- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Criminal Justice

IResearchNet

Academic Writing Services

Future trends in criminal profiling and behavioral analysis.

This article explores the evolving landscape of criminal profiling and behavioral analysis within the context of the United States criminal justice system. Commencing with a historical overview and significance of these methodologies, the current state of traditional techniques and their integration with advanced technologies, particularly artificial intelligence and machine learning, is examined. Through the lens of case studies, the successes, challenges, and limitations of contemporary practices are delineated. The subsequent section forecasts future trends in criminal profiling, emphasizing the burgeoning role of neuroscientific approaches, big data analytics, and the consideration of cultural and societal factors. Nevertheless, amidst the optimism surrounding these innovations, the article critically examines emerging challenges, including ethical concerns, reliability and validity issues, and legal implications. The concluding section consolidates key insights, summarizing the current state of criminal profiling, forecasting its future trajectory, and underscoring the imperative for a balanced approach that incorporates scientific advancements while safeguarding ethical and legal standards. Overall, this comprehensive exploration provides a nuanced understanding of the dynamic field of criminal profiling and behavioral analysis, shedding light on both its promises and potential pitfalls.

Introduction

Criminal profiling and behavioral analysis represent crucial facets of contemporary investigative methodologies within the criminal justice system. In understanding the complexities of criminal behavior, profiling endeavors to create comprehensive profiles of potential offenders, while behavioral analysis seeks to decipher behavioral patterns indicative of criminal activity. This article delves into these practices, providing a nuanced exploration of their historical roots and contemporary significance.

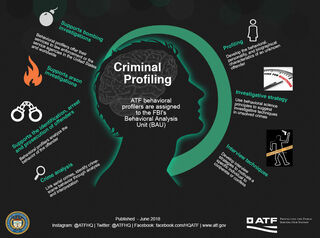

Criminal profiling involves the systematic analysis of crime scene evidence, witness statements, and other pertinent information to construct a behavioral profile of potential offenders. On the other hand, behavioral analysis delves into the study of actions, reactions, and behavioral patterns exhibited by individuals in a criminal context. Together, these methodologies contribute to a multidimensional understanding of criminal behavior, aiding law enforcement agencies in their investigative pursuits.

The roots of criminal profiling can be traced back to the early 20th century, with pioneers like Dr. James A. Brussel, whose work in the 1950s laid the foundation for psychological profiling. Over the decades, profiling techniques evolved, influenced by advancements in psychology, criminology, and forensic science. Behavioral analysis, as a distinct discipline, gained prominence in the latter half of the 20th century, propelled by the work of notable figures such as John E. Douglas and Robert Ressler. The historical trajectory of these techniques illuminates the dynamic nature of their development and application in criminal investigations.

Criminal profiling serves as a crucial tool for law enforcement agencies in narrowing down potential suspects, prioritizing leads, and allocating resources effectively. By deciphering behavioral clues, investigators can develop targeted strategies to apprehend perpetrators, ultimately enhancing the efficiency of criminal investigations.

The successes of criminal profiling are evident in numerous high-profile cases where accurate profiles contributed to the identification and apprehension of offenders. Notable examples include the capture of the “Unabomber” Ted Kaczynski and the profiling efforts in the investigation of the D.C. Sniper attacks. These successes underscore the tangible impact of profiling on solving complex criminal cases and achieving justice.

Current State of Criminal Profiling and Behavioral Analysis

In the contemporary landscape of criminal justice, the practice of criminal profiling and behavioral analysis has evolved to incorporate a diverse array of methods, blending traditional techniques with cutting-edge technologies to enhance investigative precision.

Traditional psychological profiling involves the analysis of offender behavior through the lens of psychology, considering factors such as personality traits, motivations, and potential triggers. Psychologists and criminal profilers leverage their expertise to create profiles that assist investigators in understanding the mindset of the perpetrator.

Behavioral analysis encompasses the systematic examination of behavioral patterns exhibited by criminals. This approach involves studying crime scenes, victimology, and offender modus operandi to discern recurring behavioral traits. The aim is to construct a behavioral profile that aids investigators in anticipating future actions and narrowing down the pool of potential suspects.

In the contemporary era, the integration of advanced data analytics has become pivotal in criminal profiling. Law enforcement agencies leverage vast datasets to identify patterns, trends, and correlations that may elude conventional investigative methods. The analysis of large datasets facilitates a more data-driven and comprehensive understanding of criminal behavior.

The advent of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) has revolutionized criminal profiling. These technologies can process vast amounts of data at unprecedented speeds, enabling the identification of subtle patterns and associations. AI and ML algorithms are increasingly employed to augment traditional profiling efforts, offering a more dynamic and adaptable approach to behavioral analysis.

Numerous case studies illustrate the efficacy of criminal profiling in solving complex crimes. The case of the “BTK Killer” Dennis Rader is a notable example where profiling played a pivotal role in his eventual apprehension. Additionally, the Green River Killer investigation showcased how behavioral analysis contributed to identifying and capturing the serial killer Gary Ridgway.

While advancements in criminal profiling are significant, challenges persist. Issues such as the potential for cognitive biases in profiling, the over-reliance on technology without human intuition, and the need for standardized practices pose ongoing challenges. Striking a balance between technological innovation and established investigative methods remains a critical consideration in the current state of criminal profiling.

Emerging Trends and Innovations

As criminal profiling and behavioral analysis continue to evolve, emerging trends and innovations are shaping the future of these investigative methodologies. The integration of neuroscientific approaches, the utilization of big data and predictive analytics, and the consideration of cultural and societal factors mark key areas of advancement in the field.

A paradigm shift is underway with the integration of neuroscience into criminal profiling. Researchers and investigators are exploring the neural underpinnings of criminal behavior, aiming to identify neurological markers associated with specific criminal tendencies. This interdisciplinary approach seeks to deepen our understanding of the biological factors influencing criminal actions.

The advent of advanced brain imaging technologies, such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and electroencephalography (EEG), offers unprecedented insights into the workings of the human brain. These technologies hold the potential to reveal patterns of brain activity associated with criminal intent or predispositions. The exploration of brain imaging in profiling opens new avenues for understanding and predicting criminal behavior.

The era of big data has transformed criminal profiling by providing access to extensive datasets for analysis. Predictive analytics, powered by machine learning algorithms, sift through massive amounts of data to identify patterns, correlations, and anomalies. This data-driven approach enables investigators to anticipate criminal behavior, prioritize leads, and allocate resources more efficiently.

While the use of big data and predictive analytics offers unprecedented potential, ethical considerations and privacy concerns come to the forefront. Striking a balance between the benefits of advanced analytics and the protection of individual privacy is a critical challenge. Ensuring transparency, informed consent, and ethical data handling practices is imperative to navigate the ethical landscape of predictive profiling.

Recognizing the influence of cultural factors on behavior, contemporary profiling approaches increasingly consider cultural nuances. Behavioral analysts take into account cultural backgrounds, societal norms, and contextual elements to construct more accurate and culturally sensitive profiles. This shift acknowledges the diversity of human behavior and emphasizes the importance of a culturally informed approach to profiling.

Rapid societal changes, including advancements in technology, shifts in social dynamics, and globalization, have profound implications for criminal profiling. The evolution of online spaces, for example, has given rise to new forms of criminal activity. Profilers must adapt to these changes, understanding their impact on criminal behavior and adjusting methodologies accordingly.

The integration of neuroscientific approaches, big data analytics, and a nuanced consideration of cultural and societal factors represents a transformative phase in the evolution of criminal profiling and behavioral analysis. These emerging trends hold the promise of enhancing the accuracy and efficiency of investigative processes while presenting new challenges that demand careful consideration and ethical deliberation.

Challenges and Criticisms in Future Trends

As the landscape of criminal profiling and behavioral analysis embraces future trends and innovations, a concomitant set of challenges and criticisms emerges. The ethical, scientific, and legal dimensions of these advancements raise important considerations that demand careful scrutiny.

The integration of advanced technologies, particularly those involving big data and neuroscientific approaches, raises profound privacy concerns. The collection and analysis of extensive personal data, including neurological information, demand rigorous safeguards to protect individual privacy rights. Striking a balance between the investigatory benefits of technology and the preservation of civil liberties becomes a paramount ethical challenge.

The vast amount of data collected for profiling purposes carries the inherent risk of misuse. Concerns arise regarding the unauthorized access, manipulation, or misinterpretation of profiling data, leading to false accusations or unwarranted infringements on individual rights. Establishing robust protocols for data access, storage, and disposal is essential to mitigate the risk of misuse.

Despite the promise of emerging trends, skepticism persists regarding the scientific rigor of neuroscientific and predictive profiling approaches. Critics question the reliability and validity of findings derived from these methodologies, emphasizing the need for transparency in research methodologies and the validation of results through rigorous scientific scrutiny. Addressing these concerns is crucial for establishing the credibility of evolving profiling techniques.

The absence of standardized validation procedures for emerging profiling methods poses a significant challenge. Establishing universally accepted benchmarks for the validation of neuroscientific findings and predictive analytics models is imperative. Without standardized procedures, the reliability and generalizability of profiling outcomes may be compromised, hindering the acceptance of these innovations within the scientific and legal communities.

The admissibility of profiling evidence in court proceedings raises intricate legal questions. Courts must grapple with the reliability and relevance of profiling data, weighing its probative value against potential prejudicial effects. Establishing legal standards for the admission of profiling evidence necessitates a nuanced understanding of the strengths and limitations of emerging profiling methodologies.

The integration of advanced technologies in profiling requires a delicate balance between leveraging technological advancements and upholding legal rights. Ensuring due process, protecting against unwarranted intrusions, and safeguarding the rights of the accused are paramount considerations. Legal frameworks must evolve to accommodate technological innovations while maintaining a commitment to justice and individual rights.

In navigating the future trends of criminal profiling and behavioral analysis, addressing these ethical, reliability, and legal challenges is imperative. The responsible development and application of profiling techniques require a multidisciplinary approach that encompasses the perspectives of ethics, science, and law to ensure that the pursuit of justice remains consonant with societal values and individual rights.

In summarizing the intricate landscape of criminal profiling and behavioral analysis, this exploration has illuminated both the current state and promising future trends in investigative methodologies.

The current state of criminal profiling and behavioral analysis reflects a dynamic fusion of traditional methods and cutting-edge technologies. From psychological profiling to the integration of artificial intelligence, the field has witnessed a transformative evolution. Emerging trends, including neuroscientific approaches and big data analytics, hold the promise of unprecedented insights into criminal behavior. However, a nuanced understanding of these trends necessitates acknowledging the challenges inherent in their application.

Amidst the excitement of technological advancements, it is paramount to underscore the critical importance of maintaining vigilance regarding ethical and legal considerations. Privacy issues, potential misuse of data, and the need for standardized validation procedures demand ongoing scrutiny. Balancing the quest for justice with the protection of individual rights is essential for the responsible evolution of criminal profiling.

The future of criminal profiling holds the promise of continued innovation and refinement. As neuroscientific approaches mature, and predictive analytics become more sophisticated, the field is likely to witness a paradigm shift in understanding and predicting criminal behavior. The integration of technologies and methodologies will likely become more seamless, providing investigators with a more comprehensive toolkit for solving complex cases.

The evolving nature of criminal profiling necessitates a collaborative approach. The intersection of psychology, neuroscience, data science, and law enforcement expertise underscores the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration. Researchers, law enforcement agencies, and legal experts must work in tandem to address the challenges posed by emerging trends, ensuring that advancements in profiling are grounded in robust science and aligned with ethical and legal standards.

As we stand on the precipice of a new era in criminal profiling, the lessons gleaned from the past and the challenges identified in the present provide a roadmap for the responsible and ethical evolution of these crucial investigative methodologies. By embracing innovation, staying attuned to ethical considerations, and fostering collaboration across disciplines, the field of criminal profiling is poised to make substantial contributions to the pursuit of justice in the years to come.

References:

- Blando, J. A., & Seager, P. B. (2017). A Comparative Study of Offender Profiling Efficacy. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 32(4), 291-303.

- Canter, D. V. (1995). Criminal Shadows: Inside the Mind of the Serial Killer. HarperCollins.

- Canter, D. V., & Youngs, D. (2009). Applied Psychology for Criminal Professionals. Routledge.

- Douglas, J. E., & Olshaker, M. (1995). Mindhunter: Inside the FBI’s Elite Serial Crime Unit. Scribner.

- Farley, B. (2013). Death from a Distance and the Birth of a Humane Universe: Human Evolution, Behavior, History, and Your Future. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Garrido, V. (2017). Criminal Profiling and Criminal Investigative Analysis: Emerging Research. IGI Global.

- Hare, R. D. (1999). Without Conscience: The Disturbing World of the Psychopaths Among Us. Guilford Press.

- Holmes, R. M., & Holmes, S. T. (2009). Profiling Violent Crimes: An Investigative Tool. Sage Publications.

- Kocsis, R. N. (2006). Criminal Profiling: Principles and Practice. Humana Press.

- Meloy, J. R. (2000). Violent Attachments. Jason Aronson.

- Michaud, S. G., & Hazelwood, R. R. (2005). The Evil That Men Do. St. Martin’s Paperbacks.

- Moriarty, L. J., & Scharff, D. P. (2018). Criminal Profiling: A Guide to an Effective Behavioral Analysis. CRC Press.

- Nunn, M. L., & Hogg, R. (2018). The Use of Geographic Profiling in Crime Analysis. In Handbook of Research Methods and Applications in Spatial Planning (pp. 387-414). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- O’Toole, M. E. (2011). Dangerous Instincts: How Gut Feelings Betray Us. Plume.

- Pinizzotto, A. J., Davis, E. F., & Miller, C. E. (2006). Violent Encounters: Felonious Assaults on America’s Law Enforcement Officers. FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin.

- Ressler, R. K., & Shachtman, T. (1992). Whoever Fights Monsters: My Twenty Years Tracking Serial Killers for the FBI. St. Martin’s Press.

- Salfati, C. G., & Canter, D. V. (1999). Criminal Shadows: Mapping the Minds of Serial Killers. Prentice Hall.

- Snook, B., Cullen, R. M., Bennell, C., Taylor, P. J., & Gendreau, P. (2008). The Criminal Profiling Illusion: What’s Behind the Smoke and Mirrors? Criminal Justice and Behavior, 35(10), 1257-1276.

- Turvey, B. E. (2012). Criminal Profiling: An Introduction to Behavioral Evidence Analysis. Academic Press.

- Winerman, L. (2004). The Real World of Criminal Profiling. Monitor on Psychology, 35(9), 48.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Psychiatr Psychol Law

- v.28(5); 2021

Reframing criminal profiling: a guide for integrated practice

Wayne petherick.

a Criminology Department, Faculty of Society and Design, Bond University, Gold Coast, QLD, Australia

Nathan Brooks

b School of Health, Medical and Applied Sciences, Central Queensland University, Townsville, QLD, Australia

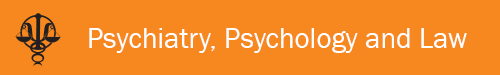

Profiling aims to identify the major personality and behavioural characteristics of offenders from their interactions in the crime. The discipline has undergone numerous changes and advances since its first modern use by the psychological/psychiatric community. The current paper reviews the different approaches to criminal profiling, exploring the reasoning and justification utilised across profiling practices. Profiling aims to assist criminal investigators; however, the variance in profiling approaches has contributed to inconsistency across the field, bringing the utility of profiling into question. To address the current areas of practice deficit in criminal profiling, a framework is proposed to promote integrated practice. The CRIME approach provides a framework (consisting of crime scene evaluations, relevancy of research, investigative or clinical opinions, methods of investigation, and evaluation) to promote structure and uniformity in profile development, aiming to assist in the reliability of the practice by providing an integrative framework for developing profiles.

In its most basic form, criminal profiling (also known as offender profiling and behavioural profiling, among others) is an investigative tool to discern offender characteristics from behaviour. This base understanding is common to most, if not all, approaches to profiling, with the main difference between practices being the reasoning and decision-making processes used to arrive at the final profile (Petherick, 2014a , 2014b ). Despite the level of scientific reasoning being notably different across the approaches, there has been little attempt to understand what this reasoning is and how it impacts on profile content. Profiling has been subject to discrepancies across practice, with a dearth of processes or principles to promote integrated practice. There have, however, been many attempts to understand more advanced aspects of profiling such as the accuracy of one group over another (Kocsis et al., 2000 ; Pinizzotto & Finkel, 1990 ), or the assistance offered by profilers to end consumers (Cole & Brown, 2011 ; Copson, 1995 ), mental health professional’s attitudes to profiling (Torres et al., 2006 ) and the operational utility of offender profiling (Gekoski & Gray, 2011 ).

Criminal profiling details the characteristics of the likely perpetrator of a given crime. Far from having an abstract relationship to criminal profiling, logic is pivotal to constructing rational and robust arguments about offender characteristics, not only in the profile itself but also in the communication of the elements of the profile to consumers. Indeed, devoid of any logical process, conclusions about the offender remain nothing more than unfounded assumption or ill-informed guesswork. The type of logic reasoning employed by the profiler is the most fundamental difference between approaches, and it is critical to consider the different types of reasoning employed across profiling practices. Logic, the process of argumentation, is defined by Farber ( 1942 , p. 41) as ‘a unified discipline which investigates the structure and validity of ordered knowledge’. Further, according to Battacharyya ( 1958 , p. 326):

Logic is usually defined as the science of valid thought. But as thought may mean either the act of thinking of the object of valid thought, we get two definitions of logic: logic as the science (1) of the act of valid thinking, or (2) of the objects of valid thinking.

Stock ( 2004 , p. 8) adopts a different approach:

Logic may be declared to be both the science and the art of thinking. It is the art of thinking in the same sense that grammar is the art of speaking. Grammar is not in itself the right use of words, but a knowledge of it enables men to use words correctly. In the same way a knowledge of logic enables men to think correctly or at least to avoid incorrect thoughts. As an art, logic may be called the navigation of the sea of thought.

It is the purpose of logic to analyse the methods by which valid judgements are obtained in any science or discourse, which is met by the formulation of general laws dictating the validity of judgements (Farber, 1942 ). More than simply providing a theoretical framework for structuring arguments, the basic principles of logic allow for a more rigorous formulation and testing of any argument. A better understanding of this theoretical framework provides a better understanding of the processes employed by the profiler, as well as the discipline itself. Additionally, the difference in the ways that profiles are argued is of great practical importance (Goldsworthy, 2001 , p. 30):

One important factor that should be considered is how acceptable the method of profiling is to those who will be using the profile. . . . Like any product, the profile must be end-user friendly. Few law enforcement personnel have qualifications in psychology or related disciplines, and it is this very fact that can make investigators dubious as to how conclusions presented in the profile were reached. For instance, a claim that a particular type of serial murderer will be 40 years old, white and a blue collar worker will be treated with derision by investigators unless it can be shown how that conclusion was reached, and further that the conclusion is likely to be true.

Goldsworthy argues two key points: first, that logic and reasoning should be employed in the construction of the profile, and, second, that the logic and reasoning employed be clearly elucidated throughout. While it should stand to reason that logic and reasoning should be used in profiling, we use the term in a more formal sense to move the process away from such idiosyncrasies as ‘intuition’ or ‘common sense’.

There are primarily three types of logic used in developing profiles: induction, abduction and deduction. Rather than representing different types of logic, these are best thought of as different points along the logical continuum, beginning with various hypotheses about what may have occurred or that may be true (induction), and through the scientific method we falsify each conclusion until we are left with the best possible explanation (abduction) or only one that is based on universal laws or principles and cannot be falsified (deduction). Sometimes, because of the nature of human behaviour, evidence dynamics or active attempts to thwart the investigation (referred to as staging, among others), we are left with the best explanation for the evidence we are observing – that is, abduction.

An inductive argument is where the conclusion is likely or a matter of probability based on supporting premises, such as physical evidence or research. While a good inductive argument provides strong support for the conclusion, the argument is still not infallible. For example, in research on behavioural consistency, Bateman and Salfati ( 2007 ) found that hiding the body occurred 67.8% of the time, and that moving the body after the homicide occurred in 61.1% of the time. While cited as high-frequency behaviours, these results suggest that each will only be found approximately two thirds of the time. As a result, investigators using a profile that reports such statistical inferences may equate probability with certainty. However, these behaviours occur in some cases and not others, raising an issue with both the utility of this information and in determining where offending behaviour is consistent and inconsistent with research. This may be especially true in cases where the level of certainty is communicated in a vague or general way, such as ‘most of the time the body will be hidden’. While technically true, this argument does not communicate the exact level of certainty.

Induction proceeds from a specific set of observations to a generalisation known as a premise, and the premise is a working assumption (Thornton, 1997 ). From observations in each case, comparisons are made to determine the level of similarity to past cases sharing similar features. These similarities provide generalisations that may then be offered as a conclusion in the current case. For example, a woman is found murdered, and a generalised conclusion is reached that the suspect is likely to be male, due to male offenders perpetrating between 85–90% of homicides (Federal Bureau of Investigation [FBI], 2002 ; Mouzos, 2005 ). The central premise in induction is similarity, where analysis of unlawful activity reveals that criminal activity often has common features (Navarro & Schafer, 2003 ). The application of inductive logic where the similarity is drawn from research on criminal behavioural patterns can be appreciated through the following (Kocsis, 2001 , p. 32):

To use this model to produce a psychological profile, behaviours from any of the [behaviour] patterns are compared and matched with those of the unsolved case. Once a behaviour pattern has been matched with the unsolved case it can be cross referenced with offender characteristics.

Abduction is a style of reasoning that could be summed up as reasoning to the best explanation (Davis et al., 2018 ). That is, the evidence in a case is more indicative of a single hypothesis from a number of possible hypotheses, though not inclusive of one to the exclusion of all others. According to Niiniluoto ( 1999 ) this type of reasoning has been the staple heuristic method of classical detective stories, and ‘the logic of the “deductions” of Sherlock Holmes is typically abductive’ (p. S441).

Deduction relies on induction, where hypotheses are drawn based on case similarities and are then tested against the evidence in the current case. Offender characteristics are arrived at through a systematic study of the patterns and themes present in the physical and behavioural evidence, where if the premise is true, the conclusion must also be true (Bevel & Gardner, 2008 ). Neblett ( 1985 , p. 114) goes further, stating that ‘ if the conclusion is false, then at least one of the premises must be false ’. For this reason, when employing a deductive approach, it is incumbent on the profiler to establish the validity of each and every premise before drawing conclusions from them.

Because a deductive argument is structured so that the conclusion is implicitly contained within the premise unless the reasoning is invalid, the conclusion will follow as a matter of course. Put another way, a deductive argument is designed to go from truth to truth. A deductive argument will therefore be valid if (Alexandra et al., 2002 , p. 65):

- It is not logically possible for the conclusions to be false if the premises are true.

- The conclusions must be true, if the premises are true.

- It would be contradictory to assert the premises yet deny the conclusions.

In profiling, deduction relies upon the scientific method which is a ‘reasoned step by step procedure involving observations and experimentation in problem solving’ (Bevel, 2001 , p. 154). Induction, abduction and deduction relying on the scientific method go hand-in-hand in criminal profiling: theories are developed based on research and experience (induction), which are then examined in light of the current case to determine which may or may not be true given the available evidence (abduction), and attempts are then made to falsify those that remain through hypothesis testing and revision (the scientific method that in ideal scenarios would lead to deduction). Only when theories have withstood this process of falsification can they be considered complete, and that a truth has been determined.

While there is no conclusive data on the commonality and occurrences of profiling practices, it would make reasoned sense to suggest that induction is the most common, given that many approaches rely on statistics or case experience in developing the final profile. Furthermore, induction is the foundation for both abduction and deduction. Owing to the nature of crime scenes and criminal behaviour and the lack of universal principle in human behaviour overall, deduction would be considered the least common type of reasoning, making abduction second by default. Although deduction is concerned with absolutes, abduction centres on probable reasoning derived through hypothesis testing. Hence, in abductive reasoning, conclusions are reached without the reliance on a definitive cause, instead determined based on the likelihood, feasibility and practicality of a given hypothesis. According to Niiniluoto ( 1999 ), in consideration of Pierce’s ( 1898 ) position on an abductive argument, the following is concluded (p. S439):

- The surprising fact C is observed.

- But if A were true, C would be a matter of course.

- Hence, there is reason to suspect that A is true.

The use of abductive reasoning is common practice in the clinical process of differential diagnosis, along with providing the underpinnings for crime assessment and profile development (Davis et al., 2018 ; Rainbow & Gregory, 2011 ). As Davis et al. ( 2018 ) observed, ‘profilers should take time to argue against their opinions and consider alternate hypotheses (p. 187–206). Consequently, the current review intends to examine the reasoning and decision making employed across offender profiling. The major profiling practices are discussed, and the utility of these approaches explored. As noted by Fox and Farrington ( 2018 ), ‘there appears to be substantial variation in what is considered to be OP [offender profiling], who is conducting it, the methodology and approach that is used, the findings that are achieved, as well as where and how the results are presented’ (p. 1248). The significant differences amongst approaches to offender profiling, along with widespread disputes between practitioners, have greatly impeded the field (Fox et al., 2020 ). These limitations have caused scepticism about the investigative utility of profiling, along with the scientific efficacy of the practice (Fox et al., 2020 ). For offender profiling to have scientific validity and more widespread recognition in investigations and admissibility in court, a uniformed approach to practise remains essential (Fox & Farrington, 2018 ; Freckelton, 2008 ). The current review contends that for profiling to be recognised as a scientific and evidence-based tool, homogeny in practice must be achieved, best viewed through an integrative approach to offender profiling.

Profiling approaches

While there is considerable overlap between practitioners and how they approach the development of a profile, there are also significant differences. Whether these constitute enough to be considered different methodologies is currently a subject of debate, with some suggesting that differences are more about emphasis on various parts of the process (Davis et al., 2018 ).

Criminal investigative analysis

Owing to its depiction in film and television, perhaps the best known profiling approach would be that developed by the FBI. Criminal investigative analysis, or CIA, is inductive and abductive with its roots in early law enforcement attempts to understand patterns of criminal behaviour. Early CIA thinking allocated offenders to one of two types: The organised asocial and the disorganised nonsocial, with these terms first appearing in The Lust Murderer in 1980 (see Hazelwood & Douglas, 1980 ). Between 1979 and 1983, FBI agents interviewed offenders in federal custody (see Burgess & Ressler, 1985 ) to formalise this taxonomy and determine whether there were consistent features across offences that may be useful in classifying future offenders (Petherick, 2014a ). At these early stages, the FBI method employed this organised/disorganised typology as a decision process model, which classifies offenders by virtue of the level of sophistication, planning and competence evident in the crime scene. According to the study’s authors, ‘the agents involved in profiling were able to classify murders as either organised or disorganised in the commission of their crimes ’ further noting that ‘ because this method of identifying offenders was based largely on a combination of experience and intuition, it had its failures as well as its successes’ (Burgess & Ressler, 1985 , p. 3). Indeed, the study’s two quantitative objectives were to first identify whether there are crime scene differences between organised and disorganised murderers and second to identify variables that may be useful in profiling sexual murderers for which organised and disorganised murderers differ. However, Douglas et al. ( 1986 ), acknowledged that profile development did not solely rely on a classification of organised or disorganised, explaining that profiles are derived through ‘the classification of the crime, its organised/disorganised aspects, the offender’s selection of a victim, strategies used to control the victim, the sequence of the crime, the staging (or not) of the crime, the offender’s motivation for the crime and the crime scene dynamics’ (p. 412).

An organised crime is one with evidence of planning, where the victim is a targeted stranger, where the crime scene reflects overall control, restraints are used, and there are aggressive acts prior to death. This suggests the offender is organised with the crime scene being a reflection of personality; they will generally be above average intelligence, be socially competent, prefer skilled work, have a high birth order, have a controlled mood during the crime, and are more likely to use alcohol (Douglas & Burgess, 1986 ; Ressler et al., 1992 ). Conversely, a disorganised crime shows spontaneity, where the victim or location is known, the crime scene is random and sloppy, there is sudden violence, minimal restraints are used, and there are sexual acts after death. This is again suggestive of the personality of the offender, with a disorganised offender being below average intelligence and socially inadequate, and having lower birth order, anxious mood during the crime and minimal use of alcohol or drugs (Douglas & Burgess, 1986 ; Ressler et al., 1992 ). Despite having discrete classifications, it is generally acknowledged that no one offender will fit so neatly into either type, with most being categorised as ‘mixed’ – that is, having elements of both types. The FBI dichotomy has received criticism from some practitioners (Canter et al., 2004 ; Canter & Heritage, 1990 ; Canter & Youngs, 2003 ), and there have been limited empirical findings published by the FBI in relation to practice changes (Fox & Farrington, 2018 ). One exception to this was the study conducted by Morton et al. ( 2014 ), who observed that ‘Dichotomous typologies by their very nature have challenges, as an “either/or” choice, cannot possibly explain complex, multiple event human interactions’ (p. 5). Further to this, Morton and colleagues suggested that profiling should serve as a tool that provides law enforcement investigators with investigative information, rather than providing classifications from predetermined categories or cumbersome typologies.

Diagnostic evaluations

Diagnostic evaluations do not represent a single profiling method per se but are instead a generic description of the services offered by mental health professionals, and largely rely on clinical judgement (Bradley, 2003 ). The profile provided by psychiatrist Dr James Brussel in 1956 to assist in the ‘Mad Bomber’ case is by far the most famous example of this approach to profiling (Brussel, 1968 ). In the early stages of profiling, the diagnostic and clinical approach occurred on an as-needed basis (Wilson et al., 1997 ), usually as one part of a broad range of psychological services. The contribution of mental health experts to investigations took shape when various police services asked whether clinical interpretations of unknown offenders might help in identification and apprehension (Canter, 1989 ). Even though other methods have come to the fore, largely eclipsing these early contributions, at the time of publication, Copson ( 1995 ) claimed that over half of the profiling done in the United Kingdom was by psychologists and psychiatrists using a clinical approach. In an early study of the range of services offered by police psychologists, Bartol ( 1996 ) found that, on average, 2% of the total monthly workload of in-house psychologists was spent on profiling, and that 3.4% of the monthly workload of part-time consultants was spent on profiling. Interestingly, despite diagnostic evaluations being among the earliest approaches, research on the attitudes of clinical practitioners revealed scepticism of profiling as a whole. For example, Bartol ( 1996 ) found that 70% of those questioned did not feel comfortable giving this advice, and felt that the practice was questionable. What is more (Bartol, 1996 , p. 79):

One well-known police psychologist with more than 20 years of experience in the field, considered criminal profiling ‘virtually pointless and dangerous’. Many of the respondents wrote that much more research needs to be done before the process becomes a useful tool.

Torres et al. ( 2006 ) show similar disdain for the practice. Of the 161 survey respondents, 10% had profiling experience, and 25% considered themselves knowledgeable of the practice. Less than 25% considered the practice to have sufficient scientific reliability or validity. However, despite this, many respondents also considered profiling a useful tool for law enforcement. In examining their role in profiling, McGrath ( 2001 , p. 321) suggests that clinicians may be well suited to the profiling process, owing to the following reasons:

- Their background in the behavioural sciences and their training in psychopathology place them in an enviable position to deduce personality and behavioural characteristics from crime scene information.

- The forensic psychiatrist is in a good position to infer the meaning behind signature behaviours.

- Given their training, education, and focus on critical and analytical thinking, the forensic psychiatrist is in a good position to ‘channel their training into a new field’.

Despite supporting this role, McGrath ( 2001 ) also notes that the clinician should be careful not to get caught up in, or focus too heavily on, treatment issues. This role confusion may come about because those conducting diagnostic evaluations may not often be exposed to the needs and wants of investigations, having little experience in reviewing crime scene data or witness depositions (West, 2000 ). However, the diagnostic evaluation approach to profiling has largely changed since these empirical studies were conducted during the 1990s through to the early 2000s. There has been an uprising in specialised police roles requiring registration as a psychiatrist or psychologist along with knowledge or experience in law enforcement investigations (e.g. see below a description of behavioural investigative advice). Consequently, the clinical and diagnostic approach to profiling is now embedded in specialised police positions, rather than in general forensic psychology and psychiatry practice.

Investigative psychology

Investigative psychology (IP) employs scientific research and is largely dependent on the empirical analysis conducted on individual crime types. Because IP relies more on empirical research than other inductive methods, strengths of this approach to practice are evident. However, a considerable issue in the use of applying this process to developing a criminal profile is the potential variance that may arise between profilers in determining the details of the crime and the applicability of relevant or suitable research. Furthermore, reliance on research may mean that crimes of extreme violence or low frequency may not be adequately researched to base a profile on. As with CIA, IP identifies profiling as only one part of an overall approach (Canter, 2000 , p. 1091):

The domain of investigative psychology covers all aspects of psychology that are relevant to the conduct of criminal and civil investigations. Its focus is on the ways in which criminal activities may be examined and understood in order for the detection of crime to be effective and legal proceedings to be appropriate. As such, investigative psychology is concerned with psychological input to the full range of issues that relate to the management, investigation and prosecution of crime.

Canter ( 2011 ) discussed the action–characteristics equation, whereby crime scene actions are followed by a process of deriving inferences, resulting in the identification of offender characteristics. The stage of inference development employs empirical procedures and a conceptually driven approach to establish actions and characteristics. The inference process seeks to examine interpersonal style, emotions, intellect, knowledge and familiarity, and skills. Upon analysis, conclusions are provided regarding the salience of the crime, case linkage, offender characteristics and based location. At the cornerstone of the IP approach to profiling is advanced statistical modelling and facet theory, forming both the empirical and conceptual approaches to IP practice (Canter & Youngs, 2003 ; Davis et al., 2018 ). However, although IP empirical research has provided a substantial contrition to profiling and investigating the nuanced aspects of offending, there is contention in regard to whether IP constitutes an individual approach to profiling, or instead an essential step in the provision of a profile (Davis et al., 2018 ; Rainbow et al., 2014 ; Snook et al., 2010 ).

Behavioural evidence analysis

The literature on behavioural evidence analysis (BEA) identifies that when rigorously applied to a criminal investigation the method aims to be largely deductive in nature; however, it should be noted than an absence of universal principles in the behavioural sciences renders this more an ideal than a reality. Additionally, given the reliance of deductive logic on inductive theories and the scientific method, it would be wrong to classify the method as wholly deductive. The theory of BEA states that conclusions about the offender should not be rendered unless specific physical evidence (based on a detailed crime reconstruction) exists. In BEA, the profiler spends a great deal of time establishing the veracity and validity of the physical evidence and its relationship to the criminal event. Indeed, this focus on detail is listed by some as a problem with the practice, specifically that deductive approaches are time consuming and provide limited information to investigators (see Holmes & Holmes, 2002 ).

Like many approaches, BEA is composed of steps or stages. The first, forensic analysis , refers to the examination, testing and interpretation of any and all physical evidence (Petherick & Turvey, 2008 ). To be able to understand any behavioural evidence, a full and complete reckoning of the physical evidence must be undertaken. Victimology , the second stage, examines any and all victim-related information such as height, sex, age, hobbies, habits and routines. Information derived during this stage can also help determine victim risk and target selection. Crime scene characteristics seeks to establish the distinguishing features of the crime scene, including the method of approach and attack, the method of control, location type, nature and sequence of any sexual acts, materials used, precautionary acts and verbal activity (Petherick & Turvey, 2008 ).

Offender characteristics , the final stage, assesses all of the above information for themes that collectively suggest personality or behavioural characteristics of the offender. In contrast to other approaches, BEA proposes a smaller number of characteristics that can be definitively established, including knowledge of the victim, knowledge of the crime scene, knowledge of methods and materials, criminal skill and motive (see Petherick, 2014a ).

Behavioural investigative advice

In the early 2000s, a new method of supporting police investigation known as behavioural investigative advice (BIA) emerged in the United Kingdom. The BIA discipline seeks to offer a broad range of psychological and scientific assistance to police investigations, including, but not limited to offender profiling (Rainbow et al., 2014 ). The role of BIAs is to offer senior investigative officers extra support and enhance their decision making during serious crime investigations through the use of behavioural science theory, research and expertise (Davis et al., 2018 ). The use of BIAs to assist investigations is considered to be positive and an essential step in incorporating specialised expertise into policing. However, in considering offender profiling, it is unclear as to the processes that BIAs use in assisting investigations and developing profiles. It would seem that BIA is a distinct profession, rather than a variation in profiling practice (Davis et al., 2018 ). Although research presented by BIAs has proposed the use of decision-making models (see Alison et al., 2003 ) to reach profile conclusions, the standards of evidence required for a BIA to develop a profile appears varied. An example of the decision making employed in BIA profiles was provided by Alison et al. ( 2003 ) who proposed the application of Toulmin’s ( 1958 ) philosophy of argument. The principles of applying this structure of argument to profiling was due to ‘the need for the justificatory functioning of substantive argument, whilst also being aware of the limitations of formal deductive, decontextualized logic for practical, ‘real world’ issues’ (Alison et al., 2003 , p. 174). In applying these principles to derive a profile, a profile statement must be derived from backing, warrant, grounds, modality and the consideration of rebuttal. The application of structured argument and evidence-based consideration in a profile is considered to be paramount to scientific practice and demonstrates support for the BIA discipline. BIA appears to be a progressive approach to criminal profiling and has received empirical recognition through a developing body of research (Alison et al., 2010 ; Almond et al., 2011 ; Marshall & Alison, 2011 ). For example, studies have reported positive police satisfaction with BIA involvement in cases and recommendations (Almond et al., 2011 ; Cole & Brown, 2011 ). The development of BIA practice is considered promising for both profiling and investigative assistance; however, the discipline would benefit from further scientific scrutiny in relation to operational approaches. The use of principles to derive a structured argument is essential in profiling, yet the development of a supported argument is only part of the required decision-making processes for producing a profile, with considerable degree and variation possible without a standardised practice framework. BIA is a progressive discipline, although subject to fallibility without process prioritisation and practice uniformity.

Towards integrated practice in criminal profiling

The variation across profiling practices has resulted in inconsistencies emerging in relation to the reliance on evidence, conclusions provided and the investigative utility of profiles (Almond et al., 2011 ; Fox et al., 2020 ). This has ranged from profiles providing statements without justification or the possibility of falsification, being derived predominantly on research conclusions, dismissing inconsistencies in a case, preferencing typology characteristics, omitting victimology evidence, selectively reporting confirmatory evidence, being provided verbally and without documentation, and failing to evaluate all case materials (Almond et al., 2011 ; Morton et al., 2014 ; Petherick & Brooks, 2014 ; Petherick & Ferguson, 2010 ; Turvey, 2012 ; Wilson et al., 1997 ). Each approach is characterised by strengths and weakness. For example, the linking of crime scene evidence with valid conclusions as evident in the BEA method provides scientific efficacy; however, this method can also be limiting, offering a narrow profile and minimal investigate assistance. According to Alison et al. ( 2003 ), the success of a profile is dependent on the types of conclusions provided, rather than the method used to derive these. For substantiated conclusions in profiles, there must be evidence of logical argument and pragmatic utility, ensuring conclusions are both logical and practical (Alison et al., 2010 ; Almond et al., 2011 ). Any conclusion/statement provided in a profile must have grounding, warrant, veracity and the capacity for falsification consistent with principles of the structure of argument (Toulmin, 1958 ). The grounding of the argument must be supported by scientific knowledge, whilst the warrant of the argument must permit this to be demonstrated in specialised research. In relation to veracity, there must be a form of specification in regard to the likelihood or probability of the claim occurring, whilst falsification must be possible, ensuring that that the statement or claim can be tested or disproven (Alison et al., 2003 ; Toulmin, 1958 ). Along with the profiles being derived from evidence and grounded in logical conclusions, statistical regularities between the types of offence and the types of offender characteristics can offer further investigative utility (Fox et al., 2020 ). As Fox and Farrington ( 2018 ) state, ‘all future profiles should be developed using a solid empirical approach that relies on advanced statistical analysis of large data sets’ (p. 1263). Consequently, it appears that the discipline of criminal profiling would benefit from an integrated approach to practice that provides a framework for the provision of profiles. An integrated framework serves to support the strengths of each methodology, whilst providing a structured guide to profile development. The current issues pertaining to profiling are akin to the limitations identified with the early generation of psychological risk assessments, with a need to integrate empirical findings, practitioner expertise and processes of practice. The issues in the field of risk assessment resulted in adjustments to practice and the development of a new generation of assessment instruments known as structured professional judgments (SPJs; Cooper et al., 2008 ; Davis & Ogloff, 2008 ; Gormley & Petherick, 2015 ). The introduction of SPJs has permitted an integrative approach to risk assessment, assimilating the scientific basis of the actuarial approach along with the benefits of the clinical approach. In accordance with the need for integrated practice in criminal profiling, a structural framework is proposed, represented by the acronym CRIME. The CRIME framework seeks to overcome the pitfalls of singular profiling approaches and instead provide a structured framework for profile development, incorporating the strengths of each of the examined practices, whilst acknowledging the limitations and weakness of utilising a specific process. This framework is similar to other recommendations and is based upon a similar philosophy to that of at least the works of Davis and Bennett ( 2016 ) and Ackley ( 2017 ).

- C – Crime scene evaluations

- R – Relevancy of research

- I – Investigative or clinical opinion

- M – Methods of investigation

- E - Evaluation

The CRIME framework is centred on a tiered process of profile development. The first tier, crime scene evaluations , relies largely on the crime scene and the evidence present to determine justifications. Consistent with a BEA approach, conclusions cannot be reached without the presence of evidence at the crime scene indicating that a set behaviour or event has occurred. This tier is considered to carry primary significance in the profile, accompanied by the other tiers, which provide additional information of assistance to investigations. At this first phase, evaluations are determined in respect to crime scene evidence, victimology and offender behaviour. The second tier, relevancy of research , is intended to provide investigators with an overview of research on similar offending behaviour, noting factors of relevance in similar crimes and characteristics that have been found on these occasions. This step must specify the limitations of relying on this research and instead seek to provide education and background on the offending matter. The third tier, investigative or clinical opinion , is considered to carry less weight and should be included in profiles with caution. This may include investigators’ unique understanding of factors such as access of local areas, criminal trends or past victim patterns. These factors are provided in the profile as suggestions and knowledge that may be of note for investigators to consider and review during the investigative processes. This information is considered of lower investigative relevance and not based in fact. The penultimate stage and tier of the CRIME framework is methods of investigation . This stage aims to provide detailed implications arising from the aforementioned steps, indicating avenues for investigators to explore and offering techniques of investigation and advice in relation to the suspect. The final stage is evaluation , and involves a critical examination of the profile itself, the logic, reasoning and sequencing used to arrive at the profile, and any input the investigators have about the document. This also includes an evaluation of the profile in light of new information or evidence that has come to light since the profile was generated, along with a peer review of the profile before this is provided to the consumer.

An example of the application of the CRIME framework to the below scenario (adapted from Aydin & Dirilen-Gumus, 2011 , p. 2615–2616; Douglas et al., 1986 , p. 416) is as follows:

At 3.00 pm a young woman’s nude body was discovered on the roof top of an apartment building where she was living. The female had been extensively beaten to her face, and she had been strangled with the bag strap that belonged to her purse. Her nipples had been cut off after her death, and these had been placed on her chest. On the inside of her thigh in ink, were the words, ‘You can’t stop me’. On her abdomen, the words, ‘Fuck you’ were scrawled on this section of her body. The pendant that was usually worn by the woman, a Jewish sign (Chai) for good luck, was missing from around her neck. The missing pendant was presumed taken by the murderer. Her nylon stockings had been removed and loosely tied around her wrists and ankles near a railing, with her underpants pulled over her face. The crime scene revealed that the victim’s earrings that she had been wearing were placed symmetrically on either side of her head. An umbrella and ink pen had been inserted into the woman’s vagina and a hair comb was placed into her pubic hairs. Her jaw and nose had been broken, her molars were loosened, and due to the blunt force trauma, she had sustained multiple face fractures. The cause of death was determined to be asphyxia by ligature (purse strap) strangulation. There were also post-mortem bite marks on the victim’s thighs, along with several contusions, haemorrhages and lacerations to the body. The killer had defecated on the roof top and this was covered with the victims’ clothing.

The preliminary police reports revealed that another resident of the apartment building, a white male, aged 15 years, had discovered the victim’s wallet. The young male discovered the wallet in the stairwell between the third and fourth floors at approximately 8.20 am, keeping the wallet with him until he returned home from school for lunch that afternoon. Upon returning home, he gave the wallet to his father, a white male, aged 40 years. After receiving the wallet, the father went to the victim’s apartment at 2.50 pm and handed this to the victim’s mother whom she resided with. The mother contacted the day-care centre to inform her daughter about the wallet; however, upon contacting the centre, she learnt that her daughter had not appeared for work that morning. The mother, the victim’s sister and a neighbour began searching the building. Shortly afterwards they discovered the body, and the neighbour called the police. Initial investigations by police revealed that no witnesses had seen the victim after she left her apartment that morning.

The investigation revealed that the victim was a 26-year-old, 4′11″, 90-lb, white female. The victim resided with her mother and father in the apartment building. She awoke around 6.30 am on the day of her murder, dressed, had breakfast (consisting of coffee and juice) and left for work. The woman worked at a near-by day-care centre, where she was employed as a group teacher for handicapped children. When she would leave for work in the morning, she would often alternate between taking the elevator or walking down the stairs, depending on her mood. She had a slight curvature of the spine (kyphoscoliosis) and was a shy and quiet woman. The medical examiner’s report revealed that there was no semen in the victim’s vagina, but semen was detected on the victim’s body. There were visible bite marks on the victim’s thigh and knee area and the murderer had cut the victim’s nipples with a knife after she was deceased and written on her body. The stab wounds that she had sustained were not deep. The examination concluded that the cause of death was strangulation, first manual, then ligature, with the strap of her purse.

While the challenges of developing a profile based on a short scenario are evident, the outline in Table 1 of the integrated CRIME framework details a summary of how the steps may be initially formed and subsequently utilised. The profile should start with an overview of the crime and the details, before integrating the CRIME steps. Upon completion of the five steps, the practitioner producing the profile should summarise the information and provide a review of the importance of the information provided within the profile, again emphasising the reliance of evidence-based information in the profile, from both the standing research corpus and crime scene evidence.

CRIME profile development.

Not only is this approach useful for providing as holistic an understanding of the case as possible, undertaking the CRIME framework may also serve as a bootstrapping process for other types of advice investigators may request as a natural extension of the assistance. For example, having a deep understanding of the crimes of a serial criminal may assist with the process of case linkage where one attempts to link previously unlinked cases to one offender or offender group. Similarly, the profiler/analyst may be able to provide insight into risk assessment of a serial or other offender to determine the likelihood that they will escalate or graduate to other crimes, such as from a sex offender to a killer.

Recommendations and conclusion

For profiling to develop as a discipline, greater scientific rigor is required, with profiles needing to incorporate logic and reasoning that are supported by appropriate evidence and justification. Criminal profiling must have investigative utility, assisting investigations, rather than creating confusion or misleading cases. Secondly, for profiling to advance there must be a move towards scientific practice, with uniformity across the field essential for admissibility in court (Freckelton, 2008 ) should the profiler/analyst be appropriately qualified for such endeavours. Although profiling is intended to develop investigative hypotheses, given the progression towards evidence-based policing, some proponents have suggested that for profiling to constitute a scientific method, court and legal admissibility is essential (Bosco et al., 2010 ; Freckelton, 2008 ; Petherick & Brooks, 2014 ). Currently, profiling regularly fails to add probative value to cases, and instead is considered to have a greater prejudicial effect (Bosco et al., 2010 ). One of the central challenges to profiling meeting admissibility standards in courts has been due to the inconsistencies in practice, with large discrepancies observed across approaches and methods of practice. The reliance on singular methods appears largely problematic, failing to consider the strengths of other profiling modalities, while also exposing investigations to the fragility of a sole method approach.

For profiling to develop as a forensic science and ultimately have admissibility in court, the discipline must be reliable, subject to peer review and scientific publication, be generally accepted amongst fellow practitioners, have guiding or governing standards, have identifiable error rates, and be implemented only in appropriate and applicable cases (Bosco et al., 2010 ). Subsequently, it is proposed that a joint methodology be employed when constructing criminal profiles, focusing on the strengths of each profiling approach and establishing uniformity in practice standards. It is suggested that this approach form the CRIME framework, consisting of crime scene evaluations, relevancy of research, investigative or clinical opinions, methods of investigation and evaluation. The CRIME approach provides a framework to promote the scientific practice of profiling, aiming to assist in the reliability of the practice by detailing a standardised process of developing profiles. It is intended that through the CRIME framework profiles will encompass error rates, specified in the crime scene evaluation and relevancy of research stages, whilst the evaluation stage seeks to incorporate peer review and consultation into practice. For profile to continue as a discipline, systemisation and evidence-based practice is required. Although the CRIME framework is not the ultimate solution to developing a ‘gold standard’ in criminal profiling, the approach seeks to promote integration and unity in practice, an essential first step in establishing practice consistency. It is recommended that future research seek to explore the benefit of profiles derived through the framework, reviewing the consistency and emergence of evidence-based practice. This could be investigated through police satisfaction, profile accuracy and the evidence of reasoning underpinning profiles derived through the CRIME framework. The future of profiling is dependent on the discipline progressing towards science, and integrated practice is the first fundamental step (Fox & Farrington, 2018 ).

Ethical standards

Declaration of conflicts of interest.

Wayne Petherick has declared no conflicts of interest

Nathan Brooks has declared no conflicts of interest

Informed consent

The article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

- Ackley, C. N. (2017). Criminal investigative advice: A move toward a scientific, multidisciplinary model. In Van Haselt V. B. & Bourke M. L. (Eds.), Handbook of behavioural criminology (pp. 215–238). Springer. [ Google Scholar ]

- Alexandra, A., Matthews, S., & Miller, M. (2002). Reasons, values, and institutions . Tertiary Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Alison, L., Smith, M. D., Eastman, O., & Rainbow, L. (2003). Toulmin’s philosophy of argument and its relevance to offender profiling . Psychology, Crime & Law , 9 , 173–183. doi: 10.1080/1068316031000116265 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Alison, L., Goodwill, A., Almond, L., van den Heuvel, C., & Winter, J. (2010). Pragmatic solutions to offender profiling and behavioural investigative advice. Legal and Criminological Psychology , 15 (1), 115–132. doi: 10.1348/135532509X463347 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Almond, L., Alison, L., & Porter, L. (2011). An evaluation and comparison of claims made in behavioural investigative advice reports compiled by the National Policing Improvement Agency in the United Kingdom. In Alison L., Rainbow L., & Knabe S. (Eds.), Professionalising offender profiling: Forensic and investigative psychology in practice . Routledge. [ Google Scholar ]

- Aydin, F., & Dirilen-Gumus, O. (2011). Development of a criminal profiling instrument . Procedia Social and Behavioural Sciences , 30 , 2612–2616. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bartol, C. R. (1996). Police psychology: Then, now and beyond . Criminal Justice and Behaviour , 23 ( 1 ), 70–89. doi: 10.1177/0093854896023001006 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Battacharyya, S. (1958). The concept of logic . Philosophy and Phenomenological Research , 18 ( 3 ), 326–340. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bateman, A. L., & Salfati, C. G. (2007). An examination of behavioral consistency using individual behaviors or groups of behaviors in serial homicide . Behavioral Sciences & the Law , 25 ( 4 ), 527–544. doi: 10.1002/bsl.742 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bevel, T. (2001). Applying the scientific method to crime scene reconstruction . Journal of Forensic Identification , 51 ( 2 ), 150–165. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bevel, T., & Gardner, R. M. (2008). Bloodstain pattern analysis with an introduction to crime reconstruction (3rd ed.). CRC Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bosco, D., Zappalà, A., & Santtila, P. (2010). The admissibility of offender profiling in courtroom: A review of legal issues and court opinions . International Journal of Law and Psychiatry , 33 ( 3 ), 184–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2010.03.009 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bradley, P. (2003). Criminal profiling: What’s it all about? Inpsych. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brussel, J. A. (1968). Casebook of a crime psychiatrist . Bernard Geis Associates. [ Google Scholar ]

- Burgess, A. W., & Ressler, R. K. (1985). Sexual homicides: Crime scene and pattern of criminal behaviour . National Institute of Justice Grant 82-IJ-CX-0065, US Department of Justice. https://www.ncjrs.gov/App/Publications/abstract.aspx?ID=98230 .

- Canter, D. (1989). Offender profiles . The Psychologist , 2 ( 1 ), 12–16. [ Google Scholar ]

- Canter, D. (2000). Investigative psychology. In Siegel J., Knupfer G., & Saukko P. (Eds.), Encyclopedia of forensic science . Academic Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Canter, D. V. (2011). Resolving the offender “Profiling equations” and the emergence of an investigative psychology . Current Directions in Psychological Science , 20 ( 1 ), 5–10. doi: 10.1177/0963721410396825 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Canter, D. V., Alison, L. J., Alison, E., & Wentink, N. (2004). The organized/disorganized typology of serial murder: Myth or model? Psychology, Public Policy, and Law , 21 , 293–320. [ Google Scholar ]

- Canter, D. V., & Heritage, R. (1990). A multivariate model of sexual offence behaviour: Development in “offender profiling”: I . The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry , 1 ( 2 ), 185–212. doi: 10.1080/09585189008408469 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Canter, D. V., & Youngs, D. (2003). Beyond ‘offender profiling’: The need for an investigative psychology. In Carson D. & Bull R. (Eds.), Handbook of psychology in legal contexts (2nd ed., pp. 171–205). Wiley. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cole, T., & Brown, J. (2011). What do senior investigative police officers want from behavioural investigative advisers. In Alison L., Rainbow L., & Knabe S. (Eds.), Professionalising offender profiling: Forensic and investigative psychology in practice . Routledge. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cooper, B. S., Griesel, D., & Yuille, J. C. (2008). Clinical-forensic risk assessment. The past and current state of affairs . Journal of Forensic Psychology Practice , 7 ( 4 ), 1–63. doi: 10.1300/J158v07n04_01 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Copson, G. (1995). Coals to Newcastle? Part 1: A study of offender profiling. Police Research Group Special Interest Paper 7 . Home Office. [ Google Scholar ]

- Davis, M. R., & Bennett, D. (2016). Future directions for criminal behaviour analysis of deliberately set fire events. In Doley R. M., Dickens G. L., & Gannon T. A. (Eds.), The psychology of arson: A practical guide to understanding and managing deliberate firesetters (p. 131–146). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. [ Google Scholar ]

- Davis, M. R., & Ogloff, J. R. P. (2008). Risk assessment. In Fritzon K. & Wilson P. (Eds.), Forensic psychology and criminology: An Australian perspective (pp. 141–164). McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd. [ Google Scholar ]

- Davis, M., Rainbow, L., Fritzon, K., West, A., & Brooks, N. (2018). Behavioural investigative advice: A contemporary commentary on offender profiling activity. In Griffiths A. & Milne R. (Eds.), The psychology of criminal investigation: From theory to practice (pp. 187–206). Routledge. [ Google Scholar ]

- Douglas, J. E., & Burgess, A. E. (1986). Criminal profiling: A viable investigative tool against violent crime . FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin , 55 , 9–13. [ Google Scholar ]

- Douglas, J. E., Ressler, R. K., Burgess, A. W., & Hartman, C. R. (1986). Criminal profiling from crime scene analysis . Behavioral Sciences & the Law , 4 ( 4 ), 401–422. doi: 10.1002/bsl.2370040405 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Farber, M. (1942). Logical systems and the principles of logic . Philosophy of Science , 9 ( 1 ), 40–54. doi: 10.1086/286747 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2002). Uniform crime report . www.fbi.gov/ucr/cius_02/html/web/index.html

- Fox, B., Farrington, D. P., Kapardis, A., & Hambly, O. C. (2020). Evidence-based offender profiling . Routledge. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fox, B., & Farrington, D. P. (2018). What have we learned from offender profiling? A systematic review and meta-analysis of 40 years of research . Psychological Bulletin , 144 ( 12 ), 1247–1274. doi: 10.1037/bul0000170 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Freckelton, I. (2008). Profiling evidence in the courts. In Canter D. & Žukauskienė R. (Eds.), Psychology and law: Bridging the gap (pp. 79–102). Routledge. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gekoski, A., & Gray, J. M. (2011). It may be true, but how’s it helping?’: UK police detectives’ views of the operational usefulness of offender profiling . International Journal of Police Science & Management , 13 ( 2 ), 103–116. doi: 10.1350/ijps.2011.13.2.236 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Goldsworthy, T. (2001). Criminal profiling. Is it investigatively relevant? [Master of criminology dissertation]. Bond University. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gormley, J., & Petherick, W. (2015). Risk assessment. In Petherick W. (Ed.), Applied crime analysis: A social science approach to understanding crime, criminals, and victims (pp. 172–189). Elsevier. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hazelwood, R. R., & Douglas, J. E. (1980). The lust murderer . FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin , 49 ( 4 ), 1–5. [ Google Scholar ]

- Holmes, R., & Holmes, S. (2002). Profiling violent crimes: An investigative tool (3rd ed.). Sage Publications. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kocsis, R. N. (2001). Serial arsonist crime profiling: An Australian empirical study . Firenews. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kocsis, R. N., Irwin, H. J., Hayes, A. F., & Nunn, R. (2000). Expertise in psychological profiling: A comparative assessment . Journal of Interpersonal Violence , 15 ( 3 ), 311–331. doi: 10.1177/088626000015003006 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Marshall, B. C., & Alison, L. (2011). Stereotyping, congruence and presentation order: Interpretative biases in utilizing offender profiles. In Alison L., Rainbow L., & Knabe S. (Eds.), Professionalising offender profiling: Forensic and investigative psychology in practice . Routledge. [ Google Scholar ]

- McGrath, M. (2001). Criminal profiling: Is there a role for the forensic psychiatrist? Journal of the American Academy of Forensic Psychiatry and Law , 28 ( 3 ), 315–324. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Morton, R. J., Tillman, J. M., & Gaines, S. J. (2014). Serial murder: Pathways for investigations . U.S. Department of Justice. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mouzos, J. (2005). Homicide in Australia: 2003-2004 national homicide monitoring program (NHMP) annual report . Australian Institute of Criminology. [ Google Scholar ]

- Navarro, J., & Schafer, J. R. (2003). Universal principles of criminal behavior: A tool for analyzing criminal intent. FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin , 72 (1), 22–24. https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/fbileb72&i=23 [ Google Scholar ]

- Neblett, W. (1985). Sherlock’s logic: Learn to reason like a master detective . Barnes and Noble Books. [ Google Scholar ]

- Niiniluoto, I. (1999). Defending abduction . Philosophy of Science , 66 , S436–S451. http://www.jstor.com/stable/188790 [ Google Scholar ]

- Petherick, W. A. (2014a). Criminal profiling methods. In Petherick W. A. (Ed.), Profiling and serial crime: Theoretical and practical issues in behavioural profiling (3rd ed.). Anderson Publishing. [ Google Scholar ]

- Petherick, W. A. (2014b). Induction and deduction in criminal profiling. In Petherick W. A. (Ed.), Profiling and serial crime: Theoretical and practical issues in behavioural profiling (3rd ed.). Anderson Publishing. [ Google Scholar ]

- Petherick, W. A., & Brooks, N. (2014). Where to from here? In Petherick W. A. (Ed.), Profiling and serial crime: Theoretical and practical issues in behavioural profiling (3rd ed., pp. 241–259). Anderson Publishing. [ Google Scholar ]

- Petherick, W. A., & Ferguson, C. E. (2010). Ethics for the forensic criminologist. In Petherick W. A., Turvey B. E., & Ferguson C. E. (Eds.), Forensic Criminology . Elsevier Science. [ Google Scholar ]

- Petherick, W. A., & Turvey, B. E. (2008). Behavioral evidence analysis: An ideo deductive method of criminal profiling. In Turvey B. E. (Ed.), Criminal profiling: An introduction to behavioral evidence analysis (3rd ed). Academic Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pierce, C. S. (1898). Reasoning and the logic of things: The Cambridge conferences lectures of 1898 . In K. L. Ketner (Ed.). Harvard University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pinizzotto, A. J., & Finkel, N. J. (1990). Criminal personality profiling: An outcome and process study . Law and Human Behavior , 14 ( 3 ), 215–233. doi: 10.1007/BF01352750 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rainbow, L., & Gregory, A. (2011). What behavioural investigative advisers actually do. In L. Alison & L. Rainbow (Eds.), Professionalizing offender profiling: Forensic and investigative psychology in practice (pp. 35–50). Routledge. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rainbow, L., Gregory, A., & Alison, L. (2014). Behavioural investigative advice. In Bruinsma G. J. N. & Weisburd D. L. (Eds.), Encyclopedia of criminology and criminal justice (pp. 125–134). Springer. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ressler, R. K., Burgess, A. W., & Douglas, J. E. (1992). Sexual homicide: Patterns and motives . Free Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Snook, B., Eastwood, J., Gendreau, P., & Bennell, C. (2010). The importance of knowledge cumulation and the search for hidden agendas: A reply to Kocsis, Middledorp, and Karpin (2008). Journal of Forensic Psychology Practice , 10 (3), 214–223. doi: 10.1080/15228930903550541 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stock, G. W. J. (2004). Deductive logic . Project Gutenberg Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Thornton, J. (1997). The general assumptions and rationale of forensic identification. In Faigman D. L., Kaye D. H., Saks M. J., & Sanders J. (Eds.), Modern scientific evidence: The law and expert testimony . West Publishing. [ Google Scholar ]

- Torres, A. N., Boccaccini, M. T., & Miller, H. A. (2006). Perceptions of the validity and utility of criminal profiling among forensic psychologists and psychiatrists . Professional Psychology: Research and Practice , 37 ( 1 ), 51–58. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.37.1.51 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]