers worked with a reflexive awareness of their own perspectives on the transition to motherhood and postnatal care, based on professional knowledge and diverse personal experiences.

The University of Oxford Medical Sciences Inter-Divisional Research Ethics Committee (reference {"type":"entrez-nucleotide","attrs":{"text":"R52703","term_id":"814605"}} R52703 /RE001) approved the study.

2.2. Participants

The interviews reported in this paper were second (postnatal) interviews within a qualitative longitudinal study. Participants were women who had given birth to a live baby or babies in England in the past four months, and had previously taken part in a first (pregnancy) interview. The original recruitment criteria for the pregnancy interviews were: currently in the third trimester of pregnancy; aged 16 or over; planning to give birth in England; and had not given birth previously. Purposive maximum variation sampling [ 19 ] was used to recruit women with a range of socio-demographic characteristics, with a particular emphasis on seeking diversity in age, ethnicity, and socio- economic status using postcode quintiles [ 20 ]. Multiple recruitment strategies were used to include women who are less likely to participate in research [ 21 ] and in particular younger women and women living in more deprived areas, who are less likely to respond to maternity surveys [ 22 ]. These were: (1) an invitation at the end of an online survey about expectations of postnatal care, promoted on social media by parenting organisations; (2) an in-person invitation from a researcher to women attending three sessions of a young mothers’ antenatal group and two sessions of a free antenatal exercise class, each run by a community group in a different area of high deprivation; (3) an advertisement circulated on social media by a multiple birth charity. There was intentional over-recruitment at the stage of pregnancy interviews, to allow for the likelihood that some participants would drop out before the postnatal interviews and to ensure demographic variation. The only prior relationship between the researchers and the participants was the research relationship established during the pregnancy interviews.

Thirty two women took part in the postnatal interviews reported here, when their babies were 7–15 weeks old (median 11 weeks). A further eight women who had taken part in pregnancy interviews could not be contacted after birth. Background information about participants in postnatal interviews is shown in Table 1 .

Background informationabout participants.

2.3. Data collection

Data were collected through semi-structured qualitative interviews between January and July 2018. Topics included the help received from health professionals and others postnatally in hospital or birth centre and in the community, whether this matched what the mother felt she needed, and the impact the mother felt the postnatal care had on her. At the end of the first (pregnancy) interview, participants were asked for permission for the researcher to contact them approximately six weeks after their baby’s due date to arrange a second (postnatal) interview, either face-to-face at a time and place of their choice, or by telephone. Twenty nine postnatal interviews were by telephone and three were face-to-face, ranging in length from 21 to 56 min (mean 37.5 min). Informed consent to participate had been obtained before the pregnancy interview through a signed consent form if face-to-face, or given orally and recorded in writing when interviews were carried out by telephone; participants were reminded of this at the start of the postnatal interview and asked to confirm verbally whether they continued to consent. Participants were offered a shopping voucher worth £15 at the end of the interview, to thank them for their time. All interviews were carried out in English, although interpreting support was available if required. No one else (apart from babies) was present at the face-to-face interviews. Interviews were audio-recorded and fully professionally transcribed, with each participant being given an anonymous identifier beginning with PNC for ‘postnatal care’.

Data collection continued past the point where saturation was reached in these postnatal interviews (that is, participants were repeating what had been expressed by previous participants and there were no new codes or themes). Instead, all women who took part in pregnancy interviews were invited to take part in postnatal interviews. This was done to preserve the demographic variation of the initial sample, and to honour the commitment made to participants in the original participant information that they would be contributing to a qualitative longitudinal study through interviews before and after birth.

2.4. Data analysis

Inductive thematic analysis was carried out in parallel with ongoing data collection. Interview transcripts (which were the units of analysis) were checked against the audio-recordings, and read and reread for familiarity. Data were coded using NVIVO software. Codes were refined and combined as data collection continued, and themes describing manifest content were developed, using constant comparison to reconsider early analysis in the light of subsequent interviews. In order to explore the specific functional aspects of social support in postnatal interactions, themes were then mapped deductively onto the four dimensional model of social support [ 9 ], as widely used in social support research including Leahy-Warren’s concept analysis of social support for new mothers [ 10 ]. To increase the validity of the analysis, one researcher analysed all the transcripts and another analysed a subset; codes and themes were discussed and agreed. De-identified excerpts of interviews were selected to illustrate the findings.

3. Findings

There were 9 themes identified relevant to social support. Fig. 1 shows how these themes mapped on to the four functional aspects of social support. The strongest mapping was to appraisal and informational support. There were no differences identified according to socio-demographic background of mothers.

Themes and functional aspects of support interactions from professionals.

3.1. Appraisal support

There were three themes related to appraisal support: ‘Praise and reassurance’, ‘Criticism and undermining’, and ‘Made to feel powerless’.

3.1.1. Praise and validation

Many mothers described how, as first time mothers, they had no way to evaluate themselves: “I didn’t quite know what I was doing and what was right and what wasn’t right” (PNC110). They highlighted the importance of being reassured by midwives or health visitors that they were doing things ‘correctly’: “Praise, but not in a patronising way … ‘You’re talking to him, you’re engaging with him, he’s growing really well.’ … She just made me feel really good about what I was doing” (PNC060). Positive appraisal was felt to be much more meaningful when it came from a professional who was seen as objective, compared to friends and family who might be positive out of kindness: “And it’s different, when one professional says it, than when it’s like your mum or your friend says [insincere tone], ‘Oh you’re doing great!’” (PNC055). They were worried about being seen as “ a really over-exaggerating mother” (PNC105), so it was affirming to hear from professionals that having lots of questions was completely normal: “I expected for myself that I should know how to do all of this, and that was helpful at that stage to be told, ‘Nobody expects you to know what you’re doing, you haven’t done this before’” (PNC603). One mother commented that receiving only basic postnatal support had in itself felt like an affirmation of her parenting competence: “The fact that they haven’t felt that I’ve needed any extra help has given me confidence that I’m doing it right” (PNC224).

There were differences in the extent to which mothers believed that there was a ‘right’ way to carry out parenting tasks which they could master, and that health professionals were the experts in what this was. For example, one mother had asked midwives to watch her breastfeeding: “Just correct anything I’m doing wrong or [the baby] ’s doing wrong” (PNC055). Some others strongly preferred to be given non- directive advice and to make their own choices. Health professionals’ praise was often linked to how well the baby was growing and many mothers also accepted this as a reflection of their own performance as parents:

“Measurements and weight and things like that have all been spot on and I’ve always had nice compliments from midwives and the health visitor …You did get a lot of, ‘Well done, mum,’ pat on the back kind of thing. It was quite a confidence boost” (PNC158).

This carried the risk that if babies did not feed and gain weight as expected, mothers could feel that they were personally failing: “I was very tearful and upset about it, and I think that was because I had such strong ideas about what it was going to be like and the experience wasn’t matching up with that ” (PNC603).

3.1.2. Criticism and undermining

Many mothers reported encounters with professionals that disaffirmed their competence and undermined their confidence. They were given negative feedback in ways that left them feeling “like a little kid that had been told off” (PNC131), either through direct comments or body language such as eye rolling: “There’s quite a lot of pressure put on you in the hospital to be this perfect mum… They don’t quite say you’re being a terrible mother, but that’s how it felt … It makes you doubt everything that you’re doing a lot of the time ” (PNC250). This was particularly demoralising to mothers who were criticised when they were following a different health professional’s advice:

“She said, ‘What are you doing? You shouldn’t be doing that.’ We’d been told two days ago that that’s what we should be doing, it was then really confusing to be told something else, and she was quite abrupt in her manner and it was a bit of a knock to the confidence … It doesn’t make you feel very good” (PNC129).

Far from being reassured that their questions were welcomed and normal, some mothers described being made to foolish or incapable when they tried to get answers: “ It felt like I was being put back in my place with the sort of questions I was asking my health visitor” (PNC158). One mother had felt criticised and reprimanded in several encounters with professionals, and she reflected on the irony that they asked questions about maternal mental health but were lacking in self-awareness about the negative impact of their ordinary interactions with mothers:

“Why was she so angry at me about asking? … They concentrate so much on looking for signs of postnatal depression but don’t understand how they can just add to that, because then you’re left feeling like an idiot for asking a simple question” (PNC131).

Where a mother was struggling, it was very upsetting to feel she was being judged by someone who did not know the individual facts but was just giving generic advice, as in this example of a mother who was told by a health visitor at the six week check that combination feeding was not the best choice:

“She didn’t know the back story, she didn’t know us … On day 5 when we had the midwife it was like 90% formula, hardly any boob at all, and now it was about 75% breastfeeding and 25% formula, and it was something that we’d worked really hard at and it had taken a long time, and at a point I was really proud of, and then I just met her and she very quickly made it feel like it just wasn’t good enough.” (PNC194).

Another mother’s experience illustrates the sensitivity of new mothers to the possibility of implied criticism, when the health professional’s remark was intended to be affirming but sounded insincere because it was not related to the mother’s actual needs. This mother had just had an assisted birth:

“[The midwife] said, ‘Well, don’t feel disappointed with yourself’ … She was saying it more as like a platitude than a genuine, ‘You’ve done amazing.’ But I think because I wasn’t feeling disappointed or feeling like things had gone badly, her saying that then made me think, ‘Oh, maybe she’s thinking it didn’t go that well… actually maybe I should be disappointed’…I’m still upset about it” (PNC012).

3.1.3. Made to feel powerless

A few mothers reported that some health professionals had acted as though they had power over the mother’s and baby’s bodies that the mother had no right to challenge. Although this did not involve explicit criticism of the mothers (as in the previous subtheme), they had understood an implication that the mother was not seen as competent to make her own choices: “They think, ‘Oh yes, we’re God and you just trust us … We know, you don’t know anything’” (PNC702). Most of these situations related to professionals either administering medication or carrying out procedures without the mother’s informed consent: “Nobody told me that [my baby] had a chest X-ray or asked if that was okay” (PNC046). Others related to mothers being required to stay in hospital for extended periods without a clear explanation of why this was necessary, and feeling scared to disobey: “We weren’t allowed to leave the ward … I was getting to the point where I was just going to be like, ‘I’m just going to discharge myself,’ then I thought they might think I’m an unfit mother” (PNC250).

One mother had experienced multiple forms of disempowerment while in hospital, which had a dramatic impact on her emotional wellbeing, and affected her interpretation of routine aspects of postnatal care like electronic tagging:

“They had an electronic tag on [the baby]’s leg, which at first I thought was so they don’t steal your baby, and then I realised we can’t leave. So, I felt really trapped, like we were in prison … No one explained anything … They came and did a lumbar puncture at some point and didn’t tell me why. I thought [the baby] was going to be paralyzed … And people kept coming with more and more drugs for us... I didn’t want to be on antibiotics, and they didn’t give me an option. I wish I had known that I had that power [to give consent]… I ended up feeling like I’d failed [the baby], and at the beginning of his life story. I was so sad.” (PNC702).

3.2. Informational support

There were three themes related to informational support: ‘Is this normal? ’, ‘Need for proactive information’, and ‘Confusion about postnatal care’.

3.2.1. Is this normal?

Most mothers had checked with a professional about an aspect of their own health or their baby’s health or development that they were worried about, asking the question “Is this normal…?” Generally they had received the reassuring information that they needed, which also boosted positive self-appraisal. They strongly valued having ready access to professionals who could answer their questions:

“ I could always ring the postnatal ward in the hospital if there were any problems … Nearly every day that first week we had a midwife come, and that was really helpful and we were able to write down all our questions … I don’t think we would have coped nearly half as well without them.” (PNC110).

Most had received advice about feeding their babies, and a few commented that they had also received helpful information about practical aspects of baby care from an individual midwife or health visitor in response to specific challenges: “The best thing [the midwife] did for us was to give us advice that wasn’t ‘midwife advice’, that wasn’t necessarily about the weight of baby, the jaundice. It was more about, ‘Here’s something you can do so that you can get more sleep’” (PNC091).

Confidence in professional advice was seriously eroded for the many mothers who reported receiving conflicting information from health professionals, concerning issues such as how to breastfeed, expressing milk, swaddling, keeping babies warm, safe sleeping, self-care after a caesarean, oil for the baby’s skin, jaundice, tongue tie and vitamins. This made their advice appear to be anecdotal and unreliable:

“You would have a different midwife every eight hours and they had very different opinions of the clothes he should have on, how I should be feeding him, what I should be doing … if people are telling you different things, you don’t know who to listen to.” (PNC701).

A couple of mothers said they did not mind this inconsistency: “The plus side of that is you get two different opinions ” (PNC105). Diverse opinions opened space for a more confident mother to make her own choice, but she would also check the information against independent sources: “It seemed they had a favourite personal preference for doing things certain ways … it did mean that I could take what I wanted from whichever midwife… I definitely have continued to look stuff up myself as well” (PNC224).

Despite multiple experiences with advice that they found questionable, in principle most of the mothers wanted to get their information from health professionals or NHS- approved resources, believing that this was likely to be more reliable, up to date and evidence- based than information from other sources. Nonetheless all the mothers described how they sought out different kinds of postnatal information from different people. Even if they saw health professionals as approachable and accessible, they were selective in what they asked them, because they did not want to bother them with what might turn out to be unimportant questions: “I’ve relied more on my friends to ask them, because as much as [the health visitor] said you could call her any time, you kind of feel as though you can’t” (PNC192). Sometimes this was a strategic choice to prioritise professional information on specific topics: “ The health visitor it’s pretty much all about health, and then the other mums it’s about life” (PNC240). Other reasons for mothers’ reluctance to ask questions are explored in the next subtheme.

Very few mothers had turned to their own mothers as reliable sources of information: “Quite a lot of the advice has changed from when she had me” (PNC272). Generally they asked other recent mothers instead, in person, online or using group messaging. Some commented on the risks of relying on peers instead of professionals for information about ‘normality’, when those mothers might be trying to meet their own needs for affirmation either through boasting: “There’s a lot of competition, ‘My baby’s done this, my baby’s done that’” (PNC158), or competitive negativity: “I don’t tell them my baby sleeps so well, because I want to make friends. Everyone [at the baby group] really likes to complain and it’s like one- upmanship on how bad things are: ‘My baby only sleeps for two hours at a time!’ ‘Well my baby only sleeps for half an hour!’” (PNC105).

3.2.2. Need for proactive information

Although they valued the reassurance and advice they received, mothers identified a need for new mothers to be given important information in advance. Some had been given comprehensive written information: “ I got about 6000 leaflets from the health visitor when she first came, on every possible thing” ( PNC501). They questioned whether this format was useful to an overwhelmed new mother who would never have time to read it all to find what she needed, or was merely intended to tick the box that information had been given. What they wanted instead was proactive and concise information about key postnatal problems and typical scenarios for mother and baby, including crying, sleep and feeding:

“ I think they just try to cover themselves with lots of paper giving. At the time after you’ve given birth, you’re not going to be prepared to read all those leaflets, you’re struggling to keep your eyes open … A classic ‘this is normal’ guide would probably be helpful, and a solution page. So, ‘Is this normal to have this?’ and, ‘This is what you can do’” (PNC102).

There were several overlapping reasons for wanting health professionals to take responsibility for giving mothers relevant information, rather than waiting for mothers to ask. Some were inhibited from asking questions when they did not know the health professional, because of the risk of encountering someone judgmental: “It’s quite hard to ask someone questions without feeling bad or stupid in yourself when you’ve literally just met them” (PNC152). Some pointed out that first time mothers might find it hard to articulate a problem, because everything was unfamiliar: “I didn’t know what the question was. Because if I had just said that the baby is crying, that wouldn’t have been helpful ” (PNC704). This also applied to making the best use of routine contacts with health professionals: “She was asking if there was anything that I wanted to ask, and sometimes I find it a little bit difficult to know what I want to know” (PNC272). Another key reason for wanting to be given information before a problem arose was to prevent the considerable stress of worrying about the situation:

“We didn’t really sleep that first night because we were just watching to make sure [the baby] didn’t choke herself … the midwife on the triage [helpline] said, ‘Oh it just sounds like the mucus, it’s very normal,’ So that was good, but we were both left thinking, ‘If it’s so normal, why didn’t anyone tell you to expect it?’” (PNC055).

The biggest category of difficulties that mothers said they had not been warned about were related to feeding, particularly that latching on might be painful in the early days of breastfeeding, and the frequency with which a newborn might feed. Advance information about the reality of breastfeeding – “a bit more honesty” (PNC060) – would have prevented the loss of parenting confidence when mothers assumed they were to blame: