- Books / Audiobooks

- Learning Method

- Spanish Culture

- Spanish Grammar

- Spanish Travel

- Spanish Vocabulary and Expressions

- Study Guide

Spanish Essay Phrases: 40 Useful Phrases for an Impressive Writeup

7 Comments

May 30, 2019

Follow Us Now

Do you need to write a lot of essays in Spanish? If you do, don’t worry. It's about to get a little bit easier for you because here in this article, we’ve listed many useful Spanish essay phrases that you can readily use in your essays.

Feel free to pepper your essays with the words and expressions from this list. It would certainly elevate your essays and impress your teachers. You're welcome!

Get the PDF ( + MP3!)

No time to read now? Then you might opt to get the list in PDF instead. If you sign up to the newsletter, you'll get the list of Spanish essay phrases in PDF format plus free audio files.

Spanish Essay Phrases

Additional Resources

You can also check out the following resources:

84 Spanish Expressions for Agreeing and Disagreeing

Common Spanish Verbs

Expresiones útiles para escribir en español

Looking for more Spanish phrases? Check out this e-book with audio!

Try to use the essay phrases in Spanish that you learned in this lesson and write a few example sentences in the comments section!

About the author

Janey is a fan of different languages and studied Spanish, German, Mandarin, and Japanese in college. She has now added French into the mix, though English will always be her first love. She loves reading anything (including product labels).

VERY VERY useful !! Gracias

Amazing! This will definitely help me in tomorrow’s spanish test 🙂

Sounds good

Thanks for the assistance, in learning Spanish.

Amazing article! Very helpful! Also, this website is great for Spanish Beginners.

It’s easy when you put it that way

Session expired

Please log in again. The login page will open in a new tab. After logging in you can close it and return to this page.

Basic Guidelines For Writing Essays in Spanish

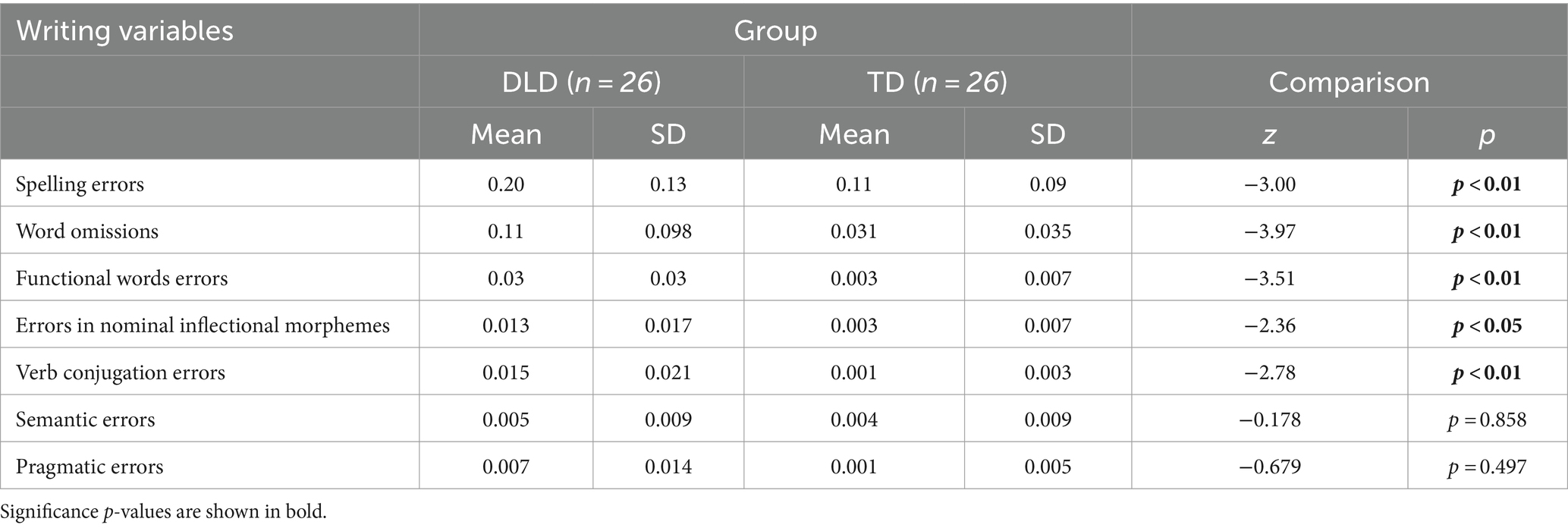

Students tend to focus on speaking practice while learning Spanish, so they often neglect writing. However, most educators emphasize its importance for mastering the language. They say it’s impossible to become fluent in a particular language if one doesn’t train writing skills.

Therefore, teachers give a lot of essay assignments to students. This type of homework is a great way to inspire them to think and communicate in Spanish effectively. It may be quite difficult to complete such a task. However, it’s one of the most effective ways to learn Spanish or any other language.

You may be tempted to go online and find the best essay writing service to have your essay written for you. This may be helpful when you’re pressed for time, but in the long run, you’re missing an opportunity to improve your own essay writing skills. That’s why we are going to provide you with some recommendations on how to ease the writing process.

Some tips on writing in Spanish

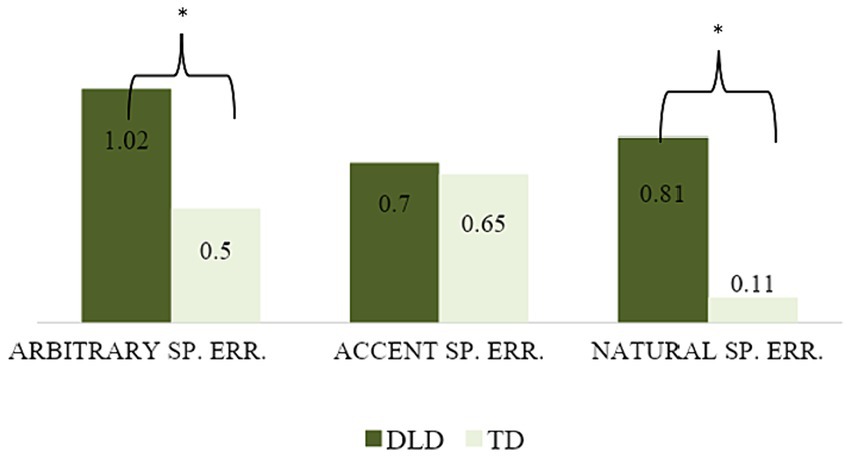

- Be careful with word spelling. Remember that teachers pay special attention to spelling so it can either make or break your student image. Having good spelling makes a positive impression of your writing skills and boosts your grades.

- Make your essay coherent with the help of connectors. Use them to explain the relationship between the ideas so your essay doesn’t look like just a list of thoughts and facts.

- Pay attention to syntax or the word order. As you need to stick to the academic style, try to keep the traditional order such as “subject + verb + objects”. This will also help you express your opinion in a simpler way, so it’s more clear to the reader.

- Avoid word repetitions by using synonyms. Frequent repetitions make your text boring and heavy. If you use the same words again and again, your essay will look dull. Hence, try to find synonyms in Spanish thesaurus and replace the most commonly used expressions with them.

- Before you create a final version of your essay, let someone read it and give feedback. It’s hard to be objective about your writing, so ask another person to tell you which ideas are less clear if your text contains any confusing phrases, and what are the positive aspects that can be reinforced.

- Do not write the essay in your native language first to translate it into Spanish then. This approach is not viable for mastering a foreign language. The only thing that you are doing by translating the text literally is practicing the grammatical structures that you have learned. This doesn’t help you learn new idioms and collocations that don’t follow the general grammatical rules.

Now that you know how to make your writing better, let’s consider a step-by-step guide to essay writing in Spanish.

Pick an interesting topic

If possible, choose a topic you are truly excited about. Unless the specific title was given to you by instructors, find a theme you want to research and write about. True interest is what will drive you towards creating an excellent piece. If you enjoy reading about the subject you are going to analyze in your essay, then you will definitely succeed in writing. Remember that decent work can be done only if you are passionate about it.

Brainstorm the ideas

When it comes to any project, brainstorming is an integral stage of the creation process. This is one of the most efficient ways to gain insights and generate new ideas. You can use this technique to think of the main supporting arguments, an approach for a catchy introduction, and paragraph organization. You can also try freewriting and/or make a brief outline to ease the writing process itself.

Create an introduction

Probably the main rule about creating an introduction that you have to stick to is adding a clear thesis statement there. It must be included in the first paragraph to give your essay a certain direction and help the readers focus their attention on the topic. Also, your introduction must be catchy and intriguing to evoke the desire to read the essay further and learn more.

Organize an essay body

It’s essential to make the body paragraphs organized logically. You need to make sure that each of them is closely related to the main topic and discusses one major point. Each body paragraph must consist of a topic sentence and supporting arguments with evidence. It’s very important to write sentences in a logical sequence so they follow each other orderly. Also, since paragraphs shouldn’t overlap in content, add smooth transitions from one to the other.

Sum up the content

The vital requirement to the conclusion is that it must logically relate to the original thesis statement. Generally, it’s not acceptable to introduce new ideas in the conclusion. Instead, you need to sum up the main points mentioned in the essay’s body. It’s also forbidden to add any off-topic ideas to the last paragraph of your paper.

Check content relevance and cohesion

Once you complete the conclusion, read through the essay for relevance and cohesion. Make sure that the whole piece is on the topic and in the mode required. In particular, check if body paragraphs support the thesis statement and whether the conclusion relates to it. After that, read your paper once again to see whether the parts connect together well. Think if there are logical links between ideas and if you need more transitions.

Read for clarity and style

Scan your essay to find out whether some sections may be unclear to the reader. Analyze the text to find out if it sounds academic and polished. Check if there are any vague pronouns, excessive wording, or awkward phrases. Don’t forget to make sure that all points are listed in similar grammatical forms.

The last stage of your writing process is final proofreading. Read your paper the last time looking at grammar, spelling, punctuation, verb tense, word forms, and pronoun agreement. Correct all the mistakes to make your work excellent.

Remember that the most important thing about learning a foreign language is a regular practice. Therefore, you should use any opportunity provided by instructors to polish your skills. Hopefully, the recommendations given above will help you write an excellent essay and master the Spanish language!

Take your first step to finally feeling comfortable speaking Spanish

Let's connect you with a hand-picked native-speaking tutor today.

51 Spanish Phrases for Essays to Impress with Words

- January 7, 2021

Joanna Lupa

Communicating in a foreign language is hard enough, even in everyday situations, when no sophisticated or academic vocabulary is needed.

Being able to write an actual essay in Spanish requires you not only to have a solid grammar base but also be knowledgeable about specific phrases and words typically used in school and university writing.

For those of you who study in one of the Spanish speaking countries or are toying with the idea of signing up for an exchange program, I have prepared a summary of useful Spanish phrases for essays. They are divided into the following categories:

- Connectors (sequence, contrast, cause and effect, additional information, and conclusion)

- Expressions to give your opinion, agree and disagree with a thesis

- fancy academic expressions

Spanish Connectors to Use in Essays

Written language tends to be more formal than the spoken one. Ideas get explained in complex sentences showing how they relate to each other. A fantastic tool to achieve that is connectors.

What are some useful Spanish connectors for essays? Let’s have a look at the ten examples below:

- 🇪🇸 primero – 🇬🇧 first

- 🇪🇸 segundo – 🇬🇧 second

- 🇪🇸 el siguiente argumento – 🇬🇧 the next argument

- 🇪🇸 finalmente – 🇬🇧 finally, last but not least

- 🇪🇸 sin embargo – 🇬🇧 however, nevertheless, nonetheless

- 🇪🇸 por lo tanto – 🇬🇧 therefore, thus

- 🇪🇸 además – 🇬🇧 besides

- 🇪🇸 por un lado….por el otro lado – 🇬🇧 on the one hand….on the other hand

- 🇪🇸 a menos que – 🇬🇧 unless

- 🇪🇸 a pesar de (algo) – 🇬🇧 despite / in spite of (something)

- 🇪🇸 aunque / a pesar de que – 🇬🇧 although / even though

- 🇪🇸 debido a – 🇬🇧 due to

- 🇪🇸 puesto que / dado que – 🇬🇧 given that

- 🇪🇸 ya que – 🇬🇧 since

- 🇪🇸 mientras que – 🇬🇧 whereas

- 🇪🇸 en conclusión – 🇬🇧 in conclusion

- 🇪🇸 para concluir – 🇬🇧 to conclude

Do you think you would know how to use these connectors in an essay? Let’s suppose you are writing about ecology:

🇪🇸 Los paises han estado cambiando sus politicas. Sin embargo, aún queda mucho por hacer. 🇬🇧 Countries have been changing their policies. However, there is still a lot to do.

🇪🇸 Una de las amenazas climáticas es el efecto invernadero. Además está la contaminación del agua que presenta un serio riesgo para la salud. 🇬🇧 One of the climate threats is the greenhouse effect. Besides, there is water pollution that presents a severe health hazard.

🇪🇸 A pesar de los acuerdos internacionales, varios países no han mejorado sus normas ambientales. 🇬🇧 Despite international agreements, many countries haven’t yet improved their environmental standards.

🇪🇸 Debido a la restricción en el uso de bolsas de plástico desechables, Chile ha podido reducir su huella de carbono. 🇬🇧 Due to the restrictions in the use of disposable plastic bags, Chile has been able to reduce its carbon print.

Spanish Phrases to Express Your Opinion in Essays

Essay topics commonly require you to write what you think about something. Or whether you agree or disagree with an idea, a project, or someone’s views.

The words below will allow you to express your opinion effortlessly and go beyond the typical “creo que ” – “ I think ”:

- 🇪🇸 (yo) opino que – 🇬🇧 in my opinion

- 🇪🇸 me parece que – 🇬🇧 it seems to me

- 🇪🇸 desde mi punto de vista – 🇬🇧 from my point of view

- 🇪🇸 (no) estoy convencido que – 🇬🇧 I am (not) convinced that

- 🇪🇸 no me cabe la menor duda – 🇬🇧 I have no doubt

- 🇪🇸 estoy seguro que – 🇬🇧 I’m sure

- 🇪🇸 dudo que – 🇬🇧 I doubt

- 🇪🇸 sospecho que – 🇬🇧 I suspect

- 🇪🇸 asumo que – 🇬🇧 I assume

- 🇪🇸 estoy (totalmente, parcialmente) de acuerdo – 🇬🇧 I (totally, partially) agree

- 🇪🇸 no estoy de acuerdo en absoluto – 🇬🇧 I absolutely disagree

- 🇪🇸 opino diferente – 🇬🇧 I have a different opinion

- 🇪🇸 me niego a aceptar – 🇬🇧 I refuse to accept

- 🇪🇸 estoy en contra / a favor de – 🇬🇧 I am against / in favor of

- 🇪🇸 no podría estar más de acuerdo – 🇬🇧 I couldn’t agree more

- 🇪🇸 encuentro absolutamente cierto / falso – 🇬🇧 I find it absolutely correct / false

Phrases like these can really give shape to your essay and increase its formality level. This time, let’s verify it with views on education:

🇪🇸 Opino que estudiando remotamente los jóvenes están perdiendo las habilidades sociales. 🇬🇧 In my opinion, remote schooling makes youngsters lose their social skills.

🇪🇸 Dudo que esta decisión traiga verdaderos cambios para el sistema educacional en mi país. 🇬🇧 I doubt this change will bring any real changes to the educational system in my country.

🇪🇸 Estoy totalmente de acuerdo con que todos deberían tener acceso a educación de calidad. 🇬🇧 I totally agree that everyone should have access to good quality education.

🇪🇸 Estoy en contra de escuelas solo para niñas o solo para niños. 🇬🇧 I am against girls-only or boys-only schools.

Pay attention to certain language differences between English and Spanish versions. The most common mistake that my students make is to say “ I am agree ” ❌ (direct translation from “ Estoy de acuerdo ”) instead of “ I agree ”✔️.

Fancy Academic Verbs and Expressions for Essays in Spanish

Would you like to impress your professor with sophisticated academic vocabulary or get extra points on your DELE? Grab a pen and take notes:

- 🇪🇸 afirmar – 🇬🇧 to state

- 🇪🇸 refutar – 🇬🇧 to refute, to reject

- 🇪🇸 argumentar – 🇬🇧 to argue that

- 🇪🇸 poner en duda – 🇬🇧 to cast doubt

- 🇪🇸 poner en evidencia – 🇬🇧 to shed light

- 🇪🇸 demostrar – 🇬🇧 to demonstrate

- 🇪🇸 concentrarse en – 🇬🇧 to focus on

- 🇪🇸 sostener – 🇬🇧 to sustain

- 🇪🇸 reflejar – 🇬🇧 to reflect

- 🇪🇸 considerando (que) – 🇬🇧 considering (that)

- 🇪🇸 siendo realista – 🇬🇧 realistically speaking

- 🇪🇸 de cierto modo – 🇬🇧 in a way

- 🇪🇸 en lo que se refiere a – 🇬🇧 with regards to

- 🇪🇸 en vista de – 🇬🇧 in view of

- 🇪🇸 de acuerdo a – 🇬🇧 according to

- 🇪🇸 no obstante – 🇬🇧 nevertheless

So many great words to work with! And some of them sound really similar to English, right? This is exactly why Spanish is such a good option when you want to learn a second language.

Let’s see how to make all these verbs and phrases work:

🇪🇸 Los resultados de los nuevos estudios ponen en duda la relación entre el consumo de huevos y altos niveles de colesterol. 🇬🇧 The recent study findings cast doubt on the relation between egg consumption and high cholesterol levels.

🇪🇸 Los autores del estudio argumentan que los azucares y los carbohidratos juegan un rol importante en este asunto. 🇬🇧 The authors of the study argue that sugars and carbs play an important role in this topic.

🇪🇸 En lo que se refiere al consumo de carne, este influye directamente los niveles de colesterol malo, sobre todo si es carne con mucha grasa. 🇬🇧 Regarding meat consumption, it directly influences the levels of “bad” cholesterol, especially in the case of greasy meat.

Spanish Resources

How to get a haircut in spanish, spanish past tenses – pretérito indefinido.

4 Awesome Blogs to Visit Before Your First Spanish Conversation

Your spanish journey starts here, privacy overview.

You are using an outdated browser. Upgrade your browser today or install Google Chrome Frame to better experience this site.

- Spanish »

- Spanish Language Learning Library »

Spanish Writing Practice

Spanish writing exercises by level.

Practise your Spanish writing skills with our ever-growing collection of interactive Spanish writing exercises for every CEFR level from A0 to C1! If you're unsure about your current proficiency, try our test to get your Spanish level before diving into the exercises.

All writing exercises are made by our qualified native Spanish teachers to help you improve your writing skills and confidence.

Kwizbot will give you a series of prompts to translate to Spanish. He’ll show you where you make mistakes as you go along and will suggest related lessons for you.

Boost your Spanish writing skills by adding the lessons you find most interesting to your Notebook and practising them later.

Click on any exercise to get started.

A1: Beginner Spanish writing exercises

- A business meeting Employment Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adjetivo posesivo Noelia tells us about her business meeting.

- A declaration of love Family & Relationships Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adjetivo posesivo Read this declaration of love from Enrique.

- A hotel booking Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adjetivo posesivo Borja is going to spend a week in Barcelona and tells us about the hotel that he is going to book.

- A love story Family & Relationships Adjetivo Adjetivo posesivo Apócope Marta and Andrew meet in a bar...

- A march for rare diseases Sports & Leisure Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adjetivo posesivo Diego is participating today in a charity march.

- A mysterious invitation Family & Relationships Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adjetivo indefinido Guillermo tells us about a mysterious note he found inside his locker.

- A new space suit Technology & Science Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adjetivo invariable Sergio is going to travel to the moon in a new space suit!

- A perfect day in Granada Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adjetivo invariable Travel with Enrique to Granada.

- A piece of cake, please Food & Drink Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adjetivo posesivo Carolina loves celebrating her birthday in style with her favourite cake.

- A purple tide Politics, History & Economics Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adjetivo indefinido Learn about the purple tide in Spain.

- A royal dinner in Santo Domingo Food & Drink Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adjetivo invariable Indulge yourself with a royal dinner experience in Santo Domingo.

- A sunny Christmas in the Southern Cone Celebrations & Important Dates Adjetivo Adjetivo posesivo Artículo definido Humberto tells us about Christmas in Uruguay.

- A ticket for Malaga, please! Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Adjetivo Adverbio Artículo indefinido César wants to get a train ticket to travel to Malaga.

- A trip to the Sierra de Atapuerca Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adjetivo indefinido Pedro and Miguel are visiting Atapuerca tomorrow.

- A very interactive lesson with Kwiziq Language & Education Technology & Science Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adverbio Clara is using kwiziq for the first time and tells us about a lesson she is taking.

- Alexis Sánchez: a famous soccer player Famous People Adjetivo Adverbio Artículo indefinido Learn about Alexis Sánchez, a famous soccer player.

- Amelia Valcárcel: a famous Spanish philosopher Famous People Language & Education Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adjetivo invariable Learn about Amelia Valcárcel, a famous Spanish philosopher.

- An exhibition by Frida Kahlo Art & Design Famous People Adjetivo Adjetivo invariable Adjetivo posesivo Marcos is going to a Frida Kahlo exhibition.

- An exotic flower Art & Design Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adjetivo posesivo Learn about this Argentinian flower.

- An original costume Celebrations & Important Dates Adjetivo Adjetivo posesivo Adverbio Lucía's mum tells us about her daughter's costume.

- Ana's baby shower Family & Relationships Adjetivo Adjetivo posesivo Artículo definido Some friends are planning Ana's baby shower.

- Animal welfare Family & Relationships Adjetivo Adjetivo invariable Adjetivo posesivo Step into the realm of animal welfare, where compassion guides us to protect and care for our animal companions.

- Arón Bitrán: a Chilean violinist Music Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adjetivo indefinido Learn about Arón Bitrán, a famous Chilean violinist.

- At El Corte Inglés Sports & Leisure Adjetivo Adjetivo indefinido Adjetivo invariable Have you ever been to El Corte Ingles?

- At the cocktail bar Food & Drink Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adjetivo invariable Raúl is having a refreshing cocktail in Majorca.

- At the nutritionist Food & Drink Adjetivo Adjetivo indefinido Adjetivo invariable Sheila is at the nutritionist looking for a healthier lifestyle.

- At the opera Music Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adjetivo invariable Ana plans to go to the opera tonight.

- At the science lab Technology & Science Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adjetivo invariable Marta and Javier love spending time in the lab.

- Bank of Spain Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Politics, History & Economics Adjetivo Artículo definido Artículo indefinido Learn about Bank of Spain.

- Benefits of sport Sports & Leisure Adjetivo Adjetivo indefinido Adjetivo invariable Mara tells us about exercising at the gym and its benefits.

- Blanca Paloma: Spanish candidate 2023 Music Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adverbio Meet Blanca Paloma, Spain's candidate for Eurovision 2023.

- Booking a table in a restaurant Food & Drink Adjetivo Adjetivo posesivo Artículo indefinido Learn how to book a table in a Spanish restaurant.

- Breakfast at home Food & Drink Adjetivo Adjetivo invariable Adjetivo posesivo Raúl loves having a healthy breakfast at home every morning.

- Buenos Aires International Book Fair Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Adjetivo demostrativo Artículo definido Artículo indefinido Learn about this cultural event in Buenos Aires.

- Calva: a traditional Spanish game Sports & Leisure Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adjetivo indefinido Learn about calva, a traditional Spanish game.

- Carnival in Rio de Janeiro Celebrations & Important Dates Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adjetivo invariable Julio is in Rio de Janeiro to visit its famous carnival.

- Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela Art & Design Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Artículo definido Contracción de artículo El Futuro Próximo John would like to visit the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela.

- Celebrating a new year Celebrations & Important Dates Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Artículo definido Juan tells us his plans for New Year's Eve.

- Chocolate and roses Celebrations & Important Dates Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adjetivo posesivo Patricia describes us the most common presents for Saint Valentine's Day.

- Cibeles: a monument in Madrid Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adjetivo posesivo Learn about Cibeles, a famous monument in Madrid.

- Climate change Technology & Science Adjetivo Adverbio Aspecto progresivo Patricia doesn't feel happy at all about climate change.

- Coco: a lovely poodle Family & Relationships Adjetivo Adjetivo indefinido Adjetivo invariable Meet Coco, a lovely poodle.

- Colombian coffee Food & Drink Adjetivo Adjetivo posesivo Adverbio There is always a nice cup of Colombian coffee at Carlos Alberto's house!

- Colon Theatre in Buenos Aires Art & Design Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adjetivo indefinido Pedro tells us about a famous theatre building in Buenos Aires.

- Cuban rum Food & Drink Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adjetivo invariable Patricia tells us about her favourite Cuban drink.

- Cycle-ball Sports & Leisure Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adjetivo invariable Learn about cycle-ball, an exciting sport.

- Different types of wind in Spain Technology & Science Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adjetivo invariable Unleash your senses as Spain unveils a symphony of diverse winds, from the cool Mistral to the warm embrace of the Levant.

- Discovering the majesty of the ceiba tree Sports & Leisure Adjetivo Adjetivo invariable Adjetivo posesivo Discover the mighty ceiba tree.

- Dreaming Sports & Leisure Adjetivo Artículo definido Contracción de artículo Do you enjoy dreaming?

- Easter in Ecuador Celebrations & Important Dates Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adjetivo indefinido María Isabel explains how Easter is celebrated in Ecuador.

- Load more …

A2: Lower Intermediate Spanish writing exercises

- A Christmas cocktail Food & Drink Adjetivo Adjetivo indefinido Adverbio Celebrate the season in style with our special cocktail.

- A Spanish course in Bogota Language & Education Adjetivo Adjetivo indefinido Adjetivo invariable Patrick tells us about his Spanish course in Colombia.

- A creepy recipe for this Halloween Food & Drink Adjetivo Adverbio El Futuro Próximo Enjoy a terrifying Halloween recipe!

- A cruise to Puerto Rico Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Adjetivo Adjetivo invariable Adjetivo posesivo Manuel feels excited about his next cruise trip to Puerto Rico.

- A day in Las Burgas Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Adjetivo Adjetivo indefinido Adjetivo posesivo Borja tells us about a relaxing day in Las Burgas.

- A day outside Sports & Leisure Adjetivo Adjetivo indefinido Adjetivo invariable Julián tells us about his amazing weekend.

- A different look Art & Design Adjetivo indefinido Adverbio Adverbio de cantidad Carmela went to the beauty salon and tells us about her experience.

- A documentary about the Sun Film & TV Technology & Science Adjetivo Adverbio interrogativo Artículo definido Javier watched a documentary about the Sun last night.

- A ghost tour Celebrations & Important Dates Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adjetivo indefinido David has booked a ghost tour for Halloween night in Madrid.

- A horrible campsite Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Adjetivo Adjetivo indefinido Adverbio María describes us her unpleasant experience at a campsite.

- A horror film Film & TV Adjetivo Adjetivo indefinido Aspecto imperfectivo Marta watched a terrifying film yesterday.

- A job interview Employment Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adjetivo posesivo Ainhoa is ready to do her first job interview.

- A letter to Melchior Celebrations & Important Dates Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo El Presente Alberto wrote a letter to Melchior, his favourite wise man.

- A luxurious day in Marbella Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Aspecto imperfectivo El Pretérito Imperfecto El Pretérito Indefinido Aurelia tells us about her luxurious visit to a friend in Marbella.

- A memory-based challenge Sports & Leisure Adjetivo Adjetivo invariable Adjetivo posesivo Embark on an enchanting journey with Julia through the enigmatic labyrinth of memories.

- A movie marathon Film & TV Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adjetivo indefinido Carlos plans to have a movie marathon this weekend at home.

- A postcard from Madrid Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Adjetivo indefinido Adverbio Conjunción Raquel received a postcard from her best friend.

- A story of personal triumph Sports & Leisure Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adjetivo indefinido Pedro tells us his story of personal improvement after being in an accident.

- A stunning car in the newspaper Sports & Leisure Aspecto imperfectivo El Pretérito Imperfecto El Pretérito Indefinido Discover Antonio's latest passion.

- A superbike event Sports & Leisure Adjetivo Adverbio El Futuro Próximo Two friends have been to a superbike event.

- A surprise party Family & Relationships Adverbio Adverbio de cantidad Adverbio interrogativo Raquel doesn't know where her family is today.

- A tour of Buenos Aires Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Adjetivo Adverbio El Futuro Próximo Manuel tells us about his visit to Buenos Aires.

- A very healthy barbecue Food & Drink Adjetivo Adjetivo indefinido Adjetivo posesivo Discover Pedro and Maribel's recipes for their barbecue.

- A very noisy neighbour Family & Relationships Adjetivo Adjetivo invariable Adjetivo posesivo Sara has to deal with a really noisy neighbour living downstairs.

- A wedding in Las Vegas Family & Relationships Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adjetivo indefinido Discover what a wedding in Las Vegas means!

- A weekend in Sierra Nevada Monuments, Tourism & Vacations El Pretérito Indefinido Expresión idiomática con "estar" Gender of nouns in Spanish: masculine Mercedes tells us about her weekend in Sierra Nevada in the south of Spain.

- Acid rain Technology & Science Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adjetivo invariable Learn about some interesting facts about the acid rain.

- Ainhoa Arteta: a Spanish soprano Famous People Music Adjetivo Adjetivo invariable Aspecto imperfectivo Learn about Ainhoa Arteta, a famous Spanish soprano.

- Aire fresco: an Argentinian film Film & TV Adjetivo Adjetivo posesivo Adverbio Learn about the Argentinian movie that Rodrigo saw yesterday.

- An afternoon in Caracas Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adjetivo indefinido María Elena spent an exciting afternoon with her friend Gabriela in Caracas.

- An aromatherapy session Sports & Leisure Adjetivo Conjunción subordinante El Futuro Próximo Discover what an aromatherapy session is like!

- An interview with Juanes Famous People Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adjetivo indefinido Learn about Juanes' music with this interview.

- An unusual taxi ride Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Adjetivo Artículo neutro El Pretérito Imperfecto Juan tells us about his strange experience in a taxi. In this exercise you'll practise El Pretérito Imperfecto and El Pretérito Indefinido.

- Aragonese jota Music Adjetivo Adjetivo indefinido Adverbio Pilar tells us about her local dance, the Aragonese jota.

- Argentina's journey towards a zero-waste lifestyle Technology & Science Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adjetivo invariable Argentina is striving for zero waste, prioritizing reduction, reuse, and recycling for a sustainable future.

- Arguiñano and his set menu Famous People Food & Drink Adjetivo Adjetivo posesivo Adverbio Minerva loves Zarauz and Arguiñano's restaurant.

- Armed Forces Immigration & Citizenship Politics, History & Economics Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adjetivo indefinido Learn about The Spanish Armed Forces

- Art therapy in Spain Art & Design Adjetivo Adjetivo indefinido Adjetivo interrogativo y exclamativo Learn about some art therapy exercises.

- At Cartagena beach Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Adverbio Adverbio de cantidad Aspecto imperfectivo Juan went to the beach with some of his friends yesterday.

- At a barbecue Food & Drink Adjetivo Adjetivo indefinido Adjetivo interrogativo y exclamativo Grill and chill at Sandra and her friends' barbecues.

- At a karate competition Sports & Leisure Adjetivo Adjetivo indefinido Adverbio Gabriel just participated in a karate competition.

- At our deli shop Food & Drink Adjetivo Adjetivo invariable Adjetivo posesivo Are you looking for something different to eat? If so, visit Leila's deli.

- At the circus Sports & Leisure Adjetivo Adjetivo invariable Adjetivo posesivo Irene tells us about a circus afternoon with her son.

- At the dry cleaner's Family & Relationships Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adjetivo indefinido Raquel just left the dry cleaners with a lovely just-ironed shirt.

- At the florist Art & Design Adjetivo Adjetivo interrogativo y exclamativo Adjetivo posesivo Marta is at the florist to buy her sister some flowers.

- At the office gym Employment Sports & Leisure Adjetivo Adjetivo posesivo Artículo indefinido Do you have a gym in your office?

- At the restaurant Free Food & Drink Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adverbio Mónica and Raúl are at a restaurant next to the beach.

- At the shoe shop Art & Design Adjetivo Adjetivo indefinido Adjetivo invariable Raquel is at the shoe shop looking for some fancy shoes.

- At the train station Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Adjetivo Adjetivo indefinido Adjetivo invariable Join Clara and her friend Isabel who travel to Zaragoza by train every weekend.

- Aztec culture Art & Design Artículo definido Artículo indefinido El Presente Learn about the Aztec culture.

B1: Intermediate Spanish writing exercises

- 5G network Technology & Science Adjetivo Adverbio El Futuro Simple Learn about the 5G network.

- 6th of January Celebrations & Important Dates Adjetivo Artículo neutro El Futuro Simple Eduardo is thinking about the 6th of January in order to get his Christmas presents.

- A Christmas jumper Art & Design Adjetivo El Futuro Simple El Presente de Subjuntivo Marcos must wear a Christmas jumper (US: sweater) for a party, but he is not very excited about it.

- A Halloween wish Celebrations & Important Dates Adjetivo Adjetivo indefinido Adverbio Daniela tells us about her special Halloween wish.

- A Mediterranean breakfast Food & Drink Adjetivo Adverbio de cantidad Adverbio interrogativo This food company has prepared a magnificent Mediterranean breakfast for you to start your day!

- A Tinder date Family & Relationships Technology & Science Adjetivo Adverbio de duda Artículo neutro Learn about Tomás's Tinder date.

- A bumpy flight Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Adjetivo Adverbio interrogativo Adverbio relativo Rosa tells us about her bumpy flight to Costa Rica.

- A day among dolphins Family & Relationships El Futuro Simple El Presente El Presente de Subjuntivo Marisa tells us about her mother's passion: dolphins.

- A family lunch on Easter Sunday Celebrations & Important Dates Family & Relationships Adjetivo Adverbio interrogativo Conjunción Javier tells us about what lunch on Easter Sunday is like for his family.

- A gala evening Art & Design Adjetivo Adjetivo indefinido Adjetivo invariable Sara has received an invitation for a special event.

- A jungle trip Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Adjetivo Adjetivo indefinido Conjunción subordinante Andrea tells us about her ideal holiday.

- A luxurious stay in Madrid Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Adjetivo Adverbio interrogativo Conjunción Stay in a top luxurious hotel in Madrid!

- A magic show in hospital Employment Adjetivo Adverbio interrogativo Apócope Alberto is starting a new job next week in a hospital.

- A night hike Sports & Leisure Adjetivo Adverbio Adverbio de cantidad Experience the thrill of a night hike with María and Alberto.

- A photo of our grandparents Family & Relationships Adjetivo Adjetivo interrogativo y exclamativo Adjetivo invariable Two brothers show us a heartwarming snapshot of their cherished grandparents.

- A second chance Family & Relationships Adjetivo Adjetivo invariable Comparativo Manuela is asking Mateo to give their relationship a second chance.

- A trip to Majorca Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Adjetivo Adjetivo indefinido Adverbio interrogativo Discover the beautiful city of Majorca.

- A video game night Sports & Leisure Adjetivo Artículo neutro El Imperativo Learn about the benefits of playing with video games.

- A wonderful gardener Art & Design Adjetivo Adjetivo indefinido Adjetivo invariable Learn about Pedro, a high-skilled gardener.

- Acupuncture Sports & Leisure Adjetivo Adverbio Adverbio interrogativo Learn about acupuncture in Spanish.

- Adventures with friends Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Adjetivo Adverbio interrogativo Adverbio relativo Raquel loves spending time with her friends and going on trips with them.

- All Saints' Day Celebrations & Important Dates Adjetivo Adjetivo indefinido Artículo neutro Learn about how All Saints' Day is celebrated in Spain.

- As bestas by Rodrigo Sorogoyen Film & TV Adjetivo Adjetivo indefinido Adverbio interrogativo Discover As bestas, a Spanish thriller by the film director Rodrigo Sorogoyen.

- At Carlos Baute's concert Music Adjetivo Adjetivo indefinido Adverbio interrogativo María Fernanda went to a Carlos Baute's concert, a famous Venezuelan singer.

- At summer camp Employment Sports & Leisure Adjetivo Adverbio interrogativo Conjunción Maribel feels very excited about working as a group leader at a summer camp.

- At the Magic Fountain of Montjuïc Celebrations & Important Dates Adjetivo Adverbio interrogativo Apócope Ester plans to start the New Year at the Magic Fountain of Montjuïc.

- At the butcher's Food & Drink Adjetivo Adjetivo indefinido Adjetivo interrogativo y exclamativo Learn how to order some meat at the butcher's.

- At the gym Sports & Leisure Adverbio Adverbio interrogativo Conjunción Samuel wants to lose some weight and keep healthy.

- At the local gym Sports & Leisure Adjetivo indefinido Adverbio Adverbio interrogativo Pedro tells us about his workout at the local gym.

- At the pediatrician Family & Relationships Adjetivo Adverbio Adverbio interrogativo Lucia's baby is not feeling well and she is at the pediatrician to get some advice.

- At the street market Food & Drink Adjetivo Adjetivo indefinido Adjetivo invariable Learn about the most famous street market in Madrid.

- At the tourist office Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Adjetivo Adverbio Adverbio interrogativo Mónica and Ángel are at the tourist office to get some information for their day trip to San Jose.

- At the vet Family & Relationships Adjetivo Adjetivo indefinido Adverbio Rodrigo takes Max to the vet as he is not feeling well.

- B-Travel Barcelona: a tourism fair Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Adjetivo Adjetivo invariable Adverbio de duda Learn about this interesting tourism fair in Barcelona.

- Baroque in Latin America Art & Design Adjetivo Adverbio interrogativo Adverbio relativo Learn about the baroque in Latin America.

- Bartering Politics, History & Economics Technology & Science Adjetivo Artículo neutro El Condicional Simple Interested in exchanging your stuff without using money?

- Buena Vista Social Club: a Cuban band Music Adjetivo Apócope Aspecto progresivo Learn about the Buena Vista Social Club, a famous Cuban band.

- Buying a second home in Spain Politics, History & Economics Adjetivo Adverbio Adverbio interrogativo This couple feels very excited about buying a house in Spain for their retirement.

- Captain Thunder Literature, Poetry, Theatre Adjetivo El Pretérito Imperfecto El Pretérito Indefinido Ramiro tells us about Captain Thunder.

- Changing schools Language & Education Adjetivo Adjetivo invariable Conjunción María is starting at a new school.

- Cheap smart homes Technology & Science Adjetivo Adverbio Adverbio interrogativo Learn about how to set up a cheap smart home.

- Circuit of Jarama Sports & Leisure Adjetivo Adverbio Apócope Learn about Rodrigo, a high-speed motorcyclist.

- Classical music in Mexico Music Adjetivo Adverbio interrogativo Apócope Learn about classical music in Mexico.

- Climbing up and down stairs Sports & Leisure Adjetivo Adjetivo indefinido Adjetivo invariable Explore the benefits for your health and well-being by climbing the stairs.

- Coaching to improve family relationships Family & Relationships Adjetivo demostrativo El Condicional Simple El Imperativo Learn about coaching techniques to improve family relationships.

- Coffee in the morning Food & Drink Adjetivo Adverbio Adverbio interrogativo Mar really enjoys having a coffee in the morning.

- Costa del Sol in Málaga Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Adjetivo indefinido Adverbio Adverbio interrogativo Lucía has booked a holiday in Málaga.

- Courtyards in Cordoba Celebrations & Important Dates Adjetivo Adjetivo demostrativo Adjetivo indefinido Learn about this famous festival in Cordoba.

- Cuban collective memory Politics, History & Economics Adjetivo Adverbio interrogativo Apócope Immerse yourself in the vibrant tapestry of Cuban collective memory.

- Darien National Park Sports & Leisure Adjetivo Adverbio Apócope Discover Darien National Park, a beautiful nature reserve in Panama.

B2: Upper Intermediate Spanish writing exercises

- 12 self-portraits by Pablo Picasso Art & Design Adjetivo Adjetivo indefinido Adverbio Learn about Pablo Picasso's self-portraits.

- A Christmas surprise Celebrations & Important Dates Adjetivo Adverbio Adverbio de cantidad Daniela is wondering who wrote her an anonymous message.

- A Christmas tale Celebrations & Important Dates Adjetivo Adjetivo invariable Adverbio A forgotten Christmas gift sparks a heartwarming holiday story.

- A big surprise! Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Adjetivo El Presente de Subjuntivo El Pretérito Imperfecto Adela tells us about an axciting surprise she got from her boyfriend.

- A change of career Employment Language & Education Adjetivo Apócope Conjunción Discover Vanessa's career plans.

- A delayed train Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Adjetivo interrogativo y exclamativo El Condicional Simple El Futuro Perfecto Ana is furious about the fact that her train is delayed.

- A family of potters Art & Design Adjetivo Adjetivo invariable Adverbio Get into the fascinating world of a family of master potters.

- A gift woven with care Family & Relationships Adjetivo Adverbio interrogativo Adverbio relativo Clara's skilled hands knit more than just a sweater.

- A homemade costume Art & Design Celebrations & Important Dates Adjetivo Adverbio de negación Conjunción coordinante Amalia plans to make her own costume for carnival.

- A letter to Santa Celebrations & Important Dates Adjetivo Conjunción El Condicional Simple Read this letter from my nephew.

- A letter to my love Family & Relationships Adjetivo Adverbio Adverbio interrogativo Sandra wrote a romantic letter to her love.

- A lost Nazarene Celebrations & Important Dates Adverbio Adverbio de duda Adverbio interrogativo Rodrigo got lost during a celebration!

- A magic piano Music Adjetivo Adjetivo interrogativo y exclamativo Adverbio interrogativo Learn about Pablo Alborán and his excellent piano skills.

- A saeta Celebrations & Important Dates Music Adjetivo Artículo neutro El Futuro Simple Jaime tells us about his experience in Seville during Easter celebrations.

- A snow storm Technology & Science Adjetivo Apócope El Pretérito Imperfecto Have you ever experienced a big snow storm?

- A special lunch Food & Drink Adjetivo Adjetivo indefinido Adjetivo interrogativo y exclamativo Arancha enjoyed a special lunch today.

- A tourist in my own city Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Adjetivo Adverbio de duda Artículo neutro Marta tells us about the pleasure of being in an empty city during the summer.

- A true friendship Family & Relationships Adjetivo Adverbio interrogativo Apócope What does a true friendship look like?

- A very nosy parrot Family & Relationships Aspecto progresivo Conjunción El Condicional Simple Meet Beru the parrot. It's hard to have a secret conversation with him around!

- A walk along the Guayas river Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Adjetivo Adverbio Conjunción Have a fun learning jorney with this tourist leaflet about the Guayas river in Ecuador.

- A weekend without new technology Family & Relationships Technology & Science Adjetivo Adverbio de cantidad Conjunción coordinante Carlos' mum was concerned about his health and recommended him to spend a weekend away.

- An afternoon around the fire Sports & Leisure Adjetivo Aspecto progresivo Conjunción subordinante What do you think of a warm afternoon around the fire?

- An appointment with the ENT specialist Family & Relationships Adjetivo interrogativo y exclamativo Adverbio interrogativo Conjunción Carlos got an appointment with the Ear, Nose and Throat doctor to get a treatment for his anosmia.

- An inspiring extreme sports story Sports & Leisure Adjetivo Adverbio interrogativo Adverbio relativo Unleash your adrenaline with an inspiring story of extreme sports triumph.

- An oasis in the middle of the desert Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Adjetivo Adverbio interrogativo Adverbio relativo In the barren desert, a hidden oasis offers solace to weary travelers.

- An online Carnival party Celebrations & Important Dates Technology & Science Adjetivo Adjetivo indefinido Adverbio Victoria is very excited about her upcoming online Carnival party.

- An online shopping gift voucher Technology & Science Adjetivo El Condicional Simple El Futuro Simple Lorena feels very lucky today with her online shopping gift voucher.

- An undercover investigation Employment Adjetivo Adverbio interrogativo Adverbio relativo In the shadows of the drug underworld, an undercover investigation reveals the truth.

- Apology letter to a client Free Language & Education Adjetivo Conjunción Conjunción subordinante Learn how to write a formal letter of apology in Spanish.

- Are you ready to adopt an animal? Family & Relationships Conjunción subordinante El Condicional Simple El Futuro Simple Find out if you are ready to adopt an animal.

- Art therapy exercises Art & Design Adjetivo Adverbio interrogativo Adverbio relativo Learn about some art therapy exercises.

- At the hairdresser's Art & Design Adjetivo indefinido Adjetivo interrogativo y exclamativo Adverbio de duda Clara goes to the hairdresser to change her look.

- Athleisure on social media Sports & Leisure Technology & Science Adjetivo Adjetivo indefinido Adverbio Laura loves following social media athleisure accounts.

- Basque Pottery Museum Art & Design Adjetivo Adverbio interrogativo Adverbio relativo Have you ever been to the Basque Pottery Museum?

- Be my Valentine! Celebrations & Important Dates Family & Relationships Adjetivo Adverbio Adverbio interrogativo Miguel is declaring his love for Jimena in front of everyone!

- Blanca Suárez: a Spanish actress Famous People Film & TV Adjetivo Conjunción coordinante El Pretérito Perfecto Subjuntivo Learn about the famous Spanish actress Blanca Suárez

- Breakfast, the most important meal of the day Food & Drink Adjetivo Adverbio Adverbio interrogativo Discover why breakfast is such an important meal for performing well at work.

- Campervan trip Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Sports & Leisure Adjetivo Adjetivo indefinido Adverbio Jesús and Mateo love their campervan and travelling around Spain

- Campsite activities Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Adjetivo Apócope Artículo neutro Get some fresh ideas for things to do when you go camping.

- Casa Decor Madrid Art & Design Adjetivo Adjetivo indefinido Apócope Adriana plans to attend an exclusive exhibition next year.

- Casillero del Diablo Food & Drink Adjetivo El Presente de Subjuntivo El Pretérito Imperfecto Rosa and Enrique tell us about their experience with this Chilean wine.

- Changing my wardrobe Art & Design Adjetivo Adverbio Adverbio interrogativo María plans to change the clothes in her closet for the new season.

- Chupachups: the Spanish lollipop Food & Drink Adjetivo Apócope El Pretérito Imperfecto Did you know that these lollipops were a Spanish invention?

- Colombia in the world Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Adjetivo Apócope Conjunción Why is Colombia a great place to visit?

- Couchsurfing in Spain Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Adjetivo Adjetivo indefinido Adverbio interrogativo Learn about Couchsurfing, a service that connects a global community of travelers.

- DIY Art & Design El Condicional Perfecto El Futuro Perfecto El Futuro Simple Do some DIY with Marta!

- Dancing an aurresku Music Adjetivo Adverbio El Imperativo Learn about the aurresku, a famous dance from the Basque Country.

- Dream trips Sports & Leisure Adjetivo Adverbio interrogativo Adverbio relativo Have you ever experienced a dream trip?

- Driving in Lima Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Adjetivo Adverbio Adverbio de cantidad Learn about what driving looks like in Lima.

- Easter Empanadas from Chile Food & Drink Adjetivo Adverbio Adverbio de cantidad Agustín tells us about his delicious Easter empanadas from Chile.

C1: Advanced Spanish writing exercises

- 2021: the Year of the Ox Celebrations & Important Dates El Infinitivo Compuesto Jerga/ Expresión idiomática Modo subjuntivo Learn about the new Chinese year for 2021.

- A TikTok dance challenge Sports & Leisure Technology & Science Adverbio Adverbio de duda Artículo definido Celia's dance got popular in TikTok.

- A coffee shop for cats Family & Relationships Sports & Leisure Adjetivo Artículo neutro Gerundio/Spanish present participle Discover this unusual coffee shop where cats are the stars!

- A film review Film & TV Adjetivo Artículo neutro Aspecto progresivo Antonio makes us a review of a movie.

- A rock 'n' roll grandmother Family & Relationships Music Adjetivo Artículo definido Artículo neutro Sandra tells us about her unconventional grandmother, Carmen.

- A tornado Family & Relationships Adjetivo Artículo neutro Conjunción A fierce tornado struck Mar Azul, turning its tranquil shores into a tempestuous battleground.

- Alcoy and its textile industry Art & Design Adjetivo Artículo definido Artículo neutro Inés is telling her son Alberto about Alcoy's industry.

- Antonio Gaudi's architecture Art & Design Famous People Adjetivo Artículo neutro Conjunción coordinante Learn about Gaudí's architecture in Barcelona and practise relative pronouns and the passive voice.

- Benefits of art therapy Art & Design Adjetivo Artículo neutro Conjunción coordinante Have you ever heard about art therapy?

- Bilbao Book Fair Literature, Poetry, Theatre El Infinitivo Compuesto El Presente de Subjuntivo El Pretérito Imperfecto Subjuntivo Ready to visit the Bilbao Book Fair?

- Bungee Jumping Sports & Leisure El Condicional Perfecto El Condicional Simple El Futuro Perfecto Candela tells us about her first bungee jump.

- Castile comes from 'castle' Language & Education Adjetivo Artículo neutro Conjunción coordinante Learn about the etymological origin of the word 'Castile'.

- Cataract surgery Family & Relationships Artículo definido Artículo neutro Aspecto perfectivo Cecilia tells us about her upcoming cataract surgery.

- Centennial oak trees Sports & Leisure Artículo neutro Conjunción subordinante El Presente de Subjuntivo Shelter beneath the magnificent centennial oak trees.

- Charity Kings Parade Celebrations & Important Dates Artículo definido Artículo neutro Conjunción Are you a fan of The Three Wise Men?

- Chinese horoscope Technology & Science Artículo neutro Aspecto progresivo Conjunción Learn about the Chinese horoscope.

- Climbing the Gorbea Sports & Leisure Adjetivo Aspecto progresivo Conjunción Learn about this hill in the north of Spain.

- Cognitive inclusion at school Language & Education Artículo definido Artículo indefinido Artículo neutro Learn about this cognitive inclusion project.

- Combat sports: sport or violence? Sports & Leisure Adjetivo Conjunción coordinante Expressing need and obligation (deber, tener que, haber que, necesitar [que]) Do you think that combat sports are violent? Look at what Pedro thinks about them.

- Corruption Politics, History & Economics Adjetivo Aspecto progresivo El Presente Corruption in Spain is a serious problem that dates back centuries.

- Council housing challenges Art & Design Aspecto progresivo Conjunción subordinante El Condicional Simple Learn about the council housing situation in a Spanish city.

- Eating in the heights of Barcelona Food & Drink Adjetivo Adverbio interrogativo Adverbio relativo Interested in getting a high-flying meal?

- Frozen Film & TV Adjetivo Artículo neutro Conjunción Experience the magic of ice and adventure in 'Frozen'.

- Handicrafts Art & Design Adjetivo Artículo neutro Conjunción Discover what the traditional Honduran handicrafts are.

- Hatless women Politics, History & Economics Adjetivo Artículo neutro El Condicional Simple Learn about the hatless women from the twenties.

- History of Valencia FC Sports & Leisure Adjetivo Artículo neutro El Pretérito Imperfecto Learn about Valencia FC's history.

- History of ceramics in America Art & Design Adjetivo Artículo neutro El Pretérito Imperfecto Trace the evolution of American ceramics through the centuries.

- How to become an au pair Employment Language & Education Adjetivo Artículo neutro El Presente Are you looking for a host family to do some au pair work while improving a foreign language?

- I'm going everywhere with my GPS! Sports & Leisure Artículo definido Artículo neutro El Infinitivo Compuesto Pedro tells us about the GPS he just bought.

- Ice on the moon? Technology & Science Adjetivo Adverbio interrogativo Aspecto progresivo Is there or was there water on the Moon?

- Intarsia Art & Design Adjetivo Expresión idiomática con "ser" Infinitivo Learn about intarsia, a very old traditional woodwork technique.

- Is it cake? Film & TV Adjetivo Adverbio interrogativo Adverbio relativo Learn about an amazing TV show on Netflix.

- Jose Ortega y Gasset: a Spanish philosopher Famous People Language & Education Adjetivo Artículo neutro El Pretérito Imperfecto Learn about Ortega y Gasset and his philosophy.

- Last minute travelling Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Adverbio interrogativo Adverbio relativo Artículo definido Marisa is tempted to travel last minute this summer.

- Lost among cacti Family & Relationships Adjetivo Conjunción subordinante El Pretérito Imperfecto Lucía found herself adrift in a prickly sea of cacti.

- Madeira Centro hotel Art & Design Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Adjetivo Conjunción coordinante Gerundio/Spanish present participle Discover this beautiful hotel in Benidorm.

- Marmitako to keep warm Food & Drink Adjetivo Artículo neutro El Condicional Simple Blanca feels like cooking a hot tuna dish to warm herself up after a rainy day.

- Mexicans in the USA Immigration & Citizenship Adjetivo Artículo neutro Conjunción coordinante Amelia is impressed by Mexican culture and cuisine in the USA.

- Mosque-Cathedral of Cordoba Art & Design Monuments, Tourism & Vacations Conjunción Expresión idiomática con "ser" Expressing need and obligation (deber, tener que, haber que, necesitar [que]) Have you ever visited the Mosque-Cathedral of Cordoba?

- My father's self-portrait Art & Design Adverbio de cantidad Expresión idiomática con "estar" Gerundio/Spanish present participle Daniel had a lot of fun with his father's self-portrait.

- My relationship with my parents Family & Relationships Adjetivo Artículo neutro Conjunción Learn about Pablo's relationship with his parents.

- On the moon Technology & Science Adjetivo Adverbio interrogativo Adverbio relativo Learn about Clara's adventure in an unknown place.

- One day on the radio Film & TV Adjetivo Adverbio de duda Artículo neutro María is looking forward to participating in a radio session.

- Our energy bill Technology & Science Adjetivo Artículo neutro Conjunción Samuel and his wife are not happy at all with their last electricity bill.

- PISA report: Spain Language & Education Adjetivo Artículo neutro Conjunción coordinante Carlos, headmaster of a Spanish school, shares his thoughts about the latest PISA report.

- Paid to sleep! Employment Artículo neutro Conjunción coordinante El Imperativo Learn about this relaxing business.

- Putting yourself first Family & Relationships Artículo neutro El Pretérito Perfecto Subjuntivo Infinitivo Isabel is giving Maria some advice following her breakup with her boyfriend.

- Really hard January Politics, History & Economics Adjetivo Adverbio de duda Conjunción subordinante Manuel is regretting having spent so much money on Christmas.

- Sailing in Majorca Sports & Leisure Adjetivo Artículo neutro El Imperativo Sara has received an exciting proposal to sail in Majorca.

- San Isidro in Madrid Celebrations & Important Dates Adverbio de cantidad Expresión idiomática con "estar" Expresión idiomática con "ser" Learn about this popular celebration in Madrid.

In this section

- Hanukkah 2023 Menorah

- Christmas 2023 Advent Calendar

- Tips and ideas to improve your Spanish writing skills

- Spanish Glossary and Jargon Buster

Spanish Writer Freelance

65 spanish phrases to use in an essay.

If Spanish is not your first language, memorizing specific phrases can help you improve your essay-writing skills and make you sound more like a native speaker. Thus below, you will find a list of useful phrases categorized by groups to help you appear more proficient and take your essays to the next level!

Introductory Phrases

Based on my vast experience as a freelance writer , I can say that starting an essay is undoubtedly the most challenging part of essay writing. Nonetheless, many phrases have proven to help organize my thoughts and form cohesive and intriguing introductions, such as:

• “Para empezar” – To begin with

• “Al principio” – At the beginning…

• “En primer lugar” – To start…

• “Empecemos por considerar” – Let’s begin by considering/acknowledging

• “A manera de introducción” – We can start by saying…

• “Como punto de partida “ – As a starting point

• “Hoy en día” – Nowadays… Notice that these introductory phrases are not exactly the same than those you would use in a conversation. For that, I suggest reading my article about Sentence Starters in Spanish .

You can also use phrase to introduce a new topic in the text such as:

- En lo que se refiere a – Regarding to

- Respecto a – Regarding to

- En cuanto a – Regarding to

- Cuando se trata de – When it comes to

- Si pasamos a hablar de – If we go ahead to talk about

Concluding Phrases

It is also crucial that you know how to finish your essay. A good conclusion will allow you to tie all your ideas together and emphasize the key takeaways. Below, a few ways in which you can begin a concluding argument:

• “En conclusion” – In conclusion

• “En resumen/resumiendo…” – In summary

• “Como se puede ver…” – As you can see

• “Para concluir” – To conclude

• “Para finalizar” – To finish

• “Finalmente, podemos decir que…” – We can then say that…

• “ En consecuencia, podemos decir que…” – As a result, one can say that…

• “Por fin” – Finally

Transitional Phrases

Transitions phrases are crucial if you wish your essay to flow smoothly. Thus, I recommend you pay special attention to the following sentences:

• “Además” – Besides

• “Adicionalmente” – In addition…

• “Dado que…” – Given that…

• “Por lo tanto” – Therefore

• “Entonces” – Thus/So

• “Debido a…” – Hence

• “Mientras tanto” – Meanwhile

• “Por lo que” – This is why

• “Desde entonces” – Since then

Argumentative Phrases

When writing essays, it is very common for us to need to include argumentative phrases to get our message across. Hence, if you are looking for new ways to introduce an argument, below a few ideas:

• “Por otro lado…” – On the other hand…

• “En primera instancia…” – First of all

• “A diferencia de…” – As oppossed to

• “De igual forma” – More so

• “Igualmente” – The same goes for…

• “En otras palabras” – In other words

• “A pesar de que…” – Although

• “Aunque” – Even though

• “En contraste” – By contrast

• “De hecho…” – In fact…

• “Sin embargo” – Nevertheless

• “No obstante” – However

Opinion Phrases

There are many formal (and less formal ways) to express your opinions and beliefs in Spanish. Here, a few examples:

• “Considero que…” – I considerthat…

• “Mi opinión es” – It is my opinion

• “Pienso que…” – I think that…

• “Opino que” – In my opinion…

• “Afortunadamente” – Fortunately

• “ Lamentablemente” – Unfortunately

• “Me parece que…” – It seems to me that…

• “En mi opinión” – I believe that…

• “En mi experiencia” – Based on my experience

• “Como yo lo veo…” – As I see it…

• “Es mi parecer” – My pointview

General Phrases

Finally, I wanted to include a group of useful common phrases that can enrich your essay’s vocabulary:

• “En realidad” – In reality

• “Actualmente” – Today/Nowadays

• “De acuerdo a…” – According to…

• “Por ejemplo” – For example

• “Cabe recalcar que…” – It is important to note that…

• “Vale la pena resaltar que…” – It is important to highlight that…

• “No podemos ignorar que…” – We can’t ignore that…

• “Normalmente” – Usually/Normally

• “Por lo general” – In general

• “Es normal que…” – It is normal to…

• “Otro hecho importante es…” – Another relevant factor is…

• “Podría decirse que…” – One could say that…

• “Para ilustrar” – To illustrate

There you have it! A list of 60 useful phrases you can memorize to make your essays sound more professional and become more appealing to readers. However, if you are struggling and need further assistance with your essay, here you can see an Spanish essay example that can help you to structure and edit your work.

Related Posts

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

I am a freelance copywriter from Spain

Privacy overview.

How To Read And Write In Spanish (14 Essential Tips)

- Read time 11 mins

Some Spanish learners are naturally better speakers and listeners, but when it comes to reading and writing in Spanish they face challenges.

You might be able to relate. You may be feeling overwhelmed and struggling with Spanish literacy.

There are some strategies you can use to get better at these two skills.

Do you want to know these strategies?

Keep reading.

Why is reading in Spanish so important?

Reinforcing your knowledge is always critical. If you learn something once and never revisit it, you’re unlikely to remember it.

This is why reading in Spanish is so important.

Reading in Spanish is the best way to learn new Spanish idioms , how you should use the subjunctive mood , pick up vocabulary that native speakers use every day, understand past, future, conditional, imperative and present tense verbs, and take note of irregular verbs.

When you read in Spanish, you also grow accustomed to seeing the Spanish accent marks floating on top of the vowels that require them.

This is one of the tricky things to master and, even though there are rules that can help you understand it, you’ll find it easier to remember those rules when you read in Spanish.

Why is writing in Spanish so important?

Communicating in the Spanish language is not only limited to verbal communication.

You’ll find yourself sending emails to colleagues, using slang or colloquial expressions when communicating with friends, and even communicating online.

Using accent marks correctly and spelling words correctly is important for formal writing, as is using the right register for the right audience. For example, if you’re writing an email to your boss, you should avoid using colloquial expressions.

For this reason, practising how to write in Spanish is vital.

You’ll find that reading and writing in Spanish are two skills that you can master when you practice them alongside each other.

So, the more you read, the more you’ll know how to confidently spell complex words like otorrinolaringólogo .

How to read in Spanish

Let’s now look at some handy tips for learning how to read in Spanish and grow accustomed to learning more vocabulary as you do so.

1. Begin by reading English works in the Spanish language

When you already recognise a story in English, this can make it easier to follow the narrative in Spanish and remain entertained.

It’s the first secret to staying motivated when you’re finding your feet in a new language like Spanish.

Just by reading English works in the Spanish language, you’ll find yourself deducing the meaning of new verbs as your brain recalls the story that you’ve previously read.

You’ll notice that the vocabulary might make more sense when you already have the context of the story in your mind, so look at works that you have already read in English.

2. Complete comprehension tasks based on the Spanish books you read

Selecting Spanish books that have a comprehension task section at the end of the book is a great way to test what you have understood when you read in Spanish.

As you answer the questions, revisit the passages indicated in the comprehension task and try to evaluate whether you fully understand the meaning of the text.

3. Pay attention to Spanish grammar

If you’re reading a book and studying a Spanish course, now is the perfect time to assess whether you fully understood the grammatical rules of your course.

It’s also a time to test how much you understand when reading the text.

Take note of any verb conjugations that you didn’t understand and go to your Spanish notes to refresh your memory. Then go back and read the passage in the book again.

You can open your eyes to new, clarified meanings by accompanying your Spanish course with a book and vice versa: You can understand what you study in a Spanish course thanks to what you read outside of the course, so make the most of it.

4. Use a dictionary to clarify the meaning of vocabulary you don’t recognise

Not even native Spanish speakers know the meaning of every single word in the Spanish language, so don’t feel like you’ve failed if you find yourself reaching for a dictionary.

Pat yourself on the back when you learn the meaning of a new word and can begin to understand the passage more fully with it when reading in Spanish.

5. Use verb conjugation tools to help you understand irregular verb conjugations

Paying attention to Spanish grammar is a step in the right direction, now you must take part in active learning and start using your conjugation tools to remember irregular verb conjugations as much as possible.

Some verb conjugation tools are the ideal way to master irregular verbs. Wordreference.com and SpanishDict spring to mind, but there are also others.

When you see the irregular verb again, you will then recognise who the subject of the sentence is.

You’ll understand the meaning of the text and find it less difficult to understand what is happening in the passage.

6. Avoid choosing a book that is too advanced

It can be discouraging to select an advanced book such as Cien Años de Soledad by Gabriel García Márquez and find that you don’t understand anything that is happening in the book when you read in Spanish.

If you’re reading at an A2 level, books for kids might be the best option for you, and there’s nothing to be ashamed of if you’re starting at this level. We all have to begin at the beginning.

Some fairy tale stories can be a great way to begin reading in Spanish and feel like you’re making progress. In fact, Caperucita Roja ( Little Red Riding Hood ) is often taught in A2 Spanish courses to help students understand the past tense.

It’s always better to make small steps in the right direction than jump straight into the deep end, so choose books that you can understand and adjust the reading difficulty as you make progress.

7. Keep note on your novels

Keeping notes can help you become an active reader, as opposed to noticing that you don’t understand a word and continuing reading (hoping that the meaning will reveal itself).

You can also highlight words in the text that made little sense to you. Highlighting words that you don’t recognise and then doing your own research on the word can help take your reading skills to the next level.

Make note-keeping a go-to practice and become an active reader.

How to write in Spanish

Now, let’s move on to how to write well in Spanish. Here are my tips for learning how to do this.

1. Use simple vocabulary and syntax first

There’s no point in using multiple clauses when you’re just starting to write in Spanish. Not only are there some syntactic rules that you have to know, but you may also lack the vocabulary if you’re just starting to learn Spanish.

Instead, begin with basic sentences and basic vocabulary.

Start with the easiest sentences that take the present tense , such as:

Llueve mucho hoy.

La niña estudia español.

Bebo mucha agua.

As you can see, these sentences all use the present tense and don’t have more than one clause.

When you get more confident, you can begin to add more vocabulary and conjunctions, such as:

Llueve mucho hoy, pero tengo un paraguas.

La niña estudia español, aunque no le gusta.

Bebo mucha agua, sin embargo, no como comida sana.

2. Learn about formal and informal writing

If you’re writing an email or letter, one of the crucial things your Spanish teacher will mention to you is “formal or informal” register.

When you write to people you know and love, use querido or querida to say (dear…). When you write to people you don’t know, or to your colleagues, use estimado or estimada . Note, the difference between querido / a and estimado / a is that querido is used for a male addressee and querida is used for a female addressee.

It’s also important to use the Spanish pronoun tú when addressing loved ones and friends, but usted when addressing people who you don’t know.

Finally, when you close your email or letter, only use besos or abrazos (hugs and kisses) when writing to a friend or family member, but atentamente (sincerely) when speaking to a client or a colleague you don’t know or haven’t met.

3. Study how to structure your writing

When you write in Spanish you need to structure your emails and letters well to convey your meaning, so try to study how to structure your writing.

Here’s a tip: Structure your emails into four main parts.

- First, you start with the greeting

- Then, you explain your motive for writing the email or letter

- Next, you give more detail in the body of the email or letter

- Finally, you close the email or letter

Even though the content of your writing may vary, try to follow this order to write your emails and letters.

4. Practice informal language and rules of texting and informal chat

If you have sent text messages in English, you will probably know that there are many rules to get accustomed to.

Not only can you omit letters from words, but you can also use abbreviations to shorten words.

In Spanish, this is the same.

Instead of porque , you can simply write pq . Instead of no pasa nada , you can write npn .

You’ll also notice that you can use numbers or symbols to shorten words. For example, instead of writing chicos y chicas , or niños y niñas , you can write chic @s or nin @s, where the @ symbol represents the a and o of niños and niñas .

Pretty cool, right? 😊

Just to get you started, here are seven key Spanish slang acronyms used for texting:

- tqm. Te quiero mucho

- ntp. No te preocupes

- mdi. Me da igual

- tqi. Tengo que irme

- cdt. Cuídate.

- fds. Fin de semana

- npn. No pasa nada

5. Learn the accent marks and how to type them

Remember that vowels in Spanish sometimes have an acute accent mark above them when you write in Spanish.

The acute mark helps you understand how to pronounce a word and how to distinguish two words that are otherwise spelled the same - like tu and tú

We use the diéresis mark to indicate that you should pronounce the letters u and i in particular circumstances, like in the words bilingüe and vergüenza , and we use the virgulilla to distinguish between the letters ene (letter n ) and enye (letter ñ ).

I have a whole guide on Spanish accent marks so check it out to learn how to use them.

6. Exclamation and question marks: Don’t forget about them

Exclamation and question marks are orthographically different to the English equivalent.

In Spanish, we have an upside-down exclamation mark at the beginning of the sentence and a closing right side up exclamation mark at the end of the sentence.

This is also true for question marks.

It’s something that you’ll have to get used to when you write in Spanish, but you’ll get it with practice.

7. Learn the order of sentence structures in Spanish

Do you know the order of sentence structures in Spanish?

Although it sometimes uses the same structure as English, which is subject, verb, object, (for instance Louisa está cocinando una receta ) this can change.

It’s possible to omit the pronoun or subject of the sentence altogether in Spanish, meaning that the subject doesn’t always come first in the sentence structure. The main reason for this is that verb conjugations include the subject itself.

Another thing to watch out for when writing in Spanish is that nouns come before Spanish adjectives .

In English you would write “the black gloves”, in Spanish this becomes los guantes negros.

Keep practising to become an excellent reader and writer in Spanish

Learning how to read and write in Spanish might seem challenging at first, but by following the tips in this article you’ll know exactly what to watch out for.

Avoid resorting to translation apps for reading.

Frequent practice is the best way to get better at reading and writing in Spanish. Try journaling in Spanish, writing letters, reading books and reading newspaper articles to improve.

Have fun reading and writing in Spanish.

Which else would you recommend to someone learning to read and write in Spanish?

Add your advice to the comments below!

🎓 Cite article

Learning Spanish ?

Spanish Resources:

Let me help you learn spanish join the guild:.

Donovan Nagel - B. Th, MA AppLing

- Affiliate Disclaimer

- Privacy Policy

- About The Mezzofanti Guild

- About Donovan Nagel

- Essential Language Tools

- Language Calculator

SOCIAL MEDIA

Current mission.

Let Me Help You Learn Spanish

- Get my exclusive Spanish content delivered straight to your inbox.

- Learn about the best Spanish language resources that I've personally test-driven.

- Get insider tips for learning Spanish.

Don’t fill this out if you're human:

No spam. Ever.

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

52 Spanish Writing Prompts to Level Up Your Language Skills

Here’s a method that’s quite effective for helping you build confidence in your Spanish , no matter your level.

You only need two items: pencil and paper.

That’s right, we’re going to get you that much-needed writing practice !

With Spanish writing prompts, you can strengthen your grasp on Spanish verb conjugations , grammatical structures , vocabulary and more.

Ready your writing materials, buckle up and let’s get started.

Spanish Writing Prompts for Beginners

1. daily routine (with a twist), 2. dream vacation, 3. mysterious object, 4. unlikely friends, 5. family portrait, 6. time capsule, 7. unexpected gift, 8. language exchange, 9. lost in the city, 10. the weather today, 11. my favorite season, 12. a visit to the zoo, 13. at the restaurant, 14. a day without technology, 15. a mysterious letter, 16. a visit to the doctor, 17. my favorite book or movie, 18. an unexpected friendship, 19. my ideal home, 20. the magical object, spanish writing prompts for intermediate learners, 21. postcard from paradise, 22. dear diary, 24. never have i ever, 25. lost in translation, 26. haunted house, 27. future professions, 28. unexpected encounter, 29. secret diary, 30. culinary adventure, 31. the mysterious package, 32. childhood memories, 33. social media: yay or nay, 34. the art of persuasion, 35. the time-traveling journal, spanish writing prompts for advanced learners, 36. ideal friend, 37. alternate timeline, 38. eco-friendly habits, 39. artistic inspiration, 40. tangled tales, 41. culinary fusion, 42. lost and found in translation, 43. untranslatable beauty, 44. cultural dilemma, 45. the mind’s canvas, 46. echoes of history, 47. nature’s poetry, 48. evolving traditions, 49. the four-day workweek, 50. cultural collage, 51. ephemeral moments, 52. language odyssey, tips to practice spanish by writing for beginner, intermediate and advanced learners, intermediate, and one more thing….

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Focus on: Present simple tense

You’ve probably had to write about your daily routine at some point in Spanish class. This prompt is great because it forces you to practice present simple verbs, which are used to talk about repeated or habitual actions. But writing about your morning coffee and shower routine can get a little dry.

So, for this writing prompt, try to write about a daily routine from someone else’s point of view. Pretend you’re someone else—a celebrity, a farm animal, a person from the future, an alien—and write about “your” daily routine. Not only is this a fun exercise in creativity, it also allows you to incorporate new vocabulary.

Sample: Soy un gato. Cada mañana cazo ratones en el jardín. Luego los llevo a la mesa y se los doy a mi dueño humano. (I’m a cat. Every morning, I hunt mice in the garden. Then, I bring them to the table and give them to my human owner.)

Keep practicing: Instead of writing from a first-person point of view, write as though you’re reporting on someone’s daily routine. This will allow you to practice third-person verb conjugations. Since in Spanish, first- and third-person conjugations are often quite different in the present simple, it’s worth your time to practice them both.

Focus on: Future tense

You’ve been working hard on your Spanish studies , so you’ve definitely earned that dream vacation—and this fun writing prompt!