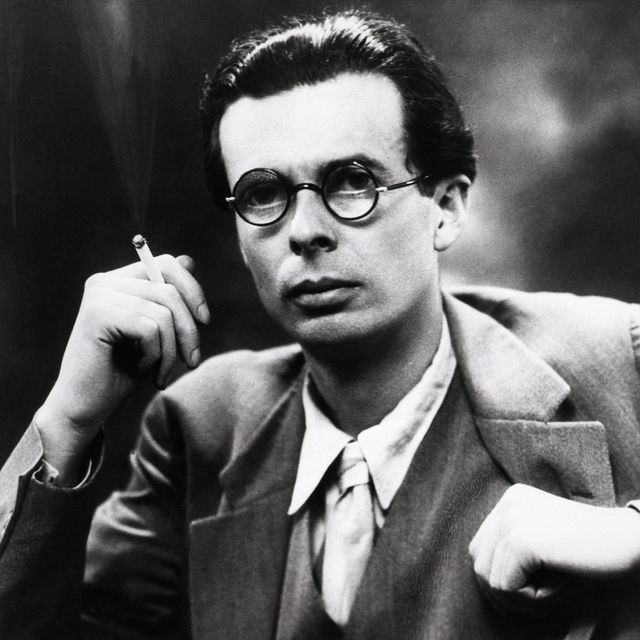

Aldous Huxley

(1894-1963)

Who Was Aldous Huxley?

After a serious illness left him partially blind as a youth, Aldous Huxley abandoned his dreams of becoming a scientist to pursue a literary career. In 1916 he graduated with honors from Balliol College at Oxford University and published a collection of poems. Five years later he published his debut novel Crome Yellow , which brought him his first taste of success. He followed with several more equally successful satirical novels before publishing the work for which he is best known, Brave New World . A dark vision of the future, it is widely regarded as one of the greatest novels of the 20th century. Huxley moved to the United States in 1937 and for the rest of his life maintained a prolific output of novels, nonfiction, screenplays and essays.

Aldous Huxley was born in Godalming, England, on July 26, 1894. The fourth child in a family with a deep intellectual history, his grandfather was the noted biologist and naturalist T. H. Huxley, an early proponent of Charles Darwin ’s theory of evolution; his father, Leonard, was a teacher and writer; and his mother, Julia, was a descendant of the English poet Matthew Arnold. In adulthood, Huxley’s older brothers, Julian and Andrew, would both become accomplished biologists, and Huxley himself envisioned a future career in science from an early age.

But while he was still a boy, Huxley’s life would be upended by tragedy. In 1908 his mother died of cancer, and in 1911 he was struck blind by the disease keratitis punctata. Although Huxley did regain some of his sight, he would remain partially blind for the rest of his life and read with great difficulty. As a result, while attending the prestigious prep school Eton, Huxley abandoned his dreams of becoming a scientist and decided to focus on a literary career. Fate struck Huxley one more blow in 1914 when his brother Noel committed suicide after struggling with an extended period of depression.

Burgeoning Writer

A brilliant student despite the obstacles of his youth, Huxley earned a scholarship to Balliol College at Oxford University, where he studied English literature, reading with the aid of a magnifying glass and eye drops that dilated his pupils. He also began to write poetry, and in 1916 he published his first book, a collection of poems titled The Burning Wheel , the same year in which he graduated with honors.

Perhaps more important to his literary aspirations, however, was the time during this period that he spent at Garsington Manor, the home of socialite Lady Ottoline Morrell and a gathering place for intellectuals and writers such as Virginia Woolf , Bertrand Russell, T. S. Eliot and D. H. Lawrence , with whom Huxley would develop a lasting friendship. With his encyclopedic knowledge, matched only by his wit and skill as a conversationalist, it was at Garsington that Huxley first established his reputation as one of the most significant minds in England.

Leveraging this reputation, Huxley contributed articles to such periodicals as The Athenaeum , Vanity Fair and Vogue and published several more collections of poetry as well. In 1919 he also made advances in his personal life, marrying Maria Nys. She gave birth to their son, Matthew, the following year.

'Brave New World'

Amidst all of these professional and personal developments, Huxley began work on his novel Crome Yellow , a parody of the intelligentsia and his experiences at Garsington. Although the book's publication in 1921 angered many of his Garsington acquaintances, it also established Huxley as an important writer and sold well enough to allow him to pursue his literary destiny. While traveling about Europe with his family for the next several years, Huxley produced the commercially successful novels Antic Hay (1923), Those Barren Leaves (1925) and Point Counter Point (1928), which, like Crome , were satires of contemporary society and conventional morality. Huxley’s greatest work, however, was still to come.

Ensconced in his recently purchased villa in the South of France, in late 1931 Huxley began work on what is now widely considered to be one of the Western canon's most important novels. Published in 1932, Brave New World marks the apogee of Huxley’s abilities as a satirist. The world it presents, however, is viewed through a much darker lens, informed by the writer’s growing anxieties about the direction of political, social and scientific progress. Brave New World is also an astonishingly prescient novel, foretelling advances in each of these areas that were as much as a half-century away.

Set in London in 2540, the 7th century After Ford, Brave New World presents a future in which genetically engineered babies are produced on assembly lines, the social and economic divide between the haves and the have nots is legally enforced and discontent is quelled by advertising, medication, sex and entertainment. Now, nearly a century from the novel’s publication, among its prophecies that have come to pass are the rise of dictatorial governments, in vitro fertilization, genetic cloning, virtual reality, antidepressants and the invention of the helicopter.

The novel proved to be a massive critical and commercial success, cementing Huxley’s place as one of the most important writers of the era. In the decades that followed, that prestige would enable Huxley to not only indulge his love of travel but to also explore new ways of being.

Novels, Essays, Screenwriting and More

Huxley followed Brave New World with the 1936 novel Eyeless in Gaza , which showed his blossoming interest in Eastern philosophy and mysticism. The following year, he left Europe for North America, where he completed a work on pacifism titled Ends and Means , and in 1938 he settled in Los Angeles, California, where he would spend most of the rest of his life. During this time, Huxley added screenwriter to his long list of occupations and was paid handsomely by studios for his work. Among his more notable film credits are Pride and Prejudice (1940), Jane Eyre (1943) and Madame Curie (1943).

Settled comfortably in a Hollywood Hills home, in between screenplays Huxley continued his prolific literary output, completing the novels After Many a Summer Dies the Swan (1939), Time Must Have a Stop (1944) and Ape and Essence (1948) and the nonfiction works The Art of Seeing (1943, which chronicled a method used to improve his eyesight), The Perennial Philosophy (1946) and The Devils of Loudon (1952). He also worked on countless articles and editorials. Much of what time he had left he devoted to his interest in Eastern mysticism, beginning a decades-long association with the Vedanta Society, whose journal Huxley contributed numerous pieces to. This interest in mysticism also led Huxley to experiment with the hallucinogen mescaline, which he wrote about in his 1954 collection of essays The Doors of Perception . The title would later be appropriated by Jim Morrison as the name for his legendary rock group, the Doors.

A More Utopian Vision

In early 1955, Maria died of cancer, and later that year Huxley published his next novel, The Genius and the Goddess . In 1956, Huxley married his second wife, Laura, who would later write a biography of their life together titled This Timeless Moment (1968). In 1958, he published a collection of essays titled Brave New World Revisited , in which he took stock of the present day and argued that it alarmingly resembled the reality of his 1932 novel.

As Huxley tirelessly explored both the world around him and his inner self, sharing his findings through his work, in 1960 he was diagnosed with cancer. For the next two years he persevered, however, completing what would prove to be his last novel, The Island (1962), which placed a more positive spin on some of the themes Huxley addressed in Brave New World .

With Laura at his bedside, Huxley died on November 22, 1963, at the age of 69, having written more than 50 books, including one of the most significant of the 20th century, as well as innumerable works of criticism, poetry and drama. But despite his immense literary stature, his passing went largely unnoticed at the time, occurring as it did on the same day that President John F. Kennedy was assassinated.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Aldous Huxley

- Birth Year: 1894

- Birth date: July 26, 1894

- Birth City: Godalming

- Birth Country: United Kingdom

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Author and screenwriter Aldous Huxley is best known for his 1932 novel 'Brave New World,' a nightmarish vision of the future.

- Fiction and Poetry

- Astrological Sign: Leo

- Balliol College

- Interesting Facts

- Aldous Huxley died on the same day as fellow author C. S. Lewis and President John F. Kennedy.

- Death Year: 1963

- Death date: November 22, 1963

- Death State: California

- Death City: Los Angeles

- Death Country: United States

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Aldous Huxley Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/authors-writers/aldous-huxley

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: June 29, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

Famous Authors & Writers

The Truth Behind Edgar Allan Poe’s Terror Tales

How Did Shakespeare Die?

A Huge Shakespeare Mystery, Solved

Shakespeare Wrote 3 Tragedies in Turbulent Times

The Mystery of Shakespeare's Life and Death

Was Shakespeare the Real Author of His Plays?

20 Shakespeare Quotes

William Shakespeare

The Ultimate William Shakespeare Study Guide

Suzanne Collins

Alice Munro

- Humanities ›

- Literature ›

- Classic Literature ›

- Authors & Texts ›

Biography of Aldous Huxley, British Author, Philosopher, Screenwriter

Author of Dystopian Novel 'Brave New World'

Bettmann / Getty Images

- Authors & Texts

- Top Picks Lists

- Study Guides

- Best Sellers

- Plays & Drama

- Shakespeare

- Short Stories

- Children's Books

- M.A., Classics, Catholic University of Milan

- M.A., Journalism, New York University.

- B.A., Classics, Catholic University of Milan

Aldous Huxley (July 26, 1894–November 22, 1963) was a British writer who authored more than 50 books and a large selection of poetry, stories, articles, philosophical treatises, and screenplays. His work, especially his most renowned and often controversial novel, Brave New World , has served as a form of social critique to the ills of the current era. Huxley also enjoyed a successful career as a screenwriter and became an influential figure in American counterculture.

Fast Facts: Aldous Huxley

- Full Name: Aldous Leonard Huxley

- Known For : His eerily accurate portrayal of dystopian society in his book Brave New World (1932) and for his devotion to Vedanta

- Born : August 26, 1894 in Surrey, England

- Parents : Leonard Huxley and Julia Arnold

- Died : November 22, 1963 in Los Angeles, California

- Education : Balliol College, Oxford University

- Notable Works: Brave New World (1932), Perennial Philosophy (1945), Island (1962)

- Partners: Maria Nys (married 1919, died 1955); Laura Archera (married 1956)

- Children: Matthew Huxley

Early Life (1894-1919)

Aldous Leonard Huxley was born in Surrey, England, on July 26, 1894. His father, Leonard, was a schoolmaster and editor of the literary journal Cornhill Magazine, while his mother, Julia, was the founder of Prior’s School. His paternal grandfather was Thomas Henry Huxley, the famed zoologist known as “Darwin’s Bulldog.” His family had both literary and scientific intellectuals—his father also had botanical laboratory—, and his brothers Julian and Andrew Huxley eventually became famed biologists in their own right.

Huxley attended Hillside school, where he was taught by his mother until she became terminally ill. Subsequently, he transferred to Eton College.

In 1911, at age 14, he contracted keratitis punctata, an eye disease that left him practically blind for the next two years. Initially, he wanted to become a doctor, but his condition prevented him from pursuing that path. In 1913, he enrolled in Balliol College at Oxford University, where he studied English Literature, and in 1916 he edited the literary magazine Oxford Poetry. Huxley volunteered for the British Army during World War I, but was rejected due to his eye condition. He graduated in June 1916 with first-class honors. Upon graduating, Huxley briefly taught French at Eton, where one of his pupils was Eric Blair, better known as George Orwell.

While World War I was raging, Huxley spent his time at Garsington Manor, working as a farmhand for Lady Ottoline Morrell. While there, he became acquainted with the Bloomsbury Group of British intellectuals, including Bertrand Russell and Alfred North Whitehead. In the 20s, he also found employment at the chemical plant Brunner and Mond, an experience that greatly influenced his work.

Between Satire and Dystopia (1919-1936)

- Crome Yellow (1921)

- Antic Hay (1923)

- Those Barren Leaves (1925)

- Point Counter Point (1928)

- Brave New World (1932)

- Eyeless in Gaza (1936)

Non-Fiction

- Pacifism and Philosophy (1936)

- Ends and Means (1937)

In 1919, literary critic and Garsington-adjacent intellectual John Middleton Murry was reorganizing the literary magazine Athenaeum and invited Huxley to join the staff. During that period of his life, Huxley also married Maria Nys, a Belgian refugee who was at Garsington.

In the 1920s, Huxley delighted in exploring the mannerisms of high society with dry wit. Crome Yellow poked fun at the lifestyle they led at Garsington Manor; Antic Hay (1923) portrayed the cultural elite as aimless and self-absorbed; and Those Barren Leaves (1925) had a group of pretentious aspiring intellectuals gathered in an Italian palazzo to relive the glories of the Renaissance. Parallel to his fiction writing, he also contributed to Vanity Fair and British Vogue.

In the 1920s, he and his family spent part of their time in Italy, as Huxley’s good friend D.H. Lawrence lived there and they would visit him. Upon Lawrence’s passing, Huxley edited his letters.

In the 1930s, he started writing about the dehumanizing effects of scientific progress. In Brave New World (1932), perhaps his most famous works, Huxley explored the dynamics of a seemingly utopian society where hedonistic happiness is offered in exchange for the suppression of individual freedom and the adherence to conformity. Eyeless in Gaza (1936), by contrast, had a cynic man overcome his disillusionment through Eastern philosophy. In the 1930s, Huxley also started writing and editing works exploring pacifism, including Ends and Means and Pacifism and Philosophy.

Hollywood (1937-1962)

- After Many a Summer (1939)

- Time Must Have a Stop (1944)

- Ape and Essence (1948)

- The Genius and the Goddess (1955)

- Island (1962)

- Grey Eminence (1941)

- The Perennial Philosophy (1945)

- The Doors of Perception (1954)

- Heaven and Hell (1956)

- Brave New World Revisited (1958)

Screenplays

- Pride and Prejudice (1940)

- Jane Eyre (1943)

- Marie Curie (1943)

- A Woman’s Vengeance (1948)

Huxley and his family moved to Hollywood in 1937. His friend, the writer and historian Gerald Heard, joined them. He spent a brief time in Taos, New Mexico, where he wrote the book of essays Ends and Means (1937), which explored topics such as nationalism, ethics, and religion.

Heard introduced Huxley to Vedanta, a philosophy centered on Upanishad and the principle of ahimsa (do no harm). In 1938, Huxley befriended Jiddu Krishnamurti, a philosopher with a background in theosophy, and throughout the years, the two debated and corresponded on philosophical matters. In 1954, Huxley penned the introduction to Krishnamurti’s The First and Last Freedom.

As a Vedantist, he joined the circle of Hindu Swami Prabhavananda and introduced fellow English expatriate writer Christopher Isherwood to the philosophy. Between 1941 and 1960, Huxley contributed 48 articles to Vedanta and the West , a periodical published by the society. Immediately after the end of World War II, Huxley published The Perennial Philosophy, which combined passages of Eastern and Western philosophy and mysticism.

During the war years, Huxley became a high-earning screenwriter in Hollywood, working for Metro Goldwyn Mayer. He used much of his paycheck to transport Jewish people and dissidents from Hitler’s Germany to the U.S.

Huxley and his wife Maria applied for United States Citizenship in 1953. However, given that he refused to bear arms and could not claim he did so for religious ideals, he withdrew his application, but remained in the United States.

In 1954, he experimented with the hallucinogenic drug mescaline, which he related in his work The Doors of Perception (1954) and Heaven and Hell (1956), and continued using a controlled amount of these substances until his death. His wife died of cancer in February 1955. The following year, Huxley married the Italian-born violinist and psychotherapist Laura Archera, the author of the biography This Timeless Moment.

His later work focused on expanding and rectifying the grim universe he portrayed in Brave New World . His book-length essay Brave New World Revisited (1958) weighs in on whether the world moved closer or further away from the World State Utopia he conjured; Island (1962) his final novel, by contrast, had a more utopian view of science and technology, as on the island of Pala, mankind does not have to bend to them.

Huxley was diagnosed with laryngeal cancer in 1960. When Huxley was on his deathbed, he was unable to speak due to the advanced state of his cancer, so he requested "LSD, 100 µg, intramuscular" to his wife Laura Archera in writing. She recounted this moment in her biography This Timeless Moment , and related that she gave him the first injection at 11:20 a.m. and a second dose an hour later. Huxley died at 5:20 p.m. on November 22, 1963.

Literary Style and Themes

Growing up in the late 19th and the early 20th centuries, Huxley was part of a generation that was fascinated and had great trust in the scientific progress. The era of the 2nd industrial revolution brought about a higher standard of living, medical breakthroughs, and a trust in the fact that progress could improve lives for good.

In his novels, plays, poems, travelogues, and essays, Huxley was able to employ low key ironic humor and wit, as it’s apparent in his early novel Crome Yellow (1921) and in the essay “Books for the Journey,” where he observed how bibliophiles tended to overpack during their travels. Yet, his prose was not devoid of poetic flourishes; these emerged in his essay “Meditation on the Moon,” which was a reflection on what the moon stands for in a scientific and in a literary or artistic context, as an attempt to reconcile the intellectual traditions in his family, which included both poets and scientists.

Huxley’s fiction and nonfiction works were controversial. They were praised for their scientific rigor, detached irony, and their panoply of ideas. His early novels satirized the frivolous nature of the English upper class in the 1920s, while his later novels dealt with moral issues and ethical dilemmas in the face of progress, as well as the human quest for meaning and fulfillment. In fact, his novels evolved into more complexity. Brave New World (1932) perhaps his most famous work, explored the tension between individual freedom, social stability, and happiness in a seemingly utopian society; and Eyeless in Gaza (1936) saw an Englishman marked by his cynicism turn to Eastern philosophy to breach through his jadedness.

Entheogens are a recurring element in Huxley’s work. In Brave New World, the population of the World State achieves a mindless, hedonistic happiness through a beverage named soma. In 1953, Huxley himself experimented with the hallucinogenic drug mescaline, which, allegedly, enhanced his sense of color, and he related his experience in The Doors of Perception, which made him a figurehead in 60s counterculture.

Aldous Huxley was a polarizing figure who was both hailed as an emancipator of the modern mind and condemned as an irresponsible free-thinker and an erudite showoff. Rock group The Doors, whose front man Jim Morrison was an enthusiastic drug user, owes its name to Huxley’s book The Doors of Perception.

Huxley died on November 22, 1963, hours after the assassination of president John F. Kennedy . Both deaths, unwittingly, heralded the rise of counterculture, where conformity and belief in the government were questioned.

- Bloom, Harold. Aldous Huxleys Brave New World . Blooms Literary Criticism, 2011.

- Firchow, Peter. Aldous Huxley: Satirist and Novelist . University of Minnesota Press, 1972.

- Firchow, Peter Edgerly, et al. Reluctant Modernists: Aldous Huxley and Some Contemporaries: a Collection of Essays . Lit, 2003.

- “In Our Time, Aldous Huxley's Brave New World.” BBC Radio 4 , BBC, 9 Apr. 2009, https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00jn8bc.

- 'Brave New World' Overview

- Biography of Edith Wharton, American Novelist

- List of Works by James Fenimore Cooper

- Sinclair Lewis, First American to Win Nobel Prize for Literature

- Biography of Colette, French Author

- Virginia Woolf Biography

- Biography of Charles Dickens, English Novelist

- The Life and Work of H.G. Wells

- What Were Mark Twain's Inventions?

- Biography of Henry Miller, Novelist

- Mark Twain: His Life and His Humor

- Biography of James Joyce, Influential Irish Novelist

- Biography of Willa Cather, American Author

- Biography of F. Scott Fitzgerald, Writer of the Jazz Age

- Biography of Kate Chopin, American Author and Protofeminist

- Biography of Bram Stoker, Irish Author

- Corrections

The Life of Aldous Huxley — Author of “Brave New World”

Best remembered for his dystopian masterpiece, Aldous Huxley was a man of unshakable principles that informed what he wrote and how he lived his life.

When Aldous Huxley passed away in 1963, his death was relatively little commented upon, coinciding as it did with the rather more shocking assassination of John F. Kennedy . Yet his death marked the loss, nonetheless, of one of the twentieth century’s most important writers and thinkers. He was deeply committed to pacifism, universalism, and mysticism, all of which shine through in his writing – be it fiction or non-fiction – and informed the way he lived his life, from refusing to bear arms when applying for US citizenship to using his substantial earnings as a screenwriter to fund the transportation costs of those fleeing Nazi Germany. Here, we will take a closer look at the life of the man behind Brave New World …

Early Life: Family Background, Bereavement, & Education

Born on July 26, 1894 near Godalming, Surrey, Aldous Leonard Huxley belonged to a family distinguished in both science and the world of letters. His father was Leonard Huxley, schoolmaster, writer, and editor of The Cornhill Magazine , who in turn was the son of Thomas Henry Huxley, a prominent zoologist often referred to as “Darwin’s bulldog.” His older brother, Julian, and half-brother, Andrew, would, in turn, follow in their grandfather’s footsteps, going on to enjoy celebrated careers in biology.

Additionally, Aldous Huxley’s mother, Julia Arnold, was the niece of the poet and cultural critic Matthew Arnold, and the sister of the novelist Mrs. Humphry Ward, after one of whose fictional characters Julia named her second son.

Aldous Huxley, then, was always expected to distinguish himself in one intellectual field or another. His parents were both involved in the early stages of his education, which began in his father’s botanical laboratory. He then attended Hillside School near the family home in Godalming, where he was taught by his mother before she became terminally ill with cancer.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Please check your inbox to activate your subscription.

Huxley’s mother died in 1908, by which time he had been sent to the elite Eton College. This formative loss – as well as his father’s later remarriage – inspired some of the events depicted in Huxley’s 1936 novel Eyeless in Gaza . While at Eton, he contracted keratitis in 1911, which left him with radically impaired vision for many years and effectively ended his hopes of pursuing a career in medicine.

Instead, in 1913, Huxley matriculated at Balliol College, Oxford University, to study English Literature – just as his mother had before him at Somerville College. He edited Oxford Poetry during his final year and graduated in 1916 with a first-class degree. In the same year, he published his first collection of poetry, The Burning Wheel .

Finding His Feet as a Writer

From 1917 to 1918, Huxley returned to Eton to teach English and French. While he struggled to maintain discipline in the classroom, among his students was a young Eric Blair, who would go on to be better known as George Orwell and who remembered his former teacher and fellow writer as having an admirable vocabulary. At the same time, Huxley published two further poetry collections: Jonah (1917) and The Defeat of Youth and Other Poems (1918).

While Huxley did not have great success upon his return to Eton, at the time of his graduation, jobs were scarce as Britain was still fighting the First World War . Having volunteered for the British Army and been rejected on account of his eyesight (his bout of keratitis left him partially sighted in one eye), he spent much of his time at Garsington Manor, the home of Lady Ottoline Morrel, near Oxford, where he was employed as a farm laborer. Ottoline invited many artists, writers, and intellectuals to Garsington, including members of the Bloomsbury Group , some of whom Huxley met. He would later satirize the Garsington milieu in his 1921 debut novel, Crome Yellow .

While at Garsington, however, he also met Belgian refugee and epidemiologist Maria Nys. After being offered a job at the Athenaeum under John Middleton Murry in 1919, Huxley and Nys married. A year later, Huxley published his first collection of short stories, Limbo (1920), which was soon followed by his debut novel, Crome Yellow . He continued to publish works throughout the 1920s, including the novels Antic Hay (1923), Those Barren Leaves (1925), and Point Counter Point (1928). In addition, he wrote for Vanity Fair and British Vogue .

1930s and 40s: The Golden Years & Moving to the United States

Huxley’s best-known works, however, were largely written in the 1930s. Brave New World , for example, was published in 1932. It was also during the 1930s that Huxley wrote what is now widely considered his most accomplished – if not most widely read – novel, Eyeless in Gaza (1936). Having been introduced to Gerald Heard in 1929, Huxley became increasingly committed to pacifism, which is reflected in many of his 1930s works, including Eyeless in Gaza , in which the aimless Anthony Beavis is converted to pacifism by Dr. James Miller. Huxley himself was actively involved in the Peace Pledge Union and edited An Encyclopedia of Pacifism .

Within its meditations on pacifism, Eyeless in Gaza also predicts the outbreak of another war. By the time World War II was declared in 1939, however, Huxley and his wife were living in the United States, having relocated in 1937 (the same year that Huxley’s pacifist essay collection, Ends and Means , was published) with his wife, son, and friend Gerald Heard, on account of Nys’ ill health.

Moving to the United States also gave Huxley access to highly lucrative screenwriting opportunities. According to friend and fellow writer Christopher Isherwood, Huxley earned more than $3,000 per week (an even more princely sum back in the 1930s) as a screenwriter for such film adaptations as Pride and Prejudice (1940) and Jane Eyre (1944).

Famously, in 1945, Huxley was commissioned by Walt Disney to write a script adapting Alice’s Adventure in Wonderland for the screen, which was never used as Disney claimed only to be able to understand every third word. It should also be noted that Isherwood also claimed, however, that Huxley used the majority of his screenwriting riches to fund the transportation of Jewish and left-wing refugees from Nazi Germany to safety in the United States.

World War II & Huxley’s Later Years

While Huxley only wrote two further novels – The Genius and the Goddess (1955) and Island (1962) – in the 1950s and 60s, his output of non-fiction works was prolific. Among his most famous was The Doors of Perception , published in 1954, which went on to become a foundational text for the counter-cultural revolution of the 1960s . In The Doors of Perception , he recounted his first experience taking the psychedelic drug Mescaline and, in so doing, would inspire Jim Morrison to name his band The Doors.

One year before the publication of The Doors of Perception , however, Huxley and his wife had applied for US citizenship. As a pacifist, Huxley stated his refusal to bear arms for the United States but did not specify that his objection was on religious grounds (the only reason, under the McCarran Act, that was deemed acceptable for the refusal to bear arms). Having reached this stalemate, the judge had no alternative but to adjourn the application, which Huxley, in turn, withdrew. Despite not having US citizenship, Huxley, Maria, and their son Matthew remained in the US, where Maria died of cancer just two years later, in 1955.

One year after Maria’s death, Huxley married a second time, taking Laura Archera, an American writer, psychotherapist, and violinist, as his wife. Laura went on to write a biography of her husband, titled This Timeless Moment and worked tirelessly to keep his literary legacy alive.

Their marriage, however, was relatively short-lived. In 1960, Huxley was diagnosed with laryngeal cancer. Nonetheless, he continued to work, delivering lectures at the UCSF Medical Center and the Esalen Institute that would inspire the Human Potential Movement. As well as this, he wrote his final novel, Island, in 1962 as well as what is perhaps his seminal work of non-fiction, Literature and Science , in 1963.

However, just two months after the publication of Literature and Science , Aldous Huxley died on 22nd November 1963, aged 69. Like fellow writer C. S. Lewis , news coverage of his death was overshadowed by the shocking assassination of President John F. Kennedy , who was shot a mere seven hours before Huxley himself passed away.

The timing of Huxley’s death not only meant that it was overshadowed by that of John F. Kennedy but also that he did not live to see the full effects of the 1960s counterculture his work had, in part, helped to inspire. Nonetheless, his was a life of principle and productivity, the legacy of which lives on to this day.

Aldous Huxley on Drugs, Religion, and Spirituality

By Catherine Dent MA 20th and 21st Century Literary Studies, BA English Literature Catherine holds a first-class BA from Durham University and an MA with distinction, also from Durham, where she specialized in the representation of glass objects in the work of Virginia Woolf. In her spare time, she enjoys writing fiction, reading, and spending time with her rescue dog, Finn.

Frequently Read Together

What Happened to the Limo After the Kennedy Assassination?

World War I: The Writer’s War

What Was the Bloomsbury Group?

- Search Grant Programs

- Application Review Process

- Manage Your Award

- Grantee Communications Toolkit

- NEH International Opportunities

- Workshops, Resources, & Tools

- Search All Past Awards

- Divisions and Offices

- Professional Development

- Sign Up to Be a Panelist

- Equity Action Plan

- Emergency and Disaster Relief

- States and Jurisdictions

- Featured NEH-Funded Projects

- Humanities Magazine

- Information for Native and Indigenous Communities

- Information for Pacific Islanders

- Search Our Work

- American Tapestry

- International Engagement

- Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative

- Humanities Perspectives on Artificial Intelligence

- Pacific Islands Cultural Initiative

- United We Stand: Connecting Through Culture

- A More Perfect Union

- NEH Leadership

- Open Government

- Contact NEH

- Press Releases

- NEH in the News

The Talented Mr. Huxley

The brilliant, eclectic thinker who wrote the classic dystopian novel brave new world ..

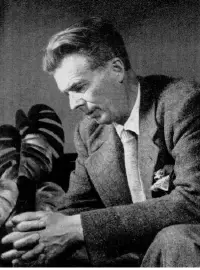

Aldous Huxley in 1934.

—© Pictoral Press Ltd. / Alamy Stock Photo

At six feet four and a half inches, Aldous Huxley was perhaps the tallest figure in English letters, his height so striking that contemporaries sometimes viewed him as a freak of nature. British novelist Christopher Isherwood found Huxley “too tall. I felt an enormous zoological separation from him.” Virginia Woolf described him as “infinitely long” and referred to him as “that gigantic grasshopper.”

Everything about Huxley seemed large. “During his first years his head was proportionately enormous, so that he could not walk until he was two because he was apt to topple over,” writes biographer Sybille Bedford. Shortly before his death, Huxley confided to a friend that his childhood nickname had been “Ogie,” a substitute for “Ogre.”

But this seems like the kind of exaggeration children so often use to rib each other. In pictures, Huxley looks imposing, but far from ugly. Anita Loos, the American screenwriter, playwright, and author, was impressed by Huxley’s “physical beauty . . . the head of an angel drawn by William Blake.”

His voice, preserved in recordings easily sampled online, was also part of his charm. Huxley spoke like Laurence Olivier—with exacting British diction and an unerring verbal accuracy that few people, then or now, possess in casual conversation. He talked in silver sentences, treating conversation as a form of theater, or even literature.

The largeness of the man and the precision of his language continue to live more than a half a century after his death. Every year, another generation of young students gets that sense of him from Brave New World , the 1932 novel that’s become assigned reading for millions of middle schoolers.

Taking its title from an ironic line from The Tempest by Shakespeare, Brave New World envisions a fictional society in which infants are grown in laboratories, and people become so conditioned to consumer comforts that they no longer question their leaders. Amid this malaise lingers a dissident regarded as a savage because he still embraces Shakespeare, his passion for poetry suggesting an indulgence of feeling that, in this brave new world of tomorrow, seems dangerously taboo. Readers still argue about the degree to which Huxley’s grimly conceived future has become the human present, and the emergence of test-tube babies, television, and online culture invite obvious parallels to Brave New World .

Huxley transcribes the emotionally arid landscape of Brave New World into visual terms, translating the dormancy of the human soul into a city devoid of bright colors. In his description of a laboratory where new citizens are conceived, he writes:

The enormous room on the ground floor faced towards the north . . . for all the tropical heat of the room itself, a harsh thin light glared through the windows, hungrily seeking some draped lay figure, some pallid shape of academic goose-flesh, but finding only the glass and nickel and bleakly shining porcelain of a laboratory. . . . The overalls of the workers were white, their hands gloved with a pale corpse-colored rubber. The light was frozen, dead, a ghost.

Huxley also wrote poetry, plays, travelogs, essays, philosophy, short stories, and many novels. Sadly, the overshadowing fame of Brave New World has tended to obscure the range of his talent.

Huxley came from one of England’s great intellectual families: He was born in Surrey, England, the son of Leonard Huxley, editor of the influential Cornhill magazine, and Julia Arnold, niece of the legendary poet and essayist Matthew Arnold. Huxley was the grandson of T. H. Huxley, a scientist and friend of Charles Darwin. Huxley’s brother Julian was a noted biologist and writer, and his half-brother Andrew was a Nobel laureate in physiology.

Huxley appeared destined to work in science, too, initially planning to become a physician. But, in 1911, when he was 16, he suffered an eye infection that left him nearly blind for almost two years. His sight was so compromised that he learned to read in Braille. He eventually recovered some vision, initially using strong eyeglasses to cope. With his sight damaged, a career in medicine or science seemed impractical, so Huxley turned to writing.

“He rose above the disability but he never minimized the importance of the experience in his life,” notes biographer Nicholas Murray. Huxley was fascinated by how adjustments in the senses greatly altered how we perceive reality, a theme that would deeply inform some of his later books.

His struggle with vision was the subject of a 1943 book, The Art of Seeing , in which Huxley championed the controversial theories of Dr. W. H. Bates, who asserted that eyes could be improved with training exercises instead of prescription lenses. Huxley claimed that the Bates Method worked for him, though it still remains far outside the medical mainstream.

Just how much Huxley was able to see is uncertain, although his eyes were obviously compromised, forcing him to compensate in creative ways. Julian Huxley thought that his brother developed a Herculean memory so he could better retain what he labored so hard to read. “With his one good eye, he managed to skim through learned journals, popular articles and books of every kind,” Julian recalled. “He was apparently able to take them in at a glance, and what is more, to remember their essential content. His intellectual memory was phenomenal, doubtless trained by a tenacious will to surmount the original horror of threatened blindness.”

Early in his writing career, Huxley worked as a journalist and teacher, including a stint at Eton instructing a young Eric Blair, who would eventually become known to the world as George Orwell.

Published in 1949, nearly two decades after Huxley’s masterpiece, Orwell’s 1984 depicted a world in which the state imposes its will by force. Huxley wrote a fan letter to Orwell after 1984 appeared, complimenting him on “how fine and how profoundly important the book is.” But Huxley offered a polite dissent from Orwell’s premise: “I feel that the nightmare of Nineteen Eighty-Four is destined to modulate into the nightmare of a world having more resemblance to that which I imagined in Brave New World .” Huxley thought it more likely that in the long run, despots would find it efficient to coddle rather than coerce humans into conformity.

When Huxley published his first novel, Crome Yellow , in 1921, he gained attention not as a sober prophet of human oppression, but a light satirist of the English gentry. “What makes Crome Yellow . . . so appealing is its restfulness,” literary essayist Michael Dirda has observed. “There is no plot to speak of. Nothing dramatic happens. Instead, the book sustains interest almost solely through its style, a low-keyed ironic wit, and the evocation of a leisurely summer of cultivated country-house pleasures. Young people make love and their elders discourse about life; afternoons are spent in walking or painting, evenings taken up with reading aloud and conversation.”

The fictional house of the novel’s title appears to be based on Garsington, the estate where Lady Ottoline Morrell hosted Bloomsbury-era artists and writers, including Huxley. At Garsington, Huxley met the beautiful Maria Nys, a Belgian refugee displaced by World War I. They wed in 1919, and their marriage, perhaps reflecting its origins in Bloomsbury avant-garde society, was unconventional. Maria was bisexual, and the Huxleys at one point entered into a romantic triangle with a mutual friend, Mary Hutchinson. Unusual though such an arrangement might have been, the Huxleys appeared devoted to each other until Maria’s death in 1955. Their household grew to include one son, Matthew, born in April 1920.

“She devoted herself wholly to him,” Murray writes of Maria’s relationship with Aldous. “Because of his poor eyesight, she read to him, endlessly, even if the material bored her beyond belief. She drove him thousands of miles around Europe and the United States—putting her profession as ‘chauffeur’ in hotel registers. She typed his books and was his secretary and housekeeper.”

The life the Huxleys created seemed a mostly happy one. Although the future Huxley popularized in Brave New World was bleak, the author himself didn’t lack cheer or humor, as anyone who reads his essays quickly discovers. “Aldous Huxley is an essayist whom I would be ready to rank with Hazlitt,” Somerset Maugham declared. “The essayist needs character to begin with, then he needs an encyclopedic knowledge, he needs humor, ease of manner so that the ordinary person can read him without labor, and he must know how to combine entertainment with instruction. These qualifications are not easy to find. Aldous Huxley has them.”

“Meditation on the Moon,” a 1931 essay, exemplifies Huxley’s sometimes dreamily poetic style. He argues that skygazers don’t have to think of the moon as either a rock or a romantic icon; it can be both. It’s an essay about the claims and limits of technical knowledge, in which Huxley, whose family tree included poets and scientists, attempts to reconcile their intellectual traditions. He wrote:

The moon is a stone; but it is a highly numinous stone. Or, to be more precise, it is a stone about which and because of which men and women have numinous feelings. Thus, there is a soft moonlight that can give us the peace that passes understanding. There is a moonlight that inspires a kind of awe. There is a cold and austere moonlight that tells the soul of its loneliness and desperate isolation, its insignificance or its uncleanness. There is an amorous moonlight prompting to love—to love not only for an individual but sometimes even for the whole universe.

The passage points to Huxley’s deftness as a scene-setter, a skill that made him a great travel writer, too. Along the Road , Huxley’s 1921 collection of travel essays, is perhaps one of the best modern travel books—and inexplicably, one of the most overlooked. It chronicles his jaunts around Europe, often with self-deprecating charm. In a funny musing called “Books for the Journey,” Huxley considers the bibliophile’s tendency to overpack. “All tourists cherish an illusion, of which no amount of experience can ever cure them; they imagine that they will find time, in the course of their travels, to do a lot of reading,” Huxley writes. “They see themselves, at the end of a day’s sightseeing or motoring, or while they are sitting in the train, studiously turning over the pages of all the vast and serious works which, at ordinary seasons, they never have time to read.”

Huxley suggests, as an alternative to all those heavy books, just toting a random volume of the Encyclopedia Britannica along for the ride. “I never pass a day away from home without taking a volume with me,” he confides. “Turning over its pages, rummaging among the stores of fantastically varied facts which the hazards of alphabetical arrangement bring together, I wallow in my mental vice.”

Huxley was really serious about carrying around the Britannica . “Bertrand Russell joked that one could predict Huxley’s subjects of conversation provided one knew which alphabetical section of the Encyclopedi a he happened to be reading at the time,” Murray notes. “Huxley even constructed a special carrying-case for it on his journeys.”

This was so like Huxley, his mind sparked by any fact, however arbitrary. The poet Elizabeth Bishop, who was living in Brazil when Huxley arrived for a visit, described what it was like to see him explore a new place:

There is a slight cast to his bad eye, and this characteristic, which I always find oddly attractive, in Huxley’s case adds even more to his veiled and other-worldly gaze. When examining something close . . . a photograph or a painting, he sometimes takes out a small horn-rimmed magnifying glass, or, for distant objects, a miniature telescope, and he often sits resting his good eye by cupping his hand over it.

Huxley’s travels paralleled an intellectual and spiritual odyssey that increasingly shaped his work. His early fiction, which extended the wry tone of Crome Yellow , evolved into more somber, psychologically complex novels like Eyeless in Gaza , his 1936 story about a cynical Englishman who comes of age during World War I and eventually turns to Eastern philosophy and meditation to address his disillusionment. Many readers see Eyeless as a deeply autobiographical work reflecting Huxley’s own turn away from ironical detachment to life as, in Dirda’s words, “a gentle mystic.”

Huxley’s globe-trotting took him to the United States in 1937, where he made his home, primarily in Los Angeles, for the rest of his life. Lucrative Hollywood screenwriting jobs proved hard to resist. He wrote film adaptations of Pride and Prejudice and Jane Eyre , as well as a Disney version of Alice in Wonderland that was never made. In 1956, a year after Maria’s death, Huxley married Laura Archera, an Italian violinist and psychotherapist who had been a family friend, and who proved an equally devoted wife. California’s climate of cultural experiment seemed suited to Huxley, whose willingness to explore new things in the pursuit of enlightenment led him to the strangest writing project of his life.

In the spring of 1953, Huxley took a precisely measured dose of mescalin, the hallucinogenic drug derived from the peyote cactus of the American Southwest, then recorded his experience in a small book, The Doors of Perception , its title inspired by a quote from the visionary poet William Blake: “If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, infinite.” Huxley found that the drug greatly enhanced his sense of color. “Visual impressions are greatly intensified and the eye recovers some of the perceptual innocence of childhood,” he wrote. But Huxley also noted that under the influence of mescalin, “the will suffers a profound change for the worse. The mescalin taker sees no reason for doing anything in particular.”

The book doesn’t argue for unrestricted drug use, and in other writings, Huxley pointed out the dangers of abuse and dependency. “In their ceaseless search for self-transcendence, millions of would-be mystics become addicts, commit scores of thousands of crimes and are involved in hundreds of thousands of avoidable accidents,” he cautioned in his essay, “Drugs That Shape Men’s Minds.” Even so, The Doors of Perception achieved considerable cachet in the drug culture of the 1960s. The rock group the Doors took its name from Huxley’s book, and in a sad irony, its lead singer, Jim Morrison, struggled with drug abuse and alcoholism until his death in 1971.

Rockers (from left) John Densmore, Robby Krieger, Ray Manzarek, and Jim Morrison took The Doors as their name, inspired by Aldous Huxley’s The Doors of Perception .

—© Pictoral Press Ltd. / Alamy Stock Photo

Huxley’s own death after a lengthy struggle with cancer contained an irony of its own. He died on November 22, 1963, just hours after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, and on the same day that fellow writer C. S. Lewis passed away. Kennedy’s death overshadowed the passing of Huxley and Lewis. But just as events in Dallas cracked open the chaos of the 1960s, so Huxley’s life and work, with its questioning of conformity and the power of the state, seemed to anticipate the countercultural revolution that would soon sweep his adopted country.

In a 1958 nonfiction work, Brave New World Revisited , Huxley concluded that new developments had made it even more possible for the ominous social order of his most famous novel to be realized. But in Island , a utopian novel completed shortly before his death, Huxley depicted a benevolent mirror image of Brave New World , in which ingenuity is harnessed for good rather than evil. It was Huxley’s way of saying that human destiny is still a matter of moral choice—a choice that must be informed by constant inquiry.

“Fearless curiosity was one of Aldous’s noblest characteristics, a function of his greatness as a human being,” Isherwood recalled of his friend. “Little people are so afraid of what the neighbors will say if they ask Life unconventional questions. Aldous questioned unceasingly, and it never occurred to him to bother about the neighbors.”

Danny Heitman is the editor of Phi Kappa Phi’s Forum magazine and a columnist for the Advocate newspaper in Louisiana. He writes frequently about arts and culture for national publications, including the Wall Street Journal and the Christian Science Monitor.

Funding information

NEH has supported several projects over the years related to Aldous Huxley. Most recently, the Vedanta Society of Southern California received a $6,000 grant that will aid in preserving the society’s archive, which includes some of Huxley’s correspondence. Brave New World is one of the texts assigned to students in an NEH Enduring Questions course on “What is Happiness?” at New Mexico State University. Scholar Jerome Meckier, who has written extensively about Huxley, received a $10,000 NEH fellowship in 1974.

November/December 2015

SUBSCRIBE FOR HUMANITIES MAGAZINE PRINT EDITION Browse all issues Sign up for HUMANITIES Magazine newsletter

Aldous Huxley

Aldous Leonard Huxley (July 26, 1894 – November 22, 1963) was a British - American writer and moral philosopher and is in certain circles regarded as one of the greatest voices of the twentieth century. Wrote Australian writer and acquaintance, Clive James, “Godlike in his height, aquiline features, and omnidirectional intelligence, Huxley was a living myth.” An enduring opponent of the moral decadence of modern culture, Huxley sought through both fiction and non-fiction writing to denounce conformity and the orthodox attitudes of his time (particularly of Western societies) as well as to instill a sense of conscientiousness and outward responsibility in the public.

- 1 Early Years

- 2 Middle Years

- 3 The Later Years

- 4 Death and Legacy

- 5 Huxley On Drug-Taking

- 6 Huxley on the Cheapening of Sexual Pleasure

- 7 Huxley on Environmentalism

- 8 Major Works

- 9 Quotations

- 10 References

Best known for his novels and essays, Huxley functioned as an examiner and sometimes critic of social mores, societal norms, and ideals. While his earlier concerns might be called “humanist,” ultimately, he became quite interested in “spiritual” subjects such as parapsychology and philosophical mysticism .

Early Years

Huxley was born in Godalming, Surrey, England, into one of the most famous families of the English elite. He was son of the writer and professional herbalist Leonard Huxley by his first wife, Julia Arnold; and grandson of Thomas Henry Huxley, one of the most prominent naturalists of the nineteenth century. Additionally, Huxley’s mother was the daughter of Thomas Arnold, a famous educator, whose brother was Matthew Arnold , the renowned British humanist . Julia’s sister was the novelist Mrs. Humphrey Ward. Huxley’s brother Julian Huxley was a noted biologist , and rose to become the first Secretary-General of UNESCO .

A longtime friend, Gerald Heard, said that Huxley’s ancestry “brought down on him a weight of intellectual authority and a momentum of moral obligations.” As a young child, Huxley was already considered amongst adults and peers as being “different,” showing an unusually profound awareness, or what his brother called “superiority.” Huxley would later say that heredity made each individual unique and this uniqueness of the individual was essential to freedom.

Huxley began his learning in his father’s well-equipped botanical laboratory, then continued in a school named Hillside, which his mother supervised for several years until she became terminally ill. From the age of nine and through his early teens, he was educated at Eton College. Huxley’s mother died in 1908, when he was 14, and it was this loss that Huxley later described as having given him his first sense of the transience of human happiness.

Another life-changing event in young Huxley’s life came just a few years later at the age of 16, when he suffered an attack of keratitis punctata, an affliction that rendered him blind for a period of about 18 months. This timely infirmity was responsible for preventing Huxley from participating in World War I , as well as keeping him out of the laboratories where he would have pursued his first love of science —a love that would sustain its influence on him despite his inevitable transitions into more artistic, humanistic, and spiritual life courses. In fact, it was his scientific approach that ultimately complimented these endeavors.

When Huxley eventually recovered his eyesight (though weak eyes would have a significant effect on him throughout the remainder of his life) he aggressively took to literature as both an avid reader and writer. During this time, he studied at Balliol College, Oxford , graduating in 1916 with a B.A. in English. In the same year, his first collection of poetry was published. Following his education at Balliol, Huxley was financially indebted to his father and had to earn a living. For a short while in 1918, he was employed acquiring provisions at the Air Ministry.

With little interest in business or administration, Huxley’s lack of inheritance pressed him into applied literary work. Products of his early writing include two more collections of poetry, as well as biographical and architectural articles and reviews of fiction, drama, music, and art for the London literary magazine Athenaeum , for which he served as part of the editorial staff in 1919-1920. In 1920-1921, Huxley was drama critic for Westminister Gazette , an assistant at the Chelsea Book Club, and worked for Conde Nast Publications.

Middle Years

During World War I , Huxley spent much of his time at Garsington Manor, home of Lady Ottoline Morrell. Later, in Crome Yellow (1921), he caricatured the Garsington lifestyle. He married Maria Nys, a Belgian whom he had met at Garsington, in 1919, and in 1920 they had one child, Matthew Huxley, who grew up to be an epidemiologist. The three traveled extensively in these years, spending a significant amount of time in Italy , with trips also to India , the Dutch Indies, and the United States .

Careerwise, for Huxley the 1920s was a time spent establishing himself in the literary world thanks to a number of largely successful works. In addition to Crome Yellow , there was Antic Hay (1923), Those Barren Leaves (1925), and Point Counter Point (1928). Most of the subject matter that comprised these novels was satirical commentary on contemporary events. Despite his great success, however, the author was criticized during this period for his one-dimensional characters that Huxley used as mouthpieces to say “almost everything about almost anything.” This particular criticism would follow him to some degree throughout his entire career as a fiction writer, as many felt that Huxley cared more for his ideas than he did for his characters or plot. Impartially, the author often cast the same judgment upon himself. According to his second wife, Laura Archera Huxley, Huxley was not completely satisfied with the last novel of his career, Island (1962), because he believed it was “imbalanced” due to the fact that “there was more philosophy than story.” Toward the end of his career, Huxley began to consider himself more of an essayist who wrote fiction, and of all his novels, he told Laura, only Time Must Have a Stop (1944) “put story and philosophy together in a balanced way.”

In the 1930s, the family settled for a while in Sanary, near Toulon. It was his experiences here in Italy , where Benito Mussolini had led an authoritarian government that fought against birth control in order to produce enough manpower for the next war, along with reading books critical of the Soviet Union , that caused Huxley to become even more dismayed by the abject condition of Western Civilization. In 1932, in just four months, Huxley wrote the virulently satiric Brave New World , a dystopian novel set in London in the twenty-sixth century. Here, Huxley painted a “perpetually happy” but inhumane society where warfare and poverty have been eliminated, but only through the sacrifice of family, cultural diversity, art, literature, science, religion, philosophy; and by implementing a hedonistic normality amongst citizens where cheap pleasure, over worthwhile fulfillment, is sought and gained through the corrupted devices of drugs and promiscuous sex. The novel was an international success, and thus publicly began Huxley’s fight against the idea that happiness could be achieved through class-instituted slavery.

In 1937 Huxley moved to Hollywood, California , with his wife, Maria; son, Matthew; and friend Gerald Heard. Huxley appreciated the grit, virility, and “generous extravagance” he found in American life, but was at odds with the ways that this virility was expressed “in places of public amusement, in dancing and motoring … Nowhere, perhaps, is there so little conversation…It is all movement and noise, like the water gurgling out of a bath—down the waste.” At this time too Huxley wrote Ends and Means ; in this work he explores the fact that although most people in modern civilization agree that they want a world of 'liberty, peace, justice, and brotherly love', they haven't been able to agree on how to achieve it.

In 1938 Huxley was also able to tap into some Hollywood income using his writing skills, thanks to an introduction into the business by his friend Anita Loos, the prolific novelist and screenwriter. He received screen credit for Pride and Prejudice (1940) and was paid for his work on a number of other films.

It was also during this time that Heard introduced Huxley to Vedanta and meditation which led to his eventual friendship with J. Krishnamurti, whose teachings he greatly admired. He also became a Vedantist in the circle of Swami Prabhavananda, and introduced Christopher Isherwood to this circle. It was Huxley’s heightening distress at what he regarded as the spiritual bankruptcy of the modern world, along with his transition to America and the subsequent connections it provided, that opened Huxley’s interest in morality as not just a practical issue, but as a spiritual one as well.

In 1945, after continued study and practice, Huxley assembled an anthology of texts along with his own commentary on widely held spiritual values and ideas. The text, titled The Perennial Philosophy , was a new look at an old idea, exploring the common reality underlying all religions, and in particular, the mystical streams within them. He made clear that The Perennial Philosophy was not interested in the theological views of “professional men of letters,” speculative scholars who observed God safely from behind their desks. In the book’s introduction, he writes:

The Perennial Philosophy is primarily concerned with the one, divine Reality substantial to the manifold world of things and lives and minds. But the nature of this one Reality is such that it cannot be directly and immediately apprehended except by those who have chosen to fulfill certain conditions, making themselves loving, pure in heart, and poor in spirit.

In 1946, inspired by his deeper understanding of the spiritual development of man , Huxley wrote a foreword to Brave New World in which he stated that he no longer wanted to perceive social sanity as an impossibility as he had in the novel. Ironically, despite the grimness of World War II , Huxley seemed to have become convinced that while still “rather rare,” sanity could be achieved and noted that he would like to see more of it.

The Later Years

After World War II Huxley applied for United States citizenship, but was denied because he would not say he would take up arms to defend the U.S. Nevertheless, he remained in the United States where throughout the 1950s his interest in the field of psychical research grew keener. His later works are strongly influenced by both mysticism and his experiences with the psychedelic drug mescaline, to which he was introduced by the psychiatrist Humphry Osmond in 1953. Huxley was a pioneer of self-directed psychedelic drug use “in a search for enlightenment,” documenting his early experiences in both the essays The Doors of Perception (the title deriving from some lines in the poem 'The Marriage of Heaven and Hell' by William Blake ) and Heaven and Hell . The title of the former became the inspiration for the naming of the rock band The Doors, and its content is said to have contributed to the early psychedelic movement of the 1960s hippy counterculture.

It is in debate whether or not Huxley’s ideals were deepened or cheapened by his continued experimentation with and candid promotion of psychedelics (Huxley would take either LSD or mescaline a dozen times over the next ten years). Undoubtedly, as we can infer from his essays, partaking in these substances did undeniably enable for him a unique visionary experience, one in which Huxley “saw objects in a new light, disclosing their inherent, deep, timeless existences, which remains hidden from everyday sight.”

"This is how one ought to see, how things really are."

Huxley’s view was that if taken with care and the proper intentions, the use of psychedelic drugs could aid an individual’s pursuit to attain spiritual insight indefinitely. Counter to this philosophy is the idea that the use of such drugs cheapens the divine experience, opening up channels into a deeper existence artificially, and that these channels, while real in themselves, are meant to be opened by a more authentic means, such as through the fulfillment of certain internal conditions. In other words, some opponents of using psychedelics as aids to experiencing connection to the divine looked down upon them as something of a “synthetic shortcut” or a counterfeit “chemical connection” to the spiritual world, which regardless of whether it was a proper means, was certainly not ‘‘the way’’.

In 1955 Huxley's wife Maria died of breast cancer. In 1956 he married to Laura Archera, who was herself an author and who wrote a biography of Huxley.

In 1960 Huxley was diagnosed with cancer and in the years that followed, with his health deteriorating, he wrote the utopian novel Island , and gave lectures on "Human Potentialities" at the Esalen Institute that were foundational to the forming of the Human Potential Movement. He was also invited to speak at several prestigious American universities and at a speech given in 1961 at the California Medical School in San Francisco, Huxley warned:

There will be in the next generation or so a pharmacological method of making people love their servitude and producing dictatorship without tears, so to speak, producing a kind of painless concentration camp for entire societies so that people will in fact have their liberties taken away from them but will rather enjoy it.

Death and Legacy

On his deathbed, unable to speak, Huxley made a written request to his wife for “LSD, 100 µg, i.m..” She obliged, and he died peacefully the following morning, November 22, 1963. Media coverage of his death was overshadowed by news of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy , which occurred on the same day, as did the death of the Irish author C. S. Lewis .

Amongst humanists, Huxley was considered an intellectual’s intellectual. His books were frequently on the required reading lists of English and modern philosophy courses in American universities and he was one of the individuals honored in the Scribner’s Publishing’s “Leaders of Modern Thought” series (a volume of biography and literary criticism by Philip Thody, Aldous Huxley)

In Huxley’s 47 books and throughout his hundreds of essays, perhaps this writer’s essential message all along was the tragedy that frequently follows from egocentrism, self-centeredness, and selfishness. Unfortunately, in the public eye Huxley today is nothing of the respected figure he had been throughout his lifetime. Writes again Clive James:

While he was alive, Aldous Huxley was one of the most famous people in the world. After his death, his enormous reputation rapidly shrank, until, finally, he was known mainly for having written a single dystopian novel…and for having been some kind of pioneer hippie who took mescaline to find out what would happen.

Huxley On Drug-Taking

Huxley had read about drugs while writing Brave New World , but it was 22 years before he experimented with them himself. In an article from 1931, Huxley admitted that drug-taking "constitutes one of the most curious and also, it seems to me, one of the most significant chapters in the natural history of human beings." To be clear, Huxley did not advocate the use of drugs, as in he did not designate mescaline or LSD to be "drugs,” due to the derogatory connotation that the word held in the English language. Huxley looked down upon the “bad drugs” which he felt produced an artificial happiness rendering people content with their lack of freedom. An example of such a bad drug is the make-believe soma (the drink of the ancient Vedic deities), the half-tranquilizer, half-intoxicant the utopians gorged upon in Brave New World . He did approve, however, of the purified form of LSD that the people of Island used in a religious way. In his fictional utopia, the drug could only be used in critical periods of life, such as in initiation rites, during life crises, in the context of a psychotherapeutic dialogue with a spiritual friend, or to help the dying to relinquish the mortal shell in their transfer to the next existence.

Huxley held the value of hallucinogenic drugs in that they give individuals lacking the gift of visionary perception the potential to experience this special state of consciousness, and to attain insight into the spiritual world otherwise only grasped by the inherently gifted mystics, saints, and artists. He also believed that hallucinogens deepened the reality of one’s faith, for these drugs were capable of opening, or cleansing, the “doors of perception” which otherwise blind our spiritual eyes. Huxley’s idea was that these substances are not only beneficial but hold an important place in the modern phase of human evolution. Furthermore, Huxley ascertained that the responsible partaking of psychedelics is physically and socially harmless.

The unintended damage caused by Huxley’s positive depiction of psychedelic drug use can be seen most egregiously in what had occurred throughout the 1960s amongst the various free spirit movements. Hippies, inspired by the contents of The Doors of Perception and Heaven and Hell , distorted the purpose of these drugs as outlined by Huxley, indulging in them recklessly and more as a means to escape reality rather than to more substantially connect to it. It can be clear that Huxley’s intentions were more scientific and hardly, if at all, hedonistic.

In This Timeless Moment , Laura Archera Huxley wrote about that generation’s drug obsession and reminded that in Island , LSD, when given to adolescents, was only provided in a controlled environment. Huxley himself even warned of the dangers of psychedelic experimentation in an appendix he wrote to The Devils of Loudun (1952), a psychological study of an episode in French history. Even in The Doors of Perception , Huxley expresses caution as well as the negative aspects of hallucinogens. Furthermore, in that same book, he clearly describes how mescaline may be a tool in which to “open the door” with, however it only provides “a look inside,” not a means in which to cross the threshold or to experience the benefits of what lies “on the other side”:

It gives access to contemplation—but to a contemplation that is incompatible with action and even with the will to action, the very thought of action. In the intervals between his revelations the mescaline taker is apt to feel that, though in one way everything is supremely as it should be, in another there is something wrong. His problem is essentially the same as that which confronts the quietist, the arhat and, on another level, the landscape painter and the painter of human still lives. Mescaline can never solve that problem; it can only pose it, apocalyptically, for those to whom it had never before presented itself. The full and final solution can be found only by those who are prepared to implement the right kind of Weltanschauung by means of the right kind of behavior and the right kind of constant and unstrained alertness.

The greatest revelation experienced by Huxley while under the influence of hallucinogens occurred shortly after the death of his first wife, Maria. At this point, the author was already growing closer to Laura Archera Huxley and often invited her to be his “companion” while he took LSD. On one occasion in particular, Huxley found it to be a “most extraordinary experience:” “for what came through the open door…” he later wrote, “was the realization of Love as the primary and fundamental cosmic fact.” This became Huxley’s answer to the fundamental question of what is one to do with their visionary experience. He later wrote:

Meister Eckhart wrote that "what is taken in by contemplation must be given out in love." Essentially this is what must be developed—the art of giving out in love and intelligence what is taken in from vision and the experience of self-transcendence and solidarity with the Universe....

Huxley on the Cheapening of Sexual Pleasure

Huxley did not have a black and white perspective of sex, being well aware of both its degradation and divinity in the lives of men and women. Two famous quotes that reflect both sides of Huxley’s spirit toward the subject are: “Chastity…the most unnatural of all the sexual perversions,” which mirrors his attitude that “divine sex” is purely natural and that complete abstinence from it is not only unnatural but a distortion strong enough to be classified as a sickness of character. The second quote, “An intellectual is a person who has discovered something more interesting than sex” reflects Huxley’s observation of “degraded sex” as being a shallow pastime indulged in by the ignorant.

The casualness of sex is also satirically criticized in Brave New World , illustrated through the utopians’ indulgence in it as a surface-level means to satisfy a primal urge, to derive momentary satisfaction freely and from whomever. Huxley shows through the story how this perspective exists at the expense of true love, the genuine connection between two human beings of the opposite sex, and thus also at the expense of the functional family. Huxley has also written that the responsibility of the modern man should is to “civilize the sexual impulse.”

Critics of Huxley have pointed out that despite his objections to the cheapness, degradation, and excessiveness of sex in modern culture, the author himself is culpable of his own immoral doings in this realm. It is no longer a secret (as exposed by various discovered letters) that Huxley engaged in a number of affairs, albeit with his wife’s connivance, during his first marriage to Maria after the couple had arrived in California. Maria believed that these relationships would help Huxley to take his mind off work. These affairs, however, occurred only before the “revolution of heart” that Huxley experienced while under the influence of LSD and after Maria’s death. After this epiphany, Huxley even took it upon himself to practice abstinence so as to test himself on the grounds of his new ideal. On one occasion, an old lover came to visit him later in his life was taken aback when Huxley spent the entire engagement discussing Catherine of Siena .

Huxley on Environmentalism

Many are surprised to find that Huxley, conscientious in most arenas, even wrote an early essay on ecology that helped inspire today’s environmental movement.

Also, during the later summer of 1963, Huxley was invited to speak at the World Academy of Arts and Sciences (WAAS) in Stockholm, Sweden , where the main issue of the meeting concerned the population explosion and the raw material reserves and food resources of the earth. Huxley spoke about how a human race with more highly developed spiritual capacities would also have a greater understanding of and better consideration for the biological and material foundations of life on this earth.

Major Works

Huxley wrote many screenplays, and many of his novels were later adapted for film or television. Notable works include the original screenplay for Disney's animated Alice in Wonderland , two productions of Brave New World , one of Point Counter Point , one of Eyeless in Gaza , and one of Ape and Essence . He was one of the screenwriters for the 1940 version of Pride and Prejudice and co-wrote the screenplay for the 1944 version of Jane Eyre with John Houseman. Director Ken Russell's 1971 film The Devils , starring Vanessa Redgrave, is adapted from Huxley's The Devils of Loudun , and a 1990 made-for-television film adaptation of Brave New World was directed by Burt Brinckeroffer.

- Chrome Yellow (1921)

- Antic Hay (1923)

- Those Barren Leaves (1925)

- Point Counter Point (1928)

- Brave New World (1932)

- Eyeless in Gaza (1936)

- After Many a Summer (1939)

- Time Must Have a Stop (1944)

- Ape and Essence (1948)

- The Genius and the Goddess (1955)

- Island (1962)

- Limbo (1920)

- Mortal Coils (1922)

- Little Mexican (1924)

- Two or Three Graces (1926)

- Brief Candles (1930)

- The Young Arquimedes

- Jacob's Hands; A Fable (Late 1930s)

- Collected Short Stories (1957)

- The Burning Wheel (1916)

- Jonah (1917)

- The Defeat of Youth (1918)

- Leda (1920)

- Arabia Infelix (1929)

- The Cicadias and Other Poems (1931)

- First Philosopher's Song

- Along The Road (1925)

- Jesting Pilate (1926)

- Beyond the Mexique Bay (1934)

- On the Margin (1923)

- Along the Road (1925)

- Essays New and Old (1926)

- Proper Studies (1927)

- Do What You Will (1929)

- Vulgarity in Literature (1930)

- Music at Night (1931)

- Texts and Pretexts (1932)

- The Olive Tree (1936)

- Ends and Means (1937)

- Words and their Meanings (1940)

- The Art of Seeing (1942)

- The Perennial Philosophy (1945)

- Science, Liberty and Peace (1946)

- Themes and Variations (1950)

- Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow (1952)

- The Doors of Perception (1954)

- Heaven and Hell (1956)

- Adonis and the Alphabet (1956)

- Collected Essays (1958)

- Brave New World Revisited (1958)

- Literature and Science (1963)

- The Perennial Philosophy (1944) ISBN 006057058X

- Grey Eminence (1941)

- The Devils of Loudun (1952)

- The Crows of Pearblossom (1967)

- Text and Pretext (1933)

- Moksha: Writings on Psychedelics and the Visionary Experience (1977)

- "Maybe this world is another planet’s hell."

- "All that happens means something; nothing you do is ever insignificant."

- "A child-like man is not a man whose development has been arrested; on the contrary, he is a man who has given himself a chance of continuing to develop long after most adults have muffled themselves in the cocoon of middle-aged habit and convention.

- "Man is an intelligence in servitude to his organs."

- "Most ignorance is vincible ignorance. We don’t know because we don’t want to know."

References ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Huxley, Aldous. The Doors of Perception and Heaven and Hell . New York: HarperPerennial, 2004. ISBN 0060595183

- Huxley, Aldous. Island . New York: HarperPerennial, 2002. ISBN 0060085495

- Huxley, Aldous. Huxley and God: Essays . New York: Crossroad, 2003. ISBN 0824522524

- Huxley, Aldous. Brave New World . New York: HarperPerennial. Reprint edition, 1998. ISBN 0060929871

- Sawyer, Dana. Aldous Huxley: A Biography . New York: Crossroad, 2005. ISBN 0824519876

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards . This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Aldous Huxley history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia :

- History of "Aldous Huxley"

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- Writers and poets

- Philosophers

- Pages using ISBN magic links

IMAGES